Abstract

The gut microbiome has been shown to be affected by the use of many human-targeted medications, and the interaction can be bidirectional. This has been clearly demonstrated for type 2 diabetes medications that have been in clinical use for several decades. However, the bidirectional effects of novel type 2 diabetes drugs semaglutide, empagliflozin, and the gut microbiome have yet to be clearly described. Considering this, we investigate the effect of semaglutide and empagliflozin initiation on the gut microbiome of type 2 diabetes patients. In addition, we analyze whether the pre-treatment gut microbiome can predict the treatment efficacy. In the study, patients with type 2 diabetes donated gut microbiome fecal samples at four timepoints (Baseline, Month 1, Month 3, Month 12) that were studied using 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing and analysis. Subjects additionally donated plasma and urine samples for quantitative measurement of clinical markers before treatment initiation and at Months 3 and 12. Repeated measures ANOVA paired with paired t-tests were used to analyze the effects of drug initiation on the gut microbiome. Pearson correlation was used to identify microbial features associated with the change in clinical parameters. First, semaglutide and empagliflozin use is associated with changes in the gut microbiome after treatment initiation, but changes in microbial diversity were not detected. Moreover, the baseline gut microbiome predicted changes in glycohemoglobin for semaglutide and empagliflozin users. Based on the results, our findings suggest that semaglutide and empagliflozin impact the gut microbial community during treatment. In addition, the baseline gut microbiome can predict semaglutide treatment effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a complex disease that is characterized by elevated circulating glucose levels, which can lead to a significant reduction in the quality of life and severe complications such as kidney failure, amputations, and premature cardiovascular mortality1,2. In 2021, more than 480 million people were living with type 2 diabetes, and its prevalence is expected to rise to 700 million by 20403. Therefore, T2D significantly burdens healthcare systems worldwide, and effective treatment options are continuously being developed1. Despite these novel antidiabetic medications improving T2D treatment results, their efficacy may decrease over time and could be intolerable due to side effects4,5,6. Therefore, understanding the reasons for such inter-individual variability in the treatment response and guiding treatment personalization are necessary.

The gut microbiome can be one of the contributors to the interindividual variability in drug response7. The gut microbiome interacts closely with medications, affecting their properties and actions. Such interactions, for example, may involve drug metabolization, which results in altered concentration of the medication and its metabolites or unexpected effects that can potentially affect the overall outcomes or cause severe side effects, leading to treatment discontinuation8,9,10. On the other hand, drug-microbiome interactions are reciprocal. Many drugs, such as antidepressants, proton pump inhibitors, and antipsychotics, have been demonstrated to modulate the gut microbiome11,12,13. These drug-bug interactions have been well characterized for metformin, a common first-choice antidiabetic drug14. It has been shown that metformin alters the microbiome composition, but the microbiome is also a part of the mode of action of the drug and can modulate drug efficiency and toxicity14,15,16. Similarly to the first-choice metformin, the action of novel glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1-RA) and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2i) towards the microbiome has been previously studied17,18,19,20,21,22. However, these studies have shown conflicting results regarding the changes in microbial diversity and abundance of microbial taxa. Therefore, the effect of GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT-2 inhibitors on the microbiome and the effect of the microbiome on the drug effect remains to be determined.

Here, we aim to investigate the interactions between the usage of semaglutide (e.g., Ozempic, GLP-1-RA), empagliflozin (e.g., Jardiance, SGLT-2i), and the gut microbiome. Based on the clinical outcomes and gut microbiome measured before and after treatment initiation, we characterize the changes in the microbiome attributable to GLP-1 receptor agonist and SGLT-2 inhibitor admission. In addition, we show that the baseline microbiome can predict changes in the clinical parameters after treatment initiation, suggesting that the microbiome can be used for treatment personalization.

Results

Cohort overview and study design

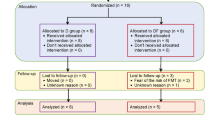

In this study, we recruited 20 subjects with T2D who had been previously using metformin as a part of the treatment regime and had a BMI of at least 32. As the study was conducted in a routine clinical setting, the patients who had more severe obesity and/or diabetes compensation were more likely to be prescribed semaglutide, and subjects with heart and kidney failure or T2D complications were more likely prescribed empagliflozin as a supplementary treatment. Participants were asked to donate microbiome fecal samples four times – at baseline, 1 month (M1), 3 months (M3), and 12 months (M12). Fasting blood samples, overnight urine samples as well as clinical anthropometric measurements were collected at baseline, 3 months (M3) and 12 months (M12) (Fig. 1a). The microbiome was profiled from fecal samples by sequencing the V3-V4 regions of the 16S rRNA gene. In total, 73 fecal samples were analyzed, with 10 participants taking semaglutide (35 fecal samples) and 10 participants taking empagliflozin (38 fecal samples).

In the semaglutide study group, mean glycohemoglobin (HbA1c) values decreased by − 11.37 mmol/mol (1.11%) between treatment initiation and the third month (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Table 1). The decrease for empagliflozin users was − 13.88 mmol/mol (0.88%). At M12, a decrease in HbA1c constituted − 8.2 mmol/mol (1.4%) and − 18.25 mmol/mol (0.48%) for semaglutide and empagliflozin users, respectively.

Compared to baseline, BMI (kg/m2) for the semaglutide users decreased by 1.69 units by the third treatment month. The BMI in the empagliflozin study group decreased by 0.88 units by M3 (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Table 1). At the 12-month timepoint, the BMI on average decreased by 5.61 units in the semaglutide group and increased by 0.7 units in the empagliflozin group.

Study design and clinical endpoints. (a) Overview of the study design. (b) Changes in HbA1c after 3 and 12 months following semaglutide (GLP-1-RA) and empagliflozin (SGLT-2i) initiation. (c) Changes in BMI after 3 and 12 months following semaglutide (GLP-1-RA) and empagliflozin (SGLT-2i) initiation. After inclusion and exclusion criteria, 20 T2D patients were recruited to receive either semaglutide or empagliflozin. Subjects provided 4 samples: before treatment initiation and 1, 3, and 12 months after treatment initiation. T2D—type 2 diabetes, HRT—hormone replacement therapy, GAD65—glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 antibodies, qd—daily (quaque die).

Drug initiation shows no direct effects on the changes in the fecal microbiome

To elucidate the effect of antidiabetic drug usage on the gut microbiome, we compared the baseline gut microbiome with the microbiome composition of M1, M3, and M12 (Fig. 1a) (Methods). First, we analyzed changes in the alpha diversity (observed richness, Shannon index, Pielou index) using repeated measures analysis of variance. No significant changes were detected before and after correcting for multiple testing (Fig. 2a, b; Supplementary Table 2). Second, we studied shifts in the overall composition (beta diversity) by analyzing changes in the first 5 principal components of the genus-level CLR-abundance profile. We detected nominally significant changes in PC1 in the semaglutide group and in PC5 in the empagliflozin group (repeated measures ANOVA, p ≤ 0.05). Post-hoc tests indicated a nominally significant alteration in PC2 between baseline and M3 for empagliflozin users. However, similarly to alpha diversity, no changes remained statistically significant after applying FDR correction (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Table 2).

Effect of semaglutide and empagliflozin on the gut microbial diversity in T2D patients. Microbial alpha diversity (observed genera, Shannon diversity, Pielou’s evenness) and three principal components (beta diversity) at four timepoints. Pairwise t-test p-values comparing the microbiome diversity between baseline and later timepoints are shown. (a) Semaglutide (GLP-1-RA) study group. (b) Empagliflozin (SGLT-2i) study group. BL—baseline, M1—1st month of treatment, M3—3rd month, M12 – 12th month.

Next, to characterize the changes in the microbiome in greater detail, we analyzed alterations in the abundance of bacterial genera prevalent in at least 10 samples per study group (128 genera for semaglutide, 147 genera for empagliflozin). First, we aimed to identify genera with altered abundance in between any of the four timepoints. In the semaglutide group, we identified the abundance to be changed between six genera (repeated measures ANOVA, p ≤ 0.05). These included genera Actinomyces, Candidatus Soleaferrea, Fusobacterium, Haemophilus, Pseudobutyrivibrio, and Veillonella (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Table 2). However, none of these associations remained significant after applying the FDR correction. Similarly, in the empagliflozin group, the abundance of nine bacterial genera was identified to be different between the timepoints (repeated measures ANOVA, p ≤ 0.05). These genera included Agathobacter, Akkermansia, Coprococcus 2, DTU089, Parasutterella, Romboutsia, Ruminococcaceae UCG-014, Turicibacter, and uncultured_bacterium 8 from the order Mollicutes RF39 (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Table 2). However, no significant associations were detected after p-value correction.

In addition to changes in the microbiome composition, we investigated the effects of semaglutide and empagliflozin on the transformed abundances (z-scores) of predicted MetaCyc microbial pathways using PICRUSt2 (Methods). Similarly to the previous analysis, pathways prevalent in at least 10 samples per study group were included (408 in the semaglutide group, 436 in the empagliflozin group). In the semaglutide group, we detected 19 functional pathways with changes in their z-scores (repeated measures ANOVA, p ≤ 0.05). The three most significant pathways among others were 1,4-dichlorobenzene degradation, L-methionine biosynthesis I, and 3,5-dichlorocatechol degradation (Supplementary Table 2). However, no associations remained significant after applying the FDR correction. Next, in the empagliflozin study group, we identified the z-scores to be changed between 7 microbial pathways (repeated measures ANOVA, p ≤ 0.05). For example, these included assimilatory sulfate reduction IV, glucosylglycerol biosynthesis, and assimilatory sulfate reduction I (Supplementary Table 2). Two pathways – assimilatory sulfate reduction I and superpathway of sulfate assimilation and cysteine biosynthesis – were found to be significant for both study groups. Nevertheless, we detected no significant associations after p-value correction.

Next, for the nominal associations identified, we carried out further analyses to identify the timepoints between which the abundance of the genera and functional pathways was changed (post-hoc pairwise t-tests). Interestingly, we observed that in both study groups, the changes in the abundances of the bacteria and functional pathways were not evident when comparing the baseline with the latter timepoint. Instead, the change was more evident between the microbiome collected at Month 3 and Month 12 (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 2). Thus, the results suggest that semaglutide and empagliflozin do not directly affect the gut microbiome. The changes in the microbiome observed between the latter timepoints are likely due to changes in metabolic health or lifestyle.

Changes in the CLR-transformed abundances of bacterial genera in the semaglutide and empagliflozin study group. (a) Semaglutide study group (GLP-1-RA). (b) Empagliflozin study group (SGLT-2i). Genera detected as nominally significant in the repeated measures ANOVA analysis are shown. The p-values on the plot refer to post-hoc analysis using pairwise t-tests to compare the changes between the baseline timepoint and later timepoints. BL—baseline, M1—1st month of treatment, M3—3rd month, M12—12th month.

Gut microbiome correlates with treatment efficacy

Next, we evaluated the ability of the baseline gut microbiome to predict changes in the major clinical endpoints, indicating the efficacy of the antidiabetic therapy. We calculated Pearson correlations between the CLR-transformed abundances of prevalent genera, alpha and beta-diversity metrics, and changes in clinical markers between BL and M3. Baseline microbiome values also included transformed abundances (z-scores) of prevalent functional pathways. As for clinical parameters, we focused on BMI, glycohemoglobin (HbA1c), measures of lymphocytes and neutrophils, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and the amount of white blood cells (WBC). In the empagliflozin study group, glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was additionally included to assess how the baseline microbiome influences the drug’s effect on kidney function. In the semaglutide study group (GLP-1-RA), 577 out of 3,258 associations were nominally significant (p < 0.05), with the most associations with the change in white blood cells and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) (Supplementary Table 2). After the FDR correction, the correlation between the abundance of Alistipes and neutrophils’ and NLR change remained significant (Supplementary Table 2). A higher abundance of Alistipes was associated with a higher decrease in neutrophils and NLR. Most importantly, six genera were found to be associated with the change in HbA1c (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Table 2). In the empagliflozin group, 179 associations among 4,137 were detected as nominally significant (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Table 2). However, none of these correlations were significant after correcting for multiple testing. Similarly to the semaglutide study group, the associations between six bacterial genera, twelve functional pathways, and the change of HbA1c were found to be nominally significant, including genera Prevotellaceae NK3B31 group, Candidatus Soleaferrea, and Escherichia-Shigella (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Table 2). For example, a higher abundance of Escherichia-Shigella indicates a higher reduction in HbA1c. Therefore, our results suggest that the fecal microbiome could be used to predict the treatment outcome of semaglutide and empagliflozin.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the effect of two novel T2D medications – semaglutide and empagliflozin – on the gut microbiome of T2D patients and evaluated the possibility of using gut microbiome for predicting the efficacy of T2D treatment. To our knowledge, among the GLP-1 receptor agonists, this is the first study to analyze changes in the microbiome after semaglutide initiation. We found that semaglutide and empagliflozin have no significant effect on gut microbial composition. However, we found the baseline microbiome to correlate with the change in clinical outcomes. The associations that emerged from the correlation analysis may pinpoint the gut microbiome’s potential capacity to aid in personalizing antidiabetic therapy.

Surprisingly, we found no significant effect of semaglutide and empagliflozin on the gut microbial alpha and beta diversity. These findings agree with several previous studies, where gut microbiome diversity remained unaltered following GLP-1 receptor agonist or SGLT-2 inhibitor consumption throughout the treatment period18,19,20. However, Deng et al. detected an increase in gut microbial alpha diversity when investigating the effect of empagliflozin21. Nevertheless, they compared the alpha diversity between naive empagliflozin initiators with the alpha diversity of metformin users. In contrast, subjects in our study had already been taking metformin before the treatment with empagliflozin. The actions of metformin on the gut microbial community have been previously well-characterized and, thus, could potentially obscure the potential effects of additional semaglutide and empagliflozin consumption14,15,16.

Previous studies have investigated the associations between the gut microbiome and antidiabetic treatment efficacy. For example, Tsai et al. detected 17 distinct microbial features associated with alterations in HbA1c for subjects taking liraglutide or dulaglutide, two glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists19. Interestingly, some of the bacterial features overlapped with the results of our study, namely the genera Bacteroides and Lachnoclostridium. In addition, GLP-1 receptor agonists have been associated with upregulation of several metabolic pathways, including the synthesis of several amino acids using sulfur as a source. For instance, Glaros et al. identified pathways of L-methionine biosynthesis I and superpathway of sulfate assimilation and cysteine biosynthesis to be enriched following treatment with metformin and liraglutide, another medication in the GLP-1 receptor agonists drug class17. Changes in these microbial pathways also coincided with the results of our study. For sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, earlier studies have primarily analyzed the associations between the gut microbiome and the efficacy of dapagliflozin or gliclazide20. Unlike the studies that suggest the effect of microbiome on the efficacy of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, the ability of baseline gut microbiome to predict the response to sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors remains to be demonstrated. Nevertheless, we are unaware of any studies that have shown the effect of microbiome on the efficacy of semaglutide. Based on previous results and findings from our study, the potential links between baseline gut microbiome and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists merit further investigation in personalizing T2D treatment.

Considering that most medications affect the gut microbiome over a more extended period23, the design of this study allows us to define more clearly the changes in microbial composition and diversity. Compared to previous studies on T2D medications and gut microbiome that have implemented only a single or two timepoint sample and data collection, subjects in our study were monitored at four timepoints for 12 months. Taking advantage of the long follow-up period allowed us to show that the changes in the microbiome composition are not observable directly after treatment initiation but after a more extended time. Regarding this, future studies that monitor longitudinal alterations in the gut microbial community should be able to detect precise changes in the microbiome and more accurately predict the effect of antidiabetic drug action using gut microbial data.

It should be noted that several technical aspects could affect the statistical power of analysis and interpretation of the results, e.g., relatively small cohort size and missing samples at various timepoints for some participants. In addition, it is worth reminding that while the consumption of semaglutide or empagliflozin may have caused some direct changes in the abundance of these bacterial genera, the general effect of T2D treatment might have indirectly altered the compositional values of bacterial taxa, e.g., through reduced hyperglycemia and body mass index.

In summary, the findings from our study show that the gut microbial community can predict semaglutide treatment effects based on changes in clinical markers. In addition, semaglutide and empagliflozin are associated with gut microbiome alterations throughout antidiabetic therapy, even if changes arose due to the indirect effects of T2D treatment, e.g., decreased BMI and HbA1c. The ability of the microbiome to predict treatment efficacy warrants further investigation into the causality and functional significance of these findings. This could result in prescribing the most suitable T2D medication before treatment or altering the gut microbial community during treatment. Overall, the longitudinal data of our study provide the means to undertake further studies to validate these signals in larger cohorts.

Methods

Study design and sample collection

Twenty subjects (10 women and 10 men) were enrolled in the study between November 2019 and January 2023 from the University of Tartu Hospital, Tartu, Estonia. The study followed sampling protocols approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Tartu (290/T-20) and according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from each subject. All participants had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, had a BMI of 32 or more, glycohemoglobin (HbA1c) < 86 mmol/mol (< 10%), and were taking 1.5 g of metformin per day (Fig. 1a). All participants were metformin-treated at a stable dose prior to baseline, reducing between-subject variability attributed to metformin while reflecting real-world care. In addition, each subject served as their own control throughout the study period. The main exclusion criteria included the following:

-

1.

Having positive glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD 65) antibodies,

-

2.

An earlier prescription of oral or intravenous antibacterial medications within the last two months,

-

3.

A change in antidiabetic treatment regimen within the last 90 days,

-

4.

Previous use of GLP-1 receptor agonists or SGLT-2 inhibitors,

-

5.

Use of spironolactone within the last 60 days,

-

6.

Current usage of immunomodulating medications (glucocorticoids, cytostatic drugs, or biopharmaceuticals),

-

7.

Being pregnant or planning pregnancy,

-

8.

Consuming oral contraceptives or oral hormone replacement therapy medications,

-

9.

Having previously been diagnosed with a malignant tumor,

-

10.

Having a diagnosis of New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III and IV heart failure or a diagnosis of severe liver disease.

As a result, the study group taking semaglutide included 6 women and 4 men with ages ranging from 48 to 77 (mean 65.7 ± 8.4) and BMI ranging from 35.69 to 47.87 kg/m2 (mean 42.2 ± 5.27). The group prescribed empagliflozin included 4 women and 6 men with age ranging from 52 to 75 (mean 61.7 ± 7.7) and with BMI ranging from 31.67 to 51.04 kg/m2 (mean 37.02 ± 5.89) (Supplementary Table 1). Subcutaneous semaglutide or oral empagliflozin was initiated non-randomly at the clinician’s discretion, considering the need for treatment intensification and weight loss, as well as comorbidities (e.g., obesity with body mass index over 35 kg/m2, heart failure), contraindications (e.g., pancreatitis, kidney failure), and patient preferences.

The study workflow is shown in Fig. 1. Each participant donated a venous blood sample, an overnight urine sample, and a fecal sample for microbiome analysis at baseline before treatment initiation, after 1 month, 3 months, and 12 months of treatment. In addition, body anthropometric measures were recorded. The dose of empagliflozin was 10 mg once a day. A once-weekly subcutaneous (s/c) semaglutide was started at 0.25 mg per dose and then up-titrated to 0.5 mg once a week at week 5 and to 1 mg once a week at week 9. Treatment efficacy was assessed by measuring glycohemoglobin (HbA1c), fasting blood glucose, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and inflammation markers (neutrophils, lymphocytes, white blood cells, and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio) at Month 3 and Month 12. Several other parameters, like glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), blood lipids, and transaminases, were also analyzed.

DNA extraction and sequencing

For DNA extraction, study participants collected fecal samples with a special stool sampling kit with instructions. Samples were collected using an RNALater sample stabilizing solution and taken to the University of Tartu Hospital, Tartu, Estonia. Immediately after arrival, samples were stored at − 20 °C and then taken to the Institute of Genomics, University of Tartu, Estonia, where samples were stored at − 80 °C before follow-up analyses.

DNA extraction of fecal samples was carried out with the Qiagen DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands). Samples were first brought out to room temperature at 25 °C for complete dethawing, and 100 µl of starting material was taken from samples. In the following step, 100 µl of Qiagen PowerBead Pro Tube silica gel beads were added to the sample material and heated at 37 °C to ensure complete dissolution of salt crystals in RNALater. Next, 800 µl of solution CD1 was transferred to samples following incubation at 65 °C for 10 min to activate lysis processes of microbial and human intestine cells. The sample disruption step was completed using a tissue homogenizer Precellys 24 (Bertin Instruments, Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France) at 2500 rpm for 2 × 30 s with a 30-second pause between two cycles. The following extraction process was conducted according to the manufacturer’s protocols. All extracted DNA samples were stored at − 20 °C.

The sequencing process of genomic DNA was conducted twice at the Core Facility of Genomics, Institute of Genomics, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia, first in February 2022 (N = 52 samples) and then in January 2023 (N = 26 samples). The concentrations and quality of extracted DNA samples were first assessed using a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Grand Island, USA). Extracted genomic DNA was then amplified in the PCR amplification reaction with forward and reverse primers designed for the approximately 460 bp long V3-V4 hypervariable region of the prokaryotic 16S ribosomal RNA gene – 16S_F (5′- TCGTCG GCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG − 3′) and 16S_R (5′-GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGACTACHVGGGTATCTAAT CC −3)24.

Microbial community analysis

Raw sequences were demultiplexed with Illumina bcl2fastq2 Conversion Software v2.20. Bioinformatic analyses of genomic DNA reads were conducted with the open-source software platform QIIME 2 (version 2021.11)25. For importing data into QIIME 2, the script q2-tools was used in the format of PairedEndFastqManifestPhred33. The first analysis involved denoising sequences with DADA2 software as part of the QIIME 2 platform26. In addition, forward and reverse sequences were joined at this step. As a result of the first quality control, each base pair position was given a quality score according to whether reads were trimmed and truncated in the following analysis. Due to the better overall quality of reads, the remaining analysis was conducted using forward reads trimmed and truncated at positions 15 and 288. Reads marked as chimeric were removed with the consensus filter. Following the quality control, reads were aligned to amplicon sequence variants (ASV) with software MAFFT27. The taxonomic classification was carried out using the QIIME 2 script q2-feature-classifier with pre-trained naïve Bayes classifier against the SILVA 16S V3-V4 v132_99 with a similarity threshold set to 99%28.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses of microbial ASVs were conducted in R (version 4.3.1). Packages used in the analyses included mia (v.1.8.0), dplyr (v.1.1.3), tidyr (v.1.3.0), and purrr (v.1.0.2). Figures were obtained with the package miaViz (v.1.8.0), pheatmap (v.1.0.12), and ggplot2 (v.3.4.3). Additional customizations were done using vector graphics software Inkscape (v.1.3).

Initially, 78 samples from 21 patients were included in the microbiome analysis, but four samples from one individual were removed due to the missing baseline sample. Additionally, one sample was excluded due to the low number of reads. Thus, the final number of samples was 73 samples from 20 patients.

Alpha diversity was assessed using the mia package from microbial genus-level data. The alpha diversity indices included the number of observed genera, the Shannon diversity index, and Pielou’s evenness index. Beta diversity was assessed using five principal components (PC1-PC5) of the principal component analysis on the Aitchison distance. In addition to the diversity analysis, the abundance of genera present in at least 10 samples per study group was analyzed. As a result, we investigated changes in CLR-values of 128 genera in the semaglutide study group and 147 genera in the empagliflozin study group.

In addition to the analysis of the gut microbiome composition, we investigated the effect of semaglutide and empagliflozin on functional pathways carried out by various gut bacteria. Metabolic pathways and their abundances were predicted with the PICRUSt2 software along with the MetaCyc reference database29,30. To pathway abundance values, logarithmic transformation was applied and values were further standardized to z-scores. Similarly to previous gut microbiome analyses, functional pathways present in at least 10 samples were included in the analysis, resulting in 408 and 436 pathways assessed in the semaglutide and empagliflozin study group, respectively.

To study the effect of two diabetes medications on the gut microbiome, we analyzed the changes in the microbial diversity, the abundance of the prevalent genera, and transformed abundance values of microbial pathways after treatment initiation. Changes in the microbiome were assessed with repeated measures ANOVA. Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) method was used to account for multiple testing31. In addition, two-sided dependent Welch t-tests were performed as post-hoc tests to study changes in the abundance of genera and functional pathways between two timepoints. Post-hoc tests were carried out for genera and pathways that showed a difference in the abundance of genera and microbial pathways in the repeated measures ANOVA analysis.

To understand whether baseline gut microbiome could predict the efficacy of semaglutide and empagliflozin in antidiabetic treatment, baseline microbiome values were correlated with the change of clinical markers by the third treatment month. This is the timepoint where we detected the largest treatment effect of semaglutide and empagliflozin therapy. The baseline gut microbiome values included alpha and beta diversity indices, CLR-transformed values of prevalent genera, and z-scores of functional pathways. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated, and the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for adjusting the p-values was used to account for multiple testing (FDR < 0.05).

Data availability

The data generated in this study have been deposited in the European Genome-Phenome Archive database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ega/) under accession code EGAD50000000756 (release on 14.08.24).

References

Skyler, J. S. et al. Differentiation of diabetes by pathophysiology, natural history, and prognosis. Diabetes 66, 241–255 (2016).

Li, G. et al. Cardiovascular mortality, all-cause mortality, and diabetes incidence after lifestyle intervention for people with impaired glucose tolerance in the Da Qing diabetes prevention study: a 23-year follow-up study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2, 474–480 (2014).

International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas 2021. (2021).

Mulder, S. et al. Effects of Dapagliflozin on urinary metabolites in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metabolism. 21, 2422–2428 (2019).

Nauck, M. A. et al. A phase 2, Randomized, Dose-finding study of the novel once-weekly human GLP-1 analog, semaglutide, compared with placebo and open-label liraglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 39, 231–241 (2015).

Wilding, J. P. H. et al. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 989–1002 (2021).

Maier, L. & Typas, A. Systematically investigating the impact of medication on the gut Microbiome. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 39, 128–135 (2017).

Zimmermann, M., Zimmermann-Kogadeeva, M., Wegmann, R. & Goodman, A. L. Mapping human Microbiome drug metabolism by gut bacteria and their genes. Nature 570, 462–467 (2019).

Sousa, T. et al. On the colonic bacterial metabolism of azo-bonded prodrugsof 5-aminosalicylic acid. J. Pharm. Sci. 103, 3171–3175 (2014).

Nakayama, H. et al. Intestinal anaerobic bacteria hydrolyse sorivudine, producing the high blood concentration of 5-(E)-(2-bromovinyl)uracil that increases the level and toxicity of 5-fluorouracil. Pharmacogenetics 7, 35–43 (1997).

Maier, L. et al. Extensive impact of non-antibiotic drugs on human gut bacteria. Nature 555, 623–628 (2018).

Imhann, F. et al. Proton pump inhibitors affect the gut Microbiome. Gut 65, 740–748 (2016).

Jackson, M. A. et al. Proton pump inhibitors alter the composition of the gut microbiota. Gut 65, 749–756 (2016).

Forslund, K. et al. Disentangling type 2 diabetes and Metformin treatment signatures in the human gut microbiota. Nature 528, 262–266 (2015).

Buse, J. B. et al. The primary glucose-lowering effect of Metformin resides in the gut, not the circulation: results from short-term Pharmacokinetic and 12-week dose-ranging studies. Diabetes Care. 39, 198–205 (2015).

Elbere, I. et al. Gut Microbiome encoded purine and amino acid pathways present prospective biomarkers for predicting Metformin therapy efficacy in newly diagnosed T2D patients. Gut Microbes. 16, 2361491 (2024).

Glaros, S. B. et al. Systemic and gut Microbiome changes with Metformin and liraglutide in youth-onset type 2 diabetes: the MIGHTY study. Gut Microbes. 17, 2558071 (2025).

Smits, M. M. et al. Liraglutide and sitagliptin have no effect on intestinal microbiota composition: A 12-week randomized placebo-controlled trial in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 47, 101223 (2021).

Tsai, C. Y. et al. Gut microbial signatures for glycemic responses of GLP-1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetic patients: A pilot study. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 1–11 (2022).

van Bommel, E. J. M. et al. Effects of 12-week treatment with Dapagliflozin and Gliclazide on faecal microbiome: results of a double-blind randomized trial in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 46, 164–168 (2020).

Deng, X. et al. Cardiovascular benefits of empagliflozin are associated with gut microbiota and plasma metabolites in type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism. 107, 1888–1896 (2022).

Wang, L., Jia, X., Zhang, Y. & Yuan, H. Canagliflozin alters the gut, oral, and ocular surface microbiota of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1–12 (2023).

Nagata, N. et al. Population-level metagenomics uncovers distinct effects of multiple medications on the human gut microbiome. Gastroenterology 163, 1038–1052 (2022).

Klindworth, A. et al. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e1 (2013).

Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible Microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852–857 (2019).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods. 13, 581–583 (2016).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596 (2013).

Douglas, G. M. et al. PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 685–688 (2020).

Wright, R. J. & Langille, M. G. I. PICRUSt2-SC: an update to the reference database used for functional prediction within PICRUSt2. Bioinformatics 41, btaf269 (2025).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. Roy. Stat. Soc.: Ser. B (Methodol.). 57, 289–300 (1995).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the European Union through the European Regional Development Fund Project No. 2014-2020.4.01.15-0012 GENTRANSMED. Data analysis was carried out in part in the High-Performance Computing Center of the University of Tartu. We thank Reidar Andreson for the bioinformatic support.

Funding

This work was supported by the Estonian Research Council grant (PRG1414 to E.O. and IUT2041 to V.V.) and an EMBO Installation grant (No. 3573 to E.O.). A. K. was supported by the University Tartu Foundation (CWT Estonia Traveling Scholarship) and the Ministry of Education and Research of Estonia (Kristjan Jaak National Scholarship). K.L.K was supported by the European Regional Development Fund (Smart Specialization PhD Scholarships).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.A., E.O., and V.V. conceptualized and supervised the study. I.R. and V.V. recruited study participants and organized sample collection and clinical monitoring. K.L.K. and A.K. performed DNA extraction and prepared metadata for microbiome analysis. A.K. performed the data analysis. A.K. and O.A. interpreted the data, prepared the figures, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Klemets, A., Reppo, I., Krigul, K.L. et al. Fecal microbiome predicts treatment response after the initiation of semaglutide or empagliflozin uptake. Sci Rep 16, 6126 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36318-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36318-3