Abstract

This paper sheds light on the internal heterogeneity within the informal economy by examining the working conditions of migrant informal workers in China. It presents the first attempt to test the WIEGO model on the relationship between informality, income, poverty and gender. Based on 107,020 samples of informal workers from the 2017 China Migrants Dynamic Survey (CMDS), economic, social and occupational health components of working conditions of migrant informal workers in five employment-status tiers are analysed. The results show the significant heterogeneity within informal workers in terms of their income, working intensity, labour contracts, social security, union and community support. The relationships between the informal employment tiers and income, poverty and gender show a pattern that is not fully in line with the WIEGO model, suggesting the complexity and plurality of heterogeneities in informal employment. The paper concludes by calling for research on regional varieties of the heterogeneity in informal employment worldwide to better understand the unfolding of the inequality-informality nexus in specific contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Informal employment is a predominant form of urban employment and a major source of employment growth in the world (Marcelli et al. 2010; Gasparėnienė et al. 2022). Increasing evidence suggests that informal employment is not a transitory phenomenon that will disappear with economic development, but a part and parcel of the contemporary global labour market (Chen and Carré 2020). Old forms and new forms of informal employment have persisted and emerged around the world with the rise of flexible capital accumulation and neoliberal political economies (ILO 2021). It was reported that 2 billion people in the world or about 60% of the global workforce earn a living through informal employment (ILO 2023). In China, informal employment has expanded rapidly since the 1980s when reform and opening-up policy was adopted (Huang et al. 2022). First of all, marketization has broken the state sector’s ‘iron rice bowl’ arrangement established in the early socialist period that provided workers with a guaranteed job. This led to a reduction in formal employment and the growth of informal employment in both state-owned and private sectors (Huang 2009). Second, the export-orientated industrialization driven by global capital generated a large number of employment opportunities, which were mostly arranged in informal ways by firms in order to maintain low labor cost advantage in global competition (Wang et al. 2016). Third, huge numbers of rural migrants moved to cities in search of jobs, providing abundant and cheap labour for industrialization. These migrants were denied access to cities’ local social welfare entitlements conferred upon Chinese citizens by the hukou (residential registration) system (Chan et al. 1999; Kuptsch and Charest 2021). The lack of a local urban hukou rendered rural migrants discriminated against in urban labour markets and forced into informal employment. Hence, the expansion of informal employment in post-reform China is a result of the interaction of marketization, industrialization and urbanization and demographically characterized by the domination of rural migrants in the informal workforce.

At the global level, migrant workers are also more likely to engage in the informal economy, and the majority of informal workers tend to be migrants (ILO 2018). Cities are primary destinations for heterogeneous migration flows, and the characteristics of informal employment—a combination of ease-entry, flexibility, mobility and extra-legality—make it a stronghold for migrant labour in cities (Altenried 2024; Anne Visser and Guarnizo 2017; Toksöz 2018). However, despite its contributive role in the alleviation of poverty and unemployment, informal employment has rendered an increasing number of workers suffering from the erosion of working conditions and the intensification of precarity and vulnerability (Chen et al. 2004). Informality in employment has become a focus of concerns of the decent work project in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations 2015).

It is important to realize that informal employment is not a homogeneous body when implementing the decent work project. In the existing literature, the working condition of informal employment is generally understood by the approach of differentiating it from formal employment, with the view that informality is poor, vulnerable and precarious while formality is associated with nice income, security and stability. This conception is insufficient and somewhat misleading as it fails to capture the internal heterogeneity of informal employment. As will be argued in this paper, informal workers cannot simply be viewed as a homogeneous employment group as they differ significantly in their employment status, level of income and degree of poverty. Such differences lead to the inequality within the class of informal workers. This inequality is easily ignored as it is not as visible as that existing between informal and formal workers. In attempting to highlight the interior heterogeneity and inequality within informal workers, the Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO, https://www.wiego.org/) has developed a pyramid model, in which informal workers are classified according to their employment status and diversified by differences in the level of their economic income and poverty risk and in their gender ratio. WIEGO is a well-known global research network on informality dedicated to improving the working conditions of informal workers worldwide. It works closely with the United Nations (UN) agencies including International Labour Organization (ILO), UN-Habitat and UN Women. The pyramid model WIEGO developed has been widely used as an analytical framework for decomposing informal employment (Chen and Carré 2020). Theoretically, the model provides a starting point for understanding the heterogeneity in the working conditions of informal workers. However, little research has been done to evaluate the validity of the model in the context beyond the regions it was based on since it was proposed. As the landscape of informal economies is embedded in local political, economic and social contexts (Williams and Windebank 2001), it should be realized that the relationships between informal work, employment status and poverty are not as simple and linearised as the model has conceived (Kannan 2017).

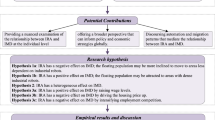

This paper contributes to the literature by examining two questions. First, it enhances the understanding of the heterogeneous nature of informal employment by analysing the working conditions of migrant informal workers in China, with the aim to expose the interior inequality in informality beyond the approach of formal-informal dichotomy. In China, while informal workers include urban laid-off workers who had lost jobs in state-owned or collective enterprises, they are demographically dominated by migrants due to their disadvantaged position in urban labour markets (Huang 2009). As Huang (2009) estimated, over 71% of the 168 million urban informal workers in China were migrants from rural areas. If excluding officially registered employment, migrant workers would take a higher proportion in the informal economy (Chen et al. 2021). These migrants work either as informal employees in formal and informal sectors or as informal employers/self-employed with/without employees. Second, the paper presents the first effort to test the WIEGO model by analysing the complex working conditions of informal workers and their differences in the Chinese context. Starting from a comprehensive examination of working conditions of informal workers stratified by their employment status, it then pays attention to the disparities in income, poverty risk and gender segmentation among informal workers. It argues that while working conditions of informal employment are internally heterogeneous, this heterogeneity varies across different socio-economic contexts. The paper provides a critical evaluation of the WIEGO model and opens up a question of geographically variegated heterogeneities of informal employment.

The remaining section starts with a review of the literature on working conditions of informal employment and the WIEGO model by focusing on the heterogeneity of informality. The third section describes the methodology, including the data, the measurement of working conditions and the ways informal employment is defined and stratified. The fourth and fifth sections report the results of the analysis and the test of the WIEGO model. The final section concludes with the discussion on the heterogeneous nature of informal workers and research implications for the heterogeneity of informality.

Heterogeneity in working conditions of informal employment

Working conditions of informal employment

Informal employment is generally defined as employment relationships that are not recognized, registered, regulated or protected by labour legislation and social security (Chen 2005). Working conditions is a synthetical concept that includes income, welfare, security, and the working environment (Yeh 2015; Segbenya et al. 2022). It is also understood in relation to the concept of decent work, which refers to adherence to labour standards, quality of work, social protection and social dialogue (Eurofound and International Labour Organization 2019). Informal workers face harsh working conditions as they lack basic legal and social protection. They may be fired without access to courts, their wages are not paid on time, and they may lack job benefits, sick leave, statutory rest days, or pensions (ILO 2013; Burchielli et al. 2014; Rodríguez-Modroño 2021). Compared to formal workers, informal workers were more likely to lack economic opportunities, labour rights, social protection, and the right to speak, which are known as the four pillars of decent work (ILO 2002; Gasparėnienė et al. 2022; Lotta and Kuhlmann 2021). Research shows a significant inequality in earnings between informal and formal workers with the former tending to earn less (Abramo 2022; Williams and Horodnic 2019; Chen and Hamori 2013; Shapland and Heyes 2017). Hence, workers in the informal economy face higher poverty risks compared to the formal economy (Chen et al. 2005; Amarante and Arim 2017; Williams 2014; Bonnet et al. 2019).

The poor nature of informal employment’s working conditions is rooted in the restructuring of capitalist economies. The rise of flexible capital accumulation, coupled with deregulation and liberalisation, has resulted in the erosion of job quality and the growth of downgraded labour in the world. Capitalist firms mobilize informalisation as an employment strategy to cut costs, improve global competitiveness and weaken the power of local unions (Williams and Round 2007; Chen 2012). In the political-economic regime favourable for capital, informal workers are deliberately excluded from social security schemes, safety, health, maternity and other labour protection legislation. More than a problem of development, poor working conditions of informal employment are in essence a feature of the labour markets in the flexible accumulation regime (Castells and Portes 1989; Williams and Horodnic 2019).

The deterioration of working conditions in the informal economy is fueled by the growth of migration and female workforces. The ILO (2018) report notes that migrant workers are disproportionately concentrated in low-skilled and low-paid jobs in the informal economy, particularly in agriculture, construction, manufacturing, and domestic work. Many researches have argued that the vulnerable, exploited and low-status migrant workers in cities are produced by policy and legal frameworks in which they were denied full citizenship rights and ended up with entering subordinate labour markets (Sassen 1996; Bauder 2008). In China, the working conditions of domestic migrant workers are largely affected by the hukou system (Chan et al. 1999). Although the hukou system no longer has the function of restricting people’s mobility, it plays a vital role in the allocation of social welfare resources (such as public education services and institutional social security), which migrants were denied access to as they have no urban residential status. Migrant informal workers in China are mainly from rural areas. As “second-class citizens” (Huang 2009: 408), they have to take the dirtiest, lowest-paid and most insecure jobs that urban residents are unwilling to do. Some of them are employed in the formal sector as low-paid, non-benefited casual workers, while others are employed in the informal sector, including ‘private enterprises’ or ‘self-employed households’ that are not registered with the government. In addition to migration, the growth of women workers’ participation in labour markets also facilitated the erosion of working conditions. Compared to men, women workers are more likely to be victims of deteriorated working conditions in the informal economy due to gender discrimination in labour markets (Benería et al. 2016; Cassirer and Addati 2007; Bhan et al. 2020). Hence, there is an emerging coupling of migration, gender and deterioration of informal employment in current global capitalism.

The internal heterogeneity of informal employment

While plenty of research characterized the working conditions of informal workers by comparison to formal workers, attention paid to the heterogeneity within informal employment is limited but increasing. An early study by Fields et al. (1990) developed an idea of the duality of urban informal employment, characterized by “easy entry” and “upper class” of informal employment. Fields found that many of those in upper-class informal employment entered the informal economy “voluntarily”, they might work previously in the formal economy, where they gained skills and resources to start up their own informal business as employers. There is also the “constrained voluntary”, which outlines how informal workers enter informal employment because of their restricted options. Williams and Bezeredi (2018) verified the effectiveness of the dual informal labour market, showing that informal workers in the 28 EU countries who actively chose to work were twice as those who chose to work out of survival needs. This research was echoed by Devlin (2018), who differentiated “informality for needs” and “informality for desire”, which means the practice of urban poor people to meet their basic needs and that of wealthier people for convenience, efficiency or creative expression, respectively. Wealthier people choosing to be informal workers may be a better choice for economic gain or work flexibility, while people who work in informal employment because of their survival needs may be bottom workers excluded by the formal economy. Likely, a recent study developed the notion of constrained voluntary informalisation, which differentiated three groups of informal self-employed migrant workers (i.e. the survivalist, over-exploited and developmentalist) by capturing multiple structural and individual factors driving their participation in informal employment (Huang et al. 2020). In sum, these studies have highlighted the diversity in typologies of informal workers in terms of their employment motivations and the difference in their social identity. Poorly known, however, is how the working conditions of different types of informal workers may vary in different industries and employment statuses. In particular, how different informal workers are in terms of labour standards, quality of work or social protection? Examination of this question will enable us to expose the inequality within informal employment other than between informal-formal groups and advance the understanding of the nature of working conditions in the informal economy.

The WIEGO model of informal employment provides a good starting point to examine the heterogeneity of working conditions in the informal economy. The model stratified informal workers by their employment status, which is understood as the economic risk of losing jobs and income and the degree of power over the enterprise and other workers (Chen 2016). Based on five main employment categories of the International Classification of Status in Employment (ICSE)—employers, own-account workers, employees, contributing family workers and members of producers’ cooperatives, Charmes (1998) analyzed the contribution of women in the informal sector through statistical data. Furthermore, Sethuraman (1998) found a strong link between informal employment, women and poverty through a review of the relevant literature on informality, gender and poverty. Based on their work, WIEGO constructed an initial model without considering poverty risk, which highlights differences in income and gender ratios across different informal employment groups categorized by employment status in the informal economy (Chen 2014). In 2004, WIEGO moved forward in exploring the relationship between the employment status (measured at the individual level) and poverty status (measured at the household level) of informal workers based on national informal workers data in six developing countries: Costa Rica, Egypt, El Salvador, Ghana, India, and South Africa, revealing the connection between the employment category of informal workers and poverty risk (Chen et al. 2005). This work was integrated into the WIEGO model, which formulates the relationships between informal employment status and income, poverty, and gender as shown in Fig. 1. In light of the model, the higher the employment tiers, the higher the average income and the higher the share of males. However, there is a negative relationship between employment tiers and poverty risk, indicating that the lower the employment tiers the higher the probability that informal workers come from poor households (Chen and Lund 2016). In a word, the pattern is that as the employment tier of informal workers declines, the risk of coming from poor households rises, the share of females rises, and their average income falls.

The WIEGO model presents an effort to disclose the inequality and heterogeneity in informal workers by focusing on their economic income, poverty and gender features. However, the validity of the model has not been sufficiently empirically tested. The WIEGO model was initially developed based on Charmes’s analysis and Sethuraman’s literature summary, and formed with the integration of evidence from six developing countries. Given the limitation of the model in terms of its regional empirical basis, testing its applicability in other regions will contribute to advancing the theorization of heterogeneity in informal employment. The pattern of the links between employment tiers, poverty, and gender might vary in different socio-economic contexts considering the diversity of informal economies in the world (Chen and Carré 2020), Moreover, the WIEGO model fails to consider the full dimension of working conditions and is limited to the issues of income, poverty risk and gender. This paper follows the WIEGO’s approach to stratify informal workers according to their employment status and expands it by adopting a comprehensive definition of working conditions. The paper thus enriches the existing literature on the heterogeneity of informal employment while providing a critical evaluation of the WIEGO model.

Methodology

Data source

This paper uses data from the 2017 China Migrant Dynamics Survey (CMDS). The CMDS is a nationwide large-scale sample survey of migration conducted by the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China, using a stratified, multi-stage sampling method called Probability Proportionate to Size Sampling (PPS). It covers cities where the migrant population highly concentrated in 32 provincial-level units in mainland China (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan). The sample in CMDS represents people aged 15 years and above who have lived in the destination cities for one month or more, and whose purpose of migration is mainly for making a living or working (excluding those who are “students” or leaving temporarily for reasons such as travel, medical treatment, business trips, and family visits). In 2017, a total of 169,988 samples were surveyed in 298 cities in China. As we aim to explore the working conditions of labouring populations, samples with blank monthly income and weekly working hours are eliminated. The usable samples therefore include a total of 139,837 migrant workers.

Extraction of migrant informal workers

Informal employment includes all jobs in the informal economy, which may be found in the formal sectors, informal sectors, or households, focusing on jobs that lack basic social or legal protections and employment benefits (Williams and Lansky 2013). Based on the operating criteria formulated by ILO (2018), the following types of work are defined as informal employment: (i) Contributing family workers; (ii) Employers, own account operators who own enterprises in the informal sectors; (iii) Employees contributing to social security by themselves, and with no paid annual leave or paid sick leave. As the CMDS questionnaire lacks questions on paid leave and pension insurance for migrant workers, we combine the questionnaire content of the data to categorize them as formally and informally employed according to the following criteria (as illustrated in Fig. 2): (i) Employment status as the employer or own-account worker, if the employment unit is an individual business, unincorporated and other, he/she is considered being an informal worker; (ii) For an employee with regular employers, if he/she has written employment contracts with employers, and the employers make contributions on behalf of the employee to medical services, he/she is considered as being in formal employment. Otherwise, the employees are considered to be in informal employment. (iii) If the person chooses “others” as employment status, and the type of work is not that of the head of a state organ, mass organisation, enterprise, institution, professional or technical staff, and civil servant, he/she can be categorized as an informal worker. There are finally 107,020 samples of migrant informal workers used for the analysis.

Stratification of informal workers

Following the WIEGO approach, we subdivide informal workers into six employment types (Fig. 3). Employers are in the highest employment tier. They are those who own businesses, either individually or collectively. Most of these businesses are likely to be small, often referred to as “microenterprises”, employing few workers and not complying with the legal and institutional frameworks. Informal employees with a regular employer, with a written employment contract or in a probationary period are defined as informal regular workers. Own account operators, often called self-employed persons, conduct work tasks or earn income in an independent capacity without employing anyone. Employees without regular employers who use their own home as the workplace are considered home-based workers. Employees without regular employers who perform one-off tasks are identified as outsourced workers. Outsourced workers are differentiated from own-account operators because they have much less power than own-account operators in terms of work schedules, product specifications, raw materials, and product sales (Chen 2016). Informal casual workers include employees with regular employers who do not have a written employment contract or who perform one-off tasks and employees without regular employers who do not perform one-off tasks. They change jobs frequently and are more economically vulnerable than informal regular employees. The type of contributing/unpaid family workers is not considered in our analysis as the data on it is absent in the CMDS dataset. Our test is thus focused on the five employment tiers in the WIEGO model.

With the aim to test the WIEGO model, we need to measure the poverty risk. “Poverty risk” links informal employment status at the individual level to poverty risk measured at the household level, which is defined as the likelihood that a migrant informal worker comes from a poor household. We measure the poverty risk as the proportion of migrant informal workers in the household with incomes below the national poverty level at a given employment tier. In other words, if a family’s per capita annual income is below the national poverty criteria, then the family is considered as poor. As the poverty criteria vary considerably around the world, we adopt relatively uniform poverty criteria on a national scale. China’s poverty criteria in 2017 defined households with an annual income of less than RMB 2952 (USD 437) per person (including those who do not work, such as retirees, children and adolescents who have not yet reached working age) as poor households.

Measurement of working conditions

Working condition is a composite concept involving multiple dimensions of economy, sociology, and occupational health (World Health Organization 2006; Eurofound and International Labour Organization 2019). Instead of being limited to the economic issues of income and poverty, this paper established a comprehensive index system for measuring working conditions of informal workers (Table 1). The economic dimension of working conditions is primarily related to workers’ income, which is their basic source of subsistence and means of material well-being. Life satisfaction increases with the growth of income. Income serves as an incentive to further increase the productivity of workers and make them identify themselves (Kim 2022). We used an individual’s wage/net income in the last month to measure the economic income.

The social dimension of working conditions is primarily represented by job security, without which workers are exposed to the risk of unemployment and survival crises. The first indicator used to measure job security is the written employment contract. Only when the written employment contracts are signed between employers and workers are the labour relations between them established and recognized, and national policies and labour laws will have protections for them. The second indicator is the social security brought by work—medical insurance, which is measured by types of medical insurance. Medical insurance, jointly paid for by the employers and the labourers, is an indispensable social protection that addresses the medical risks associated with illness or injury to the workers (Brummund et al. 2018). Another aspect of the social dimension is the life situation, namely the difficulties in family life, representing the status and extent to which workers are affected by their work in the field of social reproduction.

The occupational health dimension of working conditions is mainly reflected in the quality of the work environment, which includes factors such as working time arrangements, workplace relations, and training opportunities. People are faced with various “work demands” in their daily work that require continuous physical, cognitive and emotional effort. Material, organisational or social “work resources” (such as job autonomy, learning opportunities, and support from unions and communities) help workers cope with work demands, achieve work goals, and stimulate learning and personal development. Work demands would become stressors when workers do not have sufficient work resources. Excessive demands coupled with inadequate work resources result in “work stress”, which is a significant risk factor for the physical and mental health of workers (Eurofound and International Labour Organization 2019). In our study, work demands are measured by working intensity, which is estimated by weekly working hours. Union support and community support are used to measure work resources. In China, labour unions are established voluntarily by the working class and must be authorized and regulated by the government. According to the law, unions represent the interests of workers and are responsible to protect their lawful rights and interests. The indicator ‘union support’ is measured by the frequency of informal workers’ participation in union activities, meaning that workers have access to unions’ help and assistance in protecting their working conditions. Both unions and community organisations increase workers’ ability to negotiate better working conditions with enterprises and authorities, help workers share resources to attain higher incomes and influence policies and regulations that directly affect them (Chen and Vanek 2013; United Nations Development Programme 2015). Community support is measured by the involvement of workers in community affairs.

Data processing

The data were first normalized and rescaled with the value 1 for the best condition of the indicators and 0 for the worst condition of the indicators. We then used the factor analysis method to assign weights to the indicators. The factor analysis method obtains the principal factors that represent most of the information of the multi-dimensional indicators by merging the indicators of working conditions, extracting the common information in the indicators, and consolidating multiple indicators into a few main factors. We used the variance contributions of the principal factors as the weights and then calculated the indicators scores separately, namely the weights of indicators.

The Pearson correlation analysis was carried out on the indicators of working conditions. The results show that the KMO (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin) test value is 0.691, and the significance of Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity is less than 0.001, meaning the data is highly correlated and is suitable for factor analysis. The variance maximisation method was chosen to perform orthogonal rotation on the factor weights to explain the relationship between the factors more clearly. The principal component factors were selected according to the variance percentage of the factors and the scree plot, and finally, three principal component factors were obtained. The cumulative variance contribution rate reaches 79.616%. The weight of each factor is shown in Table 1.

Analysing working conditions of migrant informal workers

Profile of migrant informal workers

About 80% of migrant populations were employed in the informal economy, among whom 65.3% worked in tertiary industries and 31.9% in secondary industries (Table 2). More than half (57.2%) were men workers, with a slightly higher proportion than women (42.8%). Among all age groups, there is an inverted U-shaped curve with migrant workers aged 25 to 34 years most likely to work in the informal economy, and the average age of migrant informal workers is higher than that of formal workers. The vast majority of migrant informal workers are from rural areas as 83.8% of them are agricultural households and 81.9% have rural household registration. And nearly half (49.5%) are inter-provincial migrants who moved from underdeveloped central and western regions to developed eastern coastal regions. Only 10% of migrant informal workers had a junior college or university education. However, the majority (71.4%) had middle and high school education, and 18.6% did not complete nine-year compulsory education.

Working conditions of migrant informal workers

By calculating the weighted average values of the indicators of monthly income, workweek, types of employment contract, types of medical security, difficulties in life, participation in union activities, and participation in community affairs, the working conditions scores of migrant workers are obtained. For informal workers, the average value is 0.34, lower than the average value for the total (0.41) and the average for formal workers (0.64). This indicates the worst working conditions of informal workers among migrant workforces.

The stratification of informal workers in terms of their employment status shows that own account operators make up the majority (about 42%), followed by informal casual workers (27%) and informal regular workers (21%), while employers and outsourced workers/home-based workers take up 6.3 and 1.5%, respectively. Own account operators included street vendors, shoemakers, motorbike drivers, waste pickers and small-shop or store owners without employees. Informal regular and casual workers were mostly employed in manufacturing sectors concentrated in the textile, electronic, and plastic industries. Many casual workers worked in construction sectors and urban low-end service sectors. Outsourced workers and home-based workers were embedded in national and global production networks. They mostly lived in the urban villages with low-priced housing and completed subcontracted work in their house. Employers were those who were owners of small shops or factories with several employees generally less than five. They normally did not fully comply with labour laws and business regulations and were mostly located in urban villages or marginal areas with weak state regulations.

In order to disclose the internal heterogeneity of informal workers, a linear regression is performed with the dummy variables of informal worker tiers as the independent variables and working conditions as the dependent variable, controlling for other variables (such as socio-demographic and migration characteristics) and using the informal regular worker as the control group (Table 3). The results do not show a significant hierarchical pattern in which working conditions improve with the rise of the informal employment tiers as established by the WIEGO. Rather, on the whole, informal regular workers have much higher working conditions scores than other informal employment tiers, with working conditions in descending order of informal casual workers, outsourced workers/home-based workers, employers and own account operators.

Multivariate general linear model analysis of the relationship between each aspect of working conditions and informal employment tiers is conducted to further unpack the heterogeneity, considering the influences of gender, education and hukou factors (Table 4). In terms of the economic dimension, employers tend to have the highest incomes, followed by informal regular workers and outsourced workers/home-based workers and own account operators, with informal casual workers having the lowest income.

Regarding the social dimension, informal regular workers are much more likely to have a written employment contract than informal casual workers and outsourced workers/home-based workers, while neither own account operators nor employers have an employment contract due to the nature of their work. For social security, employers are more likely to have medical insurance for urban staff that have wider medical coverage, while informal regular workers are more likely to lack insurance. As to the difficulties in life for those in informal employment, outsourced workers/home-based workers faced the most severe difficulties from work, followed by own account operators. Informal casual workers experienced a similar level of difficulties with employers, while informal regular workers faced the least severe difficulties.

In terms of the occupational health dimension, the work intensity from highest to lowest in order is informal regular workers, outsourced workers/home-based workers, informal casual workers, employers and own account operators, with slight differences between employers and own account operators. Regarding union support, informal regular workers are more likely to participate in union activities, and the probability of participation in union activities among other tiers is much similar. Informal regular workers, employers and own account operators are more likely to gain community support, and informal casual workers and outsourced workers/home-based workers are less likely to receive the same support.

Table 4 shows the results of the correlation between gender, education and hukou factors and the working conditions of informal workers. Compared to female workers, the males have higher incomes, work with less intensity and are more likely to have labour contracts and receive union and community support, indicating gender inequality among migrant informal workers in terms of their working conditions. There is a significant correlation between education and higher worker earnings, and greater participation in union and community activities. The higher the level of education, the higher the income informal workers earn, the lower work intensity they get and the greater the likelihood they engage in union and community activities. A significant correlation is also found between the urban and rural household division of the working conditions of migrant informal workers. Compared to workers with rural hukou, those with urban hukou earn higher incomes and receive more union support, but are less likely to have labour contracts. Interestingly, workers with rural hukou gain better social security compared to those with urban hukou. This is because of the national policy that incorporates rural populations into the new rural cooperative medical care system.

Testing the WIEGO model

Economy income and informality

The WIEGO model suggests that there is a positive correlation between the tier of informal employment and average earnings. We conduct a linear regression analysis using the dummy variables transformed by informal employment tiers as the independent variables, employers as the control group, and income as the dependent variable. The results are shown in Model 1 of Table 5.

As shown in Model 1, employers have the highest average earnings, with informal regular workers earning the second highest. In contrast to the WIEGO model, outsourced workers/home-based workers have higher incomes than informal casual workers and own account operators, with own account workers earning the lowest. This is consistent with a study on the income gap between formal and informal employment in China, which found that the hourly wages of own account workers were not only lower than formal employees, but also lower than informal employees (Qu 2012). Comparing the regression results of income with the average income of each tier (Fig. 4), we find that the average income of own account workers is second to employers, differing from the regression results that show they earn the lowest in the statistical sense. This may be due to the large internal differences in the income of own account workers, with 2.4% of them having a negative monthly income; it may also be due to the greater instability in the income of own account workers. Related to the previous section, own account workers work the longest but earn the lowest income in a statistical sense. This suggests that own account workers may face great income inequality and high economic risks.

Poverty risk and informality

The WIEGO model suggests that the lower the tier of informal employment, the higher the poverty risks. We run a binary logit regression of poverty risks using the informal employment tiers as the independent variable, with employers as the control group. The results are presented in Model 2 of Table 5 and graphed in Fig. 5.

The Model 2 shows that informal regular workers have the lowest poverty risk, which can be explained by the fact that most of them have more stable incomes and tend to work with employment contracts. Outsourced workers/home-based workers and informal casual workers have the next lowest poverty risks. In contrast to the WIEGO model, employers and own account operators have high poverty risks. While migrant informal workers as a whole are generally in precarious living conditions due to their lack of urban residential status (Huang 2009), differences exist in different employment status. Although the higher economic insecurity of employers and own account operators diverge with the WIEGO model, this is not in conflict with some studies such as Horemans and Marx (2017) who found that self-employed workers generally face much higher poverty risks than contract workers. Here, the reason for employers’ high poverty risk might be associated with the large income differences within the employer group and business difficulties they faced. Further analysis of the data shows that the standard deviation of employers’ income is the largest among all types of informal workers. And a considerable proportion of them had low monthly incomes below 5000 yuan and some of them had negative incomes. Most of these economically disadvantaged employers had business in wholesale, retailing and catering service sectors. This indicates that these employers were facing business difficulties during the period of investigation. As to own account operators, they are mostly street vendors, tricycle porters, and motorbike drivers, who are disadvantaged in the labour market and have no choice but to earn income by self-employment (Huang et al. 2020). They are often subject to evictions and bans by city governments, resulting in their precarious business and living conditions (Huang et al. 2014). It is suggested the poverty risk of informal workers should be understood by considering their specific socio-economic situations in the places where they work and live.

Gender and informality

According to the WIEGO model, the proportion of females decreases as the tier of informal employment rises. We transformed the informal employment tiers into dummy variables and conducted a binary logit regression on the gender variable with the employer tier as the control group, to test in what sense the informal workers at different tiers fit the model. The results are shown in Model 3 of Table 5 and graphed in Fig. 6.

The results of Model 3 show that the highest proportion of females in the informal employment tiers is among informal regular workers, followed by informal casual workers and own account operators, with a lower proportion of females among employers and outsourced workers/home-based workers. Hence, the relationship between informal employment tier and gender ratio in the case of Chinese informal workers supports the WIEGO model in that employers are predominantly men, but diverges from it in that the proportion of females is relatively low (i.e. not predominantly women) for outsourced workers/home-based workers. One reason for this difference may be that in the developing countries the WIEGO model focuses on, job opportunities are limited for women as a result of economic underdevelopment, and socio-cultural norms discourage women’s mobility and participation in wage employment, forcing them to become home-based workers. In China, however, women can work as they wish. They usually leave their parents and children behind in their hometowns and go out to search for jobs. In addition, the rapid industrialisation in southern China, driven by global capital, generated a large number of jobs in factories. Particularly in the electronics and garment manufacturing sectors, female migrant workers can easily find wage employment. Female workers are usually favored by factory employers because they are more docile than men (Siu 2017). The results suggest that examining the relationship between informal employment and gender needs to take into consideration the structure of employment opportunities available to women in the local labour market.

Conclusion and discussion

This paper has sought to examine the working conditions of informal employment in China and highlight its heterogeneity by focusing on migrant workers who make up the major body of the informal workforces. In so doing it presents the first test of the WIEGO model on the relationship between informality, income, poverty and gender. Consistent with the literature, inequality exists significantly between informal and formal workers. Informal workers have lower economic incomes, and longer working hours than formal workers. This paper contributes to the literature by revealing that the inequality exists within the group of informal workers as significant as between the informal and formal cohorts. Informal workers in different employment statuses are in highly heterogeneous working conditions. As shown in this study, informal regular workers have the best working conditions among all informal employment tiers, informal casual workers and outsourced workers/home-based workers follow up, and own account operators and employers are in the worst working conditions. Nuanced differences emerge when looking into the specific components of working conditions. While incomes do not increase linearly with the employment tiers ranked by the WIEGO, there is a pattern in which employers have the highest incomes while own account operators earn the lowest. This economic inequality becomes more salient when looking at the fabric of work intensity in which the lowest paid own account operators work the longest hours among all informal employment tiers. Degrees of employment precarity and social security differ among different employment tiers. Informal regular workers have written contracts while other tiers of workers are more likely to have not. However, informal regular workers with written labour contracts are more likely to lack medical insurance, while employers and other tiers of workers are more likely to opt for medical insurance. Social support is distributed unevenly among informal workers. Informal regular workers are more likely to have union support due to their employment status. Informal regular workers, employers and own account operators are more likely to receive community support than the other two tiers of workers.

Analysis of the informal workers with different employment statuses allows an evaluation of the WIEGO model on the heterogeneity in income, poverty risk and gender ratio in different tiers of informal workers. The results are not fully consistent with the WIEGO model. While it is verified that employers have the highest income, the pattern does not completely follow the WIEGO model in which the income increases with the rise of the employment tiers from outsourced workers/home-based workers to employers. Our test confirms the gender segmentation suggested by the WIEGO in that employers are predominantly men, but is not in support of the dominance of female workers in outsourced/home-based employment. The results present a considerably different pattern on the distribution of poverty risks among informal workers in that employers are at the highest level, which is contrary to the WIEGO model in which they are at the lowest level. However, these inconsistencies do not mean that the WIEGO model is invalid. Rather, the existing convergence and divergence between the model and Chinese reality suggests the complexities and plurality in the heterogeneity of the informal employment. It can be argued that regional varieties exist in the pattern of the heterogeneity of informal employment in the world. As shown in this paper, the pattern of differences in economic income, poverty risk and gender structure within informal employment groups in China can be understood by examining the local characteristics of informal employment. This argument echoes the view of informal economies as the production of a cocktail of local political, economic and social dynamics (Williams and Windebank 2001; Chen and Carré 2020). It highlights the questions not only on the inequality rooted in the heterogeneous nature of informal employment, but also on the patterns the inequality unfolds in different geographical contexts. The question of the worldwide applicability of the WIEGO model calls for critical research on variegated landscapes of working conditions in the informal economies in the global South and North.

The paper has some policy implications. First, informal employment policies should be disaggregated and made with the consideration of differences in employment statuses of informal workers as they face very different difficulties and problems. Target-oriented policies are necessary to meet specific needs of informal workers with different employment tiers and gender structures. Second, education is important for the improvement of the working conditions of informal workers. The higher education attainment, the higher income informal workers earn and the lower work intensity they get. Supportive measures should be oriented toward providing equal education and training opportunities for informal workers to advance their human capital. Third, the lack or the weakness of associational power is a major challenge for the protection of informal employment. This is a structural question as the rise of neoliberal and flexible capital accumulation regime have been dismantling and weakening workers’ organisational power. The situation in the informal economy is worse as informal workers are mostly in unstable labour relations and spatially scattered, which restricts the formation of class consciousness and their capabilities of organisation. The paper shows that informal regular workers with employment contracts are more likely to gain union support. This exposes the inherent restriction in empowering informal workers given that most of them lack labour contracts. Inventing ways of organisation and empowering informal workers is a crucial institutional and political challenge for reducing inequality in the contemporary informalising world of work and employment.

Data availability

The China Migrants Dynamic Survey (CMDS) data used in this paper is sourced from the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China (NHCPRC) database. The authors have no right to disclose or distribute the data without the permission from NHCPRC as the data provider. However, researchers can acquire the data by applying for permission from the NHCPRC (https://www.chinaldrk.org.cn/wjw/#/home). Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Abramo L (2022) Policies to address the challenges of existing and new forms of informality in Latin America. Social Policy Series No. 240, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Santiago

Altenried M (2024) Mobile workers, contingent labour: migration, the gig economy and the multiplication of labour. Environ Plann A 56(4):1113–1128. 0308518X211054846

Amarante V, Arim R (2017) Inequality and informality revisited: the Latin American case. Int Labour Rev 162:431–457. https://doi.org/10.1111/ilr.12379

Anne Visser M, Guarnizo LE (2017) Room for manoeuvre: rethinking the intersections between migration and the informal economy in post-industrial economies. Popul Space Place 23(7):e2085. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2085

Bauder H (2008) Citizenship as capital: the distinction of migrant labor. Alternatives 33(3):315–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/030437540803300303

Benería L, Berik G, Floro M (2016) Gender, Development, and Globalization: Economics as if All People Mattered. Routledge, New York

Bhan N, Rao N, Raj A (2020) Gender differences in the associations between informal caregiving and wellbeing in low- and middle-income countries. J Women’s Health 29(10):1328–1338. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2019.7769

Bonnet F, Vanek J, Chen M (2019) Women and men in the informal economy: a statistical brief. Available at https://www.wiego.org/publications/women-and-men-informal-economy-statistical-brief. Accessed on 9 December 2023

Brummund P, Mann C, Rodriguez-Castelan C (2018) Job quality and poverty in Latin America. Rev Dev Econ 22(4):1682–1708. https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12512

Burchielli R, Delaney A, Goren N (2014) Garment homework in Argentina: drawing together the threads of informal and precarious work. Econ Labour Relat Rev 25(1):63–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1035304613518476

Cassirer N, Addati L (2007) Expanding women’s employment opportunities: informal economy workers and the need for childcare. Available at https://www.ilo.org/publications/expanding-womens-employment-opportunities-informal-economy-workers-and-need. Accessed on 10 May 2024

Castells M, Portes A (1989) World underneath: the origins, dynamics, and effects of the informal economy. In: Portes A, Castells M, Benton L (eds.) The Informal Economy: Studies in Advanced and Less Developed Countries. John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Chan KW, Liu T, Yang Y (1999) Hukou and non-hukou migrations in China: comparisons and contrasts. Int J Popul Geogr 5(6):425–448. 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1220(199911/12)5:6<425::AID-IJPG158>3.0.CO;2-8

Charmes J (1998) Informal sector, poverty and gender: a review of empirical evidence. Available at https://www.wiego.org/publications/informal-sector-poverty-and-gender-review-empirical-evidence. Accessed on 10 May 2024

Chen G, Hamori S (2013) Formal and informal employment and income differentials in urban China. J Int Dev 25(7):987–1004. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1825

Chen M (2005) Helsinki (2005) Rethinking the informal economy: linkages with the formal economy and the formal regulatory environment. WIDER Research Paper, No. 2005/10. The United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER), Helsinki, Available at https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/63329/1/488006546.pdf Accessed on 20 August 2023

Chen M (2012) The informal economy: definitions, theories and policies. WIEGO Working Paper No 1, Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO), Manchester

Chen M (2014) Informal employment and development: patterns of inclusion and exclusion. Eur J Dev Res 26(4):397–418. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2014.31

Chen M (2016) The informal economy: recent trends, future directions. N Solut 26(2):155–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1048291116652613

Chen M, Vanek J, Carr M (2004) Mainstreaming Informal Employment and Gender in Poverty Reduction: A Handbook for Policy-Makers and Other Stakeholders. Commonwealth Secretariat, London

Chen M, Vanek J, Lund F, Heintz J, Jhabvala R, Bonner C (2005) Progress of the world’s women 2005: women, work and poverty. Available at https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Headquarters/Media/Publications/UNIFEM/PoWW2005_eng.pdf. Accessed on 10 May 2024

Chen M, Vanek J (2013) Informal employment revisited: theories, data and policies. Indian J Ind Relat 48(3):390–401

Chen M, Lund F (2016) Overcoming barriers and addressing gender dimensions in universal health care for informal workers: lessons from India and Thailand. In: Handayani SW (ed.) Social Protection for Informal Workers in Asia. Asian Development Bank, Philippines, p 356–393

Chen M, Carré F (2020) The Informal Economy Revisited: Examining the Past, Envisioning the Future. Routledge, London

Chen MX, Huang XR, Huang GZ, Yang YS (2021) New type of urbanization and informal employment: size, pattern and social integration. Prog Geog 40(1):50–60. (in Chinese)

Devlin RT (2018) Asking ‘Third World questions’ of First World informality: using southern theory to parse needs from desires in an analysis of informal urbanism of the global North. Plan Theory 17(4):568–587. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095217737347

Eurofound and International Labour Organization (2019) Working conditions in a global perspective. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, and International Labour Organization, Geneva

Fields GS (1990) Labour market modelling and the urban informal sector: theory and evidence. In: Turnham D, Salomé B, Schwarz A (eds.) The Informal Sector Revisited. Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development, Paris, p 49–69

Gasparėnienė L, Remeikienė R, Williams CC (2022) Theorizing the informal economy. In: Gasparėnienė L, Remeikienė R, Williams CC (eds.) Unemployment and the Informal Economy: Lessons From a Study of Lithuania. Springer Briefs in Economics, Springer, p 7–60

Horemans J, Marx I (2017) Poverty and material deprivation among the self-employed in Europe: an exploration of a relatively uncharted landscape. IZA Institute of Labor Economics, Bonn, https://docs.iza.org/dp11007.pdf

Huang PCC (2009) China’s neglected informal economy: reality and theory. Mod China 35(4):405–438. https://doi.org/10.1177/009770040933315

Huang GZ, Xing ZG, Wei CZ, Xue DS (2022) The driving effect of informal economies on urbanization in China. J Geog Sci 32(5):785–805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11442-022-1972-y

Huang GZ, Xue DS, Guo Y, Wang CJ (2020) Constrained voluntary informalisation: analysing motivations of self-employed migrant workers in an urban village, Guangzhou. Cities 105:102760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102760

Huang GZ, Xue DS, Li ZG (2014) From revanchism to ambivalence: the changing politics of street vending in Guangzhou. Antipode 46(1):170–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12031

ILO (2002) Decent work and the informal economy. Available at https://webapps.ilo.org/public/english/standards/relm/ilc/ilc90/pdf/rep-vi.pdf. Accessed on 10 May 2024

ILO (2013) The informal economy and decent work: a policy resource guide supporting transitions to formality. Available at https://www.ilo.org/publications/informal-economy-and-decent-work-policy-resource-guide-supporting-0. Accessed on 10 May 2024

ILO (2018) Women and men in the informal economy: a statistical picture (third edition). Available at https://www.ilo.org/publications/women-and-men-informal-economy-statistical-picture-third-edition. Accessed on 10 May 2024

ILO (2021) The role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work. Available at https://www.ilo.org/publications/flagship-reports/role-digital-labour-platforms-transforming-world-work. Accessed on 8 May 2024

ILO (2023) World employment and social outlook: trends 2023. Available at https://www.ilo.org/publications/flagship-reports/world-employment-and-social-outlook-trends-2023. Accessed on 10 May 2024

Kannan KP (2017) Interrogating Inclusive Growth: Poverty and Inequality in India. Routledge, New Delhi

Kim K (2022) The impact of job quality on organisational commitment and job satisfaction: the moderating role of socioeconomic status. Econ Ind Democr 43(3):1391–1419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X221094875

Kuptsch C, Charest É (2021) The future of diversity. International Labour Office, Geneva, https://www.ilo.org/publications/major-publications/future-diversity

Lotta G, Kuhlmann E (2021) When informal work and poor work conditions backfire and fuel the COVID-19 pandemic: why we should listen to the lessons from Latin America. Int J Health Plann Manag 36(3):976–979. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.3104

Marcelli E, Williams CC, Joassart P (2010) Informal Work in Developed Nations. Routledge, London

Qu X (2012) Wage gap between formal employment and informal employment in urban China based on income inequality decomposition of informal heterogeneity. South China J Econ 4:32–42. (in Chinese)

Rodríguez-Modroño P (2021) Non-standard work in unconventional workspaces: self-employed women in home-based businesses and coworking spaces. Urban Stud 58(11):2258–2275. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980211007406

Sassen S (1996) Whose city is it? globalization and the formation of new claims. Public Cult 8(2):205–223. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-8-2-205

Segbenya M, Akorsu AD, Saha D, Enu-Kwesi F (2022) Exploring gendered perspectives on working conditions of solo self-employed quarry workers in Ghana. Cogent Soc Sci 8(1):2098624. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2098624

Sethuraman SV (1998) Gender, informality and poverty: a global review. The World Bank, Washington, DC, https://www.wiego.org/sites/default/files/publications/files/Sethuraman-Gender-Informality.pdf

Shapland J, Heyes J (2017) How close are formal and informal work? Int J Socio Soc Pol 37:374–386. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-06-2016-0071

Siu K (2017) Labor and domination: worker control in a Chinese factory. Polit Soc 45(4):533–557. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329217714784

Toksöz G (2018) Irregular migration and migrants’ informal employment: a discussion theme in international migration governance. Globalizations 15(6):779–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2018.1474040

United Nations (2015) Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Available at https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda. Accessed on 6 May 2024

United Nations Development Programme (2015) Human development report: work for human development. Available at https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2015. Accessed on 6 May 2024

Wang J, Fang LC, Lin Z (2016) Informal employment in China: recent development and human resource implications. Asia Pac J Hum Resou 54(3):292–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12099

World Health Organization (2006) The world health report 2006: working together for health. Available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241563176. Accessed on 6 May 2024

Williams CC (2014) The informal economy and poverty: evidence and policy review. Available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2404259. Accessed on 18 August 2023

Williams CC, Bezeredi S (2018) Explaining and tackling the informal economy: a dual informal labour market approach. Empl Relat 40(5):889–902. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-04-2017-0085

Williams CC, Horodnic IA (2019) Evaluating working conditions in the informal economy: evidence from the 2015 European Working Conditions Survey. Int Socio 34(3):281–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580919836666

Williams CC, Lansky MA (2013) Informal employment in developed and developing economies: perspectives and policy responses. Int Labour Rev 152(3-4):355–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1564-913X.2013.00196.x

Williams CC, Round J (2007) Entrepreneurship and the informal economy: a study of Ukraine’s hidden enterprise culture. J Dev Entrep 12(1):119–136. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1084946707000587

Williams CC, Windebank J (2001) The growth of urban informal economies. In: Paddison R (ed) Handbook of Urban Studies. Sage, London, p 308–322

Yeh HJ (2015) Job demands, job resources, and job satisfaction in East Asia. Soc Indic Res 121:47–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0631-9

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42122007, 41930646), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2024A1515010939), and the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou City (2024A04J9879).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Gengzhi Huang, conceptualization, research design, data analysis and writing; Bowei Cai, literature review, data analysis, manuscript revision, and writing; Shuyi Liu, data analysis and writing; Desheng Xue, research design and methodological support.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study exclusively conducted secondary analysis of de-identified data, with no human beings participating in the research process. The analysis in this study was based on the publicly accessible data—the China Migrants Dynamic Survey (CMDS) dataset conducted by the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China (NHCPRC). The CMDS dataset was completely anonymized. This study using the CMDS data was reviewed and approved by the School of Geography and Planning of Sun Yat-sen University.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all CMDS respondents by the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China (NHCPRC) that conducted the survey. The CMDS data used in this study has been completely anonymized. This study thus contains no any identifiable information on CMDS respondents.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, G., Cai, B., Liu, S. et al. Analysing the heterogeneity in working conditions of migrant informal workers in China: a test of the WIEGO model of informal employment. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 882 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03405-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03405-7