Abstract

Research on gender and language is tightly knitted to social debates on gender equality and non-discriminatory language use. Psycholinguistic scholars have made significant contributions in this field. However, corpus-based studies that investigate these matters within the context of language use are still rare. In our study, we address the question of how much textual material would actually have to be changed if non-gender-inclusive texts were rewritten to be gender-inclusive. This quantitative measure is an important empirical insight, as a recurring argument against the use of gender-inclusive German is that it supposedly makes written texts too long and complicated. It is also argued that gender-inclusive language has negative effects on language learners. However, such effects are only likely if gender-inclusive texts are very different from those that are not gender-inclusive. In our corpus-linguistic study, we manually annotated German press texts to identify the parts that would have to be changed. Our results show that, on average, less than 1% of all tokens would be affected by gender-inclusive language. This small proportion calls into question whether gender-inclusive German presents a substantial barrier to understanding and learning the language, particularly when we take into account the potential complexities of interpreting masculine generics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the public and academic debate about gender-inclusive German, a recurring argument against the use of gender-inclusive forms is that they make “a text cumbersome” (Schneider 2020),Footnote 1 that the language “becomes even more complicated and off-putting for foreigners considering to learn German” (Rock et al. 2021)Footnote 2 and that gender-inclusive language makes “texts unreadable and longer”Footnote 3 (Web editorial staff of the LpB BW 2023). Also, the linguistic effort that is necessary and that makes texts “long, monotonous and gender-fixated”Footnote 4 (Eisenberg 2022) is seen as a disadvantage of gender-inclusive language, both in the public debate and among some linguists. However, empirical evidence on the readability of gender-inclusive texts in German shows that gender-inclusive language does not reduce comprehensibility (Braun et al. 2007, Blake and Klimmt 2010, Friedrich and Heise 2019). A rapid habituation effect for gender-inclusive forms has also been shown for French (Gygax and Gesto 2007): The study suggests that reading is temporarily slowed during the initial exposure to inclusive forms. However, with subsequent encounters, the reading speed becomes comparable to that of non-inclusive texts. Speyer and Schleef (2019) show a similar effect for the use of singular they, comparing native speakers and learners of English. Despite these empirical insights, criticism of and resistance to gender-inclusive language continues to be widespread (see section Gender-inclusive language and personal nouns in German). With our corpus-based annotation study, we attempt to empirically assess this ‘challenge’ of gender-inclusive language in German. To the best of our knowledge, there are currently no statistics regarding the extent to which gender-inclusive language would impact German language material if non-inclusive texts were to be re-written. More generally, there is a lack of data on the proportion of text that actually refers to human beings, i.e. that could potentially be subject to gender-inclusive language. There are only a few studies dealing with the quantitative-empirical analysis of personal nouns in written texts from a linguistic perspective, e.g. corpus-based studies targeting linguistic entities that are easy to recognise automatically, such as pronouns, especially in English texts (e.g. Saily et al. 2011, Zeng 2023, cf. also Motschenbacher 2015, 34–35); some studies are enriched with manual analyses (e.g. Baker 2010, Rosola et al. 2023); there is also an increasing interest in the topic in economic disciplines (e.g., for German texts cf. Eugenidis and Lenz 2022). However, even if personal nouns could be detected automatically in the future (cf. Sökefeld et al. 2023 for an initial attempt), the problem of identifying reference would remain unsolved. This is especially relevant for the so-called masculine generic, which is the main focus of gender-inclusive language, and which cannot be distinguished from masculine specifics by mere form (cf., e.g., Schmitz et al. 2023). Manual annotation is therefore necessary for our research question. Our starting points are studies in which German personal nouns are analysed manually and on the basis of small linguistic datasets (e.g. Doleschal 1992, Kusterle 2011, Pettersson 2011). The annotation system for the present study was developed on this basis (cf. section Corpus and source selection). The article is structured as follows: In the section Gender-inclusive language and personal nouns in German, we provide more background information on gender-inclusive language and personal nouns in German. In the Method section, we describe the method of our study, followed by results and discussion in Results & Discussion. We conclude our paper with a brief Conclusion and Outlook.

Gender-inclusive language and personal nouns in German

German is a language with three grammatical genders (masculine, feminine, neuter). There is a mix of semantic and formal regularities to assign grammatical gender to words, but, according to Hellinger and Bußmann, for “approximately 90% of German monosyllabic nouns, gender class membership can be predicted from morphophonological criteria” (2003, 143). Gender assignment of personal nouns, however, requires special attention, as it is often driven by lexical-semantic factors: “The assumption that, in principle, the assignment of a German noun to one of the three gender-classes is arbitrary is unfounded in the field of animate/personal nouns, where explicit relations between grammatical gender and the noun’s lexical specification can be formulated” (Hellinger and Bußmann 2003, 146). We can therefore summarise that the gender assignment of personal nouns often depends on external correlates (Corbett 2013, 1), i.e. the gender of a noun’s referent (McConnell-Ginet 2013, 5).

According to Hellinger and Bußmann (2003, pp. 150–160), when referring to persons in German, we can distinguish between personal nouns that specify referential gender by grammatical, lexical or morphological means:

-

1.

Specification of referential gender by grammatical means: Singular personal nouns in German that are derived from adjectives (like gesund, ‘healthy’) and verbs (studierend, present participle of studieren, ‘to study’; abgeordnet, past participle of abordnen, ‘to delegate’) use the grammatical gender of the articles (e.g. die (f.) Gesunde vs. der (m.) Gesunde) or the adjective inflection (e.g. eine Abgeordnete (f.) vs. ein Abgeordenter (m.)) “to make referential gender explicit or overt” (also called Differentialgenus ‘double gender’; cf. Hellinger & Bußmann 2003 p. 150). Gender specification in these nouns is neutralized in the plural, since articles and other determiners do not vary for grammatical gender in the plural (die Gesunden (m./f.pl.) ‘the healthy’, die Studierenden (m./f.pl.) ‘the students’, die Abgeordneten (m./f.pl.) ‘the delegates’). Some indefinite pronouns can also have this kind of double gender, e.g. keine/jede (f.) vs. keiner/jeder (m.) or keines/jedes (n.; ‘no’/‘each, every’); some others are grammatically invariable and always masculine (so-called generic pronouns like jemand ‘somebody’ or niemand ‘nobody’).

-

2.

Specification of referential gender by lexical means: Gender-specification by lexical means is often realised in compounds that denote occupations and functions, containing the second elements -mann (‘-man’) or -frau (‘-woman’) (like Feuerwehrmann, Feuerwehrfrau, ‘firefighter’). Additionally, there are nouns where referential gender is encoded in the lexical meaning and usually results in lexical pairs, e.g. die Tante ‘aunt’ vs. der Onkel ‘uncle’; die Tochter ‘daughter’ vs. der Sohn ‘son’. In this category, grammatical gender is congruent with extra-linguistic gender. In the following, we call these nouns lexical gender nouns.

-

3.

Specification of referential gender by morphological means: The most prominent way to specify referential gender in German is to use suffixes that make the noun gender-specific. This function is mostly carried out by the feminizing suffix -in which can be attached to most masculine derivation bases (e.g. Arbeiter/Arbeiterin, ‘male/female worker’; Maler/Malerin, ‘male/female painter’) (for more marginal feminizing suffixes, cf. Doleschal 1992, 27–29, Hellinger and Bußmann 2003, 152–153; compare the superficially similar, but functionally different suffix –ess in English, Stefanowitsch and Middeke 2023). There is only a small set of feminine bases that is used to derive masculine terms from feminine ones in the human domain: Braut/Bräutigam (‘bride/bridegroom’) Witwe/Witwer (‘widow/widower’) and Hexe/Hexer (‘witch/witcher’).

As an option to neutralize referential gender in German (besides the use of plural forms of nominalized adjectives/participles), we can use collectives (e.g. society, group, family, etc.) and epicene nouns, i.e. personal nouns with a fixed grammatical gender that can refer to any extra-linguistic gender. These nouns occur in all three grammatical genders (e.g. die Person, f. ‘person’, der Mensch, m. ‘human being’; das Kind, n. ‘child’) (Corbett 1991, 67, cf. Klein 2022).

Resulting from these gender differentiations, German has various kinds of pair forms when denoting humans: a) double gender pairs (e.g. der Kranke/die Kranke, ‘sick person’); b) (asymmetrical) lexical pairs (Krankenschwester/Krankenpfleger ‘nurse/male nurse’; Vater/Mutter ‘father/mother’); c) masculine forms with feminine derivations (e.g. der Arzt/die Ärztin, ‘male/female doctor’). All of these are semantic minimal pairs, i.e. they have the opposing semantic features +male/-female and +female/-male (Diewald 2018, 290–293). Within these pairs, the masculine form usually has two functions: first, as a masculine specific and, second, as a so-called ‘masculine generic’. The term denotes the use of the masculine form to refer to an individual or a group of people whose gender is unknown, irrelevant, or ignored (like Wissenschaftler, ‘scientists’, for a group of scientists). Masculine generics are a common phenomenon in grammatical gender languages when referring to humans of mixed or indefinite sex (Corbett 2013). Parallel to that, there can be feminine generics in German (e.g., referring to all scientists with the feminine term Wissenschaftlerinnen), but these are very rare compared to masculine generics and are often used consciously as a means of gender-inclusive language, e.g. in recent years in the newspaper Die Zeit (Dülffer 2018).

Whether a masculine personal noun refers specifically to a male person or generically to a group or an individual of unknown gender cannot be decided based on the surface form. On the one hand, the masculine and feminine forms of a personal noun like Wissenschaftler (‘scientist’) may be used as semantic minimal pairs to refer to male vs. female individuals. Consider the following context: Das Podium bestand aus drei Wissenschaftlern und einer Wissenschaftlerin. (‘The panel consisted of three male scientists and one female scientist’). In this case, the linguistic category ‘grammatical gender’ reflects the social gender of the extra-linguistic referents (i.e. the masculine form maps onto male referents, the feminine form maps onto female referents). On the other hand, the grammatically masculine terms are also used to refer to mixed groups of people, to people of unknown gender, or in contexts where gender is presumably irrelevant, e.g. in contexts like die Wissenschaftler sind sich bislang nicht einig (‘the scientists [m.pl.] do not yet agree’). Here, grammatical gender is assumed to be a neutral category, i.e. not carrying information about referential gender. The reference of the superficially identical masculine lexemes is only resolved in context, which is why the question of whether a masculine form is used specifically (i.e. to designate individual male referents) or generically (i.e. for indefinite referents or mixed groups) cannot yet be detected automatically (Sökefeld et al. 2023, 38) and must be examined individually for each case (Elmiger et al. 2017, 64).

The use of masculine generics to denote all genders is subject to controversial societal and academic debates (Pusch 1984, Müller-Spitzer 2022a, 2022b, Simon 2022, Trutkowski and Weiß 2023). Proponents of gender-inclusive language usually do not accept it as a gender-neutral way of person reference (Hellinger and Bußmann 2003, 160–161, e.g. Acke 2019, 308). Opponents of new forms of gender-inclusive language, by contrast, consider the masculine generic to be gender-neutral ’by default’ (sometimes based on Becker’s assumption of conversational implicatures, cf. Becker 2008; or based on Jakobson’s concept of markedness, cf. Eisenberg 2020, Meineke 2023, or on selective historical data, cf. Trutkowski and Weiß 2023). However, many psycho- and neurolinguistic studies find that the so-called masculine generic is not always understood neutrally but rather activates a male bias (e.g., Gygax et al. 2008, Körner et al. 2022, Glim et al. 2023, Zacharski and Ferstl 2023), i.e. “does not represent men and women equally well” (Glim et al. 2023, 2). These effects are, at least in part, due to the grammatical properties of German, in which the masculine form fulfils the double-function outlined above (Garnham et al. 2012). In addition, gender stereotypes and true gender ratios in the respective societal groups modulate these effects (Gygax et al. 2016).

In 2018, the German Personal Status Act was amended to introduce a third gender option (called divers) for intersexual individuals. These developments have made the question of how to best address people beyond the binary spectrum more urgent (Kaplan 2022; for research on this topic in other languages cf., e.g., Decock et al. 2023, Thorne et al. 2023). An option already well established in the language system is to use neutralizations such as epicene nouns, or derivates of adjectives and verbs in the plural. However, besides established feminization strategies (pair forms like Lehrerinnen und Lehrer, ‘female and male teachers’), so-called gender symbols, which are inserted between the masculine base and the feminine suffix, came into use. They are intended to encompass all gender identities (e.g. Lehrer*innen, Lehrer:innen, ‘teachers of all genders’; cf. Friedrich et al. 2021, Körner et al. 2022), which a recent psycholinguistic study suggests to be actually the case (Zacharski and Ferstl 2023).Footnote 5 The symbols work particularly well in the plural because dependent elements are not marked for gender in the plural and therefore remain unchanged, and because the morphological combination of a masculine base and the feminine derivation suffix is easy to split with a symbol in the plural. Some qualitative studies have already found tendencies for fewer masculine generics and more gender-inclusive forms (Elmiger et al. 2017, cf. Adler and Plewnia 2019, Krome 2020). Quantitative studies on the use of these symbols are still scarce (e.g. Sökefeld 2021, Waldendorf 2023).

In the wake of this debate, many public bodies, large companies and other institutions are now issuing guidelines on gender-inclusive language (cf. links to guidelines of German-speaking cities; Müller-Spitzer et al., 2023, 5). However, this new awareness of gender-inclusive language has been accompanied by strong counter-movements that continue to fuel the debate and challenge the ideas behind gender-inclusive language in general (for discussions about gender-inclusive Spanish, cf. Banegas and López 2021a). Opponents often argue that the gender symbols are not part of the German language/spelling system and thus should be regarded as ‘mistakes’ (e.g. Eisenberg 2022). It is also claimed that they distract from the essential content of a text, or that they make texts harder to read, especially for children, L2 learners, or the visually impaired (e.g. Kalverkämper 1979, Rothmund and Christmann 2002, von Münch 2023). However, we argue that such effects are only likely if gender-inclusive texts are very different from those that are not gender-inclusive. This is the point of departure for our main research question. By analysing, on the basis of a large corpus, how much of a text would potentially be affected by gender-inclusive language in German, we contribute quantitative data to assess the actual relevance (measured as the proportion of affected textual material) of these claimed effects.

Method

Corpus and source selection

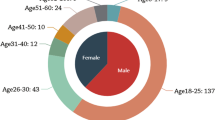

Our study is based on the German Reference Corpus (DeReKo; Kupietz et al. 2010, 2018), from which a sample of texts was selected (cf. section Sampling). These were taken from four sources: the DPA (Deutsche Presseagentur ‘German Press Agency’) and the three magazines Brigitte, Zeit Wissen, and Psychologie Heute. The DPA texts are the central resource for the study. There are several reasons for this. First, DPA is the biggest news agency in Germany, and its reports are distributed to almost all major radio stations and daily newspapers (Pürer and Raabe 2007, 29, 327). Its texts are often re-printed verbatim or only with slight variations. Second, DPA is obliged to be impartial and independent from political parties, worldviews, economic and financial groups, and governments,Footnote 6 meaning that its reports can be considered as objective as possible. Third, DPA only recently announced its decision to use more gender-neutral language from now on,Footnote 7 meaning that DPA texts from before 2021 are not already (consciously) gender-inclusive and thus serve as a good basis to investigate non-gender-inclusive language. Therefore, we only included texts from the years 2006–2020 to tackle our research questions. Fourth, our aim was to annotate whole texts, as selecting only excerpts could have undesirable biasing effects, e.g. a masculine form could be interpreted as generic, although earlier/later in the text a specific referent is introduced. DPA press releases have an average length of 339 tokens in DeReKo (cf. Table 1) and are therefore relatively short, making them well suited for whole-text annotations. To check whether similar patterns would be found in entirely different media outlets, we created a control corpus containing longer texts. The magazines Brigitte, Zeit Wissen, and Psychologie Heute were selected because they have a more general societal outlook and/or cover popular science topics. All three are issued by different publishers, minimizing the influence of publisher-specific guidelines.Footnote 8

Sampling

In the overall corpus (DeReKo), there are 2,322,095 documents available for all four sources. The sampling process was based on the number of words (tokens) per document. For each source, we calculated the 5th and 95th percentile of token counts. For DPA, the interval is [I = 87, 837], i.e. 90% of all DPA documents are between 87 and 837 words long and were selected for the sampling procedure. The values for the other sources, as well as median (50th percentile) and mean values are given in Table 1. The upper bound for the magazine sources is generally higher than for the DPA documents, i.e. there are more longer documents in the magazine sources. This is also reflected in the median and mean token counts for the four sources.

We randomly sampled a fixed number of documents that fall into the inner 90% of token counts (between the 5th and 95th percentile). For DPA, we sampled 190 documents, and for the magazine sources 40 documents each, i.e. we had a total of 310 sampled documents. After annotation, 261 texts remain in the corpus (for details, see the section Annotation process). Their token counts are summarized in Table 1 under ‘Annotated Sample’.

Annotation process

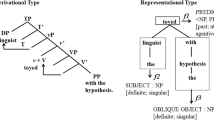

The aim of the manual annotation conducted for this study was to find all tokens that would have to be changed if the text was reformulated in a gender-inclusive way. Our annotations focus on expressions that refer to natural persons, i.e. usually heads of noun phrases (NPs) in the form of nouns or pronouns (cf. Stede 2016, 55). Accordingly, we follow an action-theoretical concept of reference based on the interpretation of the target item in the given context (Pettersson 2011, 57). In addition to the head of the noun phrase, dependent elements in the NPs are annotated. For that, we decided to apply a strict bottom-up approach, i.e. to identify the head first and then select the elements that depend on it (especially articles and attributive adjectives, cf. Table 2, as these can theoretically be affected by gender-inclusive language, as opposed to genitive constructions or prepositional phrases).

The manual that served as the basis for the annotations was developed over the course of several months. Modifications were implemented after each training round, when we could see difficulties and uncertainties regarding the application of the manual. Building upon the insights from these pre-tests, the annotation scheme underwent refinement and expansion. The more elaborate annotation scheme was then used in its final version for the present study, which was conducted from December 2022 to March 2023. Two research assistants (in the following called annotators A and B) annotated the texts simultaneously. 261 of the 310 sampled documents were annotated by both annotators,Footnote 9 yielding an overall inter-annotator agreement of 77.89%. The version of the annotation scheme used for this study consists of eleven categories with various sublayers. The decision tree in Fig. 1 illustrates the dependencies between them. Further information about the decision tree, the layers, the annotation procedure, and the inter-annotator agreement can be found in the supplementary material.Footnote 10

As ‘necessity to use a gender-inclusive form’ is the central category for our study, it is described in more detail here rather than exclusively in the supplementary material. Within the annotation procedure, it is necessary to indicate for each annotated token whether it would need to be replaced by another form in order to make the text gender-inclusive. For personal nouns, this is usually the case if the form is annotated as a masculine or feminine generic. Regarding pronouns, this is only the case for generically referring personal pronouns.Footnote 11 Dependent elements need to be adjusted only if the head of the NP would be subject to change – however, dependent elements need to be thoroughly checked to determine whether they would actually change form in case of an adjustment to gender-inclusive language (e.g. most attributive adjectives are identical for feminine and masculine gender: der kranke Patient/die kranke Patientin; ‘the sick [male/female] patient’). Example (a) illustrates this further:

-

a.

Während die einst potenten Sozialdemokraten im Bund unter ihrem Parteichef Kurt Beck in der Krise stecken, träumen die traditionell schwachen bayerischen Genossen von der Machtübernahme im Freistaat. (‘While the once-powerful Social Democrats at the Federal level are in crisis under their leader Kurt Beck, their traditionally weak Bavarian comrades dream of taking power in the Free State [Bavaria].’ (DPA08_JUL03207)

In this sentence, only two nouns are annotated as having a ‘necessity to use gender-inclusive form’ (printed in bold). The dependent elements in the noun phrase would not need to be changed, as can be seen in Table 2: Even if the heads were changed to gender-inclusive forms, the dependent elements would remain the same. The excerpt also contains a specific male person (Kurt Beck) and a masculine role noun, Parteichef (‘party leader’), referring to him. Accordingly, Parteichef is annotated as a personal noun with specific male reference.

In what follows, we will report analyses based on the 261 documents that were annotated by both annotators.Footnote 12 Figure 2 gives an overview of the token count distributions of candidate texts (i.e. all texts after selecting the inner 90% of token counts for each source) and the 261 texts on which we base our analyses. Comparing these distributions, we can conclude that the texts reported here provide a good reflection of the underlying token count distributions for DPA, Brigitte, Psychologie Heute, and Zeit Wissen.Footnote 13

Distribution of token counts (y-axis) for the candidate texts (grey violins), i.e. all texts with a token count in the inner 90% of all texts from this source (x-axis). Data points represent token counts for all 261 texts reported in the remainder of the paper (one point per document). [This figure is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reproduced with permission of IDS Mannheim; copyright © IDS Mannheim, all rights reserved.].

Results & Discussion

Person reference and linguistic classes

In total, the 261 texts annotated by both annotators comprise 120,626 tokens.Footnote 14 Without punctuation marks, 93,533 tokens remain.Footnote 15 Of these, 11,375 tokens (12.2%) were annotated by at least one annotator as having person reference (i.e., as belonging to the linguistic classes 1–3: personal noun, pronoun, dependent element). The annotators agreed on the linguistic class of 8,840 (A = B; 77.71%) of these tokens; another 675 (5.93%) were annotated by both, but with diverging linguistic classes (A ≠ B); 1,860 tokens (16.35%) were annotated by only one annotator (A v B). This means that the vagueness regarding which token can be considered person reference is roughly 16%. Importantly, this vagueness (or uncertainty) is distributed unevenly across linguistic classes. Dependent elements (LK_3) caused the most insecurities, constituting 58.06% of all tokens that were annotated only once. From what we discussed earlier regarding phrase structure, it is probable that this is due to uncertainties about which elements belong to an NP and therefore have person reference. Hence, an important takeaway for future studies is the necessity to improve the training of research assistants in the domain of phrase-structure grammar. With 27.37%, personal nouns (LK_1) ranked second regarding non-matching annotations. Pronouns were the least problematic, making up 13.82% of vagueness. The remaining proportion of insecurity is attributed to nouns that superficially look like personal nouns but actually refer to objects or institutions or are used metaphorically (e.g. Partner, ‘partner’, to refer to a country). For this study, we only consider the 8,840 tokens with matching annotations to represent reliably the amount of person reference in the annotated texts. Personal nouns are the biggest category with 3,196 tokens (3.42% of all tokens; Sökefeld et al. 2023 find a similar proportion of personal nouns in their automatic detection tests), followed by dependent elements (3,097 tokens; 3.31%) and pronouns (2,547 tokens; 2.72%).

All measures reported so far refer to all documents in the corpus as one large list of tokens. However, in order to accurately assess the relevant proportions of tokens, we have to consider the document level (which was also our level of sampling). We therefore determined the proportions for each document and then calculated overall means, weighted by the number of tokens each document contributes to this mean. For each value of the weighted mean, we report 95% confidence intervals according to a hypergeometric distribution in brackets. This is the appropriate method in this case because the annotated texts were sampled from the candidate texts without replacement.Footnote 16 Figure 3 shows the proportions of tokens with person reference for the DPA and the control (i.e. Brigitte, Psychologie Heute, Zeit Wissen) corpora. While the mean for all DPA documents is 7.99% (7.75%–8.23%), it is significantly higher for the control corpus at 11.06% (10.77%–11.35%). The mean of all sources taken together is 9.45% (9.26%–9.64%).

Data points represent documents; the red square indicates the mean, including error bars that symbolize the 95% confidence intervals (sometimes these are fully covered by the square – e.g. in the left boxplot). [This figure is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reproduced with permission of IDS Mannheim; copyright © IDS Mannheim, all rights reserved.].

Necessity to use gender-inclusive language

The annotation category ‘necessity to use gender-inclusive form’ holds a pivotal role in addressing the primary research question of this study: to what extent would tokens within press texts have to undergo changes due to the adoption of gender-inclusive language? For DPA, the average share of tokens that would be affected by gender-inclusive re-editings is 0.73% (0.66%–0.81%), whereas it is 1.18% (1.09%–1.29%), and therefore significantly higher, for the control corpus (cf. Fig. 4). If we take all sources together, we get a proportion of 0.95% (0.89%–1.01%) that would be affected by gender-inclusive language. Considering only tokens with person reference, an average of 9.13% (8.25%–10.08%) would be affected by gender-inclusive language in DPA and 10.67% (9.82%–11.56%) in the control corpus. Here, the difference between the corpora is not significant. Taking all sources together, an average of 9.99% (9.37%–10.63%) of person references would be subject to gender-inclusive language. We can therefore record three central measures so far: all sources taken together, on average a) 9.45% of tokens are (part of) person references; b) 0.95% of all tokens would be affected by gender-inclusive language; and c) 9.99% of all tokens with person reference would be affected by gender-inclusive language.Footnote 17

Figure 5 shows that the largest proportion of affected tokens (tokens that would have to be changed) belongs to the category ‘personal nouns’ (799 tokens overall; 90.08% of the total of 887), i.e. gender-inclusive language would mostly affect nouns. All affected personal nouns are masculine generics, underlining that they are the focus of gender-inclusive language. The average proportion of personal nouns that would be changed by gender-inclusive language across all the documents is 25.00% (23.51%–26.54%). There are six documents in which all personal nouns would be subject to change (i.e. the dots at the 100% margin), but far more documents in which none of the personal nouns would need to be changed (N = 81, dots at the 0% margin). More details on the amount of documents that would be affected by changes can be found in the following section. For the other two linguistic classes, the proportion is only marginal – in most documents, none of the pronouns or dependent elements would be subject to change. This is especially clear for pronouns, where the average proportion is 0.12% (0.02%–0.34%). For dependent elements, it is 2.62% (2.08%–3.24%), with one outlier document in which about 66.00% of dependent elements would be changed if gender-inclusive language were used in the document. Gender-inclusive re-editings would therefore rarely interfere with the grammar of the extended noun phrase.

Personal nouns

The category of personal nouns will be discussed in detail for four reasons: Personal nouns are (a) the most frequent linguistic class, (b) the class with the highest proportion of tokens that would be affected by gender-inclusive language, (c) the linguistic class with the most diverse annotation layers (cf. Supplementary Material, Section 1), and (d) the linguistic class most relevant to the study of the linguistic representation of people in texts (e.g. Hellinger and Bußmann 2003, 143).

First, we report the distribution of annotation layers for personal nouns. Taking all sources together, we see a prominence of epicene nouns (27.32%, 25.78–28.90%), closely followed by masculine generics (24.97%, 23.48–26.51%), and masculine specifics (22.93%, 21.49–24.43%). Lexical gender nouns (9.95%, 8.93–11.04%) and feminized forms (8.04%, 7.12–9.04%) are significantly rarer. We find no nouns that were annotated as feminine generics by both annotators. Figure 6 shows that the distribution of layers for personal nouns varies considerably between the two corpora. In DPA, masculine specifics are by far dominant (mean share of 36.47%, 34.10–38.89%), especially compared to the control corpus, where this category only amounts to an average share of 9.48% (8.09–11.02%). For all other categories, it is the other way around. The average shares of epicenes, masculine generics, lexical gender nouns, and feminized forms are always higher in the control corpus. We can deduce that DPA predominantly reports on specific male persons, using masculine forms, whereas the other sources tend to report more unspecifically, i.e. making use of gender-neutral forms (e.g. epicenes) and masculine generics. Referent gender is mostly specified by lexical gender nouns in the control corpus (e.g. Frau ‘woman’, Mann ‘man’), while such forms are infrequent in DPA.

Looking at the annotation layer ‘Which referent gender is recognizable from context?’, we see clear differences between DPA and the control corpus (cf. Fig. 7). In DPA, there is a strong male bias. If referent gender is recognizable from context in DPA,Footnote 18 a mean share of 80.37% (77.46–83.05%) of these tokens refer to men. Only an average of 19.01% (16.37%–21.89%) refer to women. This strong male dominance in news reporting is in line with findings of other studies (e.g., Saily et al. 2011, Lansdall-Welfare et al. 2017). In the control corpus, however, the bias disappears: the average share of tokens referring to women (52.87%, 48.56–57.14%) is even slightly higher than for men (45.29%, 41.04–49.59%). Brigitte has the biggest influence here—a mean of 60.54% (54.32–66.51%) of tokens for which referent gender is identifiable refer to women, while only 38.70% (32.76–44.90%) refer to men. In our corpus, no non-binary referents were identified. ‘Group’ reference (i.e. to mixed groups of men and women) is rare (N = 11 in all documents taken together) and not discussed further here. These findings indicate substantial differences in the way different sources include men and women in their reporting, which is most likely due to differences in topics and audiences (cf. e.g., Müller-Spitzer and Rüdiger 2022). However, comparable corpus studies are needed to draw such conclusions on a reliable basis.

Share of tokens for which ‘male/female gender’ or ‘group’ is deducible from context (total amount: tokens for which referent gender is recognizable from context). Only outlier documents are shown as data points. [This figure is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reproduced with permission of IDS Mannheim; copyright © IDS Mannheim, all rights reserved.].

Our method can thus also be used to quantify the occurrences of men and women mentioned in press texts. It encompasses all personal nouns and therefore goes beyond the analysis of proper names, which are used by Eugenidis & Lenz (2022), for example, to quantify the proportion of men and women on company websites. This is especially relevant as media outlets increasingly seek to scrutinize gender proportions within their articles. One example is the renowned German weekly magazine Der Spiegel, which conducted an analysis of gender proportions in their own texts (Pauly 2021). However, they pointed out that they could not include personal nouns in their evaluations because they used procedures for named entity recognition (Pauly 2021). Our approach could effectively supplement such automated procedures in grammatical gender languages. Additionally, our annotated dataset could serve as training material for developing automatic processes to detect personal nouns, particularly in terms of distinguishing between generic and specific references. The need to supplement automated processes with in-depth annotations is also highlighted by Sökefeld et al. (2023, 38).

Furthermore, our annotations allow us to analyse the distribution of masculine specifics and masculine generics in more detail and to investigate the embedding of masculine generics in actual language use. Here, we provide a brief insight, focusing on the document level of our data. In total, 116 of the 261 annotated texts (44.44%) contain both masculine generics and specifics. In 55 of these (47.41%), specifics are more common than generics; in 48 documents (41.38%), it is the other way around. Another 22 texts (18.97%) have equal amounts of masculine specifics and generics. In 104 texts (39.85%), we find only one of the forms: 57 (54.81%) have only masculine specifics; 47 contain only masculine generics (45.19%). This means that there are 41 texts (15.71%) in which neither a specific nor a generic masculine is used. In sum, texts with both specifics and generics are most common, followed by texts with only masculine specifics and texts with only masculine generics. Texts without any of these forms are least common. Gender-inclusive re-editings would in sum affect 163 of the 261 annotated documents (62.45%). To put it differently, in more than a third of the documents, nothing would need to be changed if gender-inclusive language was applied.

The prototypical use of the masculine generic is often considered to be found in abstract contexts (cf. Zifonun 2018, 49–50) in which no specific individuals are referred to and in which the semantic category ‘gender’ is presumably neutralised (ex. b). However, our data show that masculine generics can be used in a diverse set of contextual embeddings and with different levels of referentiality. We find, for example, four cases in which a masculine plural refers to a pair consisting of a man and a woman. They are introduced with their names in the text and then collectively referred to with a masculine generic (ex. c). We also find one masculine form with female reference (ex. d) in an enumeration with feminized forms and a lexical gender noun, all referring to the same woman. In many other cases, the masculine generic is used in contexts where a small and specific number of referents (ex. e) are introduced but whose genders are not specified in the rest of the text.

-

b.

Die Preisträger genießen an Schulen besonderes Ansehen. (‘(The) Award winners enjoy a special reputation at the school.’) (from Zifonun 2018, 50)

-

c.

[…] haben die Psychologen Angela Duckworth und Martin Seligman […] (‘[…] the psychologists Angela Duckworth and Martin Seligman have […]’) (PH07_AUG.00032)

-

d.

Stylistin und Spielplatzmami, Kinderkutschierer und Großeinkäuferin. (‘Stylist and playground-mummy, children’s coachman and bulk buyer.’) (BRG10_JAN.00047)

-

e.

Sieben Umweltaktivisten aus verschiedenen Teilen der Welt […] (‘Seven environmental activists from different parts of the world […]’) (DPA08_APR.08223)

While having the power to level out the importance of gender in such contexts (Zifonun 2018, 50–51), the masculine generic can also be understood to veil referent genders and make women (and other genders) invisible or at least harder to include cognitively (as is suggested by various psycholinguistic studies on the male bias, e.g. Gygax et al. 2008, Körner et al. 2022, Zacharski and Ferstl 2023). The referential ambiguity of the masculine can challenge readers, raising the question of whether this challenge is greater than decoding gender-inclusive forms, which are unambiguous as they never refer solely to men. The annotated dataset is published with this paper (see Supplementary Material, Section 5), allowing further analyses of these different forms of embedding by any interested researcher.

Conclusion

Research into the connection of gender and language is tightly knitted to social debates on gender equality and non-discriminatory language use. By now, there is a growing body of studies investigating linguistic dimensions of the category ‘gender’. Psycholinguistic scholars have made significant contributions, particularly in addressing the male bias associated with masculine generics. However, there exists a demand for more corpus-based studies that investigate real language usage as the debate on gender-inclusive language is mostly guided by unverified presuppositions. One major claim is that the use of gender-inclusive language makes texts too long, monotonous or difficult to read, and might even make it more difficult to learn German as a foreign language. These would be strong arguments against the use of gender-inclusive language, but they are not based on empirical evidence (cf. Pabst and Kollmayer 2023, Blake and Klimmt 2010, Friedrich and Heise 2019, and on German as a foreign language Peuschel 2022). Our data provides the first empirical quantitative basis of how much textual material would actually have to be changed if non-gender-inclusive German texts were rewritten to be gender-inclusive. We extracted three central values from our analysis: an average of (a) 9.45% of all tokens are (or are part of) person references; (b) 0.95% of all tokens would be affected by gender-inclusive language; (c) 9.99% of tokens with person reference would be affected by gender-inclusive language. In total, one third of all documents we analysed would remain unchanged. The small proportion in (b) calls into question whether gender-inclusive German presents a substantial barrier to understanding and learning the language, particularly when we take into account the potential complexities of interpreting masculine generics. Furthermore, not all tokens would have to be replaced by more than one other token if we wanted to reformulate the texts in a gender-inclusive way. Many lexemes in German can be neutralised (e.g. by replacing the masculine generic Lehrer (‘teacher’) with the neutralising Lehrkraft (‘teaching staff’). With this strategy, the length or complexity of the texts does not increase. In general, gender-inclusive language would almost exclusively concern nouns, for which there are already numerous strategies of implementing unobtrusive gender-inclusive variants that do not include the disputed gender symbols (e.g. pair forms and epicenes, cf. Steinhauer and Diewald 2017, 118, 132). A recent survey by the German public-broadcasting institution WDRFootnote 19 has shown that many of these variants are already widely accepted.

The low proportion of textual material affected by gender-inclusive language can also be approached from another perspective, namely by counting the amount of explicit gender-inclusive forms in press texts that generally use such language. In Germany, the newspaper tazFootnote 20 is a prime example. Although it has no internal guidelines on gender-inclusive language, it is considered a ‘pioneer’ (Ochs and Rüdiger under review) in its use and is the only daily newspaper to use new strategies such as gender symbols (Lehrer*innen, Lehrer:innen) in a significant way (cf. Waldendorf 2023). However, the proportion of these forms in the whole text is only 0.2% (Ochs and Rüdiger under review). For the first time, our data provide a quantitatively reliable explanation for this: the fact that this proportion is so low is most likely due to the fact that only a small amount of linguistic material is affected by changes to gender-inclusive forms. Our results therefore point in the direction suggested by sociolinguistic studies: The discussions about gender-inclusive language may (ostensibly) revolve around issues of comprehensibility, readability and learnability, but there is more at stake – gender debates, including discussions about gender-inclusive language, are part of a broader cultural struggle (Blömen and Wilde 2019, Banegas and López 2021b, Roth and Sauer 2022). This is not to say, however, the possible complexities of gender-inclusive language should not continue to be investigated empirically – on the contrary: As describing and comparing the complexity of linguistic items is a difficult endeavour, our data are mainly intended to provide future research with a quantitative baseline – e.g. to compare the values with proportions of other structures that are considered complex in German. Further research into the comprehensibility, readability and learnability of different gender-inclusive forms can take our insights into consideration.

Outlook

Finally, we would like to specify two possible follow-up studies. We see especially promising potential in combining our data with automatic extraction procedures for personal nouns (Sökefeld et al. 2023), e.g. by using our annotations as training data for the recognition of masculine specifics and generics. To further this approach, we are currently in the process of conducting analyses at the lexical level to determine whether certain types of personal nouns (e.g. passive role nouns such as neighbour or citizen, cf. Bühlmann 2002, 174) are more prone to being used as masculine generics. Additionally, as we are aware that text type and genre are crucial categories when it comes to the use of gender-inclusive language and personal nouns in general, we conduct synchronic and diachronic analyses of other text types, e.g. city and company websites, letters to shareholders, protocols of parliamentary debates, Christmas and New Year addresses of the German chancellors and presidents (cf. Müller-Spitzer et al. 2022, Müller-Spitzer and Ochs 2023, 2024). This will help us better understand the use of person references across text types, i.e. beyond the press texts presented here. Furthermore, as corpus-based research into person reference is so far mostly limited to German and English, the extension of our approach to more languages would certainly be a fruitful addition to gender and language research.

Additionally, our annotated dataset could serve as a starting point to assess the difference (e.g., in terms of language processing or comprehensibility) between non-gender-inclusive and gender-inclusive texts. One possible approach to investigate this question is to use large language models (LLMs).Footnote 21 In this context, we could employ our annotated texts and prepare comparison versions rewritten to be gender-inclusive. We could then use a pretrained LLM to compute how difficult it is for the LLM to predict or process each text and its corresponding rewritten version. Comparing the difficulty of original and rewritten texts would then provide a quantitative measure of comprehensibility. This approach could be enriched by using several different forms of gender-inclusive language (comparable to Rosola et al. 2023), assessing the varying comprehensibility of these alternative forms with LLMs.

Data availability

The data are available via our datapublisher. The R scripts and the Supplementary Material are available via the OSF. (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/AZYUE)

Notes

Own translation, original: “Genderdeutsch macht einen Text schwerfällig”.

Own translation, original: “Mit diesen Verdoppelungen und Sonderzeichen wird die Sprache zudem für Ausländer, die erwägen, Deutsch zu lernen, noch komplizierter und abschreckender.”

Own translation, original: “Verständliche, lesbare und zugängliche Sprache wird durch Gendern nicht gewährleistet. Sternchen und Passivkonstruktionen machen Texte leseunfreundlich und länger.”

Own translation, original: “Als Nachteil [des Genderns, inbes. Doppelformen] gilt der sprachliche Aufwand, dessen Wiederholung Texte lang, eintönig und sexusfixiert macht.”

https://www.dpa.com/en/about-dpa [last accessed: 1 August 2024]

https://www.presseportal.de/pm/8218/4947122 [last accessed: 1 August 2024]

Brigitte, published by Gruner+Jahr, is a women’s magazine covering a wide range of social issues (approx. 241,000 copies sold, biweekly: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brigitte_(magazine) [last accessed: 1 August 2024]). Psychologie Heute is a popular science magazine on psychology, published monthly by the Beltz publishing group (approx. 63,000 copies sold: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychologie_Heute [last accessed: 1 August 2024]), and Zeit Wissen is a popular science magazine published by Zeitverlag (approx. 97,000 copies sold, bimonthly: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zeit_Wissen [last accessed: 1 August 2024]).

Of the 310 sampled texts, 261 were annotated by both annotators. 34 were annotated only by annotator A because annotator B left our institution before being able to complete the annotations (1 DPA, 33 Zeit Wissen). Unfortunately, 15 texts were not annotated at all (5 DPA, 5 Brigitte, 1 Zeit Wissen, 4 Psychologie Heute) because of user errors within the annotation tool. We considered re-annotating the missing texts but dismissed the idea because we did not want to introduce potential biases from a third annotator. We believe that, given the number of texts that were initially sampled, these minor losses of material would not distort the outcome. In total, this reduces the sample size to 184 DPA, 35 Brigitte, 36 Psychologie Heute, 6 Zeit Wissen texts.

https://osf.io/azyue/ [last accessed: 1 August 2024].

It is a topic of linguistic debate whether or not generic pronouns are gender-inclusive in their traditional form (e.g. Feilke 2022). We annotated the masculine relative pronoun der as having the ‘necessity to use a gender-inclusive form’ in contexts like Wer schwanger ist, der soll… ‘whoever [m.] is pregnant (that [m.]) should…’. Wer is a generic masculine pronoun with no feminine counterpart (therefore not annotated as changeable), and the relative pronoun der refers back to it and therefore has the congruent masculine form (with a feminine equivalent die existing, therefore annotated as being changeable).

Information on data and code availability can be found in Section 5 of the Supplementary Material.

Note that only six texts from Zeit Wissen remain in the final analysis. It is particularly noticeable that no longer text from the upper end of the distribution for Zeit Wissen is included. However, we will conduct no general analysis of single sources from the control corpus. Rather, the remaining six Zeit Wissen texts enter the larger collection of texts together with Brigitte and Psychologie Heute to serve as a control corpus with which results from DPA can be compared.

The 34 texts that were only annotated once (by annotator A) comprise 30,764 tokens (with punctuation marks). These are excluded from the present study as we want to focus on those tokens that have matching annotations from both annotators.

We decided to exclude punctuation marks from the total token count because including them would have led to an under-estimation of the share of tokens that would be affected by the use of gender-inclusive language.

In Section 4 of the supplementary material, we also provide unweighted mean proportions with bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals.

We suppose that the perceived ‘omnipresence’ of gender-inclusive language might stem from a conflation of these numbers in lay perspectives. As an opener to a conference talk, we asked: What percentage of tokens in press texts would have to be changed (from non-gender-inclusive to gender-inclusive)? Most of the audience thought ‘10%’ was the right answer (the options were: 1%, 3%, 7%, 10%). It could be the case here that people correctly guessed the amount of person reference in texts, and then assumed that all of these tokens would need to be changed; or they correctly assumed the share of person references that would be affected instead of the share of all tokens. Our analyses show that gender-inclusive language would leave the biggest share of tokens and person references unchanged.

Referent gender was to be identified within the confines of the text, e.g. based on names or specific, identifiable positions like Kanzlerin Merkel ‘chancellor[f.sg.] Merkel’. The annotators were asked not to engage in any (text-external) research concerning the referenced persons. Of course, if the annotators had the relevant world knowledge about referent gender even if it was not specified in the text itself, they could make use of that knowledge, e.g. alle früheren US-Präsidenten ‘all former US presidents[m.pl.]’ can be annotated as a masculine specific if the annotator knows that all former US presidents were men. There were no non-binary referents identified by our annotators – within a text, this would be possible if it is directly mentioned or explained that the person is non-binary, or if neopronouns were used to refer to this person (like sier, xier or dey in German). Otherwise, world knowledge could have helped as well, e.g. if Sam Smith (a non-binary musician) had been mentioned and the annotators had known about their gender identity.

https://www1.wdr.de/nachrichten/gender-umfrage-infratest-dimap-100.html [last accessed: 1 August 2024]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Die_Tageszeitung [last accessed: 1 August 2024].

LLMs excel in traditional linguistic tasks, as evidenced by their ability to perform zero-shot learning, where they effectively generalize to new tasks without specific training, as demonstrated by Brown et al. (2020). This underscores their potential to acquire human-like grammatical language through statistical learning, without relying on a built-in grammar, according to Chater & Vitányi (2007). On this basis, a vibrant research field has emerged, wherein LLMs are being utilized as computational models (Contreras Kallens et al. 2023) and models of language (Grindrod 2024) to study various aspects of language processing and comprehension (Piantadosi 2023).

References

Acke H (2019) Sprachwandel durch feministische Sprachkritik. Z. f.ür. Literaturwissenschaft und Linguistik 49:303–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41244-019-00135-1

Adler A, Plewnia A (2019) Die Macht der großen Zahlen. Aktuelle Spracheinstellungen in Deutschland. In: Eichinger LM, Plewnia A (Eds), Neues vom heutigen Deutsch. Empirisch - methodisch - theoretisch. De Gruyter, Berlin; New York, 141–162

Baker P (2010) Will Ms ever be as frequent as Mr? A corpus-based comparison of gendered terms across four diachronic corpora of British English. Gend. Lang. 4:125–149. https://doi.org/10.1558/genl.v4i1.125

Banegas DL, López MF (2021a) Inclusive Language in Spanish as Interpellation to Educational Authorities. Appl. Linguist. 42:342–346. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amz026

Banegas DL, López MF (2021b) Inclusive Language in Spanish as Interpellation to Educational Authorities. Appl. Linguist. 42:342–346. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amz026

Becker T (2008) Zum generischen Maskulinum: Bedeutung und Gebrauch der nicht-movierten Personenbezeichnungen im Deutschen. Linguistische Ber. 213:65–76

Blake C, Klimmt C (2010) Geschlechtergerechte Formulierungen in Nachrichtentexten. Publizistik 55:289–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11616-010-0093-2

Blömen H, Wilde G (2019) Genderdiskurse im bundesdeutschen Europawahlkampf 2019: Zwischen feministisch-demokratischem Aufbruch und rechtsautoritärer Aushöhlung. Femina Politica – Zeitschrift für feministische Politikwissenschaft 28. Available from: https://www.budrich-journals.de/index.php/feminapolitica/article/view/34461

Braun F, Oelkers S, Rogalski K, Bosak J, Sczesny S (2007) Aus Gründen der Verständlichkeit …“: Der Einfluss generisch maskuliner und alternativer Personenbezeichnungen auf die kognitive Verarbeitung von Texten. Psychologische Rundsch. 58:183–189. https://doi.org/10.1026/0033-3042.58.3.183

Brown T, Mann B, Ryder N, Subbiah M, Kaplan JD, Dhariwal P, Neelakantan A, Shyam P, Sastry G, Askell A, Agarwal S, Herbert-Voss A, Krueger G, Henighan T, Child R, Ramesh A, Ziegler D, Wu J, Winter C, Hesse C, Chen M, Sigler E, Litwin M, Gray S, Chess B, Clark J, Berner C, McCandlish S, Radford A, Sutskever I, Amodei D (2020) Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. In: Larochelle H, Ranzato M, Hadsell R, Balcan MF, Lin H (Eds), Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. Curran Associates, Inc., 1877–1901. Available from: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2020/file/1457c0d6bfcb4967418bfb8ac142f64a-Paper.pdf

Bühlmann R (2002) Ehefrau Vreni haucht ihm ins Ohr… Untersuchung zur geschlechtergerechten Sprache und zur Darstellung von Frauen in Deutschschweizer Tageszeitungen. Linguistik Online 11. https://doi.org/10.13092/lo.11.918

Chater N, Vitányi P (2007) Ideal learning’ of natural language: Positive results about learning from positive evidence. J. Math. Psychol. 51:135–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmp.2006.10.002

Contreras Kallens P, Kristensen‐McLachlan RD, Christiansen MH (2023) Large Language Models Demonstrate the Potential of Statistical Learning in Language. Cogn. Sci. 47:e13256. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.13256

Corbett GG (1991) Gender. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139166119

Corbett GG (2013) Introduction. In: Corbett GG (Ed.), The Expression of Gender. De Gruyter Mouton, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110307337.1

Decock S, Van Hoof S, Soens E, Verhaegen H (2023) The comprehensibility and appreciation of non-binary pronouns in newspaper reporting. The case of hen and die in Dutch. Applied Linguistics: amad028. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amad028

Diewald G (2018) Zur Diskussion: Geschlechtergerechte Sprache als Thema der germanistischen Linguistik – exemplarisch exerziert am Streit um das sogenannte generische Maskulinum. Z. f.ür. germanistische Linguistik 46:283–299. https://doi.org/10.1515/zgl-2018-0016

Doleschal U (1992) Movierung im Deutschen: eine Darstellung der Bildung und Verwendung weiblicher Personenbezeichnungen. Lincom Europa, Unterschleissheim/München

Dülffer M (2018) Warum wir nicht Gendern. Zeit Online: Glashaus. Available from: https://blog.zeit.de/glashaus/2018/02/07/gendern-schreibweise-geschlecht-maenner-frauen-ansprache/

Eisenberg P (2020) Zur Vermeidung sprachlicher Diskriminierung im Deutschen. Themenh. “Sprache und Geschlecht”: Beitr.äge zur. Gend.-Debatte 130:3–16

Eisenberg P (2022) Weder geschlechtergerecht noch gendersensibel. APuZ Aus Polit. und Zeitgesch. 5–7:30–35

Elmiger D, Schaefer-Lacroix E, Tunger V (2017) Geschlechtergerechte Sprache in Schweizer Behördentexten: Möglichkeiten und Grenzen einer mehrsprachigen Umsetzung. Sprache und Geschlecht. Band. 1: Sprachpolitiken und Gramm. 90:61–90

Eugenidis D, Lenz D (2022) Measuring Gender Differences in Personalities through Natural Language in the Labor Force: Application of the 5-Factor Model. MAGKS Papers on Economics. Available from: https://ideas.repec.org//p/mar/magkse/202240.html

Friedrich MCG, Heise E (2019) Does the Use of Gender-Fair Language Influence the Comprehensibility of Texts? Swiss J. Psychol. 78:51–60. https://doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185/a000223

Friedrich MCG, Drößler V, Oberlehberg N, Heise E (2021) The Influence of the Gender Asterisk (“Gendersternchen”) on Comprehensibility and Interest. Front. Psychol. 12:1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.760062

Garnham A, Gabriel U, Sarrasin O, Gygax P, Oakhill J (2012) Gender Representation in Different Languages and Grammatical Marking on Pronouns: When Beauticians, Musicians, and Mechanics Remain Men. Discourse Process. 49:481–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2012.688184

Glim S, Körner A, Härtl H, Rummer R (2023) Early ERP indices of gender-biased processing elicited by generic masculine role nouns and the feminine–masculine pair form. Brain Lang. 242:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandl.2023.105290

Grindrod J (2024) Modelling Language. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2404.09579

Gygax P, Gesto N (2007) Féminisation et lourdeur de texte. L’Année psychologique 107:239–255

Gygax P, Garnham A, Doehren S (2016) What Do True Gender Ratios and Stereotype Norms Really Tell Us? Front. Psychol. 7:1–6

Gygax P, Gabriel U, Sarrasin O, Oakhill J, Garnham A (2008) Generically intended, but specifically interpreted: When beauticians, musicians, and mechanics are all men. Lang. Cogn. Process. 23:464–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/01690960701702035

Hellinger M, Bußmann H (2003) Engendering female visibility in German. In: Hellinger M, Bußmann H (Eds), Gender Across Languages: The linguistic representation of women and men. Volume 3. John Benjamins Publishing Co, Amsterdam ; Philadelphia, 141–174

Kalverkämper H (1979) Die Frauen und die Sprache. Linguistische Ber. 62:55–71

Kaplan JM (2022) Pluri-Grammars for Pluri-Genders: Competing Gender Systems in the Nominal Morphology of Non-Binary French. Languages 7:1–34. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7040266

Klein A (2022) Wohin mit Epikoina? – Überlegungen zur Grammatik und Pragmatik geschlechtsindefiniter Personenbezeichnungen. In: Diewald G, Nübling D (Eds), Genus – Sexus – Gender. De Gruyter, Berlin, Boston, 135–190. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110746396-005

Körner A, Abraham B, Rummer R, Strack F (2022) Gender Representations Elicited by the Gender Star Form. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 41:553–571. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X221080181

Krome S (2020) Zwischen gesellschaftlichem Diskurs und Rechtschreibnormierung: Geschlechtergerechte Sprache als Herausforderung für gelungene Textrealisation. Themenheft “Sprache und Geschlecht”. Beitr.äge zur. Gend.-Debatte 130:64–78

Kupietz M, Belica C, Keibel H, Witt A (2010) The German Reference Corpus DeReKo: A Primordial Sample for Linguistic Research. In: Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’10). European Language Resources Association (ELRA), Valletta, Malta, 1848–1854

Kupietz M, Lüngen H, Kamocki P, Witt A (2018) The German Reference Corpus DeReKo: New Developments – New Opportunities. In: Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2018)., 4353–4360

Kusterle K (2011) Die Macht von Sprachformen: Der Zusammenhang von Sprache, Denken und Genderwahrnehmung. 1. Auflage. Brandes & Apsel, Frankfurt am Main

Lansdall-Welfare T, Sudhahar S, Thompson J, Lewis J, Team FN, Cristianini N, Gregor A, Low B, Atkin-Wright T, Dobson M, Callison R (2017) Content analysis of 150 years of British periodicals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 114:457–465. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1606380114

McConnell-Ginet S (2013) Gender and its relation to sex: The myth of ‘natural’ gender. In: The Expression of Gender. De Gruyter Mouton, 3–38. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110307337.3

Meineke E (2023) Studien zum genderneutralen Maskulinum. 1st edition. Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg

Motschenbacher H (2015) Some new perspectives on gendered language structures. In: Hellinger M, Motschenbacher H (Eds), Gender Across Languages: Volume 4. IMPACT: Studies in Language, Culture and Society. John Benjamins Publishing Company, 27–48. https://doi.org/10.1075/impact.36.02mot

Müller-Spitzer C (2022a) Der Kampf ums Gendern. Kontextualisierung der Debatte um eine geschlechtergerechte Sprache. Kursbuch 209:28–45

Müller-Spitzer C (2022b) Zum Stand der Forschung zu geschlechtergerechter Sprache. APuZ Aus Polit. und Zeitgesch. 5–7:23–29

Müller-Spitzer C, Rüdiger JO (2022) The influence of the corpus on the representation of gender stereotypes in the dictionary. A case study of corpus-based dictionaries of German. Available from: https://euralex.org/publications/the-influence-of-the-corpus-on-the-representation-of-gender-stereotypes-in-the-dictionary-a-case-study-of-corpus-based-dictionaries-of-german/

Müller-Spitzer C, Ochs S (2023) Geschlechtergerechte Sprache auf den Webseiten deutscher, österreichischer, schweizerischer und Südtiroler Städte. Sprachreport 39:1–5. https://doi.org/10.14618/sr-2-2023_mue

Müller-Spitzer C, Ochs S (2024) Shifting social norms as a driving force for linguistic change: Struggles about language and gender in the German Bundestag. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2402.03887

Müller-Spitzer C, Rüdiger JO, Wolfer S (2022) Olaf Scholz gendert. Eine Analyse von Personenbezeichnungen in Weihnachts- und Neujahrsansprachen. Linguistische Werkstattberichte. Available from: https://lingdrafts.hypotheses.org/2370

von Münch I (2023) Gendersprache: Kampf oder Krampf? Duncker & Humblot, Berlin

Ochs S, Rüdiger JO (under review) Of stars and colons: A corpus-based analysis of gender-inclusive orthographies in German press texts. In: Schmitz D, Stein SD, Schneider V (Eds), Linguistic intersections of language and gender: Of gender bias and gender fairness

Pabst LM, Kollmayer M (2023) How to make a difference: The impact of gender-fair language on text comprehensibility amongst adults with and without an academic background. Front. Psychol. Sec. Gend., Sex. Sexualities 14:1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1234860

Pauly M (2021) Geschlechterverhältnis in SPIEGEL-Artikeln: So haben wir Frauen und Männer gezählt. Der Spiegel. Available from: https://www.spiegel.de/backstage/geschlechterverhaeltnis-in-spiegel-artikeln-so-haben-wir-frauen-und-maenner-gezaehlt-a-7eca4fd3-aaeb-4cc8-8ffb-ef72a38a003c

Pettersson M (2011) Geschlechtsübergreifende Personenbezeichnungen: Eine Referenz- und Relevanzanalyse an Texten. Narr Francke Attempto Tübingen

Peuschel K (2022) Gendergerechte Sprache aus der Perspektive des Lehrens und Lernens. APuZ Aus Polit. und Zeitgesch. 5–7:49–54

Piantadosi ST (2023) Modern language models refute Chomsky’s approach to language. lingbuzz/007180

Pürer H, Raabe J (2007) Presse in Deutschland. UVK Konstanz

Pusch LF (1984) “Sie sah zu ihm auf wie zu einem Gott”. Das Duden-Bedeutungswörterbuch als Trivialroman. In: Das Deutsche als Männersprache: Aufsätze und Glossen zur feministischen Linguistik. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt, 135–144

Rock Z do (2021) Geschlechtergerechte Sprache: Von innen, unnen und onnen. Die Zeit. Available from: https://www.zeit.de/2021/32/geschlechtergerechte-sprache-diskriminierung-gendersternchen

Rosola M, Frenda S, Cignarella AT, Pellegrini M, Marra A, Floris M (2023) Beyond Obscuration and Visibility: Thoughts on the Different Strategies of Gender-Fair Language in Italian. In: CLiC-it 2023: 9th Italian Conference on Computational Linguistics. Venice, Italy. Available from: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3596/paper42.pdf

Roth J, Sauer B (2022) Worldwide Anti-Gender Mobilization: Right-wing Contestations of Women’s and Gender Rights. In: Global Contestations of Gender Rights. Bielefeld University Press, 99–114. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839460696-006

Rothmund J, Christmann U (2002) Auf der Suche nach einem geschlechtergerechten Sprachgebrauch: führt die Ersetzung des “generischen Maskulinums” zu einer Beeinträchtigung von Textqualitäten? Muttersprache 112:115–136

Saily T, Nevalainen T, Siirtola H (2011) Variation in noun and pronoun frequencies in a sociohistorical corpus of English. Lit. Linguistic Comput. 26:167–188. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqr004

Schmitz D, Schneider V, Esser J (2023) No genericity in sight: An exploration of the semantics of masculine generics in German. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/c27r9

Schneider C (2020) Gender-Deutsch. Textschneiderin. Available from: https://textschneiderin.ch/gender-deutsch/

Schunack S, Binanzer A (2022) Revisiting gender-fair language and stereotypes – A comparison of word pairs, capital I forms and the asterisk. Z. f.ür. Sprachwiss. 41:1–29. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfs-2022-2008

Simon HJ (2022) Sprache Macht Emotion. APuZ Aus Polit. und Zeitgesch. 5–7:16–22

Sökefeld C (2021) Gender(un)gerechte Personenbezeichnungen: derzeitiger Sprachgebrauch, Einflussfaktoren auf die Sprachwahl und diachrone Entwicklung. Sprachwissenschaft 46:111–141

Sökefeld C, Andresen M, Binnewitt J, Zinsmeister H (2023) Personal Noun Detection for German. In: Proceedings of the 19th Joint ACL - ISO Workshop on Interoperable Semantic Annotation (ISA-19). Nancy, France. Available from: https://sigsem.uvt.nl/isa19/ISA-19-proceedings.pdf

Speyer LG, Schleef E (2019) Processing ‘Gender-neutral’ Pronouns: A Self-paced Reading Study of Learners of English. Appl. Linguist. 40:793–815. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amy022

Stede M (Ed.) (2016) Handbuch Textannotation: Potsdamer Kommentarkorpus 2.0. Universitätsverlag, Potsdam

Stefanowitsch A, Middeke K (2023) Gender-Marking -ess: The Suffix that Failed. Z. f.ür. Anglistik und Amerikanistik 71:293–319. https://doi.org/10.1515/zaa-2023-2029

Steinhauer A, Diewald G (2017) Richtig gendern: Wie Sie angemessen und verständlich schreiben. Duden, Berlin

Thorne N, Aldridge Z, Yip AK-T, Bouman WP, Marshall E, Arcelus J (2023) I Didn’t Have the Language Then’—A Qualitative Examination of Terminology in the Development of Non-Binary Identities. Healthcare 11:960. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11070960

Trutkowski E, Weiß H (2023) Zeugen gesucht! Zur Geschichte des generischen Maskulinums im Deutschen. Linguistische Ber. 273:5–39

Völkening L (2022) Ist Gendern mit Glottisverschlusslaut ungrammatisch? Ein Analysevorschlag für das Suffix [?in] als phonologisches Wort. Z. f.ür. Wortbild./J. Word Formation 6:58–80. https://doi.org/10.3726/zwjw.2022.01.02

Waldendorf A (2023) Words of change: The increase of gender-inclusive language in German media. European Sociological Review: 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcad044

Web editorial staff of the LpB BW (2023) Gendern: Pro und Contra - Die Debatte im Überblick. lpb - Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg. Available from: https://www.lpb-bw.de/gendern#c76345

Zacharski L, Ferstl EC (2023) Gendered Representations of Person Referents Activated by the Nonbinary Gender Star in German: A Word-Picture Matching Task. Discourse Process. 60:294–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2023.2199531

Zeng Y (2023) Gender-neutrality in Written Discourse. A newspaper-based diachronic comparison study of gender-neutral vocabular. Stockholms universitet. Independent Degree Project at Undergraduate Level English Linguistic Available from: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1784497/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Zifonun G (2018) Die demokratische Pflicht und das Sprachsystem: erneute Diskussion um einen geschlechtergerechten Sprachgebrauch. Sprachreport 34:44–56

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: CM-S, SO, SW, AK; Data curation: SO, SW, JOR; Formal Analysis: SO, SW; Investigation: CM-S, SO; Methodology: CM-S, SO, AK, JOR, SW; Software: JOR; Visualization: SO, SW; Writing – original draft: CM-S, SO; Writing – review & editing: CM-S, SO, AK, JOR, SW.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Müller-Spitzer, C., Ochs, S., Koplenig, A. et al. Less than one percent of words would be affected by gender-inclusive language in German press texts. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1343 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03769-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03769-w