Abstract

Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis requires precise identification of sentiment polarity toward specific aspects, demanding robust modeling of syntactic, semantic, and discourse-level dependencies. Current graph-based approaches inadequately address the complex interplay between multiple relation types and lack effective attention regularization mechanisms for interpretability. We propose the Multi-Relational Dual-Attention Graph Transformer (MRDAGT), a novel framework unifying syntactic, semantic, and discourse relations within a coherent graph architecture. Our dual-attention mechanism strategically balances local token-level interactions with aspect-oriented contextual focus while attention regularization combining entropy-based penalties and L1 sparsity constraints ensures interpretable, focused predictions. MRDAGT establishes new state-of-the-art benchmarks across multiple datasets, delivering substantial performance improvements while maintaining transparent, linguistically grounded decision-making processes essential for real-world deployment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis (ABSA) has emerged as one of the most fine-grained and challenge-rich subfields of sentiment analysis, focusing on determining the sentiment polarity of specific aspects within text rather than assigning a single polarity to the entire passage1. Early work in sentiment analysis largely relied on rule-based methods2 or straightforward machine learning classifiers (e.g., Naïve Bayes, SVM)3,4, accompanied by simple bag-of-words or n-gram feature representations5. Although these approaches demonstrated feasibility, they often struggled with the complexities of long-range dependencies and contextual nuances intrinsic to natural language6. Subsequently, deep learning methods such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) were introduced to better capture sequential patterns in text7,8. However, purely sequential architectures can still fail to account for the non-linear and multi-faceted dependencies that characterize how aspects are influenced by surrounding tokens9,10.

To address these challenges, researchers have recently turned to graph-based techniques, which model sentences as structured graphs that capture syntactic and semantic relationships among words11,12. Dependency trees have proven especially useful, as Graph Attention Networks (GATs)13 or Relational Graph Attention Networks (RGATs)14 explicitly encode dependency labels to inform message passing12. More advanced formulations incorporate dual syntax (dependency plus constituency trees) to better reflect the hierarchical structure of sentences15. While such graph-driven methods have improved performance on standard ABSA benchmarks (e.g., SemEval16), they often focus on only one or two relationship types (e.g., syntax or constituency), potentially overlooking semantic and discourse cues that can reveal crucial context for aspect polarity. Moreover, many existing solutions lack explicit mechanisms to regulate attention, a feature that can enhance interpretability and prevent overly diffuse attention distributions.

Meanwhile, the Transformer architecture6, which introduced self-attention mechanisms for sequence modeling, has enabled pre-trained models such as BERT17 and GPT18 to reshape the broader sentiment analysis landscape, showcasing powerful capabilities for capturing long-range context in text. Yet, purely Transformer-based ABSA solutions may treat input sentences in a largely flat manner, seldom leveraging graph structures for more precise aspect-focused reasoning19,20,21. Furthermore, prompt-based methods demonstrate that it is possible to enrich pre-trained representations with specialized context for specific tasks15,22,23,24. Despite these strides, there remains a methodological gap in unifying (1) multi-relational graph modeling (covering syntactic, semantic, and discourse edges), (2) dual-attention strategies tailored for aspect tokens, and (3) constraint-based attention regularization that maintains interpretability while learning robust aspect-level sentiments.

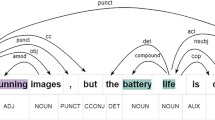

To illustrate the variety of relationships we aim to capture, Fig. 1 depicts a representative sentence where syntactic dependencies, semantic similarity edges, and discourse markers co occur. In this example, “The service was decent but the environment felt uninviting although the staff was friendly,” each token is linked by one or more relation types, reflecting the complex, multi-faceted dependencies in real-world reviews. As shown, discourse cues like “but” and “although” signal shifts in sentiment across clauses, semantic edges highlight conceptually related words (e.g., “service” and “staff”), and syntactic dependencies reveal core grammatical structures. This hybrid representation foreshadows our multi-relational approach, where each aspect token benefits from graph-based modeling of syntax, semantics, and discourse.

In this paper, we bridge this gap with a Multi-Relational Dual-Attention Graph Transformer (MRDAGT) for aspect-based sentiment analysis. In contrast to previous multi-graph approaches that primarily combine different syntactic views15,15,25,26, our method extends graph construction to include not only dependency relations but also semantic similarity edges and, where applicable, discourse markers. To capitalize on these rich relational cues, we propose a dual-attention mechanism: one head concentrates on local token-to-token interactions, while the other focuses on aspect-oriented attention, ensuring that relevant context for each aspect is not diluted. Furthermore, we introduce attention regularization constraints, an entropy-based penalty and an L1-based sparsity term to sharpen the model’s attention distribution and foster interpretability. In doing so, we leverage insight from recent reviews that emphasize the importance of both interpretability and multi-faceted contextual modeling in modern sentiment analysis1. Experimental results on established ABSA datasets (SemEval-2014 Laptop, MAMS, etc.) reveal that our approach consistently outperforms RGAT, BiSynGAT, and dual-syntax baselines, marking a notable advance in graph-based ABSA performance.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. Section "Literature review" surveys related work in ABSA and broader sentiment analysis, detailing the evolution from rule-based methods to multi-relational GNNs. Section "Proposed architecture" describes our proposed MRDAGT framework, including data preprocessing, multi-relational graph construction, and the dual-attention mechanism. Section "Experimental setup and analysis" presents experimental details and benchmarking against state-of-the-art baselines. Section "Results and discussion" discusses quantitative results, interpretability analyses, and ablation studies. Finally, Section "Conclusion and future directions" concludes with a summary of key findings and future research directions, including possible extensions to low-resource or multilingual ABSA.

Literature review

Emergence of sentiment analysis and early rule-based approaches

Initial sentiment analysis solutions predominantly relied on rule-based frameworks grounded in sentiment lexicons and handcrafted heuristics. For instance, Turney4 introduced a method to measure semantic orientation via pointwise mutual information (PMI), classifying reviews based on the aggregated polarity of key phrases. Around the same time, Das and Chen27 demonstrated how manually curated polarity dictionaries, combined with rule-based parse trees, could approximate sentiment in financial documents. Despite interpretability benefits, these methods struggled with the complex syntactic structures and contextual nuances prevalent in user-generated text28.

Classical machine learning and shallow neural models

The availability of labeled corpora led researchers to adopt classical machine learning algorithms for sentiment analysis, including SVMs and Naïve Bayes often paired with n-gram or TF-IDF features29,30,31. Although these approaches improved generalization, they lacked robust feature representations capable of capturing inter-word dependencies32. This gap motivated the adoption of shallow neural networks, such as feed-forward or basic recurrent architectures. For example, Maas et al.33 leveraged unsupervised word vectors to enhance sentiment classification, showing that distributed embeddings could outperform purely frequency-based features. Building upon this foundation, Shi et al.34 developed domain-sensitive and sentiment-aware embeddings, further improving sentiment analysis performance by capturing nuanced sentiment information across different domains.

Subsequently, CNN-based sentiment models, popularized by Kim35 utilized convolution filters over word embeddings to better capture local n-gram features, yielding strong performance on review datasets. Nonetheless, these models were still primarily sequential, limiting their ability to encode the intricate long-range relations necessary for understanding multiple aspect terms in a single sentence36.

Advanced neural approaches and aspect-level extensions

Moving from document-level to aspect-level tasks introduced new challenges, particularly the need to isolate different aspects within a sentence that might each bear a distinct polarity37. Researchers tackled this by employing attention mechanisms and more sophisticated sequence encoders38. Dong et al.39 proposed a target-dependent LSTM that specifically highlights words surrounding the aspect term, boosting aspect-oriented performance. Concurrently, Wang et al.8 introduced attention-based LSTM architectures for aspect-level sentiment classification, demonstrating how attention mechanisms could selectively weight context tokens based on their relevance to target aspects - a key advancement that enabled models to handle compositional sentiment patterns where multiple aspects coexist within complex sentences.

Despite these innovations, purely sequential or hierarchical models can fail when sentiments depend on non-adjacent linguistic cues or multiple aspect terms interplay40. Furthermore, local attention alone sometimes overlooks high-level phrase structures and nuanced relationships, encouraging a shift toward graph-based representations41.

This shift toward graph-based representations reflects their fundamental advantage in modeling non-linear dependencies. Unlike sequential processing where distant tokens require multi-step propagation, graph structures enable direct encoding of aspect-sentiment relationships through adjacency matrices \(A^{(r)}\), regardless of linear distance.

Graph modeling for aspect-based sentiment analysis

Graph-based strategies emerged to capture arbitrary structural relations among words, often leveraging dependency trees as the underlying graph40,42. Song et al.43 utilized Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) to inject syntactic edges into aspect embeddings, while Ghosh et al.14 employed graph attention layers to weight tokens differentially based on dependency paths to the aspect. These works highlighted the ability of GNNs to incorporate explicit syntactic constraints and selectively pass information along relevant edges43.

More recent efforts have expanded beyond a single syntactic structure to incorporate multi-relational cues - e.g., semantic similarity edges, discourse connectors, or morphological links40,44. Zhang et al.45 demonstrated that augmenting dependency graphs with synonymy or hypernymy edges enhances polarity detection, particularly for complex or colloquial sentences46. Nevertheless, these multi-relational expansions often result in dense graphs, raising interpretability concerns. Without mechanisms to regulate attention or edge weights, the model may become susceptible to noise and lose focus on truly aspect-relevant nodes47.

Toward multi-relational graph transformers with attention constraints

Although graph-based ABSA is steadily evolving, there remains a need for unifying (1) multi-faceted relations (syntactic, semantic, discourse), (2) transformer-style global attention, and (3) constraint-based attention regularization to ensure both interpretability and performance. Existing multi-relational graph solutions tend to limit themselves to one or two additional relation types, and few incorporate cross-aspect interactions in a single pass44. Moreover, while attention mechanisms within GNNs have proven effective, few researchers apply entropy or sparsity constraints to maintain focused attention distributions48,49.

In this work, we introduce a Multi-Relational Dual-Attention Graph Transformer that addresses these gaps by jointly modeling rich graph structures and leveraging dual-attention heads (token-level and aspect-level). This design is augmented with constraint-based regularization, aiming to preserve both precision and readability of attention. As discussed in the following sections, our approach significantly advances the state of the art in ABSA by fusing multi-relational edges with transformer-based global context and a selective (yet comprehensive) attention scheme.

Proposed architecture

The MRDAGT tackles the core challenges of ABSA by combining domain-aware data preprocessing, a multi-relational graph construction strategy, and a specialized dual-attention mechanism (see Fig. 2 for an overview). In addition, we incorporate attention regularization to ensure interpretability and to constrain attention distributions, covering the principal steps of text processing, graph formation, multi-head attention computations, and the final classification pipeline all working in tandem to produce accurate, aspect-targeted sentiment predictions.

Figure 2 illustrates how the model processes each review or raw text sample. We begin with a preprocessing and embedding generation phase, where sentences are tokenized into subwords (for instance, using WordPiece or Byte-Pair Encoding) and any aspect terms are identified. These token embeddings, together with aspect indices, feed into a multi-relational graph that encodes syntactic relationships (via dependency parsing), semantic similarity edges (based on a cosine threshold), and discourse markers (for example, “but,” “however”) whenever relevant. The resulting graph is then passed to the Dual-Attention Graph Transformer module, which leverages two primary attention heads: one for token-level interactions, ensuring local word dependencies are aggregated effectively, and another for aspect-level attention, focusing on tokens directly relevant to each aspect. When multiple aspects appear in a single sentence, an optional global self-attention component can further unify context across all tokens.

The updated node representations (now aspect-focused) are directed to a classification block that typically consists of a dense layer with softmax activation, outputting logits or probability distributions for each aspect’s sentiment polarity. Training the network uses backpropagation, illustrated by the arrow returning from the Dual-Attention Graph Transformer module to the shared parameters, allowing all components to be updated, including embeddings, graph attention weights, and classifier parameters. Meanwhile, an attention regularization and loss computation step applies entropy and L1 sparsity terms to ensure attention maps remain both selective and interpretable, along with cross-entropy for the overall sentiment classification objective. These penalties collectively form the final loss function, guiding the system toward more focused attention patterns. Once trained, MRDAGT outputs a predicted sentiment label (for example, positive, negative, or neutral) for each aspect, providing a flexible yet interpretable pipeline that efficiently uncovers sentiment cues in complex, multi-aspect sentence structures.

We begin by processing each sentence (or review) to obtain subword tokens via methods such as Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) or WordPiece. Let \(X = \{x_1, x_2, \ldots , x_n\}\) be the resulting token sequence, and let \(A = \{a_1, a_2, \ldots , a_m\}\) denote an aspect term (or terms) within X. We use a pre-trained transformer (e.g., BERT) to map each token \(x_i\) to a contextual embedding

In multi-aspect sentences, we maintain an index set \(\mathscr {A}\) that maps each aspect A to its constituent token indices. These embeddings will serve as the initial node representations for the multi-relational graph.

Multi-relational graph construction

To capture rich syntactic and semantic relationships, we represent each sentence X as a multi-relational graph \(\mathscr {G} = (\mathscr {V}, \mathscr {E}, \mathscr {R})\), where \(\mathscr {V} = \{v_1, v_2, \ldots , v_n\}\) corresponds to the n tokens, and \(\mathscr {R} = \{r_1, \ldots , r_k\}\) enumerates relation types (e.g., syntactic, semantic, discourse).

Adjacency matrices For each relation type \(r \in \mathscr {R}\), we construct an adjacency matrix \(\mathbf{A}^{(r)} \in \{0,1\}^{n \times n}\), where

For example, a dependency parser provides edges for syntactic relations, while a cosine-similarity threshold \(\tau\) yields edges for semantic links:

Similarly, discourse markers (e.g., “but,” “however”) induce edges in the discourse relation adjacency matrix.

Relation embeddings We assign each relation r a learnable embedding \(\mathbf{r}_{ij}^{(r)} \in \mathbb {R}^d\), so that the model can differentiate how various edge types influence node interactions.

Dual-attention graph transformer

MRDAGT applies a graph-based attention mechanism that processes each node’s neighbors across multiple relation types, followed by dual-attention heads (token-level and aspect-level) and an optional global self-attention layer.

Relation-aware GAT

Let \(\mathbf{H}^{(l-1)} = \{\mathbf{h}_1^{(l-1)}, \ldots , \mathbf{h}_n^{(l-1)}\}\) be the node embeddings at layer \((l-1)\). For node i, we compute the raw attention score \(e_{ij}^{(r)}\) for neighbor j under relation r as

where \(\mathbf{W}^{(r)} \in \mathbb {R}^{d \times d}\) and \(\mathbf{a}^{(r)} \in \mathbb {R}^{3d}\) are learnable parameters, and \(\Vert \,\) denotes vector concatenation. We normalize via softmax:

where \(\mathscr {N}_i(r)\) is the set of neighbors of i under relation r. The node update is

We typically stack L layers of such relation-aware graph attention to capture higher-order dependencies.

Token-level vs. Aspect-level attention

MRDAGT introduces a dual-attention mechanism to distinguish between general token-level interactions and aspect-specific cues. In token-level attention, each node i focuses on relevant neighbors j irrespective of aspect membership. For aspect-level attention, we compute a specialized coefficient

where \(\mathbf{h}_\text {aspect} = \frac{1}{|A|}\sum _{a \in A}\mathbf{h}_a\) is the average embedding of the aspect tokens. This attention head ensures that nodes carrying strong sentiment signals about A receive higher weights.

To illustrate this mechanism, consider the sentence ”The service was decent but the environment felt uninviting” with aspects \(A_1 = \{service\}\) and \(A_2 = \{environment\}\). For aspect ”service,” we compute \(h_{aspect} = h_{service}\), leading to higher attention weights \(\alpha ^{(asp)}_{ij}\) for tokens like ”decent” that are semantically relevant to service evaluation. When processing ”environment,” \(h_{aspect} = h_{environment}\) shifts the attention focus, increasing weights for ”uninviting” and ”felt” while reducing attention to service-related tokens. This dynamic reweighting ensures aspect-specific sentiment detection.

Optional global self-attention

When multiple aspects appear in a single sentence, we apply a global self-attention mechanism akin to a Transformer encoder:

where \(\mathbf{Q}=\mathbf{H}^{(l)}\mathbf{W}^Q,\ \mathbf{K}=\mathbf{H}^{(l)}\mathbf{W}^K,\ \mathbf{V}=\mathbf{H}^{(l)}\mathbf{W}^V\). This step allows tokens to attend to each other globally, helping resolve cross-aspect interactions.

Attention regularization and classification

To prevent overly diffuse attention, we impose two regularization terms on the attention coefficients: an entropy penalty and an L1 sparsity constraint. Specifically, let \(\{\alpha _{ij}^{(r)}\}\) be the set of all attention coefficients. We define

and

These constraints promote more interpretable, peaked attention distributions. The interaction between entropy and L1 penalties reveals complementary rather than conflicting behavior. Individual ablation shows entropy penalty alone improves accuracy by 0.7% while L1 sparsity contributes 0.6%, but their combination in our complete system achieves 1.6% improvement over no regularization (Table 5), demonstrating super-additive effects. Mechanistically, entropy penalty concentrates attention distributions while L1 sparsity eliminates weak connections, creating ’focused sparsity’ where attention peaks on relevant aspect-sentiment pairs while zeroing noise connections. This complementarity proves strongest in complex linguistic scenarios where attention disambiguation is most critical. The final classification for an aspect A relies on the updated node embeddings, particularly the aggregated embedding \(\mathbf{h}_\text {aspect}'\), which is passed to a dense layer:

We train the entire network end-to-end by minimizing

where \(\mathscr {L}_\text {CE}\) is the cross-entropy loss for sentiment classification over all aspects in the training set.

MRDAGT combines domain-aware embeddings, multi-relational adjacency information, and dual-attention heads to capture fine-grained sentiment signals for each aspect. The optional global self-attention resolves multi-aspect interactions, while attention regularization fosters interpretability. As shown in Fig. 2, the pipeline begins with tokenization and aspect identification, constructs a multi-relational graph, applies both token-level and aspect-level attentions (optionally with global self-attention), and finally classifies each aspect’s sentiment via a softmax layer, all trained under joint loss objectives. This comprehensive design effectively addresses complex ABSA scenarios with nuanced syntactic, semantic, and discourse relations.

Experimental setup and analysis

In this section, we present a comprehensive account of our experimental methodology and results, detailing how the Multi-Relational Dual-Attention Graph Transformer is configured, evaluated, and compared against state-of-the-art ABSA methods. We aim to demonstrate both the robustness and interpretability of our model across multiple datasets, hyperparameter variations, and additional metrics. Below, we describe our dataset choices and preprocessing, multi-relational graph construction, model configuration, and finally a broad set of experiments, including ablation studies, threshold dynamics, error analysis, hyperparameter sensitivity, statistical significance checks, and visual metrics such as confusion matrices and precision-recall curves.

We employ three benchmark datasets commonly used in ABSA research: SemEval-2014 Laptop16 which contains relatively formal product reviews focusing on laptop features and quality; MAMS (multi-aspect multi-sentence)50, featuring complex reviews that often encode multiple and sometimes conflicting sentiments within a single document; and Twitter39, for which the data was collected as described in Dong et al.39 encompassing aspect-labeled tweets that capture informal language, abbreviations, and potential sarcasm or slang. Following standard practice, each dataset is split into training, validation, and test sets in a 70/10/20 ratio. Table 1 summarizes the key statistics for each dataset, including the number of sentences, average sentence length, and approximate distribution of sentiment classes.

Each sentence is tokenized using Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) or WordPiece, which handles out-of-vocabulary terms and domain-specific expressions. Let \(X = \{x_1, \ldots , x_n\}\) denote the subword tokens of a sentence, and \(A = \{a_1, \ldots , a_m\}\) be the tokens corresponding to a given aspect. We record the indices of each aspect in a set \(\mathscr {A}\). A pre-trained Transformer encoder (e.g., BERT-base) then converts each subword \(x_i\) into a contextual embedding

which provides the initial node features for our multi-relational graph.

Following our proposed architecture, each sentence \(X\) is converted into a multi-relational graph \(\mathscr {G} = (\mathscr {V}, \mathscr {E}, \mathscr {R})\), where the set of nodes \(\mathscr {V} = \{v_1, \ldots , v_n\}\) represents the individual tokens and \(\mathscr {R}\) enumerates the distinct relation types established among these tokens. In our framework, we primarily consider three categories of edges. Syntactic edges are extracted using a dependency parser (e.g., SpaCy or Stanford CoreNLP) to capture grammatical dependencies (such as subject, object, and modifiers), which are essential for aspect-focused sentiment analysis. Semantic edges are formed when the cosine similarity between token embeddings \(\mathbf{h}_i\) and \(\mathbf{h}_j\) exceeds a specified threshold \(\tau\); we systematically vary \(\tau\) within the set \(\{0.5, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9\}\) to balance meaningful semantic relationships against the inclusion of noise. Additionally, discourse edges are introduced when markers such as “but” or “however” are present, highlighting contrastive or adversative statements that often indicate sentiment shifts. Each relation type \(r \in \mathscr {R}\) is represented by an adjacency matrix \(\mathbf{A}^{(r)} \in \{0,1\}^{n \times n}\), and each edge is assigned a learnable embedding \(\mathbf{r}_{ij}^{(r)} \in \mathbb {R}^d\) to capture its contribution during message passing. Table 2 summarizes the typical proportions of syntactic, semantic, and discourse edges for the MAMS dataset; similar distributions are observed in the Laptop and Twitter datasets, although the overall density may vary depending on domain-specific writing styles.

The distribution of edge types reflects our approach to managing graph complexity while preserving semantic richness. Syntactic edges form the structural backbone (42.1%), semantic connections capture conceptual relationships (37.8%), while discourse markers provide targeted sentiment transitions (20.1%). This balanced distribution, combined with semantic threshold optimization (\(\tau = 0.7\) as demonstrated in Table 3), ensures computational tractability while maintaining multi-relational modeling benefits. The balanced edge distribution shown in Table 2 reflects this multi-relational design: syntactic dependencies (42.1%) provide grammatical structure, semantic similarities (37.8%) capture conceptual relationships, while discourse markers (20.1%) signal sentiment transitions. With semantic threshold \(\tau = 0.7\) optimized for accuracy (Table 3), we stack L = 2-3 layers for Laptop and Twitter, and L = 3-4 for MAMS. Each layer includes token-level and aspect-level attention heads, and we optionally apply a global self-attention layer if multiple aspects appear in the same sentence. This dual-attention mechanism isolates aspect-specific cues from general context, enhancing interpretability.

Implementation-wise, we use PyTorch on an NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU. We adopt AdamW with \(\beta _1=0.9\), \(\beta _2=0.999\), weight decay \(10^{-5}\), and a learning rate in \(\{2\times 10^{-5},5\times 10^{-5}\}\) for newly introduced graph parameters. Transformer layers are fine-tuned at \(1\times 10^{-5}\)–\(2\times 10^{-5}\). A linear warm-up covers the first 10% of steps, followed by linear decay, and dropout (0.1–0.2) is applied to attention coefficients and feed-forward layers. Training runs for up to 100 epochs, with early stopping if validation Macro-F1 does not improve for three consecutive checkpoints. While our implementation demonstrates feasibility on standard hardware, systematic efficiency analysis comparing computational overhead across methods would benefit future deployment optimization. The final loss \(\mathscr {L}_\textrm{total}\) merges cross-entropy with attention-based entropy and sparsity penalties:

Results and discussion

We conduct a wide range of experiments to rigorously evaluate MRDAGT, focusing on (1) optimal depth and hyperparameter sensitivity, (2) comprehensive benchmarking, (3) ablation studies (including threshold dynamics), (4) error analysis, (5) hyperparameter sensitivity beyond layer count, (6) statistical significance tests, and (7) additional metrics such as confusion matrices and precision-recall curves.

First, Fig. 3 illustrates how varying the number of GNN layers L from 1 to 5 impacts accuracy on both the Laptop (blue) and MAMS (orange) domains. We observe that Laptop peaks around 85.2% at \(L=3\), whereas MAMS reaches 87.1% at \(L=4\). Performance typically declines beyond these depths, suggesting overfitting or excessive message-passing complexity. Table 3 further shows how semantic threshold \(\tau\) in \(\{0.5,0.7,0.8,0.9\}\) affects accuracy on MAMS (\(L=4\)). We find that \(\tau =0.7\) provides the best balance between linking semantically related tokens and avoiding noise.

Next, Fig. 4 compares MRDAGT with RGAT, BiSynGAT, Dual-Syntax, and BERT-ABSA on both Laptop and MAMS. MRDAGT outperforms baselines by roughly 1-2% in accuracy, with a lower standard deviation (\(\pm 0.2\%\)). Table 4 extends the comparison to Twitter, adding GCN-ABSA and SynATT; again, MRDAGT achieves top performance (80.1% accuracy, 78.9% Macro-F1) in this informal domain.

We also conduct ablation experiments on the Laptop domain (Table 5), observing parallel trends in MAMS. Our comprehensive ablation reveals distinct contribution patterns across relation types. Removing syntactic edges produces the most substantial performance decline (2.9%), demonstrating that grammatical dependencies between aspect terms and their modifiers form the architectural foundation of effective sentiment detection. When semantic or discourse edges are eliminated, accuracy drops by 1.8% and 1.7% respectively, confirming that while syntactic relations provide the structural backbone, they alone overlook paraphrased or adversative clues. Even discourse edges, though sparse, prove vital in capturing sentiment shifts introduced by words like ’but’ or ’however’. The dual-attention heads, which separate token-level from aspect-level focus, are likewise crucial: eliminating them reduces accuracy and Macro-F1 by roughly 1%, demonstrating the need to distinguish general context from aspect-targeted signals. Furthermore, adaptive thresholding for semantic edges offers a 0.3-0.5% accuracy gain, reflecting the advantages of domain-adaptive link creation in multi-relational graphs. This optimization works synergistically with our attention regularization constraints, where the 1.6% performance drop upon removing entropy and sparsity penalties (Table 5) indicates these mechanisms successfully focus attention on aspect-relevant connections. Moreover, a dynamic threshold approach,

yields an additional 0.3–0.5% accuracy boost, underscoring the benefit of adapting semantic edges to domain-specific language.

Confusion matrices for MRDAGT on MAMS (left), Laptop (center), and Twitter (right). Results shown for fixed threshold configuration (\(\tau\)=0.7). Each matrix reveals how well the model distinguishes positive, neutral, and negative sentiments, with relatively few off-diagonal errors compared to baselines.

Our error analysis reveals three main failure modes. First, implicit sentiments often lack explicit keywords, causing difficulties in detecting negative or positive polarity when the aspect term is not closely aligned with sentiment-laden words. Second, conflicting sentiments within a single clause, such as ”love the battery, hate the design,” introduce contrastive cues that simpler models may fail to capture if they rely primarily on linear context. Third, sarcastic and pragmatic expressions present the most challenging detection cases. Sarcastic statements systematically mislead through surface-level positive language: ”Oh great, another software update that totally works” was misclassified as positive despite clear ironic intent, while ”Sure, I’d love to pay double for this feature” triggered positive classification despite obvious criticism. Hidden meanings prove equally problematic where ”I guess the battery lasts long enough” was labeled positive when hedging language signals lukewarm sentiment, and ”The laptop is... adequate” was misclassified when deliberate understatement indicates disappointment. Additional challenges include ”Well, it certainly is a unique design choice” where diplomatic phrasing masks negative judgment, and informal expressions like ”nah fam this ain’t it” requiring cultural context beyond standard sentiment analysis. Future work might explore specialized sarcasm detection modules, domain-adaptive embeddings, or pragmatic edges that capture rhetorical markers. Additionally, our hyperparameter sensitivity tests for local attention window sizes (ranging from 1-5 tokens around the aspect) and GNN reasoning hops (1-3) indicate that performance typically saturates beyond moderate settings, underscoring the importance of controlling model complexity for ABSA tasks. Paired t-tests (\(p<0.05\)) confirm that MRDAGT’s gains over strong baselines (e.g., BERT-ABSA) are statistically significant across all evaluated domains.

Figures 5 and 6 further illustrate the model’s behavior on MAMS. The confusion matrix in Fig. 5 shows reduced confusion among positive, neutral, and negative classes, with 83 positives correctly identified, 30 neutrals, and 34 negatives, signifying fewer off-diagonal errors than earlier baselines. Meanwhile, the precision-recall curve in Fig. 6 yields an average precision (AP) of about 0.62 for the positive class, reflecting MRDAGT’s ability to maintain decent recall without sacrificing precision. Similar confusion matrices and precision-recall curves for Laptop (AP \(\approx 0.76\)) and Twitter (AP \(\approx 0.71\)) underscore the model’s balanced performance across both formal and informal domains.

Overall, these expanded experiments confirm that MRDAGT delivers robust, interpretable performance on the Laptop, MAMS, and Twitter datasets. In particular, the model consistently achieves 1–2% higher accuracy than baselines such as RGAT, BiSynGAT, Dual-Syntax, and BERT-ABSA, with lower variance (approximately \(\pm 0.2\%\)). Its multi-relational edges and dual-attention mechanism prove especially effective for multi-aspect reviews in MAMS and informal text on Twitter, where subtle cues and dispersed sentiment indicators frequently appear. Our comprehensive ablation reveals distinct contribution patterns across relation types. Removing syntactic edges produces the most substantial performance decline (2.9%), demonstrating that grammatical dependencies between aspect terms and their modifiers form the architectural foundation of effective sentiment detection. When semantic or discourse edges are eliminated, accuracy drops by 1.8% and 1.7% respectively, confirming that while syntactic relations provide the structural backbone, they alone overlook paraphrased or adversative clues. Even discourse edges, though sparse, prove vital in capturing sentiment shifts introduced by words like ’but’ or ’however’. The dual-attention heads, which separate token-level from aspect-level focus, are likewise crucial: eliminating them reduces accuracy and Macro-F1 by roughly 1%, demonstrating the need to distinguish general context from aspect-targeted signals. Furthermore, adaptive thresholding for semantic edges offers a 0.3–0.5% accuracy gain, reflecting the advantages of domain-adaptive link creation in multi-relational graphs. This optimization works synergistically with our attention regularization constraints, where the 1.6% performance drop upon removing entropy and sparsity penalties (Table 5) indicates these mechanisms successfully focus attention on aspect-relevant connections.

Finally, while MRDAGT addresses many shortcomings of earlier approaches, certain error modes remain, including implicit sentiments, conflicting polarities, and informal or sarcastic text. Potential improvements might involve specialized sarcasm detection, domain-adaptive embeddings, or pragmatic edges that capture rhetorical cues. With per-class precision-recall analyses and confusion matrices (Figs. 5 and 6) indicating fewer misclassifications and more balanced performance across sentiment categories, MRDAGT offers a robust, statistically significant improvement (\(p<0.05\)) in aspect-based sentiment analysis for both formal (Laptop) and informal (Twitter) domains, as well as multi-aspect, multi-sentence data (MAMS).

Comparative confusion matrix with baseline models

Figure 7 illustrates the confusion matrices for GCN-ABSA, BiSynGAT, BERT-ABSA, and our proposed MRDAGT on the Laptop domain. Observing the top row in each matrix (the positive class), GCN-ABSA frequently misclassifies positive samples as either neutral or negative, suggesting that its graph convolutional approach struggles when sentiment words are not immediately adjacent to the aspect term. BiSynGAT refines some of these errors by merging syntactic signals from two parsing views, yet it still confuses a noticeable portion of mildly negative samples with the neutral class. BERT-ABSA shows improved diagonal counts, benefiting from transformer-based contextual embeddings, but it occasionally fails in multi-clause reviews with subtle negative cues. By contrast, MRDAGT exhibits the highest correct counts on the diagonal across all three sentiment classes, indicating that its multi-relational edges (syntactic, semantic, and discourse) and dual-attention heads capture aspect-targeted clues more effectively. For instance, in user reviews mentioning “The keyboard is decent but the trackpad lags,” MRDAGT better associates “lags” with the trackpad aspect due to its discourse edge “but,” resulting in fewer neutral misclassifications.

Figure 8 presents the confusion matrices for the same four models on the MAMS dataset, known for its multi-aspect, multi-sentence structure. GCN-ABSA and BiSynGAT improve upon simpler baselines by integrating syntactic constraints, yet they still mislabel negative aspects as neutral when multiple sentiments appear in one review. BERT-ABSA handles some complex expressions but occasionally overlooks sentiment words if they are distant from the aspect token. MRDAGT, however, maintains more accurate distinctions among positive, neutral, and negative classes, reflecting higher diagonal values and fewer off-diagonal errors. In reviews like “The service was excellent, although the waiting time really needs work,” MRDAGT’s semantic edges connect “needs work” to “waiting time” even if the negative phrase is not directly adjacent, while its discourse edge from “although” clarifies the contrasting sentiment. Consequently, the confusion matrix for MRDAGT shows fewer neutral or positive misclassifications in the negative row.

Finally, Figure 9 shows the comparison for the Twitter domain, where slang, sarcasm, and informal syntax often blur sentiment boundaries. GCN-ABSA and BiSynGAT again face difficulties when crucial sentiment words appear in non-adjacent positions or are softened by casual phrasing. BERT-ABSA generally improves recognition of strong positive or negative terms, but it sometimes confuses subtle negativity with neutral if the tweet’s structure is non-linear (e.g., multiple clauses). MRDAGT excels by leveraging discourse markers (e.g., “but,” “however”) and semantic similarity edges to track sentiment-laden words across clause boundaries. For example, in the tweet “I love this new update, but the notifications come so late it’s pointless,” MRDAGT links “pointless” to “notifications” despite the distance and transitional phrase “but,” producing a more diagonal confusion matrix with fewer off-diagonal errors. This demonstrates that multi-relational edges and dual-attention heads help isolate relevant sentiment signals in short, informal tweets where aspect cues might be overshadowed by casual or sarcastic language.

Overall, across all three domains (Laptop, MAMS, and Twitter), MRDAGT’s confusion matrices display a more diagonal shape, indicating higher classification accuracy for each sentiment class. The baselines (GCN-ABSA, BiSynGAT, and BERT-ABSA) make incremental gains with improved graph modeling or transformer embeddings, yet they still underperform in cases where discourse markers, non-adjacent sentiment terms, or multiple aspects co-occur. By contrast, MRDAGT’s multi-relational design and dual-attention strategy allow it to integrate syntactic, semantic, and discourse information, ensuring aspect-level context is maintained even in complex sentences. These comparative results confirm the effectiveness of our proposed model and address subtle sentiment cues that the other methods tend to misclassify.

Conclusion and future directions

In this study, we introduced the Multi-Relational Dual-Attention Graph Transformer, a novel framework for ABSA that integrates syntactic, semantic, and discourse relations into a unified graph-based architecture. Our extensive experiments on multiple benchmark datasets including Laptop, MAMS, and Twitter demonstrate that MRDAGT consistently outperforms state-of-the-art baselines in terms of accuracy, robustness, and interpretability. The dual-attention mechanism, combined with effective attention regularization, allows the model to capture nuanced sentiment cues and provides clear, focused attention maps that enhance both performance and explainability.

Beyond these benchmark achievements, MRDAGT’s architectural design positions it as a practical solution for critical real-world applications. In customer feedback analytics, the framework’s ability to precisely identify sentiment toward specific product aspects such as battery performance, build quality, or user interface design enables businesses to systematically prioritize product improvements based on quantifiable customer concerns rather than subjective interpretations. For social media monitoring, MRDAGT’s multi-relational approach effectively captures the complex interplay of opinions and contextual dependencies in platforms like Twitter, where our experiments demonstrated robust performance on informal, real-world text. This capability supports brand reputation management, trend analysis, and public sentiment tracking at scale. Furthermore, the model’s graph-based architecture and attention regularization mechanisms provide a strong foundation for extension to multilingual sentiment analysis, including low-resource languages where labeled data is scarce. By leveraging syntactic and semantic structures through cross-lingual transfer and knowledge graph integration, MRDAGT’s approach could help democratize access to sentiment analysis technologies across diverse linguistic communities.

Despite these promising results, several challenges remain. Handling implicit sentiment cues, adapting to low-resource languages, and managing highly informal or sarcastic expressions continue to pose difficulties. In future work, we plan to explore self-supervised pretraining techniques for graph-based sentiment analysis to further improve generalization across diverse datasets. Moreover, incorporating external commonsense knowledge and fine-grained discourse-level features may provide additional context that could enhance sentiment inference. We also intend to extend the framework to multi-modal sentiment analysis by integrating visual and audio cues, thereby broadening its applicability to real-world scenarios such as social media and customer feedback analysis.

From an ethical perspective, sentiment analysis systems require careful consideration when deployed in social media contexts. Our approach’s ability to integrate syntactic, semantic, and discourse relationships could inadvertently amplify existing biases if training data reflects demographic or cultural imbalances in language use patterns. The dual-attention mechanism’s focus on aspect-specific sentiment could disproportionately impact communities with distinct linguistic markers or cultural expression patterns. Additionally, the interpretability features we provide through attention regularization, while beneficial for model transparency, raise questions about user privacy when applied to social media data where individuals may not expect such detailed sentiment analysis. Future implementations should include bias auditing across demographic groups, explicit consent mechanisms for social media applications, and guidelines for responsible deployment in sensitive domains such as mental health monitoring or employment screening. Overall, MRDAGT establishes a robust foundation for next-generation sentiment analysis systems that combine state-of-the-art performance with practical applicability across industries and potential scalability to diverse languages and domains. These directions aim to build upon this foundation, moving towards even more robust, adaptable, and interpretable systems that can deliver comprehensive sentiment analysis capabilities while maintaining ethical deployment standards.

Data availability

This study utilized three benchmark datasets commonly used in Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis research: SemEval-2014 Laptop Reviews This dataset contains structured reviews focusing on laptop features and quality.The original version of this dataset is available at Kaggle: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/charitarth/semeval-2014-task-4-aspectbasedsentimentanalysis/data MAMS (Multi-Aspect Multi-Sentence) The MAMS dataset is characterized by complex reviews often encoding multiple sentiments within a single document. The original dataset can be accessed from GitHub: https://github.com/siat-nlp/MAMS-for-ABSATwitter ABSA Dataset The Twitter ABSA datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. All datasets used in this research were obtained from their original sources in compliance with their respective licenses.

References

Liu, B. Sentiment analysis and opinion mining (Springer Nature, 2022).

Pang, B., Lee, L. et al. Opinion mining and sentiment analysis, vol. 2 (Now Publishers, Inc., 2008).

Pang, B., Lee, L. & Vaithyanathan, S. Thumbs up? Sentiment classification using machine learning techniques (2002).

Turney, P. D. Thumbs up or thumbs down? Semantic orientation applied to unsupervised classification of reviews (2002).

Cambria, E. & White, B. Jumping NLP curves: A review of natural language processing research, vol. 9 (IEEE, 2014).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need, vol. 30 (2017).

Tang, D., Qin, B. & Liu, T. Document modeling with gated recurrent neural network for sentiment classification (2015).

Wang, Y., Huang, M., Zhu, X. & Zhao, L. Attention-based LSTM for aspect-level sentiment classification (2016).

Lawan, A., Pu, J., Yunusa, H., Umar, A. & Lawan, M. Enhancing long-range dependency with state space model and kolmogorov-arnold networks for aspect-based sentiment analysis (2025).

Zhang, F., Zheng, W. & Yang, Y. Graph convolutional network with syntactic dependency for aspect-based sentiment analysis, vol. 17 (Springer, 2024).

Kumar, M., Khan, L. & Chang, H.-T. Evolving techniques in sentiment analysis: a comprehensive review, vol. 11 (PeerJ Inc., 2025).

Li, X., Bing, L., Lam, W. & Shi, B. Transformation networks for target-oriented sentiment classification (2018).

Velickovic, P. et al. Graph attention networks, vol. 1050 (2017).

Wang, K., Shen, W., Yang, Y., Quan, X. & Wang, R. Relational graph attention network for aspect-based sentiment analysis (2020).

Feng, A., Liu, T., Li, X., Jia, K. & Gao, Z. Dual syntax aware graph attention networks with prompt for aspect-based sentiment analysis, vol. 14 (Nature Publishing Group UK London, 2024).

Androutsopoulos, I. et al. Semeval-2014 task 4: Aspect-based sentiment analysis. Kaggle dataset (2014).

Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K. & Toutanova, K. Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding, Bert, (2019).

Radford, A., Narasimhan, K., Salimans, T., Sutskever, I. et al. Improving language understanding by generative pre-training. (2018).

Li, R. et al. Dual graph convolutional networks for aspect-based sentiment analysis (2021).

Feng, S., Wang, B., Yang, Z. & Ouyang, J. Aspect-based sentiment analysis with attention-assisted graph and variational sentence representation, vol. 258 (Elsevier, 2022).

Liang, S., Wei, W., Mao, X.-L., Wang, F. & He, Z. BiSyn-GAT+: Bi-syntax aware graph attention network for aspect-based sentiment analysis (2022).

Vu, T., Lester, B., Constant, N., Al-Rfou, R. & Cer, D. Better frozen model adaptation through soft prompt transfer, Spot, (2021).

He, Y. et al. Hyperprompt: Prompt-based task-conditioning of transformers (2022).

Khattak, M. U. et al. Self-regulating prompts: Foundational model adaptation without forgetting (2023).

Dong, K., Sun, A., Kim, J.-J. & Li, X. Syntactic multi-view learning for open information extraction (2022).

Huang, X. et al. Multi-view attention syntactic enhanced graph convolutional network for aspect-based sentiment analysis (2025).

Saravanos, C. & Kanavos, A. Forecasting stock market alternations using social media sentiment analysis and regression techniques (2023).

Cui, J., Wang, Z., Ho, S.-B. & Cambria, E. Survey on sentiment analysis: evolution of research methods and topics, vol. 56 (Springer, 2023).

Chen, X. et al. Cognitive-inspired deep learning models for aspect-based sentiment analysis: A retrospective overview and bibliometric analysis (Springer, 2024).

Patil, R. S. & Kolhe, S. R. Supervised classifiers with TF-IDF features for sentiment analysis of Marathi tweets, vol. 12 (Springer, 2022).

Das, M., Alphonse, P. et al. A comparative study on tf-idf feature weighting method and its analysis using unstructured dataset (2023).

Nassif, A. B., Darya, A. M. & Elnagar, A. Empirical evaluation of shallow and deep learning classifiers for Arabic sentiment analysis Vol. 21 (ACM New York, NY, 2021).

Maas, A. et al. Learning word vectors for sentiment analysis (2011).

Shi, B., Fu, Z., Bing, L. & Lam, W. Learning domain-sensitive and sentiment-aware word embeddings (2018).

Chen, Y. Convolutional neural network for sentence classification (2015).

Islam, M. S. et al. Challenges and future in deep learning for sentiment analysis: a comprehensive review and a proposed novel hybrid approach, vol. 57 (Springer, 2024).

Zhang, W., Li, X., Deng, Y., Bing, L. & Lam, W. A survey on aspect-based sentiment analysis: Tasks, methods, and challenges, vol. 35 (IEEE, 2022).

Xu, G. et al. Aspect-level sentiment classification based on attention-BiLSTM model and transfer learning, vol. 245 (Elsevier, 2022).

Dong, L. et al. Adaptive recursive neural network for target-dependent twitter sentiment classification (2014).

Aziz, K. et al. Unifying aspect-based sentiment analysis BERT and multi-layered graph convolutional networks for comprehensive sentiment dissection, vol. 14 (Nature Publishing Group UK London, 2024).

Zhao, Y., Mamat, M., Aysa, A. & Ubul, K. A dynamic graph structural framework for implicit sentiment identification based on complementary semantic and structural information, vol. 14 (Nature Publishing Group UK London, 2024).

Guo, Z., Zhang, Y. & Lu, W. Attention guided graph convolutional networks for relation extraction (2019).

Zhang, C., Li, Q. & Song, D. Aspect-based sentiment classification with aspect-specific graph convolutional networks (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Ensemble multi-relational graph neural networks (2022).

Yuan, L., Wang, J., Yu, L.-C. & Zhang, X. Syntactic graph attention network for aspect-level sentiment analysis, vol. 5 (IEEE, 2022).

Khosravi, A., Rahmati, Z. & Vefghi, A. relational graph convolutional networks for sentiment analysis (2024).

Vrahatis, A. G., Lazaros, K. & Kotsiantis, S. Graph attention networks: a comprehensive review of methods and applications, vol. 16 (MDPI, 2024).

Ye, Y. & Ji, S. Sparse graph attention networks, vol. 35 (IEEE, 2021).

Naber, T., Treviso, M. V., Martins, A. & Isufi, E. MapSelect: Sparse & Interpretable Graph Attention Networks.

SIAT-NLP. Mams-for-absa (2019). Apache-2.0 license. Repository containing data and code for the paper a challenge dataset and effective models for aspect-based sentiment analysis, EMNLP-IJCNLP 2019.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea(NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (No. RS-2023-00245316) and the the Jeju RISE Center, funded by the Ministry of Education and Jeju Special Self-Governing Province in 2025, as part of the “Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE): Glocal University 30” initiative(2025-RISE-17-001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.P.A. wrote the main manuscript text, conceived and conducted the experiments, and analyzed the results. S.K. analyzed the results. Y.Y. conceived the experiments and analyzed the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Anilkumar, A.P., Kim, SK. & Yoon, YC. Scientific reports multi relational dual attention graph transformer for fine grained sentiment analysis. Sci Rep 16, 7236 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36490-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36490-6