Abstract

Throughout the historical process of institutional change, traditional family fertility values (TFFV) have largely persisted and been preserved as an informal institution, maintaining a substantial influence in present times. Building upon reflections on the theory of endogenous institutional change aimed at reducing transaction costs, there’s significant merit in harnessing TFFV to enhance governance efficiency. Drawing on the CFPS data from 2010 to 2018, this study examines the impact of TFFV on the performance evaluation of grassroots governments. Results indicate that TFFV have a more pronounced influence in rural areas compared to urban regions, and significantly affects the evaluation of grassroots government performance. This influence remains uninfluenced by internet and exhibits an inverted U-shaped pattern. Additionally, its influence on the evaluation of government work performance becomes even more noteworthy when TFFV are more emphasized. The reasons for these observations lie in the endogenous characteristics of TFFV, closely tied with traditional political values and affected by clan culture. Given that the endogenous trajectory is difficult to alter and cannot be overlooked, it’s imperative to factor in TFFV when governing rural grassroots. Governance strategies should be tailored depending on the varying influence of traditional values in different regions to optimize governance efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Within the values of Chinese traditional culture, Confucianism and the family hold central roles. Confucian family values emphasize the importance of having male children to continue one’s family line and to care for one’s parents in old age. It teaches that having children is a way of fulfilling one’s duty to society and to one’s ancestors (Liao et al. 2010; Zhai 2018). Although such traditional family fertility values (TFFV) clash with the modern governance concept of gender equality (Jamil et al. 2022; Profeta 2020; Seo et al. 2022), they still wield a strong influence in Chinese society. For example, despite efforts by the Chinese government to control the influence of TFFV on gender imbalances, 2019 data still showed that the male-to-female newborn ratio was higher than the global average (Tang 2021). TFFV themselves are not merely about specific childbirth choices; as an aspect of traditional family values, they also reflect the essence of traditional family values in Chinese society, including filial piety, family responsibilities, blood relations, and clan concepts (Tang & Zhao 2023; Zhang 2019). These values, combined with the dependency relationship between families and governments in Confucian culture (Pye 1968), the central role of traditional family values in traditional culture (Zhai 2018), and TFFV as an embodiment of traditional family values, as well as the influence of clan networks on governmental governance (Cao et al. 2022; Huang et al. 2018), necessitate a reflection on whether TFFV impact governmental governance, especially at the grassroots level. This is paramount as grassroots governments have direct contact with the public, making their study particularly relevant.

Although scholars have delved deeply into the relationship between traditional culture and government governance, the narrow field focusing on the interplay between Chinese TFFV and grassroots governance seems relatively overlooked (Anh Vu et al. 2022; Dussauge 2011; Munshi & Rosenzweig 2008). Most research concentrates on interpreting trust in central governments from traditional cultural values, with scant literature delving into its impact on grassroots governance (Chen 2017; Li 2016, 2022; Niu & Zhao 2018; Wu et al. 2020; Xi & Ratigan 2023; Zhai 2022). In China, grassroots governments play a pivotal role, interacting directly with the public and implementing central government policies. Hence, understanding the potential influence of TFFV on their governance is crucial. First, TFFV inherently encompass traditional political values. Studies suggest that Confucian concepts of “ren” (benevolence) play a key role in enhancing people’s trust in central leadership, making them believe that such leaders inherently possess high benevolence (Liu et al. 2015; Tu 1993). This trust, as emphasized by Ham (2004), might stem from traditional Confucian family values (Ham 2004). Given this, it’s reasonable to infer that TFFV, being an embodiment of family values, could also influence grassroots governance—reflecting its essence of traditional political values. Furthermore, TFFV are not just significant embodiments of traditional family values but further encapsulate the profound connotations of clan culture. This culture, as an informal institution, may influence the formal institution, namely the governance of grassroots governments (Huang et al. 2018; Xu & Xia 2023). Especially when clan cultural awareness is strong, it might distort traditional political values, further implying that the impact of TFFV on grassroots government governance varies. However, existing literature on TFFV focuses on demographic issues or resultant social problems, with limited exploration into public management issues (Kumar & Sinha 2020; Shen et al. 2021; Song et al. 2022). This research aims to address this gap. The reason for concentrating on government performance evaluation is its significant academic value, which has been discussed in various literature pieces. For instance, the goal-oriented government performance evaluation is seen as a crucial tool for enhancing governmental efficiency (Chen et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2017). This research, similarly oriented toward results-based performance evaluation, places a stronger emphasis on the practical effects of grassroots governance. This approach helps grasp the public’s most direct feelings about governmental performance. Compared to evaluation of government officials and political systems, it sidesteps topic sensitivity, thereby avoiding distortions in evaluation outcomes (Zhai 2018). This could guide more effective measures in public management (Lee 2022) and lead to better policy recommendations.

In summary, this paper will mainly focus on the impact and mechanisms of TFFV on grassroots government evaluation. The theoretical analysis will primarily be grounded in the concept of traditional thinking as an informal institution, its endogenous institutional characteristics, and the relationships between TFFV, traditional family values, and traditional political values. The study will also address the influence of clan culture on governance. In terms of research methodology, this paper mainly employs a double fixed-effects model to eliminate biases that regional and temporal factors might introduce to the estimations. Simultaneously, to address potential endogeneity issues in the model, we introduce the instrumental variable method. Moreover, we also use a mediation effect model to analyze the mechanisms through which TFFV influence the performance evaluation of grassroots governments.

Theoretical analysis and hypothesis

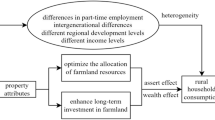

TFFV might have a significant influence on the evaluation of grassroots government. This influence is rooted in how TFFV shape citizens’ political judgment and the implicit influence of clan culture on government governance. TFFV, being a vital embodiment of traditional family values, have endogenous characteristics. The origin of this endogeneity can often be attributed to the level of social productivity of the time and its inherent Chinese traditional family values. Once these values take root in an individual, they become hard to change. Such endogenous institutions are foundational in affecting societal trust. China has developed an endogenous institutional type of societal trust based on Confucian morals (Greif & Laitin 2004; Dong 2005; North 1990). This is key to how TFFV affect the performance evaluation of grassroots governments. Within China’s governance framework, traditional family values, including TFFV, form the basis of Confucian political value “ren.” This is because “ren” is founded on family ethics. Concepts emphasized in traditional family values such as filial piety, responsibility, and the unity of family and country are precisely the embodiment of “ren” (Confucius 1979; Mencius 1984). Therefore, TFFV, as a comprehensive reflection of traditional family values, inevitably influence grassroots governance by shaping people’s political value judgments, especially as Confucian teachings deeply ingrain expectations for those in governance, such as “ren” and a sense of responsibility. As the public, being vital carriers of traditional cultural values, establish their primary connection with the government through grassroots governments, their political consciousness rooted in TFFV would first affect their trust in the grassroots government, and subsequently, their evaluation of its performance. The endogenous nature of TFFV ensures that they maintain significant influence even when faced with societal changes, suggesting a strong impact on governmental work evaluation. Furthermore, the influence of TFFV on grassroots government evaluation might also stem from the underlying competition between clan networks and government governance. TFFV have strong ties to clan culture, essential for the preservation of clans, especially in areas of China with a rich clan culture (Ying et al. 2017; Zhang 2019). Previous scholars have noted that while clan networks can assist administrative interventions, they might also hinder grassroots democratic governance (Qiu & Luo 2023). There is an apparent conflict between these informal and formal organizations over grassroots governance power. Regardless, they both highlight the influence of TFFV on grassroots government governance. While the aforementioned explains the potential impact of TFFV on grassroots government evaluation, this influence might vary. For instance, within the same region, different individuals might be influenced by varying family environments, leading to different levels of adherence to TFFV. This variation can affect the level of trust displayed toward the grassroots government, reflecting the differing intensity of clan culture, leading to inconsistencies in the impact of TFFV on evaluation of grassroots government performance. Based on the aforementioned considerations, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: TFFV influence public evaluation of grassroots government performance, and this impact may vary based on the intensity of adherence to TFFV.

The impact of TFFV on the performance evaluation of grassroots government might be affected by external factors. Two main factors are of particular interest: urban–rural disparities and the use of the internet. Compared to urban areas, rural regions in China are more profoundly influenced by traditional values (Chen 2020; Wu et al. 2020). This is partly because of the relatively lower mobility in rural China, resulting in a stronger adherence to traditional values. This forms the basis for the assertion that TFFV might vary between urban and rural areas. Fundamentally, this variation depends on disparities in economic and educational factors between urban and rural areas, which can impact traditional values, including TFFV, leading to different outcomes in government governance. At the same time, the lower trust displayed by rural areas toward the government suggests that the influence of TFFV on government performance evaluation in these areas might be complex (Breeman et al. 2013; Liu 2015). However, this does not negate the analysis of the influence of TFFV in urban areas. China’s urbanization rate only reached 50%Footnote 1 in 2011, and a significant proportion of the urban population is constituted by the “first generation city dwellers,” those whose parents resided in rural areas. These individuals, despite living in cities, are still deeply influenced by traditional values due to their upbringing and are likely influenced by TFFV in their evaluation of urban grassroots government performance (Leng et al. 2020). However, as the number of the “second generation” and “third generation city dwellers” increases, the influence might be weakening.

The internet plays a crucial role in shaping individual values. While TFFV influence the formation of individual values, the rapid rise of the internet will inevitably impact their influence, including potentially diminishing the role of clan networks in grassroots governance (Qiu & Luo 2023). For instance, Galperin & Arcidiacono (2021) found that in Latin American countries, the use of the internet helps to challenge traditional gender roles and break information barriers, thereby creating more job opportunities for women. This employment impact largely arises from the flexible work environment enabled by the internet, allowing women to find a balance between work and family. However, while considering the relationship between TFFV, grassroots government performance evaluation, and the internet, it’s essential not to overlook the prevailing context of “modern cynicism” (Mazella 2007). For example, the internet offers a platform for Chinese citizens to voice opinions on public matters, and they often creatively employ quotes, allusions, and satire (Wu & Fitzgerald 2021). In this context, the influence of TFFV on grassroots government performance evaluation might not be weakened like other traditional concepts by the internet; instead, it might be intensified when considering government performance evaluation. Based on the above, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: The influence of TFFV on grassroots government performance evaluation varies between urban and rural areas. However, this impact might be uncertain due to the unique role of the internet in government evaluation.

In Hypothesis 1, it was proposed that the influence of TFFV on government trust might vary based on the intensity of these values. Essentially, this is rooted in the impact of TFFV on citizens’ political judgments and the changes in traditional political values when affected by the interplay between clan culture and government governance. This manifests specifically in shifting attitudes toward “rule by man.” Wei (2007) pointed out the characteristics of “hierarchy” and “rule by man” inherent in traditional Confucian culture, leading directly to issues like a consciousness of power hierarchy and lax law enforcement among public servants. This insight provides a direction for the analysis mechanism in this paper. When studying the mechanism of TFFV’s influence on grassroots government performance evaluation, it is not only essential to base the study on the familial ethical foundation of traditional political values but also imperative to consider the traditional element of “rule by man”—this is central to understanding the mechanism.

China’s political development has been profoundly influenced by Confucianism. Confucian culture advocates that rulers should govern based on virtue, which enhances the public’s trust in the system and respect for the rulers (King & Bond 1985). This, in turn, elevates evaluation of grassroots governmental work. Essentially, this trust in grassroots government is rooted in trust and respect for the “ren” of the rulers. This largely explains the positive influence on grassroots government, especially when clan culture is weak and does not challenge the governance of the grassroots government. In such scenarios, traditional political values still play a dominant role. On the other hand, when TFFV are intense, it indirectly reflects a strong clan culture. Clan power shows sensitivity to grassroots government governance, especially when their interests are threatened. Citizens’ traditional political values might shift, for instance, Confucian thoughts such as “not worrying about scarcity, but about inequality” might reduce trust in the public sector (Wang & Zhao 2021). Moreover, corruption issues among local administrators and politicians can lead to increased resident dissatisfaction with the government and a decline in institutional trust (Villoria et al. 2013). It is worth noting that the aforementioned consideration of corruption is also based on corruption within “rule by man,” which is one of the negative sources impacting evaluation of grassroots government performance. Based on the above elucidation, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: The mechanism of TFFV’s impact on government evaluation is based on its influence on citizens’ political judgments and the changes in traditional political values when embedded in clan culture.

Model identification and data sources

Benchmark model

The research in this article focuses on the impact of TFFV on the performance evaluation of grassroots governments, while paying attention to the non-linear characteristics of this impact. Based on panel data, this article constructs the following benchmark model.

The above equation shows the situation of the benchmark model, where \({\rm{evaluation}}_{{it}}\) is the individual \(i\) on the performance of grassroots government work at time \(t\). Similarly, the \({\rm{tradition}}_{{it}}\) represents the degree of TFFV for individual \(i\) at time \(t\), \({\alpha }_{1}\) and \({\alpha }_{2}\) are the corresponding coefficients, \(\beta\) is the coefficient vector for the control variables, \(X\) is the matrix of control variables, \({\mu }_{i}\) represents the individual effect, \({\theta }_{t}\) is the time effect, and \({\varepsilon }_{{it}}\) is the disturbance term.

Variables and data sources

The data used in this article come from three waves of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) conducted in 2010, 2014, and 2018. The CFPS data cover 25 provincial-level administrative regions in China and represent about 95% of the national population. The data sampling method uses the implicit stratification method to extract multi-stage equal probability samples, and in particular, a random starting point cycle interval sampling method is used for the sample households in the third stage to reduce endogeneity issues caused by sampling. Additionally, considering the efficiency of the estimates and the non-linear estimation methods used in this paper, the use of weights has not been taken into account (Korn & Graubard 1995).

Performance evaluation of grassroots government work

The dependent variable is the overall evaluation of grassroots government work. The performance of government work is not only a key factor in the public’s evaluation of the government, but also a comprehensive indicator that implies the perception of the public on the efficiency and service consciousness of government work, reflects the recognition of government work and the legitimacy of the government. Both new public management theories and emerging new public governance theories place government evaluation at the core of their theoretical frameworks (Hyndman & Liguori 2016; Osborne 2009). Therefore, the use of government evaluation as the dependent variable in this study is theoretically reasonable. The evaluation of grassroots government performance in this study refers to the overall evaluation of the work performance of county or county-level city, or district government in the questionnaire. Compared to the central and provincial levels of government, this is a more grassroots comprehensive evaluation of government work, so the respondents have a more intuitive evaluation and perception of it. The evaluation scores range from 1 to 5, with 5 indicating great achievements, highlighting the strong recognition and satisfaction with government work.

Traditional family fertility values

The core explanatory variable in this study is the degree of emphasis on “continuing the family line” as a measure of the degree of TFFV. The collection of this indicator will specifically indicate the importance of at least having one male child in the questionnaire survey, with values ranging from 1 to 5, where 1 represents unimportant and 5 represents very important. The selection of this indicator to measure TFFV is mainly based on the following two reasons. First, as an informal institution, it still has influence in today’s Chinese society. Greif (2006) believes that traditional cultural values can be sustained because there are certain “quasi-parameters” that give continuous positive and negative feedback to the concept of “continuing the family line” and achieve balance. In the early stages, the “quasi-parameters” factors included the requirements of productivity in backward agricultural production, which have been gradually impacted by technology nowadays, but the influence of “quasi-parameters” still exists in society, such as gender discrimination in the workplace based on cost considerations, which have a positive feedback effect to a certain extent on “continuing the family line.” In addition, there has been positive feedback on this concept in many regions, as evidenced by the serious gender imbalance in Chinese society. Furthermore, “continuing the family line” is a typical Confucian TFFV. Chinese traditional culture is deeply influenced by Confucianism, and a typical manifestation of Confucian culture is in the concept of reproduction. The most well-known saying in Confucianism is from its founder, Mencius: “There are three unfilial acts: the greatest of these is to have no offspring.” Often, reproductive concepts are combined with the concepts of filial piety and male superiority and female inferiority, further deepening the legitimacy of “continuing the family line,” such as “Filial piety is the foundation of virtue,” and “Women are human beings, who follow their fathers and brothers when young, their husbands when married, and their sons when widowed.” The above TFFV further reinforce this concept, so choosing “continuing the family line” to measure TFFV is highly representative.

Other main variables

The relevant control variables of the model include gender, age, Communist Party membership, satisfaction with life, confidence in the future, years of education, and logarithmically transformed per capita net income and logarithmically transformed transfer income per household. The selection of these control variables is based on considerations of individual characteristics, family circumstances, and government-level factors. The model also takes into account the impact of geographical and temporal factors. In the following, some of the control variables will be further elaborated.

Regarding the selection of the marriage control variable, this study uses the existence of marriage experience as a threshold. Therefore, divorced, widowed, and other marital statuses are also considered to have marriage experience. The basis for this division is that the occurrence of marriage brings changes in rights and obligations for both parties, and this change has a legal basis. For example, marriage creates a mutual obligation of support between the parties, which is bound to affect their value judgments. In the case of the two variables of satisfaction with life and confidence in the future, a rating scale of 1–5 is used, with higher scores indicating higher levels of satisfaction. The former represents satisfaction with current life, while the latter represents expectations for future life. As for per capita net income and transfer income per household, both are converted based on the year 2010 to ensure comparability of income data, and logarithmic transformation is applied to reduce the occurrence of heteroscedasticity in the model. Per capita net income can measure the economic situation of the household and the impact of initial distribution on government performance evaluation. Transfer income per household measures the impact of redistribution on government performance evaluation, and mainly includes transfer income from government departments such as retirement benefits and subsistence allowances, i.e., secondary distribution income. In addition, considering the potential impact of the internet on traditional concepts and thus on government performance evaluation, this study introduces a virtual variable of internet use. To facilitate analysis, all respondents who reported using the internet on a mobile phone or computer are considered to have engaged in internet use. Table 1 provides an overview of the variables.

From Table 1, it can be seen that the mean of the government’s performance evaluation is slightly above average. In the core explanatory variable section, the level is also slightly above average, indicating that the overall level of TFFV of the respondents is relatively high. If we further examine the data by hukou (China’s household registration system), in the urban sample, the mean value of TFFV is 3.465, while the rural sample mean value is 3.966, indicating that the TFFV are deeper in rural areas, which is in line with our general understanding. However, it is also found that the degree of TFFV among the urban population is also slightly above average, which is worth paying attention to. This also suggests that in subsequent analyses, while focusing on the differences between samples, we should not ignore the analysis of the urban sample.

Model endogeneity and problem identification

Regarding the endogeneity problems of the model, they may arise in three directions: double causality, measurement errors in data, and omitted variables. Regarding double causality, it does not exist in this model because TFFV are a mode of thinking and a long-standing social phenomenon. Its long-term existence indicates that it has reached a certain equilibrium state, which is clearly not actively influenced by government performance evaluation. Regarding measurement errors in data, this study uses panel data to reduce the measurement errors that may result from relying solely on cross-sectional data. To further reduce the statistical errors that may occur in the data, as mentioned earlier, the same statistical caliber as in 2010 was used in the relevant data. Moreover, the CFPS database itself is an authoritative tracking survey database in China, which conducts research at the individual, family, and community levels and uses a stratified multi-stage probability sampling design to further reduce the possible data measurement errors. Regarding the problem of omitted variables, this study first introduces individual fixed effects and time fixed effects to resolve the possible omitted variables that do not vary over time. Meanwhile, in the subsequent regression, the omission variables between urban and rural areas are resolved through the classification regression between urban and rural areas. The most important thing is that this study further reduces the estimation bias that may be caused by omitted variables by introducing instrumental variables.

Throughout the text, instrumental variables are used multiple times for two-stage least squares regression. In the main regression, the TFFV of other family members is introduced as an instrumental variable to resolve the endogeneity caused by TFFV. Equation (2) is the first-stage model in two-stage least squares, where \({\rm{e}{{tradition}}}_{{it}}\) is the degree of TFFV of other family members, \({X}_{{it}}\) is the corresponding control variable matrix, and fixed effects are also controlled in the first stage. In the mechanism test, individual trust preferences and corruption sensitivity of other family members are respectively introduced as instrumental variables for government officials’ trust and personal corruption sensitivity. The use of the above instrumental variables meets the relevant test conditions, and it will be elaborated in detail in the subsequent analysis.

Mechanism testing

As previously mentioned, the changes in evaluation of grassroots government governance due to TFFV manifest specifically in shifting attitudes toward “rule by man.” Confucian culture itself holds “rule by man” in high regard. This concept emphasizes educating and setting moral standards for society to promote social harmony. Under this influence, interpersonal relationships or become crucial. Dong (2005) pointed out that a significant reason for the inefficiency in law enforcement in contemporary society is the infiltration of interpersonal relationships. When discussing the influence of TFFV on government work performance evaluation, the element of “rule by man” is inseparable. It is essential to consider the characteristics of TFFV that intertwine with political values, and this is a crucial entry point for analyzing the varied impacts of TFFV.

This paper separately examines two different pathways: trust in government officials and sensitivity to corruption, to investigate the impact of TFFV on government work performance evaluation. Table 2 shows the relevant variables involved in the mechanism test. The data in Table 2 are also aimed at mechanism testing for the years 2010–2018. Due to the absence of certain mediatory variables in the 2010 survey questionnaire, this paper compensates for the missing mediatory variables of 2010 using similar data from 2011 or 2012. Additionally, since preferences regarding trust and sensitivity to corruption are personal and unlikely to change in the short term, using survey data from the aforementioned 2 years for substitution is considered reasonably valid. Furthermore, since mechanism testing unfolds from both sides and primarily investigates the mechanisms in rural areas, the mediatory variables account for 90.44% of the total sample on the left side and 71.16% on the right side, which provides a certain level of representativeness. Moreover, by introducing instrumental variables into the mediation effects, the robustness of the mechanism study is further ensured.

TFFV and government performance evaluation

Benchmark regression

The benchmark regression equation examines whether TFFV have an impact on government work performance evaluation. The model introduces individual and time fixed effects. In selecting the model, the panel OLS model is used for the benchmark regression model, combined with the measurement methods of subjective evaluation in mainstream literature. In the robustness test, the panel ordered response model is used to transform the explanatory variable into a sufficient statistical quantity for the binary selection model (Das & van Soest 1999). Table 3 shows the results of the benchmark regression.

(1)~(3) are all individual and time fixed effects models, while provincial fixed effects do not vary over time and will be eliminated in the model. Therefore, they are not considered here. Moreover, adding more dimensions of fixed effects will reduce the sample size. Otherwise, some data that only appears once may exaggerate the statistical significance and lead to statistical inference errors.

Model (1) displays the relationship between TFFV and government work performance evaluation. It is evident that TFFV has a significant positive effect on government work performance evaluation. In the baseline Model (2), this study introduces control variables to further test whether the impact of TFFV on government work performance evaluation is robust. Model (2) shows that, at a 5% significance level, the influence of TFFV on government work performance evaluation, although reduced, remains significant, confirming the genuine effect of TFFV on government work performance evaluation. To delve deeper into the changes in the influence of TFFV on grassroots government work performance evaluation, the authors introduced the squared term of TFFV in the baseline Model (3). One can observe that the marginal effects and significance of the control variables did not undergo significant changes. However, the coefficient of the squared term of TFFV is significantly negative. To verify whether the above results are robust, the following analysis will introduce instrumental variables.

Panel two-stage least squares estimation

Although this article has eliminated the endogeneity issue caused by omitted variables by controlling for fixed effects, the endogeneity issue in the model cannot be completely resolved, especially since this article measures TFFV by the emphasis on “continuing the family line,” which cannot guarantee that there are no other variables related to TFFV in the disturbance term. Therefore, in this section, instrumental variables are used to address the potential issue of omitted variables, and the panel two-stage least squares method is used here.

The selection of instrumental variables needs to meet two basic conditions: relevance to the endogenous variable and exogeneity with respect to the disturbance term. In this article, the average TFFV of other family members excluding the surveyed individual are ultimately selected as the instrumental variable. This is because the fixed effects of individuals that do not change over time were considered when controlling for endogeneity in the previous section, and the introduction of family-level variables as instrumental variables can further control for potential fixed effects at the family level. At the same time, the introduction of instrumental variables that exclude the surveyed individual’s TFFV can reduce the problem of simultaneous endogeneity between the endogenous variable and the instrumental variable in the first-stage regression of the two-stage regression. More importantly, the TFFV at the family level will inevitably affect every family member, including the surveyed individual, which satisfies the assumption of relevance. In terms of exogeneity, since the dependent variable selected in this article is the surveyed individual’s evaluation of government performance, the impact of TFFV at the family level on an individual’s evaluation of government performance must be realized by first affecting the individual themselves. This cannot bypass the surveyed individual and thus the surveyed individual’s TFFV are the only pathway of influence, indirectly indicating that there is no correlation between instrumental variables and disturbance terms, which satisfies the condition of exogeneity. Table 4 shows the results after introducing instrumental variables.

Models (4)–(8), when introducing instrumental variables, also exclude data that only appear in one period. Model (4) introduces instrumental variables based on Model (3). It can be observed that the absolute value of the coefficient of the core explanatory variable significantly increases, indicating that the effect of instrumental variables is significant. Furthermore, all instrumental variables in all models are full rank, and in the weak instrument test, the F-values exclude the null hypothesis that the average TFFV is a weak instrument. However, in the endogeneity test, except for Model (7), all other models show the presence of endogeneity. The results of Model (4) further illustrate that in the entire sample, TFFV have a significant impact on the evaluation of government work performance.

Heterogeneity analysis

Considering that TFFV in rural areas may differ significantly from those in urban areas, this article believes that it is necessary to analyze whether urban–rural differences will lead to different impacts of TFFV on grassroots government performance evaluation. Especially in rural China, clan connections and weaker mobility have led to the persistence of TFFV. Based on this consideration, it is necessary to analyze whether urban–rural differences will lead to different impacts of TFFV on grassroots government performance evaluation. Apart from urban–rural differences, Fukuyama (1995) believes that China is a low-trust country due to the influence of family power, and low trust means that trust is difficult to extend beyond the family. Traditional values play a key role in low trust, and the emergence of the Internet will further reduce the above trust (Zhao & Wang 2021). Considering the prevalence of “modern cynicism” in the Internet ecology, it is more likely to affect individuals’ judgment of government work. Therefore, this article will also consider whether the use of the Internet will affect the role of TFFV in government performance evaluation.

In Table 4, Model (5) introduces the interaction terms of TFFV, the Internet, and hukou to further understand the role of these two variables in TFFV on government performance evaluation. In Model (5), the influence of TFFV on government performance evaluation and its interaction with hukou is significant, but the interaction with the internet is not significant. Based on Model (5), in Model (6), the interaction term of the internet is removed for regression, and it can be found that the coefficients and significance of the main variables are enhanced. The use of the internet itself will indeed reduce the evaluation of grassroots government work. At the same time, through the information criterion (BIC), it can be found that Model (6) is a more effective model than Model (5). Based on the aforementioned analysis, Models (7) and (8) regress urban and rural samples, respectively. It is observed that in Model (7), the effect of TFFV on government work remains significant. Model (8) regresses on rural samples. Analysis of these two models reveals that the impact of TFFV is significantly stronger in rural areas of China, and although a reverse U-shaped pattern is present in both urban and rural areas, the sensitivity of TFFV’s impact on government performance evaluation is more pronounced in rural areas, specifically showing that the saturation point of TFFV occurs earlier in rural regions. The reason for the observed effect in urban areas could be attributed to the considerable proportion of the “first generation city dwellers” in China’s urbanized population, as mentioned previously. These individuals, despite residing in cities, are also deeply influenced by traditional values, but the influence may be weaker compared to rural areas due to the increasing numbers of “second generation” and “third generation city dwellers.” Since this paper has confirmed that the impact of TFFV is more pronounced in rural areas, and the essence of the influence originates from rural settings, the subsequent analysis will mainly focus on rural areas.

Mechanism analysis

The previous sections highlighted that in rural areas, the impact of TFFV on government work performance evaluation still exhibits an inverted U-shape. Based on this finding, this section’s mechanism analysis will primarily focus on the mechanisms through which TFFV influences government work performance evaluation in rural areas and the reasons for this inverted U-shape. To analyze the potential mechanisms on either side of this inverted U-shape, this paper will separately regress on either side of the inflection point, subsequently examining the differences in mechanisms. It was previously suggested that this difference may arise from the clash between clan culture and grassroots government over governance power. This is specifically manifested in the varying degrees of clan culture’s richness, leading to differences in public attitudes toward “rule by man.” TFFV, being a significant representation of clan culture and a constraint imposed on social interactors’ behavior within society, inevitably influences the value judgments of individuals. TFFV, being a fundamental attribute in the entire transmission mechanism, serves not only as the familial ethical foundation for Confucian political values but also influences government work performance evaluation, rather than the reverse.

Drawing on the inverted U-curve and the previously mentioned Confucian traditional political value of “rule by man,” this research identifies trust, particularly in people, as a crucial element in exploring how TFFV affect mechanisms of government evaluation. People, as vehicles of value transmission, are central to the inheritance of TFFV and the execution of grassroots government functions. Without people, these processes cannot proceed. This focus on people also mirrors the Confucian emphasis on interpersonal relationships, as indicated by “A gentleman takes joy in three things: seeking the company of the superior, finding companions among peers, and showing kindness to inferiors (Mencius 1984), emphasizing the importance of managing diverse interpersonal relationships. While fostering trust, this emphasis can also lead to issues, especially where clan culture is prevalent, potentially resulting in conflicts with grassroots governance, such as inefficiencies or corruption among government staff. The evaluation of government work by residents, essentially grading the performance of government staff, is inseparable from the influence of traditional Confucian thought. Accordingly, this paper selects indicators to measure trust and distrust in government officials as mediatory variables for mechanism analysis, showcasing the shift in the role of traditional political values as clan cultural influence deepens. The former reflects trust in government officials and adherence to traditional political values, signifying public endorsement of authority in contexts with minimal clan culture influence. The latter highlights distrust in government officials, indicating sensitivity to grassroots governance in areas with rich clan culture, revealing the vulnerability of traditional political values. Together, these aspects form the theoretical framework of this study.

To measure trust and distrust in government officials, this study utilizes indicators of social trust levels and perceptions of the severity of government corruption. The former is derived from Fei Xiaotong’s theory of China’s rural social structure, constructing indicators from perspectives of kinship and geographical relationships, selecting CFPS data on trust in family members, neighbors, and strangers to build a social trust variable. Social trust, as the most fundamental form of trust in rural Chinese society, not only reflects trust levels in private domains but also serves as a critical framework for understanding public perceptions of government and its officials. According to Fei Xiaotong’s analysis, social structure is viewed as an expanding circle of trust, encompassing the closest family members to the broader society. Therefore, social trust provides a foundation for understanding and measuring public trust levels in government officials, thus reflecting the overall trust in government officials’ behavior (Fei et al. 1992). The indicator for the perception of government corruption severity directly uses existing variables. For 2010, data from 2011 and 2012 were used for substitution, given that personal preferences do not change immediately, making this method of substitution reasonably valid. To further illustrate the robustness of the mediatory indicators used in this paper, especially trust in government officials, the study employs trust levels in cadres as a mediatory variable for robustness checks. Since this variable was not collected before 2014, the study utilizes panel data from rural areas for 2014–2018 for mechanism verification. Although not perfect, the large sample size allows for an effective examination of robustness.

Trust in government officials

Lv and Zhu (2015) emphasized in their research that traditional socio-cultural norms encourage people to maintain their recognition and reverence for authority. This aligns with the hierarchical characteristic of Confucian culture, and is also a manifestation of the Confucian concepts of “respecting the superior and belittling the inferior” and the consciousness of “valuing close kinship and honoring the esteemed.” Therefore, when considering the positive impact of TFFV on government work performance evaluation on the left side of the inflection point, this paper hypothesizes that the positive effect of appropriate TFFV on government performance evaluation is based on its deep-rooted respect and trust for governmental authority in traditional political values. Furthermore, this trust plays a dominant role at this stage, which is also the result when the influence of clan culture is minimal, leading to no contradictions between the two. Combined with the characteristics of “rule by man,” this paper believes that trust in government officials is the key pathway through which traditional culture impacts government work performance evaluation. At this time, the deeper the TFFV, the higher its influence on government work evaluation, with trust in government officials surpassing skepticism toward the government. The following Table 5 displays the test for this mechanism.

In Model (9), TFFV have a significant impact on trust in government officials. Furthermore, due to the endogeneity of trust in government officials, a preference for personal trust is introduced as an instrumental variable. The result shows that trust in government officials has a significant impact on government performance evaluation, indicating a pronounced indirect effect.

Corruption sensitivity

For the right side of the inflection point, at this time, TFFV are relatively high, indirectly reflecting a strong overall clan culture. The contest between informal organizations represented by clan power and formal organizations represented by grassroots governments manifests as traditional political values of respecting authority beginning to be challenged. Beyond the pivotal role of “ren” in Confucian culture, more attention should be paid to the concept of “rule by man.” Previous studies have already discovered that the emergence of corruption issues further reinforced the low trust in grassroots governments (Liu 2015). The main concern of corruption remains the governance by individuals, especially worries about corruption issues among government officials. Continuous media reports on corrupt public officials, combined with the prevalence of “modern cynicism,” further deepened the public’s sensitivity to corruption, especially in rural areas, which is worthy of attention (Song et al. 2016). At the same time, the reflection of “rule by man” as a traditional political value needs to be contemplated, such as Confucius pointing out that an official should “He who exercises government by means of his virtue may be compared to the north polar star, which keeps its place and all the stars turn towards it” (Confucius 1979), emphasizing the moral character officials should possess. In the essence of governance, Confucius further suggests that politicians should be incorruptible. Relative to the trust in government officials, sensitivity to corruption is a challenge to its establishment. The reason trust in government officials is no longer considered when TFFV are high is that a trustworthy grassroots government helps cultivate public trust and general trust, expanding the scope of farmers’ trust (Yu 2017). However, when TFFV are at a higher level, it may reflect a relatively thick clan culture, making sensitivity to corruption also potentially at a high level, leading to skepticism about the grassroots government and blockages in the original trust mechanism. This article later confirms this assertion through analysis, showing that trust is insignificant.

Models (10) found that the overall effect of TFFV on government work performance evaluation is not significant. However, the indirect effect of TFFV on government performance evaluation through sensitivity to government corruption is significant. This suggests that there may be a masking effect at this time, with further analysis to be conducted in the subsequent text (Hayes 2009; Shrout & Bolger 2002). Moreover, since the endogeneity test was not significant, the instrumental variable was not used in the third step of model (10).

Robustness tests

To examine the robustness of the impact of TFFV on government work evaluation, as well as the mechanism of trust in government officials mentioned previously, this section first regresses the binary variable of government work performance evaluation. The division is based on whether there is a certain achievement in government work performance evaluation, with 1 indicating the criterion is met and 0 otherwise. During the regression process, fixed effects and issues of model endogeneity are still considered. Additionally, samples from minority regions will be excluded from the data because TFFV represent typical Confucian cultural values, and their impact mechanism on grassroots government work performance evaluation cannot be separated from the influence of Confucian culture. Therefore, minority regions might be less affected and show less significant performance. Subsequently, this paper will also incorporate survey data from 2011, 2012, and 2015, 2019 to further test the robustness of the conclusions using a larger sample. Finally, in the robustness test of mechanisms, especially in examining the trust mechanism in government officials, this paper employs a substitute variable, specifically the level of trust in cadres only present in the 2014 and 2018 survey questionnaires, to represent trust in government officials and conduct a robustness test. Although it does not involve data from 2010, the substantial size of the data still lends certain persuasive power. Table 6 presents the results of the robustness test.

Model (11) is the binary regression result of the dependent variable, (12) is the data after excluding minority regions, and (13) is the results of regression on the larger rural sample. The above models all show that TFFV have a significant impact on grassroots government work performance evaluation in rural areas, which is consistent with the benchmark regression conclusion. This demonstrates that TFFV have an impact on grassroots government work performance evaluation. Model (14) reflects the results of the mechanism test, that is, using trust in cadres as an mediatory variable to study the mechanism of trust in government officials. Its results are consistent with those obtained using social trust as an mediatory variable, demonstrating the robustness of the aforementioned intermediary mechanism.

Discussion

Interpretation of empirical results

The results of the benchmark regression indicate that TFFV have a significant impact on grassroots government evaluation, and this effect follows an inverted U-shaped curve. Furthermore, this finding is robust. In the control variables section, for every 1% increase in family transfer income, the positive evaluation of the government by that family will increase by 5 × 10−5 units. Compared to this, the impact of the initial distribution of family per capita net income on government evaluation is smaller and less significant, indicating that income redistribution has a more crucial effect on grassroots government performance evaluation. This confirms Hypothesis 1: appropriate TFFV have a positive impact on government performance evaluation. However, when TFFV become too entrenched, it will lower the evaluation of government work. This serves as a reminder for governmental institutions to adopt appropriate attitudes when dealing with regions with varying levels of TFFV.

In further heterogeneous analysis, interactions between the internet, household registration, and TFFV were introduced. However, the interaction with the internet was not significant, even in rural areas, possibly due to “modern cynicism,” indicating that the internet did not produce the anticipated significant effect. Regarding urban–rural differences, it was proven that the impact of TFFV on grassroots government work performance evaluation is significant in both urban and rural areas, exhibiting an inverted U-shape in both cases. However, the level of significance and sensitivity to TFFV’s impact on government performance evaluation is stronger in rural areas, specifically, the saturation point for TFFV in rural areas appears earlier, for example, at 3.26 compared to 4.3 in urban areas. Considering the median values of TTFV and sample sizes in both areas, a higher proportion of respondents in rural areas are on the right side of the inverted U-curve, underscoring the importance of focusing on rural areas. The reason behind this phenomenon could be as previously stated, with TFFV originating in the agricultural era and being adapted to the small-scale farming economy. Coupled with the persistence of TFFV in rural areas, its impact is naturally more profound there. Although urban areas also show this impact, albeit weaker, it could be due to the first generation of city dwellers still being heavily influenced by rural culture. However, the emergence of the second and even third generation of city dwellers may weaken this influence. Given that a higher proportion of respondents in rural areas have their TFFV influencing government work in a steadily declining phase, it becomes crucial for the government, especially in rural work, to properly address traditional family values represented by TFFV.

In the mechanism of how rural TFFV affect grassroots government work performance evaluation, on the left side of the inverted U-curve, the total effect is 0.044, and the indirect effect through trust in government officials, representing the traditional political value of respecting authority, is 0.0134, accounting for 31% of the influence. This path indicates that trust in government officials is crucial when TFFV levels are low, with nearly one-third of the influence explainable through this pathway. The paper also tests the path of distrust in the government on the left side, but it is not significant, indicating that clan forces are weak at this time, not significantly impacting formal organization’s grassroots governance. Conversely, on the right side of the curve, when using the public’s sensitivity to corruption as a mediator variable to measure attitudes toward “rule by man” at this time, both the total effect and the direct effect are not significant. Although the total effect is not significant, robustness tests indeed indicate the existence of an inverted U-shape, and the reason for the aforementioned situation may be due to the presence of a masking effect, with the indirect effect being −0.023, showing that the indirect effect is significantly higher than on the left side. Therefore, the mechanism of sensitivity to corruption on the right side deserves more attention. This stronger impact is not only due to the conflict between clan forces and grassroots governance when clan culture is prevalent but also a manifestation of Confucian emphasis on “ren.” “Ren” emphasizes valuing, loving, and enriching the people, advocating for respect for public opinion and welfare. Although never fully realized in feudal dynacies, “the people are more important than the ruler” has become a lofty political ideal for feudal intellectuals and still resonates strongly today, further illustrating the endogenous nature of TFFV’s sensitivity to corruption. The paper also introduces regression on the trust pathway in government officials, but it is not significant, indicating that distrust in government officials at this time exceeds trust, meaning traditional political values of respecting authority are difficult to exert their influence.

Contributions and limitations

In terms of contributions, this paper innovatively explores the connection between TFFV and grassroots government governance. While existing literature has extensively examined the link between traditional culture and trust in central government (Chen 2017; Li 2016, 2022; Niu & Zhao 2018; Wu et al. 2020; Xi & Ratigan 2023; Zhai 2022), this study shifts focus to the impact of TFFV on grassroots government performance evaluation. This addresses a significant gap by underscoring the specific influence of cultural norms at the local level, where direct interaction with the public occurs. Furthermore, by associating TFFV with governance efficiency, this research diverges from traditional examinations of TFFV, which primarily investigate its demographic and societal implications (Kumar & Sinha 2020; Shen et al. 2021; Song et al. 2022). It delves into the underlying traditional family values behind TFFV and examines their role as an informal institution affecting formal governance systems, an aspect less explored in previous studies. The mechanism analysis, based on trust issues from both sides of the curve, not only clarifies the underlying reasons for TFFV’s impact on grassroots government work performance evaluation but also offers a new perspective for studying mechanisms behind the inverted U-curve. Methodologically, this paper integrates empirical methods into the investigation, moving beyond the qualitative approaches often employed in such research. Specifically, the use of instrumental variables in the study of mediating effects ensures the rigor and reliability of the research, serving as a model for future inquiries.

Despite efforts to present the impact of TFFV on grassroots government performance evaluation, the paper acknowledges several limitations. In the mechanism verification part, due to missing CFPS data from 2010, data from 2011 and 2012 were used for compensation. While this provides rich and significant results, it lacks the completeness of the baseline regression. Moreover, in the analysis, the paper selects TFFV, measured using a single indicator rather than as a latent construct to assess the underlying clan culture’s richness. Although some scholars have attempted this approach, it still cannot fully reflect the richness of clan culture, indicating certain limitations that need to be addressed in future research.

Conclusions and policy implications

This paper contemplates the special relationship between TFFV and grassroots governments. Through constructing a double-fixed effects model, it investigates the impact of TFFV on grassroots government evaluation. The study delves into the endogenous nature of TFFV as an informal institution and its connections with traditional family values, traditional political values, Confucian “rule by man” philosophy, and even clan culture, further exploring its mechanisms of action. Additionally, it analyzes potential heterogeneities that might affect the role of TFFV. The paper concludes that: (1) TFFV significantly impact grassroots government evaluation in a non-linear manner, likely varying with the degree of TFFV, confirmed through variable adjustments and data range modifications for robustness. (2) The influence of TFFV on grassroots government evaluation is rooted in the endogenous characteristics of informal institutions, unfolding in people’s attitudes toward “rule by man.” Positive effects are based on trust under “authority,” while negative effects arise from distrust under sensitivity to corruption, with these pathways not easily changeable nor ignorable. (3) The study finds regional differences in the impact of TFFV on grassroots governments, with a more significant effect in rural areas, though both are underpinned by strong traditional family values. Despite the prevalence of “modern cynicism,” TFFV’s role in grassroots government evaluation has not been significantly affected by the internet.

Based on the aforementioned conclusions, in the context of the implementation of China’s Rural Revitalization Strategy and the significant role played by grassroots government organizations, this paper presents the following insights: (1) in the process of grassroots governance, it is necessary to re-evaluate the impact of Chinese traditional family values, represented by TFFV, especially in rural areas where it should be a focal point of work. Integrating these values into the considerations for grassroots governance, in conjunction with the local traditional cultural intensity, can help improve the performance of grassroots government. (2) For areas with weaker TFFV or weaker clan culture, actively leveraging the public’s inherent trust in government officials to promote the effective implementation of relevant policies can reduce negotiation costs. In areas with strong traditional or clan cultures, such as more isolated mountainous rural areas, where traditional culture based on kinship and geographical relations is denser, more attention should be paid to the adverse effects of corruption on governance. Efforts to curb potential negative impacts suggest that anti-corruption efforts might be more effective in these regions. (3) The study highlights the role of government official trust as a mediating variable in the relationship between TFFV and government performance evaluation. Training government officials in public service awareness and community participation skills may help increase their credibility, thus positively affecting governance. (4) Although the study finds that the internet has not significantly affected the relationship between TFFV and government performance evaluation, the role of the internet in shaping public perception and values should not be overlooked. Policymakers should consider how to effectively use digital platforms to interact with the public, disseminate information about government initiatives, and counteract the potential impact of “modern cynicism” on public trust and governance perception. (5) In the context of implementing China’s Rural Revitalization Strategy, understanding and integrating TFFV along with the underlying traditional cultural values into rural grassroots governance practices may be one of the keys to achieving rural revitalization. (6) In fact, the findings of this study, especially regarding the attention to traditional cultural values, are not only significant in China but can also be extended to other developing countries with rich traditional cultures. For instance, practices in India have shown that government programs aimed at addressing caste issues have been effective in promoting regional development, yet current progress still requires a certain level of government intervention (Reddy et al. 2016). Particularly in Andhra Pradesh, India, the role of the government is crucial in driving development, whether in villages or peripheral areas (Reddy & Bantilan 2013). Therefore, how to enable the government to play a larger or more effective role in this process is a question worth exploring in depth. The discussion previously in this paper regarding trust and corruption issues in rural areas might offer a pathway to improve grassroots governance and enhance the effectiveness of government intervention. That is, by deepening the understanding and integration of traditional cultural values, new avenues for enhancing government efficacy can be opened.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in its Supplementary Information files. Due to data CFPS usage policies, the raw dataset is available only at https://doi.org/10.18170/DVN/45LCSO.

Notes

Peterson Institute for International Economics. (2012, September 12). Urbanization and Economic Growth in China. https://www.piie.com/blogs/china-economic-watch/urbanization-and-economic-growth-china.

References

Anh Vu T, Plimmer G, Berman E, Ha PN (2022) Performance management in the Vietnam public sector: the role of institution, traditional culture and leadership. Int J Public Adm 45(1):49–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2021.1903499

Breeman G, Termeer CJAM, Lieshout MV (2013) Decision making on mega stables: understanding and preventing citizens’ distrust. NJAS Wagening J Life Sci 66:39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2013.05.004

Cao J, Xu Y, Zhang C (2022) Clans and calamity: how social capital saved lives during China’s Great Famine. J Dev Econ 157:102865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2022.102865

Chen D (2017) Local distrust and regime support: sources and effects of political trust in China. Polit Res Q 70(2):314–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912917691360

Chen XW (2020) The core of China’s rural revitalization: exerting the functions of rural area. China Agric Econ Rev 12(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1108/caer-02-2019-0025

Chen YJ, Li P, Lu Y (2018) Career concerns and multitasking local bureaucrats: evidence of a target-based performance evaluation system in China. J Dev Econ 133:84–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2018.02.001

Confucius (1979) The analects (Lun yü). Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, New York

Das M, van Soest A (1999) A panel data model for subjective information on household income growth. J Econ Behav Organ 40(4):409–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2681(99)00062-1

Dong C (2005) Comparison of social trust system between China and the West. Study Explor 1:114–117. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-462X.2005.01.025

Dussauge M (2011) Tradition and public administration ‐ edited by Martin Painter and B. Guy Peters. Public Adm 89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2011.01992.x

Fei X, Hamilton GG, Wang Z (1992) From the soil, the foundations of Chinese society: a translation of Fei Xiaotong’s Xiangtu Zhongguo, with an introduction and epilogue. University of California Press, Berkeley

Fukuyama F (1995) Trust: the social virtues and the creation of prosperity. Free Press, New York

Galperin H, Arcidiacono M (2021) Employment and the gender digital divide in Latin America: a decomposition analysis. Telecommun Policy 45(7). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2021.102166

Greif A, Laitin DD (2004) A theory of endogenous institutional change. Am Polit Sci Rev 98(4):633–652. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055404041395

Greif A (2006) Institutions and the Path to the Modern Economy: Lessons from Medieval Trade. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Ham C-B (2004) The ironies of Confucianism. J Democr 15:93–107. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2004.0046

Hayes AF (2009) Beyond Baron and Kenny: statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun Monogr 76(4):408–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750903310360

Huang Q, Xu J, Wei Y (2018) Clan in transition: societal changes of villages in China from the perspective of water pollution. 10(1):150. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/10/1/150

Hyndman N, Liguori M (2016) Public sector reforms: changing contours on an NPM landscape. Financ Account Manag 32(1):5–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12078

Jamil B, Yaping S, Ud Din N, Nazneen S (2022) Do effective public governance and gender (in) equality matter for poverty? Econ Res Ekon Istraz 35(1):158–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2021.1889391

King AYC, Bond MH (1985) The Confucian paradigm of man. In: Tseng WS & Wu DYH (eds) Chinese culture and mental health: an overview. pp 29–45. Academic Press, Orlando

Korn EL, Graubard BI (1995) Examples of differing weighted and unweighted estimates from a sample survey. Am Stat 49:291–295

Kumar S, Sinha N (2020) Preventing more “Missing Girls”: a review of policies to tackle son preference. World Bank Res Obser 35(1):87–121. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkz002

Lee FLF (2022) Pandemic control and public evaluation of government performance in Hong Kong. Chin J Commun 15(2):284–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2022.2052132

Leng XM, Zhong M, Xu JL, Xie SH (2020) Falling into the second-generation decline? Evidence from the intergenerational differences in social identity of rural-urban migrants in China. Sage Open 10(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020939539

Li L (2016) Reassessing trust in the central government: evidence from five national surveys. China Q 225:100–121. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0305741015001629

Li L (2022) Decoding political trust in China: a machine learning analysis. China Q 249:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0305741021001077

Liao JH, Dessein B, Pennings G (2010) The ethical debate on donor insemination in China. Reprod Biomed Online 20(7):895–902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.01.014

Liu JHF, Yeh KH, Wu CW, Liu L, Yang YY (2015) The importance of gender and affect in the socialization of adolescents’ beliefs about benevolent authority: evidence from Chinese indigenous psychology. Asian J Soc Psychol 18(2):101–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12102

Liu W (2015) Policy change and reproduction of hierarchical government trust in China—analyze the political result of the abolition of agriculture taxes. Fudan J Soc Sci Ed 57(3):157–164. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.0257-0289.2015.03.019

Lv S, Zhu Z (2015) On the regional differences of public trust in Chinese central government: a two-level analysis of the China survey 2008. J Public Adm 8(02):125–145+182

Mazella DS (2007) The making of modern cynicism. University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville

Mencius (1984) Mencius/translated by D.C. Lau. Chinese University Press, Hong Kong

Munshi K, Rosenzweig MR (2008) The efficacy of parochial politics: caste, commitment, and competence in Indian local governments. NBER Working Paper No. w14335, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1267566

Niu G, Zhao G (2018) Identity and trust in government: a comparison of locals and migrants in urban China. Cities 83:54–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.06.008

North DC (1990) Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Osborne SPE (2009) The new public governance?: Emerging perspectives on the theory and practice of public governance, 1st edn. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203861684

Profeta P (2020) Gender equality and public policy: measuring progress in Europe. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Pye LW (1968). The spirit of Chinese politics: A psychocultural study of the authority crisis in political development. M.I.T. Press, Oxford

Qiu T, Luo B (2023) Clan networks, administrative intervention and villagers’ sense of security—evidence from 212 villages in 27 provinces. Econ Theory Bus Manag 2023(7):47–59. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-596X.2023.07.005

Reddy AA, Bantilan M (2013) Regional disparities in Andhra Pradesh, India. Local Econ 28(1):123–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094212463791

Reddy AA, Cherukuri R, Cadman T, Tada PR, Bhattarai M, Reddy A (2016) Rural transformation of a village in Telangana, a study of Dokur since 1970s. Int J Rural Manag 12:143–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973005216665944

Seo G, Koropeckyj-Cox T, Kim S (2022) Correlates of contemporary gender preference for children in South Korea. Popul Dev Rev 48(1):161–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12458

Shen Z, Brown DS, Zheng X, Yang HL (2021) Women’s off-farm work participation and son preference in rural China. Popul Res Policy Rev 41:899–928

Shrout P, Bolger N (2002) Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods 7:422–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422

Song R, Li S, Eklund L (2022) Can risk perception alter son preference? Evidence from gender-imbalanced rural China. J Dev Stud 58(12):2566–2582. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2022.2113064

Song YN, Wang MY, Lei XT (2016) Following the money: corruption, conflict, and the winners and losers of suburban land acquisition in China. Geogr Res 54(1):86–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12158

Tang C, Zhao Z (2023) Informal institution meets child development: clan culture and child labor in China. J Comp Econ 51(1):277–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2022.09.006

Tang M (2021) Addressing skewed sex ratio at birth in China: practices and challenges. China Popul Dev Stud 4(3):319–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42379-020-00075-1

Tu WM (1993) Confucian Traditions in East Asian Modernity: Exploring Moral Authority and Economic Power in Japan and the Four Mini-Dragons. Bulletin Am. Acad. Arts Sci 46(8):5–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/3824238

Villoria M, Van Ryzin GG, Lavena CF (2013) Social and political consequences of administrative corruption: a study of public perceptions in Spain. Public Adm Rev 73(1):85–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02613.x

Wang J, Zhao Q (2021) The pattern of difference sequence and its reproduction in the rural trust relationship. Lanzhou Acad J 11:149–160. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1005-3492.2021.11.012

Wei Z (2007) The influence of Confucian culture on the construction of China’s civil servant team. Jiang-huai Tribune 225(05):140–143

Wu J, Li Y, Song C (2020) Temporal dynamics of political trust in China: a cohort analysis. China Inf 34(1):109–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0920203x19852917

Wu XP, Fitzgerald R (2021) ‘Hidden in plain sight’: Expressing political criticism on Chinese social media. Discourse Stud 23(3):365–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445620916365

Wu C, Chen M, Zhou L, Liang X, Wang W (2020) Identifying the spatiotemporal patterns of traditional villages in China: a multiscale perspective. Land 9(11):449. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9110449

Xi JR, Ratigan K (2023) Treading through COVID-19: Can village leader-villager relations reinforce public trust toward the Chinese central government? J Chin Polit Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-023-09846-2

Xu K, Xia X (2023) The influence of farmers’ clan networks on their participation in living environment improvement during the time of transition in traditional rural China 13(5):1055. https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0472/13/5/1055

Ying W, Yiyin Y, Xiaojiang W, En C (2017) What determines “giving birth to a son”: the social transformation of how institution and culture affect women’s fertility choices. J Chin Sociol 4(1):9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40711-017-0057-2

Yu H (2017) On the change of Chinese Peasants’ Interpersonal Trust and its determinants: analysis of the data from five waves survey (2002-2015) in 40 villages of Jiangxi Province. J Huazhong Norm Univ Humanit Soc Sci 56(5):1–10. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-2456.2017.05.001

Zhai Y (2022) Government policy performance and central-local political trust in China. J Public Policy 42(4):782–801. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0143814x22000162

Zhai YD (2018) Traditional values and political trust in China. J Asian Afr Stud 53(3):350–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909616684860

Zhang C (2019) Family support or social support? The role of clan culture. J Popul Econ 32(2):529–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-018-0686-z

Zhang K, Zhang Z-Y, Liang Q-M (2017) An empirical analysis of the green paradox in China: from the perspective of fiscal decentralization. Energy Policy 103:203–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.01.023

Zhao J, Wang J (2021) Does internet use affect residents’ social trust? Analysis based on the data of China General Social Survey. Res Financ Econ Issues 2021(05):119–129. https://doi.org/10.19654/j.cnki.cjwtyj.2021.05.014

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chen Hu: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing—original draft preparation. Hongxiao Zhang: supervision, reviewing and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, C., Zhang, H. Traditional family fertility values and performance evaluation of grassroots governments: evidence from the China Family Panel Studies. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1577 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03677-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03677-z