Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to identify and evaluate the key challenges to project procurement in public-sector agricultural development projects in Bangladesh. Being exploratory in nature, the study applied the modified Delphi method, the best worst method (BWM), and the interpretive structural modelling (ISM) approach sequentially for the investigation. Ten key procurement challenges were identified and validated through the use of a literature review and two rounds of modified Delphi with the input of 15 experts in the field. Then the BWM was applied to assess the responses of eight industry experts to estimate the relative importance of the challenges. After that, a second panel of ten experts was interviewed using ISM to look at the contextual relationships between the challenges. This led to a four-layer interpretive structural model and MICMAC (cross-impact matrix multiplication applied to classification) analysis of the challenges. Among the 10 key challenges, ‘lack of competent procurement staff’ is found to be the most significant challenge; whereas, based on the inter-relationships among the challenges, ‘political influence’ is identified as the most influential challenge. As a result, it is recommended that relevant professionals and policymakers address these challenges in terms of their relevance, relative dependencies, and influences in a holistic manner. This study addresses a knowledge gap by offering a thorough investigation of the challenges associated with public-sector agricultural project procurement in a developing country’s context. This makes it useful for professionals in the field, academics, policymakers, and future researchers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Procurement challenges in public-sector development projects in developing countries are unique because these projects frequently face a variety of idiosyncratic risks. The procurement is determined by the project scope, project plan, and project procurement plan. Like other forms of public procurement, it adheres to government rules and guidelines in order to source goods, services, and work while ensuring value for money (Ahsan and Paul, 2018; Khan et al., 2022; Project Management Institute (PMI), 2017). The projects are highly complex due to difficulties relating to natural, political, and/or social factors, which often complicate project elements, such as communication management, stakeholder management, and procurement management (Cusworth and Franks, 2013; Gasik, 2016; Golini et al., 2015). Moreover, sometimes the projects are lengthy in nature, and procurement challenges are one of the major reasons for project delays (Ahsan, 2012; Ahasan and Paul, 2018). Similarly, the procurement of public-sector projects in Bangladesh faces several challenges since the country has weaknesses in its organizational and staff capacity, information management, procurement practices, effective procurement, and accountability (Parvez, 2016). Other factors that also affect public procurement in Bangladesh include a wide range of corruption, political control, pressure from different types of trade unions, and so forth. Ideally, procurement management should be more accountable to ensure good governance in public procurement (Mahmood, 2010). In particular, political influence causes problems with procurement in development projects in Bangladesh, such as politically motivated advertisements, a short bidding period, disadvantaged specifications, and rebidding without adequate grounds (Hamiduzzaman, 2014). As a result, many of the government regulatory agencies in the country have recently expressed increased concerns about the issues of development project implementation, particularly in regard to conducting procurement. Also, the international development partners who fund and oversee programmes in the country express similar concerns (Ahsan and Paul, 2018; Khan et al., 2022).

Since the development projects are designed to increase productivity or increase a country’s returns on investment in agriculture, they significantly contribute to effective agricultural development. This is essential not only for economic development but also for food security and agricultural sustainability (Gil et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2022). Likewise, as an agrarian and developing country, the government of Bangladesh implements agriculture development projects not only to increase crop productivity but also to ensure the country’s long-term agricultural viability. Generally, the project funds come from two sources: the Government of Bangladesh (GoB) revenue, and international development partners. All of these projects are designed, implemented, monitored, and evaluated under the guidelines of the Ministry of Planning, the Planning Commission, respective ministries, and implementing agencies using the Annual Development Programme (ADP) of the country (Hamiduzzaman, 2014). Currently, the government is implementing 168 public-sector agriculture projects in Fiscal Year (FY) 2020-21 each with its specific budgets, targets, and durations. As per the project completion report of the FY 2016-17, most of the projects were GoB funded, and almost 80% of the projects went over budget and time due to some common issues: delayed project commencement, delayed deployment of the key staff, improper procurement planning, delay in land acquisition, natural disasters, improper budgeting, wrong estimation and forecasting, improper supply-chain management, and project revision (Implementation Monitoring and Evaluation Division (IMED), 2020; Planning Division (PD), 2020).

Agricultural development projects face a specific set of challenges (i.e., environmental hazards) compared to other types of projects (i.e., construction projects) because most of the projects are season-specific and implemented with the common goal of increasing crop productivity, which is entirely or partially dependent on environmental factors (Khan et al., 2022). As a result of such critical project scopes, procurement may also be impacted (Ahsan and Paul, 2018; Khan et al., 2022a). Furthermore, Bangladesh, like other developing countries, faces a lack of resources and a variety of adverse environmental conditions while managing projects. It is important to identify and evaluate the key challenges to project procurement based on their importance and interdependence, so that project professionals can deal with those challenges in a way that maximizes the value of public money while conducting the procurement.

However, as there is no substantial research work on project procurement challenges, particularly in the case of public-sector agriculture projects in a developing country’s context, this study investigated the challenges from the viewpoint of project professionals with the following specific research questions:

RQ1. What are the most important procurement challenges for public-sector agriculture projects in Bangladesh?

RQ2. What are the contextual relationships among the challenges?

Addressing these research questions is critical from a methodological perspective as well as from an applied perspective. This study used an integrated methodological approach: modified Delphi, best worst method (BWM), interpretive structural modelling (ISM), and cross-impact matrix multiplication applied to classification (ISM-MICMAC) methods.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section “Theoretical background” depicts the theoretical background of project procurement management, and a framework capturing the challenges to agriculture project procurement is presented. The methodological framework, composed of the research design and framework along with the modified Delphi, the best-worst method (BWM), interpretive structural modelling (ISM), and ISM-MICMAC, is presented in the section “Methodological framework”. The application of the proposed challenges framework to a real-world case problem in the Bangladesh public-sector agriculture organization is provided in section “A case application”, with the discussion of the result given in the section “Discussion”. The theoretical and managerial implications are explained in the section “Theoretical and managerial implications”. Finally, the paper ends with some brief concluding remarks in the section “Conclusion, limitations, and future directions”.

Theoretical background

Management of public project procurement

Public procurement is one of several government tasks with the potential to help the government achieve its goals by securing goods, work, and services (Bleda and Chicot, 2020; Komakech, 2016). It has enormous potential as a tool for socioeconomic policy implementation: ensuring sustainable development, battling unemployment, integrating socially vulnerable groups, and fostering social development. Therefore, there is no question that public tenders have a significant impact on the nation’s total economy (Bernal et al., 2019; Komakech, 2016). However, there are some obvious differences between public and private procurement, primarily in terms of objectives. While public organizations are more concerned with integrating ethical, social, environmental, democratic, professional, and people-related issues, private organizations are more focused on maximizing profit. In the case of public procurement, the most effective choice is not usually the one that cuts costs. It is, therefore, necessary to give other considerations, such as social ones, a higher priority in a procurement process. Additionally, when it comes to public procurement, bidders are constrained by what the law permits, but private organizations are free to select the best alternative with fewer restrictions. Another aspect of public procurement is the assurance that a supplier will be chosen through a transparent procedure rather than due to politics, favouritism, or fraud. In this way, several issues resulting from a poorly run procurement process helps explain why some public services are not providing value. As a result, in some instances, public projects are cancelled (Guarnieri and Gomes, 2019).

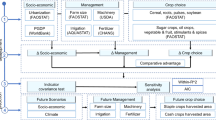

Project procurement management deals with the processes necessary to source or acquires products, services, or results needed from outside the project team (Project Management Institute (PMI), 2017). The process involves three of the five process groups within the project lifecycle (Fig. 1) (Khan et al., 2022; Project Management Institute (PMI), 2017): planning, executing, and monitoring and controlling. Since the procurement plan is a component of the project management plan, it is carried throughout the project’s lifecycle. The procedure is determined by the project’s scope (Project Management Institute (PMI), 2017).

In the case of public project procurement management, the procurement is carried out in accordance with the relevant government’s procurement rules and regulations. The procedure must also adhere to the project management plan and scope. There has been limited research on the public project procurement management process and how it ensures value for money while adhering to both government procurement legislation and project scopes. Accordingly, the study employed the Theory of Change to describe and illustrate how and why the process is expected to provide value for money (Fig. 2). The tool is widely used in government programme planning and prioritization (Reddy and Mehjabeen, 2019). Because each project’s goals, challenges, and scope are unique (Khan et al., 2022), the theory has been applied to demonstrate the process along with the expected outcomes (Chartered Institute of Procurement & Supply (CIPS), 2019); Guarnieri and Gomes, 2019; Khan et al., 2022; Komakech, 2016; Project Management Institute (PMI), 2017).

Project procurement planning begins during the project’s planning phase. Thus, assessing and justifying procurement needs during the period would be phenomenal for developing a more effective procurement plan. If the enterprise environmental factors (i.e., internal, and external policies, practices, procedures, and legislation) and organizational process assets (i.e., an organization’s formal and informal plans, policies, procedures, and guidelines) are properly evaluated at this stage, it will help to identify the challenges and appropriate procurement strategy. Similarly, market analysis is required to understand the present status of the market, products, and vendor availability. To ensure proper planning and assumptions, the project procurement plan should properly evaluate challenges and risks that exist within the project scope, products, vendor, and procurement strategy. It is strongly recommended to start pre- and post-procurement evaluations, which are required to guide the procurement’s current and future strategies. Fair competition is considered an important component of public procurement, so it is essential to adequately advertise the bids so that all potential vendors can compete, resulting in value for money. Government regulations need to be followed carefully during the vendor evaluation and selection processes so that the process may be more accountable and transparent. An effective procurement plan and contracts are required for effective contract performance monitoring. Therefore, the documents should be prepared with proper justification. After contracts are awarded, supplier management is critical to the procurement’s success. Because the projects are distinct in the various characteristics that distinguish them from operations, each stage of the procurement process presents new challenges. As a result, it is highly recommended to identify challenges to public project procurement because the process is more complicated compared to other general public procurement due to the unique scope of the project and the government’s rigid regulations.

Framework for public sector agriculture project procurement challenges

Drawing from the literature review, this study presents a project procurement challenge framework (Table 1) comprising three challenge categories and thirteen challenges. Due to the lack of substantial research on public-sector agriculture project procurement challenges, particularly in the context of a developing country context, the framework captures procurement, logistics, and supply-chain issues beyond the agriculture sector of both developed and developing countries. The description of the challenges and challenge categories has also been adapted from the literature and is discussed in the following subsection.

Contextual issues

Contextual challenges in project management are related to host country circumstances or problems that arise from the project’s contextual basis. The topic involves the host country’s political situation and political influence, as well as social issues and demographic and environmental concerns (Ika and Donnelly, 2017; Ahsan and Paul, 2018). The literature suggests that developing countries face several problems due to their distinctive natural, demographic, political and/or social characteristics (Ahsan and Paul, 2018; Golini et al., 2015; Ika and Donnelly, 2017; Khan et al., 2022). Consequently, this study has included the following challenges as contextual issues:

(a) Political influence: In a developing country, political willingness and influence have a substantial impact on not only project management and procurement policy formation, but also import restrictions and changes in policies. Sometimes, the influence also delays project initiation, and procurement execution (Ahsan and Paul, 2018; Ika and Donnelly, 2017; Khan et al., 2022; Williams, 2017).

(b) Government bureaucracy: It causes delays in project approval, key staff deployment, and fund release systems, as well as lengthening the project/procurement approval process (Ahsan and Paul, 2018; Ika and Donnelly, 2017; Khan et al., 2022; Williams, 2017). In particular, the public-sector project planning phase in Bangladesh is bureaucratically initiated, implemented, and evaluated. Such excessive bureaucracy has a negative effect on the projects’ success (Hamiduzzaman, 2014).

(c) Frequent movement or transfer of key project personnel: In the case of public-sector projects in developing countries, the Project Implementation Unit (PIU) of the project works under a matrix organization, and the project managers, along with key staff, are national civil servants appointed by the government. Accordingly, staff might need to move or transfer to other projects or sections as per the desire of their higher authority, which could affect the project and project procurement activities (Ahsan, 2012; Ahsan and Paul, 2018; Ika and Donnelly, 2017).

(d) Delay of key staff hiring: In developing countries, key personnel for public-sector projects is delegated from other government organizations because they are government civil servants. Consequently, to some extent, their deployment process is delayed due to bureaucratic processes, which might lead to hindering not only the project procurement process but also the project implementation (Ahsan and Paul, 2018; Ika and Donnelly, 2017; Khan et al., 2022).

(e) Improper communication: In developing countries, a lack of communication between the PIU and key stakeholders can stymie the procurement and fund release system (Ahsan and Paul, 2018).

Project management issues

The project management issues include the organizational project management capacity that includes unclear project objectives, imperfect project design, and delays between project identification and initiation (Ahsan and Paul, 2018; Ika, 2015; Kwak, 2002). Due to poor infrastructure and a lack of efficient resources, projects in developing countries suffer in managing their activities, so projects become more complex (Landoni and Corti, 2011). Similarly, in Bangladesh, public-sector projects also experience such limitations. In particular, the projects face challenges in their planning and implementation phases (Hamiduzzaman, 2014; Khan et al., 2022). The following outlines these challenges:

(a) Delay in project initiation: The projects experience a delayed start since it takes a long time to initiate a project after the identification, which hampers not only timely deliverables but also the project’s success (Ahsan and Paul, 2018; Khan et al., 2022). Delayed start of a project might affect the entire procurement plan and its execution.

(b) Improper planning: Projects face critical problems during the implementation phase due to a lack of detailed and realistic plans on schedule, budget, and procurement methodologies, which act as barriers to optimizing project values (Ahsan and Paul, 2018; Cusworth and Franks, 2013; Dzuke and Naude, 2017; Hamiduzzaman, 2014; Khan et al., 2022).

(c) Frequent design change/scope creep: Frequent design changes or scope creep are a very common problem that projects in developing countries face; as a result, projects must frequently be revised and/or replanned during the implementation stage, resulting in a change in project scope (Handayati et al., 2015; Sharma and Bhat, 2012; Yazdani et al., 2019).

(d) Lack of competent staff: Lack of a competent project team is another common problem that projects face in developing countries since the implementing agencies suffer due to a lack of competent staff and a lack of institutional capacity (Ahsan and Paul, 2018; Golini et al., 2015; Khan et al., 2022).

(e) Lack of contract monitoring mechanism: Often, projects are hampered by a lack of the required contract monitoring mechanism; this is due to a lack of both logistical support and manpower, as well as legislation. Sometimes, the procurement entities could not take the necessary actions against the non-performing contractors and suppliers due to a lack of penalty provisions in the prevailing procurement legislation (Dzuke and Naude, 2017; Khan et al., 2022; Zakaria and Arifeen, 2013).

Ethical issues

Ethical issues in project procurement might include collusive tendering, conflicts of interest, bid shopping, corruption, and bid cutting (Ahsan and Paul, 2018; Schwartz, 2009). The following sub-sections discuss the major ethical challenges of procurement.

(a) Bias in developing a procurement plan: When the government sources something for a project, the planning stage is very important to make sure that the decision-making process is open and accountable (Aliza et al., 2011). Sometimes, influential stakeholders and political leaders may advocate their own projects for political gain (Khang and Moe, 2008). Due to the bias in developing a procurement plan, the procurement entity might not be able to ensure a competitive price during the tender/bid (Khan and Rahman, 2014).

(b) Unfairness in procurement contracts and tenders: During the tendering and contract-awarding stages, some manipulation of listed procedures, kickback for procurement contracts, and influence on the choice of the contractor may occur (Khan et al., 2022; Williams, 2017). While informal payments are a common issue in developing countries, where the sellers pay an additional percentage of the contract value as a bribe to secure government purchases (Estache, Limi, 2008).

(c) Undue practices in procurement implementation: During the contract execution phase in developing countries, there are several corrupt practices in the procurement process. These include the delivery of low-quality materials, lowering specifications to allow substandard products, paying claims that are not backed up, and paying contingency amounts without a solid reason (Khan et al., 2022; Osei‐Tutu et al., 2010; Williams, 2017).

Methodological framework

Research design and framework

In this study, the modified Delphi, best worst method (BWM), and interpretive structural modelling (ISM)-cross-impact matrix multiplication applied to classification (MICMAC) approaches were used as part of an integrated methodological model to identify and evaluate the procurement challenges (PCs) as shown in Fig. 3 (Gupta et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2022; Moktadir et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2019). These techniques have been applied for some specific benefits in addition to their functional goals. Firstly, the techniques have been proven to be highly effective in analysing studies of a similar nature on supply chain and procurement-related issues (John and Ramesh, 2016; Khan et al., 2022; Luthra et al., 2015; Mangla et al., 2014; Moktadir et al., 2018, 2019; Rezaei et al., 2016). Secondly, these tools do not require a large sample size to produce credible data for analysis, which also saves time; on the one hand, in these methods, the expertise of the respondents is more important than the sample size (Khan et al., 2022; Moktadir et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2019). On the other hand, due to a lack of experts in Bangladesh, it has sometimes been hard to get a large number of people to take part in similar types of research (Ahsan and Paul, 2018; Khan et al., 2022a). Thus, considering the nature of the problem and the expected output of the current study, as well as the implications of the methods (Khan et al., 2022), the authors applied the integrated methodological model (Fig. 3) to carry out this study. In this model, the modified Delphi method was applied to identify the most important procurement challenges (PCs). Subsequently, the study applied BWM and ISM-MICMAC tools simultaneously for further evaluation of the PCs. The BWM was applied to rank the PCs by measuring their relative importance. The ISM method and ISM-MICMAC analysis empirically captured the relative dependences and influences among the PCs. A brief description of the methods is provided in the following subsections.

The ‘Modified Delphi’ method

The Delphi method combines the judgemental and situational observations of the respondents to portray a comprehensive picture and provide a better understanding of existing challenges (Gossler et al., 2019; Okoli and Pawlowsk, 2004). The method is commonly used to create expert consensus on complicated, complex, and contentious matters. The method follows five steps (Hsu and Lin, 2013; Khan et al., 2022): (i) selecting experts; (ii) administering the first round of the survey; (iii) administering the second round of the survey, incorporating input from the previous round; (iv) administering the third round of a survey (if necessary); and (v) synthesizing expert perspectives to establish a consensus. The anonymous experts are interviewed during data gathering until a consensus is established. The modified Delphi method, unlike the Delphi method, does not employ an open questionnaire. Alternatively, during the first round, it uses literature to create a closed questionnaire. As a result, the updated procedure often requires fewer rounds of surveying and reaching a consensus (Hsu et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2022, 2022a; Ko and Lu, 2020).

The ‘best worst’ method

The BWM, a novel multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) method, is a highly effective tool to inform decisions regarding real-world problems and defining criteria weight coefficients (Rezaei, 2015; Rezaei et al., 2016). In BWM, the responses are made based on an integer scale of 1–9 which helps to reduce the complexity of comparison. Moreover, the method has been found effective because of its performance in obtaining consistent results (Khan et al., 2022a; Mi et al., 2019; Moktadir et al., 2019; Rezaei, 2015). The stepwise procedure for BWM is summarized below (Khan et al., 2022; Moktadir et al., 2019; Rezaei, 2015):

Step I: Determination of the decision-making criteria

A set of decision-making criteria (i.e, the PCs) necessary to aid the decision are determined.

Step II: Determination of the best criteria (i.e., most important) and the worst criteria (i.e., least important)

In this step, the decision makers or experts identify the most important and least important criteria without using any comparison matrix.

Step III: Determination of the best criteria (i.e., most important) over the other criteria using a 1–9-point rating scale

In this step, the decision makers or respondents construct a matrix identifying the best (most important) criterion B in comparison with the other criteria using a 1–9 scale. The rating scale indicates the preference for one criterion over another criterion. In this case, point 1 on the scale indicates that this criterion is equally important to the other criterion; whereas point 9 denotes that the identified criterion has much higher importance than another identified criterion. The resulting best-to-others (BO) vector for the rth respondent of identified criteria can be formulated as follows:

In this matrix, the notation \(x_{Bj}^r\) presents the importance of the best criterion B compared to criterion j. Therefore, the value of \(x_{BB}^r\) is equal to 1.

Step IV: Determination of the order preference of all other criteria over the worst criteria (i.e., least important) using a 1–9-point rating scale

The respective respondent (r) constructs a decision vector of the other criteria and, firstly, determines the worst (least important) criterion W using the 1–9 scale. The vector can be written as follows:

where, the notation \(x_{jW}^r\) represents importance of criterion j over the worst (least important) criterion W, and the value of \(x_{WW}^r\) would be 1.

Step V: Ascertaining the optimal weightings of decision-making criteria \(\left( {w_1^{r^ \ast },\,w_2^{r^ \ast },\, \ldots ,\,w_n^{r^ \ast }} \right)\)

Finally, here optimized criteria weighting is determined such that the maximum absolute difference for all j is minimized for the following set:

The problem is converted and formulated as follows:

subject to

\(w_j^r \ge 0\) for all j.

Equation (1) can be formulated as a problem of linear programming, and can be written as follows:

min.ξL*

Subject to, \(\left| {w_B^r - x_{Bj}^rw_j^r} \right| \le \xi ^L\) for all j

wj ≥ 0 for all j

The optimal weights \(\left( {w_1^ \ast ,\,w_2^ \ast , \ldots ,\,w_n^{r \ast }} \right)\) are computed while minimizing the value of ξL*. The consistency of the results obtained is justified by the value of ξL*. The closer the value is to zero, the more consistent the system is and the more dependable the comparison, and vice versa. In addition, the consistency ratio (CR) threshold table can also be applied to determine the level of reliability (Rezaei, 2015; Liang et al., 2020).

ISM method

The ISM method develops the contextual relationship between the variables, and the expert opinions are collected using some group-based data collection techniques (John and Ramesh, 2016; Luthra et al., 2015) such as brainstorming sessions, nominal technique, focused group discussion. The method is not only applicable to analysing the interrelationships among the variables but also to developing a systematic model based on the relationship (Mangla et al., 2014). This study applied the method since it is widely applicable in different fields of procurement and supply chain management (Gopal and Thakkar, 2016; Khan et al., 2022; Luthra et al., 2015; Raut et al., 2017; Sivaprakasam et al., 2015). Basically, ISM incorporates eight steps as shown in Fig. 4 (Khan et al., 2022; John and Ramesh, 2016; Luthra et al., 2015; Mahajan et al., 2013; Moktadir et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2019): identification of the attributes (i.e., PCs); development of the contextual relationships among the attributes; structural self-interaction matrix (SSIM) development; development of the reachability matrix (RM), partitioning of different levels using the final reachability matrix; formation of digraph; formation of ISM model; and testing of the ISM model for any theoretical inconsistency.

MICMAC analysis

Based on the principle of multiplication of properties of matrices, the MICMAC analysis develops a graph classifying the attributes (Sharma et al., 1995). The graph is developed based on the attributes’ (PCs) dependence and driving power derived from the canonical matrix found in the ISM analysis (Khan et al., 2022; Mahajan et al., 2013; Sivaprakasam et al., 2015). The graph classifies four clusters (Cluster I—Independent enablers, Cluster II—Linkage enablers, Cluster III—Autonomous, and Cluster IV—Dependent enablers) (Duperrin and Godet, 1973; Mahajan et al., 2013; Sharma et al., 2019; Sivaprakasam et al., 2015). The autonomous cluster attributes have low driving power and dependencies, as well as a disconnect from the system. While the dependent cluster contains attributes with low influential power and high dependency, the linkage cluster contains attributes with both high driving power and high dependency. These attributes not only influence other attributes but are also influenced by others. In addition, the attributes have high driving power and low dependency within the independent cluster.

A case application

Selection of a case study public organization

In this study, we investigate one of the largest public-sector agricultural organizations under the agriculture ministry in Bangladesh. The key objective of the organization is to ensure food security, as well as commercial agriculture, with a view to accelerating the socio-economic development of the country. The project-based organization implements projects with a focus on advisory services, dissemination of new crop varieties at the field level, agricultural infrastructures, sourcing of equipment and machineries, ICT in agriculture, agro-climate, dissemination of new technologies (i.e., farming technologies and equipment), agribusiness and marketing, human resource development, safe food production and agricultural research activities. All public sector projects in the country are required to adhere to the same set of guidelines established by the government for both project management and project procurement (Khan et al., 2022). In addition, participants from DAE projects of varying sizes and scopes are considered. Accordingly, it would be justified to use the organization along with its projects as a case study to represent public sector agriculture projects in Bangladesh and look into the challenges with project procurement in the public sector agriculture sector in Bangladesh.

Data collection and evaluation

Phase 1

In the beginning, a challenging framework (Table 1) with 13 challenges and three major challenge categories was identified from the literature review as described in the section “Theoretical background”. Subsequently, these challenges were verified by 15 industry experts (Table S1) having 4–10 years of professional experience in managing project procurement. Even though there is no set number of experts needed for the Delphi method, 10–30 experts with special knowledge or experience are recommended to get the best results (Ameyaw et al., 2016; Bouzon et al., 2016; Hsu and Lin, 2013; Khan et al., 2022). The study applied snowballing and purposive techniques to select the experts (Ahsan and Paul, 2018; Khan et al., 2022). A semi-structured questionnaire was applied to collect the experts’ responses based on their knowledge and professional experience to verify the challenges along with the framework. The experts were permitted to modify, add, or remove any irrelevant criteria from the framework. Being a single mental model, the modified Delphi method allows the respondents to upgrade the framework until they reach a consensus (Gupta et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2022; Sharma et al., 2019). By voting “Yes/Acceptance” or “No/Rejection” on each of the challenges presented, the consensus was obtained in the second round of Delphi. Finally, the challenge framework having ten key PCs (Table 2) and their three main categories has been finalized based on the consensus of the majority (>50%) of the experts’ viewpoints (Dajani et al., 1979; Heiko, 2012; Khan et al., 2022; Loughlin and Moore, 1979).

Phase 2

During this phase, the identified 10 PCs were ranked based on their relative importance using the BWM method, as described in the section “Methodological framework”. Purposive and snowballing techniques were used to collect the BWM data from the eight industry experts (Table S2) who participated in the Delphi rounds and have 7–10 years of experience (Gupta et al., 2017; Khan et al., 2022; Moktadir et al., 2018, 2019). The interviews were conducted with the structured BWM questionnaires through face-to-face interviews and electronic communication. Firstly, the experts identified the best (most important) and worst (least important) PCs from the challenge list. Secondly, they constructed the best-to-other and other-to-worst matrices using the 1–9 BWM rating scale. Following the BWM analysis, the experts’ feedback was used to identify the most significant PCs as mentioned in the section “Methodological framework”. Initially, each of the category’s optimal weights was obtained by applying the sequential procedures and Eq. (2) (see the section “Methodological framework”). Similarly, the weights of the PCs (Table 3) under specific major categories were also obtained.

Then, the global weights of the PCs were also determined as shown in Table 3. Finally, based on the weights, the PCs were ranked (Rezaei et al., 2016).

Being an MCDM, the BWM results need to be checked for robustness. Thus, after obtaining the rank of the PCs, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to check the robustness of the final ranks of the PCs as shown in Table S3, and Table 4 (Gupta et al., 2017; Khan et al., 2022; Mangla et al., 2015; Moktadir et al., 2019). The analysis reveals that most are not robust between the range of 0.1 and 0.3 weights since the variations of weights between the top-ranked PC category (PMPC) and other categories (CPC and EPC) varied greatly at this range (Table 3). Notably, most of the challenges are robust between the weight 0.4–0.9, particularly the top-ranked challenge (lack of competent procurement staff- \({\rm {PM}}_1^{{\rm {PC}}}\)) was stable at the weights of 0.4–0.9.

However, the consistency ration (CR) of each matrix constructed by respondents was consistent since the weights were found within their threshold level (Liang et al., 2020; Rezaei, 2015), which indicates that the judgements were consistent and acceptable.

Phase 3

In this phase, a brainstorming session was conducted to get the opinions of the 10 experts to identify and evaluate the interrelationships among the 10 PCs found from the Delphi rounds as outlined in the section “Methodological framework” and the flow chart (Fig. 4). Initially, the structured self-interaction matrix (SSIM) of the PCs was formulated using the PCs (Table S5) drawing from the 10 industry experts (Table S4) who specialize in public-sector agriculture project procurement management with 7–20 years of experience, and the experts were selected using the purposive technique (John and Ramesh, 2016; Khan et al., 2022; Luthra et al., 2015; Moktadir et al., 2019). Of the 10 experts, two were procurement consultants, with 20 years of experience, and the remaining eight were selected from the same panel that participated in the BWM interview sessions. The final reachability matrix (Table S6), level partitioning (Table S7), and the ISM model (Fig. 5) were subsequently developed. One academic expert who specializes in procurement and supply chain management and has 10 years of experience in relevant fields was involved in verifying the ISM analysis results, and after his final judgement, the ISM results were finalized as illustrated in Fig. 4 (Khan et al., 2022; Moktadir et al., 2019).

Phase 4

In this last phase, an ISM-MICMAC analysis was conducted as outlined in the section “Methodological framework”. The driving and dependence power of each PC derived from the canonical matrix found in the ISM analysis (Table S6) were used in this analysis to identify four clusters of the challenges as shown in Fig. 6.

Discussion

Identification and ranking of the PCs

The study identified ten significant procurement challenges (Table 2) using the modified Delphi methodology, which was crucial for the management of public sector agriculture project procurement. The three challenges—frequent movement or transfers of key project personnel; a delay in project start-up; and frequent changes in project design—were omitted from the initial list of challenges (Table 1) compiled through a review of the literature. Because these development projects are part of government initiatives, the project procurement plan can be revised in accordance with the government’s requirements using certain guidelines. Therefore, compared to other challenges, these PCs might not have been regarded as the most pressing concern.

From the BWM analysis (Table 3), in terms of importance, the challenge ‘lack of competent procurement staff’ is found to be the top-ranked challenge since it received the highest weight (0.2489). Similarly, it is reported that the lack of a competent workforce is one of the key barriers to public project procurement in Bangladesh (Ahsan and Paul, 2018; Hamiduzzaman, 2014; Mahmood, 2010).

Sometimes, it is claimed that the public-sector projects of the country suffer due to a lack of personnel having proper procurement knowledge (central procurement technical unit (CPTU), 2019). While the challenge ‘improper planning’ \(\left( {{\rm {PM}}_1^{{\rm {PM}}}} \right)\) (0.2350) was found to be the second-ranked challenge. Similarly, the challenge is also reported as the most critical challenge to procurement in public sector international development projects in Bangladesh (Ahsan and Paul, 2018; Khan et al., 2022). Likewise, this study finds that public projects are designed with a lack of detail and realistic budget and procurement, as well as poor or no analysis of critical risk factors and contingency planning. Similarly, this challenge is apparent in other developing countries (Aliza et al., 2011). However, this study finds the top-ranked two challenges are very close in terms of their global weights (Table 3); therefore, these two PCs might be considered the most important challenges in public-sector agriculture projects in Bangladesh.

The challenges- ‘\(\left( {C_2^{{{{\mathrm{PC}}}}}} \right)\) government bureaucracy’, ‘\(\left( {C_1^{{{{\mathrm{PC}}}}}} \right)\) political influence’, ‘\(\left( {E_2^{{\rm {PC}}}} \right)\)unfairness in procurement contract and tendering’, ‘\(\left( {{\rm {PM}}_3^{{{{\mathrm{PC}}}}}} \right)\) lack of contract monitoring mechanism’, ‘\(\left( {E_3^{{\rm {PC}}}} \right)\) undue practice in procurement implementation’, ‘\(\left( {C_3^{{{{\mathrm{PC}}}}}} \right)\) delay of key staff hiring’, ‘\(\left( {C_4^{{{{\mathrm{PC}}}}}} \right)\) improper communication’, and ‘\(\left( {E_1^{{\rm {PC}}}} \right)\) bias in developing procurement plan’ are positioned between the 3rd and 10th positions, respectively (Table 3). Since Bangladesh is a developing country, public sector projects there might face these common problems. Institutions in developing countries often lack qualified staff, logistical support, administrative skills, and technologies (Ahsan, 2012; Ahsan and Paul, 2018; Hamiduzzaman, 2014; Khan et al., 2022; Yazdani et al., 2019).

Contextual relationship of the PCs

The ISM result finds the challenge ‘\(C_1^{{{{\mathrm{PC}}}}}\) political influence’ in level IV (the bottom level) of the ISM model (Fig. 5), and it has strong driving power but the lowest dependence power (Table S6) since it directly or indirectly influences most of the challenges. Similarly, it is revealed that the administrative culture in Bangladesh is highly dependent on the political environment (Hamiduzzaman, 2014; Islam, 2016). Moreover, such a culture has both positive and negative effects on the public-sector projects’ performances: the implementation of some particular projects is conducted timely and efficiently because these projects are part of the political manifesto of the ruling political party, and the parties are committed to implementing such projects within the project period; whereas, many projects have to suffer due to some illegal political influences throughout the project life-cycles, and this scenario is very common in developing countries (Ahsan, 2012; Ahsan and Paul, 2018; Hamiduzzaman, 2014).

The challenge ‘\(\left( {C_3^{{\rm {PC}}}} \right)\) delay of key staff hiring’ from level III (Fig. 5), is influenced by the challenge of‘ political influence’ from level IV since political culture influences the overall administrative functions of the country. On the other hand, the challenge \(\left( {C_3^{{\rm {PC}}}} \right)\) influences directly the two challenges of level II: ‘\(\left( {{\rm {PM}}_1^{{\rm {PC}}}} \right)\) lack of competent procurement staff’ and ‘\(\left( {E_1^{{\rm {PC}}}} \right)\) bias in developing procurement plan’. Delayed key staff (i.e., Project Manager) hiring might result in a shortened project period, which might influence the two challenges since it might not be possible to recruit competent procurement staff within the very short project period. Similarly, the biased procurement plan might be another consequence, as the project team might show bias in developing the procurement plan so that they can complete the procurement within a limited period. While the other challenge ‘\(\left( {C_2^{{\rm {PC}}}} \right)\) government bureaucracy’ also influences these two challenges (\({\rm {PM}}_2^{{\rm {PC}}}\) and \(E_1^{{\rm {PC}}}\)) directly and indirectly as shown in Fig. 5. Thus, these three challenges (\(C_2^{{\rm {PC}}}\), \({\rm {PM}}_2^{{\rm {PC}}}\), and \(E_1^{{\rm {PC}}}\)) are positioned in level II. The rest of the five challenges belong to the top level (level I) since these challenges are influenced directly or indirectly by level IV, III, and II challenges (Fig. 5).

The ISM-MICMAC analysis reveals (Fig. 6 and Table S6) that most of the BWM top-ranked challenges (1–5 ranked challenges) are found in cluster II (linkage PCs) since they have strong driving and dependence power. So, the cluster II challenges are unstable, and any action on these challenges would influence others (Mahajan et al., 2013). Therefore, these challenges are very crucial for procurement. The results indicate that the level IV and III challenges (political influence, and delay of key staff hiring) in cluster I (the independent PCs) have strong driving power but weak dependent power (Fig. 6 and Table S6). As a result, these challenges need to be addressed as well, because they have an impact on all other challenges, either directly or indirectly.

Theoretical and managerial implications

This study contributes significantly to the existing body of knowledge in the following ways: (i) application of modified Delphi, ISM, and ISM-MICMAC methods in analysing PCs in public-sector agriculture projects, particularly in a developing country; ii) the challenge framework (Table 2) and the ISM model (Fig. 5) are also two unique contributions, as there is no challenge framework or structural model for public-sector agriculture project procurement challenges in the existing literature. Consequently, these findings would constitute a novel contribution that would provide project professionals and future researchers in Bangladesh and other developing nations with useful insights. In the following ways, the findings may be particularly useful for those involved in the design, management, and formulation of public-sector agriculture projects:

The top-ranked challenges have a more negative impact on the project than other challenges, so the project professionals must first concentrate on the top 10 PCs with their rankings.

Secondly, the project professionals should follow not only the ranks of the PCs but also their driving and dependence power to address the challenges more effectively because they might have some linkage with other challenges. Subsequently, it might need a holistic approach to address all the linked challenges in order to control or mitigate a particular challenge. The MICMAC analysis recommends that the cluster I and II challenges need to be addressed with great attention due to their strong driving power. As a result, professionals should use the MICMAC analysis results in conjunction with the ISM model to identify challenges that have a strong linkage and influence with the challenge.

Finally, the findings may be useful to policymakers in Bangladesh who are developing policies, rules, and/or guidelines for managing procurement in public-sector agriculture projects. Furthermore, the findings have the potential to inform international development partners who fund agricultural projects, as the projects are frequently designed as joint ventures, but the procurement is generally conducted in accordance with the host country’s public procurement laws.

Conclusion, limitations, and future directions

In light of the relative paucity of the literature, the study investigates the procurement challenges in public-sector agriculture development projects in a developing country context (i.e., Bangladesh). The study identifies ten key challenges in terms of their relative importance.

Among them, based on their optimal weights, ‘lack of competent procurement staff’ is identified as the most significant challenge, whereas the challenge—‘political influence’ is found to be the most influential based on the inter-relationship among the challenges. It is strongly advised that professionals consider not only the optimal weights of the challenges and their rankings but also their relative dependences and influences, in order to address all of these key challenges in a holistic manner. Thus, the project professionals who are involved in managing public-sector agriculture projects in Bangladesh should focus on the top-ranked procurement challenges (lack of competent procurement staff, improper planning, government bureaucracy, political influence, and so on) to support effective procurement management. Procurement may suffer if the professionals do not address any of these challenges appropriately. While professionals should also consider the ISM model to address different levels of challenges and their interrelationships. In general, as per the MICMAC analysis, the professionals should address the independent challenges (political influence, and delay in key staff hiring) and the linkage challenges (most of the BWM top-ranked challenges) with great attention because of their higher driving powers. Since there is limited research on this topic, the results are also useful for academics and policymakers.

There are some limitations to this study. Initially, the study included most of the challenges from the literature that were not directly relevant to public-sector agriculture project procurement but procurement and supply-chain issues in other industries, because there is no substantial research work or literature on public-sector project procurement issues, particularly from the perspective of developing countries. Furthermore, to some extent, it can be claimed that the BWM and ISM techniques are biased and may lead to unbalanced results since these methods are mostly dependent on the feedback of the expert panel. In addition, other MCDM tools such as Fuzzy-BWM, Fuzzy-ISM, or TISM might also be applied to conduct the research. To make the study more interesting, an additional analysis (i.e., correlation or Kendall Tau) could be conducted to identify possible interdependence among the ranks identified by the BWM analysis. Although the purpose of the study was to determine the procurement challenges faced by public sector agriculture project professionals, including the perspectives of other stakeholders (i.e., project beneficiaries, vendors, etc.) from other public sector agricultural organizations would have added a valuable new dimension to the study, which was not done. Future researchers conducting this type of investigation may consider these issues. However, considering the pros and cons of the applied methods found in the literature, the researchers believe that the integration of the Delphi, BWM, and ISM-MICMAC model provides useful insights, and such an approach might also be recommended in other service or industry domains to conduct similar research.

Data availability

Full access to the datasets generated and analysed during the present study is available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/OCIYNE

References

Ahsan K (2012) Determinants of the performance of public sector development projects. Int J Manag 29(1):77

Ahsan K, Paul SK (2018) Procurement issues in donor-funded international development projects. J Manag Eng 34(6):04018041(1)–04018041(13). https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000648

Aliza AH, Stephen K, Bambang T (2011) The importance of project governance framework in project procurement planning. Procedia Eng 14:1929–1937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pr

Ameyaw EE, Hu Y, Shan M, Chan AP, Le Y (2016) Application of Delphi method in construction engineering and management research: a quantitative perspective. J Civ Eng Manag 22(8):991–1000

Bernal R, San-Jose L, Retolaza JL (2019) Improvement actions for a more social and sustainable public procurement: a Delphi analysis. Sustainability 11(15):4069. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154069

Bleda M, Chicot J(2020) The role of public procurement in the formation of markets for innovation J Bus Res 107:186–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.032

Bouzon M, Govindan K, Rodriguez CMT, Campos LM(2016) Identification and analysis of reverse logistics barriers using fuzzy Delphi method and AHP Resour Conserv Recycl 108:182–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2015.05.021

Central Procurement Technical Unit (CPTU) (2019) Skills of project directors in public procurement underscored. Public Procure 10(23):6. https://cptu.gov.bd/upload/publication/2019-11-27-15-47-14-Newsletter-DIMAPPP-May---July--2019.pdf

Chartered Institute of Procurement & Supply (CIPS) (2019) Scope and influence of procurement and supply. The Chartered Institute of Procurement & Supply, Stamford, Lincolnshire.

Cusworth JW, Franks TR (2013) Managing projects in developing countries. Routledge.

Dajani JS, Sincoff MZ, Talley WK (1979) Stability and agreement criteria for the termination of Delphi studies. Technol Forecast Soc Change 13(1):83–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-1625(79)90007-6

Dzuke A, Naude MJ (2017) Problems affecting the operational procurement process: a study of the Zimbabwean public sector. J Transp Supply Chain Manag 11(1):1–13. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-5d291983e

Duperrin JC, Godet M (1973) Methode de hierarchisation des elements d’un systeme. Rapp. Economic CEA:45–51

Estache A, Limi A (2008) Procurement efficiency for infrastructure development and financial needs reassessed. Policy Research. Working Paper: 4662. World Bank, Washington, DC

Gasik S (2016) Are public projects different than projects in other sectors? Preliminary results of empirical research. Procedia Comput Sci 100(100):399–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2016.09.175

Gil JDB, Reidsma P, Giller K, Todman L, Whitmore A, van Ittersum M (2019) Sustainable development goal 2: improved targets and indicators for agriculture and food security. Ambio 48(7):685–698. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-018-1101-4

Golini R, Kalchschmidt M, Landoni P (2015) Adoption of project management practices: the impact on international development projects of non-governmental organizations. Int J Proj Manag 33(3):50–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2014.09.006

Gopal PRC, Thakkar J (2016) Analysing critical success factors to implement sustainable supply chain practices in Indian automobile industry: a case study. Prod Plan Control 27(12):1005–1018. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2016.1173247

Gossler T, Falagara Sigala I, Wakolbinger T, Buber R (2019) Applying the Delphi method to determine best practices for outsourcing logistics in disaster relief. J Humanit Logist Supply Chain Manag 9(3):438–474. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHLSCM-06-2018-0044

Guarnieri P, Gomes RC (2019) Can public procurement be strategic? A future agenda proposition. J Public Procure 19(4):295–321. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOPP-09-2018-0032

Gupta P, Anand S, Gupta H (2017) Developing a roadmap to overcome barriers to energy efficiency in buildings using best worst method. Sustain Cities Soc 31:244–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2017.02.005

Gupta H, Kusi-Sarpong S, Rezaei J (2020) Barriers and overcoming strategies to supply chain sustainability innovation. Resour Conserv Recycl 161:104819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104819

Hamiduzzaman M (2014) Planning and managing of development projects in Bangladesh: future challenges for government and private organizations. Jm Public Admm Policy Resm 6(2):16–24

Handayati Y, Simatupang TM, Perdana T (2015) Agri-food supply chain coordination: the state-of-the-art and recent developments. Logist Res 8(1):5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12159-015-0125-4

Heiko A (2012) Consensus measurement in Delphi studies: review and implications for future quality assurance. Technol Forecast Soc Change 79(8):1525–1536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2012.04.013

Hsu PF, Lin FL (2013) Developing a decision model for brand naming using Delphi method and analytic hierarchy process. Asia Pac J Mark Logist 25(2):187–199. https://doi.org/10.1108/13555851311314013

Hsu IC, Shih YJ, Pai FY (2020) Applying the modified Delphi method and DANP to determine the critical selection criteria for local middle and top management in multinational enterprises. Mathematics 8(9):1396. https://doi.org/10.3390/math8091396

Ika L (2015) Opening the black box of project management: does World Bank project supervision influence project impact? Int J Project Manag 33(5):1111–1123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.01.005

Ika LA, Donnelly J (2017) Success conditions for international development capacity building projects. Int J Project Manag 35(1):44–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2016.10.005

Implementation Monitoring and Evaluation Division (IMED) (2020) Project completion report. https://imed.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/imed.portal.gov.bd/page/315d64be_c080_478a_8b14_fddea2e03f02/Min%20of%20Agriculture_23_5_20191.docx. Accessed 29 Aug 2020

Islam R (2016) Bureaucracy and administrative culture in Bangladesh. In: Farazmand A (ed) Global encyclopedia of public administration, public policy, and governance. Springer, Cham.

John L, Ramesh A (2016) Modelling the barriers of humanitarian supply chain management in India. Manag Humanit Logist 61–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-81-322-2416-7_5

Khan MR, Alam MJ, Tabassum N, Burton M, Khan NA (2022) Investigating supply chain challenges of public sector agriculture development projects in Bangladesh: an application of modified Delphi-BWM-ISM approach. PLoS ONE 17(6):e0270254. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270254

Khan MR, Alam MJ, Tabassum N, Khan NA (2022a) A systematic review of the Delphi–AHP method in analyzing challenges to public-sector project procurement and the supply chain: a developing country’s perspective. Sustainability 14(21):14215. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114215

Khan S, Rahman S (2014) An importance-performance analysis for supplier assessment in foreign-aid funded procurement. Benchmarking 21(1):2–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-12-2011-0092

Khang DB, Moe TL (2008) Success criteria and factors for international development projects: a life-cycle-based framework. Project Manag J 39(1):72–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmj.20034

Ko WH, Lu MY (2020) Evaluation of the professional competence of kitchen staff to avoid food waste using the modified Delphi method. Sustainability 12(19):8078. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198078

Komakech RA (2016) Public procurement in developing countries: objectives, principles and required professional skills. Public Policy and Administration. Research 6(8):20–29. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234669954.pdf

Kwak YH 2002 Critical success factors in international development project management. In: Uwakweh BO, Minkarah IA (eds) Proceedings of the 10th symposium on construction innovation and global competitiveness. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 358–366

Landoni P, Corti B (2011) The management of international development projects: moving toward a standard approach or differentiation. Proj Manag J 42(3):45–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmj.20231

Liang F, Brunelli M, Rezaei J (2020) Consistency issues in the best worst method: measurements and thresholds. Omega 96:02175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2019.102175

Loughlin KG, Moore LF (1979) Using Delphi to achieve congruent objectives and activities in a paediatrics department. Acad Med 54(2):101–106. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-197902000-00006

Luthra S, Garg D, Haleem A (2015) An analysis of interactions among critical success factors to implement green supply chain management towards sustainability: an Indian perspective. Resour Policy 46:37–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2014.12.006

Mahajan VB, Jadhav JR, Kalamkar VR, Narkhede BE (2013) Interpretive structural modelling for challenging issues in JIT supply chain: product variety perspective. Int J Supply Chain Manag 2(4):50–63

Mahmood SAI (2010) Public procurement and corruption in Bangladesh confronting the challenges and opportunities. J Public Adm Policy Res 2(6):103–111

Mangla SK, Kumar P, Barua MK (2015) Risk analysis in green supply chain using fuzzy AHP approach: a case study. Resour Conserv Recycl 104:375–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2015.01.001

Mangla S, Madaan J, Sarma PRS, Gupta MP (2014) Multi-objective decision modelling using interpretive structural modelling for green supply chains. Int J Logist Syst Manag 17(2):125–142

Mi X, Tang M, Liao H, Shen W, Lev B (2019) The state-of-the-art survey on integrations and applications of the best worst method in decision making: why, what, what for and what’s next. Omega 87:205–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2019.01.009

Moktadir MA, Ali SM, Jabbour CJC, Paul A, Ahmed S, Sultana R, Rahman T (2019) Key factors for energy-efficient supply chains: implications for energy policy in emerging economies. Energy 189:116129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2019.116129

Moktadir MA, Ali SM, Mangla SK, Sharmy TA, Luthra S, Mishra N, Garza-Reyes JA (2018) Decision modelling of risks in pharmaceutical supply chains. Ind Manag Data Syst 118(7):1388–1412. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-10-2017-0465

Okoli C, Pawlowsk SD (2004) The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Inf Manag 42(1):15–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2003.11.002

Osei‐Tutu E, Badu E, Owusu‐Manu D (2010) Exploring corruption practices in public procurement of infrastructural projects in Ghana. Int J Manag Proj Bus 3(2):236–256. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538371011036563

Parvez M (2016) Analyzing public procurement process operational inefficiencies in Bangladesh: a study on Department of Public Health Engineering (DPHE). BRAC University, Dhaka, Bangladesh. http://dspace.bracu.ac.bd/xmlui/handle/10361/7605. Accessed 15 Jul 2021

Planning Division (PD) (2020) The ADP 2020-202, February 2020. Planning Division, Bangladesh. https://plandiv.gov.bd/site/files/ed1482c1-b9af-4b1e-93f9-5b60f1b82613/%E0%A6%8F%E0%A6%A1%E0%A6%BF%E0%A6%AA%E0%A6%BF-%E0%A7%A8%E0%A7%A6%E0%A7%A8%E0%A7%A6-%E0%A7%A8%E0%A7%A7-. Accessed 3 Sept 2020

Project Management Institute (PMI) (2017) A guide to the project management body of knowledge (PMBOK guide), 6th edn. Project Management Institute, Newtown Square, PA.

Raut RD, Narkhede B, Gardas BB (2017) To identify the critical success factors of sustainable supply chain management practices in the context of oil and gas industries: ISM approach. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 68:33–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.09.067

Reddy AA, Mehjabeen (2019) Electronic national agricultural markets, impacts, problems and way forward. IIM Kozhikode Soc Manag Rev 8(2):143–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/2277975218807277

Rezaei J (2015) Best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method. Omega 53:49–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2014.11.009

Rezaei J, Nispeling T, Sarkis J, Tavasszy L (2016) A supplier selection life cycle approach integrating traditional and environmental criteria using the best worst method. J Clean Prod 135:577–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.125

Schwartz MS (2009) Corporate efforts to tackle corruption: an impossible task? The contribution of Thomas Dunfee. J Bus Eth 88(4):823–832. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0318-3

Sharma HD, Gupta AD, Sushil (1995) The objectives of waste management in India: a futures inquiry. Technol Forecast Soc Change 48(3):285–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-1625(94)00066-6

Sharma SK, Bhat A (2012) Identification and assessment of supply chain risk: development of AHP model for supply chain risk prioritisation. Int J Agil Syst Manag 5(4):350–369

Sharma YK, Mangla S, Patil P, Liu S (2019) When challenges impede the process: for circular economy driven sustainability practices in food supply chain. Manag Decision 57(4):995–1017. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-09-2018-1056

Sivaprakasam R, Selladurai V, Sasikumar P (2015) Implementation of interpretive structural modelling methodology as a strategic decision-making tool in a Green Supply Chain Context. Ann Oper Res 233(1):423–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-013-1516-z

Williams MJ (2017) The political economy of unfinished development projects: corruption, clientelism, or collective choice. Am Political Sci Rev 111(4):705–723. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000351

Yazdani M, Gonzalez EDRS, Chatterjee P (2019) A multi-criteria decision-making framework for agriculture supply chain risk management under a circular economy context. Manag Decision 59(8):1801–1826. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-10-2018-1088

Zakaria SM, Arifeen N (2013) Issues and challenges in public procurement bidding: Bangladesh’s experience. The Policy Note of BRAC Institute of Governance and Development, BRAC University, Bangladesh. https://bigd.bracu.ac.bd/study/issues-and-challenges-in-public-procurement-bidding-bangladeshs-experience/. Accessed 21 May 2021

Acknowledgements

This study was a part of PhD research of the first author financially supported by the World Bank-funded National Agricultural Technology Programme, Phase- II (NATP-2) Project (ID: P149553) in Bangladesh. We acknowledge the Bangladesh Agricultural University Research System (BAURES), Bangladesh Agricultural University, Bangladesh for the ethics approval. In addition, we acknowledge the advice of Dr. Bethany Cooper, the University of South Australia on earlier drafts of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

We confirm that all research was performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The questionnaire and methodology for this study were approved by the Ethical Standard of Research Committee of Bangladesh Agricultural University Research System (BAURES), Bangladesh Agricultural University, Bangladesh (Ethics approval number: ESRC/ECON/19; Dated: 25 July 2020).

Informed consent

We confirm that verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or legal authorities.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, M.R., Tabassum, N., Khan, N.A. et al. Procurement challenges in public-sector agricultural development projects in Bangladesh. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9, 447 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01468-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01468-y