Abstract

With the rapid development of sustainable materials and additive manufacturing technologies, glass fiber-reinforced recycled polypropylene (GF/RPP) has shown enormous potential for application in fused deposition modeling (FDM). However, the mechanical performance of GF/RPP parts is significantly affected by the FDM process parameters, and multi-objective parameter optimization remains a critical challenge. To address this, a novel multi-attribute decision-making (MADM) framework based on the interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy weighted power Heronian mean operator and Combined Compromise Solution (IVTSFWPHM-CoCoSo) is proposed to optimize FDM process parameters. The framework employs the IVTSFWPHM operator to handle experimental uncertainty, capture interactions among multiple mechanical properties, and reduce the influence of extreme values. The improved entropy weight and criteria importance through intercriteria correlation (IEW-CRITIC) method are used to determine weights. Finally, CoCoSo is applied to reliably rank the parameter combinations. The results show that a printing temperature of 240 °C, a layer thickness of 0.3 mm, and an infill density of 60% achieve the best overall mechanical properties across different raster angles, improving performance by approximately 10.7%. The effectiveness of the proposed method is further validated through comparison with existing methods and scanning electron microscopy analysis. This study provides a practical reference for complex decision-making in the FDM printing of recycled composites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to the increasing accumulation of waste textiles, especially from widespread use of medical protective equipment like disposable masks, meltblown fabrics have become a major solid waste source1,2. With the growing emphasis on sustainable manufacturing, the high-value reutilization of waste meltblown fabrics has emerged as a significant research focus3. Meltblown fabrics are primarily composed of polypropylene fibers, which exhibit good plasticity, thermal stability, and mechanical performance, providing strong potential for reprocessing. Through processes such as hot-melt treatment, cleaning, and re-extrusion, waste meltblown materials can be regenerated into recycled polypropylene (RPP), which can be further applied in the field of additive manufacturing (AM)4,5.

However, RPP materials have problems such as weak interlayer bonding and poor molding stability during three-dimensional (3D) printing, which make it difficult to meet the basic requirements of mechanical properties for engineering structural parts. Among various reinforcement strategies, glass fiber (GF) is widely utilized to enhance polypropylene-based materials due to its high strength, good toughness, and low cost. GF-reinforced polypropylene composites are increasingly applied in automotive interiors, construction works, industrial packaging, and low-cost functional structural components. Current studies commonly utilize screw extrusion melt blending to incorporate GF into the RPP matrix, sometimes with compatibilizers to improve interfacial adhesion. A GF content of around 30 wt% is typically adopted to achieve a balance between reinforcement effectiveness, processability, and material cost6,7.

3D printing technology, as a new AM technology that integrates computational modeling, mechanical control, and material engineering, has developed rapidly in the manufacturing field recently8. Selective laser sintering (SLS), stereolithography (SLA), and fused deposition modeling (FDM) are currently popular 3D printing methods9,10. Due to its low equipment cost, ease of usage, and robust material adaptability, the FDM technique has emerged as one of the most popular rapid prototyping technologies among them11. This process works with a wide range of thermoplastics, including polylactic acid (PLA), acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene (ABS), polypropylene (PP), and polyamide (PA). The application of glass fiber reinforced recycled polypropylene (GF/RPP) composites to FDM technology not only broadens the application of sustainable materials in AM but also provides a new research direction for the optimization of their mechanical performance12.

The 3D printing performance of GF/RPP composites is heavily reliant on the proper selection and adjustment of process parameters in the FDM process. Key parameters such as printing temperature, layer thickness, infill density, and raster angle considerably influence the print quality and interlayer adhesion, consequently affecting the mechanical performance of the final printed parts. However, because these parameters interact and may improve one mechanical property at the expense of another, it is crucial to determine a parameter combination that is both optimal and balanced. Scholars have proposed various methods for optimizing FDM process parameters, including the Taguchi method13, genetic algorithm (GA)14, gray relational analysis (GRA)15, artificial neural network (ANN)16, and response surface methodology (RSM)17. Although these methods can reveal the response relationship between parameters and performance to some extent, they typically do not take into account the coordinated optimization of multiple performance indicators. Therefore, they are unable to capture the trade-offs among conflicting objectives or provide a comprehensive evaluation of the overall mechanical performance of the parts18,19,20.

Multi-attribute decision-making (MADM) has gradually attracted attention as an effective tool for dealing with multi-objective conflicts and uncertainty problems. It has found widespread application in engineering, economics, management, the military, and other sectors21,22,23. Zadeh24 first proposed the concepts of fuzzy sets and fuzzy logic to evaluate the uncertainty in decision-making problems. Subsequently, scholars have proposed extended forms such as intuitionistic fuzzy sets (IFS), interval-valued intuitionistic fuzzy sets (IVIFS), Pythagorean fuzzy sets (PyFS) and picture fuzzy sets (PFS)25,26,27,28. The spherical fuzzy set (SFS) and the T-spherical fuzzy set (TSFS) were proposed by Mahmood et al.29 in 2018. This model incorporates a neutrality degree derived from membership and non-membership degrees, providing more comprehensive representation of uncertainty. Ullah et al.30 then developed the interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy set (IVTSFS), which effectively enhanced the expression ability of the model in dealing with uncertainty and imprecise data by introducing the expression of interval values. Xie et al.31 proposed a MADM method for selecting 3D printing composite materials in harsh environments, which is based on probability interval-value hesitant fuzzy sets. In FDM-printed composites, mechanical responses often exhibit inherent uncertainty, hesitancy, and instability due to fluctuations in material properties and process conditions. Compared to classical fuzzy sets such as IFS and PyFS, IVTSFS can describe each experimental result using membership, non-membership, and neutrality degrees, providing a wider range of fuzzy representations and greater flexibility. Figure 1 shows the comparison of decision spaces among different fuzzy sets.

Research on aggregation operators and decision models has provided rich and effective tools for MADM. Yager32 proposed the Power Average (PA) operator, laying the theoretical foundation for MADM. Liu et al.33 successfully addressed MADM problems with complex preference structures using the Heronian Mean (HM) operator in contexts characterized by intuitionistic uncertain language variables. Qin et al.34 introduced methods for determining optimal build directions in 3D printing using the fuzzy weighted power partitioned Muirhead mean (FWPPMM) operator and the fuzzy weighted power prioritized average (FWPPA) operator for MADM. In recent years, MADM models have also been increasingly applied to the optimization of FDM process parameters, including the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS), Preference Selection Index (PSI), and Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)35. Chohan et al.36 employed a hybrid Taguchi-TOPSIS approach to improve the surface quality of ABS parts, demonstrating the suitability of TOPSIS for FDM parameter selection. Begic-Hajdarevic et al.37 developed an MADM method based on the PSI and TOPSIS for optimizing FDM process parameters for PLA parts. Xie et al.38 proposed a behavioral three-way decision model based on interval-valued triangular fuzzy sets to guide the selection of 3D printing composite materials. The Combined Compromise Solution (CoCoSo) is an emerging MADM method that has attracted considerable attention from researchers39. This method integrates multiple evaluation strategies and aggregation mechanisms, enabling balanced ranking by combining the weighted utilities of attributes with the performance scores of alternatives for complex decision-making problems. Compared to traditional methods such as TOPSIS, CoCoSo enhances discrimination, reduces ranking reversals, and maintains robustness when handling correlated or conflicting attributes, making it suitable for multi-objective optimization of FDM process parameters. Mohammed et al.40 applied a hybrid Taguchi-CoCoSo-machine learning method to minimize both surface roughness and printing time of 3D-printed aramid fiber-reinforced polyamide parts.

Although existing methods have achieved progress in parameter optimization, they still face limitations: (1) Most existing studies on FDM printing parameter optimization focus primarily on single-objective optimization or evaluate mechanical properties separately, which fails to provide a unified assessment of overall mechanical performance. (2) Traditional decision-making methods or simple operators usually assume that attributes are independent of each other, but they ignore the interactions between them and are easily affected by extreme values. (3) Existing methods often rely on either subjective or objective weighting methods without combining the advantages of both, which limits the stability and reliability of evaluation results. (4) Current methods generally do not exploit the complementary strengths of advanced aggregation operators and decision-making models, limiting their effectiveness in optimizing FDM printing parameters for GF/RPP composites. To address the above issues, this paper proposes a MADM framework based on the interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy weighted power Heronian mean (IVTSFWPHM)-CoCoSo method. The framework integrates the IVTSFWPHM operator for fuzzy information aggregation, the improved entropy weight and criteria importance through the intercriteria correlation (IEW-CRITIC) method for decision set and attribute set weight calculation, and the CoCoSo method for final ranking. The proposed method is applied to the optimization of FDM printing parameters for GF/RPP composites, providing a systematic decision-making method for multi-objective performance evaluation.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

-

This study proposes a novel IVTSFS-based MADM framework for optimizing the FDM process parameters of GF/RPP composites, simultaneously considering tensile strength, tensile modulus, and elongation at break. The framework provides a systematic decision-support tool for sustainable composite manufacturing and addresses the limitations of existing optimization methods.

-

A novel IVTSFWPHM aggregation operator is developed, which simultaneously considers attribute interdependence and reduces the influence of extreme values. It addresses the methodological gap in the construction of PHM operators within IVTSFS environments and further extends the applicability of fuzzy decision theory to complex multi-objective decision-making problems.

-

A hybrid weighting strategy combining IEW and CRITIC is introduced, allowing both subjective preference information and objective data characteristics to be incorporated into the decision-making process, thereby achieving more rational and reliable criterion weight determination.

-

By integrating the IVTSFWPHM operator with the CoCoSo decision model, a comprehensive and stable ranking mechanism under uncertainty is achieved. The proposed IVTSFWPHM-CoCoSo framework effectively synthesizes multiple correlated and partially conflicting mechanical properties, providing stable and discriminative optimization results.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Sect. 2 introduces the procedures for sample fabrication, the design scheme of FDM process parameters and the data collection process for mechanical properties; Sect. 3 introduces IVTSFS and related basic theories; Sect. 4 systematically describes the construction process of the IVTSFPHM operator and IVTSFWPHM operator; Sect. 5 proposes a complete IVTSFWPHM-CoCoSo decision framework; Sect. 6 applies the proposed method to FDM experimental data, analyzes the evaluation scores and ranking results of each alternative, and performs comparative analysis with existing methods; Sect. 7 concludes the study by summarizing the main findings.

Experimental materials and performance evaluation

This section introduces the preparation process of GF/RPP composite materials, 3D printing parameter settings, the design of the parameter combination experimental scheme, and the collection process of mechanical property test data.

Material and thermal studies

The RPP used in this study was sourced from waste meltblown fabric and processed into granules through steps including hot melt pressing, impurity removal, and granulation. The resulting RPP granules exhibited an average particle size of approximately 1.5 mm and were supplied by Sikan 3D New Material Technology, China. To improve the mechanical performance of the RPP, glass fibers having an average length of 165 μm, a diameter of 9 μm, a density of 2.2 g/cm³, and a tensile strength of 2 GPa were incorporated as the reinforcing phase. They were incorporated uniformly into the RPP matrix at a weight ratio of 30%. GF/RPP composite filaments with a diameter of 1.75 ± 0.05 mm were made using a single-screw extruder and dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C for 6 h. The GF/RPP composite showed a density of 1.12 g/cm³ and a melting temperature of 146 °C, making it suitable for melt extrusion and FDM processing. Figure 2(a) illustrates the preparation process of GF/RPP composite FDM filament. Cross-sectional analysis based on scanning electron microscopy (SEM) shows that the filament retained a near-circular geometry with a roundness value of 0.77, indicating stable extrusion quality, as illustrated in Fig. 2(b).

The thermal behavior of GF/RPP filaments was characterized by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) using a simultaneous thermal analysis (STA 449F5, NETZSCH, Germany) and by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) using a differential scanning calorimeter (DSC 204F1 Phoenix, NETZSCH, Germany). To ensure precise measurements, 9.89 mg of the sample was heated in an alumina crucible from 30 °C to 800 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min under a protective nitrogen atmosphere. As shown in Fig. 3(a), the TGA curve indicates that the sample mass remains nearly constant up to approximately 330 °C, indicating good thermal stability during the initial heating stage, followed by significant thermal degradation above 400 °C. The DSC curve of the GF/RPP filaments, as shown in Fig. 3(b), exhibits an endothermic peak corresponding to the melting process. The onset temperature was observed at 121.08 °C, with the peak temperature at 146.45 °C and the end temperature at 179.91 °C. Based on these thermal analyses, the FDM printing temperature was chosen below the onset of significant thermal degradation to ensure thermal stability of the material during printing.

Process parameter design and experimental scheme

The sample printing was carried out using the Bambu Lab A1 model FDM 3D printing equipment, as shown in Fig. 4. To evaluate the impact of FDM key parameters on the mechanical properties of GF/RPP parts, different raster angles (0°, 45°, 90°) were chosen as environmental variables, with printing temperature (T), layer thickness (L), and infill density (D) as three major variable factors. Three levels were set for each factor, as shown in Table 1. This study used the Taguchi L9 (33) orthogonal array to optimize FDM process parameters for GF/RPP composites. The Taguchi method is a widely used process optimization methodology for systematically assessing the impact of key printing factors on the mechanical properties of composite materials. This method not only enables effective parameter optimization but also significantly reduces the number of experiments. Therefore, the Taguchi L9 provides a balanced trade-off between experimental efficiency and statistical interpretability, making it appropriate for this study. Among them, the printing temperature determines the molten state and interlayer bonding, the layer thickness affects the forming accuracy and interlayer bonding area, and the infill density affects the internal density and strength. In addition, the raster angle determines the orientation of deposited filaments, thereby affecting load-bearing direction, stress transfer efficiency, and the anisotropic mechanical behavior of the composite.

Based on the Taguchi L9 orthogonal design method, nine parameter combinations were established to conduct experiments, as shown in Table 2. For every combination, tests were conducted on tensile strength (TS), tensile modulus (E), and elongation at break (EL). Every mechanical test was carried out three times, and the average results served as inputs for the MADM analysis that followed. To maintain consistency across all trials, the printing speed was set at 50 mm/s and the nozzle diameter was 0.4 mm. A linear infill pattern was adopted, using a line width of 0.45 mm. The interlayer bonding settings remained at default values, support structures were disabled, and the build plate temperature was maintained at 60 °C.

Mechanical testing and evaluation index setting

Tensile properties

Tensile properties were selected as the primary evaluation metrics for mechanical performance. The tensile specimen was constructed using SolidWorks software and printed according to the ASTM D638 standard, with dimensions of 115 mm × 19 mm × 3.2 mm and a gauge length of 33 mm, as seen in Fig. 5. Tensile tests were carried out with a universal testing machine AGS-X (Shimadzu Corporation of Japan) at a loading speed of 5 mm/min, as seen in Fig. 6. The mechanical performance results (TS, E, EL) of the GF/RPP printed specimens corresponding to the nine parameter combinations are shown in Fig. 7. These three properties serve as representative indicators to comprehensively evaluate the mechanical properties of GF/RPP parts from the perspectives of strength, rigidity, and ductility. The experimental results were used to construct a 9 × 3 decision matrix, in which all performance indicators are benefit-type attributes, meaning that higher values indicate better performance.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The microstructure and fracture morphology of the GF/RPP samples were examined under a field emission scanning electron microscope (GeminiSEM 500, ZEISS, Germany). Before testing, a thin layer of gold was sputter-coated onto the sample surfaces to improve electrical conductivity and image quality. Based on the material characteristics and captured details, a magnification level of 30–900 was selected for the experiment in order to capture tensile fracture morphology and faults.

Preliminaries

This section introduces the basic concepts of TSFS and IVTSFS, defines their operation rules, distance metrics, scoring functions, accuracy functions, and simultaneously establishes the mathematical model of the PA and HM operators.

T-spherical fuzzy set (TSFS)

Definition 1

29. Let X be a non-empty finite set, a T-spherical fuzzy set T can be expressed as:

Where \({\mu _T},{\pi _T},{\nu _T}\) respectively represent the degree of membership, the degree of neutrality, and the degree of non-membership, and satisfy the condition \({\mu _T},{\pi _T},{\nu _T} \in \left[ {0,1} \right]\) and \(0 \leqslant \mu _{T}^{q}({\text{x}})+\pi _{T}^{q}({\text{x}})+\nu _{T}^{q}({\text{x}}) \leqslant 1\). The \({\delta _T}\left( x \right)=\sqrt {1 - \mu _{T}^{q}(x) - \pi _{T}^{q}(x) - \nu _{T}^{q}(x)}\) is the refusal degree of x, \(T=\left( {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\mu _T},{\pi _T},{\nu _T}} \end{array}} \right)\) is called an T-spherical fuzzy set number (TSFSN).

Interval valued T-spherical fuzzy set (IVTSFS)

Definition 2

41. Let X be a non-empty finite set, a IVTSFS can be expressed as:

Where \(\mu \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} x \end{array}} \right)=\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\mu ^L}\left( {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} x \end{array}} \right),{\mu ^R}\left( {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} x \end{array}} \right)} \end{array}} \right]\), \(\pi (x)=\left[ {{\pi ^L}\left( x \right),{\pi ^R}\left( x \right)} \right]\), \(\nu (x)=\left[ {{\nu ^L}(x),{\nu ^R}(x)} \right]\) respectively represent the degree of membership, the degree of neutrality, and the degree of non-membership, and satisfy the condition \(\mu ,\pi ,\nu \in \left[ {0,1} \right]\) and\(0 \leqslant {\left( {{\mu ^R}\left( x \right)} \right)^q}+{\left( {{\pi ^R}\left( x \right)} \right)^q}+{\left( {{\nu ^R}\left( x \right)} \right)^q} \leqslant 1\). The \({\delta _{IV}}\left( x \right)=\left[ {\delta _{{IV}}^{L}\left( x \right),\delta _{{IV}}^{R}\left( x \right)} \right]=\left[ {{{\left( {1 - \left( {{{\left( {{\mu ^R}\left( x \right)} \right)}^q}+{{\left( {{\pi ^R}\left( x \right)} \right)}^q}+{{\left( {{\nu ^R}\left( x \right)} \right)}^q}} \right)} \right)}^{\frac{1}{q}}},{{\left( {1 - \left( {{{\left( {{\mu ^L}\left( x \right)} \right)}^q}+{{\left( {{\pi ^L}\left( x \right)} \right)}^q}+{{\left( {{\nu ^L}\left( x \right)} \right)}^q}} \right)} \right)}^{\frac{1}{q}}}} \right]\) is the refusal degree of x, \({T_{IV}}=(\mu ,\pi ,\nu )=\left( {\left[ {{\mu ^L}\left( x \right),{\mu ^R}\left( x \right)} \right],\left[ {{\pi ^L}\left( x \right),{\pi ^R}\left( x \right)} \right],\left[ {{\nu ^L}\left( x \right),{\nu ^R}\left( x \right)} \right]} \right)\) is called an interval valued T-spherical fuzzy set number (IVTSFN).

Definition 3

42. Let A and B be two IVTSFNs on the domain X, then the basic operation is defined as follows:

Definition 4

42. For any an IVTSFNs, their magnitudes can be compared using the scoring function \(SC\left( {{T_{IV}}} \right)\) and the accuracy function \(AC\left( {{T_{IV}}} \right)\).

Definition 5

29. Let \({T_{I{V_1}}}=({\mu _1},{\pi _1},{v_1})\) and \({T_{I{V_2}}}=({\mu _2},{\pi _2},{v_2})\) are two IVTSFNs, If \(SC\left( {{T_{I{V_1}}}} \right)>SC\left( {{T_{I{V_2}}}} \right)\), then \({T_{I{V_1}}}>{T_{I{V_2}}}\); If \(SC\left( {{T_{I{V_1}}}} \right)<SC\left( {{T_{I{V_2}}}} \right)\), then \({T_{I{V_1}}}<{T_{I{V_2}}}\); If \(SC\left( {{T_{I{V_1}}}} \right)=SC\left( {{T_{I{V_2}}}} \right)\), then (a) If \(AC\left( {{T_{I{V_1}}}} \right)>AC\left( {{T_{I{V_2}}}} \right)\), then\({T_{I{V_1}}}>{T_{I{V_2}}}\); (b) If \(AC\left( {{T_{I{V_1}}}} \right)<AC\left( {{T_{I{V_2}}}} \right)\), then \({T_{I{V_1}}}<{T_{I{V_2}}}\); (c) If \(AC\left( {{T_{I{V_1}}}} \right)=AC\left( {{T_{I{V_2}}}} \right)\), then\({T_{I{V_1}}} \approx {T_{I{V_2}}}\).

Definition 6

29. Let A and B be two IVTSFNs, then the Hamming distance measure between A and B is defined as:

Power average operator (PA)

Definition 7

32. Let \({x_1},{x_2}, \cdots ,{x_n}\) be a group of non-negative numbers, then the PA operator is defined as follows:

Where \(T({x_i})=\sum\limits_{{k=1,k \ne i}}^{n} S up({x_i},{x_k})\), \(Sup{\text{(}}{x_i},{x_k}{\text{)=1}} - d\left( {{x_i},{x_k}} \right)\), \(Sup{\text{(}}{x_i}{\text{,}}{x_k}{\text{)}}\) represents the support degree of xk for xi and satisfy the following conditions: (1) \(Sup\left( {{x_i},{x_k}} \right) \in \left[ {0,1} \right]\); (2) \(Sup\left( {{x_i},{x_k}} \right)=Sup\left( {{x_k},{x_i}} \right)\); (3) if \(\left| {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{x_i} - {x_k}} \end{array}} \right| \leqslant \left| {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{x_m} - {x_n}} \end{array}} \right|\), then \(Sup({x_i},{x_k}) \geqslant Sup({x_m},{x_n})\).

Heronian mean operator (HM)

Definition 8

33. Let \({x_1},{x_2}, \cdots ,{x_n}\) be a group of non-negative numbers, If \(\kappa \geqslant 0,\psi \geqslant 0\) and κ and ψ are not simultaneously 0, then the HM operator is defined as follows:

Power Heronian mean operators in IVTSFS environment

This section constructs the IVTSFPHM operator and the IVTSFWPHM operator and systematically analyzes their mathematical properties, providing theoretical support for the subsequent construction of the MADM framework. Traditional aggregation operators assume attribute independence and are sensitive to extreme values, making them unable to capture interactions among multiple mechanical properties and potentially leading to unstable decision outcomes. The proposed operator combines the PA operator and the HM operator, effectively aggregating multiple attributes while accounting for their interrelationships and reducing the influence of extreme values.

IVTSFPHM operator

Definition 9

Let κ and ψ be two non-negative real numbers that are not simultaneously 0, the \({\alpha _i}=\left( {\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\mu _{iL}},{\mu _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right],\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\pi _{iL}},{\pi _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right],\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\nu _{iL}},{\nu _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right]} \right),i=1,2, \cdots ,n\) represents any IVTSFNs. Based on Definition 2, 7, 8 then the IVTSFPHM operator is defined as follows:

Where \(T({\alpha _i})=\sum\limits_{{j=1,j \ne i}}^{n} S up({\alpha _i},{\alpha _j}),i=1,2, \cdots ,n\), \(Sup{\text{(}}{x_i}{\text{,}}{x_j}{\text{)=1}} - d\left( {{x_i},{x_j}} \right)\), \(Sup({\alpha _i},{\alpha _j})\) represents the support degree of αi for αj.

To simplify the Eq. 12, let \({\lambda _i}=\left( {1+T\left( {{\alpha _i}} \right)} \right)/\sum\limits_{{t=1}}^{n} {\left( {1+T\left( {{\alpha _t}} \right)} \right)}\), we have \({\lambda _i} \geqslant 0,\sum\limits_{{t=1}}^{n} {{\lambda _i}=1}\), then \({\text{IVTSFPH}}{{\text{M}}^{\kappa ,\psi }}\left( {{\alpha _1},{\alpha _2}, \cdots ,{\alpha _n}} \right)={\left( {\frac{2}{{n\left( {n+1} \right)}}\mathop \oplus \limits_{{i=1}}^{n} \mathop \oplus \limits_{{j=1}}^{n} \left( {{{\left( {n{\lambda _i}{\alpha _i}} \right)}^\kappa } \otimes {{\left( {n{\lambda _j}{\alpha _j}} \right)}^\psi }} \right)} \right)^{\frac{1}{{\kappa +\psi }}}}\).

According to Definition 3, we can obtain Theorem 1.

Theorem 1

Let κ and ψ be two non-negative real numbers that are not simultaneously 0, \({\alpha _i}=\left( {\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\mu _{iL}},{\mu _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right],\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\pi _{iL}},{\pi _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right],\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\nu _{iL}},{\nu _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right]} \right),i=1,2, \cdots ,n\) represents any IVTSFNs. The IVTSFPHM aggregation operator processes the result is still IVTSFNs.

Proof

Based on Definition 3.3, 3.4, we can derive:

Based on Definition 3.2, then

Based on Definition 3.1, then

Based on Definition 3.3, then

Based on Definition 3.4, then

To ensure the reliability and robustness of the aggregation process, the theoretical properties of the IVTSFWPHM operator are investigated. The IVTSFPHM operator satisfies idempotency, commutativity, boundedness, and monotonicity, which are key theoretical properties detailed as follows:

Property 1

(Idempotency). Let \({\alpha _i}=\left( {\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\mu _{iL}},{\mu _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right],\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\pi _{iL}},{\pi _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right],\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\nu _{iL}},{\nu _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right]} \right),i=1,2, \cdots ,n\) be a set of IVTSFNs, and the IVTSFPHM operator satisfies idempotency, that is

Proof

Property 2

(Commutativity). Let \({\alpha _i}=\left( {\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\mu _{iL}},{\mu _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right],\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\pi _{iL}},{\pi _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right],\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\nu _{iL}},{\nu _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right]} \right),i=1,2, \cdots ,n\) be a set of IVTSFNs, and \(({\alpha ^{\prime}_1},{\alpha ^{\prime}_2}, \cdots ,{\alpha ^{\prime}_n})\) be any permutation of \(\left( {{\alpha _1},{\alpha _2}, \cdots ,{\alpha _n}} \right)\), that is

Proof

Property 3

(Boundedness). Let \({\alpha _i}=\left( {\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\mu _{iL}},{\mu _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right],\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\pi _{iL}},{\pi _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right],\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\nu _{iL}},{\nu _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right]} \right),i=1,2, \cdots ,n\) be a set of IVTSFNs.

Proof

\({\text{IVTSFPH}}{{\text{M}}^{\kappa ,\psi }}\left( {\alpha _{1}^{ - },\alpha _{2}^{ - }, \ldots ,\alpha _{n}^{ - }} \right) \leqslant {\text{IVTSFPH}}{{\text{M}}^{\kappa ,\psi }}\left( {{\alpha _1},{\alpha _2}, \ldots ,{\alpha _n}} \right) \leqslant {\text{IVTSFPH}}{{\text{M}}^{\kappa ,\psi }}\left( {\alpha _{1}^{+},\alpha _{2}^{+}, \ldots ,\alpha _{n}^{+}} \right)\), According to Property 1, \({\text{IVTSFPH}}{{\text{M}}^{\kappa ,\psi }}\left( {\alpha _{1}^{ - },\alpha _{2}^{ - }, \ldots ,\alpha _{n}^{ - }} \right)={\alpha ^ - }\), \({\text{IVTSFPH}}{{\text{M}}^{\kappa ,\psi }}\left( {\alpha _{1}^{+},\alpha _{2}^{+}, \ldots ,\alpha _{n}^{+}} \right)={\alpha ^+}\), So \({\alpha ^ - } \leqslant {\text{IVTSFPH}}{{\text{M}}^{\kappa ,\psi }}\left( {{\alpha _1},{\alpha _2}, \cdots ,{\alpha _n}} \right) \leqslant {\alpha ^+}\).

Property 4

(Monotonicity). Let \({\alpha _i}=\left( {\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\mu _{iL}},{\mu _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right],\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\pi _{iL}},{\pi _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right],\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\nu _{iL}},{\nu _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right]} \right),i=1,2, \cdots ,n\) and \({\alpha ^{\prime}_i}=\left( {\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{{\mu ^{\prime}}_{iL}},{{\mu ^{\prime}}_{iR}}} \end{array}} \right],\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{{\pi ^{\prime}}_{iL}},{{\pi ^{\prime}}_{iR}}} \end{array}} \right],\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{{\nu ^{\prime}}_{iL}},{{\nu ^{\prime}}_{iR}}} \end{array}} \right]} \right),i=1,2, \cdots ,n\) are two groups of IVTSFNs, if \({\alpha _i} \leqslant {\alpha ^{\prime}_i}\), for all i, then

Proof

\({\alpha _i}=\left( {{\mu _i},{\pi _i},{\nu _i}} \right)\), \({\alpha _i}=\left( {{\mu _i},{\pi _i},{\nu _i}} \right)\),\({\alpha _i} \leqslant {\alpha ^{\prime}_i}\), Since \({\mu _i} \leqslant {\mu ^{\prime}_i}\), \({\mu _j} \leqslant {\mu ^{\prime}_j}\), so \({\mu _i}{\mu _j} \leqslant {\mu ^{\prime}_i}{\mu ^{\prime}_j}\). Furthermore, \(\left( {1 - {{\left( {1 - {{\left( {1 - \mu _i^q} \right)}^{n{\lambda _i}}}} \right)}^\kappa }{{\left( {1 - {{\left( {1 - \mu _j^q} \right)}^{n{\lambda _j}}}} \right)}^\psi }} \right) \geqslant\left( {1 - {{\left( {1 - {{\left( {1 - \mu _i^{'q}} \right)}^{n{\lambda _i}}}} \right)}^\kappa }{{\left( {1 - {{\left( {1 - \mu _j^{'q}} \right)}^{n{\lambda _j}}}} \right)}^\psi }} \right)\), \(\prod\limits_{i = 1,j = i}^n {{{\left( {\left( {1 - {{\left( {1 - {{\left( {1 - \mu _i^q} \right)}^{n{\lambda _i}}}} \right)}^\kappa }{{\left( {1 - {{\left( {1 - \mu _j^q} \right)}^{n{\lambda _j}}}} \right)}^\psi }} \right)} \right)}^{\frac{2}{{n\left( {n + 1} \right)}}}}} \geqslant\prod\limits_{i = 1,j = i}^n {{{\left( {\left( {1 - {{\left( {1 - {{\left( {1 - \mu _i^{'q}} \right)}^{n{\lambda _i}}}} \right)}^\kappa }{{\left( {1 - {{\left( {1 - \mu _j^{'q}} \right)}^{n{\lambda _j}}}} \right)}^\psi }} \right)} \right)}^{\frac{2}{{n\left( {n + 1} \right)}}}}}\), \(\left( {\sqrt[q]{{1 - \prod\limits_{i = 1,j = i}^n {{{\left( {1 - {{\left( {1 - {{\left( {1 - \mu _i^q} \right)}^{n{\lambda _i}}}} \right)}^\kappa }{{\left( {1 - {{\left( {1 - \mu _j^q} \right)}^{n{\lambda _j}}}} \right)}^\psi }} \right)}^{\frac{2}{{n(n + 1)}}}}} }}} \right)^{\frac{1}{{\kappa + \psi }}} \leqslant{\left( {\sqrt[q]{{1 - \prod\limits_{i = 1,j = i}^n {{{\left( {1 - {{\left( {1 - {{\left( {1 - \mu _i^{'q}} \right)}^{n{\lambda _i}}}} \right)}^\kappa }{{\left( {1 - {{\left( {1 - \mu _j^{'q}} \right)}^{n{\lambda _j}}}} \right)}^\psi }} \right)}^{\frac{2}{{n(n + 1)}}}}} }}} \right)^{\frac{1}{{\kappa + \psi }}}}\), Because of \({\mu _i} \leqslant {\mu ^{\prime}_i}\), Similarly \({\pi _i} \leqslant {\pi ^{\prime}_i}\), \({\nu _i} \leqslant {\nu ^{\prime}_i}\), so \({\alpha _i}=\left( {{\mu _i},{\pi _i},{\nu _i}} \right) \leqslant {\alpha ^{\prime}_i}=\left( {{{\mu ^{\prime}}_i},{{\pi ^{\prime}}_i},{{\nu ^{\prime}}_i}} \right)\).

IVTSFWPHM operator

Building upon the IVTSFPHM operator, the proposed IVTSFWPHM operator introduces a weighting mechanism to effectively reflect the relative importance of different attributes. By integrating the PA and HM, it reduces the influence of extreme values and captures the interrelationships among attributes, thereby enhancing the flexibility and accuracy of decision-making.

Definition 10

Let \({\alpha _i}=\left( {\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\mu _{iL}},{\mu _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right],\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\pi _{iL}},{\pi _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right],\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\nu _{iL}},{\nu _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right]} \right),i=1,2, \cdots ,n\) be a set of IVTSFNs, \(\omega ={\left( {{\omega _1},{\omega _2}, \cdots ,{\omega _n}} \right)^T}\) is the weight vector, \({\omega _i} \geqslant 0,\sum\limits_{{i=1}}^{n} {{\omega _i}=1}\), then the IVTSFWPHM operator is defined as follows:

Where \({\lambda _i}=\left( {1+T\left( {{\alpha _i}} \right)} \right)/\sum\limits_{{t=1}}^{n} {\left( {1+T\left( {{\alpha _t}} \right)} \right)}\), \(\sum\limits_{{i=1}}^{n} {{\lambda _i}=1}\), \(T({\alpha _i})=\sum\limits_{{j=1,j \ne i}}^{n} S up({\alpha _i},{\alpha _j}){\text{ ,}}i=1,2, \cdots ,n\), \(Sup({\alpha _i},{\alpha _j})\) represents the support degree of αi for αj.

To simplify the Eq. 27, let \({\vartheta _i}={\lambda _i}{\omega _i}/\sum\limits_{{k=1}}^{n} {{\lambda _k}{\omega _k}}\), we have \({\vartheta _i} \geqslant 0,\) then \({\text{IVTSFWPH}}{{\text{M}}^{\kappa ,\psi }}\left( {{\alpha _1},{\alpha _2}, \cdots ,{\alpha _n}} \right)={\left( {\frac{2}{{n\left( {n+1} \right)}}\mathop \oplus \limits_{{i=1}}^{n} \mathop \oplus \limits_{{j=1}}^{n} \left( {{{\left( {n{\vartheta _i}{\alpha _i}} \right)}^\kappa } \otimes {{\left( {n{\vartheta _j}{\alpha _j}} \right)}^\psi }} \right)} \right)^{\frac{1}{{\kappa +\psi }}}}\).

According to Definition 3, we can obtain Theorem 2.

Theorem 2

Let \({\alpha _i}=\left( {\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\mu _{iL}},{\mu _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right],\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\pi _{iL}},{\pi _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right],\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\nu _{iL}},{\nu _{iR}}} \end{array}} \right]} \right),i=1,2, \cdots ,n\) be a set of IVTSFNs, then the IVTSFWPHM operator is defined as follows:

Proof

This proof is similar to Theorem 1 and will not be elaborated further.

Property 5

(Idempotency, Commutativity, Boundedness, Monotonicity).

Proof

This proof is similar to Property 1–4 and will not be elaborated further.

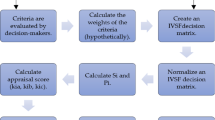

Methodology

This study proposes an IVTSFWPHM-CoCoSo decision-making framework for the multi-objective optimization of FDM process parameters to improve the overall mechanical performance of GF/RPP parts. This framework consists of three stages. Stage 1: The IEW method is first used to determine the weights of different raster angles, after which the corresponding decision matrices are aggregated using the IVTSFWPHM operator to form a comprehensive decision matrix. Stage 2: The CRITIC method is used to objectively calculate the weights of the attribute set by considering both the contrast intensity and the conflict among mechanical properties. Stage 3: The IVTSFWPHM-CoCoSo method is applied to comprehensively evaluate and rank all parameter schemes, thereby identifying the FDM printing parameter combination that yields the optimal overall mechanical performance. Figure 8 shows the individual steps of the decision-making framework, which are as follows:

Stage 1: Decision set aggregation based on the IVTSFWPHM operator.

Step 1.1

For each decision set k, the initial decision matrix is constructed based on i parameter combination schemes and j mechanical performance indicators43. The original IVTSF decision matrix \({A^{\left( k \right)}}\) is then transformed into the standardized decision matrix \({\bar {A}^{\left( k \right)}}\).

Step 1.2

The IEW method is used to determine the decision set weights44. The IEW method combines the AHP, which reflects expert judgment, with the EW method based on data dispersion. This effectively combines subjective and objective information and provides more comprehensive decision set weights. Among them, the expert weights ωH of each raster angle in the AHP method are evenly divided, all of which are 1/3.

Step 1.2.1

Normalized decision matrix.

Calculate the score matrix based on Eqs. 7–8.

Where \(S\left( {y_{{ij}}^{k}} \right)\) represents the score values corresponding to each scheme and attribute under the k th decision matrix, \(S\left( {\bar {y}_{{ij}}^{k}} \right)\) represents the normalized value of the decision matrix.

Step 1.2.2

Calculate the entropy weight of each decision matrix \({E^k}\).

Where \(\rho _{{ij}}^{k}=S\left( {\bar {y}_{{ij}}^{k}} \right)/\sum\limits_{{i=1}}^{m} {\sum\limits_{{j=1}}^{n} {S\left( {\bar {y}_{{ij}}^{k}} \right)} }\) represents the probability matrix.

Step 1.2.3

Calculates the objective weight of the decision set.

Step 1.2.4

The final weights ωI were computed as a linear combination of objective and subjective weights.

Where θ represents the proportion of the IEW method in the combined weights, and satisfies θ\(\in\)[0, 1], this paper sets θ = 0.5.

Step 1.3

According to Definition 6, calculate the support degree.

Step 1.4

Calculate the support matrices \(T(\alpha _{{ij}}^{d})\) based on \(Sup\left( {\alpha _{{ij}}^{d},\alpha _{{ij}}^{l}} \right)\), and then obtain the power weight matrix.

Step 1.5

The IVTSFWPHM operator is utilized to aggregate different decision set information into matrix D’.

Stage 2: The CRITIC method is used to determine the attribute set weights.

The CRITIC method is an effective tool for determining the weights of output responses by analyzing the intrinsic characteristics of experimental data. It simultaneously considers the contrast intensity of each criterion and the degree of conflict among attributes, thereby providing a more comprehensive evaluation of their relative importance in the decision-making process45.

Step 2.1

Normalize the scoring matrix.

Where \(S\left( {{{\bar {y}}_{ij}}} \right)\) represents the normalized value of the decision matrix D’.

Step 2.2

Calculate the correlation coefficient between the attributes.

Where \({\overline {d} _t}=\frac{1}{n}\sum\limits_{{j=1}}^{n} {{d_{jt}}}\) and \({\overline {d} _g}=\frac{1}{n}\sum\limits_{{j=1}}^{n} {{d_{jg}}}\).

Step 2.3

Calculate the standard deviation of the attribute.

Step 2.4

Calculate the CRITIC value for each attribute.

Where \({\sigma _t}\) measures the extent of departure t th attribute.

Step 2.5

Calculates the attribute weights.

Stage 3: CoCoSo method.

The CoCoSo method is employed in this study to perform the final ranking of FDM parameter schemes due to its strong integrative capability and robust ranking performance. The IVTSFWPHM operator aggregates interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy information while simultaneously capturing the interactions among tensile strength, elastic modulus, and elongation at break, ensuring that the aggregated performance score accurately reflects the mutual influence of these mechanical properties. However, IVTSFWPHM does not itself provide a good sorting mechanism. CoCoSo combines compromise-based and aggregation-based decision strategies, offering good discrimination among alternatives and reducing sensitivity to variations in attribute weights. However, it is unable to directly handle complex interval-valued fuzzy information. Therefore, by integrating IVTSFWPHM with CoCoSo, this framework can not only capture the uncertainty of the data and the interrelationships among the attributes but also generate reliable ranking results, making it particularly suitable for the multi-objective optimization of FDM process parameters in GF/RPP composite materials46.

Step 3.1

Calculate the weighted sum measure and weighted product measure of each alternative.

Step 3.2

Calculate the relative importance of each alternative based on the three strategies.

Where \(k_{i}^{a}\) is arithmetic average of Pi and Si, \(k_{i}^{b}\) sum of the relative value of Pi and Si compared to the best value, \(k_{i}^{c}\) is the balanced compromise scores of Pi and Si, σ is coefficient of compromise, which belongs to [0, 1]. In this paper, σ is set to 0.5.

Step 3.3

Calculate the final score of each alternative to determine the parameter combination with the best mechanical performance.

Result analysis and discussions

Effects of FDM process parameters on mechanical properties

To evaluate the influence of FDM key printing parameters (printing temperature, layer thickness, and infill density) on the mechanical performance of GF/RPP composites, linear main effect plots were generated for TS, E, and EL, as shown in Fig. 9.

As shown in Fig. 9(a), the tensile strength has a non-linear relationship with the printing temperature. It reaches its peak at 240 °C and decreases at lower or higher temperatures. This indicates that an appropriate printing temperature can enhance the interlayer bonding, while excessively high temperatures may cause polymer degradation, thereby reducing the strength. The TS also exhibits a nonlinear increase with layer thickness, rising from 15.08 MPa at 0.1 mm to 18.36 MPa at 0.3 mm. This result shows that a larger layer thickness can improve the contact between layers and the load transfer, thereby enhancing the tensile strength. Furthermore, the TS increases with infill density because the reduction of internal voids at higher densities enhances the load-bearing capacity and consequently improves the tensile strength.

As shown in Fig. 9(b), the tensile modulus demonstrates a moderate dependence on printing temperature, peaking at 276.33 MPa at 240 °C and decreasing slightly at both 220 °C and 260 °C. This indicates that an intermediate temperature promotes filament fusion and uniform stress distribution, leading to enhanced stiffness. Furthermore, the tensile modulus increases significantly with layer thickness over the range from 0.1 mm to 0.3 mm. This trend is due to the smaller gaps between layers and the creation of a more continuous load path, which together make the structure stiffer. In terms of infill density, the tensile modulus reaches its maximum at the medium level of 80%, suggesting that an optimal internal structure maximizes load‑transfer efficiency. In contrast, both lower and higher densities result in comparatively less efficient stress transfer, thereby resulting in a slightly reduced modulus.

As shown in Fig. 9(c), the elongation at break is relatively insensitive to printing temperature, with values ranging narrowly from 17.81% to 18.86%. This indicates that filament ductility is largely maintained across the tested temperature range, and moderate variations in temperature do not substantially affect the material’s ability to deform before fracture. In contrast, elongation at break exhibits a significant dependence on layer thickness, decreasing from 24.01% at 0.1 mm to 12.97% at 0.3 mm, suggesting that thinner layers can achieve greater deformation, whereas thicker layers constrain elongation. At an infill density of 80%, elongation at break is slightly lower than at lower or higher densities. This suggests that a medium infill density may slightly limit overall extensibility, whereas both lower and higher infill densities exhibit marginally higher elongation, possibly due to increased structural flexibility or greater void accommodation.

In addition to the individual main effects, the mechanical performance of GF/RPP composites is influenced by the combined action of printing temperature, layer thickness, and infill density. As can be seen from Fig. 9, the beneficial effect of a printing temperature of 240 °C on tensile strength and modulus is more significant at larger layer thicknesses, where appropriate thermal conditions enhance interlayer bonding and load transfer. In contrast, when thinner layers are used, excessive melt fluidity at higher temperatures may increase interfacial defects. The contribution of infill density to mechanical performance is closely associated with the printing temperature and layer thickness. At moderate infill levels, the balance between material continuity and internal stress distribution is improved, whereas the effectiveness of high infill densities depends on adequate filament fusion provided by appropriate temperature and layer thickness. These observations indicate that the mechanical response of GF/RPP parts results from the coordinated influence of multiple processing parameters rather than from any single factor alone.

Although the main-effect analysis reveals the influence of individual FDM parameters, the overall mechanical performance is ultimately determined by their combined effects. Therefore, this paper proposes a novel MADM method to comprehensively evaluate different parameter combinations and identify the optimal overall mechanical performance.

Optimization of the optimal parameter combination based on the MADM method

In FDM printing, key process parameters such as printing temperature, layer thickness, infill density, and raster angle simultaneously affect mechanical properties of the GF/RPP part, including T, E, and EL. Since these performance indicators may exhibit trade-offs, optimizing a single property often fails to achieve overall optimal results. Furthermore, experimental data are subject to measurement errors and inherent material uncertainties, which further complicates decision-making. Therefore, the proposed IVTSFWPHM-CoCoSo method is employed to systematically assess the combined effects of different parameter combinations, account for the relative importance of each mechanical property, and identify the FDM process parameters that optimal overall performance. In this study, different raster angles are considered as the decision set, TS, E, and EL as the attribute set, and nine groups of process parameters as the scheme set. Among them, M = (M1, M2, …, M9) is the scheme set, D = (D1, D2, D3) is the decision set, and C = (C1, C2, C3) is the attribute set, decision set the weight of corresponding information for ω = (ω1, ω2, ω3), attribute set corresponding weight information for the \(\omega ^{\prime}=\left( {{{\omega ^{\prime}}_1},{{\omega ^{\prime}}_2},{{\omega ^{\prime}}_3}} \right)\).

Stage 1: Decision set aggregation based on the IVTSFWPHM operator.

Step 1.1

Create the decision matrix. The initial decision matrices were constructed based on the mechanical properties data shown in Fig. 7 and then transformed into a standardized decision matrix using Eq. 29. The corresponding standardized results are shown in Tables 3, 4 and 5.

Step 1.2

The weights for the decision set are determined using the IEW method. Based on Eqs. 30–34, the entropy values corresponding to the raster angles of 0°, 45°, and 90° were calculated from the decision-making data as 8.1329, 8.5539, and 8.4572, respectively. The weights of the decision sets were then calculated using the IEW method, which yielded 0.3277, 0.3373, and 0.3350. These results reflect the relative contribution of each raster angle to the overall decision-making process.

Step 1.3

Calculate the support degree \(Sup\left( {\alpha _{{ij}}^{d},\alpha _{{ij}}^{l}} \right)\) based on Eq. 35.

\({S_{12}}={S_{21}}=\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\text{0}}{\text{.9129}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9106}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.7330}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.9672}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9141}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.8967}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.9721}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9098}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.8931}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.9577}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.7478}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.6721}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.9909}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.8296}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.8938}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.9643}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.8799}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9954}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.9678}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.8161}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.7893}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.9361}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.8811}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.8613}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.8839}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.7146}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9909}}} \end{array}} \right]\)\({S_{13}}={S_{31}}=\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\text{0}}{\text{.9351}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9841}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9966}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.9178}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9887}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9936}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.9041}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9738}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9938}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.9860}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.8713}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9667}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.9575}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9860}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9813}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.7618}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9486}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9946}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.9527}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9733}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9618}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.9287}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9000}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9742}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.9704}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9111}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9882}}} \end{array}} \right]\)\({S_{23}}={S_{32}}=\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\text{0}}{\text{.9778}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9265}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.7364}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.9506}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9254}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9030}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.9320}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9360}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.8992}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.9717}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.8765}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.6387}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.9665}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.8156}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9125}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.7260}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9313}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9900}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.9849}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.7894}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.7511}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.9926}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9811}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.8871}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.8543}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.8034}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.9973}}} \end{array}} \right]\)

Step 1.4

Calculate the power weight matrix based on Eqs. 36–37.

\({\vartheta _1}=\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\text{0}}{\text{.3292}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3349}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3441}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3327}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3353}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3366}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3338}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3338}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3368}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3333}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3277}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3493}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3339}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3408}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3353}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3449}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3320}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3337}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3315}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3419}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3437}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3287}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3262}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3358}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3391}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3341}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3328}}} \end{array}} \right]\)\({\vartheta _2}=\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\text{0}}{\text{.3341}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3283}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3113}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3365}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3280}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3261}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3370}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3294}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3257}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3317}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3284}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3059}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3349}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3202}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3273}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3404}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3300}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3332}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3351}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3194}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3174}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3361}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3358}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3254}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3253}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3204}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3338}}} \end{array}} \right]\)\({\vartheta _3}=\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\text{0}}{\text{.3367}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3368}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3446}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3308}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3366}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3373}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3292}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3368}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3375}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3349}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3439}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3449}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3312}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3391}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3375}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3147}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3380}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3331}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3334}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3387}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3389}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3352}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3380}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3388}}} \\ {{\text{0}}{\text{.3356}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3454}}}&{{\text{0}}{\text{.3335}}} \end{array}} \right]\)

Step 1.5

According to Eq. 27, the IVTSFWPHM operator is employed to simultaneously aggregate the decision matrices D1, D2, and D3 into an integrated decision matrix D’, as presented in Table 6.

Stage 2: The CRITIC method is used to determine the attribute set weights45.

Step 2.1–2.5

The attribute weights were determined using the CRITIC method, which objectively assigns weights based on the variability and conflict among the mechanical properties within the attribute set. The TS, E, and EL were evaluated according to Eqs. 38–42, and the obtained objective weights were 0.2303, 0.5213, and 0.2484, respectively, reflecting the relative influences of each mechanical property.

Stage 3: CoCoSo method.

Step 3.1

Calculate the weighted sum measure and weighted product measure based on Eqs. 43–44, as shown in Table 7.

Step 3.2

Calculate the three strategies values and final score based on Eqs. 45–48, and conduct a comprehensive ranking to obtain the optimal solution, as shown in Table 8.

The calculated results show that the final ranking of the schemes based on the IVTSFWPHM-CoCoSo method is as follows: M6 > M3 > M4 > M9 > M7 > M5 > M1 > M2 > M8. Among all parameter schemes, M6 obtained the highest comprehensive evaluation score, indicating that the combination of 240 °C printing temperature, 0.3 mm layer thickness, and 60% infill density provides the best overall mechanical performance. To assess the effectiveness of the proposed method, the experimentally measured TS, E, and EL of FDM-printed GF/RPP composites under all parameter combinations were compared. The results show that the overall mechanical performance of the M6 parameter combination is approximately 10.7% higher than that of the other schemes. Based on the main-effect analysis in Sect. 6.1, the superior performance of M6 can be attributed to the synergistic effects of its printing parameters. The intermediate temperature of 240 °C promotes sufficient polymer melting and effective interlayer fusion. The relatively large layer thickness of 0.3 mm increases interlayer contact and reduces the number of internal voids. Furthermore, the moderate 60% infill density provides uniform material distribution and sufficient structural support, thereby reducing stress concentrations and defects.

To further validate the optimization results, M6 was compared with an intermediate scheme (M7) and the worst scheme (M8) through SEM analysis. As shown in Fig. 10(a-c), the tensile fracture surface of the M6 shows that the glass fibers are uniformly distributed in the continuous polymer matrix, with only a small amount of fiber pull-out and a small number of tiny voids. This indicates that the glass fiber and the RPP matrix have a good wetting effect and a strong interlayer bonding force. In contrast, the fracture surfaces of M7 and M8 show more obvious interlayer gaps, irregular fiber exposure, and a higher density of voids, which are consistent with their reduced tensile strength and toughness. These SEM observations indicate that the M6 parameter combination promotes improved filament fusion and load transfer, thereby producing a balanced enhancement of TS, E, and EL. In addition to the fracture surface analysis, cross-sectional SEM observations further reveal the influence of printing parameters on internal porosity and filament morphology. As shown in Figs. 10(d-f), M6 exhibits a dense cross-sectional structure with minimal porosity and clear interlayer fusion. This morphology results from the combined effect of a 240 °C printing temperature, a relatively large 0.3 mm layer thickness, and a moderate 60% infill density, which together enhanced interlayer fusion. In contrast, M7 exhibits clear interlayer voids, likely caused by excessive polymer melt fluidity at the higher printing temperature of 260 °C together with the thinner layer thickness, which weakens interlayer bonding. M8 displays the most obvious defects in its cross-section, including large voids and discontinuous bonding interfaces. This is mainly due to the excessive fluidity of the melt under the same high-temperature conditions, as well as the 0.2 mm layer thickness preventing the polymer chains from diffusing between layers. Although the infill density remains at 60%, the interlayer melting is insufficient, making it difficult for the internal structure to form effective support, significantly weakening the load transmission capacity. These cross-sectional results corroborate the tensile fracture observations and further confirm that the M6 parameter combination produces the most favorable internal structure among the tested schemes.

Sensitivity analysis

Effect of “q” on ranking of alternatives

In the proposed IVTSFWPHM-CoCoSo method, parameter q is the key factor for regulating the structural constraints of the fuzzy sets. It adjusts the relationships between membership, non-membership, and neutrality degrees, influencing the uncertainty range of decision information. To further examine the effect of the parameter q on the decision results, the model scores and corresponding rankings obtained under different q values were analyzed, as shown in Table 9. The results show that while slight ranking variations are observed under different q values, M6 consistently remains the optimal solution, demonstrating the stability of the proposed method within a reasonable parameter range. As shown in Fig. 11, the evaluation scores decrease gradually as q increases, suggesting that q significantly influences model sensitivity and uncertainty representation. Therefore, decision-makers can flexibly select appropriate values for q according to the fault tolerance requirements and risk preferences of practical decision-making scenarios.

Effect of “κ” and “ψ” on comprehensive evaluation scores

Parameters κ and ψ are key adjustment factors in the IVTSFWPHM operator. By adjusting the values of κ and ψ, the contribution and interaction strength among attributes in the aggregation can be flexibly controlled, which in turn influences the final ranking of alternative schemes. Figure 12 illustrates the score variations of nine parameter combination schemes and highlights the influence of parameters κ and ψ on decision-making results.

As shown in Fig. 12, as the parameters κ and ψ gradually increase, the ranking results tend to become more stable, and the score variations exhibit a smoother trend. This indicates that on the basis of fully considering the correlation between the attributes, the decision results are more objective and reasonable, which further verifies the effectiveness of the proposed IVTSFWPHM operator. Three-dimensional surface plots use color gradients to visually represent the dynamic variation in comprehensive evaluation scores under various combinations of parameters κ and ψ, with the color spectrum ranging from blue (lower scores) to red (higher scores). When κ is fixed, increasing ψ leads to a gradual attenuation of the nonlinear variation in the score, particularly in regions with higher κ values. This indicates that an appropriate increase in ψ, corresponding to a higher degree of nonlinear mapping in the IVTSFWPHM operator, enhances the model’s ability to capture the intrinsic structure of the decision data, thereby improving overall decision-making performance. Furthermore, within the range of lower κ values, score variations become more pronounced, indicating that the parameter κ is particularly sensitive to adjustments in this region. Therefore, through the appropriate setting of the parameters κ and ψ, the robustness of the proposed method can be significantly improved.

Effect of “σ” on ranking of alternatives

To further evaluate the stability of the IVTSFWPHM-CoCoSo method, this paper conducted a sensitivity analysis of the parameter σ. The parameter σ\(\in\)[0,1] is the compromise coefficient in CoCoSo that regulates the relative contribution of different aggregation strategies in the final ranking. When σ approaches 0, the decision results tend to place greater emphasis on alternatives with dominant performance in certain criteria. However, when σ approaches 1, the results emphasize the balanced performance of all criteria, effectively reducing the influence of extreme values. To examine the impact of σ on the ranking results, its value was varied from 0 to 1 with an increment of 0.1 while keeping all other parameters unchanged. The resulting score variations and ranking changes of each alternative are illustrated in Fig. 13.

The results show that when the IVTSFWPHM-CoCoSo method’s parameters are appropriately adjusted within the given range, the overall scores and final rankings of all schemes stay mostly the same, with only small changes seen in individual schemes. Among them, the optimal scheme M6 consistently maintains the top rank, while M8 remains the lowest-ranked alternative across all tested schemes. These findings demonstrate that the proposed decision-making framework exhibits strong robustness in parameter variation.

Stability analysis

To evaluate the stability of the proposed methods under varying weight settings, a global weight perturbation analysis is conducted. While ensuring that the sum of all attribute weights remains equal to 1, a random perturbation of ± 2% is simultaneously applied to each attribute weight, generating 100 different weight combinations. For each weight combination, the comprehensive evaluation score of every scheme is recalculated. The resulting normalized scores under these perturbation conditions are plotted as radar charts to visually demonstrate the impact of different weight combinations on the scheme evaluation results, as shown in Fig. 14.

As can be seen in the figure, under 100 sets of weight perturbations, the score distributions of all schemes remain highly concentrated, exhibiting only minor fluctuations. This indicates that the IVTSFWPHM-CoCoSo method is insensitive to variations in attribute weights. Among them, M6 consistently achieves high scores, while M8 persistently exhibits the lowest scores with a narrow fluctuation range, maintaining the last rank across all schemes. These results demonstrate that the proposed method exhibits strong robustness within a reasonable range of weight variations, thereby ensuring the stability and consistency of the decision-making outcomes.

Comparative analysis of methods

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed method, this paper selected a variety of classic decision operators and decision models proposed by existing scholars and conducted a comparative analysis. Specifically include: interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy weighted averaging operator (IVTSFWA)30, interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy weighted geometric operator (IVTSFWG)30, interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy weighted Bonferroni mean operator (IVTSFWBM)42, interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy weighted geometric Bonferroni mean operator (IVTSFWGBM)42, interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy Hamacher weighted averaging operator (IVTSFHWA)47, interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy Hamacher weighted geometric operator (IVTSFHWG)47, interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy Dombi weighted averaging operator (IVTSFDWA)48, interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy Dombi weighted geometric operator (IVTSFDWG)48, T-spherical fuzzy Aczel-Alsina weighted average operator (TSFAAWA)49, T-spherical fuzzy Aczel-Alsina weighted geometric operator (TSFAAWG)49, interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy-TOPSIS (IVTSF-TOPSIS)50, interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy-evaluation based on distance from average solution (IVTSF-EDAS)51, the calculation results are shown in Table 10.

Figure 15 presents a comparison of the ranking results obtained using different MADM methods. The results indicate that the IVTSFWA, IVTSFWG, IVTSFWBM, IVTSFWGBM, IVTSFHWA, IVTSFHWG, and IVTSF-TOPSIS methods consistently identify M6 as the optimal scheme and M8 as the worst scheme. These findings are fully consistent with those obtained using the proposed IVTSFWPHM-CoCoSo method, demonstrating its reliability in identifying the best and worst parameter schemes. However, the aforementioned methods are more sensitive to extreme values, which leads to noticeable fluctuations in their evaluation results. In contrast, the IVTSFWPHM-CoCoSo method introduces the power q and the adjustment parameters κ and ψ, effectively reducing the influence of extreme values during aggregation and thereby enhancing the stability of the ranking outcomes.

As shown in Table 10, the IVTSFDWA and IVTSFDWG methods yield identical final scores for multiple scheme (such as S(M2) = S(M8) = 0.1066), which may cause ranking ambiguity in actual decision-making and reduce the discrimination ability of the methods. This occurs because these methods only consider membership and non-membership while disregarding the neutrality information, thereby failing to capture the full fuzzy characteristics of the alternatives and limiting their applicability. Furthermore, the TSFAAWA, TSFAWG, and IVTSF-EDAS methods treat each mechanical property as an independent attribute, failing to consider the interactions between them, thus making it difficult to fully reflect the comprehensive effect of printing parameters on the overall mechanical performance. In contrast, the IVTSFWPHM-CoCoSo method not only fully incorporates neutrality information but also integrates the IEW-CRITIC two-layer weighting mechanism. This allows the method to more accurately capture the interaction and uncertainty characteristics among the mechanical properties, leading to a more reliable optimization outcome.

Table 11 summarizes the advantages and limitations of the proposed IVTSFWPHM-CoCoSo method compared with the existing methods. Compared with existing methods, the proposed method not only expands the range of fuzzy expressions by introducing IVTSF but also effectively considers the mutual relationship between attributes by combining the PA operator and HM operator, thereby reducing the impact of extreme values on decision results. Furthermore, the existing methods often rely solely on subjective assignment or an equal weight strategy. In contrast, the proposed method integrates the IEW-CRITIC weighting strategy to ensure the rational acquisition of both decision set weights and attribute set weights. The IEW method combines the AHP, which reflects expert judgment, with the EW method based on data dispersion. This effectively integrates subjective and objective information and provides more comprehensive decision set weights. The CRITIC method is based on the contrast intensity and the degree of conflict among attributes, thus enabling the objective determination of attribute set weights based on the intrinsic characteristics of experimental data. By jointly employing IEW and CRITIC, this study establishes a rational and robust weighting mechanism in which subjective expert judgments and objective data characteristics complement each other, thereby enhancing the reliability of the final decision. At the same time, this method combines the advanced IVTSFWPHM operator with the CoCoSo decision model to achieve comprehensive evaluation and ranking of multi-attribute schemes, making the decision results more robust and more in line with practical application needs.

To further validate the proposed IVTSFWPHM-CoCoSo method, a comparison with the traditional Taguchi L9 method was conducted. In the Taguchi method, each printing parameter (temperature, layer thickness, and infill density) is analyzed individually by calculating the signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio for each level, and the parameter combination corresponding to the highest response is recommended. For a larger-the-better performance characteristic, the S/N ratio is calculated as follows:

Where yi is the observed value of the response variable for the i-th experiment, and n is the number of experimental repetitions.

According to Eq. 49, Table 12 summarizes the S/N ratio results of TS, E, and EL for nine experimental schemes under three raster angles. In this table, the optimal scheme for TS is M6, for E it is M3, and for EL it is M1. Scheme M6 exhibits the highest S/N ratio for TS (25.592) and a relatively high value for E (49.562), while its EL S/N (22.234) is slightly below the maximum. However, the Taguchi method evaluates each mechanical property independently and cannot simultaneously account for trade-offs among multiple conflicting objectives, limiting its ability to reflect overall mechanical performance. In contrast, the proposed IVTSFWPHM-CoCoSo method integrates TS, E, and EL through a weighted aggregation framework, enabling a comprehensive evaluation of overall performance. The optimization results consistently identify M6 as the optimal parameter combination across all raster angles, achieving a more balanced improvement in mechanical properties. This comparison demonstrates that, while the Taguchi L9 design efficiently identifies significant factors and determines parameter combinations, the IVTSFWPHM-CoCoSo method is more suitable for multi-objective optimization of FDM process parameters.

Conclusions

This study proposes a novel MADM method for multi-objective optimization of the FDM process parameters to effectively improve the overall mechanical properties of FDM-printed GF/RPP parts. The main conclusions are summarized as follows:

(1) This study applies a MADM framework to the optimization of FDM process parameters for GF/RPP composites, simultaneously considering tensile strength, tensile modulus, and elongation at break. A novel IVTSFWPHM-CoCoSo method is developed to address the limitations of existing optimization methods in this field. The IVTSFWPHM operator integrates the advantages of the power average (PA) and Heronian mean (HM) operators and enhances aggregation robustness by effectively capturing the interactions among multiple mechanical properties. Furthermore, the integration of the IEW-CRITIC method establishes a two-layer weighting mechanism that mitigates subjectivity and improves information utilization, leading to rational weight determination for both the decision and the attribute set. Finally, the combination of the IVTSFWPHM operator with the CoCoSo method improves the stability of multi-attribute ranking, enabling a comprehensive and reliable evaluation of FDM parameter schemes.

(2) Based on the main-effect analyses, printing temperature and layer thickness have the most significant impact on the mechanical performance of GF/RPP composites, while the influence of the infill density is relatively small. A moderate printing temperature combined with a relatively large layer thickness enhances interlayer bonding and load transfer, thereby improving tensile strength and modulus. Therefore, printing temperature and layer thickness should be prioritized during process parameter optimization to achieve the best overall mechanical performance.

(3) The results show that the parameter combination of 240 °C printing temperature, 0.3 mm layer thickness, and 60% infill density achieves the best overall mechanical properties across different raster angles, with an improvement of approximately 10.7% compared with other parameter combinations. Through sensitivity analysis of the key parameters of the IVTSFWPHM operator and the CoCoSo method, the stability of the proposed method in this paper was verified. Through comparison with existing methods and SEM analysis, showing that the optimal scheme (M6) exhibits a denser internal structure, improved interlayer fusion, and fewer defects compared with the intermediate (M7) and worst (M8) schemes. These microstructural characteristics explain the balanced enhancement of the overall mechanical performance, providing strong physical support for the effectiveness of the proposed method.

Although the proposed IVTSFWPHM-CoCoSo method has demonstrated effectiveness in optimizing FDM process parameters for GF/RPP composites, this study has several limitations. The experimental validation was conducted on a single composite material with a limited set of process parameters, which may restrict the general applicability of the results. In addition, the study focused on a constrained range of FDM process parameters, potentially overlooking other influential factors that could affect mechanical performance. Future research should focus on extending the decision-making framework to a wider range of composite materials, exploring a more comprehensive set of process parameters, and considering more functional performance indicators. Furthermore, combining machine learning-based predictive models with the IVTSFWPHM-CoCoSo method could improve the efficiency and accuracy of decision-making in more complex multi-objective optimization scenarios.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Abbreviations

- AM:

-

Additive manufacturing

- 3DP:

-

Three-dimensional printing

- SLS:

-

Selective laser sintering

- SLA:

-

Stereolithography

- FDM:

-

Fused deposition modeling

- PLA:

-

Polylactic acid

- ABS:

-

Acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene

- PP:

-

Polypropylene

- RPP:

-

Recycled polypropylene

- GF/RPP:

-

Glass fiber reinforced recycled polypropylene

- PA:

-

Polyamide

- GA:

-

Genetic algorithm

- GRA:

-

Gray relational analysis

- ANN:

-

Artificial neural network

- RSM:

-

Response surface methodology

- MADM:

-

Multi-attribute decision-making

- IFS:

-

Intuitionistic fuzzy set

- IVIFS:

-

Interval-valued intuitionistic fuzzy set

- PyFS:

-

Pythagorean fuzzy set

- SFS:

-

Spherical fuzzy set

- TSFS:

-

T-spherical fuzzy set

- IVTSFS:

-

Interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy set

- PA:

-

Power average

- HM:

-

Heronian mean

- TOPSIS:

-

Technique for order preference by similarity to ideal solution

- EDAS:

-

Evaluation based on distance from average solution

- CoCoSo:

-

Combined compromise solution

- PSI:

-

Preference selection index

- AHP:

-

Analytic hierarchy process

- SWARA:

-

Step-wise weight assessment ratio analysis

- IEW:

-

Improved entropy weight

- CRITIC:

-

Criteria importance through intercriteria correlation

- FWPPMM:

-

Fuzzy weighted power partitioned Muirhead mean operator

- FWPPA:

-

Fuzzy weighted power prioritized average operator

- IVTSFPHM:

-

Interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy power Heronian mean operator

- IVTSFWPHM:

-

Interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy weighted power Heronian mean operator

- IVTSFWA:

-

Interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy weighted averaging operator

- IVTSFWG:

-

Interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy weighted geometric operator

- IVTSFWBM:

-

Interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy weighted Bonferroni mean operator

- IVTSFWGBM:

-

Interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy weighted geometric Bonferroni mean operator

- IVTSFHWA:

-

Interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy Hamacher weighted averaging operator

- IVTSFHWG:

-

Interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy Hamacher weighted geometric operator

- IVTSFDWA:

-

Interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy Dombi weighted averaging operator

- IVTSFDWG:

-

Interval-valued T-spherical fuzzy Dombi weighted geometric operator

- TSFAAWA:

-

T-spherical fuzzy Aczel-Alsina weighted average operator

- TSFAAWG:

-

T-spherical fuzzy Aczel-Alsina weighted geometric operator

References

Shukla, S., Khan, R., Saxena, A. & Sekar, S. Microplastics from face masks: a potential hazard post Covid-19 pandemic. Chemosphere 302, 134805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.134805 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. Used disposable face masks are significant sources of microplastics to environment. Environ. Pollut. 285, 117485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117485 (2021).

Li, X., Wang, L. & Ding, X. Textile supply chain waste management in China. J. Clean. Prod. 289, 125147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125147 (2021).

Rokbi, M. et al. Effect of processing parameters on tensile properties of recycled polypropylene based composites reinforced with jute fabrics. Int. J. Lightweight Mater. Manuf. 3, 144–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlmm.2019.09.005 (2020).

Pang, A. L., Husin, M. R., Arsad, A. & Ahmadipour, M. Effect of graphene nanoplatelets on structural, morphological, thermal, and electrical properties of recycled polypropylene/polyaniline nanocomposites. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 32, 9574–9583. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-021-05620-3 (2021).

Sakthivel, M., Jenarthanan, M. & Raja, P. Mechanical properties, degradation and flue gas analysis of basalt and glass fiber reinforced recycled polypropylene. Mater. Test. 61, 579–583. https://doi.org/10.3139/120.111358 (2019).

Zhang, M., Sun, S., Liu, J. & Sun, J. Recycling polypropylene from non-woven disposable masks in developing a three-dimensional printing filament. Text. Res. J. 93, 2789–2808. https://doi.org/10.1177/00405175221147722 (2023).