Abstract

Life education is increasingly recognized as one of the potentially effective ways to reduce unnatural deaths. Existing research focuses mainly on classroom knowledge transfer and extracurricular practical activities, which has been criticized for their effectiveness due to insufficient interaction between teachers and students. Creating high-quality life education, therefore, has become a demand for human happiness. Intergenerational learning embedded in life education, developed by collaborating with primary schools and older adult schools in China, has become an effective practice. Two teachers, seven primary school students, and seven older adult learners were interviewed to reveal the characteristics and impact of this effective practice. This model of practice establishes a dual subject of teachers and students in breaking the boundary between teachers as subjects and students as objects, while recognizing diverse lives in the interaction and reflection of intergenerational learning. In addition, this study constructs a classroom teaching model of teachers, primary school students, and older adult learners jointly creating knowledge, skills, emotions, attitudes, and values, and I put forward the life education thought of ‘seeing life through life’. This study has implications for policymakers on improving educational policies and practitioners on innovating life education models in cross-cultural contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

From ancient times to the present, philosophers, educators, and sociologists have regarded life as the original intention and destination of theoretical construction and practical exploration (Sirgy & Wu, 2009). Among them, what is life, where life comes from, and how to improve the value of life have become important topics that researchers continue to discuss (Binmore, 2016; Grimm & Cohoe, 2021). There is a consensus that understanding, revering, and cherishing life should be everyone’s attitude and behavior (Lindseth & Norberg, 2022; Wright, Breier, Depner, Grant, & Lodi-Smith, 2018). If we understand death in terms of whether it is normal or not, the types of death can be categorized into normal aging death and unnatural death (Pilling, 1967). Normal death, such as disease and aging, has inevitable and irresistible characteristics. Increasing medical input and maintaining a positive attitude have become important methods to deal with normal death. Although normal death brings serious physical and mental harm to relatives and friends, human beings often choose to accept it calmly (Clements, DeRanieri, Vigil, & Benasutti, 2004). However, many unnatural deaths, such as car accidents caused by drunk driving and suicides caused by depression, often bring negative effects of individual trauma, family breakdown, and social instability that are difficult to eliminate in the short term (Carr et al., 2017; Testoni, Russotto, Zamperini, & Leo, 2018).

Many studies have shown that most unnatural deaths are characterized by human intervention, which may be prevented by effective methods (Longo et al., 2015; Truby, Brown, Dahdal, & Ibrahim, 2022; Zalla et al., 2023). To minimize the frequency of unnatural deaths, many countries have tried to develop and innovate effective ways to help people revere and cherish life. For example, life teaching materials in China (Ji & Reiss, 2022), school and community life training in Japan (Takamura et al., 2017), and life care for vulnerable groups in countries such as Italy (Corti et al., 2023) profoundly highlight particular practices in improving the quality of life in different countries. In addition, many studies have shown that life education has important value for normal death and abnormal death, and has become one of the effective methods to prolong physical life, enrich spiritual life, and empower social life (Besley & Peters, 2020; Nan et al., 2020; Ronconi, Biancalani, Medesi, Orkibi, & Testoni, 2023).

Globally, the current theoretical research and practical reform in life education are constantly being explored and advanced. The hypothesis of these studies follows the logic that education can achieve the purpose of revering and cherishing life (Mirowsky & Ross, 1998; Schuller, Preston, Hammond, Brassett-Grundy, & Bynner, 2004). Or rather, how to live a valuable life and enhance the meaning of life can be taught in the form of knowledge and skills. On the whole, many countries implement life education in their education systems, such as primary and secondary schools, universities, community schools, vocational schools, and older adult schools (Bolkan, Srinivasan, Dewar, & Schubel, 2015; Raccichini et al., 2023; Ryoo, 2016). From most recent theoretical research and practical exploration, teachers teach students rich knowledge of what life is, and how to cherish life inside and outside the classroom, which becomes the most important way to carry out life education in the school system (Rodríguez Herrero, de la Herrán Gascón, Pérez-Bonet, & Sánchez-Huete, 2022). It can be said that these diversified life education courses and activities have played an important role in improving the awareness and ability of the educated to understand, revere, and cherish life.

However, some studies show that life education is somehow conditional and limited, and many people who have participated in life education courses and activities are involved in abnormal deaths every year (Kim, Choi, Lee, & Shin, 2005; Wass, 2004). The main reason why life education is inefficient lies in the lack of experience and interaction in the classroom teaching mode in which teachers teach students life knowledge and skills (Akyildiz, Altun, & Kasim, 2018). On the surface, students seem to acquire a lot of knowledge and skills about life in this kind of classroom teaching of life education. This knowledge-teaching and skill-enhancing education divorced from life, however, can hardly effectively enable students to fully understand the essence of life and experience its preciousness (Albe, 2008; Hilton & Pellegrino, 2012). It can even be said that the life education model taught by teachers and learned by students tends to highlight life knowledge and skills, and it is difficult to see living students with life growth and development. Therefore, in the current society full of risks and uncertainties, many countries have called for exploring new methods of life education, which has become an important issue with a sense of the times that theoretical researchers and practical reformers have to face (Kang et al., 2010).

As one of the countries with the largest number of students enrolled in schools, China attaches great importance to the physical and mental health of students at all levels and types of schools. Since the reform and opening up, especially in the 21st century, China has issued a range of laws and policies on life education for all ages. For example, on October 17, 2020, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress of China adopted the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Minors, which clearly states that schools should provide life guidance, mental health counseling, adolescent education, and life education according to the physical and mental development characteristics of minor students (Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, 2020). On February 21, 2022, the State Council issued the Notice on Printing and Distributing the ‘14th Five-Year Plan’ National Planning for the Development of the Cause for the Aged and the Service System for the Aged, clearly proposing to strengthen life education for the public (State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 2022). From these laws and policies, it can be seen that China attaches great importance to life education to help citizens live a more valuable life. Therefore, to improve the awareness and behavior of different age groups in perceiving, revering, and cherishing life, China, like most countries, incorporates life education courses and activities into the process of healthy growth of students and school brand building (State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 2010).

However, unlike the life education model in which teachers teach knowledge and skills to students inside and outside the classroom, older adults and adolescents in China have jointly created a new model of life education through intergenerational learning. Specifically, this new model aims to enable teachers to guide older adults and adolescents to see each other’s lives. Older adults and adolescents better understand, revere, and value life as they share what life is and how to live a worthwhile life (Longhutang Experimental Primary School, 2023). Unfortunately, few studies have focused on such cases. Therefore, this study aims to address the paucity of research and answer two research questions: What are the core features of life education through intergenerational learning? What are the implications of life education based on intergenerational learning for older adults and elementary school students? Opening the ‘black box’ of life education through intergenerational learning in China will not only enrich the theoretical framework and boundaries of global life education research but also help to provide practical experience of China’s life education model to other countries.

This article is structured as follows. The introduction of this study maps out life education through intergenerational learning from a global perspective. In the literature review, this study reviews the progress and shortcomings of life education and intergenerational learning, while highlighting the theoretical and practical value of this study. In the methodology section, I briefly introduced how the data were collected from teachers, older adults, and elementary school students. The findings reveal the core characteristics and effects of life education through intergenerational learning. The discussion problematizes the findings and teases out the theoretical value and practical significance of this study. Limitations and future research directions are outlined at the end of the article.

Literature review

Globally, different researchers tend to explore possible effective models of life education from a specific standpoint. On the whole, life education is a kind of educational idea and practice, which aims to cultivate individual respect, understanding, and care for life (Phan et al., 2021). The practical exploration and theoretical construction of life education can be divided into formal and informal life education, which constitute common and differentiated life education in many countries (Eshach, 2007b).

Formal life education refers to life education that takes place in the school education system and is organized and implemented by teachers according to the curriculum and teaching plans for students (Glass, 1990). The knowledge of life and how to live a meaningful life becomes the most important teaching content of this formal life education. Systematism and standardization are regarded by many researchers as the core characteristics of life education in classroom teaching mode. For example, a study on life education in Hong Kong found that drug prevention education in primary school classrooms helped increase students’ understanding of the relationship between drugs and life (Chan, 1999). For another example, several surveys of Korean college students found that formal life-and-death education helped to increase students’ knowledge of life and strengthen their perception of life (E. H. Kim & Lee, 2009; S.-N. Kim et al., 2005). In addition, a study of the impact of life-and-death education classes took place at a state university in the southeastern United States found that students who took the classes had significantly lower anxiety and fear of death while being more awed and appreciative of life than students who did not take life-and-death education classes (McClatchey & King, 2015). Many studies show that systematic, standardized, and formal life education patterns that occur in school classrooms help to change students’ understanding of life from negative to positive (Katajavuori, Virtanen, Ruohoniemi, Muukkonen, & Toom, 2019; Phan, Chen, Ngu, & Hsu, 2023; Phan et al., 2020).

On the whole, formal life education based on classroom teaching plays an important role in helping students form a positive and healthy life outlook. However, in the face of rising rates of unnatural mortality worldwide and numerous reports of negative attitudes towards life, some researchers argue that formal life education tends to inculcate knowledge of life, while neglecting the growth process of life (Phan et al., 2023; Ramos-Pla, Del Arco, & Espart, 2023). Therefore, under the background of praising and criticizing life education, seeking the balance between knowledge teaching and experience teaching has become an important direction for many researchers and practitioners to explore a new life education mode.

Along with questioning and criticizing the formal life education curriculum, informal life education activities outside the classroom began to emerge. Informal life education, as opposed to formal life education at school, is often organized and implemented in families (Peniston, 1962) and society (Eshach, 2007a; Golding, Brown, & Foley, 2009; Scribner & Cole, 1973). Compared with formal and systematic school life education curriculums, informal life education activities in an experiential way tend to enable students to perceive the existence of life and understand the value of life (Sallnow et al., 2022). Therefore, informal life education activities are distinguished from formal life education courses by non-systematic, non-standard, non-emphasis on knowledge teaching and emphasis on direct feelings and experiences. For example, a study aimed at promoting children’s understanding of life pointed out that providing an educational environment for informal learning in botanical gardens helps children perceive life changes in the process of seeing plant life (Sanders, 2007). For another example, a study has shown that informal life education courses or activities with contextualized characteristics can help improve the professionalism and responsibility of medical interns in the face of aging and death (Ratanawongsa, Teherani, & Hauer, 2005). In addition, a survey of 215 Italian high school students showed that informal life education activities were more helpful in reducing students’ anxiety about death than formal life education courses (Testoni, Palazzo, De Vincenzo, & Wieser, 2020). On the whole, life education is not only organized in the formal school education system but also implemented in hospitals, botanical gardens, and communities by informal education mode. Some studies point out that, besides the advantages of informal life education for individual growth and social progress, we still need to see that the function of informal life education has not been fully stimulated due to some possible factors such as teachers’ professional level, educational content and physical and mental development of students (Katajavuori et al., 2019; Testoni, Ronconi, et al., 2020). Other studies argue that lack of teacher-student interaction, student feedback, and communication between different age groups are the biggest shortcomings of informal life education (Stylianou & Zembylas, 2021). Therefore, interaction, communication, sharing, and reflection between the same or different groups are expected to become the direction of life education.

With the development of information technology and the aging of the population, the life gap between adolescents and older adults is generated due to differences in knowledge, skills, and thinking. Intergenerational learning, which originated in Europe and America, is characterized by mutual learning among different age groups. This mode of learning plays an important role in reducing conflicts and contradictions between adolescents and older adults in communication and interaction (Andreoletti & Howard, 2018; Watts, 2017). Current research in the field of intergenerational learning focuses on eliminating adolescents’ negative perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors about age and aging (Powers, Gray, & Garver, 2013; Tam, 2014), helping older adults cross the digital divide (Cheng, Lyu, Li, & Shiu, 2021), and establishing harmonious relationships between different age groups (Andreoletti & Howard, 2018; Keyi, Xu, Cheng, & Li, 2020). Along with the idea dissemination and practice exploration of lifelong education, lifelong learning, and learning society, intergenerational learning has evolved in today’s uncertain society. Intergenerational learning has been highlighted as a valuable theoretical and practical innovation involving formal and informal learning relationships between different age groups in life and work (Cabanillas, 2011). Although intergenerational learning is considered to cover almost all topics in interpersonal relationships, unfortunately, life education, which is closely related to everyone, has not been incorporated into intergenerational learning.

With the dissemination of the concept and practical exploration of active, successful, and productive aging (Badache, Hachem, & Mäki-Torkko, 2023; Pfaller & Schweda, 2019), how to promote the physical and mental health, social participation, and life realization of older adults has become a challenge. Promoting life values and practices through education emerges as an important solution to this challenge (Lövdén, Fratiglioni, Glymour, Lindenberger, & Tucker-Drob, 2020; Raghupathi & Raghupathi, 2020). With the continuous exploration and creation of new models of intergenerational learning and life education, intergenerational learning through life education has been created in the process of China’s modernization of characteristic socialist education. To promote the theoretical construction and practical dissemination of the life education model, this study aims to reveal intergenerational learning through life education in China. Seeking the balance between teaching knowledge and experiential learning, pursuing the classroom atmosphere of sharing, interaction, and reflection, has become an innovation of this study to unpacking life education in intergenerational learning in China.

Indeed, in contrast to the above review of studies focusing on life education for younger learners, life education for older learners has not yet attracted widespread scholarly attention and research. The small amount of literature that is highly relevant to life education for older learners focuses on two main areas. The first is to enhance the health and quality of life of older adults. These studies have shown that physiological, psychological, and social factors profoundly affect the value of life and its realization for older adults. In recent years, practitioners, represented by social workers, have aimed to enhance older people’s knowledge, understanding, and practice of life by providing them with psychological counseling services (Liu, Yang, Lou, Zhou, & Tong, 2021; Wang et al., 2020), information technology training (Chelongar & Ajami, 2021; Fischer, David, Crotty, Dierks, & Safran, 2014; Talaei-Khoei & Daniel, 2018), and opportunities and platforms for social participation (Duppen et al., 2020; Hashidate, Shimada, Fujisawa, & Yatsunami, 2021; Nivestam, Westergren, Petersson, & Haak, 2021). Second, life education for older people has begun to be mentioned indirectly rather than directly in a small number of studies on geriatric education, health education, and intergenerational learning. For example, one theoretical study argued that life education and information technology education should be included within the basic scope of education and learning for older people (Boulton-Lewis, 2010). Another study emphasized that education or learning that has a connection to life should perhaps be emphasized in intergenerational programs (Whitehouse & George, 2018). Overall, the above studies point to possible directions for understanding and exploring life education for older adults. However, how to construct an appropriate model of life education for older adults in a complex and uncertain society becomes a challenge for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers.

Methodology

Background information

Guang Ming Primary School (pseudonym), founded in 1913, is an urban primary school located in Jiangsu Province of China. As the first older adult school in Xinbei District, Xi Yang Older Adult School (pseudonym) not only provides a platform for education and learning for older adults but also adheres to the idea and action of radiating educational resources to a wider area. The ‘Intergenerational Learning Lecture Hall’ was jointly established by Guang Ming Primary School and Xi Yang Older Adult School in September 2019 as a unique educational platform for age mixing based on mutual interests. To ensure the sustainable development of this education platform, the principals of the two schools signed an agreement on intergenerational learning. By linking the two different educational institutions, this agreement empowers primary school students and older adult school students to engage in monthly learning.

So far, the ‘Intergenerational Learning Lecture Hall’ has been hosted to sustainable educational activities, such as paper-cutting, painting of intangible cultural heritage, and UNESCO’s Agenda for Sustainable Development 2030. In recent years, young children have committed suicide due to academic pressure and older adults have committed suicide due to mental depression. These events of unnatural death, which shocked and saddened the whole society, highly inspired Guang Ming Primary School and Xi Yang Older Adult School to organize and carry out a series of life education activities such as what is life and how to cherish life. After reflecting on the shortcomings of classroom teaching and practical activities in life education, teachers of the two schools decided to conduct ‘Life Education Through Intergenerational Learning’ with the help of ‘Intergenerational Learning Lecture Hall’ on May 30, 2023.

Research project

To ensure that this activity can be carried out orderly, Xiao Ming (pseudonym), principal of Guang Ming Primary School, and Ming Xin (pseudonym), principal of Xi Yang Older Adult School, decided to choose an experimental class as the practical starting point for exploring intergenerational learning empowering life education. By soliciting the willingness of primary school students and older adult students to participate in this activity, seven primary students from Class 2 of Grade 5 and seven older adult students from the painting class were finally formed into a teaching class. To improve the quality of this life education classroom teaching activity, Xiao Ming, who has rich educational wisdom, serves as the teacher. Following the physical and mental development characteristics of primary school students and older adult learners, Xiao Ming decided to use Badger’s Parting Gifts, which is a picture book on death created by British painter Susan Varley, as teaching materials for life education.

The badger is a friend who makes other animals rely on and trust, and he is always willing to help everyone. He was very old and he knew he was going to die. But the badger is not afraid of death. He thinks that death just means that he is leaving his body. He was more worried about how his friends would feel after he died. As the badger expected, his death made his loving friends sad. Time is slowly healing the sadness of the badger’s friends. When they talk about the badger later, the sadness is slowly turning into warm memories. His friends express to each other the ‘gifts’ that the badger has given them. For example, the badger taught the frog how to skate. The badger taught the fox how to wear a tie. The badger not only taught his friends skills without reservation but also taught them the value and meaning of life. It can be further expressed as being honored in life and missed in death. This picture book is a vivid story that expresses the meaning of life and how to inspire and realize the value of life. The fun, inspiration, education, and artistry have contributed to the picture book’s wider influence in the fields of philosophy and education.

On June 1, 2023, from 8:30 a.m. to 11:30 a.m., the life education through intergenerational learning was carried out as scheduled. Overall, the classroom teaching process was divided into four interlinked parts. Guiding, interacting, reflecting, and growing in teacher-student interactions were sustained throughout the teaching process. First, Xiao Ming led the elementary students and the older adults to read the picture book Badger’s Parting Gifts wholeheartedly together as the teaching content. Second, after reading and understanding the book independently word by word, Xiao Ming asked the elementary students and the older adults to share and discuss with each other the stories of life and death in Badger’s Parting Gifts in a one-to-one cooperative learning mode. Then, based on discussing and reflecting on the Badger’s Parting Gifts, Xiao Ming suggested that the primary students and the older adults turn their expression of the value of the Badger’s life further towards their views and understanding of each other’s life. Finally, Xiao Ming encouraged primary students and older adults to share their expectations and imaginations about their future lives and how to create a more meaningful life. The life education through intergenerational learning, which lasted for three hours, was brought to an end with discussions, interactions, and reflections among teachers, primary students, and older adults.

Interview method

The interview method is a common research method in the humanities and social sciences. The interview method aims to construct the mechanism of social phenomena by collecting information from the interaction between the researcher and the interviewee (Qu & Dumay, 2011). Therefore, the interview method is more suitable for exploring and discovering the complex psychological activities of human beings with a unique method in social science research (Adeoye‐Olatunde & Olenik, 2021). Further, meaning construction, process revelation, emotional empathy, cultural understanding, and exploration of the unknown become the core purposes and characteristics of the interview method (Bartlett, 2012; Powell & Brubacher, 2020). In addition to its aforementioned strengths, the more important reason for choosing the interview method in this study is that the characteristics and meanings of intergenerational learning empowerment for life education form an intrinsic connection with the interview method. Specifically, teachers, older learners, and elementary school students created a new model of life education through intergenerational learning based on complex psychology and practice. The interview method, which is characterized by exploring dynamic and complex processes (Döringer, 2021), provides unique value in understanding the characteristics and value of life education through intergenerational learning.

Stemming from shared interests and beliefs with educational practitioners, my relationship with Guang Ming Primary School and Xi Yang Older Adult School was established in June 2019. With the advice, encouragement, and support of my doctoral supervisor and me, Xiao Ming and Ming Xin established an institutionalized platform for the ‘Intergenerational Learning Lecture Hall’. A series of intergenerational learning activities such as poetry recitation, music singing, paper-cutting, and the UNESCO 2030 Strategy for Sustainable Development were planned and created. The intergenerational learning activities for life education explored in this study are the formalized activities of the ‘Intergenerational Learning Lecture Hall’. In my role as an idea transmitter and leader, I tried to stimulate the wisdom of educational practitioners and help this activity to be organized and run smoothly. It should be emphasized that to avoid the negative impact of sensitive topics such as death, this study strictly adheres to the Declaration of Helsinki’s ethics of academic research and has been strictly reviewed and approved by the academic ethics committee of a university in China. In addition, the academic ethics of respect, equality, friendliness, and sincerity were always upheld in the process of activity development and data collection.

After the activity of life education through intergenerational learning, I sent out a recruitment request to Xiao Ming, Ming Xin, seven primary students, and seven older adults who participated in the activity. All participants agreed to participate actively in the data collection. To answer the research questions raised in the introduction, a semi-structured interview method was used. The interview questions for Xiao Ming and Ming Xin are mainly about why carry out life education through intergenerational learning. The interviews for elementary students and older adults included a series of questions. For example, why would you like to participate in life education? How would you evaluate the life education you have experienced before? Did you enjoy life education through intergenerational learning? What do you think are the characteristics of life education? What new understanding of life have you gained through life education? The demographic profile of the interviewees is illustrated in Table 1.

Before conducting the formal interview, the author explained the motivation and value of the study to each interviewee in detail. To allay the psychological concerns of the interviewees, the author emphasized the research ethics that may be involved in the whole interview process, including the principles of voluntary participation, withdrawal at any time, and anonymity (Allmark et al., 2009). Considering the completeness of the recorded information, I asked if the interview could be audio-recorded and all interviewees agreed. Formal interviews were conducted from June 1 to 10, 2023. Overall, each participant was interviewed for approximately 40–60 minutes. Due to the interference and interruption of various uncertain factors, Xiao Ming, a primary school student, and two older adult learners were interviewed twice.

Data analysis

In reviewing existing literature, it is evident that life education has undergone practical explorations that generally exhibit two key characteristics. Firstly, the teacher-student relationship in life education often presents the teacher as the authority and the student as the passive recipient. Additionally, teachers tend to impart abstract knowledge about life education to students. However, these traditional features have been subject to criticism by scholars due to their static nature and lack of interaction. Recent educational theory and practical exploration emphasize classroom teaching that fosters interaction, dialogue, and reflection between both teachers and students (Hennessy, Calcagni, Leung, & Mercer, 2023; Muhonen, Pakarinen, Rasku-Puttonen, & Lerkkanen, 2024). The practical exploration of life education through intergenerational learning in this study serves as a reflection on traditional educational shortcomings while highlighting new directions for educational reform and development. Existing studies focusing on concepts such as teacher-student dialogue, and reflective teaching methods provide a theoretical basis for understanding life education’s impact through intergenerational learning. Furthermore, this study aims to address questions regarding the impact of life education through intergenerational learning, particularly its influence on enhancing values in life, understanding diverse life forms, and exploring meaningful life practices. (Chaturvedi, Vishwakarma, & Singh, 2021; Lövdén et al., 2020; Ross & Van Willigen, 1997). In exploring the potential impact of life education through intergenerational learning, axiology, epistemology, and methodology become critical viewpoints for evaluating its effects. Therefore, this study endeavors to construct the impact of life education through intergenerational learning from these three aspects.

To ensure the completeness and accuracy of the interview text, I first converted the audio-recorded interviews into Chinese text and then translated them word by word into English text with contextualization. To ensure the accuracy of the translation, the data translated into English were further validated and slightly adjusted by colleagues teaching English. Thematic coding, including deductive and inductive coding, was utilized in the data analysis (Xu & Zammit, 2020), which aimed to answer the two research questions. Top-down deductive coding was completed using the theoretical principles of teacher-student relationships, dialogic and reflective teaching methods, axiology, epistemology, and methodology. Bottom-up inductive codes were identified and categorized based on rich and sufficient interview data. The research findings are dynamically interpreted in life education practice and theory, as well as in Chinese cultural contexts.

Specifically, careful reading, refined categorization, and theoretical construction were summarized as the three necessary steps in the process of analyzing the interview data. First, all interview data texts were read in-depth, which aimed to understand and grasp the scope and meaning of the interview data as a whole. Second, the interview data were categorized and reorganized according to the conceptual frameworks of ‘teachers and students as subjects’, ‘pedagogical methods of dialogue and reflection’, and ‘axiology, epistemology, and methodology of life education’. Third, the interview data were further arranged to reflect life education through intergenerational learning. To ensure the reliability and validity of the data, two colleagues were invited by me to participate in separate coding. After careful comparisons and slight adjustments, coding reliability was ensured in consistency, which minimized subjective bias in coding (Mackieson, Shlonsky, & Connolly, 2019; Morgan, 2022). In addition, to ensure that the interview data provided by the participants were accurately understood, member check was performed to ensure validity.

Findings

Two core characteristics of life education through intergenerational learning

Establishing the relationship between teachers and students as the subject

Through the in-depth interviews conducted with two principals, seven primary school students, and seven older adult school students, it was revealed that both educators and learners alike uphold the fundamental principle of mutual respect and understanding in the realm of intergenerational learning, which underpins life education. Collectively, they devised classroom educational activities that place teachers and students on an equal footing as co-creators of the learning experience, drawing upon their collective educational insights and wisdom. This transformative teacher-student partnership transcends the traditional boundaries that often separate the teacher as the authoritative figure from the student as the passive recipient, fostering a dynamic interplay between the two. Notably, this innovative relationship has garnered immense recognition, endorsement, and accolades from both the two principals and the collective voices of the fourteen students interviewed.

As a teacher with more than 20 years of rich teaching experience, Xiao Ming has experienced the above three kinds of teacher-student relationships. Compared with the previous classroom teaching with knowledge transmission as the main mode, she thought that life education based on intergenerational learning more truly reflects the classroom teaching mode in which teachers and students are the subject. As she stated in the interview:

As a teacher for so many years, I have been exploring and reflecting on what is the ideal teacher-student relationship and classroom teaching model. Before student discussions and teacher-student interaction were often organized, but the teaching effect did not reach the expectations. However, from my initiative to guide students to actively read, dialogue, and reflect, I think this life education activity designed through intergenerational learning realizes classroom teaching in which teachers and students are the subjects. (Xiao Ming)

Ming Xin, 62 years old, has rich teaching experience like Xiao Ming. Before becoming the principal of Xi Yang Older Adult School, he was also a primary school principal. The experience of implementing life education through intergenerational learning with Xiao Ming drives him to reflect on his education work for more than 40 years. He expressed:

I thought before that the unequal amount of knowledge storage makes it difficult for teachers and students to achieve true equality in knowledge exchange. However, this life education activity made me see and firmly believe that teachers and students can be subject to each other. Such a classroom is full of vitality. I am proud and happy to be able to design and implement such courses and teaching. (Ming Xin)

The authentic embodiment of the aforementioned dual principles underscores the full realization of a reciprocal teacher-student relationship within the classroom context of life education. Concurrently, an analysis of the interview narratives from seven primary school students and seven older adult learners reveals a striking convergence with the perspectives of the two principals. All participants assert their individual identities as active subjects and collaborate seamlessly with teachers to collectively devise life education activities. To illustrate, a representative older adult learner articulates:

I have been at Xi Yang Older Adult School for two years, and have taken part in music, dance, and painting courses. These courses practice the classroom model of the teacher as subject and the student as object. I think life education classes create a new classroom model of active guidance by teachers and independent exploration by students. (Qing Xia)

In addition, a primary school student who took into account the views of other participants stated:

Although the education department requires schools to develop students’ core competencies, teachers still use indoctrination to transfer knowledge to students. Fortunately, when we take life education classes, we feel the interaction between teachers and students and the sharing and learning between us and the older adult learners. (Zhang Qiang)

The above presents the understanding of two principals and two representative students on the roles of teachers and students and their relationship with life education. They tended to perceive that the teacher-student relationship is created in life education through intergenerational learning. This judgment interrupted the existing defects about who is the subject and object between teachers and students (Wong, 2016). Through comparative thinking, on the one hand, it reveals their criticism and reflection on the previous education mode based on knowledge transmission, on the other hand, it reflects their expectation and yearning for democracy, dialogue, discussion, and reflection in classroom teaching between teachers and students as the subject.

Understanding pluralistic life in intergenerational learning interaction and reflection

Under the backdrop of modern school operational logic, which revolves around subject-based teaching and examination scores, parents and teachers often prioritize knowledge transmission over students’ holistic development after weighing the pros and cons. While some middle-income countries have made significant strides in exploring and implementing classroom instruction that is interactive and embodies the dual subjectivity of teachers and students, educational reforms aimed at fostering interaction and emphasizing life skills remain challenging in many low-income countries. Despite the difficulties in realizing interactive educational formats within subject-focused teaching, such interactions have been successfully cultivated in life education activities grounded in intergenerational learning.

The interviews with participants reveal that, on one hand, they perceive their subjectivity in life education curriculum teaching, and on the other, they profoundly experience teaching interactions and reflections that are often elusive in other classroom settings. Notably, prior studies have predominantly focused on teaching interactions and reflections between teachers and students of similar ages and stages of physical and mental development. In contrast, life education activities fostered by intergenerational learning uniquely enable interactions and reflections between teachers, primary school students, and older adult learners, spanning different ages and stages of physical and mental development. Consequently, classroom instruction that prioritizes interaction and reflection has emerged as a discursive expression for teachers and students to organize, execute, and construct these life education activities.

As a teacher, Xiao Ming expressed her understanding of life education and happiness in her eyes. This positive emotional expression can be attributed to the interactive, reflective, and life-filled education constructed by her, primary school students and older adult learners. As she stated:

I have often tried to integrate interaction and reflection into classroom teaching before, but it has not achieved the ideal educational effect. Therefore, I believe that the listening, dialogue, and reflection between primary school students and older adult learners in intergenerational learning inspired this life education activity to move towards high-quality development. (Xiao Ming)

Similar to Xiao Ming’s evaluation of why this class is of higher quality than the previous classroom teaching, Ming Xin also believes that the interaction between primary school students and older adult learners due to differences in age, psychology, and life experience has brought unexpected positive effects to this life education activity. He said:

Because of the taboo of Chinese culture to talk about life and death, the atmosphere of life and death education in Xi Yang Older Adult School was heavy and there was no communication between teachers and students. A very important reason why this life education activity is full of interaction and reflection is that the differences between primary school students and older adult learners inspire them to listen, communicate, dialogue, and reflect on each other. (Ming Xin)

In addition to the above two principals’ statements, primary school students and older adult learners articulated their reflections on participating in this course or activity with experiences and feelings. For example, Yu Xiu, a primary school student, recounted:

The previous experience of life education is extremely lacking in interaction and reflection, manifested in receiving knowledge from teachers or watching movies. This life education class is unique and interesting because it is full of dialogue and reflection. In the classroom, there are not only our primary school students and teachers but also a group of older adult learners who love learning and are very different from us. (Yu Xiu)

Similarly, Xuan Yu also suggested the ‘live and learn’ attitude and values of life. Having studied at Xi Yang Older Adult School for nearly three years, he, like other older adult learners, deeply felt that the learning experience characterized by openness, freedom, and communication was extremely vivid and unforgettable. What he said during the interview represented the common feelings of other older adult learners about this class.

As older adult learners, listening, sharing, and communicating with primary school students not only increases the teaching atmosphere and updates the teaching model, but also opens up new horizons for us to understand what life is and how to live a meaningful life. (Xuan Yu)

The interview data from the aforementioned participants illustrates how intergenerational learning propels the curriculum and instruction of life education toward high-quality development, leveraging its distinct advantages of dialogue, exploration, and reflection. This form of classroom teaching transcends the traditional static paradigm of ‘teachers teach, students learn’ and fosters a novel dynamic model in the era of lifelong learning, characterized by the interactive engagement between teachers and students, as well as the dialogic exchange between primary school students and older adult learners. Within this innovative teaching model, primary school students and older adult learners not only observe each other’s lives but also view each other as mirrors, facilitating mutual understanding and empathy. Processes such as experiencing, interacting, referencing, providing feedback, and reflecting become the cornerstone of understanding life through lived experiences. These core processes underpin the profound recognition and praise from both students and teachers towards intergenerational learning’s empowering influence on life education.

Life changing through intergenerational learning

Infinite life value: from self-development to contribution to others and society

The interview data revealed that life education through intergenerational learning raised the awareness of life among primary school students and older adult learners. Before participating in this life education activity, they paid more attention to the development of material and spiritual life, while ignoring the improvement of social life to a certain extent. However, after reading the picture book Badger’s Parting Gifts together and sharing their views on life and its value, they began to foster a strong desire to improve their material, spiritual, and social life.

Wei Min was a primary school student who came to the city with his parents from the countryside to study. He was taught by his parents to earn more money when he grew up to live a richer life. Pursuing the improvement of material life value has become an important goal of his current study and future work. However, thinking about the social life of ‘Badger’ in the picture book made him realize that the meaning of human life includes not only material life but also social life. He said:

Many of my classmates and I thought that we would live a comfortable life by earning more money when we grew up, and we didn’t realize our responsibility for social development too much. Badger’s life of helping others inspired me to be valuable to others and society. (Wei Min)

As Wei Min and other students, Xiao Hong changed his perspectives on life. In addition to emphasizing the reflection on life and its value from the dedicated life of Badger, Xiao Hong also emphasized the understanding of spiritual life and its finite and infinite values in dialogue and mutual learning with older adults. As Xiao Hong explained in the interview:

I used to have a biased image of older adults as senile, sick, and useless. By taking life education classes with them, my perception of them changed from negative to positive. Lifelong learning for older adults is the embodiment of their spiritual life to be infinitely rejuvenated. (Xiao Hong)

The aforementioned exemplary figures, Wei Min and Xiao Hong, embody primary school students’ profound comprehension of life and its inherent value, garnered through their participation in life education activities grounded in intergenerational learning. Similarly, older adults, when engaged as learners, also foster fresh perspectives on the essence of life and its worth. Post-participation in this life-enriching activity, Qiu Jin was deeply moved by the selfless assistance displayed by Badger, which sparked within her a renewed commitment to actively lend support to others in her subsequent life journey. Below are a selection of pivotal phrases extracted from her insightful interview:

The story of Badger offering help to other animals drove me to reflect on the inadequacy of my social life. Badger’s life of dedication has taught me that as I develop my material and spiritual life, I also need to further enhance my value to others and society. (Qiu Jin)

Distinct from Qiu Jin, who underscores the paramountcy of social life, Yun Long, endowed with an ardent and outgoing disposition, actively engages in a myriad of voluntary service endeavors, encompassing traffic order maintenance and community environmental cleanup. Despite his evident dedication to material and social pursuits, he, to a certain extent, overlooked the significance of enriching his spiritual life. Fortunately, the exposure to the commendable learning attitudes and lifelong learning ethos of primary school students served as a catalyst for change. Consequently, enhancing his spiritual life emerged as a pivotal takeaway from his participation in this life education initiative. As he eloquently expressed:

In the process of learning and discussing life and its value with primary school students, I felt the desire of primary school students for knowledge and imagination for the future. Different from material life, spiritual life shows one’s knowledge and sentiment, while social life emphasizes one’s help, service, and contribution to others and society. (Yun Long)

The above presents a new understanding of finite and infinite life and its goals and values by elementary school students and older adults as learners after participating in life education activities based on intergenerational learning. These new understandings confirm and enrich the material, spiritual, and social life of theoretical construction from the perspective of educators. Research has shown that while not everyone can fully realize the value of life, we can help others live meaningful lives by living meaningful lives ourselves (Scripter, 2023). It can be judged that the above-mentioned primary school students and older adult learners realize the reflection and reconstruction of their life value from the interaction process of daily life between individuals, others, and society.

Diverse life forms: respect and tolerance for the life course of different individuals

Life education rooted in intergenerational learning encompasses the diverse lifestyles of teachers, primary school students, senior learners, and Badgers alike. Xiao Hong’s aforementioned observation underscores the pivotal role that age discrimination and prejudice play in fostering generational divides and their associated tensions. A meticulous analysis of interview data reveals that subsequent to engaging in this form of life education, both primary school students and senior learners approach the myriad life forms encountered within the realms of humanity, nature, and society with heightened respect and tolerance.

Peng Yi, along with a preponderance of other primary school students and senior learners, harbors a profound affection for animals. His love for these creatures is evident in the four-legged and furry members of his household: two feline companions, a loyal canine, and a fluffy rabbit. Upon arriving home from school, his first priority without fail is to attend to their needs, feeding them with care. While Peng Yi’s admiration for animals stems from their endearing cuteness and their innate ability to provide companionship, he has yet to fully comprehend the intricate bond that constitutes the community of shared destiny between humans and animals. Fortunately, this life education program, rooted in intergenerational learning, has served as a catalyst for an evolution in his perspectives and understanding of this vital relationship. As he eloquently articulated:

I used to only know how to love animals and did not think deeply about our relationship with animals from the perspective of life. The teacher shared a series of reports on the relationship between human beings and nature issued by UNESCO, which made me realize that there is a common destiny between human beings and animals. (Peng Yi)

Different from Peng Yi’s understanding of life, Ze Hui also shared her understanding of the older adult group. Due to the imperfect information filtering mechanism, the image of the older adult is stigmatized on the Internet platform. Influenced by negative information, aging, disease, and worthlessness are Ze Hui’s stereotypes of the image of older adults. The pleasant and memorable experience of attending classes with older adults made her realize that older adults can be positive images of lifelong learners, social volunteers, and family supporters.

The internet media is irresponsible and distorts the real life of the elderly to a great extent. older adults, who joined me in class, shared their positive views of life and its value, expressing their positive identities in family, society, and learning. In this classroom full of life atmosphere, I think we need to respect, understand, and accommodate everyone’s life course. (Ze Hui)

In addition, the older adults also developed respectful and inclusive attitudes towards life after participating in life education through intergenerational learning. In contrast to Ze Hui’s fondness for animals, Liang Zhu dislikes them because he cannot tolerate their hair and smell. After reading, discussing, and reflecting on the life course and value of Badgers and other animals with elementary school students, Liang Zhu felt that animals and humans have similar life growth and emotional development. Liang Zhu experienced a change in how he dealt with animals from intolerable to respectful and tolerant.

After attending this life education class, I deeply reflected and felt guilty about my previous attitudes and feelings towards animals. In the process of discussing badger life and its value with primary school students, I feel that there is no difference between animal and human life. I will face the diversity of life with respect and tolerance attitude and emotion. (Liang Zhu)

Different from Liang Zhu’s emotional changes to animals, Xiang Ning gradually felt that there were great differences in the life course of different individuals after debating with primary school students about how to treat diversified life. Her attitude and views towards friends who had previously been difficult to get along with changed from never understanding to respect and tolerance.

Attending this life education class not only made me see more possibilities in life but also prompted me to constantly reflect on my previous attitudes and behaviors toward others. In the rest of my old age, I consider problems from the standpoint of others on the one hand and uphold the principles of respect and tolerance in interpersonal communication on the other hand. (Xiang Ning)

In November 2020, UNESCO published a report entitled Learning to Become with the World: Education for Future Survival (UNESCO, 2020). Based on the theory of common worlds pedagogies, this report challenged the traditional educational ideas and formed rooted in Western philosophy and put forward the future pedagogy of coexistence between human beings and all things. The above-mentioned life education activities through intergenerational learning, which practiced the concept of future education, provided important support for primary school students and older adults to better understand the coexistence relationship between human beings and other life in the world. At the same time, primary school students and older adult learners were renewing and constructing their own unique life experiences across ages, species, and cultures.

Authentic life practice: embracing uncertain life with positive behavior

Within the confines of this life education classroom, where intergenerational learning thrives, primary school students and senior adults converged to forge a shared insight: that the essence of human existence, as well as other forms of life, is inextricably tied to uncertainty. Through the lens of the Badger’s life journey and the intertwining of one another’s life stories, they gained profound reflections. When posed with the question of how to navigate the unpredictable tides of life, their collective response resonated with a common theme: embracing real-life experiences with positivity. This positive behavioral paradigm encompasses a proactive stance towards confronting the uncertainties that both oneself and others may encounter. While the answer may seem deceptively simple, it resonates with a profound sense of practicality and achievability. The following excerpts, culled from interviews with both primary school students and senior adults, offer glimpses into their behavioral strategies when confronted with the realities of life’s uncertainties.

One such example is Xuan Yu, a primary school student who, due to his unconventional personality, found himself with a limited circle of close friends within his class. However, observing the adult adults around him actively contemplating and planning for the future ignited a spark within him. He realized that adopting a positive mindset and taking proactive steps could potentially unlock new avenues for personal growth and fulfillment. As he eloquently put it:

To be honest, I do not particularly like my introverted personality now. From this life education class, I saw the dedicated life of the Badger and the lifelong learning of older adults. Their life experiences inspired me to take ownership of my own life and create more valuable lives with positive attitudes and behaviors. (Xuan Yu)

Similar to Xuan Yu, this life education class has also inspired Guo Qing, who adheres to lifelong learning, as she suggested:

After reading Badger’s life, I regret that I did nothing in my youth. Seeing the growth of the primary school students in class together, I feel that I need to keep my love for life and active practice in retirement to improve the value of life. (Guo Qing)

Secondly, primary school students and older adults alike demonstrate a commendable commitment to approaching the uncertainties inherent in the lives of others and the world at large with a positive and dedicated mindset. In contrast to the inward-looking approach exemplified by Xuan Yu and Guo Qing, Zhang Qiang and Qing Ling embody a philosophy that extends beyond oneself, emphasizing the importance of embracing life’s external dimensions through positive behavioral practices. Zhang Qiang, who had previously engaged in bullying his classmates, underwent a profound transformation within the confines of this life education class. He came to a profound realization of the harmfulness of his past actions and resolved to adopt a new, positive principle: to sincerely respect and care for the physical and mental well-being of others. This commitment has become the guiding force behind his interactions with his classmates, shaping his future conduct with empathy and understanding.

I was ashamed of my previous mistakes in bullying my classmates. I intend to sincerely apologize to my classmates who were bullied by me. I hope they forgive me. I will practice the concept of equality and respect in future interpersonal communication, and strive to be a person who cares and helps others. (Zhang Qiang)

Similar to Zhang Qiang, Qing Ling also embraced the uncertainty of her friends’ lives with positive attitudes. She also expanded the scope of life practice from humans to other species in the world such as animals and plants. She believed that human beings and nature should maintain a harmonious and unified relationship, and protecting animals, plants and other natural environments is to protect ourselves. She stated:

By discussing Badger’s life story with primary school students, I suddenly realized that the earth does not belong to humans alone. Human beings and animals, plants, mountains, and rivers together constitute the earth’s ecological system. For the rest of my life, I will try my best to practice the idea of symbiosis between humans and nature. (Qing Ling)

The above revealed the impact of life education through intergenerational learning on the beliefs, attitudes, and practices of primary school students and older adults in facing life. Infinite life value, diversified life forms, and authentic life practice constitute three organic aspects of this influence with their unique charm.

Discussion and conclusion

The increasing number of unnatural deaths worldwide has caused enormous physical and psychological damage to individuals, families, and societies that is difficult to reverse and repair (Carr et al., 2017; Clements et al., 2004; Testoni et al., 2018). Compared with social work services and mental health counseling, education is considered an effective way to reduce mortality and improve quality of life (Carr et al., 2017; Nan et al., 2020; Ronconi et al., 2023). Life education implemented in Guang Ming Primary School and Xi Yang Older Adult School in China was chosen as the case for this study. This study explored life education through intergenerational learning and revealed its effect on primary school students and older adults on life and its practices. This study found that establishing a double subject between teacher and student and learning in cross-age are two prominent characteristics of life education through intergenerational learning. In addition, this study further found that life education through intergenerational learning could bring positive effects in three aspects of life concept and practice. First, primary school students and older adult learners recognized the infinite life value in their transition from developing themselves to contributing to others and society. Second, they developed a respect and tolerance attitude for the life course of different individuals in the face of diverse life forms. Third, they embraced all uncertain life on earth with positive behavior in the authentic life practice.

Life education implemented in classrooms illustrated a basic pattern of ‘teachers teach’ and ‘students learn’. The greatest advantage of this classroom model is to transmit systematic and comprehensive knowledge about life to students (Akyildiz et al., 2018; Testoni, Tronca, Biancalani, Ronconi, & Calapai, 2020), which can be called ‘life education in knowledge form’. However, teachers’ indoctrination undoubtedly ignores students’ life growth and practical experience (Glass, 1990; Phan et al., 2023; Ramos-Pla et al., 2023). Therefore, pursuing the balance between objective knowledge and subjective experience became an ideal life education model. Taking life education through intergenerational learning in China as a case, this study described how teachers, primary school students, and older adult learners created classroom teaching patterns that took knowledge, skills, emotions, attitudes, and values into account. This model, which aims to make up for the deficiency of ‘life education in knowledge form’, can be called ‘comprehensive life education of seeing life through life’.

In addition to life education in the school system, informal life education practice activities outside schools such as families, communities, museums, botanical gardens, and zoos are gradually regarded as an effective way to promote life development and life quality (Peniston, 1962; Sallnow et al., 2022; Sanders & Hohenstein, 2015). However, this life education model somehow ignores teachers’ guidance, weakens teacher-student interaction, despises students’ feedback, and has no communication between different age groups (Stylianou & Zembylas, 2021; Testoni, Ronconi, et al., 2020). Life education through intergenerational learning discussed in this study effectively compensates for the above-mentioned unavoidable disadvantages in two aspects. First, life education through intergenerational learning establishes double subjects of teachers and students in interrupting the separation of subject and object, which provides fundamental preconditions for full interaction and communication between teachers and students. Second, primary school students and older adult learners with great age differences see each other’s state of life in sharing, discussing, and reflecting. The debate over what life is and how to live a more meaningful life opens up possibilities for them to recognize and understand life in its diversity.

Research on intergenerational learning rarely touches on the theme of life education, focusing mainly on age discrimination and prejudice (Powers et al., 2013; Tam, 2014), the digital divide (Cheng et al., 2021), active aging, social volunteerism, and human capital development for older adults (Andreoletti & Howard, 2018; Keyi et al., 2020). Perhaps it is because many practitioners and researchers are unaware of the possible connection between intergenerational learning and life education. Against the backdrop of gradually strengthening the connection of educational institutions in China, Guang Ming Primary School, and Xi Yang Older Adult School created life education relying on intergenerational learning based on forward ideas and practical actions. The results of this innovative educational practice show that life education through intergenerational learning helps to enhance the positive understanding and action of primary school students and older adult learners about what life is and how to live a meaningful life.

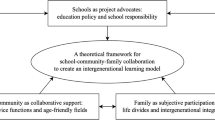

Overall, this study contributes to theory construction, policy improvement, and practice exploration in three ways. Regarding theory construction, this study establishes the connection between intergenerational learning and life education. ‘Life education through intergenerational learning’ or ‘Integrating intergenerational learning into life education’ is a possible conceptual expression of this relationship. On this basis, this study puts forward two prominent characteristics of life education through intergenerational learning, that is, establishing teacher-student double subject in breaking the separation of teacher-student subject and object and recognizing diversified life in the interaction and reflection of intergenerational learning. In addition, this study further constructs the impact of life education through intergenerational learning on the lives of primary school students and older adult learners from the infinite life value, diversified life forms, and authentic life practice. Based on the above concepts, viewpoints, and frameworks, this study attempts to formally put forward the life education thought of ‘seeing life through life’.

How to respect, honor, and value life and how to efficiently stimulate the positive value of life education have become important topics of extreme concern to policymakers. From the evidence from the interviewees, life education through intergenerational learning is considered a valuable and innovative practice. This study has two implications for policymakers. First, policymakers need to incorporate collaborative learning, dialogic education, and reflective learning into educational reform and development while recognizing the premise that teachers and students are subjects of each other. Second, policymakers need to build an education system that serves comprehensive lifelong learning with more inclusive educational thinking and action.

In addition to theoretical construction and policy implications, this study also contributes to promoting the reform and development of life education practice in China and beyond. Although the practice of life education through intergenerational learning was created in the contemporary social culture of China, its understanding of life, education, learning, and their relations has the universal law of human social development. Therefore, this study takes the life education practice of ‘seeing life through life’ in China as a sample and provides a useful reference for other countries to establish the relationship between intergenerational learning and life education, and form interactive, dialogue, and reflective classroom teaching patterns.

However, this study is not without limitations. First, this study discusses the characteristics and influence of life education through intergenerational learning, ignoring the complex influence of age, gender, education, family background, and life course for interviewees. Second, life is complex, rich, and difficult to describe. Taking Badger’s Parting Gifts as a teaching material may be insufficient in constructing the theoretical framework of life education. Third, it may be difficult to fully validate the impact of life education through intergenerational learning in a single session or activity, and perhaps more regular sessions are needed as longitudinal studies. Fourth, theoretically, the impact of life education through intergenerational learning should include both positive and negative or insufficient. However, the interviewees were satisfied with their experiences and feelings of participation. The possible shortcomings and how they can be improved are important directions for future research. In addition, future research on the relationship between intergenerational learning and life education should be carried out from a possible perspective of cross-cultural comparison. This will undoubtedly provide more diversified possibilities for understanding the complex dynamic relationships between human beings, nature, education, learning, life, and society.

Data availability

All data analyzed are contained in the paper.

References

Adeoye‐Olatunde OA, Olenik NL (2021) Research and scholarly methods: Semi‐structured interviews. J Am Coll Clin Pharm 4(10):1358–1367

Akyildiz S, Altun T, Kasim S (2018) Classroom Teacher Candidates’ comprehension levels of key concepts of the life science curriculum. J Educ Train Stud 6(9):121–131

Albe V (2008) When scientific knowledge, daily life experience, epistemological and social considerations intersect: Students’ argumentation in group discussions on a socio-scientific issue. Res Sci Educ 38(1):67–90

Allmark P, Boote J, Chambers E, Clarke A, McDonnell A, Thompson A, Tod AM (2009) Ethical issues in the use of in-depth interviews: literature review and discussion. Res Ethics 5(2):48–54

Andreoletti C, Howard JL (2018) Bridging the generation gap: Intergenerational service-learning benefits young and old. Gerontol Geriatr Educ 39(1):46–60

Badache AC, Hachem H, Mäki-Torkko E (2023) The perspectives of successful ageing among older adults aged 75+: a systematic review with a narrative synthesis of mixed studies. Ageing Soc 43(5):1203–1239

Bartlett R (2012) Modifying the diary interview method to research the lives of people with dementia. Qual Health Res 22(12):1717–1726

Besley T, Peters MA (2020) Life and death in the Anthropocene: Educating for survival amid climate and ecosystem changes and potential civilisation collapse. Educ Philos Theory 52(13):1347–1357

Binmore K (2016) Life and death. Econ Philos 32(1):75–97

Bolkan C, Srinivasan E, Dewar AR, Schubel S (2015) Learning through loss: Implementing lossography narratives in death education. Gerontol Geriatr Educ 36(2):124–143

Boulton-Lewis GM (2010) Education and learning for the elderly: Why, how, what. Educ Gerontol 36(3):213–228

Cabanillas C (2011) Intergenerational learning as an opportunity to generate new educational models. J Intergenerational Relatsh 9(2):229–231

Carr MJ, Ashcroft DM, Kontopantelis E, While D, Awenat Y, Cooper J, Webb RT (2017) Premature death among primary care patients with a history of self-harm. Ann Fam Med 15(3):246–254

Chan M (1999) LEAPing the Cultural Barrier: life education comes to China. Drugs Educ Prev Policy 6(3):327–332

Chaturvedi K, Vishwakarma DK, Singh N (2021) COVID-19 and its impact on education, social life and mental health of students: A survey. Child Youth Serv Rev 121:105866

Chelongar K, Ajami S (2021) Using active information and communication technology for elderly homecare services: A scoping review. Home Health Care Serv Q 40(1):93–104

Cheng H, Lyu K, Li J, Shiu H (2021) Bridging the digital divide for rural older adults by family intergenerational learning: A classroom case in a rural primary school in China. Int J Environ Res public health 19(1):371

Clements PT, DeRanieri JT, Vigil GJ, Benasutti KM (2004) Life after death: Grief therapy after the sudden traumatic death of a family member. Perspect Psychiatr care 40(4):149–154

Corti S, Cavagnola R, Carnevali D, Leoni M, Francesco F, Galli L, Chiodelli G (2023) The life project of people with autism and intellectual disability: investigating personal preferences and values to enhance self-determination. Psychiatr Danubina 35(3):17–23

Döringer S (2021) ‘The problem-centred expert interview’. Combining qualitative interviewing approaches for investigating implicit expert knowledge. Int J Soc Res Methodol 24(3):265–278

Duppen D, Lambotte D, Dury S, Smetcoren A-S, Pan H, De Donder L (2020) Social participation in the daily lives of frail older adults: Types of participation and influencing factors. J Gerontology: Ser B 75(9):2062–2071

Eshach H (2007a) Bridging in-school and out-of-school learning: Formal, non-formal, and informal education. J Sci Educ Technol 16:171–190

Eshach H (2007b) Bridging In-school and Out-of-school Learning: Formal, Non-Formal, and Informal Education. J Sci Educ Technol 16(2):171–190

Fischer SH, David D, Crotty BH, Dierks M, Safran C (2014) Acceptance and use of health information technology by community-dwelling elders. Int J Med Inform 83(9):624–635

Glass JC (1990) Changing death anxiety through death education in the public schools. Death Stud 14(1):31–52

Golding B, Brown M, Foley A (2009) Informal learning: A discussion around defining and researching its breadth and importance. Aust J Adult Learn 49(1):34–56

Grimm SR, Cohoe C (2021) What is philosophy as a way of life? Why philosophy as a way of life? Eur J Philos 29(1):236–251

Hashidate H, Shimada H, Fujisawa Y, Yatsunami M (2021) An overview of social participation in older adults: concepts and assessments. Phys Ther Res 24(2):85–97

Hennessy S, Calcagni E, Leung A, Mercer N (2023) An analysis of the forms of teacher-student dialogue that are most productive for learning. Lang Educ 37(2):186–211

Hilton ML Pellegrino JW (2012) Education for life and work: Developing transferable knowledge and skills in the 21st century: National Academies Press

Ji Y, Reiss MJ (2022) Cherish Lives? Progress and compromise in sexuality education textbooks produced in contemporary China. Sex Educ 22(4):496–519

Kang KA, Lee KS, Park GW, Kim YH, Jang MJ, Lee E (2010) Death recognition, meaning in life and death attitude of people who participated in the death education program. Korean J Hosp Palliat Care 13(3):169–180

Katajavuori N, Virtanen V, Ruohoniemi M, Muukkonen H, Toom A (2019) The value of academics’ formal and informal interaction in developing life science education. High Educ Res Dev 38(4):793–806

Keyi L, Xu Y, Cheng H, Li J (2020) The implementation and effectiveness of intergenerational learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from China. Int Rev Educ 66(5-6):833–855

Kim EH, Lee E (2009) Effects of a death education program on life satisfaction and attitude toward death in college students. J Korean Acad Nurs 39(1):1–9

Kim S-N, Choi S-O, Lee J-J, Shin K-I (2005) Effects of death education program on attitude to death and meaning in life among university students. Korean J Health Educ Promot 22(2):141–153

Lindseth A, Norberg A (2022) Elucidating the meaning of life world phenomena. A phenomenological hermeneutical method for researching lived experience. Scand J Caring Sci 36(3):883–890

Liu Z, Yang F, Lou Y, Zhou W, Tong F (2021) The effectiveness of reminiscence therapy on alleviating depressive symptoms in older adults: A systematic review. Front Psychol 12:709853

Longhutang Experimental Primary School (2023) Intergenerational learning makes life education more relaxed. Retrieved from https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/JYRs3mFcZxBtftHv97g0zQ

Longo VD, Antebi A, Bartke A, Barzilai N, Brown‐Borg HM, Caruso C, Gems D (2015) Interventions to slow aging in humans: are we ready? Aging cell 14(4):497–510

Lövdén M, Fratiglioni L, Glymour MM, Lindenberger U, Tucker-Drob EM (2020) Education and cognitive functioning across the life span. Psychol Sci public interest 21(1):6–41

Mackieson P, Shlonsky A, Connolly M (2019) Increasing rigor and reducing bias in qualitative research: A document analysis of parliamentary debates using applied thematic analysis. Qual Soc Work 18(6):965–980

McClatchey IS, King S (2015) The impact of death education on fear of death and death anxiety among human services students. OMEGA-J Death Dying 71(4):343–361

Mirowsky J, Ross CE (1998) Education, personal control, lifestyle and health: A human capital hypothesis. Res Aging 20(4):415–449

Morgan H (2022) Understanding thematic analysis and the debates involving its use. Qual Rep. 27(10):2079–2090

Muhonen H, Pakarinen E, Rasku-Puttonen H, Lerkkanen M-K (2024) Teacher–student relationship and students’ social competence in relation to the quality of educational dialogue. Res Pap Educ 39(2):324–347

Nan J, Pang K, Lam K, Szeto M, Sin S, So C (2020) An expressive-arts-based life-death education program for the elderly: A qualitative study. Death Stud 44(3):131–140

Nivestam A, Westergren A, Petersson P, Haak M (2021) Promote social participation among older persons by identifying physical challenges–An important aspect of preventive home visits. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 93:104316

Peniston DH (1962) The importance of “Death Education” in family life. Fam Life Coordinator 11(1):15–18

Pfaller L, Schweda M (2019) Excluded from the good life? An ethical approach to conceptions of active ageing. Soc Incl 7(3):44–53

Phan HP, Chen S-C, Ngu BH, Hsu C-S (2023) Advancing the study of life and death education: theoretical framework and research inquiries for further development. Front Psychol 14:1212223

Phan HP, Ngu BH, Chen SC, Wu L, Lin W-W, Hsu C-S (2020) Introducing the study of life and death education to support the importance of positive psychology: an integrated model of philosophical beliefs, religious faith, and spirituality. Front Psychol 11:580186

Phan HP, Ngu BH, Chen SC, Wu L, Shih J-H, Shi S-Y (2021) Life, death, and spirituality: A conceptual analysis for educational research development. Heliyon 7(5):e06971

Pilling HH (1967) Natural and unnatural deaths. Med Sci Law 7(2):59–62

Powell MB, Brubacher SP (2020) The origin, experimental basis, and application of the standard interview method: An information gathering framework. Aust Psychol 55(6):645–659