Abstract

Intergenerational relationships that highlight learning characteristics are created in interpersonal conflicts and lifelong education. Realizing the high-quality development of intergenerational learning has become a key problem. A primary school in eastern China united communities and families to create an efficient intergenerational learning project. This study aims to explore how this intergenerational learning is created. A principal, a teacher, two community educators, and five family members were recruited as the unstructured interview participants to collect data. This study finds that the school, community, and families play irreplaceable roles in creating intergenerational learning. Influenced by educational policies and education responsibilities, the school proactively designed the intergenerational learning project that takes grandparents to school in interaction with the community and families. Adhering to the principle of social services and age-friendly, the community provides sufficient educational resources for implementing intergenerational learning through collaborative support. Considering the generation gap and integration between grandparents and grandchildren, families as participating identities make intergenerational learning from possible imagination into real practice. This study highlights the theoretical framework of how intergenerational learning is created in school-community-family collaboration. The practical implications for optimizing intergenerational relationships and coping with population aging are further emphasized.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Studies have shown that population aging has caused a series of negative effects, such as increased government financial burden (Miyamoto and Yoshino 2022), unbalanced labor market structure (Temple and McDonald 2017), contradiction between supply and demand of educational resources (Kotschy and Sunde 2018) and complex conflicts in intergenerational relationships (Hess et al. 2016). Pursuing positive, healthy, and successful aging (Estebsari et al. 2020; Foster and Walker 2015; Teater and Chonody 2020) and promoting social harmony and intergenerational justice (Portacolone 2015) have become important expectations and directions for human civilization development. In addition to supporting physical health (Luo et al. 2020; Su et al. 2014) and encouraging social participation (Wanchai and Phrompayak 2019; Yang et al. 2021), education and learning for older adults is considered one of the most effective approaches to move towards active, healthy, and successful aging (Boulton-Lewis 2010; Jerman and Blažič 2020). It is necessary to emphasize that intergenerational learning as a reciprocal process promotes children’s growth in acquiring knowledge, enhancing skills, developing socio-emotional competencies, and integrating intergenerational relationships. In particular, intergenerational learning has become a new mode of innovating and developing education for older adults, young people, and children because of its remarkable advantages in eliminating age discrimination and promoting harmonious intergenerational relationships (Lee et al. 2020).

However, previous studies have shown that although intergenerational learning is considered to have a unique value in theoretical construction, it has many explicit and implicit dilemmas in dynamic, complex, and cross-cultural practice (Chineka and Yasukawa 2020). For example, intergenerational learning projects are not successfully implemented because older adults and youngsters do not have appropriate or consistent learning time. For another example, intergenerational learning service institutions do not always provide adequate funding, high-quality teachers, and other educational resources, thus not supporting older adults and youngsters’ common and differentiated learning expectations (Boström 2004). In addition, studies have emphasized that cognitive degradation and digital fear exhibited by older adults in interacting with youngsters have a more significant negative impact on the effectiveness of intergenerational learning (Passey 2014). Moreover, the informal and non-institutionalized model makes it difficult to effectively ensure the sustainable and orderly development of intergenerational learning (Stephan, 2021; Yembuu, 2021). Based on these dilemmas of intergenerational learning in complex, dynamic, and cross-cultural practices, policymakers, theoretical researchers, and practical explorers with similar or different stances, have unanimously and continuously expressed their expectations on how to realize the high-quality development of intergenerational learning practices.

Along with the strong trend of globalized education, the intergenerational learning model that originated in Europe and the United States has been continuously imitated and possibly innovated by China under the increasingly serious aging population and the high learning demand for the older adults (Keyi et al. 2020). As one of the countries with a strong ‘family culture’, relying on blood relationships has become the core feature of intergenerational learning in China (Yuan and Wu 2021). Therefore, studies directly describe and define the co-learning and mutual education of grandparents and grandchildren in Chinese as ‘family intergenerational learning’ (Cheng et al. 2021). It should also be emphasized that intergenerational learning in China has begun to develop from family to community and school in complex and dynamic relationships between intergenerational relationships, school-community-family collaboration, and age-friendly communities. The ‘taking grandparents to school’ project, launched by a primary school in eastern China with the community and families, is a typical innovative practice of intergenerational learning in China. Moreover, the success and efficiency of this intergenerational learning practice have been highly recognized and endorsed by multiple subjects, including grandparents, grandchildren, parents, and primary school teachers. As mentioned above, how to optimize and create the practice of intergenerational learning has become a common expectation among policymakers, theorists, and practitioners. Therefore, this research question aims to reveal the practical mechanisms of how intergenerational learning is created by school-community-family collaboration. It also needs to be made clear that the value of this study not only attempts to construct a theoretical model of intergenerational learning in the context of school-community-family collaboration but also contributes to spreading practical experiences of intergenerational learning. Furthermore, this study also provides scientific evidence for the government to formulate and promulgate policies related to school-community-family collaboration, intergenerational learning, and education for older adults.

According to the reality dilemma of population aging and intergenerational relationships, this study first raises the research question of how school, community, and family collaborate effectively to create an intergenerational learning project. This study then highlights research gaps in a critical review of the previous literature about school-community-family collaboration, intergenerational relationships, and age-friendly society. Field study sites, ethical principles, interview methods, data collection, analysis, reliability, and validity are described in the methodology. School-community-family collaborations to create practical mechanisms for intergenerational learning were constructed in the findings with the support of interview data. The theoretical model, practical implications, and policy significance of the intergenerational learning of taking grandparents to school are discussed. Finally, I explained the research limitations and imagined the future research direction.

Literature review

As society changes, a generation gap between the older and younger generations is difficult to ignore and reconcile due to conflicts and contradictions in knowledge, skills, psychology, and values (Hosseini et al. 2022; Wu, 2022). Age prejudice, behavioral discrimination, language conflict, and emotional confrontation were considered to be direct and distinctive reflections of these generation gaps (Clark, 2009; Elena-Bucea et al. 2021). This was interpreted by Margaret Mead, a representative scholar of the generation gap, as a conceptual framework of prefigurative culture and figurative culture (Mead 1940). How to eliminate generation gaps as much as possible has undoubtedly become an important challenge for researchers and practitioners. Democracy, equality, communication, and dialogue have been emphasized as concepts and practices to bridge the generation gap (Al-Lawati 2019; Taneja et al. 2018). Intergenerational learning as a concept and practice advocated has provided learning support to promote the relationship between older adults and younger from conflict to harmony (Andreoletti and Howard 2018; Stephan 2021). However, these studies emphasized the effectiveness of intergenerational learning in mitigating intergenerational conflict and facilitating intergenerational integration and failed to reveal how intergenerational learning practices are created. In addition to recognizing and understanding the aforementioned value of intergenerational learning, this study focuses on revealing the complex and dynamic process of intergenerational learning from concept to practice.

Numerous studies confirmed that school, together with family and community, constitutes an important educational field, that has a unique and distinctive impact on students’ growth and development (Epstein and Sheldon 2019; Ross et al. 2021; Wright and Smith 1998). With the demand and expectation of human beings for high-quality education, school-community-family collaboration has become an important component of the modern education system in the process of evolution from informal to institutionalized (Bæck 2010). In general, the purpose of school-community-family collaboration as policy, theory, and practice is to enhance students’ core literacy or twenty-first-century competencies. It can be said that the growth and development of students are considered the core principle or even the ultimate goal of school-community-family collaboration (Alston-Abel and Berninger 2018; Yuen 2011). However, driven and guided by lifelong education and intergenerational conflict, theorists have constantly criticized the fact that students’ growth is highly valued while parents and teachers are ignored in school-community-family collaboration (Moestue and Huttly 2008; Stacer and Perrucci 2013). In other words, everyone should be embedded in the school-community-family collaboration as a learner and become a subjective participant in the educational community. However, due to insufficient educational resources and limited professional development, parents, teachers, and community educators tend to focus on collaborative goals, content, and outcomes toward children’s growth when faced with extremely complex, risky, and uncertain practices (Baquedano-López et al. 2013; Schneider and Arnot 2018). Therefore, to make up for this research gap between the theory and practice of school-community-family collaboration, this study aims to explore how school-community-family collaboration empowers intergenerational learning through the case of taking grandparents to school.

Along with the complex relationship between population aging, age discrimination, and lifelong education, intergenerational learning has been recognized as one of the most effective ways of bridging the generation gap and contributing to intergenerational solidarity (Banks et al. 2024; Golenko et al. 2020; Trujillo-Torres et al. 2023). On the whole, many countries have gradually developed diversified models of intergenerational learning due to differences in economic development, political systems, and social culture (Aikman, 2023; Singh et al. 2021). For example, the typical model of ‘family intergenerational learning’ relying on blood relationships has been formed in some Asian countries under the influence of Confucianism (Ho, 2010). For another example, many European countries with high social welfare have established professional ‘intergenerational learning service centers or institutions’ to strengthen the learning relationship between older adults and the youngest (Andreoletti and Howard 2018; Ropes 2013). In addition, intergenerational learning in the United States is embedded in educational systems such as community schools and kindergartens to promote understanding between different generations (Fiebig 2014). It can be said that these intergenerational learning models in different cultures have both unique and general characteristics. However, what needs to be reflected is the school-community-family separation in the above intergenerational learning models. This separate relationship is deemed to be one important reason for the lack of dynamism and innovation in intergenerational learning (Lyu et al. 2020; Marchini and Macdonald 2020; Tuohy et al. 2023). Therefore, a hypothesis that needs to be considered is whether intergenerational learning is likely to be innovated at a time when school-community-family collaboration is embedded in the modern education system. It needs to be emphasized that the case of ‘taking grandparents to school’ in this study is a breakthrough in constructing intergenerational learning through family, school, and community collaboration.

Compared with the youngest, older adults are at a disadvantage in terms of cognitive response, human capital, and social adaptation (Van Orden et al. 2021). To improve the life quality of older adults and further realize a positive aging society, the World Health Organization proposed the concept of ‘age-friendly cities’ in 2005 (Torku et al. 2021). This concept advocated that cities should provide a livable environment system for older adults in housing, transportation, and health care. With the rapid development of lifelong education and older adults’ learning, Dublin City University in Ireland took the lead in proposing to build an ‘age-friendly university’ in 2012 (Montayre et al. 2023). On the one hand, this initiative responds to the demand for building age-friendly cities (A. Hong et al. 2023; Shi et al. 2023), and on the other hand, it calls for universities to fulfill the social service function of meeting older adults learning needs. According to statistics, hundreds of universities in North America, Europe, and Asia have already started to respond to the initiative of building age-friendly universities (Russell et al. 2022). On the whole, age-friendly universities do provide important support for the development of intergenerational learning in terms of educational concepts, resources, and platforms (Cannon et al. 2023; Gautam et al. 2023; Montayre et al. 2023; Montepare, 2019). However, some studies emphasized that the limited scope and functions of university social services make it difficult to fully meet the learning needs of older adults and youth (Farah and Montepare 2023; Lim et al. 2023). Therefore, activating more schools and communities in different stages and types to provide educational services and meet learning support for older adults has become an important direction for building age-friendly schools and communities (Jeste et al. 2016). Compared with age-friendly universities, this study aims to reveal how age-friendly primary schools, communities, and families enable innovative intergenerational learning.

Theoretical framework

In primitive societies, education and life were closely linked. Education as life or life also as education is the appropriate expression of the relationship between education and life in that era. As the social division became more explicit, schools were established with the main function of transmitting knowledge and skills especially reflected in the wave of the industrial revolution. The separation of school from life and society became the educational ecology of this era. At a time when informal education and social as well as emotional competence are gradually being emphasized, the relationship between school, community, and family is moving from separation to integration (Frederico and Whiteside 2016). Originating from the insight and understanding of the nature of education, the limitations of the school’s functions, and the educational responsibilities of community and family, American scholar Epstein proposed the ‘theory of overlapping spheres of influence’ or ‘cooperative education for schools, communities, and families’ (Epstein 2018b; Epstein and Sanders 2006). She believed that the experiences, values, and behaviors of families, schools, and communities profoundly influence the educational ecology (Epstein 2013). On the one hand, families, schools, and communities contribute unique values to human growth in relatively independent roles (Epstein 2018a). On the other hand, families, schools, and communities provide converging and unlimited potential educational energy for human development through their overlapping relationships (Epstein et al. 2011).

As the relationship between education, life, and society becomes increasingly close, an educational ecology constructed through collaboration among schools, communities, and families has become the direction of education reform in many countries (Stacer and Perrucci 2013; Twum-Antwi et al. 2020). The Chinese government, as an important country actively participating in global education governance, has gradually regarded cooperative education among schools, communities, and families as an important trend and principle in the system and practice of modern education in recent years (Li et al. 2023). The intergenerational learning practices explored in this study were created in the context of cooperative education in schools, communities, and families. It can be said that this case is a typical example of the theory of collaborative education of school, community, and family being transformed into practice. Therefore, this theoretical framework could provide support for explaining the processes of how schools, communities, and families create and empower intergenerational learning.

Methodology

Case background

With the gradual equalization of gender in the social division of labor, children in China tend to live with their grandparents (Y. Hong and Zeng 2023). At the same time, raising and educating grandchildren is the most basic and important relationship in the family under the profound influence of Confucianism (Hung et al. 2021). In addition to taking grandchildren to and from school every day, grandparents need to spend about four months of winter and summer vacations with their grandchildren. At a time of increasing aging, intergenerational conflicts, and weakening community functions, how to promote grandparents and grandchildren to grow up together in harmony has been considered an important individual, family, and social problem (Tang et al. 2022). To solve the complex and challenging practice problem, primary teachers, community educators, parents, grandparents, and grandchildren in eastern China collaborated to create a best practice called ‘taking grandparents to school: school-community-family collaboration empowers intergenerational learning’ during the summer vacation of 2021. This practical project demonstrates strong educational wisdom and deeply reflects the possible relationship among aging society, school-community-family collaboration, and intergenerational learning.

It is important to emphasize that, unlike intergenerational learning that is created by families, schools, and communities based on their respective strengths, this intergenerational learning project that took place in the community was created in collaboration with the school, the community, and the families over a two-month summer vacation. Guang Ming Primary School (pseudonym) is an urban primary school located in eastern China that includes grades one through five. Ding Hong and Pan Ling are the Chinese and math teachers of the school’s five class of third grade. There are 28 students in this class. All the students are 9 to 10 years old. Among them, there are 15 male students and 13 female students. Due to the unique holiday schedule, students, parents, and grandparents did not have consistent time to participate in the intergenerational learning project. Following the principles of voluntarism and initiative, Ding Hong and Pan Ling invited 12 families to participate in this intergenerational learning project. In China, the proximity of a school to its neighborhood creates a close relationship of resource exchange and mutual support. Guang Ming Community Center (pseudonym) is the closest community service center to Guang Ming Primary School. Guang Ming Community Center is formally connected to Guang Ming Primary School because they collaborate in providing educational platforms and learning support for students, parents, and grandparents. The intergenerational learning project in this study is a typical case of school, community, and family collaboration to build an educational ecology.

Field research site

To improve the comprehensibility and replicability, the information on the field research site needs to be described. Guang Ming Primary School was established in 1913 and is located in a developed area in eastern China. It is an urban primary school in Changzhou City, Jiangsu Province. With a long history of schooling and deep cultural heritage, this primary school has successively won a variety of honorary titles such as provincial advanced civilization unit and national advanced work organization. Guang Ming Community Center is the public cultural service place on the street where Guang Ming Primary School is located. It aims to satisfy the community residents in their pursuit of a better life and is committed to promoting social civilization and harmonious development. Every year, the Guang Ming Community Center organizes many activities such as health and wellness, picture book reading, and non-heritage culture activities. Overall, education, public welfare, and leisure are the main functions of the Guang Ming Community Center, which help the quality development of public cultural services in the surrounding area. The grandchildren who participated in this intergenerational learning project are all students living near the Guang Ming Community Center. Nowadays in China, where families, schools, and communities are becoming increasingly interconnected, some children and their parents and grandparents occasionally or frequently go to the Guang Ming Community Center on Saturday and Sunday to read, socialize, volunteer, and so on. As a result, they are relatively familiar with the Guang Ming Community Center, which provides important conditions for schools, communities, and families to create this intergenerational learning project.

The reason why this case is chosen is that firstly, the project has innovative value in educational practice and theory. Secondly, I as a theorist witnessed the whole process of initiating and creating the project. Since Chinese Children’s Day on June 1, 2019, I have begun to collaborate with the principal of this primary school on intergenerational learning under the recommendation of a professor at East China Normal University (Keyi et al. 2020). In the last five years, I have continued to explore and create intergenerational learning practices with the principal on the themes of environmental protection, and sustainable development based on the methodology of combining theory and practice in educational research. Moreover, intergenerational learning projects have proved to be highly recognized and supported by teachers, parents, grandparents, and grandchildren in China (Cheng et al. 2021). At the same time, these educational intergenerational learning practices have been widely reported and disseminated by media such as the local TV stations, which further attracts more schools, families, and communities to imitate and update. Among them, ‘taking grandparents to school: school-community-family collaboration empowers intergenerational learning’ is a typical practice mentioned above.

Qualitative research paradigm

Methodology is the way of thinking by which human beings understand and change the world. Exploring the complex relationship between questions and methods is considered a fundamental issue in understanding methodology (Weber 2017). As for the methodology of educational research, it is the thinking expression of understanding the essence of education and exploring educational practice (Sahin and Öztürk 2019). In a word, qualitative interpretation, quantitative inference, philosophical inquiry, and historical retrospection constitute diversified research paradigms in social science. The relevance of research methods and questions determines which educational research paradigms are used. Qualitative research is a paradigm for understanding social phenomena created by researchers in their interaction with the subjects (Fossey et al. 2002). Constructing meaning, revealing processes, understanding culture, and exploring the unknown have become important features of the qualitative research paradigm (Aspers and Corte 2019). This study aims to unpack the ‘black box’ of how school-community-family collaboration creates intergenerational learning. Cross-cultural context and the dynamic mechanism of waiting to be opened become key features of this ‘black box’. Considering the match between the research paradigm and the research questions, this study attempts to use a qualitative research paradigm to open up the dynamic process of how schools, communities, and families create intergenerational learning.

Unstructured interview method

The unstructured interview method is highly favored and effective in sociology, anthropology, and other social sciences. It is a research method in which interviewers and interviewees collect data through interaction between question and answer (Alshenqeeti 2014; Powell and Brubacher 2020). The unstructured interview method is more suitable for discovering people’s complex psychological activities and has become a unique method in social science (Qu and Dumay 2011). Besides the advantages of interviews and their wide application in social sciences, the research question of how school-community-family creates intergenerational learning is intrinsically related to the interview method. Specifically, teachers, community educators, parents, grandparents, and grandchildren create intergenerational learning based on complex psychology and practice. Unstructured interviews that explore dynamic and complex processes offer unique value in understanding how school-community-family creates intergenerational learning.

The implementation of this study strictly adhered to the academic ethics of the Declaration of Helsinki and was reviewed and approved by the Academic Ethics Committee of the University. Considering that this project involved multiple subjects in the process of being created, each of the different roles should be recruited as participants. The principles of voluntary participation, equality, withdrawal at any time, and anonymity were applied to the entire process of recruiting and interviewing (Allmark et al. 2009). What role or function interviewees play in the process of intergenerational learning becomes the core question of the interview. In July 2022, I contacted parents, grandchildren, grandparents, teachers, and community educators associated with this project. After seeking their wishes, face-to-face interviews were allowed. Influenced by uncertainties such as time and willingness, one primary school principal, one primary school teacher, two community educators, five parents, five grandparents, and five grandchildren were recruited as participants. Separate interviews were implemented to avoid interfering with each other and affecting the authenticity of the data.

The interview questions were developed according to the different roles of the participants. The interview questions for the primary school principal and teacher focused on why you advocate school, community, and family collaboration to create intergenerational learning, and what roles and actions you take in this collaborative creation process. The interview questions for the two community educators focused on why you support school, community, and family collaboration to create intergenerational learning and what assistance you have provided to move this project from concept to practice. Interview questions for the parent included how you understand school, community, and family collaboration to create intergenerational learning and what you have done to be a driving force in this project. Interview questions for grandchildren focused on why you were willing to take your grandparent to school and how you persuaded your grandparent to participate in intergenerational learning. Interview questions for grandparents included why you would like to follow your grandchildren to school and what you see as the value of this intergenerational learning.

Formal interviews were conducted from July 15 to 30, 2022. Each participant was interviewed for approximately 30–50 min. Due to the uncertainty factor, the primary school principal, one community educator, and three parents were interviewed twice. All interviewees agreed to be recorded, which helped to document the study data in detail and comprehensively. Demographic information of the interviewees is shown in Table 1.

Data analysis

To improve the completeness and accuracy of the interview data analysis, I first converted the audio recordings of the nineteen interviews into Chinese text. Then, considering the requirement of using English to write the article, I translated Chinese text into English text through a word-by-word approach. To further ensure the accuracy of the translation, I invited two colleagues who teach English to help me check and revise the English version of the interview texts from nineteen participants. After completing and finalizing the interview texts, I kept thinking about how to code scientifically, efficiently, and rigorously. Overall, thematic coding was applied to the interview data analysis, including deductive coding and inductive coding, which aimed to answer the research question of how schools, communities, and families collaborate to create intergenerational learning (W. Xu and Zammit 2020). Top-down deductive coding was finished using the theoretical principles of school-community-family collaborative education. Bottom-up inductive codes were developed based on sufficient interview data of nineteen participants. The findings were dynamically constructed in population aging, school-community-family collaboration, intergenerational learning, and Chinese cultural contexts.

To ensure as much reliability as possible, two colleagues in similar research fields were invited by me to independently code interview data (Mackieson et al. 2019; Morgan, 2022). Specifically, reading, categorizing, and constructing were viewed as the three stages of the interview data analysis process. Firstly, all interview data were read thoroughly and meticulously aiming to understand and grasp the scope and meaning of the interview data. Secondly, the interview data were reorganized in a categorical approach based on the theoretical framework of school, community, and family collaboration in constructing an educational ecology. Thirdly, the interview data were dynamically and structurally revealed and constructed to reflect the Chinese sociocultural background to address how schools, communities, and families collaborate to create intergenerational learning. Finally, this article was fed back to nineteen interviewees to improve reliability and validity. The accuracy of the interview information and the authenticity of the research findings were confirmed after a few adjustments and revisions in the feedback of all participants. Overall, the coding results were consistent, which effectively eliminated subjective biases in the coding process and research findings.

Findings

According to the research questions and interview data, schools, communities, and families play unique and irreplaceable roles in empowering this intergenerational learning project. While intertwining educational policies and responsibilities, the primary school designed an intergenerational learning project in interaction with the community and families. At the same time, upholding the principles of social service and an age-friendly field, the community provided adequate educational resources and platforms for implementing this intergenerational learning project in a synergistic and supportive role. Considering the generation gap and intergenerational integration between grandparents and grandchildren, the family as the main participant helped the transformation of intergenerational learning from a possible imagination into real practice with the facilitation of school and community.

Schools as program advocates: education policy and school responsibility

On January 13, 2023, the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China and other thirteen departments issued a policy on ‘Recommendation on Improving the Mechanism of Collaborative Education between Schools, Families and Community’ (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China 2023). This recommendation puts forward that the school-family-community collaborative education mechanism of ‘active advocacy by schools, full responsibility of families, and effective support from the community’ is hopeful to be realized by 2035 in China. Some studies emphasize that educational policy with coercive administrative power tends to influence the direction of educational practice deeply and rapidly (Slavin 2002). This collaborative relationship between educational policy and practice was also repeatedly expressed by Ding Hong as a primary school principal. She argued that under the influence of school bullying, intergenerational conflicts, and academic pressures, the educational policy push for school-family-community collaboration gradually began to transform from an idealized educational imagination into a visible educational action. One of the most important reasons why this intergenerational learning project can be designed, organized, and implemented is the guidance and requirements of educational policies for school-family-community collaboration. As she stated:

This intergenerational learning project was initially inspired by school-family-community collaboration. I saw too many conflicting relationships between grandparents and grandchildren. How to change their disharmonious relationship has become an important problem faced by teachers. In the communication with Pan Ling, I suddenly realized that lifelong learning constitutes everyone’s lifestyle in the current era. I wondered if it was possible to establish a new relationship of mutual learning between grandparents and grandchildren through the concept and practice of learning.

Adhering to the belief of ‘learning to change intergenerational relationships’, Ding Hong and Pan Ling first grasped the family’s views on the intergenerational learning project through individual home visits and all parent meetings. Second, parents, grandparents, and grandchildren were introduced to how to carry out the intergenerational learning project of taking grandparents to school during the summer vacation for two months. Considering positive aging, child development, and harmonious family relationships, parents readily agreed to participate in the intergenerational learning project initiated by the school. In Ding Hong’s view, the active support of parents and the high participation of grandchildren and grandparents were the key reasons why intergenerational learning can successfully move from concept to practice.

Honestly, intergenerational learning cannot be created collaboratively without the support and involvement of families. In my opinion, this intergenerational learning project provides an opportunity or platform for teachers and parents to communicate about children’s academic, behavioral, physical, and mental development. In addition, it is one of the responsibilities of schools to strengthen family education guidance services. Schools should respond to parents’ concerns about educational participation by popularizing theoretical knowledge and practical skills in family education.

A community is a public space that residents are familiar with in living, entertainment, and interaction (Noddings 1996). Providing educational services to community residents is considered an important responsibility of the school function in social services (Valli et al. 2016). Considering the convenience and accessibility of summer life, learning space, and educational resources, Ding Hong and Pan Ling decided after many discussions that this intergenerational learning project might be appropriate to be created in a community education center near families. Therefore, driven by education policy, they sincerely expressed to two community educators their desire to create an intergenerational learning project through community resources and platforms. Taking into account the willingness of school-community-family collaboration and the social service function of the community, the two community educators similar to the parents’ active participation fully supported the intergenerational learning project to be designed, organized, and implemented in the community. As Pan Ling said:

Ding Hong and I believe that the relationship between school and society is not disconnected but connected. Our school needs to actively expand the educational space and resources outside the school to better meet the diversified learning needs of the family and the community. This intergenerational learning project is implemented in the community, which not only stimulates community functions but also expands more opportunities for schools to serve society driven by education policies.

According to the interview data of Ding Hong and Pan Ling as teachers, it was clear that the school played multiple roles in idea proposal, project formulation, and practice promotion in creating intergenerational learning projects in collaboration with communities and families. Specifically, the educational policy of creating an ecosystem of collaborative education among schools, communities, and families was highly recognized by Ding Hong and Pan Ling. Based on the conflict between grandparents and grandchildren, as well as the desire to move toward harmonious, symbiotic family relationships, Ding Hong and Pan Ling proposed educational programs in which co-learning and mutual learning may help optimize intergenerational relationships.

As the concept and practice of lifelong learning became more widely disseminated, understood and recognized, Ding and Pan further realized that the function of schools needed to be expanded from educating children to serving all people. It can be further elaborated that in the complex interweaving and multiple interactions of educational policies, practices, and theories, Ding Hong and Pan Ling, uphold the educational beliefs of collaborative education among schools, communities, and families, as well as learning to optimize intergenerational relationships, proposed an intergenerational learning project in which grandchildren take their grandparents to school.

Community as collaborative support: service functions and age-friendly fields

Compared to a national system, community committees form a relatively close relationship with their residents (Hall 1993). From an international perspective, community committees provide services to residents in economic production, democratic participation, ecological construction, and educational support (Mannarini and Fedi 2009). Due to differences in social development and cultural evolution, diverse modes of community functioning have been created and developed in many countries. In China, providing comprehensive practical activities for children, continuing education for workers, and policy advice for older adults are the basic functions of community committees (Q. Xu et al. 2010). Importantly, the comprehensive service functions were reiterated and emphasized by the two community educators as interviewees. For example, Qiu Yun, who has been working in community education for 26 years, expressed:

Although the community is the smallest unit of residents’ lives, it is a comprehensive and complex interpersonal field. I, as a community educator, have always maintained the awareness, attitude, and behavior of providing services to residents. These services include physical exercise, psychological counseling, career development, and family relationships. In addition, this intergenerational learning project facilitated by school, family, and community collaboration is included in particular.

It should be emphasized that Zhang Liang and Qiu Yun, as community educators, clearly defined the community’s functions or responsibilities. When Ding Hong and Pan Ling were actively invited to collaborate in designing, organizing, and implementing an intergenerational learning project, they highly agreed and fully supported this educational project to be created and developed in the community. Moreover, considering the relationship between intergenerational learning and family and school, the two community educators argued that community provides a suitable practice field for implementing this intergenerational learning project. Therefore, Zhang Liang emphasized that intergenerational learning project is not extra work given to the community by schools and families, but rather an important responsibility of the community’s service function and age-friendly field. As he states:

After hearing Ding Hong and Pan Ling explain the intergenerational learning project, Qiu Yun and I immediately realized that intergenerational learning is a good project to stimulate the social service function of the community and highlight the age-friendly characteristics of the community. What reason does the community committee have not to do it? Our community should not only actively collaborate with schools and families to empower intergenerational learning projects from concept to practice, but also provide maximum support for the successful creation of an intergenerational learning platform.

Under the conceptual design and practical needs of intergenerational learning advocated by schools, Zhang Liang and Qiu Yun further obtained an understanding of what support families and schools should provide in the establishment of intergenerational learning through communication with parents, grandparents, and grandchildren. Overall, this intergenerational learning project was not successfully created without the orderly and efficient organization of the community in terms of learning time, classroom space, and human resources. In turn, the significance of this project not only fully activated the community service function, but also highlighted the important characteristics of community as an age-friendly field. This was distinctly reflected in Qiu Yun’s expression:

To empower intergenerational learning projects with schools and families, community educators assumed the identity or role of organizers, coordinators, and collaborators. Specifically, when grandchildren came to the community with grandparents at the initiative of the school, community educators arrived early in the classroom to lay out materials that may be needed for teaching and also helped the school teachers solve uncertain problems that occur temporarily in the classroom.

From the interview data of Zhang Liang and Qiu Yun as community educators, service providers, and educators, it can be found they recognized that meeting people’s physical and mental development needs in knowledge acquisition, career development, and entertainment activities is the basic responsibility and important function of the community. Driven by the policy requirements and theories of school, community, and family cooperation in constructing educational ecology, community workers responded positively to Ding Hong and Pan Ling’s theoretical construction and practical exploration of cooperative creation in this intergenerational learning project. Specifically, Zhang Liang and Qiu Yun, as community educators, provided human resources, learning platforms, and educational infrastructures for the successful implementation of this intergenerational learning project in their roles or capacities as organizers, coordinators, and collaborators. The process from concept to practice of this intergenerational learning project fully activated the function of the Chinese community in the new era to provide an educational platform and learning support for all.

Family as subjective participation: life divides and intergenerational integration

As both fathers and mothers participate in the labor market outside the home, grandparenting has become a common phenomenon globally. This phenomenon is more prominent and typical in Chinese families where three generations live together. Influenced by differential life courses and rapid social change, grandparents and grandchildren face a severe generation gap in knowledge, skills, and values (Taneja et al. 2018). How to promote intergenerational harmony has become an epochal dilemma that is difficult to solve by individuals, families, schools, and society (Gilmore-Bykovskyi et al. 2022; Strom and Strom 2000). The parents interviewed emphasized that lacking professional knowledge and skills of family education is an important reason why it is difficult to mitigate and eliminate the disputes and conflicts between grandchildren and grandparents. Under the background of the modern education system paying more and more attention to school-family-community collaboration, seeking diversified help from school and community professional education became the first active choice of many parents interviewed.

I do not know what to do when faced with conflicts between children and their grandparents. Once there is an opportunity for a teacher home visit or parent-teacher conference, I choose to ask the teacher how to solve these conflicts correctly. (Yu Zhe)

From the perspective of self-evaluation, I am not a good or even qualified parent. It is difficult for my existing family education literacy to successfully and effectively support parenting practices in which the generation gap is the main manifestation. Therefore, I am eager to get help from teachers. (Chun Li)

The division of labor drives each system of society to play an irreplaceable role in its uniqueness. The education system, represented by schools, has the mission and responsibility of professional education in training students and transmitting scientific knowledge. Unlike school teachers and community educators who have professional educational awareness and capacity, parents lack professional educational knowledge and capacity due to their life course and division of labor. Due to their full trust in professional education, parents always participated in school and community education with positive attitudes and actions. When asked by Ding Hong, Pan Ling, and the two community educators whether they supported the intergenerational learning project to create a new model of the grandparent-grandchild relationship, the parents generally showed a strong participatory attitude and positive supportive behaviors. In addition, parents frequently emphasized that school-community-family collaboration was a great invention of the modern education system. This intergenerational learning project provided a rare opportunity and platform for parents to solve their troubled problems in family education.

I certainly collaborate with schools and communities to create this intergenerational learning project. This educational project helps bridge the generation gap between children and their grandparents. (Shu Xin)

I am grateful to the school and community for inventing this intergenerational learning project. It is a way to promote intergenerational integration of children and grandparents through learning. (Shu Hao)

Instead of the intergenerational learning project being created by the collaboration of the school, community, and family, the school and community have guided me to better implement family education with their professional strength. (Chong Guang)

In addition to parents’ high support and active participation in this intergenerational learning project, grandparents and grandchildren were also involved in this educational activity with theoretical value and practical significance. On the one hand, parents tended to encourage their children to take their grandparents to school based on the position of family harmony. On the other hand, influenced by teachers, community educators, parents, grandchildren, and grandparents as subjective roles or identities actively engaged in the intergenerational learning project based on a vision of breaking the generation gap and promoting intergenerational integration. Specifically, grandchildren and grandparents abided by the spirit of the contract and came together at planned times to learn in the classroom jointly established by schools, communities, and families.

The reason, why I actively take grandparents to community school, is that bridging the generation gap and promoting intergenerational integration will be continuously realized in intergenerational learning activities. (Zi Xuan)

I am a practitioner of lifelong learning. I am very interested in the intergenerational learning project. Therefore, I am happy to build this new relationship in mutual learning with my grandchildren. (Qiu Xiang)

To carry out intergenerational learning activities more efficiently and orderly, my grandparents and I signed our names on the learning commitment letter. Reaching a covenant relationship with grandparents has laid a good foundation for this two-month intergenerational learning. (Fei Yan)

Interview data from parents, grandparents, and grandchildren showed that family members exhibit enthusiastic attitudes and participatory behaviors when invited by schools and communities to collaborate in creating this intergenerational learning project. This attitude and behavior were formed in a combined process of intergenerational divides, family education challenges, and school as well as community support. Specifically, many families in China are facing intergenerational gaps and conflicts due to the huge differences in the life course of grandparents and grandchildren. However, parents as non-professional educators lack not only scientific knowledge of family education but also effective family education methods. Under the trend of schools, communities, and families cooperating to construct an educational ecology, parents tried to seek help and support from specialized teachers and community workers to optimize the relationship between grandparents and grandchildren. Therefore, when schools and communities extend invitations to families that may effectively resolve intergenerational conflicts, family members engage in creating intergenerational learning projects with positive attitudes and behaviors.

Discussion

The theoretical contribution of school, community, and family collaboration in creating intergenerational learning is activated and highlighted in comparison, and reflection with the existing literature. Indeed, intergenerational learning in previous studies has been shaped into complex and diverse models depending on changing times, national cultures, cognitive thinking, and social classes (Golenko et al. 2020). On the whole, these previous studies tended to divide intergenerational learning models from a geospatial perspective in the complex and varied educational practice (Andreoletti and Howard 2018; Fiebig 2014; Ho 2010; Marchini and Macdonald 2020; Ropes 2013). Furthermore, family intergenerational learning, community intergenerational learning, and school intergenerational learning in existing research were considered to be the most common theoretical frameworks and practical models for understanding and analyzing intergenerational learning (Andreoletti and Howard 2018; Fiebig 2014; Ho 2010; Marchini and Macdonald, 2020; Ropes 2013). It should be emphasized that these studies and practices on intergenerational learning played an important role and value in eliminating intergenerational bias, promoting intergenerational reciprocity and symbiosis, and moving towards positive aging. However, the previous research about intergenerational learning theory and practice is somewhat fractured rather than linked and integrated. It could be argued that these intergenerational learnings, which occur independently in schools, communities, and families, were relatively lacking in tapping and activating the potential of cooperative education. In contrast, this study unpacks and constructs how school-community-family in China create practical models and theoretical frameworks for intergenerational learning by establishing an ecosystem of collaborative education. Moreover, establishing the connection and integration of collaborative education ecosystems and intergenerational learning among schools, communities, and families can help provide more possibilities for understanding cross-border education, intergenerational relationships, learning mechanisms, and social change.

At the same time, the cooperative education ecology constructed by school-community-family needs to be discussed and reflected because of their connection with intergenerational learning. Previous studies on school-community-family collaboration tended to regard children’s development as the core direction or even the only goal (Alston-Abel and Berninger 2018) while neglecting the learning opportunities and educational rights of other people (Yuen 2011). Considering the complex intertwined position of lifelong education, intergenerational learning, and subject relationship (Baquedano-López et al. 2013; Schneider and Arnot 2018), this study does not fully agree that child development is the entire motivation of school-community-family collaboration. How the intergenerational learning project of this study is empowered argues that multiple subjects including children, grandchildren, and others have the potential to grow and develop in school-community-family collaboration. Therefore, this study expands the theoretical value and practical direction of school-community-family collaboration in seeing the subject identity of grandparents and grandchildren based on the comprehensive and educational intergenerational learning project.

In contrast to age-friendly cities or societies that provide services for older adults in terms of public welfare, transportation, infrastructure, and social security (Jeste et al. 2016; Torku et al. 2021), intergenerational learning that takes place in the community ensures the right to education and learning opportunities for older adults. It is worth recognizing that hundreds of universities in North America, Europe, Asia, and other countries are responding or have responded to the ‘Age-Friendly University’ initiative launched by Dublin City University in Ireland in 2012 (Montayre et al. 2023; Montepare 2019). However, age-friendly school projects have not been widely implemented in other types of schools across the education system (Lim et al. 2023). It is important to emphasize that under the influence of population aging, lifelong education, social change, and intergenerational conflict, this study is convinced that primary schools and communities are fully likely to provide friendly support and services to meet the educational needs and learning aspirations of older adults.

Conclusion

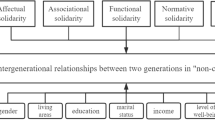

Generational relationships that highlight learning characteristics have been created under the drive of population aging, generational conflict, lifelong education, and family-school-community collaboration. In the face of low-quality teacher supply and unsustainable operation mechanisms, optimizing the practical path and theoretical framework of intergenerational learning has become an important goal to improve learning quality and promote high-quality education development (Stephan 2021; Yembuus 2021). With the global education system moving towards school-community-family collaboration, an urban primary school in eastern China joined a community and families to create an efficient intergenerational learning project of ‘taking grandparents to school’. Exploring how this intergenerational learning project was created by school-community-family collaboration becomes the core research question. To obtain sufficient empirical data, one principal and one teacher from Guang Ming Primary School, two community educators from Guang Ming Community Center, and parents, grandparents, and grandchildren from five families were recruited as participants. According to the unstructured interview data, Guang Ming Primary School, Guang Ming Community Center, and families played unique and irreplaceable roles in empowering this intergenerational learning project. In intertwining educational policies and school responsibilities, the Guang Ming Primary School designed macro agendas and micro plans of the intergenerational learning project in interaction with the Guang Ming Community Center and families. At the same time, upholding the principles of social service and age-friendly, the Guang Ming Community Center provided adequate educational resources and convenient learning platforms for implementing this intergenerational learning project in a synergistic and supportive role. Considering the challenges of the generation gap and the goal of intergenerational integration between grandparents and grandchildren, the families as the participants contributed to the transformation of intergenerational learning from possible imagination into visible practice with the help and support of the school and community. To further highlight the new knowledge contribution of this study, the practical cases of school-community-family cooperation to create intergenerational learning guided by research questions, interview data, and research findings are further dynamically constructed into the theoretical framework in Fig. 1.

This theoretical framework is grounded in China’s contemporary context, institutional challenges, and cultural innovations, such as the uncertainty risks of population aging and the growing intergenerational divide. Driven by their respective needs, responsibilities, and functions, the Guang Ming Primary School, Guang Ming Community Center, and families have created a new intergenerational learning model in which grandchildren take their grandparents to school by establishing an ecological relationship of collaborative education. It can be said that the intergenerational learning of this case study, facilitated by the Guang Ming Primary School, the Guang Ming Community Center, and families, is a typical practice in China’s overall move towards a modernized society, as well as a representative theoretical framework created by individuals, organizations, and society in the face of various challenges and contradictions. It should be further emphasized that the Guang Ming Primary School, Guang Ming Community Center, and families play different roles and construct complex and dynamic relationships within theoretical frameworks rooted in practical investigations. In conclusion, the theoretical framework and practical pattern of the intergenerational learning project of ‘taking grandparents to school’ created by collaboration among the Guang Ming Primary School, Guang Ming Community Center, and families provided a more comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the relationship between individual development, educational functions, and social change.

In addition to the theoretical value highlighted and elaborated above, this study has important implications for the research directions of theorists, the action strategies of practitioners, and the scientific decisions of policymakers. Based on the successful practice of school-community-family collaboration in creating intergenerational learning in China, theorists may need to strengthen the theoretical or conceptual framework of collaborative education and continue to explore the best model of intergenerational learning in local contexts with the research consciousness of building a learning family, community, and society. Educational practitioners, community workers, and parents may need to take action to promote the relationship between school-community-family from separation toward integration, and to explore more intergenerational learning models as direct subjects of optimizing and renewing educational practices. At the same time, it is recommended that policymakers pay attention to the individual significance and social value of intergenerational learning, and formulate scientific policies for school-community-family cooperation to promote intergenerational learning through research rooted in both practical investigations and theoretical frameworks.

In a word, the theoretical framework and practical model of this intergenerational learning promoted by school-community-family cooperation have been created in the complex process of actively responding to the aging society, innovating the education system, and promoting intergenerational symbiosis in China. Intergenerational learning, typified by ‘taking grandchildren to school’, has continued into the present and future since its creation in 2021 in China. Theorist research, practitioner action, and policymaker support have provided essential safeguards for this intergenerational learning project to move toward sustainability. With academic communication, media dissemination, and practice development, this project has been copied, reflected upon, and renewed in other urban and rural areas of China for its positive impact on promoting intergenerational reciprocity, community values, and school functions. However, there are differences between another country and China in population aging, educational ecology, and social development, which may restrict the intergenerational learning created by school, community, and family cooperation to be widely understood, and recognized to some extent. Although the development of education is influenced by many factors such as different economic, political, and cultural models, promoting people’s physical and mental health and social progress is always the common pursuit of the essence and function of education around the world. Therefore, intergenerational learning created by collaboration among schools, communities, and families highlights Chinese characteristics and has universal characteristics. It is foreseeable that this theoretical framework and practical model of intergenerational learning will be continuously disseminated, understood, recognized, and recreated as global education continues to connect and exchange. It is expected that countries with different cultural characteristics and education systems should consider both international experience and local exploration as much as possible when promoting intergenerational learning programs, to provide more possibilities for constructing the theoretical framework and practical model of intergenerational learning.

Data availability

The interview data used to effectively support and answer research questions are all contained in this article.

References

Aikman S (2023) Hidden, scattered and reconstructed: indigenous lifeways, knowledges and intergenerational learning. Comp: J Compar Int Edu 1–18

Al-Lawati S (2019) Understanding the psychology of youths: Generation gap. Int J Psychol Counselling 11(6):46–58

Allmark P, Boote J, Chambers E, Clarke A, McDonnell A, Thompson A, Tod AM (2009) Ethical issues in the use of in-depth interviews: literature review and discussion. Res Ethics 5(2):48–54

Alshenqeeti H (2014) Interviewing as a data collection method: A critical review. Engl Linguist Res 3(1):39–45

Alston-Abel NL, Berninger VW (2018) Relationships between home literacy practices and school achievement: Implications for consultation and home–school collaboration. J Educ Psychol Consultation 28(2):164–189

Andreoletti C, Howard JL (2018) Bridging the generation gap: Intergenerational service-learning benefits young and old. Gerontol Geriatrics Educ 39(1):46–60

Aspers P, Corte U (2019) What is qualitative in qualitative research. Qualitative Sociol 42:139–160

Bæck UDK (2010) Parental involvement practices in formalized home–school cooperation. Scand J Educ Res 54(6):549–563

Banks JA, Frydenberg E, Liang R (2024) Promoting social and emotional learning in early childhood through intergenerational programming: a systematic review. Educ Develop Psychologist 41(1):12–28

Baquedano-López P, Alexander RA, Hernandez SJ (2013) Equity issues in parental and community involvement in schools: What teacher educators need to know. Rev Res Educ 37(1):149–182

Boström A-K (2004) Intergenerational learning in Stockholm County in Sweden: A practical example of elderly men working in compulsory schools as a benefit for children. J Intergenerational Relatsh 1(4):7–24

Boulton-Lewis GM (2010) Education and learning for the elderly: Why, how, what. Educ Gerontol 36(3):213–228

Cannon M, Kerwood R, Ramon M, Rowley SJ, Rubio H (2023) Laying the groundwork for an Age-Friendly University: A multi-method case study. Gerontol Geriatri Educ 44(1):1–14

Cheng H, Lyu K, Li J, Shiu H (2021) Bridging the digital divide for rural older adults by family intergenerational learning: A classroom case in a rural primary school in china. Int J Environ Res public health 19(1):371

Chineka R, Yasukawa K (2020) Intergenerational learning in climate change adaptations; limitations and affordances. Environ Educ Res 26(4):577–593

Clark LS (2009) Digital media and the generation gap: Qualitative research on US teens and their parents. Inf, Commun Soc 12(3):388–407

Elena-Bucea A, Cruz-Jesus F, Oliveira T, Coelho PS (2021) Assessing the role of age, education, gender and income on the digital divide: Evidence for the European Union. Inf Syst Front 23:1007–1021

Epstein JL (2013) Ready or not? Preparing future educators for school, family, and community partnerships. Teach Educ 24(2):115–118

Epstein JL (2018a) School, family, and community partnerships in teachers’ professional work. J Educ Teach 44(3):397–406

Epstein JL (2018b) School, family, and community partnerships: Preparing educators and improving schools: Routledge

Epstein JL, Galindo CL, Sheldon SB (2011) Levels of leadership: Effects of district and school leaders on the quality of school programs of family and community involvement. Educ Adm Q 47(3):462–495

Epstein JL, Sanders MG (2006) Prospects for change: Preparing educators for school, family, and community partnerships. Peabody J Educ 81(2):81–120

Epstein JL, Sheldon SB (2019) The importance of evaluating programs of school, family and community partnerships. Aula abierta 48(1):31–42

Estebsari F, Dastoorpoor M, Khalifehkandi ZR, Nouri A, Mostafaei D, Hosseini M, Aghababaeian H (2020) The concept of successful aging: a review article. Curr aging Sci 13(1):4–10

Farah KS, Montepare JM (2023) Unusual suspects for Age-Friendly University (AFU) intergenerational classroom exchange: A classroom case study in forensic science. Gerontol Geriatrics Educ 44(1):41–50

Fiebig JN (2014) Learning through service: Developing an intergenerational project to engage students. Educ Gerontol 40(9):676–685

Fossey E, Harvey C, McDermott F, Davidson L (2002) Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Aust N. Z J psychiatry 36(6):717–732

Foster L, Walker A (2015) Active and successful aging: A European policy perspective. Gerontologist 55(1):83–90

Frederico M, Whiteside M (2016) Building school, family, and community partnerships: Developing a theoretical framework. Aust Soc work 69(1):51–66

Gautam R, Sritan S, Khumrungsee M, Melillo KD (2023) Promoting Age-Friendly University by Engaging Older Adults in Intergenerational Learning at Institutions of Higher Education: PRISMA-Guided Scoping Review. J Intergenerational Relationships 1–33

Gilmore-Bykovskyi A, Croff R, Glover CM, Jackson JD, Resendez J, Perez A, Manly JJ (2022) Traversing the aging research and health equity divide: Toward intersectional frameworks of research justice and participation. Gerontologist 62(5):711–720

Golenko X, Radford K, Fitzgerald JA, Vecchio N, Cartmel J, Harris N (2020) Uniting generations: A research protocol examining the impacts of an intergenerational learning program on participants and organisations. Australas J Ageing 39(3):e425–e435

Hall S (1993) Culture, community, nation. Cultural Stud 7(3):349–363

Hess M, Nauman E, Steinkopf L (2016) Population Ageing, the Intergenerational Conflict, and Active Ageing Policies–a Multilevel Study of 27 European Countries. J Popul Ageing 10(1):11–23

Ho C (2010) Intergenerational Learning (Between Generation X & Y) in Learning Families: A Narrative Inquiry. Int Educ Stud 3(4):59–72

Hong A, Welch-Stockton J, Kim JY, Canham SL, Greer V, Sorweid M (2023) Age-Friendly Community Interventions for Health and Social Outcomes: A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res public health 20(3):2554

Hong Y, Zeng D (2023) Early and continuing grandparental care and middle school students’ educational and mental health outcomes in China. J Commun Psychol 51(2):676–694

Hosseini H, Savadian P, Karimian H (2022) Generational gap and the lived experience of Semnan parents from virtual space. J Women, Fam, Soc Stud 10(1):1–28

Hung SL, Fung KK, Lau ASM (2021) Grandparenting in Chinese skipped-generation families: Cultural specificity of meanings and coping. J Fam Stud 27(2):196–214

Jerman BB, Blažič AJ (2020) Overcoming the digital divide with a modern approach to learning digital skills for the elderly adults. Educ Inf Technol 25(1):259–279

Jeste DV, Blazer II DG, Buckwalter KC, Cassidy K-LK, Fishman L, Gwyther LP, Schmeding E (2016) Age-friendly communities initiative: public health approach to promoting successful aging. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 24(12):1158–1170

Keyi L, Xu Y, Cheng H, Li J (2020) The implementation and effectiveness of intergenerational learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from China. Int Rev Educ 66(5-6):833–855

Kotschy R, Sunde U (2018) Can education compensate the effect of population ageing on macroeconomic performance? Econ Policy 33(96):587–634

Lee K, Jarrott SE, Juckett LA (2020) Documented outcomes for older adults in intergenerational programming: A scoping review. J Intergenerational Relatsh 18(2):113–138

Li J, Xue E, Liu C, Li X (2023) Integrated macro and micro analyses of student burden reduction policies in China: call for a collaborative “family–school–society” model. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10(1):1–10

Lim JS, Park M-B, O’Kelly CH, Knopf RC, Talmage CA (2023) A tool for developing guidelines for institutional policy: a 60 indicator inventory for assessing the age-friendliness of a university. Educ Gerontol 49(3):214–227

Luo MS, Chui EWT, Li LW (2020) The longitudinal associations between physical health and mental health among older adults. Aging Ment Health 24(12):1990–1998

Lyu K, Xu Y, Cheng H, Li J (2020) The implementation and effectiveness of intergenerational learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from China. Int Rev Educ 66:833–855

Mackieson P, Shlonsky A, Connolly M (2019) Increasing rigor and reducing bias in qualitative research: A document analysis of parliamentary debates using applied thematic analysis. Qual Soc Work 18(6):965–980

Mannarini T, Fedi A (2009) Multiple senses of community: The experience and meaning of community. J Community Psychol 37(2):211–227

Marchini S, Macdonald DW (2020) Can school children influence adults’ behavior toward jaguars? Evidence of intergenerational learning in education for conservation. Ambio 49(4):912–925

Mead M (1940) Social change and cultural surrogates. J Educ Sociol 14(2):92–109

Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (2023) Recommendation on Improving the Mechanism of Collaborative Education between Schools, Families and Community. Retrieved from http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A06/s3325/202301/t20230119_1039746.html

Miyamoto H, Yoshino N (2022) A note on population aging and effectiveness of fiscal policy. Macroecon Dyn 26(6):1679–1689

Moestue H, Huttly S (2008) Adult education and child nutrition: the role of family and community. J Epidemiol Commun Health 62(2):153–159

Montayre J, Maneze D, Salamonson Y, Tan JD, Possamai-Inesedy A (2023) The making of age-friendly universities: A scoping review. Gerontologist 63(8):1311–1319

Montepare JM (2019) Introduction to the Special Issue-Age-Friendly Universities (AFU): Principles, practices, and opportunities. Gerontol Geriatrics Educ 40(2):139–141

Morgan H (2022) Understanding thematic analysis and the debates involving its use. Qual Rep 27(10):2079–2090

Noddings N (1996) On community. Educ Theory 46(3):245–267

Passey D (2014) Intergenerational Learning Practices–Digital Leaders in Schools. Educ Inf Technol 19(3):473–494

Portacolone E (2015) Older Americans living alone: The influence of resources and intergenerational integration on inequality. J Contemp Ethnogr 44(3):280–305

Powell MB, Brubacher SP (2020) The origin, experimental basis, and application of the standard interview method: An information gathering framework. Aust Psychologist 55(6):645–659

Qu SQ, Dumay J (2011) The qualitative research interview. Qualitative Res Account Manag 8(3):238–264

Ropes D (2013) Intergenerational learning in organizations. Eur J Train Dev 37(8):713–727

Ross C, Kennedy M, Devitt A (2021) Home School Community Liaison Coordinators (HSCL) perspectives on supporting family wellbeing and learning during the Covid-19 school closures: critical needs and lessons learned. Ir Educ Stud 40(2):311–318

Russell E, Skinner MW, Fowler K (2022) Emergent challenges and opportunities to sustaining age-friendly initiatives: Qualitative findings from a Canadian age-friendly funding program. J Aging Soc Policy 34(2):198–217

Sahin MD, Öztürk G (2019) Mixed Method Research: Theoretical Foundations, Designs and Its Use in Educational Research. Int J Contemp Educ Res 6(2):301–310

Schneider C, Arnot M (2018) Transactional school-home-school communication: Addressing the mismatches between migrant parents’ and teachers’ views of parental knowledge, engagement and the barriers to engagement. Teach Teach Educ: Int J Res Stud 75(1):10–20

Shi J, Liu X, Feng Z (2023) Age-friendly cities and communities and cognitive health among Chinese older adults: Evidence from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Studies. Cities 132:104072

Singh S, Thomas N, Numbudiri R (2021) Knowledge sharing in times of a pandemic: An intergenerational learning approach. Knowl Process Manag 28(2):153–164

Slavin RE (2002) Evidence-based education policies: Transforming educational practice and research. Educ Researcher 31(7):15–21

Stacer MJ, Perrucci R (2013) Parental involvement with children at school, home, and community. J Fam Econ Issues 34:340–354

Stephan A (2021) Intergenerational learning in the family as an informal learning process: A review of the literature. J Intergenerational Relatsh 19(4):441–458

Strom RD, Strom SK (2000) Intergenerational Learning and Family Harmony. Educ Gerontol 26(3):261–283

Su C, Lee C, Shinger H (2014) Effects of involvement in recreational sports on physical and mental health, quality of life of the elderly. Anthropologist 17(1):45–52

Taneja H, Wu AX, Edgerly S (2018) Rethinking the generational gap in online news use: An infrastructural perspective. N Media Soc 20(5):1792–1812

Tang F, Li K, Jang H, Rauktis MB (2022) Depressive symptoms in the context of Chinese grandparents caring for grandchildren. Aging Ment Health 26(6):1120–1126

Teater B, Chonody JM (2020) What attributes of successful aging are important to older adults? The development of a multidimensional definition of successful aging. Soc Work Health Care 59(3):161–179

Temple JB, McDonald PF (2017) Population ageing and the labour force: 2000–2015 and 2015–2030. Australas J Ageing 36(4):264–270

Torku A, Chan APC, Yung EHK (2021) Age-friendly cities and communities: A review and future directions. Ageing Soc 41(10):2242–2279

Trujillo-Torres JM, Aznar-Díaz I, Cáceres-Reche MP, Mentado-Labao T, Barrera-Corominas A (2023) Intergenerational Learning and Its Impact on the Improvement of Educational Processes. Educ Sci 13(10):1019

Tuohy D, Cassidy I, Graham M, Mccarthy J, Murphy J, Shanahan J, Tuohy T (2023) Facilitating intergenerational learning between older people and student nurses: An integrative review. Nurse Edu Pract. 103746

Twum-Antwi A, Jefferies P, Ungar M (2020) Promoting child and youth resilience by strengthening home and school environments: A literature review. Int J Sch Educ Psychol 8(2):78–89

Valli L, Stefanski A, Jacobson R (2016) Typologizing school–community partnerships: A framework for analysis and action. Urban Educ 51(7):719–747

Van Orden KA, Bower E, Lutz J, Silva C, Gallegos AM, Podgorski CA, Conwell Y (2021) Strategies to promote social connections among older adults during “social distancing” restrictions. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 29(8):816–827

Wanchai A, Phrompayak D (2019) Social participation types and benefits on health outcomes for elder people: A systematic review. Ageing Int 44(3):223–233

Weber M (2017) Methodology of social sciences: Routledge

Wright G, Smith E (1998) Home, School, and Community Partnerships: Integrating Issues of Race, Culture, and Social Class. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 1(3):145–162

Wu M-Y (2022) Fostering resilience: Understanding generational differences in information and communication technology (ICT) and social media use. J Commun Technol 5(2):30–52

Xu Q, Perkins D, Chow J (2010) Sense of community, neighboring, and social capital as predictors of local political participation in China. Am J Community Psychol 45(3-4):259–271

Xu W, Zammit K (2020) Applying Thematic Analysis to Education: A Hybrid Approach to Interpreting Data in Practitioner Research. Int J Qualitative Methods 19:1–9

Yang EZ, Kotwal AA, Lisha NE, Wong JS, Huang AJ (2021) Formal and informal social participation and elder mistreatment in a national sample of older adults. J Am Geriatrics Soc 69(9):2579–2590