Abstract

Movies can implicitly promote social and ideological norms on a mass scale, making them powerful socialization agents, especially among children. However, Hollywood movies are no longer confined to the influence of American ideals, as media companies now have to consider the growing influence of markets such as China. With this in mind, this paper explores the portrayal of gender, power, and gendered roles across two versions of Disney’s Mulan (1998 and 2020). Specifically, it explores male-coded and female-coded characters’ talk for portrayals of gender and the enactment of assigned roles through conversational strategies and the content of talk. Findings indicate a subtle shift in the distribution of “dominant” discourse between the two versions, despite female-coded characters being framed as dutiful wives, brides-to-be, and/or mothers in both movies. Specifically, in Mulan 2020, male-coded characters are portrayed as more “feminine” through their talk, while female-coded characters—particularly Mulan and Xianniang—are portrayed as more “masculine”, further highlighting a recent trend for more nuanced portrayals of gender in Disney movies. Based on these results and others, the paper argues that the portrayal of gender in Mulan 2020, while still primarily associated with heteronormative roles in service of a patriarchal world, has undergone subtle changes that may reflect American and Chinese influences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Children are born not knowing what it means to be male or female. External influences, especially parents, teachers, and societal expectations play crucial roles in (re)enforcing gender ideals upon them. For example, gender can be construed by selecting the color of clothes, buying robots for boys and dolls for girls, or grouping students by gender in school. Since gender inequality remains an issue in most societies, it is important for adults to promote gender equality during a child’s developmental stage (Rice, 2014). One powerful way in which we can do this is through the media we expose them to. In movies, for instance, certain types of stereotypical male and female portrayals can negatively influence children’s gender perceptions and behaviors (Golden and Jacoby, 2018; Hine et al., 2018), and thus we should be mindful when exposing such content to our children.

From a poststructuralist view on gender, stereotypes can be especially harmful to young females (Rice, 2014), yet they continue to be perpetuated by media companies such as Disney (Coyne et al., 2016; Hentges and Case, 2013; Primo, 2018). Moreover, gendered stereotypes are often enacted in subtle ways, such as through characters’ verbal interactions (Onyenankeya et al., 2019). However, much of the “gendered” talk in media seemingly reflects heteronormative discourse, such as male-coded characters enacting hegemonic masculinity, or female-coded characters using language to index heteronormative ideals of femininity (Raymond, 2013). Yet, in reality, conversational strategies and talk that are indexical of identity markers (including gender) vary in relation to different speaker populations and the purpose of talk in a given setting (Stubbe, 2013; Yoong, 2018). Hence, by exposing children to such decontextualized representations of dialogue assigned to male-coded and female-coded characters, media appear to be promoting a form of discursive practice that homogenizes a wide range of human identities and roles (Raymond, 2013). Consequently, children may acquire embodied practices that are not contextually appropriate, which only perpetuate hegemonic divides (Ward and Aubrey, 2017). However, to our knowledge, there has been relatively little investigation into the talk of male-coded and female-coded characters in Disney films.

Moreover, at the time of the present study, there has been increasing concerns as to the influence of the Chinese market on the American entertainment industry. As Clark (2021) notes, China is now the biggest movie market in the world, and thus it is perhaps not surprising that it has garnered enough power to influence American productions (Yang, 2020). As Fairclough (2003) notes, the production and reception of language (or texts) can be influenced by current social events and constructions. Accordingly, the content and verbal interactions found in media can often reflect the dominant social structures at their time of production (Douglas et al., 2022). However, to the best of our knowledge, there has been no research into how the increasing influence of China has affected the portrayals of gender and gender assigned roles in American-made films, especially those aimed at children. We feel that this is an important area of study, especially in light of the historical suppression of feminist struggles in China (see Fincher, 2018).

Accordingly, we explore the portrayal of gender, power, and assigned gender roles in two versions of Disney’s Mulan (1998 and 2020). More specifically, we explore male-coded and female-coded characters’ talk with regard to portrayals of gender and the enactment of assigned roles through conversational strategies and the content of talk. In this light, we contribute to a growing body of literature that examines the portrayals of gender and sex roles in children’s media, but do so through a focus on language rather than behavior, which has been the dominant approach thus far. Moreover, by comparing two versions of the same story at different points in time, our study is one of the first, if not the first, to explore the potential influence of the Chinese market on the representation of gender in an American-made movie.

Gender, children’s media, and “gendered” language

Children are associated with a gender when they are born. Even though newborn babies cannot identify themselves as boys or girls, others can usually identify their gender based on the names their parents give them or the color of the clothes they are dressed in. When children are sent to school, genders are further reinforced when they are split into boys and girls for activities or playtime (Granger et al., 2016) or are exposed to children’s literature that promotes stereotypes (Anderson and Hamilton, 2005; Baker-Sperry, 2007). Outside of school, gender reinforcement continues, as most people treat girls more gently than boys, and assigned roles become further engrained through participation in sports and media (Hardin and Greer, 2009) and through the marketing of gendered toys (Auster and Mansbach, 2012). These practices, and others, reinforce children’s growing perceptions and behaviors, as they continue to imitate the world around them, including the language they hear (Coates, 2015).

Gender in children’s movies

Of particular interest to the current study is the role played by media in this process of gender (re)enforcement. It has been repeatedly shown that a child’s idea of gender can be subtly influenced by media (Douglas et al., 2022; Thompson and Zerbinos, 1995). Golden and Jacoby (2018), for example, examined preschool girls’ interpretations of gender stereotypes in Disney Princess movies through role-plays and discussions. Results showed that girls preferred the princess role, and paid more attention to their physical appearance than what they were doing; in fact, they often overacted just to attract boys’ attention. This behavior seemed to be the result of the girls imitating the princesses they observed and focusing on what they perceived as good attributes and characteristics. Namely, looking good and attracting men.

Similarly, Hine et al. (2018) explored children’s perceptions of gender in two Disney Princess movies. They asked children to describe the characteristics of Aurora (Sleeping Beauty) and Moana (Moana). The children believed that Aurora was more feminine than Moana, and that Moana was not a princess because she did not have the desired feminine attributes. Similar stereotypical beliefs were evidenced by Coyne et al. (2016), who investigated the level of engagement between children’s behaviors and Disney Princess products. The authors concluded that such stereotyping could negatively influence children’s behaviors, such as girls may develop preconceived notions that females cannot explore the world on their own.

Such stereotypical portrayals of gender are common in Disney media, wherein male-coded characters are often portrayed as more adventurous, assertive, powerful, braver, and generally more accomplished (Streiff and Dundes, 2017a, 2017b); female-coded characters, on the other hand, are typically portrayed as affectionate and helpful, yet always causing trouble (Aley and Hahn, 2020; Baker and Raney, 2007; England et al., 2011; Leaper et al., 2002). However, several studies have indicated a move toward more positive portrayals of female-coded characters in some of the more recent Disney Princess movies. England et al. (2011), for instance, examined the portrayals of princes and princesses in nine Disney Princess movies from 1937‒2009. Using content analysis to code princes’ and princesses’ behaviors across the movies, their results indicated that the portrayal of gender stereotypes fluctuated over time, with female-coded characters showing wider variation in their traits than male-coded characters. Baker and Raney (2007) also found fluctuating gender stereotypes in their examination of superhero cartoons. However, we find their results somewhat unsurprising given that superheroes are extraordinary individuals, who are usually endowed with magical or mystical powers that place them above mere mortals.

Other research has convincingly argued that the portrayal of male Disney characters has become more nuanced over time (Gillam and Wooden, 2008; Primo, 2018). For instance, in his postfeminist analysis of several male-coded Disney characters—mainly those found in The Incredibles—Macaluso (2018) argues that recent Disney movies go beyond the usual tropes of hero/prince, coming-of-age boy, and villain to offer new ways of doing masculinity. Specifically, he argues that Disney males now frequently experience masculinity in a more reflective, modern way, whereby vulnerabilities are highlighted in relation to work, family, and expectations.

Overall, it is well accepted that children are enculturated into a gender binary system with associated gendered norms and roles, and movies are an influential contributor to this process. Moreover, although studies show that there are non-stereotypical portrayals of male-coded and female-coded characters in some of the newer Disney movies (Baker and Raney, 2007; England et al., 2011; Gillam and Wooden, 2008; Macaluso, 2018; Primo, 2018), stereotypical portrayals still persist (Aley and Hahn, 2020; Leaper et al., 2002; Streiff and Dundes, 2017a, 2017b). In addition, previous studies exploring gender and assigned gender roles in Disney Princess movies have mainly analyzed the portrayals of male-coded and female-coded characters in terms of behavior and personality traits, rather than their use of language and the content of talk, and even then, this has been done with a bias toward Western perspectives. Hence, it is our belief that further insights can be gained by analyzing male-coded and female-coded characters’ talk in movies (see also Chepinchikj and Thompson, 2016), as well as considering the influence of globalization on gender portrayals in movies.

“Gendered” language

In recent years, the focus on connections between gender and language has shifted from the earlier, deterministic notions of “male and female talk” (Lakoff, 1975) to a more nuanced understanding of how language, gender, and sexuality intersect with cultural and situational contexts through notions such as hegemonic masculinity (Hearn and Morrell, 2012) and “doing femininity” in communities of practice (Holmes and Schnurr, 2006). In Mulan, characters are encoded as heteronormative adult males or females. Hence, in this section, we focus on studies that have examined the talk-in-interaction of such populations.

Schippers (2007) sees hegemonic masculinity as “the qualities defined as manly that establish and legitimate a hierarchical and complementary relationship to femininity and that, by doing so, guarantee the dominant position of men and the subordination of women” (p. 94). These qualities are typically seen as heterosexuality, dominance, and physical strength, and they can be manifested in talk-in-interaction in various ways. Coates (2003) and Kiesling (1997), for instance, show how British and American heterosexual males, respectively, index hegemonic, heteronormative masculinity through various strategies that are said to enact power in same-gender conversations, such as increased use of commands, directives, and questions, or talking about “masculine” subjects such as sport, technology, or sexual conquests. Similarly, in their meta-analytic review of 70 studies published between 1960 and 2005, which focused on gender variations in adult’s language use, Leaper and Ayres (2007) found that males were more likely to use self-emphasizing speech acts such as direct suggestions or task-oriented statements, which some scholars attribute to a “reporting style” of speech (e.g., Newman et al., 2008). Such links between power (reporting style), heterosexuality, and masculinity, in Western males’ talk is evident in numerous other studies (e.g., Cameron, 2001; Hazenberg, 2016; Holmes and Schnutt, 2006; Jones, 2016; Kiesling, 2002; Leaper, 2019; Newman et al., 2008; Pearce, 2016).

Conversely, heteronormative “feminine” discourse in Western settings is said to include “linguistic, pragmatic and discursive devices, which signal considerateness and positive affect” (Holmes and Schnutt, 2006, p. 36), as well as increased use of collaborative strategies, such as showing understanding or giving support (Leaper and Ayres, 2007). Such relational work—i.e., orienting to others—is often seen as key to “doing femininity” for heteronormative Western females (Fletcher, 2001), and includes a range of rapport building strategies such as the use of emotion words, hedges, hesitations, minimizers, and modalized interrogatives (Holmes and Marra, 2004; Gamble and Gamble, 2020; Jones, 2016; Newman et al., 2008). Such rapport building or “relational talk” is best framed positively, as many speakers employ it to achieve their conversational goals and thus, by doing so, are displaying communicative competence rather than kowtowing to dominant others (Holmes and Schnutt, 2006; Pearce, 2016). As per masculinized talk, feminized talk is frequently found in media portrayals of heterosexual female characters (Li et al., 2022), or when male-coded characters are portrayed as deviatiating from normative practices (Raymond, 2013).

Some scholars rightly argue that a bifurcation of discourse into “masculine talk” and “feminine talk” is problematic, as it perpetuates a binary divide that is exclusionary to all other forms of talk (Yoong, 2018). Specifically, such labels have evolved out of studies into heteronormative adult discourse in Western settings; thus, a number of affective variables have seemingly been conflated—sexuality and gender being among them. Nevertheless, such polarizations of conversational practices are commonly used in Western media to enact character identities at the micro-interactional level and (re)establish social norms of heterosexuality and “traditional” gender roles (Li et al., 2022; Raymond, 2013; Ward and Aubrey, 2017). Accordingly, we use the notion of heteronormative masculine/feminine discourse as a sensitizing concept to explore the enactment/portrayal of power (or heteronormative discourse), gender, and assigned roles through the conversational strategies and talk of female-coded and male-coded characters in Mulan. We use the following research questions to anchor our explorations:

-

1.

How are conversational strategies distributed between male-coded and female-coded characters in each version of Mulan, and what can this tell us about power imbalances/heteronormative representations?

-

2.

How are gender and assigned gendered roles construed through male-coded and female-coded talk in each version of Mulan?

-

3.

Are there any noticeable differences between the two versions of Mulan in terms of gender portrayals and gendered roles, and if so, how might these be related to the influence of American and Chinese ideals?

Methods

Research context

The central premise behind most Disney Princess movies involves female-coded characters (“princesses”) being rescued by male-coded characters (“princes”), wherein the story’s resolution is to “live happily ever after” (usually this entails a princess marrying a prince). We chose Mulan as our data source primarily because it does not follow this archetype. Moreover, the character of Mulan is unique in the world of Disney princesses, as she moves between male and female spaces, resisting gender stereotypes as she does so. Thus, we feel that there is increased potential here for scriptwriters to move away from stereotypical portrayals of female-coded characters as affectionate, helpful, and concerned with their appearance (England et al., 2011). Furthermore, Mulan is situated in a real-world context as opposed to a fairytale world, thus we get to see how American filmmakers present traditional Chinese beliefs such as filial piety and the importance of patriarchy to communist power (Evans, 2021). Third, approximately two-thirds of the gross earnings from the most recent version of Mulan (2020) came from China ($40,722,891 USD; Box office, 2020), highlighting the economic rewards of Disney (re)releasing what is essentially a Chinese story.

The first Disney Mulan movie was released in 1998 (animated; henceforth, Mulan-1); the second version was released in 2020 (live-action; henceforth, Mulan-2). Both versions share the same plot, which is based on an ancient Chinese ballad that appeared during the Sui Dynasty (589‒618 AD). There are, however, a number of deviations in Disney’s versions, noticeable among which is the omission of a younger brother in both movies and Mulan’s desire to gain self-worth as a female, which some argue adds an element of Western feminism and romance (Yin, 2011). The main complication in both versions is that Mulan has to disguise herself as a man so that she can join the army and save her father from conscription. However, she is soon revealed as a female, and this causes further complications as only males can be “warriors”. Both movies have ten male-coded characters with speaking roles. Mulan-1 has four female-coded characters with speaking roles (Disney removed Mulan’s older sister, who is present in the original ballad) and Mulan-2 has five (Disney reintroduced Mulan’s sister but made her the younger sibling).

Data collection and preparation

Data consisted of two full-length transcripts based on the movies’ screenplays (Mulan-1’s screenplay was downloaded from https://imsdb.com/scripts/Mulan.html; Mulan-2 from https://subslikescript.com/movie/Mulan-4566758). Mulan-1’s transcript consists of 5423 words, and the movie runs for 1 h 22 min; Mulan-2’s transcript is 4309 words and runs for 1 h 45 min. Both movies were watched in their entirety multiple times by the first researcher, who checked the accuracy of the downloaded screenplays and added speakers’ names and transcription symbols where necessary, thus building up two detailed transcripts (Jefferson’s (2004) transcription system was used as a guide). Transcripts were also divided into sections when the location in the movie changed. This was to facilitate comparisons between the two versions and resulted in approximately thirty scenes for each transcript.

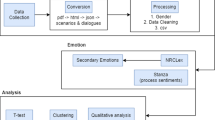

Data coding and analysis

Using inductive content analysis, we isolated stretches of talk that related to our first research question (open codes). The first researcher then further coded these items into six conversational strategies that have been shown to index hegemonic heteronormative discourse in Western populations (Cameron, 2001; Coates, 2003, 2015; Preece, 2009). Namely, commands and directives, compliments, hedges, minimal responses, questions, and tag questions—as we were examining screenplays, which are scripted and rehearsed, we did not code hesitations and pauses. To ensure validity in our coding, we randomly selected 20% of the data for independent coding by the second researcher, who is also a trained linguist. Inter-rater reliability was calculated using Cohen’s kappa. Results showed an excellent agreement (as per Landis and Koch, 1977): Mulan-1: κ = 0.751 (p < 0.0005), 95% CI (0.748, 0.753); Mulan-2: κ = 0762 (p < 0.001), 95% CI (0.759, 0.765).

We then counted male and female conversational strategies, and used inductive content analysis to explore male-coded and female-coded talk, focusing on power imbalances, gendered representations, and societal roles. Results from Mulan-1 and Mulan-2 were then compared and findings interpreted in light of views on gender and assigned gender roles in America and China.

Results

Conversational strategies in Mulan

In Mulan-1, there are 367 conversational turns (4017 words spoken) from male-coded characters and 172 turns (1406 words) from female-coded characters; Mulan-2 contains 213 male-coded conversational turns (2937 words) and 117 female-coded turns (1372 words). Hence, there is a clear power imbalance with regard to the number of conversational turns and overall amount of talk assigned to male-coded characters in each movie, which also reflects the imbalanced number of male-coded to female-coded speaking characters in both movies. However, there is a marked reduction in the overall amount of male-coded talk in Mulan-2.

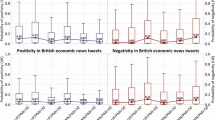

In order to make fairer comparisons between the uses of conversational strategies by gendered characters, we present the frequency of strategies in terms of percentages, as shown in Figs. 1 and 2. The data tables below the figures also display the frequencies of each strategy in parenthesis.

Overall, questions were the most frequent strategy in our dataset (f = 179). Questions typically demand responses. Hence, the person asking questions is often seen as the more powerful interlocutor. Figure 1 shows that the percentage of questions asked by male-coded and female-coded characters is almost equal in Mulan-1. In Mulan-2 (Fig. 2), however, male-coded characters ask more questions than female-coded characters. Coates (2015) proposes that in asymmetrical power situations, the status of interlocutors and purposes of questions should be considered in addition to gender and other affective variables. For example, a higher status speaker may use questions to control the topic of conversation as a lower status speaker is obliged to respond to their line of questioning; alternatively, a lower status speaker may use questions to seek reassurance or permission to keep the current conversation going.

Regarding status and questions, most male-coded characters in Mulan are assigned a position of power in society; conversely, female-coded characters are mostly portrayed as humble villagers. Thus, upon first glance, the increased use of this conversational strategy among male-coded characters may simply be a reflection of their assigned status. Indeed, in Mulan-1, male-coded characters predominantly ask for information relating to war (f = 11) or confirmation of statements (f = 39), which reflect questions being used to enact power. Contrastingly, in Mulan-2, male-coded characters still use questions to ask for information, but instead of confirmation of statements, they more frequently ask for suggestions (f = 8). Similarly, female-coded characters in Mulan-1 tend to ask for help (f = 4) or suggestions (f = 11), reflecting a lower status in conversation that aligns with their lower societal status. Female-coded characters in Mulan-2, however, most frequently ask for others’ opinions (f = 7) and information (f = 8)—asking for opinions is typically seen as a more dominant form of questioning than asking for suggestions, as the speaker asking for an opinion is still controlling the topic of the conversation (Coates, 2015). Hence, with regard to question types that reflect power dynamics in conversation, there appears to be a slight shift in their application in Mulan-2, where less powerful question types are more frequent among male-coded characters, and more powerful question types are more frequent among female-coded characters. In isolation, this small shift in the use of question types is quite unassuming. However, as we argue below, it contributes to a syndrome of features that reflect a markedly different patterning of conversational strategy use by male-coded and female-coded characters across the two movies.

The second most frequent strategy overall was hedges (f = 171). Hedges represent a speaker’s epistemic stance toward a proposition or speech act, such as “I’m sure”, “you know”, “perhaps”, and so on. Figures 1 and 2 show that hedges are more frequent among female-coded characters than male-coded characters in both movies, yet there is a marked increase in their ratio of occurrence in Mulan-2. Specifically, in Mulan-1, 30.21% of all strategies used by female-coded characters were hedges; in Mulan-2, 47.37% of all female-coded strategies were hedges, making them the most frequently used strategy among female-coded characters in Mulan-2. In both movies, Mulan uses hedges to reflect insecurities about being able to hide her gender and her decision to become a warrior in the beginning of the movie. Yet, after completing her training and revealing herself as female, she uses hedges to express confidence in her ability to deal with Shan-Yu (antagonist). Hence, the difference in the use of hedges is found among the supporting female-coded characters.

In Mulan-1, supporting females predominantly use hedges to express confidence with arranged marriages. In Mulan-2, on the other hand, it is only the older female-coded characters who use hedges to express confidence in arranged marriages; the younger female-coded characters (excluding Mulan and Xianniang) use hedges to show a lack of certainty when asked to give opinions on arranged marriages, which is in stark contrast to Mulan-1. Moreover, the younger female-coded characters in Mulan-2 also use hedges to show confidence in their ability to help male-coded characters achieve goals, which is a strategy that is absent in Mulan-1.

Commands and directives were the third most frequent strategy overall (f = 112). These are used to instruct the listener(s) to do what the speaker wants, and thus, if followed, they reflect the speaker’s ability to influence others’ behaviors or actions. Hence, commands and directives are a clear indicator of increased power in interactions. In both versions of Mulan, male-coded characters are predominantly the ones giving commands and directives, and they are thus afforded increased power through this conversational strategy. However, we must also acknowledge that many of these characters are assigned powerful roles (generals, emperors, etc.). Hence, the prevalence of this strategy among male-coded characters may be an epiphenomenon of their roles rather than an (implicit) move to represent male dialogue in a certain way.

The fourth most frequent strategy was minimal responses (f = 60), which refer to response units such as “yeah”, “right”, “mmm”. Minimal responses are a form of supportive feedback, thus they typically indicate cooperation. Frequent deployment of minimal responses is said to be a feature of heteronormative feminine discourse (Coates, 2015; Leaper and Ayres, 2007). In Mulan-1, female-coded characters used proportionately more minimal responses (20.87%) than male-coded characters (12.87%). In Mulan-2, however, there was a marked decrease in the overall ratio of minimal responses for both female-coded (3.6%) and male-coded (3.94%) characters. Although this change could be a reflection of the different actors, production teams, and/or scriptwriters’ styles, it still signals a move away from this particular marker of “feminine” discourse in the later film.

Last, we consider compliments. Although the overall frequency of compliments was the lowest (f = 46), Figs. 1 and 2 clearly show that male-coded characters employ more compliments than female-coded characters in both movies. Interestingly, the only time male-coded characters compliment a female in Mulan-1 is when they are addressing Mulan, and even then it is only after she has done something exceptional, such as single handedly winning a battle or protecting the Emperor (f = 11). Similarly, most of the compliments in Mulan-2 are directed at Mulan for the same reasons (f = 15). In Mulan-2, however, male-coded characters also compliment other female-coded characters besides Mulan. However, they only compliment them on their physical appearance (f = 5). Coates (2015) proposes that this kind of compliment can be a form of sexual harassment even when not intended as such. Accordingly, perhaps the scriptwriters of Mulan-2 have utilized this strategy to add an element of misogyny to some of the male-coded characters.

Overall, while analyzing conversational strategies can shed light on power imbalances, which some scholars see as indexical of “masculine” and “feminine” talk in heteronormative settings (Coates, 2015; Leaper and Ayers, 2007), we also need to consider the content of talk. This is the focus of the next section.

Gender and assigned roles through the content of talk

In many Disney Princess movies, a man and a woman loving each other happily ever after is a common resolution. This central goal—bringing a man and a woman together—reflects the traditional two-gender, heteronormative association promoted in most societies. Accordingly, in many children’s movies, women are portrayed as wives and are associated with subservient domestic roles, and men are portrayed as husbands and framed as providers and the head of the family. This is also evident in Mulan, particularly through the words, “honor” and “dishonor” (Mulan-1: f = 26; Mulan-2: f = 18). In both movies, these words typically collocate with “bring” (Mulan-1: MI = 8.41; Mulan-2: MI = 8.38), “family” (Mulan-1: MI = 5.99; Mulan-2: MI = 5.27), “country” (Mulan-1: MI = 8.31), “fight” (Mulan-2: MI = 5.47), “bride” (Mulan-1: MI = 6.72), and “marriage” (Mulan-2: MI = 8.80). Mutual information (MI) scores indicate the strength of collocations—scores of 3.0 or higher indicate that two words are strongly collocated. Thus, from these measures, we see that males bring honor by protecting the nation; females bring honor through marriage. We now explore these two motifs as they relate to each movie in turn.

Mulan-1

At the start of both movies, Mulan’s parents take her to meet the Matchmaker. When Mulan arrives at the Matchmakers’, the staff and Mulan’s mother attend to Mulan’s appearance while singing the song, “honor to us all”. The song emphasizes that females bring honor to a family through marriage, and its lyrics are peppered with phrases signaling the expected attributes of an ideal bride, as illustrated in Example 1:

Example 1

Mulan-1: Matchmaker’s bathroom [00:06:07.04‒00:09:02.00]

12 | Dressers 1, 2 & Fa Li | you’ll bring honor to us all |

13 | Fa Li + others | a girl can bring her family great honor in one way (.) by striking a good match |

14 | … | |

15 | Dresser 1 | men want girls with good taste |

16 | Dresser 2 | calm |

17 | Fa Li | obedient |

18 | Dresser 1 | who work fast-paced |

19 | Fa Li | With good breeding= |

20 | Dresser 2 | =and a tiny waist |

21 | Mulan | huh. |

… | ||

31 | Everyone | please bring honor to us all |

Example 1 also highlights an unusual phenomenon in Mulan. Namely, female ideals are most often constructed and perpetuated by female characters—although males construct similar female ideals, they do so more crudely, as shown in Example 2:

Example 2

Mulan-1: Training field [00:47:33.29‒00:49:46.19]

1 | Ling | that’s what I said, a girl worth fighting for I want her Paler than the moon with eyes |

3 | Yao | My girl will marvel at my strength, adore my Battle scars |

4 | Po | I couldn't care less what she'll wear or what she looks like (.) it all depends on what |

5 | she cooks like °beef, pork, chicken°... |

A notable phrase in Example 2 occurs in line 1, where Ling says, “I want her Paler than the moon”. This focus on whiter than white skin appears to reflect modern-day Asian notions of beauty, class, and prestige as being associated with white skin (Yip et al., 2019). In addition, beginning in line 4, Po clearly implies that women belong in the kitchen. Later on in this scene, Mulan challenges the males’ views on an ideal female by asking, “How about a girl who’s got a brain? Who always speaks her mind?” to which all four soldiers reply, “nah”. In other words, these males prefer women with no brains and no voice.

In both movies, females are mainly responsible for having sons. For instance, the song, “honor to us all”, explicitly mentions that it is the duty of wives to have sons, which is notable as there is no mention of daughters. This is further highlighted in Example 3 (below), wherein the Matchmaker evaluates Mulan’s ability to be a good wife and bear “sons” (line 1).

Example 3

Mulan-1: Matchmaker’s place [00:09:16.22‒00:11:29.22]

1 | Matchmaker | huh, hmm, <too> skinny (.) hmph, not good for bearing sons (.) |

2 | Mulan | mmm hmm |

… | ||

7 | Matchmaker | now, pour the tea (.) to please your future in-laws you must demonstrate a |

8 | sense of you must also be ºpoisedº | |

9 | Mulan | °um, pardon me° |

10 | Matchmaker | AND SILENT |

Moreover, in line 7 above, the Matchmaker implies that wives are indentured to their in-laws as well as their husbands, and that they must be “silent” in the presence of them (line 10). Example 3 clearly illustrates the dominance of the Matchmaker (older woman) over Mulan (younger woman) in the conversation, as Mulan rarely takes the floor when given opportunities to do so. Moreover, even when she speaks softly (line 9), the Matchmaker quickly rebukes her (line 10). Somewhat more interesting, however, is that immediately after this scene, Mulan returns home and says, “Look at me I will never pass for a perfect bride or a perfect daughter”. This statement not only implies that to be a perfect daughter, Mulan thinks she must also be a perfect bride, but also illustrates her alignment with the Confucius belief of filial piety. Filial piety is the virtue of paying respect to your parents and ancestors through familial servitude, and this is yet another common thread throughout both movies. In fact, this is the central driving force behind the story, as Mulan only enlists in the army to save her father.

Example 4 (below) is much later in Mulan-1, yet it is a prime example of how, despite being the hero in both movies, Mulan rarely has the dominant role in conversation. In this extract, she tries to tell people about the Huns’s invasion, but no one listens to her (in line 2, she even says, “no one will listen”). Mushu, who sets himself on an equal footing with Mulan when there is no one else around, initially pretends not to hear her (line 3) before reminding her that she is a girl and, thus, no one will listen to her (line 5).

Example 4

Mulan-1: The palace [01:08:10.18‒01:08:27.05]

1 | Mulan | sir (.) the emperor’s in danger but the huns are here (.) please you have to help me. |

2 | no one will listen. | |

3 | Mushu | huh oh, I’m sorry, did you say something |

4 | Mulan | Mushu |

5 | Mushu | hey, you’re a girl again, remember |

A more explicit example of negative conceptions toward Mulan as a female can be seen in Example 5:

Example 5

Mulan-1: The palace [01:15:20.10‒01:18:50.07]

1 | Chi Fu | stand aside that creature’s not <worth protecting> |

2 | Shang | she’s a hero |

3 | Chi Fu | this woman she will never be worth <anything> |

Here, we see that even though Mulan has saved the Emperor, Chi Fu (the chancellor) heavily denigrates Mulan by first dehumanizing her (line 1), and then explicitly referring to her gender and devaluing her existence (line 3).

Mulan-2

Mulan-2 also portrays females as dutifully fulfilling the roles of bride-to-be, wife, and/or mother. All of which are the only ways for daughters to bring “honor” to their families. In terms of being a mother, Mulan-2 most frequently frames women as mothers through the eyes of their sons (soldiers). For example, when one male character first enters the army camp, he introduces himself as follows: “I’m Cricket. My mother says I was born under an auspicious moon. That is why my mother says I’m a good luck charm” (00:29:02.24). Similarly, just before going to war, Yao says to the soldiers, “Anything you want me to tell your mothers when you die?” (00:53:08.15).

As per Mulan-1, Mulan-2 also construct an ideal female through the eyes of females, particularly the Matchmaker. Example 6 is a mirrored extract from the one in Example 3, although it occurs some seven minutes later in Mulan-2.

Example 6

Mulan-2: Matchmaker’s place [00:16:29.19‒00:18:51.40]

1 | Matchmaker | quiet (.) composed (.) graceful (.) elegant (.) poised (.) °polite° <these are the |

2 | qualities (.) we see in a good wife > (.) When a wife serves her husband (.) °she | |

3 | must be silent° she must be (.) °invisible°… IS SOMETHING WRONG | |

4 | Mulan | no madam matchmaker thank you. |

As in Mulan-1, Example 6 shows the Matchmaker’s dominance over her audience: When she slowly talks, no one interrupts her. Moreover, as per Example 3, she emphasizes that women have to serve men without conditions, and that they “must be silent … invisible” (lines 2 and 3).

An example of how the ideal female is constructed by males in Mulan-2 can be seen in Example 7.

Example 7

Mulan-2: The army camp [00:36:52.19‒00:38:04.05]

1 | Ling | her skin is white as milk (.) her fingers like the tender white roots of a green onion= |

… | ||

5 | Yao | =I like my women buxom. <with strong, WIDE HIPS > |

6 | Cricket | I like kissing women with cherry red lips. |

7 | Po | I don’t care what she looks like. |

8 | Mulan | I agree. |

9 | Po | I care what she COOKS like. |

Example 7 (above) starts with Ling describing his bride to be with “skin as white as milk” (line 1), with misogynistic comments interjected by both Yao (line 5) and Cricket (line 6). In both versions of Mulan, the issue of light skin as a marker of beauty comes up, only in Mulan-2 there are two explicit references to “white” skin tone being the ideal in line 1 (see Example 2 for the equivalent scene in Mulan-1). Notable in this example, though, is that Po seems to be the only male not fixated with appearance, yet this positivity is soon negated when he goes on to place females in the kitchen (as he did in Mulan-1). However, a marked difference at the end of this scene (as opposed to Mulan-1) is that Mulan gives more specific details about her ideal woman, all of which focus on psychological traits. Specifically, when asked what her ideal woman is, she states that she must be courageous, smart, and have a sense of humor. However, there is also no mention of a female being given a voice as there was in Mulan-1.

Another notable difference in Mulan-2 is the introduction of chi (special ability or spirit), and it subsequently becomes a recurring theme that females are not allowed to possess it. For example, Mulan’s father tells her, “Your chi is strong, Mulan. However, chi is for warriors…not daughters. Soon, you’ll be a young woman and it is time for you…to hide your gift away to (.) to silence its voice” (00:04:43.04). In fact, Mulan-2 even begins with Mulan’s father asking his ancestors for advice about his daughter’s chi: “If you had such a daughter…her chi, the boundless energy of life itself…speaking through her every motion…could you tell her that only a son could wield chi? That a daughter would risk shame, dishonor, exile? Ancestors, I could not” (00:01:00‒00:01:25). At times, Mulan even appears to accept this societal expectation by hiding her chi. She even chastises herself when she forgets to hide it in one scene: “You idiot. Now everyone sees it. You must hide your chi!” (00:39:26).

In addition to the fact that chi can only belong to males, on the rare occasion when males applaud Mulan or Xianniang (female deuteragonist) for being brave, strong, and “useful”, these compliments are quickly negated through rebukes that contain pejorative terms, such as “witch” (f = 13).

Example 8

Mulan-2: Bori Khan’s army camp [00:12:27.02‒00:13:25.08]

3 | Khan | you have proved useful, WITCH. |

4 | Xianniang | NOT WITCH. warrior. °I could tear you to pieces before you blink°= |

5 | Khan | =but you won’t (.) remember what you want (.) a place >where your powers will not |

6 | be vilified< a place >where you are accepted for who you are < °you won’t get what | |

7 | you want without me° (.) when I found you (.) you were exiled A SCORNED DOG. | |

8 | when I sit on the throne, that dog will have a home. |

In Example 8, Xianniang explicitly challenges Khan (the leader of the Huns) by raising her voice and then confidently stating, “I could tear you to pieces before you blink” (line 4). However, Khan is unfazed by her show of rebellion and repeatedly derides her, even calling her “a scorned dog” (line 7) and stating, “that dog will have a home” (line 8). These statements clearly dehumanize Xianniang in the same way as Mulan was in Example 5 (Mulan-1).

However, while males appear misogynistic and domineering, Mulan-2 also portrays them as weak, since they often need females’ help, as shown in Example 9.

Example 9

Mulan-2: Khan’s camp [00:43:48.03‒00:45:19.24]

1 | Khan | soon the imperial city will be ours. |

2 | Khan’s soldiers | but we’re relying on a witch (.) yes a witch a witch cannot be trusted she is no threat. |

3 | Khan | HUSH ENOUGH make no mistake… the witch serves me … all of us she knows |

4 | who °her master is° |

Once more, in Example 9, we see the pejorative term “witch”, yet Xianniang is also portrayed as being the property of all males (lines 3 and 4). However, we see a vast difference in how Mulan’s abilities are received at the end of both movies. In the end, Mulan is framed very positively by the emperor and is granted freedom to do whatever she wishes (i.e., the resolution of the story has begun).

Discussion

Male and female portrayals through talk

We begin this section by considering the portrayal of males in both Mulan movies. Lewis (2021) states that men’s honor is historically associated with being warriors, which is typically achieved through militancy on the battlefield. In modern times, this socio-historical expectation is often realized in terms of protective paternalism (Glick & Fiske, 1996). Protective paternalism refers to the idea that women need to be protected because they are weaker than men are. Aside from the feats of Mulan and Xianniang—who are still in the service of men—this is manifest quite explicitly in Mulan, as several of the male characters are given domineering roles, such as emperor, commander, and the father in a family of females.

Supporting this claim of patriarchal dominance in Mulan is the fact that commands, directives, and compliments are more frequent among male-coded characters than female-coded characters in both movies. Moreover, male-coded characters frequently interrupt and raise their voices when talking to others, whereas female-coded characters rarely shout at or interrupt others. Effectively, such conversational strategies help male-coded characters index heteronormative masculinity through their verbal interactions with others. Moreover, male-coded characters in both movies only compliment Mulan when she is performing as a soldier—the other females never receive compliments. For example, in Mulan-1, Shang says to Mulan, “you are the craziest man I’ve ever met, and for that I owe you my life” (00:59:05.00). Similarly, Ling remarks that Mulan is “The bravest of us all” (00:59:17.10), and Yao states, “You’re king of the mountain” (00:59:21.10). After Mulan wins Shan-Yu and saves the emperor successfully, Shang says, “She’s a hero” (01:15:31.10) and “You fight good” (01:18:03.04), highlighting that these types of compliments are not dependent on the gender of Mulan but on her role.

Furthermore, we see numerous examples of misogynistic language in male-coded to female-coded dialog in both movies. For instance, the term “witch” occurs 13 times in Mulan-2. While some may argue that this term implies a female with magical powers, there are well-known negative preconceptions attached to this word (numerous dictionary definitions collocate the term with “evil”, for example). Moreover, other word choices could easily have been made in such scenes, such as “sorceress”, which has connotations that are clearly more positive.

With regard to female portrayals in Mulan, it seems fitting to begin with the end, as the resolution of both films portrays the inherent contradiction in Disney’s Mulan. Throughout the movie, Mulan battles to overcome societal expectations, and is eventually acknowledged as a powerful warrior that has no equal (male or female). In the final scene of Mulan-2, for example, the emperor offers Mulan a position as an officer in his guard—a position traditionally reserved for males. Mulan politely refuses. At first glance, this exchange suggests that Mulan has the power to do what she wants, as opposed to the beginning of the movie. Effectively, through her achievements, she has broken free of the confines of societal expectations. However, she chooses to return to her village and devote herself to her family. Hence, the ultimate resolution is that she willingly aligns with what Yin (2006) terms Confucian feminism, which is an orientation to relationalism, filial piety, and loyalty through humanness (ren), share (fen), and duty-based ethics. In other words, her feats of bravery were mainly for the benefit of her father, and herein lies the ultimate patriarchal servitude in Mulan.

This patriarchal servitude is also evident in the roles that women are assigned, and, for the most part, willingly accept: Key among them is that women bring “honor” through marriage. This ideal is partly constructed by male-coded characters’ talk, wherein the ideal woman exists to serve males’ desires and needs, yet it is most explicitly perpetuated through the talk of the supporting female-coded characters. There is, thus, a kind of double layering of gendered power: Male-coded characters frame female-coded characters as objects that they will be surely given, while female-coded characters reinforce these ideals by positioning their core identities around roles related to arranged marriages. These roles being Matchmaker, a mother who is fixated on her daughter(s) becoming a bride, and dutiful (supporting) daughters, all of whom who decry “bring honor us to all” while espousing the “ideal” female as calm, obedient, silent, and invisible. Although these ideals are clearly rooted in the socio-historical backdrop of the Mulan story, we question why it is that modern moviemakers feel the need to stick so rigidly to such an explicit patriarchal realization, where women without “chi” are framed as inferior (as discussed in the next section).

Furthermore, both movies frequently present negative preconceptions toward women. For instance, we see frequent references to what females say as being hard to believe, dehumanizing statements by male-coded characters, and female-coded characters only being recognized as “useful” when they achieve something remarkable. These preconceptions can be related indirectly to sexism through the presuppositions they contain. For example, there is a strong presupposition in Mulan that having daughters is problematic. In many cultures, this “problem” is rooted in the belief that once daughters are old enough, they are sent off to be married and subsequently live the rest of their lives in servitude of their husband and his family. Essentially, daughters are seen as financial burdens to their families. In other words, once they reach working age, daughters leave their families and take any potential future earnings or benefits with them. Moreover, sons can continue on the family surname, which is a form of overt sexism, as women traditionally adopt their husbands’ surname when they get married, and any children they have are typically given the father’s surname. Such “disadvantages” effectively gave rise to the cultural phenomenon known as son preference. The son preference presupposition can be seen in both Mulan movies, yet, in Mulan-1, it is somewhat more explicit as several characters refer to the act of bearing a son (not daughter).

Differences between Mulan-1 and Mulan-2

Before we consider the differences between the two versions of Mulan, it is important to note that the overall portrayal of males and females in both movies mirrors the current stance of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and Chinese media on gender roles (Evans, 2021; Fincher, 2018). Namely, males should be masculine and assume patriarchal roles, and females should be feminine and assume matriarchal roles such as wife, mother, and/or daughter-in-law (Brady, 2009). While, such portrayals reflect much of the original story’s characterizations, Disney’s modern version of Mulan also seems to align with a political narrative that is often attributed to the CCP—namely, that the oppression of women is a means to maintain patriarchal authoritarianism in politics (see Fincher, 2018; Howell, 2002). For instance, in Mulan-2, Mulan falls in love with her superior; thus, despite Mulan being the hero, the archetypal plot of women falling in love with a more powerful man still reverberates (Banh, 2020). Moreover, although it is not evident from our data, Disney delayed the original production of the film under criticisms of “white washing”, as they were originally going to add a European male as the protagonist. Although, it is not clear if Disney folded due to international or domestic pressures (Banh, 2020), the company was criticized for acknowledging the support of several Chinese propaganda institutions in the film’s credits (Fish, 2020). Moreover, the choice to film at Xinjiang raised serious concerns about Disney’s decision to overlook alleged human rights violations and invited widespread criticism of the company (Ramzy, 2022).

With regard to noticeable differences between the movies, there appears to be several changes in Mulan-2 that could have been made to align with the reported policies of the CCP. Notably, the reintroduction of Xiu (Mulan’s sister) may have been implemented to reflect the change in China’s one-child policy to a two-child one in January 2016 (Cai and Feng, 2021). Furthermore, Xiu is proud to be matched (in opposition to Mulan), and happily conforms to societal expectations concerning arranged marriages and female roles. More interestingly though, Xiu is born without chi (unlike Mulan). Hence, we believe that Xiu may have been (re)introduced into the newer Mulan for two reasons: (a) to promote the current two-child policy in China; (b) to imply that women who are born with no special abilities or gifts (chi) have no choice but to conform to societally expected roles. Fundamentally, the concept of chi may be a means by which to allow exceptionally gifted females to operate outside societal norms in modern-day China; in other words, if a female displays chi at a young age, then she can put it to work serving the state. If a female has no chi, then she must become a dutiful wife and serve her husband.

There also seems to be influential changes in Mulan-2 to align with the American market. Specifically, in Mulan-1, young female characters are portrayed as blindly obedient, while, in Mulan-2, they are portrayed as somewhat stronger and more independent (i.e., traits traditionally ascribed to male characters in Disney films [England et al., 2011]). Specifically, females in Mulan-2 take on more strategies that are typically indexical of “masculine” conversation (Coates, 2015), such as a marked decrease in the use of minimal responses, which signals a decrease in cooperative talk in general. In Mulan-2, there is also a noticeable increase in the ratio of hedges used, as well as how they are used. Specifically, in Mulan-2, older female-coded characters still use hedges to express confidence in arranged marriages as per Mulan-1. However, in contrast to Mulan-1, Mulan-2’s younger female-coded characters show a marked increase in the overall ratio of hedges used, wherein the predominant function of these hedges has shifted from showing confidence in arranged marriages to (a) showing uncertainty in arranged marriages, and (b) reassuring male-coded characters. Hence, in Mulan-2 there is a subtle shift away from female-coded characters blindly accepting arranged marriages, as well as a slight overall presupposition that male-coded characters need female-coded characters help.

There are also clear differences in the use of conversational strategies and amount of talk assigned to male-coded characters across the two movies. Namely, in Mulan-2, male-coded characters exhibit fewer domineering strategies in conversation and experience a marked decrease in the amount of conversational turns and overall talk. More specifically, even though male-coded characters in Mulan-2 have the assigned status and associated power to command and question others, the content of such talk is often not to give directives or ask for confirmations (as is the predominant function in Mulan-1), but it is more often used to seek help. Traditionally, needing help, seeking it, and then accepting it is considered a more feminine characteristic (England et al., 2011). This suggests a more balanced footing in Mulan-2 than Mulan-1, as male-coded characters appear to need more assistance, especially from female-coded characters.

Furthermore, male-coded characters are seemingly portrayed as more aggressive and physically stronger in Mulan-1 through their word choices than they are in Mulan-2. For example, Yao says “Oooo tough guy” when he sees Shang’s body (Mulan-1, 00:36:47.15), and Shang says “Did they send me daughters when I asked for sons?” (Mulan-1, 00:38:10.10), when he is talking to the trainees. More interestingly, though, Mulan-1 represents these traits as societal norms for males, since Mulan is taught that if she behaves aggressively and has a strong physical presence, people will think that she is male. For instance, Mushu tells Mulan to “punch him. It’s how men say hello.” (Mulan-1, 00:29:50.22), and “Now slap him on the behind. They like that.” (00:29:57.10). In a later scene, Mulan screams “Rrrrrrrr” (00:35:43.28), to which Mushu replies “Oh, that’s my tough looking warrior. That’s what I’m talking about.” (00:35:45.03). this kind of language is notably absent in Mulan-2.

Overall, this subtle “feminization” and decrease in the amount of overall male dialogue, when combined with the increased amount of “masculized” female talk, arguably contributes to lessening the power differential between male-coded and female-coded characters’ talk in Mulan-2, without significantly altering the overarching narrative found in Mulan-1. Such changes may have been influenced by the continual progress being made by the women’s movement in the United States (Chamberlain, 2017), and add to discussions surrounding the changing nature of masculinity and femininity in Disney films (Macaluso, 2018; Primo, 2018). Nevertheless, we feel that these changes were minimal at best, and thus the overall inequality between male and female talk found in Mulan-1 persists in Mulan-2. Moreover, when combined with the decidedly patriarchal nature of the overarching narrative, neither version of Disney’s Mulan is particularly inspirational for young females.

Conclusion

We explored the portrayals of gender, power, and assigned gender roles in two versions of Mulan through the analysis of conversational strategies and content of talk. As such, we believe the study has contributed to research into representations of gender and gendered roles in children’s media, female‒male discourse in the media, and film in general, and that it has done so in light of the growing influence of China on American-made media.

In terms of gendered representations through talk, we highlighted how older female-coded characters were portrayed similarly in both movies and conformed to traditional societal expectations. Namely, being a wife and mother is the only way to bring honor to a family; this also entails keeping up physical appearances and showing good etiquette in the service of a husband and his family. Contrastingly, we showed how younger female-coded characters are portrayed differently in each movie. In Mulan-1, younger female-coded characters are seen as obedient, whereas in Mulan-2, younger female-coded characters, particularly Mulan and Xianniang, are portrayed as more independent and use less “femininised” features of talk. Moreover, the portrayal of male-coded characters was also slightly different between the movies. We argued that these differences signal positive developments in the representation of genders in the newer Mulan, wherein the power distance between male-coded and female-coded characters has lessened. In this light, we have contributed to the field of conversational dominance and gendered discourse by examining how the content of female–male talk can be used positively and negatively, while also adding to the growing number of studies that reflect the changing nature of femininity and masculinity in Disney movies (e.g., Macaluso, 2018; Primo, 2018).

Second, by comparing the two movies in terms of content of talk and representation of gendered roles in general, we explored how the writers of Mulan-2 were able to empower some female-coded characters while dis-empowering some male-coded characters; this was despite the confines of the original plot structure and overarching narrative. However, we also argued that by foregrounding Mulan and Xianniang’s chi (special ability), they seem to have inadvertently negated this positive development by setting up a dichotomy of “special” women versus “ordinary” women, wherein the latter happily assume their designated place within a patriarchal system. In other words, to break free of traditional societal expectations that women can only be wives and mothers, a woman must be imbued with some form of magical “chi” at birth. This is evident in the addition of Mulan’s sister (Xiu) in Mulan-2: She is portrayed as an ordinary woman with no special ability, and her main “achievement” at the end is being matched for marriage.

Third, by situating our interpretations within the wider socio-historical context of increased globalization, we argued that Mulan-2 shows some indication of reflecting the influential desires of the CCP, whereby traditional female roles in China (i.e., mothers and wives) are encouraged through media portrayals (Evans, 2021) and as a means to maintain the CCP’s patriarchal dominance (Fincher, 2018). In this light, the study is one of the first, if not the first, to explore the potential impact of an outside market on gender portrayals in American-made media.

The study has a number of limitations. First, we only investigated one story, set in China, and made in America. Moreover, we only focused on the English language versions. However, we feel that such a focus allowed us to explore potential connections between the evolution of a single story and the influences of two of the world’s superpowers. Nevertheless, future studies may wish to examine how Mulan is presented in the Chinese language or explore other Disney films that have been remade in recent years. Second, the study predominantly focused on talk and the content of talk. There are, of course, many other meaning-making modalities in film, such as visuals, music, cinematography, etc. Moreover, Disney’s Mulan is presented in many formats, such as children’s books and movie posters. Thus, anyone wishing to examine the production and consumption of Mulan as a franchise would do well to extend into these areas.

Overall, we believe that with the continued influence of the Chinese market on American media, and the seemingly inevitable shift in world power structures in the near future, investigations of gender and assigned gender roles in globally disseminated discourse and media has only just begun.

Data availability

The underlying data are freely available for inspection upon request.

References

Aley M, Hahn L (2020) The powerful male hero: a content analysis of gender representation in posters for children’s animated movies. Sex Roles 83:499–509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01127-z

Anderson DA, Hamilton M (2005) Gender role stereotyping of parents in children’s picture books: the invisible father. Sex Roles 52(3):145–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-1290-8

Auster CJ, Mansbach CS (2012) The gender marketing of toys: an analysis of color and type of toy on the Disney store website. Sex Roles 67(7):375–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-012-0177-8

Baker K, Raney AA (2007) Equally super?: gender-role stereotyping of superheroes in children’s animated programs. Mass Commun Soc 10(1):25–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205430709337003

Baker-Sperry L (2007) The production of meaning through peer interaction: Children and Walt Disney’s Cinderella. Sex Roles 56(11):717–727. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9236-y

Banh J (2020) #MakeMulanRight: Retracing the genealogy of Mulan from ancient Chinese tale to Disney classic. In: Roberts S (ed.) Recasting the Disney Princess in an era of new media and social movements. Lexington Books, pp. 147–161

Box office (2020) Mulan. https://www.boxofficemojo.com/title/tt4566758/?ref_=bo_tt_tab#tabs. Accessed 20 Nov 2020

Brady AM (2009) Mass persuasion as a means of legitimation and China’s popular authoritarianism. Am Behav Sci 53(3):434–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764209338802

Cai Y, Feng W (2021) The social and sociological consequences of China’s one-child policy. Ann Rev Sociol 47(1):587–606. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-090220-032839

Cameron D (2001) Working with spoken discourse. SAGE, London

Chamberlain P (2017) The feminist fourth wave affective temporality. Springer International Publishing

Chepinchikj N, Thompson C (2016) Analysing cinematic discourse using conversation analysis. Discourse Context Media 14:40–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2016.09.001

Clark T (2021) The top 10 movies at the China Box Office this year show how its rebound has been driven by local productions. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/highest-grossing-movies-at-china-box-office-2021-11. Accessed 1 Dec 2021

Coates J (2003) Men talk: stories in the making of masculinities. Blackwell

Coates J (2015) Women, men and language: a sociolinguistic account of gender differences in language, 3rd edn. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315835778

Coyne SM, Linder JR, Rasmussen EE et al. (2016) Pretty as a princess: Longitudinal effects of engagement with Disney princesses on gender stereotypes, body esteem, and prosocial behavior in children. Child Dev 87(6):1909–1925. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12569

Douglas S, Tang L, Rice C (2022) Gender Performativity and Postfeminist Parenting in Children’s Television Shows. Sex Roles. 1‒14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-021-01268-9

England DE, Descartes L, Collier-Meek MA (2011) Gender role portrayal and the Disney princesses. Sex Roles 64:555–567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9930-7

Evans H (2021) “Patchy patriarchy” and the shifting fortunes of the CCP’s promise of gender equality since 1921. The China Quarterly. 1‒21. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0305741021000709

Fincher LH (2018) Betraying big brother: the feminist awakening in China. Verso

Fish IS (2020) Opinion | why Disney’s new ‘Mulan’ is a scandal. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/09/07/why-disneys-new-mulan-is-scandal/. Accessed 29 May 2022

Fletcher JK (2001) Disappearing acts. Gender, power, and relational practice at work. MIT Press

Gamble TK, Gamble MW (2020) The gender communication connection, 3rd ed. Routledge, London, 10.4324/9780367822323-1

Gillam K, Wooden SR (2008) Post-princess models of gender: the new man in Disney/Pixar. J Pop Film Telev 36(1):2–8. https://doi.org/10.3200/JPFT.36.1.2-8

Glick P, Fiske ST (1996) The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. J Pers Soc Psychol 70(3):491–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491

Golden JC, Jacoby JW (2018) Playing princess: preschool girls’ interpretations of gender stereotypes in Disney princess media. Sex Roles 79:299–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0773-8

Granger KL, Hanish LD, Kornienko O et al. (2016) Preschool teachers’ facilitation of gender-typed and gender-neutral activities during free play. Sex Roles 76(7‒8):498–510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0675-1

Hardin M, Greer JD (2009) The influence of gender-role socialization, media use and sports participation on perceptions of gender-appropriate sports. J Sport Behav 32(2):207–226

Hazenberg E (2016) Walking the straight and narrow: linguistic choice and gendered presentation. Gend Lang 10(2):270–294. https://doi.org/10.1558/genl.v10i2.19812

Hearn J, Morrell R (2012) Reviewing hegemonic masculinities and men in Sweden and South Africa. Men Masc 15(1):3–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X11432111

Hentges B, Case K (2013) Gender representations on Disney channel, Cartoon Network, and Nickelodeon broadcasts in the United States. J Child Media 7(3):319–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2012.729150

Hine B, Ivanovic K, England D (2018) From the sleeping princess to the world-saving daughter of the chief: Examining young children’s perceptions of ‘old’ versus ‘new’ Disney princess characters. Soc Sci 7(9):161. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7090161

Holmes J, Marra M (2004) Relational practice in the workplace: Women’s talk or gendered discourse? Lang Soc 33(3):377–398. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404504043039

Holmes J, Schnurr S (2006) ‘Doing femininity’ at work: more than just relational practice. J Sociolinguist 10(1):31–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-6441.2006.00316.x

Howell J (2002) Women’s political participation in China: struggling to hold up half the sky. Parliam Aff 55(1):43–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/parlij/55.1.43

Jefferson G (2004) Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In: Lerner GH (ed.) Conversation analysis: studies from the first generation. John Benjamins, pp. 13‒31

Jones JJ (2016) Talk “like a man”: The linguistic styles of Hilary Clinton, 1992‒2013. Perspect Polit 14(3):625–642. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1537592716001092

Kiesling SF (1997) Power and the language of men. In: Johnson S, Meinhof UH (eds.) Language and masculinity, Blackwell, pp. 65‒85

Kiesling SF (2002) Playing the straight man: displaying and maintaining male heterosexuality in discourse. In: Campbell-Kibler K, Podesva R, Roberts S, Wong A (eds.) Language and sexuality: Contesting meaning in theory and practice, CSLI Publications, pp. 249‒266

Lakoff R (1975) Language and women’s place. Harper and Row

Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33(1):159–174. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529310

Leaper C (2019) Young adults’ conversational strategies during negotiation and self-disclosure in same-gender and mixed-gender friendships. Sex Roles 81(9-10):561–575. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-1014-0

Leaper C, Ayres MM (2007) A meta-analytic review of gender variations in adults’ language use: Talkativeness, affiliative speech, and assertive speech. Person Soc Psychol Rev 11(4):328–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868307302221

Leaper C, Breed L, Hoffman L et al. (2002) Variations in the gender stereotyped content of children’s television cartoons across genres. J Appl Soc Psychol 32(8):1653–1662. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb02767.x

Lewis ME (2021) Honor and shame in early China. Cambridge University Press

Li H, Liu H, Liu D (2022) Gender/power relationships in fictional conflict talk at the workplace: Analyzing television dramatic dialogue in the newsroom. J Pragmat 187:58–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2021.10.030

Macaluso M (2018) Postfeminist masculinity: the new Disney norm? Soc Sci 7(11):221. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7110221

Newman ML, Groom CJ, Handelman LD et al. (2008) Gender differences in language use: an analysis of 14,000 text samples. Discourse Process 45(3):211–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/01638530802073712

Onyenankeya KU, Onyenankeya OM, Osunkunle O (2019) Sexism and gender profiling: two decades of stereotypical portrayal of women in Nollywood films. J Int Women’s Stud 20(2):73–90

Pearce AM (2016) Exploring performance of gendered identities through language in World of Warcraft. Int J Hum‒Comput Interact 33(3):180–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2016.1230965

Preece S (2009) ‘A group of lads, innit?’: Performances of laddish masculinity in British higher education, In: Eppler E, Pichler P (eds) Gender and spoken interaction, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 115‒138

Primo C (2018) Balancing gender and power: how Disney’s Hercules fails to go the distance. Soc Sci 7(11):240. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7110240

Ramzy A (2022) U.N. Human rights chief tempers criticism at end of China trip. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/28/world/asia/un-human-rights-china.html. Accessed 29 May 2022

Raymond CW (2013) Gender and sexuality in animated television sitcom interaction. Discourse Commun 7(2):199–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481312472971

Rice C (2014) Becoming women: The embodied self in image culture: University of Toronto Press

Schippers M (2007) ‘Recovering the feminine other: masculinity, femininity, and gender hegemony’. Theory Soc 36(1):85–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-007-9022-4

Streiff M, Dundes L (2017a) From shapeshifter to lava monster: Gender stereotypes in Disney’s Moana. Soc Sci 6:91. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6030091

Streiff M, Dundes L (2017b) Frozen in time: how Disney gender-stereotypes its most powerful princess. Soc Sci 6(2):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6020038

Stubbe M (2013) Active listening in conversation: Gender and the use of verbal feedback. In Approaching language variation through corpora: a festschrift in honour of Toshio Saito, Peter Lang, pp. 367‒416

Thompson TL, Zerbinos E (1995) Gender roles in animated cartoons: Has the picture changed in 20 years? Sex roles 32(9):651–673

Ward LM, Aubrey JS (2017) Watching gender: how stereotypes in movies and on TV impact kids’ development. Common Sense Media, CA, San Francisco, https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/watching-gender

Yang S (2020) Hollywood executive reveals how China’s politics have shaped movie industry. VOA News. https://www.voanews.com/a/east-asia-pacific_voa-news-china_hollywood-executive-reveals-how-chinas-politics-have-shaped-movie/6197191.html. Accessed 16 Nov 2020

Yin J (2006) Toward a Confucian feminism: a critique of Eurocentric feminist discourse. China Media Res 2:3

Yin J (2011) Popular culture and public imaginary: Disney vs. Chinese stories of Mulan. Javnost-The Public 18(1):53–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2011.11009051

Yip J, Ainsworth S, Hugh MT (2019) Beyond whiteness: perspectives on the rise of the Pan-Asian beauty ideal. In: Race in the marketplace: crossing critical boundaries, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 73‒85

Yoong M (2018) Language, gender and sexuality. In: Seargeant P, Hewings A, Pihlaja S (eds.) Routledge handbook of English language studies. Routledge, London, pp. 226–239

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study is exempt from ethics approval as it does not involve any participants.

Informed consent

Informed consent is not applicable as there were no human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Manaworapong, P., Bowen, N.E.J.A. Language, gender, and patriarchy in Mulan: a diachronic analysis of a Disney Princess movie. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9, 224 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01244-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01244-y

This article is cited by

-

Women’s Revolution, a Revolution in Progress: Gender Representation in Children’s Literature Through Raquel Costa’s 25 Mulheres

Children's Literature in Education (2025)