Abstract

This work addresses enhancing the performance of Perovskite solar cells by incorporating ellipsoid plasmonic nanoparticles of Titanium Nitride (TiN) into the pure methylammonium lead iodide (CH3NH3PbI3) active layer. The device structure consists of ITO/TiO2/CH3NH3PbI3/PEDOT: PSS/Au. The study is conducted using finite difference time domain method for the optical studies and SCAPS-1D software for the electrical parameters, the proposed structure managed to boost the absorption of the perovskite solar cell to levels more than 90% in the visible and near infrared range (NIR), and a broad absorption band from 400 nm to 1200 nm is obtained, which is reflected as an electrical performance with short circuit current density of 46.84 mA/ cm2, and open circuit voltage of 0.8924 V, a fill factor of 76.22%, and an impressive power conversion efficiency of 31.8%. These results showcase the plasmonic potential of TiN refractory metal nanoparticles in enhancing the performance of perovskite solar cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With increasing concerns over climate change, photovoltaics (PV) play a crucial role in the global transition to cleaner and more sustainable energy sources. PV involves the conversion of light into usable electrical energy through PV cells, more often called solar cells (SCs). Considering the sun provides more than 10,000 times the current annual global energy consumption, researchers and engineers have focused on improving photovoltaic technology to make it more efficient, cost-effective, and widely applicable1.

Perovskite solar cells (PSCs) are a third-generation SC that have emerged rapidly as a leading technology in PV, due to performance improvements that have been observed in recent years. These cells have shown efficiency levels in converting light into electricity comparable to well-established photovoltaic technologies like silicon2,3. These massive advancements have gotten the deserved consideration of both academics and professionals alike, making PSCs a key stone in the renewable energy field. PSCs have numerous unique properties, from a broad absorption spectrum to high power conversion efficiencies, long diffusion lengths, relatively simple synthesis processes, and low manufacturing costs4,5,6,7, making PSCs an attractive candidate for future SC technologies.

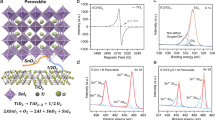

Methylammonium lead iodide (CH3NH3PbI3) perovskite, in particular, has been extensively studied for SC applications because of its direct bandgap of ~ 1.55 eV, which is very close to the ideal for the Shockley-Queisser optimal bandgap (~ 1.34 eV) for single-junction SC4,8,9,10,11,12,13. CH3NH3PbI3 absorbs strongly in the visible spectrum; its absorption coefficient decreases for wavelengths longer than 750 nm, limiting harvesting of the near-infrared portion of the solar spectrum14. To meet the ever-increasing energy demand, further improvements in light harvesting and charge collection are crucial.

Plasmonics is the collective oscillations of free electrons localized at the surfaces of metallic nanostructures (usually Ag, Au, or Al)15,16,17,18,19,20,21. The induced electric charge fluctuations result in electromagnetic oscillations. At resonance, the electric field of the incident electromagnetic waves drives the collective oscillations of the electrons in the metal to create a strong charge displacement and field concentration. This coupling between the incident electric field and the electrons is called localized surface plasmons (LSPs)22,23,24,25. LSPs are often higher than the exciting fields and located at the plasmonic material surface. This amplified field enhances light absorption and the scattering cross section for the incident electromagnetic waves, effectively increasing the optical path of the light26. Furthermore, it creates a strong near field in the proximity of the metal particle surface, which in turn improves light absorption in the SC active absorbing layer, enhancing the performance of the device27. Refractory metals like Titanium (Ti) are known for their high melting points and their capability to work normally at higher temperatures than other metals, making them more suitable materials as solar absorbers. Studies have shown that metamaterials made of Ti and its composites have a wide absorption spectrum and strong plasmon behavior. Moreover, Ti is more abundant in Earth’s crust than traditional precious metals such as gold and silver, which can lower the cost28,29,30,31,32,33,34.

In this study, ellipsoid plasmonic nanoparticles based on titanium nitride as a refractory material are introduced with rectangular and hexagonal arrangements. The absorber layer based on CH3NH3PbI3 is studied with/without the plasmonic nanoparticles. The absorptance was calculated in the wavelength range from 300 to 1500 nm, in the case of PSC with plasmonic nanoparticles, a broadband from 400 to 1200 nm having an absorption ≥ 90% is obtained compared to the basic perovskite without the nanoparticles, which achieved a relatively narrow band from 400 to 750 nm. The electrical parameters obtained are as follows: the short-circuit current density (Jsc) is 46.84 mA/cm², the open-circuit voltage (Voc) is 0.8924 V, the fill factor (FF) is 76.22%, and the power conversion efficiency (PCE) is 31.8%.

Simulation and methodology

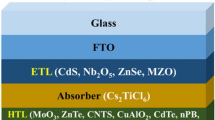

This research focuses on the study of optical behavior using a simulation based on FDTD and electrical outcomes by the SCAPS simulator. The main objective was to assess the impact of the integrated nanoparticles on the device’s performance to offer insights that enable the development of more efficient PSCs. The proposed device structure, as shown in Fig. 1 started as a 400 (x) nm * 400 (y) nm, normal (n–i–p) SC structure with the configuration of: indium tin oxide (ITO) layer as a transparent conducting front electrode (TCO), TiO2 as both an electron transport layer (ETL) as well as an anti-reflection coating35, CH3NH3PbI3 as the perovskite absorber layer, poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT: PSS) as a hole transport layer (HTL)36,37, and an Au layer that acts as a back reflector to limit transmission as well as a back contact. To strengthen the local electromagnetic field, a hexagonal lattice array of ellipsoid Titanium Nitride (TiN) nanoparticles is integrated into the perovskite layer.

All is enclosed with a glass layer to provide support and protect the PSC from degradation over time due to exposure to moisture, oxygen, and UV light. The dimensions of every layer and the radii of the ellipsoids are shown in Table 1.

Optical simulation

The optical simulation was carried out using the FDTD method, as shown in Fig. 2. A plane wave source is used with wavelength in the 300–1500 nm range, the structure variation is confined in the Z direction, with the X and Y directions being fully periodic, therefore periodic boundary conditions were applied to X and Y directions while perfectly matched layers boundary conditions (PML) were applied to the Z direction to prevent further reflections. Proper meshing was used to capture the fine changes of the electric field near the interfaces and to account for the continuous change of the ellipsoid surface, the meshing steps used were 3*3*2.5 nm and meshing convergence processes were executed to ensure that further meshing refinement is not necessary. The optical constants (n and k) of TiO2 were obtained from ref38., CH3NH3PbI3 from ref39., PEDOT: PSS data points extracted from supplementary materials (Figure S2) from ref40., TiN from ref41., ITO from ref42., Au from ref43. These wavelength-dependent values were directly imported into the FDTD simulation.

After performing the simulation, the used source was normalized to the standard AM1.5G (air mass solar spectrum), to ensure that the resulting optical generation profiles are accurately calculated across the relevant wavelength range of the source. Power monitors were used to calculate the reflectance (R) and transmittance (T), thus calculating the absorptance (A) using the relationship: A(λ) = 1 - R - T. The FDTD software calculates the optical generation as a 3-dimensional matrix using this expression36,44:

where Pabs is the absorption spatial power density, and its expression is:

Electrical simulation

Electrical simulations were conducted by SCAPS-1D, which as the name implies, is a one-dimensional simulation tool specifically designed for SCs, developed by the Department of Electronic and Information Systems (ELIS) at Ghent University45,46,47.

SCAPS-1D is based on three equations, Poisson’s (3), electrons (4), and holes (5) steady-state continuity equations:

Where Gp and Gn are the hole and electron generation rates, respectively. \(\:{\tau\:}_{n}\) and \(\:{\tau\:}_{p}\) are the lifetimes of electrons and holes, respectively; Dp and Dn are the hole and electron diffusion coefficients, respectively; \(\:q\) is the charge of the electron; \(\:\psi\:\) is the electrostatic potential; \(\:{\mu\:}_{n}\) and \(\:{\mu\:}_{p}\) are the mobilities of electrons and holes, respectively; \(\:n\left(x\right)\) and \(\:p\left(x\right)\) are free electrons and holes concentrations; \(\:{p}_{t}\left(x\right)\) and \(\:{n}_{t}\left(x\right)\) are the concentrations of trapped holes and electrons, respectively. \(\:{N}_{d}^{+}\left(x\right)\) and \(\:{N}_{a}^{-}\left(x\right)\) are the donor and acceptor concentrations, respectively; \(\:\xi\:\) is the electric field; \(\:\text{x:}\)is the direction along the thickness of the SC48.

Since SCPAS-1D software is only a one dimensional solver and the optical generation profiles obtained from the FDTD are 3D matrices, the 3D generation matrix is processed averaging the data over the lateral dimensions (x and y) to produce a 1D profile in the Z direction, hence we imported the obtained 1D profile into SCAPS-1D to measure the effect of the ellipsoid TiN plasmonic nanoparticles on the performance of the device. The workflow was integrated using MATLAB for data processing and analysis. This approach is much faster and requires less computational power than the computationally intensive 3D electrical simulations. Although this method does not capture edge effects and possible carrier dynamics in the lateral dimensions, it has a second-order impact on the performance since the carrier transport behavior in thin-film SCs is predominantly in the vertical direction. The electrical properties of the materials and the recombination parameters, as shown in Table 2 were obtained from the literature49,50,51.

Results and discussion

The proposed structure exhibits a broad absorption spectrum < 0.9 from 400 to 1200 nm (as shown in Fig. 3), with the remaining parts of the spectrum having solid performance as well, indicating that almost all of the solar spectrum is being utilized in the optical generation, Titanium nitride (TiN) nanoparticles are strong broadband absorbers with absorption from the visible range into the near-infrared (NIR) region, even though they typically have their primary plasmonic resonance in the visible range around 450 nm. Broadband absorption in TiN is due to the combination of several factors; TiN has unique dielectric properties that enable an extended and red-shifted localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR), the absorption tails can extend well past 800 nm52. Modifying the shape of TiN nanostructures like dimers, nanocones, or disordered metasurfaces and in our case nano-ellipsoids can also widen and enhance the absorption spectrum, improving light trapping and resonance coupling over a large range of wavelengths53,54,55. The effect of the plasmonic TiN ellipsoids is clearly evident in maintaining high absorption in wavelengths longer than 750 nm meanwhile in the control structure, without the TiN ellipsoids, the absorption drops to an average of 0.25 beyond the 750 nm mark. The role of the gold back contact is shown in maintaining zero transmission across the entire spectrum and therefore A = 1-R. In the following analysis, the absorptance (A) will only be considered for convenience.

.

Figure 4 shows the solar radiation going through the basic perovskite layer at wavelengths of (a) 800 nm and (b) 1100 nm. The color maps in Fig. 4 represent the normalized electric field intensity |E|² (a.u.) inside the perovskite absorber layer, obtained from the field profile in the FDTD simulation. Dark blue corresponds to regions of negligible field intensity, i.e., minimal absorption while value > 1 indicates field enhancement. In the absence of plasmonic nanoparticles, the radiation remains largely unchanged with minimal absorption. This behavior can be attributed to the reduction in the material’s absorption coefficient at longer wavelengths within the near-infrared (NIR) region, which accounts for the observed decline in absorption beyond 750 nm. At longer wavelengths, the perovskite’s absorption is weak, so the light penetrates the active layer and reflects from the Au back contact. These reflections create standing waves. At an antinode of a standing wave, the electric field amplitude can exceed the incident amplitude due to interference which explains observing values of 1.2 or more in the basic perovskite. Figure 5 presents the XY-profile at two wavelengths (a) 800 nm and (b) 1100 nm for the structure with integrated TiN nanoparticles, whose plasmonic effect leads to the excitation of LSPs, which enhances the electric field near the nanoparticles’ surfaces. This results in a stronger interaction between the incident light and the perovskite active layer and hence improved light absorption, particularly in the NIR range, where the basic perovskite lacks. Figure 6 extends the analysis to the XZ-plane at the same two wavelengths, this cross-sectional view further confirms the effect of the TiN nanoparticles on enhancing the local electromagnetic fields in the NIR region.

To further investigate our design, a parameter sweep analysis is applied to all key parameters like shape, size, and material of the nanoparticles.

Figure 7.(a) illustrates the effect of the various common plasmonic materials such as gold (Au), silver (Ag), and aluminum (Al) against TiN. With its high melting point and strong plasmonic behavior as a refractory metal, TiN demonstrates superior absorption, especially in the NIR region, in comparison to the other common plasmonic materials, while being more cost-effective. In Fig. 7.(b), the effect of the nanoparticle shape on absorption is observed. The absorption by ellipsoids is higher across visible and NIR wavelengths than for both the spheres and cylinders. The difference can be explained by the excitation of both transverse and longitudinal modes in the ellipsoids due to its geometric properties that combine the advantages of both the curved surface of spheres and longitudinal length of cylinders in one shape, which in turn enhances light trapping and plasmonic coupling in the NIR region.

The effect of various radius values in the x, y, and z directions can be noticed, from Fig. 8.(a). r(x, y) = 60 nm is found to be the optimal value for maximizing the absorptance, while for r(z) as shown in Fig. 8.(b), the values of 110 nm and 130 nm are quite close, but 110 nm has a slightly higher average absorptance across the whole spectrum. Changes in the ellipsoid dimensions can affect the local field enhancement and the overall absorptance, emphasizing that precision in choosing the nanoparticle dimensions is necessary for optimizing the device performance.

Figure 9.(a) compares hexagonal and rectangular arrays, such that between 400 and 1000 nm, absorptance is nearly saturated. However, the hexagonal array has higher absorption at wavelengths < 1000 nm. This is due to higher packing density and the 6-fold symmetry of the hexagonal lattice, which enables this type of arrangement to support stronger plasmonic resonances and field localization. Figure 9.(b) shows the effect of different values of lattice constant (G). Array constant (G) affects the periodicity of the nanostructure, which changes the surface plasmon polariton (SPP) coupling efficiency and therefore the photonic band gap position, leading to gradual degradation of coupling efficiency and field enhancement as G increases, particularly at wavelengths greater than 800 nm. The absorption is maximum at G = 140 nm, which in turn increases the pitch of the structure from 400 (x) nm* 400 (y) nm to 420 nm *420 nm to maintain the periodicity of the structure.

The obtained optical generation profile was then averaged over the lateral dimensions (x and y), then imported to SCAPS-1D, and after considering the defects of every layer and the interfaces between the different layers and recombination losses, we obtained impressive results of:

Voc = 0.8924 V, Jsc= 46.84 mA/cm2, Fill factor (FF) = 76.02% and power conversion efficiency (PCE) = 31.8%, very close to the Shockley–Queisser theoretical limit. Figure 10 shows the J-V curves obtained from SCAPS-1D for the basic perovskite material with and without the TiN refractory metals, which introduced a significant enhancement for PSC performance.

A comparison with the basic perovskite cell using the same methodology shows 80% enhancement in Jsc and 74.7% enhancement in PCE shown in Table 3 which indicates that the plasmonic enhancement of the absorption leads to a significant increase in optical generation and therefore the conversion efficiency.

To place our results in context, Table 4 represents this work compared to reported benchmark representative studies that embedded plasmonic nanoparticles into PSCs. The incorporation of plasmonic nanoparticles to date in PSCs has increased the performance but only reported moderate improvements in PCE (between 25 and 47%). For example, Au@TiO₂ core-shell nanospheres improved the PCE from 12.59% to 18.2% (≈ 44% increase) through additional exciton generation and charge separation56. The multilayer triple core-shell designs added to MASnI₃ absorbers achieved simulated efficiencies of 30.18% (≈ 64% increase) by absorbing more light and providing stability57. Similar to the previous 2 examples, Ag@SiO₂ and SiO₂@Ag@SiO₂ structures improved PCE from 14.8% to 19.7% (≈ 33% increase) through UV laser pumping through reduction of recombination58. The Au nanoparticles deposited at the ETL interfaces improved the subsequent performance of the device by improving conductance and crystallinity59. Compared to the previously mentioned benchmarks, the improvement delivered in our TiN ellipsoidal nanoparticle design has significantly larger relative increase in efficiency from 18.2% to 31.8% (≈ 74.7%). This is due to the combined contributions made in maximum carrier generation from working with anisotropic ellipsoids, which allows for multiple plasmonic modes to be excited, along with strong near-field scattering, giving rise to broadband absorption extending well into the NIR spectral region.

The results (Voc = 0.892 V, Jsc = 46.84 mA/cm², FF = 76.0% and PCE = 31.8%) are very close to the Shockley–Queisser limit. While these results are more optimistic than most experimental studies described in the literature, it is important to remember that these results are based on idealized optical and electrical simulations. We did consider plasmonic enhancement and any shading due to the TiN nanoparticles. However, the net balance was clearly weighted towards light-harvesting improvement. In practical use, experimental results can vary and normally will be lower because of material quality and defects in fabrication, but our results demonstrate the theoretical capabilities of TiN ellipsoids for near-limit perovskite SCs efficiencies. These findings provide the researchers with a clear benchmark to build on and illustrate the strong potential of TiN ellipsoids for advanced PSCs, pushing the walls toward their theoretical limits.

Conclusion

Throughout this work, we have shown using optical (FDTD) and electrical (SCAPS) simulations that embedding ellipsoid titanium nitride (TiN) plasmonic nanoparticles into perovskite solar cells can greatly improve the cell performance. Our key findings are:

-

Broadband Optical Enhancement: The ellipsoid TiN nanoparticles excite multiple plasmonic resonances that enhance light absorption across a wide spectral range (400–1200 nm), maintaining the average absorptance above 0.9.

-

Improved Carrier Generation and Collection: The optical enhancement results in a higher optical generation profile, when imported into SCAPS, yields a great increase in short circuit current density (Jsc) from 25.99 mA/cm² to 46.84 mA/cm².

-

Improved Power Conversion Efficiency: The power conversion efficiency improves from 18.2 % in the vanilla cell to 31.8 % in the plasmonic device, primarily because of the increase in Jsc.

-

Parametric analysis: A parameter sweep analysis indicated that the nanoparticle geometrical shape, dimensions, and lattice array can affect the optical and hence the electrical performance, with an optimal configuration that maximizes the absorption across the solar spectrum and hence higher generation rates and improved device conversion efficiency.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Wei Guo, K. Green nanotechnology of trends in future energy. Recent. Pat. Nanotechnol. 5, 76–88 (2011).

Green, M. A. et al. Solar cell efficiency tables (Version 60). Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl. 30, 687–701 (2022).

Best Research-Cell Efficiency Chart | Photovoltaic. Research | NREL. https://www2.nrel.gov/pv/cell-efficiency

Batool, R. & Mahmood, T. A comparative study of cubic Methylammonium lead iodide (CH3NH3PbI3) perovskite by using density functional theory. Mater. Today Commun. 35, 105814 (2023).

Stranks, S. D. et al. Electron-hole diffusion lengths exceeding 1 micrometer in an organometal trihalide perovskite absorber. Science 342, 341–344 (2013).

Jena, A. K., Kulkarni, A. & Miyasaka, T. Halide perovskite photovoltaics: Background, Status, and future prospects. Chem. Rev. 119, 3036–3103 (2019).

Zeenelabden, H. H., Elseman, A. M., El-Aasser, M. A., Gad, N. & Rashad, M. M. Observation on structural and optical features of new nanostructured lead-free Methylammonium zinc or Cobalt iodide perovskites for solar cells applications. SN Appl. Sci. 5, 1–11 (2023).

Roknuzzaman, M. et al. Insight into lead-free organic-inorganic hybrid perovskites for photovoltaics and optoelectronics: A first-principles study. Org. Electron. 59, 99–106 (2018).

Chen, J., Zhou, S., Jin, S., Li, H. & Zhai, T. Crystal organometal halide perovskites with promising optoelectronic applications. J. Mater. Chem. C Mater. 4, 11–27 (2015).

Roknuzzaman, M. et al. Electronic and optical properties of lead-free hybrid double perovskites for photovoltaic and optoelectronic applications. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–7 (2019).

Abd Elsamad, A. E., Gad, N., El-Aasser, M. & Elseman, A. M. Simulation study of Zinc/cobalt doped Methyl ammonium lead iodide for solar cells. Egypt. J. Pure Appl. Sci. 61, 19–27 (2023).

Sery, A. A. et al. Toward high-performance carbon-based perovskite solar cells. Sol. Energy. 287, 113261 (2025).

Krogstrup, P. et al. Single nanowire solar cells beyond the Shockley-Queisser limit.

Wang, C., Wang, X., Luo, B., Shi, X. & Shen, X. Plasmonics Meets perovskite photovoltaics: innovations and challenges in boosting efficiency. Molecules 2024. 29, 5091 (2024).

Dong, H. et al. Plasmonic enhancement for high efficient and stable perovskite solar cells by employing ‘hot spots’ Au nanobipyramids. Org. Electron. 60, 1–8 (2018).

Fu, N. et al. Panchromatic thin perovskite solar cells with broadband plasmonic absorption enhancement and efficient light scattering management by Au@Ag core-shell nanocuboids. Nano Energy. 41, 654–664 (2017).

Mohammadi, M., hosein, Eskandari, M. & Fathi, D. Effects of the location and size of plasmonic nanoparticles (Ag and Au) in improving the optical absorption and efficiency of perovskite solar cells. J. Alloys Compd. 877, 160177 (2021).

Enrichi, F., Quandt, A. & Righini, G. C. Plasmonic enhanced solar cells: summary of possible strategies and recent results. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 82, 2433–2439 (2018).

Green, M. A. & Pillai, S. Harnessing plasmonics for solar cells. Nat. Photonics. 6, 130–132 (2012).

Carretero-Palacios, S., Jiménez-Solano, A. & Míguez, H. Plasmonic nanoparticles as Light-Harvesting enhancers in perovskite solar cells: A user’s guide. ACS Energy Lett. 1, 323–331 (2016).

Shukla, S. & Arora, P. Aluminum as a competitive plasmonic material for the entire electromagnetic spectrum: A review. Results Opt. 18, 100760 (2025).

Raether, H., Hohler, G. & Niekisch, E. A. Surface plasmons on smooth and rough surfaces and on gratings. Springer Tracts Mod. Phys. 111, 136 (1988).

Chan, K. et al. Plasmonics in organic and perovskite solar cells: optical and electrical effects. Adv. Opt. Mater. 5, 1600698 (2017).

Hajjiah, A., Kandas, I. & Shehata, N. Efficiency enhancement of perovskite solar cells with plasmonic nanoparticles: A simulation study. Mater. 2018. 11, Page 1626 (11), 1626 (2018).

Maier, S. A. & Plasmonics Fundamentals and applications. Plasmonics: Fundamentals Appl. 1–223 https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-37825-1/COVER (2007).

Catchpole, K. et al. Plasmonic solar cells. Optics Express, 16(16), 21793–21800 (2008).

Pillai, S. & Green, M. A. Plasmonics for photovoltaic applications. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 94, 1481–1486 (2010).

Selmy, A. E., Soliman, M. & Allam, N. K. Refractory plasmonics boost the performance of thin-film solar cells. Emergent Mater. 1, 185–191 (2018).

Qin, F. et al. Ultra-broadband and wide-angle perfect solar absorber based on TiN nanodisk and Ti thin film structure. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 211, 110535 (2020).

Liu, Z., Liu, G., Huang, Z., Liu, X. & Fu, G. Ultra-broadband perfect solar absorber by an ultra-thin refractory titanium nitride meta-surface. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 179, 346–352 (2018).

Wang, B. et al. Broadband refractory plasmonic absorber without refractory metals for solar energy conversion. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 54, 094001 (2020).

Link, S. & El-Sayed, M. A. Spectral properties and relaxation dynamics of surface plasmon electronic oscillations in gold and silver nanodots and nanorods. J. Phys. Chem. B. 103, 8410–8426 (1999).

Sanad, S. et al. Broadband PM6Y6 coreshell hybrid composites for photocurrent improvement and light trapping. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–12 (2024).

Yu, P. et al. Ultra-wideband solar absorber based on refractory titanium metal. Renew. Energy. 158, 227–235 (2020).

Marcelis, E. J., ten Elshof, J. E. & Morales-Masis, M. Titanium dioxide: A versatile Earth-Abundant optical material for photovoltaics. Adv. Opt. Mater. 12, 2401423 (2024).

Su, J. et al. Based on ultrathin PEDOT: PSS/c-Ge solar cells design and their photoelectric performance. Coat. 2021. 11, Page 748 (11), 748 (2021).

Kumar, A. et al. Simulation of perovskite solar cell employing ZnO as electron transport layer (ETL) for improved efficiency. Mater. Today Proc. 46, 1684–1687 (2021).

Zhukovsky, S. V. et al. Experimental Demonstration of Effective Medium Approximation Breakdown in Deeply Subwavelength All-Dielectric Multilayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115 (17), 177402 (2015).

Phillips, L. J. et al. Dispersion relation data for Methylammonium lead Triiodide perovskite deposited on a (100) silicon wafer using a two-step vapour-phase reaction process. Data Brief. 5, 926–928 (2015).

Chen, C. W. et al. Optical properties of organometal halide perovskite thin films and general device structure design rules for perovskite single and tandem solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. Mater. 3, 9152–9159 (2015).

Valour, A. et al. Optical, electrical and mechanical properties of TiN thin film obtained from a TiO2 sol-gel coating and rapid thermal nitridation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 413, 127089 (2021).

Eshaghi, A. & Graeli, A. Optical and electrical properties of indium Tin oxide (ITO) nanostructured thin films deposited on polycarbonate substrates ‘thickness effect’. Optik (Stuttg). 125, 1478–1481 (2014).

Palik, E. D. Palik, E. D. Handbook of Optical Constants of Solids Vol. 3 (Academic Press,). vol. 1–5 (1998)..

Qin, Y. et al. Triple plasmon-induced transparency and dynamically tunable electro-optics switch based on a multilayer patterned graphene metamaterial. JOSA A. 39 (3), 377–382 (2022). 39, 377-382.

Burgelman, M., Decock, K., Niemegeers, A., Verschraegen, J. & Degrave, S. SCAPS Manual. Elis-Ugent, December. - References - Scientific Research Publishing. (2019). https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=2713415

He, Y., Xu, L., Yang, C., Guo, X. & Li, S. Design and numerical investigation of a Lead-Free inorganic layered double perovskite Cs4CuSb2Cl12 nanocrystal solar cell by SCAPS-1D. Nanomaterials 2021. 11, Page 2321 (11), 2321 (2021).

Burgelman, M., Nollet, P. & Degrave, S. Modelling polycrystalline semiconductor solar cells. Thin Solid Films. 361–362, 527–532 (2000).

Noorasid, N. S., Arith, F., Mustafa, A. N. et al. Improved performance of lead-free Perovskite solar cell incorporated with TiO2 ETL and CuI HTL using SCAPs. Appl. Phys. A 129, 132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-022-06356-5 (2023).

Hossain, M. K. et al. An extensive study on multiple ETL and HTL layers to design and simulation of high-performance lead-free CsSnCl3-based perovskite solar cells. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–24 (2023).

Hosseini, S. R. et al. Investigating the effect of non-ideal conditions on the performance of a planar CH3NH3PbI3-based perovskite solar cell through SCAPS-1D simulation. Heliyon. 8, e11471 (2022).

Rahman, M. B., Noor-E-Ashrafi, N., Miah, M. H., Khandaker, M. U. & Islam, M. A. Selection of a compatible electron transport layer and hole transport layer for the mixed perovskite FA0.85Cs0.15Pb (I0.85Br0.15)3, towards achieving novel structure and high-efficiency perovskite solar cells: a detailed numerical study by SCAPS-1D. RSC Adv. 13, 17130–17142 (2023).

Popov, A. A. et al. Laser- synthesized TiN nanoparticles as promising plasmonic alternative for biomedical applications. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–11 (2019).

Huo, D. et al. Broadband perfect absorber based on TiN-Nanocone metasurface. Nanomaterials 2018. 8, 485 (2018).

Chang, C. C. et al. Broadband titanium nitride disordered metasurface absorbers. Optics Express, 29(26), 42813–42826 (2021).

Akhtary, N. & Zubair, A. Light trapping using a dimer of spherical nanoparticles based on titanium nitride for plasmonic solar cells. Optical Materials Express, 13(10), 2759–2774 (2023).

Luo, Q. et al. Plasmonic effects of metallic nanoparticles on enhancing performance of perovskite solar cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 9, 34821–34832 (2017).

Ivriq, S. B., Mohammadi, M. H. & Davidsen, R. S. Enhancing photovoltaic efficiency in Half-Tandem MAPbI3/ MASnI3 perovskite solar cells with triple core-shell plasmonic nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 15, 1–22 (2025).

Omrani, M., Keshavarzi, R., Abdi-Jalebi, M. & Gao, P. Impacts of plasmonic nanoparticles incorporation and interface energy alignment for highly efficient carbon-based perovskite solar cells. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-09284-9 (123AD).

Xie, H. et al. Enhancing photovoltaic performance of carbon-based perovskite solar cells by introducing plasmonic Au NPs. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 146, 114509 (2023).

Rubtsov, S. et al. Plasmon-Enhanced perovskite solar cells based on Inkjet-Printed Au nanoparticles embedded into TiO2 microdot arrays. Nanomaterials 13, 2675 (2023).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. N. E. was primarily responsible for conceptualizing the research project, developing the methodology, conducting the analysis, drafting the original manuscript, and the finalization of this work. N. G. contributed to the project by assisting with conceptualization, validating the research outcomes, reviewing the manuscript, and providing supervision. M. E. modified, reviewed the manuscript, and provided supervision. All Authors participated in writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

El-Mallah, M.N., El-Aasser, M. & Gad, N. Performance enhancement of perovskite solar cells through plasmonic titanium nitride nanoparticles. Sci Rep 16, 7182 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37468-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37468-0