Abstract

Internal factors-such as psychological traits or individual attitudes-relate to and explain political cleavages. Yet, little is known about how locus of control, agency, and modal attitudes impact political ideology. Utilizing textual analysis within the context of the Chilean 2015 constituent process, we go beyond traditional survey methods to explore community clusters in “Values” and “Rights” networks built upon the deliberation of 106,000 people. Our findings reveal distinct attitudinal patterns across political orientations: the progressive left generally exhibits a more propositive and non-agentic attitude, the traditional left adopts an evaluative stance towards values, and the right-wing community leans towards a factual attitude but shifts to an evaluative stance when discussing rights. These results underscore the role of psychological constructs in shaping political ideologies and introduce textual analysis as a robust tool for psychological and political inquiry. The study offers a comprehensive understanding of the complexities of political behavior and provides a new lens through which to examine the psychology of political ideology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In an era characterized by political polarization and social unrest, the rise of the New Left offers a compelling lens through which to explore the psychological traits that shape political affiliations. The grassroots movements led by Bernie Sanders in the United States and “Podemos” in Spain serve as illustrative examples, each attracting individuals with distinct psychological profiles. In the United States, Bernie Sanders’ campaigns have galvanized individuals with a strong sense of agency, who believe that their actions can effectuate societal change (Bandura 2006; Smyth 2018). This aligns with the broader understanding that a sense of agency, often associated with an internal locus of control, can significantly influence political engagement (Smyth 2018).

"Podemos” has similarly attracted individuals with a strong sense of agency in Spain. This is consistent with the broader academic consensus that enduring psychological differences, such as openness to new experiences, significantly influence political participation and ideological affiliation (Mondak 2010; Sibley et al. 2012).

In Chile, the “Frente Amplio” has led massive social protests, advocating for constitutional reform and greater social equality. This movement has garnered attention for attracting individuals with a collective sense of agency and a focus on social justice. This is particularly relevant as we aim to compare our findings about this group with traditional left and right political affiliations in Chile (González et al. 2008; Torcal and Mainwaring 2003).

A pressing question emerges from this setting: How do individual psychological traits like sense of agency differentiate among affiliations with the New Left, traditional left, and traditional right political parties in Chile?

To delve deeper into this complex interplay of psychological constructs and political ideology, we turn to innovative methodologies that go beyond traditional survey-based approaches, which often struggle with inherent biases, such as socially desirable responding (an exceedingly positive self-description), acquiescent responding (tendency to agree with statements regardless of their contents), and extreme responding (tendency to use the extreme choices on a rating scale). All of these tendencies may vary between individuals because of differences in personality, turning themselves into confounding variables (Paulhus et al. 2007).Footnote 1

In recent years, text analysis has emerged as a promising avenue for psychological inquiry. Particularly, the “psychological language analysis” approach posits that our language serves as a mirror reflecting our psychological states (Boyd and Schwartz 2021). This foundational premise has led scholars to validate the efficacy of language in deducing psychological states across various domains, including neuropsychology and political behavior (Kacewicz et al. 2014; Vine et al. 2020).

However, the prevailing “words as attention” paradigm in text analysis may limit our understanding of the nuanced relationship between language and psychology (Boyd and Schwartz 2021). Responding to a growing call for a more expansive approach, we aim to go beyond mere description to explore the underlying motivations behind linguistic patterns. Guided by the principle that “our words echo our thoughts” (Pennebaker et al. 2014), we shift our focus from content to linguistic structures.

This shift is particularly relevant in the current digital age, where the rise of social movements and the proliferation of communication platforms have revolutionized how political agency is perceived and exercised. In this new landscape, political agency has evolved to adopt a more multiplex view, considering the specific contexts and power dynamics inherent in communication processes (Kavada 2016). This shift is further influenced by a systems worldview, which moderates the relationship between agency and civic engagement (Moore et al. 2016; Rosen and Salling 1971).

Our research is set against the backdrop of the Chilean 2015 constituent process boosted by digital technologies, a largely uncharted territory in this field (Raveau et al. 2022a, b, 2023). We analyze community clusters in co-ocurrence networks of “Values” and “Rights” based on the data gathered in the participatory phase of this process. Using these clusters we seek to uncover the linguistic fingerprints that are indicative of specific political orientations. Notably, we find that these community clusters exhibit a high level of agreement in their decisions, emphasizing the role of texts that come from a group discussion, as valid markers for individual political ideology.

In summary, this paper aims to weave together these diverse threads—ranging from the psychology of modal attitude of control and agency to the digital transformation of political engagement and the emerging methodologies in text analysis. We aim to understand how individual psychology shapes political ideology. Through our multi-faceted approach, we aspire to contribute to the evolving discourse on the psychology of political behavior.

Context

After the return to democracy in 1990, under a binomial electoral system two large coalitions dominated the political landscape. The right-wing coalition was formed by two parties, “Renovación Nacional” (RN) and the “Unión Democrática Independiente” (UDI). The leftist coalition was composed by the centrist “Partido Demócrata Cristiano” (PDC), the center-left “Partido por la Democracia” (PPD) and the leftist “Partido Socialista” (PS), and other smaller parties (González et al. 2008). According to Torcal and Mainwaring (2003), although this political division had a social component, the Chilean party system also exhibited a powerful democratic/authoritarian cleavage, an effect from the previous authoritarian period.

The right-wing coalition, comparable to the Republican Party in the USA, and potentially aligning with center-right or right-wing parties such as the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) in Germany or the Conservative Party in the UK, maintained free-market economics and social conservative agendas. Conversely, the leftist coalition, similar to the Democratic Party in the USA, and possibly aligning with center-left or left-wing parties like the Social Democratic Party (SPD) in Germany or the Labour Party in the UK, advocated for social liberal policies. These comparisons, while not perfect matches due to variations in political landscapes and ideologies across countries, offer a rough parallel to the described coalitions based on general ideological tendencies.

The rise of the New Left in Chile dates to the student uprisings in the country in 2011. As this generation entered into politics, it became a relevant political movement: the “Frente Amplio” (Titelman 2023). This was occurring at the time of the Constituent Process of 2015-2016 (when, incidentally, a new more proportional electoral system was established in the country), and thus our data allows us to chart the defining features of this group as it gained political representation. We contrast these features to those of the two aforementioned coalitions, which we called the traditional left-wing and right-wing parties. Regarding the center-right parties at this time there were already parties with a liberal tendency, such as “Evolución Política” who did not form a separate coalition but rather joined the right-wing coalition. The liberalization of the right-wing coalition may have left open a window of opportunity to the appearance of a new conservative party, which is exactly what happened. In 2019, the “Partido Republicano Chileno” was founded, filling this newly emerging conservative niche.

The 2015–2018 constituent process was implemented by former president Michelle Bachelet during her second term in office. The new process was open to citizens, incorporating public discussion on constitutional issues. The first stage of the process was the participatory stage, which began with an individual consultation on a website set up for this purpose. Then group meetings were held, in which different actors -citizens, social organizations, political movements, etc.- were invited to deliberate on constitutional issues (Jordán et al. 2016). This stage considered three levels of participation: local, provincial, and regional. Local encounters were called “self-convened local meetings” (ELAs, in its Spanish acronym). The ELAs consisted of groups of between 10 and 30 people, Chileans and foreign residents over 14 years of age, and took place in various local settings. Provincial and regional meetings were also open to citizens but organized by local authorities. A total of 8113 ELAs were held, involving over 106,412 people. Because participation was voluntary, the groups were not fully representative (Raveau et al. 2022a).

The citizen consultation mechanism, both for individual consultation and for local, provincial and regional meetings, consisted of a selection of concepts that the new constitution should include, regarding four dimensions: (i) Values and Principles; (ii) Rights; (iii) Duties and responsibilities; and (iv) State Institutions. For each dimension, participants were given a list of concepts to consider and were asked to choose up to seven concepts collectively (or propose new ones), providing reasons for their choices after a deliberative process, which included a three-level variable–agreement, partial agreement, or disagreement to measure the group’s consensus on each selected concept (SEGPRES 2016). The data gathered in this process was later sent to the Constitutional Systematization Committee. The result of these stages was the preparation of the “Citizen Bases for the new Constitution”. These bases would serve as the foundation for a constitutional reform project aimed at modifying the Political Constitution of the Republic, which was presented by Bachelet to the Senate. Although President Bachelet’s constitutional reform project presented to the Senate in 2018 did not come to fruition, there are elements to appreciate in the locally self-convened meetings that contributed to the project. These gatherings served as valuable inputs, fostering grassroots engagement and allowing diverse voices to be heard in the constitutional reform process. Despite the ultimate outcome, the initiative highlighted the importance of bottom-up participation in shaping democratic institutions and policies.

Data

The dataset we use consists of spreadsheets for Values and for Rights, both gathered from the ELAs.Footnote 2 Each spreadsheet contains as many rows as concepts (values or rights, depending on the case) were chosen across all ELAs. Each row includes the concept name, the ELA’s id, the commune in which the encounter took place, the three-level agreement variable and the text that justifies the concept selection. During the systematization processes, the following columns were added: a normalized version of the text, a syntagm decomposition and a variable that accounts for the modal attitude, which we use later. The raw spreadsheets (before systematization) are publicly available at http://archivospresidenciales.archivonacional.cl/index.php/doc-10. In this work, we have used the final version, provided by the systematization team.Footnote 3 After removing blank text entries, the Values databases has 46,660 rows, with a total of 971,849 words, and a average of 20.8 word per sentence. The Rights database has 45,094 rows, 925,317 words, and an average of 20.5 words per sentence.

In order to help the interpretation of the results, here we use a classification of rights into three generations, proposed by Vasak (1977). First-generation rights are negative rights that emphasize political and civil liberties. Here, the role of the state is to respect and ensure the rights of individuals, such as equality before the law, the right to life, the freedom of movement, worship, work, education, and entrepreneurship. Second-generation rights are positive rights that promote equality and advocate the state’s active participation to this end. Second-generation rights include social and economic rights, such as the right to education, healthcare, and social security. Unlike first and second generation rights, third-generation rights have a collective or solidarity nature (Domaradzki et al. 2019; Vasak 1977).Footnote 4

Our data comes from group decisions, not individuals. However, these groups were likely homogeneous due to the voluntary nature of the ELAs. Most ELAs reached a high level of agreement on the selected Values and Rights, supporting this assumption. Specifically, 90.6% (8.9% partial agreement, 0.5% disagreement) of ELAs agreed on Values and 92.1% (7.4% partial agreement, 0.5% disagreement) on Rights, with very few showing disagreement.

Methodology

The goal of this work is to explore the relationship between language and psychology, between different political communities in Chile. To achieve this, we must at first discriminate among texts from different political orientations. Since the participatory phase of the constituent process did not gather personal information about political identification, we had to infer it from the concept selection. Based on Raveau et al. (2022b), by using network-based methods we found communities of concepts that are usually selected together, which can be identified with actual political conglomerates in Chile. In this way, we can relate texts with political communities, for each community consists of a set of concepts and each concept is associated with a set of texts. Then, we apply NLP techniques to extract linguistic features of those texts, to finally build a model to estimate the likelihood of a text belonging to a particular ideological cluster. Jointly, these methodologies complement each other and provide the basis for our analysis.

The methodology integrates the disciplines of network science, natural language processing, and political science to investigate ideological communities within political networks. The approach consists of three primary components: 1) Network Mapping and Community Detection. 2) Linguistic Feature Extraction. 3) Discrete Choice Modeling. These components are designed to study linguistic features with network-cluster membership, thereby offering a multidisciplinary lens to study political ideologies.

Identification of ideological communities

We employ co-occurrence networks to map ideological communities, following established methods in network science (Candia et al. 2019; Lyra et al. 2021; Raveau et al. 2022b). The networks are constructed using an M × N incidence matrix A = a(i, j), where M is the number of ELAs and N is the number of concepts for a given dimension, such as Rights or Values. The phi-correlation coefficient ϕ(i, j) is used to measure the distance between concepts i and j (Onnela et al. 2003; Read and Vidakovic 2006). Given that the phi-correlation coefficient is distributed χ2 (with one degree of freedom), we test the significance of the association (Candia et al. 2019). If ϕij is significant at the 95% confidence level, it adds a link between concepts i and j with weight 1 − d where d is the distance between concepts i and j (Onnela et al. 2003).

To discover the structure of the ideology by identifying highly connected groups of concepts–or communities–inside these networks, we use community detection (Newman 2006) using the Louvain algorithm (Blondel et al. 2008). For a detailed explanation of the mathematical formulations and statistical tests, see Supplementary Material Section S1.

Linguistic feature extraction

We extract text-based features from original texts in Spanish, encompassing different linguistic frameworks: lexical variables (text length and Categorical-Dynamic Index), semiotic analysis (agency, multidimensionality), modal analysis (modal attitude), and functional analysis (type of process). The methods employ standard LIWC (Pennebaker et al. 2015) and Stanford CoreNLP packages (Chen and Manning 2014; Manning et al. 2014; Toutanova et al. 2003) for automated analysis. Here we describe the main variables (agency, modal attitude, type of process). The remaining variables are briefly reported in “Additional Features” (for more details, refer to Supplementary Material Section S2).

Agency/Determinism

Central to this methodology are agency and modal attitude. Agency reflects whether the action implies individual/collective participation or if it is driven by external forces outside of human control. We hypothesize that agency will be related to political orientation because the locus of control is (Rotter 1966; Sweetser 2014). Both variables - agency and locus of control - try to determine the agent’s degree of control or responsibility over the events. However, while the locus of control implies a specific instrument to assess personal beliefs or attitudes, agency refers to objectifiable linguistic behavior derived directly from the speech act. Agency is assessed through the Stanford CoreNLP packages, particularly the POS Tagger and the Dependency Parser tools (Chen and Manning 2014; Manning et al. 2014; Toutanova et al. 2003).

The method employs a metric for assessing the text’s level of agency. This metric categorizes the imagination of the future into three levels based on the agent performing the action:

-

Low Agency: Use of passive voice, indicating events occur without recognizing a subject.

-

Medium Agency: Sentences in active voice by third-person agents like government or universities.

-

High Agency: Sentences in active voice by first-person agents, indicating high control or responsibility.

The extraction of agency was performed based on verbal constructions. At first, we look for passive voice markers. In Spanish, passive voice usually takes the form of reflexive passive, with the pronoun “se”. Therefore, we look for the particle “se” and other infinitive modal periphrasis, such as “debe haber”, or “debe existir”. If no such passive markers exist, we look at the main verb of the sentence, which may be the sentence root verb, or in the case of a verbal periphrases, the verb that holds conjugation. For this verb, we look at the conjugation endings to identify the first (singular or plural person). If the sentence is not conjugated in the first person, we assume the third person.

Modal attitude

Modal attitude aims to describe the speaker’s intention and is operationalized from a grammatical standpoint (Palmer 2001). It categorizes the speaker’s intention into three types:

-

Factual Attitudes: Statements about what is, using descriptive or factive verbs.

-

Evaluative Attitudes: Statements expressing the speaker’s opinion or judgment.

-

Propositive Attitudes: Statements using normative modal verbs like should, would, etc., indicating what ought to be done.

This variable is constructed by manual annotation and can also be automated using natural language processing techniques.

Type of process

The method also incorporates a systemic functional approach to language, focusing on the type of process that the clause construes. It distinguishes between:

-

Material Processes: Actions or doings.

-

Relational Processes: States of being.

-

Existential Processes: Recognition of events existing.

The main verb of each text entry is extracted and classified into one of these three categories to understand the intention behind the action.

By employing these methods, the study aims to provide a nuanced understanding of the text, particularly focusing on the agency exerted by the subjects and their modal attitudes or intentions. For more details see Supplementary Material Section S2.

Additional features

In our study, we incorporate a range of additional features to enrich our analysis. Text length is employed as a control variable, while the Categorical-Dynamic Index (CDI) is utilized to measure scholarly aptitude (Pennebaker et al. 2014). We also employ semiotic analysis to evaluate some aspects of democratic imaginations about the future, based on Goñi et al. (2024) and Zittoun and Gillespie (2018). One of these is called Multidimensionality, and reflects the degree of which a proposition incorporates multiple social dimensions (Goñi et al. 2024). Furthermore, our methodology adopts a systemic functional approach, categorizing verbs into material, relational, and existential types based on Halliday’s meta-functions (Halliday and Matthiessen 2004). The details and operationalization of these variables can be found in Supplementary Material Section S2.

Discrete choice modeling

After identifying political clusters and extracting features, we employ a discrete choice model to estimate the likelihood of a text belonging to a particular ideological cluster based on its linguistic features. Both Multinomial Probit and Logit models were tested. The relative risk ratios (RRR) are reported for interpretability. For model specifications and statistical tests, see Supplementary Material Section S3. Table 1 presents a summary of independent variables.

Model validation

To ensure that a few highly popular concepts do not determine the clusters, we performed a bootstrapping analysis through 100 random samples. We selected 100 observations by concept in each sample unless fewer than 100 texts were available. In that case, we used all the observations available.

Results

Understanding political groups through networks

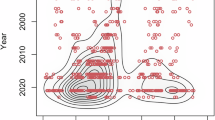

Figures 1 and 2 display networks that reveal how different political values and rights often appear together. Table 2 lists the key groups that emerge from these networks using the Louvain community detection algorithm (Figs. 1, 2 and Table 2 were adapted from Raveau et al. (2022b)).

Adapted from Raveau et al. (2022b).

Adapted from Raveau et al. (2022b).

Cluster D mainly includes first-generation rights, i.e., negative rights emphasizing political and civil liberties, along with property, freedom, and patriotism values (Vasak 1977), often linked with right-wing ideology. Cluster C mainly includes second-generation rights, i.e., positive rights that promote equality through a state’s active participation emphasis on social equality and state intervention, along with the Values dimension focused on justice and equality (Vasak 1977), traits commonly associated with the left. Cluster A combines second-generation rights along with most of the listed third-generation rights, such as those related to cultural heritage, environmental protection, and animal rights, indicating a progressive left-wing stance.

Cluster B is unique; it only appears in the Values network and promotes a conservative, often evangelical, viewpoint. There were explicit mentions to the evangelical community in texts. For example, “There must be freedom of worship because the Evangelical Church has the right to express itself and demonstrate freely anywhere.” There was also anecdotal evidence about the organization of the evangelical protestant community’s participation in the constituent process, which was evident in the almost identical text across different ELAs, in concepts such as “Heterosexual marriage family”. Although this cluster is absent in the Rights network, its closest relative there is Cluster D, suggesting they both lean right-wing.

The clusters identified in our analysis offer a compelling mirror to Chile’s political landscape as of 2016. Notably, Clusters A, C, and D align closely with the main political conglomerates observed in the country. The traditional left-wing, represented by Cluster C, has been a dominant force in Chilean politics, governing the country for two decades from 1990 to 2010 under coalitions known as Concertación de Partidos por la Democracia and later Nueva Mayoría. On the other side of the spectrum, the right-wing conglomerate, encapsulated in Cluster D, served as the principal opposition during this period and remains active under the banner of Chile Vamos.

A progressive-left group is emerging alongside these established players, captured in Cluster A. This group gained prominence under the Frente Amplio coalition, officially founded in 2017. Its leaders initially ran as independents in the 2013 Chilean general elections and achieved significant success, signaling a shift in the political landscape.

Additionally, Cluster B unveils a smaller yet highly organized conservative faction, filling a previously unoccupied space in Chile’s political representation. This cluster suggests the presence of a conservative void that the recently formed Republican party may have stepped in to fill.

To validate our findings, we compared these clusters with real-world political groups in different regions of Chile. The match was strong, confirming the reliability of our network analysis Footnote 5. We also tested alternative community detection algorithms and link formation thresholds, which didn’t significantly change our conclusions (See Supplementary Tables 4–7).

Finally, we compared our model against a random model (Candia et al. 2019). We generated 1000 randomized matrices where political values and rights were randomly paired. Our actual findings differed significantly from this random pairing, reinforcing the validity of our networks (See Supplemental Material).

Demographic and psychological insights for political clusters

To maintain the integrity of our analysis, we excluded the evangelical cluster (Cluster B) due to its limited presence in the sample. This cluster is unique to the Values network, making its exclusion from the Rights network unnecessary. However, for the sake of analytical consistency, we removed three Rights concepts that are highly associated with the evangelical community: Respect life from conception, Freedom of worship, and Peaceful assembly (Tables 2 and 3 of the Supplementary Material).

Figure 3 presents the Relative Risk Ratios (RRR) derived from our multinomial Probit model, where we tested the probability of belonging to different clusters. For a more detailed breakdown, readers are directed to Tables 10 and 11 in the Supplementary Material. To validate the robustness of our findings, we also employed multinomial Logit models, the results of which can be found in Tables 12 and 13 of the Supplemental Material.

Our analysis reveals that age is a significant factor influencing cluster membership. Younger individuals are predominantly found in the progressive cluster (Cluster A), a finding that aligns well with Inglehart’s theory on the generational shift from materialistic to post-materialistic values (Inglehart and Abramson 1994). Additionally, the Categorical-Dynamic Index (CDI), serving as a proxy for education, indicates that individuals with higher education levels are more likely to be part of Cluster A.

In terms of attitudinal dispositions, Cluster A is strongly associated with a normative stance. This cluster also shows a higher likelihood of using material verbs, particularly the word “guarantee.” This suggests that Cluster A advocates for positive state action with a normative orientation. Interestingly, this cluster also exhibits a higher use of the passive voice, indicating a normative character but with a lower sense of personal responsibility. This observation is consistent with theories on the locus of control, which examine how individuals perceive the control they have over events in their lives (Rotter 1966). Using a survey of young voters in the U.S., Sweetser (2014) showed that self-described democrats displayed a greater external locus of control than republicans.

Text length and the use of a multidimensional approach are more prevalent in Cluster A. This could be indicative of a higher level of details, and possibly a reflection of distrust in counterpart strategies. This observation is analogous to trends seen in constitution-making processes, where citizen participation often leads to more detailed constitutional documents (Ginsburg et al. 2009). Let us note that the multidimensionality metric does not function as originally conceptualized. It was supposed to capture multidimensional elements in the sentence, but it is actually capturing equifunctional elements. This is because the operationalization relies only on syntactic rules. To capture multidimensionality as designed, semantic elements should be added to compare the content of the coordinate elements.

Turning our attention to Cluster C, we find that evaluative attitudes are predominantly employed, especially when discussing values like Democracy and Respect. This cluster frequently uses first-person plural pronouns (high agency), emphasizing a collective sense of responsibility. However, when discussing rights, the third-person takes relevance, indicating that a particular entity (in this case, the State) is identified as the sentence’s subject. This is particularly evident when the discussion revolves around second-generation rights, which necessitate an active role from the state for their provision (United Nations (General Assembly) 1966b).

Lastly, Cluster D exhibits a tendency to employ factual attitudes and third-person, which suggests a more objective stance and a tendency to define the concepts. For rights, they also exhibit evaluative attitudes, emphasizing the fundamental nature of first-generation rights, such as property rights and freedom of conscience (United Nations (General Assembly) 1948, 1966a).

Discussion

In the complex landscape of political psychology two foundational elements are pivotal: (i) the delineation of political preferences and (ii) the utilization of psychological metrics to glean insights into mental states. In this study, we employed a network-based approach to represent political ideology, identifying three primary ideological clusters in both the Values and Rights dimensions. These clusters encapsulate the dominant political forces in Chile: the right-wing, traditional left, and progressive left. This approach aligns with the broader academic literature that emphasizes the role of psychological traits in shaping political outcomes (Cawvey et al. 2017; Cooper et al. 2013; Dawes et al. 2014; Fatke 2017; Graham et al. 2009; Haidt et al. 2009; Iyer et al. 2012; Lewis and Bates 2011; Pratto et al. 1994; Vecchione and Caprara 2009; Winter 2003).

Traditionally, psychological instruments such as tests, questionnaires, or scales have been the tools of choice for researchers. However, the burgeoning field of text analysis offers a novel avenue for investigating individual psychological, political, or socio-demographic characteristics (Boyd and Schwartz 2021; Vine et al. 2020). Central to this methodology is the assumption that language, like any other human behavior, is a reflection of mental states. In this vein, we identified lexical and syntactic markers, such as agency and modal attitude, that serve as proxies for psychological traits (Bandura 1986). Compared to surveys, text-based methods may overcome acquiescent and extreme responding as they don’t present options or predefined statements. The issue of socially desirable responding should also be reduced, since we are not focusing on the content of the response, but on the style. Other errors - such as sampling errors, priming effects or cultural differences - are transversal to both survey and text-based methods. Regarding temporal and spatial extent, text-based methods have a comparative advantage. Although online surveys may reach large populations at a feasible cost, and even in different countries, it is not possible to conduct surveys into the past. In contrast, we can analyze texts written in the past, being careful about differences in the use of language in distant times.

Our findings reveal that in Chile the progressive left cluster (Cluster A) is predominantly younger and more educated and resonates with movements like “Frente Amplio” in attracting individuals with a collective sense of agency and a focus on social justice. This cluster exhibits a normative attitude but often employs the passive voice, thereby failing to identify responsible actors for actions. This observation is consistent with previous research that has explored the role of agency in political behavior (Levenson and Miller 1976; Ryon and Gleason 2014; Smyth 2018). In contrast, the traditional left (Cluster C) is more explicit in identifying the State as the responsible entity for guaranteeing second-generation rights. This nuanced difference between the clusters is particularly evident in the Values dimension, where the traditional left emphasizes the fundamental nature of values and identifies society as both the beneficiary and the responsible actor.

The right-wing community (Cluster D) presents another layer of complexity. Contrary to what we expected, this cluster exhibits evaluative attitudes towards Rights rather than Values. This could be attributed to the cluster’s emphasis on first-generation rights, which are negative in nature. Our results suggest that these negative rights elicit evaluative attitudes, thereby serving as proxies for values.

In summary, this study contributes to the burgeoning literature on the interplay between psychological traits and political ideology, particularly in the context of digital political deliberation (Raveau et al. 2022a, b, 2023). While our approach is innovative, it is not without limitations. The aggregate nature of our data may dilute the effects observed in our regression models, suggesting a need for future research to focus on individual-level data. Furthermore, despite advancements in text analysis and natural language processing, a unified theoretical framework for the psychological language approach remains elusive. Through this work, we aspire to advance the discourse in this evolving field.

On the other hand, NLP methods have limitations themselves. Our approach assumes that language is a behavior. In this paradigm, the words we use are based on the attention we pay to things. The frequency of word usage allows us to create linguistic variables for a statistical study, however, limitations arise in the operationalization of these variables. For example, in the use of expressions or allegories that we cannot detect. On the other hand, when we use dictionaries - as in the case of Halliday’s verb lists - a natural limitation is that the lists are not necessarily exhaustive. In addition, there are variations in the way of speaking of certain places, and although this should not be relevant as we use only Chilean data, there could be sociocultural differences, or due to literary influences, television, or social networks. In the case of agency or modal attitude, we use only the main verb, and that can obscure the phenomenon if the sentence has a much more complex structure, with many verbs. Even so, the aforementioned variables recover the spirit that originated them, which is not the case in multidimensionality. In the regression model, this variable failed to honor the original interpretation.

By weaving together diverse threads—from the psychology of locus of control and agency to the digital transformation of political engagement and emerging methodologies in text analysis—this study aims to deepen our understanding of how individual psychology shapes political ideology. This aligns with our overarching research goal, as outlined in the introduction, to explore the psychological traits that differentiate affiliations with the New Left, traditional left, and traditional right political parties in Chile.

Data availability

The data to replicate results can be found here http://archivospresidenciales.archivonacional.cl/index.php/doc-10, https://github.com/uchile-nlp/ArgumentMining2017/tree/master.

Notes

As shown in Raveau et al. (2022b), these two dimensions reflect in a proper manner the political landscape in Chile.

Rights for both first and second generation were included in the Declaration of Human Rights of 1948, and also in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) of the United Nations (1966) (Domaradzki et al. 2019). Third generation rights are mentioned in the declarations of Stockholm (1972) and Rio (1992) at the United Nations General Assembly.

For each cluster, we chose the top municipalities that represent that ideology. Looking at the 2017 primary election in Chile, for clusters A and D we used the top 3 municipalities where participation in the progressive “Frente Amplio” coalition, and right-wing “Chile Vamos” coalition, respectively, was maximum. Since there were no presidential primaries of the traditional left-wing conglomerate for the 2017 presidential election, we chose the top 3 municipalities where the voting difference between the traditional left-wing coalition and the progressive left coalition was maximum. In each case, we compared the cluster distribution among these three municipalities and the rest of the metropolitan region. (see the details in Raveau et al. (2022b)).

References

Atari M, Henrich J (2023) Historical psychology. Curr Directions Psychological Sci 32(2):176–183

Bandura A (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall, New Jersey

Bandura A (2006) Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspect Psychological Sci 1(2):164–180

Blondel VD, Guillaume J-L, Lambiotte R, Lefebvre E (2008) Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J Stat Mech 2008(10):P10008

Boyd RL, Schwartz HA (2021) Natural language analysis and the psychology of verbal behavior: The past, present, and future states of the field. J Lang Soc Psychol 40(1):21–41

Candia C, Encarnação S, Pinheiro FL (2019) The higher education space: connecting degree programs from individuals’ choices. EPJ Data Sci 8(1):39

Cawvey M, Hayes M, Canache D, Mondak JJ (2017) Personality and Political Behavior. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Retrieved 2 Jul. 2024, from https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.221r

Chen D, Manning CD (2014) A fast and accurate dependency parser using neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Doha, Qatar. Association for Computational Linguistics, pp 740–750

Cooper CA, Golden L, Socha A (2013) The big five personality factors and mass politics. J Appl Soc Psychol 43(1):68–82

Dawes C, Cesarini D, Fowler JH, Johannesson M, Magnusson PK, Oskarsson S (2014) The relationship between genes, psychological traits, and political participation. Am J Political Sci 58(4):888–903

Domaradzki S, Khvostova M, Pupovac D (2019) Karel Vasak’s generations of rights and the contemporary human rights discourse. Hum Rights Rev 20(4):423–443

Fatke M (2017) Personality traits and political ideology: A first global assessment. Political Psychol 38(5):881–899

Ginsburg T, Elkins Z, Blount J (2009) Does the process of constitution-making matter? Annu Rev Law Soc Sci 5:201–223

Goñi J, Raveau MP, Fuentes-Bravo C (2024) Analytical categories to describe imaginations about the collective futures: From theory to linguistics to computational analysis. Futures 156:103324

González R, Manzi J, Saiz JL, Brewer M, De Tezanos-Pinto P, Torres D (2008) Interparty attitudes in Chile: Coalitions as superordinate social identities. Political Psychol 29(1):93–118

Graham J, Haidt J, Nosek BA (2009) Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. J Personal Soc Psychol 96(5):1029–1046

Haidt J, Graham J, Joseph C (2009) Above and below left–right: Ideological narratives and moral foundations. Psychological Inq 20(2–3):110–119

Halliday M, Matthiessen C (2004) An Introduction to Functional Grammar. Hodder Arnold, London

Inglehart R, Abramson PR (1994) Economic security and value change. Am Political Sci Rev 88(2):336–354

Iyer R, Koleva S, Graham J, Ditto PH, Haidt J (2012) Understanding libertarian morality: The psychological roots of an individualist ideology. PLoS One 7(8):e42366

Jordán T, Figueroa P, Araya R, Gómez C (2016) Guía metodológica para la etapa participativa territorial. Technical report, Ministerio Secretaría General de la Presidencia, https://www.unaconstitucionparachile.cl/guia_metodologica_proceso_constituyente_abierto_a_la_ciudadania.pdf, accessed June 2019

Kacewicz E, Pennebaker JW, Davis M, Jeon M, Graesser AC (2014) Pronoun use reflects standings in social hierarchies. J Lang Soc Psychol 33(2):125–143

Kavada A (2016) Social movements and political agency in the digital age: A communication approach. Media Commun 4(4):8–12

Krosnick JA, Lavrakas PJ, Kim N (2014) Survey research. In Reis HT, Judd CM (eds), Handbook of research methods in personality psychology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 404–442

Levenson H, Miller J (1976) Multidimensional locus of control in sociopolitical activists of conservative and liberal ideologies. J Personal Soc Psychol 33(2):199–208

Lewis GJ, Bates TC (2011) From left to right: How the personality system allows basic traits to influence politics via characteristic moral adaptations. Br J Psychol 102(3):546–558

Lyra MS, Curado A, Damásio B, Bação F, Pinheiro FL (2021) Characterization of the firm–firm public procurement co-bidding network from the State of Ceará (Brazil) municipalities. Appl Netw Sci 6(1):1–10

Manning CD, Surdeanu M, Bauer J, Finkel JR, Bethard S, McClosky D (2014) The Stanford CoreNLP natural language processing toolkit. In Proceedings of 52nd annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: system demonstrations, Baltimore, Maryland, pp. 55–60

Mondak JJ (2010) Personality and the foundations of political behavior. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Moore SS, Hope EC, Eisman AB, Zimmerman MA (2016) Predictors of civic engagement among highly involved young adults: Exploring the relationship between agency and systems worldview. J Community Psychol 44(7):888–903

Newman ME (2006) Modularity and community structure in networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103(23):8577–8582

OECD (2012) Measuring regulatory performance: a practitioner’s guide to perception surveys. Technical report, OECD. Publishing and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Staff

Onnela J-P, Chakraborti A, Kaski K, Kertesz J, Kanto A (2003) Dynamics of market correlations: Taxonomy and portfolio analysis. Phys Rev E 68(5):056110

Palmer FR (2001) Mood and modality. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Paulhus DL, Vazire S (2007) The self-report method. In Robins RW, Fraley RC, Krueger RF (eds), Handbook of research methods in personality psychology, chapter 13. New York: The Guilford Press, New York, pp. 224–239

Pennebaker JW, Chung CK, Frazee J, Lavergne GM, Beaver DI (2014) When small words foretell academic success: The case of college admissions essays. PloS one 9(12):e115844

Pennebaker JW, Boyd RL, Jordan K, Blackburn K (2015) The development and psychometric properties of LIWC2015. Technical report, Austin, TX: University of Texas at Austin

Pratto F, Sidanius J, Stallworth LM, Malle BF (1994) Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. J Personal Soc Psychol 67(4):741–763

Raveau MP, Couyoumdjian JP, Fuentes-Bravo C (2022a) Mapping the complexity of political ideology using emergent networks: the Chilean case. Appl Netw Sci 7(1):1–23

Raveau MP, Couyoumdjian JP, Fuentes-Bravo C, Rodriguez-Sickert C, Candia C (2022b) Citizens at the forefront of the constitutional debate: Voluntary citizen participation determinants and emergent content in Chile. PloS one 17(6):e0267443

Raveau MP, Couyoumdjian JP, Fuentes-Bravo C, Candia C (2023) Consideraciones sobre la democracia deliberativa y lecciones del caso chileno. Estudios Públicos, p. 9–40

Kotz, S, Balakrishnan N, Read CB, Vidakovic B (2006) Encyclopedia of statistical sciences, 2. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey

Rosen B, Salling R (1971) Political participation as a function of internal-external locus of control. Psychological Rep. 29(3):880–882

Rotter JB (1966) Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monogr: Gen Appl 80(1):1–28

Ryon HS, Gleason ME (2014) The role of locus of control in daily life. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 40(1):121–131

SEGPRES (2016) Guía para organizar encuentros locales. Technical report, Ministerio Secretaría General de la Presidencia. https://www.unaconstitucionparachile.cl/guia_encuentros_locales.pdf, accessed June 2019

Sibley CG, Osborne D, Duckitt J (2012) Personality and political orientation: Meta-analysis and test of a threat-constraint model. J Res Personal 46(6):664–677

Smyth R (2018) Considering the Orange legacy: patterns of political participation in the Euromaidan Revolution. Post-Sov Aff 34(5):297–316

Sweetser KD (2014) Partisan personality: The psychological differences between democrats and republicans, and independents somewhere in between. Am Behav Scientist 58(9):1183–1194

Titelman N (2023) La nueva izquierda chilena. De las marchas estudiantiles a La Moneda. Santiago, Ariel

Torcal M, Mainwaring S (2003) The political recrafting of social bases of party competition: Chile, 1973–95. Br J Political Sci 33(1):55–84

Toutanova K, Klein D, Manning CD, Singer Y (2003) Feature-rich part-of-speech tagging with a cyclic dependency network. In Proceedings of the 2003 conference of the North American chapter of the association for computational linguistics on human language technology, vol 1. Association for Computational Linguistics, Edmonton, pp 173–180

United Nations (General Assembly) (1948) Universal declaration of human rights. UN Gen Assem 302(2):14–25

United Nations (General Assembly) (1966a) International covenant on civil and political rights. Treaty Ser 999:171

United Nations (General Assembly) (1966b) International covenant on economic, social, and cultural rights. Treaty Ser 993:3

Vasak K (1977) Human rights. a thirty-year struggle: the sustained efforts to give force of the universal declaration of human rights. UNESCO Courier, Paris

Vecchione M, Caprara GV (2009) Personality determinants of political participation: The contribution of traits and self-efficacy beliefs. Personal Individ Differences 46(4):487–492

Vine V, Boyd RL, Pennebaker JW (2020) Natural emotion vocabularies as windows on distress and well-being. Nat Commun 11(1):4525

Winter DG (2003) Personality and political behavior. In Sears DO, Huddy L, Jervis R, (ed) Oxford handbook of political psychology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 110–145

Zittoun T, Gillespie A (2018) Imagining the collective future: A sociocultural perspective. In Saint-Laurent C, Obradović S, Carriere K (ed) Imagining collective futures. Palgrave Studies in Creativity and Culture. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, p 15–37

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge researchers and graduate students from the Centro de Investigación en Complejidad Social (CICS) for their thoughtful and helpful feedback. Also, the authors acknowledge the Instituto de Data Science at Universidad de Desarrollo and FARO at Universidad del Desarrollo for their support. This research received no external funding and the APC was funded by Universidad del Desarrollo, project INCA210006 (InES Ciencia Abierta).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MPR, CC and JPC conceived the idea. CFB contributed to the linguistic design and data collection. MPR processed the experimental data and analyzed data. MPR and CC wrote the manuscript. CR and JPC contributed to the analysis of the results. All authors contributed to the data interpretation and results. All authors thoroughly reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The data utilized in this study are secondary in nature and are publicly accessible at the following link: http://archivospresidenciales.archivonacional.cl/index.php/doc-10, https://github.com/uchile-nlp/ArgumentMining2017/tree/master. Ethical approval for using the data was waived by the Institutional Review Board of Universidad del Desarrollo. The document is available upon request.

Informed consent

The present study employs publicly accessible secondary data. As such, the requirement for informed consent was deemed unnecessary and was consequently not sought.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Raveau, M.P., Couyoumdjian, J.P., Fuentes-Bravo, C. et al. The lexical divide: propositive modes and non-agentic attitudes define the progressive left in Chile. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 908 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03379-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03379-6