Abstract

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) often presents with significant 3D asymmetry of the torso, posing challenges for both patients and clinicians. Surface topography, based on the identification of anatomical landmarks, offers a non-invasive alternative to x-rays for monitoring shape changes over time, thereby reducing radiation exposure. However, the current gold standard, a manual landmarking process, is labor intensive and prone to error. Here, we present an automated 3D landmark digitization method designed to address these limitations. We performed the validation comparing the automated 3D landmark digitization method against the manual gQ1old standard across three phases: preliminary error assessment, geometric morphometrics (GMM) shape/size evaluation, and practical allometry application. Our results show that the automated method effectively quantifies torso shape, achieving a nonsignificant measurement error in both groups (23.1 mm in patients with p-value = 0.33; and 20.3 mm in controls with p-value = 0.30). It has also captured variance patterns comparable to the manual approach, showing high agreement for PC1 (0.94; CI95%: 0.91–0.96) and good agreement for PC2 (0.85; CI95%: 0.78–0.90), and performs similarly in assessing allometry, without significant differences in capturing the allometric signal (p-value = 0.09). However, the automated method exhibited reduced ability to capture shape variability, highlighting potential areas for improvement. These results suggest that automated, non-radiographic techniques hold promise for clinical application in tracking AIS progression. Future refinements could further improve accuracy, paving the way for safer and more efficient scoliosis management strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is a complex three-dimensional deformity of the trunk that occurs in healthy adolescents1. Changes in the shape of the spine, thorax, and trunk that increase bilateral asymmetry of the trunk, appear and progress in some cases2. Its origin, unknown, is considered multifactorial2,3,4,5. Usually, the degree of skeletal maturity and the severity of the deformity determine the likelihood of progression. The more immature and severe the curve, the greater the risk of progression during adolescence6,7.

Therefore, accurate diagnosis and follow-up of the condition is mandatory to increase the chances of slowing the progression with conservative treatment and avoiding progression to a severe condition that may lead to surgical intervention8,9. The gold standard for diagnosing AIS and assessing its progression is the Cobb angle, which is measured between the most tilted vertebrae (superior and inferior) in the spinal curve10. However, it is not without limitations. These include its two-dimensional representation of a three-dimensional state and overexposure to radiation during a critical developmental period such as adolescence11,12,13,14.

In addition, and in relation to newer health care approaches based on human-centered interventions15, the perception of cosmetic appearance by adolescents has become more relevant to AIS patients and providers. Improvement in cosmesis is the goal that generates greater consensus among experts, and more importantly, patient perceptions of improvement are more related to three-dimensional appearance than to Cobb angle changes2,16. For these reasons, there is a consolidated stream of thought that in recent years has incorporated 3D methods for AIS management. Most of these approaches are based on the asymmetry measurement of the 3D surface topography of the torso. Specifically, some based on markerless asymmetry analysis have shown limitations in attempting to reflect anatomical points of interest17,18,19, and others that use landmarks require manual measurement, which is time consuming and requires expert reviewers20.

It is of particular interest to study how the shape of the trunk changes over time in relation to the many factors involved in AIS. Allometry, the study of the relationship between shape and size changes during growth, is critical in AIS because it occurs during the significant growth spurt of puberty21,22,23,24. This may contribute to a better understanding of the potential progression of the 3D deformity. To assess shape allometry and covariation, Geometric Morphometrics Methods (GMM) provides a complete set of tools to measure and visualize shape changes in the torso21,25. However, despite this approach being carried out in the past26, it has some limitations due to its manual method of detecting torso landmarks27. Manual digitization is the gold standard, but it is time-consuming, requires a trained expert to identify landmarks, and is not feasible in clinical routine28,29,30,31. In addition, measurement error is observer dependent and is a potential source of misinterpretation of AIS phenomena. Thus, we aimed to develop and validate in three sequential steps, a novel methodology for automated landmark estimation in the torso. Validation steps comprehend a preliminary error assessment, a geometric morphometrics (GMM) shape/size evaluation, and a practical allometry application.

Results

Statistical analysis of automated method performance: preliminary evaluation

Figure 1 shows the Euclidean Distance (ED) between the automatic (obtained in FINALSURFACE and named FS) and mean manual coordinates for each of the 34 landmarks. The ED is the shortest straight-line distance between two points in space, calculated using the Pythagorean theorem32. The ED in our study, shown in blue box plots, represent the inter-method error. It was compared to the ED between the two manual datasets (orange box plots and named M) representing the expert-manual error. The average inter-method error (blue dotted lines) and the average expert-manual error (orange dotted lines) are shown for controls (dark colors) and AIS (light colors). Landmarks 8, 16 and 21–24 show the higher ED between methods (automatic and manual). In Fig. 2 the locations of these landmarks on the lateral iliac crests (8 and 16), the anterior ribcage (21 and 22), and the lateral left ribcage (23 and 24) can be observed. These areas of higher error correspond to areas of high shape variation in scoliosis, such as pelvic position and ribcage33. Additionally, there were differences in the ED for inter-method error between patients and controls (darker dotted lines are closer for controls than for patients, representing a lower ED for controls and, thus, a higher measurement error in AIS). Specifically, the error was 23.1 mm in patients (p-value = 0.33) and 20.3 mm in controls (p-value = 0.30) but these differences were not statistically significant.

Inter-method measurement error between automated and manual. Box plot of the measurement error in ED (y-axis in millimeters) of the 34 landmarks for automatic (FS) and manual (M) methods (x-axis), classified by pertinence group (controls and patients). The average ED for the 4 subgroups (interaction group*method) is shown as dashed lines (orange for M and blue for FS). The distance between the blue and orange dashed lines represent the inter-method average error for patients (light blue and orange) and controls (dark blue and orange).

The results of the Bland-Altman plot analysis show a significant increment of 1.31 (estimate average) indicating a proportional bias between the methods. The 36% of the variability of the method differences is determined by the mean of the measurements. The mean bias between methods is 22.32 mm and show statistical significance (p-value = < 0.01), but the percentage of data points outside the agreement limits (± 1.96 SD of the differences) is less than 5% (1.72%). To correct the proportional and mean bias, a logarithmic transformation of ED was performed and the results are shown in Table 1; Fig. 3. The results show that both methods are comparable, with a reduction in the magnitude of the estimate average (-0.60) and the mean bias (1.39). Only the 7% of the inter-method variability is determined by the mean of measurements. Statistical significance was observed (p-value = < 0.01) and the percentage of data points outside the agreement limits (± 1.96 SD of the differences) is less than 5% (0.80%).

Bland–Altman plot with logarithmic transformation of the Euclidean distances between the FS and M methods, averaged over 34 landmarks. The x‑axis represents the mean of log(FS) and log(M), and the y‑axis represents the log‑transformed differences (FS − M). The centered dashed blue horizontal line indicates the mean difference (bias), while the dashed red lines represent the 95% limits of agreement. A generally homogeneous distribution of data points within the limits of agreement is observed, with only two values falling outside these limits.

Statistical analysis of automated method performance: GMM shape evaluation

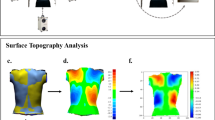

Figure 4 shows the mean shape obtained from the automatic and manual methods after a Generalized Procrustes Analysis (GPA). The superposition of the two mean shapes reflects a high qualitative similarity between the methods, i.e. both automatic and manual methods capture a similar shape geometry. Slight differences are observed medially in the back and front of the torso, suggesting that the automatic method (blue) has a higher antero-posterior diameter than the manual method (orange), and the latter has a higher left-right diameter (wider mean shape in the manual method).

Figure 5 shows the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) after GPA with normalized raw coordinates. 95% confidence ellipses are shown for the automatic method (FS) and the manual method (M). The superposition of the ellipses and the shape variability represented by PC1 suggest that both methods capture shape features very similarly. In PC2, the automatic method shows less variability than the manual method. PC1 and PC2 account for 37.5% of the shape variability.

These observations are supported by the Intra-Class Correlation (ICC) analysis. The ICC results show high agreement for PC1 (0.94; CI95%: 0.91–0.96) and good agreement for PC2 (0.85; CI95%: 0.78–0.90) according to Koo et al.34interpretation of ICC values. Significance was set as p-value < 0.01 for PC1 and PC2.

Statistical analysis of automated method performance: GMM size evaluation

Size in GMM is calculated by measuring the centroid size (CS), a single number that summarizes how far all landmarks are from their centroid (the geometric center of the torso in our study)21.

The correlation between methods in CS is significant and positive (r = 0.96 with CI95% of 0.94–0.97, and p-value < 0.01). It can be seen that the automatic method (FS) gives, on average, a slightly higher CS than the manual method (M). This finding, which first appeared in the Statistical analysis of automated method performance: Preliminary evaluation section in the form of a proportional bias, was tested in a post-hoc correlation analysis. For this purpose, we performed a Pearson correlation analysis between the ED (representing inter-method error) and the CS. It shows a significant and moderate correlation (r = 0.54, p-value < 0.01), confirming the proportional bias of the automatic method. Thus, the higher the CS, the higher the inter-method error.

Evaluation of a practical application of the automatic method compared to manual

Table 2 shows the allometry analyses for the methods and the ANOVA to test for similarity. Both methods (FS and M) show a significant relationship between shape and size (allometry). The percentage of shape variation explained by CS is relatively low in both methods (5.63% and 6.05%), but the allometric signal remains consistent in both methods. These low determination coefficients indicate a marginal effect of size on shape. Comparison between methods shows no significant difference in the capture of the allometric signal (p-value = 0.09), suggesting that both methods reliably capture a similar shape-size relationship.

Finally, the automatic coordinates were used to test for differences between patients and controls. As can be seen in Fig. 6; Table 3, both groups show a small, significant allometric effect, with significant differences in the comparison analysis between groups. For instance, controls have a significantly higher allometric effect (8.6% of shape variability explained by size) than patients (6.9% of shape variability explained by size).

Discussion

In this study, we developed an automated method for landmark estimation in the torso. We measured the inter-method error as the ED between the automated and mean manual measurements and compared it with the intra-method (intra-observer, expert) error of two manual measurements. Thus, we used two manual coordinate datasets and calculated the average as the gold standard reference. Previous attempts to validate automated methods have used one manual dataset for comparison28. In our study, the expert-manual measurements showed a lower error in terms of ED than between the automated and mean manual measurements, as previously reported in29,30. The main reason is that the identification of curve and surface semilandmarks (12 of the 34 landmarks used) in soft tissues such as the human torso, without anatomical structures or landmarks, is difficult without expert intervention29. However, it was expected that the intraobserver error (the two manual measurements) would be lower than the interobserver error (between the average manual and automated measurements). Four of the six landmarks with higher inter-method error were curve semilandmarks21,22,23,24, and two were type I landmarks located in the superior lateral aspect of the iliac crests (8 and 16), where there is no anatomical reference structure. Thus, in agreement with a previous study29, we have observed that the differences depend on the methodological approach (manual vs. automated) and the landmark typology. Another possible reason, mentioned in a previous comparative study of manual and automated methods, is that the source of this error is a combination of the error in the automated registration of landmarks with the typical variation observed in manual digitization30.

We have shown that the automated method presents higher ED in AIS torsos than in controls (+ 2.8 mm), but differences were not statistically significant. Therefore, it could be considered that the automated method captures similar shape features in both groups, showing consistency in measuring different shapes (scoliotic and non-scoliotic). Average inter-method error was 20.3 mm in controls and 23.1 mm in AIS. This error is proportional to the one evidenced in the human cranium of 2.19 ± 1.5 mm29, and other species of 0.11–1.54 mm30, considering these structures´ size and nature (bone) in comparison to the size and nature (soft tissue) of the human torso.

A proportional bias related to the automated method was observed in the Bland-Altman plot analysis, resulting in an increase of the inter-method measurement error related to the size of the torso. According to our results, the larger the torso, the higher the ED. This could be explained by the fact that the greater the distance between the reference and target meshes, the greater the effect as a potential modifier of the automated landmark projection onto the target torso.

However, when correcting for proportional and mean bias, no differences were observed between methods. In light of these results, the effect of size on measurement error may be considered in future studies.

In the second phase of the automated method evaluation, the shape differences between the methods were evaluated excluding the effect of size thanks to the Procrustes analysis. To illustrate the results, we calculated the mean coordinates for both methods and interpolated them to the reference mesh to visualize the differences (Fig. 4). Minimal differences were observed when the two methods were superimposed. It could be noticed that the automated method generated a mean surface shape that was narrower in the frontal plane, with more prominence in the medial posterior region of the torso (spinal region). We do not consider these qualitative differences in visualization to be important due to the heterogeneity of the torsos included in the sample (severe, moderate, mild and non-scoliotic torsos). Thus, although the preliminary evaluation has shown differences between automated and manual methods, the shape variation is similar, in agreement with the results reported by30.

In addition, both PCA and ICC analysis of PC1 and PC2 showed that the agreement between the two methods in capturing shape features is between good and high. An important consideration is that the automated method showed lower shape variability than the manual method, also consistent with previous results30,35. This fact, which must be critically evaluated when applied to bony anatomical structures (i.e., the skull) or smaller anatomical regions (human face), may be attenuated in the context of soft tissue surface shape or larger anatomical regions, as in the case of the human torso. However, a prospective evaluation of the clinical relevance of the reduced variability captured by the automated method will be necessary. If error levels remain within accepted clinical thresholds, automated methods could support more consistent treatment planning and follow-up, whereas systematic biases or excessive smoothing of anatomical variability would require careful clinical oversight and possibly method-specific correction factors before routine implementation36,37.

The correlation of centroid size estimates was almost maximal between methods (r = 0.96), although a non-significant overestimation of size was observed in the automated method. In addition, a significant moderate correlation was observed between the automated CS and the inter-method error (r = 0.54). This result is congruent with the proportional bias found in the preliminary evaluation, and thus, future consideration of the effect of size on the shape measurement of this method is highly recommended.

As a third step in the automated method evaluation, we tested the ability of both methods to capture the allometric signal of the sample. Allometry is the study of the relationship between size and shape21, and it is important in scoliosis studies because AIS tend to occur during critical growth periods in adolescence, when significant changes in size and shape typically occur38.

No differences were observed between the methods, and the variability of shape explained by size was similar (0.45% of the difference between the automated and manual methods). Thus, a small allometric signal is present in the sample.

A prospective evaluation of allometry in separate groups (AIS and controls) was performed using the automated method coordinates. The results showed significant differences between the groups, with a higher effect in controls (8.6%) than in AIS (6.9%). Therefore, AIS and controls have a significant allometric signal, but this effect is lower in controls. Under the light of these results, allometry does not seem to be involved in the development of AIS. However, due to the limited sample size and cross-sectional design of our study, this conclusion should be taken with caution and future studies, preferably with longitudinal follow-up, may be needed to confirm this finding.

The method presented in this study clearly provides an alternative to manual landmark collection in the torso by overcoming the limitations of excessive time and intra- and inter-observer error. It remains to be tested whether the loss of shape variability captured by the automated method may have a significant impact on clinical outcomes, although no significant differences were observed in our morphometric evaluation. Future work could aim to use the automated method landmarks for prospective analysis, for example, developing scoliosis screening models by detecting differences between controls and scoliosis, or non-radiation Cobb angle prediction models using shape asymmetry as a predictor.

Methods

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Experimental design: objectives

This study aims to develop an automated landmark detection method and compare its agreement with the gold standard manual method. To achieve this, an initial evaluation will be followed by a GMM evaluation to test the accuracy of the automated method in capturing the morphological features of the torso (shape and size). Subsequently, the allometric signal will be evaluated using data sets obtained by both automated and manual methods for comparison, and the presence of allometry in scoliotic and non-scoliotic torsos will be analyzed in detail using the automated method.

Experimental design: design of the study and sample

This is a retrospective cross-sectional study of 83 anonymized torsos with AIS and 33 controls. The requirement for ethical approval for this study was waived by the Ethics Committee for Research with Medicines of Cantabria, Spain (CEIm), as the data used were fully anonymized and derived from two previously approved studies25,26. These studies obtained ethical approval from CEIm (2019.019 and 2021.083), and all participants provided informed consent, including permission for their anonymized data to be used in future research. The need for informed consent was waived by CEIm for this retrospective analysis because all data were anonymized, and participants had explicitly consented to future use of their data during the original studies. Sex distribution was as follows: 74 females and 9 males with AIS, 15 females and 18 male controls. Mean age and standard deviation (SD) were 11.93 (2.09) in controls and 13.43 (1.76) in AIS, with an overall age range from 8 to 17.5 years old, thus including late juveniles and adolescents. Mean height in meters (SD), mean weight in kilograms (SD) and BMI (SD) were respectively 1.59 (0.09), 51.57 (12.01) and 20.41 (3.30) for the AIS group, and 1.59 (0.14), 49.53 (12.87) and 19.19 (2.37) for the control group. Within the AIS group, 26 were mild (Cobb 10°-20°), 38 were moderate (Cobb 21°-40°) and 19 were severe (Cobb > 41°) according to Negrini et al.2.

All statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software38. Packages and codes are provided as supplementary material along with the coordinates file.

Automatic digitizing in final surface

The study is based on the analysis of full torso 3D scan data acquired with a 3D sensor (Artec™ MHT, Artec3D) following a strict data acquisition protocol for patients in a standing position with the arms sufficiently abducted to allow the scan to capture the lateral areas of the torso25,26. The 3D scans result in triangulated surfaces with 70,000-150,000 vertices for each participant. For the implementation of the automatic landmark identification method, a development environment based on C + + Visual (Studio 19.0 Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, USA) in combination with a graphical user interface (FINALSURFACE, developed in-house, GFaI, Berlin) was used. For this study, a set of 34 landmarks distributed over the entire torso surface was selected and evaluated. The set consists of 22 directly measured landmarks and 12 interpolated landmarks calculated by interpolation and back-projection onto the torso surface (Fig. 2).

The algorithmic approach for identifying the patient landmarks is based on a template torso surface mesh (~ 70.000 vertices) with manually selected landmarks which is registered to a new patient torso scan within a three-step procedure including a global rigid registration, a local rigid registration and a final elastic registration. All registration deformations are only applied to the template mesh while preserving the position and shape of the patient mesh in order to allow a direct comparison of the manually and automatically predicted landmarks in an identical coordinate system. The method of ‘morphable’ anatomic shape models was initially applied to face 3d-scans and is adapted and expanded for torso scans in this study39. To construct the template torso mesh, ten individual training torsos covering a wide range of shape and size variation were used with manually determined landmarks. Five were females and five were males, non-scoliotic and therefore with low asymmetry characteristics. Mean age (SD) of models was 12.39(2.46), mean weigh (SD) and heigh (SD), 48.05(14.62) and 1.56(0.14) respectively, and BMI of 19.21(2.81). To further improve their symmetry and obtain perfect reference torsos, a reflection and relabeling analysis was performed to obtain their mean shape coordinates and mesh, following the protocol described in a previous study20. A mean torso template mesh was then calculated applying the rigid and elastic registration procedure for each of the ten patients with a starting torso template mesh. Subsequently the principles of ‘Procrustes-Analysis’ were applied to the ten registered torso meshes to calculate a mean torso template mesh for both sexes which ideally covers most of the variation of a normal distributed population. These mean-template meshes were subsequently used and applied to identify the landmarks for the complete sample size.

First step: rigid global alignment.

The first step in the registration process is a global rigid alignment (affine transformation: translation, rotation, uniform scaling) of the template to the new torso mesh using an iterative closest point (ICP) approach40. To ensure that both meshes are sufficiently pre-aligned prior to ICP matching, the following steps were taken:1each torso was aligned with the chest facing forward (positive X-axis) in a global coordinate system2, the reference mesh was translated to match the geometric volume centers of both meshes3, a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) using the X, Y, Z axes as parameters was performed to align the major axis of the torsos, and4isotropic scaling was applied to the reference mesh to approximately match the bounding boxes of both torsos. After this initial procedure, ICP matching was performed using the ‘Euclidean Distance’ option and a subdivision of the torsos (kd-tree) into k = 15–20 equal volumes. The algorithm was used with approximately 10,000 correspondence points between the two meshes and uses a single value decomposition to find the optimal matching position (rotation, translation, isotropic scaling) that minimizes the sum of the distances between the meshes.

However, in this state we still have two different torso meshes with different non-homologous vertex positions and different number of vertices. Therefore, the following steps aim to achieve a complete homologous mesh registration with locally corresponding vertex positions of the template and target patient meshes.

Second step: rigid local alignment.

In the second step, a rigid local registration is used for different sub-regions of the torso. The sub-regions were defined as Voronoi cells around each torso landmark (Fig. 7D). Therefore, the landmarks were used as seed points to compute the Voronoi cells around each landmark. A surface point belongs to a Voronoi cell if the Euclidean distance to the corresponding landmark is shorter than to other landmarks. To calculate the corresponding Voronoi cells on the patient torso mesh, the landmarks of the template mesh were projected onto the patient mesh simply by calculating the shortest ‘Euclidean’ distance between the initially aligned template landmark positions and the patient torso mesh. The corresponding Voronoi cells were then calculated for the patient mesh in a similar manner. For each subregion or Voronoi cell, local ICP matching was performed to align the template Voronoi cells with the patient Voronoi cells. This registration step uses local shape features of the torso for alignment and provides a landmark estimate for the patient’s torso. Using local shape features in separate Voronoi cells was found to be superior to global ICP matching of the torsos, since anatomical anisotropic shape variations of the torsos can be very large (length and width differences), preventing uniformly distributed local matching.

Workflow in finalsurface. A female reference mesh (A) and a female patient with AIS (B) are subjected to a rigid global alignment (C). Then, the rigid local alignment shows the 34 landmarks (red dots) with their corresponding Voronoi cells (D). Finally, the elastic mesh registration step produces an automatically estimated mesh of the patient (E). An overlay of the original patient torso (B) and the estimated torso (E) is shown in (F).

Third step: elastic mesh registration.

In this step, both meshes, the template and the patient torso mesh, are already globally and locally aligned, and the predicted landmark positions on the patient torso can be estimated from the position of the rigidly locally aligned Voronoi cells of the template torso mesh. However, we still have two different meshes with non-corresponding numbers of vertices in the template and patient meshes. Therefore, a final three-dimensional elastic registration step is performed. For this purpose, the principles of the Thin Plate Spline (TPS) theory are applied41. The TPS theory uses a set of driving points (our landmark estimates of the template mesh) and their corresponding 3D movements (the last rigid alignment process) as a vector to control a 3D elastic deformation of a corresponding surface mesh structure (our initially rigidly aligned template mesh). This results in an elastic 3D registration of the initially rigidly aligned template mesh to the target patient mesh. An optimization procedure within the TPS registration deforms the template mesh to preserve its topology with minimal distortion energy, avoiding misshaped triangles. In a final step, the residual distance between the rigidly and elastically registered template mesh and the patient mesh is eliminated by calculating the projected distance between the template vertex points (along the vertex normal directions) and the patient torso surface. This final step results in a rigidly and elastically registered template mesh with landmark estimates and a fully homologous mesh structure with corresponding mesh points. This registered mesh can be used as a starting point for a statistical shape model (SSM) or further statistical analysis, including principal component analysis.

Data acquisition

Manual 3D landmark coordinates were taken from previous studies20,25,26. Two datasets were used to account for manual measurement error (expert measurement error). From the original landmark template of 160 landmarks and semilandmarks used, 34 were selected (Type I landmarks [n = 22], curve semilandmarks [n = 6], and surface semilandmarks [n = 6]). This landmark typology is based on42. Figure 2 shows the location of the 34 landmarks that completely cover the 3D torso mesh. The rationale for the selection of these 34 specific landmarks was based on the typology, giving preference to type I landmarks used in previous studies, and completing the areas between them with curve and surface semilandmarks. The anatomical homology of the type I landmarks is higher than that of the semilandmarks, which usually require sliding processes to acquire comparable homology, and are mostly located in areas that are not easily attributable to anatomical structures. They are also representative of scoliosis features not only in the posterior but also in the lateral and anterior surfaces of the trunk, including the common chest asymmetries observed in adolescents with scoliosis43,44.

The homologous automatic landmark coordinates (n = 34) were extracted from FINALSURFACE using the mesh registration feature. Each average reference mesh (male or female) was aligned to the target patient torso with reference landmarks projected onto the target surface to obtain automatic landmark coordinates as explained in the Automatic Digitizing in Final Surface section. A visual representation of the entire process is shown in Fig. 7.

Statistical analysis of automated method performance: preliminary evaluation

The ED between automated and mean manual coordinates was measured to account for inter-observer (inter-method) error. Considering that the manual method is the gold standard in landmark methods28, we used the mean coordinates of the two manual datasets as a reference. We then compared the ED between the automatic and mean manual coordinates to the ED between the two manual coordinate datasets (representing the expert measurement error).

The same analysis and visualization were repeated separately by group (patients and controls). Differences between methods (automatic and manual) in terms of ED for each group were subjected to statistical analyses for potential differences in inter-method error depending on belonging to control or patient group. Independent samples t-test with significance level < 0.05 was performed.

A Bland-Altman plot analysis was then performed to examine the agreement between the methods. Because the differences between automated and manual ED measurements increased with the magnitude of the size, a logarithmic transformation was applied, allowing proportional bias and heteroscedasticity to be modeled on a log scale and the limits of agreement to be interpreted as ratio/percentage differences between methods, as recommended in agreement methodology45.

Statistical analysis of automated method performance: GMM shape evaluation

A GPA was performed on the normalized raw coordinates46. This normalization, which consisted in transforming them to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, aimed at eliminating the differences in scale and variability related to the different coordinate systems used (manual and automatic). It was performed in the 3 dimensions (X, Y, Z), ensuring that no single landmark dominates the PCA due to its greater range.

Then, the mean shape coordinates for the automatic and manual methods were extracted from the GPA and interpolated in a reference mesh to qualitatively evaluate the differences between the two mean shapes (automatic and manual).

After GPA, PCA was performed using the two methods as classifiers (manual and automatic) to explore individual and method variability in shape. Agreement between methods was measured using a two-way mixed effects model with absolute intraclass correlation (ICC) of PC1 and PC2 for model agreement (raters). No prior assumptions between raters (manual and automated) were considered for this analysis.

The size differences, measured as centroid size-CS47 between the automated and manual methods were tested for agreement in size estimation. In addition, a post hoc analysis was performed to test the hypothesis of proportional bias identified in the preliminary evaluation section. It consisted of a Pearson correlation analysis of ED (representing the error between methods) with size (CS) to test the null hypothesis of no relationship between error size and size.

Evaluation of a practical application of the automatic method compared to manual

The allometric signal of the automatic (FS) and manual (M) methods was estimated for comparison and validation. The potential use of the proposed automatic method in future studies must be subjected to the concordance of its results with the gold standard (manual). A correlation analysis of shape (by GPA) and size (log CS) was performed for the FS and M methods.

After ensuring an accurate representation of allometry for FS, we used the automated coordinates to test allometry between patients and controls. As in the method validation, a correlation analysis of shape (by GPA) and size (log CS) was performed for both groups.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Grivas, T. B., Vasiliadis, E. S. & Rodopoulos, G. Aetiology of idiopathic Scoliosis. What have we learned from school screening? Stud. Health Technol. Inf. 140, 240–244 (2008).

Negrini, S. et al. 2016 SOSORT Guidelines: Orthopaedic and Rehabilitation Treatment of Idiopathic Scoliosis during Growth Vol. 13, 1–48 (Scoliosis and Spinal Disorders, 2018).

Guo, X. et al. Relative anterior spinal overgrowth in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis—result of disproportionate endochondral-membranous bone growth? Eur. Spine J. 14(9):862–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-005-1002-7 (2005).

Wang, W. J. et al. Top Theories for the Etiopathogenesis of Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. J. Pediatric Orthopaed.. https://journals.lww.com/pedorthopaedics/fulltext/2011/01001/top_theories_for_the_etiopathogenesis_of.3.aspx (2011).

Cheng, J. C. et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2015.30 (2015).

WeinsteinSL The natural history of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 39 (Issue 6, Supplement 1 Suppl 1), S44–S46 (2019).

Weinstein, S. L. et al. Health and function of patients with untreated idiopathic scoliosis: a 50-year natural history study. JAMA 289 (5), 559–567 (2003).

NB, J. D., CC, H. & PR, M. M. N. B, JS L. Screening for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Systematic Evidence Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [Internet]. Screening for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis (A Systematic Evidence Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force, 2018).

Negrini, F. et al. Developing a new tool for scoliosis screening in a tertiary specialistic setting using artificial intelligence: a retrospective study on 10,813 patients: 2023 SOSORT award winner. Eur. pine J. 32(11):3836–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-07892-1 (2023).

Horng, M. H., Kuok, C. P., Fu, M. J., Lin, C. J. & Sun, Y. N. Cobb Angle Measurement of Spine from X-Ray Images Using Convolutional Neural Network. Comput. Math. Methods Med. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30996731 (2019).

Grant, C. A., Johnston, M., Adam, C. J. & Little, J. P. Accuracy of 3D surface scanners for clinical torso and spinal deformity assessment. Med. Eng. Phys. 63, 63–71 (2019).

Vergari, C. et al. Quasi-automatic early detection of progressive idiopathic scoliosis from biplanar radiography: a preliminary validation. Eur. Spine J. 28 (9), 1970–1976 (2019).

Levy, A. R., Goldberg, M. S., Mayo, N. E., Hanley, J. A. & Poitras, B. Reducing the lifetime risk of cancer from spinal radiographs among people with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 21 (13), 1540–1547 (1996).

Ronckers, C. M. et al. Cancer mortality among women frequently exposed to radiographic examinations for spinal disorders. Radiat. Res. 174 (1), 83–90 (2010).

Levander, X. A. et al. The Role of Human-Centered Design in Healthcare Innovation: a Digital Health Equity Case Study. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 39(4), 690–5.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08500-0 (2024).

Schreiber, S. et al. Patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis perceive positive improvements regardless of change in the Cobb angle – Results from a randomized controlled trial comparing a 6-month Schroth intervention added to standard care and standard care alone. SOSORT 2018 Award winner. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-019-2695-9 (2019).

Ghaneei, M., Ekyalimpa, R., Westover, L., Parent, E. C. & Adeeb, S. Customized k-nearest neighbourhood analysis in the management of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis using 3D markerless asymmetry analysis. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin. 22 (7), 696–705 (2019).

Komeili, A. et al. Surface topography asymmetry maps categorizing external deformity in scoliosis. Spine J. 14 (6), 973–83e2 (2014).

Rothstock, S., Weiss, H. R., Krueger, D. & Paul, L. Clinical classification of scoliosis patients using machine learning and markerless 3D surface trunk data. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 58 (12), 2953–2962 (2020).

González-Ruiz, J. M., Pérez-Núñez, M. I., García-Alfaro, M. D. & Bastir, M. Investigating Human Torso Asymmetries: An Observational Longitudinal Study of Fluctuating and Directional Asymmetry in the Scoliotic Torso. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-8994/13/10/1821 (2021).

Klingenberg, C. P. Size, shape, and form: concepts of allometry in geometric morphometrics. Dev. Genes Evol. 226 (3), 113–137 (2016).

Di Felice, F., Zaina, F., Donzelli, S. & Negrini, S. The natural history of idiopathic scoliosis during growth: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 97 (5), 346–356 (2018).

Chulani, V. L. & Gordon, L. P. Adolescent Growth and Development. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice 41(3), 465–87. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0095454314000335 (20140.

Dimeglio, A. & Canavese, F. The immature spine: growth and idiopathic scoliosis. Ann. Transl. Med. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32055613 (2020).

González-Ruiz, J. M., Pérez-Núñez, M. I., García-Alfaro, M. D. & Bastir, M. Geometric morphometrics of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a prospective observational study. Eur. Spine J. (2020).

González-Ruiz, J. M. et al. Vitamin D and adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, should we stop the hype? A cross-sectional observational prospective study based on a geometric morphometrics approach. Eur. Spine J. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-07566-y (2020).

Fruciano, C. Measurement error in geometric morphometrics. Dev. Genes Evol. 226 (3), 139–158 (2016).

Porto, A., Rolfe, S. & Maga, A. M. ALPACA: A fast and accurate computer vision approach for automated landmarking of three-dimensional biological structures. Methods Ecol Evol.https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13689 (2021).

Bermejo, E. et al. Automatic landmark annotation in 3D surface scans of skulls: Methodological proposal and reliability study. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169260721004545 (2021).

Percival, C. J. et al. The effect of automated landmark identification on morphometric analyses. J. Anat. https://doi.org/10.1111/joa.12973 (2019).

González, J. M. R. Técnicas morfo-geométricas Para El análisis De Las asimetrías Del Torso En Adolescentes Con Escoliosis idiopática. Morphogeometric Methods for the Analysis of Torso Asymmetries in Adolescents with Idiopathic Scoliosismorphogeometric Methods for the Analysis of Torso Asymmetries in Adolescents with Idiopathic Scoliosis (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid; CSIC - Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (MNCN), 2023).

Ultsch, A. & Lötsch, J. Euclidean distance-optimized data transformation for cluster analysis in biomedical data (EDOtrans). BMC Bioinform. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-022-04769-w (2022).

Dalleau, G. et al. Pelvis Morphology, Trunk Posture and Standing Imbalance and Their Relations to the Cobb Angle in Moderate and Severe Untreated AIS. PLoS One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0036755 (2012).

Koo, T. K. & Li, M. Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 15 (2), 155–163 (2016).

Savriama, Y. & Tautz, D. Testing the accuracy of 3D automatic landmarking via genome-wide association studies. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics. https://doi.org/10.1093/g3journal/jkab443 (2022).

Al-baker, B., Alkalaly, A., Ayoub, A., Ju, X. & Mossey, P. Accuracy and reliability of automated three-dimensional facial landmarking in medical and biological studies. A systematic review. Eur. J. Orthod. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjac077 (2023).

Polizzi, A. & Leonardi, R. Automatic cephalometric landmark identification with artificial intelligence: An umbrella review of systematic reviews. J. Dent. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0300571224002252 (2024).

pmc_10919743.

Schneider, D. C. & Eisert, P. Fitting a Morphable Model to Pose and Shape of a Point Cloud. VMV 2009 - Proceedings of the Vision, Modeling, and Visualization Workshop 2009. 93–100 p. (2009).

Rusinkiewicz, S. & Levoy, M. Efficient variants of the ICP algorithm. In: Proceedings Third International Conference on 3-D Digital Imaging and Modeling. pp. 145–52. (2001).

Keller, W. & Borkowski, A. Thin plate spline interpolation. J. Geod. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-019-01240-2 (2019).

Bookstein, F. L. Morphometric Tools for Landmark Data: Geometry and Biology [Internet]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/A18AD895945610BAD6396E76CEB512CD (1992).

Denoel, C. et al. Idiopathic scoliosis and breast asymmetry. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 62 (10), 1303–1308 (2009).

Applebaum, A., Nessim, A. & Cho, W. Understanding breast asymmetry and its relation to AIS. Spine Deform. 8 (3), 381–386 (2020).

Bland, J. M. & Altman, D. G. Statistics Notes: The use of transformation when comparing two means. BMJ https://www.bmj.com/content/312/7039/1153.abstract (1996).

Rudemo, M., Statistical Shape Analysis, I. L., Dryden, Mardia, K. V. & Wiley, C. No. of pages: xvii + 347. Price: £60.00.ISBN 0-471-95816-6. Stat Med. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0258(20001015)19:19%3C2716::AID-SIM590%3E3.0.CO (1998).

Rohlf, F. J. & Slice, D. Extensions of the procrustes method for the optimal superimposition of landmarks. Syst. Biol. 39 (1), 40–59 (1990).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors have equal contribution.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

González-Ruiz, J.M., Rothstock, S. Comparative analysis of a manual and an automated 3D landmark digitization method of the torso in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis. Sci Rep 16, 7388 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-40627-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-40627-y