Abstract

Developing novel low-reflection structures, such as Oscillating Water Column (OWC) wave absorbers, provides a promising solution for enhancing harbor berthing safety. OWCs present the dual advantage of reducing wave reflections while simultaneously capturing wave energy. This study experimentally investigates the reflection characteristics, efficiency of wave energy extraction, and power dissipation behavior of OWC absorbers with different rear wall configurations. Furthermore, it investigates variations in rear wall geometry, incident wave height, and the well turbine located inside the air chamber, which converts wave power into pneumatic power. Controlled wave flume experiments at the University of Port Said were conducted on four models. Key performance parameters analyzed include the dissipation coefficient (Cd), energy coefficient (Ce), transmission coefficient (Ct), reflection coefficient (Cr), and pressure coefficient (Cp). The effects of different draughts, water depths, and air pressure fluctuations inside the pneumatic chambers were also examined. Results indicate that rear wall geometry significantly affects reflection and dissipation rates. Model-D achieved optimal performance at a water depth of 0.30 m with a front wall draught (d1) of 0.10 m, exhibiting low reflection (Cr = 0.139), high energy dissipation (Cd = 0.9), and a high wave energy conversion (Ce = 0.75; Cp = 0.85), making Model-D suitable for floating barriers in deep-water environments. Its superior wave energy dissipation enables effective operation under larger drafts and higher sea states.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

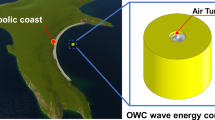

Wave energy is a rich and cost-effective resource with significant potential to enhance the global renewable energy mixture. Various Wave Energy Converters (WECs) have been developed to capture this energy by converting the mechanical motion of waves into electrical power. These devices are classified according to their geometry, mode of operation, and location relative to the shoreline, as onshore, nearshore, or offshore systems. In terms of working principles, WECs are divided into point absorbers, oscillating bodies, overtopping devices, or Oscillating Water Columns (OWCs). Such classifications determine their energy capture efficiency and suitability for different marine environments1,2,3. Among these devices, OWC has been recognized as one of the most practical and well-studied types of WEC due to its simple configuration and minimal number of moving parts. An OWC consists of a fixed or floating hollow chamber that traps a column of air above a water surface open to the sea below. The vertical motion of waves causes the trapped air to compress and decompress, forcing airflow through an air turbine connected to an electrical generator4. The OWC’s simplicity, strong structure, and low maintenance requirements make it particularly suitable for integration into coastal or breakwater structures. Breakwater Wave Energy Converters (BW-WECs) are associated with the protective function of floating breakwaters, also presenting energy generation capability. Such hybrid systems effectively utilize the motion of floating bodies to dissipate wave energy while generating electricity. The Water Column (OWC)-based BW-WECs are considered highly promising for coastal protection and renewable energy harvesting due to their dual functionality and economic feasibility.sxds

Recent research has focused on the development and optimization of hybrid floating energy systems. For example5, proposed a V-shaped floating platform that integrates a wave energy converter (WEC) with a wind turbine to optimize both wind and wave energy utilization. Many tools, such as FAST 6, FORTRAN6, and ANSYS-AQWA7, were used to develop an integrated numerical analysis structure for investigating the dynamic behavior of the system. The results showed that the aerodynamic load reduces the platform’s wave speed and generates a coupling effect between external and internal floats, supporting the development of hybrid floating energy systems in practical applications. Similarly8, discussed the hydrodynamic interactions and design challenges associated with such floating energy systems.

Furthermore, several studies investigated combined porous and oscillating water column designs to improve hydrodynamic performance. For example9, demonstrated that integrating a porous plate with an OWC significantly reduced horizontal wave forces (up to 52%) while maintaining high conversion efficiency. Similarly10, analyzed the influence of three-dimensional effects, wave incidence angles, and submergence depth on energy efficiency, finding that 3D configurations enhance performance near the resonance frequency. Additionally11, used numerical simulations (Open FOAM) to study an OWC positioned above a horizontal plate, and utilized numerical modelling (Open FOAM) to investigate an OWC above the horizontal plate, showing that the inclusion of an immersed plate greatly improves energy capture and stability while achieving a reflection coefficient ranging from 0.8 to 0.45.

For air turbines, floating breakwaters are preferred due to their reasonable construction costs, low environmental impact, and flexibility12. The well’s turbine has simplicity and high generator compatibility, but it suffers from a limited operating range and high axial thrust13. 14 Introduced self-pitch-controlled guide vanes to reduce shock loss, though this increased the mechanical complexity to address this.

Over the years, various BW–WEC configurations have been investigated, based on structural elements, material selection, and hydrodynamic efficiency. For example15, proposed a Pentagonal Backward Bent Duct Buoy (PBBDB) with an OWC using two turbine generators, achieving an efficiency of up to 33.4% in regular waves. 16,17 explored box-type and wedge-shaped floating breakwaters, respectively, while18 showed that adding rotary pneumatic chambers significantly reduces wave transmission (Ct from 0.96 to 0.15) and enhances energy dissipation (Cd up to 0.51). Such results demonstrate the potential of integrating OWC-based systems within floating breakwaters for combined coastal protection and renewable energy generation.

Most of the previously OWC-WEC systems have focused on experimental studies to validate numerical models or demonstrating the actual hydrodynamic behavior of the system. However, most of these experimental data belong to large-scale or fixed OWC systems, while few studies integrate small-scale or floating OWC systems with breakwater structures. This study aims to experimentally evaluate hydrodynamic performance, energy conversion, and the design of floating breakwaters. This includes studying the impact of rear wall geometries on dynamic performance and air pressure fluctuations inside vertical chambers, as well as evaluating the efficiency of pneumatic systems and turbines.

This study introduces a new hybrid design for a floating breakwater that aims to enhance wave attenuation and energy generation, which has either been minimally or not previously assessed simultaneously. The final configuration represents a hybrid and innovative design optimized for both wave attenuation and power generation. It focuses on the effect of rear wall geometry, incident wave height, and front wall draft on the performance of OWC absorber for the water depth scenarios. The study investigates how the rear wall geometry affects the water oscillation in the chamber, pressure variations, anti-reflection capability, energy extraction efficiency, as well as dissipation of wave energy of the OWC-type absorber. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section "Methodology", Experimental setup, data acquisition, and wave conditions. Section "Results and discussion", Results and discussions regarding the hydrodynamic performance of the BW-WEC, including transmission, reflection, energy dissipation, and pressure coefficient. Finally, section “Conclusions” xsprovides a summary of the main conclusions based on this study.

Methodology

Experimental configuration and data acquisition

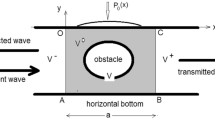

The experiments were carried out in the Wave Flume of the Fluid Laboratory, Faculty of Engineering, Port Said University (Egypt). The wave flume is 13 m long, 0.3 m wide, and 0.5 m high, as shown in Fig. 1. A flap-type wave maker was installed at one end of the flume to generate regular waves with 0.6 to 1 s periods and 4 to 12 cm high, respectively. Wave-absorbing beaches were located at both ends of the flume to reduce the wave reflection, as shown in Fig. 2. The Wave-absorbing beaches are made up of well-graded gravels having a gradual slope of 1:10.

Floating breakwater experimental model

The suspended floating breakwater model developed in this study is a considerable departure from conventional symmetric designs. These FB-WECs utilize a modified (OWC) system consisting of three key enhancements: (1) a geometrically optimized rear wall, (2) a top-mounted airflow orifice, and (3) an integrated well turbine driven by oscillating pneumatic pressure. The FB-WEC was positioned at the center section of the flume, at 5 m from the wave makers. The main structures of the FB-WEC device models were constructed using flexible Perspex sheets with a thickness of 3 mm, which allowed the vibration of the water column to be visible. These structures were then fastened to four rounded aluminum piles to ensure stability. In this context, B represents the width of the OWC chamber, d1 is the front wall draft, and d2 is the rear wall draft, as detailed in Fig. 3. Therefore, the structure has a length of 0.29 m perpendicular to wave direction, 0.16 m height, 0.25 m internal OWC width, 0.3 m outer width, the diameter of the air cylinder is 0.11 m, and 0.11 m height. Four distinct configurations were evaluated: (a) Model-A simple pontoon, (b) Model-B short slope, (c) Model-C vertical rear wall followed by short slope, and (d) Model-D long slope. Experimental test status and wave properties in this study are presented in Table 1. In addition, the Reynolds number (Re) at the inlet of the FB-WEC models was calculated to determine the flow regime. The results show that Re ≈ 1.69 × 105 to 1.03 × 106, confirming that the flow around the floating breakwaters is fully turbulent. This information is essential for interpreting wave-structure interaction and energy dissipation.

Due to the limitations of the experimental setup, the model was scaled down to fit within the wave flume. To ensure that the test conditions accurately represent a real sea environment, selecting an appropriate scale is essential to minimize the impact of wave reflections from the flume walls. The model must achieve three fundamental types of similarity with the full-scale prototype: geometric, kinematic, and dynamic. The wave parameters used in the tank should also conform to these scaling principles. In this scenario, where inertial forces dominate over viscous forces, the Froude number takes precedence over the Reynolds number. The experimental setup was designed based on Froude’s similarity law to ensure dynamic similarity between the model and the prototype19. The scaling factors for length, velocity, and time were defined, and other quantities, such as acceleration, area, wave height, and wave length, were scaled as shown in Table 2. Preserving a constant Froude number, as given in Eq. (1) across the scaling process, is critical to maintaining kinematic and dynamic similarity20.

where Up is the prototype velocity, Um is the model velocity, g is gravitational acceleration, Lp is the prototype wavelength, and Lm is the model wavelength.

Data acquisition system and data analysis

Preparations were made in the laboratory to ensure an accurate test of the model before each experiment. These preparations included validating the water depth, selecting an appropriate test duration, and calibrating the wave gauge. Each experimental setup was tested with a minimum of three runs under the same wave conditions to ensure reliability and repeatability. The data presented for all coefficients (i.e., transmission, reflection, etc.) are the average values from the replicated trials. Four HR Wallingford wave gauges were strategically positioned around the tested model to measure wave elevations. The wave probes consist of two thin, 0.1 mm wide, parallel electrodes made of stainless steel.

Three gauges (WG1, WG2, and WG3) were positioned on the incident side to measure the incoming and reflected waves, with distances of 0.4 m between WG1 and WG2, and 0.25 m between WG2 and WG3. The nearest gauge (WG3) was located 0.32 m in front of the breakwater model. A wave gauge (WG4) was positioned 2.0 m downstream of the model (wave absorber side) to measure transmitted wave heights (Ht). The wave reflection coefficient (Cr) was determined using the two-point method described by21. Although four wave gauges were installed along the flume, the use of a single gauge was considered sufficient, as the wave field in this region is predominantly progressive with negligible reflection, consistent with the findings of22. According to23, when the wavelength is relatively long compared to the chamber’s horizontal dimensions, the surface motion at one point can effectively represent the entire surface variation inside the chamber. Therefore, the use of a single gauge downstream of the OWC was considered sufficient to characterize wave transmission without significant influence from beach reflections. The wave data were recorded at approximately 34 Hz and for 20 s per run to ensure accurate and reliable measurements. A Pressure Gauge (PG) was installed on top of the pneumatic chamber to monitor air pressure changes, and it was connected to a laptop for data extraction.

The developed circuit is designed to acquire real-time data to measure the voltage and current generated by the turbine during operation, thereby enabling the calculation of electrical power consumption, as shown in Fig. 4. To determine the generator’s mechanical power (P), two instruments were employed: a voltmeter to measure the voltage (v) across the load, and an ammeter to measure the current (i) flowing through the circuit to determine the generator’s mechanical power. The voltmeter was connected in parallel with the turbine, while the ammeter was connected in series. The mechanical power output (P) was calculated as the product of the measured current (i) and voltage (v), expressed as:

Table 3 shows the standard well turbine specifications used in this study. The turbine includes eight NACA 0020-profile blades, with a hub radius of 45 mm and a blade chord of 25 mm. The tip clearance is 2 mm, and the blade span is 10 mm, as illustrated in Figs. 5 and 6. This turbine, as a simplified PTO model, does not replicate a specific turbine type but is designed to produce a consistent, measurable damping effect. The turbine is effective in oscillating flow because it has guiding vanes on both sides of the rotor.

Dimensional analysis

Key parameters characterizing the hydrodynamic performance of the breakwater include the incident-wave height (Hi), reflected-wave height (Hr), transmitted-wave height (Ht), and the internal chamber power amplitude (E). The functional relations defining the breakwater’s performance are formally given by Eq. (3):

Key parameters include the model width B, water depth d, front wall draft d1, rear wall draft d2, wavelength L, gravitational acceleration g, the specific weight of water γw, the diameter of pneumatic air d0, turbine swept area A0, and flow velocity V. The following dimensionless relationships are derived through π-theorem dimensional analysis by Eq. (4):

Equation (5, 6, 7, 8, and 9) show hydrodynamics coefficients24,25 include the reflection coefficient Cr, the transmission coefficient Ct, the energy coefficient Ce, the pressure coefficient Cp, and the dissipation coefficient Cd. These coefficients are dimensionless parameters derived from fluid mechanics principles and have been widely adopted in wave–structure interaction studies26, defined as:

where ρ is water density, A = πr2 is the turbine swept area, P is the mechanical power, and V is the flow velocity, where V = \(\frac{L}{T}\).

Acquisition of data and error analysis

An experimental reading was taken from various measuring devices at the intake and outlet of the OWC. The pressure gauge, voltmeter, ammeter, and wave gauge were used to measure the pressure inside OWC, power, and wave height, respectively.

Table 4 lists the measuring tools and their related accuracy. The standard uncertainty, U, for every measuring tool is expressed using the following formula from27:

Accuracy is denoted by a in this case27.

Evaluation uncertainty is characterized as anxiety about the validity of measured values28. A function Φ with ‘n’ independent linear parameters, like Φ = f (λ1, λ2, ….…, λn), can have its uncertainty calculated from29 .

For instance, Eq. (11) is used to determine the maximal uncertainty for any system efficiency,η, as indicated below:

Based on Eq. (12), the calculated uncertainty of η is 0.012%, suggesting that the experimental data are reliable. Similarly, the uncertainties of power and wave gauge are ± 0.012% and 0.0032%, respectively.

Results and discussion

This section presents an empirical investigation of the capture width ratio of (BW-WEC) under various accident waves and applied PTO damping levels. For consistent comparison, Model-A geometry was tested with a fixed length between the front wall and rear wall, which will serve as the case study. This section compares the experimental results of Models-A, B, C, and D to examine how different rear wall shapes affect hydrodynamic characteristics such as transmission, reflection, energy dissipation, and pressure coefficient. All results derive from experimental investigations, with the primary objective of establishing design principles for high-efficiency hybrid BW-WEC systems.The effect of turbine rotational speed on voltage, power, and electrical torque

Figure 7 illustrates the relationship between the turbine’s rotational speed (RPM) and the values of voltage, electrical power, and torque. It is observed that the voltage exhibits a proportional relationship with increasing speed, due to the electromotive force induced being directly proportional to the rate of magnetic field cutting according to Faraday’s law. In contrast, the electrical power demonstrates non-linear behavior, approximately proportional to the square of the speed, as power is the product of voltage and current, both of which increase with speed. Meanwhile, the torque increases linearly with speed, derived from the fundamental relationship between power, torque, and angular velocity (P = T × ω), indicating a gradual increase in the mechanical load on the shaft. These results highlight the critical importance of controlling rotational speed through governor systems to ensure the stability of generated voltage and power, and to maintain the turbine within a safe and efficient operational range.

Hydrodynamic performance of the BW-WEC

Wave energy spectrum

Time series for the variation of water levels and pressure drop for the standing wave obtained from different breakwaters and Wave energy spectrum in the frequency domain (Hi = 11.6 cm, Li = 144.7 cm, and T = 1.52 s at H = 30 cm) are presented in Figs. 8 and 9. Even when regular waves are generated, the measured energy spectrum does not exhibit a perfectly sharp peak due to experimental imperfections, reflections from tank boundaries, measurement noise, and the finite duration of the signal. These factors spread the energy slightly around the main frequency, resulting in a broader spectral peak instead of a singular sharp spike30,31,32.

Wave reflection coefficient

Figure 10 illustrates the variation of (Cr) with B/L across different water depths. A consistent trend is observed: (Cr) initially decreases with increasing B/L, reaching a minimum between B/L = 0.42 and 0.62 before rising again33.

For larger draft depths (d1 = 0.10 m), (Cr) remains relatively high despite the increase in B/L. This behavior indicates reduced wave energy dissipation and thus high reflections. In contrast, intermediate drafts (d1 = 0.06 m and d1 = 0.08 m) exhibit a more significant reduction in (Cr) as B/L increases, due to greater space for wave energy dissipation below the water surface, leading to lower reflection values. In the case of shallow drafts (d1 = 0.04 m), the lowest (Cr) values were recorded at higher B/L ratios, as a smaller draft depth facilitates greater wave energy absorption, thereby significantly reducing reflected energy. These results confirm that deeper drafts contribute to more effective wave dissipation and improved breakwater performance.

Most of the experimental tests were conducted in intermediate water depths (1/20 < d/L < 1/2), with three deep-water conditions (d/L > 1/2). At intermediate depths, the reduced L for a given wave period34, thus producing downward-convex Cr curves, indicating that (Cr) was higher in very shallow and deep water, the lowest (Cr) values occur at intermediate depths.

The observed decrease in (Cr) at higher B/L ratios can be attributed to two main factors (i) reduced wave reflection due to overtopping phenomena, and (ii) increased energy dissipation due to enhanced wave-structure interactions in scaled models. Among the tested models, Model-C and D showed promising performance in enhancing the BW–WEC efficiency. This can be attributed to the rear wall geometry, which enhances wave interaction and improves water column motion inside the pneumatic chamber. Additionally, the inclined rear wall helps to reduce the impact of reflected waves, thereby decreasing mechanical pressure and enhancing the breakwater’s resistance to harsh environmental conditions.

The remaining wave energy is distributed among several processes (i) viscous and turbulent dissipation, (ii) power extraction at the PTO, (iii) potential energy storage via chamber free-surface heave, (iv) rear-wall reflection, (v) transmission beyond the rear wall21. Although the curve increases quickly after reaching the minimum value, a relatively broad low reflection frequency band is observed due to a relatively small minimum (Cr = 0.138 for d = 0.25 m, d1/d = 0.27). Additionally, the hyperbolic cosine determines the particle velocity distribution along the vertical direction.

For short waves with longer wavelength, the energy concentration near the free surface reduces the hydrodynamic significance of structural draft depths on reflection coefficients. Conversely, for longer wavelengths, the energy-carrying fluid layer becomes thicker, which modifies the interaction between the wave and the rear wall. Thus, in Model-A and Model-B, the rear wall is partially immersed; the straight portion can redirect some of the waves away, while the small sloped portion dissipates the rest. Since wave reflection in Model-A and Model-B showed little sensitivity to changes in the wave period, the energy loss was mainly due to friction and turbulent flow separation, which were concentrated near the sharp edges of the breakwater.

Wave transmission coefficient

Figure 11 illustrates the variation of the (Ct) with the relative width (B/L) for different water depths. It is observed that (Ct) decreases within B/L = 0.6–0.8 before increasing again.

This behavior indicates that the wave attenuation efficiency of floating breakwaters (FBs) is greater for shorter-period waves. This is expected, as shorter-period wave exhibits significantly greater interaction with floating structures. Notably, model-C and model-D demonstrated superior performance compared to the other configurations under the tested wave conditions.

Furthermore, the suppression ability of the models was observed to improve in deeper waters. Under these conditions, shorter-period waves maintain stronger surface energy concentration, allowing for more effective dissipation by pneumatic chambers, which is consistent with fixed breakwater performance35. Pneumatic chambers significantly reduced wave transmission coefficients across all tested wave periods. In addition to scattering effects from rear-wall configurations, transmission attenuation was achieved through: (a) reduced radiation toward the leeward side via motion suppression, and (b) enhanced energy dissipation by pneumatic chambers, which reduced both reflected and transmitted wave energy.

A (Ct) value below 0.5 demonstrates the efficiency of the floating breakwaters. This efficiency signifies effective wave-structure interactions that decrease the intensity of the higher wave components36. This phenomenon may result from intense surface oscillations inside the pneumatic air chamber. When the wave comes against the breakwater, a sudden change in water particle motion converts to energy attenuation. Finally, steeper waves cause more turbulence, leading to sudden changes in the velocity and acceleration of water particles. This increased turbulence contributes to greater energy loss, thereby contributing to a further reduction in (Ct).

Wave energy dissipation

The effect of wave height energy dissipation was initially investigated across four breakwater models. Figure 12 illustrates how the dissipation coefficient (Cd) varies with B/L across three different water depths. For all models, (Cd) uniformly rises with B/L, while the transmission coefficient (Ct) decreases, indicating that the breakwaters reduce wave transmission primarily through enhanced turbulence and vortex shedding. At the same time, the reflection coefficient (Cr) remained moderate, suggesting that energy loss is dominated by dissipation rather than reflection.

The results show that increasing the inlet depth (d1) enhances the efficiency of the breakwater, with optimal performance observed at the front wall draft (d1 = 0.1 m). In addition, deep water depth (d = 0.3 m) contributes to more efficient wave energy dissipation in all models. Among the evaluated configurations, Model-D and Model-C demonstrate the highest overall efficiency, especially at larger drafts and depths, making them the most effective for wave attenuation.

In contrast, Model-A and Model B show moderate performance, making them more suitable for shallow water and small drafts. Models C and D perform better primarily due to their enhanced design features, which enable them to dissipate wave energy more effectively.

Both models are designed for deep water and feature optimized construction designs to dissipate energy through mechanisms such as vortex buckling and friction effects. Notably, Model-D, in particular, benefits from an inclined rear wall, which increases the water column height and the natural period of the barrier, which improves its efficiency for both short and long periods. Similarly, Model-C exhibits strong performance due to its balanced design, which enables consistent efficiency across various wave conditions. In contrast, Model-A and Model-B lack the design functions required for efficient energy efficiency, such as adequate vent depth and effective air or water flow management.

This results in limited performance, especially under long-wave or deep-water conditions, making Model-C and Model-D the preferred options for optimal coastal barriers. These findings highlight the critical influence of flow dynamics and water depth on the optimal performance of wave barriers37.

Variations in air pressure within the pneumatic chambers and the wave power coefficient

Variation in the dimensionless pressure fluctuation amplitude inside the chambers and the energy coefficient is plotted against B/L for four different drafts, presented in Fig. 13 . At a shallow water depth (d = 0.20 m), both the (Ce) and (Cp) remain relatively low across all drafts due to increased wave breaking and bottom friction, an effect most significant for smaller drafts with d1 = 0.04 m. As the water depth increases to d = 0.25 m, energy dissipation decreases, leading to improved performance, particularly for drafts d1 = 0.08 m and d1 = 0.10 m. At the greatest water depth d = 0.30 m, the combination of the largest draft d1 = 0.10 m and Model-D yields the highest of both (Cp) and (Ce), indicating optimal energy transfer efficiency and stable hydrodynamic performance. This analysis demonstrates the importance of deep-water depth in reducing energy losses and highlights the superior performance of large forward drafts, which minimize leakage and turbulence. Therefore, the combination of d = 0.30 m, d1 = 0.10 m is effective, and Model-D is the most effective configuration for increasing energy capture and efficiency.

For short waves, breakwater blockage effectively prevents wave energy transmission beneath the structure between the front and rear walls35. Consequently, higher water elevations produce larger strokes and compress more air within the chamber. Analysis shows that Model-D with the forward draft d1 = 0.10 m demonstrates the best performance in terms of both (Cp) and (Ce). For instance, at B/L = 1.0, (Cp) and (Ce) values reach approximately 0.85 and 0.75, respectively, indicating consistent pressure flow and efficient energy transfer. On the other hand, Model-C with d1 = 0.08 m achieves lower values (Cp = 0.8 and Ce = 0.7), making it less effective at larger B/L ratios, but other models perform lower; such as Model-A with d1 = 0.06 m reaches only (Cp) = 0.7 and (Ce) = 0.6. Therefore, Model-B with d1 = 0.10 m is considered the optimal choice for achieving the highest efficiency and dynamic performance, especially at higher B/L. The performance of the well turbine is significantly affected by factors such as the B/L ratio, structural configuration, and the pressure coefficient (Cp), all of which affect its dynamic behavior. Initially, the Turbine energy conversion efficiency is higher as the internal chamber air pressure and pressure distribution increase. As air velocity rises, the energy coefficient (Ce) increases gradually until it reaches a certain threshold. Beyond this point, due to elevated pressure and increased turbulence caused (Ce), either stabilizes or declines, resulting in reduced turbine efficiency.

Table 5 presents a comparison of the hydrodynamic performance for five different WEC models, highlighting the distinct advantages of the current study’s inclined rear wall. The (Ce) comparison showed the important energy capture advantage of the current model and the porous plate model 9, both achieving high Ce ranges (0.40–0.85) relative to the other systems, including the fixed OWC-3D38. Which had diminished ability to dissipate energy. The results from the current model can be directly connected to the inclined rear wall, which resulted in a more favorable level of incident wave reflection and performance (lower Cr values of 0.25–0.45), whereas Cr ≥ 0.7 for38;11. Less wave reflection therefore translates to greater incident energy into a system. Crucially, the presented breakwater operates effectively across a broader spectrum of wave conditions (B/L = 0.2–1.2), demonstrating greater operational flexibility than the fixed designs of38 (B/L = 0.27) and11 (B/L = 0.29), which are optimized for a narrow range. While porous plates9 also show a wide operational range (B/L = 0.19–1.055), and their wave protection capability (higher Ct) can be less consistent. In conclusion, the data in Table 5 substantiates that the inclined wall design offers a balanced and robust solution, combining the high energy capture efficiency (Ce) of advanced OWC systems with the excellent wave attenuation (low Ct) and operational bandwidth necessary for effective coastal protection, outperforming traditional rigid designs and competing effectively with other advanced flexible systems.

For Mediterranean-like wave conditions representative of Port Said, a significant wave height of Hi = 1.5 m and an energy period of Te = 6 s was assumed. The available wave power per unit crest length is given by Eq. (13), (14), and (1540:

where Hi is wave height (m), Te is energy period (s), P wave is wave power (kW/m), B effective width (m), Pel is electrical power output, E day is daily energy production, and A is availability Factor. The system delivers an electrical output of approximately 4.2 kW, which translates to nearly 86 kWh per day under an assumed operational availability of 85%. This level of energy production is sufficient to meet the demands of small-scale coastal infrastructure such as navigation aids, environmental monitoring stations, and basic desalination units. The hybrid FB–WEC system benefits from wave energy dissipation through pneumatic damping, which also reduces the breakwater displacement and construction costs. By combining coastal protection with energy generation, the system leverages cost- and space-sharing while protecting against erosion and sheltering coastal installations. The hybrid breakwater–WEC system is best suited for semi-sheltered coastal areas, such as harbor entrances, offshore islands, and Mediterranean-like coasts (e.g., Port Said).

Conclusions

This study presents a novel design of a suspended floating breakwater with a wave energy converter (WEC). The aim was to investigate the hydrodynamic performance of various rear wall shapes with different drafts and water depths. The primary performance indicators included the wave reflection coefficient (Cr), transmission coefficient (Ct), dissipation coefficient (Cd), pressure coefficient (Cp), and energy coefficient (Ce). The main findings can be summarized as follows:

-

The geometry of the rear wall of FB-WEC significantly affects the characteristics inside the air column at different drafts. Among the four configurations, Model-D with a long slop rear wall generated the highest internal water elevation and pressure, while the other geometries produced the lowest.

-

The pneumatic chambers effectively attenuated wave transmission across all tested wave period. Beyond the wave scattering induced by rear wall geometry, the decrease in wave transmission was attributed to two mechanisms: (a) the motion-generated radiate waves into the leeward side of the breakwater were lessened, and (b) additional energy dissipation and partial energy conversion into pneumatic power through the PTO system.

-

The (Cr) decreased by increasing B/L, reaching a minimum of 0.139 before rising again at smaller drafts (d1 = 0.04 m). Models-C and D demonstrated promising performance due to the rear wall design, which enhances energy absorption and reduces mechanical stress.

-

The (Ct) decreases as B/L increased within the range of (0.6–0.8) before rising again, indicating higher effectiveness of the floating breakwaters in attenuating shorter waves.

-

Both the (Cp) and (Ce) increased with greater water depth, as energy losses due to bottom friction were reduced, which improves energy dissipation efficiency. The most effective configuration to maximize energy and dissipation coefficient is Model-D with a draft depth of d1 = 0.10. Achieving the highest (Cp = 0.85), and (Ce = 0.75), making it the optimal option for effective wave attenuation.

Model-D was identified as the optimal configuration because it achieved the highest overall conversion efficiency and stable hydrodynamic behavior compared to Models B and C. While Model-B exhibited low capture efficiency and Model-C from larger oscillations, Model-D provided a balanced performance between efficiency and stability. Notably, this performance was achieved without increasing the front width, confirming its scalability and reliability under regular wave conditions, with promising applicability to irregular sea states.

Overall, the proposed hybrid floating breakwater–WEC system demonstrates strong potential for practical deployment in coastal areas where shoreline protection and renewable energy generation are simultaneously required. In particular, semi-enclosed basins, ports, and small coastal communities in moderate-energy seas, such as the Mediterranean, are ideal locations for implementation, providing both wave attenuation and a sustainable power supply.

While the experimental results are promising, several limitations should be acknowledged. The experiments were conducted under regular wave conditions, with limited water depths, which may not fully capture the dynamic response of a realistic floating system. Moreover, the small-scale model and simplified PTO mechanism may not perfectly replicate full-scale performance.

Future work should therefore focus on large-scale experiments, testing under irregular and extreme wave conditions, and integrating a realistic mooring system and optimized PTO design to enhance the accuracy, reliability, and practical applicability of the proposed configuration.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- A0 :

-

Swept area of the turbine [m2]

- A:

-

Availability Factor

- a:

-

Accuracy

- B:

-

Width of model [m]

- bin:

-

Internal width [m]

- C:

-

Blade chord [mm]

- Cr :

-

Reflection coefficient

- Ct :

-

Transmission coefficient

- Cd :

-

Dissipation coefficient

- Ce :

-

The energy coefficient

- Cp :

-

The pressure coefficient

- d:

-

Water depth [m]

- d1 :

-

The immersed front wall [m]

- d2 :

-

The immersed rear wall [m]

- d0 :

-

The diameter of pneumatic air [m]

- Eday :

-

Daily energy production [Wh]

- G:

-

Gravitational acceleration [m/s2]

- Ht:

-

Transmitted wave height [m]

- Hr:

-

Reflected wave height [m]

- Hi:

-

Incident wave height [m]

- He:

-

Wave height[m]

- I:

-

Current [ Ampere]

- L:

-

The incident wavelength [m]

- Le:

-

Length of model [m]

- Lp :

-

Prototype wavelength [m]

- Lm :

-

Model wavelength [m]

- P:

-

Electrical power output [W]

- Rh:

-

Blade hub radius [mm]

- Rt:

-

Blade tip radius [mm]

- S:

-

Turbine blade span [mm]

- Ts:

-

Energy period[s]

- t:

-

Maximum blade thickness[mm]

- U:

-

Standard uncertainty

- Up :

-

Prototype velocity [m/s]

- Um :

-

Model velocity [m/s]

- V:

-

Velocity [m/s]

- v:

-

Voltage [Volt]

- z:

-

Number of blades

- γw :

-

Specific weight of water [N/m3]

- β:

-

Stagger angle [degree]

- ρ:

-

Density of water, [kg/m3

- ω:

-

Angular speed (red/s)

- BBDB:

-

Breakwater Bent Duck Buoy

- BW-WEC:

-

Breakwater Wave Energy Converter

- OWC:

-

Oscillating Wave Column

- PBBDB:

-

Pentagonal Backward Bent Duct Buoy

- PG:

-

Pressure Gauge

- PTO:

-

Power Take Off

- WEC:

-

Wave Energy Converter

- WG:

-

Wave Gauge

References

Hagerman, G. M. Jr. “Oceanographic design criteria and site selection for ocean wave energy conversion”, in Hydrodynamics of Ocean Wave-Energy Utilization: IUTAM Symposium Lisbon/Portugal. Springer 1986, 169–178 (1985).

Cruz, J. Ocean wave energy: current status and future prespectives (Springer Science & Business Media, Berlin Heidelberg, 2007).

Zhang, Y., Zhao, Y., Sun, W. & Li, J. Ocean wave energy converters: Technical principle, device realization, and performance evaluation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 141, 110764 (2021).

T. V Heath, 2012 A review of oscillating water columns. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 370 (1959): 235–245 https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2011.0164

Wang, M., Qu, M., Wang, T. & Iglesias, G. Power performance and motion characteristics of a floating hybrid wind-wave energy system. Ocean Eng. 318, 120184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.120184 (2025).

Wang, T. et al. A coupling framework between OpenFAST and WEC-Sim. Part I: Validation and dynamic response analysis of IEA-15-MW-UMaine FOWT. Renew. energy 225, 120249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2024.120249 (2024).

Jalani, M. A. et al. Numerical study on a hybrid WEC of the backward bent duct buoy and point absorber. Ocean Eng. 267, 113306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2022.113306 (2023).

Lauria, A., Loprieno, P., Francone, A., Leone, E. & Tomasicchio, G. R. Recent advances in understanding the dynamic characterization of floating offshore wind turbines. Ocean Eng. 307, 118189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.118189 (2024).

Zhuang, Q., Ning, D., Mayon, R. & Zhou, Y. Experimental and numerical investigation of a land-fixed breakwater-type wave energy converter: An OWC device and a porous plate. Coast. Eng. 194, 104614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coastaleng.2024.104614 (2024).

Sun, Y., Ning, D., Mayon, R. & Chen, Q. Experimental and numerical investigation on hydrodynamic performance of a 3D land-fixed OWC wave energy converter. Appl. Ocean Res. 141, 103805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apor.2023.103805 (2023).

Wang, C. & Zhang, Y. Hydrodynamic performance of an offshore oscillating water column device mounted over an immersed horizontal plate: A numerical study. Energy 222, 119964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2021.119964 (2021).

Dai, J., Wang, C. M., Utsunomiya, T. & Duan, W. Review of recent research and developments on floating breakwaters. Ocean Eng. 158, 132–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2018.03.083 (2018).

Halder, P., Samad, A. & Thévenin, D. Improved design of a Wells turbine for higher operating range. Renew. energy 106, 122–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2017.01.012 (2017).

T. Setoguchi, K. Kaneko, H. Taniyama, H. Maeda, and M. Inoue, “Impulse thrbine with self-pitch-controlled guide vanes for wave power conversion: Guide vanes connected by links,” Int. J. Offshore Polar Eng., vol. 6, no. 01, 1996.

Chen, Q. et al. On the hydrodynamic performance of a vertical pile-restrained WEC-type floating breakwater. Renew. energy 146, 414–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2019.06.149 (2020).

Liu, Z. & Wang, Y. Numerical studies of submerged moored box-type floating breakwaters with different shapes of cross-sections using SPH. Coast. Eng. 158, 103687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coastaleng.2020.103687 (2020).

F. Madhi, R. W. Yeung, and M. E. Sinclair, “Energy-capturing floating breakwater,” Aug. 16, 2016, Google Patents.

He, F., Huang, Z. & Law, A.W.-K. Hydrodynamic performance of a rectangular floating breakwater with and without pneumatic chambers: An experimental study. Ocean Eng. 51, 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2012.05.008 (2012).

Lyu, X. et al. Design and experimental tests for novel shapes of floating OWC wave energy converters with the additional purpose of breakwater. Ocean Eng. 328, 121031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfluidstructs.2021.103328 (2025).

Windt, C., Davidson, J. & Ringwood, J. V. Numerical analysis of the hydrodynamic scaling effects for the Wavestar wave energy converter. J. Fluids Struct. 105, 103328 (2021).

Goda, Y. & Suzuki, Y. Estimation of incident and reflected waves in random wave experiments. Coast. Eng. 1976, 828–845 (1976).

Calvert, R., Mol, J., Sutherland, B. R. & van den Bremer, T. S. Attenuation of progressive surface gravity waves by floating spheres. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 1770 (2025).

Brendmo, A., Falnes, J. & Lillebekken, P. M. Lineår modelling of oscillating water columns including viscous loss. Appl. Ocean Res. 18(2–3), 65–75 (1996).

Ram, G., Saad, M. R., Abidin, N. Z. & Rahman, M. R. A. Hydrodynamic performance of a hybrid system of a floating oscillating water column and a breakwater. Ocean Eng. 264, 112463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2022.112463 (2022).

H. M. Teh and H. Ismail, “Hydraulic characteristics of a stepped-slope floating breakwater,” in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, IOP publishing, 2013, p. 12060.https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/16/1/012060

Peng, W., Zhang, Y., Zou, Q., Zhang, J. & Li, H. Effect of varying PTO on a triple floater wave energy converter-breakwater hybrid system: An experimental study. Renew. Energy 224, 120100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2024.120100 (2024).

Gupta, S. V. Measurement uncertainties: physical parameters and calibration of instruments (Springer Science & Business Media, Berlin Heidelberg, 2012).

J. P. Holman and W. J. Gajda, “Experimental methods for engineers,” (No Title), 2001.

Soliman, M. S., El Yassen, Y., El-Nahhas, K. & Elminshawy, N. A. S. Performance investigation of solar still utilizing affordable thermal storage material and parabolic trough concentrator: An experimental investigation. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 201, 107473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2025.107473 (2025).

M. A. Donelan, J. Hamilton, W. Hui, (1985) Directional spectra of wind-generated ocean waves. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 315 (1534): 509–562

Adcock, T. A. A. & Taylor, P. H. The physics of anomalous (‘rogue’) ocean waves. Reports Prog. Phys. 77(10), 105901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2025.107473 (2014).

Longuet-Higgins, M. S. On the distribution of the heights of sea waves: Some effects of nonlinearity and finite band width. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 85(C3), 1519–1523 (1980).

Zhu, S. & Chwang, A. T. Investigations on the reflection behaviour of a slotted seawall. Coast. Eng. 43(2), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-3839(01)00008-4 (2001).

Wibowo, A. A., Tawekal, R. L., Ajiwibowo, H. & Wurjanto, A. two-dimensional physical modeling of multi chamber skirt breakwATER (MCSB). Geomate J. 20(78), 36–43 (2021).

Drimer, N., Agnon, Y. & Stiassnie, M. A simplified analytical model for a floating breakwater in water of finite depth. Appl. Ocean Res. 14(1), 33–41 (1992).

Yuan, H., Zhang, H., Wang, G. & Tu, J. A numerical study on a winglet floating breakwater: Enhancing wave dissipation performance. Ocean Eng. 309, 118532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.118532 (2024).

López, I., Rosa-Santos, P., Moreira, C. & Taveira-Pinto, F. RANS-VOF modelling of the hydraulic performance of the LOWREB caisson. Coast. Eng. 140, 161–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coastaleng.2018.07.006 (2018).

Xu, C. et al. Performance of a closely-spaced array of circular U-OWC devices for wave power extraction and breakwater applications. Ocean Eng. 324, 120654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2025.120654 (2025).

Deng, Z., Wang, C., Wang, P., Higuera, P. & Wang, R. Hydrodynamic performance of an offshore-stationary OWC device with a horizontal bottom plate: Experimental and numerical study. Energy 187, 115941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2019.115941 (2019).

Gallardo, J. M. et al. Experimental research into aeroelastic phenomena in turbine rotor blades inside arias eu project. J. Turbomach. 146(7), 71009. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4065621 (2024).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

There are five authors for this research, who are; B. Hamed, M. Elkiki, Sh. Abd-Ellah, Yassen El.S. Yassen, R.Diab their participation was equal.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

We (the authors) assure that we are committed to Ethics provided by the journal. ,

Consent to participate

All authors agree to participate.

Consent to publish

All authors agree to publish in the journal.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hamed, B., Elkiki, M., Abdellah, S. et al. Assessing the impact of novel hybrid floating breakwater-WEC systems on hydrodynamic performance and sustainable energy outputs. Sci Rep 16, 7189 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37290-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37290-8