Abstract

This paper studies the participation of renewable-based microgrids in the retail market. The developed model is designed as a bi-level optimization approach. At the higher level, a distribution system operator (DSO), as the decision-maker for problem, takes part in the wholesale market to buy energy. Also, it participates in the retail market to increase its profit by selling energy to the microgrids. Moreover, at the upper level, in addition to supplying electrical energy, the provision of thermal energy to consumers is also considered, enabling the DSO to achieve greater profitability through improved efficiency. The lower level is responsible for modeling the interaction between the DSO and microgrids, where the microgrids aim to minimize their daily cost. In the proposed model, transactive energy and prices between the DSO and microgrids are the decision variables. Unlike existing models, microgrids can collaborate to convert the original non-cooperative games to hybrid cooperative and non-cooperative games. This change increases the bargaining power of microgrids and leads to a reduction in retail market prices and a decrease in microgrid operating costs. The results show that the proposed model improves operation cost and energy not supplied of microgrids by 9.09% and 33.56%, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Motivation

Renewable energy resources (RES) are known as clean energy resources that provide different environmental and financial benefits in the energy grid1,2. According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), the global renewable generation capacity in 2014 was 1829 GW and increased by 84.36% in 2022 and reached 3372 GW3. More than 60% of the annual electricity generation share in Denmark is formed by RES. Also, the share of RES in the energy portfolio of Spain, Germany, and Ireland is more than 30%4. With the penetration of RES, microgrid (MG) systems have been introduced that integrate the local generation, storage systems, and loads5,6. The MGs are low-voltage (or medium-voltage) small-scale systems that can be connected or disconnected from the main grid7,8. The MGs can be divided into single-carrier or multi-carrier systems. In the single-carrier systems, the MGs are only considered the electricity energy while in multi-carrier MGs the thermal loads have been considered9.

Literature review

Over the past few years, numerous studies have been focused on the sheduling and management of single and multi-carrier MGs. The authors in10 proposed a two-stage framework to manage the operation of MGs in real time. To this end, the renewable resources and battery storage system (BSS) were integrated into the system to maximize the profit of MGs. A decarbonization model has been developed in11 to manage the MGs in the isolated mode. The combined heat and power, boiler, and hydrogen storage were considered to increase the stability and reliability of the MGs. A two-layer model has been established in12 to provide flexible power scheduling in renewable MGs (RMG). In the first layer, the coordination among RMGs was studied, while the coordination between RMGs and the distribution system operator (DSO) was modeled in the second layer. Ullah et al.13 presented an energy scheduling model for hybrid MGs. The authors applied particle swarm optimization (PSO) and gravitational search algorithms (GSA) to model the energy trading between MGs. The main goal of the proposed model is to facilitate the integration of RES for cost reduction and decarbonization of distribution systems. Shahbazbegian et al.14 extended a multi-objective model to simultaneously optimize the operation cost, reliability, and trading energy with the main grid. In the presented method, the MGs include a fuel cell, electrolyzer, and hydrogen storage to increase short-term flexibility. During low-demand periods, the MG utilizes electrical energy to generate the hydrogen by electrolyzer units. The hydrogen produced can be stored in a storage tank to conduct into the fuel cell unit for electricity generation at peak hours. The application of integrated electrolyzer-fuel cell units significantly improved the flexibility of RMGs compared to their variable generations.

Recently, computational intelligence paradigms as well as metaheuristic algorithms extensively applicable in the operation planning of MGs. The authors in15 utilize the colored Petri net (CPN) and quantum-PSO algorithm for the economic operation of MGs. The proposed model incorporates RES, battery storage systems, and electric vehicles to present reliable scheduling. However, the direct trading between MGs was not studied. The authors in16 studied the performance of different algorithms such as PSO, genetic algorithm (GA), biogeography-based optimization (BBO), shuffled complex evolution (SCE), teaching-learning based optimization (TBLO), and harmony search (HS) to determine the optimal size of different technologies in MGs. These equipment consists of solar panels, wind turbines, battery storage, electrolyzer, and a hydrogen tank. The simulation results show that PSO and TBLO algorithms are more efficient. From the annualized system cost perspective. However, the impact of peer-to-peer trading between MGs on the optimal sizing was ignored. Alkuhayli et al.17 applied a multi-objective particle swarm optimization (MOPSO) algorithm to simultaneously minimize the total cost and emission of MGs. In the suggested algorithm, each MG performs a regional optimization for local generation resources and determines the shortage or surplus powers. In the next stage, a centralized optimization is used to define the amount of energy exchange among interconnected MGs. However, the heat demand and heat storage systems were not considered. The efficiency of demand response programs on the total cost of MGs was investigated in18 using the PSO algorithm. Zhang et al.19 developed a multi-objective model using PSO and gravitational search algorithms to enhance the proportion of electric vehicles in the MGs. However, the cooperation among MGs, and trading mechanism was not developed. A water wave optimization algorithm has been proposed in20 for optimal economic dispatch of MGs in the day ahead market. The proposed model considers both renewable, non-renewable generation resources and battery storage systems to provide an acceptable flexibility rate in the MG. However, the heat demand in MGs was not studied. Fatima et al.21 presented an economic dispatch model for MGs using bio-inspired optimization algorithms. The proposed model shows that the ant colony algorithm outperforms Binary PSO in the operating cost and peak load reduction. The authors utilize the fuel cell, microturbine, photovoltaic, wind energy, and storage systems to minimize total costs. Nevertheless, inter-MG cooperation and participation in the market were neglected.

One of the main challenges of MGs is their participation in the electricity market. Due to the small scale of MGs, they cannot directly participate in the wholesale market. However, different mechanisms have been presented to provide the opportunity to contribute to retail markets. The authors in22 developed a bi-level structure to model the participation of MGs in the retail market. The proposed model tries to minimize the operating cost and maximize the profit of MGs. However, the performance of the proposed model on the multi-energy systems was not evaluated. A multi-objective bi-level framework has been proposed in23 to model the contribution between MGs and DSO in the retail market. At the upper level, the DSO tries to maximize its profit, minimize load curtailment, and maximize the independence of the system by participating in both wholesale and retail markets. At the lower level, MGs try to minimize their cost by participating in the retail market and energy trading with DSO. However, the collaboration among MGs at the lower level was not implemented to reduce the market power of DSO. The interaction between MGs and DSOs in the retail market has been formulated as a bi-level problem in24 where the DSO decides to maximize its profit. However, the heat loads and daily transactive energy between DSO and MGs were not studied.

Research gaps

In most studies that have addressed the interaction between the DSO and RMGs, the main focus has been on meeting the electrical energy demand of consumers, while other energy requirements, particularly thermal energy needs, have largely been overlooked. Also, in these studies, the DSO interacts with each MG individually and sets different energy prices for each one. However, if the RMGs cooperate and establish a large coalition, they can increase their bargaining power and influence of the energy transaction prices with the DSO in their favor. Therefore, there is a need for a model that can simultaneously meet both electrical and thermal energy demands. Also, the impact of cooperation among RMGs on cost reduction requires further investigation.

Contributions

According to the literature, the major contributions of the proposed model can be listed as:

-

This paper reformulates the classical leader-follower framework into a leader and multiple followers framework for the operation of RMGs in the distribution network.

-

This paper modifies the existing competitive pricing model between the DSO and RMGs in the literature by reformulating it into a hybrid collaborative and non-collaborative framework. In the proposed model, the RMGs at the lower level can form a big coalition to reduce the bargaining power of the DSO and decrease the market prices.

-

The proposed model uniquely couples electrical and heating loads, and its performance is validated under different market conditions. The computational settings show the superior robustness and effectiveness compared to existing approaches.

Table 1 presents a summary of previous studies with evaluation metrics. According to Table 1, cooperation among RMGs at the lower level has not been examined in previous models, whereas this cooperation can increase the ability of RMGs to influence electricity prices and decrease the market power of DSO. Additionally, most research works focus solely on the electrical section, and the relationship between heating demand and supply has been overlooked.

Organization

Section 2 presents the mathematical formulation of the proposed model. The solution procedure of the proposed model is presented in Sect. 3. Case studies and simulation results are discussed in Sect. 4. Finally, the conclusion is presented in Sect. 5.

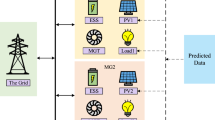

Formulation of the proposed transactive energy

This section models the trading electricity among DSO and RMGs in detail. The initial focus will be on describing the upper level of the optimization. Then the performance of RMGs at the lower level will be presented. The structure of the proposed model is shown in Fig. 1.

DSO profit at the upper level of model

In the upper level, DSO as the leader of problem attempts to maximize its profit. Due to the large scale of DSO, it contributes in the wholesale market to purchases electricity. Besides, it can utilize the local energy resources such as combined heat and power unit to generate the energy locally. To achieved financial profits, the DSO contacts with RMGs to sell the energy to them and get profit. The price of electricity exchange among DSO and RMGs is design by DSO. Naturally, the DSO needs an optimization problem to determine the optimal values for transactive prices. The objective of DSO is shown in Eq. (1).

The first term of objective function defines the revenue from energy trading with RMGs. Where \(\:{P}_{m}^{t}\) shows the traded electricity between DSO and RMG m at price \(\:{\rho\:}_{m}^{t}\). The second term refers to total cost of the DSO. The first term in cost function shows the purchasing energy from the wholesale market. \(\:{P}_{grid}^{t}\:\)refers to amount of purchasing electricity and \(\:{\rho\:}_{grid}^{t,s}\) is the wholesale prices in scenario s. Also, \(\:{\sigma\:}^{s}\) is probability of scenario s. The second and third terms of cost function model the fuel cost and maintenance costs of CHP unit, respectively. \(\:{\rho\:}_{gas}^{t}\) refers to natural gas prices and \(\:{\rho\:}_{CHP}^{O\&M}\:\)shows the maintenance cost of CHP unit. Also, \(\:{G}_{CHP}^{t}\) is the consumed natural gas by CHP unit. \(\:{P}_{e,CHP}^{t}\) and \(\:{H}_{h,CHP}^{t}\) refer to generated electricity and heat by CHP unit, respectively. The fourth and fifth terms of the cost function describe the fuel cost and maintenance costs of boiler, respectively. \(\:{G}_{CHP}^{t}\) and \(\:{H}_{B}^{t}\) refer to input natural gas into boiler and generated heat by boiler, respectively. Finally, \(\:{\rho\:}_{B}^{O\&M}\) shows the maintenance costs of boiler. The main difference in the objective function compared to previous studies is the inclusion of terms (3) to (6), as earlier works focused solely on the supply of electrical energy. Moreover, in this model, the energy exchange price between the DSO and RMGs is not fixed and is determined through the optimization process based on their interaction.

The DSO utilizes from battery storage system to store the electricity when the prices are low. The stored energy can be discharged into the system to sell it to RMGs. The constraints of battery storage system are presented in Eqs. (2)-(7)25,26.

The battery storage system’s charging and discharging boundaries are described in Eq. (2) and Eq. (3), respectively. \(\:{P}_{ch}^{t}\) and \(\:{P}_{dch}^{t}\) refer the rate of power input and output in battery storage, respectively. \(\:{P}^{ch,max}\) and \(\:{P}^{dch,max}\) are the maximum charging and discharging powers, respectively. Also, \(\:{b}_{ch}^{t}\) and \(\:{b}_{dch}^{t}\) are the binary variables that show the charging and discharging status of battery storage system. \(\:{SoC}_{t}\) is the state of charge of battery storage system. Also, charging and discharging efficiency of battery storage system are shown by \(\:{\eta\:}_{ch}^{bs}\) and \(\:{\eta\:}_{dch}^{bs}\), respectively. Equation (5) presents the minimum and maximum remaining charge in the battery storage unit. \(\:{SoC}^{min}\) and \(\:{SoC}^{max}\) describe the lower and upper allowable charge levels of the battery systems, respectively. Equation (6) determines the input and output power of battery storage system during the day should be equal. Finally, Eq. (7) prevents from charging and discharging of battery storage system at same time.

Also, the DSO is able to utilize the boiler and CHP units to generate the heat energy for the system. Equations (8)-(10) represent the operation limits of boiler27.

Equation (8) shows the generated heat of boiler. Also, Eqs. (9) and (10) state the maximum generating head and input natural gas to boiler. \(\:{\eta\:}^{boiler}\) show the efficiency of boiler. \(\:{H}_{B}^{max}\) and \(\:{G}_{B}^{max}\) are the maximum generating heat and input natural gas to boiler. However, the operating limits of CHP is presented in Eqs. (11)-(13).

Equations (11) and (12) model the generating electricity and heat of CHP, respectively. \(\:{\eta\:}^{e,CHP}\) and \(\:{\eta\:}^{h,CHP}\) are the electrical and thermal efficiency of CHP, respectively. Also, Eq. (13) states the input natural gas limits for CHP, where \(\:{G}_{CHP}^{max}\) refers to maximum natural gas of CHP unit.

Similar to battery storage system, DSO operates the heat storage to increase its flexibility. Equations (14)-(19) demonstrate the formulation of heat storage systems28.

Equations (14) and (15) show the charging and discharge limits of heat storage, respectively. The stored heat, and its bounds are presented in Eqs. (16) and (17), respectively. Also, Eq. (18) defines the input and output heat of heat storage system during the day should be equal. Finally, Eq. (19) prevents from charging and discharging of heat storage system at same time. \(\:{H}_{ch}^{t}\) and \(\:{H}_{dch}^{t}\) are the charging and discharging heat, respectively. \(\:{H}^{ch,max}\) and \(\:{H}^{dch,max}\) represent the maximum charging and discharging heat, respectively. \(\:{SoC}_{t}^{h}\), \(\:{SoC}^{h,min}\), and \(\:{SoC}^{h,max}\) refer to stored heat, minimum stored heat, and maximum stored heat of storage system. \(\:{\eta\:}_{ch}^{hs}\) and \(\:{\eta\:}_{dch}^{hs}\) show the efficiency of the storage system during charging and dischargig., respectively. Finally, \(\:{k}_{ch}^{t}\:\)and \(\:{k}_{dch}^{t}\:\)are binary variables used to specify charging and discharging operation modes.

The electrical and heat balances are provided in Eqs. (20) and (21), respectively. The Eq. (22) limits the purchasing electricity from wholesale market. Finally, Eq. (23) shows the maximum value for retail prices. In the following equations, \(\:{H}_{dem}^{t}\), \(\:{P}^{max}\), and \(\:{\rho\:}_{m}^{max}\) are the heat demand, maximum energy trading in wholesale market, and maximum retail prices, respectively.

Renewable microgrids at the lower level of model

At the lower level, the RMGs consider their local resources (as well as renewable generation and dispatchable resources), penalty cost for load shedding, and their potential for participation in retail market to minimize their operating costs. In the retail market, RMGs can contact with DSO to purchase electricity and supply their demands. The electricity prices are design at the upper level of optimization by DSO and RMGs determine their imported electricity based on the electricity prices. Each RMG considers its own operating cost as objective function at the lower level as Eq. (24).

The first part of the objective function represents the expense of buying electricity from the DSO. The second part shows the generation cost of fuel cells. The third term shows the operating cost of microturbines. The fourth and fifth parts show the maintenance costs of PV and WT supplies, respectively. Finally, sixth term defines the penalty cost for load curtailment. \(\:{C}_{FC,m}^{fuel}\) and\(\:\:{C}_{FC,m}^{O\&M}\) present the fuel cost and maintenance cost of FC unit. The \(\:{C}_{MT,m}^{fuel}\) and \(\:{C}_{MT,m}^{O\&M}\) define the fuel cost and maintenance cost of microturbine. \(\:{C}_{PV,m}^{O\&M}\) and \(\:{C}_{WT,m}^{O\&M}\)are the maintenance cost of PV and WT, respectively. \(\:{P}_{FC,m}^{t}\), \(\:{P}_{MT,m}^{t}\), \(\:{P}_{PV,m}^{t}\), and \(\:{P}_{WT,m}^{t}\) are the power generation of fuel cell, microturbine, PV, and WT, respectively. Also, \(\:{C}_{IL}^{m}\) and \(\:{P}_{IL,m}^{t}\) show the penalty cost and amount of load curtailment, respectively. Also, the following equations model the lower level problem.

Equation (25) presents the minimum and maximum generation of fuel cell. The ramp-up and ramp-down limits of fuel cell are described in Eqs. (26) and (27), respectively. The generating limit of microturbines is demonstrated in Eq. (28). Equations (29) and (30) show the ramp-up and ramp-down limits of microturbines. The trading electricity among DSO and RMGs is shown by Eq. (31). Equation (32) limits load curtailments in RMGs. Finally, the electricity balance between generation and load in each RMG is shown in Eq. (33). \(\:{P}_{FC,m}^{max}\) and \(\:{P}_{FC,m}^{min}\) show the minimum and maximum generation of fuel cell, respectively. \(\:R{U}_{m}^{FC}\) and \(\:R{D}_{m}^{FC}\) explain the fuel cell’s ramp-up and ramp-down power capabilities., respectively. \(\:{P}_{MT,m}^{max}\) and \(\:{P}_{MT,m}^{min}\) refer to the maximum and minimum generation of microturbine, respectively. \(\:R{U}_{m}^{MT}\) and \(\:R{D}_{m}^{MT}\) define the ramp-up and ramp-down power of microturbine, respectively. \(\:{P}_{m}^{max}\) is the maximum energy trading between DSO and RMGs, respectively. Finally, \(\:{P}_{IL,m}^{max}\) refers to maximum load shedding of RMGs.

Solution procedure of bi-level problem

To solve the optimization problem, the Karush–Kuhn–Tucker conditions (KKT) is used to convert the bi-level interaction between DSO and RMGs in the retail market into the single-level. In this technique, the upper-level variable (retail prices) is considered as parameter in the RMGs. To this end, the lower-level Eqs. (25)-(33) can be rewrite as29,30:

According to Eqs. (34)-(46), the Lagrangian function corresponding to the lower-level problem. is described as (47).

In the above equations, variables \(\tau \:_k^{m,t} \geqslant \:0\) and \(\:{\lambda\:}_{m,t}\) refer to dual variables of lower level. Also, the following constraints should be applied in the lower level31.

Each inequality complementarity condition \(\:0\le\:P\perp\:\tau\:\ge\:0\:\) can be replaced with:

M represents a large constant, and b refers a binary variable. Finally, the following equations should be performed to define the optimal energy exchange and transactive prices among RMGs and DSO.Subject to:Equations (2)-(23),and (48)-(66)

Case study and numerical results

In this section, the case study, input data, and numerical results are discussed. The suggested approach is evaluated on a standard distribution system consisting of one DSO and four renewable microgrids. The DSO operates one battery storage system, one boiler, CHP, and one heat storage system. The DSO is able to purchase maximum 14 MWh from wholesale market. Also, maximum electricity exchange between each RMG and DSO in the retail market is considered 4 MWh. The electrical and thermal efficiency of the CHP unit are 35% and 40%, respectively32. The maximum input natural gas into CHP and boiler is 1000 m3/h. Also, the maintenance costs of the boiler and CHP are considered 13 $/MWh and 11 $/MWh, respectively. The parameters of the electrical and thermal storage systems are taken from33,34 and show in Table 2.

On the other hand, the microgrids are formed from PV, WT, fuel cell, and microturbine resources. The capacities of fuel cell units are taken from35 and are considered 2000 kWh, 1500 kWh, 1000 kWh, and 2000 kWh for RMGs 1–4, respectively. Both ramp-up and ramp-down powers of fuel cells are assumed 500 kW. Also, the maximum capacity of microturbine units is 2000 kWh, 1500 kWh, 2500 kWh, and 1500 kWh in microgrids, respectively. Besides, both ramp-down and ramp-up ranges are assumed 500 kW. The penalty for load shedding are assumed 130 $/MWh, 110 $/MWh, 120 $/MWh, and 108 $/MWh for microgrids 1–4, respectively. Figure 2 shows the electrical and heat loads.

Figure 2 shows the hourly day-ahead forecasted electrical and heat load profiles for different RMGs. These forecasted load profiles reflect daily demand patterns, show the peak and off-peak duration, and serve as the input data for the scheduling decisions of both the DSO and the RMGs in the proposed cooperative and non-cooperative model. Also, the maximum retail prices, transactive prices between RMGs and DSO, are considered 50 $/MWh, 92 $/MWh, and 127 $/MWh during off-peak, mid-peak, and peak hours, respectively.

Non-cooperative mechanism results

This section examines the performance of RMGs under the non-cooperative. In this operation scheduling, the RMGs are not able to exchange energy with each other and cooperation among RMGs is neglected. In the non-cooperative mode, the profit of DSO is $ 6334.76. Figure 3 shows the operating costs and energy not supplied (ENS).

Figure 3 shows that the RMG 2 is not able to fully meet its load, and the ENS in this RMG is 3730 kWh, while other RMGs can meet their consumption. The RMG 2 has the highest load profile, and its distributed generation resources cannot supply its load. Since RMG 2 has the highest load profile, its cost is more than that of other RMGs, while the cost of RMG 3 is less than that of other MGs. The RMG 2 needs to purchase more energy from the DSO. Therefore, it increases the operating cost of RMG 2. Figure 4 shows the hourly generation of fuel cell units.

It can be seen that the RMGs operate the fuel cell units during hours 8–23. During the off-peak period (hours 1–7), the RMGs do not turn on the fuel cell units because they can purchase electricity from the DSO at lower prices. However, during peak hours, the DSO set higher prices for electricity in the retail market. Therefore, the RMGs operate their fuel cell units to reduce the imported electricity from the DSO and decrease their cost. Also, the results show that the RMG 2 operates its fuel cell at maximum capacity because it has the maximum load compared to other RMGs. Figure 5 presents the hourly retail prices between DSO and RMGs.

The results of Fig. 5 show that the electricity tariffs are designed at the maximum value during off-peak hours. The maximum electricity tariffs during off-peak hours are 50 $/MWh. However, this price is less than the marginal cost of distributed energy sources in the RMGs. Therefore, the DSO sets the prices at their maximum value to get maximum income from the RMGs. Also, the DSO knows that by setting the maximum value during off-peak hours, the RMGs will purchase energy from it. On the other hand, during the mid-load and peak-load periods, the DSO sets the electricity price below the maximum allowable level (92 $/MWh and 127 $/MWh for mid and peak hours, respectively). At these times, if the maximum value is set, the RMGs prefer to meet loads by their local generation sources. Therefore, they will decrease their electricity exchange with the DSO. To encourage the RMGs to buy energy from DSO and thereby earn profit, the DSO sets the electricity prices less than maximum values to sell more energy. Figure 6 presents the purchased electricity from the DSO by RMGs.

The results of Fig. 6 show that during peak hours, RMG 2 continues to purchase energy from the retail market, while the other RMGs reduce their exchanges and prefer to operate their local resources. Since RMG 2 has a small-capacity fuel cell unit, it purchases the electricity from DSO during peak hours to prevent excessive load shedding. However, the other RMGs have the capability to increase their local generation and thereby reduce the purchased energy from the DSO to reduce their operating costs. Figure 7 provides the heat energy provided by DSO.

The results in Fig. 7 show that the CHP is the primary source for meeting the required heat energy. During off-peak hours, the boiler unit is operated at its maximum capacity to supply the required heat energy, while the remaining heat is met by the CHP. The DSO prefers the boiler because it has a lower maintenance cost compared to the CHP unit. However, during peak hours, the DSO operates the CHP unit near maximum capacity to produce electricity and sell it to RMGs. Therefore, their generated heat is increased, and no need for boiler units.

To investigate the performance of the proposed model with respect to computational parameters, the Retail Price Coefficient (RPC) is introduced, which presents the scale of electricity prices compared to the base case (50 $/MW, 92 $/MW, and 127 $/MW so far during off-peak, mid-peak, and peak periods, respectively). The RPC is changed from 0.8 to 1.4, and the numerical results are presented in Table 3.

A value greater than 1 for this RPC shows that the retail prices have increased, whereas a value less than 1 indicates a decrease in prices compared to the base case. According to Table 3, when the RPC is set to 0.8, the operating cost of RMGs is less than in other cases. This value forces the DSO to set lower electricity prices for energy trading with RMGs. Therefore, the RMGs can purchase the electricity at lower prices and reduce their cost. By increasing the RPC, the DSO can set higher electricity prices for energy trading with RMGs, and it increases the total cost of RMGs. In this case, by increasing RPC from 0.8 to 1.4, the total cost of RMGs has increased from $ 25222.2 to $ 32395.55. Actually, by increasing RPC from 0.8 to 1.4, the total cost of RMGs is increased by 28.4%. It should be noted that the simulation run time of the proposed model is less than 20 s and can be easily applied for the operation of RMGs.

Also, a sensitivity analysis is performed on the scale of RMGs. The electrical consumption of RMGs is changed, and the profit of the DSO and cost of RMGs are presented in Fig. 8. The Electrical Demand Coefficient (EDC) is introduced, which presents the scale of electricity demand compared to the base case.

The numerical results show that by increasing EDC, the proposed model increases the profit of DSO from $ 3933 to $ 7989.6. The main reason for this profit increase is that the DSO can sell more energy to RMGs and get more profit. Also, it increases the operation cost of RMGs by 64.68% and increases from $ 21,900 to $ 36,067 because they must generate more energy from their local resources or purchase more energy from the DSO.

Cooperative mechanism results

This section considers the ability of cooperation among RMGs at the lower level and converts the leader and multi-followers problem into leader and single-follower. This model provides the opportunity of local trading among RMGs and increases their bargaining power to reduce the retail market prices. Table 4 compares the performance the proposed cooperative model with the previous non-cooperative model.

It can be seen that the cooperation among RMGS reduces the operating cost of RMGs by 9.1% and results in a reduction from $ 28901.77 to $ 26271.75. Unlike the previous non-cooperative mode, in the cooperative mode, each RMG is able to import electricity from other neighboring RMGs. As a result, each RMG can compare the design prices by the DSO and prices of other RMGs to purchase energy at a lower cost. Also, this cooperation reduces the profit of DSO by 33.07% because the DSO must adjust retail market prices less than in the non-collaborative mechanism to prevent market loss and encourage the RMGs to procure energy. However, the proposed model reduces the load shedding from 3730 kWh to 2478 kWh because each RMG can make its reserves available to other RMGs to prevent load shedding. The designed retail prices between the DSO and RMGs are shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 9 shows that the DSO sets retail market prices significantly less than the maximum value to sell more energy to RMGs and earn a profit. A comparison with Fig. 5 shows that the designed prices in this mode are lower than in the non-collaborative mechanism because the proposed model increases the bargaining power RMGs by cooperation in a lower level. If the DSO sets prices similar to the non-cooperative mode, the RMGs will utilize their local resources, cover their shortages through other RMGs, and their exchanges with the DSO will significantly decrease. For this reason, the DSO sets prices lower than in the non-cooperative mode to continue selling energy to the RMGs. However, during off-peak hours, the DSO sets the maximum values for retail market tariffs because the maximum value is less than the generation cost of local resources in RMGs, and they will purchase energy from it. It should be noted that the required computational times in the non-cooperative mechanism (case study 1) and the hybrid mechanism (case study 2) are 6.97 s and 4.7 s, respectively.

To consider the efficiency of uncertainty on the proposed model, a scenario-based model is performed on the wholesale electricity prices. The complete equations and algorithm of the scenario-based model can be found in36. Figure 10 shows different scenarios for wholesale market prices.

Figure 10 shows the hourly forecasted scenarios for the wholesale electricity prices. The seven scenarios describe possible variations around the expected forecast prices. These scenarios are considered to model the impact of the uncertainty on the proposed cooperative and non-cooperative model. The impacts of these price scenarios on the profit of the DSO and total operating cost of RMGs are studied in Fig. 11. The probabilities of scenarios 1–7 are 0.0062, 0.0606, 0.2417, 0.3829, 0.2417, 0.0606, and 0.0062, respectively. Figure 11 shows the efficiency of the developed cooperative model with non-cooperative mechanism using different uncertainty modeling.

The results of Fig. 11 indicate that in different deterministic, stochastic, and robust models, the proposed cooperative model has better performance than the non-cooperative model. In the deterministic approach, the cooperation among RMGs reduces their operating cost by 9.1% and decreases from $ 28,901 to $ 26,271. In the stochastic approach, this cooperation reduces the operating cost of RMGs by 6.01% and reduces it from $ 28879.88 to $ 27143.55. The robust approach decreases the operating cost of the RMGs by 405.87. The key reason for cost reduction in the proposed model is that the cooperation among RMGs reduces the market power of the DSO, and it is forced to set the electricity prices less than in the non-collaborative mechanism. Also, the developed cooperative approach enables the local trading among RMGs to exchange energy with neighboring RMGs.

Also, Fig. 11 shows that the profit of DSO in the cooperative mode is less than in the non-collaborative mechanism in all of the uncertainty approaches. A comparison between different conditions shows that the robust optimization creates a higher operating cost for RMGs and a minimum profit for the DSO. In the robust optimization, the worst scenario (high prices) is considered for the wholesale prices. Therefore, the DSO pays more money, and it decreases its profit. Since the DSO buys the electricity at higher prices, it designs the higher prices for the retail market for energy trading with the RMGs. Therefore, the RMGs must purchase the electricity at higher prices than the stochastic or deterministic approaches. This increases the operating cost of the RMGs.

Table 5 shows the optimization statistics of the proposed model. According to Table 5, the proposed model has 6047 single constraints, 5545 single variables, and 1632 discrete variables. The proposed model is formulated as a Mixed-Integer Nonlinear Programming (MINLP) model and is solved using the General Algebraic Modeling System (GAMS) under the LINDO solver. The simulation run time is 384 s.

Conclusion

In this paper, we developed a cooperative bi-level approach that studies the interaction between distribution system operators and microgrids in integrated energy systems. In the proposed model, the distribution system operator is an interface between wholesale and retail markets. It contributes to the wholesale market by purchasing electricity and selling it in the retail market to renewable microgrids. Also, it is responsible for supplying the heat demands of the system. Renewable microgrids as local energy systems integrate the loads, photovoltaic, wind energy, and dispatchable resources in order to minimize their operation costs. Also, they can sell energy from distribution system operators in the retail market. To increase the bargaining power of microgrids in the retail market, they can cooperate to provide P2P energy trading in the system. The simulation results show that this cooperation considerably reduces the retail prices between microgrids and distribution system operators. As a result, this cooperation decreases the operating cost of microgrids by 9.1%. In future works, the water and hydrogen systems will be integrated into the proposed model.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bourek, Y., Ammari, C., Zouaghi, A. & Pace, L. Optimization and decision-making approach for energy storage strategies in a natural gas processing facility with photovoltaic renewable energy supply. J. Energy Storage. 112, 115431 (2025).

Pirmohammad Talatape, Mojtaba, R., Ghanizadeh, S., Bagheri & Mohammad Reza Miveh. and. Management of Distributed Energy Resources for Reducing Environmental Pollution and Enhancing Economic Efficiency. Power, Control, and Data Processing Systems, vol. 2, (4) e728794. https://doi.org/10.30511/pcdp.2025.2063381.1031 (2025).

Xiong, C., Su, Y., Wang, H., Zhang, D. & Binyu Xiong. Optimal distributed energy scheduling for Port microgrid system considering the coupling of renewable energy and demand. Sustainable Energy Grids Networks. 39, 101506 (2024).

Nguyen, T., Thanh, T. T., Nguyen & Hoai Phong, N. Optimal operation of battery energy storage system in microgrid to minimize electricity cost based on model predictive control using Coyote algorithm. J. Energy Storage. 114, 115904 (2025).

Samadi Gharehveran, S. A Review of Energy Management of Multi-microgrid Power Systems in the Presence of Uncertainty of Distributed Generation Resources. Power, Control, and Data Processing Systems, vol. 2, no. 4, e731409, (2025). https://doi.org/10.30511/pcdp.2025.2072671.1046

Yi, Y., Xu, J. & Zhang, W. A low-carbon driven price approach for energy transactions of multi-microgrids based on non-cooperative game model considering uncertainties. Sustainable Energy Grids Networks. 40, 101570 (2024).

Azimian, M., Habibifar, R., Amir, V., Shirazi, E. & Javadi, M. S. Ali Esmaeel Nezhad, and soheil Mohseni. Planning and financing strategy for clustered multi-carrier microgrids. IEEE Access, 11, 72050–72069 (2023).

Lu, J., Hu, J., Cao, J. & Jie Yu, and Two-stage robust scheduling and real-time load control of community microgrid with multiple uncertainties. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 155, 109684 (2024).

Carvallo, C., Moreno, R. & Francisca Jalil-Vega, and A multi-energy multi-microgrid system planning model for decarbonisation and decontamination of isolated systems. Appl. Energy. 343, 121143 (2023).

Ranjbar, G., Abbas, M., Simab, M., Nafar & Zare, M. Day-ahead energy market model for the smart distribution network in the presence of multi-microgrids based on two-layer flexible power management. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 155, 109663 (2024).

Ullah, Z. et al. Hasanien. Optimal energy trading in cooperative microgrids considering hybrid renewable energy systems. Alexandria Eng. J. 86, 23–33 (2024).

Shahbazbegian, V., Shafie-khah, M. & Laaksonen, H. Goran Strbac, and Hossein Ameli. Resilience-oriented operation of microgrids in the presence of power-to-hydrogen systems. Appl. Energy. 348, 121429 (2023).

Liu, X. M., Zhao, M., Wei, Z. H. & Lu, M. The energy management and economic optimization scheduling of microgrid based on colored petri net and Quantum-PSO algorithm. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 53, 102670 (2022).

Phan-Van, L., Takano, H., Tuyen Nguyen & Duc A comparison of different metaheuristic optimization algorithms on hydrogen storage-based microgrid sizing. Energy Rep. 9, 542–549 (2023).

Alkuhayli, A., Dashtdar, M., Flah, A., Blazek, V. & Lukas Prokop. and. Designing a multi-objective energy management system in multiple interconnected water and power microgrids based on the MOPSO algorithm. Heliyon, vol. 10, No. 10, (2024).

Sun, H., Cui, X. & Latifi, H. Optimal management of microgrid energy by considering demand side management plan and maintenance cost with developed particle swarm algorithm. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 231, 110312 (2024).

Zhang, X., Wang, Z. & Lu, Z. Multi-objective load dispatch for microgrid with electric vehicles using modified gravitational search and particle swarm optimization algorithm. Appl. Energy. 306, 118018 (2022).

Huynh, D. C. et al. Water wave optimization Algorithm-Based dynamic optimal dispatch considering a Day-Ahead load forecasting in a microgrid. IEEE Access, 12, 48027–48043 (2024).

Fatima, I. et al. Muhammad Atif, and Sultan AlYami. Enhancing Grid-Connected microgrid power dispatch efficiency through Bio-Inspired optimization algorithms. IEEE Access, 12, 23578–23594 (2024).

Castellanos, J., Uribe, C. A. & Diego Patino. Carlos Adrián Correa-Flórez, Alejandro Garcés, Gabriel Ordóñez-Plata, and. An energy management system model with power quality constraints for unbalanced multi-microgrids interacting in a local energy market. Applied Energy, vol. 343, 121149. (2023).

Karimi, H., Bahmani, R., Jadid, S. & Makui, A. Dynamic transactive energy in multi-microgrid systems considering independence performance index: A multi-objective optimization framework. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 126, 106563 (2021).

Bahramara, S., Parsa Moghaddam, M. & Haghifam, M. R. A bi-level optimization model for operation of distribution networks with micro-grids. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 82, 169–178 (2016).

Jiang, W. et al. A multiagent-based hierarchical energy management strategy for maximization of renewable energy consumption in interconnected multi-microgrids. IEEE Access. 7, 169931–169945 (2019).

Zhang, Z. et al. Optimization strategy for power sharing and low-carbon operation of multi-microgrid IES based on asymmetric Nash bargaining. Energy Strategy Reviews. 44, 100981 (2022).

Javadi, M., Sadegh, A. E., Nezhad, A. R., Jordehi, M. & Gough, S. F. Santos, and João PS Catalão. Transactive energy framework in multi-carrier energy hubs: A fully decentralized model. Energy, vol. 238, 121717. (2022).

Bidgoli, M. et al. Brent. Multi-criteria dispatch optimization of a community energy network with desalination: Insights for trading off cost and security of supply. Heliyon, vol. 9, no. 10, (2023).

Yu, W. A. N. G., Ke, L. I., Shuzhen, L. I. & Xin, M. A. A. N. G. Chenghui. A bi-level scheduling strategy for integrated energy systems considering integrated demand response and energy storage co-optimization. J. Energy Storage. 66, 107508 (2023).

Fan, W. et al. A Bi-level optimization model of integrated energy system considering wind power uncertainty. Renew. Energy. 202, 973–991 (2023).

Naebi, A., SeyedShenava, S. J., Contreras, J., Ruiz, C. & Adel Akbarimajd. EPEC approach for finding optimal day-ahead bidding strategy equilibria of multi-microgrids in active distribution networks. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 117, 105702 (2020).

Chen, C., Zhang, Y. & Zhihua Ge, and Study of combined heat and power plant integration with thermal energy storage for operational flexibility. Appl. Therm. Eng. 219, 119537 (2023).

Anuradha, K. B. J., José, Iria & Chathurika, P. Mediwaththe. A multi-objective stochastic optimization framework for government-run community energy storage systems auctions. J. Energy Storage. 132, 117614 (2025).

Büngeler, J., Cattaneo, E., Riegel, B. & Dirk Uwe, S. Advantages in energy efficiency of flooded lead-acid batteries when using partial state of charge operation. J. Power Sources. 375, 53–58 (2018).

Mukherjee, U. et al. Techno-economic, environmental, and safety assessment of hydrogen powered community microgrids; case study in Canada. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 42 (20), 14333–14349 (2017).

Karimi, H. and Shahram Jadid. Optimal energy management for multi-microgrid considering demand response programs: A stochastic multi-objective framework. Energy, vol. 195, 116992. (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hamid Karimi wrote the main manuscript text.Hamid Karimi prepared all the figures and Tables.Hamid Karimi reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Karimi, H. Sustainable operation of multi-energy systems under cooperative and non-cooperative strategies. Sci Rep 16, 6177 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36536-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36536-9