Abstract

As a double-edged sword, the Internet is prone to breed cyber violence and bullying on the one hand, on the other hand, it can promote the expansion of altruistic behavior in cyberspace. Exploring the mechanism of generating Internet altruistic behaviors can help improve adolescents’ adaptive development and build a harmonious online environment. In light of this, this study constructed a hypothetical model of parental emotional warmth and adolescents’ Internet altruistic behaviors with gratitude trait as the mediating variable and belief in a just world as the moderating variable, in order to investigate how personal experiences, personality, and social cognition affect the practice of Internet altruistic behavior. A total of 1004 adolescents from two middle schools in China were selected for the survey. The results showed that parental emotional warmth significantly and positively affects adolescents’ Internet altruistic behaviors, while gratitude mediated this path between the two, with the mediating effect accounting for 27.07% and 24.27% of the total effect in the model of paternal and maternal emotional warmth, respectively. Moreover, in the paternal emotional warmth model, this indirect effect was moderated by belief in a just world, and the indirect effect was stronger for adolescents with lower beliefs in a just world relative to those with higher beliefs. Relative to paternal emotional warmth, belief in a just world was not significant in moderating the indirect effects of maternal emotional warmth on Internet altruistic behavior through gratitude. This research aims to provide more empirical research on the mechanisms of adolescents’ Internet altruistic behaviors and to provide more insights into the promotion of responsible and appropriate Internet use among adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Internet can be a breeding ground for violence, for example, exposure to violence in websites and other online media, and exposure to interactive online games with violent content can lead to an increase in personal violence and aggression; at the same time, the anonymity and real-time interactivity of the Internet can facilitate online interactions that are aggression-tinged, including cyberbullying and online sexual solicitation and victimization (Subrahmanyam et al., 2011). Nevertheless, the Internet also provides a platform for altruistic behavior. With growing concerns about a harmonious online environment and psychosocial health, examining the mechanisms by which Internet altruistic behavior emerges can help us better address the challenges of cyber violence. More importantly, with the latest official media reports that the number of underage Internet users in China has exceeded 193 million and basically reached saturation, it is of more profound and broader educational significance to explore how to promote adolescents’ Internet altruistic behaviors in order to strengthen the education of Internet literacy and to guide the adolescents to positive and healthy Internet surfing.

Internet altruistic behavior, also known as cyber-altruism, encompasses actions of benevolence and selflessness exhibited by individuals in the online realm, proactive behaviors that bring forth benefits to both others and society at large (Zheng and Gu, 2012). Individuals commonly demonstrate Internet altruistic behavior through various means, such as providing support, guidance, sharing, and reminders, among others. For instance, Internet support refers to affirming the actions of others online, including positive responses to posts, likes, words of encouragement, and well-wishes; Internet sharing involves freely dispensing one’s possessions and resources that others require online, without any form of remuneration. Compared to real-world altruistic behaviors, Internet altruistic behaviors are not bound by temporal or physical constraints, encompass a broader scope, and exhibit greater flexibility in their manifestations, thus occurring with increased frequency and diversity (Bosancianu et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2022). This phenomenon has garnered the attention of scholars in the field of social psychology, particularly within the framework of positive psychology (Amichai-Hamburger, 2008; Cox et al., 2018; Erreygers et al., 2017).

Fostering Internet altruistic behavior holds a unique significance for adolescents living in the epoch of the Internet. Adolescence is a critical period for humans to develop social and cognitive abilities and experience the formation of personal value sets (Tian et al., 2019). During this period, adolescents who engage in more altruistic behaviors are better able to understand the feelings and experiences of others, cultivate empathy and compassion tendencies, and develop positive interpersonal relationships for better social adaptation (Leontopoulou, 2010). Additionally, the experience of successfully helping others can enhance adolescents’ sense of self-worth, boost their self-confidence, and increase their subjective happiness (Post, 2005). As an extension of altruistic behavior in real life to cyberspace, Internet altruistic behavior not only represents a prosocial inclination to reach out to others but also holds significant importance for adolescents’ adaptive development. As a theory that focuses on the healthy development of adolescents rather than on problematic behaviors, the positive youth development perspective considers adolescent development from a more holistic and balanced perspective, emphasizing the malleability of adolescent development and arguing that any adolescent has the potential for positive and healthy development, supported by the adolescent’s own strengths and external developmental resources (Chang and Zhang, 2013; Shek et al., 2019). The positive youth development theory provides a new framework and path for research on promoting adolescent development. The developmental assets framework, one of the most widely used models, refers to a set of relevant experiences, relationships, skills, and values that are effective in promoting healthy developmental outcomes for all adolescents (Benson et al., 1998). By synthesizing research findings from multiple fields, scholars at the Institute have proposed a framework consisting of 40 developmental assets, 20 for external and 20 for internal assets (Benson et al., 2007). Hence, based on the positive youth development theory, this study aims to explore how adolescents’ personal experiences, personality traits, and social cognition affect the practice of Internet altruistic behaviors in terms of both external and internal developmental resources.

Experiences during the childhood years shape one’s disposition and behavioral pattern, where the emotional responses from parents may exert a deep influence. Parental emotional warmth refers to the praise, unconditional love, and support and coordination provided by fathers and mothers in response to children’s requests and demands, aiming to nurture their personality, self-regulation, and self-assertion abilities (Arrindell et al., 1999; Liu and Wang, 2021), serves as a crucial aspect that warrants investigation within the context of parenting style. The positive youth development theory highlights that the development of teenage behavior is influenced by a combination of external and internal assets (Benson et al., 2011). Undoubtedly, the family serves as a crucial external micro-environment, and within the family unit, parental emotional warmth has consistently been shown to be a constructive external asset that plays a pivotal role in fostering positive behaviors in teenagers. Individuals raised in an environment characterized by parental emotional warmth are more likely to cultivate a benevolent attitude toward their surroundings, develop a strong capacity for empathy, and display heightened awareness and willingness to assist others (Feng et al., 2021). Recent studies have confirmed that parental style can serve as a positive predictor of Internet altruistic behavior. Zhang et al. (2021) have verified that parental emotional warmth plays a significant and positive role in predicting Internet altruistic behavior. Parents who provide their children with greater support and care lead to an increased display of Internet altruistic behaviors in their children. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis (H1): paternal emotional warmth and maternal emotional warmth act as significant positive predictors of adolescents’ Internet altruistic behavior.

However, the contribution of parenting to Internet altruistic behavior is multifaceted, including the development of habits, abilities, and personality traits. In particular, parents with a warm parenting style usually bring up descendants with respectable personalities. Research has revealed a close association between Internet altruistic behavior and positive personality traits (Zhang et al., 2021). Gratitude involves acknowledging and appreciating benefits given by others to oneself and has been linked to agreeableness, empathy, and forgiveness (McCullough et al., 2002). The disposition to be grateful plays an important role in developing and maintaining social engagement by motivating people to behave in ways that also benefit others (McCullough et al., 2008). Previous studies have found that parental emotional support is positively related to adolescents’ gratitude, while a distant parent-child relationship is negatively associated with gratitude (Quan et al., 2022). As the primary external developmental environment for adolescents, parental factors can influence the development of gratitude traits (Hoy et al., 2013). Emotional warmth provided by fathers and mothers can reduce the distance between them and their children, providing adolescents with more emotional support, which contributes to the formation of gratitude.

Along the way, cultivating the trait of gratitude will motivate children to engage in prosocial activities more frequently. According to the broaden-and-build theory, children with gratitude trait have a more broad-minded mindset and are able to look upon others and their assistance from a positive perspective (Fredrickson, 2001), thus could foster the development of stronger social relationships. At the same time, gratitude traits may provide adolescents with access to more positive resources, including encouragement and appreciation from others, as well as sharing of resources and opportunities, which encourage adolescents to exhibit more altruistic behaviors, either online or in real life (Bartlett and DeSteno, 2006). Therefore, parental emotional warmth may positively predict adolescents’ Internet altruistic behaviors by fostering individuals’ gratitude traits. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis (H2): gratitude plays a mediating role in the link between paternal and maternal emotional warmth and Internet altruistic behavior.

Except for personal experience and personality traits, the cognition of society would modulate one’s implementation of prosocial activities as well. For example, when people believe they are in a society with a fair norm and valuing justice at a high level, they feel free to help others, with fewer concerns about risk (Bègue et al., 2008). Belief in a just world, in a subjective sense, represents individuals believing that the external world operates in a just manner and that their actions will ultimately result in fair outcomes or rewards (Kong et al., 2021). As a positive value, belief in a just world could motivate adolescents to view the world with more proactive attitudes, which consequently make it easier to develop gratitude (Benson et al., 2011). Research has consistently shown that individuals with higher levels of belief in a just world also tend to have higher levels of gratitude (Huston and Bentley, 2010; Strelan, 2007; Liu et al., 2023). While the perception of society has a unique function in attitude construction, it might act jointly with micro-personal experiences to affect the way gratitude is established. As suggested by the positive youth development theory, individuals’ positive internal assets work in conjunction with external assets to promote holistic development and effective functioning in adolescents (Shek et al., 2019). Therefore, it is important to examine how belief in a just world, as a perception of external society, and parental emotional warmth, reflecting unique personal experiences, interact to influence an individual’s level of gratitude, which in turn influences the occurrence of Internet altruistic behaviors. Belief in a just world may act as a moderator in the pathway between parental emotional warmth and gratitude.

However, the moderating mechanisms of beliefs in a just world may differ in adolescents’ perceived paternal versus maternal emotional warmth. Specifically, across cultures, fathers and mothers are expected to assume different roles and adopt different parenting styles when interacting with their children (Shwalb et al., 2012; Roopnarine, 2015; Selin, 2014), which is particularly salient in the Chinese cultural context (Li and Lamb, 2015). Based on Confucian values, traditional Chinese culture sets distinct roles for fathers and mothers, with Chinese fathers expected to lead the family and emotionally refuse to express explicit warmth, while mothers are expected to take greater responsibility in caring for their children and provide more emotional warmth, support and love (Shek, 2000; Xiao et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2018). Empirical studies from different regions in the Chinese context confirm that adolescents perceive mothers as providing higher emotional warmth than fathers (Deater-Deckard et al., 2011; Wang, 2019). A meta-analysis study also showed that Chinese adolescents perceived maternal parenting attributes more positively than perceived paternal parenting attributes (Dou et al., 2020). Further, perceived maternal emotional warmth contributed more to the promotion of positive personality development in adolescents compared to perceived paternal emotional warmth (Yang et al., 2022). Thus, we can hypothesize that for adolescents holding either high or low just world beliefs, maternal emotional warmth maintains a strong and stable influence on the development of the gratitude trait, whereas, for paternal emotional warmth, different mechanisms exist for just world beliefs. For adolescents who believe that the world is unjust, they may have animosity and negative attitudes toward the world. However, when they receive encouragement, support, and embrace from their fathers, they are more likely to have positive emotional experiences, which can attenuate the negative influences and enhance their gratitude levels, thus promoting Internet altruistic behavior. In contrast, for adolescents with higher beliefs about a just world, the effect of paternal emotional warmth on their gratitude trait was relatively small. In summary, we propose two hypotheses: belief in a just world moderates the relationship between paternal emotional warmth and gratitude (H3a); the moderating effect of beliefs in a just world on the relationship between maternal emotional warmth and gratitude is not significant (H3b).

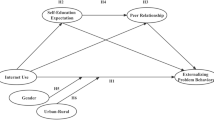

In conclusion, according to the positive youth development theory, this study aims to examine the role of paternal and maternal emotional warmth in predicting Internet altruistic behaviors among adolescents in a Chinese cultural context. It also explores the underlying mechanisms of this relationship by considering both cognitive and personality trait factors, including the moderating role of belief in a just world and the mediating role of gratitude. By constructing two moderated mediation models (see Fig. 1), this study contributes to the understanding of the mechanisms and their differences underlying the influence of parental emotional warmth on adolescents’ Internet behavior. Additionally, it provides empirical support for guiding adolescents’ Internet altruistic behavior in a scientifically informed manner.

Methodology

Participants

In this study, a convenience cluster sampling method was adopted to collect data from October to November 2022 from 1100 students from two junior high schools, using a paper questionnaire. A total of 1004 samples were retrieved after invalid samples were excluded due to catch items not passing or the response pattern being unreasonable; thus, the valid response rate was 91.27%. Of the valid samples, 484 and 520 were male and female students, respectively. The participants were aged 11–17 years [mean ± standard deviation (SD): 13.36 ± 1.00]. All samples were from different grades, including 341 (34.0%) in the first year of junior high school, 450 (44.8%) in the second year of junior high school, and 213 (21.2%) in the third year of junior high school.

Measures

Parental emotional warmth scale

The parental emotional warmth scale is a subscale of Egna Minnen Beträffande Uppfostran (EMBU), whose simplified Chinese version was revised by Jiang et al. (2010). The scale includes two dimensions: paternal and maternal, with each dimension containing 7 items. Participants responded on a 4-point scale, in which 1 indicates “never” and 4 indicates “always”. We created a maternal score and a paternal score for each participating student, calculated as the average of their corresponding 7-item scores; the higher the score is, the higher the paternal emotional warmth or maternal emotional warmth. In this study, the internal consistencies of the paternal emotional warmth dimension and maternal emotional warmth dimension were 0.924 and 0.920. Confirmatory factor analysis conducted for this study showed that the paternal emotional warmth (χ2/df = 3.886, RMSEA = 0.054, CFI = 0.992, TLI = 0.987, SRMR = 0.014) and the maternal emotional warmth (χ2/df = 4.462, RMSEA = 0.059, CFI = 0.992, TLI = 0.987, SRMR = 0.014) model fit indices were acceptable.

Gratitude questionnaire

The Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ-6) used in this study was developed by McCulough (2002) and has been well-validated among Chinese adolescents (Wei et al., 2011). The Gratitude Questionnaire consists of 6 items. A 7-point scoring scale was used, where 1 represents “strongly disagree”, and 7 represents “strongly agree”. The third and sixth items are reverse-scored, while the remaining items are scored in the forward direction. Scale scores are averaged across all items. A higher average score indicates a higher level of gratitude trait. The Cronbach’s α reliability coefficient in this study was acceptable (0.710). The confirmatory factor analysis conducted for this study showed that the scale model fit well: χ2/df = 2.189, RMSEA = 0.034, CFI = 0.996, TLI = 0.991, SRMR = 0.015.

Belief in a just world scale

The belief in a just world scale, developed by Dalbert in 1999 and translated by Su et al. (2012), includes 13 items. The scale comprises two dimensions: personal belief in a just world and general belief in a just world. A 5-point Likert scale was used (1 = “strongly disagree”, 5 = “strongly agree”). Belief in a just world is presented as each student’s mean score on the 13 items with a higher score indicating a higher level of just world beliefs. In the present study, the internal consistencies of the overall scale, personal belief in a just world dimension, and general belief in a just world dimension were 0.905, 0.864, and 0.824, respectively. The confirmatory factor analysis conducted for this study showed that the scale model fit indices were acceptable: χ2/df = 5.916, RMSEA = 0.070, CFI = 0.944, TLI = 0.931, SRMR = 0.037.

Internet altruistic behavior scale

The Internet Altruistic Behavior Scale designed by Zheng et al. (2011) was adopted in this study, which has been proven to be applicable to Chinese adolescents. This scale contains 26 items across four dimensions: Internet support (9 items), Internet guidance (6 items), Internet reminders (5 items), and Internet sharing (6 items). Participants rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “never”; 5 = “always”). The Internet altruistic behavior score was derived by averaging each student’s scores on 26 items; the higher the score, the more frequently the adolescent’s Internet altruistic behavior occurred. In the present study, the internal consistency of the overall scale was 0.943, and the four dimensions were between 0.801 and 0.887. The confirmatory factor analysis conducted for this study showed that the scale model fit indices were acceptable: χ2/df = 4.771, RMSEA = 0.061, CFI = 0.914, TLI = 0.902, SRMR = 0.044.

Data analysis

IBM SPSS 26.0 was used for preliminary data processing, descriptive statistics, reliability, and correlation analysis between variables. Model 4 and Model 7 in the PROCESS macro program (http://www.afhayes.com) were used to analyze the mediating role of gratitude and the moderating role of belief in a just world between parental emotional warmth and gratitude.

Common method bias test

In order to test the common method biases caused by the self-assessment questionnaire collection of all data, the Harman single-factor test was used in the study (Harman, 1976), and an exploratory factor analysis was performed on all items comprising the four scales. The results showed that ten factors had eigenvalues > 1. The first factor explained 24.90% of the total variance, which was below the 40% threshold criterion proposed by Podsakoff et al. (2003). Therefore, it suggests that common method bias is unlikely to confound the interpretations of the data analysis results.

Result

Descriptive and correlation analysis

Table 1 lists the results of the means, standard deviations, and correlation analysis among all variables. The correlation analysis results showed that paternal emotional warmth was significantly and positively correlated with Internet altruistic behavior, gratitude, and belief in a just world (r = 0.253, p < 0.001; r = 0.374, p < 0.001; r = 0.348, p < 0.001). Similarly, maternal emotional warmth was also significantly and positively correlated with Internet altruistic behavior, gratitude, and belief in a just world (r = 0.272, p < 0.001; r = 0.410, p < 0.001; r = 0.330, p < 0.001). Internet altruistic behavior was significantly and positively correlated with gratitude and belief in a just world (r = 0.240, p < 0.001; r = 0.284, p < 0.001). Gratitude was significantly and positively correlated with belief in a just world (r = 0.451, p < 0.001). In addition, the age variable also showed a significant correlation with the dependent variable Internet altruistic behavior (r = 0.106, p = 0.001), and this one variable will be added as a control variable along with gender in subsequent analyses.

Testing for moderated mediation

According to the results of the correlation analysis, the relationships between paternal emotional warmth and maternal emotional warmth with Internet altruistic behavior, gratitude, and belief in a just world met the requirements for conducting a moderated mediation test. To minimize issues related to multicollinearity, all predictors were mean-centered. It’s worth noting that all predictors had variance inflation factors below two, indicating the absence of multicollinearity in the study. The moderated mediating effects test was conducted using the SPSS macro program prepared by Hayes. Specifically, percentile bootstrapping, as well as bias-corrected percentile bootstrapping with 5000 resamples, were used to construct 95% confidence intervals for the indirect effects.

Testing for moderated mediation of paternal emotional warmth

Model 4 of PROCESS was used to test the mediating effect of gratitude between paternal emotional warmth and Internet altruistic behavior. Table 2 presents the results of this test. The findings partially support H1 that paternal emotional warmth significantly and positively predicted Internet altruistic behavior after controlling for the effect of gender and age (B = 0.181, SE = 0.022, p < 0.001). In addition, analyses indicated a positive relationship between paternal emotional warmth and gratitude (B = 0.461, SE = 0.036, p < 0.001). Then, gratitude entered the equation as a mediating variable. The predictive power of paternal emotional warmth was weakened but still significantly and positively predicted adolescents’ Internet altruistic behavior, and gratitude was a significant and positive predictor of adolescents’ Internet altruistic behavior (B = 0.131, SE = 0.024, p < 0.001; B = 0.107, SE = 0.019, p < 0.001). This suggests that gratitude partially mediates the effect of paternal emotional warmth on Internet altruistic behavior. To further assess the mediating effect of gratitude, we conducted bootstrapping with 5000 replications at 95% confidence intervals. The results indicated the significance of the mediating effect of gratitude with an indirect effect value of 0.049 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) excluding 0 (SE = 0.011, [0.030, 0.071], p < 0.001). The mediating effect accounted for 27.07% of the total effect. Thus, H2 was partially supported. These are specifically shown in Table 3.

Model 7 of PROCESS was used to determine whether the mediation effect was moderated by the belief in a just world. H3a stated that belief in a just world moderates the relationship between paternal emotional warmth and gratitude. Therefore, we introduced an interaction effect between belief in a just world and paternal emotional warmth to predict gratitude. Table 4 presents the unstandardized estimates of the model for H3a. The results shown in Table 4 reveal that the interaction term (paternal emotional warmth × belief in a just world) was a significant predictor of gratitude (B = −0.080, p = 0.017), which indicates that belief in a just world moderated the first half of the mediation in the effect of paternal emotional warmth on the Internet altruistic behavior through gratitude. Therefore, H3a was supported. To identify the interaction effect clearly at different levels of the moderator, we conducted a simple slope test (see Fig. 2). Consistent with what was expected, paternal emotional warmth is relatively strongly related to gratitude at a low level (1 SD below the mean) of belief in a just world (simple slope = 0.376, t = 8.101, p < 0.001). In addition, paternal emotional warmth is also significantly related to gratitude at a high level (1 SD above the mean) of belief in a just world, albeit relatively weak (simple slope = 0.230, t = 4.860, p < 0.001).

Next, the moderated mediation model of paternal emotional warmth was tested. The results, as presented in Table 5, compared the conditional indirect effects of paternal emotional warmth on Internet altruistic behavior through gratitude at various levels of belief in a just world. The index of moderated mediation (index = −0.009, SE = 0.004, 95% CI = [−0.018, −0.002]) was significant. The findings demonstrate that the indirect effect of paternal emotional warmth on gratitude is significant at low belief in a just world level (1 SD below the mean) (conditional indirect effect = 0.040, SE = 0.009, 95% CI = [0.024, 0.060]); Furthermore, there was a significant indirect effect at high levels of belief in a just world (1 SD above average) (conditional indirect effect = 0.025, SE = 0.007, 95% CI = [0.013, 0.041]). Nevertheless, for adolescents with a lower belief in a just world, the indirect effect of paternal emotional warmth through gratitude on Internet altruistic behavior was relatively stronger, whereas for adolescents with higher belief in a just world, the indirect effect of paternal emotional warmth through gratitude on Internet altruistic behavior was relatively weaker. Taken together, the effect of paternal emotional warmth through gratitude as a mediator on Internet altruistic behavior was moderated by adolescents’ belief in a just world (see Fig. 3, left). H3a was supported.

Testing for moderated mediation of maternal emotional warmth

We also used Model 4 of PROCESS to test the mediating effect of gratitude between maternal emotional warmth and Internet altruistic behavior. Table 6 presents the results of this test. The findings support H1 again that maternal emotional warmth significantly and positively predicted Internet altruistic behavior after controlling for the effect of gender and age (B = 0.206, SE = 0.023, p < 0.001). There was a positive relationship between maternal emotional warmth and gratitude (B = 0.516, SE = 0.036, p < 0.001). Subsequently, gratitude was included in the equation as a mediating variable. The predictive power of maternal emotional warmth was weakened but still significantly and positively predicted adolescents’ Internet altruistic behavior, while gratitude significantly and positively predicted adolescents’ Internet altruistic behavior (B = 0.156, SE = 0.024, p < 0.001; B = 0.096, SE = 0.019, p < 0.001). This suggests that gratitude partially mediates the effect of maternal emotional warmth on Internet altruistic behavior to some degree. Importantly, the mediating effect of gratitude was significant, with an indirect effect value of 0.050 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) excluding 0 (SE = 0.011, [0.027, 0.073], p < 0.001). The mediating effect accounted for 24.27% of the total effect. Hence, H2 was supported. Table 3 specifies these data.

We similarly tested the moderated mediation model of maternal emotional warmth using Model 7 of PROCESS. Table 7 presents the unstandardized estimates of the mother emotional warmth model. The results shown in Table 7 show that the interaction term (maternal emotional warmth × belief in a just world) was not a significant predictor of gratitude (B = −0.053, p = 0.122), which suggests that the moderating effect of belief in a just world was not significant. This result was not consistent with the moderated mediation model of paternal emotional warmth. Table 8 compares the conditional indirect effects of maternal emotional warmth on Internet altruistic behavior through gratitude at various levels of belief in a just world, with the moderating mediator index (index = −0.005, SE = 0.004, 95% CI = [−0.013, 0.001]) containing 0, which was not significant. This implied that there may be a specific predictive role for a mother’s emotional warmth. The results supported H3b that the moderating effect of beliefs in a just world on the relationship between maternal emotional warmth and gratitude was not significant (see Fig. 3, right).

Discussion

In the Chinese context, this study investigated the relationship between parental emotional warmth and adolescents’ Internet altruistic behavior, along with the mechanisms underlying this relationship. The results support parental emotional warmth not only directly influences Internet altruistic behavior but also exerts an indirect effect on such behavior through gratitude. It is worth noting that the relationship between paternal emotional warmth and gratitude was moderated by beliefs in a just world, and this relationship was particularly pronounced in adolescents with lower just world beliefs. However, this moderating effect was not observed for maternal emotional warmth. These findings revealed that there may be a different mechanism for maternal emotional warmth than for paternal.

Parental emotion warmth and Internet altruistic behavior

We observed that both parental emotional warmth and maternal emotional warmth positively predicted adolescents’ Internet altruistic behavior, and this finding aligns with previous research results (Zhang et al., 2021). This implies that individuals who experience greater emotional warmth from their parents are more inclined to assist others on the Internet. Parenting style could directly influence the psychological development of adolescents. Families that provide children with more care tend to have more harmonious parent-child relationships, and a peaceful family environment coupled with a harmonious parent-child relationship contributes to children’s overall well-being during their development. This, in turn, fosters a positive attitude towards life and encourages them to demonstrate greater care and understanding towards others (Alba and María, 2023; Renzaho et al., 2013).

The Mediating Role of Gratitude

In addition to discovering that parental emotional warmth and gratitude positively predict Internet altruistic behavior, our study has unveiled the mediating role of gratitude in the relationship between parental emotional warmth and Internet altruistic behavior, thus confirming our second hypothesis. This finding is in line with previous research indicating that individuals who experience high levels of paternal and maternal emotional warmth tend to cultivate a higher level of gratitude traits (Luo et al., 2021). As a vital component of an individual’s inner psychological resources, gratitude plays a mediating role in the connection between paternal and maternal emotional warmth and Internet altruistic behavior. A warm family environment fosters a stronger desire to offer help and support to others by effectively assisting adolescents develop positive character traits such as gratitude. Furthermore, adolescents who grow up in such an environment often have more positive experiences, enjoy better psychological well-being, and exhibit greater life satisfaction. Consequently, they are more prone to feeling grateful for the things they have, which influences their altruistic behavior (Tsang and Martin, 2019; van Kleef and Lelieveld, 2022).

The moderating effect of belief in a just world

Our study further revealed that adolescents’ beliefs in a just world had a moderating effect on the relationship between paternal emotional warmth and gratitude. Specifically, the relationship between paternal emotional warmth and gratitude was stronger for adolescents with a lower belief in a just world relative to those with a higher belief in a just world. This pattern of moderation supports the exclusionary hypothesis of the “Protective-Protective Model”, which states that one protective factor may diminish the predictive effect of another protective factor on the outcome variable (Bao et al., 2013). Drawing from this hypothesis, it can be inferred that if adolescents hold the belief that the world is fair, they are more inclined to prioritize personal effort and autonomy (Furnham, 2003). While paternal emotional support and affection can instill a sense of appreciation in adolescents, it may also steer them towards placing greater emphasis on the benefits that stem from their own diligence and capabilities (Boudreault-Bouchard et al., 2013; Li and Cheng, 2022). Conversely, when adolescents perceive the world as unjust, paternal emotional warmth can offer a sense of security and motivation, empowering them to feel bolstered in a challenging environment. In this context, paternal emotional warmth functions as a source of stability and assurance, aiding adolescents in navigating through diverse obstacles. This experience can heighten adolescents’ awareness of the support they receive from others (Bandura, 1978), ultimately fostering a disposition of gratitude and promoting altruistic behaviors among adolescents.

In our study, we also investigated whether there were differences in the moderated mediator models of paternal emotional warmth and maternal emotional warmth. Interestingly, we found that the moderating effect on beliefs in a just world was not statistically significant, despite the fact that maternal emotional warmth showed the same impact trend as the aforementioned paternal emotional warmth. This finding suggests that maternal emotional warmth may have specific characteristics that subtly distinguish it from paternal emotional warmth. In contrast, mothers are often perceived as the primary source of emotional security and care, and their support is viewed as more stable and enduring by children, irrespective of their beliefs in a just world (Li et al., 2023; Li and Meier, 2017). Consequently, maternal emotional warmth consistently shapes the development of grateful personalities and promotes Internet altruistic behaviors in adolescents, regardless of their perceptions of justice or injustice in the world. Furthermore, in the context of Chinese culture, where mothers are traditionally expected to provide emotional support and care, this societal expectation may further strengthen the influence of maternal emotional warmth on adolescents, thereby diminishing the moderating effect of belief in a just world (Hou et al., 2018). In short, this study deepens and expands the research on the relationship between parental emotional warmth and Internet altruistic behavior.

Research significance and limitations

This study has two important theoretical and practical implications. First, our study supports the theory of positive youth development. The external developmental environment will interact with adolescents’ personal strengths to jointly impact the development of their Internet altruistic behaviors, which provides new insights into the promotion of adolescents’ appropriate use of the Internet. In the education of adolescents’ Internet altruistic behaviors, more attention should be paid to the exploration of positive environmental factors that promote individual development, and the strengthening of the positive emotional connection between families, schools, and adolescents. Secondly, more attention should be paid to the promotion of adolescents’ intrinsic strengths and potentials, such as the cultivation of positive values and gratitude traits. We have reinterpreted the importance of parents improving their educational philosophies and the role of parents with different family roles in nurturing the development of good character in teenagers. This research provides practical educational suggestions from various perspectives, contributing to educational practice. For children who hold beliefs about an unjust world, a father’s care and education can provide a sense of security and strength, which has a significant positive impact on the development of gratitude traits. In Chinese culture, the role of the mother is even more special, the emotional warmth provided by the mother is strong and stable for the child, and the importance of the mother’s influence on the child’s positive personality traits is self-evident.

While this study has provided valuable insights, it has certain limitations. Firstly, there are limitations concerning the study’s scope. The study was conducted with students from only two middle schools in the Chinese region. This limited sample may introduce regional bias and impact the generalizability of the findings. Future research should aim to expand the sample size and diversify the cultural background to enhance the reliability and applicability of the conclusions. Secondly, we chose to conduct a simple slope analysis with M ± 1 SD. Indeed, this definition of high and low levels of belief in a just world may lead to subjective estimates that deviate from the truth and tend to lose important information about the moderator variable at other values. Therefore, future research could be conducted to identify more theoretically and practically meaningful thresholds in relevant contexts to validate or extend the findings of our study. Thirdly, future research could consider incorporating interventions, integrating research findings with practical teaching, and employing a variety of research methods, including experiments, observations, and interviews, to delve deeper into the subject. Finally, the comprehensiveness and reliability of the conclusions may benefit from longitudinal research and follow-up surveys. Subsequent research could employ a longitudinal approach to track the relationship between parental emotional warmth and Internet altruistic behavior among teenagers, offering a more dynamic and comprehensive understanding of the interplay among the four variables.

Conclusion

Based on the analysis of research data, the following conclusions have been drawn in this study. Firstly, parental emotional warmth in middle school students positively predicts Internet altruistic behavior. In a family environment that provides more warmth and encouragement, middle school students tend to engage in more Internet altruistic behaviors. Then, gratitude partially mediates the relationship between parental emotional warmth and adolescents’ Internet altruistic behavior. Individuals with a higher level of gratitude traits are more willing to engage in Internet altruistic behaviors. Individuals who feel grateful tend to exhibit more altruistic behaviors. Additionally, belief in a just world moderates the relationship between paternal emotional warmth and gratitude, and this effect of paternal emotional warmth on the development of children’s gratitude trait was stronger among individuals with lower just world beliefs. However, this result was not observed for maternal emotional warmth. The moderating effect of beliefs in a just world on the relationship between maternal emotional warmth and gratitude is not significant.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the Harvard Dataverse repository, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/5QECBX.

References

Alba GM, María (2023) The moderating role of family functionality in prosocial behaviour and school climate in adolescence. Int J Environ Res Public Health 20(1):590

Amichai-Hamburger Y (2008) Potential and promise of online volunteering. Comput Hum Behav 24(2):544–562

Arrindell WA, Sanavio E, Aguilar G, Sica C, Hatzichristou C, Eisemann M, van der Ende J (1999) The development of a short form of the EMBU: its appraisal with students in Greece, Guatemala, Hungary and Italy. Personal Individ Differ 27(4):613–628

Bandura A (1978) The self-system in reciprocal determinism. Am Psychol 33(4):344–358

Bao ZZ, Zhang W, Li DP, Li DL, Wang YH (2013) School climate and academic achievement among adolescents: a moderated mediation model. Psychol Dev Educ 29:61–70

Bartlett MY, DeSteno D (2006) Gratitude and prosocial behavior: helping when it costs you. Psychol Sci 17(4):319–325

Bègue L, Charmoillaux M, Cochet J, Cury C, De Suremain F (2008) Altruistic behavior and the bidimensional just world belief. Am J Psychol 121(1):47–56

Benson PL, Leffert N, Scales PC, Blyth DA (1998) Beyond the ‘village’ rhetoric: creating healthy communities for children and adolescents. Appl Dev Sci 2(3):138–159

Benson PL, Scales PC, Syvertsen AK (2011) The contribution of the developmental assets framework to positive youth development theory and practice. Adv Child Dev Behav 41:197–230

Benson PL, Scales PC, Hamilton SF, Sesma A Jr (2007) Positive youth development: Theory, research, and applications. In: Damon W, Lerner RM (eds) Handbook of child psychology, 6th ed. Wiley, New York, pp 894–941

Bosancianu CM, Powell S, Bratović E (2013) Social capital and pro-social behavior online and offline. Int J Internet Sci 8(1):e1025–e1036

Boudreault-Bouchard AM, Dion J, Hains J, Vandermeerschen J, Laberge L, Perron M (2013) Impact of parental emotional support and coercive control on adolescents’ self-esteem and psychological distress: results of a four-year longitudinal study. J Adolesc 36(4):695–704

Chang S, Zhang W (2013) The developmental assets framework of positive human development: an important approach and field in positive youth development study. Adv Psychol Sci 21(1):86–95

Cox J, Oh EY, Simmons BD, Graham G, Greenhill A, Lintott CJ, Masters KL, Woodcock J (2018) Doing good online: the changing relationships between motivations, activity, and retention among online volunteers. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 47(5):1031–1056

Deater-Deckard K, Lansford JE, Malone PS, Alampay LP, Sorbring E, Bacchini D, Al-Hassan SM (2011) The association between parental warmth and control in thirteen cultural groups. J Fam Psychol 25(5):790–794

Dou D, Shek DT, Kwok KHR (2020) Perceived paternal and maternal parenting attributes among Chinese adolescents: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(23):8741

Erreygers S, Vandebosch H, Vranjes I, Baillien E, De Witte H (2017) Nice or naughty? The role of emotions and digital media use in explaining adolescents’ online prosocial and antisocial behavior. Media Psychol 20(3):374–400

Feng L, Zhang L, Zhong H (2021) Perceived parenting styles and mental health: the multiple mediation effect of perfectionism and altruistic behavior. Psychol Res Behav Manag 14:1157–1170

Fredrickson BL (2001) The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol 56(3):218–226

Furnham A (2003) Belief in a just world: research progress over the past decade. Personal Individ Differ 34(5):795–817

Harman HH (1976) Modern factor analysis. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, USA

Hou F, Xinchun WU, Zou S, Liu C, Huang B, Education SO (2018) The association between parental involvement and adolescent’s prosocial behavior: the mediating role of parent–child attachment. Psychol Dev Educ 4:417–425

Hoy BD, Suldo SM, Mendez LR (2013) Links between parents’ and children’s levels of gratitude, life satisfaction, and hope. J Happiness Stud 14:1343–1361

Huston AC, Bentley AC (2010) Human development in societal context. Annu Rev Psychol 61:411–437

Jiang J, Lu ZR, Jiang BJ, Xu Y (2010) Revision of the short-form Egna Minnenav Barndoms Uppfostran for Chinese. Psychol Dev Educ 26(1):94–99

Kong Y, Cui L, Yang Y, Cao M (2021) A three-level meta-analysis of belief in a just world and antisociality: differences between sample types and scales. Personal Individ Differ 182:111065

Leontopoulou S (2010) An exploratory study of altruism in Greek children: relations with empathy, resilience and classroom climate. Psychology 1(05):377

Li M, Lan R, Ma P, Gong H (2023) The effect of positive parenting on adolescent life satisfaction: the mediating role of parent-adolescent attachment. Front Psychol 14:1183546

Li X, Lamb ME (2015) Fathering in Chinese culture: Traditions and transitions. In: Roopnarine JL (ed) Fathers across cultures: The importance, roles, and diverse practices of dads. Praeger/ABC-CLIO, California, p 273–306

Li X, Meier J (2017) Father love and mother love: contributions of parental acceptance to children’s psychological adjustment. J Fam Theory Rev 9(4):459–490

Li YI, Cheng CL (2022) Purpose profiles among Chinese adolescents: association with personal characteristics, parental support, and psychological adjustment. J Posit Psychol 17(1):102–116

Liu AC, Chen ZJ, Wang SC, Guo JP, Lin L (2023) Relationships between college students’ belief in a just world and their learning satisfaction: the chain mediating effects of gratitude and engagement. Psychol Res Behav Manag 16:197–209

Liu Q, Wang Z (2021) Associations between parental emotional warmth, parental attachment, peer attachment, and adolescents’ character strengths. Child Youth Serv Rev 120:105765

Luo H, Liu Q, Yu C, Nie Y (2021) Parental warmth, gratitude, and prosocial behavior among Chinese adolescents: the moderating effect of school climate. Int J Environ Res Public health 18(13):7033

McCullough ME, Emmons RA, Tsang JA (2002) The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. J Personal Soc Psychol 82(1):112

McCullough ME, Kimeldorf MB, Cohen AD (2008) An adaptation for altruism: the social causes, social effects, and social evolution of gratitude. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 17(4):281–285

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88(5):879–903

Post SG (2005) Altruism, happiness, and health: It’s good to be good. Int J Behav Med 12(2):66–77

Quan S, Li M, Yang X, Song H, Wang Z (2022) Perceived parental emotional warmth and prosocial behaviors among emerging adults: personal belief in a just world and gratitude as mediators. J Child Fam Stud 31:1019–1029

Renzaho AM, Mellor D, McCabe MP, Powell MB (2013) Family functioning, parental psychological distress and child behaviours: evidence from the Victorian Child Health and Wellbeing Study. Aust Psychol 48(3):217–225

Roopnarine JL (ed) (2015) Fathers across cultures: the importance, roles, and diverse practices of dads: the importance, roles, and diverse practices of dads. ABC-CLIO

Selin H (ed) (2014) Parenting across cultures: childrearing, motherhood and fatherhood in non-Western cultures. Springer Science & Business Media

Shek DT (2000) Differences between fathers and mothers in the treatment of and relationship with their teenage children. Adolescence 35(137):135−146

Shek DT, Dou D, Zhu X, Chai W (2019) Positive youth development: current perspectives. Adolesc Health Med Ther 10:131–141

Shwalb DW, Shwalb BJ, Lamb ME (2012) Final thoughts, comparisons, and conclusions. In: Shwalb DW, Shwalb BJ, Lamb ME (eds) Fathers in cultural context. Routledge, New York, p 385–399

Strelan P (2007) The prosocial, adaptive qualities of just world beliefs: implications for the relationship between justice and forgiveness. Personal Individ Diff 43(4):881–890

Su ZQ, Zhang DJ, Wang XQ (2012) Revising of belief in a just world scale and its reliability and validity in college students. Chin J Behav Med Sci 21(06):561–563

Subrahmanyam K, Smahel D (eds) (2011) Digital Youth: The Role of Media in Development. Springer, New York

Tian LL, Jiang SY, Huebner ES (2019) The big two personality traits and adolescents’ complete mental health: The mediation role of perceived school stress. School Psychol 34(1):32–42

Tsang J-A, Martin SR (2019) Four experiments on the relational dynamics and prosocial consequences of gratitude. J Posit Psychol 14(2):188–205

van Kleef GA, Lelieveld GJ (2022) Moving the self and others to do good: the emotional underpinnings of prosocial behavior. Curr Opin Psychol 44:80–88

Wang M (2019) Harsh parenting and adolescent aggression: adolescents’ effortful control as the mediator and parental warmth as the moderator. Child Abus Negl 94:104021

Wei C, Wu HT, Kong XN, Wang HT (2011) Revision of Gratitude Questionnaire-6 in Chinese adolescent and its validity and reliability. Chin J School Health 32(10):1201–1202

Xiao B, Bullock A, Coplan RJ, Liu J, Cheah CS (2021) Exploring the relations between parenting practices, child shyness, and internalizing problems in Chinese culture. J Fam Psychol 35(6):833–843

Xu L, Liu L, Li Y, Liu L, Huntsinger CS (2018) Parent-child relationships and Chinese children’s social adaptations: gender difference in parent-child dyads. Personal Relatsh 25(4):462–479

Yang MQ, Qu CY, Guo HX, Guo XC, Tian KX, Wang GF (2022) Machiavellianism and learning-related subjective well-being among Chinese senior high school students: a moderated mediation model. Front Psychol 13:915235–915235

Yang J, Wu Q, Zhou J, Huebner ES, Tian L (2022) Transactional processes among perceived parental warmth, positivity, and depressive symptoms from middle childhood to early adolescence: disentangling between-and within-person associations. Soc Sci Med 305:115090

Zheng XL, Gu HG (2012) Personality traits and Internet altruistic behavior: the mediating effect of self-esteem. Chin J Spec Educ 2:69–75

Zheng XL, Zhu CL, Gu HG (2011) Development of Internet altruistic behavior scale for college students. Chin J Clin Psychol 19:606–608

Zhang Y, Chen L, Xia Y (2021) Belief in a just world and moral personality as mediating roles between parenting emotional warmth and internet altruistic behavior. Front Psychol 12:670373

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Song Zhou contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, writing—review, and editing. Man Leng and Ji Zhang contributed to formal analysis, writing—original draft, review, and editing. Wenbo Zhou contributed to methodology, writing—original draft. Jiahui Lian contributed to conceptualization, methodology, and formal analysis. Huaqi Yang contributed to conceptualization, writing—original draft, review, and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study were approved by the Ethical Committee of Fujian Normal University (Ethics approval number: 20210310).

Informed consent

Informed consent and parent or legal guardian consent were obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, S., Leng, M., Zhang, J. et al. Parental emotional warmth and adolescent internet altruism behavior: a moderated mediation model. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 446 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02870-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02870-4

This article is cited by

-

What is internet for when studying is exhausting? Cyberaggression profiles associations to school stress management skills and study burnout among Polish and Turkish adolescents

Current Psychology (2025)

-

Social mindfulness related to internet altruistic behavior for college students of different genders: a latent profile analysis

Current Psychology (2025)

-

Exploring the relationship between parental styles and good personality: a network analysis

Current Psychology (2025)