Abstract

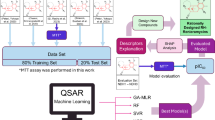

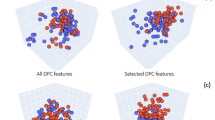

Human carbonic anhydrase (hCA) isoforms IX and XII are promising anticancer targets. Yet, their selective inhibition remains elusive due to close similarity with the abundant hCA II, whose off-target inhibition causes harmful side effects. Here, we introduce an interpretable machine learning framework to predict inhibition across hCA II, IX, and XII. To address this issue, our approach combines rigorous data curation, systematic benchmarking of classical and deep learning models, and integration of conformal prediction for uncertainty quantification with counterfactual explanations for molecular interpretability. After extensive benchmarking, we find that Support Vector Machines with extended-connectivity fingerprints consistently outperform more complex models, underscoring the importance of data quality and validation over algorithmic complexity. Here, conformal prediction provides rigorous activity estimation, while counterfactual analysis rationalizes structural features governing isoform selectivity, together enabling interpretable guidance for inhibitor design. To further test our model capability, we examine it on SLC-0111, as a selective inhibitor, which leads to a compatible result with the experiment. Our model reiterates experimental findings that modifications in the tail region strongly affect molecular selectivity, emphasizing the tail group as a key structural determinant for differentiating inhibitor activity among hCA isoforms II, IX, and XII. To facilitate adoption, we also release CAInsight, a user-friendly software with a graphical interface for virtual screening and generative design of a selective hCA inhibition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data used for this project has been retrieved from the ChEMBL database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/). All codes to reproduce the results, figures, and installing CAInsight are available at https://github.com/miladrayka/hca_ml.

References

Manzari, M. T. et al. Targeted drug delivery strategies for precision medicines. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 351–370 (2021).

Srinivasarao, M. & Low, P. S. Ligand-targeted drug delivery. Chem. Rev. 117, 12133–12164 (2017).

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Bhandari, V. et al. Molecular landmarks of tumor hypoxia across cancer types. Nat. Genet. 51, 308–318 (2019).

Pan, Y., Liu, L., Mou, X. & Cai, Y. Nanomedicine strategies in conquering and utilizing the cancer hypoxia environment. ACS Nano 17, 20875–20924 (2023).

Liu, J.-N., Bu, W. & Shi, J. Chemical design and synthesis of functionalized probes for imaging and treating tumor hypoxia. Chem. Rev. 117, 6160–6224 (2017).

D’Ambrosio, K. et al. Multiple binding modes of inhibitors to human carbonic anhydrases: An update on the design of isoform-specific modulators of activity. Chem. Rev. 125, 150–222 (2025).

Baroni, C. et al. Lasamide, a potent human carbonic anhydrase inhibitor from the market: Inhibition profiling and crystallographic studies. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 15, 1749–1755 (2024).

Eldehna, W. M. et al. Benzofuran-based carboxylic acids as carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and antiproliferative agents against breast cancer. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 11, 1022–1027 (2020).

Peerzada, M. N. et al. Discovery of novel hydroxyimine-tethered benzenesulfonamides as potential human carbonic anhydrase IX/XII inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 14, 810–819 (2023).

Kciuk, M. et al. Targeting carbonic anhydrase IX and XII isoforms with small molecule inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 37, 1278–1298 (2022).

Mishra, C. B., Tiwari, M. & Supuran, C. T. Progress in the development of human carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and their pharmacological applications: Where are we today?. Med. Res. Rev. 40, 2485–2565 (2020).

Nada, H., Meanwell, N. A. & Gabr, M. T. Virtual screening: hope, hype, and the fine line in between. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 20, 145–162 (2025).

Weissenow, K. & Rost, B. Are protein language models the new universal key?. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 91, 102997 (2025).

Rayka, M., Mirzaei, M., Farnoosh, G. & Latifi, A. M. Investigating enzyme biochemistry by deep learning: A computational tool for a new era. J. Comput. Biophys. Chem. 23, 781–799 (2024).

Hann, M. M. & Keserű, G. M. The continuing importance of chemical intuition for the medicinal chemist in the era of Artificial Intelligence. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 20, 137–140 (2025).

Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2024 (2024). https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2024/press-release.

Pitt, W. R. et al. Real-world applications and experiences of AI/ML deployment for drug discovery. J. Med. Chem. 68, 851–859 (2025).

Wang, H. Prediction of protein-ligand binding affinity via deep learning models. Briefings Bioinf. 25, bbae081 (2024).

Schapin, N., Majewski, M., Varela-Rial, A., Arroniz, C. & Fabritiis, G. D. Machine learning small molecule properties in drug discovery. Artif. Intell. Chem. 1, 100020 (2023).

Zhou, G. et al. An artificial intelligence accelerated virtual screening platform for drug discovery. Nat. Commun. 15, 1–14 (2024).

Li, L. et al. Machine learning optimization of candidate antibody yields highly diverse sub-nanomolar affinity antibody libraries. Nat. Commun. 14, 1–12 (2023).

Sapoval, N. et al. Current progress and open challenges for applying deep learning across the biosciences. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–12 (2022).

Galati, S. et al. Predicting isoform-selective carbonic anhydrase inhibitors via machine learning and rationalizing structural features important for selectivity. ACS Omega 6, 4080–4089 (2021).

Kim, S. et al. PubChem 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D1102–D1109 (2019).

Rogers, D. & Hahn, M. Extended-connectivity fingerprints. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 50, 742–754 (2010).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Géron, A. Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras, and Tensorflow: Concepts, Tools, and Techniques to Build Intelligent Systems (O’Reilly Media, Inc., 2022).

Tinivella, A., Pinzi, L. & Rastelli, G. Prediction of activity and selectivity profiles of human carbonic anhydrase inhibitors using machine learning classification models. J. Cheminf. 13, 1–15 (2021).

Zdrazil, B. et al. The ChEMBL Database in 2023: a drug discovery platform spanning multiple bioactivity data types and time periods. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, D1180–D1192 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Leak Proof PDBBind: A Reorganized Dataset of Protein-Ligand Complexes for More Generalizable Binding Affinity Prediction. (accessed 3 Jul 2024). https://arxiv.org/html/2308.09639v2 (2024).

Su, M. et al. Comparative assessment of scoring functions: The CASF-2016 update. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 59, 895–913 (2019).

Tang, J. et al. Making sense of large-scale kinase inhibitor bioactivity data sets: A comparative and integrative analysis. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 54, 735–743 (2014).

Contributors, D. Datamol: Molecular processing made easy. https://github.com/datamol-io/datamol (2025).

Rdkit: Open-source cheminformatics. https://www.rdkit.org (2023). Version 2023.9.5.

Identification of Novel Carbonic Anhydrase IX Inhibitors Using High-Throughput Screening of Pooled Compound Libraries by DNA-Linked Inhibitor Antibody Assay (DIANA) (2020). (accessed 28 Dec 2025).

Deng, J. et al. A systematic study of key elements underlying molecular property prediction. Nat. Commun. 14, 1–20 (2023).

Wallach, I. & Heifets, A. Most ligand-based classification benchmarks reward memorization rather than generalization. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 58, 916–932 (2018).

Bemis, G. W. & Murcko, M. A. The properties of known drugs: 1—Molecular frameworks. J. Med. Chem. 39, 2887–2893 (1996).

Ramsundar, B. et al. Deep Learning for the Life Sciences: Applying Deep Learning to Genomics, Microscopy, Drug Discovery, and More (O’Reilly Media, Inc., 2019).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Wigh, D. S., Goodman, J. M. & Lapkin, A. A. A review of molecular representation in the age of machine learning. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 12, e1603 (2022).

David, L., Thakkar, A., Mercado, R. & Engkvist, O. Molecular representations in AI-driven drug discovery: a review and practical guide. J. Cheminf. 12, 1–22 (2020).

Sánchez-Cruz, N., Medina-Franco, J. L., Mestres, J. & Barril, X. Extended connectivity interaction features: improving binding affinity prediction through chemical description. Bioinformatics 37, 1376–1382 (2021).

Durant, J. L., Leland, B. A., Henry, D. R. & Nourse, J. G. Reoptimization of MDL keys for use in drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 42, 1273–1280 (2002).

Chithrananda, S., Grand, G. & Ramsundar, B. ChemBERTa: Large-Scale Self-Supervised Pretraining for Molecular Property Prediction. arXiv. 2010.09885 (2020).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In ACM Conferences, 785–794 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2016).

Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y., Courville, A. & Bengio, Y. Deep Learning Vol. 1 (MIT press Cambridge, 2016).

Xu, K., Hu, W., Leskovec, J. & Jegelka, S. How powerful are graph neural networks? arxiv preprint arxiv: 1810.00826. Published online (2018).

Arvidsson McShane, S. et al. CPSign: conformal prediction for cheminformatics modeling. J. Cheminf. 16, 75 (2024).

Norinder, U., Carlsson, L., Boyer, S. & Eklund, M. Introducing conformal prediction in predictive modeling: A transparent and flexible alternative to applicability domain determination. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 54, 1596–1603 (2014).

Wellawatte, G. P., Seshadri, A. & White, A. D. Model agnostic generation of counterfactual explanations for molecules. Chem. Sci. 13, 3697–3705 (2022).

Wu, Z. et al. From black boxes to actionable insights: A perspective on explainable artificial intelligence for scientific discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 63, 7617–7627 (2023).

Pollastri, M. P. Overview on the rule of five. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. 49, 9.12.1-9.12.8 (2010).

Sosnin, S. MolCompass: multi-tool for the navigation in chemical space and visual validation of QSAR/QSPR models. J. Cheminf. 16, 1–13 (2024).

van der Maaten, L. & Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 9, 2579–2605 (2008).

Lemaître, G., Nogueira, F. & Aridas, C. K. Imbalanced-learn: A python toolbox to tackle the curse of imbalanced datasets in machine learning. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 18, 1–5 (2017).

Ash, J. R. et al. Practically significant method comparison protocols for machine learning in small molecule drug discovery. ChemRxiv (2024).

Wu, Z. et al. MoleculeNet: a benchmark for molecular machine learning. Chem. Sci. 9, 513–530 (2018).

Dwivedi, V. P. et al. Benchmarking graph neural networks. arxiv: 2003.00982 (2020).

Pembury-Smith, M. Q. R. & Ruxton, G. D. Effective use of the McNemar test. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 74, 133–9 (2020).

McDonald, P. C. et al. A phase 1 study of SLC-0111, a novel inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase IX, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 43, 484 (2020).

Pacchiano, F. et al. Ureido-substituted benzenesulfonamides potently inhibit carbonic anhydrase IX and show antimetastatic activity in a model of breast cancer metastasis. J. Med. Chem. 54, 1896–1902 (2011).

Williams, K. J. & Gieling, R. G. Preclinical evaluation of ureidosulfamate carbonic anhydrase IX/XII inhibitors in the treatment of cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 6080 (2019).

Thaingtamtanha, T., Ravichandran, R. & Gentile, F. On the application of artificial intelligence in virtual screening. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 20, 845–857 (2025).

Gangwal, A. & Lavecchia, A. Unleashing the power of generative ai in drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 29, 103992 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support and resources from the Center for High-Performance Computing (SARMAD) at Shahid Beheshti University of Iran. This work is based upon research funded by Iran National Science Foundation (INSF) under project No.4037187.

Funding

This work is based upon research funded by Iran National Science Foundation (INSF) under project No.4037187.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SSN conceptualized the study, MR and MSQ contributed equally to this study by conducting the experiments, and writing the manuscript. SSN revised the manuscript. All authors read the manuscript, provided feedback and eventually approved it in its final form.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghamsary, M.S., Rayka, M. & Naghavi, S.S. Interpretable machine learning rationalizes carbonic anhydrase inhibition via conformal and counterfactual prediction. Sci Rep (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-39771-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-39771-2