Abstract

Collaborative governance has received attention among scholars and practitioners for resolving governance issues across the globe. The government of Pakistan emphasizes local collaborative governance practices for resolving complex local problems through efficient public service delivery. This research is planned to examine the impact of local collaborative governance on public service delivery, institutional capacity building and how local collaborative governance influences public service delivery through the mediating mechanism of institutional capacity building. Using collaborative governance theory and collecting data from multisector organizations in the context of Pakistan, the results of this study revealed that local collaborative governance is significantly related to the dimensions of public service delivery and institutional capacity building. This research findings revealed that local collaborative governance engenders public service delivery through the dimensions of institutional capacity building including service capacity, evaluative capacity, and M&O capacity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

New successors of traditional public administration and new public management emerged in developed nations, including China, America, Britain, and Canada. Collaborative governance had been explored over the decades to shift traditional governance approaches. It envisioned the collaboration of multiple stakeholders in one setting to deliver better public services to the citizens (Biddle and Koontz, 2014; Frankowski, 2019; Tomas M Koontz and Thomas, 2021). Collaborative governance is extensively defined as the functions and structures of policy decision-making and administration that involve public beneficially across the limitations of public institutions (Gash, 2022). It involves government, public, private and civic levels to fulfill a public drive that could not otherwise be completed. A number of alternative models of governance have been proposed in various countries as good governance, multi-level governance, partnerships, policy networks, interactive governance and contemporary governance with four commonalities: process, partnerships, collective decision-making and new forms of engagement (Di Gregorio et al., 2019). Local collaborative governance is a significant topic in public administration as it aims to address governance failures, high costs, and politicization of regulation through developing contingency approaches to local governance (Berthod et al., 2023). Collaborative governance is applied in local projects in several countries and emerged as local collaborative governance (Cristofoli et al., 2022). So, Local collaborative governance is by no means a new way to view governance at district level. Local collaborative governance also envisioned clarity of objectives, planning, leadership, trust, commitment and mutual working relations. It is believed that local collaborative governance devolves monetary and non-monetary powers to local government and ensures the efficiency and quality of public service delivery to citizen demands (Bradley, Mahmoud, and Arlati, 2022).

Recently, many governments in developing countries also reformed their local government systems to local collaborative governance (Shah et al., 2022). It is observed that local governments in developing nations cannot efficiently provide public services due to a lack of capacity, credibility and disposition (Velez‐Ocampo and Gonzalez‐Perez, 2022). Researchers can evaluate and assess the local collaborative governance model proposed by Ansell and Gash, 2022 and ruminate critically on its accuracy, applicability and suitability for implementing policies and programs at the local level (M. S. Khan and Syrett, 2022). Researchers in local collaborative governance have long argued that further empirical studies are needed to explore the connections between collaborative governance and other factors influencing public service delivery, such as coproduction and public service value. However, empirical evidence between local collaborative governance, institutional capacity building and public service delivery is lacking in the existing literature

The collaborative governance theory posits that many stakeholders collaborate in joint forums alongside government institutions to ensure consensus-based decision-making processes. This idea posits that several sectors have the potential to engage in collaborative decision-making processes for the delivery of public services. It introduces the contingency approach to collaboration within the context of public administration and public policy. According to this theoretical perspective, it is contended that managers and administrators, via collaborative efforts, possess the ability to exert influence on the decision-making process, hence leading to the achievement of effective public service delivery. The collaborative governance theory allows multisector managers to behave like collective mindset to improve public service delivery (Bellé, 2014). In such situations where there are initial disparities in power and resources among stakeholders, resulting in limited meaningful participation of important stakeholders, the establishment of effective collaborative governance necessitates a dedicated approach that empowers and represents weaker or disadvantaged stakeholders. The involvement of multisector managers actions communicated with external stakeholders has the potential to foster their satisfaction with public service delivery (N. U. Khan et al., 2023).

It is crucial to comprehend incentive structures that drive participation in collaborative governance, as well as various elements that influence these incentives (Emerson and Nabatchi, 2015). The achievement of public service delivery objectives within the framework of collaborative governance might potentially be facilitated through the motivation of multisector managers to adhere to action plans, which can be accomplished through the delegation of incentives within the collaborative governance structure. The historical context of conflict among stakeholders can be followed by a significant level of interdependence among such stakeholders. Accordingly, the interdependence between sectors might serve as a motivating factor for multisector managers to exert effort for public service objectives (Vaccari et al., 2020).

The importance of leadership in the collaborative governance paradigm cannot be overlooked, as it plays a crucial role in ensuring effective collaboration among stakeholders. This assertion posits that the absence of effective leadership renders the execution of collaborative processes in multisector organizations unattainable. The Collaborative Governance Theory (CGT) posits that institutional architecture plays a crucial role in establishing fundamental protocols and ground rules which ensures the procedural legitimacy of collaborative processes. The establishment of this institutional framework is crucial for maintaining credibility among various sectors for achieving desired outcomes in terms of effective public service delivery.

In the past, researches were conducted on public-private partnership, so there is a wider scope of collaborative governance in developing countries (M. Khan, Khurram, and Zubair, 2020). This study will examine whether the implementation of local collaborative governance will improve the delivery of public services, thereby enhancing institutional capacity development at the district level in Pakistan. This research will concentrate on basic public service delivery such as energy, water and sanitation, roads, health, education, infrastructure and transportation. Preceding studies have scrutinized the association of collaborative governance with multiple outcomes at local levels, but the effect of local collaborative governance with public service delivery and institutional capacity building has not been explored in a multisector organizations managers context. The objective of this research is to evaluate the relationship between local collaborative governance and public services through institutional capacity building. It is presumed that the success of local collaborative governance is contingent on the institutional capacity of local authorities to which a substantial amount of power has been devolved.

Considering the increased emphasis on local collaborative governance and the public service delivery dimensions (responsiveness, tangibles and reliability) effect on local collaborative governance. Managers can ensure responsive, tangible and reliable public service delivery in the local collaborative governance. The service capacity, evaluative capacity and M&O dimensions of institutional capacity building may have an impact on the local collaborative governance.

This study utilizes CGT theory to inquire into the relationship between LCG and PSD, LCG and ICB, ICB and PSD for the first time. Moreover, the study also examines how ICB acts as a mediator between LCG and PSD. This research adds to the existing literature on LCG by considering PSD and ICB in the context of strengthening government institutions.

The specific research questions of the study are as follows:

-

Is there any relationship between local collaborative governance and public service delivery?

-

Is there any association between local collaborative governance and institutional capacity building?

-

How does institutional capacity building mediate between local collaborative governance and public service delivery?

Theoretical support and hypotheses development

Linking local collaborative governance and public service delivery

Several studies have utilized collaborative governance to examine the delivery of public services. It is anticipated that LCG will resolve complex public issues. Some researchers illustrated a mixed scanning approach of collaborative governance and innovation to evaluate the functions and structures of CG (van Gestel and Grotenbreg, 2021). In other nations, such as the United States and South Korea, a comparative analysis of collaborative governance and public services has also been conducted (Jung, Mazmanian, and Tang, 2009). Theoretically, CG is extensively used by natural geography, public reforms, public health, citizen involvement, land ecological protection and sports institutions. With the expansion of CG research, the specific options for the integration and development of collaborative governance at the local level will expand over time (Agger and Löfgren, 2008). It has been depicted as a means to promote cooperation to enhance public service delivery via collaborative governance, which entails multiple stakeholders cooperating under the authority of law (Fledderus, Brandsen, and Honingh, 2015). Evidence suggested that efficient capacity building can lead to better life chances, including reduced child mortality rates in health and educational services (Rajkumar and Swaroop, 2008). Collaboration reforms can improve public service delivery and service quality can improve through local governments in Pakistan (Mohmand and Cheema, 2007). Public institutions have become an obstacle to pro-public change and must be transformed from a rule-based to collaborative structure in tandem with broader political and economic change. Case studies on public service delivery illuminated the informal social norms that regulate the provision of fundamental social services, such as clientelism and personal relationships (Arshad et al., 2020). Local collaborative governance entails the formation of specific institutions or entities to provide services to a local geographical area. The success of local collaborative governance is contingent upon the character of local governance, which includes responsiveness, accountability, and professionalism. Delegating decision-making authority and responsibilities to local administrations can enhance the delivery of public services. The local government devised an accountability system for effective collaborative governance to ensure transparency. However, the complex obstacles posed by the delivery of public services in developing nations are intimidating but still there are challenges on the premises of local collaborative governance (Emerson, 2018).

It is posited that the implementation of local collaborative governance has the potential to foster collaboration among multisector managers and administrators, thereby enabling them to exert influence on public sector decision-making. Several hypotheses can be derived from the preceding discussion.

H1: There is a significant relationship between local collaborative Governance and public service responsiveness.

H2: There is an association between local collaborative Governance and tangible public service delivery.

H3: There is a connection between local collaborative Governance and reliable public service delivery.

Linking local collaborative governance and institutional capacity building

The term “government capacity” is closely related to the idea of state capacity, which has long been discussed in political economics. State capacity is defined as the ability of a state to perform appropriate tasks/functions efficiently, effectively, and sustainably. There are four types of state capacity: institutional capacity, technical capacity, administrative capacity, and political capacity (Grindle and Hilderbrand, 1995). Institutional capacity is the state’s ability to establish and enforce a broad set of rules governing economic and political interactions to deliver public service (Wallis and Dollery, 2001). Institutional capacity is the most popular term and is often used as a proxy for the country’s capacity (Acemoglu and Johnson, 2005). The concept of “governance capacity”, which is widely popular in public administration, also relates closely to institutional capacity. This concept is based on the perspective of governance, which is defined as steering actors in localities to cover public service where local government plays a key role (Peters and Pierre, 1998). Hence, institutional capacity incorporates both local government capacity and the capacity of surrounding conditions. It consists of four components: mobilization capacity, decision-making capacity, implementation capacity, and local capacity (Tando, Sudarmo, and Haryanti, 2019). Mobilization refers to the local government’s capacity to mobilize resources (financial and materials) for services and functions. It includes generating adequate resources and channeling them into planned output. Decision-making capacity is the ability of the local government to allocate resources; it includes the capability of planning and communications. Implementation capacity indicates the managerial capacity and quality of human resources. Managerial capacity covers both administrative skills and best practices of management. The quality of human resources encompasses the quality of personnel and human resource management. The last, local capacity, is related to local resources that correspond to socioeconomic development.

Previous empirical study has demonstrated that the implementation of collaborative governance by managers and administrators can effectively enhance the process of institutional capacity building. Drawing upon the framework of collaborative governance theory, it is posited that the establishment of local collaborative governance structures can foster an atmosphere conducive to the engagement of multisector administrators/ managers, hence enhancing the process of institutional capacity development. Based on the preceding discourse, we formulate the subsequent hypothesis.

H4: local collaborative governance is significantly related to service capacity building.

H5: local collaborative governance is significantly linked with Evaluative capacity building.

H6: local collaborative governance is significantly associated with Monitoring and operations capacity.

Mediating role of institutional capacity building

Institutional capacity refers to the collective competencies of public officials in several aspects, such as program formulation, resource acquisition, management, utilization, as well as activity evaluation and the application of lessons learnt for future developmental endeavors (Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett, 2015). The variation in this phenomenon is contingent upon the amount and quality of services delivered by the bureaucrats (Billing, 2019). Therefore, despite their intangible nature, these resources refer to the technical and soft skills that public officials possess, which ultimately contribute to institutional capacity. The acceptance of the multi-dimensional nature of this occurrence can likely be attributed to the expectation that institutions should exhibit a multitude of capacities (Cingolani and Fazekas, 2017). Furthermore, it is argued that a comprehensive understanding of institutional capability can be achieved by examining its primary components (Haque and Doberstein, 2021). The aspects of institutional capability utilized in this study closely adhered to the framework proposed by (Grimm, Spring, and Dietz, 2007) and their collaborators. Three dimensions of institutional capability are specifically adapted including service, evaluative, and M&O.

The collaborative governance idea posits that the process of service capacity building has the potential to enhance delivery of public services by public institutions. The evaluative dimension of institutional capacity building pertains to the assessment of existing capability and the identification of areas for future improvement. The M&O pillar of institutional capacity building emphasizes the monitoring and operational capabilities of institutions in overseeing the delivery of public services.

The existing empirical research has noted institutional capacity building enhances employee’s performance in public agencies (Annan-Prah and Andoh, 2023). Using CGT theory, we assume that the dimensions of institutional capacity building create an environment where multisector managers can collaborate for effective public service delivery. Based on this discussion, we draw the following hypothesis (See Fig. 1)

H7: Service capacity building mediates the association between local collaborative governance and public service responsiveness.

H8: Evaluative capacity building mediates the association between local collaborative governance and tangible public service delivery.

H9: Monitoring and operations capacity building mediates the association between local collaborative governance and reliable public service delivery.

Materials and methods

Sample and procedure

For measuring the association of hypothesis constructs, data from 223 distinct multi-sector organizations employees (public sector, private organizations, NG0s, and corporations) in various districts of southern Pakistan were collected randomly. This study solicited responses from full-time MSO officers/managers/staff via survey questionnaires. Before survey to be distribution, consent is obtained from the relevant MSO to explicate the scope of this study. 844 questionnaires were delivered to the 223 MSOs (physically and via courier), and we received 683 questionnaires returned. 457 of the received questionnaires were finally completed, while 226 contained missing data and were therefore incomplete. The demographic information included (a) gender, (b) age, (c) education, (d) organizational sector, and (e) experience. In addition, the questionnaire is treated in a completely confidential manner so that the respondent’s name and signature are concealed (Ullman and Bentler, 2012).

Measurements

Five-point Likert scale for measuring response rate (5 = strongly agree to 1 = strongly disagree) is used in this research. Local collaborative governance is quantified by 9-items adapted starting from “My organization trusts on a formal agreement that spells out relationships between partner organizations to my organization brainstorms with partner organizations to develop solutions to mission-related problems facing the local collaboration” (Thomson et al. (2009)). Institutional capacity building is measured through 22-item capacity assessment tool dimensions of service capacity, evaluative capacity and M&O capacity starting from “My organization does not have a clear understanding of how resources and strategies will result in my intended outcomes to my organization does not have sufficient expertise to effectively and efficiently run and manage technology systems(Grimm, Spring, and Dietz, 2007). “The 08-items SERVQUAL scale is adopted to measure the public service delivery with dimensions of responsiveness, tangibles, and reliability started from my organization have up-to-date equipment to employees of my organization are always willing to help me” (Zeithaml et al., 1990) and validly used in the public health delivery in Pakistan (Irfan et al., 2012).

Results

It seems appropriate to conduct statistical analysis using the PLS-SEM approach and Smart-PLS 4–0 (Hair Jr et al., 2017). A method of multivariate data analysis is used to investigate these intricate relationships. Therefore, the structural equation model (PLS-SEM) is utilized to achieve robust results. Path model through SMART PLS-4 illustrates and verifies the relationship among construct variables and indicators. In light of prevalent justifications, PLS-SEM is particularly suited for exploratory research, as theory does not adequately explicate the model. Above-mentioned statistical software is the only reliable way to predict complex models with multiple construct variables efficiently. It is more adaptable to practical assumptions regarding the distribution of data to a limited sample size if there is an identification issue. In addition, it is highly statistically stable with the path modeling technique and a small sample size under distributional assumptions (Hair Jr et al., 2017) (Table 1).

Factor analyses construct reliabilities and validities

CFA is a statistical technique that examines the relationship among observed variables and latent factors (Gallagher, Timothy (2013)). CFA is a form of structural equation modeling (SEM) that assesses whether the observed correlations among a set of indicators align with a proposed underlying factor structure and determines the fitness of observed data to the hypothesized model. Overall, CFA is a crucial tool for evaluating the construct validity of measures, and it assists researchers in refining theoretical models (Morin, Myers, and Lee, 2020). Each loading value greater than 0.60 is accurately represented in the variables that contain the loadings.

Cronbach’s alpha can be utilized to evaluate the questionnaire’s reliability. According to conventional standards, the range for Cronbach’s alpha is between 0 and 1 (Schweizer, 2011). Cronbach’s alpha values for the present study indicate that all item values exceed 0.7, indicating that the items are consistent with the underlying construct (Nunnally, 1978). Cronbach alpha values for local collaborative governance are 0.821, institutional capacity is 0.876, and public service delivery is 0.793, all of which are greater than 0.70. Thus, the questionnaire’s dependability is validated. The current study reveals CR values greater than 0.7 for all variables, including local collaborative governance (0.934), institutional capacity building (0.918), and public service delivery (0.912). These values are suitable for the analysis. A widely used threshold for this approach is Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) to be less than 10 (Hair Jr et al., 2017). The value of AVE of local collaborative governance is 0.614, which is higher than the benchmark of 0.50 as well as institutional capacity building and public service delivery with values of 0.504 and 0.509, respectively. Thus, the convergent validity of the questionnaire is confirmed (Table 2).

Cross-loadings are analyzed to ascertain discriminant validity, and it has been determined that they meet the minimum standards, as the values of each cross correlation are greater than 0.70 (Henseler, Ringle, and Sarstedt, 2015). In other words, the results of the Fornell-Larcker criterion demonstrate the discriminant validity of the measures in question (Table 3). The Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) is used to validate the Fornell-Larcker criterion’s results. The HTMT ratio should be less than 0.9, according to a generally accepted benchmark. The findings of this study indicate that all constructs satisfy this criterion, providing additional evidence of their discriminant validity (Table 4). The detection of common method biases in (PLS-SEM) can be achieved through the full collinearity approach, as stated by (Hair Jr et al., 2017)

Structural model

Table 5 presents the values of R2, which are statistical metrics used to assess the explanatory power of the regression model (Ramayah et al., 2017). The value of R2 indicates the proportion of the variation in the Institutional Capacity Building = 0.663 and Public Service Delivery = 0.658. In continuum, it can be observed that the independent variable in the model bring 66% variation in the dependent variable.

The results of the path analysis indicated that paths in this conceptual model were found to be significantly supported. The direct path analysis indicated that the impact of local collaborative governance on institutional capacity building is positive and significant (β = 0.812, p < 0.01). Similarly, the linkage of institutional capacity building and public service delivery is positive and significant (β = 0.427, p < 0.01). Further, the relationship between local collaborative governance and individual latent variables of institutional capacity building including responsiveness (β = 0.775, p < 0.01) tangibles (β = 0.445, p < 0.01) and Reliability (β = 0.728, p < 0.01) are also found significant. Whilst, the association among local collaborative governance and individual latent variables of institutional capacity building including Service capacity (β = 0.795, p < 0.01), Evaluative capacity (β = 0.762, p < 0.01) and M&O capacity (β = 0.781, p < 0.01) are also found to be positive and significant.

Mediation results

The next step is to test mediation analysis of institutional capacity building between relationship of local collaborative governance and PSD (Table 6). The statistical interpretation posits that both direct and indirect effect is positive and significant (Hayes, Montoya, and Rockwood, 2017). The coefficient of indirect path is (b = 0.344 p < 0.01) whereas the coefficient of direct path is (b = 0.427, p < 0.01). These findings confirm that there is partial mediation.

According to Table 7, the values of fit index required are within the desired range. It is generally accepted that the acceptable range of SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual) should be less than 0.10 (Hu and Bentler, 1999). In this particular model, the SRMR value is calculated to be less than 0.10, which is within the acceptable range and, therefore, meets the criteria for a well-fitting model. This indicated that the model is likely to be a good representation of the data and can be used to make meaningful predictions and inferences. The Normalized Fit Index (NFI) is a measure of the relative improvement of fitness in the proposed model compared to a null model (Widaman and Thompson, 2003). It is calculated as 1 subtracted from χ 2 statistic of the proposed model divided by the χ 2 statistic of the null model. The NFI values range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating a better fit (Hooper, Coughlan, and Mullen, 2008). The results of our model indicated that the NFI value is reasonable and above 0.6, which suggested that the model fit is good. This implies that the proposed model provided a significantly better fit than the null model and can be used to make accurate predictions and inferences based on the data.

Discussion

This research planned to examine the influence of local collaborative governance on public service delivery, institutional capacity building and influence of institutional capacity building on public service delivery. This study also intended to observe the influence of local collaborative governance on public service delivery through the intervening mechanism of institutional capacity building. Findings show that local collaborative governance is positively related to public service delivery. It illustrated that increased perceptions of characteristics of local collaborative governance increased the perceptions of public service delivery.

Previous studies had found that collaborative governance can enhance public service responsiveness in healthcare and transportation in developed and developing countries (Frankowski, 2019; T M Koontz et al., 2004; Tomas M Koontz et al., 2010; Lai et al., 2022; Xu, Liu, and Chen, 2017). Therefore, a comprehensive approach that espoused multiple factors is necessary to ensure effective local collaboration to improve public service responsiveness in multisector in Pakistan. In this way, this RQ1 exclusively explained local collaborative governance is positively linked with public service responsiveness which validated research hypothesis H1. So, H1 is accepted.

Previous Studies had confirmed that collaborative governance can improve tangible public service delivery in the transportation sector, environmental management, public safety services and emergency medical services (Kamara, 2017; Klijn, Edelenbos, and Steijn, 2010; Labin et al., 2012; Morse, 2011; Sørensen and Torfing, 2011). Similarly, this relationship showed that local collaborative governance is also related to tangible public services in Pakistan. In this way, this RQ2 exclusively explained that local collaborative governance is positively linked with tangible public service delivery which validated research hypothesis H2. So, H2 is accepted.

Previous researches conducted in the U.S and Indonesia supported the benefits of collaborative governance in improving public service delivery (Bradford, 2016; Emerson, Nabatchi, and Balogh, 2012; Ullah and Kim, 2020). In Pakistan, LGCDP has sought to establish partnerships among local governments, community members and civil society organizations to improve reliable public service delivery. In this way, RQ3 exclusively explained that local collaborative governance is positively linked with reliability of public service delivery which validated research hypothesis H3. So, H3 is accepted.

Previous literature also supported that collaboration among different stakeholders can enhance service capacity by promoting innovation, learning and coordination in U.S, Africa, and Korea (Ary et al., 2010; Jung, Mazmanian, and Tang, 2009; Kamara, 2017; Morse, 2011). Through SEM results, it is indicated that there is a significant relationship between local collaborative governance and service capacity in Pakistan. This validated our research hypothesis that there is significant linkage which validated our research hypothesis H4. So, H4 is accepted.

The authors found that collaborative processes can enhance evaluative capacity in different countries i.e., U.K., Australia, and U.S (Lewis et al., 2016; Nabatchi and Leighninger, 2015; Roberson and Choi, 2009). In this way, this RQ5 exclusively explained that there is a linkage between local collaborative governance and evaluative capacity building in Pakistan. Through SEM results, it is indicated that there is a significant relationship between local collaborative governance and evaluative capacity in Pakistan which validated research hypothesis H2b. So, H2b is accepted.

Previous studies illustrated effective monitoring and operations capacity building is necessary for successful policy implementation and program outcomes. Organizations with strong monitoring and operations capacity are better equipped to implement policies and programs successfully (Bryson, Crosby, and Stone, 2015). Through SEM results, it is indicated that there is a significant relation between local collaborative governance and monitoring and operations capacity in multiple sector organizations in Pakistan, which validated research hypothesis H6. So, H6 is accepted.

Collaborative governance has been associated with improved public service responsiveness to local needs and demands (Ansell, Gash (2008); Emerson, Nabatchi, and Balogh, 2012). Several studies have shown that service capacity mediated the relationship between collaborative governance and the responsiveness of public services (Lewis et al., 2016). Service capacity can influence the ability of organizations to deliver services in a timely and effective manner, and can affect the quality and responsiveness of those services (Roberson and Choi, 2009). Through data analysis, research results showed that service capacity partially mediates the association between local collaborative governance and public service responsiveness in Pakistan which validated research hypothesis H7. So, H7 is accepted.

Previous studies found that evaluative capacity mediated the relationship between collaborative governance and tangible public services (Bryson et al., 2013). It is argued that evaluative capacity partially mediated the relationship between collaborative governance and program performance. Similarly, it is observed that evaluative capacity was positively associated with the delivery of tangible public services in developed countries (Cepiku et al. (2019)). Through SEM analysis, the evaluative capacity yields partial results. In this way, evaluative capacity partially mediates the association between local collaborative governance and tangibles of the public services in Pakistan, which validated research hypothesis H8. So, H8 is accepted.

Several previous studies showed that monitoring and operations capacity mediated the relationship between collaborative governance and reliable public services in Denmark and Australia in varying degrees (la Cour, 2016; Malik et al., 2022). It is concluded that monitoring and operations capacity is a key factor that enables local governments to deliver reliable public services in the context of collaborative governance. Through SEM analysis, it is indicated that M&O capacity partially mediates the association between local collaborative governance and reliability of the public services in Pakistan which validated research hypothesis H9. So, H9 is accepted.

Policy implications

First, local collaborative governance effectiveness depends upon establish goal consensus, which entails the development of a shared vision and objective. The importance of this matter is frequently highlighted in research on local collaborative governance and private-public partnerships discussions. In the absence of a cohesive and common vision, multisector organizations are likely to prioritize immediate gains and divert their focus from achieving successful public service delivery that could be achieved through sustained and comprehensive local collaborative efforts.

Second, achievement of favorable outcomes in addressing complex issues within a local collaborative governance structure required participants to undergo comprehensive training beforehand. This training equips managers with the necessary skills and knowledge to actively participate in collaborative endeavors. Relevance of this issue is further emphasized when taking into account the potential connection between project management and the public service response on regular basis. There is a noticeable change in the dynamics of the work process experience within the framework of local collaborative governance. This change is characterized by increased levels of interconnectivity and complexity. This transition requires a matching adaptation in the characteristics of instruments utilized for public service and external demands imposed on system. Hence, it is imperative for managers participating in the collaborative endeavor to uphold their knowledge in their respective fields by ongoing multilateral contact.

Thirdly, the probability of achieving effective local collaborative governance is enhanced when there are established formal linkages across several sectors and organizations as well as process for execution shows more adaptability in the creation and operation of an institutional framework for collaboration. It is crucial to question the belief that a solitary governance model is the most effective and exclusive method for tackling a wide range of difficulties in public service delivery and maintaining integrity. The development of a standard operating procedure is utmost importance in enabling timely responses to public service delivery or contingency situation. The importance of roles and norms should not be underestimated; nonetheless, it is crucial to have a policy framework that enables actors to adjust and incorporate in collaborative setting.

Fourth, it is imperative to take into account the crucial aspects of time and money as incentive to participants enact change and foster the growth and progression of local collaborative governance initiatives aimed at enhancing public service delivery. Multisector organizations do not undergo immediate transformations. Given the variations in participant knowledge, cultural and national features, it is imperative to provide additional time and incorporate contingency planning for any delays right from the initial phase of formulating local collaboration strategies. Individuals tasked with overseeing the implementation of local collaborative governance must possess a system that consistently monitors the progress of the initiative, along with an evaluation methodology that effectively analyzed performance for valuable feedback.

In terms of practical implications to cope with local collaborative governance issues, public sector reforms must prioritize citizen participation through maintaining power imbalance among multi sector organizations in local collaborative governance. Policymakers, formal actors, informal actors, civil society organizations, and practitioners can build a broad consensus to consider a variety of measures to promote collaborative governance.

Local and provincial government autonomy conflicts can be resolved through horizontal and vertical collaborative reforms. To address conflicts regarding decision-making and resource allocation, it is crucial to establish distinct lines of constitutional amendments between local and provincial governments policy makers through regular consultation, trust, and legitimize reforms.

Additionally, local collaborative government must be promoted for economic growth and development through encouraging entrepreneurship and investment. By fostering an investment-friendly environment, local governments can generate employment opportunities and raise the standard of living for their citizens.

Pakistan has inadequate monitoring and evaluation mechanisms, limited financial autonomy and inadequate citizen participation. These obstacles impede collaborative governance and bottom-up strategies. To address these obstacles, the researcher advocated the need for a strong legal framework that is acceptable to all stakeholders through consensus building. Changing existing laws, acts, and regulations regarding local governments would be required. Given the socio-cultural legacies of Pakistani society, the researchers remarked that political will is necessary to advance these changes. Regarding the local government system, amendments in the constitution are not possible in the absence of broad consensus. Community-oriented development initiatives in Pakistan could be used to implement this specific concept for enhancing local collaborative governance and citizen engagement. These initiatives could target specific public services, including clean water, healthcare, education and infrastructure development. (Friend, Power, and Yewlett, 2013).

Collaboration on the administrative, political, and fiscal levels is also essential for local collaborative governance and effective public service delivery. Local policy implementation processes must incorporate principled engagement, shared motivation and the capacity for cooperative action. In addition, the significance of officer/manager training in achieving effective organizational performance and service delivery cannot be overlooked. Utilizing local collaborative potentials can strengthen the institutional capacities and resource generation capacities of underdeveloped districts. Local collaborative governance will be assured in Pakistan by consolidating the replacement of the current local government system with a robust collaborative drive. Local collaborative governance in Pakistan is contingent upon citizen participation, state substance, state assimilation, governmental ascendancy, organizational ascendancy, a solid foundation, a liberal, independent judiciary, press freedom, social, political and economic success. In order to reduce friction with the center of public service delivery, the implementation of the strategy requires the collaboration and active participation of numerous central, regional and municipal actors. The collaboration process can commence with the right drivers. In order to develop a collaborative governance framework to combat corruption, it is necessary to have open and honest communication among stakeholders, an effective mechanism for resolving cases, and a shared long-term goal. Even though early evaluations and results of the new system are less encouraging, it is hoped that the reforms are steps in the correct direction. Corruption, poverty, unemployment, illiteracy, and terrorism can be managed through local collaborative governance by bringing all stakeholders on board.

Local collaborative governance demonstrates collective wisdom and democracy to solve multifaced problems. First stage, domestic revamping of local government is more essential than global problems. With social progress, academic attention and public recognition, the collaborative governance concept will further permeate in public management theory. Serious factors as capacity deficits in local government that contain local government performance need readdressing commutatively like human capabilities, automated systems, legal and administration capacity and project management.

Conclusion

Local collaborative Governance typically includes multiple sector stakeholders with good intentions to contribute their ideas, impressions, partiality, human strength and weaknesses to the policy-making at the local level in Pakistan. Local collaborative governance will be ensured by replacing current local government system and development plans through strong collaborative drive in Pakistan. Local collaborative governance required citizen engagement, state substance, state assimilation, governmental ascendancy, a strong foundation, independent judiciary, press freedom, social, political, and economic success. Central, regional and local actors can engage in a dialog to develop strategy for local collaborative governance and better public service delivery. If all stakeholders are on board, the collaboration process can begin with the proper drivers. If early evaluation of the new system is deemed less promising, it is hoped that the public sector reforms will be in the right direction and overcome local collaborative governance challenges. Pakistan’s weak governance is also linked with political and economic instability. At institutional level, institutional capacity-building and public service reforms need revamping and replacing with friendlier and healthier atmosphere through training/capacity-building interventions.

Limitations and future directions

A number of limitations to this research can be identified, particularly. First, all dimensions of public service delivery and institutional capacity building are not covered in this research. Second, Multiple level analysis can also yield exclusive results. Third, special insight in the process of public service delivery based on experience, language and collaborative culture are taken into account. Fourth, the mediating effect of institutional capacity building was not as expected but a large data set can alter this outcome. Fifth, multi resource data collection can also resolve this issue. In the future, the research on local collaborative governance largely determined by leadership, information technology, negotiation, conflict management, coalition of elites, legitimacy, democratic culture, Citizen participation, political bargain, motivation, trust, civic engagement and other dimensions of capacity building.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Data set contains personal information of the respondents, which we are not allowed to share publicly.

Change history

15 December 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02505-0

References

Acemoglu D, Johnson S (2005) Unbundling institutions. J Polit Econ 113(5):949–995

Aga DA, Noorderhaven N, Vallejo B (2016) Transformational leadership and project success: the mediating role of team-building. Int J Proj Manag 34(5):806–818

Agger A, Löfgren K (2008) Democratic assessment of collaborative planning processes. Plan Theory 7(2):145–164

Annan-Prah EC, Andoh RPK(2023) Effects of customised capacity building on employee engagement, empowerment, and learning in Ghanaian local government institutions. Public Adm Policy 26(2):228–241

Ansell C, Gash AJJ (2008) Opar, & Theory. Collab Gov Theory Pract 18(4):543–571

Arshad MA, Shahid Khan K, Shahid Z (2020) High performance organisation: the only way to sustain public sector organisations. Int J Public Sect Perform Manag 6(6):806–816

Ary D, Cheser L, Asghar JR, Sorensen CK (2010) Introduction to Research in Education, 8th edn. Cengage Learning, Wadsworth

Bellé N (2014) Leading to make a difference: a field experiment on the performance effects of transformational leadership, perceived social impact, and public service motivation. J Public Adm Res Theory 24(1):109–136

Berthod O et al. (2023) The rise and fall of energy democracy: 5 cases of collaborative governance in energy systems. Environ Manag 71(3):551–564

Biddle JC, Koontz TM (2014) Goal specificity: a proxy measure for improvements in environmental outcomes in collaborative governance. J Environ Manag 145:268–276

Billing T (2019) Government fragmentation, administrative capacity, and public goods: the negative consequences of reform in Burkina Faso. Polit Res Quart 72(3):669–685

Bradford N (2016) Ideas and collaborative governance: a discursive localism approach. Urb Aff Rev 52(5):659–684

Bradley S, Mahmoud IH, Arlati A (2022) Integrated collaborative governance approaches towards urban transformation: experiences from the CLEVER cities project. Sustainability 14(23):15566

Bryson JM, Crosby BC, Stone MM (2015) Designing and implementing cross‐sector collaborations: needed and challenging. Public Adm Rev 75(5):647–663

Bryson JM, Quick KS, Slotterback CS, Crosby BC (2013) Designing public participation processes. Public Adm Rev 73(1):23–34

Cepiku D, Jeon SH, Jesuit DK (2019) Collaborative governance for local economic development: lessons from countries around the world. Routledge

Cingolani L, Fazekas M (2017) Administrative capacities that matter: organisational drivers of public procurement competitiveness in 32 European Countries. Cambridge University

la Cour A (2016) In search of the relevant other–collaborative governance in Denmark. Scand J Public Adm 20(3):55–75

Cristofoli D, Douglas S, Torfing J, Trivellato B (2022) Having it all: can collaborative governance be both legitimate and accountable? Public Manag Rev 24(5):704–728

Emerson K (2018) Collaborative governance of public health in low-and middle-income countries: lessons from research in public administration. BMJ Glob Health 3(4):e000381

Emerson K, Nabatchi T (2015) Collaborative governance regimes. Georgetown University Press

Emerson K, Nabatchi T, Balogh S (2012) An integrative framework for collaborative governance. J Public Adm Res Theory 22(1):1–29

Fledderus J, Brandsen T, Honingh ME (2015) User co-production of public service delivery: an uncertainty approach. Public Pol Adm 30(2):145–164

Frankowski A(2019) Collaborative governance as a policy strategy in healthcare. J Health Organ Manag 33(7/8):791–808

Friend J, Power JM, Yewlett CJL (2013) Public planning: the inter-corporate dimension, Vol. 5. Routledge

Gallagher MW, Brown TA (2013) Introduction to confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Quantitative Methods for Educational Research. Brill, p 287–314

Gash A (2022) Collaborative Governance. In Handbook on Theories of Governance. Edward Elgar Publishing, p 497–509

van Gestel N, Grotenbreg S (2021) Collaborative governance and innovation in public services settings. Policy Polit 49(2):249–265

Di Gregorio M et al. (2019) Multi-level governance and power in climate change policy networks. Global Environ Change 54:64–77

Grimm R, Spring K, Dietz N (2007) Corporation for National and Community Service, Office of Research and Policy Development. The health benefits of volunteering: A review of recent research

Grindle MS, Hilderbrand ME (1995) Building sustainable capacity in the public sector: what can be done? Public Adm Dev 15(5):441–463

Hair Jr JF, Matthews LM, Matthews RL, Sarstedt M (2017) PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: updated guidelines on which method to use. Int J Multivar Data Anal 1(2):107–123

Haque CE, Doberstein B (2021) Adaptive governance and community resilience to cyclones in coastal Bangladesh: addressing the problem of fit, social learning, and institutional collaboration. Environ Sci Policy 124:580–592

Hayes AF, Montoya AK, Rockwood NJ (2017) The analysis of mechanisms and their contingencies: PROCESS versus structural equation modeling. Aust Mark J 25(1):76–81

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2015) A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci 43:115–135

Hijazi M (2021) Relationship between project manager’s gender, years of experience, and age and project success. Walden University ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 28319311. https://www.proquest.com/openview/95d45e614bc8a80ddf516385284454ea/1?pqorigsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen M (2008) Evaluating model fit: a synthesis of the structural equation modelling literature. In (Edited by Dr Ann Brown) 7th European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies, 195–200, Academic Publishing limited, Reading, UK

Hu Li‐tze, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model Multidiscip J 6(1):1–55

Irfan SM, Ijaz A, Kee DMH, Awan M (2012) Improving operational performance of public hospital in Pakistan: a TQM based approach. World Appl Sci J 19(6):904–913

Jung Y-D, Mazmanian D, Tang S-Y (2009) Collaborative governance in the United States and Korea: cases in negotiated policymaking and service delivery. Int Rev Public Adm 13(1):1–11

Kamara RD (2017) Creating enhanced capacity for Local Economic Development (LED) through collaborative governance in South Africa. SocioEconomic Challenges 1(3):98–115. https://doi.org/10.21272sec.l.1(3).98-115.2017

Khan MS, Syrett S (2022) An institutional analysis of ‘power within ’local governance: a Bazaari tale from Pakistan. World Dev 154:105882

Khan M, Khurram S, Zubair DrSyedSohaib (2020) Societal E-readiness for e-Governance adaptability in Pakistan. Pak J Comm Soc Sci 14(1):273–299

Khan NU, Zhongyi P, Han H, Ariza-Montes A (2023) Linking public leadership and public project success: the mediating role of team building. Hum Soc Sci Comm 10(1):1–10

Klijn E-H, Edelenbos J, Steijn B (2010) “Trust in governance networks: its impacts on outcomes.”. Adm Soc 42(2):193–221

Koontz TM et al. (2004) Governmental roles in collaborative environmental management. Collaborative environmental management: What roles for government. An RFF press book, Published for the resources for the future, Washington DC,USA, 1–31, www.rffpress.org

Koontz TM et al. (2010) Collaborative Environmental Management: What Roles for Government-1. Routledge

Koontz TM, Craig WT (2021) Improving the use of science in collaborative governance. In Handbook of Collaborative Public Management, Edward Elgar Publishing, 313–30

Labin SN et al. (2012) A research synthesis of the evaluation capacity building literature. Am J Eval 33(3):307–338

Lai P-L, Kao J-C, Yang C-C, Zhu X (2022) Evaluating the guanxi and supply chain collaborative transportation management in manufacturing industries. Int J Shipping Transp Logist 15(3–4):435–458

Lewis JM, Ricard LM, Klijn EH, Figueras TY (2016) Innovation in city governments: structures, networks, and leadership. Taylor & Francis

Malik AH et al. (2022) Financial stability of Asian nations: governance quality and financial inclusion. Borsa Istanbul Rev 22(2):377–387

Mohmand SK, Cheema A (2007) Accountability Failures and the Decentralisation of Service Delivery in Pakistan. IDS Bulletin. Vol. 38, No. 1, Institute of Development Studies

Morin AJS, Myers ND, Lee S (2020) Modern factor analytic techniques: bifactor models, exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM), and Bifactor‐ESEM. Handbook of sport psychology. 1044–1073

Morse RS (2011) The Practice of Collaborative Governance. Vol. 71, No. 6, pp. 953–957, Wiley

Nabatchi T, Leighninger M (2015) Public participation for 21st century democracy. John Wiley & Sons

Nunnally Jum C (1978) An overview of psychological measurement. Clinical diagnosis of mental disorders: a handbook, 97–146

Peters BG, Pierre J (1998) Governance without Government? Rethinking public administration. J Public Adm Res Theory 8(2):223–243

Rajkumar AS, Swaroop V (2008) Public spending and outcomes: does governance matter? J Dev Econ 86(1):96–111

Ramayah T et al. (2017) Testing a confirmatory model of Facebook usage in SmartPLS using consistent PLS. Int J Bus Innov 3(2):1–14

Roberson PJ, Choi T (2009) Self-organization and responsiveness: a simulation of collaborative governance. In 10th National Public Management Research Conference. Oktobar, Citeseer, p 1–3

Schweizer K(2011) On the Changing Role of Cronbach’s α in the Evaluation of the Quality of a Measure. Eur J Psychol Assess 27(3):143–144

Shah I et al. (2022) Inter-agency collaboration and disaster management: a case study of the 2005 earthquake disaster in Pakistan. Jàmbá J Disaster Risk Stud 14(1):1088

Sørensen E, Torfing J (2011) Enhancing collaborative innovation in the public sector. Adm Soc 43(8):842–868

Tando CE, Sudarmo S, Haryanti RH (2019) Pemerintahan Kolaboratif Sebagai Solusi Kasus Deforestasi Di Pulau Kalimantan: Kajian Literatur. J Borneo Adm 15(3):257–274

Thomson AM, Perry JL, Miller TK (2009) Conceptualizing and measuring collaboration. J Public Adm Res Theory 19(1):23–56

Ullah I, Kim D-Y (2020) A model of collaborative governance for community-based trophy-hunting programs in developing countries. Perspect Ecol Conserv 18(3):145–160

Ullman JB, Bentler PM (2012) Structural Equation Modeling. Handbook of Psychology, 2nd edn. Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118133880.hop202023

Vaccari L et al. (2020) Application programming interfaces in governments: why, what and how. European Commission-JRC Science for Policy Report

Velez‐Ocampo J, Gonzalez‐Perez MA (2022) Internationalization and capability building in emerging markets: what comes after success? Eur Manag Rev 19(3):370–390

Wallis J, Dollery B (2001) Government failure, social capital and the appropriateness of the New Zealand model for public sector reform in developing countries. World Dev 29(2):245–263

Widaman KF, Thompson JS (2003) On specifying the null model for incremental fit indices in structural equation modeling. Psychol Methods 8(1):16

Wu X, Ramesh M, Howlett M (2015) Policy capacity: a conceptual framework for understanding policy competences and capabilities. Policy Soc 34(3–4):165–171

Xu S, Liu Y, Chen M (2017) Optimisation of partial collaborative transportation scheduling in supply chain management with 3PL using ACO. Expert Syst Appl 71:173–191

Zeithaml VA, Parasuraman A, Berry LL (1990) Delivering quality service: balancing customer perceptions and expectations. Simon and Schuster

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) under the metaverse support program to nurture the best talents (IITP-2023-RS-2023-00254529) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MZUD, NUK, and XYY conceptualized the research idea; MZUD and NUK conducted the surveys and performed the analysis; NUK and MZUD wrote the first draft of the manuscript. XYY and HH helped in the first review of the manuscript. All authors critically discussed the results, revised the manuscript and have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This research adheres to the ethical standards and guidelines outlined in the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its subsequent amendments. To the best of our knowledge, all of the research procedures were performed within these ethical standards. Approval was obtained from the competent authorities, including the Graduate Committee of the School of Public Administration, Central South University, China, and the College of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Sejong University.

Informed consent

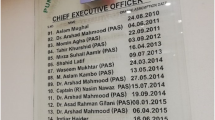

Informed consents were obtained in August 2022 from the study participants, including local administrators and managers of multisector organizations and their immediate subordinates from various districts in southern Pakistan. All the participants were accessed with the support of the Chief Secretary (Administrative Head) of Provinces, Pakistan. Response Participants were provided with comprehensive information regarding the study’s purpose and procedures. Confidentiality and privacy safeguards were strictly implemented throughout the research process.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zia ud din, M., Yuan yuan, X., Khan, N.U. et al. Linking local collaborative governance and public service delivery: mediating role of institutional capacity building. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 906 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02421-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02421-3

This article is cited by

-

Taking a partnership approach to embed physical activity in local policy and practice: a Bradford District case study

International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity (2025)

-

Understanding collaborative governance of biodiversity-inclusive urban planning: Methodological approach and benchmarking results for urban nature plans in 10 European cities

Urban Ecosystems (2025)

-

Integrating Circular Economy Principles in Achieving Net Zero Toward Sustainable Futures: India’s Perspective

Materials Circular Economy (2024)