Abstract

Longjing Monastery served as a prominent Buddhist center in Hangzhou during the Northern Song Dynasty. Similar to other esteemed Buddhist monasteries and mountains in China, the monastery’s initial prestige owed in part to its mystical associations with the Daoist recluse, Ge Hong. However, to secure sustained acclaim, adept leadership was crucial. Thus, this study delves into the monastery’s popularity during the Northern Song era, highlighting how the legendary abbot Biancai established both a robust personal reputation and monastic success by “making friends in the outside secular world.”

Similar content being viewed by others

The Su brothers, Zhao (Bian), and Qin (Guan) were Biancai’s friends in the outside secular world (fangwai jiao). Their masterpieces illuminate springs and rocks, which is the reason why the old and desolate Longjing Monastery has become so renowned. Thus, shouldn’t Biancai be acknowledged for its flourishing success?

Gazetteer of Lin’an of the Xianchun Era

Introduction

Prominent mountains and monasteries hold an integral position within Chinese culture, as they not only possess captivating landscapes and majestic structures but also convey substantial cultural import. As eloquently expressed in “An Epigraph in Praise of My Humble Home” (Loushi ming) by the Tang Dynasty scholar Liu Yuxi (772−842), “Hills are not necessarily [meant] to be high; the presence of gods gains them fame; lakes are not necessarily [meant] to be deep; the existence of dragons makes them exuberant” (Liu, 2005). Given this association with celestial beings and mythical creatures, both mountains and lakes are imbued with a rich tapestry of mythological and spiritual significance.

Although the inherent associations with indigenous mythological compendiums bestow upon mountains a transcendent provenance, this alone is inadequate for securing prominence and widespread appeal for a religious site. As a result, monasteries and the people charged with running them must pursue more robust influence to facilitate continued growth. Within the spheres of social, cultural, and economic forces, there have been consistent efforts to secure patronage from the upper echelons of society, particularly local intelligentsia and officials (DeBlasi, 1998, 156).

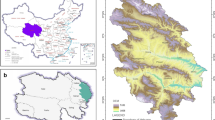

Longjing Monastery (Longjing Si) is nestled within the southern slopes of Hangzhou’s Nanshan, a foothill of the revered Mount Tianmu (Tianmu Shan) (Fig. 1). The earliest known individual associated with this location is the enigmatic Daoist hermit Ge Hong (283−343), who was captivated by its breathtaking natural beauty (Gazetteer of Lin’an of the Xianchun Era (Xianchun Lin’an Zhi), cited in Wang, 1884, 147). Specifically, he was intrigued by the Longhong well (see Fig. 2), which was rumored to house a dragon,Footnote 1 prompting him to choose the site for his alchemical pursuits.

Despite this, the extant records reveal that the prehistory of Longjing Monastery bears minimal connection to its subsequent development. This is primarily because the earliest known monastery in Longjing was built during the 14th year of the Kaihuang period (594) in the Sui Dynasty, approximately 250 years after Ge Hong was thought to be present at the site (Zhao, 2004). The Daoist elements also vanished over time. It is believed that a monk named Zhenguan (538−611) arrived at the mountain and constructed the Chong’en Yanfu Monastery (Chong’en Yanfu Si), known as Southern Tianzhu (Nan Tianzhu) to the locals (Gazetteer of Lin’an of the Xianchun Era, cited in Wang, 1884, 120).

Nonetheless, this Sui Dynasty monastery does not serve as a precursor to Longjing Monastery. The latter’s establishment is attributed to the Huguo Kanjing Monastery (Huguo Kanjing Yuan), constructed in 949 by a villager named Ling Xiao (n.d.). During the Xining period (1068−1077) of the Northern Song Dynasty, it was renamed Shousheng Monastery (Shousheng Yuan) (Gazetteer of Lin’an of the Xianchun Era, cited in Wang, 1884, 95) and bore witness to the remarkable accomplishments of Biancai (1011−1091). He forged friendships with contemporary elites, establishing an illustrious circle including Su Shi (1037−1101), Zhao Bian (1008−1084), Qin Guan (1049−1100), Su Zhe (1039−1112), and Mi Fu (1051−1107). Their collective influence contributed to the widespread renown of Longjing Monastery.

Unlike other local monasteries in Hangzhou, Longjing Monastery has only one gazetteer, the Record of What Was Seen and Heard in Longjing (Longjing jianwen lu), a collection of materials from various sources commemorating Emperor Qianlong’s (1711−1799) Southern Inspection Tour. Ten fascicles (juan) are included: landscapes (shanshui), historical sites (guji), renowned monks (minseng), famous visitors (xiangyu renwu), natural products (wuchan), inscriptions (beike), poetry (shi), essays (wen), anecdotes (yiwen), and an appendix (yulun). Additionally, there are two further fascicles titled the “Anecdotes of the Monk Yuanjing of the Song Dynasty” (Songseng yuanjing waizhuan), which contain documents relevant to Biancai but unrelated to Longjing Monastery. All of these materials contain original texts with titles in chronological order.

The integrity of the Record of What Was Seen and Heard in Longjing as an authoritative source in this research is accentuated by its assembly under the aegis of Wang Mengjuan (1721−1770), a Qing-era scholar-official, bibliophile, and poet (Su, 2012). Wang was a prominent academic who employed rigorous methodologies, which are reflected in the gazetteer’s depth and authenticity. While in this investigation, primary materials from the gazetteer, especially its poetic corpus, are heavily cited, there is no detailed textual criticism. Therefore, any potential variances between the original work and the version produced by Wang Mengjuan, irrespective of their typographical or substantive nature, are deemed inconsequential to the overarching interpretations and discourse propounded in this study.

Biancai: an old dragon of the Dragon Pool

Biancai is widely regarded as a gifted monk and a successful abbot, and both designations are entirely warranted, based on the various versions of his biography. The version presented below is sourced from the Gazetteer of Lin’an of the Xianchun Era:

Yuanjing’s (i.e., Biancai) original surname is Xu, and his courtesy name is Wuxiang. He was born in Yuqian and became a monk at the age of ten, learning under the guidance of Ciyun. After Ciyun died, he continued his studies under Mingzhi. When he was twenty-five years old, he was conferred the purple robe and the honorary title of “Biancai.” When Lü Zhen was the prefect of Hangzhou, he invited Yuanjing to stay in the Treasure Hall of Great Compassion for ten years. During Shen Wentong’s tenure as the Hangzhou administrator, Yuanjing was asked to manage Upper Tianzhu, and he changed the monastery’s affiliation from Chan Buddhism to Tiantai Buddhism. He was engaged in the expansion of the monastery into an enormous complex with multistory towers and high-rise pavilions that were unmatched in grandiosity in western Zhejiang, thus attracting significantly more learners than before. Despite successfully managing Upper Tianzhu for seventeen years, he was suddenly absolved of these duties and moved back to Yuqian. He returned to Upper Tianzhu the next year and lived there for another three years, after which he moved to Longjing of the South Mountain, where he remained for the rest of his life. As Yuanjing was diligent in practice, he achieved great spiritual attainment and was famous for his efficacious responses. He died in the eighth year of the Yuanyou period at the age of eighty-one. Su Zhe, the Vice Director of the Chancellery, drafted the inscription; Su Shi, the Hanlin Academician, wrote the inscription; and Ouyang Fei, Subeditor of the Academy of Scholarly Worthies, wrote the tablet. (Gazetteer of Lin’an of the Xianchun Era, cited in Wang, 1884, 125−126)

Receiving the purple robe and honorary title undoubtedly marked a pivotal moment in Biancai’s life. As John Kieschnick (1999) notes, the purple robe symbolized exceptional importance as emperors began bestowing it upon monks with special merit since the Tang Dynasty. Typically, local officials or royal family members petitioned the throne to bestow this recognition, reporting the discovery of an exceptionally worthy monk deserving of the purple robe.

Considering the excellent education in Tiantai teachings that Biancai received from Ciyun (964−1032) and Mingzhi (n.d.), as well as his remarkable diplomacy when confronted with the two prefects of Hangzhou, Lü Zhen (1014−1068) and Shen Wentong (1025−1067), it seems natural that Biancai would be recommended for such a prestigious honor. In fact, Biancai’s life was intrinsically linked to the robe itself; according to Su Zhe’s inscription, he was born with patterns on his left shoulder resembling those on the robe. These patterns were interpreted as a sign that Biancai was destined to become a great Buddhist master (Biographical Sketches of Eminent Monks at West Lake (Xihu Gaoseng Shilüe), cited in Wang, 1884, 285).

Recognized as a pivotal figure in both the Tiantai tradition and the Pure Land movement, Biancai, on the one hand, achieved enlightenment through the practice of the Great Cessation and Contemplation (Mohe zhiguan) and later became a prominent promoter of Tiantai Buddhism in Hangzhou. Also, at the request of Shen Wentong, he succeeded in changing the affiliation of Upper Tianzhu (Shang tianzhu) from Chan Buddhism to Tiantai Buddhism. On the other hand, Biancai was also a devoted Pure Land practitioner. According to Su Zhe, Biancai dedicated his entire life to the practice of the Pure Land and declared his journey to the Pure Land just before his death (Collections of Luancheng (Luancheng Ji), cited in Wang, 1884, 285). This is clear from Biancai’s “An Epigraph of the Teacher of the Mind” (Xinshi ming) (Collections of Luancheng, cited in Wang, 1884, 280):

Keeping single practice and never retreating

Nourishing the mind to go to the West (Pure Land)

Attaining unsurpassed wisdom

This is the Master of the MindFootnote 3

Throughout the seventeen years of his leadership at Upper Tianzhu, Biancai demonstrated exceptional leadership and social skills, for instance, expanding the monastery and securing imperial patronage (DeBlasi, 1998, 160−168). It is, however, important to highlight that the story of Biancai’s Longjing Monastery began before he arrived as, despite the monastery’s initial dilapidated state, followers eagerly began renovations upon hearing that Biancai planned to enter a retreat there. They presented him with a completely refurbished monastery as a gift.

In this new stage, Biancai once again employed his remarkable social skills to enhance the monastery’s reputation by establishing strong connections with leading literati. As the Gazetteer of Lin’an of the Xianchun Era remarks, Biancai was solely responsible for reviving the monastery, much like an old dragon bringing exuberance to an entire lake (Gazetteer of Lin’an of the Xianchun Era, cited in Wang, 1884, 96). Given his success, it is worth considering what kind of abbot could attract more attention from both ordinary followers and elite supporters. It seems clear that a successful abbot in Biancai’s time needed to possess outstanding religious practices, “magic powers,” and excellent written talents. In Biancai’s case, all three qualities are evident. Since his poetry is the primary focus of my discussion, I will first examine Biancai’s writing skills and talent. The following is a famous poem by Biancai (Gazetteer of Lin’an of the Xianchun Era, cited in Wang, 1884, 233):

Wearing gray hair I dwell on the rock and eat berries, among my old friends who can comfort me

Usually having a mutual affinity with Huagong, always sharing the same interests with Qinzi

Wandering under the moon I once came to this secluded valley, leaning on the stick I passed the cloud in the mist at dusk

Scholarly pavilions and mountain monasteries are fundamentally without difference, and so it is that wenzi is not separate from chanFootnote 4

This was likely one of the last poems Biancai wrote before his death. The reason this swansong endures is that Su Shi transcribed a copy and added a colophon, which is included in Su’s anthology:

When Biancai wrote this poem, he was already eighty-one years old. He never learned to write but could naturally present his thoughts, which were just like the wind crossing the lake. (In contrast), Can Liao and my peers write poems like weaving (Collected Works of Dongpo (Dongpo Ji), cited in Wang, 1884, 505)

Su not only lauded Biancai’s poetry but also urged his peers to perceive it through an alternative lens (“a third space,” as articulated by Jason Protass, 2022, 124); this lens is evocative of Bernard Faure’s (1996) assertion that poetry had paramount significance within “literary Chan” (wenzi chan) as a Buddhist movement affiliated with Song ChanFootnote 5:

A recurrent theme in “literary Chan” is that, despite appearances, the words of poetry, being the expression of Chan awakening, have a higher status than ordinary language. They are not the language of a deluded subjectivity that would create a hiatus in the natural flow of things, but rather the language that nature speaks through man.

Su Shi: Ashamed of being Compared to Taoling

As a unrivaled literary master of the Song Dynasty, Su Shi had exceptional literary talents and versatility that secured his position as a role model for Chinese literati ever since his death (Egan, 1994). In her book Tao Yuanming and Manuscript Culture: The Record of a Dusty Table, Xiaofei Tian (2005) vividly illustrates how Su Shi’s projection of his own concerns and ideal cultural image onto the Eastern Jin poet Tao Yuanming (365−427) altered both the circulating versions of Tao’s poems and the understanding of them. She also recounts a story about the extent to which people cherished Su Shi’s calligraphy, which ultimately meant that more attention was given to the calligraphy transcribing Tao’s poems than the content of the poems themselves. Naturally, as Biancai was a close friend of Su Shi, this association was advantageous for Longjing Monastery, and the monastery quickly became a popular attraction for contemporary literati. However, considering the numerous eminent monks in Hangzhou at the time, it is unclear why only Biancai received Su Shi’s respect and favor. This question was also posed by the compiler of the Record of What Was Seen and Heard in Longjing, providing the following answer:

Investigating Su Shi’s deeds when he was an official of Hangzhou, he sincerely enjoyed spending time with monks. He had countless friends such as Huibian, Daoqian, Liaoyuan, Zhongshu, Sicong, Huiqin, Huisi, Qingshun, Kejiu, Zongben, and Shanben. However, he only praised Yuanjing and Siming Huailian as the kind of monks who are admired both by monks and laymen. Daoqian also wrote poems to praise Yuanjing, Huailian, and Huibian as great masters, from which we can observe Yuanjing’s high character and pure deeds. (Collected Works of Dongpo, cited in Wang, 1884, 524)

The phrase “high character and pure deeds” is a stereotypical phrase that lacks specific meaning. Moreover, our modern perception of Su Shi as a rebellious genius contrasts with the humility and reverence he showed toward Biancai, as he consistently referred to Biancai as “teacher” and “master” in his poems and correspondence. Consequently, we believe that the complimentary description of “high character and pure deeds” is an oversimplification that fails to provide sufficient detail about the relationship between the two men. We must delve further into the details of their interactions to gain a clearer understanding.

The history of their friendship can be divided into two phases, with the first beginning in 1069. At that time, Biancai, a fifty-eight-year-old monk in charge of Upper Tianzhu, had already gained nationwide recognition as a great master of Tiantai Buddhism. Su Shi, then thirty-three years old and recently appointed as the Controller-General of Hangzhou, enjoyed befriending monks. Upon meeting, they quickly became close friends (DeBlasi, 1998, 160). On one occasion, Su Shi visited Biancai, not realizing that Biancai was out for a sermon. Disappointed, he composed the following poem (Collected Works of Dongpo, cited in Wang, 1884, 319):

At early dawn, I knock on the pine door

But alas, Master Zhi has been away for a long time

Mountain birds are silent, as the sky foretells snow

Rolling up the curtain, [I can see] only white clouds drifting by

Biancai later constructed the Snow Slope Pavilion (Xuepo Ting) at Upper Tianzhu to commemorate this visit. This poem is, however, not the sole piece that reflects Su Shi’s profound admiration for Biancai. His most emblematic work created during this time is entitled “Presented to Master Biancai of Upper Tianzhu” (Zeng Shangzhu Biancai Shi) (Collected Works of Dongpo, cited in Wang, 1884, 243):

In the north and south, a mountain gate; above and below, two Tianzhu monasteries

Within resides an old monk, lean and tall like a stork

Unaware of his practices, his jade eyes illuminate the valley

Upon seeing him, one feels refreshed, washing away the poison of vexations

He attracts all men and women in this metropolitan city to fall at his feet

I have a son with a long head, like wearing a jade-colored horn

He could not walk even at the age of four; it was tiring for my back and abdomen to embrace and carry him.

After the master touched his head, he could walk like a running deer.

Thus, I know from the precepts that extraordinary powers are without limitations.

No need to mention the Lotus Sutra, feigning madness, eating fish and meat

The first half of this poem highlights Biancai’s appearance and virtues, while the second half narrates how Biancai miraculously cured Su Shi’s younger son’s disability and is the most significant anecdote involving the two men. The son, Su Dai (1070−1126), was born to Wang Runzhi (1048−1093), Su Shi’s second wife. As per the records in the “Inscription of Master Biancai” (Biancai fashi bei) and the “Anecdotes of Monk Yuanjing in the Song Dynasty,” Su Dai was born with hydrocephaly and was still unable to walk by the age of four (Zhao, 2004, 39). Therefore, Biancai suggested having Su Dai tonsured in the presence of the Bodhisattva Guanyin and performed a head-touching ritual (Moding). Remarkably, just a few days later, Su Dai was able to walk normally, just like his peers (Collected Works of Dongpo, cited in Wang, 1884, 290).

Upon examining its structure and plot, the narrative in question appears to be a standard example of a Buddhist miraculous tale. However, this assessment should not detract from the story’s authenticity. Su Shi had no reason to fabricate his account, particularly since it was written to honor a monk. The tale’s importance is further enhanced by the fact that Su Shi’s son was indeed suffering from health problems at the time, lending credibility to the claim of miraculous healing.

In addition to its supernatural components, this story provides insight into Su Shi’s demeanor of humility and admiration toward Biancai. For Su Shi, Biancai transcended the traditional roles of a prominent monk or cherished friend; he was the miracle worker who had preserved his son’s life. This critical element serves to clarify Su Shi’s desire to praise Biancai beyond his contemporaries. By acknowledging Biancai’s mystical abilities, Su Shi was not merely expressing gratitude but also manifesting his deep-seated respect for Biancai’s knowledge and abilities across various realms.

It is now clear how the legend began to develop: a renowned monk named Biancai received a purple robe and honorary title at the young age of twenty-five; he then cured the young son of Su Shi, who was a prominent literary figure of his time. This event created a lot of buzz and caught the attention of many prominent literary figures. An interesting example of the widespread renown gained by Biancai is provided by Yang Jie (1055−1101), the author of the “Record of the Yan’en Yanqing Monastery” (Yan’en yanqing yuan ji):

Afterwards, I read the exchange of poems between Zizhan and the master, which mentioned that his son was too sick to walk and that owing to the master’s blessing, he could walk after getting older. Thus, I know the master’s great spiritual attainment. (Collected Works of Dongpo, cited in Wang, 1884, 94)

The second phase of the friendship between Su Shi and Biancai commenced in 1088 when Su Shi was appointed the prefect of Hangzhou and Biancai retired to Longjing Monastery. Biancai had become advanced in age, and physically weakened, he became weary of receiving a multitude of visitors every day. Therefore, he made a vow that he would not venture beyond the stream that flowed near the monastery.

On one occasion, while bidding farewell to his closest friend, Biancai became so engrossed in his conversation with Su Shi that he failed to notice he had already passed the stream. Passersby ridiculed him, drawing comparisons to Huiyuan (334−416) of the Jin Dynasty, who said goodbye to Tao Yuanming as he crossed Tiger Creek (Huxi). In response, Biancai quoted a couplet by Du Fu (712−770) (Gazetteer of Lin’an of the Xianchun Era, cited in Wang, 1884, 100):

We will become two elders together, even with some panache in our friendship

The trip was also memorialized by Su Shi in the following poem (Collected Works of Dongpo, cited in Wang, 1884, 242):

I am ashamed of being compared to Taoling, but you, master, are more admirable than YuangongFootnote 6

You passed the stream to see me off; thus, the stream should flow back to remember this moment.

Let the people of this mountain forever remember our trip as two elders

The world is under control, so why worry about parting

Due to Su Shi’s utilization of the phrase “Two Elders” in his poem, the local inhabitants subsequently began referring to the pavilion and the bridge over the stream as “Two Elders Pavilion” (Er’lao ting) and “Two Elders Bridge” (Er’lao qiao), respectively (see Fig. 3). As explained by Zheng Qingzhi (1176−1252), these sites consequently became well-known tourist destinations:

(After) Poxian (namely, Su Shi) arrived in Qiantang, Biancai became his good friend at the monastery. Later, after the master retreated to Longjing, Pogong wrote the “Poem on the Two Elders Pavilion.” Together, they visited several places of interest near the monastery, and their beautiful words covered the springs and rocks and were still vivid as flying on the dead twigs and dilapidated walls (Collections of the Hall of Anwan (Anwantang Ji), cited in Wang, 1884, 311).

Zheng, who was also a noted visitor of Longjing Monastery, wrote a couplet honoring Su Shi and Biancai’s friendship (Collections of the Hall of Anwan, cited in Wang, 1884, 251):

The two romantic elders returned to Mount Lingjiu, whose poetry inherited the literary lineage of the Elegies of Chu and On Encountering Sorrow

Although Su Shi could not have predicted the far-reaching impact of his poetic works, he was known for his unwavering support of Longjing Monastery. This is evident in his numerous efforts to encourage his acquaintances to visit the monastery. For instance, Su Shi encouraged his younger brother, Su Zhe, author of the “Inscription of Master Biancai,” to visit Hangzhou upon his return to the capital from Xuancheng. This recommendation included a visit to Longjing Monastery because it was one of the must-see places for Su Shi. However, for reasons that remain unclear, Su Zhe never reached the monastery. Instead, he sent three poems to Master Biancai (Collections of Luancheng, cited in Wang 1884, 244).

Zhao Bian: drinking Dragon tea beside the Dragon Pool

According to records, a Three Sages Hall (Sanxian Tang) was located near Longjing Monastery, where the statues of Zhao Yuedao, Su Shi, and Biancai were worshiped. Zhao Yuedao, also known as Zhao Bian, was renowned for his honesty and upstanding nature as a Palace Censor. His biography is included in the History of the Song Dynasty (Songshi):

(Zhao) Bian, whose courtesy name is Yuedao, was a native of Xi’an of Quzhou. After passing the imperial examination and obtaining the title of Jinshi, he became a Prefectural Judge of Wu’an Jun. Zeng Gongliang recommended him for the position of Palace Censor, and in this position, he conducted impeachments without fearing bigwigs. He became the prefect of Chengdu and held the title of the Scholar of the Auxiliary in the Hall of the Dragon Diagram. After Emperor Shenzong ascended to the throne, Zhao was summoned to the Remonstrance Bureau. When he went to thank the emperor, the emperor said: “I heard that you rode to Shu with only one zither and one crane. Is your administration also as simple as that?” During his tenure as a prefect of Yuezhou, Zhao spared no effort in providing famine relief. At the time of his retirement, he held the position of Junior Guardian of the Heir Apparent. When he returned to Hangzhou, he passed down his position as the supervisor of public business of Liangzhe to his son Wu, who accompanied his father on his travels around the famous mountains. His posthumous title is Qingxian. (History of the Song Dynasty, cited in Wang, 1884, 157−159)

Zhao Bian was a close acquaintance of Su Shi. Given Su Shi’s considerable influence, it is highly probable that Zhao Bian became acquainted with Biancai through Su Shi’s introduction. Although it is unclear when exactly the two met, it is important to note that Zhao Bian composed the “Portrait Eulogy to Master Biancai” (Biancai fashi zhenzan) before Biancai retreated to Longjing in 1078 (Gazetteer of Lin’an of the Xianchun Era, cited in Wang, 1884, 489):

When you, master, left Tianzhu, the mountain was empty and ghosts were crying

When you, master, returned, the dharma hall was illuminated again

A great man with great compassion, you, master, are truly in whom we should take refuge

The first couplet is frequently cited to illustrate the sole instance of turbulence in Biancai’s life. According to historical records, a monk named Wenjie (n.d.) was envious of Biancai’s position and colluded with influential individuals to persuade the Transport Commissioner to strip Biancai of his administrative rights. Despite this setback, Biancai remained composed and relocated to Lower Tianzhu (Xia Tianzhu). However, Wenjie was not content with this outcome and even went so far as to coerce individuals to compel Biancai to return to his hometown. It was not until the following year that the court became aware of this injustice and invited Biancai back to Upper Tianzhu. It is reported that the monastery languished during Wenjie’s tenure as the head of Upper Tianzhu, and visitors were scarce; however, upon learning of Biancai’s return, crowds flocked to welcome him, and the monastery was revitalized (Collections of Luancheng, cited in Wang, 1884, 288−289).

In the second year of the Yuanfeng era (1079) during the spring season, antecedent to the culmination of Zhao Bian’s tenure, news reached him that Biancai had already withdrawn to Longjing Monastery. He paid a visit to Biancai and composed the first poem that linked Longjing with the cherished beverage of tea (Gazetteer of Lin’an of the Xianchun Era, cited in Wang, 1884, 110):

In the depths of the lakes and mountains lies the palace of the Brahma King

I return here after six years with gray hair on my sideburns

I am grateful for the warm welcome from my esteemed teacher.

We drink Dragon Tea atop the Dragon Pool Pavilion

Biancai also wrote a corresponding poem (Gazetteer of Lin’an of the Xianchun Era, cited in Wang, 1884, 110):

The star of the South Pole comes to the monk’s hermitage

Cyan flowers cover the dimly discernible ten-li roads

You sir now increase the merits of being a deity

For several times you intone the royal tea beside the Dragon Pool

The Dragon Tea, referred to as longcha in Zhao Bian’s poem, should not be mistaken for the world-renowned Longjing Tea of West Lake (Xihu Longjing cha). It was not until the late Ming Dynasty (1368−1644) that locals began using the name Longjing to describe the mountain teas of Hangzhou, including the highly sought-after tea grown near Longjing Monastery. Despite this fact, these poems are often wrongly cited as evidence that Longjing Tea originated during Biancai’s residency in the monastery, thus further boosting its reputation (Bao, 2004).

Although only two exchange poems between Zhao Bian and Biancai have survived to the present day, evidence from other sources indicates that their exchange of poems was followed extensively and played a significant role in promoting Longjing Monastery. For example, Yang Jie, who lived in the capital during the same period as Zhao Bian, stated that he became acquainted with Longjing Monastery through these poems, indicating that its significance extended beyond Hangzhou or the Jiangnan area (Gazetteer of Lin’an of the Xianchun Era, cited in Wang, 1884, 94).

Qin Guan: writing the name of the Dragon Well

In 1795, when Qin Ying (1743−1821), a distant descendant of Qin Guan, discovered the inscription of the “Record of Writing on Longjing” (Longjing timing ji) copied by Dong Qichang (1555−1636) in the ruins of Longjing Monastery, he sighed:

Why is Longjing so renowned? Because the monk Biancai once dwelled there. Why is the fact that Biancai once dwelled there widely known? Because my great ancestor Mr. Huaihai wrote the “Record of Longjing” for Biancai (Lu, 1997).

“The past was the past of words, not of stones” (Mote, 1973). Given Qin Ying’s opinion, it would not be an exaggeration to state that if one were to choose a single poem and essay that upheld the reputation of Longjing Monastery, Su Shi’s “Poem on the Two Elders Pavilion” would be the apt choice for the former, and Qin Guan’s “Record of Writing on Longjing” would be equally apt for the latter. Qin Guan’s record itself is as follows:

One day after the mid-autumn of the second year of the Yuanfeng period, I returned to Kuaiji from Wuxing through Eastern Hangzhou. Master Biancai sent me a letter to invite me to the monastery. When I left the city, it was already near dusk. Then, I took a boat to Puning and met the monk Canliao there. I asked, “Where is the sedan that Longjing Monastery sent to pick you up?” He answered, “Because I did not arrive on time, it left.” That night, the sky was so clear, and the moon was so bright that one could count the number of hairs on his head. Thereafter, I gave up on the boat and walked with a stick with Canliao along the lake. We left Leifeng, passed Nanping, and washed our feet in the Huiyin Brook. Then, we entered the Lingshi Dock and climbed on the Fenghuang Range through a byway. We rested in the Longjing Pavilion, sat on the rock, and drank spring water. We passed fifteen Buddhist monasteries from Puning onwards, all of which were silent. The lights of the nearby houses were flickering, grasses and forests were deep and serene, and the stream was a roaring torrent, none of which could be seen in the secular world. We arrived at the Shousheng Monastery late at night and visited Biancai in the Tidal Sound Hall. We left the next day. Written by Qin Guan of Gaoyou. (Collected Works of Huaihai (Huaihai Ji), cited in Wang, 1884, 309−310)

This concise and eloquent essay, which describes Qin Guan’s visit to Longjing Monastery with Daoqian (1043−1106), bears many similarities to his teacher Su Shi’s “Record of a Night Visit to the Chengtian Monastery” (Ji Chengtiansi Yeyou) (Zeng, 2017). However, the significance of this article on Longjing Monastery lies not only in its elegant language but also in its transformation into a “source text” that was carved onto rock in Mi Fu’s calligraphy. Simultaneously literary art by one of the most prominent Song literati, Qin Guan, and visual art by one of the greatest Song calligraphers, Mi Fu, the carving naturally became an important attraction and continues to draw a large number of tourists to this day. At least three travelogues of Longjing Monastery in the Record of What Was Seen and Heard in Longjing explicitly state that they were inspired by the “Record of Writing on Longjing.” This is exemplified by Zheng Qingzhi:

Only Shaoyou’s travelogue could match up with Yuanzhang’s calligraphy. Two ingenious works reflected each other, bound to shine forever. (Collections of the Hall of Anwan, cited in Wang, 1884, 311)

Zheng’s words provide insights into the enduring allure of masterpieces such as the “Record of Writing on Longjing” within the broader context of Chinese literary traditions. It highlights a reciprocal enhancement between the esthetic and intellectual qualities of Shaoyou’s travelogue and Yuanzhang’s calligraphy. This interplay is particularly significant given the historical and cultural importance of both calligraphy and poetry in China, as well as their frequent association with one another. The assertion “bound to shine forever” conveys the long-lasting influence and appreciation of these works, elevating transient natural scenery to an eternal cultural symbol (Shang, 2020).

Furthermore, when examining the emergence of the stone inscription as an integral facet of the “Project of Creating New Scenic Spots in Longjing Monastery,” it becomes apparent that Biancai, as a resourceful abbot of the monastery, played a pivotal and multifaceted role in this ambitious undertaking. Biancai’s astute leadership, perceptive foresight, and keen appreciation for cultural heritage were instrumental in realizing the successful execution of this project.

First, the decision to invite Qin Guan, a renowned literatus and figure of admiration in contemporary literary circles, to visit Longjing Monastery was a crucial catalyst for the creation of the stone inscription. By so doing, Biancai not only fostered literary exchange and discourse but also initiated a profound connection between an individual of great renown and the monastery. This connection would prove pivotal in the subsequent stages of the project.

Moreover, Biancai’s foresight prompted him to ask the revered calligrapher, Mi Fu, known for his masterful brushwork and artistic talent, to transform the travelogue into a work of calligraphy. By enlisting Mi Fu, Biancai demonstrated his ability to recognize and harness the artistic prowess of celebrated individuals, thereby elevating the artistic value and cultural significance of the project.

Last, Biancai’s meticulous oversight and supervision were evident in the final stage of the project, where he ensured the carving of the travelogue-turned-calligraphy onto the stone, ultimately creating the stone inscription of the “Record of Writing on Longjing.” Biancai’s commitment to preserving the integrity and cultural value of the work exemplifies his unwavering dedication as an outstanding abbot.

Conclusion

The popularity of a monastery or a mountain as a religious site is not solely reliant on its numinous origin. For a location to sustain lasting popularity, adept leadership capable of navigating a complex social, economic, and political landscape is vital. This study highlights how Biancai attained substantial personal and monastic success. Based on his case, it can be inferred that “making friends in the outside secular world” by establishing robust connections with elites and politicians can enhance an abbot’s reputation and guarantee the monastery’s popularity.

Notably, Biancai’s friendship with Su Shi showcased the qualities essential for a successful abbot: spiritual enlightenment, “mystical powers,” and literary prowess. Intriguingly, his demonstration of “magical power” when healing Su Dai’s ailment earned deep admiration from Su Shi, elevating him above many of his contemporaries. In his association with Zhao Bian, Biancai utilized his literary abilities to augment the monastery’s prestige through poetic exchanges. Finally, while Qin Guan’s travelogue is not directly related to the abbot’s religious and literary practices, it showcases his outstanding planning and organizational skills.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Notes

Longhong is also called Longjing by the natives.

Wang Mengjuan, Longjing jianwen lu (Record of What was Seen and Heard in Longjing), 10 vols. (Hangzhou: Jiahuitang, 1884), v.1, 10.

The Complete Essays of the Tang Dynasty (Quantag wen) wrongly attributes this work to the Tang monk Biancai, see Liu Changdong, “‘Xinshi ming’ zhuanzhe kao” (On Authorship of “An Epigraph of the Teacher of Mind”), Religious Studies, no.3 (2001): 76−80.

This line is translated by Jason Protass, see Jason Protass, The Poetry Demon: Song-Dynasty Monks on Verse and the Way (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2022), 129−130.

However, according to Protass, the phrase wenzi chan was seldom used in the Song period and, when it was, it most often referred to Huihong’s (1071–1128) book; no group, faction, or community called itself Wenzi Chan. See Protass, The Poetry Demon, 121−156.

Here, Taoling refers to Tao Yuanming, one of the best-known poets during the Six Dynasties period. Yuangong is the Buddhist monk Huiyuan who founded Donglin Monastery on Mount Lushan in modern-day Jiangxi province.

References

Bao Z (2004) "Guanyu xihu longjingcha qiyuan de ruogan wenti" (Some Questions about the Origin of Longjing Tea of West Lake). Orient Museum 49(2):81–93

DeBlasi A (1998) “A Parallel World: A Case Study of Monastic Society, Northern Song to Ming.” J Sung-Yuan Stud 28:155–175

Egan R (1994) Word, Image, and Deed in the Life of Su Shi. Cambridge; London: Harvard University Asia Center

Faure B (1996) Chan Insights and Oversights: An Epistemological Critique of the Chan Tradition. Princeton: Princeton University Press

Kieschnick J (1999) “The Symbolism of the Monk’s Robe in China.” Asia Major 12(1):9–32

Liu Y (2005) “Loushi ming” (An Epigraph in Praise of My Humble Home). In Selected Essays From A Selection of Classical Chinese Essays, translated by Luo J, 58. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Publishing Company

Lu Y (1997) Lenglu zashi (The Miscellaneous Account of the Cold Hermitage). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company

Mote F (1973) “A Millenium of Chinese Urban History: Form, Time, and Space Concepts in Soochow.” Rice Institute Pamphlet — Rice University Studies 59(4):35-65

Protass J (2022) The Poetry Demon: Song-Dynasty Monks on Verse and the Way. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press

Shang W (2020) Tixie mingsheng: cong huanghe lou dao fenghuang tai (Writing on Landmarks: From Yellow Crane Tower to Phoenix Terrace). Beijing: Joint Publishing

Su Y (2012) “Qingdai xiushui wangshi jiazu yu wenxue yanjiu” (A Study on the Wang Family of Xiushui and Their Literary Works in the Qing Dynasty). MA dissertation, Nanjing University

Tian X (2005) Tao Yuanming and Manuscript Culture: The Record of A Dusty Table. Seattle: University of Washington Press

Wang M (1884) Longjing jianwen lu (Record of What Was Seen and Heard in Longjing), 10 vols. Hangzhou: Jiahuitang

Zeng X (2017) “Cong ouranxing dao biranxing—du dongpo ‘ji chengtiansi yeyou shuhou’” (From Contingency to Necessity — A Reading of Dong Po’s “Record of a Night Visit to the Chengtian Monastery”). Research on Su Shi in China, 1:1-10

Zhao D (2004) Longjingcha tukao (The Illustrated Study of Longjing Tea). Hangzhou: Xiling Seal Art Society

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TYL is responsible for the argument, correctness of the statements and content of this paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by the author.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by the author.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lei, T. Biancai (1011–1091) and his friends in the outside secular world: Longjing Monastery in the Northern Song (960–1127). Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 211 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02540-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02540-x