Abstract

The paper aims to investigate how a Chinese heroic legend was reconfigured for Western viewers through the English-dubbed versions of a case-study film, Monkey King: Hero is Back (2015). The ultimate goal of the study is to shed new light on how dubbing practice may better cater to Western target audiences. Based on two macrolevel translation theories, three translation models, and the two microlevel translation strategies, this paper discusses the most commonly used film translation strategies for English dubbing in the case-study film and their implications for the effectiveness of translation. The findings suggest that driven by the target-audience orientation, English-dubbing strategies often use standard language constrained by linguistic and cultural disparities as opposed to dynamic, adaptive Chinese dubbing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The year 2015 saw the release of Monkey King: Hero Is Back (2015) (henceforth Monkey King) in the Chinese mainland. Shortly after its debut, Monkey King reached the top of the charts for animated films in box offices in China and then 2 weeks later, in box offices worldwide (DW.com, 2015), with an accumulated box-office return of 956 million yuan (Ku, 2015). It was appraised by the Publicity Department of the Central Committee of the CPC and the State Administration of Radio and Television (SART) of the People’s Republic of China as “a milestone in domestic animated film production” (Jiang and Huang, 2017, p. 123). The success of this film reflects the participation of Chinese audiences in making it “a new all-time animation box-office champ” (ibid., 122) because of their enthusiasm for the film and patriotism for their country (ibid., 128). Part of its appeal to Chinese viewers could be attributed to the use of the technology of Hollywood animation films to present the traditional story of Journey to the West (1592) and the application of Chinese elements throughout the whole film production (Fang et al., 2019, p. 145).

The case-study film is adapted from a classic Chinese mythological novel written during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) by Wu Cheng’en (吴承恩) (Wu, 1592). It consists of 100 chapters based on traditional folktales telling the adventures of the real historical exploits of a monk from the Tang Dynasty (618–907) who travelled to India and back. The journey is led by a priest, Sanzang, and his three disciples, Monkey, Pigsy and Friar Sandy, as they travel west, overcoming many dangers in pursuit of Buddhist Sutra (Wu and Jenner, 2003).

This paper will explore how a Chinese heroic legend is adapted to the West by mainly focusing on the English-dubbed version of the film Monkey King, with the originally released Chinese-dubbed version as the source text. The two monolingual corpora of Chinese and English dialogues in two dubbed versions, including both trailers, helped us pinpoint the typical linguistic and cultural features of filmic texts through comparison. The present research will focus on key norms and idiosyncratic language of the dubbed version in English. The rationale for the choice of these features as objects of study is twofold: “their importance in real conversation” and their “key role in providing fictional dialogue, and especially dubbing dialogue, with naturalness” (Fresco 2009, p. 60). Nonetheless, although Chinese viewers go crazy for this film, as evidenced by its remarkable box-office success, scarce statistics have been found on the Western counterpart concerning its reception in the Western context. This paper addresses the following research questions: (1) What changes are made to reconfigure a Chinese superhero through the English-dubbed version of Monkey King compared to the Chinese-dubbed version? (2) What are the study’s practical and theoretical contributions to Audio-visual Translation Studies (AVT)?

Contextualising Monkey King in the West

The dubbed English version was released on American streaming sites first and then in cinemas one year later than the original Chinese-dubbed version (Wang and Li, 2020, p. 91). The “humanised” Monkey King made the film widely appealing to audiences from both the West and China. The director of the film, Xiaopeng Tian, also confirmed that the film is all about humanity (ibid., 91; Li, 2015). Apart from the topic of humaneness that was interesting to both Chinese and Western audiences and the positive reception overall, the fantastical action and imagery proved to be particularly successful in the West, as reported by IMDb (Internet Movie Database). Monkey King became one of the world’s most famous movies, cited even in television episode databases, which U.S. viewers favourably rated 6.8 out of 10. Here are some top comments, as voted up by site visitors, collected from IMDb that support its popularity in the West: “smooth special effects and full 3D sense” (yoggwork), “vibrant, colourful and fast, with some amazingly innovative, original animated images” (mmthos), “the scenery and battles are epic” (BabelAlexandria), “international-quality picture” (clinluo), “rich-layered [background picture]” (hooraychining), etc. The renowned American filmmaker Quentin Tarantino praised it in 2020, saying, “A cinematic masterpiece of this calibre has never been attempted, though I could not imagine it ever being pulled off better” (IMDb, 2020).

Though audiences marvelled at the animation, as the above comments reveal, the English-dubbed DVD version contains no subtitles, unlike other language versions. There are five versions of the film, dubbed in Chinese Mandarin, Chinese Cantonese, Chinese Uygur, English and Japanese, demonstrating a solid sociocultural demand from audiences with different linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Such a variety of versions exemplifies the complexity and intertextuality in different dubbed and subtitled dialogues. For the Mandarin-dubbed version released in China, bilingual subtitles were often provided. Therefore, it is imperative to understand the context for the combined use of dubbing and subtitling and how it may impact film translation strategies. Comparing dubbing and subtitling strategies can provide new insights into how film translation strategies maximise and optimise the viewing experience. The main focus of this study is on dubbing practice. Only the English-and-Chinese-dubbed versions will be compared in this study. This is because the subtitles of the English-dubbed version cannot be traced, and relatively less academic attention is given to dubbing practices for Monkey King (as the literature below suggests).

Reviewing the Dubbed Monkey King: Hero is Back

While receiving broader attention from public audiences, Monkey King also attracted increasing academic attention. A search in the China Knowledge Resource Integrated Database (CNKI), the most extensive and authoritative academic database in China, with “西游记之大圣归来” (Monkey King: Hero is Back) and its relevant keywords revealed 542 research papers on the film published as of 19 August 2022. The number of publications is more than triple that of 2020 (174 research papers published as of 27 June 2020), proving it to be an active, hotly debated topic. Nevertheless, very few of these papers focused on comparing its different dubbed versions. It is noteworthy that one paper explicitly targets the translatability of the Uygur-dubbed version of the film from the perspective of functional equivalence (Zhi, 2019). Apart from that one study, only five papers directly look at the subtitling practice of Monkey King, with one article having a particular reference to the use of culturally loaded words (Han, 2020), and the rest mainly on the analysis of box-office success (Chen, 2015), marketing strategies (Zhang, 2015), production (Tian, 2015), film aesthetics (Li, 2015), and possible influences on the Chinese animation industry (Wang et al., 2015).

More recent publications from the West are on how this film reshapes the heroic image of the monkey king with a multimodal approach, using Praat software from the field of phonetics to capture voice quality. The monkey king is projected as “sympathetic, responsible, yet frustrated in the Chinese movie” while the humanised monkey is reprojected “as frustrated, cold and firm so as to suit the taste of the American film viewer” (Wang and Li, 2020, p. 122). To ensure a good reception, a crowdfunding campaign was launched to finance the film’s production and promote it on social networks among viewers at home and abroad (Villén et al., 2020).

This paper specifically explores how to better satisfy Western target audiences by comparing the Mandarin-dubbed and English-dubbed versions of Monkey King and their trailers and investigating the effectiveness of their translation strategies for appellations and idiosyncratic language. It is hoped that the comparison of different dubbed dialogues and its implications for the effectiveness of dubbing practices can fill the gap in discussion with a focus on the reception and promotion of these two different versions.

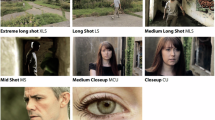

Towards a macro and micro conceptual framework

This section builds a theoretical model by adopting macro theories and micro concepts for the case analysis. On a macro level, the dubbing strategies used in this case-study are analysed with two translation theories and three translation models: Even-Zohar’s (1979) “polysystem theory”, Ernst-August Gutt’s (1991, p. 27) “relevance theory”, Chesterman’s (2000) “causal models”, and Pérez-González’s (2015) “psycholinguistic models” and “neurolinguistic models” that were developed from Chesterman’s (2000) “process models”Footnote 1 of audio-visual translation. On a micro level, source text-oriented and target text-oriented film translation strategies will be assessed for linguistic and cultural transfer in this case-study. These theories are selected to frame the dubbing work in terms of the theoretical macro base and the micro translation method because these theories identify the external and internal factors determining the strategies used in Monkey King, as Fig. 1 demonstrates.

When applying this conceptual framework to the dubbing of Monkey King, we divide them into external and internal factors determining the translation theories, models and methods. Polysystem theory, neurolinguistic model and source text-oriented film translation play a fundamental role in affecting the external factors. They both consider the exotic determinants rooted in the original film, such as the visibility and idiosyncrasy of the source culture. In contrast, relevance theory, causal models, psycholinguistic models and microlevel target text-oriented film translation are closely related to the internally accessible assumptions. They unveil how different “levels of causation” interact to improve audience experience and creatively reshape linguistic information that reflects target audiences’ pre-packaged knowledge and beliefs.

On a macro level, driven by external factors such as “institutionalised genres, non-canonised forms of expression and … translated films” (Pérez-González, 2015, p. 121), Even-Zohar’s (1979) polysystem theory, the neurolinguistic model and source text-oriented film translation are of great relevance. They consider the outer filmic system, which can account for the interplay between the source culture and the superhero film genre that facilitates the interaction of different subsystems. They include various interconnected and externally decisive subsystems (language, economy, politics or ideology, etc.) to interpret the holistic meaning (Pérez-González, 2015, pp. 121–126). Source text-oriented film translation is also adopted to replicate the originality and idiosyncrasy of the source culture and film.

Additionally, background music and visual images are another important external factor affecting the dubbing strategies involved in the case-study. The “neurolinguistic model” is a submodel (Pérez-González, 2015) of Chesterman’s (2000) process models that facilitates the understanding and interaction of different audio and visual tracks that is most suitable for the two dubbed versions of this case-study. The term “models” is often understood as being “intermediate constructions, between theory and data and used to illustrate a theory, or part of a theory” (Chesterman, 2000, p. 15). Vilaró et al. (2012) argue the following:

The perception of a given visual clip can vary if it is viewed in combination with different audio tracks. Changes in acoustic stimuli would appear to influence the gaze trajectories and the foci of the viewing experience. The insight that sound proves to be as important as images in shaping viewers’ perception and comprehension of audio-visual content has important implications for studying audio description (Pérez-González, 2015, p. 105).

In contrast, internally focused relevance theory and two translation models will be used to analyse how the dubbing process maximises the appeal to the target audience. Through this prism, relevance theory serves as an appropriate departure point where viewers use their background knowledge to interpret cinematic signifiers (Pérez-González, 2015, p. 108; Desilla, 2009). In other words, target audiences interpret the contextual meaning in the film based on their readily accessible assumptions, looking for rhetorical preferences to be satisfied (Pérez-González, 2015, p. 120).

In addition, two translation models further structure the case analysis in reconfiguring a Chinese legend for the West through the dubbing process: the causal model and the psycholinguistic model.

As Chesterman (2000, p. 19) argues, causal models justify the potential effects of the translation in terms of the following references:

Representations of translation [aim] (i) to unveil how different “levels of causation”—including cognitive, situational and sociocultural issues—influence the production of the target text; and (ii) to identify the effect that the target text has on its readership (Pérez-González, 2015, p. 98).

Causal models explain how translation is shaped in different contexts through the interaction of power, prestige and other market factors (Pérez-González, 2015, p. 92). In the case-study, to cater to Western audiences when consuming a Chinese legend, target audience-oriented dubbing strategies have been adopted, taking the Western market into account.

“Psycholinguistic models”, as one of the submodels of Chesterman’s (2000) process models put forward by Pérez-González (2015), will also be considered. This is because the psycholinguistics nature of this model fits well with audience participation in processing the dubbed conversation (Pérez-González, 2015, p. 124). Viewers processing audio-visual materials start from the form of words and then map meaning onto them (Pérez-González, 2015, p. 99). This process echoes relevance theory, whose central idea is linking some “previously held assumptions” with the new communicated information in the translated film (Liang, 2020, p. 4).

On a micro level, translations are shaped by the interaction between different filmic subsystems to cluster around two poles—source text-oriented and target text-oriented translations. The former involves a relatively straightforward linguistic replication into the target language; source text-oriented film translations are widely held to foster formal and conceptual representations in the receiving culture, with minimal adaptations of culture-specific meaning. In contrast, target text-oriented film translations serve the target audience through cultural realignment and adaptation by pandering with the conventions that prevail in the receiving context. Perego (2004, p. 161) explicitly explains the role of target text-orientation as follows:

The unobtrusive manipulation and use of target culture frames … to orient viewers and provide them with an effective cognitive framework that enables them to interpret new realities consciously and process them quickly and efficiently despite their foreignness.

This study hypothesises that the English-dubbed version tends to adopt target text-oriented film translation, prioritising the smoothness of the filmic dialogue regardless of the idiosyncratic language about Chinese culture. These distinctive dialogues are deeply rooted in Chinese culture and heritage, based on the time-honoured story Journey to the West.

Case analysis

In this case-study, the English- and Mandarin (Simplified Chinese)-dubbed versions were extracted from the official DVDs for textual analysis, with the Chinese-dubbed film as the source text. English back translation will also be provided for Mandarin dubs, while the English-dubbed version is the main focus of our study, examining how the legendary Chinese story travels to the West through dubbing.

It will be seen that dynamic adaptive dubbing is adopted in the source text, the Mandarin-dubbed versions. Adaptive dubbing refers to “an extreme form of domestication involving a significant departure from the source text and, in some cases, the reconfiguration of nonverbal components of the audio-visual texts” (Pérez-González, 2015, p. 124). As a result, new narratives and the deployment of new visual transitions will be given to characters that initially inhabited other fictions and dramatic spaces when using adaptive dubbing (Pérez-González, 2015, p. 125). Unlike Mandarin-dubbed dialogues, the English dialogue, Remael (2003) argues, as the English-dubbed versions will show, tends to “reinforce established conventions, uphold traditional power relations and minimise the contribution of dissenting voices”.

Dubbing the film trailers

Pérez-González (2015, p. 123) argues that trailers ultimately dropped dialogue to ensure that subtitled or dubbed dialogues do not deter American viewers from going to cinemas because of a dislike for either reading subtitles or hearing Americanised language. Although the dubbed dialogues are used throughout the official Chinese MandarinFootnote 2 and English trailersFootnote 3 of Monkey King, no subtitles are shown in the English trailer, while the Mandarin one offers simplified Chinese subtitles. The English official trailer intends to add background knowledge to inform foreign audiences of the contextual details of the plot development of this Chinese heroic story. The added information descriptively includes the time of the story “500 years later” (when Sun Wukong (the monkey king) was punished by being trapped under a mountain), and a summary of the main plot as “a lost boy…will free him (Sun Wukong) forever…and start a friendship…to save the world from evil”. Furthermore, the advertisement for the main dubber, “Jackie Chan is Monkey King,” reminds foreign audiences of how the legendary Chinese story proceeds with the familiar, anticipating well-known Chinese actor Jackie Chan. This is a good case where relevance theory is applied to the English-dubbing practice since the famous Chinese actor is already favourably received in the West. The connection may be established with the potential to link the success of Jackie Chan’s acting career with the Western audience’s expectations of Chan, as relevance theory defines that “previously held assumptions” are appropriated in the translated texts (Pérez-González, 2015, p. 99). Apart from relevance theory, the “neurolinguistic models” also play a decisive role in constructing acoustic and visual elements (Vilaró et al., 2012) in the official English-dubbed trailer of Monkey King. More action scenes can be found in the English trailer than in the Chinese trailer, which maximises the appeal to Western audiences with plot information to smooth the experience. The authorised English versions can be found on IMDb and Rotten Tomatoes, the two most widely accepted film ratings and reviewing platforms in Anglophone countries.

Unlike the English trailer, the Mandarin Chinese trailer adds summative information to reiterate the call for a hero in modern times with Mandarin Chinese subtitles repeating the spoken text. The additionsFootnote 4 include “不能放弃的自由” (indispensible freedom), “不被压印的梦想” (unrepressed dreams), “为信与爱而战” (fighting for faith and love) and “这是一个需要英雄的时代” (this is a time that needs a hero). None of the above information reflects the plot development. Instead, it relates directly to the story’s theme. In duration, the English-dubbed version, lasting for 1 min and 56 s, is comparably longer (30 s) than the Chinese version. This is probably because more background information is needed to facilitate understanding for international audiences in the English-dubbed version. In contrast, the domestic Chinese version is more likely to be politically driven, promoting a sense of pride in its cultural heritage (Liang, 2022).

What both trailers reveal confirms the above hypothesis that the Chinese-dubbed trailer is source culture-oriented, intensifying its domestic agenda thanks to the added summative information. However, the English-dubbed version is target culture-oriented in that prior knowledge is needed for Western viewers to ensure smooth reading when encountering otherness embedded in ancient Chinese culture.

Dubbing norms

Toury (1995, p. 55) defines norms as “the translation of general values or ideas shared by a community—as to what is right or wrong, adequate or inadequate—into performance instructions appropriate for and applicable to particular situations”. Temporal, geographical and cultural constraints thus bind normative principles governing what is regarded as an adequate translation. The relevance of translating norms to polysystem theory is target text-oriented film translation because:

Translations are considered to be facts of the target culture, their characteristics being conditioned by target culture forces. By familiarising themselves with the constraints operating in a given historical target context, scholars stand a better chance of successfully formalising the different norms that lie behind translators’ choices (Pérez-González, 2015, p. 125).

Dubbing norms challenge dubbers in Monkey King because the ancient Chinese culture includes many variants of appellations for the leading character Sun Wukong and its idiosyncratic language distinguishes the dubbing practice. The case analysis will therefore investigate these two features in the film.

Dubbing the appellations of Sun Wukong

Sun Wukong is one of the key disciples of the priest Sanzang, hero of the Chinese masterpiece Journey to the West. In this Hollywood-style animation, Monkey King replaces the traditional four leading characters, i.e., Sanzang (Tripitaka), Sun Wukong (the monkey king), Zhu Bajie (Pigsy) and Sha Wujing (Friar Sandy), with three postmodernised leading characters, Sun Wukong (the Monkey), Zhu Bajie (the Pig) and Jiang Liu’er (the Little Monk). By doing so, a new interpretation of theWesternised Chinese heroic legend has been instilled in the film (Feng and Fan, 2016, p. 114). A close look at Sun’s appearance indicates that this adaptation first presents him as a long-faced, dishevelled and slovenly dressed ruthless monkey, concluded by heroic imagery at the end when he saves others from danger. Such an appearance is more likely to cater to Western audiences, as Sun’s image is associated with the tall and slender figure of Western men, compared to the traditional, short, bulging-mouth Sun Wukong image that Chinese audiences have long held (Liu and Yu, 2012, p. 91). The causal and psycholinguistic models are applied to Monkey King’s projection in this particular scene to better suit Western audiences’ visual and mental expectations and preferences for heroic images.

Example 1 The Wild Monkey

Mandarin Dub 00:19:05 → 00:19:06 | 哪里来的野猴子 [Where does the wild Monkey come from?] |

English Dub 00:19:19 → 00:19:20 | (Mountain trolls chattering) |

In Example 1, mountain trolls chase the child monk Jiang Liu’er and the Little Girl. Sun Wukong appears to suddenly stop the trolls. They therefore complain. “野” (wild) in “野猴子” (wild monkey) in the Mandarin dub is used in contrast to “polite” and “civilised”, indicating the negative attitude of the speaker.Footnote 5 However, the English-dub chooses not to dub any such negativity, only appending to the description of the screen: mountain trolls chattering. The English dubs, in this instance, best illustrate the zero-translation strategy that may benefit from multimodal elements (Pérez-González, 2015, p. 108), such as mountain trolls’ angry facial expressions and high-pitched yelling, as clearly shown in the scene. The causal model can be argued to be the source of the intended effect of zero-translation upon the recipients, as they are able to understand contempt and dissatisfaction through the visuals and background sound instead of the English dubs. In light of this, “the least expenditure of the hearer’s effort” is spent relying only on the contextual effect of the scene (Chesterman, 2002, p. 157), which is optimally relevant to audiences when the discontent is expressed visually in the English-dubbed version. In the next instance, more idiomatic expressions and dynamic strategies are adopted throughout these two different versions.

Example 2 My Little Brain

Mandarin Dub 00:24:31 → 00:24:32 | 俺老孙脑仁儿都被你吵炸了 [Your yelling makes me and my little brain blow away.] |

English Dub 00:24:45 → 00:24:46 | I can’t think, my head’s gonna explode. |

What Example 2 reveals is that Sun Wukong is fed up with Jiang Liu’er’s endless questions stemming from his worship of the Great Sage Monkey King. The Mandarin dialogue vividly suggests Sun’s humorous characteristics by using the dialectal form of “me” “俺” (dialect: me) and the metaphorical term “脑仁儿” (little brain) to deliver his humorous, self-deprecating complaint and impatience. Compared to the Mandarin dubs, the English dialogue is more straightforward when conveying such unpleasantness: “I can’t think, my head’s gonna explode” does not include dialectal features with their humorous undertones of self-character analysis (“俺”/myself). According to Toury’s (1995) approach to translating norms, target orientation is employed under the guidance of polysystem theory when translation reflects target culture forces. In this case, it relates to linguistic forces, the Chinese dialect. The Mandarin dubs humorously transfer the dialectal and arrogant characteristics so that Chinese viewers can be easily entertained. Unlike the Mandarin-dub choice, the English-dub options seem more neutral, avoiding the nuances of cultural connotations embedded in the source text to smooth the target audiences’ viewing experience. Similarly, the following example shows a similar instance of Chinese dubs intensifying the humour of the monkey’s character while losing such personality in the English dubs.

Example 3 Your Great Sage Sun

Mandarin Dub 00:25:46 → 00:25:47 | 既然知道你孙大圣在此 [Now you know your Great Sage Sun [surname] is here.] |

English Dub 00:26:00 → 00:26:03 | I’m no ordinary monkey, this doesn’t have to get ugly. |

In this instance, the Mountain Lord is warning Sun Wukong to behave well while Sun arrogantly and dismissively responds to his threat “既然知道你孙大圣在此” (Now you know your Great Sage Sun is here). The “causal model” can best illustrate the Mandarin-dub choice when Sun uses the rhetorical device “Great Sage” to link himself in an imaginary familial relationship (Great Sage Sun) to the mountain troll. It strengthens his confidence in defeating the troll. The humorous effect occurs mainly when juxtaposing Sun’s arrogance and pride with the mountain troll’s irritation and speechlessness. The English-dubbed dialogues employ explication to convey linguistic information with minimal necessary adaptations (Pérez-González, 2015, p. 121). Target reader-oriented translation strategy is employed through explication in the English dubs because the target readers spend the least effort understanding the exotic appellation of “Great Sage Sun” when it is replaced by the clear statement “I’m no ordinary monkey”. This exchange leads to the transition to the forthcoming violent scene where the monkey and the troll are about to fight (implied by “this doesn’t have to get ugly”). If the familial relationship between Sun and his opponent is metaphorical and ironic in this example, Example 4 articulates such a relationship more directly.

Example 4 Your Grandpa Sun

Mandarin Dub 00:52:23 → 00:52:24 | 小小伎俩还想骗你孙爷爷 How dare you fool your Grandpa Sun with this little trick?] |

English Dub 00:52:18 → 00:52:20 | Wow, I had a feeling the service here would be terrible. |

Thanks to the rhetorical preference in the Mandarin sub, the appellation of Sun Wukong in Example 4 proves to be hilarious and humorous as Sun arrogantly names himself “你孙爷爷” (your Grandpa Sun). In this case, when mountain troll-transformed Skeleton Demon beats Zhu Bajie (Pigsy), Sun comes in and saves him. Sun tries to build a familial relationship humorously and sarcastically with the Skeleton Demon (she) by addressing himself as her relative (Grandpa). Meanwhile, he is beating her. The Mandarin dubs convey the rhetoric and humour of the monkey’s bluster by identifying himself to his enemy as “your grandpa Sun”.

In contrast, the English-dub adheres to “psycholinguistic models” to connect the viewers’ previously established contextual information implied in the filmic plot development, adding no explanations to the Chinese source text’s humorous and sarcastic appellation. Through the comprehensive psycholinguistic model, the target text-oriented film translation produces linguistic representations analogous to the source language (Shreve and Isabel, 2017, p. 134). Even though the literal meanings have been well maintained and explained to the audience, the mental representation of Sun Wukong has unfortunately been lost.

In summary, English dubs tend to use standardised language in a straightforward and neutralised way at the cost of relaying contextually amusing information. A dynamic translation strategy was adopted in this film, including examples of strategies such as zero-translation (Example 1), neutralisation (Example 2) and explication (Examples 3 and 4). Chesterman’s (2000) causal models may explain this dynamism because neutralised and everyday approachable language could be understood as a deliberate, target audience-driven attempt to intertextually connect the speech style and linguistic effects featured in this action-loaded animation genre. Such deliberation centres on the target audience style characterised by “vernacular heightened and burnished to the level of streetwise poetry” (Fabbretti, 2022, p. 73; Porter, 2003, p. 105).

Dubbing idiosyncratic language

This section explores the film translation of idiosyncratic language drawn from Monkey King. According to Romero-Fresco (2006), the translator uses intensifiers and discourse markers even when these are not present in the source text. This tendency adheres to the idiosyncratic conventions of dubbed language to convey orality (Pérez-González, 2015, pp. 119–120). Pavesi (2009: p. 209) also advocates for the use of such an indication:

… such distinctive traits cannot all be accounted for as shifts in level or formality or moves towards the written form of the target language. Rather, these features may have to do with different factors such as film discourse structure and norms emerging both in stimulated spoken [language] and film translation.

Example 5 Nursery Rhyme

Mandarin Dub | 点点羊羊 点到谁来当肥羊 |

01:04:35 → 01:04:38 | [Count the sheep. I’ll choose whichever is pointed at by the fat sheep.] |

English Dub 01:04:31 → 01:04:34 | (mumbling) |

Example 5 is an illustration of orality embedded in idiosyncratic language. The little monk invades the mountain troll’s caves trying to save the little girl. One mountain troll is hunting Jiang Liu’er while he successfully hides. In this scene, the troll is confused by Jiang’s disappearance, struggling to differentiate Jiang’s guise as a troll from his actual fellow trolls. The troll that is chasing Jiang is now counting the number of all the trolls in order to identify him among his companions, mumbling “点点羊羊 点到谁来当肥羊” (Count the sheep. I’ll choose whichever is pointed at by the fat sheep). These lines originate from a nursery rhyme uttered by children playing games to decide randomly who should be picked.

Although polysystem theory argues that the target text-orientation method can enable viewers to have a creative and compelling viewing experience to process information (Perego, 2004, p. 161), the English dubs, in this case, adopt zero-translation. It again proves that the viewers resort to both image and sound to verify contextual meaning, as they do in Example 1. Even though immediate equivalences can be found in English, “Eeeny, meeny, miney, mo. Put the baby on the po”, the English-dub entirely omits such equivalent expressions and does not synchronise them with the original dialogue. Multimodality (Baldry and Thibault, 2006, p. 49) can again explain such an omission when the mountain troll is reaching out his hands and counting. Considering this, audiences who are watching the English version can anticipate the counting action, although the audio track fails to inform viewers of the actual information. Likewise, relevance theory also indicates that the contextual information will be accessible via the film’s image and sound (Desilla, 2009) because viewers are able to expect a search when they watch the clumsy troll looking confused and worried. Multimodality also applies to the following example by linking viewers’ pre-existing imagery of what Pigsy looks like with the upcoming fantastic scene.

Example 6 Humorous Effect

Mandarin Dub 00:35:18 → 00:35:20 | 你看我都瘦成什么样了 [You take a look at how skinny I am.] |

English Dub 00:35:34 → 00:35:35 | 500 years with this pig snout on my face. |

The last example directly refers to dubbing humour in a situation where Pigsy ironically introduces his body figure. The introduction relates to the punishment Pigsy received after he angered Sun Wukong. Humour comes in because how Pigsy depicts himself completely contradicts what audiences see on the screen. The dialogues in MandarinFootnote 6 and English use explication, although the image of explication differs.

The Mandarin dub “你看我都瘦成什么样了” (you take a look at how skinny I am) is different from what we see on the screen, an obese pig with a big belly. If the Chinese dubs use irony and sarcasm in Pigsy’s punishment, the English dubs opt for exaggeration and self-contempt, “500 years with this pig snout on my face”. Causal models can justify the rationale for the translators’ choice when audiences consume the filmic content. Audiences can process the information based on their relevant knowledge and experience that are readily associated with the image and sound, as shown on the screen (Pérez-González, 2015, p. 98). In this case, the audiences easily link the image of Pigsy’s ugly drooling to disgust.

In sum, the idiosyncratic language of the Mandarin dubs in regard to the nursery rhyme goes untranslated in the English dubs. The English-dubbed dialogues frequently resort to the visual and acoustic effects of the film, often leaving the dialogues untranslated or generalised. However, the humorous effect in Example 6 is well maintained in the English dubs but with contrasting imagery compared with the source text.

Conclusion

This study examines how dubbing is done in the case-study film Monkey King: Hero is Back (2015) through the lens of two dubbed versions. Mandarin Chinese is the source text, while the English counterpart is the target text. When dubbing the officially sanctioned Mandarin and English trailers, the adopted dubbed strategies do not seem to comply with Rich’s (2004, p. 156) argument that “no foreign-tongue trailers” have been shown since the 1980s. This inconsistency could result from increasing resistance in the U.S. against monolingualism and the advancement of multilingualism. In this case, multilingualism encompasses Mandarin Chinese and English trailers based on the same film in diverse foreign languages. Necessary dubs and additional background and contextual information are inserted to better cater to the needs of viewers with different cultural backgrounds (Newmark, 1988). The English dubs and additional messages are informative, while the Chinese tend to be more summative.

The findings verify the hypotheses set at the beginning that the Mandarin-dubbed version intends to use source text-oriented translation to diversify the idiosyncratic language in Chinese culture. At the same time, the English counterpart tends to adopt target text-oriented film translation, adding background information to facilitate a thorough understanding of a film rooted in a foreign culture. The findings suggest that target culture-oriented translation has been dominantly adopted in the English-dubbed version. Five examined instances out of six confirmed this assumption, except for one using shifting imagery to transfer humour (Example 6). Chinese dubbing strategies are much freer in recreating the original orality with updated norms and idiosyncratic language—the dubbers’ sensitivity to the nuances of language and its creativity matters (Pavesi, 2009: p. 209). However, the English-dubs supplement the hypotheses because the more frequently used strategies, including explication, zero-translation and neutralisation, are adopted to enhance the acceptability and fluency of the target viewers’ experience, as the intricate ancient Chinese heritage and creative wordplay impede Western audience understanding.

What follows are the responses to two research questions. The answer to research question (1), “What changes are made to reconfigure a Chinese superhero through the English-dubbed version of Monkey King compared to the Chinese-dubbed version?”, is inspired by Remael’s (2003) argument that subtitled dialogues tend to neutralise foreign roots and their diversities. The frequent use of standard language also applies to the English-dubs reshaping a Chinese superhero in the Western landscape using zero-translation, neutralisation and explication.

Regarding research question (2), “What are the study’s practical and theoretical contributions to Audio-visual Translation Studies (AVT)?”, this study provided an analysis of English-dubbing practice on a genre-specific film Monkey King: Hero is Back (2015) featuring Western superhero archetypes and Chinese archaism. This study attempts to fill in the underresearched topic of comparisons of different dubbed versions to examine how the Monkey King’s image is reshaped in the Western cultural market. Theoretically, this study provided a framework with macro theories and models and micro translation strategies that are strategically useful for future research of this kind. On the macro level, two translation theories, polysystem theory and relevance theory, and three translation models, the causal model, the psycholinguistic model and the neurolinguistic model, are used simultaneously to seek contextual appropriateness. These theories are based on external factors and internal elements that affect the interpretation of cultural norms and idiosyncratic language. On the micro level, two translation strategies, source text-oriented and target text-oriented strategies, are utilised to read two dubs of this animation. The case analysis suggests that these two strategies are not binary. Instead, more concomitant strategies can be found, such as zero-translation, explication and neutralisation, positioned by the linguistic and cultural disparities between China and the West. This is because translation is at the service of commercial demand to adapt the Chinese superhero to the Western market, taking into account the acceptance and preference of target viewers, as Chesterman (2007, p. 175) argues:

In terms of a simple causal chain, for instance, we could say: this translation is like this, it contains these particular features, because of the decisions that this translator took … the norms governing translation work of this kind in this society at this time, which are themselves determined, e.g., by commercial values.

However, the scope of this study is inevitably limited. More representative examples should be considered. It would be worthwhile to compare more language pairs by the effectiveness of dubbing and subtitling practice in future research. Since flexible and dynamic translation strategies have been used when dubbing a Chinese heroic legend to the West, further investigation can examine how target audience expectations affect translation strategies. Translators appear to expect Western target viewers to prioritise fantastic action scenes rather than the witty wordplay and time-honoured cultural heritage in the Chinese source text.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Change history

25 October 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01419-7

Notes

Chesterman (2000, p. 98) proposes three model types that underpin audio-visual translation. They are process models, comparative models and causal models. A process model signifies different “phases of the translation process”. Comparative models seek “similarity between source and target texts”. Causal models explore how different “levels of causation” interact and impact the “target text on its readership”, and are relevant to this study.

The Chinese official film trailer of Monkey King can be found on the video platform Youku https://v-wb.youku.com/v_show/id_XMTcxNDgxNjk4MA=.html.

The English official film trailer of Monkey King: Hero Is Back (2015) are available on IMdB https://www.imdb.com/video/vi4126062105?playlistId=tt4644382&ref_=tt_ov_vi and Rotten Tomatoes https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/monkey_king_hero_is_back/trailers/11291731.

The authors of this paper provide all the English translations of the Chinese trailers’ additional information.

It is interesting to note that in the Cantonese dubbed version, this line has been rendered as “无端端嚟只死马骝” [Where on earth comes this bloody baboon?]. “死” (bloody) in “死马骝” (bloody baboon) clearly shows the stronger anger and frustration in the curse put on Sun Wukong by the trolls than the corresponding translation in the Mandarin version.

It is intriguing to note that the Cantonese dub is most humorous as it uses a metaphor to compare the stable obese version of Pigsy to the tiny grasshopper.

References

Baldry A, Thibault PJ (2006) Multimodal transcription and text analysis: a multimedia toolkit and coursebook. Equinox, London

Chen C (2015) On essential factors to the success of Monkey King: hero is back. J News Res 16:202–203

Chesterman A (2000) A causal model for translation studies. In: Olohan Maeve (ed.) Intercultural faultlines. Research models in translation studies I: textual and cognitive aspects. St Jerome, Manchester, pp. 15–28

Chesterman A (2007) Bridge concepts in translation sociology. In: Fukari A, Wolf M (eds.) Constructing a sociology of translation. John Benjamins Publishing, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, pp. 171–186

Chesterman A (2002) Semiotic modalities in translation causality. Across Lang Cult 3(2):145–158. https://doi.org/10.1556/Acr.3.2002.2.1

Desilla L (2009) Towards a methodology for the study of implicatures in sub titled films: multimodal construal and reception of pragmatic meaning across cultures. Unpublished Ph.D Thesis. University of Manchester

DW.com (2015) Sieren’s China: ‘Monkey King’ is a domestic success. https://www.dw.com/en/sierens-china-monkey-king-is-a-domestic-success/a-18617116. Accessed 28 Jun 2020

Even-Zohar I (1979) Polysystem theory. Poet Today 1(1–2):287–310. https://doi.org/10.2307/1772051

Fabbretti M (2022) Japanese video games in English translation: a study of contemporary subtitling practice. Translat Matter 4(1):66–85. https://ojs.letras.up.pt/index.php/tm/article/view/10785

Fang WT, Hsu M-L, Lin P-H, Lin R (2019) The new approach of Chinese animation: exploring the developing strategies of Monkey King—Hero Is Back. International Conference on Human-computer Interaction. Springer, Cham, pp. 144–155

Feng T, Fan K-K (2016) A brief analysis of Chinese and western cultural differences in animated films. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Advanced Materials for Science and Engineering IEEE-ICAMSE 2016—Meen, Prior & Lam (eds), pp. 113–115

Fresco P (2009) Naturalness in the Spanish dubbing language: A case of not-so-close Friends. Meta: journal destraducteurs/Meta: Translators’ J 54(1):49–72

Gutt E-A (1991) Translation and relevance: cognition and context. Basil Blackwell, Oxford, Cambridge, MA

Han J (2020) The subtitling of cultural-loaded words in Monkey King: hero is back from Skopos Theory Perspective. Overseas Engl 5:116–117

IMDb (2015) Monkey King: Hero is Back (2015) User reviews. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt4644382/reviews?ref_=tt_urv. Accessed 1 Feb 2022

IMDb (2020) Review of Xi You Ji Zhi Da Sheng Gui Lai: Best Movie of 2015 (Snubbed at the Oscars). https://www.imdb.com/review/rw5998270/. Accessed 16 Aug 2022

Jiang F, Huang, K (2017) Hero is Back—The Rising of Chinese Audiences: the demonstration of SHI in popularising a Chinese animation. Glob Media and China 2(2):122–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059436417730893

Ku C (2015) “Monkey King: Hero is Back” Left the Cinema: reaching 956 Million Yuan Box Office after its 62 Day’s China Cinema Release (电影《西游记之大圣归来》下线 上映62天票房达9.56亿). DianYingJie.Com. 10 September, 2015. https://www.dianyingjie.com/2015/0910/6133.shtml. Accessed 5 Feb 2022

Li, Li (2015) Hero is back: Tang Monk becomes a Boy Monk Wukong is Great Uncle (《大圣归来》唐僧变熊孩子 悟空是酷大叔).” 6 July, 2015. http://ent.sina.com.cn/m/c/2015-07-06/doc-ifxesftz6779484.shtml. Accessed 31 Jan 2022

Liang L (2022) Subtitling english-language films for a Chinese audience: cross-linguistic and cross-cultural transfer. Sun-Yat Sen University Press, Guangzhou

Liang L (2020) Subtitling Bridget Jones’s Diary (2001) in a Chinese Context: the transfer of sexuality and femininity in a Chick Flick. Int J Comp Lit Translat Stud 8(4):1–13. http://www.journals.aiac.org.au/index.php/IJCLTS/article/view/6699/4646

Liu J, Yu S (2012) The development of Sun Wu Kong’s image in Chinese Animation (中国影视动画中孙悟空造型的演变). Film Art 6:90–96. https://kns-cnki-net-443.webvpn.sysu.edu.cn/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFD2012&filename=DYYS201206019&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=PP90Nl7g5Bqi24Sn6-x-bYxTVP25H9qlpC0HSOJWo_dD231TkQ7X_0pWD_2KGc2Q

Newmark P (1988) A textbook of translation (Vol. 66). Prentice Hall, New York

Pavesi M (2009) Dubbing English into Italian: A Closer Look at the Translation of Spoken Language. In: Cintas JD (ed.) New trends in audiovisual translation. Multilingual matters, Bristol, pp. 197–209

Perego E (2004) Subtitling culture by means of explicitation. In: Sidiripoulou M, Papaconstantinou A (eds) Choice and difference in translation. University of Athens, Athens, pp. 145–168

Pérez-González L (2015) Audiovisual translation theories, methods and issues. Routledge, New York

Porter D (2003) The private eye. In: Priestman Martin (ed.) The Cambridge companion to crime fiction. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 95–113

Remael A (2003) Mainstream narrative film dialogue and subtitling: a case study of Mike Leigh’s ‘Secrets and Lies’ (1996). Translator 9(2):225–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2003.10799155

Rich BR (2004) To read or not to read: subtitles, trailers, and monolingualism. In: Egoyan A, Balfour I (eds) Subtitles. On the foreigness of film. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA and London, pp. 153–169

Romero-Fresco P (2006) The Spanish Dubbese: a case of (Un)idiomatic friends. JoSTrans 6:134–52. https://jostrans.org/issue06/art_romero_fresco.pdf Accessed 24 Jun 2020

Shreve GM, Isabel L (2017) Aspects of a cognitive model of translation. In: Shreve GM, Lacruz I, Schwieter JW, Ferreira A (eds) The handbook of translation and cognition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, Hoboken and New York, pp. 127–143

Tian X (2015) Monkey King: a journey to the west. J Contemp Cinema 7:100

Toury G (1995) Description translation studies and beyond. John Benjamins, Amsterdam and Philadelphia

Vilaró A, Duchowski AT, Orero P, Grindinger T, Tetreault S, di Giovanni E (2012) How sound is the pear tree story? Testing the effect of varying audio stimuli on visual attention distribution. Perspect Stud Translatol 20(1):55–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2011.632682

Villén H, Sergio J, Ruiz-del-Olmo FJ (2020) Crowdfunding as a catalyst for contemporary Chinese animation. Animation 15(2):130–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746847720933792

Wang Hui, Li X (2020) Reshaping the Heroic Image of Monkey King via multimodality. In: Zhang Meifang, Feng D (ed.) Multimodal approaches to Chinese-english translation and interpreting. Routledge, Abingdon, Oxon; New York, pp. 91–123

Wu C, Jenner WJF (2003) Journey to the West (Chinese Classics, Classic Novel in 4 Volumes). Foreign Languages Press, Beijing

Wu C (1592) 西游记 [Journey to the West]. Shi De Tang Press, Shanghai

Zhang Y (2015) Behind the scenes of the counter-attack of Monkey King: hero is back in marketing. Bus Manag Rev 8:29–31. (In Chinese)

Zhi X (2019) “‘功能对等’理论下汉维影视翻译研究——以《西游记大圣归来》维译版为例”(Research on Chinese and Uygher Film translation under the concept of “Functional Equivalence”). Xinjiang Normal University. Master Thesis

Acknowledgements

The author discloses receipt of the following financial support for the research. This research was supported by the project funded by the Center for Translation Studies from Guangdong University of Foreign Studies (grant number CTS202109) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Sun Yat-Sen University (grant number 22qntd5301). The author’s deepest gratitude goes to Professor Hui Wang for her precious feedback on the initial project and helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study involves no human participation.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by the author.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, L. Reconfiguring a Chinese superhero through the dubbed versions of Monkey King: Hero is Back (2015). Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9, 369 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01385-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01385-0