Abstract

Financial restatements significantly measure financial reporting quality, introducing uncertainty, undermining trust, and triggering adverse reactions in financial markets. This paper examines how the supply of tax information affects financial restatements. The literature lacks compelling evidence about the relationship between tax information and financial restatements. From one perspective, enhancing the transparency of corporate tax information can diminish the occurrence of financial restatements. From another perspective, increasing the accessibility of tax information could lead to increased financial restatements. We reconcile these competing associations, exploiting a natural experiment induced by the rollout of Taxation Administration Information System III (CTAIS-3) in China. Using a difference-in-difference approach, we find that firms in areas implementing CTAIS-3 experience a significant decrease in financial restatements. Our results remain robust across various indicators of financial reporting quality. Furthermore, we demonstrate that information asymmetry is a driving factor behind our results, emphasizing the government’s proactive role in enhancing the quality of corporate financial disclosure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Existing research on tax information primarily focused on taxation and corporate decision-making, notably in areas such as entrepreneurship (Edwards and Todtenhaupt, 2020; Djankov et al., 2010), innovation (Akcigit et al., 2022; Li et al., 2021a; Mukherjee et al., 2017), investment activities (Ohrn, 2018; Becker et al., 2013; Poterba and Summers, 1983) and corporate risk-taking (Armstrong et al., 2019; Langenmayr and Lester, 2018; Ljungqvist et al., 2017). However, there needs to be more research investigating the influence of tax information on financial reporting quality, particularly about the financial restatements.

According to Karpoff et al. (2017), financial restatements may stem from the negligence of accounting personnel or, in more severe cases, arise from the misconduct of company executives in achieving analysts’ expectations through earnings management. These financial restatements can result in adverse economic consequences, including negative reactions in the capital markets (Bauer et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2016), increased cost of capital (Kravet and Shevlin, 2010; Hribar and Jenkins, 2004), and diminished investor trust (Elliott et al., 2018; Garrett et al., 2014). Given the significant impact of financial restatements on capital markets, investigating how tax information influences financial restatements has become a crucial topic (Amel-Zadeh and Zhang, 2015; Garrett et al., 2014).

The theory proposed by Bartov and Bodnar (1996) suggests that increasing the accessibility of tax information may improve a company’s financial information quality. According to the theory, managers consider the costs of preparing and disclosing information against the potential benefits. Adopting new information technology can disrupt this balance, leading managers to enhance information disclosure if they expect the benefits to outweigh the implementation costs. Implementing a tax information system can make it harder for firms to undertake tax evasion through fraudulent activities or fund transfers (Overesch and Wolff, 2021; Bennedsen and Zeume, 2018). As a result, companies may put more effort into ensuring the accuracy and completeness of their financial reports to avoid higher legal and reputation costs (Gallemore et al., 2014).

However, the literature lacks conclusive evidence on the relationship between tax information and financial restatements. From one perspective, enhancing the transparency of corporate tax information may reduce financial restatements. Previous research indicates that tax information allows the public to gain deeper insights into the operational status of corporations (Hoopes et al., 2018; El Ghoul et al., 2011). For example, tax information can help stakeholders identify the aggressive nature of a company’s tax position (Overesch and Wolff, 2021; Lisowsky et al., 2013; Frank et al., 2009), curb profit shifting (Overesch and Wolff, 2021; Hope et al., 2013; Dyck and Zingales, 2004), and provide incremental information on corporate governance (Dhaliwal et al., 2013; Guedhami and Pittman, 2008; Kumar and Visvanathan, 2003). Because tax information often reflects the economic realities underlying a company’s operations, it provides a vital means to corroborate the financial statements delineated in annual reports. This assertion is supported by De Simone et al. (2015), Dhaliwal et al. (2013), and Hanlon and Heitzman (2010), who highlight the integral role tax data plays in the verification of financial documentation. Through enhanced information transparency, tax information may mandate firms to adopt a more discerning approach to disclosing financial information and push financial reporting quality.

From another perspective, some research indicates that increasing the accessibility of tax information may raise the likelihood of financial restatements. When tax information becomes more transparent, companies may face increased tax scrutiny and tax burdens (Overesch and Wolff, 2021; Joshi et al., 2020; Kerr, 2019), which may worsen their financial conditions (Waseem, 2018; Goh et al., 2016). In such cases, companies might adopt more aggressive earnings management measures to meet analysts’ expectations (Cazier et al., 2015; Erickson et al., 2013; Monem, 2003), diminishing financial reporting quality. Moreover, although the tax information system increases the transparency of tax information, it does not guarantee that all instances of tax-related financial manipulation will be exposed or detected. For example, managers can inflate profits on tax returns to prevent raising suspicions from stakeholders (Lennox et al., 2013; Dhaliwal et al., 2004). Erickson et al. (2004) report an analysis of 27 fraudulent firms that overstate pre-tax profits, but none of these financial frauds were discovered by the IRS (Lennox et al., 2013). Joshi et al. (2020) also show that because of the balancing effects of different tax avoidance practices that escape scrutiny, certain tax information does not significantly affect corporate tax-related behaviorFootnote 1.

This study attempts to reconcile the competing relationship between tax information and financial restatements. The greatest empirical challenge is identifying a causal relationship without reverse causality and omitted variables. First, sharing tax information may enhance a company’s financial information quality, and companies may adjust financial information to alter their effective tax rate. Second, the company’s endogenous factors may determine tax information and financial restatements. The financial condition, governance structure, management decisions, and other company characteristics may collectively affect the dynamics of tax information and financial restatements. Finally, tax information and corporate financial restatements may be related to unobserved economic and financial factors.

To mitigate endogeneity concerns, we utilize a natural experiment, namely the third phase of the China Tax Administration Information System (CTAIS-3), which leads to an exogenous surge in the availability of tax information (Xiao and Shao, 2020). This setup is appealing for several reasons. First, CTAIS-3 is a tax policy gradually implemented in various provinces in China since 2013. Specifically, CTAIS-3 is a tax management system through which companies must submit taxes, apply for digital invoices in standardized formats, and pay taxes through banks. Therefore, the CTAIS-3 facilitates exchanges of tax information between tax authorities and third-party institutions such as financial institutions, industrial and commercial bureaus, and social insurance departments. The motivation for using CTAIS-3 is to ensure the effective collection and analysis of tax information. Therefore, the implementation of CTAIS-3 serves as a predominantly exogenous event rather than being influenced by the quality of a company’s financial information. Secondly, due to CTAIS-3, the reduction in tax opacity is quite significant. For example, by the end of 2016, the State Administration of Taxation had established collaborative relationships with 32 government departments, sharing 190 types of information, including equity transfers, social insurance, and asset transactions. In addition, tax information is shared with the State Administration of Taxation to prevent cross-regional fund transfers and profit concealment. Thirdly, implementing CTAIS-3 allows us to examine the impact of tax information supply shocks while controlling for other unobservable firm features or economic factors. Given that the rollout of CTAIS-3 occurs gradually across various provinces, it is less likely to be simultaneously implemented with other potentially confounding projects in the same province. Therefore, by comparing the impact of financial restatements in regions where CTAIS-3 is implemented (treatment firms) and regions where CTAIS-3 is not implemented (control firms), we can discern the direct link between tax information and financial restatements.

Applying a difference-in-differences (DID) technique, we study the relationship between tax information and financial restatements using a panel of 3546 public Chinese firms from 2010 to 2019. In line with our hypothesis, the rise in the availability of tax information substantially diminishes financial restatements. Additionally, we observe that the inverse relationship between tax information supply and financial restatements is intensified for firms possessing higher levels of information asymmetry.

Our study makes the following contributions. First, it adds to the existing literature on the drivers behind accounting information quality. Existing literature explores the impact of audit expertise (Ahn et al., 2020; Gunn and Michas, 2018; Jayaraman and Milbourn, 2015), top management characteristics (Zhang, 2019; Feng et al., 2011; Efendi et al., 2007), institutional investors (Cahan et al., 2024; Samuels et al., 2021), and government enforcement (Blankespoor, 2019; DeHaan et al., 2015) on accounting information quality. Yet, more investigation is required to understand the influence of tax information on financial information quality. Compared with the most relevant studies (Dhaliwal et al., 2013; Kumar and Visvanathan, 2003), this paper addresses the endogeneity issues in corporate tax information reporting by establishing the CTAIS-3 information system in China. This CTAIS-3 reform is a government-led initiative that can be exogenous to firms.

Secondly, our research adds to the developing literature investigating the economic implications of tax information technology. Prior studies reveal that tax information exerts a significant influence on tax compliance (Hoopes et al., 2018; Lisowsky et al., 2013; Chan et al., 2010), internal control quality (Amberger et al., 2021; De Simone et al., 2015; Becker et al., 2013), and financial reporting (Balakrishnan et al., 2019; Hope et al., 2013; Frank et al., 2009). These studies collectively suggest that tax information technology is instrumental in shaping firms. However, further investigation is warranted to explore whether the public dissemination of tax information contributes to a reduction in financial restatements by firms. Therefore, we extend this line of research, demonstrating that the exogenous changes in tax information supply can reduce corporate financial restatements by enhancing the external information environment of firms.

Thirdly, our findings expand the literature regarding the spillover effects of government behavior. Scholarly consensus indicates that government behavior can significantly influence corporate conduct. Previous studies discuss how the government affects financial reporting and auditing by establishing information disclosure standardsFootnote 2, regulations, and market forces (e.g., Houston et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2010). Although discussions around the influence of government behavior on financial information quality are escalating, empirical evidence on the spillover effects of government behavior remains limited. We extend this line of research by studying the spillover effects of government behavior through a quasi-natural experiment. After the government establishes a large-scale tax data information system, the external information environment of businesses will improve, motivating them to enhance the quality of financial information proactively. Therefore, we provide additional evidence indicating that government behavior is essential in improving corporate financial disclosure.

Finally, our study provides pivotal insights to policymakers and stakeholders. A fair, competitive, and sustainable tax system is vital for a country’s future prosperity. The ongoing debate on tax information transparency is crucial to this discussion (Lisowsky et al., 2013). Supporters advocate for transparency, believing the increased transparency of tax information can effectively combat corporate tax evasion. However, opponents argue that such transparency may encroach upon corporate privacy rights (Bradbury, 2013). This article provides evidence that tax information transparency enhances corporate financial reporting quality. This finding carries important policy and regulatory implications, suggesting that digital tax enforcement mechanisms can yield beneficial outcomes. Moreover, our research indicates that other market participants, including investors, creditors, and suppliers, stand to gain from understanding the broader implications of tax information systems. By integrating the effects of tax transparency into their evaluation frameworks, these stakeholders can better comprehend a company’s financial information.

The following section provides an overview of the institutional background of the CTAIS-3 Reform in China and presents hypotheses. Section “Sample and descriptive statistics” contains a detailed account of the sample and data sources. Section “Empirical results” outlines empirical results. Section “Conclusions” concludes the study.

Institutional background and hypothesis development

Institutional backgrounds

The Chinese State Administration of Taxation (SAT) started the CTAIS-3 project in 2013 to fully promote tax collection and management information. This project steadily built up a national taxation information system across all provinces and cities in China and reached national coverage at the end of 2017. The CTAIS-3 does three measures: (1) establishing a unified technical platform covering all types of taxes; (2) Consolidating tax information at the national and provincial-level tax bureaus to facilitate data-sharing among geographically dispersed tax authorities; (3) sharing information with third parties such as financial institutions and other government departments to facilitate the utilization of tax credits.

The CTAIS-3 system can alleviate information asymmetry in two ways. First, CTAIS-3 reduces the prevalence of false invoices and enhances the reliability of firms’ operational information. After implementing CTAIS-3, firms can issue invoices in a standardized format through the system, with each invoice linked to a unique taxpayer. Therefore, tax authorities can quickly identify invoices without genuine transactions, thereby curbing income or profit manipulation. Additionally, through cooperation with banks, tax authorities can access information on abnormal fund transfers. As a result, CTAIS-3 makes it more difficult for businesses to manipulate income or profits by reducing the feasibility of false invoices and facilitating information exchange between tax authorities and society.

Secondly, CTAIS-3 lays the technical foundation for the social tax credit system. Aligned with the “Social Credit System Construction Plan” released by the Chinese State Council in 2014, the Chinese government encourages the establishment of a cross-departmental credit information-sharing mechanism. This mechanism includes sharing taxpayers’ basic information, transaction information, property retention and transfer information, and tax records. Tax authorities are also promoting cooperation with financial institutions such as banks. Companies can exchange “tax credits” for “bank credits” to facilitate standard debt contracts. In summary, with the establishment of CTAIS-3, firms’ business operations and transactions face heightened attention and oversight from tax authorities and society, effectively narrowing the information gap between companies and their stakeholders.

The implementation of CTAIS-3 commenced in 2013, starting from Chongqing, Shanxi, and Shandong. In 2014, CTAIS-3 extended to Guangdong, Henan, and Inner Mongolia. In 2015, the pilot program was expanded to include 14 additional provinces and regions, such as Jilin and Hainan. The project had expanded to achieve countrywide coverage by the close of 2016. The staged rollout of CTAIS-3 creates a quasi-natural experimental setting, allowing us to investigate the causal link between tax information accessibility and corporate financial restatements.

Hypothesis development

The previous literature suggests managers may engage in opportunistic financial restatements for corporate interests (e.g., Gao and Zhang, 2019; Pyzoha, 2015; Desai et al., 2006). Such opportunistic behaviors can trigger a range of detrimental economic outcomes, including adverse market reactions (Bauer et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2016), higher financing costs (Kravet and Shevlin, 2010; Hribar and Jenkins, 2004), and diminished investor trust (Elliott et al., 2018; Garrett et al., 2014). Therefore, the literature extensively explores how to curb opportunistic financial restatements (Cahan et al., 2024; Samuels et al., 2021; Cao and Pham, 2021). For example, previous research implies that external investors can exercise oversight and control over corporate managers, thereby reducing misreporting by companies (Elliott et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2018; Bird and Karolyi, 2016). Nonetheless, this perspective remains controversial. Specifically, other research suggests that the existence of external investors is linked to a decline in financial disclosure quality (Arif and De George, 2020; Bushee et al., 2019; Miller, 2002). This phenomenon is partially attributed to external investors’ challenges in obtaining comprehensive and timely company information. Companies may exploit asymmetric information to deliberately mislead investors, diminishing the quality of investor’s assessments regarding their conditions.

The issue of external investor monitoring’s ineffectiveness due to information asymmetry sparks researchers’ interest in how the information environment affects financial information quality. Chen (2016) finds that banks’ exceptional information acquisition and processing capabilities enable them to react to financial misreporting during restatement periods. Ashraf et al. (2020) find that audit committees’ information technology skills significantly improve corporate accounting quality, and Xiong et al. (2021) uncover that high-speed railway coverage significantly reduces corporate financial fraud by increasing the accessibility of corporate information. Overall, existing literature indicates that the external information environment is pivotal to improving corporate financial reporting quality.

As a crucial component of the information environment, tax information can facilitate investors to obtain higher-quality corporate information for external supervision, prompting companies to enhance financial disclosure quality. Prior literature shows that enhancing the accessibility of tax information can reduce information acquisition costs, improve the credibility of obtained information, and consequently enhance external supervision efficiency regarding companies’ financial information disclosure in several ways (Chiu et al., 2013; Dyck et al., 2010). First, tax information enhances the transparency of corporate operational conditions. For example, Dhaliwal, Kaplan, Laux (2013) and Kumar and Visvanathan (2003) found that managerial decisions concerning the valuation allowance for deferred tax assets offer additional insights into the enduring nature of accounting losses. Second, tax information enhances investors’ discernment of corporate disclosure. Prior studies document that tax information is an essential indicator for investors in evaluating corporate stock prices (Bauckloh et al., 2021; Hoopes et al., 2018).

In summary, implementing CTAIS-3, characterized by providing incremental tax information, contributes to heightened efficiency in external supervision, which induces a more cautious approach from companies in disclosing financial information. Consequently, there is an enhancement in the overall quality of corporate financial disclosure, accompanied by a reduction in financial restatements. We put forward our first hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 1A: Financial restatement decreases after the enactment of CTAIS-3.

Tax information transparency may elevate the likelihood of financial restatements. Specifically, the heightened transparency associated with tax information significantly diminishes the potential for companies to engage in deceptive tax declarations to evade taxes, which increases the corporate tax burden to some extent. Research demonstrates that an increase in the tax burden may hurt the quality of financial information (Waseem, 2018; Romanov, 2006). Maydew (1997) states that an increase in the tax burden corresponds with earnings management behavior in corporate financial statements. Chen and Schoderbek (2000) suggest that changes in tax policies may lead companies to make “one-time adjustments” in their financial statements, which could reduce the consistency of financial disclosures. The complexity and variability of tax policies may increase companies’ accounting and tax-based proprietary costs, affecting the accuracy and reliability of financial information (Yost, 2023). CTAIS-3 enhances the tax supervision capabilities of the governments, which may increase the tax burden and financial restatements of firms. Accordingly, we put forth our second hypothesis, which states:

Hypothesis 1B: Financial restatement increases after the enactment of CTAIS-3.

Sample and descriptive statistics

Sample

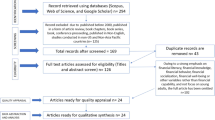

Our data came from the CSMAR (China Stock Market and Accounting Research) database, comprising financial and stock market variables and corporate financial restatements. We collected tax information data based on the rollout of the “CTAIS-3” project in various provinces and cities in ChinaFootnote 3. Following Srinivasan et al. (2015), our outcome variable, financial restatements (Restate), is a binary measure. It equals 1 if a company conducts financial restatements in a given year and 0 otherwise. We started with annual observations for 29,319 companies listed on the Shenzhen and Shanghai stock exchanges between 2010 and 2019. Our sample period began in 2010 when the China Securities Regulatory Commission revised the “Regulations on Information Disclosure and Reporting for Companies Issuing Securities to the Public” in 2010. Besides, we limit our sample period to 2019, recognizing the dramatic impact the COVID-19 pandemic had on business functions beginning in 2020, which could affect our coefficients. We excluded 2886 firm-year data points with missing values for the control variables and 211 singleton observations, resulting in a final sample of 26,222 observations from 3546 distinct companies.

The company-level control variables used as factors in investment decisions also come from the CSMAR database. Specifically, following Chin and Chi (2009), Amel-Zadeh and Zhang (2015), and Jayaraman and Milbourn (2015), we include company size (Size), company performance (ROA), and financial health (Lev). In addition, we also include liquidity (CashHold) to control for cash constraints (Cheng and Farber, 2008) and Tobin’s Q (TobinQ) to account for investment opportunities (Durnev and Mangen, 2009; Bergstresser and Philippon, 2006) and the proportion of independent directors (Indep) to control for internal control mechanisms (Cheng et al., 2016; Srinivasan, 2005). We also collect data on three provincial-level variables from the “China Statistical Yearbook” to control for provincial characteristics, including per capita GDP (GDP), fiscal revenue (FiscInc), and average income at the province level (AvgSalary).

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics of the dependent, independent, and control variables. The statistical mean of the outcome variable “Restate” is 0.243, suggesting that approximately 24.3% of the observations involved financial report restatements, consistent with other research findings (Palmrose et al., 2004). The mean firm size in the sample is 22.20 (logarithm of total assets in RMB), the mean leverage ratio is 43.6%, the mean ratio of cash and cash equivalents to total assets is 16.7%, the mean ROA is 3.6%, the mean Tobin’s Q is 2.05, and the mean ratio of independent director is 29.2%, which is similar to the statistical data from other studies (Lennox et al., 2018).

Empirical results

Baseline regression

To examine the causal relationship between the launch of the CTAIS-3 system and corporate financial restatements, we adopt the staggered difference-in-differences approach to estimate the regression model specified below:

The indices i and t correspond to firms and years, respectively. \({CTAIS}\) is a binary variable that equals 1 if the firm is in a region (province or prefectural city) where the CTAIS-3 platform is launched, and 0 otherwise. \({X}_{{it}}\) is a vector of time-varying, firm-level control variables, and \({X}_{{pt}}\) is a vector of time-varying, province-level control variables. \({{Restate}}_{{it}}\) represents a measurement of corporate financial restatements, which equals 1 if the company i conducted financial restatements in year t. Otherwise, it equals 0. \({\varepsilon }_{i,t}\) is the error term. See Supplementary Table 1 for all variable definitions.

\(\,{\alpha }_{i}\) is the firm-fixed effect that accounts for time-invariant omitted firm characteristics and captures the treated \({{firm}}_{i}\) variable from the original DID model. \({a}_{t}\) is the year-fixed effect that controls for the impact of the specific year on the regression and captures the \({{Post}}_{t}\) variable from the original DID model. We cluster standard error at the firm level in all regressions.

The coefficient of focus is the one on CTAIS, as it measures the differential change in the financial restatements for treatment firms compared to control firms in the periods before versus after the launch of CTAIS-3. The DID technique helps eliminate biases introduced by persistent differences between the two groups or time-varying confounding factors (Imbens and Wooldridge, 2009). If the CTAIS-3 pilot significantly reduces financial restatements,\(\,{\beta }_{1}\) should be negative and statistically significant, and vice versa.

Table 2 displays the multivariate DID analysis results. The coefficient of \({CTAIS}\) is negative and statistically significant at the 1% level for Restate (−0.025, t = −2.51 and −0.031, t = −3.06 in Columns 1 and 2), suggesting that the exogenous increase in tax information results in a significant reduction in corporate financial restatements, which supports H1A. Specifically, the CTAIS-3 pilot results in a decrease of 3.1% in financial restatements, which is considerably and economically significant, considering the sample mean value of this ratio is only 24.3%.

Parallel assumption

We conjecture that the CTAIS-3 pilot represents a shock to firms’ information environment. A significant concern is that the pilot might be based on unobservable local economic and political characteristics. Therefore, to establish the credibility of the DID specification, we must fulfill the parallel trends assumption, which necessitates there being no statistically significant difference in corporate financial restatements between the treatment and control groups before the implementation of the CTAIS-3 system.

To tackle the above concerns, we employ the technique used by Bertrand and Mullainathan (2003) to analyze the time-varying patterns of corporate financial restatements surrounding the establishment of the CTAIS-3 system by estimating the following equation:

Where d[t + k], –3 ≤ k ≤ 3, is a binary variable equals 1 for each of the three years preceding and three years following the launch of the CTAIS-3 system and zero otherwise. d[t + 3] represents the impact of CTAIS-3 system on and after t + 3. d[t − 4], omitted from the model to prevent collinearity, represents the impact of the CTAIS-3 system on and before t − 4. The remaining variables included in the analysis are consistent with those used in the baseline DID specification.

The key coefficients are \({\beta }_{-1}\), \({\beta }_{-2}\), and \({\beta }_{-3}.\) If there is any pre-existing trend in corporate financial restatements between the treated and control firms before the launch of CTAIS-3, we would see statistically significant estimates for \({\beta }_{-1}\), \({\beta }_{-2}\), and \({\beta }_{-3}\). We report the dynamic DID results in Table 2, Columns (3) and (4). The coefficients on \({\beta }_{-1}\), \({\beta }_{-2}\), and \({\beta }_{-3}\) are statistically insignificant in all regressions, implying that the parallel assumption underlying the DID approach is satisfied. The absence of any pre-trends helps alleviate concerns about reverse causality. Moreover, the coefficients on d[t], d[t + 2], and d[t + 3] are significantly positive, implying that the launch of the CTAIS-3 system can aggravate firms’ shift backward from restating their financial reports both in the short term and over the long term.

Underlying mechanisms

This section examines the mechanisms that drive the effect of a tax information system on corporate financial restatements.

The efficacy of CTAIS-3 in influencing corporate financial restatements may be contingent on the extent of information asymmetry between firms and stakeholders. Stock price synchronicity (Synchronic) is a standard measure to access information asymmetry as it reflects the degree to which firm-level information is impounded into share prices. A higher Synchronic suggests a less transparent information environment and higher levels of information asymmetry (Chan and Chan, 2014; Crawford et al., 2012; Piotroski and Roulstone, 2004). Therefore, we follow Piotroski and Roulstone (2004) and partition the sample based on stock price synchronicity (Synchronic). Panel A of Table 3, Columns 1 and 2 divide the sample by stock price synchronicity. The coefficient of CTAIS is insignificant in Column 2 but is −0.052 (t = −3.54) in Column 1, verifying information asymmetry as an essential mechanism.

Next, previous research suggests that higher analyst forecast error suggests less firm-specific information being shared in the capital markets (Jiang and Yuan, 2018; Lang et al., 2012; Flannery et al., 2004; Krishnaswami and Subramaniam, 1999). We then divide the sample based on analyst forecast error. Following Eames and Glover (2003), we calculate Analyst forecast error (Ferror) as the absolute difference between the means of the actual and predicted earnings, scaled by the equity market values. Columns 3 and 4 partition sample by analyst forecast error. The coefficient of CTAIS is insignificant in Column 4 but is −0.028 (t = −1.85) in Column 3.

Third, the link between tax information and corporate financial restatements may exhibit greater resilience in higher bid-ask spread. The reason is that when information asymmetry is high, informed investors can exploit their informational advantage to the disadvantage of less informed investors (Krinsky and Lee, 1996). In such scenarios, uninformed investors will reduce their bid prices and raise their ask prices to safeguard themselves against the anticipated losses from trading with better-informed counterparties, leading to a higher bid-ask spread (Amiram et al., 2016; Wittenberg-Moerman, 2008; Affleck‐Graves et al., 2002). We calculate the bid-ask spread (Spread) by Roll’s (1984) approach. Columns 5 and 6 partition the sample by bid-ask-spread. The coefficient of CTAIS is insignificant in Column 6 but is −0.044 (t = −2.20) in Column 5.

Fourth, existing literature suggests that the participation of institutional investors can help mitigate corporate misconduct by increasing firm transparency and information production (Wu et al., 2016; Cheng et al., 2010; Chung et al., 2002). We then segment the sample according to institutional ownership (Institution). Panel B Columns 1 and 2 split the sample by the percentage of shares institutional investors hold (Tong and Zhang, 2024). The coefficient of CTAIS is insignificant in Column 2 but is −0.034 (t = −2.22) in Column 1.

Fifth, Existing studies find that social media in China (e.g., online stock forums), which operate independently of government press control, can leverage the “wisdom of the crowd” to provide valuable information to society (Wong et al., 2023; Bartov et al., 2018; Blankespoor et al., 2014)—Panel B Columns 3 and 4 departure sample based on the number of online stock forums. The coefficient of CTAIS is insignificant in Column 4 but is −0.056 (t = −3.85) in Column 3.

Finally, recent literature suggests that information asymmetry is associated with geographic proximity. Nearby investments have an informational advantage because investors can monitor firms more efficiently due to reduced travel time (Baik et al., 2010; Ivković and Weisbenner, 2005; Coval and Moskowitz, 2001). We then separate the sample based on the minimum distance from the firm to a local bank. The results show that the coefficient of CTAIS is −0.025 (t = −1.72) when the firm is located near the local bank but is −0.035 (t = −2.50) when the firm is far away from the local bank.

The findings above indicate that the impact of a CTAIS-3 launch on firms’ financial restatements is significant only when firms are under information asymmetry. Therefore, the increased transparency between firms and their investors is one channel through which the launch of a tax information system affects firms’ financial restatements.

Additional analyses

State-owned Enterprises and Tax Avoidance

The strength of CTAIS-3’s information effect can depend on factors like government ownership and companies’ tax avoidance behavior. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) tend to be less susceptible to the influence of CTAIS-3 compared to non-state-owned enterprises (non-SOEs). SOEs have weaker financial motives than non-SOEs because they often prioritize social and political objectives over economic goals. Moreover, SOEs generally enjoy a more secure financial position due to government support (Liu et al., 2021; Du, Tang and Young, 2012; Cull and Xu, 2005). Additionally, SOEs are subject to more extensive oversight by the government, such as through periodic government audits and anti-corruption initiatives (Hou et al., 2022; Li et al., 2021b). Thus, the exogenous increase in tax information is more likely to influence Non-SOEs than SOEs.

In addition, the influence of introducing the CTAIS-3 might be more decisive in firms with a higher tax avoidance level. For example, firms that evade tax more can reduce tax evasion after the introduction of CTAIS-3 due to increased transparency in tax enforcement (Overesch and Wolff, 2021; Joshi et al., 2020; Kerr, 2019). Therefore, these companies may show a stronger correlation between the CTAIS-3 and financial information quality. In contrast, even if the introduction of the CTAIS-3 strengthens external supervision for companies with solid tax compliance, it is difficult to improve their tax compliance further.

We then compare the influence of CTAIS-3 on corporate financial restatements of SOEs to non-SOEs. Table 4 Panel A, Columns 1 and 2, show a sample breakdown dependent on whether the firm is an SOE. The coefficient of CTAIS is insignificant in Column 1 but is −0.033 (t = −2.57) in Column 2, confirming our expectation.

Columns 4 to 6 stratify the sample by the degree of tax avoidance. We calculate the tax avoidance measure by taking the five-year average of the gap between the statutory tax rate set by tax law and the actual tax rate paid by the firm (LRATE_diff) (Hanlon and Heitzman, 2010; Dyreng et al., 2008), as in Column 3 and 4, and book-tax-difference (Chen et al., 2022; Badertscher et al., 2019), as in Column 5 and 6. The coefficient of CTAIS is −0.036 (t = −2.77) in Column 3 and is −0.032 (t = −2.39) in Column 5, but it is statistically insignificant in Columns 4. The coefficient in Column 6 is −0.034 (t = −1.76). The findings suggest that the launch of CTAIS-3 had a more significant impact on financial restatements for non-SOEs and firms with higher tax avoidance levels.

High-technology, multinational, and large companies

Next, we investigated the variations in the effect of CTAIS-3 on financial reporting quality across different industries, company types, and firm sizes. Previous studies have shown that companies in the high-tech sector exhibit higher levels of information opacity (Mohd, 2005; Coff and Lee, 2003; Aboody and Lev, 2000). For example, Barron et al. (2002) reported that there is a lower level of consensus in analyst forecasts for high-tech firms due to the existence of a substantial amount of intangible assets. Palmon and Yezegel (2012) also contend that R&D investments create higher information asymmetry, potentially leading to lower informational content in the stock prices of high-tech companies. Therefore, the effects of CTAIS-3 may be more significant in the high-tech industry. Table 4 Panel B columns 1 and 2 display the heterogeneous influence of CTAIS-3 on restatements contingent on whether the company is in a high-tech industry. We obtained industry codes for the high-tech industry from the Chinese government’s websiteFootnote 4 and matched them with the company’s industry codes. We found that the coefficient of CTAIS is −0.050 in the first Column (t = −2.76) but is −0.023 (t = −1.85) in the second Column, confirming our expectations.

Besides, the impact of CTAIS-3 may be more significant in companies with overseas affiliates. Companies with overseas affiliates can exploit tax policy differences between countries or regions. They can minimize their tax liabilities to the greatest extent possible by shifting profits to tax havens (Overesch and Wolff, 2021; Bennedsen and Zeume, 2018; Dyreng et al., 2016). For example, Dyreng et al. (2019) found that companies establishing subsidiaries in tax havens have more significant tax uncertainty. The CTAIS-3 system establishes extensive cooperation and information-sharing relationships between the tax authorities and other departments such as customs and banks, thus reducing the possibility of companies manipulating profits to some extent. Panel B Columns 4 and 6 reflect the sample division based on whether the company has overseas affiliates. Based on data of the company’s overseas affiliates from the CSMAR database (including subsidiaries, joint ventures, and cooperative companies), we categorized companies with overseas affiliated companies as Multinational and those without overseas affiliated companies as Local, as shown in Columns 3 and 4. The coefficient of CTAIS is −0.033 (t = −2.07) in Column 3 but is statistically insignificant in Column 4.

Finally, CTAIS-3 may have a more significant impact on larger enterprises. Previous literature indicates that tax planning exhibits economies of scale (Rego, 2003). Large enterprises dedicate more resources toward tax evasion and are more adept at it (Brown and Drake, 2014; Dyreng et al., 2008; Hanlon et al., 2005). For example, Kotchen (2021) illustrates that the advantages provided by subsidies for oil, gas, and coal production are primarily accrued by a select group of large-scale enterprises. Dyreng, Hills, and Markle (2022) show that a small number of large enterprises drive most income-shifting activities in the United States. As a result, the impacts generated by the tax information system may be more pronounced in large enterprises. In Columns 5 and 6, we separate the sample by the median value of firm size. The coefficient of CTAIS is −0.055 in Column 5 (t = −3.88) but is statistically insignificant in Column 6.

These results show that CTAIS-3’s impact on corporate financial restatements is more significant for high-tech companies, companies with overseas affiliated companies, and larger companies.

Robustness tests

To strengthen the validity of our baseline findings, we undertook a diverse set of robustness checks to eliminate potential alternative explanations.

First, the introduction to CTAIS-3 reduces corporate financial restatements by mitigating information asymmetry, and it might generate the same results on other proxies of financial reporting quality. As such, we proceed to compute the subsequent variables of financial reporting quality, including the modified Jones model (EMJones) from Dechow et al. (1995) and the Dechow and Dichev (2002) model (EMDD) that represent earnings management, the auditor’s opinion type (Opinion) which equals 1 if the auditor of the firm provides a going-concern opinion and otherwise 0, C-score (Khan and Watts, 2009), and ACF score (Ball and Shivakumar, 2006) that represents the timeliness of the corporate response to bad news. Table 5 Panel A displays the results. We find robust and negative coefficients across all measurements of financial report quality, indicating that the exogenous increase of tax information indeed increases financial reporting quality.

Second, we test the robustness of our findings by employing different measures. We incorporate the natural logarithm of the number of financial report restatements conducted by a firm in a fiscal year (Restate_count) as the dependent variable. Table 5 Panel B Columns 1 and 2 show similar results (−0.016, t = −1.87 and −0.022, t = −2.51, respectively).

Third, to address the possibility that our findings may be influenced by the temporal trends in economic growth, urbanization, and natural and ecological environment that vary by province or industries, we follow Barrios et al. (2022) to control the province linear trend and industry linear trend in the primary regression and re-estimate Eq. (1) in Column 1 and 2 of Table 5 Panel C, and we add industry*year-fixed effect in Column 3. We continue to find negative and statistically significant coefficients of CTAIS (−0.030 with t = −2.92, −0.031 with t = −3.06, and −0.030 with t = −2.88), suggesting that the increased financial reporting quality is not due to the temporal trends in different province or industries, or the effect of the industry in combination with the specific year.

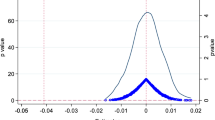

Finally, after accounting for firm-level variables, industry × year-fixed effect, and a series of factors, there may still be some unobservable factors, resulting in deviations in the estimated results. Following Ferrara et al. (2012), we conduct a placebo test that turns whether each enterprise is subject to the influence of CTAIS-3 into a completely random process, repeats the random process 5000 times, and estimates whether the coefficient of our interest follows the standard normal distribution. Figure 1 shows the distribution of 5,000 random experiments. The coefficient is close to the standard normal distribution with a mean of 0, proving that our study has controlled the influence of unobservable factors well and that the estimation result is robust.

The figure illustrates the distribution of regression coefficients obtained by replicating the regression process 5000 times, where each firm impacted by CTAIS-3 is transformed into a random event. The regression coefficient of CTAIS-3 on corporate financial restatements is estimated through this randomization process. The x-axis represents the coefficient of the random event. The y-axis on the left represents p-values ranging from 0 to 1. The y-axis on the right represents the kernel density, corresponding to the kernel density plot. All regressions include firm-level and province-level controls as defined in Supplementary Table 1, with firm and year-fixed effects included in the analysis. Figure 1 shows that the coefficient distribution is close to the standard normal distribution with a mean of 0. Source: Calculated based on data from the CSMAR database.

Conclusions

Using a panel of Chinese-listed firms from 2010 to 2019, our analysis reveals that firms reduced their financial restatement after the launch of the third praise of the China Taxation Administration Information System (CTAIS-3). Moreover, we observe a more pronounced negative association between CTAIS-3 and financial restatements when firms face higher levels of information asymmetry. Our results are robust to different measurements of financial reporting quality, varied measures, and alternative model specifications. Additional analyses suggest that the main results are significant in Non-State-Owned Enterprises and firms with higher levels of tax avoidance. Collectively, we prove that the exogenous increase in tax information leads to a lower incidence of corporate misreporting by providing a better information environment.

According to our study, the exogenous increase in tax information can serve to provide the public with additional information and mitigate the information asymmetry between companies and their investors, which contributes to studying the determinants of accounting information quality (Ahn et al., 2020; Gunn and Michas, 2018; Jayaraman and Milbourn, 2015), the growing literature examining the economic consequences of tax information (e.g., Amberger et al., 2021; Balakrishnan et al., 2019; Simone, Ege and Stomberg, 2015), the spillover effects of government behavior (Houston et al., 2019; De George, Li and Shivakumar, 2016; Chen et al., 2010) and provide insights which indicate that government behavior plays a vital role in improving corporate financial disclosure.

Our findings support that tax information is essential in reducing information asymmetry and shed light on the positive spillover effect of government activities in establishing a tax information system. We infer that policymakers and regulators can further promote the digitalization of government procedures, promoting a better information environment. Other stakeholders, such as investors, creditors, and suppliers, should incorporate the information effects of government actions into their assessment and decision-making process to better understand companies’ financial information.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Dataverse repository https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/FFESFF.

Notes

Supplementary Table 3 provides a more comprehensive review of the prior research on how tax information influences financial reporting quality.

For a comprehensive review of this topic, see the work by De George et al. (2016)

We provide specific launch dates in Supplementary Table 2.

Classification of high-tech industries formulated by the Chinese government: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/tjbz/gjtjbz/202302/P020230213402519726955.pdf

References

Abdi F, Ranaldo A (2017) A simple estimation of bid-ask spreads from daily close, high, and low prices. Rev Financ Stud 30(12):4437–4480

Aboody D, Lev B (2000) Information asymmetry, R&D, and insider gains. J Financ 55(6):2747–2766

Affleck‐Graves J, Callahan CM, Chipalkatti N (2002) Earnings predictability, information asymmetry, and market liquidity. J Account Res 40(3):561–583

Ahn J, Hoitash R, Hoitash U (2020) Auditor task-specific expertise: The case of fair value accounting. Account Rev 95(3):1–32

Akcigit U, Grigsby J, Nicholas T, Stantcheva S (2022) Taxation and innovation in the twentieth Century. Q J Econ 137(1):329–385

Amberger HJ, Markle KS, Samuel DM (2021) Repatriation taxes, internal agency conflicts, and subsidiary-level investment efficiency. Account Rev 96(4):1–25

Amel-Zadeh A, Zhang Y (2015) The economic consequences of financial restatements: Evidence from the market for corporate control. Account Rev 90(1):1–29

Amiram D, Owens E, Rozenbaum O (2016) Do information releases increase or decrease information asymmetry? New evidence from analyst forecast announcements. J Account Econ 62(1):121–138

Arif S, De George ET (2020) The dark side of low financial reporting frequency: Investors’ reliance on alternative sources of earnings news and excessive information spillovers. Account Rev 95(6):23–49

Armstrong CS, Glaeser S, Huang S, Taylor DJ (2019) The economics of managerial taxes and corporate risk-taking. Account Rev 94(1):1–24

Ashraf M, Michas PN, Russomanno D (2020) The impact of audit committee information technology expertise on the reliability and timeliness of financial reporting. Account Rev 95(5):23–56

Badertscher BA, Katz SP, Rego SO, Wilson RJ (2019) Conforming tax avoidance and capital market pressure. Account Rev 94(6):1–30

Baik B, Kang JK, Kim JM (2010) Local institutional investors, information asymmetries, and equity returns. J Financ Econ 97(1):81–106

Balakrishnan K, Blouin JL, Guay WR (2019) Tax aggressiveness and corporate transparency. Account Rev 94(1):45–69

Ball R, Shivakumar L (2006) The role of accruals in asymmetrically timely gain and loss recognition. J Account Res 44(2):207–242

Ball R, Bushman RM, Vasvari FP (2008) The debt‐contracting value of accounting information and loan syndicate structure. J Account Res 46(2):247–287

Barrios JM, Hochberg YV, Yi H (2022) Launching with a parachute: The gig economy and new business formation. J Financ Econ 144(1):22–43

Barron OE, Byard D, Kile C, Riedl EJ (2002) High‐technology intangibles and analysts’ forecasts. J Account Res 40(2):289–312

Bartov E, Bodnar GM (1996) Alternative accounting methods, information asymmetry, and liquidity: theory and evidence. Account Rev 71(3):397–418

Bartov E, Faurel L, Mohanram PS (2018) Can Twitter help predict firm-level earnings and stock returns? Account Rev 93(3):25–57

Bauckloh T, Hardeck I, Inger KK, Wittenstein P, Zwergel B (2021) Spillover effects of tax avoidance on peers’ firm value. Account Rev 96(4):51–79

Bauer AM, Fang X, Pittman JA (2021) The importance of IRS enforcement to stock price crash risk: the role of CEO power and incentives. Account Rev 96(4):81–109

Becker B, Jacob M, Jacob M (2013) Payout taxes and the allocation of investment. J Financ Econ 107(1):1–24

Bennedsen M, Zeume S (2018) Corporate tax havens and transparency. Rev Financ Stud 31(4):1221–1264

Bergstresser D, Philippon T (2006) CEO incentives and earnings management. J Financ Econ 80(3):511–529

Bertrand M, Mullainathan S (2003) Enjoying the quiet life? Corporate governance and managerial preferences. J Political Econ 111(5):1043–1075

Bird A, Karolyi SA (2016) Do institutional investors demand public disclosure? Rev Financ Stud 29(12):3245–3277

Blankespoor E, Miller GS, White HD (2014) The role of dissemination in market liquidity: evidence from firms’ use of Twitter™. Account Rev 89(1):79–112

Blankespoor E (2019) The impact of information processing costs on firm disclosure choice: evidence from the XBRL mandate. J Account Res 57(4):919–967

Bradbury D (2013) Improving the Australia’s Business Tax System. Australian Government, The Treasury. 03 Apr 2013

Brown JL, Drake KD (2014) Network ties among low-tax firms. Account Rev 89(2):483–510

Bushee BJ, Goodman TH, Sunder SV (2019) Financial reporting quality, investment horizon, and institutional investor trading strategies. Account Rev 94(3):87–112

Cahan SF, Chen C, Chen L (2024) In financial statements we trust: institutional investors’ stockholdings after restatements. Account Rev 99(2):143–168

Cao VN, Pham AV (2021) Behavioral spillover between firms with shared auditors: the monitoring role of capital market investors. J Corp Financ 68:101914

Cassar G, Ittner CD, Cavalluzzo KS (2015) Alternative information sources and information asymmetry reduction: evidence from small business debt. J Account Econ 59(2-3):242–263

Cazier R, Rego S, Tian X, Wilson R (2015) The impact of increased disclosure requirements and the standardization of accounting practices on earnings management through the reserve for income taxes. Rev Account Stud 20:436–469

Chan KH, Lin KZ, Mo PL (2010) Will a departure from tax-based accounting encourage tax noncompliance? Archival evidence from a transition economy. J Account Econ 50(1):58–73

Chan K, Chan YC (2014) Price informativeness and stock return synchronicity: Evidence from the pricing of seasoned equity offerings. J Financ Econ 114(1):36–53

Chen KC, Schoderbek MP (2000) The 1993 tax rate increase and deferred tax adjustments: a test of functional fixation. J Account Res 38(1):23–44

Chen S, Sun SY, Wu D (2010) Client importance, institutional improvements, and audit quality in China: An office and individual auditor level analysis. Account Rev 85(1):127–158

Chen PC (2016) Banks’ acquisition of private information about financial misreporting. Account Rev 91(3):835–857

Chen R, El Ghoul S, Guedhami O, Wang H, Yang Y (2022) Corporate governance and tax avoidance: evidence from US cross-listing. Account Rev 97(7):49–78

Cheng Q, Farber DB (2008) Earnings restatements, changes in CEO compensation, and firm performance. Account Rev 83(5):1217–1250

Cheng CA, Huang HH, Li Y, Lobo G (2010) Institutional monitoring through shareholder litigation. J Financ Econ 95(3):356–383

Cheng Q, Lee J, Shevlin T (2016) Internal governance and real earnings management. Account Rev 91(4):1051–1085

Chin CL, Chi HY (2009) Reducing restatements with increased industry expertise. Contemp Account Res 26(3):729–765

Chiu PC, Teoh SH, Tian F (2013) Board interlocks and earnings management contagion. Account Rev 88(3):915–944

Chung R, Firth M, Kim JB (2002) Institutional monitoring and opportunistic earnings management. J Corp Financ 8(1):29–48

Coff RW, Lee PM (2003) Insider trading as a vehicle to appropriate rent from R&D. Strateg Manag J 24(2):183–190

Coval JD, Moskowitz TJ (2001) The geography of investment: Informed trading and asset prices. J Political Econ 109(4):811–841

Crawford SS, Roulstone DT, So EC (2012) Analyst initiations of coverage and stock return synchronicity. Account Rev 87(5):1527–1553

Cull R, Xu LC (2005) Institutions, ownership, and finance: the determinants of profit reinvestment among Chinese firms. J Financ Econ 77(1):117–146

De George ET, Li X, Shivakumar L (2016) A review of the IFRS adoption literature. Rev Account Stud 21:898–1004

De Simone L, Ege MS, Stomberg B (2015) Internal control quality: The role of auditor-provided tax services. Account Rev 90(4):1469–1496

Dechow PM, Sloan RG, Sweeney AP (1995) Detecting earnings management. Account Rev 70(2):193–225

Dechow PM, Dichev ID (2002) The quality of accruals and earnings: the role of accrual estimation errors. Account Rev 77(s-1):35–59

DeHaan E, Kedia S, Koh K, Rajgopal S (2015) The revolving door and the SEC’s enforcement outcomes: Initial evidence from civil litigation. J Account Econ 60(2-3):65–96

Derrien F, Kecskés A, Mansi SA (2016) Information asymmetry, the cost of debt, and credit events: Evidence from quasi-random analyst disappearances. J Corp Financ 39:295–311

Desai H, Hogan CE, Wilkins MS (2006) The reputational penalty for aggressive accounting: earnings restatements and management turnover. Account Rev 81(1):83–112

Dhaliwal DS, Gleason CA, Mills LF (2004) Last‐chance earnings management: using the tax expense to meet analysts’ forecasts. Contemp Account Res 21(2):431–459

Dhaliwal DS, Kaplan SE, Laux RC, Weisbrod E (2013) The information content of tax expense for firms reporting losses. J Account Res 51(1):135–164

Djankov S, Ganser T, McLiesh C, Ramalho R, Shleifer A (2010) The effect of corporate taxes on investment and entrepreneurship. Am Econ J Macroecon 2(3):31–64

Du F, Tang G, Young SM (2012) Influence activities and favoritism in subjective performance evaluation: evidence from Chinese state-owned enterprises. Account Rev 87(5):1555–1588

Durnev A, Mangen C (2009) Corporate investments: learning from restatements. J Account Res 47(3):679–720

Dyck A, Zingales L (2004) Private benefits of control: an international comparison. J Financ 59(2):537–600

Dyck A, Morse A, Zingales L (2010) Who blows the whistle on corporate fraud? J Financ 65(6):2213–2253

Dyreng SD, Hanlon M, Maydew EL (2008) Long‐run corporate tax avoidance. Account Rev 83(1):61–82

Dyreng SD, Hoopes JL, Wilde JH (2016) Public pressure and corporate tax behavior. J Account Res 54(1):147–186

Dyreng SD, Hanlon M, Maydew EL (2019) When does tax avoidance result in tax uncertainty? Account Rev 94(2):179–203

Dyreng S, Hills R, Markle K (2022). Tax deficits and the income shifting of US multinationals. Available at SSRN 4007595

Eames MJ, Glover SM (2003) Earnings predictability and the direction of analysts’ earnings forecast errors. Account Rev 78(3):707–724

Edwards A, Todtenhaupt M (2020) Capital gains taxation and funding for start-ups. J Financ Econ 138(2):549–571

Efendi J, Srivastava A, Swanson EP (2007) Why do corporate managers misstate financial statements? The role of option compensation and other factors. J Financ Econ 85(3):667–708

El Ghoul S, Guedhami O, Pittman J (2011) The role of IRS monitoring in equity pricing in public firms. Contemp Account Res 28(2):643–674

Elliott WB, Grant SM, Hodge FD (2018) Negative news and investor trust: the role of $ Firm and# CEO Twitter use. J Account Res 56(5):1483–1519

Elliott WB, Fanning K, Peecher ME (2020) Do investors value higher financial reporting quality, and can expanded audit reports unlock this value? Account Rev 95(2):141–165

Erickson M, Hanlon M, Maydew EL (2004) How much will firms pay for earnings that do not exist? Evidence of taxes paid on allegedly fraudulent earnings. Account Rev 79(2):387–408

Erickson MM, Heitzman SM, Zhang XF (2013) Tax-motivated loss shifting. Account Rev 88(5):1657–1682

Feng M, Ge W, Luo S, Shevlin T (2011) Why do CFOs become involved in material accounting manipulations? J Account Econ 51(1-2):21–36

Ferrara EL, Chong A, Duryea S (2012) Soap operas and fertility: Evidence from Brazil. Am Econ J Appl Econ 4(4):1–31

Flannery MJ, Kwan SH, Nimalendran M (2004) Market evidence on the opaqueness of banking firms’ assets. J Financ Econ 71(3):419–460

Frank MM, Lynch LJ, Rego SO (2009) Tax reporting aggressiveness and its relation to aggressive financial reporting. Account Rev 84(2):467–496

Gallemore J, Maydew EL, Thornock JR (2014) The reputational costs of tax avoidance. Contemp Account Res 31(4):1103–1133

Gao P, Zhang G (2019) Accounting manipulation, peer pressure, and internal control. Account Rev 94(1):127–151

Garrett J, Hoitash R, Prawitt DF (2014) Trust and financial reporting quality. J Account Res 52(5):1087–1125

Goh BW, Lee J, Lim CY, Shevlin T (2016) The effect of corporate tax avoidance on the cost of equity. Account Rev 91(6):1647–1670

Guedhami O, Pittman J (2008) The importance of IRS monitoring to debt pricing in private firms. J Financ Econ 90(1):38–58

Gunn JL, Michas PN (2018) Auditor multinational expertise and audit quality. Account Rev 93(4):203–224

Hanlon M, Mills L, Slemrod J (2005). An empirical examination of corporate tax noncompliance. In: Taxing Corporate Income in the 21st Century. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA

Hanlon M, Heitzman S (2010) A review of tax research. J Account Econ 50(2-3):127–178

Hoopes JL, Robinson L, Slemrod J (2018) Public tax-return disclosure. J Account Econ 66(1):142–162

Hope OK, Ma MS, Thomas WB (2013) Tax avoidance and geographic earnings disclosure. J Account Econ 56(2-3):170–189

Hou Q, Li W, Teng M, Hu M (2022) Just a short-lived glory? The effect of China’s anti-corruption on the accuracy of analyst earnings forecasts. J Corp Financ 76:102279

Houston JF, Lin C, Liu S, Wei L (2019) Litigation risk and voluntary disclosure: Evidence from legal changes. Account Rev 94(5):247–272

Hribar P, Jenkins NT (2004) The effect of accounting restatements on earnings revisions and the estimated cost of capital. Rev Account Stud 9:337–356

Imbens GW, Wooldridge JM (2009) Recent developments in the econometrics of program evaluation. J Econ Lit 47(1):5–86

Ivković Z, Weisbenner S (2005) Local does as local is: information content of the geography of individual investors’ common stock investments. J Financ 60(1):267–306

Jayaraman S, Milbourn T (2015) CEO equity incentives and financial misreporting: the role of auditor expertise. Account Rev 90(1):321–350

Jiang X, Yuan Q (2018) Institutional investors’ corporate site visits and corporate innovation. J Corp Financ 48:148–168

Joshi P, Outslay E, Persson A, Shevlin T, Venkat A (2020) Does public country‐by‐country reporting deter tax avoidance and income shifting? Evidence from the European banking industry. Contemp Account Res 37(4):2357–2397

Karpoff JM, Koester A, Lee DS, Martin GS (2017) Proxies and databases in financial misconduct research. Account Rev 92(6):129–163

Kerr JN (2019) Transparency, information shocks, and tax avoidance. Contemp Account Res 36(2):1146–1183

Khan M, Watts RL (2009) Estimation and empirical properties of a firm-year measure of accounting conservatism. J Account Econ 48(2-3):132–150

Kim JB, Li L, Lu LY, Yu Y (2016) Financial statement comparability and expected crash risk. J Account Econ 61(2-3):294–312

Kotchen MJ (2021) The producer benefits of implicit fossil fuel subsidies in the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 118(14):e2011969118

Kravet T, Shevlin T (2010) Accounting restatements and information risk. Rev Account Stud 15:264–294

Krinsky I, Lee J (1996) Earnings announcements and the components of the bid‐ask spread. J Financ 51(4):1523–1535

Krishnaswami S, Subramaniam V (1999) Information asymmetry, valuation, and the corporate spin-off decision. J Financ Econ 53(1):73–112

Kumar KR, Visvanathan G (2003) The information content of the deferred tax valuation allowance. Account Rev 78(2):471–490

Lang M, Lins KV, Maffett M (2012) Transparency, liquidity, and valuation: international evidence on when transparency matters most. J Account Res 50(3):729–774

Langenmayr D, Lester R (2018) Taxation and corporate risk-taking. Account Rev 93(3):237–266

Lennox C, Lisowsky P, Pittman J (2013) Tax aggressiveness and accounting fraud. J Account Res 51(4):739–778

Lennox C, Wang ZT, Wu X (2018) Earnings management, audit adjustments, and the financing of corporate acquisitions: evidence from China. J Account Econ 65(1):21–40

Li Q, Ma MS, Shevlin T (2021a) The effect of tax avoidance crackdown on corporate innovation. J Account Econ 71(2-3):101382

Li N, Xu N, Dong R, Chan KC, Lin X (2021b) Does an anti-corruption campaign increase analyst earnings forecast optimism? J Corp Financ 68:101931

Lin Y, Mao Y, Wang Z (2018) Institutional ownership, peer pressure, and voluntary disclosures. Account Rev 93(4):283–308

Lisowsky P, Robinson L, Schmidt A (2013) Do publicly disclosed tax reserves tell us about privately disclosed tax shelter activity? J Account Res 51(3):583–629

Liu J, Wang Z, Zhu W (2021) Does privatization reform alleviate ownership discrimination? Evidence from the Split-share structure reform in China. J Corp Financ 66:101848

Ljungqvist A, Zhang L, Zuo L (2017) Sharing risk with the government: How taxes affect corporate risk-taking. J Account Res 55(3):669–707

Maydew EL (1997) Tax-induced earnings management by firms with net operating losses. J Account Res 35(1):83–96

Miller GS (2002) Earnings performance and discretionary disclosure. J Account Res 40(1):173–204

Mohd E (2005) Accounting for software development costs and information asymmetry. Account Rev 80(4):1211–1231

Monem RM (2003) Earnings management in response to the introduction of the Australian gold tax. Contemp Account Res 20(4):747–774

Mukherjee A, Singh M, Žaldokas A (2017) Do corporate taxes hinder innovation? J Financ Econ 124(1):195–221

Ohrn E (2018) The effect of corporate taxation on investment and financial policy: evidence from the DPAD. Am Econ J Econ Policy 10(2):272–301

Overesch M, Wolff H (2021) Financial transparency to the rescue: effects of public Country‐by‐Country Reporting in the European Union banking sector on tax Avoidance. Contemp Account Res 38(3):1616–1642

Palmon D, Yezegel A (2012) R&D intensity and the value of analysts’ recommendations. Contemp Account Res 29(2):621–654

Palmrose ZV, Richardson VJ, Scholz S (2004) Determinants of market reactions to restatement announcements. J Account Econ 37(1):59–89

Piotroski JD, Roulstone DT (2004) The influence of analysts, institutional investors, and insiders on the incorporation of market, industry, and firm‐specific information into stock prices. Account Rev 79(4):1119–1151

Poterba JM, Summers LH (1983) Dividend taxes, corporate investment, and ‘Q.’. J Public Econ 22(2):135–167

Pyzoha JS (2015) Why do restatements decrease in a clawback environment? An investigation into financial reporting executives’ decision-making during the restatement process. Account Rev 90(6):2515–2536

Rego SO (2003) Tax‐avoidance activities of US multinational corporations. Contemp Account Res 20(4):805–833

Roll R (1984) A simple implicit measure of the effective bid‐ask spread in an efficient market. J Financ 39(4):1127–1139

Romanov D (2006) The corporation as a tax shelter: evidence from recent Israeli tax changes. J Public Econ 90(10-11):1939–1954

Samuels D, Taylor DJ, Verrecchia RE (2021) The economics of misreporting and the role of public scrutiny. J Account Econ 71(1):101340

Srinivasan S (2005) Consequences of financial reporting failure for outside directors: Evidence from accounting restatements and audit committee members. J Account Res 43(2):291–334

Srinivasan S, Wahid AS, Yu G (2015) Admitting mistakes: home country affects the reliability of restatement reporting. Account Rev 90(3):1201–1240

Tong JY, Zhang FF (2024) Do capital markets punish managerial myopia? Evidence from myopic research and development cuts. J Financ Quant Anal 59(2):596–625

Waseem M (2018) Taxes, informality and income shifting: evidence from a recent Pakistani tax reform. J Public Econ 157:41–77

Wittenberg-Moerman R (2008) The role of information asymmetry and financial reporting quality in debt trading: evidence from the secondary loan market. J Account Econ 46(2-3):240–260

Wong TJ, Yu G, Zhang S, Zhang T (2023) Calling for transparency: evidence from a field experiment. J Account Econ 77(1):101604

Wu W, Johan SA, Rui OM (2016) Institutional investors, political connections, and the incidence of regulatory enforcement against corporate fraud. J Bus Ethics 134:709–726

Xiao C, Shao Y (2020) Information system and corporate income tax enforcement: Evidence from China. J Account Public Policy 39(6):106772

Xiong J, Ouyang C, Tong JY, Zhang FF (2021) Fraud commitment in a smaller world: Evidence from a natural experiment. J Corp Financ 70:102090

Yost BP (2023) Do tax-based proprietary costs discourage public listing? J Account Econ 75(2-3):101553

Zhang D (2019) Top management team characteristics and financial reporting quality. Account Rev 94(5):349–375

Acknowledgements

This project is partially supported by funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant 72272100, 72302154] and Shanghai International Studies University Foundation [Grant 41004878, 41004400, 11000140/042].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jian Zhang wrote the majority of the paper. Ningzhi Wang is primarily responsible for data collection and analysis. Xinyu Zhu is responsible for organizing the overall research and designing the research method and empirical plans. Yi Xiao is responsible for incorporating new empirical analysis into the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article contains no studies with human participants performed by any authors.

Informed consent

This article contains no studies with human participants performed by any authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, and provide a link to the Creative Commons license. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Wang, N., Zhu, X. et al. Does the supply of tax information affect financial restatements? Evidence from the launch of Taxation Administration Information System III in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 972 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03464-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03464-w