Abstract

Previous studies have shown that a high prevalence of depression and anxiety is a key factor leading to a decrease in student satisfaction with university life. Therefore, this study used two waves of longitudinal data to investigate the longitudinal relationships among depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life among college students. We employed correlation analysis and cross-lagged models to analyze the correlation and cross-lagged relationships among depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life. The results indicate a significant negative correlation between depression and student satisfaction with university life. The cross-lagged models indicate that depression (Time 1) negatively predicts student satisfaction with university life (Time 2). Anxiety (Time 1) does not have a significant predictive effect on student satisfaction with university life (Time 2). Moreover, student satisfaction with university life negatively predicts both depression (Time 2) and anxiety (Time 2). Improving student satisfaction with university life has a significant impact on reducing levels of depression and anxiety among college students. The research results can provide valuable information for mental health professionals, school administrators, and policymakers, enabling them to take more targeted measures to reduce depression and anxiety symptoms among university students and enhance student satisfaction with university life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to a survey report by the World Health Organization (WHO), one out of every eight individuals worldwide suffers from mental health problems. Addressing mental health problems promptly is imperative. Depression and anxiety are the most common mental health problems (Ghahramani et al., 2023; Hall et al., 2023; Ten Have et al., 2023), with over 280 million people diagnosed with depression and 301 million people suffering from anxiety.

College students in the transitional stage of life are more likely to experience mental health problems such as depression and anxiety (Denovan & Macaskill, 2017; Basri et al., 2022; Ooi et al., 2022). Research from different countries shows that the number of students suffering from depression and anxiety is increasing (Grineski et al., 2024; Xiao et al., 2022). As crucial pillars for future economic and social development, depression and anxiety among university students severely affect their early adulthood development during their college years, disrupting their daily lives and leading to poor emotional experiences, academic performance, insomnia, dropping out, and even suicidal tendencies (Floyd et al., 2007; Buchanan, 2012; Deng & Zhang, 2023). Therefore, researching the predictive factors of depression and anxiety among university students is of significant practical importance for the prevention and intervention of their mental health.

School is an important place for students’ mental health development. Currently, due to the high prevalence of depression and anxiety, there has been a significant reduction in student satisfaction with university life (Renshaw & Cohen, 2014; Lukaschek et al., 2017). Student satisfaction with university life is also an important indicator of the physical and mental well-being of university students (Headey et al., 1993; Irie & Yokomitsu, 2019). It refers to students’ perceptions and evaluations of the overall campus environment during their university experience (Astin, 1997). A supportive and positive campus environment not only enhances university students’ satisfaction with university life but also benefits their psychological well-being (Tan et al., 2020; Wang & Liu, 2024). It helps students develop a positive self-perception, contributing to their overall success (Ahn & Davis, 2020). Additionally, for universities, student satisfaction with university life impacts the educational quality and reputation of the institution, which are closely related to overall university development (Elsharnouby, 2015). Focusing on student needs, establishing a positive campus environment, and using student satisfaction assessments to guide future research directions are fundamental factors for the success of institutions. (Kanwar & Sanjeeva, 2022). Therefore, studying the relationship between depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life not only helps universities maintain students’ psychological well-being but also contributes to the high-quality development of the institutions themselves.

Based on large-sample longitudinal data, this study employs a cross-lagged model to explore the longitudinal correlation among depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life. It provides research evidence in the context of Chinese education to reduce negative emotions such as depression and anxiety among university students and enhance their life satisfaction during their academic study period. This is highly important for maintaining the psychological well-being of Chinese university students and promoting the high-quality development of higher education in China.

This study is based on existing literature and proposes the following three contributions: First, this study is one of the few that explores the relationship between depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life among Chinese university students using large-sample longitudinal data. Second, this research innovatively uses a customer satisfaction model to explain the relationship between depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life. Third, the findings not only supplement the academic understanding of the complex relationship between anxiety and student satisfaction with university life but also deepen the understanding of the predictive relationships among depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life.

Literature review

The relationship between depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life

Depression is a mood disorder characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and a loss of interest or pleasure in most activities (Daros et al., 2021). Anxiety is an emotional state characterized by heightened worry in response to ambiguous or perceived threats. It is divided into state anxiety and trait anxiety (Leal et al., 2017; Shamir & Shamir Balderman, 2024). However, in this study, we adopt a unified conceptualization of anxiety and no longer distinguish between the two types. Both depression and anxiety significantly impact students’ perceptions of their own quality of life and well-being. Existing studies have shown a close relationship among depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life. Many scholars believe that depression and anxiety are negatively correlated with student satisfaction with university life (Paschali & Tsitsas, 2010; Hajduk et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2023b). The greater the levels of depression and anxiety are, the lower the evaluation of student satisfaction with university life. Low student satisfaction with university life can also have negative impacts on students’ well-being, with high levels of negativity being key symptoms of depression and indicative of anxiety (Garber & Weersing, 2010; King & dela Rosa, 2019). However, the relationship between anxiety and student satisfaction with university life has yielded contrasting conclusions in recent research. Some scholars argue that there is a strong negative correlation between student satisfaction with university life and anxiety, especially during the COVID-19 period, when students experience high levels of anxiety that lower their satisfaction with university life (Duong, 2021; Sahin & Tuna, 2022). On the other hand, Esteban’s research suggested a positive correlation between anxiety and student satisfaction with university life. Some students exhibit high levels of positive emotions and constructive thinking and display positive self-perception, interpersonal relationships, and life goals. These students can regulate the alertness emotions generated by anxiety through positive psychological functions (Esteban et al., 2022). Further investigation is needed to explore the negative correlation between anxiety and student satisfaction with university life. Additionally, factors such as age (Khesht-Masjedi et al., 2019), gender (Gigantesco et al., 2019), personality (Hong & Giannakopoulos, 1994), family status (Shao et al., 2020), and other factors can also affect the relationships among depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life. To date, there have been numerous studies on the relationships among depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life, but the findings have been contradictory, necessitating further research to better understand these conflicting findings and the relationships among depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life. Based on the aforementioned research, we propose Hypothesis I.

Hypothesis I: Depression and anxiety among college students are negatively correlated with their satisfaction with university life.

The predictive relationship of depression and anxiety on college satisfaction

Research on the longitudinal relationships among depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life is limited. Regarding the predictive relationship between depression and student satisfaction with university life, a cross-sectional study involving Malaysian university students revealed that depression negatively predicted student satisfaction with university life (Ooi et al., 2022). Studies conducted on Australian adults have shown that depression is a significant predictor of life satisfaction, with its influence even surpassing that of variables such as religious beliefs, psychological reactions, and age (Headey et al., 1993). When exploring the predictive relationship between anxiety and student satisfaction with university life, scholars believe that anxiety is an emotional consequence of persistent negative thoughts (LeDoux, 2000). Individuals with anxiety disorders tend to engage in negative persistent thinking, which negatively predicts life satisfaction (Skalski‐Bednarz et al., 2024). Research has shown that depression and anxiety are negative predictors of student satisfaction with university life (Almeida et al., 2021), with individuals experiencing depression and anxiety more likely to have issues with lower satisfaction with university life (Tang et al., 2023). This is because depression and anxiety can influence individuals’ attitudes and coping mechanisms, leading them to engage in self-blame, denial, and self-distraction behaviors, thereby triggering maladaptive emotional regulatory mechanisms. Particularly for lower-level students, the depressive and anxious emotions experienced upon entering university may have long-term effects on changes in student satisfaction with university life in the future (Denovan & Macaskill, 2017). However, some studies have shown that anxiety is not a significant predictor of student satisfaction with university life, indicating that anxious individuals may overcome their anxiety and still experience meaningful and satisfying experiences in their life (Oladipo et al., 2013). Similarly, a study focusing on teachers found that anxiety is not a statistically significant predictor of job satisfaction among teachers (Ferguson et al., 2012). The longitudinal relationship between anxiety and student satisfaction with university life remains worthy of discussion. Notably, external factors such as interpersonal relationships and parental and peer support play a moderating role in the longitudinal relationships among depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life (Liem et al., 2010; Ooi et al., 2022). Positive relationships and peer support can mitigate the impact of depression and anxiety on student satisfaction with university life. Based on previous research, we propose Hypothesis II.

Hypothesis II: Depression and anxiety among college students can negatively predict their satisfaction with university life.

The predictive relationship of college satisfaction on depression and anxiety

Some studies have also explored the predictive effect of student satisfaction with university life on depression and anxiety. Research from different countries has shown that in Jordanian university students, student satisfaction with university life is the best predictor of depressive symptoms (Zawawi & Hamaideh, 2009). A cross-sectional study involving South Korean university students revealed that increasing student life satisfaction can prevent depression (Seo et al., 2018). Additionally, through SEMs, scholars studying the mental health status of Peruvian university students during the pandemic found that satisfaction negatively predicts depression (Esteban et al., 2022). Previous research has already established that satisfaction with university life negatively predicts depression. This suggests that when students’ expectations do not align with reality at the college level, leading to lower student satisfaction with university life, students are more likely to adopt negative coping mechanisms in daily life, which may exacerbate the onset of depression. Thus, enhancing student satisfaction with university life is crucial for preventing depression. Despite the abundance of research on the predictive relationship between student satisfaction with university life and depression, only a few studies have examined the predictive relationship between student satisfaction with university life and anxiety. A cross-sectional study on the mental health of health science students showed that student satisfaction with university life strongly predicted depression and anxiety (Franzen et al., 2021). From a social psychological, behavioral, and cognitive perspective, students with low satisfaction with university life are more prone to negative thinking, which is the strongest predictor of anxiety (Mahmoud et al., 2015). Therefore, increasing satisfaction with university life to reduce negative thinking is vital in helping students manage anxiety. Based on previous research, we propose Hypothesis III.

Hypothesis III: College student satisfaction with university life can negatively predict depression and anxiety.

Theoretical framework and research objectives

Theoretical framework

The customer satisfaction model has been widely used in research on satisfaction with university life (Naidoo & Whitty, 2014; Calma & Dickson-Deane, 2020; Khatri & Duggal, 2022). With the complexity and marketization of higher education, students are not only learners but also consumers (Nixon et al., 2018), known as “students as consumers” or “students as customers” (Tight, 2013). The customer satisfaction model (Cardozo, 1965) is a theoretical model used to measure consumers’ satisfaction with products or services, emphasizing the difference between customer expectations and actual experiences, leading to changes in customer satisfaction with products or services. Indeed, relatively few studies have incorporated depression and anxiety into customer satisfaction models. During their university years, students are consumers of educational services, and under the influence of depression and anxiety, they may feel dissatisfied with their daily academic life. They may have lower satisfaction with the services provided by the school, such as the teaching environment, learning facilities, and faculty strength, as the actual learning experience does not meet their expectations. This results in lower satisfaction with university life, which, as a form of negative thinking, can further exacerbate the severity of depression and anxiety (Franzen et al., 2021; Mahmoud et al., 2015). This not only affects the mental and physical health of college students but also impacts the quality of higher education and hinders societal development. Therefore, studies on the relationships among depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life are urgently needed.

Research objectives

Although the literature has explored the relationships among depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life, there are still several research gaps. First, there is a lack of large-scale studies with Chinese college students as samples, leading to insufficient long-term investigations into the relationships among depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life among Chinese students. Second, most existing studies have utilized cross-sectional research designs, focusing solely on the relationships between variables within specific time frames, without adequately capturing the longitudinal dynamics of these variables. Additionally, research on the longitudinal relationships among these variables has mostly remained at the theoretical or conceptual level, with limited empirical studies examining these relationships. Third, although the customer satisfaction model has been widely applied in studies on student satisfaction with university life, there has been limited research incorporating depression and anxiety into the model to analyze satisfaction. Fourth, conflicting findings exist regarding the relationship between anxiety and student satisfaction with university life, necessitating a more systematic exploration of this relationship.

This study utilizes large-scale longitudinal survey data and employs a cross-lagged model to capture the dynamic changes in depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life over time. This study innovatively adopts the customer satisfaction model as the theoretical basis to further elucidate the underlying logic of the relationships among these variables (see Fig. 1). Compared to previous cross-sectional studies, employing a cross-lagged model to investigate the longitudinal relationships between variables is more persuasive and helps address the limitations of past research. To ensure the robustness of the research findings, gender, age, extroversion, and family social status are included as control variables based on the literature, enhancing the credibility of the results. This study not only enriches the literature on the longitudinal relationships among depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life but also contributes to understanding the sample characteristics in China. Moreover, it holds significance for shaping the healthy personality and social psychological development of college students, reducing the prevalence of mental health issues among students, enhancing student satisfaction with university life, optimizing student management practices, and improving the educational management system in higher education institutions.

Methods

Participants

This study selected Chinese college students as the research participants and used a self-report questionnaire for data collection. The data of a total of 2298 participants were collected at T1. Follow-up data were collected after one year, and 2070 participants were tracked at T2. The sample grade at T1 was junior, and the sample grade at T2 was senior. The age of the participants was 18–28 years (M = 21.550, SD = 0.895). We used the t test to test the key characteristic variables of the sample (gender, age, depression score, anxiety score, student satisfaction with university life score, etc.), and missing scores were identified as missing completely at random. Multiple studies using the same dataset have indicated high data reliability (Cao & Liu, 2024; Liu et al., 2024a; Liu et al., 2024b; Liu et al., 2024c; Liu et al., 2024d). All students voluntarily participated in this study and signed an informed consent form before the study.

Measures

Depression

Depression was measured using the DASS-42 scale, which contains 14 items (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). Each topic was evaluated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (“not applicable at all”) to 3 (“very applicable or most applicable”). The score was calculated by adding the scores of related items. Students evaluated the 14 questions according to their personal feelings. According to the definition of the DASS-42, a degree of depression between 0 and 9 points was rated as “normal”. A degree of depression between 10 and 13 points was considered mild, a degree of depression between 14 and 20 points was considered moderate, a degree of depression between 21 and 27 points was considered severe, and a degree of depression between 28 points was considered extremely severe. A high score indicates a high degree of depression. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha values of the depression scale at time 1 and time 2 were 0.9004 and 0.9141, respectively.

Anxiety

Anxiety was measured using the DASS-42 scale, which consists of 14 items (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). Each item was assessed on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (“not applicable at all”) to 3 (“extremely applicable” or “most applicable”). Students evaluated the 14 items based on their personal feelings. The anxiety score was primarily calculated by summing the scores of relevant items. According to the definition of the DASS-42, anxiety levels were categorized as follows: a score of 0–7 indicated “normal” anxiety, 8–9 indicated “mild” anxiety, 10–14 corresponded to “moderate” anxiety, 15–19 indicated “severe” anxiety, and a score of 20 or higher represented “extremely severe” anxiety. A higher score indicated a greater level of anxiety. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha values of the anxiety scale at time 1 and time 2 were 0.8477 and 0.8746, respectively.

Student satisfaction with university life

Satisfaction with university life was measured using 9 items, including “Teaching facilities,” “Teachers’ research capabilities,” “Teachers’ teaching abilities,” “Academic status in the country,” “Systematic nature of the courses,” “Usefulness of the courses,” “Extracurricular activities,” “Student-teacher relationships,” and “Learning atmosphere.” Each item was rated on a scale of 1 (“very poor”) to 10 (“excellent”). The scores for satisfaction with university life were primarily calculated by summing the scores of relevant items based on students’ perceptions. A higher score indicates greater satisfaction with university life. In this study, the Cronbach’s alphas for student satisfaction with the university life scale at time 1 and time 2 were 0.9234 and 0.9239, respectively.

Control variables

Extroversion refers to the assessment of individual personality traits and is measured by the following question: “Overall, do you consider yourself more introverted or extroverted? Please select a number from 1 to 9 in the following picture to represent the degree of your personality trait.” In this question, students rate their personality trait based on their self-perceived introversion or extroversion using a scale from 1 (introverted) to 9 (extroverted).

Family social status is the individual’s assessment of his or her family’s position in the social hierarchy. It is measured by the following question: “In our society, some people are in the upper social strata, and some are in the lower social strata. In which stratum do you think your family (referring to your parents, yourself, and your siblings) currently belongs?” This question is rated on a scale from 1 to 5, representing lower class, lower-middle class, middle class, upper-middle class, and upper class. Students rate their family’s social status based on their own assessment.

Data analysis

First, this study used Stata 15.0 to analyze the means, standard deviations, and correlations among the variables of depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction among Chinese university students. Subsequently, the cross-lagged panel model (CLPM) was constructed using Mplus 8.3 to further explore the cross-effects and predictive relationships among depression, academic self-efficacy, and academic performance of university students through the autoregressive model (M1), the leading model (M2), the outcome model (M3), the interaction model (M4), and the control model (M5). The specific design of the model is as follows (see Figs. 2 and 3). The comparative fit indices (CFI), Tucker‒Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean residual (SRMR) were used to evaluate the model fit. The critical values for CFI and TLI were greater than 0.90, RMSEA was less than 0.10, and SRMR was less than 0.10 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Importantly, due to the large sample size (N = 2298), the chi-square/degrees of freedom ratio was not applicable for assessing model fit.

Note: This study utilizes five models: M1 as an autoregressive model, M2 as a preceding model, and M3 as an outcome model. All paths from M1 to M3 are encompassed within M4, which is an interactive model. M5 is the control model that includes additional control variables such as gender, age, extroversion, and family social status.

Note: This study utilizes five models: M1 as an autoregressive model, M2 as a preceding model, and M3 as an outcome model. All paths from M1 to M3 are encompassed within M4, which is an interactive model. M5 is the control model that includes additional control variables such as gender, age, extroversion, and family social status.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

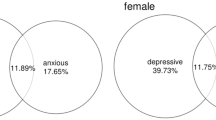

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistical variables, such as correlation, mean, and standard deviation, among depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction of Chinese university students. The correlation analysis results indicate that depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life are significantly correlated at different time points, suggesting a stable relationship among all variables. In terms of significance, depression was significantly negatively correlated with college life satisfaction within two years (p < 0.05), and anxiety at time 1 was significantly negatively correlated with student satisfaction with university life at time 1 (p < 0.05). There was no correlation between anxiety at time 2 and student satisfaction with university life at time 2 (p > 0.05). Within two years, depression and anxiety were significantly positively correlated (p < 0.05). According to Cohen’s guidelines, a correlation coefficient of r equal to 0.1 is considered a small effect size, 0.3 is considered a medium effect size, and 0.5 is considered a large effect size (Cohen, 1992). In the first year, depression at time 1 and student satisfaction with university life at time 1 had small effect sizes (r = −0.146), anxiety at time 1 and student satisfaction with university life at time 1 also had small effect sizes (r = −0.114), while depression and anxiety had large effect sizes (r = 0.684). In the second year, depression at time 2 and student satisfaction with university life at time 2 had small effect sizes (r = −0.088); anxiety at time 2 and student satisfaction with university life at time 2 also had small effect sizes (r = −0.030); and depression at time 2 and anxiety at time 2 had large effect sizes (r = 0.756). In t tests, we found significant differences in the mean scores of student satisfaction with university life at time 1 and time 2 (p < 0.05), with the mean score of student satisfaction with university life at time 2 (M = 63.673) being greater than that at time 1 (M = 61.270).

Cross-lagged relationship between depression and student satisfaction with university life

Table 2 presents the fit indices of the cross-lagged model between depression and student satisfaction with university life. First, an autoregressive model (M1) was established, and the model fit was good (CFI = 0.967, TLI = 0.956, RMSEA = 0.076, SRMR = 0.032), indicating that the variables were stable at both time points. Next, we added the cross-lagged path from depression (T1) to student satisfaction with university life (T2) based on M1 and created a preliminary model (M2) to examine the predictive effect of depression (T1) on student satisfaction with university life (T2). The model fit well (CFI = 0.967, TLI = 0.956, RMSEA = 0.076, SRMR = 0.026), and compared to M1, the difference was significant (∆χ2 = 8.755, p < 0.05), indicating that M2 had a better fit than M1. Then, we added the cross-lagged path from student satisfaction with university life (T1) to depression (T2) based on M1 and built the final model (M3) to test the predictive effect of student satisfaction with university life (T1) on depression (T2). The model fit well (CFI = 0.967, TLI = 0.956, RMSEA = 0.076, SRMR = 0.023), and compared to M1, the difference was significant (∆χ2 = 10.254, p < 0.05), indicating that M3 had a better fit than M1. Subsequently, an interaction model (M4) was constructed by incorporating both cross-lagged paths between depression and student satisfaction based on M1. The model fit well (CFI = 0.968, TLI = 0.955, RMSEA = 0.076, SRMR = 0.017), and the chi-square comparison suggested that compared to M1, the difference was significant (∆χ2 = 18.840, p < 0.05), indicating that M4 had a better fit than M1. This suggests a bidirectional relationship between depression and student satisfaction with university life among Chinese university students. Based on M4, we developed Model M5 by adding control variables such as gender, age, extroversion, and family social status (CFI = 0.964, TLI = 0.949, RMSEA = 0.063, SRMR = 0.017). Compared to M1, the fitting result of M5 was better (∆χ2 = 92.269, p < 0.05). M5 can further enhance the reliability and robustness of the research results.

The results in Table 3 indicate that the autoregressive paths of all five models are significant. In the prior model (M2), depression (T1) negatively predicts student satisfaction with university life (T2), with a value of \({\beta }_{DS}\) = −0.061, p = 0.003. According to the outcome model (M3), student satisfaction with university life (T1) negatively predicts depression (T2), with a value of \({\beta }_{SD}\) = −0.067, p = 0.001. In the interaction model (M4), the values are \({\beta }_{DS}\) = −0.060, p = 0.003 and \({\beta }_{SD}\) = −0.067, p = 0.001, consistent with the conclusions from M2 and M3, indicating that depression (T1) negatively predicts student satisfaction with university life (T2) and that student satisfaction with university life (T1) negatively predicts depression (T2). There is a bidirectional relationship between depression and student satisfaction with university life among Chinese university students. In M5, which includes control variables such as gender, age, extroversion, and family social status, the values are \({\beta }_{DS}\) = −0.064, p = 0.002 and \({\beta }_{SD}\) = −0.069, p = 0.001, respectively. These results confirm the previous conclusions, indicating a stable relationship between depression and satisfaction with university life.

Cross-lagged relationship between anxiety and student satisfaction with university life

Table 4 shows the fit indices of the cross-model between anxiety and student satisfaction with university life. First, an autoregressive model (M1) was established, and the model fit was good (CFI = 0.969, TLI = 0.959, RMSEA = 0.071, SRMR = 0.022), indicating that the variables were stable at both time points. Next, we added the cross-lagged path from anxiety (T1) to student satisfaction with university life (T2) based on M1 and established a preliminary model (M2) to test the predictive effect of anxiety (T1) on student satisfaction with university life (T2). The model fit well (CFI = 0.969, TLI = 0.958, RMSEA = 0.071, SRMR = 0.020), but compared to M1, the difference was not significant (∆χ2 = 1.041, p > 0.05), suggesting that M2 had a relatively poorer fit than M1. Then, we added the cross-lagged path from student satisfaction with university life (T1) to anxiety (T2) based on M1 and established the final model (M3) to test the predictive effect of student satisfaction with university life (T1) on anxiety (T2). The model fit well (CFI = 0.969, TLI = 0.958, RMSEA = 0.071, SRMR = 0.020), and compared to M1, the difference was significant (∆χ2 = 3.954, p < 0.05), indicating that M3 had a better fit than M1. Furthermore, an interaction model (M4) was established by adding both cross-lagged paths between anxiety and student satisfaction with university life based on M1. The model fit well (CFI = 0.969, TLI = 0.957, RMSEA = 0.072, SRMR = 0.017), but compared to M1, the difference was not significant (∆χ2 = 5.003, p > 0.05), suggesting that M4 had a relatively poorer fit than M1. Building on M4, we constructed Model M5 by adding control variables such as gender, age, extroversion, and family social status (CFI = 0.966, TLI = 0.951, RMSEA = 0.059, SRMR = 0.017). Compared to M1, the fitting result of M5 was better (∆χ2 = 94.501, p < 0.05). M5 can further enhance the reliability and robustness of the research results.

Table 5 indicates that the autoregressive paths of all five models are significant. In the prior model (M2), the predictive relationship between anxiety (T1) and student satisfaction with university life (T2) is not significant, with a value of \({\beta }_{AS}\) = −0.021, p = 0.307. In the outcome model (M3), student satisfaction with university life (T1) negatively predicts anxiety (T2), with a value of \({\beta }_{SA}\) = −0.042, p = 0.047. In the interaction model (M4), the values are \({\beta }_{AS}\) = −0.021, p = 0.306 and \({\beta }_{SA}\) = −0.042, p = 0.046, respectively, consistent with the conclusions from M3, indicating that student satisfaction with university life (T1) negatively predicts anxiety (T2). In M5, which includes control variables such as gender, age, extroversion status, and family social status, the values are \({\beta }_{AS}\)=−0.024, p = 0.266 and \({\beta }_{SA}\) = −0.046, p = 0.030, respectively. These results confirm the previous conclusions, demonstrating that the negative predictive relationship between student satisfaction with university life (T1) and anxiety (T2) remains robust even after accounting for these variables.

Discussion

This study focuses on Chinese university students as research subjects and investigates the longitudinal relationships among depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life during their third year (T1) and fourth year (T2) through a one-year follow-up survey using a dual-wave cross-lagged model.

First, this study used correlation analysis to reveal a negative relationship between depression and student satisfaction with university life among college students, which is consistent with previous research findings (Paschali & Tsitsas, 2010; Hajduk et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021). When students have lower levels of satisfaction with their university life, they are more likely to experience negative emotions. These negative emotions can hinder students’ perception of their surrounding environment, thus reducing their overall student satisfaction with university life. According to the study, we found that anxiety and student satisfaction with university life were significantly negatively correlated only during the junior year. For junior students, the causes of anxiety may be related to uncertainties about postgraduate studies and employment, as well as the pressure of peer competition (Peng et al., 2010; Posselt & Lipson, 2016), which are often closely related to factors such as students’ academic major, learning environment, and teaching quality (Sojkin et al., 2012; Alqurashi, 2019). When students are in high-paying employment fields, collaborative learning environments, and environments with high-quality teaching, where their expectations align with reality, their anxiety levels are lower, and their college life satisfaction is greater. However, in the senior year, there was no significant negative correlation between anxiety and student satisfaction with university life, which contradicts findings from most previous studies (Duong, 2021; Sahin & Tuna, 2022). This discrepancy may be due to the measurement methods used. Our study also revealed that senior students typically exhibit greater adaptability than junior students do, with their average satisfaction with university life levels being greater. This conclusion is consistent with the finding that students in higher grades generally report higher levels of student satisfaction with university life than do students in lower grades (El Ansari, 2002).

Second, this study utilized a cross-lagged model to analyze the longitudinal relationships among depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life. We found that depression among college students negatively predicts their satisfaction with university life; that is, lower levels of depression in the junior year correspond to higher levels of student satisfaction with university life in the senior year, while higher levels of depression in the junior year are associated with lower levels of student satisfaction with university life in the senior year, which is consistent with previous research findings (Tang et al., 2023; Ooi et al., 2022; Almeida et al., 2021; Denovan & Macaskill, 2017; Headey et al., 1993). When students experience depression, it can lead to poor emotional experiences, lower academic performance, and even negative behaviors such as dropping out or suicidal tendencies (Floyd et al., 2007; Buchanan, 2012; Deng & Zhang, 2023). According to the customer satisfaction model, for students, as consumers of services provided by universities, due to the series of negative behaviors and impacts caused by depression, students’ perceptions and assessments of daily academic life are reduced. This leads to their actual experiences of academic life falling short of their expectations, and this negative behavior typically has a certain degree of persistence, thereby decreasing students’ college life satisfaction in the next stage. However, anxiety does not significantly predict student satisfaction with university life, which aligns with some research results (Oladipo et al., 2013; Ferguson et al., 2012). This may be due to the measurement methods used in our study. For Chinese university students, depression may be a relatively more serious psychological issue that can alter students’ satisfaction with university life. On the other hand, anxiety might be a relatively milder psychological issue, as the current level of anxiety among university students does not reach a point where it significantly impacts their satisfaction with university life. This further underscores the importance of paying more attention to depressed college students as a vulnerable group in terms of mental health among university students. Providing them with more mental health resources to prevent and intervene in their depressive emotions is crucial. To alleviate the negative predictive relationship between depression and student satisfaction with university life, students should strive to cultivate a positive mindset, foster good interpersonal relationships, and maintain a healthy lifestyle (Hames et al., 2013; Seo et al., 2018; Cao, 2023; Cao et al., 2023) to reduce the negative effects of depression on their physical and mental well-being. University administrators and teachers should enhance communication and interaction with students, prioritize their mental health problems, and promptly offer intervention measures. This is essential for safeguarding students’ psychological well-being and ensuring the high-quality development of universities. Subsequent research will delve deeper into the pathways between high school students’ depression and anxiety and their impact on student satisfaction with university life to propose more effective intervention strategies.

Third, we found that student satisfaction with university life negatively predicts both depression and anxiety. Specifically, higher levels of student satisfaction in the junior year correspond to lower levels of depression and anxiety in the senior year, and vice versa. This is because university students are considered more susceptible to the external conditions of their current life circumstances, and student satisfaction with university life is often closely intertwined with the educational environment in which they are situated (Tan et al., 2020; Wang & Liu, 2024). Universities should not only provide a conducive campus environment to help students successfully obtain their degrees in a positive learning atmosphere but also assist them in achieving their academic goals and preparing for future careers (Calma & Dickson-Deane, 2020; Ahn & Davis, 2020). This can effectively enhance student satisfaction with university life and promote students’ psychological health and growth (Ahn & Davis, 2020). A low level of student satisfaction not only negatively impacts students’ psychological well-being but also may lead to the loss of talented students, damage the reputation of the institution, and hinder its long-term development. Universities should realize that students are not only “consumers” but also partners. Universities should prioritize increasing student engagement. Student involvement in higher education can enhance the development of the teaching and learning environment within institutions (Liu et al., 2023a; Howson & Weller, 2016). This relationship-building approach is essential for improving student satisfaction (Kandiko Howson & Matos, 2021) and reducing student mental health problems.

Limitations

This study is subject to five limitations. First, the measurements of depression, anxiety, student satisfaction with university life, extroversion, and family social status in this study rely on self-reported measures, thus potentially introducing measurement errors. Second, although the results of the correlation analysis indicate a significant negative correlation between depression and student satisfaction with university life, the effect size is small. Third, the college education level of the students may influence the outcomes. The sample of this study consisted of university students at higher grade levels, which may differ from the experiences encountered by students at lower grade levels. Fourth, the instrument used to measure student satisfaction was not previously validated and remains untested in terms of retest reliability or referenced in previously published literature. Fifth, the mean of measuring extroversion and social status did not involve validated instruments.

Implications for educational practice and conclusions

Implications for educational practice

This study provides preliminary evidence of the longitudinal relationships among depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life. This study offers theoretical support for further exploration of how psychological health education can help students better adapt to university life. It also provides new insights for the administrative departments of higher education institutions in terms of student development and education, with important guiding significance.

Given the important role of student satisfaction with university life in students’ mental health, schools should prioritize educational philosophies, curriculum design, teacher‒student relationships, and student support services. Strengthening humanistic and cultural construction and aligning student management with student development around the goal of cultivating high-level talent are essential. More humanized management and services should be provided. Schools should enhance teaching reforms, improve teaching quality, increase the societal recognition of universities, and enhance students’ recognition of self-worth to improve student satisfaction with university life and reduce levels of depression and anxiety. Additionally, schools should pay attention to the psychological health of university students, especially those who are already experiencing depression and anxiety, and take timely and effective measures for intervention and treatment to prevent these negative emotions from impacting their academics and lives.

On the one hand, educators need to pay attention to students’ emotional states and identify and address potential psychological issues in a timely manner. On the other hand, they should provide appropriate support and counseling to help students establish healthy psychological defense mechanisms and enhance psychological resilience.

Although this study focused on the relationships among depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life among Chinese college students, future research could broaden the scope to include students from other countries and regions. This study contributes to exploring the relationship between college students’ psychological health and student satisfaction in cross-cultural contexts and provides a theoretical basis for international education practices. Future research should continue to make efforts to overcome the limitations of existing studies and further explore the complex relationships among these variables. Through these studies, we can better understand the impact of students’ life experiences in college on their mental health, thereby providing targeted support and services for colleges.

Conclusions

First, there is a negative correlation between depression and student satisfaction with university life among college students, whereas no such negative correlation is observed between anxiety and student satisfaction with university life.

Second, depression among college students is found to have a negative predictive influence on student satisfaction with university life, while anxiety does not have a significant prospective impact on student satisfaction with university life.

Third, student satisfaction with university life is negatively predictive of both anxiety and depression.

Data availability

The data ownership belongs to the National Survey Research Center, Renmin University of China. Since the dataset has not been publicly released, the authors only obtained the right to use the dataset and do not have the authority to publicly distribute it. Therefore, a download link for the dataset cannot be provided. However, descriptive statistical analysis results regarding this dataset have been published in the appendix of the author’s previously published paper. You can refer to the following paper for more information: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02252-2. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ahn MY, Davis HH (2020) Four domains of students’ sense of belonging to university. Stud High Educ 45(3):622–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1564902

Almeida D, Monteiro D, Rodrigues F (2021) Satisfaction with life: mediating role in the relationship between depressive symptoms and coping mechanisms. Healthcare 9(7):787. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9070787

Alqurashi E (2019) Predicting student satisfaction and perceived learning within online learning environments. Distance Educ 40(1):133–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2018.1553562

Astin AW (1997) What matters in college? : Four critical years revisited. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Basri T, Radhakrishnan K, Rolin D (2022) Barriers to and facilitators of mental health help-seeking behaviors among South Asian American college students. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment health Serv 60(7):32–38. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20211215-01

Buchanan JL (2012) Prevention of depression in the college student population: a review of the literature. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 26(1):21–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2011.03.003

Calma A, Dickson-Deane C (2020) The student as customer and quality in higher education. Int J Educ Manag 34(8):1221–1235. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-03-2019-0093

Cao X (2023) Sleep Time and Depression Symptoms as Predictors of Cognitive Development Among Adolescents: A Cross-Lagged Study From China. Psychological Reports. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941231175833

Cao X, Liu X (2024) Self-esteem as a predictor of anxiety and academic self-efficacy among Chinese university students: a cross-lagged analysis. Curr Psychol 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05781-4

Cao X, Zhang Q, Liu X (2023) Cross-Lagged Relationship between Physical Activity Time, Openness and Depression Symptoms among Adolescents: Evidence from China. Int J Ment Health Promot 25(9). https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2023.029365

Cardozo RN (1965) An experimental study of customer effort, expectation, and satisfaction. J Mark Res 2(3):244–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224376500200303

Cohen J (1992) A power primer. Psychol Bull 112(1):155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

Daros AR, Haefner SA, Asadi S, Kazi S, Rodak T, Quilty LC (2021) A meta-analysis of emotional regulation outcomes in psychological interventions for youth with depression and anxiety. Nat Hum Behav 5(10):1443–1457. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01191-9

Deng X, Zhang H (2023) Mental health status among non-medical college students returning to school during the COVID-19 pandemic in Zhanjiang city: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychol 13:1035458. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1035458

Denovan A, Macaskill A (2017) Stress and subjective well-being among first year UK undergraduate students. J Happiness Stud 18:505–525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9736-y

Duong CD (2021) The impact of fear and anxiety of Covid-19 on life satisfaction: psychological distress and sleep disturbance as mediators. Personal Individ Diff 178:110869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110869

El Ansari W (2002) Student nurse satisfaction levels with their courses: part I–effects of demographic variables. Nurse Educ Today 22(2):159–170. https://doi.org/10.1054/nedt.2001.0682

Elsharnouby TH (2015) Student co-creation behavior in higher education: The role of satisfaction with the university experience. J Mark High Educ 25(2):238–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2015.1059919

Esteban RFC, Mamani-Benito O, Morales-García WC, Caycho-Rodríguez T, Mamani PGR (2022) Academic self-efficacy, self-esteem, satisfaction with studies, and virtual media use as depression and emotional exhaustion predictors among college students during COVID-19. Heliyon, 8(11). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11085

Ferguson K, Frost L, Hall D (2012) Predicting teacher anxiety, depression, and job satisfaction. J Teach Learn 8(1). https://doi.org/10.22329/jtl.v8i1.2896

Floyd P, Mimms S, Yelding C (2007) Personal health: Perspectives and lifestyles. Cengage learning, Farmington Hills

Franzen J, Jermann F, Ghisletta P, Rudaz S, Bondolfi G, Tran NT (2021) Psychological distress and well-being among students of health disciplines: the importance of academic satisfaction. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(4):2151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042151

Garber J, Weersing VR (2010) Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in youth: implications for treatment and prevention. Clin Psychol 17(4):293. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2010.01221.x

Ghahramani S, Kasraei H, Hayati R, Tabrizi R, Marzaleh MA (2023) Health care workers’ mental health in the face of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 27(2):208–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13651501.2022.2101927

Gigantesco A, Fagnani C, Toccaceli V, Lucidi F, Violani C, Picardi A (2019) The relationship between satisfaction with life and depression symptoms by gender. Front Psychiatry 10:460236. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00419

Grineski SE, Morales DX, Collins TW, Nadybal S, Trego S (2024) Anxiety and depression among US college students engaging in undergraduate research during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Health 72(1):20–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2021.2013237

Hajduk M, Heretik Jr A, Vaseckova B, Forgacova L, Pecenak J (2019) Prevalence and correlations of depression and anxiety among Slovak college students. Bratisl Lekarske Listy 120(9):695–698. https://doi.org/10.4149/BLL_2019_117

Hall BJ, Li G, Chen W, Shelley D, Tang W (2023) Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation during the Shanghai 2022 Lockdown: a cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord 330:283–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.02.121

Hames JL, Hagan CR, Joiner TE (2013) Interpersonal processes in depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 9:355–377. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185553

Headey B, Kelley J, Wearing A (1993) Dimensions of mental health: life satisfaction, positive affect, anxiety and depression. Soc Indic Res 29:63–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01136197

Hong S-M, Giannakopoulos E (1994) The relationship of satisfaction with life to personality characteristics. J Psychol 128(5):547–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1994.9914912

Howson CK, Weller S (2016) Defining pedagogic expertise: students and new lecturers as co-developers in learning and teaching. Teach Learn Inq 4(2):50–63. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.4.2.6

Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model 6(1):1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Irie T, Yokomitsu K (2019) Relationship between dispositional mindfulness and living condition and the well-being of first-year university students in Japan. Front Psychol 10:489191. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02831

Kandiko Howson C, Matos F (2021) Student surveys: measuring the relationship between satisfaction and engagement. Educ Sci 11(6):297. https://doi.org/10.3390/EDUCSCI11060297

Kanwar A, Sanjeeva M (2022) Student satisfaction survey: a key for quality improvement in the higher education institution. J Innov Entrep 11(1):27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-022-00196-6

Khatri P, Duggal HK (2022) Well‐being of higher education consumers: a review and research agenda. Int J Consum Stud 46(5):1564–1593. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12783

Khesht-Masjedi MF, Shokrgozar S, Abdollahi E, Habibi B, Asghari T, Ofoghi RS, Pazhooman S (2019) The relationship between gender, age, anxiety, depression, and academic achievement among teenagers. J Fam Med Prim Care 8(3):799–804. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_103_18

King RB, dela Rosa ED (2019) Are your emotions under your control or not? Implicit theories of emotion predict well-being via cognitive reappraisal. Personal Individ Diff 138:177–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.09.040

Leal PC, Goes TC, da Silva LCF, Teixeira-Silva F (2017) Trait vs. state anxiety in different threatening situations. Trends Psychiatry Psychother 39(3):147–157. https://doi.org/10.1590/2237-6089-2016-0044

LeDoux JE (2000) Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu Rev Neurosci 23:155–184. https://doi.org/10.1146/ANNUREV.NEURO.23.1.155

Li X, Shek DT, Shek EY (2021) Psychological morbidity among university students in Hong Kong (2014–2018): Psychometric properties of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) and related correlates. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(16):8305. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168305

Liem JH, Lustig K, Dillon C (2010) Depressive symptoms and life satisfaction among emerging adults: a comparison of high school dropouts and graduates. J Adult Dev 17:33–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-009-9076-9

Liu X, Ji X, Zhang Y (2024a) More romantic or more realistic: trajectories and influencing factors of romantic love among Chinese college students from entering college to graduation. Human Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03107-0

Liu X, Li Y, Cao X (2024b) Bidirectional reduction effects of perceived stress and general self-efficacy among college students: a cross-lagged study. Human Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02785-0

Liu X, Yuan Y, Gao W, Luo Y (2024c) Longitudinal trajectories of self-esteem, related predictors, and impact on depression among students over a four-year period at college in China. Human Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03136-9

Liu, X, Zhang, Y, & Cao, X (2023a). Achievement goal orientations in college students: longitudinal trajectories, related factors, and effects on academic performance. Eur J Psychol Educ 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00764-8

Liu X, Zhang Y, Cao X, Gao W (2024d) Does anxiety consistently affect the achievement goals of college students? A four-wave longitudinal investigation from China. Curr Psychol 43(12):10495–10508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05184-x

Liu X, Zhang Y, Gao W, Cao X (2023b) Developmental trajectories of depression, anxiety, and stress among college students: a piecewise growth mixture model analysis. Human Soc Sci Commun 10(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02252-2

Lovibond, SH, Lovibond PF (1995) Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales (2nd. Ed.). Sydney Psychology Foundation

Lukaschek K, Vanajan A, Johar H, Weiland N, Ladwig KH (2017) In the mood for ageing”: determinants of subjective well-being in older men and women of the population-based KORA-Age study. BMC Geriatrics 17:126. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0513-5

Mahmoud JS, Staten RT, Lennie TA, Hall LA (2015) The relationships of coping, negative thinking, life satisfaction, social support, and selected demographics with anxiety of young adult college students. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs 28(2):97–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcap.12109

Naidoo R, Whitty G (2014) Students as consumers: commodifying or democratising learning? Int J Chin Educ 2(2):212–240. https://doi.org/10.1163/22125868-12340022

Nixon E, Scullion R, Hearn R (2018) Her majesty the student: marketised higher education and the narcissistic (dis) satisfactions of the student-consumer. Stud High Educ 43(6):927–943. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1196353

Oladipo SE, Adenaike FA, Adejumo AO, Ojewumi KO (2013) Psychological predictors of life satisfaction among undergraduates. Proc Soc Behav Sci 82:292–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.263

Ooi PB, Khor KS, Tan CC, Ong DLT (2022) Depression, anxiety, stress, and satisfaction with life: Moderating role of interpersonal needs among university students. Front Public Health 10:958884. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.958884

Paschali A, Tsitsas G (2010) Stress and life satisfaction among university students-a pilot study. Ann Gen Psychiatry 9(Suppl 1):S96. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-859X-9-S1-S96

Peng M, Hu G, Dong J, Zhang L, Liu B, Sun Z (2010) Employment-related anxiety and depression in senior college students in China. J Cent South Univ Med Sci 35(3):194–202. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-7347.2010.03.002

Posselt JR, Lipson SK (2016) Competition, anxiety, and depression in the college classroom: variations by student identity and field of study. J Coll Stud Dev 57(8):973–989. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2016.0094

Renshaw TL, Cohen AS (2014) Life satisfaction as a distinguishing indicator of college student functioning: further validation of the two-continua model of mental health. Soc Indic Res 117:319–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0342-7

Sahin S, Tuna R (2022) The effect of anxiety on thriving levels of university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Collegian 29(3):263–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2021.10.004

Seo EH, Kim S-G, Kim SH, Kim JH, Park JH, Yoon H-J (2018) Life satisfaction and happiness associated with depressive symptoms among university students: a cross-sectional study in Korea. Ann Gen Psychiatry 17:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-018-0223-1

Shamir M, Shamir Balderman O (2024) Attitudes and feelings among married mothers and single mothers by choice during the Covid-19 crisis. J Fam Issues 45(3):720–743. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X231155661

Shao R, He P, Ling B, Tan L, Xu L, Hou Y, Kong L, Yang Y (2020) Prevalence of depression and anxiety and correlations between depression, anxiety, family functioning, social support and coping styles among Chinese medical students. BMC Psychol 8:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00402-8

Skalski‐Bednarz SB, Konaszewski K, Toussaint LL, Harder JP, Hillert A, Surzykiewicz J (2024) The mediating effects of anxiety on the relationships between persistent thinking and life satisfaction: a two‐wave longitudinal study in patients with anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychol 80(1):198–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23602

Sojkin B, Bartkowiak P, Skuza A (2012) Determinants of higher education choices and student satisfaction: the case of Poland. High Educ 63:565–581. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9459-2

Tan EJ, Meyer D, Neill E, Phillipou A, Toh WL, Van Rheenen TE, Rossell SL (2020) Considerations for assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in Australia. Aust NZ J psychiatry 54(11):1067–1071. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867420947815

Tang Q, He X, Zhang L, Liu X, Tao Y, Liu G (2023) Effects of neuroticism on differences in symptom structure of life satisfaction and depression-anxiety among college students: a network analysis. Behav Sci 13(8):641. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080641

Ten Have M, Tuithof M, van Dorsselaer S, Schouten F, Luik AI, de Graaf R (2023) Prevalence and trends of common mental disorders from 2007‐2009 to 2019‐2022: results from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Studies (NEMESIS), including comparison of prevalence rates before vs. during the COVID‐19 pandemic. World Psychiatry 22(2):275–285. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.21087

Tight M (2013) Students: customers, clients or pawns? High Educ Policy 26:291–307. https://doi.org/10.1057/hep.2013.2

Wang JX, Liu XQ (2024) Climate change, ambient air pollution, and students’ mental health. World J Psychiatry 14(2):204. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i2.204

Xiao P, Chen L, Dong X, Zhao Z, Yu J, Wang D, Li W (2022) Anxiety, depression, and satisfaction with life among college students in China: nine months after initiation of the outbreak of COVID-19. Front Psychiatry 12:777190. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.777190

Zawawi JA, Hamaideh SH (2009) Depressive symptoms and their correlates with locus of control and satisfaction with life among Jordanian college students. Eur J Psychol 5(4):71-103. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v5i4.241

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XL designed the study and wrote the protocol. XL and JW undertook the statistical analysis. XL and JW wrote the first draft of the paper and managed the literature analyses. XL polished the full text. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was acquired from the Ethics Committee of Tianjin University (ethical approval number: TJUE-2022-188; name of approval committee: Ethics Committee of Tianjin University).

Informed consent

Before filling out the questionnaire, informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Wang, J. Depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life among college students: a cross-lagged study. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1172 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03686-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03686-y

This article is cited by

-

The association between cultural engagement and mental health in Chinese higher vocational students: a cross-sectional study

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Connection between college students’ sports activities, depression, and anxiety: the mediating role of self-esteem

BMC Psychology (2025)

-

The effect of physical activity on anxiety through sleep quality among Chinese high school students: evidence from cross-sectional study and longitudinal study

BMC Psychiatry (2025)

-

Negative life events, sleep quality and depression in university students

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Symptom scale for anxiety and depression disorders (ESTAD): psychometric properties and sociodemographic profile in Peruvian university students

BMC Psychology (2024)