Abstract

We examine the prevalence of illiberal attitudes among aspiring state legislative candidates in the United States. While extensive research has questioned underlying levels of support for liberal democratic principles among the general public in the United States, we are the first to document the extent to which illiberal attitudes are present among the rising class of political leadership in the United States. We find that while the support for democratic principles is relatively high, there are substantial portions of candidates willing to encourage undemocratic behaviors in some areas. We also see some notable differences between candidates of the two major parties. Specifically, while Republicans are substantially more likely to agree that it is sometimes necessary to challenge election results when they lose, Democrats are more tolerant of restrictions—both from government and employers—on extreme viewpoints. Overall, our findings suggest that support for many democratic principles are high, but certain components of democracy may not be well sustained by those who aspire to elected office.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Following Donald J. Trump’s victory in the 2016 presidential election, academic assessments of the health of American democracy became more common (e.g. Finkel et al. 2020; Flavin and Shufeldt 2022; Ginsburg and Huq 2019; Grumbach 2022; Levitsky and Ziblatt 2018; Mettler and Lieberman 2020; Slater 2022; Waldner and Lust 2018). In this vein, a growing body of research has described illiberal attitudes and behaviors among the mass public (e.g. Arceneaux and Truex 2023; Berlinski et al. 2023; Broockman et al. 2023; Cassese 2021; Chong et al. 2022; Graham and Svolik, 2020; Kalmoe and Mason 2022; Kingzette et al. 2021; Krishnarajan 2023; Malka and Costello 2023; Martherus et al. 2021; Mernyk et al. 2022; Nichols 2021). These include, but are not limited to, hostility towards members of opposing political parties, acceptance or justification of politically motivated violence, support for limitations on civil liberties, and mistrust of electoral institutions and outcomes. This work has often found that while a majority of Americans report nominal support for democracy, this support is weaker and not as robust as many might hope (e.g., Drutman et al. 2018; Graham and Svolik 2020; Malka and Costello 2023). Moreover, assessments of the quality and value of democracy in the mass public have grown highly politicized and polarized (Carey et al. 2019; Flavin and Shufeldt 2022; Graham and Svolik 2020; Simonovits et al. 2022).

These findings are especially salient given the events surrounding Trump’s subsequent loss in the 2020 election. One goal of the violent attempt to obstruct the election certification at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021 was to convince Vice President Mike Pence and Members of Congress to overturn the election results. Presumably then, some of the attackers believed that at least some public officials shared their willingness to seek extraconstitutional remedies to their election loss. This belief might be seen as understandable in context: At that time, Trump’s efforts to overturn the 2020 election were tolerated (if not supported) by many elected officials, including Members of Congress and state legislators. These efforts included convening false slates of electors in seven states (Feuer and Benner 2023; Fischler and Shutt 2023), attempts by elected officials in several others to obstruct vote certification (Homans 2020; Miller et al. 2020; Van Voris 2020; White 2020), and a sustained pressure campaign by President Trump and allies (including some federal employees) to convince state officials to overturn the election results (Brumback 2023; Hendrickson 2023). These efforts were ultimately unsuccessful, but they serve as an important reminder that the illiberal views of public officials can pose a substantial threat to democracy—perhaps an even more significant one than violent protest.

To understand how illiberalism might shape American politics in the future, it is therefore critical to understand the degree to which these attitudes persist among not only people who hold public office, but those who aspire to do so. By examining views of candidates for these positions as opposed to limiting our inquiry to officeholders, we obtain a more complete picture of the extent to which American politicians hold views that support democratic backsliding—and the conditions under which they might emerge. The attitudes of state legislative candidates provide particular insights into the likelihood that future anti-democratic efforts will gain more traction in at least two ways. First, state legislators hold considerable power over elections in their state; if they win office, legislative candidates are likely to be on the front lines of future battles that directly shape the health (and even survival) of American democracy. Second, the state legislature is a natural stepping stone to higher office, including state executive positions and Congress. Studying state legislative candidates’ attitudes therefore provides an important window into how future efforts to erode democratic norms and institutions may unfold at all levels of American government.

Our study utilizes a large-scale survey of candidates for American state legislatures. Some existing work on other topics has surveyed state legislative candidates in general elections across some or all states (Abbe and Herrnson 2003; Broockman and Skovron 2018; Francia and Herrnson 2003, 2004; Herrnson et al. 2007; Hogan 2002; Miller 2013), but existing surveys of state legislative candidates in primary elections have generally sampled candidates in single states (Niven, 2006). In 2022, we fielded what is to our knowledge the only survey ever conducted of nearly every Democratic and Republican candidate who ran for state legislative office (including primary candidates and those who ran unopposed) in the United States during a single election cycle. The 2022 election cycle was the first opportunity for people who may have been influenced by the 2020 election to run for these offices. Our survey was designed to assess the prevalence of illiberal attitudes among these candidates and to determine what factors correlate with these views. The inclusion of primary candidates captures the full spectrum of aspiring legislators, which is critical to assessing the illiberal positions of citizens who are seeking to make policy as well as regulatory and oversight power in future elections.

Our findings show both reasons for optimism and concern. First, we find that overwhelming majorities of aspirants for state legislative office reject politically motivated violence as a means to power. Despite this, there are a small minority that are accepting of violent protest and intimidation. Moreover, our results indicate that Republican state legislative candidates are more inclined than Democrats to agree that election results should be challenged, and are also more likely to believe that some people should not vote. Relative to Republicans however, Democrats advocate greater censorship and government monitoring of political speech. These results suggest that illiberalism is not a single-party phenomenon. Moreover, our work indicates that illiberal views are not limited to candidates on the fringes of political viability. Thus, although large majorities of candidates support democratic principles, our work finds potential cracks in support of democracy among those who aspire to political leadership.

Methods

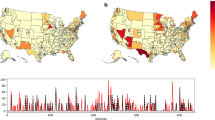

We fielded a national, online survey of state legislative candidates during the 2022 United States primary elections. We identified all candidates (including uncontested incumbents) in Democratic and Republican primaries running for seats in each state’s lower and upper legislative chambers.Footnote 1 We specifically focus on state legislative candidates because many aspects of the democratic process—including regulation and certification of local, state, and federal elections—are controlled there (Grumbach 2022). Moreover, democratic decline at the hands of public officials is most likely to happen when the public is inattentive to government actions, and most individuals have little knowledge about the actions of state government and state officials (Hogan 2008; Rogers 2017).

To implement our survey of state legislative candidates, we solicited all candidates whose email address we could obtain to participate in an online survey. Some states’ election agencies provide email addresses for registered candidates; in those cases we scraped all available email addresses from state records. More typically, states do not provide this information, and in those instances we searched campaign, party, and social media websites for candidate contact information. We obtained email addresses for 12,272 of the 13,583 candidates in the sampling frame (90.3%). Wherever possible we attempted to locate a personal email address for the candidate, as opposed to a staffer or a general information address. We also employed a screening filter intended to ensure that the survey was completed only by the candidate themselves, and not someone else affiliated with the campaign.Footnote 2

States determine the date of their primary election. In 2022, the earliest primary elections occurred in March, with subsequent primary elections held on dates through early September. Our goal was to invite candidates immediately after their state’s primary, when their electoral experience would be fresh in their minds but when their time was relatively less constrained. Given the extended nature of the primary calendar, it was therefore impractical to solicit all candidates at once. Instead, we sent initial email invitations on a rolling basis, soliciting candidates within 48 hours of the completion of their state’s primary election. We sent up to two additional solicitations to candidates who did not respond to initial invitations.

We received responses from 1,173 candidates, for an overall response rate of (9.6%). Notably, response rates for the 5,366 Democrats and 6533 Republicans were similar (9.97% and 9.06%, respectively). This overall response rate is well in line with response rates of other similar surveys of state legislative candidates, minor political officials, and other comparable political elites (e.g. Broockman and Skovron 2018; Butler and Dynes 2016; Doherty et al. 2022; Dynes et al. 2023; Hassell 2021; Miller 2013). More details are in the online supplementary materials where we provide state-by-state response rates as well as a discussion of potential non-response bias.

The survey instrument solicited information about candidates that could not be readily obtained from public records, such as demographic information and issue attitudes. We then asked candidates three question batteries that probed their support of various components of a liberal democracy (Dahl 2005): Their support of electoral democracy, their tolerance of politically motivated violence, and their views on restricting civil liberties. Full question text for these questions and the full survey instrument can be found in the supplementary material.

Results

Below, we provide descriptive results from all three of these batteries separately for Democrats and Republicans. We then provide multivariate regression analyses to determine what candidate traits and/or attitudes correlate with illiberal views among American state legislative candidates.

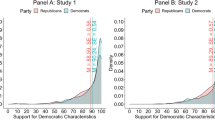

Electoral democracy

We asked candidates five questions related to the electoral process, including respecting the outcome of elections and whether or not politicians and the public should challenge the results of elections when they or their party are deemed the loser. We include these items as a measure of the potential for elected officials to embrace democratic backsliding because other work has highlighted the necessity of democracy having elected officials selected in “elections in which coercion is comparatively uncommon” (Dahl 2005, 188) Thus, the unwillingness to accept election results or the inclination to manipulate the election process represents a departure from the democratic process. Figure 1 shows these results.

A majority of candidates in both parties felt that “it is important to respect the outcome of elections, even when my party loses.” More than 90% of Democrats agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, compared to 73% of Republicans. Similarly, about 12% of Republicans disagreed or strongly disagreed with that statement—a rate more than twice that of Democrats. On balance however, while we see clear differences between how Democrats and Republicans engaged with that statement, the results from that question show relatively high levels of support for respecting election outcomes across parties.

Further questions on respect for electoral outcomes show that there is, perhaps, less firm support for respecting traditional democratic norms among American candidates than we might hope. This is true among candidates of both parties, but is especially so among Republicans. For instance, 27% of Democrats indicate that they agree to some extent that politicians have a “responsibility to challenge election results when they lose.” When factoring the 31% of Republicans who neither agreed nor disagreed with this statement, only a minority (43%) of Republican candidates disagreed with this statement. Extrapolating from our sampling frame, this implies that more than 2,000 candidates who ran for state legislative office in 2022 agree that election results should be challenged when their party loses.

We see similar results for the question about whether “the people should challenge election results even if the official certification deems their party the loser.” Note that this question shifts the focus of election challenges from politicians to the people. While only 5% of Democrats agreed with the statement, 27% of Republicans did. As before, we also see a much higher rate of Republicans on the fence: 29% of Republicans neither agreed nor disagreed with the premise of the people challenging election results, compared to only 9% of Democrats. As with the idea of politicians challenging results, a minority of Republicans 44% disagreed that the people should object to election outcomes, even when results are certified. As before, these results equate to thousands of candidates in the United States who felt that election results should be challenged even if the official certification determines their party’s candidate to have lost.

We also included questions in this battery that asked about changing electoral rules and suffrage, given the recent wave of laws put forward by state legislators altering the rules governing ballot access and voting procedures (Grumbach, 2022). When it comes to their views on whether their party should change election rules to help itself in the future, we see that the response pattern among Democratic candidates largely mirrors that of Republicans. Majorities from both parties (65%) disagreed or strongly disagreed with the notion of changing election rules. However, in both parties, sizeable minorities (around 35% for both Democrats and Republicans) were either noncommittal or were open to the possibility of changing electoral rules to benefit their parties’ future electoral prospects.

When thinking about whether the country would be better off if certain people did not vote (potentially as a result of changes to electoral procedures, but also more generally), we see significant differences across the parties. While 79% of Democrats disagreed with this statement, only a slim majority of Republicans (55%) did. And, while only 7% of Democrats agreed or strongly agreed that the country would be better off if some people failed to turn out, a quarter of Republicans (26%) felt this way.

Overall, our results indicate that a sizable minority of candidates are willing to set aside the basic norms of electoral democracy if they lose. Moreover, these results also provide evidence of clear partisan differences. Republican candidates are much more likely than Democrats to feel that challenging election results is acceptable, and that certain people should not vote. Thus, our results suggest that Democrats in our sample were more supportive of electoral norms (such as accepting election results) than Republicans in the 2022 election.

Political violence

We also asked questions about the willingness of state legislative candidate to embrace Political Violence as another way of testing democratic backsliding and the respect for the democratic process (Dahl 2005). The responses from the Political Violence Battery, as shown in Fig. 2, indicate that solid majorities of candidates in both parties reject political violence, particularly when described as part of the partisan political process. For instance, more than 90% of candidates from both parties strongly disagreed that “it is sometimes justified for my party to use violence in advancing their political goals.” This sentiment was similarly strong when candidates were asked specifically about the outcome of the 2022 elections.

We see slightly fewer candidates strongly disagreeing that it is acceptable to send threatening or intimidating messages to the other party’s leaders (82% for Democrats and 81% for Republicans). However, when combining the candidates who merely disagree (as opposed to strongly disagreeing), 94% of Democratic candidates and 89% of Republican candidates disagree with this action as well.

The clear outlier is the statement, “If elected leaders will not protect America, the people must do it themselves, even if it requires taking violent actions.” Here, 87% of Democrats either strongly disagree (77%) or disagree (10%). Just 6% of Democrats agree or strongly agree, while 7% are undecided. In contrast, nearly one-fifth of Republicans (19%) either strongly agree or agree, and the same percentage are undecided. Just 62% of Republicans disagree with the premise of people taking violent action to “protect America.” Republicans therefore appear to be more likely to believe that violence is an acceptable means of mass political action if they feel the country is threatened.

Civil liberties

Finally, we consider how candidates view restrictions on civil liberties such as free speech, freedom of the press, and the freedom to assemble. These components are also critical components of a democratic society. As Dahl (2005, 189) notes, the right of citizens to “express themselves...on political matters broadly defined,” and the right of citizens to “associational autonomy” are core democratic institutions. Thus the rejection of these institutions represent a willingness to embrace democratic backsliding. The results of our Civil Liberties Battery are depicted in Fig. 3. In these questions we find Democratic candidates more willing to endorse punishment for political speech and government monitoring of political views. While majorities in both parties disagree that “companies should fire employees who post the other party’s extreme views on social media,” there is more support for this course of action among Democratic candidates than Republicans: 54% of Democratic candidates disagreed to some extent with this statement, compared to 76% of Republicans.

The other question where we find substantial partisan differences is whether the “government should monitor people who post the other party’s extreme views online.” Here, 39% of Democrats agreed with this statement while only 10% of Republicans did. Likewise, nearly three times as many Republicans strongly disagreed with this statement as did Democratic candidates.

On the other hand, a large majority of Republican state legislative candidates either agreed or strongly agreed that “there are too many extreme speakers of the other party invited to speak on college campuses today” while only 27% of Democrats agreed with this statement. However, 51% of Democrats and 23% of Republicans neither agree nor disagree with this statement, indicating a large amount of ambivalence in both parties.

In the remaining two questions we see a quite a low willingness among candidates in both parties to limit political speech in newspapers, even when it favors a candidate’s opponents or is critical of their own side.

Regression analyses

In this section, we consider whether or not certain attributes and attitudes are associated with more illiberal beliefs among state legislative candidates. To do so, we compile a dataset of additional covariates for each candidate who responded to our survey. Our intent is to test whether these additional factors are associated with beliefs about liberal democracy. These covariates fall into one of three categories:

-

Demographic Factors: We measure the gender, race, education, age, and religious affiliation of each candidate. In studies of the public, many of these demographic factors have been shown to be associated with views of democracy and political violence (Kalmoe and Mason 2022).

-

Electoral Factors: These variables measure different aspects of a candidate’s electoral experience and are intended to capture the degree to which the experience that a candidate has running for office might impact their views of the democratic process more generally. A candidate who loses, for example, might come away from the experience with a more negative view of elections and democracy more generally than a candidate who won the primary election. We also measure the distance between the candidate’s primary vote share and the vote threshold necessary to advance from the primary to the general election (distance to advancement). Positive values indicate electoral performance beyond the necessary vote threshold while negative numbers indicate the gap in vote share needed to advance to the general election. We also include the party of the legislator and measure whether or not the candidate ran as the incumbent in the primary election.

-

Candidate Quality: To capture features of candidate experience and quality we include variables measuring whether the candidate has prior electoral experience (that is, they have been previously elected to some public office), and the share of the total donations raised by the candidate in the primary election. These variables are intended to identify whether the illiberal attitudes we study are held only among fringe candidates or are common among all candidates, regardless of experience or electoral viability.

We include each of these factors as independent variables in a series of regression models. The dependent variables in these models are additive scales from each of the question batteries discussed above. In each case we sum each respondent’s answers to questions in each battery with higher values indicating more illiberal views and lower values indicating more liberal views. We then rescale the indices to run from 0 to 1 and use them as the dependent variables in three linear regression models. The results of those models are displayed in Table 1 below. Additional models with state-level fixed effects and models testing differences among competitive states that are more likely to be pivotal in the 2024 presidential election appear in the supplemental materials.

We begin by considering those variables that have a consistent relationship with illiberal attitudes across the three different models. First, consistent with recent work that had found education to be an important determinant of political views and behavior (Barber and Pope 2023; Igielnik et al. 2021; Pew Research Center 2018), in all three regression models, individuals with more education are less likely to espouse illiberal attitudes. We also find a strong relationship between illiberal attitudes and partisanship in each of the three indices of illiberal attitudes. However, the direction of that association is different depending on the index we consider. In the indices measuring views of electoral democracy and political violence, Republicans are more likely to hold illiberal attitudes than Democrats. The magnitude of the coefficient in the model measuring views of electoral democracy is especially large (0.125, p < 0.01), given that the dependent variable runs between 0 and 1, and the R2 of that model is also much higher than in the other regressions. In fact, a model in which the electoral democracy dependent variable is regressed on only a partisanship dummy variables has an R2 of 0.21. It is noteworthy that this index is composed of questions regarding challenging election results, changing electoral rules, respecting the outcome of elections and access to the franchise — things all heavily emphasized by Donald Trump in the months surrounding the 2020 election.

In the final regression model, which examines candidates’ views on restricting and monitoring political speech, Republicans are less likely to espouse illiberal views than Democrats. This reversal of the sign of the coefficients (compared to the first and second models in Table 1) is noteworthy as these models measure attitudes regarding government censoring of speech, monitoring of individuals’ online activity, and punishment for politically extreme views.

Turning now to the rest of the variables included in the model, we consider those factors that are not associated with illiberal views. Among the demographic variables, we do not find any consistent relationship for gender, race, age, or religiosity—though we do find that men are more willing to restrict civil liberties than women, all else equal. Looking at electoral factors, we do not find a relationship between illiberal attitudes and winning the primary election (i.e. there is no “sore loser” effect), or how close a candidate came to winning the primary election. Incumbency and financial factors are not strongly associated with candidate attitudes, either. Prior elected experience is only related to being less likely to endorse political violence, but it is not correlated with support for electoral democracy or free speech. Overall, our results do not provide evidence that illiberal views are merely viewpoints held by candidates on the political fringes. The lack of a significant relationship between these measures of candidate viability and holding illiberal views suggests instead that illiberal attitudes are spread throughout all types of candidates, both long-shot candidates and those more likely to win.

Discussion

Overall, our survey paints a concerning picture with regards to the democratic attitudes of candidates for office. On the one hand, an overwhelming share of both parties reject politically motivated violence—though it is of course concerning that even small minorities of both parties are accepting of violent protest and threats of intimidation.

On the other hand, our results reveal that along with candidates’ education level, party is a consistent predictor of the extent to which they harbor illiberal views. Republicans are more willing to agree that election results should be contested by losing candidates or by the public, and are also more likely to agree that certain people should not vote. Given these patterns, it comes as no surprise that when we regress the Electoral Democracy index on party, we find large effects: Republicans hold decidedly more illiberal views than Democrats when it comes to the conduct of elections. Though the relationship is less strong when we examine willingness to engage in political violence, we see that Republicans are more illiberal in that area as well.

Republicans do not hold a monopoly on illiberal views, however. We find that Democrats are less supportive of unrestricted civil liberties. We therefore see unsettling signs among candidates of both parties for the continued health of liberal democracy in America.

While our survey reveals that candidates of both parties show some illiberal tendencies, we find it especially concerning that a large share of Republican state legislative candidates express support for the types of actions that occurred in President Trump’s efforts to subvert the outcome of the 2020 election, and that these candidates appear ready to support similar behaviors in 2024.Footnote 3 Our results shed new light on the threats to democratic norms from within the political system, and show that while there is room for optimism in the beliefs of candidates for elected office, there are also areas of troubling disregard for the enduring success of democracy in America.

Data availability

Upon publication of this article, all data used in the article and code used to produce all results will be made freely and publicly available through the Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JCM7OC.

Notes

The obvious exception is Nebraska, which has a unicameral, non-partisan legislature. In Nebraska, we emailed all candidates that had qualified for the primary ballot regardless of party. Respondents were asked their partisan identity in order to identify co-partisans and out-party partisans for the purposes of the survey questions.

Unsurprisingly, given the low profile nature of most state legislative campaign, only 25 total responses were filtered out because they were initially responded to by an individual who was not the candidate. Two of these campaigns reached out to have the survey resent to be completed by the candidate.

As of the writing of this paper, Donald Trump appears to be the clear favorite to be the Republican presidential nominee in 2024.

References

Abbe OG, Herrnson PS (2003) Campaign professionalism in state legislative elections. State Politics Policy Q 3(3):223–245

Arceneaux K, Truex R (2023) Donald trump and the lie. Perspect Politics 21(3):863–879

Barber M, Pope JC (2023) The Crucial Role of Race in 21st Century U.S. Political Realignment. Public Opinion Quarterly, forthcoming

Berlinski N, Doyle M, Guess AM, Levy G, Lyons B, Montgomery JM (2023) The effects of unsubstantiated claims of voter fraud on confidence in elections. J Exp Political Sci 10(1):34–49

Broockman DE, Skovron C (2018) Bias in perceptions of public opinion among American political elites. Am J Political Sci 112(3):542–563

Broockman DE, Kalla JL, Westwood SJ (2023) Does affective polarization undermine democratic norms or accountability? maybe not. Am J Political Sci 67(3):808–828

Brumback K (2023) Giuliani turns himself in on Georgia 2020 election charges after bond is set at $150,000. The Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/trump-giuliani-georgia-election-indictment-fulton-county203b1e69cbff227a0bf8cc59a6bb645f

Butler DM, Dynes AM (2016) How politicians discount the opinions of constituents with whom they disagree. Am J Political Sci 60(4):975–989

Carey JM, Helmke G, Nyhan B, Sanders M, Stokes S (2019) Searching for bright lines in the trump presidency. Perspectives on Politics 17(3):699–718

Cassese EC (2021) Partisan dehumanization in American politics. Political Behav 43:29–50

Chong D, Citrin J, Levy M (2022) The realignment of political tolerance in the United States. Perspect Politics 1–22

Dahl RA (2005) What political institutions does large-scale democracy require? Political Sci Q 120(2):187–197

Doherty D, Dowling CM, Miller MG (2022) Small power: how local parties shape elections. Oxford University Press, New York

Drutman L, Diamond L, Goldman J (2018) Follow the leader: exploring American support for democracy and authoritarianism. Democracy Fund Voter Study Group. https://www.voterstudygroup.org/publication/follow-the-leader

Dynes AM, Hassell HJ, Miles MR (2023) Personality traits and approaches to political representation and responsiveness: an experiment in local government. Political Behav 45:1791–1811

Feuer A, Benner K (2023) The fake electors scheme, explained. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/27/us/politics/fake-electors-explained-trump-jan6.html

Finkel EJ, Bail CA, Cikara M, Ditto PH, Iyengar S, Klar S (2020) Political sectarianism in America. Science 370(6516):533–536

Fischler J, Shutt J (2023) How the fake electors in seven states are central to the trump Jan. 6 indictment. AZ Mirror. https://www.azmirror.com/2023/08/03/how-the-fake-electors-in-seven-states-are-centralto-the-trump-jan-6-indictment/

Flavin P, Shufeldt G (2022) Citizens’ perceptions of the quality of democracy in the American states. Meetings of the American Political Science Association. https://cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/blogs.baylor.edu/dist/2/1297/files/2022/08/Flavin_Shufeldt_APSA_2022.pdf

Francia PL, Herrnson PS (2003) The impact of public finance laws on fundraising in state legislative elections. Am Politics Res 31(5):520–539

Francia PL, Herrnson PS (2004) The synergistic effect of campaign effort and election reform on voter turnout in state legislative elections. State Politics Policy Q 4(1):74–93

Ginsburg T, Huq A (2019) How to save a constitutional democracy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Graham MH, Svolik MW (2020) Democracy in America? Partisanship, polarization, and the robustness of support for democracy in the United States. Am Political Sci Rev 114(2):392–409

Grumbach JM (2022) Laboratories against democracy. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Hassell HJ (2021) Desperate times call for desperate measures: electoral competitiveness, poll position, and campaign negativity. Political Behav. 43:1137–1159

Hendrickson C (2023) Michigan commission: discipline ’kraken’ lawyers for lawsuit to overturn 2020 election. Detroit Free Press. https://www.freep.com/story/news/politics/2023/05/05/sidney-powell-kraken-lawyerstrump-election-michigan-complaint/70187859007/

Herrnson PS, Stokes-Brown AK, Hindman M (2007) Campaign politics and the digital divide: Constituency characteristics, strategic considerations, and candidate internet use in state legislative elections. Political Res Q 60(1):31–42

Hogan RE (2002) Candidate perceptions of political party campaign activity in state legislative elections. State Politics Policy Q 2(1):66–85

Hogan RE (2008) Policy Responsiveness and Incumbent Reelection in State Legislatures. Am J Political Sci 52(4):858–873

Homans CG (2020) o.p.-controlled county in Arizona holds up election results. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/28/us/politics/arizona-county-election-resultscochise.html

Igielnik R, Keeter S, Hartig H (2021) Behind Biden’s 2020 victory. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2021/06/30/behind-bidens-2020-victory/

Kalmoe NP, Mason L (2022) Radical American partisanship: mapping violent hostility, its causes, and the consequences for democracy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Kingzette J, Druckman JN, Klar S, Krupnikov Y, Levendusky M, Ryan JB (2021) How effective polarization undermines support for democratic norms. Public Opin Q 85(2):663–677

Krishnarajan S (2023) Rationalizing democracy: the perceptual bias and (un)democratic behavior. Am Political Sci Rev 117(2):474–496

Levitsky S, Ziblatt D (2018) How democracies die. Crown, New York

Malka A, Costello TH (2023) Professed democracy support and openness to politically congenial authoritarian actions within the American public. Am Politics Res 51(3):327–342

Martherus JL, Martinez AG, Piff PK, Theodoridis AG (2021) Party animals? extreme partisan polarization and dehumanization. Political Behav 43:517–540

Mernyk JS, Pink SL, Druckman JN, Willer R (2022) Correcting inaccurate metaperceptions reduces americans’ support for partisan violence. Proc Natl Acad Sci 119(16):e2116851119

Mettler S, Lieberman R (2020) Four threats. St. Martin’s Press, New York

Miller MG (2013) Subsidizing democracy: how public funding changes elections and how it can work in the future. Cornell University Press

Miller Z, Cassidy CA, Long C (2020) Trump targets certification process to block biden: What is it? The Christian Science Monitor. https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Politics/2020/1119/Trump-targets-certificationprocess-to-block-Biden-What-is-it

Nichols T (2021) Our own worst enemy: the assault from within on modern democracy. Oxford University Press, New York

Niven D (2006) Throwing your hat out of the ring: Negative recruitment and the gender imbalance in state legislative candidacy. Politics Gender 2(4):473–489

Pew Research Center (2018) Pew Research Center for most trump voters, ‘very warm’ feelings for him endured. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2018/08/09/an-examination-of-the-2016-electoratebased-on-validated-voters/

Rogers S (2017) Electoral accountability for state legislative roll calls and ideological representation. Am Political Sci Rev 111(3):555–571

Simonovits G, McCoy J, Littvay L (2022) Democratic hypocrisy and out-group threat: explaining citizen support for democratic erosion. J Politics 84(3):1806–1811

Slater D (2022) Threats or gains: the battle over participation in america’s careening democracy. Ann Am Acad Political Soc Sci 699:90–100

Van Voris B (2020) Pennsylvania Republicans seek to block vote certification. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-11-23/pennsylvania-republicans-seekorder-blocking-vote-certificationxj4y7vzkg

Waldner D, Lust E (2018) Unwelcome change: coming to terms with democratic backsliding. Annu Rev Political Sci 21:93–113

White E (2020) Michigan gop backtracks after blocking vote certification. The Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/election-2020-joe-biden-donald-trump-local-electionsmichigan-64c18e12e0d409d9629871cda3c07293

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Riley Callahan, Nicki Camberg, Madeline Breeden, and Emma Sherman-Hawver for their research assistance. This research was approved by the IRB at Barnard College, Columbia University (Approval Number 2021-1120-055).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to all parts of the research, including the design of the survey instrument, collection of data, analysis of data, and the writing of the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This research was approved by the IRB at Barnard College, Columbia University (Approval Number 2021-1120-055). All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations as outlined in the IRB application and in accordance with the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) Code of Professional Ethics and Practices.

Informed consent

All survey subjects were asked their informed consent before any data collection took place. Prior to answering any questions, respondents were presented with the following information: Informed Consent You are being asked to participate in a national study of state legislative candidates. This survey is part of a research study conducted by researchers at Barnard College, Brigham Young University, and Florida State University. We are non-partisan researchers conducting a study of both parties’ candidates, funded exclusively by our non-profit institutions. We will not use our results for political purposes. The goal of this survey is to learn more about American political campaigns, candidates, and elections, but we will not ask you to discuss proprietary information or tactics. We will ask you some questions about yourself, your views on issues of the day, and why you decided to run for office. We know your time is valuable. To help compensate you for your participation, we are offering a benefit to survey participants in the form of a summary report containing some findings of this survey, to be emailed to you (if you so choose) after we have completed the study. This document will allow you to gain a sense of aggregate demographics and opinions among Democratic and Republican state legislative candidates. There are no known risks associated with this study beyond those associated with everyday life. Your participation in this online survey involves risks similar to a person’s everyday use of the Internet, and there are no known risks associated with this study beyond those associated with everyday life in your capacity as a candidate. We hope that our results will add to the knowledge about how American elections are conducted. Findings from this study may be reported in scholarly journals, at academic seminars, and at research association meetings. The data will be stored at a secured location and retained indefinitely. Confidentiality will be maintained to the degree permitted by the technology used. No identifying information about you will be made public and any views you express will be kept completely confidential. Your participation is voluntary. Even if you decide to participate, you are free not to answer any question or to withdraw from participation at any time without penalty. If you have any questions about the research, you can contact Professor Michael G. Miller at mgmiller@barnard.edu. This study has been approved by Barnard College’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). If you have any questions about your rights as a research participant or concerns about the conduct of this study, you may contact the Barnard College IRB chairs at irb@barnard.edu. () I understand the risks of this study as described above. I understand that I may opt into receiving a summary of some of the study’s findings, and that I may also opt into a raffle for an iPad Mini, but that winning that raffle is not guaranteed. I understand that my participation is voluntary and I may withdraw at any time. I agree to participate. () I do not agree to participate.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barber, M., Hassell, H.J.G. & Miller, M.G. Illiberal attitudes among US state legislative candidates. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1036 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03529-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03529-w