Abstract

As an outstanding scholar in social education research in the Republican period, Ma Zongrong devotes his life to promoting the “Chinization of social education.” Ma Zongrong believes that for social education to truly save the country and the people in China, the prerequisite is to localize social education. This study finds that the Chinization of social education advocated by Ma Zongrong refers to adapting the theory and practice of social education to China’s national conditions and manifesting Chinese characteristics. The specific connotations of Ma Zongrong’s Chinization of social education include the Chinization of social education objects, the Chinization of social education definitions, and the Chinization of social education goals. From a Chinese perspective, he introduces the advanced social education concepts of Japan and the West and combines them with China’s unique national conditions to form a form of social education with Chinese characteristics; from a global perspective, Ma Zongrong’s combination of Japanese and Western social education with China’s local education system provides a successful case worthy of study by the world.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Social education is a foreign concept introduced in modern China. With the deepening of cultural exchanges and understanding between China and abroad, as well as changes in social forms, after the 1920s and 1930s, the Chinization of academics became the demand of many scholars in the fields of education, history, sociology, and other social sciences, among which Ma Zongrong was one of the pioneers who advocated the “Chinization of social education.”

Ma Zongrong (1896–1944), courtesy name Jihua, was born in Guiyang in 1896 and was sent to Japan in 1919 to study mining at public expense, but later entered Tokyo Imperial University to study social education due to the current situation in China. In 1927, he received a bachelor’s degree in literature and continued his studies at the Research Institute of Tokyo Imperial Universities. His mentors, such as Yoshida Kumaji 吉田熊次 and Haruyama Sakuki春山作樹, were famous social educators in Japan at that time. In 1929, Ma Zongrong returned to China after graduation and was invited by the president of the Great China University大夏大學 to be the head librarian. In 1930, the Great China University established the Department of Social Education within the School of Education to study social education academia and cultivate specialized talents in social education (Huang, 1935, p.28), making it the first university in China to establish a department of social education, with Ma Zongrong serving as the first dean of the department. In 1935, he was recommended by Cai Yuanpei as the Director of the Social Education Department of the Ministry of Education. After the outbreak of the Anti-Japanese War, he resigned from his position in the Ministry of Education. He was the General Affairs Director and Professor of Education at the relocated Great China University. In 1942, he served as the Director of the editorial office of Wentong Publishing House文通書局. Later, the National Central Mass Education Center國立中央民眾教育館was established in Chongqing, and he served as its Director.

Ma Zongrong is the first person in modern China who studied social education theory in Japan and returned to China with the goal of “social education Chinization”, organically combining social education theory and practice to form a set of theoretical systems of social education with Chinese characteristics, and who has spent his whole life researching the theory and practice of social education in China. He wrote extensively throughout his life, of which >20 are currently available, and social education was his favorite educational cause. Compared to his contemporaries in the Republic of China, Ma was one of the most productive and accomplished scholars in the field of social education. As he says in the New Theory of Social Education in the Great Era大時代社會教育新論, “The thought of ‘how to make social education Chinization’ comes to my mind at times.”(Ma, 1941, p.1).

Studying social education in the Republic of China, one must recognize Ma Zongrong. The purpose of this paper is to address the following three questions: Why can social education be localized in China? What attempts and explorations were made during the Chinization of social education? How did the Chinization of social education affect the modern academic field in China? This article adopts a case study method. The case study shows the explanatory rather than just descriptive or exploratory functions of single-case studies. (Robert, 2018, p.34) Robert suggests that “The inability to replicate at will (and with variations designed to rule out specific rivals) is part of the problem. We should use those singular-event case studies (which can never be replicated) to their fullest.” (Robert, 2018, p.2) This article takes Ma Zongrong’s personal experience as a case study to explore the possibility and necessity of the development of social education in China from a micro perspective.

What must be done: the possibility and necessity of “social education Chinization”

The emergence of Ma Zongrong’s idea of the “Chinization of social education” is closely related to the urgent need to construct an independent theoretical system of social education. Since the late Qing Dynasty, China has been invaded by Western powers, and many people believe that it is a problem with Chinese education and advocate for a comprehensive acceptance of the Western education model. The education trend of complete Westernization was very prevalent at that time. This phenomenon aroused scholars’ alertness and deep concern. As early as 1902, when confronted with the question of “Chinese (learning as the) essence” 中體and “Western (learning for its) utility” 西用, Liang Qichao warned the academic circle: “Firstly, do not be a slave to the old Chinese learning, and secondly, do not be a slave to the new Western learning.” (Liang, 1902, p.12) In 1925, Xu Shilian seriously criticized “plagiarizing foreign materials” as one of the problems of Chinese scholars engaged in sociology teaching in his article Research on Sociological Courses 對於社會學教程的研究. (Xu, 1925, p.214) Blind imitation of the West has detached the theoretical research and practical exploration of education from China’s national conditions, thus failing to solve the practical problems of Chinese education effectively. For example, according to Zhang Zhicheng, “To force the methods of other countries to be applied to our country, I am afraid that we may be cutting our feet to fit our shoes.” (Zhang, 1929, p.2) As an “imported product” of social education, compared with other types of education, the phenomenon of incompatibility is more serious. Against this background, social education researchers have gradually developed a consciousness of the Chinization of social education. Ma Zongrong is a pioneer in advocating the construction of social education theory with localized characteristics and exploring the Chinese road of social education.

The academic atmosphere of pursuing localization provided the ideological field for the proposal of Ma Zongrong’s theory of social education Chinization. The eastward spread of Western learning is an important phenomenon that runs through modern Chinese society. It not only brought advanced science and technology to China, which had been closed for thousands of years but also shook the feudal foundation of China from the perspective of ideology and culture. China’s Western learning and modernization began at the end of the 19th century. By the 1920s and 1930s, the study of advanced Western civilization had entered the ideological and cultural level and conscious initiative stage. From the massive introduction of Western theories and trends in the early stage to the critical reception and use of them to solve China’s practical problems, China has gradually changed from passive modernization to active modernization and has come to realize that to modernize itself actively, it can neither return to the closed door of feudalism nor unthinkingly and passively receive Western ideas wholesale. Still, it must stand on the height of world development and co-creation of world culture and seek a way that is not only in line with international standards but also able to solve China’s real problems in light of Chinese conditions. The process of Western learning and modernization in China went from passive to active, and the 1920s and 1930s were the critical stages in China’s transformation from passive modernization to active modernization. Ma Zongrong’s theory of the Chinization of social education occurred in such an ideological field. Ma Zongrong’s theory of the Chinization of social education arose in this ideological field.

Rational reflection on the wave of Western learning laid the ideological foundation for Ma Zongrong’s Chinization of social education. Ma Zongrong believed that social education was a newly developed educational facility. All the countries in the world were working tirelessly and individually to engage in the actual facilities of social education. In Ma Zongrong’s view, “newly created things, which have not yet been experienced over a long period, may not be worth emulating in every case.” (Ma, 1933, p.1) It can be seen that Ma Zongrong had a sober and prudent judgment and choice of Western learning.

The academic demand for active localization provides an intrinsic driving force for the formulation of Ma Zongrong’s theory of the Chinization of social education. As a teenager, Ma Zongrong received a systematic traditional education. Under the influence of Confucianism’s concepts of “cultivating one’s moral character, aligning one’s family, ruling the country, and pacifying the world” and “the rise and fall of the world is the responsibility of all men,” Ma Zongrong formed the spirit of patriotism and service to the people at an early age. From the perspective of Ma Zongrong’s life journey, he lived in a turbulent environment throughout his life. The invasion of foreign enemies, political corruption, and the downfall of rural areas were all visible hardships for Ma Zongrong, which further strengthened his determination to save the country and the people. In the spring of 1918, to develop Guizhou’s mining industry and increase fiscal revenue, the Finance Department of Guizhou Province recruited government-funded students studying in Japan to specialize in mining. Ma Zongrong immediately rushed to Guiyang to take the exam and was admitted with excellent results. He was then qualified as a government-funded student and sent to Japan. In Toyo, Ma Zongrong started his studies in mining and studied at Tokyo First Higher Preparatory School and Nagoya Eighth Higher Undergraduate School. While studying in Japan, Ma realized that “social education is more important than school education.” (Ma, 1925, p.2) However, social education in China is seriously lacking and insufficient, “still in a state of the incomplete form.” (Ma, 1925, p.1) So, Ma Zongrong changed his major and began specializing in social education. He recounted, “In the early years of the Republic of China, I studied abroad and witnessed the ignorance of our people’s wisdom, the low morality of the people, the weakness of the people’s physical strength, and I felt that our country’s education could not be universalized, the social education was not vibrant, and there was a lack of specialists in social education, so I chose social pedagogy as the subject of my specialization.” (Ma, 1941, p.377) In Ma Zongrong’s view, the main reason why China’s social education cannot develop and mature quickly is that people lack common sense in social education. To solve this problem, the first task was to popularize the general knowledge of social education in society. In 1923, Ma Zongrong began to write the book Overview of Social Education社會教育概說, initiating his exploration of the Chinization of social education theory.

The Chinization of social education is an inevitable requirement for social education to be rooted in China. Ma Zongrong’s advocacy of social education has a strong motive for national salvation. Given China’s national conditions at that time, Ma Zongrong believed that it took more work to complete the task of upgrading the people’s quality and promoting society’s development by relying only on school education, and social education could make up for this deficiency. Social education has a vital role in saving the country, so it is essential to vigorously develop social education in China; as he discussed in his book Overview of Social Education, “Social education is necessary in two ways. Firstly, schools can only teach a few people in an undeveloped state and cannot teach people for the rest of their lives. Therefore, social education is indispensable in addition to family and school education. In other words, for the sake of society, social education is indispensable, and education is closely related to the environment. Social education can change the social environment. For the sake of education, social education is indispensable.” (Ma, 1925, p.99) “Social education” in modern China is an “imported product”. (Wang and Liu, 2022, pp.1–10) The concept of social education was originally imported from Japan, and many of the facilities and methods were directly imported, but they have yet to take root in China. For social education to flourish in China, it must be adapted to Chinese conditions, and it must try its best to show “Chinese wisdom” and run a Chinese-style social education. Ma Zongrong tried to build an organized and specialized theoretical system of social education by studying and introducing Japanese social education and adapting it to the characteristics of Chinese society at that time.

Borrowing and integration: the exploration of “Chinization of social education”

As a professional with a clear understanding of the current situation of social education in China, Ma Zongrong knew that he could not wholly copy the Western social education theory and practice, so he made a bold attempt to learn from and integrate the Japanese and Western social education as a reference and integrated the traditional Chinese social education concepts, facilities, and undertakings. With the support of his deep knowledge of traditional Chinese education and theoretical foundation, Ma’s attempts, instead of being awkwardly neither Chinese nor Western, responded to the needs of the times and contributed to promoting the early exploration of modern Chinese social education.

Ma Zongrong believes that the first step in exploring the Chinization of social education should be to understand the history and current situation of the development of social education theory and practice in Japan, Europe, and the United States, and on this basis, to draw lessons from it through comparative research. In 1933, in his book Comparative Social Education比較社會教育, he suggested that “the shortest way to understand the strengths and weaknesses of social education in one’s own country is to compare and study it with social education in other countries.” (Ma, 1933, p.1) Ma Zongrong translated several works by the Japanese social educator Yoshida Kumaji. He pointed out that while social education in China appears to be well developed, it often suffers from “the fallacy of considering the part as the whole, or from the disadvantage of emptiness”, so he suggested that “those who specialize in social education should make efforts to discover its complete principles and organization. The historical and comparative research methods are indispensable to discovering the principles and organization. The monographs produced by social education experts in various countries are also worth introducing.” (Ma, 1935, pp.1–2).

To reasonably draw on advanced social education theories from abroad, Ma Zongrong has done three aspects of work.

Firstly, he read a large number of books on foreign social education. Ma Zongrong recounted that 1 day, while studying at Japan’s First High School, he read a new book called Practical Study of Social Education 社會教育的實際研究in a bookstore, which Kawabata Shosuke 江幡龜壽 of the Japanese Ministry of Education edited. He said, “After reading this book, I felt the necessity of social education, especially in countries like China where education is not yet widespread.” (Ma, 1944a, 1944b, p.4) While studying at Japan’s Eighth High School, Ma Zongrong read many education-related books, with particular emphasis on specialized books on social education librarianship. He said, “I borrowed all the librarianship books and magazines in the library of the Eighth High School and the Nagoya Municipal Library. I can say that I have bought and read nine out of ten books and magazines specializing in social education and librarianship published in Japan.” (Ma, 1944a, 1944b, p.4) Ma Zongrong studied in Japan in 1919 and returned to China in 1929. During his ten years of study in Japan, Ma read many foreign works on social education, which opened up a broad international perspective for Ma’s early exploration of social education.

Secondly, he translated the works of renowned foreign social educators. When Ma Zongrong began working on the translations, he found that, unlike the prosperity of other Western educational disciplines introduced in China, there needed to be more complete translations of foreign theoretical works in social education. Although the first Chinese educational publication, The Education World 教育世界translated Japanese expert Sato Yoshiharu’s佐藤善治郎 The Recent Social Education Methods最近社會教育法 in 1902, and some works of the German School of Social Pedagogy were also translated in 1905, the overall number was small. Table 1 shows the topics of the German School of Social Pedagogy published in The Education World教育世界.

Ma Zongrong translated the Basic Theory of Social Education社會教育原論by Yoshida Kumaji, a renowned social educator from Tokyo Imperial University, in 1933. The book, initially titled Social Education社會教育, was published in 1913. After revision and supplementation, it was published under the Basic Theory of Social Education title in March 1934. Three months later, it was translated into Chinese by Ma Zongrong and published by Zhonghua Book Company 中華書局in January of the following year. The book consists of five parts. The first part discusses the principles of social education, covering the essence, types, and evolution of social education in Japan. The second and third parts introduce the objects and institutions of education in Japan and the principal developed countries of Europe and the United States. The fourth and fifth parts are divided into special topics to introduce the evolution of social education in Europe, America, and Japan. Translating the works of renowned foreign educators is conducive to the formation of a complete understanding of the principles and organization of social education, and it is also a shortcut to reflecting on the insufficient social education in China.

Thirdly, he wrote monographs on social educational theories. Suppose the translation and introduction of foreign social educational works is a preparation for borrowing. In that case, the writing of monographs on social educational theories, the appropriate incorporation of foreign educational theories and practical experiences, and the citation of the views of famous foreign social educators in the book is a borrowing after digestion. Ma Zongrong’s life-long research in social education has been fruitful. He has translated and written >20 books on education, including eight monographs and one translation with “social education” in the title. He also published dozens of articles in newspapers and magazines at the time, such as Three Major Issues to Be Aware of in Popularizing Social Education and Review and Prospect of Social Education in China. His research results cover many aspects, such as the principle of social education, social education undertakings, social education administration, comparative social education, social education practice, etc. Table 2 shows Ma Zongrong’s works that include “social education” in their titles. Ma Zongrong extensively references the results of related work at home and abroad in these books. Ma Zongrong said,

The contents of this work have been taken from the famous theories of experts in social education both at home and abroad, with particular reference to Haruyama Sakuki’s春山作樹 Handouts on Social Education社會教育講義, Kawamoto Unosuke’s川本宇之介 The System and Facility Management of Social Education社會教育之體系與設施經營, Hanji Obi’s 小尾範治郎Introduction of Social Education社會教育概論, Kabe Dolphingo’s 建部遁吾Education and Politics教政學, F.V. Thorndike’s 桑代克Adult Learning成人學習, and the Jiangsu Provincial Zhenjiang Mass Education Center’s Mass Education Newsletter民眾教育通訊 is particularly well referenced. (Ma, 1934, p.3)

Specifically, in naming the concept of “social education”, Ma refers to the views of scholars from the United Kingdom, the United States, Germany, and Japan. In discussing the role of social education, he identifies the views of the Japanese scholar Yoshida Kumaji and the Chinese scholars Zhao Shuju, Fu Baochen, and Gao Yang. Regarding the approaches to social education, Ma Zongrong draws on the Japanese sociologist Kabe Dolphingo’s concept of “edification” in his Education and Politics, which states that “the methods of edification, instruction, teaching, and popularization, that is, juvenile education, can be applied as methods of social education.”(Ma, 1934, p.97) In arguing for how social education is possible, Ma Zongrong refers primarily to the experimental results of international psychologists such as Thorndike.

Integration is a further local enhancement based on borrowing and pursuing self-innovative development. Ma Zongrong always maintained a clear judgment in absorbing and borrowing foreign experiences, as he did “according to the discretion of his own eyes.” (Ma, 1925, p.1) Ma Zongrong’s integration innovation of social education theory is mainly reflected in three aspects of exploration.

Firstly, Ma Zongrong integrates the more advanced social education theoretical systems of Japan, Europe, and the U.S. In 1933, Ma Zongrong published Comparative Social Education 比較社會教育, a textbook for the university course “Comparative Social Education,” which was also the first monograph on comparative social education in China. This book collects the social education situations of eight countries, including the UK, Germany, the US, France, Italy, Russia, Denmark, and Japan, which have achieved good results through experimentation and practice. Through comparison, Ma Zongrong found that the focus of social education in different countries is different, and the objects of social education in different countries also have different meanings. Ma Zongrong put forward his opinions based on integrating foreign social education objects. In his book Comparative Social Education, he especially declared that “the object of social education is the whole society: fetus, infant, toddler, teenager, youth, adult and old people, and there is no part of the people that should not be noticed. Normal people and abnormal people are all subjects of social education. Although social education was first organized with a focus on adults, we should know that the social education of adults is an important part of social education. We must realize that the social education of adults is not enough to include all of the social education.” (Ma, 1933, p.1).

Secondly, based on integrating the advanced social education theories of foreign countries, Ma Zongrong also consciously pays attention to the social education theories of domestic scholars and emphasizes comparing and analyzing the views of domestic and foreign scholars. When classifying the contents of social education, Ma Zongrong comprehensively analyzed the classifications proposed by Zhao Shuyu, Fu Baochen, Liu Shaozhen, Gao Yang, Jiangsu Provincial Education College, and Huangxiang Mass Education Experimental Area, pointed out the problems of their classifications, and finally refined a unique classification of “five categories and ten kinds”. (Ma, 1934, p.34).

Thirdly, Ma Zongrong also pays great attention to the communication of theories related to social education between the present and the past. Ma Zongrong focuses on establishing a link between this new thing called “social education” and the “social edification” of ancient China, enabling this “foreign product” to have its past and present in China. He said, “Although the term social education has been adopted in China since the founding of the Republic of China, it has only been more than twenty years since then. However, similar social education facilities in ancient China already have. Its detailed records can be traced back to The Zhou Li周禮.”(Ma, 1934, p.251).

The formation of Ma Zongrong’s theoretical system of social education thought is based on continuous borrowing and integration. Japanese and Western theories profoundly influenced Ma Zongrong. However, due to the uniqueness of social education and the actual needs of China’s society, there are many irrationalities in copying Western theories. Ma Zongrong combined with the needs of China’s social education, borrowing, integration, innovation, and gradual practical exploration, and finally constructed a social education system of thought that meets the national conditions and the characteristics of social education, laying an essential theoretical and practical foundation for the improvement and development of the theory of social education in the Republic of China period.

The local road: the connotation of “Chinization of social education”

The more advanced social education theories in Japan and the West have provided Ma Zongrong with a theoretical basis and methodological guidance for his social education research. Ma Zongrong has absorbed and inherited his predecessors’ theoretical and practical achievements through borrowing and integration. At the same time, Ma Zongrong’s theory of social education was born in a specific Chinese historical context, rooted in the soil of China’s specific historical environment, with a distinctive spirit of the times and problem awareness, but also rubbed in China’s characteristics, forming a brand-new theoretical system of social education with pluralistic meanings.

Ma Zongrong believes that the first connotation of the Chinization of social education is the Chinization of social educational objects. Different national conditions lead to different social education objects in different countries. Ma Zongrong pointed out that “the objects of social education in some countries is the ignorant and uneducated people in the social populace, while in other countries it is the people who are above 20 years old and below 40 years old.” (Ma, 1925, p.3)“Some think that it is limited to adults who were out of school when they were young, while others think that it is limited to those who are not educated in schools.” (Ma, 1941, p.5) Ma Zongrong believes that these definitions are wrong and that the objects of social education are “all people in society”. In A General Theory of Modern Social Education 現代社會教育泛論, he said, “Social education is education for all people. All people, men, and women, wise and foolish, regardless of occupation, rich or poor, are the objects of social education. All people, young and old, are recipients of social education. No people should be excluded, and no class should be monopolized. Attention must be paid to the entire population at all times and in all places.” (Ma, 1934, p.9) He continued to use this definition in his New Theory of Social Education in the Great Era大時代社會教育新論, published in 1941, emphasizing the “universality” of the objects of social education. Ma Zongrong explained,

Adults who drop out of school at a young age lack common sense and national consciousness. Therefore, mass school education targeting such individuals is critical. Its position in social education is equally vital as compulsory education in school education. Adults who drop out of school at a young age occupy the leading position in social education. Not educated in school can also occupy the leading position in social education because they are currently uneducated. Also, because education in the past was only developed in urban and rural areas that were relatively neglected, rural residents can occupy the main position in social education. However, social education is aimed at all members of the society. Illiterate individuals are the objects of social education, uneducated and poorly educated are the objects of social education, and educated and learned individuals are the objects of social education. Adults who are out of school at an early age are certainly the objects of social education, and young children who have not yet entered kindergarten are also the objects of social education; kindergarteners, elementary school students, secondary school students, university students, researchers in research institutes, regardless of whether they are male or female, are excellent, average, or inferior students, and they are also the objects of social education; teenagers, youths, adults, the old, and people with a disability who have graduated from any school and have entered the community for service, delinquent teenagers, young girls, and those from low-income families, are also the objects of social education. Rural residents are the objects of social education, while urban residents are the objects of social education. (Ma, 1941, pp.5-6)

From the point of view of Ma Zongrong’s elaboration of the object of social education, Ma’s definition reflects the distinctive features of “universality” and “equality”. In Britain and the United States, the object of social education mainly refers to “adolescents between the ages of 14 and 18 and adults over the age of 18”; in Germany, the object of social education refers to “people of the lower social strata who have a lower level of education”; in Japan, according to Kawamoto Unosuke, social education is aimed at “the majority of society”. (Ma, 1925, pp.5-8) Ma Zongrong has broader social education objectives than Japan, Europe, and America. Regarding explaining the “equality” of social education objects, Ma Zongrong promoted the Confucian educational spirit of “education for all”.Footnote 1 He said, “Social education is what Confucius called ‘education for all’ (Ma, 1941, p.5), and it is an education that implements a thorough equality of educational opportunities.” (Ma, 1941, p.5) It embodies the inheritance of the excellent genes of traditional Chinese culture and has prominent Chinese characteristics.

Ma Zongrong believes that the second connotation of the Chinization of social education is the Chinization of the definition of social education. The “Chinization of social education definitions” is an academic concept with Chinese characteristics that Chinese scholars have put forward based on Chinese facts. The Chinization of the definition of social education was one of Ma Zongrong’s more prominent contributions. The YouXue YiBian遊學譯編, founded in Tokyo in 1902, includes an article by Japanese scholar Nakajima Hanjiro 中島半次郎entitled On the Relationship between School and Family and Society論學校對家庭與社會之關係. In this article, Nakajima Hanjiro divided education into three parts: “To be taught by parents at an early age is called family education; to be educated by masters at a later age is called school education; to get on in the world, to treat people and deal with things, to practice, is called social education.”(Nakajima, 1903, p.25) As seen from the concept of social education in Japan, social education is parallel to family and school education. Social education focuses mainly on character education, emphasizing self-cultivation and interpersonal skills. Matsumura Matsumori’s松村松盛 book, The Edification of the People民众的教化, states that social education is education that is conducted by the country, public organizations, or private individuals with the direct purpose of upgrading the qualifications of the people. (Matsumura, 1922, pp.1-13) Kawamoto Unosuke’s The System and Facility Management of Social Education 社會教育之體系與設施經營points out that social education uses various institutional facilities for the majority of society to make use of their leisure time and widely expand the enjoyment of cultural wealth.(Kawamoto, 1931, pp.3-12) Ma Zongrong’s social education theory initially came from his studies in Japan and was heavily influenced by Japanese scholars. Based on drawing inspiration from Japanese scholars, Ma Zongrong further improved and developed the connotation of the definition of social education. He points out: “The country, public organizations or private individuals, to seek the qualification and upward development of the life of all the people in the society, have set up a variety of social institutions and facilities to provide all the people of the society with the freedom to broadly expand their enjoyment of culture wealth in their actual living field, to make an impact on the role of the main body of the society, which is called social education.” (Ma, 1937, p.23).

Ma Zongrong emphasizes six details of the definition of social education. First, social education is education for all people; Second, social education is education for the whole life; Third, social education is education for enriching life, not just for enlightenment; Fourth, social education is education in many forms. There are various educational institutions and facilities to adapt to the psychological requirements and needs of various objects. Fifth, social education is education that utilizes leisure time; Sixth, social education is education that improves the whole society. (Ma, 1937, p.24) Knowing that China’s slow economic development during the Republic of China prevented schooling from becoming widespread, Ma Zongrong developed a social education concept tailored to China’s specific conditions. This concept met the need of the nation to utilize their leisure time for learning and supplemented the inadequacy of school education.

Meanwhile, social education is a concept that is undergoing historical changes. In foreign history, there are many similar concepts to social education, such as “popular education”, “civilian education”, “adult education”, “mass education”, “rural education” and so on. Understanding and using these concepts during the Republican period was very confusing. Ma Zongrong analyzes these concepts based on his view of social education. Ma Zongrong believes that social and mass education were “different in name but the same in reality”. Others, such as popular education, adult education, civilian education, and rural education, are subordinate concepts of social education because of the narrowness of the object and goal of education. (Ma, 1941, pp.10–13) Social education = mass education > popular education, civilian education, adult education, rural education.

Ma Zongrong believes that the third connotation of the Chinization of social education is the Chinization of social education goals. The Chinization of social education goals is an urgent need to solve China’s practical problems, and it is also the most distinctive part of Ma Zongrong’s social education theoretical system. Ma Zongrong believes that to achieve the ideal of improving society as a whole; many goals need to be determined and followed. How do we establish the goals of social education? Ma Zongrong carefully analyzed the division of social education goals between Japan and China. In Japan, Yoshida Kumaji divided social education into (i) child protection, (ii) social education on physical education, (iii) social education on intellectual education, and (iv) social education on affective and esthetic education. He thought that the goals of social education should be physical education for all members of society, intellectual education for all members of society, esthetic education for all members of society, affective education for all members of society, and child protection. Ma Zongrong believes that Yoshida Kumuji’s juxtaposition of child protection with several others is incongruous. Sasaki Kichisaburou佐佐木吉三郎 divided social education into four parts: social intellectual education, social moral education, social affective education, and social physical education. (Sasaki, 1919, pp.361–379) Matsumura Matsumori 松村松盛also has the same classification. They believe that social education aims to cultivate the knowledge, morality, emotions, and physical fitness of the entire society. Ma Zongrong believes that national vocational training has been neglected in all three categories mentioned above. (Ma, 1934, p.32).

Regarding the classification of domestic scholars and universities, Ma Zongrong believes many unreasonable aspects exist. For example, the goals of social education in Gao Yang’s article Discussions on the Implementation Goals and Methods of Social Education are (a) civic education, (b) livelihood education, (c) language and literacy education, (d) health education, (e) family education, (f) art education, and (g) others. (Gao, 1930, p.2) The Jiangsu Provincial Education College 江蘇省立教育學院and the Huangxiang Mass Education Experimental Area 黃巷民眾教育實驗區also categorized their programs into seven items: (1) health education, (2) livelihood education, (3) political education, (4) family education, (5) language and literacy education, (6) leisure education, (7) social interaction education. Ma Zongrong believed that (a) language and literacy education was not enough to represent the entirety of the intellectual education of all people in society. (b) Art education and leisure education, when used alone, could not cover the whole society’s affective education. (c) The scope of political education is not as broad as civic education’s, and the term civic education is also specific and clear, so instead of political education, civic education should be used. (Ma, 1934, p.33).

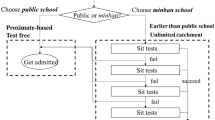

Based on the discussions of domestic and foreign scholars, Ma Zongrong believes that the reasonable division of the goals of social education should be divided into five categories and ten kinds, as shown in Fig. 1.

Ma Zongrong emphasized that, in terms of value, the goals of all kinds of social education should be given equal importance. However, according to the situation, there is a distinction of importance and urgency. He said,

In terms of the current situation in our country, the rural economy is bankrupt in the front, followed by the Japanese invasion, and the national situation is in danger. The strategy to address the problems should first focus on (1) civic education, group training, (2) health education, (3) vocational education, and Chinese language education as the basis of other education, which should be taken into consideration. None of the aspects of health education, such as national physical, hygiene, military, and rescue training, should be neglected. On the one hand, science education should pay attention to the broad sense of national defense science education and actively promote scientific, military education, and production education; on the other hand, it should be excluded from the idea of providence. These five educations are an excellent remedy for reviving China’s four diseases of poverty, ignorance, weakness, and privacy, which can revive the nation. diseases of poverty, ignorance, weakness, and privacy, which can revive the nation. (Ma, 1940, p.26)

The five categories and ten kinds of social educational goals are not mutually exclusive but interwoven in a web-like pattern. It is worth noting that the content of various educational goals is not static. Ma Zongrong’s advocacy for social education aims to meet the needs of national and social development, improve national quality, and increase national competitiveness. Such aims and needs make him always keep a sensitive insight into the direction of national development. He can quickly grasp the relevance of social education goals to Chinese society and closely combine them with China’s national conditions to create a Chinese-style social education that is different from that of the West and adapted to the times. For example, regarding the goals of Chinese language education, Ma Zongrong emphasized in A General Theory of Modern Social Education (1934) that “it is necessary to train the public’s ability to read, write, and fully express themselves.” (Ma, 1934, p.36) In 1941, during the particular period of China’s anti-Japanese war, Ma Zongrong, in his New Theory of Social Education in the Great Era expanded the goals of Chinese language education to include the cultivation of the national spirit and requested that “Chinese language education at all levels should pay attention to the teaching of articles that are sufficiently reserved to emphasize the loyalty of the ancients and their martyrdom.” (Ma, 1941, p.49) These articles include Zhuge Liang’s Northern Expedition Memorial出師表, Li Mi’s A Letter to His Majesty陳情表, Yue Fei’s deeds in defending the country against enemies, and the posthumous works of the martyrs of the Republic of China. Ma Zongrong believes that China’s education has lacked spirit and center in recent decades, resulting in a weak and cowardly national character. Due to the lack of education on national spirit, it has become a nation that does not know shame and upward mobility. Therefore, language education should pay attention to the teaching of these articles to carry forward the virtues of the Chinese forefathers, to promote tenacity and to eliminate cowardice, to establish the culture of teaching war with a clear sense of shame, and to eliminate the habits of atrophy and paralysis. Both the Principles and Undertaking of Social Education 社會教育原理與社會教育事業 and the Introduction to Social Education社會教育入門 published in 1942 paid great attention to this goal of Chinese language education. Overall, Ma Zongrong’s goal of social education always responded to the goals and pursuits of the country and the nation at that time, with prominent Chinese characteristics and unique historical meanings.

Conclusion

Ma Zongrong has devoted his life to social education, and through borrowing and integration, he has made the originally foreign “social education” deeply embedded in Chinese society. Ma Zongrong’s efforts are a valuable legacy in developing social education theory in China. Ma Zongrong was engaged in social education activities throughout his life. After returning to China, he established a four-year social education department at the Great China University, the first of its kind in a Chinese university. When Great China University’s Department of Social Education was established, there was no existing system in China for reference, so “the department created the curriculum and curriculum standards,” and “there were no textbooks for social education, so the department compiled all the textbooks on its own.” (Ma, 1941, p.5) At the initial stage, there were only three full-time teachers in the Department of Social Education: Ma Zongrong, Xu Gongjian, and Zhang Yaoxiang.

Ma Zongrong and Xu Gongjian were responsible for teaching social education courses. They created introductory social education courses such as Principles of Social Education, History of Chinese Social Education, Comparative Social Education, and Social Education Administration. To a certain extent, Ma Zongrong’s ideas on social education broadened the scope, objects, and content of social education, framed concrete implementation plans for the practice of social education, contributed to the deepening, theorizing, and concretizing of social education in modern China, played a positive role in popularizing education and enlightening thought in contemporary China, and facilitated the transformation of traditional Chinese education into modern education.

Ma Zongrong continued to refine the theory of social education in practice. When he worked in the Department of Social Education at the Great China University, he also paid extra attention to students’ social education internships. On the one hand, students were allowed to participate in the affairs of the university’s library, practicing the theories learned in several courses of librarianship, and on the other hand, they cooperated with the Shanghai School for the Deaf and Dumb to serve as an internship base for courses such as mass school education. To enhance the department’s students’ knowledge, Wu Xuexin also personally led students to Shanghai for internships, visiting the Shanghai Municipal Library, museums, stadiums, municipal government organizations, as well as social education institutions such as the Jiangsu Provincial Yutang Mass Education Center and the Horticultural School. (DXWED, 1936, p.45) Most notably, the department has set up several experimental areas, such as the Daxia Commune, the Daxia Mass Education Experimental Area, and the Huaxi Rural Rehabilitation Area in Guizhou, to experiment with the application of various social education approaches on the one hand, and to serve as specialized internship bases for the department’s students on the other. The specific work of these experimental areas is mainly completed by students under the guidance of teachers. Taking the Daxia Commune established in 1932 as an example, the mass schools in the commune provide remedial education for school-age children who have dropped out of school and adult tutoring in rural areas around the university. The specific courses are taught by >20 students from the Great China University, and on this basis, students need to complete internship reports. (Yao, 1933, p.17).

The “Chinization of social education” is not just a theoretical slogan, but social education has been developed locally in a series of social education practices by Ma Zongrong. In modern times, many social education settings, such as libraries, museums, and national cinema institutions, are all evidence of the Chinization of social education. In librarianship, Ma Zongrong put forward the theory of “creating an international librarianship common to the world” and put it into practice. His book editing work was characterized by social education and nationalism: “Expounding the Three Principles of the People, introducing specialized academic subjects, and seeking the socialization of academic subjects for all people, increasing the people’s national consciousness, national concepts, and beliefs in nation-building, improving national culture, and promoting the people’s common sense, as well as arranging and circulating local literature.” (Lv and He, 1997, pp.21–24).

Ma Zongrong’s close integration of his social education theories with society, the state, and the whole nation reflects his far-reaching vision as an educator and his strong sense of social responsibility and national anxiety. Ma Zongrong has given the world a unique and successful Chinese case in a particular historical context. The achievements of social education in the Republic of China should continue to be carried forward and developed in contemporary China and are even more worthy of drawing the attention and learning of the world.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this research as no data were generated or analyzed.

Notes

Not limited by the conditions of nobility, wealth, or poverty, everyone can be taught. Confucius spent his whole life teaching and putting forward the idea of “providing education for all people without discrimination”.

References

Daxia Weekly Editorial Department (1936) Social education department visits city center. Daxia Weekly 9:190

Gao Y (1930) Discussion on the implementation goals and methods of social education. Educ People 6:2

Huang S (1935) Investigation of national mass education personnel training institutions. Guangdong Provincial Mass Education Center, Guangzhou

Kawamoto U (1931) The system and facility management of social education. Latest Education Research Association, Tokyo

Liang QC (1902) The theory of two great masters of modern civilization. Sein Min. Choong Bou 2:12

Lv YQ, He CF (1997) Prof. Ma Zongrong and the editing office of guiyang jiaotong book company. Guizhou Cult Hist, 4:21–24

Ma ZR (1925) Overview of social education. Commercial Press, Shanghai

Ma ZR (1933) Comparative social education. World Book Bureau, Shanghai

Ma ZR (1934) A general theory of modern social education. World Book Bureau, Shanghai

Ma ZR (1935) Facilities and theory of social education. Zhonghua Book Company, Shanghai

Ma ZR (1937) Outline of social education. Commercial Press, Shanghai

Ma ZR (1940) Introduction to social education. Wentong Book Company, Guiyang

Ma ZR (1941) New theory of social education in the great era. Wentong Book Company, Guiyang

Ma ZR (1944a) Memoirs of 48 Years. Cent Daily, Guiyang, p 4

Ma ZR (1944b) Memoirs of 48 Years. Cent Daily, Guiyang, p 4

Matsumura M (1922) The Edification of the People. Imperial Local Administration Association, Tokyo

Nakajima H (1903) On the relationship between school and family and society. YouXue YiBian 3:25

Robert KY (2018) Case study research and applications: design and methods 6th edition. SAGE Publications, London

Sasaki K (1919) しちょうそんimprovement and social education. Meguro Bookstore, Tokyo

Wang XX, Liu JR (2022) Chinese universities’ experience of social education, 1912–1949. Humanit Soc. Sci. Commun. 9:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01366-3

Xu SL (1925) Res. Sociol Courses Sociol Res. 2(4):214

Yao YC (1933) Report on the internship at the Daxia commune mass school. Daxia Weekly 22:457

Zhang ZC (1929) General theory of social education. Qizhi Book Company, Shanghai

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Zhuojun Chen of South China Normal University for her kind assistance in the revision of the Japanese scholars’ English names.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JL conceptualized the study and wrote the original manuscript. XW helped perform the analysis with constructive discussions and manuscript preparation and revisions. All authors have contributed to this study’s conceptualization, development, and improvement.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors. This article mainly uses case studies and historical documentary research methods. Our case object is the educational ideas of Ma Zongrong, a famous educational figure in modern times; as such, experimental data and biological materials are not involved in the analysis of the cases, and none of the historical documents we have cited deal with ethical issues. Therefore, this study does not need to obtain ethical approval.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Wang, X. Chinization of social education: a lifelong exploration of Ma Zongrong’s educational theory and practice. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 823 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03269-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03269-x