Abstract

Regional climate variability across Türkiye poses significant engineering and design challenges in optimizing building energy performance. This study presents a comprehensive evaluation of the energy, exergy, economic, and environmental (4E) performance of next-generation porous clay bricks enhanced with pumice and vermiculite additives (thermal conductivity ranging from 0.439 to 0.816 W/mK), in comparison with standard bricks (k = 1.041 W/mK). The corresponding reference-wall U-value is U = 2.44 W/m2K, whereas the PV4 wall achieves U = 1.44 W/m2K, corresponding to an approximate 41% U-value reduction. A 235 m2 duplex residential model was simulated using EnergyPlus (v8.4) with an annual resolution (8,760 h) across six representative climate zones—Mersin, Denizli, Bursa, Ankara, Kastamonu, and Erzurum. Results indicate that the PV4 brick mixture, composed of 55% clay, 40% pumice, and 5% vermiculite, reduces total annual energy consumption by 9.78% in Mersin (cooling-dominated) to 12.92% in Erzurum (heating-dominated). Exergy losses were reduced by 10.04% in Mersin and 13.66% in Erzurum (PV4 vs. PV0). Furthermore, annual CO₂ emissions were reduced by 3.1 kg/m2 in Mersin and 4.7 kg/m2 in Erzurum, and the payback period improved to a range of 4.8 to 6.6 years. These findings highlight the significant potential of climate-adapted building envelope materials in enhancing the thermo-environmental and economic performance of Türkiye’s residential building stock.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In response to the rising global energy demand and the imperative to mitigate climate change, energy efficiency policies have gained strategic importance1,2. As buildings account for a substantial share of global energy consumption and carbon emissions, achieving “net-zero” targets in the built environment represents not only a major challenge but also a significant opportunity3. Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems constitute the largest portion of energy use in buildings, and their performance is directly influenced by the thermal characteristics of the building envelope4,5. Accordingly, the development of passive energy-saving strategies and envelope optimization plays a pivotal role in sustainable building design6. In parallel, simulation-based building energy modeling has been widely used to quantify how envelope configurations and operational assumptions affect heating and cooling demand, providing a consistent basis for comparative performance assessment at the building scale7,8.

In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to sustainable composite materials and bio-based alternatives such as hempcrete, developed to enhance the thermal performance of building envelopes9,10. In particular, the use of biomass-based additives, industrial by-products, and construction and demolition waste has gained traction to improve the thermal, physical, and mechanical properties of fired clay bricks11,12,13. Integrating porous aggregates such as pumice, perlite, and expanded clay into brick matrices has been shown to significantly reduce thermal conductivity, thereby enhancing energy efficiency14,15. Similarly, Sutcu et al.13 observed thermal conductivity reductions ranging between 12% and 35% in clay-based masonry units incorporating lightweight or industrial waste additives, while compressive strength values remained above the minimum requirements for non-load-bearing masonry applications, highlighting the thermal–mechanical trade-off in porous masonry materials. For example, Gencel14 reported that the addition of pumice to fired clay bricks reduced thermal conductivity to below 0.65 W/mK, corresponding to a reduction of more than 30% compared to conventional bricks, primarily due to increased porosity and reduced bulk density.

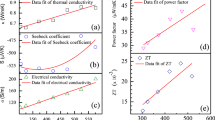

Studies investigating the thermo-physical and mechanical properties of energy-efficient clay bricks have reported that next-generation composites incorporating pumice and vermiculite can considerably lower both thermal conductivity and density compared to standard bricks16. Moreover, modeling efforts on thermal conductivity and thermo-economic assessments of lightweight concretes have demonstrated the direct impact of material development on building energy performance17,18,19. Beyond laboratory-scale characterization, building-scale evaluations in Türkiye have shown that the magnitude of heating demand is strongly climate-dependent: Akan et al.17 reported annual heating energy requirements per unit area spanning 11,213–965,715 kJ/m2-year across Turkish climate zones, depending on material and climatic boundary conditions.

However, the actual performance of a building material is not limited to its laboratory-measured thermal conductivity (k); it varies significantly depending on the dynamic conditions of the climate zone in which it is applied20. Climate change projections and energy consumption analyses across different climatic regions have shown that the accuracy of building energy simulations largely depends on the sensitivity of envelope modeling parameters21,22,23. From tropical to continental climates, research has highlighted the inadequacy of generic material selections and emphasized the need for climate-specific optimization of the building envelope24. This climate sensitivity is particularly relevant for porous masonry materials, whose benefits may manifest differently under heating- versus cooling-dominated conditions.

In Türkiye, nationwide and region-based analyses have shown that optimum insulation thickness and envelope decisions vary substantially by location, leading to better thermal and economic outcomes when localized approaches are adopted25. Regional applications of the degree-day method and location-specific wall performance assessments further support this climate-sensitive perspective26,27, while related energy-efficiency technologies have also been evaluated within the broader context of reducing building energy demand28. Recent investigations using updated degree-day data for all provincial centers have reinforced the importance of climate-adapted strategies, first by reporting province-level optimum insulation thicknesses29, then by explicitly incorporating both heating and cooling degree days into wall optimization30, and finally by extending the approach to other envelope applications such as cold storage walls31. Kurekci30 quantified that envelope material selection alone can result in reductions of approximately 10–20 kWh/m2-year in total building energy consumption, depending on local heating and cooling degree-day conditions. At the building-block scale, thermal conductivity has been reported to vary systematically with pumice density and pore structure, with values ranging from 0.135 to 0.197 W/mK as dry unit weight increases from approximately 1.2 to 1.8 g/cm³, underscoring the governing role of pore volume in heat transfer32.

Furthermore, evaluating building sustainability based solely on energy analysis is now seen as insufficient. Exergy analysis applied to building performance has been demonstrated as a viable assessment approach at the building scale33. Building-level thermodynamic applications further show that exergy, grounded in the second law of thermodynamics, can capture not only the magnitude but also the quality and location of energy losses34. In the envelope context, an exergy-based perspective has been used to compare insulating materials and quantify envelope-related performance differences35. Exergetic life-cycle formulations have also been employed to determine optimum insulation thickness for building walls36. Complementary building applications of thermal exergy analysis reinforce the usefulness of exergy metrics for diagnosing losses beyond what energy-only indicators reveal37. More recent comparative studies likewise highlight that insulation optimization can yield meaningful exergy savings under different climatic conditions38. Methodological work based on degree-days additionally supports practical exergy analysis of buildings using climate-representative indicators39.

Sustainability, however, must also account for economic viability and environmental impact. From an operational-emissions perspective, modeling studies have linked optimum insulation thickness decisions to reductions in annual CO₂ emissions for residential buildings40. At earlier life-cycle stages, construction-phase greenhouse gas emissions have been quantified as a non-negligible contributor to total impacts41. In parallel, embodied GHG emissions have been emphasized as a “hidden” challenge that can undermine climate-mitigation efforts if ignored42. To address economic feasibility in a consistent manner, life cycle cost analysis (LCCA) has been widely used to evaluate long-term cost implications of construction and retrofit measures43. Accordingly, integrated optimization studies have combined environmental indicators with LCC considerations for determining optimum insulation thickness44. Recent multi-objective 4E frameworks further illustrate how energy, exergy, economy, and environmental objectives can be balanced simultaneously within unified optimization formulations7,8. Consistent with this direction, 4E-based insulation optimization has been explicitly proposed for building walls and roofs to support robust envelope design decisions45,46. In this context, Akan and Akan40 demonstrated that applying optimum insulation thicknesses in heating-dominated residential buildings can reduce operational CO₂ emissions by up to approximately 76% during the heating season compared to uninsulated cases. While these advanced studies provide rigorous mathematical optimization for conventional envelope materials, there remains a specific need to validate these frameworks using experimentally characterized, non-conventional masonry units like porous clay bricks.

Despite these advances, a specific gap remains. Existing studies often focus either on (i) material-scale thermal characterization of porous bricks without climate-specific whole-building validation, or (ii) building-scale multi-criteria performance evaluations that rely on generic/assumed masonry properties and do not employ experimentally validated porous fired-clay brick inputs across multiple national climate zones. Accordingly, this study aims to comprehensively evaluate the 4E performance of wall configurations incorporating porous clay brick types enhanced with pumice and vermiculite—materials experimentally developed and characterized by Koçyiğit16—across six cities representing Türkiye’s major climate zones. By coupling laboratory-derived material properties with full-year dynamic EnergyPlus simulations under consistent boundary conditions and current degree-day-based climatic data, the study quantifies not only energy savings but also exergy losses, life-cycle cost outcomes, and carbon footprint implications, offering a systematic and transferable framework for climate-adaptive envelope material assessment.

Materials and methods

This section describes the simulation framework and input data used to assess the 4E (energy, exergy, economic, and environmental) performance of porous pumice–vermiculite fired-clay brick types (PV0–PV4) at the building scale. Five wall configurations were defined by applying different brick types to the same wall assembly and building model, while keeping all remaining envelope layers and operational settings identical. The building was simulated in six representative Turkish climate zones to enable climate-specific comparison under consistent boundary conditions using EnergyPlus v8.4. This section summarizes the building model, envelope, and material inputs, climatic data, simulation setup, and the analytical procedures applied in the study.

Simulation-based energy performance assessment inputs

A representative two-storey duplex model (235 m2 area, 2.7 m storey height) was developed using SketchUp Pro and integrated into EnergyPlus V8.4 via OpenStudio (Fig. 1). The building envelope features a slab-on-grade foundation, an insulated sloped roof, and a 20% window-to-wall ratio utilizing low-emissivity, argon-filled double glazing. The building orientation follows the cardinal directions with a south-facing reference. Thermal zoning was defined on a floor basis to support consistent evaluation of thermal comfort and heating/cooling energy demand.

The simulations evaluated five clay brick types (PV0–PV4), where PV0 represents a conventional clay brick and PV1–PV4 include varying proportions of pumice and expanded vermiculite. These porous bricks were experimentally developed and characterized by Koçyiğit (2022) in accordance with TS EN 771-1, and exhibit 45–53% porosity. These porous clay bricks are designed for non-load-bearing (infill) wall applications, and are not intended for structural or load-bearing use. The reported thermophysical properties include bulk density (ρ, 1310.86–1789.64 kg/m3), apparent density (ρapp, 2119.22–2519.07 kg/m3), thermal conductivity (k, 0.439–0.816 W/m K), and specific heat capacity (cp., 840–872 J/kg K)16. Beyond thermal efficiency, they meet structural requirements with compressive strengths of 7.5–9.2 MPa and fire resistance exceeding 60 min. The values obtained in the study were determined by experimental measurement and presented in the literature. The values of the newly developed clay bricks are listed in Table 1. From Table 1, bulk density (ρ), specific heat capacity (cp.), and thermal conductivity (k) values were used directly in EnergyPlus simulations16.

The external wall assembly consists of interior plaster, a brick core (PV0-PV4), and exterior plaster. The overall thermal transmittance (U-value) was derived from layer-specific properties by computing the total thermal resistance (Rtotal) of the assembly. For the reference wall (PV0), Rtotal= 0.4095 m2K/W. The internal (Ri) and external (Ro) surface film resistance values were adopted from the established literature25,31, as detailed in Table 2. A simplified non-insulated wall configuration, composed of 2 mm interior plaster, 190 mm porous clay brick, and 3 mm exterior plaster, was deliberately adopted in all simulations. This decision allows for isolating the intrinsic thermal performance of different brick types while maintaining consistent boundary conditions. Such envelope-focused modeling approaches are widely accepted in comparative building material research4,20,24, particularly when the objective is to identify material-driven energy performance trends rather than regulatory compliance. To ensure a robust comparative analysis, this wall assembly methodology was applied consistently across all wall models, incorporating different porous clay bricks (PV0–PV4).

To represent Turkey’s broad climatic diversity, six representative cities were selected based on the updated TS 825 (2024) thermal insulation standard, which categorizes the country into distinct zones using degree-day indicators. Specifically, Heating Degree-Days (HDD) and Cooling Degree-Days (CDD)—indices that quantify the intensity and duration of outdoor temperatures requiring space heating and cooling, respectively—were used as the primary criteria for site selection. The six selected cities were chosen to represent the full range of climatic conditions defined by the Turkish thermal insulation standard TS 825 (2024), rather than to capture local microclimatic variability within each region. This standard-based selection enables a nationally representative comparison of building envelope performance across heating-dominated, cooling-dominated, and mixed climate regimes in Türkiye47. The selected cities (Mersin, Denizli, Bursa, Ankara, Kastamonu, and Erzurum) represent each of the major climatic zones, ranging from the cooling-dominated 1st zone to the extreme heating-dominated 6th zone, thereby ensuring a comprehensive performance evaluation of the wall configurations under various thermal stresses. The geographic coordinates and specific degree-day data for these representative locations are detailed in Table 3.

The simulations were carried out using EnergyPlus v8.4 (U.S. Department of Energy48,49,50 with the Ideal Loads Air System model, modeling each scenario at an hourly resolution over the course of 8760 h annually. To align with ASHRAE standards51, the indoor temperature was maintained at 22 °C. All modes of energy transfer—conduction, radiation, ventilation, solar gains, internal gains, and infiltration—were dynamically analyzed. Utilizing EnergyPlus’s heat-mass balance framework, comprehensive energy balance calculations were performed at 15-minute intervals. This study assessed energy and exergy performance in 30 distinct simulation scenarios, which included six cities and five different types of bricks. This modeling approach not only uncovers performance variations arising from clay brick unit properties but also emphasizes the influence of climatic variability on building performance. Consequently, it provides a scientific foundation for envelope materials in Türkiye’s building stock in a climate-adapted manner. The schematic representation of the simulation process is depicted in Fig. 248,50.

The specific simulation parameters and modeling assumptions used in the study are summarized in Table 4, following ASHRAE 140 reporting conventions. Simulation inputs and boundary conditions were documented in line with the intent of ASHRAE Standard 140 (BESTEST), which provides a standardized comparative verification framework for building energy simulation tools. Rather than calibrating a specific real building, the BESTEST philosophy emphasizes clearly defined and consistently applied input assumptions so that the model’s response to controlled changes in envelope/system parameters can be interpreted reliably. Accordingly, this alignment improves the transparency, traceability, and reproducibility of the relative comparisons among the investigated wall configurations.

The methodology adopted in this study consists of four interconnected stages: (i) experimental characterization of clay brick materials at the unit scale, (ii) EnergyPlus-based whole-building simulation under six climatic scenarios, (iii) an integrated 4E performance evaluation (energy, exergy, economic, and environmental), and (iv) robustness analysis through sensitivity and comparative assessments. A summary of the workflow, inputs, and outputs of each phase is illustrated in Fig. 3, which provides a clear roadmap of the research process.

4E (energy, exergy, economic and environmental) performance analysis method

The annual heating and cooling energy demands attributable to the building envelope were evaluated through dynamic simulations conducted using EnergyPlus outputs. These evaluations incorporated the thermal performance characteristics of individual building components. The analytical framework for this energy assessment is grounded in fundamental heat transfer principles, wherein the thermal behavior of the building envelope is defined in accordance with the methodology outlined in53. Specifically, the core of the analysis is based on Fourier’s Law of heat conduction, as represented in Eq. (1).

In this equation, Q represents the total heat transfer (J) occurring over a given time interval (t). U denotes the overall heat transfer coefficient of the building component (W/m2K), A is the heat transfer surface area (m2), and ΔT refers to the temperature difference (K) between the indoor and outdoor environments. The thermal transmittance coefficient (U) can be calculated using Eq. (2) based on the total thermal resistance (Rtotal), taking into account the multi-layered structure of the building component31.

The total thermal resistance Rtotal is calculated as the sum of the individual thermal resistances Rin of each building layer. The thermal resistance of each layer depends on the ratio between the material thickness (Li) and its thermal conductivity (ki) as expressed in Eq. (3)31.

Accordingly, the total thermal resistance of all layers of the wall model used in the study is expressed by Eq. (4)30.

Here, Ri and R0 denote the internal and external surface film resistances, respectively. In the simulation model, the annual energy requirement was calculated using hourly time steps and is defined by Eq. (5)48.

In Eq. (5), Eyear denotes the annual energy requirement (J), and the constant 3600 converts the hourly time step to seconds. Each \(\:{{\Delta\:}T}_{j}\), represents the indoor–outdoor temperature difference for an hour. Exergy (Ex) analysis was used to evaluate the thermodynamic quality of envelope-related heat transfer. In this study, the heat transfer rate/quantity Q required for the exergy calculations was not assumed; it was directly extracted from the dynamic EnergyPlus simulations. The second-law relation given in Eq. (6) was then employed to compute the exergy loss associated with heat transfer54.

Here, Exloss represents the exergy loss due to heat transfer (J); T0 (K) is the ambient (outdoor) reference temperature; T (K) is the indoor air temperature; and Q (J) is the conductive heat transfer through the wall. Monthly conductive heat transfer quantities Q were extracted for each wall configuration, thereby reflecting transient effects (e.g., thermal mass, solar gains, and time-varying outdoor conditions). These monthly Q values were combined with the corresponding monthly average outdoor temperatures to define T0 and to compute monthly exergy losses using Eq. (6). The indoor temperature T was taken as the constant setpoint of 22 °C (295.15 K) throughout the year. The annual exergy loss was calculated based on seasonal heat transfer values obtained through dynamic simulation (EnergyPlus). In this context, the total annual exergy loss is defined by Eq. (7)34.

Here, the terms Exloss, h, and Exloss, c denote the seasonal exergy losses associated with heating and cooling, respectively34. The total annual exergy loss was computed as the sum of the seasonal contributions derived from the monthly EnergyPlus heat-transfer outputs. This procedure enables a climate-responsive, simulation-based exergy assessment of the wall configurations and supports consistent comparison across different climatic contexts.

As part of the economic analysis of the study, the Life Cycle Cost (LCC) Analysis methodology was employed to assess the long-term feasibility of the innovative brick scenarios (PV1–PV4) in comparison to the reference brick (PV0). To account for the time value of money, the Net Present Value (NPV) was determined over a 10-year lifetime (N). The actual interest rate (r), representing the economic balance between the nominal interest rate (i) and the inflation rate (g), was calculated using Eq. (8)46.

Subsequently, the Present Worth Factor (PWF) was determined using Eq. (9) to represent the cumulative value of annual savings46.

The total life-cycle cost (CLCC) was then calculated by combining the initial investment cost and the discounted operational energy costs as defined in Eq. (10)25.

The specific economic parameters and investment costs used in these calculations are summarized in Table 5.

Ctotal indicates the annual energy cost for heating and cooling, which was calculated using the energy requirement (Q), fuel unit cost (Cfuel), and system efficiency as shown in Eqs. (11) and (12)30:

Here, Qheating indicates the heating energy requirement obtained from the simulation, Qcooling indicates the cooling energy requirement obtained from the simulation, and Cfuel and Ce indicate the unit cost of natural gas and electricity, respectively. The specific values employed in this study for energy sources are enumerated in Table 6.

In this study, the economic performance was assessed using life cycle cost analysis (LCCA), and environmental sustainability was evaluated via total carbon emissions (CO2,total) in accordance with EN 1597855,56. The analysis follows EN 15978 and quantifies the total carbon emissions as the sum of embodied carbon emitted during material production and installation and operational carbon emitted during the building’s use phase. Accordingly, the total carbon impact was calculated using Eq. (13) as46:

Here, CO2,embodied represents the CO₂ emissions associated with the production, transport, and application of the building material, whereas CO2,operational represents the CO₂ emissions arising from the energy consumed to meet the building’s heating and cooling demands over its service life. The embodied carbon component was calculated using Eq. (14) by considering the material bulk density (ρ), clay brick thickness (L), and the emission factors for raw material extraction/supply (CO2,A1), transportation (CO2,A2), and manufacturing (CO2,A3) for each clay brick type:

The Inventory of Carbon & Energy (ICE) database was used as a reference for the carbon emission factors of raw materials and production processes57. The embodied carbon inventory calculated for the reference (PV0) and additive (PV1-PV4) clay bricks is reported in Table 7. As shown in Table 7, raw material and transportation emissions increased with higher additive content, whereas the A3 term was kept constant because the firing process was assumed identical for all samples.

In this study, embodied carbon (EC) values were calculated in kgCO₂e/kg-brick unit. This approach is compatible with the ICE database, which assesses the carbon impact of Raw materials used in Building material production, transport distances, and production processes on a mass basis57. Regarding the A1 (raw material) stage, emission factors were specified as 0.005 kgCO2e/kg for clay, 0.006 kgCO2e/kg for pumice, and 0.801 kgCO2e/kg for expanded vermiculite based on the specific mass fractions of each mixture. The A2 (transportation) stage was modeled based on a heavy-duty Euro 5 engine truck (> 20 tons) with an emission factor of 0.107 kgCO2e/tkm, assuming transport distances of 20 Km for clay and 150 Km for additives. For the A3 (manufacturing) stage, the energy intensity of the industrial firing process was kept constant at 0.1403 kgCO2e/kg for all samples to ensure a controlled comparative analysis57,58. If these values are to be compared based on surface area (m2), the approximate carbon density can be calculated using the bulk density (ρ) and wall thickness (L) of the relevant brick type as shown in Eq. (14). This study assumes a standard wall thickness (L) of 0.19 m for a 1 m2 wall, with corresponding material consumptions of 366.81 kg, 340.03 kg, 307.75 kg, 275.47 kg, and 249.06 kg for PV0, PV1, PV2, PV3, and PV4 bricks, respectively. However, as the primary objective of the analyses in this study is to evaluate relative performance differences, the unit kgCO₂/kg has been preferred for comparative analyses. This method allows for transparent and traceable comparison of the environmental impacts of different material compositions. Operational carbon refers to emissions generated by the fuel consumed to Meet the heating and cooling needs of the Building throughout its service life. Operational carbon emissions were determined using Eq. (15)59,60.

Result and discussion

This section presents the results obtained for the next-generation porous clay bricks (PV0–PV4) incorporating pumice and vermiculite additives in terms of annual energy consumption, exergy loss, environmental impact, and economic performance across different climate zones, and discusses them in comparison with the existing literature. To provide an at-a-glance comparison across all climates and brick configurations, Table 8 consolidates the key annual 4E indicators (energy, exergy, economic, and environmental analysis results) for PV0–PV4 in the six representative cities. The following sub-sections discuss these outcomes in detail.

Energy and exergy analysis

The results obtained from EnergyPlus-based simulations are presented in Fig. 4, which compares the effects of five different brick configurations (PV0–PV4) on annual heating and cooling energy consumption in six cities representing different climate zones.

In the analyses of the heating loads shown in Fig. 4a, it is evident that the wall configuration using PV4 provides savings of up to 10–14%, particularly in cold climates (such as Erzurum and Kastamonu). This result demonstrates that PV4 limits heat loss due to its low thermal conductivity. In hot regions (e.g., Mersin), however, the effect of material-related improvements is limited due to the lower absolute heating load. The cooling load analyses presented in Fig. 4b show that the Wall configuration using PV4 provides savings of 6–11% in hot climates (such as Mersin and Denizli). This is related to the building envelope’s reduced heat-gain effect.

In contrast, in cold regions, cooling loads are low, so the difference remains below 2%. Overall, improvement rates increase in parallel with the additive content across all configurations. Figure 5 presents a comparative analysis of the effect of different brick configurations on total annual energy requirements (heating + cooling) for six different climate zones in Türkiye.

As illustrated in Fig. 5a, the PV4 configuration achieved the highest energy efficiency across all climate zones, yielding total demand reductions of 12.92% in heating-dominant Erzurum and 10.81% in cooling-dominant Mersin relative to the reference case (PV0). Decomposing these loads (Fig. 5b) reveals absolute savings reaching 21 kWh/m2-year for heating and 17 kWh/m2-year for cooling, confirming the material’s efficacy in mitigating both thermal losses and gains. These results underscore the critical role of low thermal conductivity in extreme climatic conditions, consistent with prior research attributing enhanced thermal performance to porosity and additive integration in porous masonry systems11,13,14.

When Fig. 6 was examined, the reduction in annual exergy losses—reaching up to 13.66% with the PV4 wall configuration—is fundamentally attributed to the mitigation of internal and external thermodynamic irreversibilities. Specifically, the lower thermal conductivity of the innovative porous bricks reduces the magnitude of heat flux through the wall assembly, which consequently decreases the temperature gradient (ΔT) between the indoor and outdoor environments. From the perspective of the second law of thermodynamics, a smaller ΔT during heat transfer results in lower entropy generation and, thus, reduced exergy destruction. Furthermore, the optimized thermal mass and specific heat capacity (cp) of the PV4 porous clay bricks (872 J/kgK) provide an enhanced thermal damping effect. This allows the building envelope to stabilize internal temperature fluctuations more effectively against transient climatic loads, minimizing the high-quality energy required to maintain thermal equilibrium.

In cold climates such as Erzurum, the wall configuration with PV4 reduced annual total exergy loss to 13.7 kWh/m2-year, representing a 14% reduction compared to the reference case (PV0), while improvements reached 12% in temperate regions like Ankara. Even in hot climates (Mersin and Denizli), PV4 maintained a 10% exergy advantage. These findings corroborate the positive impact of thermal mass on exergy efficiency34 and align with the reported distinctions between energy and exergy performance in buildings37. Furthermore, the observed regional variations validate the necessity of climate-specific building envelope analysis for robust performance assessment39.

The findings of this study, particularly the thermodynamic improvements achieved with PV4 across all zones, align with the global multi-criteria envelope optimization trends. Consistent with the findings of Zhou et al.7,61 in different climatic contexts, our results confirm that increasing the thermal resistance of the building skin leads to non-linear improvements across all 4E metrics. However, our analysis specifically highlights that for porous clay bricks, the magnitude of these improvements is highly dependent on the local HDD profile, showing the highest exergy resilience in extreme climates like Erzurum.

Economic and environmental assessment

Beyond energy conservation, economic feasibility is a decisive factor in material selection. Accordingly, this study evaluates the cost-effectiveness of the proposed brick configurations by quantifying annual energy savings ($/m2-year) and payback periods relative to the reference case (PV0), based on dynamic simulation outputs. Figure 7 illustrates the variations in annual total energy costs across the six climate zones.

When examining Fig. 7, the building scenarios modelled with PV4-type bricks show lower total energy costs in all climate zones. Particularly in regions with high annual heating requirements, such as Erzurum, the PV4 clay brick achieved an annual saving of approximately $0.65/m2-year. Similarly, in cold climate zones such as Kastamonu and Ankara, annual savings reached the range of $0.55–0.6/m2-year. In hot regions (e.g., Mersin), although energy savings were relatively low, a cost advantage was achieved due to the reduced cooling loads. These results demonstrate that bricks with lower thermal conductivity and higher specific heat capacity also offer economic advantages. The payback periods calculated for different brick configurations (PV1–PV4) are presented for comparison across the six climate zones in Fig. 8.

As illustrated in Fig. 8, the superior thermal performance of PV4 translates directly into economic viability. In heating-dominated regions such as Erzurum, PV4 achieves a payback period (PBP) of less than five years, whereas lower-performing alternatives (PV1, PV2) prolong this period to 7–9 years. This trend is consistent across all climate zones and corroborates studies in Turkey, which estimate optimal insulation PBPs between 5.38 and 7.47 years17,29,30,31. In order to provide a comprehensive robustness check as per EN 15459, a sensitivity analysis was performed for all developed brick types (PV1–PV4) across all climatic zones. The analysis evaluated the impact of annual energy price escalation rates of 5% and 10% on the Net Present Value (NPV) of energy savings over a 10-year lifespan. As detailed in Table 9, even under the most conservative scenarios, all innovative bricks maintain their economic superiority over the reference case (PV0). For the PV4 configuration, a 10% annual increase in energy prices results in nearly an 80% increase in total savings, reaching up to $9.07/m2 in Mersin and $8.75/m2 in Erzurum. These findings demonstrate that the proposed lightweight bricks act as a hedge against energy market volatility, providing greater economic security as energy costs rise.

Regarding environmental performance, Fig. 9 illustrates the annual total CO2 emissions, encompassing both embodied and operational carbon loads, normalized per square meter of the wall system. The embodied emissions (gray bars) contribute approximately 55 kgCO2/m2-year across all configurations, representing the baseline environmental impact of material production. When considering the total life-cycle impact, the PV4 configuration achieves the highest environmental benefit, particularly in heating-dominated regions like Erzurum and Ankara, where operational carbon reductions are most significant. In Erzurum, the net emission savings for PV4 reach nearly 4.7 kgCO2/m2-year compared to the reference clay brick case (PV0). Even in cooling-dominated Mersin, the innovative brick configurations demonstrate a clear reduction in total carbon emissions, indicating that the increased embodied carbon associated with the modified bricks is effectively offset by substantial operational energy savings. These findings align with life cycle assessments linking insulation optimization to significant carbon mitigation44 and support the emphasis on integrating embodied carbon into material selection for holistic building envelope design46.

The performance advantage of the proposed porous clay bricks becomes more evident when compared with common masonry alternatives such as Autoclaved Aerated Concrete (AAC) and conventional concrete blocks. Previous studies have reported that while AAC provides low thermal conductivity, its high hygroscopicity often leads to an in-situ thermal performance degradation of up to 15–20% under humid conditions. In contrast, the porous clay matrix utilized in this study offers better moisture buffering and structural integrity. Furthermore, comparative life-cycle assessments indicate that fired clay bricks with pumice additives can achieve a 10–12% lower carbon footprint per unit of R-value compared to lightweight concrete blocks, primarily due to the lower cement-related embodied emissions. Quantitatively, while standard concrete blocks exhibit thermal conductivities above 1.0 W/mK, the PV4 configuration reduces this value to 0.439 W/mK, providing a 56% improvement in the building envelope’s thermal resistance without the need for additional synthetic insulation layers.

A systematic sensitivity screening was conducted to evaluate the stability of the 4E (Energy, Exergy, Economy, Environment) results and to address potential input uncertainties across the six climatic zones. As summarized in Table 10, the analysis focused on two critical operational and material variables associated with the investigated wall models: (i) thermal conductivity (k) variations of ± 10\% to account for moisture-related variability within the porous clay brick units, and (ii) infiltration rate fluctuations of ± 20% reflecting uncertainties in construction quality and airtightness of the overall wall assembly. This screening-level sensitivity approach is consistent with common practice in simulation-based building performance and energy-management research, where a limited set of influential inputs is perturbed within plausible ranges to test the robustness of comparative conclusions. Although61 is framed in the context of energy flexibility and control, the underlying principle—evaluating result stability against plausible input perturbations—is directly transferable to building energy simulation studies. All sensitivity indices are reported as the magnitude of the relative deviation from the respective baseline case for each wall type (|Δ%|), calculated as |Δ%|=100|(Xperturbedcase–Xbasecase)/Xbasecase|. While the results in Table 10 are reported as absolute magnitudes, the directionality follows consistent physical logic; increases in k and infiltration generally increase Eyear, Exloss, and CO2 while reducing NPV. This assessment addresses input uncertainty at a level consistent with typical building simulation studies and is sufficient to demonstrate the robustness of the identified comparative trends among the wall models utilizing different innovative clay bricks.

The numerical results in Table 10 demonstrate that the 4E performance of the wall configurations incorporating different porous clay brick types is highly susceptible to climatic boundary conditions and material properties. A primary observation is the climatic divergence of sensitivity indices, specifically variations in clay brick thermal conductivity (k) and infiltration rates, which exert their maximum impact in cold climates. For the baseline wall type (PV0) and the optimized configuration (PV4), Erzurum exhibits the highest energy demand deviation, reaching magnitudes of 5.0% and 3.7%, respectively. This confirms that conduction through the building envelope and air leakage are the dominant heat loss mechanisms in heating-dominated regions. Furthermore, the wall configuration with innovative PV4 consistently shows the lowest sensitivity magnitudes (|Δ%|) across all six zones, indicating superior thermodynamic and economic resilience compared to the standard reference case with PV0. For instance, the NPV sensitivity to infiltration in Erzurum is reduced from 6.1% (PV0) to 5.1% (PV4), proving that the high-performance porous brick layers act as a “thermal buffer” that mitigates the risks associated with construction quality and material degradation.

It should be noted that the performance of porous materials is inherently linked to their moisture-dependent thermal conductivity, a factor often highlighted as a critical uncertainty in real-world applications7. In this study, we addressed this potential degradation by conducting a sensitivity analysis (k ± 10%), which demonstrated that even under potential moisture-induced conductivity increases, the PV4 configuration maintains its comparative advantage over standard clay bricks. While all values are reported as absolute magnitudes, the physical trend remains consistent: increases in k and infiltration exacerbate exergy losses (Exloss) and CO2 emissions while penalizing the NPV. This screening confirms that the comparative advantages of the proposed porous brick wall designs are robust even under conservative ± 10% to ± 20% parameter perturbations.

Conclusion

In this study, six cities representing different climate zones in Turkey were analyzed. The research focused on standard bricks containing 100% clay (referred to as PV0) and the performance of the novel developed porous clay bricks made from 55% clay, 40% pumice, and 5% vermiculite (PV1-PV4 series). The evaluation considered the 4E dimensions: Energy, Exergy, Economic, and Environmental impacts, using comprehensive building energy simulations. The main findings can be summarized as follows:

-

Buildings using wall configurations with PV4 bricks experienced a decrease in total annual energy consumption by 9–13% compared to the PV0 reference bricks.

-

The use of PV4 bricks resulted in an average reduction in annual exergy loss of 10–14% across all regions.

-

The annual energy cost savings for buildings using PV4 bricks ranged from $0.50 to $0.70 per square meter, with a payback period (PBP) estimated to be between 4 and 6 years.

-

Additionally, PV4 bricks contributed to a reduction in annual CO₂ emissions by 3–5 kgCO2/m2.

The analysis demonstrates that climate-specific envelope optimization is vital for multidimensional sustainability, underscoring that laboratory-determined thermal conductivity is insufficient for accurate evaluation without dynamic simulations. Consequently, PV4 porous bricks emerge as a technically and economically superior alternative. Based on these insights, the following recommendations and final assessments are proposed:

-

Policy and fiscal recommendations: Material selection strategies must move beyond generic approaches to prioritize climate-specific adaptability. Governments and policymakers should implement fiscal mechanisms, such as tax reductions or energy efficiency certification schemes, to promote the commercialization of locally sourced, sustainable materials like pumice-vermiculite clay bricks.

-

Engineering and design: Integrating these material properties into Building Information Modelling (BIM) workflows at the early design stage offers significant advantages for architectural and engineering precision.

-

Study limitations: While providing robust comparative results, this study acknowledges certain real-world limitations. These include the long-term sensitivity of porous bricks to moisture content (which may alter thermal conductivity), potential surface aging/soiling effects on solar absorptance, and the impact of thermal bridging in practical construction quality. The simulated walls do not include external insulation. While this was a deliberate modeling choice to isolate material effects, the resulting energy and CO₂ savings represent upper-bound estimates and may not fully reflect code-compliant assemblies under TS 825. The HVAC system is modeled using the Ideal Loads Air System, which excludes equipment efficiencies and user behavior; thus, the results are for relative comparison only. Thermal bridging effects (e.g., from mortar joints or structural connections) were not explicitly modeled and could reduce real-world thermal performance.

-

Future work and circular economy: Future studies should extend this methodology to diverse building typologies and occupancy scenarios. Moreover, future research should focus on “Lifecycle Stage C” (end-of-life), investigating the potential for crushing and reusing pumice/vermiculite-enhanced bricks as aggregate in new construction materials to support circular economy goals.

In conclusion, this study validates PV4 porous clay bricks as a technically viable solution for enhancing both energy efficiency and environmental sustainability. Expanding such climate-responsive performance analyses is essential for establishing a resilient and energy-efficient national building stock in multi-climatic regions like Turkey.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

IEA. Energy Efficiency : Analysis and Outlooks to 2030. International Energy Agency. (2023). https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-efficiency-2023 (2023).

IPCC. Climate Change : Synthesis Report. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2023). https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/ (2023).

Ma, M. et al. Challenges and opportunities in the global net-zero Building sector. Cell. Rep. Sustain. 1, 100028 (2024).

Sadineni, S. B., Madala, S. & Boehm, R. F. Passive Building energy savings: A review of Building envelope components. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 15, 3617–3631 (2011).

Simpeh, E. K. et al. Improving energy efficiency of HVAC systems in buildings: a review of best practices. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 40, 165–182 (2022).

Ubarte, I. & Kaplinski, O. Review of the sustainable built environment in 1998–2015. Eng. Struct. Technol. 8, 41–51 (2016).

Zhou, Y. & Zheng, S. Machine-learning based hybrid demand-side controller for high-rise office buildings with high energy flexibilities. Appl. Energy. 262, 114416 (2020).

Zhou, Y. & Cao, S. Energy flexibility investigation of advanced grid-responsive energy control strategies with the static battery and electric vehicles: A case study of a high-rise office Building in Hong Kong. Energy Convers. Manag. 199, 111888 (2019).

Deshmukh, M. & Yadav, M. Optimizing thermal efficiency of Building envelopes with sustainable composite materials. Buildings 15, 230 (2025).

Steyn, K., de Villiers, W. & Babafemi, A. J. A comprehensive review of hempcrete as a sustainable Building material. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 10, 97 (2025).

Akpomie, K. G. et al. Effect of biomass-based additives on the thermal, physical, and mechanical properties of fired clay bricks: A review. Int. J. Thermophys. 46, 5 (2025).

Hu, K. et al. Eco-friendly construction: integrating demolition waste into concrete masonry blocks for sustainable development. Constr. Build. Mater. 460, 139797 (2025).

Sutcu, M. et al. Recycling of bottom ash and fly ash wastes in eco-friendly clay brick production. J. Clean. Prod. 233, 753–764 (2019).

Gencel, O. Characteristics of fired clay bricks with pumice additive. Energy Build. 102, 217–224 (2015).

Pérez-Urrestarazu, L. et al. Assessment of perlite, expanded clay and pumice as substrates for living walls. Sci. Hortic. 254, 48–54 (2019).

Koçyiğit, F. Thermo-physical and mechanical properties of clay bricks produced for energy saving. Int. J. Thermophys. 43, 18 (2022).

Akan, A. E., Ünal, F. & Koçyiğit, F. Investigation of energy saving potential in buildings using novel developed lightweight concrete. Int. J. Thermophys. 42, 4 (2021).

Koçyi̇ği̇t, F. & Ünal, F. Case study on thermo-economic and environmental performance of innovative lightweight concretes in buildings. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 75, 107079 (2025).

Koçyiğit, F., Ünal, F. & Koçyiğit, Ş. Experimental analysis and modeling of the thermal conductivities for a novel Building material providing environmental transformation. Energy Sources Part. A. 42, 3063–3079 (2020).

Dong, Y. et al. Wall insulation materials in different climate zones: A review on challenges and opportunities of available alternatives. Thermo 3, 38–65 (2023).

Campagna, L. M. & Fiorito, F. On the impact of climate change on Building energy consumptions: a meta-analysis. Energies 15, 354 (2022).

Congedo, P. M. et al. Worldwide dynamic predictive analysis of building performance under long-term climate change conditions. J. Build. Eng. 42, 103057 (2021).

Muhič, S. et al. Influence of building envelope modeling parameters on energy simulation results. Sustainability 17, 5276 (2025).

Jannat, N. et al. A comparative simulation study of the thermal performances of the Building envelope wall materials in the tropics. Sustainability 12, 4892 (2020).

Akan, A. E. Determination and modeling of optimum insulation thickness for thermal insulation of buildings in all City centers of Turkey. Int. J. Thermophys. 42, 49 (2021).

Bereketoğlu, S. Energy analysis of the provinces in the southeastern anatolia region: an evaluation using artificial and natural insulation materials with the degree-day method. Waprime 1, 26–44 (2024).

Ünal, F. Condensation analysis of the insulation of walls according to different locations in Mardin Province. Eur. J. Tech. 9, 253–262 (2019).

Yaman, K., Dölek, S. & Arslan, G. Performance analysis of a thermoelectric generator (TEG) for waste heat recovery. WAPRIME 2, 13–20 (2025).

Kürekci, N. et al. Türkiye’nin tüm Illeri için optimum yalıtım kalınlığı. Tesisat Mühendisliği. 131, 31–43 (2012).

Kurekci, N. A. Determination of optimum insulation thickness for Building walls by using heating and cooling degree-day values of all turkey’s provincial centers. Energy Build. 118, 197–213 (2016).

Kürekci, N. A. Optimum insulation thickness for cold storage walls: case study for Turkey. J. Therm. Eng. 6, 873–887 (2020).

Özün, S. Influences of physical properties of pumice on its dry unit volume weight and thermal conductivity. Süleyman Demirel UniversityJournal Nat. Appl. Sci. 23, 26–32 (2019).

Sartor, K. & Dewallef, P. Exergy analysis applied to performance of buildings in Europe. Energy Build. 148, 348–354 (2017).

Yucer, C. T. & Hepbasli, A. Thermodynamic analysis of a Building using exergy analysis method. Energy Build. 43, 536–542 (2011).

Anand, Y. et al. Building envelope performance with different insulating materials – An exergy approach. J. Therm. Eng. 1, 433–439 (2015).

Ashouri, M. et al. Optimum insulation thickness determination of a building wall using exergetic life cycle assessment. Appl. Therm. Eng. 106, 307–315 (2016).

Baldi, M. G. & Leoncini, L. Thermal exergy analysis of a building. Energy Proc. 62, 723–732 (2014).

Fohagui, F. C. V. et al. Optimum insulation thickness and exergy savings of Building walls in bamenda: A comparative analysis. Energy Storage Sav. 3, 60–70 (2024).

Martinaitis, V., Bieksa, D. & Miseviciute, V. Degree-days for the exergy analysis of buildings. Energy Build. 42, 1063–1069 (2010).

Akan, A. P. & Akan, A. E. Modeling of CO2 emissions via optimum insulation thickness of residential buildings. Clean. Technol. Environ. Policy. 24, 949–967 (2022).

Hong, J. et al. Greenhouse gas emissions during the construction phase of a building: A case study in China. J. Clean. Prod. 103, 249–259 (2015).

Röck, M. et al. Embodied GHG emissions of buildings–The hidden challenge for effective climate change mitigation. Appl. Energy. 258, 114107 (2020).

Altaf, M. et al. Life cycle cost analysis (LCCA) of construction projects: sustainability perspective. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 25, 12071–12118 (2023).

Özel, G. et al. Optimum insulation thickness determination using the environmental and life cycle cost analyses based entransy approach. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 11, 87–91 (2015).

Saadmohammadi, B. & Sajadi, B. 4E analysis and tri-objective optimization of a novel solar 4th cogeneration system for a smart residential Building in various climates of Iran. Energy Convers. Manag. 303, 118177 (2024).

Uçar, A. Optimization of insulation thickness of walls and roofs using energy, exergy, economic and environmental (4E) analyses. J. Mech. Eng. Sci 9959–9975 (2024).

TSE. TS 825 Thermal Insulation Requirements for Buildings (Turkish Standards Institution, 2024).

U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). EnergyPlus documentation. (2023). https://www.energy.gov/eere/buildings/articles/energyplus

U.S. Department of Energy. EnergyPlus Energy Simulation Software Engineering Reference. Washington, (2015).

EnergyPlus EnergyPlus Energy Simulation Software Engineering Reference (Department of Energy, Washington, USA,, 2015).

ASHRAE. Standard Method of Test for the Evaluation of Building Energy Analysis Computer Programs (ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 140–2017) (ASHRAE, 2017).

Crawley, D. B. et al. EnergyPlus: New, capable, and linked. J. Archit. Plann. Res. 21, 292–302 (2004).

Cengel, Y. A. & Ghajar, A. J. Heat and Mass Transfer Fundamentals & Applications 5th edn (McGraw-Hill Education, 2015).

Çengel, Y. A. & Boles, M. A. Thermodynamics: an Engineering Approach 8th edn (McGraw-Hill Education, 2015).

CEN. EN 15978: Sustainability of Construction works - Assessment of Environmental Performance of buildings—Calculation Method (European Committee for Standardization, 2011).

Biswas, W. K. Carbon footprint and embodied energy assessment of a civil works program in a residential estate in Western Australia. J. Clean. Prod. 80, 19–28 (2014).

Hammond, G. P. & Jones, C. I. Inventory of Carbon & Energy (ICE) (University of Bath, 2008).

International Organization for Standardization. Environmental management—Life cycle assessment—Requirements and guidelines (ISO Standard No. 14044:2006). (2006). https://www.iso.org/standard/38498.html

Dombaycı, Ö. A. The environmental impact of optimum insulation thickness for external walls of buildings. Build. Environ. 42, 3855–3859 (2007).

Bolattürk, A. Determination of optimum insulation thickness for Building walls with respect to various fuels and climate zones in Turkey. Appl. Therm. Eng. 26, 1301–1309 (2006).

Zhou, Y., Cao, S., Hensen, J. L. M. & Hasan, A. Heuristic battery-protective strategy for energy management of an interactive renewables–buildings–vehicles energy sharing network with high energy flexibility. Energy Convers. Manag. 214, 112891 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Assoc. Prof. Dr. F. Koçyiğit for providing the experimental data and technical specifications of the porous clay brick samples evaluated in this research.

Funding

There is no funding to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Ş.A. and F.Ü. andconceived the study and developed the methodology. Ş.K. provided the experimental data and thermophysical characterization of the porous clay brick samples. M.Ş.A. and F.Ü. performed the dynamic energy simulations using EnergyPlus software. M.Ş.A. , F.Ü. and N.İ.B. conducted the comprehensive 4E (Energy, Exergy, Economic, and Environmental) analyses and interpretation of the results. M.Ş.A. and F.Ü. wrote the main manuscript text. N.İ.B. and Ş.K. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Acar, M.Ş., Beyazit, N.İ., Ünal, F. et al. Comprehensive 4E performance assessment of novel porous clay bricks across new climate zones of Türkİye. Sci Rep 16, 6124 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37241-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37241-3