Abstract

Indonesia’s Tobacco Excise Sharing Fund (DBHCHT) policy mandates that part of the fund be allocated for tobacco crop diversification – reducing the farmers’ reliance on the tobacco industry as well as implementing Article 17 of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC). We collected primary data from key stakeholders in four main tobacco-producing municipalities. A number of challenges related to DBHCHT utilization remained at subnational levels. The suboptimal use of DBHCHT could be explained in part by (i) constantly changing central government regulations, (ii) farmers’ unawareness of DBHCHT regulations, (iii) delays in DBHCHT allocation, and (iv) supply and demand mismatches. Although Indonesia has not been a part of the FCTC ratification, the DBHCHT mandate is in line with the FCTC article 17, i.e., promoting economically viable alternatives for tobacco farmers. This study concluded that DBHCHT utilization needs to go further to void this mandate given the challenges at the subnational level. Therefore, this study recommends additional technical and practical regulations involving multisectoral stakeholders and the use of DBHCHT to meet the financial needs of crop diversification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Article 17 of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) recognizes the importance of providing and supporting economically viable alternative activities for the livelihood of groups impacted by a decrease in tobacco demand, one of which is tobacco farming. This should provide a counteractive argument for the prolonged perception that tobacco control measures could lead to detrimental effects on tobacco farmers’ livelihoods, which has not been supported by well-grounded research. Conversely, recent literature agreed that tobacco farming is a poor economic undertaking for many farmers globally (Chingosho et al., 2021; Magati et al., 2019; Makoka et al., 2017; Sahadewo et al., 2021). As a result, tobacco farmers have been seeking more lucrative plantation options through crop diversification or substitution. However, in many tobacco-growing countries, farmers’ use of tobacco for economic viability remains a barrier (Appau et al., 2020). Therefore, there should be a strong government incentive to provide appropriate compensation and to accommodate crop diversification/substitution projects (Wan et al., 2021).

Tobacco farmers in Indonesia switch to other tobacco crops mainly because tobacco prices tend to decrease so that farmers lose income over time. This is also supported by research from the (World Bank, 2017), which shows that most tobacco-farming households were spending more on their tobacco production than they were earning from it when only direct expenditures were taken into account (i.e., not household labor). When the labor of household members is considered, the losses for tobacco farmers are greater. This is because input costs (fertilizers, insecticides, tobacco seedlings, etc.) are more expensive than other crop input costs. Therefore, it is not surprising that 53% of tobacco farmers rely on loans to grow tobacco.

A study showed that some tobacco farmers considered switching because of low prices due to unfair grading and unfavorable weather. After experiencing losses from farming tobacco, tobacco farmers who switched to nontobacco crops typically gained in profit (Sahadewo et al., 2020a, 2020b).

Similarly, tobacco farmers in the ASEAN region cultivate tobacco in a labor intensive manner by employing all family members (including women and children) starting from planting, harvesting, drying, and marketing. Most tobacco farmers are small farmers with narrow and unprofitable land due to the large input costs (land rent, tobacco seedlings, fertilizers, insecticides, etc.) and the low price of tobacco (Tan and Dorotheo, 2018).

Tobacco farmers in Indonesia are transitioning to alternative tobacco crops primarily due to the consistent decline in tobacco prices, which has led to sustained losses for these farmers over time. This phenomenon is substantiated by research conducted by the World Bank (2017), which reveals that a substantial number of households engaged in tobacco farming expended more on the production of tobacco than they received in earnings solely from it, not accounting for household labor. When considering household labor, the losses incurred by tobacco farmers are even more significant. This can be attributed to the higher input costs associated with tobacco cultivation, such as fertilizers, insecticides, and tobacco seedlings, which surpass those of other crop types. Consequently, it is unsurprising that 53% of tobacco farmers are dependent on loans to sustain their tobacco cultivation endeavors.

Moreover, a study indicated that certain tobacco farmers contemplate transitioning due to low prices, unfair grading practices and adverse weather conditions. Following unfavorable outcomes in tobacco farming, those farmers who made the shift to nontobacco crops typically experienced improved profitability (Sahadewo et al., 2020a, 2020b).

The circumstances surrounding tobacco farmers in the ASEAN region mirror these patterns. Tobacco cultivation demands intensive labor, engaging all family members, including women and children, in various stages, from planting and harvesting to drying and marketing. The majority of tobacco farmers are characterized as small-scale growers constrained by limited and unprofitable land holdings due to high input costs such as land rent, tobacco seedlings, fertilizers, and insecticides, in addition to low tobacco prices (Tan and Dorotheo, 2018).

Indonesia, as a vast tobacco growing country, addresses this concern by facilitating funding for tobacco farming diversification. Indonesia has a specialized Revenue Sharing Fund of Tobacco Products Excise (DBHCHT) which is sourced from the excise of tobacco products and will be allocated to local governments based on their share of national tobacco production.

According to Law No. 39 of 2007, 2% of government revenue from excise is allocated to provinces engaged in tobacco production and possessing tobacco manufacturing facilities, which contribute to the overall excise revenue. At the provincial level, the Regional Allocation Fund for Tobacco Excise (DBHCT) is distributed as follows: 30% to the province itself, 40% to municipalities engaged in tobacco production or housing tobacco manufacturing, and the remaining 30% to other municipalities. For instance, in 2021, a sum equivalent to 2% of the excise revenue, totaling 3.5 trillion rupiah, was disbursed among 26 provinces. Notably, the province of East Java received the most substantial share of the DBHCT, amounting to 1.9 trillion rupiah, while Central Kalimantan received the smallest portion, totaling 26 thousand rupiah.

The recent Ministry of Finance Regulation (PMK) No. 206/2020 mandated that these funds be utilized for three main activities, e.g., social welfare activities (50%), law enforcement activities (25%), and public health activities (25%). DBHCHT funding for tobacco crop diversification—or tobacco farming activities—is part of 50% of social welfare activities. Of this figure, 15% is exclusively allocated for tobacco farming activities (i.e., for tobacco input material improvement), whereas the remaining 35% is distributed among tobacco farmers and tobacco industry workers. A total of 35% of the funds aimed to provide financial assistance for tobacco farmers and tobacco industry workers who wished to exit tobacco farming/industry activities. Tobacco farming diversification was also included in 35% of the funding to reduce farmers’ dependence on tobacco crops. This allocation is eventually expected to increase tobacco farmers’ welfare. However, bottlenecks may hinder the ability of the input to achieve the expected output, outcomes, and impact, as identified by this study. Figure 1 below illustrates the expected impact of DBHCHT on addressing this issue in tobacco farming following the theory of change (Reddy, 2018).

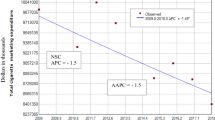

The use of Indonesia’s tobacco excise figure has been increasing during the past decade. This trend is mainly supported by the continuous increase in the tobacco excise tariff since 2015, which has an average increase of 10.92% annually. In 2021, Indonesia received more than 3.48 trillion IDRs from tobacco excises. Of this figure, 77.15% went to two main tobacco-growing provinces, e.g., East Java and Central Java. In addition to DBHCHT, local governments also received 10% of the local tobacco tax, 50% of which could also be utilized for mitigating the economic impact of tobacco control activities. Among the potential financing resources available, Indonesian tobacco farmers are constantly living in unfavorable circumstances (Sahadewo et al., 2020a, 2020b), while very little is known about the use of DBHCHT for improving tobacco farmers’ livelihoods. Considering this gap, this study aimed to evaluate DBHCHT utilization for Indonesian tobacco farmers, particularly in voiding Article 17 of the FCTC on tobacco crop diversification.

Methods

Data collection

The study was conducted in two main tobacco-producing provinces, East Java and Central Java. For each province, the two municipalities with the largest tobacco production shares were chosen. In 2019, 50.7% and 21.5% of the national tobacco production was shared by East Java and Central Java, respectively (Ditjenbun, 2021). We selected two municipalities in East Java, Pamekasan and Jember, which each shared 14.5% and 15.7%, respectively, of East Java’s tobacco production. Similarly, we selected Temanggung and Rembang for municipalities in Central Java. Among the accessions, 13.2% and 14.3% were shared with Central Java tobacco production, respectively.

Two series of focus group discussions (FGDs) and two series of in-depth interviews (IDIs) were conducted. The first FGD was conducted with current tobacco farmers (N = 25) as the main informants, while the second FGD invited ex tobacco farmers (N = 15) (i.e., no longer growing tobacco). Each FGD series was conducted in four rounds (as there are four municipalities). One researcher provided the participants with guiding questions, and one research assistant was included as a note taker. The main questions that were asked of participants in the FGD were as follows:

-

a.

Background characteristics of participants (age, sex, education)

-

b.

Tobacco farmer profile (tobacco area, work experience in tobacco farming, status of farming—rent/own, type of tobacco planted)

-

c.

The use of DBHCHT (receive grant from DBHCHT, receive seedlings, fertilizers, pesticide, hand tractor, training, etc.)

-

d.

Capital to cultivate tobacco (own capital, rent, selling livestock, partnership with tobacco manufacture)

-

e.

Profit or loss from tobacco farming

-

f.

Challenges in tobacco farming

-

g.

Tobacco price at the farmer level

-

h.

Diversification or switching to other crops

The first series of IDI was conducted at the national level and involved key resource persons from the Fiscal Policy Agency (Ministry of Finance), Directorate General of Plantations (Ministry of Agriculture), and Directorate General of Fiscal Balance (Ministry of Finance). The second series of IDI was conducted at the subnational level for each municipality. We conducted interviews with key resource individuals from the Regional Agricultural Agency, Regional Development Planning Agency, Agriculture Instructors, Farmers Support Group, Farmers Association, Civil-Based Organization, and, ultimately, tribal/village chief. Similarly, each IDI involved one researcher to provide the resource person with guiding questions and one research assistant as a note taker. The main questions asked of the informants in the in-depth interviews were as follows:

-

a.

Current policy overview of agriculture, especially tobacco farming.

-

b.

Conditions of Tobacco Farmer Welfare

-

c.

The use of DBHCHT based on No. 206/PMK.07/2020

-

d.

Responses to policy options (DBHCHT).

Patient and public involvement

Policy-makers and public members were engaged in identifying informants and participants as well as developing and designing the key questions. Furthermore, the FGD participants were also actively involved in the discussion and were allowed to add additional questions to other informants/participants—in addition to the key questions provided by the researchers. The key questions were asked by the researchers at the beginning of the discussion/interview. The results of the study were disseminated to public members through a public webinar in late January 2022.

Data analysis

Each FGD or IDI was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The data are analyzed using a content analysis technique whereby each data point is categorized based on a certain theme (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). We explored the informants’ perspectives on current DBHCHT utilization for tobacco farmers.

Results

Overview of tobacco farming

In Pamekasan, farmers reported that production and profits decreased compared to those in the previous year. The current selling price is Rp 27.000/kg, compared to Rp 45.000/kg to Rp. 50.000/kg previously. In addition to tobacco plants, three people from Pamekasan planted other crops (shallots, chili, and rice). All farmer informants in Pamekasan were unaware of DBHCHT. Farmers were told by the government to grow rice, tobacco, and corn, while another was given rice and corn seeds but the seeds failed. The farmers expect DBHCHT to be used for fertilizer and rice seedling assistance.

A farmer in Jember said there was indeed a decrease in the tobacco land area. Initially, ~23,000 ha were planted; now, only ~15,000 ha of plant area were planted. A decrease in tobacco use causes costs and expensive land rent. Most farmers reported that the production of tobacco has decreased. All the farmers agreed that the tobacco price fluctuates depending on its quality. Some farmers complain that their profit is decreasing because of increasing production costs. Some farmers had experience growing crops other than tobacco, including corn, chilies, red onion, and cabbage; this crop is known as DBHCHT. Farmers who received DBHCHT claimed to have received tobacco seed assistance for Kasturi tobacco, fertilizer assistance, intensification program assistance, and tobacco seed assistance. Farmers expect the BDHCHT to be sustainable and useful for increasing farmers’ welfare.

In Temanggung District, tobacco productivity is declining because the land area is decreasing every year. The decline in tobacco cultivation was also caused by the COVID-19 pandemic because the Regent of Temanggung urged farmers to focus more on growing food crops. The selling price of tobacco depends on its quality. The quality of the tobacco plants was determined by grade. In September, the highest price of tobacco produced by Tlahap farmers was Rp 65.000/kg, and the lowest was Rp 50.000/kg. The profit obtained is minimal enough for low-quality tobacco, which is valued at IDR 45.000/kg; for medium quality, it is valued at IDR 70.000/kg; and for the top quality, it is valued at more than IDR 100.000/kg. The most profitable commodity besides tobacco is coffee. They not only grew coffee but also processed it into products that were ready for consumption. Other commodities are not as profitable for them. For example, horticulture has high production costs and special care, but at harvest time, the price falls. Farmers in Temanggung are aware of the DBHCHT to which they are entitled. Farmers generally receive DBHCHT benefits in the form of fertilizer (Table 1).

In Rembang, the tobacco harvest cycle occurs once a year and fluctuates. The selling price of tobacco also does not increase. Breeders determine the price and quality of tobacco. Farmers claim that there is a monopoly because there is only one place to sell tobacco. The DBHCHT was more evenly distributed than in the other districts. Farmers said they had previously received machinery, fertilizers, and even comparative studies. Farmers expect DBHCHT to focus on helping land management and infrastructure grow tobacco. Farmers hope that there will be assistance for solar ovens in preparation for the rainy season for tobacco.

BDHCHT legal basis

Law No. 39 of 2007 stated that 2% of excise revenue that transfers to the provincial level shall be earmarked for the following activities:

-

a.

The quality improvement of the raw material used for tobacco,

-

b.

Tobacco industry coaching,

-

c.

Social environment development,

-

d.

Dissemination of excise regulation, and

-

e.

Law enforcement of illegal excise

Details of those activities were found in some Ministry of Finance Regulations. Since 2008, six Ministry of Finance Regulations have outlined the details of activities that can be financed using DBHCHT, namely:

-

a.

Ministry of Finance Regulation No. 84/2008

-

b.

Ministry of Finance Regulation No. 20/2009

-

c.

Ministry of Finance Regulation No. 28/2016

-

d.

Ministry of Finance Regulation No. 222/2017

-

e.

Ministry of Finance Regulation No. 7/2020

-

f.

Ministry of Finance Regulation No. 206/2020

Of the six Ministry of Finance regulations mentioned above, Regulation No. 206/2020 explicitly outlines the permissibility of utilizing the DBHCHT to financially support tobacco farmers seeking to diversify or transition away from tobacco cultivation. Furthermore, this regulation extends to encompass vocational training opportunities for laborers engaged in tobacco-related activities who aspire to transition to alternate occupations, alongside offering direct monetary assistance to both tobacco and cigarette laborers. Notably, this regulation also furnishes provisions for assisting and advising those tobacco farmers who remain committed to cultivating tobacco, encompassing the provision of essential inputs such as fertilizers, agricultural chemicals, and seedlings, as well as infrastructural enhancements such as road development and irrigation systems to facilitate tobacco cultivation. It is worth noting that preceding Ministry of Finance regulations were primarily centered around extending aid and guidance to the tobacco farming community.

Previous DBHCHT utilization

Prior to PMK No. 206/2020, no municipalities allocated DBHCHT for tobacco farming diversification. Following the preceding regulations, different municipalities applied different strategies for DBHCHT utilization. The variation in DBHCHT utilization across different municipalities was possibly due to differences in local government regulations. Since 2016, there has been no specific allocation for farming assistance from DBHCHT in Jember; hence, farmers received no benefits from DBHCHT. The DBHCHT was primarily distributed for health care and law enforcement programs. The case was similar in Pamekasan. In the absence of a maximum of 25% allocation for health care mandate, which was explicitly mentioned in PMK No. 206/2020, the local government of Pamekasan had been utilizing the DBHCHT for health care programs, primarily to support Universal Health Coverage (UHC) funding. However, tobacco farmers were still entitled to various production assistance programs ranging from vocational training to the provision of varieties of agricultural infrastructure.

The major allocation criteria for health care programs were also applicable in Temanggung. Following the preceding regulation of PMK No. 222/2017, the local government of Temanggung had been allocating more than 50% of its DBHCHT funding for UHC programs. Of the Rp31.47 billion total DBHCHT funding received in 2019, only Rp6.19 billion (19.7%) was allocated for tobacco farming purposes. However, UHC received up to Rp17.09 billion (54.3%) from the total DBHCHT fund. Similarly, in Rembang, during 2016–2019, DBHCHT was allocated for the provision of fertilizer and other agricultural infrastructure. In addition, the local government of Rembang took the initiative to develop low-nicotine tobacco leaves as part of the industry raw material and input advancement program funded by the DBHCHT. However, the allocation of DBHCHT for tobacco farmers in Rembang only accounted for 10% of the total DBHCHT allocation—far below the mandated figure (see Fig. 2).

“Prior to PMK 206, we (the government of Pamekasan) focuses on social security, particularly for healthcare provision for the poor. We allocated nearly 50% (of the budget) for health insurance” – Regional Development Planning Agency of Pamekasan. “We (technical facilitators) have no practical knowledge on DBHCHT. We never know how much of DBHCHT are allocated for farmers. We only know how much this year the government receives this amount and will be allocated for this or that program”— Agriculture Instructor in Jember. “I personally never received any DBHCHT allocation”—tobacco farmers in Rembang. “DBHCHT allocation for farmers never even reached 10% of the total allocation”—farmers’ support group in Rembang.

DBHCHT utilization after PMK No. 206/2020

In 2021, the local government of Pamekasan implemented the mandate of PMK No. 206/2020 in addition to other subsequent regulations (e.g., the Ministry of Agriculture’s Regulation and the Ministry of Home Affairs’ Regulation). The local government has accommodated the central government’s mandate by designing seven municipality programs for tobacco farmers. Four programs are dedicated to augmenting tobacco farming, while three others are part of tobacco farmers’ welfare improvement. However, our findings from the field informants (i.e., farmers and/or agriculture facilitators) suggested that only three programs were implemented, e.g., vocational training, provision of agricultural chemicals, and direct cash transfer.

The tobacco farmers’ eligibility to receive direct cash transfer from DBHCHT was regulated under “The East Java Regional Secretary’s Circular Letter” (Surat Edaran Sekretaris Daerah/SE Sekda). This regulation allows tobacco farmers to receive direct cash transfers from DBHCHT while also accepting other direct cash transfer programs – considering different objectives. This regulation is also the main reference for the local government of Jember in allocating direct cash transfers for tobacco farmers. However, another SE Sekda on DBHCHT utilization slightly contradicts the central government’s regulations whereby this regulation limits DBHCHT allocation for very few purposes (e.g., farming tools and equipment, agricultural chemicals, and farming infrastructure). This regulation oversees many programs mandated by the central government, such as vocational training, capacity building, financial assistance for farmers who wish to build their own enterprises, and direct cash transfer. However, tobacco diversification—which has also been postulated to be part of the DBHCHT “menu” in PMK No. 206/2020—has not received any budget allocation from the DBHCHT. Tobacco diversification across Rembang, Jember, Temanggung, and Pamekasan was largely the result of farmers’ own initiatives (see Fig. 3).

“We just held an audience with the government. Yes, indeed farmers who have received direct cash transfer (any other type) are eligible to accept DBHCHT. Previously (when the farmers were not allowed to receive double cash transfer), it was nearly impossible to identify eligible beneficiaries”—Tobacco Farmers Association of Pamekasan. “Even if we don’t allocate direct cash transfer, we still provide financing facilities. We also provide adequate infrastructure like farm road improvement to further facilitate the farmers” – Regional Development Planning Agency of Pamekasan. “PMK No. 206 doesn’t come with follow-up regulations providing technical guidance on the DBHCHT utilization, particularly for direct cash transfer. Hence, the governor (province) needs to pass on a circular letter so that each municipality won’t have their own regulation on this issue”—Regional Development Planning Agency of Jember.

Overcoming bottlenecks

These findings imply that the utilization of DBHCHT for tobacco farming in Indonesia has encountered several significant bottlenecks that have hindered its effective implementation. One major hurdle identified is the constantly changing government regulations governing the disbursement of these funds. To overcome this bottleneck, it is recommended that a multisectoral taskforce be established to enhance coordination among various stakeholders. Such a taskforce can streamline the regulatory process, ensuring that changes are thoroughly considered and that their implications for tobacco farming are better assessed.

Another critical bottleneck is the lack of awareness among tobacco farmers regarding the availability and benefits of the Tobacco Excise Sharing Fund. To address this issue, it is essential to organize structured socialization and educational campaigns. These initiatives should not only inform farmers about the fund but also educate them on how to access and effectively utilize it, empowering them to make informed decisions that can positively impact their livelihoods.

Another recurrent problem faced in the utilization of funds is the delayed implementation of policies related to disbursement. To mitigate this issue, it is recommended that technical and practical regulations be established at both the ministerial and local or subnational levels. This will expedite the decision-making process, reduce bureaucratic red tape and ensure that the allocated funds reach the farmers in a timelier manner.

The final bottleneck is the disparity between the total funds allocated and the actual number of farmers who should receive them. To address this supply and demand mismatch, it is crucial to create a well-organized database that accurately identifies eligible recipients. Such a database will enable better resource allocation, ensuring that the funds are distributed equally among the farmers in need, enhancing the efficiency of the utilization of the Tobacco Excise Sharing Fund.

Discussion

The constantly changing regulation of DBHCHT has been identified as one of the main challenges in DBHCHT utilization by the local government. Since it was first implemented, the Ministry of Finance’s regulation on DBHCHT utilization has been revised six times. The first PMK to mention DBHCHT utilization was PMK No. 84/2008, followed by its amendment to PMK No. 20/2009. In 2016, PMK No. 28/2016 annulled the preceding regulation, followed by PMK No. 222/2017, and in 2020, PMK No. 7/2020 was annulled by PMK No. 206/2020. All six regulations had different implications for the local government, as they implied different “menus” for DBHCHT utilization. Given Indonesia’s complicated bureaucratic process and complex regulatory hierarchy, this situation has resulted in inefficient DBHCHT utilization, as the local government needs to constantly adjust with changing regulations. In addition, the local government often mistranslates DBHCHT as a part of a central government grant. Hence, the posts for DBHCHT utilization in local government budgets might be incorrect and inconsistent with its main purpose, as DBHCHT is not a grant.

The local government’s confusion towards DBHCHT leads to farmers’ unawareness of DBHCHT. Neither the agricultural technical facilitators nor the farmer support groups were fully aware of the farmers’ rights to DBHCHT. This is the second main challenge for DBHCHT utilization. The technical facilitators were poorly informed about the DBHCHT utilization and therefore avoided being involved in the distribution process. With very little knowledge of DBHCHT, the technical facilitators are prevented from being guilty of any DBHCHT misuse.

The third challenge is the delay in DBHCHT utilization, which frequently occurs in some municipalities. For instance, in Pamekasan, vocational training that was supposed to be distributed prior to the harvest season was funded late, many times. This training was meant to assist the farmers in postharvest handling and to prevent them from postharvest loss. With the delay in distribution, training may become less valuable, and hence, the program becomes less efficient. Furthermore, the delay in financing assistance debilitates farmers’ preharvest financing. Many farmers are heavily indebted due to preharvest financing. This may result in farmers’ reliance on the tobacco industry and further interference from the tobacco industry. Under poor preharvest financing conditions, farmers will seek farming contracts and even loans from the tobacco industry.

Finally, the fourth challenge for DBHCHT utilization is the mismatch between the total DBHCHT received by the municipalities (supply) and the number of farmers in the municipalities (demand). The number of farmers far exceeded the total DBHCHT fund available. In Jember, only approximately 50% of the farmers successfully received financial assistance from DBHCHT. Similarly, in Pamekasan, only two out of 43 farmer support groups received funding. Aside from insufficient funds, the government’s inability to identify eligible beneficiaries and farmer unawareness were the main reasons for the inadequate DBHCHT distribution.

Studies on tobacco farming in Indonesia (Appau et al., 2020; Sahadewo et al., 2020a, 2020b; World Bank, 2017) offer limited insights into the role of DBHCHT as a policy instrument to encourage the transition of tobacco farmers towards alternative crops. In their report, (Sahadewo et al., 2020a, 2020b) stated that DBHCHT could be used not only to improve the quality of tobacco farming but also to prevent tobacco farmers from growing alternative crops. The World Bank (2017) recommended using additional tax revenue from reforming the tobacco excise tax (estimated from 129 to 147 trillion rupiah—World Bank, 2016) to help tobacco farmers switch to alternative crops.

Moreover, Ahsan et al. (2022) stated that DBHCHT could serve as a pivotal element within a mitigation strategy, aiding tobacco farmers in their transition to other agricultural pursuits. However, the efficacy of such efforts is impeded by the dearth of coordinated endeavors, underscored by the lack of consensus and shared objectives among cross-sectoral institutions. Notably, Ahsan et al. (2022) identified a significant reliance of local governments on technical regulations juxtaposed against the absence of horizontal interministerial and interinstitutional collaboration within the central governmental framework. Furthermore, Ahsan’s findings indicate that although diversification is mandated by Ministry of Finance regulations, the impetus for such initiatives predominantly stems from the farmers themselves, indicating a level of independence from governmental intervention. This autonomy within the farming community arises due to the inadequacy of technical regulations issued by the central government that would otherwise substantiate and foster cross-sectoral cooperation among local governments in harnessing the potential of the DBHCHT.

Policy recommendations to optimize DBHCHT utilization

Local governments argued that the MoF mandates that DBHCHT allocation be tied to each municipality’s needs, given different locality contexts. Some municipalities have fewer tobacco farmers and hence prioritized allocation to health sectors. In contrast, some programs that are relatively less of a priority (e.g., law enforcement, which contains only regulation socialization) should receive less allocation to increase DBHCHT allocation for tobacco farmers.

From the perspective of tobacco farmers, DBHCHT, as it partly serves to improve tobacco farmer welfare, should be allocated for market security rather than mere tools and equipment procurements. Tobacco farmers strongly agreed with PMK No. 206/2020 mandates on DBHCHT allocation for tobacco diversification, provided that the government ensures alternative crop prices and market security and provides further technical assistance.

Conclusion

While extensive literature has provided insights into tobacco control measures, there are very few discussions on how government accommodations impact tobacco farmers in the Indonesian context. This paper elucidates one of the government’s noble policies to provide financing mechanisms for tobacco crop diversification, i.e., DBHCHT. Our findings suggested that the inadequate DBHCHT utilization was mainly due to Indonesia’s complex bureaucracy process and hierarchical structure. According to PMK No. 206/2020, DBHCHT utilization involves multiple sectoral agencies (e.g., finance, agricultural, health, manpower, and law enforcement agencies). With multisectoral agency involvement and complex bureaucracy processes and hierarchy structures, DBHCHT monitoring and evaluation have narrowed to mere financial reporting, ignoring the substantive purposes of DBHCHT.

To establish measurable and sustainable outputs, PMK No. 206/2020 needs to be followed by more technical and practical regulations at both the ministerial and local government levels. At the next level, a multisectoral taskforce at the subnational level (primarily in main tobacco growing provinces/municipalities) may be necessary to convey overall DBHCHT implementation. This approach will be particularly relevant for tobacco crop diversification, as we found that tobacco crop diversification was mostly the initiative of farmers, whilst the government merely encourages with no practical support. The development of a multisectoral taskforce to support tobacco control measures with a specialized subnational committee to support tobacco crop diversification has been demonstrate by Bangladesh to be a sustainable tobacco control measure (Jackson-Morris et al., 2015), as it reduces farmers’ reliance on tobacco industries (Trinette, 2019). In addition, strong engagement with local nongovernmental organizations and cooperatives could provide technical support for tobacco crop diversification and substitution, as witnessed in Brazil (Trinette, 2019).

Mere encouragement alone is insufficient to support tobacco farming crop substitution, as some tobacco farmers are strongly attached to tobacco due to its perceived viability (Appau et al., 2019). While favorable financial access was mentioned as one of the factors driving farmers’ persistence in growing tobacco (Appau et al., 2019), providing financial assistance targeted for crop diversification may compensate for farmers not growing tobacco (Wan et al., 2021). Hence, we strongly recommend DBHCHT allocation to facilitate tobacco farmer crop diversification or even to facilitate the transition towards complete tobacco substitution.

Data availability

The data generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

24 January 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02682-6

References

Ahsan A, Ali PB, Rahmayanti KP, Siahaan RGM, Amalia N (2022) Mitigation Task Force for Farmer and Worker in Indonesia: a collaborative governance approach in tobacco control. J Perenc Pembang: Indones J Dev Plan 6(3):327–349. https://doi.org/10.36574/jpp.v6i3.287

Appau A, Drope J, Goma F, Magati P, Labonte R, Makoka D, Zulu R, Li Q, Lencucha R (2020) Explaining why farmers grow tobacco: evidence from Malawi, Kenya, and Zambia. Nicotine Tob Res 22(12):2238–2245. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntz173

Appau A, Drope J, Witoelar F, Chavez JJ, Lencucha R (2019) Why do farmers grow tobacco? A qualitative exploration of farmers perspectives in Indonesia and Philippines. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(13):2330. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132330

Chingosho R, Dare C, van Walbeek C (2021) Tobacco farming and current debt status among smallholder farmers in Manicaland province in Zimbabwe. Tob Control 30(6):610–615. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-055825

Ditjenbun (2021) Statistik Perkebunan Unggulan Nasional 2019-2021. Direktorat Jendral Perkebunan Kementerian Pertanian Republik Indonesia, pp 1–88

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 15(9):1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Jackson-Morris A, Chowdhury I, Warner V, Bleymann K (2015) Multi-stakeholder taskforces in Bangladesh — a distinctive approach to build sustainable tobacco control implementation. Int J Environ Res Public Health 12(1):474–487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120100474

Magati P, Lencucha R, Li Q, Drope J, Labonte R, Appau AB, Makoka D, Goma F, Zulu R (2019) Costs, contracts and the narrative of prosperity: an economic analysis of smallholder tobacco farming livelihoods in Kenya. Tob Control 28(3):268–273. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-054213

Makoka D, Drope J, Appau A, Labonte R, Li Q, Goma F, Zulu R, Magati P, Lencucha R (2017) Costs, revenues and profits: an economic analysis of smallholder tobacco farmer livelihoods in Malawi. Tob Control 26(6):634–640. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053022

Reddy AA (2018) Electronic national agricultural markets. Curr Sci 115(5):826–837

Sahadewo GA, Drope J, Li Q, Nargis N, Witoelar F (2021) Tobacco or not tobacco: predicting farming households’ income in Indonesia. Tob Control 30(3):320 LP–327. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055274

Sahadewo GA, Drope J, Li Q, Witoelar F, Lencucha R (2020a) In-and-out of tobacco farming: shifting behavior of tobacco farmers in Indonesia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(24):9416. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249416

Sahadewo G, Drope J, Witoelar F, Li Q & Lencucha R (2020b) The economics of tobacco farming in Indonesia: results from two waves of a farm-level survey. American Cancer Society

Tan YL, Dorotheo U (2018) The tobacco control atlas ASEAN region, Fourth Edition. In Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance (September)

Trinette L (2019) Country practices in the implementation of Article 17 (Economically sustainable alternatives to tobacco growing) of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. 17(December), pp 1–24

Wan X, Jin J, Ran S (2021) Willingness of tobacco farmers to accept compensation for tobacco crop substitution in Lichuan City, China. Tobacco Control. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056751

World Bank (2017) The economics of tobacco farming in Indonesia: health, population, and nutrition global practice. World Bank Group, pp 1–88

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Universitas Indonesia for providing the grant to conduct research through Indonesia Collaborative Research Program Grants (Program Penelitian Kerjasama Indonesia/PPKI) of the State Higher Education with Legal Entity Network (Perguruan Tinggi Negeri Badan Hukum / PTNBH).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work: AA contributed to project conceptualization, monitoring all stages of the project, and proofread the manuscript; NHW contributed to conceptualization, data collection, and proofread the manuscript; NA prepared and proofread the manuscript MV and RR contributed to data collection and transcription, AMY contributed to the whole project support and administration; YSP and SM contributed to the project conceptualization. All authors agree with the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study was approved by Medical and Health Research Ethics Committee (MHREC) Faculty of Medicine, Public Health, and Nursing Universitas Gadjah Mada (No. KE/FK/0433/EC/2021).

Informed consent

The authors confirm that informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians. The informed consent was written in language easily understood by participants and they had sufficient time to consider participation. At the beginning of the questionnaire, detailed explanations were given regarding the topic of the research and the confidentiality of the results, and that the results of this research would be used in the design of the wellness tourism model. They had the option to participate or not. And they signed “I have read and understand the information in this questionnaire. I have been encouraged to ask questions and all my questions have been answered to my satisfaction. I have also been informed that I can withdraw from the study at any time. By signing this form, I voluntarily agree to participate in this study” at the beginning of the questionnaire. The unit of analysis was the wellness tourists. In this research, the coordinator was responsible for clarifying the issue and answering the possible questions of the research participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahsan, A., Wiyono, N.H., Amalia, N. et al. Early assessment of tobacco excise sharing fund as policy for farmers’ viable alternatives in Indonesia: case study of four municipalities in Indonesia. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 89 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02585-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02585-y