Abstract

The implementation of the noninvasive prenatal test has shown the importance of involving future care providers in healthcare innovations at an early stage. Therefore, in this explorative study in-depth interviews were performed with Dutch midwife counselors who explicitly identify as religious, to explore how they currently deal with their worldview during counseling for prenatal anomaly screening and regarding their perspectives on heritable genome editing (HGE). HGE is a potentially disruptive technology in which a pregnancy is initiated with a modified embryo or gamete, thus passing on modified genes to a future child and the following generations. Currently, a significant majority of countries prohibit HGE. However, implications for healthcare policy and practice are discussed in an ongoing scientific and societal dialogue. Eleven counselors participated: eight Christians and three Muslims. Two main themes were identified: ‘a search for role identity as a healthcare counselor’ and ‘concerns about the application of HGE’. Our findings showed that both values and underlying worldview-based beliefs influence perspectives on current and emerging reproductive techniques. Healthcare counselors search for ways to harmonize their professional role with contrasting values based on worldview-based beliefs. Moreover, for HGE, counselors fear ‘slippery slopes’ regarding the boundaries between treatment and enhancement, the severity assessment of certain conditions, and society’s appreciation for the quality of life of people with disabilities. Regarding future implementation, counselors’ medical education might benefit from a focus not only on qualification (acquiring knowledge) but also on balancing between socialization (e.g., adhering the norm of nondirective counseling) and subjectification (being a ‘self’ in relation to everything learned). In the global call for broad public and stakeholder engagement to explore the acceptability of HGE, the influence of both values and beliefs should be deliberated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The role of genetics in medicine is increasing rapidly, and its use in the reproductive context could affect future generations through heritable genome editing (HGE) (Evitt et al., 2015; Society et al., 2020). In recent years, there have been discussions and debates about the responsible implementation of genetic reproductive technologies, including ethical reflections on which genetic interventions are acceptable and how such decisions are to be made (Andorno et al., 2020; Coller, 2019; Kleiderman and Ogbogu, 2019). One genetic reproductive technique currently offered is embryo selection through preimplantation genetic testing (PGT). This allows for the selective placement of unaffected embryos to prevent the occurrence of a genetic condition (Botkin, 1998; Brezina and Kearns, 2014). Despite the obvious benefits of this technique, a large number of viable embryos are discarded because they are affected (Steffann et al., 2018). In addition, in some rare cases, all embryos will be affected, precluding PGT (Ranisch, 2020).

The discovery of the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-Associated protein (Cas)-technique, when coupled with in vitro fertilization (IVF), could potentially help more couples to conceive a genetically related child who would not be affected by a certain genetic disease, so eventually overcoming some of the limitations of PGT (Daley et al., 2019; Niemiec and Howard, 2020; O’Neill, 2020).

Following the recent evolution of terminology in the category of human gene editing, germline genome editing (GGE) - research on embryos or gametes that are not used for reproduction - is distinguished from heritable genome editing (HGE), which involves initiating a pregnancy with a modified embryo and thus passing on altered genes to a future child and subsequent generations (Baylis et al., 2020). HGE, in particular, raises not only considerations about medical safety and effectiveness, but also unanswered ethical and societal questions (Bioethics, 2018; Davies, 2019). Therefore, in a substantial majority of countries including more than 70 WHO member nations, HGE is currently prohibited (Baylis et al., 2020).

According to scientists, philosophers, and policymakers all over the world, recent scientific developments have only increased the urgency for robust public and stakeholder engagement to determine if and when HGE may be ethically permissible (Almeida and Ranisch, 2022; Bioethics, 2018; Iltis et al., 2021; Matthews and Iltis, 2019; McCaughey et al., 2019; Morrison and de Saille, 2019; National Academies of Sciences and Medicine, 2017; Ormond et al., 2017; Scheufele et al., 2021). In 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) Expert Advisory Committee on Developing Global Standards for Governance and Oversight of Human Genome Editing published a report in which relevant ethical values and principles were identified to maximize the positive impact and minimize the potential harms of human genome editing for all people (WHO, 2021). Currently, studies using GGE on human embryos are already in progress (Li et al., 2019; Ma et al., 2017; Zeng et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019).

As is known from literature from other healthcare domains, healthcare professionals’ (religious and secular) worldviews potentially impact counseling and can cause dilemmas, e.g., linked to ideals of nondirective counseling (Blythe and Curlin, 2019; Curlin et al., 2007; Curlin and Tollefsen, 2019; Van Randwijk et al., 2020; Van Randwijk, 2018). It is also known that during conversations about prenatal screening for congenital conditions, the values and beliefs of both counselors and clients/patients are rarely discussed explicitly (Prinds et al., 2020). Worldview-based values and beliefs, however, influence the way decisions are made (Gitsels-van der Wal et al., 2015; Martin et al., 2015; Prinds et al., 2020). Given the current development of preconception care which is also provided by midwives, and the development of increasing possibilities of carrier screening in the Netherlands, obstetricians and midwives, may have a role in providing information on HGE during preconception consultations (ZonMw, 2021). To the best of our knowledge, not much research has been done among midwife counselors for prenatal anomaly screening on their possibly religious, value-based perceptions of (new) reproductive technologies (e.g., HGE) and the consequences for their role as counselor. It is important to realize that having a worldview is not limited to people who are religious; atheists and agnostics have a worldview as well (Kørup et al., 2019; Shealy, 2015). Since this applies to both clients and counselors, we aim to gain a better understanding of the role worldview plays during counseling among midwife counselors. In this explorative study we focus on midwife counselors with an explicit religious conviction.

To gain more insight into midwife counselors’ perspectives on the hypothetical future clinical implementation of HGE, we also explored their views on the current use of the non-invasive prenatal test (NIPT), assuming that reflection on current counseling for prenatal screening can facilitate insight into (new) perspectives on and challenges that will come forth out of the introduction of techniques such as HGE. The overall aims of this study were to explore: (a) how religious midwife counselors for prenatal anomaly screening currently deal with their religious worldview during counseling, and (b) how midwife counselors’ values influence their perspectives on HGE, given their religious worldview.

Counseling for prenatal anomaly screening in the Netherlands

In the Netherlands, over 90% of all pregnant women engage a midwifery practice for pregnancy care, which includes an option for prenatal anomaly counseling (Perined, 2021). The organization of prenatal screening counseling is determined by the government and includes requirements for the training of counselors, including continuing education, to maintain a high quality of care (RIVM, 2023; VWS, 2013). Various professions can be engaged in counseling for prenatal anomaly screening including midwives (the vast majority), sonographers and gynecologists (Martin et al., 2022). The primary purpose of counseling is to enable pregnant women (and their partners) to make an autonomous, informed decision on whether or not to have prenatal screening, and whether or not to follow-up eventual positive screening results. Pregnant women who wish to be counseled are facilitated in making an informed choice that is in line with their values. However, previous research has shown that discussing values is often considered difficult in daily counseling practice (Prinds et al., 2020). Traditionally, respect for the client’s autonomy and their competence to independently decide what is best for them are considered very important values in counseling (Clarke, 2017; Oduncu, 2002). Furthermore, non-directivity is an evolving concept, and more active and engaged forms of non-directivity have been proposed in which challenging and existential questions can be addressed (Clarke and Wallgren-Pettersson, 2019; Prinds et al., 2020). It is essential that the counselor does not influence the client’s final decision, while at the same time leading the decision-making-process to ensure that the client is not left alone in making these often complex decisions (Clarke and Wallgren-Pettersson, 2019).

Characterization of ‘values’ and ‘beliefs’

To make a clear distinction between ‘values’ and ‘beliefs’, both important concepts in this study, we have described them as follows. ‘Values’ are characterized as guides for desirable behavior. ‘Beliefs’ are characterized as what people perceive to be ‘true’ or ‘false’ (Shealy, 2015). In line with previous research ‘beliefs’ are seen as the foundational components of ‘values’(Shealy, 2015). The importance of recognizing ‘beliefs’ as the fundamental building blocks prevents limiting people’s views to the level of values and therefore from overlooking the variations that occur at the level of beliefs (Shealy, 2015).

Methods

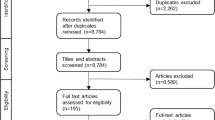

We performed a qualitative interview study among Dutch midwife counselors who offer pregnancy care including the option for prenatal anomaly screening to the vast majority of all pregnant woman in the Netherlands. All included counselors were practicing Christian or Islamic believers according to the three different dimensions of religiosity used in the European Values Surveys, namely practice, belief and self-definition (Molteni and Biolcati, 2018).

Data collection and participants

We conducted semi-structured, open interviews with Dutch counselors between March and June 2018. Purposive sampling was used to recruit practicing religious counselors from Christian or Islamic backgrounds who were also licensed to provide counseling for prenatal anomaly screening. One of the authors (JG) has been working as a midwife counselor, so she recruited the first interviewees. After initial recruitment, snowballing was used to include more midwife counselors until data saturation was reached, which in a purposive sample, typically requires about eight to twelve interviews (Guest et al., 2006).

Procedure

Eligible counselors were invited to participate either by telephone or e-mail, depending on the contact details available. After the initial contact and agreement to participate in the study, counselors received an e-mail containing information about the study, privacy statements, a link to an article about CRISPR-Cas9 (Crispr: vragen rond het wondermiddel voor de ‘betere mens’, 2018 In English: CRISPR: questions on a panacea for the ‘better human’) (FD, 2018), and an informed consent form to sign before the interview. The interview questions were not provided in advance. The interviews were conducted by JG and LM, both researchers, either at a location chosen by the participating counselor or by telephone if convenient to the participants. Only the interviewer and participant were present during the interviews. Field notes were made to contextualize the answers. After permission of the interviewees, the interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. After transcription, the interviews were analyzed using ATLAS.ti software (Version 9). There were three years between conducting the interviews and analyzing the data. To avoid recall bias, it was decided not to conduct a member check.

Instruments

We created a semi-structured interview guide using the literature published by the Beginning of Life Group from Amsterdam UMC location Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (Goekoop et al. 2020; Van Dijke et al. 2018) consisting of five topics: religious worldview, counseling for prenatal anomaly screening, HGE, responsible implementation of HGE, and counseling for HGE (Table 1; See Supplementary Information S1 for the extended interview guide). While analyzing the data, we involved the list of ethical values published by the WHO Expert Advisory Committee (inclusiveness, caution, fairness, social justice, non-discrimination, equal moral worth, respect for persons, solidarity, and global health justice) (Supplementary Information S2) (WHO, 2021), and compared them with the values expressed by the counselors in our study when discussing their perspectives on HGE.

During the interviews, if relevant, we referred to two genetic disorders to discuss the consequences of HGE, if it would become available in the future: Duchenne muscular dystrophy, an early onset, non-treatable disease, and beta-thalassemia, an early onset, hemoglobinopathy ranging from mild (e.g., fatigue) to very severe problems (e.g., serious infections and organ damage).

Data analysis

We used thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) to code and analyze the transcripts as described: (1) becoming familiar with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for categories, (4) reviewing the themes, (5) defining and naming the themes, and (6) writing the report. To achieve inter-subjectivity of results, two researchers (LM, WG) independently coded text fragments from the first five interviews. A third member of the research team (JG) provided feedback. Various categories were extracted from these codes to identify key themes and subthemes in the interviews. The analysis was considered a recursive process and notes were taken continuously. The themes were selected based on their prevalence and/or apparent importance in relation to the research questions. Table 2 shows an example of the coding procedure.

Findings

A total of 14 midwife counselors were invited to participate in this study. Three did not participate for time-related reasons. The interviewers concluded data saturation was reached after interviews with 11 religious female midwives. The Christian participants indicated that they practiced their faith by regularly attending church, praying, and reading the Bible, while the Muslim participants also prayed regularly and considered the Koran to be their guide. In addition, all participants had a strong belief in the supernatural aspects of religion, for example belief in God or the afterlife. Finally, all participants identified themselves as religious people for whom religion is very important. Three participants (2, 3 and 6) appeared to have a family history with a congenital anomaly. The interviews lasted on average 60 min. The background characteristics are presented in Table 3.

Our study explored how midwife counselors for prenatal anomaly screening currently deal with their religious worldview during counseling and how, given their religious worldview, their values influence their perspectives on HGE. Two main themes were identified, as follows: ‘a search for role identity as a healthcare counselor’ (Theme 1) and ‘concerns about the application of HGE’ (Theme 2). These themes and corresponding subthemes are presented in Table 4 and summarized below, illustrated by quotes that were translated from Dutch into English by a professional translator.

Theme 1: Search for role identity as a healthcare counselor

The search for role identity as a healthcare counselor originates from being both a professional healthcare counselor and a practicing Christian or Muslim believer. In questions involving beliefs about the perceived moment a human life begins (e.g., terminating a pregnancy, research on embryos) or the meaning of human suffering, ambivalence arises. Several counselors reflected on this search in which they did not openly bring in their own perspectives during counseling because they felt it might conflict with how they were trained as professionals. They reflected on how they tried to respect the client’s autonomy while also respecting the (unborn) human life that might be threatened by the client’s choice to terminate the pregnancy. Some of them described how they attempted to deal with this tension, sometimes by asking reflective questions (e.g., what if the child would develop a disability later in life), by providing support for possible alternative options (e.g., adoption) or by framing their words (e.g., calling the fetus a child).

Being both a professional healthcare counselor and a practicing believer

Counselors mentioned, more or less explicitly, respecting human life, respecting a client’s autonomy, promoting human health, and (medical) safety as important values during counseling. Almost all counselors mentioned facilitating informed decision making through the provision of relevant and factual information that is consistent with the values of the clients as a very important commitment.

“Did I inform them properly about the ethical aspect or only about the test and what they are going to do? So, in that respect I do feel responsible that they make a choice based on their ethical standards and values.” (R2, Christian)

All participants described themselves as professional healthcare providers as well as practicing believers. When asked about the role their religious worldview plays during counseling, most indicated that although their religious worldview influences every aspect of their lives, they were very cautious not to let it affect their clients’ autonomy. Some counselors also mentioned in this regard the difficulty of remaining non-verbally nondirective.

“I am first and foremost…at my work, I am a midwife. Yes, of course I am [name] and I have an Islamic background, but I work as a midwife, and I work as a sonographer, so I do my screening based on the fact that I am just a professional at that moment. (R11, Islamic)

Because I think that my whole background is irrelevant to someone else. Of course, I can’t erase it for myself, but I think I should try to erase it for someone else.” (R7, Christian)

However, one of the counselors reported actively sharing her worldview during counseling. She explained how she tried to ask existential questions, based on her own values and worldview-based beliefs, while at the same time providing nondirective counseling to help the clients to reflect on their own values and beliefs.

“Well, of course, how it’s often put in counseling training, you know, as if your own opinions don’t matter. But these opinions do matter, we are not alone in the world. We are also there to help each other and find out: where do you stand? And what are other opinions? How comfortable do you feel with that? Or not. And try to find out: why not?” (R9, Christian)

Several participants reported ambivalence when confronted with a client who was considering terminating the pregnancy after an anomaly was detected. Some shared how they tried to counsel nondirectively and respect their client’s autonomy but struggled at the same time with the need to respect-and protect- (unborn) human life.

“I sometimes feel a kind of, how should I put this, a conflict is too strong, but a contrast. I think that as a midwife I should try, because nobody can do that, try to share information objectively, to see where people stand and what they need. But based on my worldview, I think it is very important that people make a well-considered choice and sometimes I have a hard time not paying attention to the voice of the child. So, it’s very much about the parents’ choice, that’s what it’s about, that’s how I was trained and that’s how we agreed.” (R4, Christian)

Despite these internal dilemmas, several counselors mentioned that they realized that they were not ultimately responsible for their clients’ decisions and that, at the same time, they accepted the client’s decision unconditionally.

“However, that was against my principles [abortion of a healthy fetus at 22 weeks pregnancy], but that does not mean that I do not support her. I would give her all the necessary guidance, I would help her, she can come and cry on my shoulder. So, I’m very neutral in that respect.” (R6, Islamic)

The leading role of religious beliefs

When looking closer to the counselors’ values and perceived internal dilemma’s; especially beliefs related to three themes such as ‘God being the creator’, ‘the perceived moment a human life begins’, and ‘the meaning of human suffering’, appear to play a major role in the interpretation of their values. First of all, all counselors expressed their belief in a supreme being (God/Allah) who created every human being which colored for them the interpretation of the value to respect human life.

“I have really come to realize you were created by God; you are here with a purpose and that there is no end to life.” (R1, Christian)

“He [Allah] is the one who decides about life and death. So, he is the one who gives life and takes life.” (R6, Islamic)

In addition, the notion that human life is created intentionally and with a purpose from the earliest beginning until (after) death also seem to color the interpretation of the value to respect clients’ autonomy. Being a creation and not the Creator appears to limit human autonomy regarding decisions involving the beginning and the end of life.

“Yes, what we believe from an Islamic point of view is that God gives you that which you receive, and you must be satisfied with that.” (R11, Islamic)

“Well, actually prior to the [introduction of the] NIPT, we also organized a kind of vision meeting at our practice, about where we stand […] But also to discuss this with each other. Well, for me… well, it’s really at the forefront: ‘I have to obey God more than obey humans’. So, I also say: ‘Yes, I can be forbidden or commanded to do things, but, yeah, what God wants really comes before all else.’” (R9, Christian)

Secondly, when we asked the counselors about the moment at which, according to them, human life begins, several beliefs emerged. One Islamic counselor stated that for her, according to Islam, human life starts at 17 weeks after conception. In Islam scholarly texts, this is often referred to as 120 days. Two others explained that, in Islam (depending on which Islamic school one belongs to), human life officially starts 40 days after conception, however, one of them personally believed that human life begins at conception. Most Christian counselors also believed a human life begins at conception. A few of them indicated that they were not sure when human life begins; however, they regarded a fetus as early life worthy of respect and protection.

“From the moment the soul is breathed into the womb, that’s what I believe happens 40 days after conception.” (R11, Islamic)

“But I find it very hard to say when [life begins], after conception or after the heart has started beating, then you’re not allowed to touch it anymore or something. Somehow, I think you should just stay away from it [the fetus].” (R4, Christian)

Beliefs about the moment a human life begins determined the point at which an embryo or fetus is considered a person or having a ‘soul’, and this influenced counselors’ views on termination. Several counselors mentioned that their desire to respect ‘the voice of the (unborn) child’ sometimes conflicted with their value to respect the client’s autonomy.

“Uhm, and if I confess that life starts from conception, because everything is potentially there to become a complete human being, then I also find it my duty to be the voice of the child - at times. So, sometimes I ask a challenging question.” (R9, Christian)

“If I feel an opening to find out if someone is OK with that [giving the child up for adoption], then I’ll work really hard on it. I will not let someone figure it out for themselves. I think: ‘Will they really figure it out or will they just take the easy way out [termination of the pregnancy]?’ In my eyes, the easy way out.” (R7, Christian)

Thirdly, counselors’ views on disability and sickness appeared strongly intertwined with their beliefs on the meaning of human suffering. Although several different views on suffering were mentioned (e.g., personal growth, a test of faith), most participants believed suffering was an inevitable part of human life and could have intrinsic meaning; therefore, avoiding or preventing suffering at all costs was not always the highest priority.

“Maybe people have to be sick, you don’t know. Yes, it can also be a test for the parents, because everything has a reason somewhere.” (R3, Islamic)

“I personally think, that if there are difficulties…then you can also grow stronger from that, or the people around you, despite the sorrow it may bring.” (R5, Christian)

In addition, some counselors expressed concerns about the current perceived manufacturability of life and striving for perfection, as if only a perfectly healthy life is worth living, which colors their interpretation of the value to respect human life. Some also mentioned personal experiences with children with disabilities which supported the idea that life with a child with a disability can still be good.

“It doesn’t necessarily mean that people who have a condition have no quality of life or are not happy with who they are even if they are experiencing a lot of difficulty or pain.” (R10, Christian)

“Sometimes people can’t just give it a chance for a new life, to wait and see how it turns out. That’s the main thing: it will be fine. I personally think that a child with Down’s syndrome will turn out just fine. With a lot of other syndromes, I think so too.” (R3, Islamic)

Almost all counselors, regardless of their beliefs about suffering, reflected on the contrast between looking at suffering from either a general or a personal point of view, and underlined the importance of tolerance and empathy towards the choices of others, and of a humble attitude as a healthcare counselor.

“I can have an opinion in theory, but I do not know what I would choose to do, because it has never crossed my path. So, I think you have to be very careful with that [presuming what other people should do].” (R8, Christian)

Theme 2: Concerns regarding the application of HGE

When asked about the potential future use of HGE, all counselors were hesitant, although almost all expressed the hope that HGE would prevent the suffering caused by severe hereditary diseases in families. The hesitation concerned, on the one hand, the fear of ‘slippery slopes’ in terms of the shifting lines regarding the assessment of the severity of certain disorders, the appreciation of society for the quality of life of people with disabilities, as well as the diffuse boundaries between treatment, prevention and enhancement. On the other hand, there were concerns about the potential impact on their role as counselors. The perspectives of counselors on the potential future use of HGE were based on the same values they mentioned earlier regarding their current counseling practice: respecting human life, respecting clients’ autonomy, promoting human health, and (medical) safety.

Fear of ‘slippery slopes’

Almost all counselors reflected on the difficulty of deciding which diseases should be considered severe enough to apply HGE, and how this relates to the values of promoting human health through HGE and respecting human life ‘as is’. After further in-depth questioning regarding the use of HGE to ‘prevent’ hereditary diseases, almost all participants reacted hesitantly, expressing their fear that minor illnesses will soon be considered ‘serious’ and that no imperfection would be allowed to remain.

“What I am afraid of is, when is something considered a disease? At a certain point, a crooked toe, is that a disease? I find that very tricky. Are we going to set the boundaries like this, the dividing line for this and that, I find that very daunting as well.” (R4, Christian)

Guided by the value of respect for human life some participants expressed a fear of loss of diversity and a devaluation of the quality of life of people with genetic diseases or disabilities, if HGE would be allowed to promote human health. In this context, many also expressed their concern about the increasing societal pressure to strive for perfection and how HGE can be used as a tool to achieve this, while at the same time jeopardizing the autonomy of expectant parents.

“And when I look at gene modification…at some given moment, will we not accept any deviations anymore? If you have a child with Down’s syndrome and half of your family actually asks why? After all, you can know that nowadays…” (R5, Christian)

In addition, all counselors struggled with a potentially ‘slippery slope’ in using HGE, from preventing severe diseases to the enhancement of non-medical characteristics or traits, based on the conflicting values of promoting human health and the need to respect human life ‘as is’.

“You see, we are actually going to determine for our offspring what we consider to be good. I do think that it is a slippery slope. It’s fine if it’s for medical reasons, but, um, soon there will be no more diversity between people…Then we get a sort of Barbie baby.” (R10, Christian)

The leading role of religious beliefs

The conflicting values experienced by the counselors appear, upon closer inspection, again to be a consequence of their beliefs related to the themes such as ‘God being the creator’, ‘the perceived moment a human life begins’, and ‘the meaning of human suffering’, that color the interpretation of their values. Some counselors, for example, found research on embryos acceptable if it would help ‘prevent’ serious hereditary diseases, because as a healthcare provider promoting human health is considered an important value. However, their belief that life begins at conception meant that they had to respect - and protect - unborn human life.

“My goodness…well…. I don’t really know how I feel about that [research on embryos]. You know, it’s a bit hypocritical to be in favor of one thing, but of course research has to be done in order to get the best technology. So that kind of splits… because on the one hand I think: ‘come on guys, do not perform research on embryos’, but on the other hand, I do think the technology that will be developed as a result of the research is a good thing.” (R7, Christian)

One of the Islamic counselors was very positive about using HGE to prevent serious diseases, because it could be applied before the fortieth day after conception, or before the time she believes that a human life begins. Her values on promoting human health and respecting human life were therefore not in conflict.

“Well, only positive, of course, because then it will finally stop possibly Huntington’s disease, Duchenne, I don’t know what other genetic… um Hemophilia… Well, if those can be stopped, why not? Just perfect…Yes, if it’s well within the 40 days [after conception], I think we should use it.” (R11, Islamic)

Another counselor reflected on her personal dilemma: on the one hand, she wishes it had been possible at the time to apply HGE to help her brother with multiple sclerosis (MS) improve his health and reduce his suffering. On the other hand, she struggles with the extent of the autonomy of people, because she worries that interfering in God’s creation through HGE could be against God’s intention.

“My brother has MS and if I heard that we were going in that direction, that you could cut that piece out of your genes… Yeah, then my first thought would be: do it! But, that’s just a deep wish, a deep desire…. It might not be according to God’s will.” (R8, Christian)

In addition, some other counselors were against HGE in any case, regardless of the severity of the disease. They were convinced the application of HGE would be tampering with God’s creation, ‘as sitting on God’s throne’. To prevent severe hereditary diseases from being passed on to subsequent generations, some said they would refrain from having children and accept having children not genetically related.

“I understand that if a disease like that runs in your family… And you have the chance to pass it on… That must be awful, I wouldn’t wish that on anyone. But for me personally, it would affect my reproductive choices. I would say: ‘Well, this is the suffering we carry in our family, we now know a name for it…perhaps I’m not meant to bear children.’” (R9, Christian)

“As far as I’m concerned, it goes completely against God’s plan. And that we desire to be a little like God ourselves. And that we decide ourselves that something is not acceptable and that we want to cut it out of our human race.” (R10, Christian)

Worries about increasing responsibilities

When asked about their needs as counselors if HGE would be implemented in the future, several counselors reported not feeling sufficiently equipped to give appropriate counseling for HGE, although they expected to receive questions from their clients on the subject. Some said more training in advanced counseling skills is needed, as well as more knowledge and debate about HGE or scripts about (world) religions. Some of them recommended leaving the potential future counseling about HGE to a clinical geneticist, or they recommended training specialized midwife counselors for these advanced reproductive technologies. Counselors pointed to a lack of (medical) knowledge, fear of increased responsibilities, and concerns about counseling clients about a reproductive technology that is considered highly controversial. Some counselors emphasized that although they had objections to the use of HGE, this would not affect their commitment to provide nondirective counseling should HGE become available in the future.

“I think [HGE] is a loaded, how do I put this, a loaded topic. Once there is an assessment, knowing that this is what we are going to do, then as a counselor you must be able to counsel about it. Because I now also counsel about Down’s syndrome, for example, or other syndromes. I have an opinion on that too, but that doesn’t change the fact that I counsel in a neutral way.” (R6, Islamic)

Discussion

Our qualitative study explored how midwife counselors for prenatal anomaly screening currently deal with their religious worldview during counseling and how, given their religious worldview, their values influence their perspectives on HGE.

The study showed that being both a professional counselor and a practicing Christian or Muslim believer may lead to a search for role identity as a healthcare counselor.

In current counseling practice, especially in cases where clients consider terminating their pregnancy after a certain anomaly was detected, important values were sometimes perceived as difficult to reconcile, e.g., respect for client’s autonomy versus respect for unborn human life. The interpretation of these values appeared to be colored by underlying religious beliefs related to themes such as, ‘God being the creator’, ‘the perceived moment a human life begins’, or ‘the meaning of human suffering’. Regarding the potential future application of HGE, most counselors were hesitant. Possible ‘slippery slopes’ were identified regarding the assessment of the severity of certain disorders, the reduced appreciation for the quality of life of individuals with a disability of illness or reduced empathy for parents who chose to welcome a child with a disability, as well as the diffuse boundaries between treatment, prevention and enhancement. If HGE were to become part of health policy, some also feared an extension of their responsibilities if counseling for HGE would also become part of the preconception consultations that midwives currently provide.

A search for role identity as a healthcare counselor

Several counselors reflected on a search for role identity as a healthcare counselor in which they did not openly bring their own perspectives, such as pertaining to the perspective of the unborn child, that stem from their worldview-based beliefs, because they felt it might conflict with how they were trained as professionals.

The Dutch prenatal screening guideline currently focuses on the individual autonomy of the client but does not describe what this means exactly for nondirective counseling in daily practice (RIVM, 2023).

Apparently, the counselors in our study act according to an unwritten rule that is part of their socialization as professional counselors, whereby non-directivity is interpreted as exclusively focusing on the individual autonomy of the parents-to-be, whereby the input of other perspectives or possible alternatives is seen as directive and therefore inappropriate or even forbidden. Non-directiveness is an evolving concept closely related to the concept of ‘autonomy’ and arose as a reaction to eugenics and paternalism (Clarke and Wallgren-Pettersson, 2019). Traditionally, this concept is mainly about what a healthcare counselor is not allowed to do, i.e., not influence the outcome of the decision. There is less clarity on how counselors should act to facilitate decision making, which also appears to be the case for the counselors in our study. They were very aware of the possible influence they may have because of their religious worldview, and most of them seemed to equate steering the outcome of the final decision with bringing in multiple perspectives, for example the perspective of the foetus, during the decision-making-process.

Bringing in multiple perspectives and presenting several alternatives does not necessarily direct the final decision. Ethicists such as Gastmans (2021), suggest that the autonomy of the parents-to-be is particularly respected by bringing in possible alternatives and multiple perspectives including that of the unborn child because it helps the client (and partner) to clarify the actual motivations for the choice they decide to make. The client (and partner) are then really guided to a decision that they can justify to themselves now and in the future, regardless of the final choice (Gastmans, 2021). During the decision-making-process, it is inevitable that the counselor exerts influence, if only through what is asked or not asked and the choice of information provided (Clarke, 2017). Therefore, it is essential for counselors to develop an insight into the influence that might be exerted and how to use this influence to enhance the client’s decision-making process (Kørup et al., 2019).

Looking at the above from the perspective of the three domains of purpose in the medical education of healthcare providers described by Biesta (2020), the following can be observed (Biesta, 2020; Biesta and van Braak, 2020): Regarding the first domain of purpose, the acquisition of knowledge and skills, the counselors in our study seem to feel confident. The challenges the counselors experience as religious healthcare professionals arise in relation to the other two domains of purpose, namely socialization and subjectification, and the balance between them. To give direction to the search for role identity, education should pay more attention to how the initiation of future healthcare counselors into the norms and traditions of their specific professional domain (socialization) relates to the freedom to be ‘a self’ that is responsible for its own actions as an autonomous individual (subjectification) (Biesta, 2020; Biesta and van Braak, 2020).

Concerns about the application of HGE

Although most participants were positive about the use of HGE in the prevention of serious hereditary diseases to promote human health and alleviate suffering, many risks and fears were also mentioned. There were doubts about which diseases should be considered ‘serious’ and who will decide. Most participants indicated that they feared a ‘slippery slope’, whereby the line between ‘serious’ and ‘non-serious’ would shift and could eventually even end up at human enhancement. This notion of a ‘serious’ disease is widely used in the context of HGE but needs further clarification, as it is a relative concept that has many dimensions and is understood differently in various countries and cultures (Boardman and Clark, 2022; Kleiderman et al., 2019; National Academies of Sciences & Medicine, 2017; Wertz and Knoppers, 2002). Based on what we found in our study, this ambiguity might as well be related to worldview-based beliefs regarding human suffering, whereby a ‘meaningful’ view on suffering and vulnerability might lead to a different assessment of what is a ‘serious’ disease and what is not (Hall et al., 2010).

Moreover, some participants expressed their concern, also stated in previous research, about the devaluation of the quality of life of individuals with a disability and a loss of diversity if certain traits were to be considered undesirable (Andorno et al., 2020; McCaughey et al., 2019; National Academies of Sciences & Medicine, 2017; NCOB, 2018; Ormond et al., 2017; WHO, 2021).

The leading role of religious beliefs for several ethical values and principles identified by the WHO Expert Committee

The values suggested by the WHO-expert committee on human genome editing are intended to serve as a guide to ethical questions raised by the potential clinical implementation of human genome editing (WHO, 2021). WHO indicates that human genome editing is a topic of intense debate that touches on deep personal and religious issues for some people because of its possible impact on offspring and the wider society. In their explanation of the value ‘inclusiveness’, WHO mentions the importance of cultural, social and religious beliefs that may play a role in the perspectives on editing the human genome, without elaborating on them (WHO, 2021). Our findings show that the interpretation of at least four of these values (social justice, non-discrimination, equal moral worth, respect for persons) that influence the perspectives on human genome editing are indeed colored by religious beliefs (Supplementary Information S2). This is visible, for example, in beliefs about embryos as persons who are not competent to make their own decisions and whose interests must also be protected when it comes to the use of HGE. Therefore, focusing on the values alone, without explicit attention to religious, cultural, or social beliefs, is not sufficient in day-to-day counseling practice nor is it enough to guide policymakers involved in the possible future implementation of HGE.

The values of ‘fairness’, ‘solidarity’ and ‘global health justice’ were not addressed in our study when the counselors reflected on a possible future application of HGE. All three values specifically address equal access to new technologies for all and avoidance of the exploitation of population groups in relation to research. More research is needed to understand why these considerations were not mentioned. It is obvious, however, that values concerning equal access for all people are of great importance for policymaking worldwide.

Strengths, limitations, and research recommendations

A strength of this study is that, to our knowledge, we are the first to have interviewed practicing Christian and Islamic midwife counselors about the existential aspects of life, values and religious beliefs that might influence their counseling on prenatal screening both now, and reproductive screening in the future, in light of the emergence of new technologies such as HGE. Another strength is the multidisciplinary research group consisting of theologians, geneticists, midwives, psychologists, and sociologists that is at the basis of this study. Moreover, the interviewers were experts in both counseling and religion, which gave the interviews considerable depth. A limitation of the study is that only practicing religious counselors from two religions (Islam and Christianity) were interviewed; also, non-religious, non-practicing religious, or agnostic healthcare professionals and counselors may face challenges in the search for role identity and might have different perspectives regarding the use of HGE.

In line with the worldwide call for broad public engagement to determine whether and when HGE may be ethically permissible, future research should explore the perspectives of other people and communities affected by the implementation of HGE, addressing both their values and the underlying beliefs that may influence their perspectives; people (including counselors) from different (non) religious, cultural, and social backgrounds should be considered to gain a more thorough picture of the influence of different beliefs on the values that people hold important.

Conclusion and practice implications

The present study showed how religious midwife counselors search for ways to harmonize their professional role with their religious beliefs that influence their perspectives on current and emerging reproductive techniques. From the counselors’ reflections in our study on the challenges they face in counseling for NIPT, it became clear that with emerging controversial healthcare innovations such as heritable genome editing (HGE), a search for role identity of the healthcare counselor may arise. Moreover, for HGE, counselors feared ‘slippery slopes’ regarding the assessment of the severity of certain disorders, the reduced appreciation for the quality of life of individuals with a disability or illness, as well as the diffuse boundaries between treatment, prevention and enhancement.

Regarding future implementation, counselors’ medical education might benefit from a focus not only on qualification (e.g., acquiring knowledge and skills) but also on the balance between socialization (e.g., adhering to the norm of nondirective counseling) and subjectification (e.g., being a ‘self’ in relation to everything one has learned). Researchers and policymakers responding to the global call for broad public engagement to explore the acceptability of HGE would do well to pay attention not only to shared values but also to underlying religious, cultural, and social beliefs that color the interpretation of these values.

Data availability

Data are available from the Amsterdam UMC Institutional Data Access/Ethics Committee (contact via Wendy Geuverink) for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data.

References

Almeida M, Ranisch R (2022) Beyond safety: mapping the ethical debate on heritable genome editing interventions. Hum Soc Sci Commun 9(1):1–14

Andorno R, Baylis F, Darnovsky M, Dickenson D, Haker H, Hasson K, Lowthorp L, Annas GJ, Bourgain C, Drabiak K, Graumann S, Grüber K, Kaiser M, King D, Kollek R, MacKellar C, Nie JB, Obasogie OK, Tyebally Fang M, Zuscinova J (2020) Geneva statement on heritable human genome editing: the need for course correction. Trends Biotechnol 38(4):351–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2019.12.022

Baylis F, Darnovsky M, Hasson K, Krahn TM (2020) Human germline and heritable genome editing: the global policy landscape. CRISPR J 3(5):365–377

Biesta G (2020) Risking ourselves in education: qualification, socialization, and subjectification revisited. Educ Theory 70(1):89–104

Biesta GJJ, van Braak M (2020) Beyond the medical model: thinking differently about medical education and medical education research. Teach Learn Med 32(4):449–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2020.1798240

Bioethics N (2018) Genome Editing and Human Reproduction: Social and Ethical Issues. Nuffield Council on Bioethics, London

Blythe JA, Curlin FA (2019) How should physicians respond to patient requests for religious concordance? JAMA Ethics 21(6):E485–E492. https://doi.org/10.1001/amajethics.2019.485

Boardman FK, Clark CC (2022) What is a ‘serious’ genetic condition? The perceptions of people living with genetic conditions. Eur J Hum Genet 30(2):160–169

Botkin JR (1998) Ethical issues and practical problems in preimplantation genetic diagnosis. J Law Med Ethics 26(1):17–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-720x.1998.tb01902.x

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101

Brezina PR, Kearns WG (2014) The evolving role of genetics in reproductive medicine. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 41(1):41–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2013.10.006

Clarke A (2017) The evolving concept of non-directiveness in genetic counselling. In History of Human Genetics (pp. 541–566). Springer

Clarke AJ, Wallgren-Pettersson C (2019) Ethics in genetic counselling. J Commun Genet 10(1):3–33

Coller BS (2019) Ethics of human genome editing. Annu Rev Med 70:289–305. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-112717-094629

Curlin FA, Lawrence RE, Chin MH, Lantos JD (2007) Religion, conscience, and controversial clinical practices. N Engl J Med 356(6):593–600

Curlin FA, Tollefsen CO (2019) Conscience and the way of medicine. Perspect Biol Med 62(3):560–575

Daley GQ, Lovell-Badge R, Steffann J (2019) After the storm—a responsible path for genome editing. N Engl J Med 380(10):897–899

Davies B (2019) The technical risks of human gene editing. Hum Reprod 34(11):2104–2111

Evitt NH, Mascharak S, Altman RB (2015) Human germline CRISPR-Cas modification: toward a regulatory framework. Am J Bioeth 15(12):25–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2015.1104160

FD (2018) Crispr: vragen rond het wondermiddel voor de ‘betere mens’. FD. https://fd.nl/morgen/1248322/crispr-vragen-rond-het-wondermiddel-voor-de-betere-mens

Gastmans C (2021) Kwetsbare waardigheid : ethiek aan het begin en einde van het leven. Pelckmans Uitgevers

Gitsels-van der Wal JT, Martin L, Manniën J, Verhoeven P, Hutton EK, Reinders HS (2015) A qualitative study on how Muslim women of Moroccan descent approach antenatal anomaly screening. Midwifery 31(3):e43–e49

Goekoop FM, Van El CG, Widdershoven GA, Dzinalija N, Cornel MC, Evans N (2020) Systematic scoping review of the concept of ‘genetic identity’ and its relevance for germline modification. PloS one 15(1):e0228263

Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L (2006) How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18(1):59–82

Hall MEL, Langer R, McMartin J (2010) The role of suffering in human flourishing: contributions from positive psychology, theology, and philosophy. J Psychol Theol 38(2):111–121

Iltis AS, Hoover S, Matthews KR (2021) Public and stakeholder engagement in developing human heritable genome editing policies: what does it mean and what should it mean? Front Polit Sci 117

Kleiderman E, Ogbogu U (2019) Realigning gene editing with clinical research ethics: What the “CRISPR Twins” debacle means for Chinese and international research ethics governance. Acc Res 26(4):257–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2019.1617138

Kleiderman E, Ravitsky V, Knoppers BM (2019) The ‘serious’ factor in germline modification. J Med Ethics 45(8):508–513

Kørup AK, Søndergaard J, Lucchetti G, Ramakrishnan P, Baumann K, Lee E, Frick E, Büssing A, Alyousefi NA, Karimah A (2019) Religious values of physicians affect their clinical practice: A meta-analysis of individual participant data from 7 countries. Medicine 98(38)

Li G, Liu X, Huang S, Zeng Y, Yang G, Lu Z, Zhang Y, Ma X, Wang L, Huang X (2019) Efficient generation of pathogenic A-to-G mutations in human tripronuclear embryos via ABE-mediated base editing. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 17:289–296

Ma H, Marti-Gutierrez N, Park SW, Wu J, Lee Y, Suzuki K, Koski A, Ji D, Hayama T, Ahmed R, Darby H, Van Dyken C, Li Y, Kang E, Park AR, Kim D, Kim ST, Gong J, Gu Y, Mitalipov S (2017) Correction of a pathogenic gene mutation in human embryos. Nature 548(7668):413–419. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature23305

Martin L, Gitsels-van der Wal JT, Bax CJ, Pieters MJ, Reijerink-Verheij JCIY, Galjaard R-J, Henneman L, Dutch NC (2022) Nationwide implementation of the non-invasive prenatal test: evaluation of a blended learning program for counselors. PloS One 17(5):e0267865. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0267865

Martin L, Hutton EK, Gitsels-van der Wal JT, Spelten ER, Kuiper F, Pereboom MT, van Dulmen S (2015) Antenatal counselling for congenital anomaly tests: an exploratory video-observational study about client–midwife communication. Midwifery 31(1):37–46

Matthews KR, Iltis AS (2019) Are we ready to genetically modify a human embryo? Or is it too late to ask? Account Res 26(4):265–270

McCaughey T, Budden DM, Sanfilippo PG, Gooden GE, Fan L, Fenwick E, Rees G, MacGregor C, Si L, Chen C (2019) A need for better understanding is the major determinant for public perceptions of human gene editing. Hum Gene Ther 30(1):36–43

Molteni F, Biolcati F (2018) Shifts in religiosity across cohorts in Europe: a multilevel and multidimensional analysis based on the European Values Study. Soc Compass 65(3):413–432

Morrison M, de Saille S (2019) CRISPR in context: towards a socially responsible debate on embryo editing. Palgrave Commun 5(1):1–9

National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Medicine, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2017) Human genome editing: science, ethics, and governance. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24623

National Academy of Medicine; National Academy of Sciences; The Royal Society, International Commission on the Clinical Use of Human Germline Genome Editing (2020) The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In Heritable Human Genome Editing. National Academies Press (US) Copyright 2020 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. https://doi.org/10.17226/25665

NCOB (2018) Genome editing and human reproduction: social and ethical issues. https://www.nuffieldbioethics.org/publications/genome-editing-and-human-reproduction

Niemiec E, Howard HC (2020) Germline genome editing research: what are gamete donors (not) informed about in consent forms? CRISPR J 3(1):52–63. https://doi.org/10.1089/crispr.2019.0043

O’Neill HC (2020) Clinical germline genome editing: when will good be good enough? Perspect Biol Med 63(1):101–110

Oduncu FS (2002) The role of non-directiveness in genetic counseling. Med Health Care Philos 5(1):53–63

Ormond KE, Mortlock DP, Scholes DT, Bombard Y, Brody LC, Faucett WA, Nanibaa’A G, Hercher L, Isasi R, Middleton A (2017) Human germline genome editing. Am J Hum Genet 101(2):167–176

Perined (2021) Kerncijfers Nederlandse geboortezorg 2021. Retrieved December 6th 2023 from https://www.perined.nl/onderwerpen/publicaties-perined/kerncijfers-2021

Prinds C, der Wal JG, Crombag N, Martin L (2020) Counselling for prenatal anomaly screening-A plea for integration of existential life questions. Patient Educ Couns 103(8):1657–1661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2020.03.025

Ranisch R (2020) Germline genome editing versus preimplantation genetic diagnosis: Is there a case in favour of germline interventions? Bioethics 34(1):60–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12635

RIVM (2023) Kwaliteitseisen-counseling-prenatale-screening. Retrieved December 6th 2023 from https://www.pns.nl/documenten/kwaliteitseisen-counseling-prenatale-screening

Scheufele DA, Krause NM, Freiling I, Brossard D (2021) What we know about effective public engagement on CRISPR and beyond. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(22)

Shealy CN (2015) Making sense of beliefs and values: Theory, research, and practice Springer Publishing

Steffann J, Jouannet P, Bonnefont JP, Chneiweiss H, Frydman N (2018) Could failure in preimplantation genetic diagnosis justify editing the human embryo genome? Cell Stem Cell 22(4):481–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2018.01.004

Van Dijke I, Bosch L, Bredenoord AL, Cornel M, Repping S, Hendriks S (2018) The ethics of clinical applications of germline genome modification: a systematic review of reasons. Hum Reprod 33(9):1777–1796

Van Randwijk C, Opsahl T, Assing Hvidt E, Bjerrum L, Kørup AK, Hvidt NC (2020) Association between Danish physicians’ religiosity and spirituality and their attitudes toward end-of-life procedures. J Relig Health 59:2654–2663

Van Randwijk CB (2018) Beliefs and values of Danish physicians: and implications for clinical practice

VWS (2013) Regeling preïmplantatie genetische diagnostiek. Retrieved January 19th from https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0025355/2013-04-06

Wertz DC, Knoppers BM (2002) Serious genetic disorders: can or should they be defined? Am J Med Genet 108(1):29–35

WHO (2021) Human genome editing: a framework for governance. Retrieved August 10th 2022 from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030060

Zeng Y, Li J, Li G, Huang S, Yu W, Zhang Y, Chen D, Chen J, Liu J, Huang X (2018) Correction of the Marfan syndrome pathogenic FBN1 mutation by base editing in human cells and heterozygous embryos. Mol Ther 26(11):2631–2637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.08.007

Zhang M, Zhou C, Wei Y, Xu C, Pan H, Ying W, Sun Y, Sun Y, Xiao Q, Yao N (2019) Human cleaving embryos enable robust homozygotic nucleotide substitutions by base editors. Genome Biol 20(1):1–7

ZonMw (2021) Preconceptionele dragerschapsscreening in Nederland: gevolgen, maatschappelijk draagvlak en ethische aspecten Retrieved April 5th 2022 from https://www.zonmw.nl/nl/onderzoek-resultaten/kwaliteit-van-zorg/programmas/project-detail/ethiek-en-gezondheid-3/preconception-carrier-screening-in-the-netherlands-advantages-and-consequences-societal-support-an/

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Janneke Gitsels, Linda Martin and Wendy Geuverink. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Wendy Geuverink and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

As of 1st September 2022, the authors Wendy Geuverink, Martina Cornel, and Carla van El are involved in a Netherlands Consortium “Public Realm Entrance of Human Germline Gene Editing” funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) with project number [NWA.1389.20.075]. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The Medical Ethics Committee of Amsterdam UMC location VUMC, reviewed and waived this study as human subject research (Ref nr. 2018.271).

Informed consent

All participating midwife counselors were given both oral and written information about the aim of the study prior to the interview. All were informed about confidentiality, the anonymity of the quotes and the option to withdraw at any time without giving any reason. All participants gave their oral and written informed consent to participate by signing an informed consent form.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Geuverink, W.P., Gitsels, J.T., Cornel, M.C. et al. The impact of counselors’ values and religious beliefs on their role identity and perspectives on heritable genome editing: a qualitative interview study. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1074 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03576-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03576-3