Abstract

In public opinion, social and digital media provide means for influence as well as sorting according to pre-existing values. Here we consider types of media usage versus opinion using new polling results in the former Soviet republics (FSRs) of Belarus, Ukraine, and Georgia. Over 1000 individuals in each country were asked about a news event (the January 6 riot at the U.S. Capitol) and about the long-term future of their country. We find that year of birth and country of residence, rather than self-reported media reliance, consistently predicted the respondents’ views, particularly on the future of their country. The timing of these differences suggests a cultural difference between generations growing up in the Soviet Union (likely more pro-Russian) versus afterward, in an FSR (more pro-Western). Whereas digital media choice is somewhat correlated with perceptions of a recent, international news event, the more predictive factors are longer-term cultural values and age cohorts within each nation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In understanding public opinion on geopolitical events, overlapping factors include the influence of mass media, social media, culture, life experience, and socio-economic contexts. Recent interest in social media as spaces for disinformation and propaganda (Agarwal et al., 2017; EIPT, 2020; Horne et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2016, 2019; Weimann, 2015) highlights the potentially rapid change in the balance and variation of these factors. This dynamic situation invites opportunistic observational studies in different countries (Vartanova and Gladkova, 2019), of not only social media versus mainstream mass media in the spread of political opinions, but also politically biased media structures (Benkler et al., 2018) and, even more broadly, the role of individual, generational and cultural memory (Lesthaeghe, 2014; Loftus, 2005).

Culture, as the context for human behavior, differs substantially between nations (Gelfand et al., 2020; Inglehart and Baker, 2000; Inglehart and Welzel, 2005) and underlies behavior, values, beliefs, and perceived realities (Cronk, 1999; Durkheim, 1915; Henrich, 2015). Cultural values represent deeply embedded attitudes and beliefs socialized during formative years (Bianchi, 2014; Cheung et al., 2011; Grusec and Kuczynski, 1997; Sears and Funk, 1999). The imagined identity of nationalism can facilitate social coordination (Anderson, 1991; Chudek and Henrich, 2011). Different cultures vary in the contexts for how contemporary digital media are changing the balance of social transmission of information, including the spread of misinformation and disinformation (Aral et al., 2009; Bond et al., 2012; Gallotti et al., 2020; Garcia-Herranz et al., 2014; Lazer et al., 2014; Ruck et al., 2019; Vosoughi et al., 2018).

Cultural change tends to be inter-generational in time scale because learning from the previous generation is a significant part of socialization (Grusec and Kuczynski, 1997). As a result, cultural values are often more consistent across generations (decades) of birth within each nation than they are by the year the cultural value survey was administered (Ruck et al., 2018). Generational differences arise as each age cohort develops in a changed world, while each cohort’s sociopolitical attitudes tend to be resilient over their life span (Alwin and Krosnick, 1991; Bruce, 2011; Land and Yang, 2013; Ryder, 1965; Stolzenberg et al., 1995). In the 20th century, as new generations adapted to continual technological and socioeconomic modernization (Gorodnichenko and Roland, 2016; Herzer and Strulik, 2017; Varnum and Grossmann, 2017), long-term cultural shifts within nations contributed to inter-generational differences in values and habits (Algan et al., 2010; Foa et al., 2016, Gelfand et al., 2011; Inglehart, 2008; Norris and Inglehart, 2004; Petanjek et al., 2011).

With regard to media influences in public opinion formation, assumptions on how swiftly media-motivated opinion changes might occur vary depending on the theoretical perspective adopted. For instance, a theory that takes a more long-term understanding of media influence is Cultivation Theory. Originated by communications scholar George Gerbner, Cultivation Theory is built upon the premise that mass-disseminated messages create symbolic environments reflective of the ideological structures in which they are produced (Gerbner, 1973; Morgan, 2012). Media influences on people are viewed as long-term with the notion that an individual’s ritualistic exposure to discursive themes repeatedly presented by media shape one’s worldview. In other words, the shaping of social reality does not immediately take place but rather evolves through repeated exposure over a period of time.

Other theoretical approaches (e.g., Elaboration Likelihood Model, Selective Exposure Theory, etc.) to media studies, however, acknowledge the potential for immediate media effects and the existence of reciprocal influences (i.e., not only one-way). For our research, we incorporate Selective Exposure Theory. Under this theory, individuals are driven by their psychological or social needs to select certain media for consumption (Knobloch-Westerwick, 2015). Systematic biases toward certain messages are present. Founded on Cognitive Dissonance Theory (Festinger, 1957), people are thought to avoid information that might cause cognitive discomfort and tend to seek information that aligns with their opinions and attitudes. In media terms, people are motivated to select and consume media content that might validate or secure their beliefs or values. Under this theory, the potential interaction between media messages and the socio-political context in which they are produced is considered.

Both Selective Exposure Theory and Cultivation Theory are relevant to social media, which enable agents to be both producers and consumers of cultural content that can embody individual or shared values (Howard and Parks, 2012). In terms of selective exposure, social media can facilitate homophily, via the sorting of social networks according to cultural dispositions, intrinsic preferences, and/or demographics (Aral et al., 2009; Christakis and Fowler, 2013; Kendal et al., 2018; Shalizi and Thomas, 2011). In terms of cultivation, this sorting of online populations often aligns with political and/or ideological views (Acerbi, 2019; Druckman et al., 2021; Grinberg et al., 2019; Johnson et al., 2019, 2020; Waller and Anderson, 2021). Indeed this sorting is often inherent in the strategies for deploying non-human and meta-human agents that have become pervasive in social media (Botes, 2022; Broniatowski et al., 2018; Ferrara et al., 2016; Horne et al., 2019; Jakesch et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2017; Shah, 2017; Starbird et al., 2018; Zannettou et al., 2019).

Public opinion can also change in response to major events (Bentzen, 2018; Grossmann et al., 2015; Henrich et al., 2019). While events in other countries may have ephemeral emotional impact, local events, and history can resonate for generations (Nunn, 2009), shaping views of other countries in view of past interactions or conflicts (Acemoglu et al., 2001; Becker et al., 2016; Iyer, 2010). Long-lasting narratives may be facilitated by mass and social media (Wagner-Pacifici, 2010, 2017), using new events to reaffirm existing socio-cultural narratives (Darczewska, 2014; Gerber and Zavisca, 2016).

Sorting out these different factors with certainty is difficult to achieve from observational data alone (Aral et al., 2009; Christakis and Fowler, 2013; Shalizi and Thomas, 2011). We can, however, posit hypotheses about expected patterns for an ephemeral news event versus more deeply held geopolitical alignment, under media influence versus characteristics of the different cohorts. Consistent with both cultivation and selective exposure theories, we expect broad geopolitical alignment to be patterned on the year of birth, nationality, and possibly other covariates such as education, as these reflect the conditions of childhood development. Under media influence, by contrast, we would expect attitudes to depend on media choice but not on individual covariates.

This study

Here we explore generational and media-choice effects in the Former Soviet Republics (FSRs) of Belarus, Ukraine, and Georgia, through surveys on the perceptions of two different phenomena—one is an ephemeral, international news event: the January 6, 2021 riot at the U.S. Capitol. The other is the broader, presumably more long-developed view of whether the respondent feels the country is headed toward Russia or the European Union. Complementary information was obtained from questions about respondents’ reliance on domestic vs. Russian media and digital media vs. traditional media. The ages of respondents were recorded as a covariate to their responses.

Current research on interventions to counter dis/misinformation similarly focuses on Western populations and their preferred media (Groh et al., 2022; Nevo and Horne, 2022). Russia is the main source of pro-Russian narratives and disinformation as well as its largest audience. Over time, each of the FSR countries has been subjected to Russian propaganda. The cultural and historical differences among these FSRs, as well as the decade of birth, are among the key variables in investigating the influence of Russian narratives on public opinion in each population. In these FSRs, older generations raised in the Soviet Union may share more cultural values and preferences in common with each other than they do with younger, post-Soviet generations in their own respective FSRs. We would expect attitudinal differences between those who grew up before versus after the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991. In addition to having grown up in the USSR, older generations of FSR citizens also grew up amid Soviet-era narratives, from both family members and the state, about World War II and shared Slavic identity, that posits their shared culture versus that of the European Union (Kozachenko, 2019). In these FSRs, media could play to different generational attitudes toward Russia versus the E.U. (Gaufman, 2015; Kuzio, 2016). During the winter of 2013–2014 in Ukraine, for example, Russian state media invoked neo-Soviet narratives in labeling the new pro-European government as “fascists” and “Nazis’ (Kozachenko, 2019).

Our access to opinions in these countries follows a larger project, which has examined the effectiveness of these Russian narratives in shaping public opinion in these different FSRs through surveys, focus groups, and social media analysis. In Belarus, the government has continued to control traditional media through legislative and surveillance mean, including the power to terminate media operations at any time (Freedom House, 2021; Szostek, 2015). As new digital media channels and social media access became more widespread with the Internet, Belarusians were able to receive more diverse media content. Following the public protests against the outcome of the Belarusian presidential election in 2020, however, the government has progressively placed restrictions on public access to independent media outlets (Freedom House, 2021). In Ukraine, media were relatively free following the collapse of the Soviet Union, with increased press censorship and governmental pressures (Roman et al., 2017), followed by a recent shift toward pro-Western leadership and freer media (Freedom House, 2021). Before the Russian invasion of 2022, Ukrainians had more freely consumed Russian media, as well as Ukrainian media owned by those with close ties to the Kremlin (Polman, 2021).

Methods

Our primary data source for this study comes from a survey conducted in three FSRs. Specifically, we conducted representative surveys administered to random samples of people from Belarus (N = 1014), Ukraine (N = 2000), and Georgia (N = 1000), between April and June of 2021 (Luther et al., 2022). Face-to-face interviews were used in Georgia and Ukraine, but interviews in Belarus were conducted by phone, due to unrest there at the time. Respondents were at least 18 years of age and the samples were representative of the general populations of each country by age, gender, region, and size of settlement (excluding the occupied territories of Donbas and Crimea in Ukraine).

The survey questions, limited in number, aimed to assess the relationship between media consumption and views of the Russian government and its competence. We asked respondents if Russian policies benefit their country, and we inquired regarding their support for or opposition to the European Union ("If you had to choose between improving relations between Belarus (Ukraine, Georgia) and Russia or joining the European Union, which would you choose?”) Additionally, we examined feelings about how the 2021 Capital Riot in the U.S., would affect the standing of the United States politically. Though limited by the logistics of access, these questions addressed attitudes toward the Russian government from various angles, and small focus group interviews were also conducted to verify the relationships identified in the larger surveys.

Ephemeral event versus long-term geopolitical alignment

First, to capture two different types of opinions, we use the responses to two of our survey questions: one about a recent event and one about long-term geopolitical alignment. As described above, we choose these two different types of opinions as they each may be influenced more or less by generational homophily versus media influence.

On the subject of a recent event, respondents were asked their view on the effect of the Capitol riot on U.S. standing in global affairs, with the options: “The U.S. will become stronger”, “No effect”, “The U.S will become weaker” and “Don’t know”. From this, we construct a variable, C, to measure optimism about the U.S. following the event. Treating the responses as ordinal, we assign C = 0 for those who reported “weaker”; C = 0.5 when “no effect” is reported, and C = 1 for respondents who reported “stronger”. As a proxy for differences of opinion on this subject, we compare the proportion of respondents who reported “no effect” (both with and without the “Don’t know” responses) to the proportions who replied either “weaker” or “stronger”.

From the question asking respondents if they preferred improved relations between their country and Russia or their country joining the European Union, we constructed a variable to measure opinions on geopolitical alignment. Again, treating the responses as ordinal, we assign F = 0 for those who reported alignment with Russia, F = 0.5 for those who reported they were uncertain and F = 1 for those who reported alignment with the European Union.

Media influence versus birth cohorts

Next, we captured each respondent’s age and asked respondents about their media consumption habits. In this case, the respondent’s age represents generational homophily, while media consumption habits represent the influence of media.

For media context, respondents were asked: “What are your major sources of information on the events and issues in your country and the world? (Name the three most important)”. Survey respondents could pick from five media groups:

-

Domestic mass media (Dm): TV, radio, or print media located in the country of the survey respondent (Belarusian, Ukrainian, or Georgian mass media).

-

Russian mass media (Rm): TV, radio, or print media located in Russia.

-

Domestic digital media (Dd): Online media, such as blogs or news websites, from the country of the survey respondent (Belarusian, Ukrainian, or Georgian digital media).

-

Russian digital media (Rd): Online media, such as blogs or news websites from Russia.

-

Social media (S): Information from social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Telegram, or Vkontakte.

In our surveys, we defined digital media more narrowly than in most of the literature. Mass media refer to analog media in the forms of print media (i.e., print newspapers, print magazines, etc.), radio broadcasting, film, or broadcast/cable television. In the broad sense, digital media include online websites, social media platforms, blogs, billboards, and entertainment streaming platforms. In our surveys, however, we defined digital media as those providing news and information, including the websites of traditional news media and individual news blogs. In the source options that we provided our survey respondents, we separated digital media from social media in order to identify individuals who solely use social media as sources for information and news. The level of interactivity via social media sites is distinct from what is found via digital news websites or news blogs. Social media entails a network of users interacting at great speed, with popular or leading social media users having more influence over the interactions, especially during key event periods (Pond, 2021). Based on our initial analysis of our data, however, we found little differences between digital media users and social media users and thus, the decision was made to combine the two groups of individuals for our analysis.

Further, the responses to this question were not mutually exclusive, and so we created measures for digital vs. mass media and Russian vs domestic media. For digital vs. mass media (Ec) we use:

For Russian vs. domestic (Qc), we use

Lastly, in our analysis we also include a variant of this media context question, focused on trust rather than simply consumption: “Which of the following information sources do you trust the most? (Name the three most trustworthy)”. This variant had the same answer options as described above. The measures follow the same formulae as Ec and Qc, but will be labelled as Et and Qt, respectively.

Cultural context

As further context to the results from our survey, we incorporated national-scale data on two cultural values, derived previously from multivariate factor analysis of World and European Values Survey data (EVS, 2011; WVS, 2020) in 109 countries (Ruck et al., 2018, 2020a, b). Like our survey, the World Values Survey derives from face-to-face interviews of about 1000 randomly selected individuals in each country—although these are different individuals than in our survey, of course, we aim to compare the data by mean values, aggregated by a decade of birth. The first factor represents secularism (versus religiosity), which is correlated with political engagement, respect for individual rights, and low prosociality (Ruck et al., 2020a). The second capture cosmopolitanism, which reflects how open people are to having neighbors that are foreign or of a different ethnicity (Ruck et al., 2020a).

Logistic regression and marginal effects

Together, these measures were analyzed through 36 multivariate logistic regressions (logistic because the outcome variable is binary), which help control for demographics, such as gender, rural versus urban, wealth, and education. Specifically, 18 logistic regressions were run with U.S optimism (C) as the dependent variable in each country (Belarus, Georgia, and Ukraine), each with an increasing number of controls:

As a reminder, E captures the consumption (or trust) of digital media versus mass media, no matter where that media comes from (domestic or Russian), while Q captures the consumption (or trust) of media from Russia versus domestic, no matter the format of that media (digital or mass media).

These regressions are then repeated with the variables C and F flipped, making respondent’s opinions on their country’s future as the dependent variable.

Importantly, for non-linear regression models—like the logistic regression we use—the effect coefficients are not representative of the actual effect the predictor variables have on the outcome. Therefore, we use partial derivatives over the sample to estimate the marginal effects of the predictors. These marginal effects are unit specific and give interpretable and comparable effects for the predictors of the response to the U.S. Capitol Riot and for the predictors of the response to country alignment. The errors in the marginal effects are the variances in the average marginal effect in the sample. We employed an implementation of this approach from the R package “margins”.

More details about each regression model can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Results

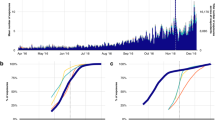

In general, we find that birth year predicts one’s opinion on their country’s future political alignment, from pro-Russian among the old to more pro-E.U. among the young. In aggregate, we find this positive correlation among all the data from the three FSRs pooled together (n = 4000, Pearson’s r = 0.113 [95% CI 0.082, 0.144], p ≈ 10−11). As shown, however, in Supplementary Tables S4, S5, and S6, as well as Fig. 1a, this effect shifts up or down when dis-aggregated across the three countries. Notably, among Belarusians, there is a leveling-off among the older ages, which suggests a Soviet-era effect for people born before the 1970s (Fig. 1a).

Top row: The effect of respondent age on opinions about. a The future political alignment of the country towards Russia versus the E.U., and b U.S standing following the Capitol riot. Bottom Row: Effect of digital media source on those same opinions, in c and d, respectively. Symbol size represents how many responses, n, are averaged by that symbol.

We also find that, unsurprisingly, younger people (later years of birth) rely more on digital media rather than traditional media (Supplementary Fig. S2a). This highlights the difficulty in concluding the year of birth (Fig. 1a) is causal, as one might argue that digital media, consumed more by young people, causes a pro-EU attitude. As shown in Fig. 1c, the more reliance there is on digital media, the stronger the alliance is towards the EU (except the last point on the right, with a small sample size and large variance)—an effect that is strongest in Belarus (see Supplementary Table S5).

These effect of digital versus traditional media needs to be untangled from the effect of Russian versus domestic media, which generally have different biases (depending on the country). As discussed below, the year of birth has little effect on whether people use Russian versus domestic media (Supplementary Fig. S2b). In contrast, reliance on Russian media does correlate significantly with a more Russian-oriented view of the future of one’s country, particularly in Ukraine and Georgia (see Supplementary Tables S4 and S6). Hence, consistent with Cultivation Theory, while the choice of media technology is clearly age-related, it does not appear to be a strong determinant of geopolitical outlook. Instead, what does determine the geopolitical outlook is the consumption of, and trust in, Russian media sources.

Also consistent with Cultivation Theory, other covariates pattern with attitudes toward the country’s future political alignment, but not with the choice of media technology. Increased education and wealth each correlate with a more EU-oriented view of the future country (Supplementary Fig. S1). Across all three FSRs, the strongest overall correlation is between education level and E.U.-oriented view (Pearson’s r = 0.16 [95% CI 0.85, 0.147], p < 0.00001).

In contrast to the effect on opinions about the country’s future, people’s opinions of the Capitol riot show little correspondence with a year of birth (Fig. 1b), and only weak correlation among all data points (n = 4000, Pearson’s r = 0.055 [95% CI 0.015, 0.094], p = 0.007). Indeed, many respondents were not strongly opinionated about the U.S. Capitol riot, with the majority in each FSR replying “No effect” or “Don’t know” to the question (see Table 1). Among those who did have an opinion, Belarusians were most pessimistic about U.S. global standing following the event, and Georgians were most optimistic (see Table 1). Georgians were also more opinionated, with only 24% saying the riot will have “no effect”, as compared to almost 40% in both Ukraine and Belarus. In all three countries, neither education level nor wealth shows an effect on opinions about the Capitol riot.

We can look at how the “no effect” responses break down in each FSR by the Russian-vs.-domestic media measure, Q, and by digital-vs.-mass media measure, E. In each FSR, domestic media users (13–25%) are much more likely than Russian media users (<4%) to reply “no effect” (Table 2). Digital media users (9–18%) were somewhat more likely than mass media users (2–11%) to see an effect (Table 3).

In the lower half of Fig. 1, we see the effect of traditional versus digital media sources on these same dispositions. The relationship in Fig. 1c takes on the expected “softmax” form for how the probability of a binary decision responds to its perceived payoff (Daw et al., 2006) if increased digital media use provides more “payoff” to a more E.U.-oriented view (Fig. 1c). Media preference does not correlate strongly with people’s views on the effect of the Capitol riot on the U.S. (Fig. 1d). In Fig. 1c and d, an exception is among the small number of respondents who selected social, domestic and Russian digital media (x-axis = 3), yielding large standard errors: this presumably reflects the diversity of biases among these different media sources.

A correlation between pro-E.U. and pro-U.S. attitudes would seem to reflect a general pro-Western disposition. Despite age and media factors not playing a significant role in one’s opinions on the U.S. Capitol riot, a pro-E.U. attitude correlates with the opinion that the U.S. will be stronger after the Capitol riot. This association is consistent across all three countries (Fig. 2), also Supplementary Tables S1, S3, and S2).

Within this larger pro-Western disposition, birth year, media choice, and media trust were all correlated with one’s opinion about their country’s future political alignment. Regarding opinion about the U.S. Capitol Riot, however, these three variables did not overall have a significant effect.

Lastly, nation-level cultural factors affect opinions about the country’s future. We see this when we incorporate the cultural factors previously derived (Ruck et al., 2018, 2020a), sliced by country and a decade of birth, and comparing them to our survey responses. For the secular-religious factor, Fig. 3a shows two trends. On an international scale, the more religious the country—from Belarus as the most secular to Georgia as the most religious—the stronger the affiliation with E.U. (Fig. 3a). Within Belarus and within Ukraine, however, are smaller-scale trends that plot orthogonal to the broader one, as younger cohorts have become more secular while becoming also more pro-E.U. (Fig. 3a). In these countries, religious-secular values appear to be primary in their effect, with a year of birth as secondary. This is made more striking by contrast to the relative lack of effect exhibited by the cultural factor of cosmopolitanism (Fig. 3b).

Discussion

Overall, our findings affirm cultivation and selective exposure. We find that generational effects and “deep” cultural values (i.e. not merely current geopolitics) are at least as important as geopolitical factors in determining orientations toward the EU versus Russia in these FSRs (Belarus, Ukraine, and Georgia). Consistent with Cultivation Theory, the cultural values of the FSRs more strongly determine their reaction to a major sociopolitical event—the U.S. Capitol Riot—than media consumption habits. Broad geopolitical preferences aligned with the EU, rather than Russia, consistently predicted a less negative reaction to the Capitol Riot; whereas consuming digital or Russian media had an inconsistent effect.

Media influence had its greatest effect when predicting one’s geopolitical preferences rather than one’s reaction to an ephemeral event, with added effects of age and differences between FSRs. In Ukraine, trust in and consumption of Russian media predicted geopolitical preference towards Russia, while in Belarus trust and consumption of Russian media had no detectable effect. Instead, trust in and consumption of digital media had an effect, where digital media predicted geopolitical preferences towards the European Union. This inconsistency of media influence is somewhat surprising, as Russian state-owned media have attempted to leverage Soviet nostalgia in the FSRs (Gaufman, 2015; Kozachenko, 2019; Kuzio, 2016). A study of social media during and after civil unrest in Ukraine 2013–14 (Euromaidan), for example, concluded that “re-constructed Soviet memory was actively used in order to undermine national identification with Ukraine.” (Kozachenko, 2019).

Cultivation and selective exposure co-mingle in our findings, in that, for example, differences in media influence likely also reflect differences in media usage between the FSRs. In 2022, social media were used by 84.3% of the population of Georgia, 64.6% of Ukraine, and 46.1% of Belarus, according to Kepios (Kemp, 2022). Between 2021 and 2022, the reported increase in social media users in each FSR was substantial (Kemp, 2022): +8.9% in Ukraine, +11.5% in Belarus, and +8.1% in Georgia (these figures predate the war in Ukraine). In terms of traditional media, pro-Russian populations receive more pro-Russian news from Russia, rather than domestic sources: Belarus is closely aligned with Russia politically, whereas Georgia and Ukraine are more pro-Western, outside the pro-Russian separatist regions of Ukraine. Further research is needed to delve into the factors that might be motivating the selection of certain media sources. Coming from the perspective of Selective Exposure Theory, in addition to examining these factors, the socio-political and cultural context in which media consumption takes place should also be examined.

Within the populations of Belarus and Ukraine, we found the younger cohorts were both more secular and more pro-E.U. This would appear to derive from the different experiences and cultural memories of different age cohorts. As Kozachenko (2019) describes:

First, most of the people in these countries were exposed to the Soviet-era myths of World War II ... Second, nearly every family has a member who fought during the war, either surviving it or not, with family stories of these people passed to a younger generation ... In addition to this, a large proportion of people have actual experience of living in the USSR with many possessing a positive memory of it.

Given a continuity of historical narratives relayed to younger generations, the differences in age cohorts ought to reflect something else. This seems likely to be differences in economic and political conditions of childhood development between age cohorts, as there have been substantial changes among the FSRs in the last 50 years.

As it is a far-away event, it is not surprising that the FSR respondents did not exhibit deeply held opinions about the 2021 U.S. Capitol riot. Amid the diverse scope of a person’s real-world interactions and communications (Boulianne et al., 2020; Lee and Yin, 2021), digital media are unlikely to substantially influence opinion around a subject that is not important to them. This suggests that social media provide a lens for observing homophily stemming from pre-existing cultural differences within a population.

The palimpsest of patterns also reflects the different trends of national history versus generational change within each country (Aksoy et al., 2020; Inglehart and Welzel, 2005; Ruck et al., 2018, 2020a). It appears that younger cohorts reflect different, post-Soviet, economic and political conditions since 1991. Belarus has had one president since 1994, who has been pro-Russian politically, whereas Ukraine and Georgia have had freer elections and more democracy and individual freedoms. Overall, the results suggest that “long-wave” cultural values move more slowly than, and relatively independently of, “short-wave" news events. Making this distinction could be important to sound policy addressing the problems of misinformation and disinformation across different cultures and generations.

We infer that the strong effect of nationality stems from historical differences in cultural development (Ruck et al., 2020b). Across the three FSRs, the more religious populations are also more pro-E.U. This might seem surprising, as World Values Survey data show that EU countries are generally more secular than Russia (Ruck et al., 2020a). Yet, despite their former incorporation into the Soviet Union, these different FSR populations likely maintain differences in deep/stable cultural values including religion, language, and ethnicity, which are conservative and do not readily diffuse between groups (Spolaore and Wacziarg, 2009). In Belarus, for example, the Belarusian language has socio-political connotations versus Russian (Hentschel and Zeller, 2014), and has become in some quarters a signal of solidarity. Under this hypothesis, the nexus of Communist beliefs would have spread more readily from Russia to culturally similar countries and slower to the culturally more distant countries, where both anti-Russian attitudes and religiousness persist.

In terms of maintaining certain views with disinformation, contemporary events can often be skewed to fit with prevailing political opinions and gradually transformed through time. During and after the Ukraine crisis of 2014–2015, for example, Soviet-era symbols and narratives were shared on the Russian social media service VKontakte in ways that promoted neo-Soviet myths and nostalgia about World War II (Kozachenko, 2019). After a spontaneous, organic response to events on social media, different actors vie to control the narrative. After mass protests in Russia in 2011–2012 regarding legislative elections, for another example, pro-government Twitter users were able to shift the political discourse and marginalize opposing voices (Spaiser et al., 2017). It may also be the case that the social engineering policies of post-soviet leaders in Belarus, Georgia, and Ukraine—such as pro-Russian education and media initiatives in the 1990s (Manaev, 2011) and opposing initiatives in Belarus and Georgia (DeWaal, 2011; Ukraine Government News, 2021)—have had an impact on generational differences. It is not possible to parse these impacts out with the limited questions in this survey. Before social media existed, psychological experiments on Russian participants showed that their memories of the 1999 attacks on Moscow apartment buildings could be altered by a suggestion that they had seen a wounded animal in the attacks and had mentioned it in their original memory reports, even elaborating the memory with imagined detail (Nourkova et al., 2004). In contrast, none of the Russian participants recalling the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center were convinced by that suggestion (Nourkova et al., 2004).

Our results are a reminder to us that even in the social media age, generational time, and geographical distance still shape the collective memory of events. When interacting with cultures, particular historical events can acquire mythical status in cultural memory (Benkler et al., 2018; Bentzen, 2018; Nunn, 2009). Although the personal impact of public news usually declines with time (Bentley et al., 2014; Moore et al., 2019), cultural memory is inter-generational. This deep cultural ancestry (Mace and Pagel, 1994; Matthews et al., 2016; Ruck et al., 2020b; Sookias et al., 2018), generally much older than contemporary geopolitical events, underlies social norms, institutions, and religions dictating attitudes towards national identity, allies and adversaries, property rights, public institutions, and government (Acemoglu and Robinson, 2012; Grier, 1997; Inglehart and Welzel, 2010; McCleary, 2008; Pejovich, 1999).

Conclusions

In these FSRs, we have observed a clear generational effect on pro-EU vs. Russian attitudes, as younger participants tended to be more pro-EU and rely more on digital media. The ever-difficult question is, where lies the causation? Are digital media causing people to be pro-EU, or is it growing up in a post-Soviet world, neither or both? We propose that the main driver of the effects we observed lies in generational differences and that digital media are shaped by the participation of those generations.

While one might concoct an intricate argument that media are the primary cause, we believe the most parsimonious explanation for all our results is homophily, based on year and nationality of birth. The reasoning is that geopolitical attitudes, but not media choice, pattern strongly with a year of birth and nationality. Media choice had predictive power, but inconsistently so. Although higher levels of education predict a more pro-EU attitude, the effect of education was not strong in our multivariate regressions (see Supplementary Materials). Furthermore, education level does not pattern with domestic versus Russian media choice, suggesting education level is not causal of political orientation. Though we see a stronger generational effect for the consumption of digital media, the weakness of the media effect means age is still operative through its influence on cultural values.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the lead author, BDH. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could possibly compromise the privacy of research participants.

References

Acemoglu D, Robinson J (2012) Why nations fail: the origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. Crown, New York

Acemoglu D, Johnson S, Robinson JA (2001) The colonial origins of comparative development: an empirical investigation. Am Econ Rev 91:1369–1401

Acerbi A (2019) Cognitive attraction and online misinformation. Palgrave Commun 5: article 15

Agarwal N, Al-khateeb S, Galeano R, Goolsby R (2017) Examining the use of Botnets and their evolution in propaganda dissemination. Defense Strateg Commun 2:87–112

Aksoy CG, Ganslmeier M, Poutvaara P (2020) Public attention and policy responses to COVID-19 pandemic. SSRN 3638340

Allcott H, Braghieri L, Eichmeyer S, Gentzkow M (2020) The welfare effects of social media. Am Econ Rev 110(3):629–676

Algan Y, Cahuc P (2010) Inherited trust and growth. Am Econ Rev 100(5):2060–2092

Alwin DF, Krosnick JA (1991) Aging, cohorts, and the stability of sociopolitical orientations over the life span. Am J Sociol 97(1):169–195

Anderson RO’G (1991) Imagined communities: reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. Verso, London

Aral S, Muchnik L, Sundararajan A (2009) Distinguishing influence-based contagion from homophily-driven diffusion in dynamic networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:21544–21549

Asimovic N, Nagler J, Bonneau R, Tucker JA (2021) Testing the effects of Facebook usage in an ethnically polarized setting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 118(25):e2022819118

Becker SO, Boeckh K, Hainz C, Woessmann L (2016) The empire is dead, long live the empire! Long-run persistence of trust and corruption in the bureaucracy. Econ J 126:40–74

Benkler Y, Faris R, Roberts H (2018) Network propaganda: manipulation, disinformation, and radicalization in American Politics. Oxford University Press

Bentley RA, Acerbi A, Ormerod P, Lampos V (2014) Books average previous decade of economic misery. PLoS ONE 9(1):e83147

Bentzen JS (2018) Acts of God? Religiosity and natural disasters across subnational world districts. Econ J 129:2295–2321

Bianchi EC (2014) Entering adulthood in a recession tempers later narcissism. Psychol Sci 25:1429–1437

Bond RM, Fariss CJ, Jones JJ, Kramer AD, Marlow C, Settle JE, Fowler JH (2012) A 61-million-person experiment in social influence and political mobilization. Nature 489:295–298

Botes MWM (2022) Brain–computer interfaces and human rights: brave new rights for a brave new world. In: Isbell C, Lazar S, Oh A, Xiang A (eds) 2022 ACM conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp. 1154–1161

Boulianne S, Koc-Michalska K, Bimber B (2020) Right-wing populism, social media and echo chambers in Western democracies. New Media Soc 22(4):683–699

Broniatowski DA, Jamison AM, Qi S, AlKulaib L, Chen T, Benton A, Quinn SC, Dredze M (2018) Weaponized health communication: Twitter Bots and Russian trolls amplify the vaccine debate. Am J Public Health 108(10):1378–1384

Bruce S (2011) Secularization: in defence of an unfashionable theory. Oxford University Press

Cheung BY, Chudek M, Heine SJ (2011) Evidence for a sensitive period for acculturation. Psychol Sci 22(2):147–152

Christakis NA, Fowler JH (2013) Social contagion theory: examining dynamic social networks and human behavior. Stat Med 32(4):556–577

Chudek M, Henrich J (2011) Culture–gene coevolution, norm-psychology and the emergence of human prosociality. Trends Cogn Sci 15(5):218–226

Cronk L (1999) That complex whole: culture and the evolution of human behavior. Routledge, New York

Darczewska J (2014) The anatomy of Russia information warfare. The Crimea operation, a case study. Point of View 42. Centre for Eastern Studies: Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia

Daw N, O’Doherty J, Dayan P, Seymour B, Dolan RJ (2006) Cortical substrates for exploratory decisions in humans. Nature 441:876–879

De Waal T (2011) Georgia’s choices: charting a future in uncertain times. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Druckman JN, Klar S, Krupnikov Y, Levendusky M, Ryan JB (2021) Affective polarization, local contexts and public opinion in America. Nat Hum Behav 5:28–38

Durkheim É [1915] (1965) The elementary forms of the religious life [trans: Swain JW]. Free Press, New York

EIPT, Election Integrity Partnership Team (2020) Repeat offenders: voting misinformation on Twitter in the 2020 United States election. https://www.eipartnership.net/rapid-response/repeat-offenders

EVS (2011) European Values Study Longitudinal Data File 1981−2008 (EVS 1981−2008). GESIS Data Archive, Cologne, ZA4804. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13486

Facchetti G, Iacono G, Altafini C (2011) Computing global structural balance in large-scale signed social networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108(52):20953–20958

Ferrara E, Varol O, Davis C, Menczer F, Flammini A (2016) The rise of social bots. Commun ACM 59(7):96–104

Festinger L (1957) A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press

Foa RS, Mounk Y, Inglehart RF (2016) The danger of deconsolidation. J Democracy 27(3):5–17

Freedom House (2021) Freedom in the World 2021. https://freedomhouse.org

Freelon D, Lokot T (2020) Russian Twitter disinformation campaigns reach across the American political spectrum. HKS Misinf Rev 1(1): https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-003

Gallotti G, Valle F, Castaldo N, Sacco P, De Domenico M (2020) Assessing the risks of ‘infodemics’ in response to COVID-19 epidemics. Nat Hum Behav 4:1285–1293

Garcia-Herranz M, Moro E, Cebrian M, Christakis NA, Fowler JH (2014) Using friends as sensors to detect global-scale contagious outbreaks. PLoS ONE 9:e92413

Gaufman E (2015) World War II 2.0: digital memory of fascism in Russia in the aftermath of Euromaidan in Ukraine. J Reg Secur 1:17–35

Gelfand MJ, Raver JL, Nishii L, Leslie LM (2011) Differences between tight and loose cultures: a 33-nation study. Science 332(6033):1100–1104

Gelfand MJ, Jackson JC, Pan X, Nau DS, Pieper D, Denison E, Dagher MM, van Lange PAM, Chiu C, Wang M (2021) The relationship between cultural tightness–looseness and COVID-19 cases and deaths: a global analysis. Lancet Planet Health 5:e135–e144

Gerber TP, Zavisca J (2016) Does Russian propaganda work? Wash Q 39(2):79–98

Gerbner G (1973) Cultural indicators: the third voice. In Gerbner G, Gross L, Melody WH (eds) Communications technology and social policy. Wiley, New York, pp. 555–573

Gorodnichenko Y, Roland G (2017) Culture, institutions and the wealth of nations. Rev Econ Stat 99:402–416

Grier R (1997) The effects of religion on economic development: a cross national study of 63 former colonies. Kyklos 50:47–62

Grinberg N, Joseph K, Friedland L, Swire-Thompson B, Lazer D (2019) Fake news on Twitter during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Science 363:374–378

Groh M, Epstein Z, Firestone C, Picard R (2022) Deepfake detection by human crowds, machines, and machine-informed crowds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 119(1):e2110013119

Grossmann I, Varnum MEW (2015) Social structure, infectious diseases, disasters, secularism, and cultural change in America. Psychol Sci 26(3):311–324

Grusec JE, Kuczynski L (1997) Parenting and children’s internalization of values: a handbook of contemporary theory. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ

Henrich J, Bauer M, Cassar A, Chytilová J, Purzycki BG (2019) War increases religiosity. Nat Hum Behav 3:129–135

Henrich J (2015) The secret of our success: how culture is driving human evolution, domesticating our species, and making us smarter. Princeton University Press

Hentschel G, Zeller JP (2014) Belarusians’ pronunciation: Belarusian or Russian? Evidence from Belarusian–Russian mixed speech. Russ Linguist 38:229–255

Herzer D, Strulik H (2017) Religiosity and income: a panel cointegration and causality analysis. Appl Econ 49(30):2922–2938

Horne BD, Nevo D, Adalı S, Manikonda L, Arrington C (2020) Tailoring heuristics and timing AI interventions for supporting news veracity assessments. Comput Human Behav Rep 2:100043

Horne BD, Nørregaard J, Adalı S (2019) Different spirals of sameness: A study of content sharing in mainstream and alternative media. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 13:257–266

Howard PN, Parks MR (2012) Social media and political change: capacity, constraint, and consequence. J Commun 62(2):359–362

Inglehart R (2008) Changing values among Western publics from 1970 to 2006. West Eur Polit 31(1–2):130–146

Inglehart R, Baker WE (2000) Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. Am Sociol Rev 65(1):19–51

Inglehart R, Welzel C (2005) Modernization, cultural change, and democracy. Cambridge University Press

Inglehart R, Welzel C (2010) Changing mass priorities: the link between modernization and democracy. Perspect Polit 8:551–567

Iyer L (2010) Direct versus indirect colonial rule in India: long-term consequences. Rev Econ Stat 92:693–713

Jakesch M, Garimella K, Eckles D, Naaman M (2021) Trend alert: a cross-platform organization manipulated Twitter trends in the Indian general election. Proc ACM Human–Computer Interact 5(CSCW2):1–19

Johnson NF, Zheng M, Vorobyeva Y, Gabriel A, Qi H, Velasquez N, Manrique P, Johnson D, Restrepo E, Song C, Wuchty S (2016) New online ecology of adversarial aggregates: ISIS and beyond. Science 352:1459–1463

Johnson NF, Leahy R, Johnson RN, Velasquez N, Zheng M, Manrique P, Devkota P, Wuchty S (2019) Hidden resilience and adaptive dynamics of the global online hate ecology. Nature 573:261–265

Johnson NF, Velásquez N, Restrepo NJ (2020) The online competition between pro- and anti-vaccination views. Nature 582:230–233

Kemp S (2022) Digital 2022: global overview report. https://datareportal.com

Kendal RL, Boogert NJ, Rendell L, Laland KN, Webster M, Jones PL (2018) Social learning strategies: Bridge-building between fields. Trends Cog Sci 22:651–665

Knobloch-Westerwick S (2015) Choice and preference in media use: advances in selective exposure theory and research. Routledge, New York

Kozachenko I (2019) Fighting for the Soviet Union 2.0: Digital nostalgia and national belonging in the context of the Ukrainian crisis. Communist Post-Communist Stud 52:1–10

Kumar S, Cheng J, Leskovec J, Subrahmanian VS (2017) An army of me: Sockpuppets in online discussion communities. In: International World Wide Web Conferences Steering Committee (ed) WWW '17: Proceedings of the 26th international conference on World Wide Web, pp. 857–866

Kuzio T (2016) Soviet and Russian anti-(Ukrainian) nationalism and re-stalinization. Communist Post-Communist Stud 49(1):87–99

Land KC, Yang Y (2013) Age-period-cohort analysis: new models, methods, and empirical applications. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL

Lazer D, Kennedy R, King G, Vespignani A (2014) The parable of Google Flu: traps in big data analysis. Science 343:1203–1205

Lee FL, Yin Z (2021) A network analytic approach to selective consumption of newspapers: the impact of politics, market, and technological platform. J Mass Commun Q 98(2):346–365

Lesthaeghe R (2014) The second demographic transition: a concise overview of its development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111(51):18112–18115

Loftus EF (2005) Planting misinformation in the human mind: a 30-year investigation of the malleability of memory. Learn Mem 12(4):361–366

Luther C, Prins BC, Manaev O, Rice NM, Taylor M, Allard S, Fitzgerald M, Horne BD, Bentley RA, Borycz J (2022) Traditional and Social media usage and pro-Russian versus anti-Russian attitudes in Belarus and Ukraine. Conference Presentation, 72nd Annual International Communication Association Conference, Paris, 27 May 2022

Mace R, Pagel M (1994) The comparative method in anthropology. Curr Anthropol 35:549–564

Manaev O (ed) (2011) Youth and civil society in Belarus: new generation. IISEPS

Matthews L, Passmore S, Richard PM, Gray RD, Atkinson QD (2016) Shared cultural history as a predictor of political and economic changes among nation states. PLoS ONE 11:e0152979

McCleary RM (2008) Religion and economic development. Policy Rev 148:45–57

Moore FC, Obradovich N, Lehner F, Baylis P (2019) Rapidly declining remarkability of temperature anomalies may obscure public perception of climate change. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116:4905–4910

Morgan M (2012) George Gerbner: a critical introduction to media and communication theory. Peter Lang, New York

Nevo D, Horne BD (2022) How topic novelty impacts the effectiveness of news veracity interventions. Commun ACM 65(2):68–75

Norris P, Inglehart R (2004) Sacred and secular: religion and politics worldwide. Cambridge University Press

Nourkova V, Bernstein D, Loftus E (2004) Altering traumatic memory. Cogn Emot 18(4):575–585

Nunn N (2009) The importance of history for economic development. Ann Rev Econ 1:65–92

Pariser E (2011) The filter bubble: What the internet is hiding from you. Penguin Press, New York

Pejovich S (1999) The effects of the interaction of formal and informal institutions on social stability and economic development. J Mark Moral 2:164–181

Petanjek Z, Judaš M, Šimić G, Rašin MR, Uylings HBM, Rakic P, Kostović I (2011) Extraordinary neoteny of synaptic spines in the human prefrontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108(32):13281–13286

Polman M (2021) Russian-language media: can Ukraine compete with the Kremlin? Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/russian-language-media-can-ukraine-compete-with-the-kremlin/

Pond P (2021) Digital media and the making of network temporality. Routledge, New York

Ritchie H, Roser M (2022) Age structure. https://ourworldindata.org/age-structure

Roman N, Wanta W, Buniak I (2017) Information wars: Eastern Ukraine military conflict coverage in the Russian, Ukrainian and U.S. newscasts. Int Commun Gaz 79(4):357–378

Ruck DJ, Bentley RA, Lawson DJ (2018) Religious change preceded economic change in the 20th century. Sci Adv 4(7):eaar8680

Ruck DJ, Rice NM, Borycz J, Bentley RA (2019) Internet Research Agency Twitter activity predicted 2016 U.S. election polls. First Monday, 1 July

Ruck DJ, Bentley RA, Lawson DJ (2020) Cultural prerequisites of socioeconomic development. R Soc Open Sci 7:7190725

Ruck DJ, Matthews LJ, Kyritsis T, Atkinson QD, Bentley RA (2020) The cultural foundations of modern democracies. Nat Hum Behav 4:265–269

Ryder NB (1965) The cohort as a concept in the study of social change. Am Sociol Rev 30(6):843–861

Sears DO, Funk CL (1999) Evidence of the long-term persistence of adults’ political predispositions. J Polit 61(1):1–28

Shah N (2017) Flock: combating astroturfing on livestreaming platforms. In: International World Wide Web Conferences Steering Committee (ed) WWW '17: Proceedings of the 26th international conference on World Wide Web, pp. 1083–1091

Shalizi CR, Thomas AC (2011) Homophily and contagion are generically confounded in observational social network studies. Sociol Methods Res 40(2):211–239

Sookias RB, Passmore S, Atkinson QD (2018) Deep cultural ancestry and human development indicators across nation states. R Soc Open Sci 5(4):171411

Spaiser V, Chadefaux T, Donnay K, Russmann F, Helbing D (2017) Communication power struggles on social media: a case study of the 2011–12 Russian protests. J Inf Technol Politics 14(2):132–153

Spolaore E, Wacziarg R (2009) The diffusion of development. Q J Econ 124(2):469–529

Starbird K, Arif A, Wilson T, Van Koevering K, Yefimova K, Scarnecchia D (2018) Ecosystem or echo-system? Exploring content sharing across alternative media domains. In: Budak C, Cha M, Quercia D (eds) Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM), pp. 365–374

Stolzenberg RM, Blair-Loy M, Waite LJ (1995) Religious participation in early adulthood: Age and family life cycle effects on church membership. Am Sociol Rev 60(1):84–103

Szostek J (2015) Russian influence on news media in Belarus. Communist Post-Communist Stud 48(2-3):123–135

Ukraine Government News (2021) Volodymyr Zelenskyy signed the law on the main principles of youth policy. https://www.president.gov.ua/ru/news/volodimir-zelenskij-pidpisav-zakon-pro-osnovni-zasadi-molodi-68517

Varnum MEW, Grossmann I (2017) Cultural change: the how and the why. Perspect Psychol Sci 12(6):956–972

Vartanova E, Gladkova A (2019) New forms of the digital divide. In: Trappel J (ed) Digital media inequalities: policies against divides, distrust and discrimination. Nordicom, Gothenburg, pp. 193–213

Vosoughi S, Roy D, Aral S (2018) The spread of true and false news online. Science 359:1146–1151

Wagner-Pacifici R (2010) Theorizing the restlessness of events. Am J Sociol 115(5):1351–1386

Wagner-Pacifici R (2017) What is an event? University of Chicago Press

Waller I, Anderson A (2021) Quantifying social organization and political polarization in online platforms. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04167-x

Weimann G (2015) Terrorism in cyberspace: the next generation. Columbia University Press

WVS—World Value Survey (2017) What we do. http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSContents.jsp

Zannettou S, Sirivianos M, Blackburn J, Kourtellis N (2019) The web of false information: rumors, fake news, hoaxes, clickbait, and various other shenanigans. J Data Inf Qual 11(3):1–37

Acknowledgements

This research was supported through the Minerva Research Initiative in partnership with the Office of Naval Research. It is part of a larger University of Tennessee interdisciplinary project titled Monitoring the Content and Measuring the Effectiveness of Russian Disinformation and Propaganda Campaigns in Selected Former Soviet Union States (Grant: N000142012618).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations applicable when human participants are involved (Declaration of Helsinki). The research was approved by the University of Tennessee-Knoxville Human Research Protections Program (HRPP), which determined that the application was eligible for exempt status under 45 CFR 46.104.d, Category 2 (https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/revised-common-rule-regulatory-text/index.html#46.101). Our application was determined to comply with proper consideration for the rights and welfare of human subjects and the regulatory requirements for the protection of human subjects.

Informed consent

Per the approved IRB application, a brief informed consent statement was presented orally to participants (for surveys). Participants were not provided with written documentation of consent. Their willingness to respond to the survey or interview constituted documentation of their consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Horne, B.D., Rice, N.M., Luther, C.A. et al. Generational effects of culture and digital media in former Soviet Republics. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 172 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01670-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01670-6

This article is cited by

-

RETRACTED ARTICLE: Common Language Development in Multilingual Contexts: A Study of Russian Language Policy in the Early Years of the Soviet Union

Journal of Psycholinguistic Research (2024)

-

Perceived social influence on vaccination decisions: a COVID-19 case study

SN Social Sciences (2024)