Abstract

Global climate change increases the likelihood of hydrological extremes in rivers such as floods and low flow conditions, with profound consequences on ecology and human wellbeing. To study how water quality parameters including phytoplankton respond to hydrological extremes, we analysed two distinct years with high (2021) and low discharge (2022), in a regulated Central European river and using a multidisciplinary approach: weekly in situ biochemical data, longitudinal profiles, hydrological modelling and remote sensing of chlorophyll. The drought summer 2022 in comparison to the wet and cold summer 2021 was on average characterized by lower discharge (39 vs. 328 m3/s), longer flow time (31.8 vs. 9.9 days), warmer water (24.1 vs. 20.0 °C), lower total nitrogen (TN) (1.6 vs. 3.4 mg/L) and a lower TN/TP ratio (11 vs. 29). An intensive cyanobacterial bloom developed in 2022 (maximum chlorophyll-a 177 µg/L), dominated by the scum-forming genus Microcystis (maximum 4.8 × 108 cells/L). Our findings provide evidence that low flow, combined with other stressors, deteriorate some water quality indicators and promote toxic cyanobacterial blooms in regulated rivers. Ongoing hydrological and climatic changes may increase such risks in rivers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sustaining global freshwater resources in quantity and quality is one of the central aims of the United Nations sustainable development goals1. Rivers are a key element in global water management strategies to combat water crisis. However, rivers fulfill multiple ecosystem services, e.g. drinking water abstraction, irrigation, hydropower generation, inland navigation (transport of goods, recreational boating), disposal of anthropogenic effluents, water supply for industry and energy production, and simultaneously provide a valuable ecological habitat. Rivers are thus exposed to multiple stressors affecting water quantity as well as quality2. While sufficient water quantity is needed for some purposes (e.g. hydropower and inland navigation), water quality is central to others (e.g. drinking water and ecosystem functioning) and thus in turn limits water quantity for specific demands.

In recent years, the frequency and magnitude of extreme hydrological situations in rivers seem to increase on a global scale due to climatic changes3,4. While floods may have devastating effects and pose a direct threat to human life and infrastructure, low water situations often are less present in human perception. For Europe, it is projected that drought and low water situations will happen more frequently, with a longer duration, and expand northwards within this century5,6. Droughts not only limit water quantity in rivers but may have fundamental impacts on water quality and ecosystem functioning7,8, e.g. by the formation of harmful algae blooms. Harmful algae blooms can have potential negative consequences on water quality, biodiversity, human health and ecosystem services. While nutrient management has helped to combat eutrophication and the formation of harmful algae blooms in the past decades with positive effects on water quality and biodiversity in many surface waters, climate change may counteract such developments9.

In the European water framework directive (WFD), water quality is one of the key factors influencing the “ecological status”, which aims to “achieve good status for all rivers, lakes and transitional and coastal waters in the EU”10. According to the WFD, the ecological status in rivers is defined by specific physical, chemical and biological indicators10. Those indicators can be hampered by drought conditions and associated prolonged low discharge phases. For example, droughts are often correlated with warmer water temperature11,12, also limiting physical oxygen solubility7. Low discharge implies less dilution of anthropogenic compounds such as chemical pollutants as well as salts13,14,15. The effect of low discharge on the carbon and nutrient budget is more complex since this also depends on biological variables. However, low discharge under drought conditions was shown to shift total organic carbon (TOC) as well as phosphorus (P) and nitrogen (N) ratios7,16 thereby also influencing the N/P-ratio17.

Important biological indicators for water quality in large rivers are abundance and community composition and thus biodiversity of phytoplankton. Other than in lakes, riverine phytoplankton (also called potamoplankton) living in unidirectional river flow must have growth rates that exceed hydraulic flushing18,19. Low discharge, i.e. low flow velocity and an elongated residence time enables an increased number of replication cycles and thus favours the growth of phytoplankton. High discharge on the other hand can limit phytoplankton biomass because increased flushing increases loss rates, reducing the net growth rate, and is often accompanied by higher turbidity and reduced light availability. Nevertheless, discharge is not the only factor constraining riverine phytoplankton, when flow is suitable, other constraints become more important like nutrient availability, sedimentation, modest inoculum and grazing pressure18,20.

Cyanobacteria, one of the most common harmful algae bloom forming organismic groups, are favoured by low flow due to their slow growth rate compared to other species21,22. Cyanobacterial blooms seem to be becoming more frequent, intense, and persistent worldwide, degrading ecosystems and water quality and posing a health risk due to the production of cyanotoxins23,24,25. River regulation, i.e. damming, may enhance the effects of droughts on phytoplankton growth by further reducing flow velocity and increasing residence times. As such, regulated rivers with reduced flow velocity are more prone to phytoplankton formation and cyanobacterial blooms22,26,27.

This study was conducted on a 240 km stretch of the Moselle river, a large river of the low mountain ranges in Western Europe with an average discharge of approximately 300 m3/s. The Moselle is heavily modified and regulated by several dams to enable ship traffic and generation of hydropower, which reduces its overall flow velocity. As such, the Moselle is a typical example of a highly anthropogenically modified river in temperate, industrialized countries. It expresses pronounced signals of climate change with cyanobacteria blooms regularly occurring since 201728. The two consecutive years of 2021 and 2022 provided conditions similar to an experimental setup: While 2021 was a relatively wet year, it was followed by a year (i.e. 2022) with an intense dry summer period. This natural setting allowed us to study the effects of high and low discharge in a regulated river with little changes in other environmental and anthropogenic conditions such as agricultural use or morphology. We studied the spatio-temporal effects on hydrology, physical conditions, nutrients, and ecology (i.e. primary productivity and phytoplankton community composition) following the hypothesis that extreme weather and subsequent hydrological extremes significantly affect physical, chemical and biological water quality indicators including the abundance and composition of phytoplankton in regulated rivers.

Results

Hydrological conditions in 2021 and 2022

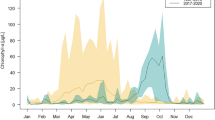

Hydrological conditions in the Moselle in the two years, 2021 and 2022, differed significantly (Fig. 1). While 2021 had wet conditions until mid of July, 2022 was characterized by a long dry period from spring to late summer. At the Moselle gauge Cochem, discharge in summer 2021 was continuously above the mean annual minimum discharge (MAMD – Average of the respective independent minimum discharges from each year in the time period from 1991 until 2022), which was 46.8 m3/s (Fig. 1). In July 2021, a significant flood event occurred with a peak discharge of 2680 m3/s at the Cochem gauge. Flood peaks of this level have a recurrence interval between 5 and 10 years and are more common in winter in the Moselle (Fig. 1). Only for a short time in June and in late September and October 2021 discharge gradually fell below the longterm median.

In contrast, discharge from May till September 2022 was continuously below the median of the reference period and ranged below the 10th percentile throughout July and August. From around mid-July until the beginning of September, the discharge was on average below 40 m3/s and reached minima of approx. 25 m3/s in August. Summer 2022 thus was a pronounced low water period with 60 days below the MAMD of the past 32 years (Fig. S1). This situation was relieved only in September and October, when a number of rainfall events led to a stepwise increase in discharge.

Daily discharge hydrographs of the gauge at Cochem in 2021 (top) and 2022 (bottom) in comparison with discharge distribution during the long-term reference period of the 1991–2022 (date-related minima, maxima and quantiles as decile bands). MAD – mean annual discharge, MAMD – mean annual minimum discharge. The y-axis is shown on a Box–Cox–transformed scale (λ = 0.4).

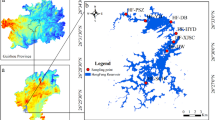

Differences in discharge also affected seasonal flow velocity along the longitudinal gradient of the Moselle in Fig. 2. The calculated flow velocity differed markedly between both years with sections of low flow velocity marked in Fig. 2 in bright-yellow colours and sections of high flow velocity in dark blueish colours. In 2021 several high discharge events occurred from spring until summer, visualized as blue vertical lines in Fig. 2. The most prominent was the above mentioned flood event in mid-July 2021 with maximum velocities of 2.6 m/s, which coincide with weeks of high rainfall (Fig. 3A). Only in the end of August 2021, flow velocity declined and was on average 0.21 m/s along the longitudinal gradient until October. In 2022, the flow velocity was lower and averaged 0.23 m/s from as early as May until October, with pronounced low flow velocities of 0.13 m/s in July and August. This was especially pronounced in the upper section of the Moselle (upstream of river km 200), where velocities had minima of 0.01 m/s. The timing and location of low flow coincided with the increase in chlorophyll along the river as derived from satellite remote sensing in combination with in situ data (compare Fig. 4).

Simulated flow velocity for the time periods April till October of the years 2021 and 2022 along the longitudinal profile of the Moselle from km 274 (Uckange, France) until the river mouth (Koblenz, km 0). Location of dams along the river profile were marked on the second y-axes. Flow velocities over 1.0 m/s were set to 1.0 m/s for better visualization of low flow velocities in summer. The arrow indicates the summer flood in 2021.

In addition, spatial variations in flow velocity are observed between the upstream and downstream segments of the Moselle. Flow velocities are lower upstream of km 195.9 (Trier sluice). Two major tributaries of the Moselle, the rivers Saar (km 200.8) and Sauer (km 205.9) increase the discharge and flow velocity of the Moselle (Fig. 2). The effect of the 12 dams is clearly visible with lower calculated flow before and higher flow velocity right after the dam. During the flood in July 2021, or during winter floods from January to April in both years—as visualized by the uninterrupted dark blue vertical lines in Fig. 2—the weirs may be opened, and the flow velocity remained constant along the river gradient.

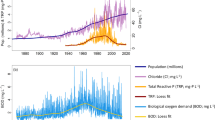

Seasonal variations of hydrological, physico-chemical and biological parameters

Water quality indicators were monitored throughout 2021 and 2022 at the river mouth in Koblenz revealing differences in annual patterns between both years (Fig. 3). To assess differences specifically between both summers, we selected the low-discharge period (< 50 m3/s) in 2022 (6. July – 5. September) and compared that with the same time period in 2021 as reference. The hydrological conditions described above correspond to the weather situations recorded in the two years. The summer 2021 had a comparatively high precipitation, while summer 2022 was drier (Fig. 3A). In addition, global radiation was higher in July and August 2022 than in 2021, with mean weekly sums of 14,846 J/cm2/week compared to only 11,294 J/cm2/week (Fig. 3B). Air temperature during July and August also differed significantly between the two years (p < 0.01, mixed effects model with Sidaks multiple comparisons post test, Table S1), with average values of 17.3 °C in 2021 and 21.5 °C in 2022 (Fig. 3C). The drier and warmer conditions in 2022 resulted in significantly higher average summer water temperatures of 24.1 °C in 2022 compared to 20.0 °C in 2021 (p < 0.0001, Sidak-adjusted; Fig. 3D). Average flow time from the French border to the river mouth (~ 240 km) took more than one month in summer 2022 (31.8 days). This is in contrast to about 9.9 days during summer 2021 (p < 0.05, Sidak-adjusted; Fig. 3F).

Hydrological, biological and physico-chemical characteristics of the years 2021 and 2022 in Koblenz. Weather data (precipitation, global radiation and air temperature) were obtained from the German Weather Service station at Trier-Petrisberg (Station No. 05100, river km 193), discharge data were provided by the Federal Waterways and Shipping Administration (WSV) at Cochem (river km 50.3). Water temperature was monitored continuously at Mehring (average depth 0.36 m; km 173.3). Shown is the weekly average for air and water temperature and the weekly sum for precipitation and global radiation. Average flow velocity and flow time are modelled for the German part of the Moselle and generated in this study. Total phosphorus, total nitrogen and chlorophyll were measured weekly in Koblenz. Samples for Microcystis cell counting were taken biweekly in Koblenz. The period of low discharge (< 50 m3/s) in 2022 (6. July – 5. September) is displayed as dark line at the x-axis.

During the periods of low discharge of < 50 m3/s in 2022 (6. July – 5. September), TN decreased to 0.8 mg/L whereas in 2021 the concentrations were significantly higher with over 2.7 mg/L (p < 0.01, Sidak-adjusted; Fig. 3H). The concentration of total phosphorus (TP) in both summers was similar, but increased to values of 0.44 mg/L in late August 2022, whereas in the respective time period in 2021 concentrations remained below 0.2 mg/L (Fig. 3G). The average ratio of TN/TP was significantly lower in 2022 (11.0) than in 2021 (29.7, p < 0.05, Sidak-adjusted; Fig. S2). The biologically available forms nitrate and soluble reactive phosphorus (SRP) were significantly higher in the reference period in 2021 compared to 2022 (nitrate mean 2.8 mg/L to 0.4 mg/L, p < 0.01, and SRP mean 0.09 mg/L to 0.04 mg/L, p < 0.05; Sidak-adjusted; Fig. S2). In late summer 2022, total chlorophyll increased up to 176.7 µg/L (Fig. 3I), with up to 88% cyanobacteria-chl-a (data not shown). From June 2022 till end of October, the genus Microcystis was the dominant cyanobacterium and reached maxima of 4.8 × 108 cells/L in beginning of September (Fig. 3J). During the Microcystis bloom the organic carbon fractions TOC and DOC (dissolved organic carbon) increased to maximum concentrations of 29 mg/L (TOC) and 15 mg/L (DOC; Fig. S2). The proportion of DOC to TOC was during the period of low discharge on average 69% in 2022. In 2021, chl-a did not increase above 7.3 µg/L in summer and no Microcystis cells were found in the seasonal phytoplankton samples in Koblenz. Likewise, during the summer period 2021, when the chl-a was only on average 3.1 µg/L and the loss on ignition very low with on average 29.9% (corresponding to 2.2 mg/L organic suspended matter), no increase in TOC or DOC was observed (max. 9.8 mg/L for both TOC and DOC). On average, DOC accounted for 88% of TOC during the low discharge period.

Spatial differences along the river gradient

A spatio-temporal picture of chl-a concentrations in the Moselle river from river km 278 in France to its confluence with the Rhine at km 0 throughout the years 2021 and 2022 (April – October) was retrieved by satellite imaging (Fig. 4). The satellite derived data show a higher concentration of chl-a between July and October in 2022 indicated by a bright green and yellow colours, compared to 2021 that was characterized by low chl-a levels as marked by dark blueish colours in Figure 4. A summer phytoplankton bloom in 2022 was indicated by elevated chl-a concentrations starting in June in the upper section (> km 200) as well as in July in the lower section of the Moselle (km 120–0). The bloom seems to intensify in magnitude with up 60 µg/L and more from July till October along the upper river section (> km 200). At the same time, the middle section (km 200–120) of the Moselle showed lower concentrations. In comparison, the chl-a signal in the Moselle in 2021 is lower throughout the year. In mid of July 2021 a narrow band of slightly elevated chl-a values (up to 60 µg/L) stretched along the Moselle from km 250 to 0 (Fig. 4), however this coincides with a flood event with high discharge and high turbidity (mean 512 FNU, 16.07.2021, Cochem, data not shown), which likely disturbed the chlorophyll signal. Apart from that, there was no larger chlorophyll signal in summer 2021 for the whole 240 km German stretch, only a small increase upstream of km 250 in France.

Remote sensing (Sentinel-2) derived chlorophyll-a concentrations in 2021 (left) and 2022 (right) along the longitudinal profile of the Moselle from river kilometre 278 until the river mouth (at kilometre 0). Time points of the longitudinal profiles in Fig. 5 are indicated as white points. Upstream of river km 200 the bloom was a mixture of diatoms, green algae and cyanobacteria. The bloom downstream of km 120 was dominated by cyanobacteria. Maximal chl-a concentration was cut to 80 µg/L for better visualization of low chl-a situations.

Two field campaigns were conducted to obtain in situ data at 21 sampling points along the Moselle River (i.e. as “longitudinal profile”) on the phytoplankton community and physico-chemical parameters during end of August, beginning of September of each year (Fig. 5, Table S2). The spatial pattern observed in the 2022 satellite-derived chlorophyll-a data—higher concentrations in the upper and lower Moselle and lower concentrations in the middle reach—is also visible in the in situ measurements. However, the correspondence is qualitative, as absolute concentrations differ between the two datasets: e.g. high chl-a values in the lower section are underestimated by satellite imaging (compare Figs. 4 and 5A).

The in situ data show significantly higher average chl-a concentrations (48.1 µg/L, p < 0.0001, Sidak adjusted) in 2022 compared to 2021 (7.2 µg/L) and an increasing chl-a trend along the river towards the river mouth in 2022. Microscopically counted phytoplankton samples underline the different phytoplankton abundances between the two years in the longitudinal profile (Figs. 5B and S3). Phytoplankton biovolumes of around 4.7 mm3/L (range from 1.8 to 6.6 mm3/L) were reached in 2022 while in summer 2021 they were below 1 mm3/L (on average 0.6 mm3/L) with an exception at km 222, reaching a maximum of 2.2 mm3/L (Fig. S3). Microscopic examination proved that cyanobacteria dominated the phytoplankton community in 2022 with maximum relative abundance of 86% of the total phytoplankton community. Only in the section upstream of km 222, Heterokontophyta (mainly diatoms) dominated the community, downstream of km 222 cyanobacteria represented more than 70% with biovolumes of 1.3–5.7 mm3/L. Among the cyanobacteria, the genus Microcystis dominated with cell numbers going up to 1.5 × 108 cells/L (Fig. 5B) and an average abundance of 96% of all cyanobacteria and 70% of the total phytoplankton community (data not shown). Total and cyanobacterial chlorophyll concentrations in 2022 were evenly distributed in the water column (river centre; Fig. S4). In 2021 overall phytoplankton abundance was lower and dominated by diatoms. Microcystis only appeared at two stations with very low biovolumes of ≤ 0.001 mm3/L, contributing here less than 0.4% to the phytoplankton community.

Longitudinal variation of different nutrient concentrations along the Moselle river gradient and its tributary the Saar. All values are based on single water samples of 0–1 m depth from the river centre. SRP stands for soluble reactive phosphorus, TN/TP for the ratio of total nitrogen to total phosphorus and TOC for total organic carbon. Samples were taken from 23. – 27.08. 2021 and from 29.08. – 02.09.2022, respectively. Discharge at Cochem was during the sampling week on average 124 m3/s in 2021 and 36 m3/s in 2022.

During the two sampling campaigns hydrological conditions in the river were markedly different with on average 124 m3/s at Cochem in 2021 and 36 m3/s in 2022. Nutrient concentrations differed significantly (mixed effects analysis and Sidak’s multiple comparisons test) during both campaigns. Along the 242 km of the analysed river section, nitrogen containing compounds – ammonium (mean 2021 0.06 mg/L and 2022 0.03 mg/L, p < 0.01, Sidak adjusted; Table S3), nitrate (mean 2021 2.4 mg/L and 2022 0.5 mg/L, p < 0.0001, Sidak adjusted) as well as total nitrogen concentrations (mean 2021 3.0 mg/L and 2022 1.0 mg/L, p < 0.0001, Sidak adjusted) were significantly lower in the low discharge year 2022 than in the high discharge year 2021 (Fig. 5C, D, G). At all sampling sites, total nitrogen and nitrate in 2022 stayed below the values of 2021; only for individual sites ammonium concentrations in 2022 were slightly higher than in 2021, especially in the lower section of the river that generally had lower concentrations of ammonium. Soluble reactive phosphorus and total phosphorus, in contrast, showed higher concentrations at all sites in the longitudinal profile in 2022 compared to 2021 (Fig. 5E, H). This difference was statistically significant for both TP (mean 2021 0.10 mg/L and 2022 0.21 mg/L; p < 0.0001, Sidak adjusted) and SRP (mean 2021 0.05 mg/L and 2022 0.1 mg/L, p < 0.0001, Sidak adjusted). The marked difference of nitrogen and phosphorus in the longitudinal profiles of both years is also reflected in significantly different TN/TP ratios (mean 2021 30.8 and 2022 4.8, Fig. 5I; p < 0.0001, Sidak adjusted). Likewise, TOC concentrations were up to 3-fold higher in 2022 (mean 17.0 mg/L) compared to 2021 (mean 6.3 mg/L) at all sites along the Moselle gradient during the sampling campaign in late summer (Fig. 5J). This difference was significant (p < 0.0001, Sidak adjusted). In the phytoplankton rich year 2022, 79% of TOC was DOC, whereas in 2021 TOC consisted to 92% of DOC (data not shown).

Along the river continuum from km 200 in 2022, nitrate and SRP decrease significantly with distance (Spearman´s rank correlation coefficients, ρ = 0.99 (nitrate), ρ = 0.87 (SRP), both p < 0.001) towards the river mouth, whereas levels stay more or less constant from km 200 for nitrate (ρ = 0.45, p = 0.91) in 2021 and showed a less strong decrease for SRP in comparison with 2022 (quantile regression, slope difference = 0.0003, p < 0.001). Nitrate for example is going from 1.239 mg/L down to 0.047 mg/L and SRP from 0.153 mg/L down to 0.056 mg/L in 2022. Silicate shows the opposite pattern and increases in 2022 along the river gradient while it has a decreasing trend in 2021.

Discussion

Climate change increases the likelihood of weather extremes on a global and local scale, with consequences for surface water quantity and quality. In this study, we had the unique opportunity to compare two hydrological extreme regimes within the real-world set-up of a heavily anthropogenic impacted temperate river. This river acts as a sentinel for climate change with regularly occurring cyanobacteria blooms28. The real-world scenario of an unusually wet summer in 2021 and a drought summer in 2022 provided the possibility to elucidate consequences for rivers under climate change. We could show that ecology, i.e. cyanobacteria blooms, and some key water quality indicators, i.e. nutrient, chlorophyll and organic carbon concentration, are shifted by hydrological regimes, with drought scenarios becoming more likely. Our study therefore allows to draw more general conclusions on the future of anthropogenically heavily modified rivers in a more extreme future.

Hydrology was affected by weather conditions in both years. In 2022, the sum of precipitation was 15% lower compared to the long-term average in the reference period in Germany (1961–1990)29. This led to very low discharges and flow velocities in the Moselle and other rivers30,31. The high discharge during the flood in July 2021 has a recurrence interval between 5 and 10 years and the low discharge values in summer 2022 fell below the longterm median of the reference period. The latter resulted in an elongated flow time (the calculatd time a water parcel takes from the French border to the river mouth) of 31.8 days in summer of 2022 compared to 9.9 days in 2021. Cyanobacteria may benefit from this almost four times longer residence time, since their growth rates are relatively slow21,22. The year 2022 had one of the warmest summers in Germany since 1881 resulting in a historical drought in Western Germany where the catchment area of the Moselle is located32. Droughts are known to deteriorate water quality and increase water temperature7,13. River temperature under drought conditions increased in temperate regions by 2.2 °C since the 1980s7 and will continue in the future4. Long term datasets revealed an increase of summer water temperature by 0.9–1.8 °C in the Moselle for the years 2017–2022 compared to the previous 20-years’ median28. In the here studied drought year 2022, summer water temperatures were 4.2 °C higher than in the comparably wet year 2021.

Higher water temperatures can have several (negative) impacts on a river ecosystem like enhancement of biochemical reactions33, decrease of oxygen solubility and promotion of algae blooms34. Higher temperatures are known to stimulate cyanobacterial growth35,36,37. In rivers, temperatures of > 25 °C have been described to support cyanobacteria blooms making them more likely in tropical and sub-tropical regions38,39, but climate change may support their occurrence also in temperate regions. In this study, cyanobacterial growth was observed in a temperate river at an average summer temperature of 24.1 °C whereas in 2021 with an average temperature of 20.0 °C no bloom was observed. This aligns with findings from other temperate rivers, where Microcystis forms mass occurrences when water temperatures reach approximately 25 °C or higher40,41 and can then persist also at a few degrees’ lower temperatures.

Likewise, cyanobacteria blooms in rivers are known to occur mostly under low flow scenarios. Low flow velocity and higher temperature may enhance stratification and thereby support buoyant cyanobacteria22,38. Temperature vertical profiles in the Moselle however, suggested no or only a slight stratification (data not shown). In addition, regular ship traffic may disturb stratification even under a drought scenario in the river. Therefore, we do not regard stratification to be a significant factor in this system. Competition by diatoms, in contrast, which generally have a higher density due to their silicate shells, might be reduced under low flow conditions due to increased sedimentation rates in less turbulent waters42. Mitrovic et al.22 described a flow velocity of 0.03 m/s in an Australian river as sufficient to prevent a stable thermal stratification and thereby hinder cyanobacterial (Anabaena circinalis) bloom formation. In this study, we found Microcystis to grow under flow velocities of up to 0.18 m/s, suggesting a higher range of potential habitat in flowing waters for that species.

Different hydrological conditions in 2021 and 2022 also influenced nutrient concentrations. The elevated rainfall and runoff in 2021 likely led to higher non-point nutrient inputs into the river, with agricultural nitrogen and to a lesser extent phosphorus being a major source43,44. In contrast, during drought conditions surface flow and soil leaching decrease, leading to comparably lower soluble nitrogen concentrations in rivers13. Higher temperatures and low flow may have enhanced biogeochemical processes and thus denitrification in the Moselle, further reducing nitrogen concentration in the drought year. Elevated phosphorus concentrations under the low-discharge conditions of 2022 may be explained by reduced dilution of phosphorus point sources such as waste water treatment plant effluents as well as reduced input of diffuse sources. The former makes up to 52% of P-sources in the Moselle catchment and, in contrast to diffuse sources, remain constant even under drought conditions43,44,45. The pattern of reduced fluxes of TP in July and August 2022 with a subsequent distinct increase in the middle of August (Fig. S5) may be explained by reduced input of diffuse sources as well as biological processes. Distinct high TP outliers in late August 2022 may result from sampling heterogeneous Microcystis scums, which are rich in TP due to internal phosphorus storage (mainly as polyphosphate granules). Even though phosphate is often the limiting nutrient in freshwater, nutrient concentrations in the Moselle are generally plentiful and seem to be not the limiting factor28, but may reach limiting conditions during high phytoplankton production as for example during April/Mai 2021 and 2022. A reduction of ammonium and SRP along the river flow suggests consumption and incorporation of nutrients into algal/cyanobacterial biomass. However, different nutrient ratios can have an effect on the phytoplankton diversity and for example enhance cyanobacterial blooms, which are often correlated with low TN/TP-ratios46,47. Microcystis, as a non-N₂-fixing cyanobacterium, is expected at high TN/TP ratios due to its dependence on dissolved inorganic nitrogen, however it is frequently found also during low TN/TP ratios46,48,49. The relatively lower TN/TP-ratio may result in a relative lack of nitrogen during drought conditions. Furthermore, biological processes (biomass production, denitrification) may amplify this pattern during low flow, as nitrate concentrations were depleted to recorded low levels of 0.047 mg/L in 2022, which is on the verge of limitation50,51,52. Silica´s higher concentration in summer 2021 versus 2022 may be influenced by a higher wash-out from silicate rich soil and rocks in the catchment area during high flow as well as by depletion of silica by diatoms in 2022. Summer TOC concentrations peaked during the 2022 Microcystis bloom, indicating substantial biomass accumulation and enhanced extracellular organic matter production, followed by a marked post-bloom decline. Similarly, DOC concentrations were elevated during the bloom, likely driven by the release of dissolved exudates and leachates from actively growing cells53,54.

From a management perspective and based on the criteria of the Water Framework Directive (WFD), concentrations of SRP and TP in summer 2022 along the middle and lower sections of the Moselle would shift from a “Good” to a “Moderate” ecological indicator according to German assessment methods55,56. In case of TN and nitrate, the values differed significantly between the two years, both parameters are not listed in the WFD section on supporting physico-chemical quality elements for rivers56. Similarly to phosphorus species, the seasonal average of chl-a of 3.3 µg/L in 2021 and 29.9 µg/L in 2022, would imply a less good ecological status of the river from very good (threshold < 15.6 µg/L) to moderate (< 42.7 µg/L), according to the assessment criteria55,56. Another parameter in WFD-based assessment is the maximum chl-a concentration during the growing season, which was 12.3 µg/L in 2021 at Koblenz (very good status; < 31.2 µg/L) and 176.7 µg/L in 2022 (bad status; > 140.6 µg/L). However, chl-a is not a stand-alone indicator but is combined in a complex calculation with phytoplankton community composition. In the latter context, cyanobacteria are an indicator of deteriorated water quality in EU guidelines57. While for ecological status assessment according to the WFD more than the here studied indicators are necessary (e.g. benthic invertebrates, fish or chemical pollutants), our results demonstrate that low flow situations can deteriorate selected official water quality indicators. The other extreme in rivers, floods, may also deteriorate water quality. The main cause for this is the inflow and internal mobilization of suspended particles. Albeit suspended particles and turbidity are no water quality marker according to the WFD, associated pollutants such as metals58,59 or organic pollutants may be significantly raised during flood events, provoking a short-term deterioration of water WFD standards56. Nevertheless, such effects are usually short-term and only last a few days60. Long-term negative effects of floods can be morphological changes and pollution of close-by soils and drinking water aquifers by heavy metals or other pollutants58,61,62.

The occurrence of Microcystis blooms is a relatively new phenomenon for the Moselle, with a first appearance in 201728. Satellite remote sensing enables us to track the development of (toxic) cyanobacteria blooms and helps in understanding their spatial and temporal occurrence as well as crossing country borders. For example, Absalon et al.63 could track the toxic Prymnesium bloom in 2022 down the Odra river from Poland to Germany using Sentinel-2 derived data. Likewise, we could follow the bloom developing in France and building up further down the Moselle. Remote sensing data reproduced the spatial and temporal patterns observed in the in situ sampling and deliver an added value to a sole use of in situ data, but differences in absolute chl-a concentrations indicate that further methodological refinement is required. The current discrepancies between the in situ and satellite data indicate that additional training data covering a wider range of chl-a concentrations and different river types are needed to further improve the calibration and performance of the algorithm. One limitation so far is that with freely, continuously available satellite data of high spatial resolution (e.g. Sentinel-2, Landsat 8/9) no reliable differentiation of algae groups is possible64. This may change from 2029, when the hyperspectral CHIME-satellite-constellation of the Copernicus programme (Copernicus Hyperspectral Imaging Mission) will launch. Nevertheless, even at the current stage, remote sensing can enable environmental state agencies to use this tool for tracking blooms and for the WFD to monitor water quality parameters65. Finland, for example, used satellite-derived metrics for inland water bodies in the 2015–2021 WFD reporting cycle66. Moreover, cyanobacterial scum formation can be detected with satellite data and can function as an early warning system for strong cyanobacterial bloom formations67.

Conclusion

We could show in a multidisciplinary approach that a relatively wet year (2021) and a distinct dry year (2022) lead to pronounced differences in the hydrology of a regulated temperate river. This had several implications on selected water quality indicators and river ecology i.e. the development of an extensive cyanobacterial bloom in 2022. Using extensive in situ monitoring in combination with hydrological modelling and satellite remote sensing proved that low flow velocities, and higher water temperature in 2022 were favourable conditions for the development of the cyanobacterium Microcystis. Hydrology and the bloom dynamics affected biogeochemical processes and especially concentration of nutrients and organic carbon in the water column. While the high-discharge year 2021 was characterized by high nitrogen concentrations, the drier and warmer year 2022 showed higher concentrations of organic carbon and phosphorus-containing substances. As climate change will intensify further in the coming decades it can be expected that the here described effects - higher air and water temperatures, summer droughts and increase of water residence time - will cause more problems for water quantity and quality in the future and increase the likelihood of cyanobacterial blooms. Regulated rivers like the Moselle may be especially sensitive to these effects. This study therefore provides a rare showcase of how climate change will affect highly anthropogenic river systems and promote the proliferation of harmful algae blooms. Using a multidisciplinary approach of in situ monitoring, (hydrological) modelling and remote sensing can help to detect these blooms in rivers, monitor their development and better understand their causes and consequences.

Methods

The Moselle, spanning 545 km, originates in France and flows through Luxembourg before reaching Germany, where it ultimately merges with the Rhine River. Of its total length, 242 km lie within German borders and the German/Luxemburg condominium. Until 1979, the river has been consecutively established as a permanent shipping route, featuring 12 dams equipped with sluices within German territory and 10 dams further upstream in France. These dams facilitate shipping and support hydropower generation. Based on geomorphological characteristics, the German section of the Moselle can be separated into an upper (river km 240–200), middle (km 200–120) and lower reach (km 120–0) (see Fig. S6). River kilometres provided here are counted from the confluence with the Rhine (km 0) in upstream direction.

Sampling and laboratory analysis

Weekly surface (0–0.5 m) water samples were taken in Koblenz (km 5.75) with a bucket from a pontoon on the right river bank. Oxygen was measured immediately after sampling using a Hach HQ 30d Flexi probe (Hach, Loveland, Colorado, USA). Water was stored in 10 L containers and analysed within the next 3 h in the laboratory. For weekly measurements conductivity and pH were measured shortly after in the lab by WTW probes (WTW conductometer LF191 / LS1/T-1,5 and WTW pH 3310, respectively, Xylem analytics, Langenhagen, Germany). In 2021 and 2022, longitudinal profiles were conducted in late summer from the French border at km 242 to Koblenz (km 0), with 23 sampling points along the river (see Table S2 for more information). Water samples were collected from the river centre using buckets lowered from bridges. Samples for phytoplankton analysis were taken directly from the buckets at the bridge or pontoon in Koblenz, conserved with Lugol´s iodine solution with 0.5% final concentration and stored in 100 mL brown glass bottles. Water was stored in a plastic container at 4 °C and further treated after 1–3 h in in a mobile laboratory. In addition, vertical profiles of the water column at each sampling point were examined with a multiparameter probe (Exo2, Xylem Analytics, Yellow Springs, OH, USA) and a fluorometer (FluoroProbe, bbe Moldaenke GmbH, Schwentinental, Germany).

In the lab or laboratory bus, chlorophyll-a (chl-a) concentrations were measured using the AlgaeLabAnalyzer (bbe Moldaenke GmbH, Schwentinental, Germany). The bbe AlgaeLabAnalyzer measures in vivo chlorophyll-a fluorescence at multiple excitation wavelengths, enabling the distinction of algal classes based on their characteristic accessory pigment signatures. Suspended-solid concentrations were measured using pre-ignited, pre-weighed GF6 glass-fiber filters (500 °C, 1 h). Depending on particle load, 1.5–5 L of water was filtered and dried at 105 °C for 24 h. A subsequent ignition at 500 °C for 1 h provided the inorganic fraction of the suspended matter. Nutrient samples were filtered using Whatman PURADISC AQUA 30/0.45 cellulose-acetate filters and stored in sterile 15 mL polypropylene centrifuge tubes (PP, ROTILABO®, Carl Roth, Germany) at − 20 °C. Subsamples for total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), dissolved and total organic carbon (DOC, TOC) were preserved by adding sulfuric acid to a final concentration of 0.33%. TN, TP, DOC and TOC were analysed by an external company (Institut Dr. Nowak, Ottersberg, Germany) following EN 12,260-H34:2003-12, EN ISO 6878-D11:2004-09 and EN 1484:2019-04 standards. Other nutrient concentrations, including nitrate (NO₃−; after Kroon68, soluble reactive phosphorus (SRP, ISO 15681-2), ammonium (NH4+ after Searle et al.69) and silicate (Si; ISO-16264), were analysed photometrically in the laboratory using the San + + system (Skalar, Breda, Netherlands). Weekly nitrate samples in Koblenz were initially measured using the same method; however, due to implausible results, alternative bi-weekly samples were used and measured by ion chromatography (DIN EN ISO 10304-1 (D20), 940 Professional IC Vario 1, Deutsche METROHM GmbH & Co. KG, in 70794 Filderstadt) to ensure reliable measurements. Phytoplankton taxonomic assignment was conducted by an external company (Limnologie Büro Höhn, Freiburg, Germany) following the protocol described in Mischke and Behrendt70.

Weather data (precipitation, global radiation and air temperature) were obtained from the German Weather Service station in Trier-Petrisberg (Station No. 05100, km 193), while daily discharge data at Cochem (km 50.3) were provided by the Federal Waterways and Shipping Administration (WSV). Water temperature was measured at Mehring (km 173.3) with a multiparameter probe (EXO2, Xylem Analytics, Yellow Springs, OH, USA) continuously every 30 min in a water depth of approximately 0.5 m.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses and visualizations were performed using R (version 4.4.0). Extreme outliers in the measured nutrients were identified for each one using a modified IQR method. Values below Q1–4 x IQR or above Q3 + 4 x IQR were flagged as outliers. This stricter threshold reduces sensitivity to natural environmental variability compared to the standard 1.5 × IQR rule. A mixed effects model with Sidaks multiple comparisons post test was used to analyse differences in nutrient concentrations along the longitudinal profile and in weekly data between the two years. For the weekly data in Koblenz, the period from July 6 to September 5 was analysed, as this represented the pronounced low-flow period in 2022. Assessment of the relationship between nutrient concentration and distance (in km) along the river transect was calculated with Spearman´s rank correlation coefficients (p) for each nutrient individually.

Hydrodynamic modelling

Hydrodynamic features of the river were estimated through simulations performed with the hydrodynamic model HYDRAX. The 1D longitudinal model calculates discharge, water level, and flow velocities71. The model simulated the stretch of the river between Uckange (France, km 274.5) and Koblenz (Germany, km 0). The spatial resolution was 500 m and the temporal resolution 1 h, though the input data (volumetric discharge of the upper boundary and tributaries) were provided in a daily resolution from measurements. The model was calibrated and for the years 2021 and 2022 its root mean squared errors (RMSE) in water level were between 13 and 30 cm, or in mean percentage error (MPE) 0.5 to 8.3%, depending on the station. For discharge, Cochem is the only station with discharge measurements at the German Moselle. The RMSE was 78 m3/s and MPE was 1.0%. In general, hydrodynamic models present good results simulating water flows in rivers and for this reason they are widely used. However, extremes are more difficult to be reproduced. Short-term events like floods have faster dynamics that are not completely captured by the model, such as diffusive discharges or intermittent rivers. In these conditions, errors can increase considerably72. In our case, the years 2021 and 2022 had extreme characteristics of high and low flows. Nevertheless, the Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency, a more suitable metric for hydrologic parameters, was 0.95 for this period.

Based on the volume of each cell and the estimated flow velocity it is possible to estimate the average time that a mass of water takes to travel between two points, which is referred to as flow time. In this way, the flow time within the German Moselle was estimated, from the border with France until its confluence with the Rhine (~ 242 km in total). Since this quantity needed a starting date, its calculation started on the 1st, 8th, 15th and 22nd of each month. The intention was to have four values per month, considering that one month has approximately four weeks.

Remote sensing

Chl-a concentrations were retrieved along the entire river stretch from Uckange to Koblenz using data from ESA’s Sentinel-2 constellation. A Red-Near-Infrared-2-band-algorithm73 in conjunction with the C2RCC processor (C2X-Complex)74 for atmospheric correction were used to derive the chl-a content from water-leaving reflectances of all (partially) cloud-free satellite scenes in 2021 and 2022. To select these scenes, the share of cloudy or erroneous pixels within the designated river stretch was calculated using the IdePix processor75, with recording dates exhibiting more than 75% cloudy or erroneous pixels being excluded from further analysis.

Retrieved chl-a contents were calibrated and validated through repeated random sampling cross validation in conjunction with Theil-Sen regression following the recommendations of Richter et al.76 and using a reference data set of chl-a measurements (AlgaeOnlineAnalyzer and FluoroProbe, bbe Moldaenke GmbH, Schwentinental, Germany) from three examination stations and one buoy along the German river part between January 2022 and October 2024. The resulting mean absolute error (MAE) of the calibrated chl-a contents was 8.13 µg/L, its coefficient of determination (R²) 0.68. Subsequently, the data was aggregated by segmenting the river stretch into contiguous polygons of approximately one-kilometre length, totalling to 278 segments. The respective segments encompassed the whole river area except for a filter of 20 m width around obstacles (e.g. bridges, impoundments) and to the river shore based on iENC data77,78. Satellite data within each segment was then filtered for cloudy or erroneous pixels and aggregated by calculating the median if more than 50 values remained after filtering.

To visualize spatiotemporal patterns of chl-a concentration along the river continuum across two annual cycles, a bivariate interpolation using the interp function from the akima package in R79 was applied. The median chlorophyll-a values were interpolated over time (1 year) and distance (278 river kilometres) onto a regular grid of 300 × 300 points, corresponding to a temporal resolution of ~ 1.22 days and a spatial resolution of ~ 0.93 km. This interpolation was applied to enhance visualization of spatial and temporal trends between the two years, which might be obscured in the raw, unevenly spaced data.

Data availability

Seasonal and longitudinal data collected during this study are accessible via PANGAEA80 (https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.986740). Supplementary phytoplankton and probe data can be provided by request (kleinteich@bafg.de). Copernicus satellite data can be downloaded from https://code-de.org/de/. Global radiation and precipitation data can be downloaded from the German Weather Service. Discharge data of the Moselle river can be provided upon request by the data service of the German Federal Institute of Hydrology (Datenstelle-M1@bafg.de).

References

UN DESA. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2024 (UN DESA, 2024).

European Environment Agency. Europe’s state of water 2024: the need for improved water resilience (2024).

Gudmundsson, L. et al. Globally observed trends in mean and extreme river flow attributed to climate change. Science 371, 1159–1162. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba3996 (2021).

Douville, H. et al. In Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds. Change Intergovernmental Panel on Climate) 1055–1210 (Cambridge University Press, 2023).

Suarez-Gutierrez, L., Müller, W. A. & Marotzke, J. Extreme heat and drought typical of an end-of-century climate could occur over Europe soon and repeatedly. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 11023. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-01075-y (2023).

Felsche, E., Böhnisch, A., Poschlod, B. & Ludwig, R. European hot and dry summers are projected to become more frequent and expand Northwards. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 859. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01575-5 (2024).

Graham, D. J., Bierkens, M. F. & van Vliet, M. T. Impacts of droughts and heatwaves on river water quality worldwide. J. Hydrol. 629, 130590 (2024).

van Vliet, M. T. H. et al. Global river water quality under climate change and hydroclimatic extremes. Nat. Reviews Earth Environ. 4, 687–702. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-023-00472-3 (2023).

Minaudo, C. et al. Long-term impacts of nutrient control, climate change, and invasive clams on phytoplankton and cyanobacteria biomass in a large temperate river. Sci. Total Environ. 756, 144074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144074 (2021).

European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Directive 2000/60/EC of the European parliament and of the council (2000).

Van Vliet, M. T. et al. Global river discharge and water temperature under climate change. Glob. Environ. Change. 23, 450–464 (2013).

Johnson, S. L. & Penaluna, B. E. In Multiple Stressors in River Ecosystems (eds. Sergi, S. et al.) 23–44 (Elsevier, 2019).

van Vliet, M. T. H. & Zwolsman, J. J. G. Impact of summer droughts on the water quality of the meuse river. J. Hydrol. 353, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2008.01.001 (2008).

Kitheka, J. U. Salinity and salt fluxes in a polluted tropical river: the case study of the athi river in Kenya. J. Hydrology: Reg. Stud. 24, 100614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2019.100614 (2019).

Rice, J. & Westerhoff, P. High levels of endocrine pollutants in US streams during low flow due to insufficient wastewater Dilution. Nat. Geosci. 10, 587–591. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2984 (2017).

Wilbanks, K. A., Sutter, L. A., Amurao, J. M. & Batzer, D. P. Effects of drought on the physicochemical, nutrient, and carbon metrics of flows in the Savannah River, Georgia, USA. River Res. Appl. 39, 2048–2061 (2023).

Fasching, C., Boodoo, K. S., Yao, H., Rusak, J. A. & Xenopoulos, M. A. Role of lakes, flood, and low flow events in modifying Catchment-Scale DOC:TN:TP stoichiometry and export. Water Resour. Res. 60, 8596. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023wr034839 (2024).

Reynolds, C. Hydroecology of river plankton: the role of variability in channel flow. Hydrol. Process. 14, 3119–3132 (2000).

Reynolds, C. S. The Ecology of Freshwater Phytoplankton (Cambridge University Press, 1984).

Reynolds, C. & Descy, J. P. The production, biomass and structure of phytoplankton in large rivers. Archiv für Hydrobiol. Supplementband Large Rivers. 10, 161–187 (1996).

Reynolds, C. S. The long, the short and the stalled: on the attributes of phytoplankton selected by physical mixing in lakes and rivers. Hydrobiologia 289, 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00007405 (1994).

Mitrovic, S., Lorraine, J. H. & Forugh, D. Use of flow management to mitigate cyanobacterial blooms in the lower Darling River, Australia. J. Plankton Res. 33, 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/PLANKT/FBQ094 (2011).

Huisman, J. et al. Cyanobacterial blooms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 471–483. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-018-0040-1 (2018).

Carmichael, W. W. Health effects of Toxin-Producing cyanobacteria: the cyanohabs. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assessment: Int. J. 7, 1393–1407. https://doi.org/10.1080/20018091095087 (2001).

Paerl, H. W. & Otten, T. G. Harmful cyanobacterial blooms: causes, consequences, and controls. Microb. Ecol. 65, 995–1010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-012-0159-y (2013).

Bowling, L. et al. Effects of hydrology and river management on the distribution, abundance and persistence of cyanobacterial blooms in the Murray River, Australia. Harmful Algae. 30, 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HAL.2013.08.002 (2013).

O’Farrell, I. et al. Ecological meta-analysis of bloom-forming planktonic cyanobacteria in Argentina. Harmful Algae. 83, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2019.01.004 (2019).

Kleinteich, J., Frassl, M. A., Schulz, M. & Fischer, H. Climate change triggered planktonic cyanobacterial blooms in a regulated temperate river. Sci. Rep. 14, 16298. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66586-w (2024).

Deutscher Wetterdienst. Klimastatusbericht Deutschland Jahr 2022. 27 Seiten (Offenbach, 2023)

Helms, M., Wiechmann, W., Krahe, P., Meißner, D. & Maurer, T. Frühjahrstrockenheit Trifft Nun Auch Die Bundeswasserstraßen (Bundesanstalt für Gewässerkunde, 2022).

Helms, M. et al. Die Wasserstände Der großen Flüsse Steigen Wieder (Bundesanstalt für Gewässerkunde, 2022).

Imbery, F. et al. Klimatologischer Rückblick auf 2022: Das sonnenscheinreichste und eines der Beiden wärmsten Jahre in Deutschland. Deutscher Wetterdienst (2023).

Rasmussen, J. J., Baattrup-Pedersen, A., Riis, T. & Friberg, N. Stream ecosystem properties and processes along a temperature gradient. Aquat. Ecol. 45, 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10452-010-9349-1 (2011).

Cheng, B. et al. Characterization and causes analysis for algae blooms in large river system. Sustain. Cities Soc. 51, 859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101707 (2019).

Lürling, M., Mello, M. M. E., van Oosterhout, F., de Senerpont Domis, L. & Marinho, M. M. Response of natural cyanobacteria and algae assemblages to a nutrient pulse and elevated temperature. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1851. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.01851 (2018).

Robarts, R. D. & Zohary, T. Temperature effects on photosynthetic capacity, respiration, and growth rates of bloom-forming cyanobacteria. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 21, 391–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/00288330.1987.9516235 (1987).

YoonKyung, C., Cho, K., Hyuk, L., Taegu, K. & Joon, K. The relative importance of water temperature and residence time in predicting cyanobacteria abundance in regulated rivers. Water Res. 124, 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2017.07.040 (2017).

Bormans, M., Ford, P. W., Fabbro, L. & Hancock, G. Onset and persistence of cyanobacterial blooms in a large impounded tropical river, Australia. Mar. Freshw. Res. 55, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1071/MF03045 (2004).

Bowling, L. C. & Baker, P. D. Major cyanobacterial bloom in the Barwon-Darling river, Australia, in 1991, and underlying Limnological conditions. Mar. Freshw. Res. 47, 643–657. https://doi.org/10.1071/mf9960643 (1996).

Ha, K., Jang, M. H. & Joo, G. J. Spatial and Temporal dynamics of phytoplankton communities along a regulated river system, the Nakdong River, Korea. Hydrobiologia 470, 235–245 (2002).

Agha, R., Cires, S., Wormer, L., Dominguez, J. A. & Quesada, A. Multi-scale strategies for the monitoring of freshwater cyanobacteria: reducing the sources of uncertainty. Water Res. 46, 3043–3053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2012.03.005 (2012).

Reynolds, C. S. The Ecology of Phytoplankton (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Behrendt, H. et al. Nutrient Emissions into River Basins of Germany on the Basis of a Harmonized Procedure (Federal Environmental Agency (Umweltbundesamt), 2003).

Fuchs, S. et al. Phosphoreinträge in die Gewässer bundesweit modellieren-Neue Ansätze und aktualisierte Ergebnisse von MoRE-DE (2022).

German Environmental Agency (UBA) (2023). https://stoffeintraege-more.de/karten/.

Wood, S. A. et al. Contrasting cyanobacterial communities and microcystin concentrations in summers with extreme weather events: insights into potential effects of climate change. Hydrobiologia 785, 71–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-016-2904-6 (2016).

Smith, V. H. Low nitrogen to phosphorus ratios favor dominance by Blue-Green algae in lake phytoplankton. Science 221, 669–671. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.221.4611.669 (1983).

Xie, L., Xie, P., Li, S., Tang, H. & Liu, H. The low TN:TP ratio, a cause or a result of microcystis blooms? Water Res. 37, 2073–2080. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0043-1354(02)00532-8 (2003).

Dolman, A. M. et al. Cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins: the influence of nitrogen versus phosphorus. PLOS ONE. 7, e38757. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0038757 (2012).

Amano, Y., Takahashi, K. & Machida, M. Competition between the Cyanobacterium microcystis aeruginosa and the diatom cyclotella sp. under nitrogen-limited condition caused by Dilution in eutrophic lake. J. Appl. Phycol. 24, 965–971. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-011-9718-8 (2012).

Baker, D. et al. Variation in resource competition traits among Microcystis strains is affected by their microbiomes. mLife 2, 401–415. https://doi.org/10.1002/mlf2.12094 (2023).

Kim, H., Jo, B. Y. & Kim, H. S. Effect of different concentrations and ratios of ammonium, nitrate, and phosphate on growth of the blue-green Alga (cyanobacterium) microcystis aeruginosa isolated from the Nakdong river. Korea Algae. 32, 275–284. https://doi.org/10.4490/algae.2017.32.10.23 (2017).

Ye, L. et al. Dynamics of dissolved organic carbon after a cyanobacterial bloom in hypereutrophic lake Taihu (China). Limnologica 41, 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.limno.2011.06.001 (2011).

Hoikkala, L. et al. Autochthonous dissolved organic matter drives bacterial community composition during a bloom of filamentous cyanobacteria. Front. Mar. Sci. 3, 859 (2016).

Oberflächengewässerverordnung. in last amended by Article 2 of the Ordinance of 30 June 2023 (Federal Law Gazette 2023 I No. 172) (ed p. 1373 Federal Law Gazette I) (2016).

Umweltbundesamt und Bund/Länder-Arbeitsgemeinschaft Wasser. Gewässerbewertung (2025). https://www.gewaesser-bewertung.de/.

Joint Research Centre. Institute for, E., Sustainability, Cardoso, A. C., Solimini, A. G. & Heiskanen, A. S. Indicators and Methods for the Ecological Status Assessment Under the Water Framework Directive – Linkages between Chemical and Biological Quality of Surface Waters (Publications Office, 2006).

Dennis, I. A., Macklin, M. G., Coulthard, T. J. & Brewer, P. A. The impact of the October-November 2000 floods on contaminant metal dispersal in the river Swale catchment, North Yorkshire, UK. Hydrol. Process. 17, 1641–1657. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.1206 (2003).

Milačič, R., Zuliani, T., Vidmar, J., Oprčkal, P. & Ščančar, J. Potentially toxic elements in water and sediments of the Sava river under extreme flow events. Sci. Total Environ. 605, 894–905 (2017).

Göransson, G., Larson, M. & Bendz, D. Variation in turbidity with precipitation and flow in a regulated river system – river Göta Älv, SW Sweden. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 17, 2529–2542 (2013).

Weber, A. et al. The risk May not be limited to flooding: polluted flood sediments pose a human health threat to the unaware public. Environ. Sci. Europe. 35, 58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-023-00765-w (2023).

Lehmkuhl, F. et al. In Wasser, Energie und Umwelt: Aktuelle Beiträge aus der Zeitschrift Wasser und Abfall III (eds. Markus, P. et al.) 35–46 (Springer, 2023).

Absalon, D., Matysik, M., Woźnica, A. & Janczewska, N. Detection of changes in the Hydrobiological parameters of the Oder river during the ecological disaster in July 2022 based on multi-parameter probe tests and remote sensing methods. Ecol. Ind. 148, 563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.110103 (2023).

Bannari, A., Ali, T. S. & Abahussain, A. The capabilities of Sentinel-MSI (2A/2B) and Landsat-OLI (8/9) in seagrass and algae species differentiation using spectral reflectance. Ocean. Sci. 18, 361–388. https://doi.org/10.5194/os-18-361-2022 (2022).

Ansper, A. & Alikas, K. Retrieval of Chlorophyll a from Sentinel-2 MSI data for the European Union Water framework directive reporting purposes. Remote Sens. 11, 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11010064 (2018).

Papathanasopoulou, E. et al. Satellite-assisted monitoring of water quality to support the implementation of the Water Framework Directive. In EOMORES White Paper (2019).

Herrmann, M., Brehm, T., Kleinteich, J., Klotz, F. & Baschek, B. Detecting Algal Scum in an Inland River Using Planet and Sentinel-2 Multispectral Imagery 13191 (ERS (SPIE, 2024).

Kroon, H. Determination of nitrogen in water: comparison of a continuous-flow method with on-line UV digestion with the original Kjeldahl method. Anal. Chim. Acta. 276, 287–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2670(93)80396-3 (1993).

Searle, P. L. The Berthelot or indophenol reaction and its use in the analytical chemistry of nitrogen. A review. Analyst 109, 549–568. https://doi.org/10.1039/AN9840900549 (1984).

Mischke, U. & Behrendt, H. Handbuch zum Bewertungsverfahren von Fließgewässern mittels Phytoplankton zur Umsetzung der EU-WRRL in Deutschland (2007).

Oppermann, R., Schumacher, F. & Kirchesch, V. HYDRAX: Ein hydrodynamisches 1-D Modell – Mathematisches Modell und Datenschnittstellen. Report No. BfG – 1872 (Bundesanstalt für Gewässerkunde (2015).

Mesman, J. P. et al. Performance of one-dimensional hydrodynamic lake models during short-term extreme weather events. Environ. Model. Softw. 133, 104852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2020.104852 (2020).

Mishra, S. & Mishra, D. R. Normalized difference chlorophyll index: a novel model for remote Estimation of chlorophyll-a concentration in turbid productive waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 117, 394–406 (2012).

Brockmann, C. et al. Evolution of the C2RCC neural network for Sentinel 2 and 3 for the retrieval of ocean colour products in normal and extreme optically complex waters. In Living Planet Symposium 54 (2016).

Wevers, J. et al. IdePix for Sentinel-2 MSI algorithm theoretical basis document. Zenodo: Geneva Switzerland (2021).

Richter, K., Hank, T., Mauser, W. & Atzberger, C. Derivation of biophysical variables from Earth observation data: validation and statistical measures. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 6, 063557 (2012).

Voies navigables de France (2021). https://www.vnf.fr/vnf/app/uploads/ecdis/ecdis.html.

Wasserstraßen- und Schifffahrtsverwaltung des Bundes (2024). https://www.elwis.de/DE/dynamisch/IENC/.

Akima, H. A method of bivariate interpolation and smooth surface fitting for irregularly distributed data points. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. (TOMS). 4, 148–159 (1978).

Felden, J. et al. PANGAEA - data publisher for earth & environmental science. Sci. Data. 10, 347. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02269-x (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank our laboratory and field team Johannes Lingen, Heike Hähn, Claudia Günster, Walter Krings and Phillip Jung for their support and work. We acknowledge the German Weather Service for provision of weather data, the Landesamt für Umwelt Rheinland-Pfalz for chlorophyll-a data and the Federal Waterways and Shipping Agency (WSV) for their help and provision of discharge data. This work is part of the MeskalMon project and was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Transport (BMV).

Funding

This work is part of the MeskalMon project (M39600001213) and was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Transport (BMV).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.K., J.K., and H.F. designed the study. M. Helms performed hydrological analyses. M. Herrmann, T.B., and B.B. processed and analysed satellite-based remote sensing data. M.I. modelled flow velocity and residence time. F.K. and J.K. analysed the remaining dataset. The manuscript was written by F.K. and J.K., and revised collaboratively by all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Klotz, F., Herrmann, M., Ishikawa, M. et al. Spatio-temporal dynamics of riverine cyanobacteria and selected water quality indicators under two hydrological regimes. Sci Rep 16, 6508 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-38511-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-38511-w