Abstract

This study investigates the impact of board gender diversity on the export resilience of Chinese A-share listed firms from 2009 to 2015. Our findings indicate that board gender diversity significantly enhances firms’ export resilience. The results remain robust across various modifications, including adjustments to the sample period, exclusion of extreme values, utilization of alternative measures for critical variables, addressing endogeneity concerns by adding fixed effects and employing the sex ratio at birth as an instrumental variable. Mechanism tests reveal that enhancing the quality of export products, expanding export diversity, and improving corporate reputation are crucial pathways through which board gender diversity can bolster firms’ export resilience. Finally, heterogeneity analysis shows that the positive effect is more pronounced in older firms and those with higher board educational backgrounds. This effect is also more prominent in firms located in provinces with higher levels of non-state economic and product market development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the twenty-first century, global financial and economic crises have become common, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has posed significant challenges for export companies. Consequently, researchers have devoted considerable attention to examining how to withstand external shocks and improve export resilience (He et al. 2022; Mena et al. 2022). Particularly during a crisis, firms require enhanced supervision and guidance to adapt their export strategies effectively. The board, the cornerstone of corporate governance, assumes a pivotal role in decision-making, especially amidst turbulent times (Dupire et al. 2022). Among the various features of the board, gender diversity has garnered significant attention. This focus is mainly attributed to the implementation of mandatory legislation in countries such as Norway and Spain, which requires more excellent representation of women on boards. Notably, compared to their male counterparts, female directors have the potential to enhance corporate governance across multiple dimensions, including diverse perspectives (Adams 2016), adequate supervision (Gul et al. 2011), and high ethical standards (Chen et al. 2016), among others. These attributes serve as effective means to help firms successfully navigate challenges. Therefore, the promotive role of female directors in firms, especially during economic downturns such as the Great Recession, becomes particularly significant (Papangkorn et al. 2021).

Existing research has explored the impact of board gender diversity on firms from various theoretical perspectives. According to resource dependency theory (Salancik and Pfeffer 1978), board gender diversity can provide diversified modes of thinking for firms (Adams 2016), mitigating the issue of homogenized thought commonly associated with male directors. This diversification enhances alignment with the external environment (Carter et al. 2003), thereby improving the performance of firms. According to stakeholder theory (Parmar et al. 2010), firms with gender-diverse boards prioritize stakeholder sentiment and strive to manage their relationships (Ardito et al. 2021). For example, gender-diverse boards can help narrow the wage gap within firms (Carter et al. 2017), increase the level of dividend payments (Ye et al. 2019), and enhance the focus on customer health and safety, prompting the timely recall of defective products (Wowak et al. 2021). According to corporate reputation theory, research indicates that women on boards tend to uphold higher moral standards and adopt a cautious approach to decision-making (Chen et al. 2016), which can promote risk disclosure by firms (Seebeck and Vetter 2021), and decrease corporate fraud and insider trading (Cumming et al. 2015), thereby enhancing corporate reputation. The impact of board gender diversity on firms is evidently substantial and multifaceted. Considering that export value is a crucial performance indicator for firms, it is potentially influenced by board gender diversity. Studies have found that board gender diversity can positively affect firms’ export attitudes (Carbonero et al. 2021).

Due to the increased complexity of the external environment, there has been a surge in research exploring the effects of board gender diversity on firms during times of crisis, yielding mixed results. Against the backdrop of the 2008 global financial crisis, both Chen et al. (2019) and Papangkorn et al. (2021) found that board gender diversity can effectively stave off declines in firm performance and may even enhance it. Similarly, Shamsudin et al. (2022), Amorelli and García‐Sánchez (2023), in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, concluded that board gender diversity holds promise in bolstering firm performance and mitigating the extent of setbacks experienced by firms. Additionally, Azeem et al. (2023) examined the impact of board gender diversity on firm financial resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic, suggesting that while it brings diverse analytical perspectives, it may also lead to internal conflicts. However, Willhans and Kossmann (2022) found that during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was no significantly stronger correlation between board gender diversity and firm financial performance. Existing research focuses on exploring the impact of board gender diversity on firm financial performance during crises, yet consensus remains elusive. Export, a crucial pillar of corporate sales revenue and performance metrics, has endured substantial impacts from crisis shocks. Despite this, there remains a notable lack of studies that systematically investigate the role of board gender diversity in fostering firms’ export resilience, let alone delve into the underlying mechanisms at play.

This study aims to bridge a research gap by examining the impact of board gender diversity on firms’ export resilience. The analysis utilizes a comprehensive dataset comprising 414 Chinese A-share listed firms, encompassing 47,733 firm-product-destination-year level observations from 2009 to 2015. The independent variable employed is board gender diversity. Due to data limitations, complete export data for Chinese export firms is available only up to 2015. Therefore, to identify significant external shocks within our research timeframe, following the method of He et al. (2022), we consider the 2008 global financial crisis as an exogenous shock. We then use the deviation between export values in subsequent years and those in 2008 to measure export resilience, employed as a dependent variable.

Our research demonstrates that board gender diversity significantly enhances firms’ export resilience. This conclusion remains robust even after conducting a series of robustness tests, including sample replacement, outlier removal, adjustment in the core variable measure, and the use of fixed effects and instrumental variables to address endogeneity concerns. Additionally, resource dependency, stakeholder, and corporate reputation theories are used to delve into the underlying mechanisms at play. Our findings reveal that expanding export diversity, improving the quality of export products, and enhancing corporate reputation are crucial pathways through which board gender diversity bolsters firms’ export resilience. Moreover, heterogeneity analysis indicates that the positive effect is more pronounced in firms with older age and higher board education backgrounds. Furthermore, this effect is more prominent in firms located in provinces with higher levels of non-state economic and product market development.

This study contributes to the existing literature in three main ways. Firstly, it enriches the literature on factors influencing firms’ export resilience through corporate governance. While researchers have explored the impact of macroeconomic factors such as development aid (Gnangnon 2022), trade policies (Calı et al. 2022), and export tax rebates (Xu and Liu 2023) on export resilience, as well as, the roles of export diversity (Esposito 2022) and the enhancement of the quality of export products (Wang and Wei 2021) have been examined from a micro perspective. However, there has been limited research from the perspective of corporate governance. We are the first to empirically analyze the impact of board gender diversity, a crucial role in corporate governance, on firms’ export resilience, revealing a significant enhancement due to its presence. Thus, this study provides additional insight from the perspective of corporate governance.

Secondly, this study contributes to uncovering the underlying mechanisms. Existing research has explored the influence of board gender diversity on corporate financial and performance in various crisis contexts (Papangkorn et al. 2021; Amorelli and García‐Sánchez 2023). However, these studies focus on verifying general effects and provide limited analysis of the underlying mechanisms. Drawing on resource dependency theory, stakeholder theory, and corporate reputation theory, this study further reveals that expanding export diversity, enhancing the quality of export products, and improving corporate reputation are vital channels through which board gender diversity enhances firms’ export resilience. This represents a valuable addition to the literature on how board gender diversity influences corporate behavior in crises.

Thirdly, this study contributes to examining the impact of board gender diversity on firms’ export resilience in various environments. Existing research on board gender diversity has conducted heterogeneous analyses focusing on firm-specific characteristics, such as board size and ownership (Ain et al. 2021; García and Herrero 2021). This study emphasizes environments that may foster gender equality as the primary aspect of the heterogeneity analysis. This includes examining the educational level of boards and the fairness of treatment in the non-state economy and product markets of the province where firms are located.

The remainder of this study is organized as follows. The “Literature review and hypotheses” section outlines the relevant literature and hypotheses of this study. The “Data and methodology” section presents the data, variable composition, and methodology. The “Empirical results” section provides the main results, including benchmark regression, robustness test results, and endogeneity analysis. The “Exploring the underlying mechanisms” section covers the mechanical test. The “Heterogeneity analysis” section presents the results of the heterogeneous analysis. Finally, the “ Conclusions” section concludes the study by summarizing the main findings, offering policy recommendations, and discussing limitations.

Literature review and hypotheses

Export resilience

Since Reggiani et al. (2002) introduced resilience as an analyzable economic concept, scholars have gradually applied it to regional economic resilience (Martin 2012; Hu and Dong 2022). The global economic downturn triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic and reduced demand has recently severely impacted international trade. Therefore, some studies examine the export resilience of regions, extending the meaning of resilience to the field of trade (He et al. 2022; Mena et al. 2022). Two lines of thought can be drawn from the existing literature based on the research perspective.

The first stream focuses on measuring export resilience. Researchers have proposed that resilience is the ability of a system to return to its original state after experiencing an external shock (Martin 2012). For instance, Van and Jaarsma (2017) regard the 2008 global financial crisis as an external shock and define export resilience as the recovery of export value. Similarly, He et al. (2022) used the concept of deviation to calculate export resilience. Moreover, Mena et al. (2022) designated the COVID-19 pandemic as an external shock and utilized the export gap between 2020 and 2019 to measure export resilience. Additionally, some studies adopt the residual method, selecting indicators that reflect export resilience (Gnangnon 2021).

The second stream of literature focuses on factors affecting export resilience. Existing research has explored the impact of macroeconomic factors such as development aid (Gnangnon 2022), trade policies (Calı et al. 2022), and export tax rebates (Xu and Liu 2023) on export resilience. From a microscopic perspective, Wang and Wei (2021) and Wei et al. (2023) observed that external shocks lead to fluctuations in consumer income, causing consumers to be more cautious and discerning in their product choices. As a result, firms with high-quality export products can meet the stringent standards demanded by foreign markets, thereby enhancing export resilience.

Moreover, according to the core tenet of asset portfolio theory, diversity is a prudent strategy to mitigate external risks, epitomized by the adage “Do not put all your eggs in one basket.” From an export standpoint, diversified trade channels are advantageous in mitigating the adverse effects of external shocks (Esposito 2022; He et al. 2022). Kharrazi et al. (2017) explored the significance of network redundancy in trade resilience through an information-theoretic analysis of network flows. They found that network redundancy critically enhances trade resilience.

Furthermore, in today’s crisis-ridden business environment, where trust is waning, a firm’s reputation is highly valued by stakeholders. By accumulating a positive reputation, a firm can serve as a model for others and convey trust to stakeholders, enabling them to acquire reputational capital. This capital aids in mitigating threats stemming from external uncertainty and competition, thereby facilitating better recovery following a downturn in performance (Tracey and French 2017). Consequently, an outstanding corporate reputation is a favorable attribute that shields them against external risks (Liu and Lu 2021).

Board gender diversity and firms’ export resilience

Board gender diversity, export diversity, and firms’ export resilience

Per the fundamental tenets of asset portfolio theory, diversifying investments is a prudent approach to mitigating external risks. Consequently, amidst crisis scenarios, firms adopting diversified export strategies are better positioned to spread risk, enhancing their capacity for swift recovery (He et al. 2022). Against this backdrop, it becomes imperative for boards to deliberate on and implement diversified export strategies.

Drawing upon the resource dependence theory posited by Salancik and Pfeffer (1978), it is evident that directors of various backgrounds bring forth distinct resources that can significantly contribute to a firm’s performance. Female directors, in particular, play a crucial role in fostering diversified modes of thinking within firms (Adams 2016), thus providing significant avenues for firms to access a broad range of resources. Carbonero et al. (2021) illustrated that board gender diversity is associated with an increase in the extensive margins of exports. This phenomenon is primarily attributed to female directors’ compassionate and forgiving nature, which empowers firms to tolerate innovation setbacks better and cultivate a culture conducive to innovation (Chen et al. 2018). This, in turn, facilitates the development of novel products that effectively address consumer needs. In addition, female directors typically possess youth, superior educational backgrounds, and international experience (Carbonero et al. 2021), all of which contribute to their distinctive global perspectives and the identification of unexplored overseas markets, facilitating the development of diversified trading strategies.

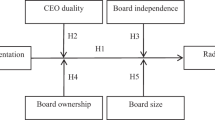

Based on the preceding analysis, it is clear that board gender diversity can introduce diverse products and trade channels to firms. Simultaneously, export diversity can effectively mitigate risks and bolster firms’ export resilience. Therefore, the first hypothesis is formulated as follows:

H1: Board gender diversity enhances firms’ export resilience by extending export diversity.

Board gender diversity, product quality, and firms’ export resilience

In the face of external shocks, the global economic landscape becomes increasingly complex, leading to significant income-level declines across countries. Thus, consumers tend to exercise greater caution and discernment in their purchasing decisions, resulting in a substantial intensification of competition among exporters. Consequently, maintaining high-quality export products becomes a crucial strategic asset for firms to thrive competitively and ensure long-term viability (Wei et al. 2023).

According to stakeholder theory (Parmar et al. 2010), the successful development of firms hinges on fostering positive relationships with stakeholders, including consumers, employees, and suppliers. One of the critical concerns affecting the interests of nearly all stakeholders is product quality. Notably, the sensitivity inherent in women predisposes female directors to exhibit heightened concern for stakeholders’ sentiments (Ardito et al. 2021). Moreover, they possess elevated moral standards and are adept at supervision (Chen et al. 2016; Gul et al. 2011), demonstrating a heightened responsibility toward quality management issues. Consequently, they diligently oversee internal quality controls and implement stringent quality management policies, ensuring that firms maintain excellent product quality (Korenkiewicz and Maennig 2023). This, in turn, mitigates the adverse effects and relationship damage that arise from quality issues.

Based on the analysis presented above, it is clear that female directors demonstrate a heightened sense of responsibility and possess elevated ethical standards, enabling gender-diverse boards to effectively oversee internal quality control processes, resulting in improved product quality. Given the crucial role of product quality in bolstering firms’ export resilience, the second hypothesis is formulated as follows:

H2: Board gender diversity enhances firms’ export resilience by improving the quality of export products.

Board gender diversity, firm reputation, and firms’ export resilience

A firm’s reputation constitutes a valuable asset, capable of attracting increased investor interest, reducing employee turnover, and fostering consumer loyalty. This, in turn, encourages stakeholders to engage in cooperative endeavors, thereby promoting the stable development of the firm (Delgado‐García et al. 2013). Mainly during periods of crisis marked by a lack of trust, a favorable reputation of a firm can serve as a form of insurance against unforeseen shocks (Manabe and Nakagawa 2022), maintaining the regular operation of the firm and the continuity of overseas business. Consequently, this creates a conducive environment for enhancing export resilience.

According to corporate reputation theory (Walker 2010), corporate reputation encompasses an organization’s ability to acquire resources, opportunities, and support by garnering societal recognition for its actions, thus facilitating value creation. Within this framework, the role of boards is crucial, as they serve as the central decision-making body and act as the authoritative entity for communicating signals of corporate development and change to external stakeholders (Pugliese et al. 2009). Brammer et al. (2009) argued that female directors may significantly impact external stakeholders’ perceptions of board functionality. This is because gender-diverse boards are perceived as exemplars of diversity and non-discrimination against women (Van der Walt and Ingley 2003). Adhering to regulatory frameworks enhances legitimacy and fosters a positive reputation (Miller and del Carmen Triana 2009).

In addition, traditionally, traits associated with males include aggressiveness, ambition, and independence, whereas femininity is usually linked with characteristics such as compassion, understanding, and warmth (Eddleston and Powell 2008). The flexible characteristics of women can relieve the tension of stakeholders in the crisis environment to a certain extent, which can effectively improve the evaluation and reputation of their firms (Navarro-García et al. 2022). Therefore, board gender diversity can contribute to enhancing firms’ reputations.

Building on the above analysis, gender-diverse boards have the potential to enhance firms’ reputations by signaling equality and warmth to the external environment. An exemplary corporate reputation can build trust against risks posed by the external environment and bolster firms’ export resilience. Therefore, the third hypothesis is formulated as follows:

H3: Board gender diversity enhances firms’ export resilience by improving corporate reputation.

Data and methodology

Data source and sample

He et al. (2022) defined export resilience as the capacity of an export system to revert to its initial state following exogenous shocks. Consequently, exogenous shocks are indispensable for assessing resilience. Due to the limited availability of firm-level export data from the Chinese Customs database beyond 2015, most studies utilizing this database limit their study period to 2015 (Bai et al. 2017; Ding et al. 2018; Wu et al. 2023). Therefore, this study focuses on exogenous shock events occurring before 2015. Following He et al. (2022), we select the 2008 global financial crisis as a paradigmatic shock event, meeting the criteria for an exogenous shock. This implies that the 2008 export data need to be used as a benchmark for comparative analysis in subsequent years. Thus, the sample period for this study spans from 2009 to 2015.

This study utilizes two primary databases. The first is the Chinese Customs database, curated and maintained by the General Administration of Customs. The second is the China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR) database, a comprehensive repository containing pertinent information on all Chinese A-shares, which is continuously updated.

We follow a three-step procedure to derive empirical samples. Firstly, this study implements the following procedures for the Chinese Customs database: (1) Eliminate samples with missing information to maintain the integrity of subsequent analyses. (2) Address instances of duplicated firm-product-destination-year units due to statistical anomalies by retaining only the units with the largest values among the duplicates. (3) Aggregate the HS eight-digit code data to the HS six-digit level, ensuring consistency in product categorizations throughout the study period, as the Chinese Customs database underwent modifications to product codes in 2007 and 2012.Footnote 1

Secondly, for the CSMAR database, this study employs the following procedures: (1) Eliminate firms categorized under Special Treatment and Particular Transfer to ensure data integrity. (2) Exclude financial firms due to their adherence to distinct regulations and accounting standards compared to other firms. (3) Retain manufacturing firms with industry codes between C13 and C43, as they comprehensively reflect the level and trajectory of Chinese economic development.

Thirdly, following Ding et al. (2018), we identify common variables across the two databases, specifically the firm name and year. By matching these variables, we retain a total of 414 manufacturing firms present in both databases. Since each firm may have hundreds or thousands of transactions detailing exports of specific products to distinct destinations within a given year in the Chinese Customs database, we obtained 47,733 observations at the firm-product-destination-year level for the 414 manufacturing firms.

The basic model

We estimate the following benchmark specification to investigate the impact of board gender diversity on firms’ export resilience:

where i, j, k, t, c, and s denote the firm, export destination, HS six-digit product code, year, city, and industry, respectively. Resili_exportijkt is a firm’s export resilience at the firm-product-destination-year level, with data sourced from the Chinese Customs database (refer to Section “Dependent variable: firms’ export resilience (Resili_export)” for specific calculation methods). GDi2007 denotes the percentage of women on boards as of 2007, representing board gender diversity, with data from the CSMAR database. Two reasons justify selecting only the 2007 board gender diversity as the core explanatory variable. Firstly, from a pragmatic standpoint, experience gained in the lead-up to a shock can effectively equip firms to navigate sudden risks, aiding resilience-building efforts. Secondly, from a methodological perspective, this choice mitigates potential endogeneity concerns arising from the reverse causality between board gender diversity and export resilience. Xi2007 represents the collection of firm-level control variables (refer to Section “Control variables” for comprehensive delineation). Similar to the rationale behind selecting board gender diversity, this study uniformly sets all control variables to their 2007 values, precluding the utilization of firm or firm-year fixed effects. Consequently, this study employs two other fixed effects in the regression analysis. One is \({\varphi }_{{cst}}\), which is at the city-industry-year level. The other is \({\varphi }_{{jt}}\), which captures changes at the destination-year level. \({\varepsilon }_{{ijkt}}\) is the random error term.

We focus on the coefficient α1 of GDi2007, which reflects the impact of board gender diversity on firms’ export resilience. The above analysis predicts that firms with high board gender diversity are conducive to enhancing their export resilience. Consequently, the coefficient α1 should be positive.

Variables and descriptive statistics

Dependent variable: firms’ export resilience (Resili_export)

This study designates the 2008 global financial crisis as the pivotal year of shock. It measures export resilience by examining the deviation between firms’ export values in subsequent years (2009–2015) and their export value in 2008. Consequently, export resilience can only be calculated from 2009 to 2015. The formula for deriving export resilience is as follows:

where the subscripts are identical to those in Eq. (1). \({{\rm{Resili}}\_{\rm{export}}}_{{ijkt}}\) is the export resilience at the firm-product-destination-year level. \({{\rm{value}}}_{{ijk}2008}\) is the export value of firm-product-destination in 2008, \({{\rm{value}}}_{{ijkt}}\) is the export value of firm-product-destination from 2009 to 2015. This study mainly determines the export resilience by comparing the deviation between \({{\rm{value}}}_{{ijk}2008}\) and \({{\rm{value}}}_{{ijkt}}\) in Eq. (2). The smaller the value of \({{\rm{Resili}}\_{\rm{export}}}_{{ijkt}}\), the weaker the firm’s export resilience.

It is crucial to note that, to ensure the comparability of data before (2008) and after (2009–2015), we retain only the export units (firm-product-destination-year) that have records since 2008. Additionally, certain export units may experience periods of intermittency; for example, a firm might have continuous export information in 2009 and 2010, no data in 2011, and then resume in 2012. In such cases, only the initial continuous period is retained in this study.

Independent variable: board gender diversity (GD)

This study employs three measures to assess board gender diversity. Firstly, adopting a relative perspective, we utilize the percentage of women on boards, a method widely utilized in existing literature (Adams 2016; Chen et al. 2019; Carbonero et al. 2021). Secondly, in absolute terms, the total number of women holding director positions within a firm can also indicate the size or representation of women on boards. Thirdly, in considering thresholds, we adhere to the critical mass theory, which suggests that the impact of female directors becomes more significant when their number surpasses three. Consequently, a dummy variable is included in this study to indicate board gender diversity: a firm is assigned a value of one if it has three or more female directors and zero otherwise.

Control variables

Drawing on prior literature (Ding et al. 2018; Zhou and Wen 2022), this study incorporates two categories of control variables. The first category reflects corporate operations and management characteristics, comprising the following variables: ① total factor productivity (TFP), computed according to the method proposed by Ackerberg et al. (2015); ② total assets (TA), represented by the natural logarithm of one plus total assets; ③ return on assets (ROA), calculated as the ratio of net profit to total assets; ④ firm leverage (Leverage), measured by the ratio of total debts to total assets; ⑤ domestic sales rate (Domestic_rate), derived by dividing domestic sales by operating income; ⑥ Tobin’s Q (Q), determined by the replacement cost of assets.

The second category encompasses corporate board characteristics, including: ⑦ board size (Board_size), measured by the natural logarithm of one plus the number of directors; ⑧ CEO duality (CEO_duality), defined as one if the CEO concurrently serves as the chairman of the board, and zero otherwise; and ⑨ the executive gender diversity index (FBLAU), computed following the methodology outlined by Yao et al. (2023). The descriptive statistics of these variables are presented in Table 1, and the data for the control variables are sourced from the CSMAR database.

Empirical results

Baseline results

This study uses the ordinary least squares (OLS) method to examine whether board gender diversity affects firms’ export resilience. Table 2 presents the baseline regression results of Eq. (1). In column (1), only the core independent variable (GD) is introduced, without any control variables. In addition, city-industry-year and destination-year fixed effects are included. The estimated coefficient (α1) of GD is notably positive and statistically significant, suggesting that board gender diversity enhances firms’ export resilience. Moreover, we introduce corporate operations and management variables in column (2) and all the control variables in column (3). Notably, the estimated coefficients (α1) remain significantly positive.

Overall, the sign and significance of the estimated coefficient (α1) show minimal variation, nearly achieving statistical significance at the 1% level across columns (1) to (3), and remain unaffected by the inclusion of control variables. This suggests that board gender diversity can substantially bolster firms’ export resilience and that this effect remains relatively stable across different model specifications.

In column (3), the estimated coefficients are provided for all the control variables. The notably positive coefficient of TFP indicates that higher total factor productivity strengthens export resilience, a conclusion consistent with Melitz (2003). Similarly, a significantly positive coefficient for TA indicates that larger total assets contribute to withstanding risk-taking and enhance firms’ export resilience. The significant positive coefficient of ROA implies that more profitable firms demonstrate enhanced stability in their progression, thereby strengthening their resilience to risk and bolstering their export capabilities. Moreover, an increase in Tobin’s Q indicates a higher return on investment, reflecting robust financial capacity and the ability to withstand risks and enhance export resilience.

In turn, the significantly negative coefficient of CEO_duality indicates that greater CEO power diminishes the likelihood of enhanced export resilience. Similarly, the significantly negative coefficient of FBLAU suggests that gender diversity at the executive level may not be conducive to export resilience. However, the coefficients of Leverage, Domestic_rate, and Board_size do not pass the significance test, indicating that firms’ debt profile, domestic sales rate, and board size do not significantly affect their export resilience.

Robustness checks

Alternative regression samples

In the benchmark regression, we consider the 2008 global financial crisis as an exogenous shock and use data from 2009 to 2015. However, some studies, such as that by Liu and Lu (2021), have noted that the global economy began fully recovering in 2013. This suggests that firms’ export resilience may have been affected by the upward trajectory of the global economic recovery since 2013.

To mitigate such potential impact, we adjust the analysis period from 2009–2015 to 2009–2013 while still utilizing Eq. (1) to conduct a regression analysis. Columns (1) and (2) of Table 3 present the results for the alternative regression samples. In column (1), only the core independent variable (GD) and the city-industry-year and destination-year fixed effects are included, without any control variables. Column (2) expands on column (1) by adding all control variables.

Irrespective of whether the relevant control variables are included, the estimated coefficients of GD remain significantly positive. The findings suggest that board gender diversity is conducive to strengthening firms’ export resilience, regardless of the global economic recovery. Therefore, these results validate the overall reliability of the preceding analysis.

Removing extreme values of board gender diversity (GD)

As evident from the descriptive statistical analysis in Table 1, the study sample reveals that the majority of firms have a relatively low proportion of women on their boards, with an average of only 0.126. A minimum value of 0 indicates that some firms have no female directors, highlighting the commonality of fewer women on boards. Consequently, we excluded the observations with the highest 10% board gender diversity from our sample and then re-estimated Eq. (1). Columns (3) and (4) of Table 3 present the results: column (3) includes only the core independent variable (GD), while column (4) incorporates all control variables.

Regardless of whether the relevant control variables are included, the estimated coefficients of GD remain significantly positive. These consistent findings suggest that board gender diversity is conducive to enhancing firms’ export resilience, even after removing the extreme values. Thus, these results confirm the robustness of our main conclusions.

Alternative measures of board gender diversity (GD)

This study employs three methods to measure board gender diversity (refer to Section “Independent variable: board gender diversity (GD)” for comprehensive delineation). This section incorporates two variables to test robustness from an absolute perspective: (1) the total number of female directors in a firm, with results presented in column (1) of Table 4, and (2) a dummy variable indicating the presence of more than three female directors, with results presented in column (2) of Table 4. Both columns include the same control variables and fixed effects as the baseline regression.

The regression coefficients of board gender diversity remain notably positive, even with the alteration in the measurement method. These findings suggest that the increase in the absolute number of female directors continues to enhance firms’ export resilience. This reaffirms the conclusions drawn from the fiducial regression and serves as evidence in favor of the critical mass theory.

Alternative measures of firms’ export resilience (Resili_export)

To verify the robustness of the conclusions, we adjust the calculation method of export resilience based on two aspects: (1) We calculate Resit_export_1 as the deviation in the export growth rate between 2009–2015 and 2008, with results presented in column (3) of Table 4. (2) We calculate Resit_export_2 as the difference in export values between 2009–2015 and 2008, with results presented in column (4) of Table 4. Both columns include the same control variables and fixed effects as the baseline regression.

According to the regression results obtained using alternative measures of export resilience, the positive impact of board gender diversity on firms’ export resilience remains statistically significant. These findings reaffirm the reliability of the research conclusions presented in this study, demonstrating that board gender diversity plays a crucial role in enhancing firms’ export resilience.

Endogeneity concerns

Despite including various control variables and fixed effects at different levels within the baseline regression model, there is a persistent risk of biased results stemming from omitted variables. For example, factors related to product exports, such as shifting consumer preferences toward imports and the implementation of import restrictions by destinations, are not accounted for in our econometric model. To address these concerns, we employ two approaches: (1) incorporating product-level fixed effects and (2) using an instrumental variable for board gender diversity.

Additional fixed effects

We introduce product-year fixed effects into the baseline regression to account for evolving product characteristics over time. Subsequently, we replace the destination-year fixed effect in the baseline regression with the destination-product-year fixed effect to account for fluctuating product demand across destinations over time.

Columns (1) and (2) of Table 5 present the results after adding product-year fixed effects. Column (1) includes only the core independent variable (GD), while column (2) incorporates all control variables. The findings suggest that the sign and significance of the coefficient for board gender diversity remain stable even after including the product-year fixed effect, regardless of the presence of control variables.

Columns (3) and (4) of Table 5 demonstrate the results after incorporating destination-product-year fixed effects. Column (3) includes only the core independent variable (GD), while column (4) integrates all control variables. The findings indicate that the sign and significance of the coefficient for board gender diversity remain consistent with our primary findings following the inclusion of the destination-product year fixed effect, irrespective of the presence or absence of the control variable.

Instrumental variable regression

A valid instrumental variable must satisfy both the relevance condition and the exclusion restriction. Therefore, we need to identify a variable associated with board gender diversity that influences firms’ export resilience only through its effect on board gender diversity. Gao et al. (2016) suggested that “son preference” in Chinese culture may impact the gender composition of corporate management teams in various regions.

Specifically, the prevalence of filial piety in traditional Chinese society, where elderly care predominantly relies on support from offspring, along with the perception of males as the economic pillars of families, has entrenched the cultural norm of ‘raising sons to provide for old age’ (Liu 2014). Consequently, a preference for sons over daughters has emerged in the Chinese population. Over time, males have assumed an elevated status and significance within the familial context, serving as the exclusive avenue for lineage perpetuation and continuation. This phenomenon is evident in the customary inclusion of sons in family genealogies, while daughters are rarely documented therein (Murphy et al. 2011). The prevalence of traditional ideologies that elevate the status of males contributes to the propensity for male-dominated leadership structures in contemporary settings. In such contexts, this significantly exacerbates the challenge for women to attain leadership positions, hindering progress toward achieving gender diversity on boards.

Hence, the preference for sons over daughters may influence the gender composition of boards. Specifically, in cities where this preference is more pronounced, the social status of males tends to be higher, resulting in fewer female directors being employed within corporations headquartered in such locales. While the traditional preference for sons over daughters is not directly related to the export resilience of firms, it may exert an indirect influence through its impact on board gender diversity. The sex ratio at birth is a viable proxy for the preference for sons (Gao et al. 2016). Therefore, this study utilizes the sex ratio at birth from the 2000 census dataFootnote 2 for each city where firms are located as an instrumental variable for board gender diversity.

Table 6 presents the results of instrumental variable regression utilizing the two-stage least squares (2SLS) method. It should be noted that as the instrumental variable is at the city level, the coefficient of the instrumental variable can be absorbed if we use city-level fixed effects. Therefore, we replace city-industry-year fixed effects with province-industry-year fixed effects. Column (1) presents the findings of the first stage analysis, revealing the relationship between the instrumental variable (sex ratio at birth) and board gender diversity. The coefficient of the instrumental variable exhibits a statistically significant positive relationship at the 1% significance level, suggesting that the sex ratio at birth in a city can influence women’s presence on boards within that locality. Column (2) reports the outcomes of the second-stage regression analysis. In this regression, we utilize the fitted values obtained from the first stage instrumental variable regression to substitute variables representing board gender diversity, thereby analyzing its impact on firms’ export resilience. The coefficient associated with this substitution is statistically significant at the 1% level, suggesting that the sex ratio at birth affects the firm’s export resilience through its influence on board gender diversity. Column (3) directly presents the instrumental variable analysis outcomes on export resilience, representing the reduced regression model. These findings demonstrate that our main conclusions are unaffected by endogeneity issues.

Furthermore, the F-statistic for the first stage is calculated to be 70.403, significantly surpassing the critical value of 10, thus alleviating concerns about weak instrumental variables. The regression results obtained from the instrumental variable analysis indicate that board gender diversity significantly enhances firms’ export resilience, thus affirming the robustness of our main conclusions.

Exploring the underlying mechanisms

Firms’ export product quality

Following the method of Fan et al. (2015), this study utilizes the residual term to calculate product quality, which is determined by the value of the substitution elasticity (σ). To ensure the robustness of our findings, we consider three different values of elasticity (σ) for product quality.Footnote 3 Consequently, we replicate Eq. (1), substituting firms’ export resilience with export product quality values: quality_1, quality_2, and quality_3.

Table 7 presents the results. Column (1) displays the results for the quality of export products (quality_1), computed utilizing the methodology of Tang and Zhang (2012). The results indicate a significant improvement in export product quality attributable to board gender diversity. Comparable outcomes are observed when varying the elasticity value: σ equals 5 (quality_2) in column (2) and σ equals 10 (quality_3) in column (3). These results underscore the capacity of board gender diversity to motivate firms to enhance the quality of their exports, consequently bolstering their export resilience. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is validated and confirmed.

Firms’ export diversity

The extensive margin reflects the network relationship of exports (Besedeš and Prusa 2011), enabling the capture of various export activities (Jongwanich 2020) and serving as a valuable indicator of export diversity. Existing literature delineates the export extensive margins across three dimensions: the number of products, the number of destinations, and the number of destination-product pairs (Melitz 2003). Accordingly, this study computes the three extensive margins and applies the natural logarithm. We replicate Eq. (1), substituting the dependent variables with the three extensive margins: the number of products (product_ex), the number of destinations (desti_ex), and the number of destination-product pairs (desti_product_ex). The natural logarithm is used for all three export diversity variables.

Table 8 presents the regression results. Specifically, columns (1)–(3) display the results for product_ex, desti_ex, and desti_product_ex, respectively. Across these columns, the estimated coefficient for board gender diversity consistently displays a significantly positive association. These findings provide compelling evidence that board gender diversity contributes to augmenting firm export diversity across different dimensions. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is robustly supported and confirmed.

Firms’ reputation

Drawing on the framework proposed by Guan and Zhang (2019), this study adopts a comprehensive approach to evaluate corporate reputation, incorporating assessments from diverse stakeholders while ensuring operational feasibility and relative comprehensiveness. Subsequently, we select 12 indicators for evaluating corporate reputationFootnote 4. Utilizing factor analysis, we calculate an integrated firm’s reputation score based on these indicators. Finally, the firms’ reputation scores are categorized into ten groups, spanning from low to high, with each group assigned a corresponding value from 1 to 10.

The reputation score (fame_score) and reputation ranking level (fame_level) are proxy variables for firms’ reputations. Subsequently, we replicate Eq. (1), substituting firms’ export resilience with their reputation. Columns (1)–(2) of Table 9 present the results for fame_score and fame_level, respectively. Across these columns, the estimated coefficients for board gender diversity consistently exhibit significantly positive associations. These findings conclusively demonstrate that board gender diversity can positively impact firms’ reputations, enhancing their export resilience. Consequently, Hypothesis 3 is robustly supported and confirmed.

Heterogeneity analysis

Heterogeneity at the firm level

Firm age

Age can indicate a firm’s viability in overseas markets, where export resilience is crucial to long-term survival. Older firms often boast mature management structures and extensive production experience, contributing to their relatively stable position in foreign markets. In contrast, younger firms may encounter challenges such as an unstable customer base and limited production experience. Given the demonstrated capacity of board gender diversity to foster firms’ export resilience, coupled with the inherent resilience of older firms, it is reasonable to speculate that board gender diversity can significantly enhance the export resilience of older firms.

This study utilizes Age to represent firm age and constructs an interaction term between board gender diversity (GD) and firm age (Age). Firms are then divided into two groups: those with an age value of 1 when the firm age is higher than the sample average and 0 otherwise. The regression analysis focuses on the interaction term results. Column (1) in Panel A of Table 10 shows the estimated coefficient for the interaction term, which is significantly positive. This indicates that older firms with a higher board gender diversity have a more pronounced impact on their export resilience.

Board educational level

Learning is undoubtedly challenging, requiring individuals to overcome numerous obstacles to attain higher education degrees, cultivating greater resilience. Consequently, board members with higher levels of education are likely to exhibit increased resilience, empowering them to navigate corporate challenges more effectively. Additionally, as education improves, individuals’ critical thinking and analytical skills are honed, allowing them to approach challenges objectively and think beyond conventional paradigms. Therefore, increased educational attainment tends to foster an awareness of societal injustices, particularly regarding gender discrimination, promoting a predisposition to embrace principles of equality and diversity. Thus, we expect that board gender diversity in firms with highly educated boards can have a more prominent impact on their export resilience.

This study employs Education as a proxy for the educational level of boards, which is computed as the average educational attainment across all board members within a firm. A higher Education value indicates a higher level of educational background.Footnote 5 Subsequently, an interaction term is constructed between board gender diversity (GD) and the educational background of the board (Education) to analyze this heterogeneity. The findings are presented in column (2) of Panel A in Table 10. The estimated coefficient of the interaction term is positive and statistically significant, aligning with our expectations. This suggests that the influence of board gender diversity on export resilience is more pronounced in firms with higher levels of board education.

Heterogeneity at the province level

Degree of non-state economic development

Amid the diversification of Chinese firms, entities with diverse ownership structures have emerged as indispensable complements to the state-owned economy. They play a crucial role in harnessing the enthusiasm of all stakeholders and catalyzing productivity development. This diversified landscape fosters fair competition and creates an environment conducive to innovation and efficiency, thereby driving overall economic growth.

Regions with more policies to encourage non-state economic development are generally more open-minded. In such environments, firms tend to experience accelerated growth, fostering a dynamic and vibrant market landscape. Firms with women on boards, representing diverse corporate leadership, tend to thrive in these inclusive settings. Therefore, we anticipate that in provinces with a rapidly developing non-state economy, the promotion of export resilience can be more pronounced with an increase in the proportion of women on boards within a firm.

This study employs non_state as a proxy for the degree of non-state economic development in provinces, derived from the sub-index of non-state economic development in the marketization index (Wang et al. 2019). A higher value indicates a faster pace of non-state economic development. Subsequently, an interaction term between board gender diversity (GD) and non-state economic development (non_state) is constructed to analyze this heterogeneity. The results are reported in column (1) of Panel B in Table 10. The estimated coefficient of the interaction term shows a significantly positive association, consistent with our expectations. This implies that the impact of board gender diversity on export resilience is more pronounced in firms situated in provinces undergoing rapid non-state economic development.

Degree in product market development

The degree to which commodity prices are subject to market forces tends to be higher in environments where product markets develop robustly, reflecting a fundamental aspect of fair market competition. In such contexts, firms are more likely to advocate for fairness. However, augmenting the representation of women on boards is crucial for fostering gender equality within firms. Consequently, we anticipate that in such environments, firms may be more inclined to adopt measures that promote equality, thereby fostering board gender diversity and subsequently enhancing firms’ export resilience.

This study employs product_market as a proxy for the degree of product market development in provinces, derived from the sub-index of factor market development in the marketization index (Wang et al. 2019). A higher value indicates a faster pace of product market development. Subsequently, an interaction term between board gender diversity (GD) and product market development (product_market) is constructed to analyze this heterogeneity. The results are presented in column (2) of Panel B in Table 10. The estimated coefficient of the interaction term demonstrates a significantly positive association, aligning with our anticipated. This implies that the influence of board gender diversity on export resilience is more prominent in firms located in provinces undergoing higher levels of product market development.

Conclusions

In this study, we investigate the impact of board gender diversity on firms’ export resilience and explore the underlying mechanisms. Initially, we merge the Chinese Customs database with the CSMAR database using firm names and years, resulting in a sample of Chinese A-share listed firms with export information. We designate the 2008 global financial crisis as an external shock event during the sample period and calculate firms’ export resilience accordingly. Our empirical analysis indicates that board gender diversity significantly enhances firms’ export resilience. This conclusion remains robust after several tests, including sample substitution, outlier removal, adjustments in core variable measurement methods, and the use of fixed effects and an instrumental variable to address endogeneity concerns. Mechanism analyses reveal that board gender diversity contributes to expanding export diversity, enhancing the quality of export products, and improving corporate reputation. These are critical pathways for bolstering firms’ export resilience.

Additionally, this study examines the heterogeneity in the impact of board gender diversity on firms’ export resilience at both the firm and provincial levels, considering factors such as firm age, board educational level, degree of non-state economic development, and product market development. Our heterogeneity analyses suggest that the beneficial impact of board gender diversity on firms’ export resilience is more pronounced in older firms and those with higher levels of board educational backgrounds. Moreover, this effect is accentuated in firms located in provinces characterized by higher levels of non-state economic and product market development. This study reveals that board gender diversity is a crucial factor in effectively enhancing firms’ export resilience, underscoring its significant importance for firm development, particularly during times of crisis.

These insights also suggest implications for the development of the board structure. Firstly, firms should take appropriate measures, such as implementing transparent selection procedures or expanding candidate search pools, to enhance the participation of women on boards and actively capitalize on their strengths. This benefits corporate governance improvements and strengthens firms’ resilience to risks. Secondly, enhanced leadership training for women is essential. Firms can offer targeted training and mentoring programs to assist female employees in developing the skills and experience necessary to excel in leadership roles. Thirdly, governments can facilitate the creation of a more equitable business environment by encouraging the development of non-state economies and promoting greater marketization of production factors. This can guide firms towards a more equitable and inclusive approach to board gender diversity, enabling the full exploitation of the advantages offered by female directors within the firm.

However, like all studies, this study has limitations that could potentially guide future research directions. Firstly, the focus on Chinese A-share listed firms may limit the generalizability of the conclusions. Future research could broaden its scope by examining larger samples and incorporating export data from multinational firms for validation purposes. Secondly, corporate governance in China involves not only the board of directors but also the supervisory board. Future research could investigate whether gender diversity in supervisory boards also affects firms’ export resilience, representing an intriguing avenue for exploration. Thirdly, this study measures export resilience concerning a specific external shock, limiting the choice of the study’s timeframe. However, shocks represent extreme points within an environment of uncertainty, which is the norm in economic operations. Therefore, future research could expand resilience measurement within the context of environmental uncertainty.

Data availability

The data utilized in this study predominantly originates from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR) database. The authors have not been authorized to disclose the database. Access to the data is available through the institute upon permission for researchers’ requests: https://data.csmar.com/.

Notes

We use the conversion table from the United Nations Comtrade to convert HS eight-digit product codes into HS six-digit levels.

The formula for calculating the sex ratio at birth in the census data is the ratio of baby boys to baby girls, reflecting the degree of preference for sons in various cities. We analyze the impact of board gender diversity on firms’ export resilience. To facilitate the analysis, we adopt the processing methodology outlined by Gao et al. (2016), wherein we compute the reciprocal of the sex ratio at birth and adjust it to reflect the ratio of baby girls to baby boys.

This study employs three values of product substitution elasticity (σ) to calculate the quality of export products. First, Broda and Weinstein (2006) provide product substitution elasticity (σ) at the HS 10-digit level. To preserve the maximum number of samples, we follow Tang and Zhang’s (2012) method to calculate the value of product substitution elasticity (σ) at the HS two-digit code level. Specifically, as one HS two-digit code may correspond to multiple HS six-digit codes. Hence, we compute the product quality using the same product substitution elasticity (σ) at the HS two-digit level. Second, Head and Ries (2001) and Anderson and van Wincoop (2004) assert that the reasonable range of σ is [5,10]. Following these assertions, Fan et al. (2015) directly use σ equals to 5 and 10 to estimate product quality. Consequently, we consider σ = 5 and σ = 10 to recalculate the product quality.

These indicators encompass a variety of perspectives, including: the ranking of corporate assets, income, net profit, and industry value from the standpoint of consumers and society; the asset-liability ratio, current ratio, and long-term debt ratio; earnings per share, dividends per share from the viewpoint of shareholders, whether audited by the international “Big Four” accounting firms; sustainable growth rate from the corporate perspective, and the proportion of independent directors. The data for these variables is sourced from the CSMAR database.

There are five kinds of degrees in the CSMAR databases including: (1) Technical secondary school and below; (2) Junior college; (3) Undergraduate; (4) Postgraduate and Master of Business Administration (MBA), and Executive Master of Business Administration (EMBA); (5) PhD student. We assign these education backgrounds on a scale of 1 to 5. The higher the value, the higher the level of the educational background.

References

Ackerberg DA, Caves K, Frazer G (2015) Identification properties of recent production function estimators. Econometrica 83(6):2411–2451. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA13408

Adams RB (2016) Women on boards: the superheroes of tomorrow? Leadersh Q 27(2):371–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.11.001

Ain QU, Yuan X, Javaid HM et al. (2021) Female directors and agency costs: evidence from Chinese listed firms. Int J Emerg Mark 16(8):1604–1633. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-10-2019-0818

Amorelli MF, García‐Sánchez IM (2023) Leadership in heels: women on boards and sustainability in times of COVID‐19. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 30(4):1987–2010. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2469

Anderson JE, van Wincoop E (2004) Trade costs. J Econ Lit 42(3):691–751. https://doi.org/10.1257/0022051042177649

Ardito L, Dangelico RM, Messeni PA (2021) The link between female representation in the boards of directors and corporate social responsibility: evidence from B corps. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 28(2):704–720. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2082

Azeem N, Ullah M, Ullah F (2023) Board gender diversity and firms’ financial resilience during the Covid-19 pandemic. Financ Res Lett 58:104332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2023.104332

Bai X, Krishna K, Ma H (2017) How you export matters: export mode, learning and productivity in China. J Int Econ 104:122–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2016.10.009

Besedeš T, Prusa TJ (2011) The role of extensive and intensive margins and export growth. J Dev Econ 96(2):371–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.08.013

Brammer S, Millington A, Pavelin S (2009) Corporate reputation and women on the board. Br J Manag 20(1):17–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2008.00600.x

Broda C, Weinstein DE (2006) Globalization and the gains from variety. Q J Econ 121(2):541–585. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2006.121.2.541

Calı M, Ghose D, Montfaucon AFL et al. (2022) Trade policy and exporters’ resilience: evidence from Indonesia. Policy Research Working Paper Series 10068

Carbonero F, Devicienti F, Manello A et al. (2021) Women on board and firm export attitudes: evidence from Italy. J Econ Behav Organ 192:159–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2021.10.011

Carter DA, Simkins BJ, Simpson WG (2003) Corporate governance, board diversity, and firm value. Financ Rev 38(1):33–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6288.00034

Carter ME, Franco F, Gine M (2017) Executive gender pay gaps: the roles of female risk aversion and board representation. Contemp Acc Res 34:1232–1264. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12286

Chen J, Leung WS, Song W et al. (2019) Why female board representation matters: the role of female directors in reducing male CEO overconfidence. J Empir Financ 53:70–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jempfin.2019.06.002

Chen S, Ni X, Tong JY (2016) Gender diversity in the boardroom and risk management: a case of R&D investment. J Bus Ethics 136(3):599–621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2528-6

Chen J, Leung WS, Evans KP (2018) Female board representation, corporate innovation and firm performance. J Empir Financ 48:236–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jempfin.2018.07.003

Cumming D, Leung TY, Rui O (2015) Gender diversity and securities fraud. Acad Manag J 58(5):1572–1593. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0750

Delgado‐García JB, Quevedo‐Puente DE, Díez‐Esteban JM (2013) The impact of corporate reputation on firm risk: a panel data analysis of Spanish quoted firms. Br J Manag 24(1):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2011.00782.x

Ding H, Fan H, Lin S (2018) Connect to trade. J Int Econ 110:50–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2017.10.004

Dupire M, Haddad C, Slagmulder R (2022) The importance of board risk oversight in times of crisis. J Financ Serv Res 61(3):319–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-021-00364-x

Eddleston KA, Powell GN (2008) The role of gender identity in explaining sex differences in business owners’ career satisfier preferences. J Bus Ventur 23(2):244–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.11.002

Esposito F (2022) Demand risk and diversification through international trade. J Int Econ 135:103562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2021.103562

Fan H, Li YA, Yeaple SR (2015) Trade liberalization, quality, and export prices. Rev Econ Stat 97(3):1033–1051. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00524

Wang XL, Fan G, Hu LP (2019) Marketization Index Report of Chinese Provinces (2018). Beijing: Social Sciences Academic

Gao H, Lin Y, Ma Y (2016) Sex discrimination and female top managers: evidence from China. J Bus Ethics 138:683–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2892-x

García CJ, Herrero B (2021) Female directors, capital structure, and financial distress. J Bus Res 136:592–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.07.061

Gnangnon SK (2021) Productive capacities, economic growth and economic growth volatility in developing countries: does structural economic vulnerability matter? J Int Commer Econ Policy 2550001. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1793993325500012

Gnangnon SK (2022) Development aid and export resilience in developing countries: a reference to aid for trade. Economies 10(7):161. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10070161

Guan K, Zhang R (2019) Corporate reputation and earnings management: effective contract view or rent-seeking view. Account Res 1:59–64

Gul FA, Srinidhi B, Ng AC (2011) Does board gender diversity improve the informativeness of stock prices? J Account Econ 51(3):314–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2011.01.005

He C, Chen T, Zhu S (2022) Do not put eggs in one basket: related variety and export resilience in the post-crisis era. Ind Corp Change 30(6):1655–1676. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtab044

Head K, Ries J (2001) Increasing returns versus national product differentiation as an explanation for the pattern of US–Canada trade. Am Econ Rev 91(4):858–876. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.91.4.858

Hu X, Li L, Dong K (2022) What matters for regional economic resilience amid COVID-19? Evidence from cities in Northeast China. Cities 120:103440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103440

Jongwanich J (2020) Export diversification, margins and economic growth at the industrial level: evidence from Thailand. World Econ 43(10):2674–2722. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12921

Kharrazi A, Elena R et al. (2017) Network structure impacts global commodity trade growth and resilience. PLoS ONE 12(2):e0171184. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171184

Korenkiewicz D, Maennig W (2023) Women on a corporate board of directors and consumer satisfaction. J Knowl Econ 14(4):3904–3928. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-022-01012-y

Liu J (2014) Ageing, migration and familial support in rural China. Geoforum 51:305–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.04.013

Liu M, Lu W (2021) Corporate social responsibility, firm performance, and firm risk: the role of firm reputation. Asia Pac J Account Econ 28(5):525–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/16081625.2019.1601022

Manabe T, Nakagawa K (2022) The value of reputation capital during the COVID-19 crisis: evidence from Japan. Financ Res Lett 46:102370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2021.102370

Martin R (2012) Regional economic resilience, hysteresis and recessionary shocks. J Econ Geogr 12(1):1–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbr019

Melitz MJ (2003) The impact of trade on intra‐industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica 71(6):1695–1725. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0262.00467

Mena C, Antonios K et al. (2022) International trade resilience and the Covid-19 pandemic. J Bus Res 138:77–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.08.064

Miller T, del Carmen Triana M (2009) Demographic diversity in the boardroom: mediators of the board diversity–firm performance relationship. J Manag Stud 46(5):755–786. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00839.x

Murphy R, Tao R, Lu X (2011) Son preference in rural China: patrilineal families and socioeconomic change. Popul Dev Rev 37(4):665–690. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00452.x

Navarro-García JC, Ramón-Llorens MC, García-Meca E (2022) Female directors and corporate reputation. Bus Res Q 25(4):352–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/2340944420972717

Parmar BL, Freeman RE, Harrison JS et al. (2010) Stakeholder theory: the state of the art. Acad Manag Ann 4(1):403–445. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2010.495581

Papangkorn S, Chatjuthamard P, Jiraporn P et al. (2021) Female directors and firm performance: evidence from the Great Recession. Int Rev Financ 21(2):598–610. https://doi.org/10.1111/irfi.12275

Pugliese A, Bezemer PJ, Zattoni A et al. (2009) Boards of directors’ contribution to strategy: a literature review and research agenda. Corp Gov Int Rev 17(3):292–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2009.00740.x

Reggiani A, Graaff TD, Nijkamp P (2002) Resilience: an evolutionary approach to spatial economic systems. Netw Spat Econ 2(2):211–229. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015377515690

Salancik GR, Pfeffer JA (1978) Social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Adm Sci Q 224–253. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392563

Seebeck A, Vetter J (2021) Not just a gender numbers game: how board gender diversity affects corporate risk disclosure. J Bus Ethics (2):1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04690-3

Shamsudin SM, Suffian MTM, Rahman LA (2022) The effect of board diversity and corporate performance in Malaysia: pre-and during COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Acad Res Account Financ Manag Sci 12(2):525–536. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARAFMS/v12-i2/14114

Tang H, Zhang Y (2012) Quality differentiation and trade intermediation. SSRN 2368660. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2368660

Tracey N, French E (2017) Influence your firm’s resilience through its reputation: results won’t happen overnight but they will happen! Corp Reput Rev 20:57–75. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41299-017-0014-7

Van DB, Jaarsma M (2017) What drives heterogeneity in the resilience of trade: firm‐specific versus regional characteristics. Pap Reg Sci 96(1):13–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12233

Van der Walt N, Ingley C (2003) Board dynamics and the influence of professional background, gender and ethnic diversity of directors. Corp Gov Int Rev 11(3):218–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8683.00320

Walker KA (2010) Systematic review of the corporate reputation literature: definition, measurement, and theory. Corp Reput Rev 12:357–387. https://doi.org/10.1057/crr.2009.26

Wang Z, Wei W (2021) Regional economic resilience in China: measurement and determinants. Reg Stud 55(7):1228–1239. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1872779

Wei YY, Yue W, Han J (2023) Regional trade agreements and enterprise export resilience. Contemp Financ Econ 0(4):106–117. http://cfejxufe.magtech.com.cn/ddcj/EN/Y2023/V0/I4/106

Willhans L, Kossmann LL (2022) Female leaders during crisis: a study about the impact of female board directors on firms’ financial performance during the Covid-19 pandemic (Dissertation). https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-479369

Wowak KD, Ball GP, Post C et al. (2021) The influence of female directors on product recall decisions. Manuf Serv Oper Manag 23(4):895–913. https://doi.org/10.1287/msom.2019.0841

Wu H, Li J, Zhao Y (2023) Foreign demand shocks, product switching, and export product quality: evidence from China. World Econ 46(1):276–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.13307

Xu C, Liu H (2023) Export tax rebates and enterprise export resilience in China. J Int Trade Econ Dev 32(6):953–972. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638199.2022.2141827

Yao S, Zhang WW, Fan L (2023) Mixed-gender analyst team and accuracy of earnings forecast: evidence from China. Appl Econ 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2023.2177603

Ye D, Deng J, Liu Y et al. (2019) Does board gender diversity increase dividend payouts? Analysis of global evidence. J Corp Financ 58:1–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2019.04.002

Zhou F, Wen H (2022) Trade policy uncertainty, development strategy, and export behavior: evidence from listed industrial companies in China. J Asian Econ 82:101528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2022.101528

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Jiangsu Provincial Social Sciences Foundation General Project, Grant/Award Number: 23EYB008; the Jiangsu Provincial Dual Innovation Doctoral Project, Grant/Award Number: JSSCBS20210838; the Basic Research Funds for Central Universities Special Fund Project, Grant/Award Number: JUSRP121093.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yunyan Wei conceived the research concept, processed the data, wrote and revised the manuscript, and supervised the research outcomes and the final writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study is designed to provide an objective, honest, and unbiased review. This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, Y. Gender matters: board gender diversity and firms’ export resilience. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 766 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03291-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03291-z

This article is cited by

-

Green innovation and firms’ export resilience: evidence from China

Review of World Economics (2026)