Abstract

This study investigates the role of country-level and individual-level factors on climate change risk perception in 28 European countries. Based on the nature of the data and the research question, a multilevel ordered logit model is used. As individual observations are nested among countries, the data is hierarchical, justifying the use of a multilevel model. The analysis focuses on a dependent variable with ordered categories. Due to its inherent ordinal structure, the response levels convey a meaningful order. The ordered logit model explicitly considers this ordinal nature when modeling the dependent variable. On the country level, this study found that climate change risk perception rises with a higher level of income per capita and a lower level of regulatory quality. The positive effect of the national income level persists after controlling for whether the country had a communist regime past or not. On the individual level, this study found that a higher level of climate change risk perception is exhibited by more educated individuals, those with egalitarian and post-materialistic values, those with a higher interest in politics, and a lower level of personal economic worries. Overall, females express higher levels of climate change risk perception than males, but having younger children at home reduces females’ risk perceptions. Similarly, climate change risk perception levels decrease with age only for women. A series of robustness checks validate the main findings. The research suggests that EU policymakers can enhance climate policies and public engagement by considering differences in income, regulatory quality, historical context, and gender-specific aspects. Insights from this study can guide targeted risk communication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is broad scientific agreement among scientists regarding the urgency of acting against climate change. Numerous effects of climate change have been well documented in the last decades; for instance: rising temperatures, an increase in the salinity and acidification of oceans, and an increase in the temperature of the seas (IPCC 2014). Consequently, taking individual and societal action to mitigate climate change effects has become critical.

Understanding public attitudes towards these impacts and their driving factors is therefore crucial for effective policy formulation (Baiardi and Morana 2021). This is because, in democratic societies, the acceptance of political choices concerning climate change mitigation measures relies on the backing of public opinion. Consequently, public endorsement of these measures will only arise when there is adequate recognition of the ecological, financial, societal, and human consequences associated with such actions.

Several studies found that individual actions might significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Examples are purchasing better (environmentally friendly) products rather than more products and changing diets and travel modes. Grouping products into five primary consumption categories, actions that would lead to the lowest greenhouse gas intensity are consuming local vegetables not grown in heated greenhouses, purchasing products based on renewable energy-intensive production processes, using railways as a means of transportation, and adapting housing to become more energy efficient (Girod et al. 2014).

Arousing people’s attention or increasing their perception of climate change is critical in bringing about behavioral change (Chan and Tam 2021) as higher risk perceptions would make people take better and more effective climate change mitigation actions (Wang et al. 2021). People who perceive climate change as a threat to their lives are more inclined to adopt mitigation measures (Alvi et al. 2020). Climate change risk perception (CCRP) is the cognitive dimension of climate change concern. It is an active process (Alvi and Khayyam 2020) and it can be defined as the personal assessment of the likelihood and severity of the negative impacts of climate change (Lo and Chow 2015; Wang et al. 2021).

For policymakers to take action, a necessary condition is that society perceives the risks of climate change (Sandvik 2008), as more risk perception will bring higher demand for political action (Kvaløy et al. 2012) and will increase the likelihood of the adoption of necessary policies (Bromley-Trujillo and Poe 2020) which is particularly relevant in the case of European countries as government policies are largely influenced by the public opinion (Crawley et al. 2020).

As such, studying the individual and society-level determinants of CCRP is important as it will allow an understanding of how the level of risk perception in societies can be increased. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the determinants of climate change risk perception at both individual and societal levels, to pinpoint leverage points for boosting public engagement with climate policies for 28 EU member countries. While on the country level we analyze the effect of income per capita, regulatory quality, and a communist regime past, on the individual level, apart from sociodemographic control variables found to be relevant by the literature, we also consider values and socioeconomic factors.

Since we have country-level and individual-level variables, we run a multilevel ordered logit regression model. We also run the regressions separately for both genders to see whether the CCRP of women and men are affected by different factors.

This study finds that, on the country level, a higher income per capita implies a higher level of CCRP, while the effect of regulatory quality goes in the opposite direction. The positive effect of income remains robust after taking into account whether a country had a past communist regime or not. While the degree of CCRP declines with age for women, this is not the case for men. Similarly, having younger children at home only reduces the level of CCRP in females.

The findings imply that for policymakers in the EU, understanding income disparities, regulatory quality, historical context, and gender-specific factors can inform effective climate policies and enhance public engagement. They can use insights from this study to design targeted risk communication. Policymakers at the EU level should recognize historical legacies and tailor policies accordingly. For instance, countries with communist histories may require specific messaging to overcome skepticism related to state intervention.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. The next section presents the related literature and outlines the theoretical background on which this study is based. It also outlines our contributions. “Data, Variables, and Methodology” describes the study region, data, variables, and methodology used. Our results are presented in “Results”, “Discussion and Limitations of the Study“ discusses the main findings and outlines some limitations of the study, and the last section provides our concluding remarks and policy recommendations.

Literature review and theoretical background

In our analysis, we use CCRP as our dependent variable. However, since only a few studies focus on the determinants of CCRP, in what follows, we review the literature focusing on different dimensions of climate change and global warming concerns.

We first focus on the theoretical background and empirical findings of the literature analyzing similar country-level factors as our study. Then, we present the findings concerning individual-level factors. The literature has established that several social and demographic factors affect environmental and climate change concerns and risk perception. Therefore, we first present the findings regarding these factors as we include them as control variables in our analysis. Then, we review the findings on the effects of socioeconomic factors and values.

Country-level factors

Per capita income level

The affluence or prosperity hypothesis posits a positive relationship between national affluence and the level of environmental concern (Diekmann and Franzen 1999; Franzen and Meyer 2010) as higher levels of wealth would lead to a higher demand for a better environment which can be motivated by the public good nature of the quality of the environment. Higher income levels would lead to a higher demand for public goods (Baiardi and Morana 2021). This hypothesis is also in line with the theory of post-materialism (Inglehart 1977), which suggests that as individuals and societies become more affluent, they value more non-material objectives, such as the quality of the environment (Inglehart 1990).

On the other hand, Sandvik (2008), based on past research on the psychology and sociology of denying ‘uncomfortable truths’, argues that richer countries, which are also the largest contributors to climate change due to their larger amount of emissions, will be less convinced of the existence of global warming. This is what Lo and Chow (2015) call an ‘informed ignorance of a known threat’, a reduced sense of risk may be the outcome of realizing one’s own contribution to the problem.

Even if citizens of wealthier countries are not necessarily more inclined to deny climate change, they may be less concerned as they may feel that they have more influence over the effects of climate change. This stems from the fact that wealthier nations are better prepared to manage or prevent the negative effects of climate change (Nauges et al. 2021). That is, a country´s better adaptive capacity to the negative effects of climate change may cause people not to consider the risk to be substantial (Lo and Chow 2015).

The empirical evidence is also mixed. While Duijndam, van Beukering (2021), and Baiardi and Morana (2021) found a positive relationship between per capita income level and climate change concern and CCRP, respectively, other studies did not find any significant relationship between income level and different measures of climate change concern or risk perceptions (Droste and Wendt 2021, for climate change concern; Mostafa 2017, for global warming concern and Kvaløy et al. 2012 for global warming seriousness perception). In several studies where the dependent variable is CCRP or global warming risk perception, the effect was found to be negative (Lo and Chow 2015; Sandvik 2008; Sohlberg 2017). These seemingly conflicting findings are likely to be the result of several factors such as the set of countries included in the study, the hierarchical structure of the data, the methodology used to analyze the data, and the other variables included in the analysis.

Regulatory quality

Güngör et al. (2021) found that regulatory quality has a negative effect on the ecological footprint-a measure of environmental degradation- in South Africa. Therefore, one of their policy recommendations is to enhance regulatory laws and institutions to improve environmental quality. Similarly, Mesagan and Olunkwa (2022) found that regulatory quality has a negative effect on pollution in several African countries in the short run and -more strongly- in the long run. Thus, they emphasize the role regulatory quality might have in improving the environmental quality in the region. Regarding climate change, Abdelzaher et al. (2020) claim that innovation, when combined with institutional factors such as regulatory quality, can lessen a nation’s susceptibility to climate change, regardless of other considerations like its geographic limitations. Their results show that countries are less vulnerable to climate change when regulatory quality is higher. In the same vein, Addai et al. (2023) found that countries, where regulations are stronger have better environmental quality.

How well governments manage risks and disasters is one of the key factors in how the public perceives risks (Ma and Liu 2019). We, therefore, argue that the efficacy of mitigation and adaptation strategies may be more widely believed to be effective if the regulatory quality is higher. People may feel that the problem is being addressed and that appropriate steps are being taken to mitigate the risks associated with climate change, which can lead to lower risk perception.

Ex-communist country

Former communist countries in Eastern Europe make up a significant portion of countries with lower-than-average per capita income in the continent. Moreover, environmental concern, environmental attitudes, and climate change concern levels in Eastern Europe are considerably lower than in the Western part of the continent (Chaisty and Whitefield 2015; Droste and Wendt 2021; see also Kenny 2021 for a review). Additionally, McCright et al. (2016) found that the effect of the left-right divide in political ideology on climate change concern and CCRP (higher concern and CCRP among ideologically more leftist individuals) only present in Western European countries but not in former communist European countries. This can be explained by climate change being a less salient political issue in these countries (McCright et al. 2016). Chaisty and Whitefield (2015) point out two reasons for the lower level of concern in former Communist countries. On the individual level, they argue, there is stickiness in former values, which may have persisted due to the adverse experiences caused by the transition and the high level of corruption in the post-transition era. On the political level, in line with McCright et al. (2016), the absence of ideological differences in environmental issues across the left-right political divide resulted in environmental or climate-related issues not being at the center of political discussions.

In light of the above-presented empirical findings and arguments, to ensure that a potential effect of income per capita on CCRP is not (partially) driven by the communist past of Eastern European countries, we also control for this factor in our empirical analysis.

Considering the above-presented theoretical arguments and empirical findings, we expect CCRP to be lower in ex-communist regime countries and countries with higher regulatory quality. In the case of income per capita, due to the somewhat conflicting theoretical arguments and mixed findings of previous empirical studies, we do not have an a priori expectation about the sign of the relationship with CCRP.

Individual-level factors

Control variables

Previous research mainly found that people with higher education levels, females, urbanites, and youngsters, show more climate change concern (Duijndam and van Beukering 2021).

The interplay between age and climate change concern is a subject of ongoing research and debate. Scholars have explored various theoretical explanations and empirical findings to understand how age influences attitudes toward environmental issues. The most widely provided theoretical expectation is a negative one explained by a cohort effect, i.e., the fact that newer generations have been growing up in a period where there is more media attention to the problem (Franzen and Vogl 2013) as well as the inclusion of the problem into formal education (Stevenson et al. 2014). Consequently, they tend to exhibit greater awareness and concern about climate change. Moreover, there is also a potential life cycle effect (Kanagy et al. 1994) as people’s value orientations may transform over their life span (Poortinga et al. 2019). However, empirical findings do not provide a clear-cut picture. While many studies found a negative relationship between age and climate change concern with younger individuals expressing higher levels of concern (Duijndam and van Beukering 2021; Hamilton 2011; Lucas, 2018; McCright et al. 2016, among others), a few studies, such as Mostafa (2017) and Sohlberg (2017) did not find any significant relationship. On the other hand, Ergun and Rivas (2019) found a positive relationship between age and climate change concern in Turkey.

Exploring the impact of parenthood on an individual’s perception of climate change risks, it is observed that becoming a parent ‘is an overwhelming experience that affects an individual’s emotional responses to risks, which could influence parents’ worries about external risks such as climate change’ (Ekholm 2020, p. 288). As such, parents are expected to show higher climate change concern and CCRP. Research in this area has produced varied results. While some studies found a positive effect of parenthood on climate change concern (Ekholm and Olofsson 2017; Ekholm 2020; Ergun and Rivas 2019) or CCRP (Nauges et al. 2021), others such as Duijndam and van Beukering 2021 did not find a significant relationship. Interestingly, Droste and Wendt (2021) found a negative relationship between having children and climate change concern.

Education’s role in shaping perceptions and concern about climate change has been a subject of considerable interest in recent research. Numerous studies, including those by Aasen (2017), Droste and Wendt (2021), Duijndam and van Beukering, 2021, and Kvaløy et al. (2012), have found a positive correlation between education and concern about climate change and global warming. This correlation extends to CCRP, with Sohlberg (2017) finding a positive relationship with education. The prevailing theory suggests that individuals with a higher level of education are more likely to grasp the complex challenges presented by climate change, leading to increased concern and risk perception (Gelissen 2007). Education can provide individuals with a deeper understanding of the ecological processes and human activities that contribute to climate change, thereby fostering a greater sense of urgency and concern.

However, this consensus is not universal. Some studies, such as those by Ekholm (2020) and Nauges et al. (2021), have found no significant correlation between education and climate change concern or CCRP. This suggests that the relationship may be more complex than initially thought, with other factors potentially at play. Nonetheless, recent research conducted in the UK by Liu et al. (2022) supports the majority view, finding that increased education correlates with increased concern about climate change.

Another control variable used in this study is gender since extensive research has explored its effect on climate change concern. The differences in their social roles and socialization have been considered the two main explanations for why females show more climate change concern than men (McCright 2010; Franzen and Vogl 2013). Since men and women differ in their socialization, women are expected to care more about others and to be more compassionate and caring, and therefore, should show more climate change concern (McCright 2010). Additionally, women often serve as primary caregivers in many societies, directly experiencing environmental challenges such as water access, food security, and health. These experiences could foster a deeper concern for environmental sustainability and resilience. Such a greater climate concern than men (Aasen 2017; Droste and Wendt 2021; Ergun et al. 2021, McCright 2010; Poortinga et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2022; among several others), as well as larger CCRP (Ekholm 2020; Nauges et al. 2021; Sohlberg 2017), has been empirically verified. However, a few studies found no significant difference in climate concern levels between men and women (Duijndam and van Beukering 2021; Lucas 2018).

In a recent study, Bush and Clayton (2023), found that the gender discrepancy in climate change concern varies significantly between wealthy and poor countries. While women in wealthier nations express heightened concern compared to men, this gender difference is not observed in less prosperous countries. The study introduces a novel hypothesis, suggesting that the gender gap stems from differences in how individuals perceive the costs and benefits associated with climate change mitigation. Specifically, men in wealthier countries tend to perceive greater material and psychological costs, which subsequently diminishes their level of concern regarding climate change.

We also include as a control variable whether the respondent lives in an urban area or not. Although in the case of the location of residence, on a global level, the findings are rather mixed (see Ergun et al. 2021, for a review), studies focusing on Western countries either found that urban residents show higher climate change concern or CCRP than their rural counterparts (Duijndam and van Beukering, 2021; Echavarren et al. 2019) or did not find any significant difference (Droste and Wendt 2021; Nauges et al. 2021).

Socioeconomic factors and values

As outlined above, national income per capita has been considered a factor explaining cross-country differences in climate change concern. In a similar vein, personal or household income has been hypothesized to be a factor explaining individual-level differences in concern as well as risk perceptions. The most prominent theoretical argument favoring a positive relationship between personal income/wealth and climate change concern is the ‘finite pool of worries’ hypothesis (Weber 2006), which posits that people cannot worry about too many issues simultaneously: the emotional capacity of humans to worry is limited; therefore, an increase in worry about a particular threat can lead to a corresponding decrease in worry about other threats. As such, when people have more economic worries, they are less likely to worry about climate change. A second explanation for a positive relationship between personal affluence and climate change concern is based on considering the environment as a public good. More affluent people would demand more public goods and show more environmental and climate change concerns (Franzen and Vogl, 2013). On the other hand, Droste and Wendt (2021) argue that it is conceivable that financial difficulty may act as an amplifier of a higher level of general concern such that individuals dealing with financial difficulties would consider dealing with the consequences of climate change as more difficult. Slovic (2000) posits that risk perceptions are linked to people’s capacity to deal with those risks. As more affluent people will have a higher capacity to deal with adverse events, a higher level of personal income or wealth ‘could lead to an increased sense of control about the world and future outcomes, reduced sense of personal vulnerability’ (Nauges et al. 2021, p. 16483) and hence, it could lead to lower CCRP. The empirical findings reflect these somewhat conflicting arguments. While some studies found a positive effect of a higher personal/household income level on environmental concern (Franzen and Vogl 2013; Gelissen, 2007, among others), Droste and Wendt (2021) found a negative effect of suffering financial difficulties on climate change concern. In the case of CCRP, while Frondel et al. (2017) and Nauges et al. (2021) found a negative effect of household income, Sohlberg (2017) did not find any effect of household wealth.

While personal income and wealth have been associated with climate change concern, individuals’ engagement with political information and interest in politics also play a role in shaping individuals’ perceptions of climate risks. Mildenberger and Leiserowitz (2017) observe that changes in people’s beliefs about climate change are related to changes in political cues. Individuals with a stronger ideological identity are more willing to react to political cues (Malka and Lelkes, 2010). As such, individuals with more interest in politics, being more knowledgeable about politics, and having a larger citizen involvement (Prior, 2010) may differ in their level of CCRP from those with less interest. On the one side, Melis et al. (2014) found that interest in politics is one of the factors that offset the decrease in environmental concern over time. In the same direction, Kvaløy et al. (2012) found a positive relationship between interest in politics and global warming concern. On the other hand, Carrus et al. (2018) observed that, in the US, the effect of conservatism on climate change denial is stronger for those with a higher interest in politics. However, climate change seems to be an issue with less political polarization in Europe compared to the US (Crawley et al. 2022; McCright et al. 2016).

Previous research also focused on the role of certain worldview values on the level of climate change concern or CCRP. People with egalitarian values consider industry and trade as causes of inequality in societies and therefore are more prone to perceive the environmental risks such activities create (Xue et al. 2014). A positive association between more egalitarian values and climate change concern (Aasen, 2017), environmental risk perception (Xue et al. 2014), and CCRP (Leiserowitz 2006) have also been empirically established.

Regarding post-materialist values, -i.e. prioritizing self-expression and quality of life while placing less emphasis on economic prosperity and physical safety-, it is theorized that people holding such values would show higher concern for the environment as higher economic welfare would not be the priority anymore (Franzen and Vogl 2013). Post-materialist values have been found to be positively related to global warming concern (Mostafa 2016), climate change concern (Ergun and Rivas 2019), as well as global warming seriousness perception (Kvaløy et al. 2012).

Based on the theoretical arguments and empirical evidence presented above, we expect being female, being a parent, living in an urban area, having received more education, being younger, and having egalitarian and post-materialistic values to be factors leading to higher CCRP. On the other hand, for the personal affluence level and interest in politics, we do not have a-priori expectations about their correlation with CCRP.

Our paper contributes to the literature in a few directions. First of all, although a considerable volume of literature focuses on the determinants of climate change concern, the amount of research focusing on CCRP is relatively reduced. We aim to contribute to this stream of literature. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study analyzing the effect of regulatory quality on CCRP. This novel approach adds a new level of insight and comprehension to the field of CCRP.

Ours, as far as we are aware, is also the first study to use a panel of countries to analyze the differences in the determinants of CCRP between men and women. This cross-national comparison analysis offers a more comprehensive knowledge of gender differences in CCRP. Although Ekholm (2020) carried out a study with a comparable emphasis, her investigation was restricted to Sweden. Our study, on the other hand, provides a broader global view by expanding the reach beyond a single nation.

Finally, to the best of our knowledge, our analysis is the first to take into account how CCRP is impacted by a nation’s past as a communist country. This particular aspect of our study tries to understand whether historical political contexts can shape CCRP.

To sum up, our research fills in several gaps in the literature by focusing on a relatively understudied topic (CCRP), adding new factors (such as regulatory quality and status as an ex-communist country), and extending the geographic reach of Ekholm (2020). By doing this, we intend to offer a more comprehensive explanation of CCRP.

Data, Variables, and Methodology

Study region

This study uses data from 28 European countries: the 27 European Union member states and the United Kingdom. That is, the countries included in this study are Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Republic of Cyprus, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. As such, the study includes almost all Western European countries except Norway, Switzerland, and very small states such as San Marino or Andorra, and it also includes many of the Eastern European countries. Figure 1 depicts the countries included in the study on a map.

Data

We use the 91.3 Eurobarometer survey (2019). This wave of the survey has two special topics: the rule of law and climate change. The study was conducted by Kantar Public Brussels at the request of the European Commission. The universe is the citizens of the European Union member states and other EU nationals living in any of the 28 (then) member states and aged 15 years and over (European Commission, Brussels 2019). The sample size consists of around 1000 individuals for each of the 28 countries. The sampling procedure followed was multi-stage stratified random sampling. In every country, several sampling locations were selected based on the probability proportional to both population size and population density. The data was collected through computer-assisted face-to-face interviews. A post-stratification method is used to compare between the composition of the sample and the universe. (European Commission, Brussels 2019).Footnote 1

Variables

The set of factors comprises variables at the individual level from the Eurobarometer survey and variables at the country level from different sources (see Note to Table 1). Table 1 describes the variables included in the analysis, and Table 2 presents the main descriptive statistics of these variables.

We consider the variable concerning freedom of speech to be a proxy for the level of post-materialistic values of an individual. Since respondents were not asked about their income or wealth in the survey, we used a question focusing on the difficulty of paying bills as a proxy for personal affluence.

For the dependent variable and the continuous individual-level independent variables, we present the frequency distributions in the histograms below.

Upon reviewing Table 2 and Figs. 2 to 5, it appears that we do not have a strong departure from normality nor any significant outliers.

Methodology

The nature of the data and the research question at hand were the factors in the decision to use the multilevel ordered logit model in this study. Hierarchical models allow us to take into consideration group differences and data dependencies. This is especially helpful when the data is organized in a way that observations are categorized into hierarchies or clusters (e.g., employees within corporations, and students within schools). With individual observations nested among countries, our data is hierarchical. Standard regression models assume independence of observations, which is broken by this structure, producing estimates that are biased and inefficient. The reason is that people who belong to the same group—in this case, the same country—are closer or more alike than people who belong to other groups or nations. Group-level effects can be estimated using hierarchical models, which can offer important insights into how group dynamics affect individual results (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002).

In our study, we deal with a dependent variable that has ordered categories that go from 1 to 10. Because of their innate ordinal structure, the response levels imply a meaningful order, signifying gradations as opposed to continuous values. Regressions using ordinary least squares (OLS) assume linearity and consider the dependent variable as though it were measured on an interval or ratio scale. Biased parameter estimations and inaccurate significance tests may result from using OLS on ordinal data. In contrast, this ordinal aspect is explicitly taken into account by the ordered logit model. We can prevent erroneous conclusions about the influence of predictors and achieve more significant outcomes by maintaining the hierarchy of categories (Nawaz et al. 2022; Williams and Quiroz 2020).

Following Ahn et al. (2016), the equations below describe the multi-level ordered logit model used in the analysis. The Level 1 model includes individual-level variables while the Level 2 model includes the country-level variables: LGDPpc, the level of regulatory quality, and the communist past of the country.

Level 1 model:

Level 2 model:

where \({Logit}({{CCRP}}_{{ijm}})\) is the logit transformation of CCRP with the value of m (m = 1, 2, …, 10) for the ith individual in the jth country and \({X}_{{ij}}\) represents the individual-level control variables.

Following Hill et al. (2018), we briefly explain below the latent variable nature of the ordered logit model (OLM). OLM considers a latent variable which is modeled as:

where \({Z}_{j}\) are the country-level variables and \({W}_{{ij}}\) are all the individual-level variables. The variable CCRP takes different values depending on the values taken by the latent variable (CCRP*) in the following way:

where \({k}_{m}\) denote the nine thresholds to be estimated jointly with the other parameters. In the ordered logit model, F(.) is the logistic function: \(G\left(q\right)=\frac{{e}^{q}}{1+{e}^{q}}\).

We run three models. The first one includes two country-level variables, GDP per capita and regulatory quality, and the individual-level control variables. The second and third models include all the individual-level variables. The difference lies in the country-level determinants. Model 2 includes LGDP pc and Regulatory quality. Model 3 adds the dummy variable that indicates whether the country had a communist regime in the past. In all the models, we correct for heteroscedasticity. After running the models for the whole sample, we run the regressions for men and women separately.

Results

Figure 5 shows the average level of CCRP per country. The countries were ordered from lowest to highest average CCRP, with Estonia in the lower (6.72) and Malta in the upper end (8.76).

Table 3 presents the regression results for the whole sample, while Table 4 shows the results for males and females separately. Both tables include also the AIC, BIC, and the Pseudolikelihood values of all the models. They indicate that as more variables are added to the model, it can explain the data more efficiently. To check whether our model may suffer from a multicollinearity problem, we calculated the Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) which are reported in Table A1 (in the Appendix) for Model 3, the complete model. The low values obtained imply that multicollinearity is not a concern in our model.

The regression results in Table 3 indicate that GDP per capita has a positive effect on CCRP, meaning that countries with higher per capita income show more perception of the risks associated with climate change. As reflected by Model 3, this relationship remains significant even when we control for the communist past of Eastern European countries. The smaller magnitude of the coefficient in Model 3 indicates that omitting the ex-communist country variable from Model 2 led to an overestimate of the effect of country-level income per capita on CCRP. In line with our expectations, CCRP is lower the higher the degree of regulatory quality.

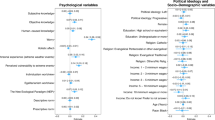

On the individual level, in accordance with our expectations, we find that more educated individuals, females, individuals with egalitarian values, and those who value freedom of speech more (our proxy for post-materialistic values) express a higher level of CCRP. On the other hand, based on empirical evidence and theoretical considerations, we conjectured that younger individuals, urbanites, and parents of younger kids would show higher levels of CCRP, but we failed to obtain a significant effect of these variables on CCRP.

We also find a positive relationship between interest in politics and CCRP while having difficulties in paying bills affects CCRP negatively.

Between Model 1 and Model 2, several observations are omitted due to the presence of missing data. From the analysis of Table 3, it becomes clear that the missing values do not significantly influence our results. The absence of substantial differences in the regression results between Models 1 and 2 implies that the exclusion of missing data does not cause a significant problem. The only variation is observed in the significance level of the variable indicating the area of residence. A plausible explanation for this variation could be the correlation between the socioeconomic and value variables and the residential area. Conducting tests of difference in means, we observe that the mean values of all these variables are larger for urban residents compared to rural ones. Consequently, the exclusion of this group of variables affects the significance level of the location variable.

To further investigate this issue, we conducted the same regressions as those in Table 3, but with the imputation of missing data. For continuous variables, we used mean imputation and for dummy variables, we created an extra category and included it in the regression. Table A2 in the Appendix presents the results. The outcomes are almost identical to those in Table 3, thereby confirming that the exclusion of missing data does not pose a significant concern.

Moreover, we run a series of robustness checks. First, we redefined our dependent variable to consist of 3 (CCRP3) and 4 categories (CCRP4), respectively, instead of 10 as in the original models. The creation of categories was based on the frequency distribution of the survey responses on CCRP which can be seen in Fig. 2. The estimates for the case of three categories are reported in Table A3 and the results for four categories are represented in Table A4 in the Appendix. The results are almost identical to those in Table 3 above, confirming the robustness of our findings. We also run an ordered logit model with errors clustered at the country level (Table A5, in the Appendix). Once again, the results are very similar to our original models. The only difference to be noticed is that in Model 3, the effect of GDP per capita is not significant at 5% anymore.

Regarding the comparison between the determinants of CCRP for men and women, Table 4 shows no differences when considering the country-level variables: Each country-level variable has a statistically significant effect on CCRP with the same sign for both men and women. The same happens with the effect of education, personal economic situation, interest in politics, and values on CCRP.

Nonetheless, we find some differences regarding the individual-level controls. When considering the whole sample (Table 3), Age is not a significant covariate (at a 5% significance level), but it has a significant negative effect for (only) women. This means that older women exhibit lower CCRP than younger ones. Moreover, we find that having children under 15 years of age at home has a negative effect on CCRP for the female subsample.

Finally, living in an urban area positively affects CCRP in the case of men but not women (in Models 2 and 3, for men, the p-value is only slightly above 0.05).

Discussion and Limitations of the Study

Figure 6 below shows graphically the relationship between the independent variables and CCRP. The absence of a line implies that the variables are not related to CCRP. The sign of the relationship is shown with a “+” or “-” for a positive or negative relationship, respectively.

We find that a higher per capita income is associated with higher levels of CCRP. This finding is in line with previous findings such as Duijndam and van Beukering (2021) and Baiardi and Morana (2021). Moreover, this positive relationship persists even after controlling for the communist regime past. The fact that countries with such a past have lower levels of CCRP suggests that EU-level policymakers should tailor policies accordingly.

Our finding that CCRP is lower in countries with higher levels of regulatory quality might be because people living in these countries are more confident about the efficacy of their countries’ mitigation and adaptation strategies.

On the individual level, we fail to find a statistically significant relationship between age and CCRP. As such, our study fails to provide evidence of the cohort effect (Franzen and Vogl 2013) nor the life cycle effect hypotheses (Kanagy et al. 1994). As mentioned in “Literature review and theoretical background“, the primary reasons why women exhibit greater concern about climate change compared to men are attributed to differences in their social roles and socialization (McCright 2010; Franzen and Vogl 2013). Our finding provides further empirical support to these arguments.

Our findings concerning the positive relationship between CCRP and egalitarian and post-materialist values confirm previous findings in the literature (Leiserowitz 2006; Kvaløy et al. 2012, among others). This is also the case for the positive link between education and CCRP (Duijndam and van Beukering (2021); Sohlberg (2017), among others).

Given the contradicting results found in previous studies, we had no a-priori expectations about the effect of personal affluence level and interest in politics on CCRP. Regarding the personal economic situation -captured by the difficulties the individual had to pay the bills in the last 12 months- we find that it has a negative effect on CCRP, meaning that people who must deal with financial difficulties at home show lower levels of CCRP. This finding aligns with the ‘finite pool of worries’ hypothesis and the consideration of the environment as a public good, as explained in “Literature review and theoretical background”. Regarding interest in politics, our findings suggest a positive effect on CCRP, in line with Kvaløy et al. (2012), Melis et al. (2014), and Prior (2010).

Focusing on the comparison between the determinants of CCRP for men and women, we obtain that older women exhibit lower CCRP than younger ones. Considering the finding that women show a higher level of CCRP than men and that younger women have a higher level than older ones, we can argue that the gender difference -in favor of women- is driven by the larger difference between the younger population. The difference in CCRP levels is not so considerable for older men and women.

Furthermore, our research indicates that having children under 15 residing at home reduces CCRP for the female subsample. Droste and Wendt (2021) suggest that when individuals become parents, their attention is primarily directed toward immediate responsibilities, such as meeting the needs of their children, rather than long-term issues like climate change. Given our findings, we can argue that having young children at home directs the attention of women -and not men- to short-run issues. A person can only worry about a small number of issues, according to Weber’s ‘finite pool of worry’ hypothesis (Weber 2006). As such, it may be reasonable to expect women with children to be more worried about the day-to-day problems of their children rather than risks such as climate change that may be perceived as problems of a relatively more distant future. Our findings contrast those of an earlier study by Ekholm (2020) for Sweden. She found that males who are also parents express more CCRP than those who do not have children, while for females having children does not affect the level of CCRP. She explains this finding by the fact that Swedish men have more responsibility and spend more time with their children because of public policy on childcare. We do not find such a positive effect of having children at home on CCRP for men. This may be the case because public policy-driven gender equality in terms of childcare is not as high in the rest of the European continent compared to Sweden.

We find that living in an urban area rather than in a rural area implies higher levels of CCRP for men but not for women. One possible explanation for this finding may be potential interaction effects between gender and urban/rural living that affect risk perception. For example, perhaps living in an urban area affects men and women differently due to varying exposure to information, social networks, or cultural norms.

Our analysis is not without limitations. Backed by theoretical considerations, previous studies and ours found a positive effect of personal income level on CCRP. However, this positive relationship is not a unanimous finding which may be the result of several factors. On the one side, diverse proxies such as household net income, household income divided by the square root of household size, and subjective evaluation of financial hardship/well-being have been used in the literature. On the other side, including personal or household income as a variable often leads to the loss of a considerable number of observations (Franzen and Vogl 2013). Moreover, in surveys, people often provide lower reported personal incomes than their actual earnings (Franzen and Vogl 2013).

In our case, the proxy we used for personal income level is far from perfect but was imposed by the survey’s limitations in terms of data availability. On the positive side, it is a measure where it is relatively unlikely that respondents misreport. On the other hand, it only allows us to group individuals as having economic difficulties or not. As such, one should be careful about the interpretation or practical significance of our finding. To obtain a clearer picture of the role of personal income level on CCRP, an interesting step that could be taken in further studies is to include an objective and verifiable measure of personal income that would consider not only cross-country purchasing power differences but also a person’s or household’s income relative to the income distribution in the society.

We found that CCRP is lower if regulatory quality in the country is higher arguing that people may feel that the problem is being addressed and that appropriate steps are being taken to mitigate the risks associated with climate change. It is possible though that such a feeling might be driven by perceptions of regulatory quality rather than an objective measure. As such, studying the effect of perceptions of regulatory quality at an individual level could be another step to take.

Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Between 2010 and 2019, the average yearly emission of greenhouse gases worldwide reached unprecedented heights, yet the pace of increase has decelerated. However, if prompt and substantial reductions in emissions across all industries are not implemented, achieving the goal of keeping global warming below 1.5 °C will be unattainable (IPCC 2022). In the words of the IPCC chair, ‘We are at a crossroads. The decisions we make now can secure a liveable future.… There are policies, regulations, and market instruments that are proving effective. If these are scaled up and applied more widely and equitably, they can support deep emissions reductions and stimulate innovation’ (IPCC 2022).

As outlined by Wang et al. (2021), a high level of CCRP in society is fundamental to fostering broad public involvement and public backing for impactful climate policies, as public support is crucial for the implementation of the necessary mitigation and adaptation policies. As such, it is important to analyze both the individual-level and society-level determinants of CCRP. For this reason, we conducted a multilevel analysis of CCRP in 28 European countries where our main purposes were to study the effect of regulatory quality and per capita national income levels controlling for the possible countries’ communist regime past on the country level and the differences in individual-level factors between women and men.

Our analysis shows that higher GDP per capita increases awareness of climate change risks. It is interesting to note that this positive effect remains significant even after considering the communist past of Eastern European countries. Additionally, we find that higher regulatory quality leads to decreased levels of climate change risk perception. On an individual level, more education, being a woman, holding egalitarian values, and valuing freedom of speech are factors associated with a greater level of CCRP. Conversely, individuals facing financial difficulties exhibit lower levels of CCRP. While age, urban residence, and parenthood do not significantly impact CCRP in the overall sample, our findings suggest that older women tend to have lower CCRP levels than younger women. Moreover, we find that having children under 15 years of age at home has a negative effect on CCRP in females, while it does not affect males’ CCRP.

Based on these findings, several policy recommendations can be made. Promoting economic development and higher income levels can increase awareness and understanding of climate change risks. Governments should focus on initiatives that aim to improve GDP per capita. As outlined before, as CCRP rises, individuals and governments are more likely to take mitigation measures and adapt to climate change. However, such measures must not significantly reduce income levels (Baiardi and Morana 2021), as decreasing income levels would lead to lower risk perceptions and, therefore, lower support for such measures.

Additionally, it is crucial to provide education and awareness programs on climate change, targeting specific demographic groups such as individuals with lower education levels and those facing financial difficulties. These efforts should also consider the gender differences observed, aiming to engage and empower younger women in climate change initiatives.

Considering the finding that having small children at home affects negatively women’s CCRP, it seems clear that there is a need for more research on this topic. Nonetheless, there is room for some policy recommendations regarding parenting and climate change. As Sanson et al. (2018) point out, the world’s rapid transition to a low-carbon future, crucial for its habitability, will bring about substantial changes that require adaptation. To ensure the next generation copes successfully with these massive changes, we must focus on equipping them with the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Parents play a vital role in preparing their children to face these upcoming challenges, therefore the fact that women’s CCRP is lower when they have small children at home is worrisome. It appears essential to have support groups that assist parents -especially mothers- in effectively addressing climate change. Sanson et al. (2018) state that we need initiatives that aim to help parents enhance their own and their children’s abilities in social engagement, adaptation, and citizenship, all with the purpose of tackling climate change. We need to adapt communication strategies to effectively involve women and address their apprehensions regarding climate change without compromising their caregiving responsibilities. This could include highlighting the potential dangers to children’s health and overall well-being.

As mentioned above, a possible future line of research is the study of the different effects that the presence of children has on women and men. Moreover, it seems critical to understand the gender differences in CCRP, especially in young citizens, where the difference seems to be larger.

Data availability

The data for the individual level variables comes from the 91.3 Eurobarometer survey (2019), https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13372, available at https://www.gesis.org/en/eurobarometer-data-service/survey-series/standard-special-eb/study-overview/eurobarometer-913-za7572-april-2019. The GDP per capita data comes from the World Development Indicators database of the World Bank available at World Development Indicators | DataBank (worldbank.org). The Regulatory Quality data come from the The Worldwide Governance Indicators, available at www.govindicators.org. The variable ‘Ex-communist country’ was created by the authors and the data is available upon request.

Notes

The dataset can be downloaded from the following site: https://search.gesis.org/research_data/ZA7572.

References

Aasen M (2017) The polarization of public concern about climate change in Norway. Clim Policy 17(2):213–230

Abdelzaher DM, Martynov A, Zaher AMA (2020) Vulnerability to climate change: Are innovative countries in a better position? Res Int Bus Financ 51:101098

Addai K, Serener B, Kirikkaleli D (2023) Environmental sustainability and regulatory quality in emerging economies: Empirical evidence from Eastern European Region. J Knowl Econ 14(3):3290–3326

Ahn H, Roll SJ, Zeng W, Frey JJ, Reiman S, Ko J (2016) Impact of income inequality on workers’ life satisfaction in the US: A multilevel analysis. Soc Indic Res 128:1347–1363

Alvi S, Khayyam U (2020) Mitigating and adapting to climate change: attitudinal and behavioural challenges in South Asia. Int J Clim Change Strateg Manag 12(4):477–493

Alvi S, Nawaz SMN, Khayyam U (2020) How does one motivate climate mitigation? Examining energy conservation, climate change, and personal perceptions in Bangladesh and Pakistan. Energy Res Soc Sci 70:101645

Baiardi D, Morana C (2021) Climate change awareness: Empirical evidence for the European Union. Energy Econ 96:105163

Bromley-Trujillo R, Poe J (2020) The importance of salience: public opinion and state policy action on climate change. J Public Policy 40(2):280–304

Bush SS, Clayton A (2023) Facing change: Gender and climate change attitudes worldwide. Am Political Sci Rev 117(2):591–608

Carrus G, Panno A, Leone L (2018) The moderating role of interest in politics on the relations between conservative political orientation and denial of climate change. Soc Nat Resour 31(10):1103–1117

Chaisty P, Whitefield S (2015) Attitudes towards the environment: are post-Communist societies (still) different? Environ Politics 24(4):598–616

Chan HW, Tam KP (2021) Exploring the association between climate change concern and mitigation behaviour between societies: A person‐context interaction approach. Asian J Soc Psychol 24(2):184–197

Crawley S, Coffé H, Chapman R (2020) Public opinion on climate change: Belief and concern, issue salience and support for government action. Br J Politics Int Relat 22(1):102–121

Crawley S, Coffé H, Chapman R (2022) Climate Belief and Issue Salience: Comparing Two Dimensions of Public Opinion on Climate Change in the EU. Soc Indic Res 162:307–325

Diekmann A, Franzen A (1999) The Wealth of Nations and Environmental Concern. Environ Behav 31:540–549

Droste L, Wendt B (2021) Who Cares? Eine ländervergleichende Analyse klimawandelbezogener Besorgnis in Europa. Soziologie und Nachhaltigkeit 7(1):1–42

Duijndam S, van Beukering P (2021) Understanding public concern about climate change in Europe, 2008–2017: the influence of economic factors and right-wing populism. Clim Policy 21(3):353–367

Echavarren JM, Balžekienė A, Telešienė A (2019) Multilevel analysis of climate change risk perception in Europe: Natural hazards, political contexts and mediating individual effects. Saf Sci 120:813–823

Ekholm S (2020) Swedish mothers’ and fathers’ worries about climate change: a gendered story. J Risk Res 23(3):288–296

Ekholm S, Olofsson A (2017) Parenthood and worrying about climate change: the limitations of previous approaches. Risk Anal 37(2):305–314

Ergun SJ, Khan MU, Rivas MF (2021) Factors affecting climate change concern in Pakistan: are there rural/urban differences? Environ Sci Pollut Res 28(26):34553–34569

Ergun SJ, Rivas MF (2019) The effect of social roles, religiosity, and values on climate change concern: An empirical analysis for Turkey. Sustain Dev 27(4):758–769. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1939

European Commission, Brussels (2019) Eurobarometer 91.3 (2019). GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA7572 Data file Version 1.0.0, https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13372

Franzen A, Meyer R (2010) Environmental attitudes in cross-national perspective: a multilevel analysis of the ISSP 1993 and 2000. Eur Sociol Rev 26:219–234

Franzen A, Vogl D (2013) Two decades of measuring environmental attitudes: A comparative analysis of 33 countries. Glob Environ Change 23(5):1001–1008

Frondel M, Simora M, Sommer S (2017) Risk perception of climate change: Empirical evidence for Germany. Ecol Econ 137:173–183

Gelissen J (2007) Explaining popular support for environmental protection: A multilevel analysis of 50 nations. Environ Behav 39(3):392–415

Girod B, van Vuuren DP, Hertwich EG (2014) Climate policy through changing consumption choices: Options and obstacles for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Glob Environ Change 25:5–15

Güngör H, Abu-Goodman M, Olanipekun IO, Usman O (2021) Testing the environmental Kuznets curve with structural breaks: the role of globalization, energy use, and regulatory quality in South Africa. Environ Sci Pollut Res 28:20772–20783

Hamilton LC (2011) Education, politics and opinions about climate change evidence for interaction effects. Climatic Change 104(2):231–242

Hill RC, Griffiths WE, Lim GC (2018) Principles of econometrics. John Wiley & Sons

Inglehart R (1990) Culture shift in advanced industrial society. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

Inglehart R (1977) The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles Among Western Publics. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, Princeton, New Jersey

IPCC (2014) Summary for policymakers. In CB Field, VR Barros, DJ Dokken, KJ Mach, MD Mastrandrea, TE Bilir, … LL White (Eds.), Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part A: Global and sectoral aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pp. 1–32). Cambridge/New York, NY: Cambridge University Press

IPCC (2022) The evidence is clear: the time for action is now. We can halve emissions by 2030. https://www.ipcc.ch/2022/04/04/ipcc-ar6-wgiii-pressrelease/

Kanagy CL, Humphrey CR, Firebaugh G (1994) Surging environmentalism: Changing public opinion or changing publics? Soc Sci Q 75(4):804–819

Kenny J (2021) The Evolution of Environmental Concern in Europe. In A Franzen, & S Mader (Eds.), Research Handbook on Environmental Sociology (pp. 79-96). Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781800370456.00013

Kvaløy B, Finseraas H, Listhaug O (2012) The publics’ concern for global warming: A cross-national study of 47 countries. J Peace Res 49(1):11–22

Leiserowitz A (2006) Climate change risk perception and policy preferences: The role of affect, imagery, and values. Clim Change 77(1-2):45–72

Liu T, Shryane N, Elliot M (2022) Attitudes to climate change risk: classification of and transitions in the UK population between 2012 and 2020. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9(1):1–15

Lo AY, Chow AT (2015) The relationship between climate change concern and national wealth. Clim Change 131(2):335–348

Lucas CH (2018) Concerning values: what underlies public polarisation about climate change? Geographical Res 56(3):298–310

Ma L, Liu P (2019) Missing links between regulatory resources and risk concerns: Evidence from the case of food safety in China. Regul Gov 13(1):35–50

Malka A, Lelkes Y (2010) More than ideology: Conservative–liberal identity and receptivity to political cues. Soc Justice Res 23(2):156–188

McCright AM (2010) The effects of gender on climate change knowledge and concern in the American public. Popul Environ 32(1):66–87

McCright AM, Dunlap RE, Marquart-Pyatt ST (2016) Political ideology and views about climate change in the European Union. Environ Politics 25(2):338–358

Melis G, Elliot M, Shryane N (2014) Environmental concern over time: evidence from the longitudinal analysis of a British cohort study from 1991 to 2008. Soc Sci Q 95(4):905–919

Mesagan EP, Olunkwa CN (2022) Heterogeneous analysis of energy consumption, financial development, and pollution in Africa: the relevance of regulatory quality. Uti Policy 74:101328

Mildenberger M, Leiserowitz A (2017) Public opinion on climate change: Is there an economy–environment tradeoff? Environ Politics 26(5):801–824

Mostafa MM (2016) Post-materialism, religiosity, political orientation, locus of control and concern for global warming: A multilevel analysis across 40 nations. Soc Indic Res 128(3):1273–1298

Mostafa MM (2017) Concern for global warming in six Islamic nations: a multilevel Bayesian analysis. Sustain Dev 25(1):63–76

Nauges C, Wheeler SA, Fielding KS (2021) The relationship between country and individual household wealth and climate change concern: the mediating role of control. Environ, Dev Sustainability 23(11):16481–16503

Nawaz SMN, Alvi S, Rehman A, Riaz T (2022) How do beliefs and attitudes of people influence energy conservation behavior in Pakistan? Heliyon 8(10):e11054

Poortinga W, Whitmarsh L, Steg L, Böhm G, Fisher S (2019) Climate change perceptions and their individual-level determinants: A cross-European analysis. Glob Environ Change 55:25–35

Prior M (2010) You’ve either got it or you don’t? The stability of political interest over the life cycle. J Politics 72(3):747–766

Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS (2002) Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (Vol. 1). Sage

Sandvik H (2008) Public concern over global warming correlates negatively with national wealth. Clim Change 90(3):333–341

Sanson AV, Burke SE, Van Hoorn J (2018) Climate change: Implications for parents and parenting. Parenting 18(3):200–217

Slovic P (2000) The perception of risk. Earthscan Publications

Sohlberg J (2017) The effect of elite polarization: A comparative perspective on how party elites influence attitudes and behavior on climate change in the European Union. Sustainability 9(1):39

Stevenson KT, Peterson MN, Bondell HD, Moore SE, Carrier SJ (2014) Overcoming skepticism with education: interacting influences of worldview and climate change knowledge on perceived climate change risk among adolescents. Clim Change 126(3):293–304

Wang C, Geng L, Rodriguez-Casallas JD (2021) How and when higher climate change risk perception promotes less climate change inaction. J Clean Prod 321:128952

Weber EU (2006) Experience-based and description-based perceptions of long-term risk: Why global warming does not scare us (yet). Clim Change 77(1-2):103–120

Williams RA, Quiroz C (2020) Ordinal regression models. SAGE Publications Limited

Xue W, Hine DW, Loi NM, Thorsteinsson EB, Phillips WJ (2014) Cultural worldviews and environmental risk perceptions: A meta-analysis. J Environ Psychol 40:249–258

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have equally contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ergun, S.J., Karadeniz, Z.D. & Rivas, M.F. Climate change risk perception in Europe: country-level factors and gender differences. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1573 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03761-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03761-4

This article is cited by

-

Factors Affecting Smallholders’ Perception of Climate Change in Eritrea

Environmental Management (2026)

-

German Anglers’ Views on Global Warming – Implications for Climate Change Monitoring and Management

Environmental Management (2026)

-

Growing climate change risk concerns with rising regional disparities in China

npj Climate Action (2025)

-

Insights from Youth Daily Life Experience in the Context of Climate Change: An Experience Sampling Method Study

International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology (2025)