Abstract

In unraveling the profound connections between humans and place, the traditional concept of the sense of place takes on new dimensions in the digital era. This study contributes to a nuanced understanding by integrating digital and physical spaces within the context of information and communication technology (ICT). Beginning with a review of historical changes and debates surrounding the sense of place, the research establishes a foundation for understanding the evolving relationship with the place. Building on this, the study explores the intricate interplay between digital media and place, revealing how advancements in digital technology shape perceptions of the sense of place. Beyond analysis, the study introduces a three-dimensional framework for the sense of place (i.e., physical sense of place, digital sense of place, and hybrid sense of place), recognizing the dynamic relationship between individuals and their environment, incorporating the digital dimension. Firmly grounded in the perspective of relationships, this framework captures multifaceted connections individuals establish with both physical and digital spaces. Finally, the research explores practical applications of this reconceptualized sense of place. This research deepens the current understanding of the complex dynamics in constructing places in contemporary society, where digital and physical realms intertwine. This research serves as a crucial steppingstone for comprehending the evolving dynamics of the sense of place in the digital era, presenting a refined framework that captures the complex relationships between individuals, technology, and the places they inhabit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It has recently been observed growing connections between space, place, and digital environments, highlighting that information and communication technology (ICT) is reshaping people’s experiences with space and place (Bos, 2021; Haefner & Sternberg, 2020; Liu, 2023a; Osborne & Jones, 2022). The debate regarding the relationship between space, place, and technology can be traced back to 1998 when geographer Graham (1998) published “The End of Geography or the Explosion of Place? Conceptualizing Space, Place, and Information Technology” in Progress in Human Geography. It has also become a foundational work for many concerns regarding ICT, space, and place relations. In the context of the remarkable growth of ICT over the past two decades, Ash et al. (2018) have coined the term “digital turn of geography” to summarize the transformative impact of ICT on the field. This can be observed in four levels: geographies through the digital, geographies produced by the digital, and geographies of the digital. The notion of “sense of place” stands prominently acknowledged as a cornerstone in human geography (Erfani, 2022; Lewicka, 2011; Relph, 2007; Tuan, 1977), swiftly capturing attention and integration within various social science disciplines (Lewicka, 2011; Scannell & Gifford, 2010). It refers to the subjective and emotional attachment that individuals or communities develop toward a particular place, based on their experiences, memories, and perceptions of that place (Scannell & Gifford, 2010; Tuan, 1977). With the increasing attention to ICT in geography and the growing influence of the digital era, there is a need to reconsider the concept of the sense of place from a digital perspective. In this context, it becomes crucial to explore and discuss how ICT, especially digital media, has influenced, mediated, or even created a sense of place. The advent of digital technologies has revolutionized how people experience and engage with places (Humphreys, 2010; Kinsley, 2014; Leszczynski, 2015, 2020). Virtual reality, social media platforms, online mapping, and other digital tools have expanded the possibilities for individuals to connect with places both physically and virtually (Ash et al., 2018; Bork-Hüffer, 2016; Bos, 2021).

On this basis, this research aims to reconceptualize and expand the notion of the sense of place within the context of digital transformation. This addresses the current significance of digital media as a vital platform for the production of human geography knowledge in recent years (Ash et al., 2018; Kellerman, 2023; Kinsley, 2014; Leszczynski, 2020; Liu, 2023a). Simultaneously, it establishes a conceptual framework for understanding the place experience of new digital media and forms an integrated and inclusive analytical approach for analyzing the sense of place by examining the knowledge context of digital media technology and place experience. Finally, this research delved into a thorough discussion on how to further apply the concept of sense of place in existing practices, offering insights and guidance from four perspectives: intelligent urban planning and management, community development and public space creation, tourism marketing and destination promotion, and immigration and daily life. We believe this way of thinking will be useful for researchers and government managers to understand human-place interaction and place experience in a more cutting-edge and inclusive way, and can bring valuable insights into the complex interplay between technology, human-place interaction, and the construction of a sense of place in the digital age.

Sense of place, placelessness, and global sense of place

The concept of place is central to the field of human geography (Graham, 1998; Lewicka, 2011b; Taylor, 1999), with the sense of place serving as a key area of research within this discipline. The theoretical foundations of the sense of place can be traced back to the discussions of phenomenologists Bachelard and Eliade, who emphasized the emotional and experiential bond between individuals and places, particularly in the context of home and religious sites (Seamon, 2013). Philosopher Heidegger used the term “dwelling” to describe the interaction between people and place, elevating the connection to a philosophical consideration of existence (Malpas, 2006). In the 1970s, geographers such as Tuan (1977) and Relph (2007) introduced this concept into the study of human geography, which argued that the infusion of cultural meaning and connections into space is what gives rise to its transformation into a place. These works have provided valuable insights into the understanding of place and the sense of place. They highlight the significance of cultural, emotional, and experiential dimensions in shaping our perceptions and attachments to specific locations.

Building upon these foundations, the emergence of concepts, theories, and measurement tools related to the sense of place (e.g., place attachment) marks the recognition of place as a crucial element for understanding the interaction between people and their environment (Taylor, Gottfredson, & Brower, 1985; Williams & Roggenbuck, 1989). After the seminal work on the measurement of the sense of place (Williams & Roggenbuck, 1989), researchers applied these concepts to various domains, including environmental protection, housing migration, leisure and tourism, and spatial planning, leading to rich theoretical and empirical contributions (Erfani, 2022; Mesch & Manor, 1998; Qian & Zhu, 2014; Ramkissoon & Mavondo, 2015). This has further advanced the theoretical application and disciplinary significance of place as a core construct (Lewicka, 2011; Scannell & Gifford, 2010). Concurrently, the concept and theory of the sense of place have extended beyond geography and have been embraced by other disciplines (Lewicka, 2011; Scannell & Gifford, 2010; Warnaby & Medway, 2013).

The impact of modernization and globalization has intensified the tension between “space” and “place” (Taylor, 1999), prompting researchers to reassess the concept of place (Jameson, 1992). One notable argument is put forth by Creswell (2004), who highlights that vibrant and diverse places are rapidly disappearing in a homogenous and disorderly environment characterized by meaningless architectural patterns. As space appears flat and detached from the local environment, people struggle to develop a strong sense of place attachment due to their inability to connect with the specific location they inhabit. In terms of specific manifestations, Relph (2007) defines “placelessness” as lacking autonomy, standardized, disorderly, lacking human scale and order, among other characteristics, and further identifies “Disneyfication,” “Museumization” “Futurization,” and “Rural Urbanization” as important landscape features of “placelessness”. Additionally, Meyrowitz (1986) explores the the transformation of place experience concerning the interaction between media and place.

Amidst the challenges and erosion of the conventional understanding of place, researchers such as Harvey (1990) and Massey (1994) have offered new insights and interpretations of the sense of place. Harvey (1990, 1995) focuses on power dynamics and social relations in the process of place construction, emphasizing the need to understand the formation of local differences in the perspective of capital operations. Building on Harvey’s perspective, Massey (1994) proposes the concept of the “Global Sense of Place”, highlighting that the essential characteristic of the place is its openness and connection with the wider world. It is suggested that the construction of place should be examined from a process-oriented perspective and that the global sense of place is compatible with locality. This new perspective has had a significant impact on subsequent research. As Giddens (1990) concluded, places have become “illusions”, not so much erased as disconnected from their histories, fragmented into a chaotic mix of distinctiveness, standardization, and connection, then reconstructed into networked hybrids where certain qualities are suppressed in some places and accentuated in others.

The sense of place in the digital age

Basic background

In the digital era, the discussion on the sense of place cannot be separated from the concept of digital space. With the rapid advancements in computer and internet technologies, virtual spaces have entered the purview of geographers (Ash et al., 2018; Kinsley, 2014). In this context, the body, code, data, infrastructure, and language have brought forth diverse spatial forms of computational change, drawing the interest and attention of geographers (Leszczynski, 2015, 2020; Relph, 2021). Within this body of research, the focus has primarily been on space as an intermediary, representational, and embodied code (Chan, 2008; Leszczynski, 2015; Sutko, De Souza E Silva, 2011), while the notion of place as the center of emotional and meaningful connection seems to have been overlooked (Osborne & Jones, 2022; Relph, 2021).

The background of the sense of place in the digital age originates from the integration of communication geography. The “cultural turn” in human geography and the “spatial turn” in communication science in the last century have influenced each other, bringing these once-distant disciplines closer and giving rise to the interdisciplinary field of “communication geography” (Adams, 2011; Wang & Zhang, 2022; Yuan, 2019). Communication geography draws on theories and methods from geography, communication studies, media studies, and cultural studies to understand the complex interplay between communication processes and spatial dynamics. Especially, the critical meaning of media is highlighted in this field. This convergence has challenged traditional notions of media, space, and how to study them (Moores, 2012; Sutko, De Souza E Silva, 2011; Wang, Tai, & Chang, 2021; Wang & Zhang, 2022). The introduction of media theory has expanded human geographers’ understanding of place and digital technology (Halegoua & Polson, 2021; Pan, 2022). For example, the relationship between media and place construction, as well as how media influences place expression, has become a focus of study (Gan, 2023; Saker & Evans, 2016; Wang & Zhang, 2022). Paul Adams, a human geographer who built upon the ideas of his mentor Yifu Tuan, has further systematized the relationship between media, space, and place. He proposed the classic “four quadrant map” of communication geography, which includes “media in spaces,” “spaces in media,” “media in places,” and “places in media” (Adams, 2011), then defined the relationship between space, place, and media as a process rather than a fixed entity.

As argued by Relph (2021), digital media is unlikely to be widely adopted if it does not enhance the place experience. A wealth of empirical literature has analyzed and discussed this phenomenon. Digital media allows for the dissemination of rich and diverse place information and content, enabling people to better understand the place they are in and cultivate a deeper sense of identity and belonging (Sutko, De Souza E Silva, 2011). For example, through social media platforms, individuals can share local life experiences, food, and attractions, strengthening the connection between people and their places and fostering a greater attachment to their surroundings (Bork-Hüffer, 2016). Additionally, digital media provides opportunities for residents to participate and engage. Through social media, online forums, and other platforms, residents can contribute to discussions and decision-making processes regarding local affairs, express their opinions and concerns, and enhance their awareness of democratic participation (Wang et al., 2021; Ye, Xu, & Zhang, 2017).

The key node: spatial media

The advancement of mobile technology and location-based services has sparked interest among researchers from various fields to rethink the relationship between geography and media (Evans & Saker, 2017; Hjorth, Pink, 2014; Leszczynski, 2015). Scholars refer to the objects created by these digital technologies as spatial media, which has prompted researchers from different disciplines to reemphasize the connection between geography and media. If the sense of place stems from an individual’s meaning, association, and memory of a specific place, then how spatial media contribute to personal experiences, emotions, and their connection to place has become a primary focus for researchers. For example, Farrelly (2015) summarizes how spatial media can enhance and prolong individuals’ interactions with place and shape their sense of place. He highlights five main ways in which spatial media engage individuals with place: by orienting and orienting individuals to their place, by anchoring individuals to their place, by defamiliarizing space to open up new interpretations, and by encouraging and extending interactions with place.

Also, McQuire (2017) explores a series of developments in New York City during the 1960s and pays attention to the changes in the spatiotemporal modes of urban communication in the context of the growing prominence of spatial media. This article offers insights into the connection between spatial/geographic media and place experiences, proposing four key characteristics of “geographic media”: ubiquity, location awareness, real-time feedback, and integration. Taking the case of Dodgeball, an early mobile social software, as an example, Humphreys (2010) suggests that mobile services promote the interactions of social spaces. This means that urban residents who are unfamiliar with each other gradually develop a sense of commonality and familiarity through sharing and exchanging information in public spaces. Saker & Evans (2016) argue that mobile social networks have transformed the way participants engage with and experience their environment.

The analysis above highlights the significant impact of spatial media on human social communication. The connection between individuals and places, as facilitated by spatial media, generates richer and more complex understandings of spaces and places. As a result, individuals’ experiences and emotions related to specific places become more intricate. This is evident not only in the media’s ability to influence people’s perceptions and understandings of places as they mediate between individuals and locations but also in the media’s capacity to create new spaces and places that evoke emotions and connections different from physical spaces.

A new twist: the metaverse

2021 has been dubbed the year of the Metaverse (first proposed in the science fiction Snow Crash), and a commonly agreed-upon description is that the Metaverse is the product of the information revolution (5G/6G), internet revolution (Web 3.0), artificial intelligence revolution, and advancements in virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), mixed reality (MR), and game engines (Dwivedi et al., 2022). These technologies have shown the potential for humans to build a holographic digital world parallel to the physical world (Dwivedi et al., 2022; Flavián, Ibáñez-Sánchez, & Orús, 2019; Tan & Liew, 2020). Unlike traditional digital spaces consumed through displays like video games and movies, the Metaverse creates the illusion of being in an entirely different environment, enabling a range of technology-mediated experiences and encounters. Researchers emphasize that the concept of the Metaverse goes beyond existing discussions of online, virtual, or digital spaces, as it mediates, blends, influences, or enhances “real” spaces (Fraser, 2023).

Relph (2007) provides important insights into virtual reality and game spaces that help us understand the Metaverse. He suggests that a sense of virtual place can develop through participation and engagement, similar to a sense of real place. This sense of virtual place involves multiple senses and emotions, mediated electronically, and varies between individuals while having community expressions. Relph’s description accurately describes the connection that millions of online game players have with their chosen virtual spaces. Unlike traditional spatial media, the Metaverse is believed to create a perceivable space (Bos, 2021; Osborne & Jones, 2022). Users can generate new interactions through avatars, and their digital selves. Through interactions with specific virtual environments and other users, new local experiences, emotional memories, and cultural identities can be formed.

Scholars also argue that digital technologies affect our experience of place in a disorienting way, as they inundate us with information and images that blur the boundaries between what is real and what is not (Dincelli & Yayla, 2022; Fraser, 2023; Gan, 2023; Osborne & Jones, 2022). This blurring of real and virtual reality exacerbates extreme views about who belongs where (Relph, 2021). In other words, the emergence of the Metaverse is reshaping our relationship with places, impacting our experience of them, and further muddling our understanding of what is “real” (Dincelli & Yayla, 2022). While the science fiction or entrepreneurial visions of Metaverse journeys may not have fully materialized yet, we can already observe the complex and increasingly apparent connections between digital and physical spaces. These connections mediate and shape our experiences and connections with places (Tan et al., 2020; Zhang & Huang, 2020). Digital links are becoming an integral part of our daily lives and our experience of places.

A conceptual framework to understand the sense of place in the digital age

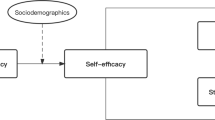

Based on the review and discussion above, we further propose an exploratory conceptual model to understand the sense of place in the digital age. This model consists of three parts: a physical sense of place, digital sense of place, and hybrid sense of place.

-

(1)

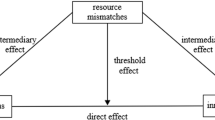

Physical sense of place: This refers to the direct interaction and connection between people and physical places. People develop a sense of place for a particular location through their activities, perceptions, and experiences in the geographical environment (Relph, 2007; Scannell & Gifford, 2010). Media technology can participate in shaping the sense of place in physical space (Farrelly, 2015), and enhance place experiences by providing navigation functions, rich geographical information, and displaying local culture, enabling people to understand and experience a place more deeply (Hjorth, Pink (2014); Humphreys, 2010; Saker & Evans, 2016). However, media technologies may also weaken the uniqueness of places by promoting homogenization through globalized and standardized content and formats (Meyrowitz (1986); Relph, 2007).

-

(2)

Digital Sense of Place: This pertains to the interaction between individuals and various media technologies that create virtual or digital spaces (Bos, 2021; Dincelli & Yayla, 2022; Dwivedi et al., 2022). Unlike the physical sense of place, the digital sense of place is related to medium technologies and online interactions. In the digital age, people can experience and perceive various places in virtual space through the internet, social media, and virtual reality (Kellerman, 2023; Liu, 2023b). These digitized places can be fictional, simulated, or representations of real-world locations, but they are presented to individuals through digital media. The sense of digital place is formed through the interaction and experience with these digital spaces, allowing individuals to develop a unique perception and cognition of them (Bork-Hüffer, 2016). For example, people can experience a fictional city or country through online games or virtual reality (Bowman et al., 2024; Jaalama et al., 2021), and they can develop a sense of place in these virtual locations by interacting with them and experiencing the environmental, cultural, and social aspects within them.

-

(3)

Hybrid sense of place: Hybrid sense of place is formed through the joint construction of the physical sense of place and the digital sense of place. These two senses of place are intertwined and influence each other (Halegoua & Polson, 2021; Relph, 2021). Media experiences and physical experiences can create parallel, competitive, or mutually reinforcing forms of place attachment and place connection. In the digital age, people can perceive and experience various forms of places through digital and physical places, resulting in a hybrid sense of place. This concept integrates the digital and physical experiences of places with the impact of social processes, emphasizing the diverse interactions and influences among humans, media, and the place.

In summary, the proposed conceptual model highlights the intertwined and interactive nature of the sense of place in the digital age (Ash et al., 2018; Liu, 2023a; Osborne & Jones, 2022). It recognizes the role of media technologies in shaping both the sense of place in physical space and the sense of digital place, and how they collectively contribute to the formation of the individual sense of place (Fig. 1).

The conceptual model consists of three parts: the physical sense of place, the digital sense of place, and hybrid sense of place, which highlights the intertwined and interactive nature of the sense of place in the digital age and recognizes the role of media technologies in shaping both the sense of place in physical space and the sense of digital place.

Application of sense of place in the digital age

Intelligent urban planning and management

Facilitating the current urban geographical development towards intelligent transformation stands as a crucial issue. A human-centered perspective, with a sense of place at its core, can serve as a guiding reference and theoretical tool for smart city planning and construction (Guo et al., 2022). The realization of the sense of place requires a symbiotic interaction between technology, society, locality, and stakeholders within a specific technological context. Addressing the pressing issue of fostering sustainable driving mechanisms for smart cities involves engaging various stakeholders in technological research and development, infrastructure construction, and governance decision-making (Fine, Liu, & Li, 2023). Additionally, exploring the application of the sense of place as a pivotal goal in smart city planning and construction involves its implementation in data-driven urban planning, intelligent transportation and mobility management, smart environmental and resource management, as well as intelligent public services and administration. These applications contribute to enhancing urban sustainability (Relph, 2021), residents’ quality of life (Erfani, 2022), and the efficiency of urban governance (Koch & Miles, 2021). Finally, the discourse on enhancing public engagement in urban planning and decision-making through digital spatial collaboration platforms and social media is a crucial direction. For instance, social media functions as a pivotal platform for the dissemination of information and public expression. It empowers cities to swiftly communicate decisions, collect real-time feedback, and engage individuals in emotional and identity connections with specific locations (Gatti & Procentese, 2021).

Community development and public space creation

The sense of place can be applied in the realm of community development and social interaction, strengthening local identity and interaction among community members through digital media and technology. Special attention is needed to understand how virtual public spaces created by media technology coexist with real-world geographical interactions, such as city green spaces, squares, and streets. Furthermore, leveraging social media and public platforms allows community members to share photos, videos, stories, and more, thereby enhancing emotional resonance and a sense of belonging to the local community. For local communities, organizing online activities, discussions, and collaborations through relevant digital media and technology to foster interaction and connections among community members, and to enhance local cohesion and public well-being, is a crucial planning issue (Hatuka, 2023). Starting from residents’ behaviors, there is a need to further examine the spatiotemporal impact of their digital technologies (such as mobile networks) on social life in public spaces (Sutko, De Souza E Silva, 2011); Thulin, Vilhelmson, & Schwanen, 2020), and how this spatiotemporal influence interacts with residents’ sense of happiness and belonging.

Tourism marketing and destination promotion

The sense of place can find application in the fields of tourism marketing and destination promotion, providing virtual tourism experiences and cultural perceptions for tourists through digital media and technology. For instance, virtual reality technology allows tourists to experience the local culture, landmarks, and more from the comfort of their homes, thus attracting their interest and sparking enthusiasm for tourism (An, Choi, & Lee, 2021). The processes and mechanisms through which the sense of place influences the willingness to travel, its impact on the perception of tourism attractions, and how different scales of digital place creation can enhance the competitiveness of attractions and destinations need further investigation (Flavián, Ibáñez-Sánchez, & Orús, 2019). Additionally, from a local branding perspective, utilizing social media platforms and virtual experience technology to integrate brands with the culture and environment of specific locations enhances brand perception among target audiences (Warnaby & Medway, 2013), thereby increasing brand value and influence. In this process, exploring whether there are differences between tourists’ perception of the digital place and the physical place (Flavián et al., 2024; Pal & Arpnikanondt, 2024), whether there is internal competition between the two senses of place, and how they collectively impact tourists’ loyalty to the destination brand, poses critical questions for destination development.

Immigration and daily life

The sense of place can be applied to the daily lives, cross-cultural communication, and understanding of immigrant communities. In a novel social environment, immigrants may confront challenges in adaptation and experience feelings of isolation. Social media and online communities present potential avenues for building social networks and support systems for immigrants (Ou & Lin, 2023). The concept of ‘sense of place’ offers a valuable lens through which to explore how digital practices facilitate interaction and connection with the local community. Investigating the outcomes of such interactions—whether they result in stronger ties with residents or exacerbate social isolation—requires further examination (Bork-Hüffer, 2016; Humphreys, 2010). Additionally, exploring whether these digital practices contribute to the emergence of new forms of identity and local attachment within daily life is an area that warrants deeper exploration (Liu, 2023; Pal & Arpnikanondt, 2024). As virtual spaces have evolved beyond their technological mediation, they have transformed into emotional spaces connecting immigrant communities with their relatives (Chan, 2008; Gan, 2023). At the same time, examining the residents’ engagement with digital media practices and experiences can provide valuable insights into how virtual spaces contribute to the reconstruction of a sense of place that may have been lost or transformed during urbanization and globalization (Zeng & Fan, 2022). By understanding how individuals connect emotionally and socially in both physical and virtual environments, researchers can explore whether these digital practices foster a renewed attachment to their immediate communities or establish connections with distant places (Dwivedi et al., 2022; Liu, 2023).

Conclusion

The increasing attention to the space and place experience in the digital era and the interweaving of the physical and digital worlds have profound implications for our understanding of the sense of place. Academic research has started to explore how digital technologies, especially spatial media and the metaverse, have transformed our experiences of place. It is important to adopt a holistic and continuous perspective to comprehend the sense of place in the digital age. The fusion of digital and physical space practices enables continuous innovation in our experiences of place, leading to the formation of a more inclusive and extensive sense of place. This involves constructing different relationships between humans and places, both in the physical and digital realms. By conceptualizing the sense of place with a digital perspective, this article aims to expand and enrich the theoretical understanding and application of this concept. It can help us better comprehend people’s daily lives and place experiences in the digital era. Furthermore, the development of the concept of the sense of place holds fruitful implications. This provides a conceptual framework for urban planning, design, and management professionals to enhance people’s experiences of places through the interaction and connection between individuals, digital technologies, and physical spaces. By leveraging these interactions, the sustainable development of places can be promoted, leading to more satisfying and meaningful experiences for individuals in their local environments.

Lastly, the spatial and locational impacts of digital technology require vigilance by researchers and managers, who need to acknowledge and identify its potential negative implications. This debate is epitomized by Lefebvre (1991), who argues that the construction of space and place is intertwined with power struggles and cultural structures. This involves examining whether spatial power is influenced by the market and bureaucratic politics driven by technology in the digital age, gradually extending into people’s daily lives (Serin & Irak, 2022). Additionally, current geographical research focuses on the potential control of space-place behaviors and experiences by digital technologies such as algorithms, virtual reality, and big data. Previous studies have highlighted the unequal distribution of spatial power caused by new technologies (Graham, 2005; Greenfield, 2013), as diverse digital technologies shape the definition of resources and spaces, assess individuals through algorithms, and enforce differential access based on perceived value (Relph, 2021). The urban reliance on digital technology in the placemaking process may result in the neglect and absence of public interests (Graham, Marvin, 2003)). In this context, the construction of the concept of a sense of place may face even more complex challenges, requiring the careful balancing of the demands of various stakeholders and the mitigation of inequalities arising from digital technology.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Change history

01 July 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03356-z

References

Adams PC (2011) A taxonomy for communication geography. Prog Hum Geogr 35(1):37–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510368451

An S, Choi Y, Lee C-K (2021) Virtual travel experience and destination marketing: effects of sense and information quality on flow and visit intention. J. Destin Mark Manag 19:100492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100492

Ash J, Kitchin R, Leszczynski A (2018) Digital turn, digital geographies? Prog Hum Geogr 42(1):25–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516664800

Bork-Hüffer T (2016) Mediated sense of place: effects of mediation and mobility on the place perception of German professionals in Singapore. N Media Soc 18(10):2155–2170. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816655611

Bos D (2021) Geography and virtual reality. Geogr Compass 15(9):e12590. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12590

Bowman ND, Vandewalle A, Daneels R et al. (2024) Animating a plausible past: perceived realism and sense of place influence entertainment of and tourism intentions from historical video games. Games Cult 19(3):286–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120231162428

Chan AHN (2008) Life in Happy Land’: using virtual space and doing motherhood in Hong Kong. Gend Place Cult 15(2):169–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/09663690701863281

Cresswell T (2004) Place: a short introduction. Blackwell, Malden

Dincelli E, Yayla A (2022) Immersive virtual reality in the age of the Metaverse: a hybrid-narrative review based on the technology affordance perspective. J. Strategic In. Syst 31(2):101717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2022.101717

Dwivedi YK, Hughes L, Baabdullah AM et al. (2022) Metaverse beyond the hype: Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. Int J Inf Manag 66:102542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2022.102542

Erfani G (2022) Reconceptualising sense of place: towards a conceptual framework for investigating individual-community-place interrelationships. J Plan Lit 37(3):452–466. https://doi.org/10.1177/08854122221081109

Evans L, Saker M (2017) Location-based social media: Space, time and identity. Springer Nature, Switzerland

Farrelly G (2015) Which way is up?: how locative media may enhance sense of place. Int J Mob Hum Comput Interact 7(3):55–66. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijmhci.2015070104

Fine G A, Liu X, Li Q (2023) Sociology of Place: Action and its public. Soc Sci front (6):202–218

Flavián C, Ibáñez-Sánchez S, Orús C (2019) The impact of virtual, augmented and mixed reality technologies on the customer experience. J Bus Res 100:547–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.10.050

Flavián C, Ibáñez-Sánchez S, Orús C et al. (2024) The dark side of the metaverse: the role of gamification in event virtualization. Int J Inf Manag 75:102726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2023.102726

Fraser E (2023) The future of digital space: Gaming, virtual reality, and metaversal thinking. Dialogues Hum Geogr. https://doi.org/10.1177/20438206231189586

Gan Y (2023) Choreographing digital love: materiality, emotionality, and morality in video-mediated communication between Chinese migrant parents and their left-behind children. J Comput-Mediat Commun. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmad006

Gatti F, Procentese F (2021) Experiencing urban spaces and social meanings through social media: unravelling the relationships between Instagram city-related use, sense of place, and sense of community. J Environ Psychol 78:101691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101691

Giddens A (1990) The consequences of modernity. Polity Press, Cambridge

Graham S (1998) The end of geography or the explosion of place? Conceptualizing space, place and information technology. Prog Hum Geogr 22(2):165–185. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913298671334137

Graham S, Marvin S (2003) Splintering urbanism: networked infrastructures, technological mobilities and the urban condition. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 93(1):246–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8306.93121

Graham SDN (2005) Software-sorted geographies. Prog Hum Geogr 29(5):562–580. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132505ph568oa

Greenfield A (2013) Against the smart city. A pamphlet by Adam Greenfield, Part I of The City is here for you to use. Do projects, New York City

Guo J, Wang J, Jiang L et al. (2022) From technocentrism to humanism: Progress and prospects of smart city research. Prog Geogr 41:488–498. https://doi.org/10.18306/dlkxjz.2022.03.011

Haefner L, Sternberg R (2020) Spatial implications of digitization: State of the field and research agenda. Geogr Compass 14(12):e12544. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12544

Halegoua G, Polson E (2021) Exploring ‘digital placemaking. Convergence 27(3):573–578. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565211014828

Harvey D (1990) Between space and time: reflections on the geographical imagination. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 80(3):418–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1990.tb00305.x

Harvey D (1995) Evaluation geographical knowledge in the eye of power: reflections on Derek Gregory’s geographical imaginations. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 85(1):160–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1995.tb01800.x

Hatuka T (2023) Public space and public rituals: engagement and protest in the digital age. Urban Stud 60(2):379–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980221089770

Hjorth L, Pink S (2014) New visualities and the digital wayfarer: reconceptualizing camera phone photography and locative media. Mob Media Commun 2(1):40–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050157913505257

Humphreys L (2010) Mobile social networks and urban public space. N Media Soc 12(5):763–778. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444809349578

Jaalama K, Fagerholm N, Julin A et al. (2021) Sense of presence and sense of place in perceiving a 3D geovisualization for communication in urban planning—differences introduced by prior familiarity with the place. Landsc Urban Plan 207:103996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103996

Jameson F (1992) Postmodernism, or the cultural logic of late capitalism. Duke University Press, New York

Kellerman A (2023) Basic human requirements of physical and virtual spaces and their implications. Mobilities 18(1):103–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2022.2045872

Kinsley S (2014) The matter of ‘virtual’ geographies. Prog Hum Geogr 38(3):364–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513506270

Koch R, Miles S (2021) Inviting the stranger in: Intimacy, digital technology and new geographies of encounter. Prog Hum Geogr 45(6):1379–1401. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132520961881

Lefebvre H (1991) The production of space. Blackwell, New Jersey

Leszczynski A (2015) Spatial media/tion. Prog Hum Geogr 39(6):729–751. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132514558443

Leszczynski A (2020) Digital methods III: the digital mundane. Prog Hum Geogr 44(6):1194–1201. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519888687

Lewicka M (2011) Place attachment: how far have we come in the last 40 years? J Environ Psychol 31(3):207–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.10.001

Liu C (2023a) The digitalisation of consumption and its geographies. Geogr Compass 17(7):e12716. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12716

Liu C (2023b) Living with touchscreens: haptic geographies of home in the digital context. Ann Am Assoc Geogr 113(1):261–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2022.2080636

Malpas J (2006) Heidegger’s topology: being, place, world. The MIT press, Cambridge

Massey D (1994) Space, place, and gender (NED-New). University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis

McQuire S (2017) Geomedia: networked cities and the future of public space. John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey

Mesch GS, Manor O (1998) Social ties, environmental perception, and local attachment. Environ Behav 30(4):504–519. https://doi.org/10.1177/001391659803000405

Meyrowitz J (1986) No sense of place: the impact of electronic media on social behavior. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Moores S (2012) Media, place and mobility. Bloomsbury Publishing, London

Osborne T, Jones P (2022) Embodied virtual geographies: linkages between bodies, spaces, and digital environments. Geogr Compass 16(6):e12648. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12648

Ou C, Lin Z (2023) Digital borders in spatial-temporal mobility: social inclusion and exclusion of Chinese migrant students in Macao. Mob Media Commun 11(3):507–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/20501579221149838

Pal D, Arpnikanondt C (2024) The sweet escape to metaverse: exploring escapism, anxiety, and virtual place attachment. Comput Hum Behav 150:107998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107998

Pan J (2022) Space as the method for media research. Nanjing Soc Sci 5:91-98

Qian J, Zhu H (2014) Chinese urban migrants’ sense of place: emotional attachment, identity formation, and place dependence in the city and community of G uangzhou. Asia Pac Viewp 55(1):81–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/apv.12039

Ramkissoon H, Mavondo FT (2015) The satisfaction–place attachment relationship: potential mediators and moderators. J Bus Res 68(12):2593–2602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.05.002

Relph E (2007) Spirit of place and sense of place in virtual realities. Techne: Res Philos Technol 10(3). https://doi.org/10.5840/techne20071039

Relph E (2021) Digital disorientation and place. Mem Stud 14(3):572–577. https://doi.org/10.1177/17506980211010694

Saker M, Evans L (2016) Everyday life and locative play: an exploration of Foursquare and playful engagements with space and place. Media Cult Soc 38(8):1169–1183. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643149

Scannell L, Gifford R (2010) Defining place attachment: a tripartite organizing framework. J Environ Psychol 30(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.09.006

Seamon D (2013) Place attachment and phenomenology: the synergistic dynamism of place. In: Manzo L, Devine-Wright P (eds). Place attachment: Advances in theory, methods and applications. Routledge, London, pp. 11–22

Serin B, Irak D (2022) Production of space from the digital front: from everyday life to the everyday politics of networked practices. Cities 130:103889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.103889

Sutko DM, De Souza E Silva A (2011) Location-aware mobile media and urban sociability. N Media Soc 13(5):807–823. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810385202

Tan S-M, Liew TW (2020) Designing embodied virtual agents as product specialists in a multi-product category e-commerce: the roles of source credibility and social presence. Int J Hum.-Comput Int 36(12):1136–1149. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2020.1722399

Taylor PJ (1999) Places, spaces and Macy’s: place–space tensions in the political geography of modernities. Prog Hum Geogr 23(1):7–26. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913299674657991

Taylor RB, Gottfredson SD, Brower S (1985) Attachment to place: discriminant validity, and impacts of disorder and diversity. Am J Commun Psychol 13(5):525–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00923265

Thulin E, Vilhelmson B, Schwanen T (2020) Absent friends? Smartphones, mediated presence, and the recoupling of online social contact in everyday life. Ann Am Assoc Geogr 110(1):166–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2019.1629868

Tuan Y-F (1977) Space and place: the perspective of experience. University of Minnesota Press, Minnesota

Wang K, Tai JC, Chang H-L (2021) Influences of place attachment and social media affordances on online brand community continuance. Inf Syst E-Bus Manag 19:459–493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10257-019-00418-7

Wang W, Zhang M (2022) Geomedia and thirdspace: the progress of research of geographies of media and communication in the West. Prog Geog 41(6):1082–1096. https://doi.org/10.18306/dlkxjz.2022.06.011

Warnaby G, Medway D (2013) What about the ‘place’ in place marketing? Mark Theory 13(3):345–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593113492992

Williams DR, Roggenbuck JW (1989) Measuring place attachment: Some preliminary results. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242236220_Measuring_Place_Attachment_Some_Preliminary Results

Ye Y, Xu P, Zhang M (2017) Social media, public discourse and civic engagement in modern China. Telemat Inf 34(3):705–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2016.05.021

Yuan Y (2019) When geographers talk about media and communication, what do they talk about? The Geography of Media and Communication by Paul Adams. Int Press 41(7):157–176

Zhang C, Huang Z (2020) Construction of ternary space interaction theoretical model of tourist destination. Geogr Res 39(2):232–242

Zeng Y, Fan T (2022) Reunderstanding "place": The formation of internet celebrity space and media sense of place. Journalism & Commun 29(11):71–89

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC): [Grant Number 42071194].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Juncheng Dai: conceptualization, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, supervision, funding acquisition. Fangyu Liu: conceptualization, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dai, J., Liu, F. Embracing the digital landscape: enriching the concept of sense of place in the digital age. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 724 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03200-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03200-4