Abstract

Achieving sustainable development is today a basic premise for all companies and governments. The 2030 Agenda has outlined an action plan focused on all areas and interest groups. Achieving economic growth and technological progress, social development, peace, justice, environmental protection, inclusion and prosperity represent the main areas to achieve social change. Furthermore, the circular economy is capable of improving the efficiency of products and resources, and can contribute to this social change, but there is a gap in the literature regarding whether the orientation of the companies in their circular economy strategy can lead to the achievement of the sustainable development goals. The objective of this study is to develop an initial circular economy-sustainable development goals (CE-SDGs) framework that considers the circular economy as the precedent and sustainable development goals as a consequence of implementing a circular economy. With respect to the methodology, the literature linking the relationship between the circular economy and sustainable development goals was reviewed first. A Structural Equation Model with the Partial Least Squares technique was also employed, analyzing two complementary models in enterprises involved in the Social Economy in the Autonomous Community of Extremadura (Spain). Regarding the results obtained, a link has been observed between professional profiles and training in people-oriented activities. The same does not occur for activities oriented toward the planet. Moreover, the existence of corporate reports that obtain data on circular activities is crucial to achieving orientation toward the sustainable development goals, for activities oriented toward both people and the planet. Finally, the results confirm that the existence of barriers and incentives determines the observed results, being aware that the lack of specialized training in human resources always has a significant incidence. Using resource and capability and dynamic capabilities theories, this study contributes with an initial framework by joining two lines of research and analyzing the CE-SDGs link in SE enterprises. Future research and empirical validations could contribute more deeply to the literature. As key recommendations, social economy managers must be committed to introducing circular economy practices to achieve people- and planet-oriented objectives, being proactive in fostering CE-SDGs frameworks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sustainability-oriented social and environmental changes imply the need to reconsider ecosystem limitations within the framework of ecological transitions and economic inequalities to promote fairer, more equitable, and democratic economic models (Villalba-Eguiluz et al., 2020; Llena-Macarulla et al., 2023; Schaltegger et al., 2023). The problem of inequality is addressed from the context of the Social Economy (SE), seeing the Circular Economy (CE) as an economic model for sustainability and the approach to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) as a mirror of this sustainable model. The natural and social focus of these enterprises leads us to consider these actions being linked to severe repercussions, not only economic but also social and environmental.

Both the CE and the SDGs are interrelated concepts that complement each other in the context of the SE. Both approaches share similar objectives in terms of promoting environmental, social and economic sustainability (García-Saravia Ortiz-de-Montellano et al., 2023). CE is intended to offer an alternative to the traditional linear economy, which is based on the extraction, manufacturing, use and disposal of resources (Bocken et al., 2014; Scarpellini, 2022). The SDGs provide a global vision of sustainable development, encompassing economic, social and environmental dimensions (Khaskheli et al., 2020; Brodny and Tutak, 2023a). SE entities can adopt circular approaches in their business operations, such as material reuse, product recycling, a sharing economy and cleaner production. They can also contribute significantly to the achievement of the SDGs by creating decent employment, reducing poverty, promoting gender equality, protecting the environment and promoting social inclusion.

More recently, the literature has highlighted the importance of these two lines of research as separate streams (Hussain et al., 2023). However, only a few studies have linked both lines or explored the importance of this connection (Merli et al., 2018; Dwivedi et al., 2022; García-Saravia Ortiz-de-Montellano et al., 2023). Joint approaches in CE and SDGs have determined the existence of gaps between the orientation toward products/materials and toward people and socioeconomic aspects, and therefore toward social change (García-Saravia Ortiz-de-Montellano et al., 2023). Other studies have linked CE and the SDGs in the technology sector as being capable of generating the corresponding social change (Dantas et al., 2021). The use of ICT tools is also missing, such as circular resources, capable of supporting circularity and generating circular value creation, as well as the identification of sustainable communities with a value-generating product-service orientation (Pollard et al., 2023). It should not be forgotten that innovation plays an important role in this transition toward a CE that promotes the development of new technologies, the creation of more efficient and sustainable production processes, and business models and practices that facilitate the reduction, reuse and recycling of resources, as well as reduction of the environmental impact (Ghisellini et al., 2016; Brodny and Tutak, 2023b). Innovation in the design of products and services will at the same time create more durable, repairable and recyclable products, facilitating the transition to a CE (Kirchherr et al., 2017). Innovation also can drive the creation of new business models that promote circularity, on-demand production and product services (Geissdoerfer et al., 2017). In terms of collaboration and co-creation, open innovation and collaboration between different actors (i.e., companies, governments, academic institutions and civil society) can boost CE by promoting the exchange of knowledge, resources, best practices and co-creation of sustainable solutions (Schiederig et al., 2012; Brodny and Tutak, 2023b). Economic and employment growth will be achieved with all of the above, important factors derived from successful innovation and in line with the 2030 Agenda (Szopik-Depczynska et al., 2018).

There are opinions focused on the need to establish policies that promote CE in all EU countries (Rodríguez-Antón et al., 2022). Recent opinions indicate that the incorporation of CE into companies will encourage a debate on the measurement of monetary value versus the value of the physical economy in the framework of sustainability (Llena-Macarulla et al., 2023), leading to economic and financial aspects being considered, as well as social variables. Furthermore, Scarpellini (2022) advocates the construction of a new conceptual framework that promotes the integration of CE with sustainability in new circular business models. Having identified possible gaps in the literature (social/economic orientation, application of ICTs, policies promoting CE, monetary value/sustainable value and creation of a conceptual framework), this research has focused on the last of them and, more precisely, with a SE-based approach, grouping together the experience of those entities capable of covering these social, economic and environmental areas, something which constitutes the novelty of the study.

The current concern is to delve into how the SE can contribute to the implementation of circular models in Extremadura, particularly within the framework of the “Green and circular economy strategy. Extremadura 2030” (Junta de Extremadura, 2022). It is possible to identify synergies and complementarities between the SE and CE models and analyze different common aspects in which SE enterprises are involved within the framework of the aforementioned strategy. A comprehensive map of CE’s role as a driver of the CE-SDGs relationship has as a result yet to be developed (García-Saravia Ortiz-de-Montellano et al., 2023). The resulting gap in the literature creates uncertainty about whether companies’ orientation in their CE strategy can affect their achievement of SDGs, namely, attaining economic growth while protecting the environment and society (Pomponi and Moncaster, 2017; Schöggl et al., 2020). The present study sought to answer the following research questions (RQ):

-

RQ1: Is it possible to achieve the sustainable development goals through involvement in circular economy and activities of this kind?

-

RQ2: Does the information on sustainability and circular economy make it possible to achieve the sustainable development goals?

-

RQ3: Do professional profiles and training in circular economy make it possible to achieve the sustainable development goals?

-

RQ4: Can the barriers and incentives to the circular economy strategy condition the achievement of sustainable development goals?

To answer these questions, this study developed a novel CE-SDGs framework, with CE as the precedent and SDGs as the consequence of joining the CE. More specifically, the proposed CE precedent model was tested to determine whether the enterprises involved in CE activities have adequately defined their professional profiles, provided sufficient training to their stakeholders, and gathered enough information on sustainability and the CE. In addition, the analysis focused on whether these organizations are oriented toward achieving SDGs and are capable of achieving them, especially in terms of people- and planet-oriented activities. These features are part of an SDG consequence model developed for this research that reflects the greater emphasis on these goals proposed by García-Saravia Ortiz-de-Montellano et al., 2023, Rodríguez-Antón et al. (2022) and Dantas et al. (2021). The present study thus aimed to develop a more holistic perspective than that offered by other authors who have concentrated on CE strategies and their contributions to achieving SDGs (i.e., SDGs 8, 12, and 13 to a greater extent and SDGs 4, 5, 10, and 16 to a lesser extent) (García-Saravia Ortiz-de-Montellano et al., 2023). The current results provide objective evidence of a relationship between the SDGs and the CE that the literature has previously failed to provide (Millar et al., 2019), thereby expanding the existing knowledge through more in-depth research (Schroeder et al., 2019).

To do this, the literature linking the relationship between CE and SDGs was reviewed first; secondly, two complementary structural equation models (SEMs), applying the partial least squares (PLS) technique, were used to analyze the models in Social Economy enterprises in the Autonomous Community of Extremadura (Spain). Using resources and capabilities and dynamic capabilities theories, this study contributes with an initial framework by joining two lines of research and analyzing the CE-SDGs link in SE enterprises.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the theoretical background for defining the hypotheses. Section 3 deals with the method applied, explaining the data analysis, samples, measurement scales, and the methodology employed. Section 4 presents the results of the empirical models, evaluates the measurement and structural models, and discusses their predictive power. Section 5 presents the discussion, and Section 6 concludes the paper with outlines, implications, limitations, and future research directions.

Literature review

Resources and capabilities theory, and dynamic capabilities theory

With respect to the theoretical framework, this study contributes to a combination of resource-based view (RBV) and dynamic capabilities (DC) theories. According to the RBV, companies can be viewed as an integrated set of heterogeneously distributed resources and capabilities (R&C) incorporated into their strategy, generating social and environmental impacts (Sassanelli et al., 2020; Abeysekera, 2022). These R&C are valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable assets that can obtain competitive advantage and contribute to sustainable value creation (Hitt et al., 2020; Asiaei et al., 2020; Caby et al., 2020). These intangible assets affect corporate performance (Asiaei et al., 2020; Asiaei et al., 2021), and companies must integrate and accumulate critical assets to create value-creating potential. Once the performance has been evaluated, the efficiency and effectiveness of actions can be quantified (Kamble and Gunasekaran, 2020), determining the possible benefits of the strategic resources used (Asiaei and Jusoh, 2017). Companies can support the integration and engagement of sustainability through their supply chains in particular and their different activities in general, implementing a business strategy that provides corporate performance through efficient resources (Gallardo-Vázquez and Valdez Juárez, 2022). The vision is that by implementing CE activities in companies, the resources and capacities applied in their development correspond to intangible assets and can influence organizational performance and generate an impact that results in the achievement of the SDGs.

The dynamic capabilities theory has its roots in resource-based theory, with this new approach seeking to take companies to a higher level of responsibility with a dual-benefit approach (i.e., company-society) (Gallardo-Vázquez and Valdez Juárez, 2022). In addition, this theory includes the detection and exploitation of opportunities in potential markets, helping organizations execute and apply internal and external resources to achieve sustainable results (Kachouie et al., 2018; Belhadi et al., 2022). Strategic and dynamic capabilities are pillars that can sustain an organization’s growth, such as CE activities and knowledge generated to facilitate the development and execution of strategic plans (Ledesma-Chaves et al., 2020; Bitencourt et al., 2020).

Social economy enterprises and circular economy: Precedent

The SE comprises a set of economic and business activities carried out by enterprises in the private sphere that pursue general economic or social interests, or both (Law 5/2011, of March 29, on Social Economy). Its guiding principles are as follows: (i) Prioritizing people and the social purpose over profit, promoting autonomous, transparent, democratic, and participatory management; (ii) applying the results obtained to the corporate purpose of the entity; and (iii) promoting internal solidarity with society, contributing to local development, gender equality opportunities, social cohesion, the integration of people at risk of social exclusion, the generation of stable employment and quality, the reconciliation of personal, family, and work life, and sustainability in all its aspects.

The CE has in addition been proposed by different fields as an alternative to linear models based on extraction, production, use, and disposal, forecasting an adaptation of the current models to an economy of zero emissions and waste (Schaltegger et al., 2023; Llena-Macarulla et al., 2023; Ahmad et al., 2023). This includes both new business models based on the rental or leasing of services (Scarpellini, 2022), as well as the closing of material loops in different activities and sectors in the CE framework, and improving the efficiency of products in both the manufacturing and use phases (Benito-Bentué et al., 2022; Marco-Fondevila et al., 2021; Matos et al., 2023). This model of closing material loops is being introduced both at a macroeconomic level and in companies and organizations that are increasingly adopting CE principles in the production and provision of services (Aranda-Usón et al., 2020), and it is equally applicable to SE enterprises (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD, 2022).

With a holistic focus on the conservation of resources and an orientation toward obtaining corporate performance, this study addresses CE, which has the potential to bring economic activities back within environmental boundaries (Garcia-Saravia Ortiz-de-Montellano and van der Meer, 2022; Scarpellini, 2022; Ahmad et al., 2023; Skare et al., 2024). The CE seeks to convert waste into new resources and make innovative changes in current production systems to encourage regeneration within a sustainable development framework (Chaves Ávila and Monzón Campos, 2018; Llena-Macarulla et al., 2023). Consumption and production cycles can in this way become more sustainable while promoting economic prosperity and social equity (Kirchherr et al., 2017). Concurrently, the CE is expected to contribute to ensuring development that respects the environmental limits of natural resource exploitation, thereby enhancing environmental quality (Marco-Fondevila et al., 2018). This approach is oriented toward social, environmental, and technological change, which can come together within the CE.

In Spain, the First Circular Economy Action Plan 2021–2023 (Government of Spain, 2021) contemplates the active participation of SE enterprises in different areas of the CE, and it is worth mentioning the recycling of products, the market for second-hand goods (with the transfer of municipal spaces to SE associations and enterprises), the reuse of products within the social and solidarity economy (directly or indirectly through their prior preparation), or the promotion of responsible consumption and training activities. The Plan also recognizes that the SE has been a pioneer in the creation of employment linked to the CE and that its potential will be strengthened by the mutual benefits that support ecological transition and the reinforcement of social inclusion. There is a dynamic capacity for complementary resources and activities that determines sustainable development.

SE enterprises have pioneered the expansion of CE practices in the European Union. An analysis of complementarities between CE and SE has been undertaken in recent years at local and regional levels (FEMP, 2019; Villalba-Eguiluz et al., 2020), in the European Union (EU) (European Economic and Social Committee, 2016), internationally (OECD, 2022), and in Spain (Government of Spain, 2021). Among the most important aspects common to the SE and CE are those related to the principles of equity (which distinguishes between SE enterprises and private sector enterprises based on competitive advantage objectives) and democratic and collaborative governance, favoring a prioritization of the reduction/reuse of materials more typical of the CE in a framework of common good advocated by the SE and of undoubted interest in accountability practices (Pesci et al., 2020). However, the contribution of SE to CE has not yet been fully developed and requires further study for its definition and, in particular, for its measurement to define strategies and action plans that directly link these two fields.

Within this framework, the CE and SE have several aspects in common, as they are models based on sustainable development and people (European Economic and Social Committee, 2016). The CE primarily pursues the creation and retention of environmental and economic values, and there is a clear complementarity between the CE and SE models. SE and circular models can in particular reinforce the positive social impact of circular activities and accelerate the transition to a CE that requires creative and innovative capacity, particularly at a local level, in order to close material loops in the CE through integrated business models focused on proximity to the place of use of the product or service (Villalba-Eguiluz et al., 2020; Ahmad et al., 2023; Matos et al., 2023; Skare et al., 2024). The possibility of merging approaches based on SE, social innovation, and social entrepreneurship with the ecological potential of CE for the social good has therefore been explored (Soufani et al., 2018).

In the EU, the synergies of the SE with the CE arise from the fact that these enterprises carry out waste reuse and recycling processes in addition to being seen in sectors such as energy and agriculture (European Economic and Social Committee, 2016). The European Commission, in its EU action plan for CE, recognized that SE companies can make a key contribution to CE (European Commission, 2015), and the link between CE and SE can be viewed in the three pillars of sustainable development: Environmental, economic and social development, the latter being explored less (Scarpellini, 2022).

The common guidelines between the SE and CE models focus on collaborative and symbiotic governance measures that allow the introduction of business models in these enterprises. Among the points both models have in common, the following stand out (Villalba-Eguiluz et al., 2020; Dantas et al., 2021; Pollard et al., 2023; Brodny and Tutak, 2023b): (i) The principle of cooperation and collaboration in the face of free market competition. (ii) The need for regional and industry networks, prioritizing aspects of a local or regional scope. (iii) The centrality of work in both models with labor-intensive processes (such as repair, remanufacturing or recycling in the case of CE). (iv) The systemic transition proposed by the institutions based on the externalities generated. (v) The changes in market paradigms through servitization (typical of CE) and the collaborative economy (intrinsic to SE) that come together in both models.

Social economy enterprises and sustainable development goals: Consequence

SE enterprises have pioneered the expansion of sustainable social development (Khaskheli et al., 2020). SE supposes a complementary concept of business efficiency and the social responsibility of private institutions, giving rise to a rational and social reconciliation of private action that makes them ideal for contributing to the achievement of the SDGs and their objectives, as well as being undertaken according to the SDGs established (Mozas, 2019; Flores, 2021; García-Saravia Ortiz-de-Montellano et al., 2023; Allen et al., 2024). This situation makes these enterprises fundamental agents for the sustainable development of current societies, helping them to develop social innovation processes that implement sustainable actions oriented toward the triple bottom line, i.e., economic, social, and environmental benefits (Hoang et al., 2021; Henry et al., 2019).

Mention should be made of the United Nations General Assembly (2015) resolution in which a set of global objectives was approved and the SDGs were included in the 2030 Agenda, aiming to eradicate or at least alleviate some structural problems of various kinds that the planet is currently facing, and proposing a time horizon that extends to 2030 (Calabrese et al., 2021). These SDGs comprise an action plan that seeks to benefit people and the planet, as well as increasing prosperity to strengthen universal peace based on a broader concept of freedom. The goals also promote the eradication of poverty worldwide and the achievement of sustainable production and consumption (Khaskheli et al., 2020; Brodny and Tutak, 2023a).

The literature contains many studies that have focused on the achievement of different SDGs. More specifically, research has concentrated on SDG 1 (i.e., end of poverty), seeking to foster inclusive development by analyzing quality of growth, inequality, and poverty in developing countries (Asongu and Odhiambo, 2019). Other researchers have explored SDG 7 (i.e., affordable and clean energy) by evaluating the positive impact of foreign investment used to complete projects, but taking into account possible adverse environmental consequences for recipient countries (Schroeder et al., 2019; Aust and Isabel, 2020; D’Orazio and Löwenstein, 2020; Xiao et al., 2024). Studies of SDG 8 (i.e., decent work and economic growth) have analyzed participation and cooperation between governments, financial institutions, companies, and consumers, as well as examining the evolution of green finance, improvements in innovation capacity, and green economy transformation (John et al., 2019; Schroeder et al., 2019; Cui et al., 2020; Szopik-Depczynska et al., 2018).

Research on SDG 10 (i.e., reduction of inequalities) has found that sustainable banking plays an important role by generating two-way trust in loan recipients’ ability to overcome institutional limitations, especially in countries with a weak rule of law (Úbeda et al., 2022). Research has further focused on SDG 11 (i.e., sustainable cities and communities), highlighting the positive effect of urban green areas while identifying areas with a higher potential for improvement (Lorenzo-Sáez et al., 2021). Finally, researchers have examined specific aspects of SDG 12 (i.e., responsible consumption and production through the appropriate use of resources and energy), e.g., waste minimization and increased investment in optimizing operating systems (Rodríguez-Antón et al., 2019; Schroeder et al., 2019; Dantas et al., 2021) and of SDG 13 (i.e., climate action).

In the present research context, some studies have linked SE enterprises with the achievement and development of SDGs and the 2030 Agenda and have explored these organizations’ strategies (Silva and Bucheli, 2019; Cis, 2020; Calabrese et al., 2021). It should be noted that the SDGs with the most important place in the SE model are SDG 1. End of poverty, SDG 7. Affordable and clean energy, SDG 10. Reduction of inequalities and SDG 13. Climate action. Conversely, Canales Gutiérrez (2022) highlights compliance with SDG 8. Decent work and economic growth, SDG 11. Sustainable cities and communities, and SDG 12. Responsible consumption and production.

Social enterprises are a source of regional development (Mozas and Bernal, 2006; Li and Espinach, 2020), particularly in depressed or rural areas (Ruíz, 2012; Flores, 2021), which allows us to affirm that they are effective tools for achieving the goals associated with SDG 1. End of poverty. These enterprises seek to end poverty as a mechanism that generates entrepreneurship in areas where entrepreneurship and gross capital formation are low (Chaves and Pérez, 2012; Khaskheli et al., 2020; Blind and Heb, 2023).

Concerning the link between social enterprises and SDG 8. Decent work and economic growth, we mentioned that by establishing regulations, social enterprises, particularly employment companies, originated in response to the 1970 crisis in order to maintain and guarantee employment. This is carried out by promoting associations between workers to create a joint company in which decision-making is carried out through a model that is as associative and democratic as possible (Rodríguez-Antón et al., 2019; Schroeder et al., 2019; Dantas et al., 2021). Cooperatives also stand out as a means to comply with SDG 8 (Cermelli and Llamosas Trápaga, 2021). In these types of enterprises, particularly in cooperatives and worker-owned companies, economic growth is linked to the capacity to generate employment associated with cooperative entrepreneurship among workers (Generelo, 2016; Melián and Campos, 2010; Kolade et al., 2022). Currently, business models frequently pursue twin objectives: The environmental improvement of society and job creation, often for people at risk of exclusion. Thus, the participation of SE enterprises in SDGs and CE-related activities implies concern for local community social issues that gain in relevance, as well as the involvement of governments in the development of green financial and regulatory incentives to support the CE-SDGs framework (Mies and Gold, 2021).

Analyses of social enterprises’ impact on the achievement of SDG 10 (i.e., Reduction of inequalities) have shown that these organizations generate higher quality employment, which directly reduces inequalities by tackling the structures that produce gender-related problems, discrimination, exclusion, and diversity (Calderón Milán and Calderón Milán, 2012; Blind and Heb, 2023). In other words, SE enterprises adopt ways of understanding production relations that consider their ability to sustain SD, thereby constituting an effective tool to achieve SDGs. SDG 12 (i.e., responsible consumption and production) is in turn related to an adequate redistribution of resources so that these organizations can ensure economic growth that provides benefits—as defined by the triple bottom line model—and promotes socially responsible behaviors (Huang et al., 2023; Shah and Shah, 2023).

Involvement in circular activities

SE enterprises play an important role in the transition process from a linear to a circular economy because their activities in terms of sustainability entail greater value for society and other interest groups (Stratan, 2017). It is therefore necessary for CE to be included in the strategic policies of these enterprises and for their managers to be familiar with and motivated by the necessary actions to improve the level to which material loops are closed (Matos et al., 2023). The CE concept has therefore emerged as an important way for individuals, enterprises, and society to be more sustainable (Brown and Bajada, 2018; Cui and Zhang, 2018; Scarpellini, 2022). The CE transforms society into a more sustainable model (Dey et al., 2020). It is based on three principles: (i) Eliminate waste and pollution, (ii) keep products and materials in use, and (iii) regenerate natural systems (Fortunati et al., 2020), which would produce maximum economic and social value (Scarpellini, 2022). The CE model defines a regenerative system by substituting the traditional take-make-dispose economy (Ahmad et al., 2023).

CE activities contribute to the efficient use of resources, valuing the use of theories that support this study. Thus, organizations can optimize their costs and generate more benefits in a triple sense, i.e., economic, social, and environmental. This new CE model deals with the sustainable integration of economic activities and environmental well-being (Scarpellini et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2019; Scarpellini, 2022).

In Europe, SE is considered sensitive to the social implications of climate change and active participation in actions related to social and environmental matters for environmental improvement (OECD, 2022). The SE has been a pioneer in the implementation of CE activities from a practical and technological perspective, being aimed at the recovery and recycling of waste, renewable energy, and agriculture (Marco-Fondevila et al., 2021; Llena-Macarulla et al., 2023).

These enterprises have in addition been proactive in adapting their services and products to the CE and, particularly, to collaborative economy environments in which new information technologies allow new models with respect to collaborative consumption, work, production, financing, and so on (Chaves Ávila and Monzón Campos, 2018). Thus, SE favors collaboration between value chains and specific mechanisms to manage collaborative environments, thus expanding the potential for social innovation in circular and sharing economy models (OECD, 2022).

Attention to training and technology is a basic aspect of CE implementation. Digitization and the need to adapt processes to CE guidelines are specified as necessary conditions for companies to address SD (Pés, 2019). The establishment of norms and processes that allow a fair transition from the current labor market to the circular model, bearing in mind the sustainable use of natural resources, must be addressed by institutions (Pés, 2019). New processes and procedures must be evaluated and certified to ensure adequate quality management (Rodríguez Cortés, 2021) and efficiency control in compliance with social and environmental purposes.

Involvement in circular activities is significant in the management of human resources, given the need to define adequate professional profiles, adapt to the new requirements of the circular model, and provide continuous training in companies. However, there is evidence that companies that incorporate sustainability and circularity into their personnel management obtain important economic and social results.

Based on the existing literature, the present study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1: Involvement in circular economy directly and positively impacts professional profiles and training.

H2: Involvement in circular economy directly and positively impacts information on sustainability and circular economy.

Professional profiles and training, and sustainable development goals

From a social CE perspective, some studies have analyzed the skills of workers and the training for closing material loops and how specific training allows the development of these skills (Scarpellini, 2021), increasing labor productivity and employment management of the most innovative technologies for CE (Marín-Vinuesa et al., 2023; Portillo-Tarragona et al., 2022) and, in general, in terms of proactivity for sustainability (Delgado Ferraz and Gallardo-Vázquez, 2016). Khan et al. (2020) highlighted the importance of recruiting employees to CE objectives, and Marrucci et al. (2021) demonstrated the contribution of human resource management to the CE framework. Thus, we can argue that the social performance of CE related to employment also includes the development of employee skills and specific training (Scarpellini, 2022).

Training in the management of ISO 9001 standards implies integration into business strategies and compliance with strategic objectives, leading to the SDGs. In this regard, this framework can constitute an ideal environment for improving women’s employment and reducing inequality in labor and social environments (Blázquez Agudo, 2018). More specifically, the definition of adequate professional profiles and training are relevant in aspects such as female entrepreneurship (García Mandaloniz, 2018), work-life balance (Nieto, 2018), age and disability seen from a gender perspective (Blázquez Agudo, 2018), and decent work (Alameda, 2018).

The achievement of SDG 8. Decent work and economic growth is the greatest corporate concern in 23 Colombian firms ahead of climate action or other types of items included in the SDGs, being, in a way, an indicator of inequality (Pérez et al., 2020). Similarly, in labor relations, aspects of labor inclusion stand out, particularly, the execution of policies and implementation of measures by companies that mitigate the inequalities suffered by people at risk of social exclusion.

The achievement of SDG 10. Reduction of inequalities is also highlighted, including gender studies, and evidencing unequal access to work and unequal social and employment positions of women compared to men (Correa and Quintero, 2021; Baeza and Rúa, 2020; Verdiales, 2020). The difficulties of labor inclusion among immigrant groups (Canelón and Almansa, 2018) should also be highlighted, observing the opportunities and challenges that the SDGs pose to companies in terms of migration. Attention should in addition be paid to people with disabilities, whose approach to business strategy from the perspective of SDGs is also possible and affordable (Mercado et al., 2020; Riaño, 2019).

Based on the existing literature, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H3: Professional profiles and training have a direct and positive effect on people-oriented activities.

H4: Professional profiles and training have a direct and positive effect on planet-oriented activities.

Information on sustainability and circular economy and sustainable development goals

Sustainability information determines changes in non-financial information and accounting management and control (Llena-Macarulla et al., 2023; Scarpellini et al., 2020; Barnabè and Nazir, 2021). In the CE context, sustainability information indicators are used primarily in the framework of environmental management accounting to measure material and waste flows (Marín-Vinuesa et al., 2023; Portillo-Tarragona et al., 2022; Llena-Macarulla et al., 2023), manage responsibilities, or define the accounting capacities of companies for the introduction of circular models (Scarpellini et al., 2020). However, organizations rarely use specific indicators to report on CE (Benito-Bentué et al., 2022; Rabasedas and Moneva Abadía, 2021), even in the case of nonprofit enterprises such as those related to the SE (López-Arceiz et al., 2021).

Although information transparency has been used as a measure of social performance, it is necessary to implement integrated measurement systems designed for different interest groups capable of reporting the investments and impacts of circular activities (Marco-Fondevila et al., 2021; Moneva et al., 2023).

Analysis of SE enterprises in Extremadura’s perception of communication and dissemination practices in the CE highlights the need to incorporate environmental accounting as a tool for control and registration of the sustainable activities carried out by the company, which is useful in addition to evaluating these activities from the perspective of corporate social responsibility and the contribution of corporations to sustainable development. Some authors understand accounting as a system that must not only provide financial information, but also begin to incorporate indicators in aspects such as the contamination index for activities carried out or the replacement rates of resources used in the production process. This is the only way in which the accounting information system can become a complete and efficient tool for decision-making, particularly with regard to those decisions that affect the socially responsible behavior that the company intends to maintain over time. This aspect is particularly important with regard to enterprises that are part of the SE, whose nature and purposes require them to have environmental and social information mechanisms that serve business strategy and tactics, as well as for the evaluation of their processes and social and environmental procedures (Avellán, 2019; Muñoz, 2021).

When the 2030 Agenda is the focus of attention for the actions of several companies, the lack of consensus is criticized when proposing a universal model for presenting corporate reports based on SDGs. This leads to a lack of adequate communication at a corporate level (Goenaga, 2018). Given the concern in achieving an orientation toward the SDGs, some productive sectors have incorporated items from the 2030 Agenda into their management reports, checking those that may be functional and generate competitive advantages.

Based on the literature, the present study proposes the following hypotheses:

H5: Information on sustainability and circular economy has a direct and positive impact on people-oriented activities.

H6: Information on sustainability and circular economy has a direct and positive impact on planet-oriented activities.

Barriers and incentives and observed results on sustainable development goals achieved

With respect to the barriers that hinder the implementation of CE in SE enterprises, an increase in small-scale local experiences in Spain has revealed the lack of specialized training in human resources as a major barrier (Portillo-Tarragona et al., 2017; Scarpellini et al., 2020). It would therefore be interesting to analyze the perception of the need for specific training on the part of SE enterprises in order to propose aid for training plans or any other cross-cutting measures that improve the training of workers for CE-related activities.

However, several previous studies have highlighted the fact that the lack of financial resources hinders the implementation of CE in different types of investments (Aranda-Usón et al., 2018; Aranda-Usón et al., 2019) and that, therefore, specific public funding can favor its implementation in different organizations (Llera-Sastresa et al., 2020; Scarpellini et al., 2021).

Based on the existing research, the following hypothesis can be formulated:

H7: The greater the influence of barriers and incentives, the greater the observed results and benefits.

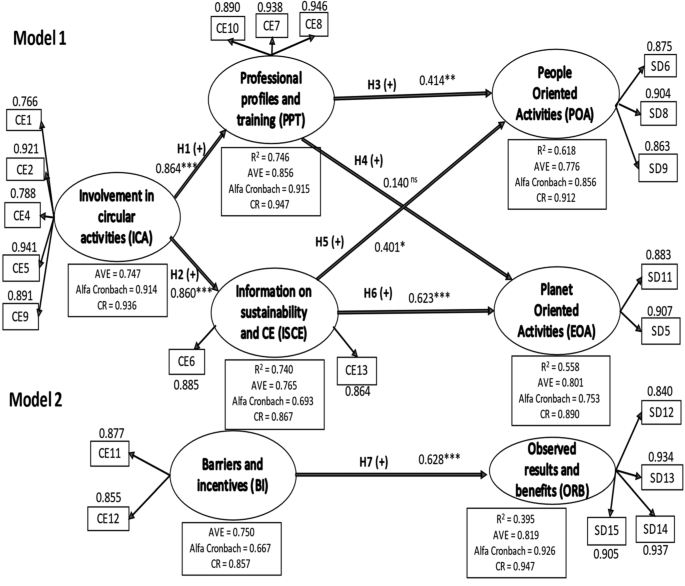

Figure 1 depicts the hypothesized relationships tested in this study. This indicates that the first two hypotheses integrate CE precedent model 1, which leads to the fulfillment of the following four hypotheses oriented toward SDG consequence model 1. At the bottom, CE precedent model 2 is observed with only one hypothesis toward the achievement of results from SGD consequence model 2.

Model 1 has been defined based on five constructs (ICA, PPT, ISCE, POA and ORB). This model is made up of six hypotheses, stated in a positive sense. Model 2 has been defined from two constructs (BI and PRB), and is made up of a hypothesis also stated in a positive sense. The left part of both models represents the CE antecedent, while the right part refers to SDG consequence. Source: authors.

Methods

Sample and data collection

This study focuses on SE enterprises in Extremadura (southwest Spain). The Autonomous Community released the White Paper on the Social Economy at the end of 2022 to provide a view of the state-of-the-art of these enterprises in the region. It did at the same time send these enterprises an opinion questionnaire on SDGs and CE. At a time when social change is being proclaimed internationally, known as the “Momentum of the Social Economy,” it is necessary to know the potential of these enterprise and to be able to forecast how the effort they carry out is materialized. The International Labor Organization (ILO) and Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) published recommendations on SE in May and June 2022, and the United Nations (UN) is working on a resolution on SE and SDGs.

A structured questionnaire was designed comprising two sections: (1) Characteristics of the entity: Name, type of SE entity, sector to which it belongs, and size of the entity; and (2) A set of actions on issues related to SDGs and CE to assess the level of knowledge of the entity, based on the perception of the person who answers the questionnaire. It is a Likert-type scale with ratings from 1 to 7 (1: knowledge is low; 7: knowledge is very high). The questionnaire was sent out by email at two specific times, with an interval of one week between each one, over 15 days in November 2022.

This study addresses a large group of SE enterprises, covering a complete typology. Given the great variety enterprise families that make up the SE, the degree to which each of them represents the existing total of social enterprises was also studied. Once the percentage presence of each family was assessed, the corresponding number was extracted from the total number of social enterprises existing in each family. The target universe was therefore made up of 250 social economy enterprises who received the emails. The final sample consisted of 90 enterprises, yielding a response rate of 36% (Table 1), the percentage of enterprises that agreed to answer the questionnaire.

Statistical analysis of the data (see Table 2) revealed that the largest number of enterprises participating in the study corresponded to cooperative societies (48.9% of the sample), followed by associations (21.1%), special employment centers (11.1%), and employment companies (8.9%). Participation was lower for foundations (5.6%), agricultural processing companies (3.3%), and special enterprises (1.1%). Companies related to social inclusion, mutual societies or insurance companies did not participate in the study.

With respect to sectors, 52.2% of enterprises belong to the tertiary and service sector, followed by 25.6% from the primary sector and 22.2% from the secondary sector.

Finally, with regard to the size of the entity, measured by the number of employees, the highest percentage corresponds to enterprises with less than five workers (51.1%). Enterprises with 6–10 workers and 11–25 workers had the same weight in the sample (13.3%). Next came enterprises with 26–50 workers and 51–100 workers, each with a weight of 7.8%. The remaining 6.7% were enterprises with more than 100 workers.

Data analysis

The research model was analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). This method has been chosen due to its fit with the conceptual model and what is intended to be obtained from the analysis. It is a statistical technique used primarily in social sciences and business research to analyze structural relationships between variables. It is particularly useful when the research model is complex, or when data may not meet the assumptions of other structural equation modeling (SEM) techniques like covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM). Overall, PLS-SEM provides researchers with a flexible and powerful tool for analyzing complex relationships between variables, making it particularly suitable for exploratory research or studies with small sample sizes. However, it is essential to consider the specific requirements of the research context and the assumptions underlying the PLS-SEM technique when applying it in practice.

This statistical technique was applied with the help of SmartPLS 4 software (Ringle et al., 2015). The model is based on a prediction-oriented econometric perspective and focuses on latent or unobserved variables inferred from indicators (Chin, 1998a). These are second-generation multivariate models that allow two things: Firstly, the incorporation of abstract constructs that are not directly observable, specifying a measurement model. The second use is to determine the degree to which the measurable variables describe the latent variables, and the third is to incorporate the relationships between multiple predictor variables and the criteria. This technique is appropriate for exploratory research, does not require data normality and uses small sample sizes (Hair et al., 2014).

PLS models combine and test hypotheses emanating from prior theoretical knowledge based on empirically collected data (Chin, 1998b). The analysis was carried out in three stages: First, the measurement model was evaluated (reliability and validity of the measurement scales), evaluating the strength and significance of the relationships between constructs (path coefficients); second, the structural model was evaluated, observing that the relationships between the constructs confirmed the completeness of the hypotheses, and which involves examining the significance of the path and assessing their effect sizes; and third, the goodness of fit of the model and its predictive capacity were analyzed.

Measurement scales

The CE precedent

The constructs related to CE precedents in the first model (Model 1) include: Involvement in circular activities (ICA), professional profiles and training (PPT), and information on sustainability and CE (ISCE). In the second model (Model 2), barriers and incentives (BI) were introduced. The scales focusing on these constructs were based on Aranda-Usón et al. (2020), Scarpellini (2022), and Scarpellini et al. (2019). The ICA, PPT, and ISCE were measured using two items, while the BI used four items. All these are composite lower-order constructs (Mode A).

Sustainable Development Goal consequence

Constructs related to SDG consequences in the first model (Model 1) are as follows: People-oriented activities (POA) and Planet-oriented activities (EOA). The observed results and benefits (ORB) were introduced in the second model (Model 2). The scales focusing on these two constructs were based on Ogunmakinde et al. (2022), Elavarasan et al. (2022), and the Global Indicator Framework for Sustainable Development Goals (UN, 2022). The POA used three items, the EOA used two items, and the ORB used four items. All these are composite lower-order constructs (Mode A).

Results

Evaluation of the measurement model

The previous conceptual model (Fig. 1) developed by the researchers will describe the relationships between the variables, specifying hypotheses about how the different constructs are related to each other. In PLS-SEM, constructs are measured using observed indicators or variables. These indicators should be reliable and valid measures of the underlying constructs. The measurement model specifies how these indicators are related to their respective constructs. PLS-SEM proceeds to estimate the model and thereby estimates the parameters of both the measurement model (reflective or formative) and the structural model simultaneously. This estimation process involves iteratively adjusting the model to minimize the difference between observed data and the model’s predictions.

It is necessary to assess the reliability of the measurement instrument. Each item’s factor loading (λ) did therefore evaluate the individual reliability of each item (λ > 0.707). This condition indicates that the shared variance between an item and its construct is greater than the error variance (e.g., Chin and Dibbern, 2010; Hair et al., 2014). All item loading values obtained in the present research range from 0.766 to 0.946 in Model 1, and from 0.840 to 0.937 in Model 2, exceeding the recommended minimum value (see Tables 3 and 4). In addition, because the constructs represent Composite LOC Mode A, any indicators that define them must be correlated, and the correlation weights are analyzed (Rigdon, 2016; Henseler, 2017).

In addition, the internal consistency of each construct was checked by reviewing Cronbach’s alpha (CA) and the factor’s composite reliability (CR). This indicated how well a set of items measured a latent variable. The recommended minimum value of Cronbach’s alpha is above 0.7, which is complied with in the current study, except for two values (Model 1 and Model 2) that are very close to the recommended minimum value (Hair et al., 2006). From Tables 3 and 4, the CA values fall between 0.693 and 0.915 in Model 1; 0.667 and 0.926 in Model 2. In Model 1, the values were 0.693 for ISCE, 0.753 for EOA, 0.856 for POA, 0.914 for ICA, and 0.915 for PPT. In Model 2, the values were 0.667 for BI, and 0.926 for ORB. These results confirm the scales’ high reliability (see Tables 3 and 4).

The factor composite reliability (CR) analysis also produced acceptable values, ranging from 0.867 to 0.947 in Model 1 and from 0.857 to 0.947 in Model 2. A value of 0.867 was obtained for ISCE, 0.890 for EOA, 0.912 for POA, 0.936 for ICA, and 0.947 for PPT in Model 1, and 0.857 for BI and 0.947 for ORB in Model 2. Nunnally (1978) and Vandenberg and Lance (2000) recommend scores above 0.80 for advanced research (see Tables 3 and 4). The construct’s internal consistency was therefore confirmed.

The convergent and discriminant validity of the constructs was checked to assess the validity of the model. Convergent validity was analyzed by calculating the average variance extracted (AVE) (Fornell and Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2011). The AVE values range from 0.747 to 0.856 in Model 1 and 0.750 to 0.819 in Model 2, higher than 0.5 (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, and Tatham, 2010). More specifically, a value of 0.747 was obtained for ICA, 0.765 for ISCE, 0.776 for POA, 0.801 for EOA, and 0.856 for PPT in Model 1, and 0.750 for BI and 0.819 for ORB in Model 2. These results are satisfactory because the conditions of the recommended minimum are met; the convergent validity of the model constructs can therefore be considered satisfactory.

Finally, the discriminant validity of the constructs revealed the existence of differences between each construct and its items with respect to other constructs and their items. According to the Fornell and Larcker (1981) criterion, the square root of the AVE for each construct must be greater than the inter-construct correlations of the model. The values—shown diagonally and in bold in Table 5—for vertical and horizontal AVE are below the correlations between constructs (Henseler et al., 2015; Roldán and Sánchez-Franco, 2012) (i.e., Model 1: 0.895 > 0.695, 0.744, 0.756, and 0.676; 0.864 > 0.695, 0.860, 0.783, and 0.864; 0.875 > 0.744, 0.860, 0.758, and 0.860; 0.881 > 0.756, 0.783, 0.758, and 0.759; 0.925 > 0.676, 0.864, 0.860, and 0.759; Model 2: 0.866 > 0.628; 0.905 > 0.628). These results confirmed the discriminant validity of the model according to Fornell and Larcker’s criteria.

Discriminant validity was calculated based on the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) (see Table 5). Henseler et al. (2015) and Roldán and Sánchez-Franco (2012) indicated that this ratio should be below 0.90. Not all the values included in Table 5 meet the HTMT criteria. However, they were very close to the recommended minimum and were valid. It can therefore be confirmed that all constructs in this study met the established discriminant validity criteria.

Evaluation of the structural model

In this stage, researchers validate the model by testing its generalizability on independent datasets or through cross-validation techniques. The weight and magnitude of the relationships between the model variables obtained from the research hypotheses were evaluated using a structural model (Wright et al., 2012). The predictor variables’ contribution to the explained variance of the endogenous variables was evaluated by analyzing the path coefficients (β) or standardized regression weights obtained. These weights need to present values exceeding 0.2 but ideally greater than 0.3 (Chin, 1998a). However, in empirical research, one variable has a predictive effect on another when the first variable explains at least 1.5% of the variance in the endogenous variables (Falk and Miller, 1992) (see Table 6). In the present study, in Model 1, the β values were 0.864***, 0.860***, 0.414**, 0.401*, 0.623***, and 0.140, with only one value not meeting Chin’s (1998a) recommended minimum (i.e., H4). Moreover, in Model 2, the β value was 0.628***. If Falk and Miller’s (1992) criteria are applied, the explained variance (R2) can be observed as varying between 55.8% for EOA, 74% for ISCE, 61.8% for POA, and 74.6% for PPT in Model 1 and 0.395 for ORB in Model 2; all R2 values exceeded the recommended minimum of 1.5% (see Tables 8 and 9).

To verify whether empirical support exists for the set of hypotheses formulated, the path coefficients’ significance was analyzed and if β coefficients were significant, the hypotheses were supported. Similarly, a nonparametric resampling technique (i.e., a bootstrapping procedure) was applied with 5,000 subsamples and a Student’s t-distribution based on a tail with n - 1 degrees of freedom, where n is the number of subsamples (Chin, 1998b; Hair et al., 2011). This procedure provided both the standard error and values of the Student’s t-statistic for the parameters. The present test was conducted with the sample data and produced satisfactory results. We can affirm that the model is reliable, although confirmation of all the hypotheses posited in this study would have been preferable.

Table 6 reveals that all but one of the structural paths proposed in the model are significant, albeit at different levels of significance. Thus, five of the six hypotheses in Model 1 are supported by the results. In addition, one hypothesis of Model 2 is accepted. Despite the lack of a significant direct link between PPT and EOA (i.e., a β value of 0.140 and a p-value of 0.423), the other six relationships were validated by the data. For H1, H2, H3, H5, H6, and H7, the variables’ significant positive effects were confirmed with p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001.

Finally, the bootstrapping procedure was used to analyze the percentile confidence intervals, (CI) as well as bias correction. These values exceed zero, as recommended by Chin (1998b), except for H4, which was not accepted (see Table 7).

The models’ nomogram shows the signs, magnitudes, significance, and R2 values of the path coefficients for the dependent variables (Fig. 2).

Predictive power of the model

PLS-SEM focuses more on the predictive power of the model and is often preferred when the main focus is on a prediction of dependent variables rather than an explanation. To measure the significance of the dependent constructs’ predictive power, PLS does as a result use theQ2 value as a criterion, which is calculated following the PLS-predict procedure. If Q2 > 0, the model has good predictive capability (Shmueli et al., 2016). All Q2predict > 0 for the dependent constructs in both models (Tables 8 and 9). Next, we considered whether prediction errors are symmetrically distributed. As the skewness of the absolute value for most indicators is less than 1, the root mean squared error (RMSE) is used. In cases where the skewness of the absolute value is greater than 1, the MAE is used (Tables 10 and 11).

The model did not show any predictive power for PPT and ISCE using either RMSE or MAE. However, the model only shows low predictive power for POA, as SD9 has a positive Q2 predict and negative differences for RMSE (recommended) and MAE; however, SD6 has a positive Q2 predict but negative differences for RMSE (recommended) and positive differences for MAE. With respect to SD8, it has a positive Q2 predict but positive differences for both RMSE (recommended) and MAE, and this indicator does not therefore contribute to the predictive value. Regarding the EOA construct, the model exhibits some predictive power because SD11 has a positive Q2 predict and negative differences for RMSE (recommended) and MAE; however, SD5 has a positive Q2 predict but negative differences for RMSE (recommended) and positive differences for MAE.

Finally, the model exhibits great predictive power for ORB, since SD13, SD14 and SD15 have positive Q2 predict and negative differences for RMSE and MAE; only SD12 has a positive Q2 predict but both negative and positive differences, meaning this indicator does not contribute to the predictive value. We can conclude by affirming the predictive validity of the model.

Discussion

This study focused on the SE, CE, and SDGs as lines of interest for academics in accounting for nonprofit management. It has investigated how CE improves the efficiency of products and resources by using a sustainability accounting approach, primarily in companies (Marco-Fondevila et al., 2021; Scarpellini, 2022; Stewart and Niero, 2018; Skare et al., 2024). Socio-ecological transition entails developing CE as an equitable economic model under a territorial approach; so, the role of SE enterprises may be relevant. The SE can favor collaboration between close-at-hand actors for environmentally sustainable actions in a circular model that, in addition to closing material loops at a regional level, contemplates inclusion and resource redistribution in line with solidarity models. The findings indicate that the SE must be included in CE studies at a micro level because of its great potential at a regional level (Scarpellini et al., 2019).

The primary objective of this study is to develop a CE-SDGs framework based on the definition of two complementary models. In this framework, CE is considered to be the precedent, with SDGs being a consequence of the CE. Support in a theoretical framework defined by resources, capabilities and dynamic capabilities theories enabled us to find meaning in this model. In this regard, the paper shares the fact, with numerous authors, that enterprises incorporate a multitude of resources and capabilities into their strategies, generating social and environmental impact (Sassanelli et al., 2020; Abeysekera, 2022; Gallardo-Vázquez and Valdez Juárez, 2022: Allen et al., 2024; Xiao et al., 2024), and making it possible to obtain competitive advantages and contribute to sustainable value creation (Hitt et al., 2020; Asiaei et al., 2020; Caby et al., 2020). Causal relationships between CE and SDGs are identified by quantifying their magnitude (Kamble and Gunasekaran, 2020). This study indicates that it is possible to use dynamic capabilities as pillars for the sustainable growth of organizations, obtaining social change that begins in the CE and ends in the SDGs (Ledesma-Chaves et al., 2020; Calabrese et al., 2021; Brodny and Tutak, 2023a).

A major concern with the CE precedent model was whether the implications of CE activities could have determined the professional profiles and training of the stakeholders and whether the enterprises involved had adequate information on sustainability. The present results show that SDGs can be achieved by implementing CE strategies, as previously reported by García-Saravia Ortiz-de-Montellano et al., 2023. The current findings further confirmed that involvement in circular activities determines organizations’ professional profiles and training. In this regard, the focus is in line with the First Circular Economy Action Plan 2021–2023 (Government of Spain, 2021) when considering training activities and job creation as responsible and circular actions capable of generating progress and social change. It is also important to consider the collaboration between different parties because the introduction of these measures in circular models generates value (Villalba-Eguiluz et al., 2020; Ahmad et al., 2023). In this CE model, it is necessary to maintain transparent information capable of reporting investments made, activities undertaken, and the impact generated by circular activities (Moneva et al., 2023).

The present research’s approach supported the idea that enterprises with a CE orientation are also capable of being adequately dedicated to achieving SDGs, which contributed to defining the SDGs consequence model. In particular, this study focused on activities related to people and the planet in order to refine García-Saravia Ortiz-de-Montellano et al., 2023 vision. The current results thus confirm other authors’ perceptions that the CE is a fundamental agent of sustainable development (Mozas, 2019; Flores, 2021; Cis, 2020).

The causal relationships determine the link between professional profiles and training in POA. Such profiles and skills improve productivity, employment, and results, confirming the findings (Scarpellini, 2021; Marrucci et al., 2021; Portillo-Tarragona et al., 2022). The same does not occur for activities oriented toward the planet; therefore, in this regard, the authors do not share the opinion of Pérez et al. (2020). With respect to the other causal relationships, the existence of corporate reports that obtain data on circular activities is crucial to achieving orientation toward the SDGs, for activities oriented toward both people and the planet. Finally, model 2 implies that the existence of barriers and incentives determines the observed results, being aware that the lack of specialized training in human resources always has a significant incidence (Portillo-Tarragona et al., 2017; Scarpellini et al., 2020).

Finally, and albeit with different objectives, both SE and CE subordinate economic activity to other factors and, therefore, have both raised the discussion about economic paradigms and associated underlying values (Sahakian and Dunand, 2015). The active participation of SE enterprises in different areas of CE will grow within the next few years in aspects such as product recycling, the second-hand goods market (with the transfer of municipal spaces to SE associations and enterprises), the reuse of products within the SE (directly or indirectly through prior preparation), or the promotion of responsible consumption and training activities. It should also be highlighted that SE has been a pioneer in generating employment linked to CE and that its potential will be strengthened by the mutual benefits provided by the ecological transition and the reinforcement of social inclusion.

Conclusions

This study sought to develop a CE-SDGs framework by considering two models based on CE actions and their incidence in SDGs. From our perspective, CE practices represent an precedent for enterprises, and SDGs are the consequence of these CE practices. Three particular actions were considered as part of the CE precedent model (Model 1), and two more actions formed part of the SDG consequence model (Model 2). Model 1 proposes a causal conceptual model between CE and the achievement of the SDGs, materializing in actions oriented toward people and the planet. Given the uncertainty of achieving full compliance with the proposed hypotheses, we asked whether the reason for not achieving it could be found in the existence of barriers to CE. The first model was as a result completed with a second one, Model 2, which shows the incidence of said barriers on the observed results. More precisely, the study examines whether the SE enterprises involved in CE activities have adequately defined professional profiles, and provide adequate training to their stakeholders and information on sustainability and the CE. These actions could determine the enterprises’ orientation toward the SDGs in such a way that they achieve people- and planet-oriented activities.

Testing the hypotheses allows us to deduce the orientation of these companies in their CE strategies, leading to the achievement of the SDGs and being able to answer most of the research questions raised (RQ1, RQ2, and RQ4). Regarding RQ3, this is partially answered because it is not possible to confirm H4. The results for Model 1 are positive, supporting all the hypotheses except one, i.e., the existence of a relationship between professional profiles, training, and planet-oriented activities. Model 2 supports the hypothesis that links barriers and incentives to engage in CE with the observed results and benefits of achieving SDGs. García-Saravia Ortiz-de-Montellano et al., 2023 suggested that the CE has evolved into a framework that links the achievement of SDGs with the practical objectives of business strategies. This approach was broadened by the present research’s model, which comprises a combined theoretical framework.

Model 1 does in particular define six hypotheses, five of which are supported. It is therefore confirmed that involvement in CE has a direct and positive influence on professional profile training and information on sustainability and CE. Furthermore, it is confirmed that professional profiles and training have a direct and positive influence on people-oriented activities, but not on planet-oriented activities. Finally, it is concluded that information on sustainability and CE have a direct and positive influence on people- and planet-oriented activities. Along with the previous model, Model 2 defines a hypothesis confirming that the greater the influence of barriers and incentives on CE, the greater the observed results and benefits.

The results confirm the existence of a precedent in the CE and its consequences in the achievement of the SDGs, adequately applying resources and capacities, as stated in the theoretical framework. This finding is an important and interesting advancement in the literature. Thus, SE is relevant to the value chain in the region and expands the potential for collective social innovation based on the complementarity of different types of actors. Given the above, an initial framework is contributed, uniting two lines of research and analyzing their connection with SE companies. This framework can be enriched with future research and empirical validations in order to contribute in a deep and significant way to the body of knowledge.

Using SE companies as the focus of the study can offer a series of significant benefits, all of them aimed at generating knowledge, among which we should note: i) Understanding of alternative business practices: SE companies operate with a different approach to those used by traditional companies, combining economic and social objectives. The ES is a space where a balance is sought between the generation of economic value and the creation of social impact. Studying these organizations provides an opportunity to understand alternative business models that prioritize social impact over financial benefits. This can lead to the identification of innovative and sustainable business practices that allow us to examine how these organizations integrate and manage these two types of objectives effectively, and which could be applicable in a variety of contexts; ii) Promoting innovation and social impact: SE companies are often at the forefront of social innovation, developing creative solutions to address social and environmental challenges. These companies can offer insights into how they incorporate social and environmental considerations into their business activities, thereby contributing to a more holistic and sustainable approach to business management. Studying these organizations can in addition help to identify new ways to address complex problems and promote collaboration between the business sector, government and civil society in order to drive positive social change; iii) Identification of effective corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices: SE companies often actively engage with the community and adopt CSR practices in their daily operations. Studying these organizations can provide examples of how companies can make a positive impact on society beyond their core business operations. This may inspire other companies to adopt similar practices and foster a more socially responsible company culture; and iv) Promotion of favorable public policies: By highlighting the role and impact of SE companies, studies can influence the development of public policies that support and encourage these types of organizations. This may include tax incentives, specific financing programs or regulatory frameworks that recognize and promote the unique contribution of SE companies to social and economic well-being.

Ultimately, studying SE companies not only provides a deeper understanding of this unique business sector, but can also inspire more ethical, sustainable and socially responsible business practices overall. Expected benefits include identifying innovative business models, fostering collaboration between different stakeholders, and promoting favorable public policies that support SE. Listed below are some real cases of social economy entities with a clear orientation to CE and the SDGs mentioned and, therefore, instigators of social change. With a more social orientation, the BBVA FoundationFootnote 1 stands out. It is a leading organization in social responsibility that carries out educational and cultural programs that promote the full sustainable development of society. It carries out extensive promotion of knowledge, innovation and social impact through its numerous programs and awards calls aimed at the great challenges of the 21st century. The Maimona FoundationFootnote 2 also develops projects aimed at promoting innovation and the capabilities of knowledge companies. The ONCE FoundationFootnote 3 is broadly committed to sustainability, working with a responsible, sustainable and shared value approach. Wazo CoopFootnote 4 develops projects for the social transformation of rural areas, with a clear orientation to all the SDGs. Oriented toward technology, the ONCE Foundation also carries out accessible technology projects and their adaptation to people with visual disabilities, avoiding the possible risk of exclusion and avoiding losing the connection with the information and knowledge society. The Hormiga VerdeFootnote 5 carries out correct management of electronic waste, taking care of everything from its collection to its recovery, and with a clear CE strategy. MovilexFootnote 6 is a Spanish recycling company, committed to the environment and currently present in four different countries. This company acts as an urban mining operator within the CE, today converted into the main recycling company nationwide. EnVerde Cooperativa Extremeña de EnergíaFootnote 7 is a renewable energy consumption entity, being convinced that a distributed, horizontal energy model in the hands of people is possible. All of these entities clearly contribute with their CE strategy to the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs.

This study does at the same time present theoretical and practical implications. From a theoretical perspective, a CE-SDGs framework has been achieved first, beyond the implications of each line of research and through application of the aforementioned theories. This framework allows SE enterprises (and, by extension, companies in general) to understand the first path to achieving SDGs. Secondly, both the CE and the SDGs seek a fundamental change in the way the economy is conceived and implemented, which can lead to a reorientation of the economic paradigm, generating a change from the linear model of production and consumption toward a more circular and sustainable one where resources are used more efficiently, and minimizing waste. Thirdly, a focus on collaboration and inclusion will also be achieved. The SE is based on principles of solidarity, participation and cooperation. The implementation of the CE and the SDGs requires a similar approach, fostering collaboration between different actors, including governments, businesses, non-governmental organizations and civil society in order to address social and environmental challenges comprehensively. Fourthly, the promotion of equity and social justice is also achieved. Both the CE and the SDGs aim to promote equity and social justice, by ensuring that the benefits of economic and social development are distributed fairly among all members of society. This involves a focus on the inclusion of marginalized and vulnerable groups and the reduction of social and economic inequalities.

From a practical perspective, SE managers must be committed to introducing CE practices to achieve people- and planet-oriented objectives. Moreover, enterprises and managers must be aware that even if there are barriers and incentives for CE, they do not negatively influence the results and benefits obtained. Thus, managers must be proactive in including CE actions, promoting sustainable business practices through SE (adoption of business models based on reuse, recycling and sustainable production, as well as the implementation of environmentally and socially responsible management practices). Furthermore, SE can be an engine of support for social and environmental innovation in the search for creative and sustainable solutions to challenges (development of innovative products and services that promote circularity, as well as the creation of new forms of collaboration and financing for sustainable development projects). Finally, SE can contribute to sustainable job creation and community development by boosting economic activity in sectors such as the green economy, waste management and renewable energy. This will provide significant employment opportunities, especially for marginalized and disadvantaged groups, and strengthen the resilience of local communities.

Although this study has several advantages, it has some limitations. First of all we should mention the possible subjectivity that involves the responses to all questionnaires. This subjectivity is caused by many aspects, such as variability in individual interpretations, cognitive bias, level of understanding, context and emotional state, as well as response style. Given such a variety of situations, it is understood that each person has their own perspective, their previous experiences and a frame of reference that influences how they interpret the questions. In this way, the perception changes completely, and what is clear and direct for one person can be confusing or ambiguous for another, in such a way that variability in interpretation can lead to different answers for the same question and generates the aforementioned subjectivity. Second, only SE enterprises in Spain are analyzed. It is known that SE companies may have specific characteristics and objectives that significantly differentiate them from traditional for-profit companies. Therefore, the findings of the study may not be generalizable to other organizations outside the field of social economy, limiting the applicability of the results to a broader context and potentially reducing their relevance for conventional companies. On the other hand, there is a risk of introducing sample bias, meaning that the study’s conclusions may be biased toward the specific characteristics and behaviors of these types of organizations, without capturing the diversity and complexity of the business landscape in its entirety. This limitation will also mean the lack of comparison with traditional companies, since by not including for-profit companies in the study, the opportunity to make significant comparisons between different types of organizations is lost. These possible comparisons with traditional companies could provide valuable information on differences in performance, management strategies, social impact and other relevant aspects.

Possible future research directions are therefore considered. In this regard, it would be interesting to approach the study based on other theories to determine if these ones provide better results or more information than the present one. The conclusion that the CE-SDGs framework depends on the theory used can therefore be deduced. Other constructs can at the same time be incorporated, both related to the CE and SDGs, in order to broaden the field of study of these two complementary models. Finally, it would be interesting to expand the sample to include more national and international social enterprises, as well as other types of traditional for-profit companies, which would allow for a comparative vision. The study could also be conducted by using the type of company (social economy sector/traditional company) as a moderating variable.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality agreement with participants but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

Available in: https://www.fbbva.es/

Available in: https://maimona.org/

Available in: https://wazo.coop/

Available in: https://lahormigaverde.org/

Available in: https://movilex.es/

Available in: https://www.energiaenverde.com/

References

Abeysekera I (2022) A framework for sustainability reporting. Sustain Account Manag Policy J 13(6):1386–1409. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-08-2021-0316

Ahmad F, Bask A, Laari S, Robinson CV (2023) Business management perspectives on the circular economy: present state and future directions. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 187:122182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122182

Alameda MTP (2018) Trabajo autónomo decente de la mujer. In: Blázquez Agudo EM (ed) Los ODS como punto de partida para el fomento de la calidad en el empleo femenino. Dykinson, p 93–130