Abstract

Recent reports from climate scientists stress the urgency to implement more ambitious and stringent climate policies to stay below the 1.5 °C Paris Agreement target. These policies should simultaneously aim to ensure distributional justice throughout the process. A neglected yet potentially effective policy instrument in this context is rationing. However, the political feasibility of rationing, like any climate policy instrument, hinges to a large extent on the general public being sufficiently motivated to accept it. This study reports the first cross-country analysis of the public acceptability of rationing as a climate policy instrument by surveying 8654 individuals across five countries—Brazil, Germany, India, South Africa, and the US—on five continents. By comparing the public acceptability of rationing fossil fuels and high climate-impact foods with consumption taxes on these goods, the results reveal that the acceptability of fossil fuel rationing is on par with that of taxation, while food taxation is preferred over rationing across the countries. Respondents in low-and middle-income countries and those expressing a greater concern for climate change express the most favourable attitudes to rationing. As political leaders keep struggling to formulate effective and fair climate policies, these findings encourage a serious political and scientific dialogue about rationing as a means to address climate change and other sustainability-related challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The formal recognition of the need to transition away from fossil fuels in the first global stocktake agreed upon at the recent 28th UNFCCC Conference of the Parties (COP28) in Dubai sends a strong political signal (UNFCCC, 2023). However, the agreement is flawed by “a litany of loopholes” (AOSIS, 2023) and explicit language on fossil fuels is long-overdue (Nature Editorial, 2023). In parallel, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) underscores the need for transformative action to rapidly reduce emissions and enhance the probability of limiting global warming to 2 °C (IPCC, 2023). In the absence of decisive governmental action, the rapidly shrinking and remaining carbon budget compatible with the goals of the Paris Agreement will soon be exhausted (Friedlingstein et al., 2023; Lamboll et al., 2023). This increasing scarcity of permissible carbon emissions substantiates a need to innovatively consider all policies capable of rapidly reducing emissions. An imperative that comes with the additional responsibility of ensuring distributional justice in the process (McCauley & Heffron, 2018; Zimm et al., 2024).

A potentially effective policy instrument in this context is rationing. Although mostly neglected in climate policy discussions and research, rationing is a commonly employed policy instrument to manage scarce resources. It has been applied to managing energy shortages (Souza & Soares, 2007), addressing water scarcity during droughts (Olmstead & Stavins, 2009), and decreasing local air pollution through odd-even-day traffic restrictions (Guerra et al., 2022). Fishing quotas function in a similar way, with catch shares distributed below an upper absolute cap to curtail overfishing (Birkenbach et al., 2017). In the context of climate policy, a rationing scheme could provide all citizens with allowances to consume particularly emissions-intensive goods below an upper cap. Fossil fuels like petrol and diesel and high climate-impact foods such as meat are obvious targets due to their substantial climate impact (Dubois et al., 2019; Ivanova et al., 2020).

Rationing holds several features rendering it a potentially effective policy instrument to facilitate a just low-carbon transformation. Rationing fixes the consumption of certain emissions-intensive goods by establishing an absolute quantitative cap, making it a predictable demand-side approach to achieve emissions reductions (Alcott, 2010; Creutzig et al., 2018). Furthermore, the instrument could ensure a just distribution of essential (emissions-intensive) goods and thus reduce the risk of potentially adverse social implications of restrictions on their consumption (Wood et al., 2023). Personal carbon trading (PCT) schemes, in which emission allowances are distributed annually to citizens under a shrinking absolute cap, function in a similar manner and have gained theoretical attention (Fuso Nerini et al., 2021). However, the administrative costs and technological capacities necessary to monitor all personal carbon emissions make such schemes challenging (Grubb et al., 2022). PCTs also disregard important political economy arguments suggesting that sector-specific policies more effectively could induce behavioural and organisational change, as these can be tailored to encourage innovation and reduce consumption in sectors resistant to change (Grubb et al., 2023).

In the formulation of rationing schemes, it is key to recognise that decisions around which goods to target, principles to employ in allocating allowances, and whether allowances are tradable or not, generate different outcomes in terms of justice, cost-effectiveness (Hepburn, 2006) and public attitudes like policy acceptance (Kyselá et al., 2019). Indeed, the political feasibility of rationing depends to a large extent on the general public being sufficiently motivated to accept it. The expression of dismissive attitudes towards climate policies across contexts and jurisdictions is becoming an increasing challenge for political leaders. Consider carbon pricing. While performing well in certain contexts and often defended as indispensable to any successful climate policy package (van den Bergh & Botzen, 2020), carbon pricing instruments have attracted public opposition during their implementation and expansion (Carattini et al., 2018; Maestre-Andrés et al., 2019), leading to failed policy adoption and even repeals after elections (Douenne & Fabre, 2022; Raymond, 2020). Much of the opposition to carbon pricing instruments stems from public concerns around their perceived high cost and unfairness (Povitkina et al., 2021). Although certain design features like revenue recycling may alleviate some opposition (Jagers et al., 2021; Klenert et al., 2018), real-world evidence raises questions about their actual impact on public acceptance (Fremstad et al., 2022; Mildenberger et al., 2022). Given the importance of public acceptability before and public acceptance after policy implementation (Kyselá et al., 2019), analyses of climate policy attitudes can provide valuable information to politicians who are reluctant to propose and enact policies they anticipate will face public backlash (Burstein, 2003; Page & Shapiro, 1983). While individuals generally favour ‘pull’ instruments like low-carbon subsidies over ‘push’ instruments like carbon pricing (Drews & van den Bergh, 2016) (and presumably also rationing), research has yet to assess the public acceptability of rationing as a climate policy instrument.

Here, we survey 8654 people from five major economies—Brazil, Germany, India, South Africa, and the US—on five continents. The aim of this study is threefold. We (1) compare the public acceptability of rationing fossil fuels and high climate-impact foods with consumption taxes on these goods, (2) compare levels of policy acceptability across the countries and (3) look more specifically at rationing to explore whether sociodemographic factors, climate change concern, and habits influence attitudes towards rationing on both an aggregated and country-specific level. In conclusion, we discuss the results and their implications for policy and future research. In doing so we report the first cross-country analysis of the public acceptability of rationing as a climate policy instrument.

With respect to the third aim, we purposely limit our analysis to basic individual-level factors and climate change concerns, recognising that past research has shown that a variety of factors influence public attitudes towards climate policies (Bergquist et al., 2022; Fairbrother, 2022). This choice is motivated by the fact that, as far as we know, no studies have assessed public attitudes towards climate-motivated rationing in a multi-country setting. And since specific policy attributes influence policy attitudes (Coleman et al., 2023), one should be careful to extrapolate findings across policies. Examining whether attitudes towards rationing are influenced by well-researched and rather stable factors is therefore a reasonable point of departure.

The countries included in this study differ with respect to per capita CO2 emissions as well as meat and fossil fuel consumption (Table 1). Yet, they all emit high levels of emissions on the aggregate and are, except for India, the countries with the highest level of emissions on their respective continent. Moreover, the size of the countries’ economies renders them important actors in a global perspective as they shape global production and consumption systems through domestic policy and demand. Conducting the analysis on these countries allows us to explore individual attitudes towards rationing and taxation in high-emitting countries that differ with respect to economic development, fossil fuel consumption, and meat consumption, as well as political and cultural aspects.

To be clear, while much can be learned about people’s attitudes from survey research, there are inherent issues to be aware of with such approaches, like social desirability biases and measurement errors (Stantcheva, 2023). Besides, public opinion studies do not always accurately predict real-world behaviour, since behaviours are influenced by the specific context, time, and place in which they occur (Ajzen, 1991, 2011). Although we have followed best-practice recommendations in survey design and analysis (see Methods), the results reported should not be interpreted as actual attitudes towards rationing or taxation. Therefore, we follow the framework proposed by Kyselá et al. (2019) and use ‘acceptability’ to denote a positive yet passive attitude towards a hypothetical policy instrument that could lead to actual policy support.

Methods

The online surveys used in this study were part of a larger research project. Beyond the questions analysed in this study, respondents answered questions about other climate policies targeting food consumption and transportation. They were carried out by YouGov in 2023 and fielded in Brazil, Germany, and India between January 17th and January 30th, in the US between January 17th and February 2nd, and in South Africa between January 18th and February 2nd, and administered in an official language of each country. These countries were selected to reflect different characteristics with regard to political, cultural, and socioeconomic systems, fossil fuel consumption (Our World in Data, 2024), and food consumption (FAO, 2023). We included five countries from five continents to counter the overwhelming focus on Europe and North America in the climate policy acceptance literature.

Sample and data collection

Respondents were drawn from YouGov’s proprietary panels in each country and participation was restricted to individuals 18 years or older. YouGov ensured that informed consent was obtained. The proprietary sampling methodology used by YouGov to collect survey data is based on quota criteria on key demographics—gender, region, and age—derived from population census data from each country. The sampling software controls and selects panellists for the survey guided by the quota frame to ensure that the study sample mirrors the distribution of the countries’ censuses. Since samples are selected according to quota criteria, the probability for each potential individual to be included is determined by the quotas. Although the final sample is weighed on sociodemographic factors and region (see Section 3 in the Supplementary for complete details), the sample is not perfectly representative of the censuses of the countries and caution is therefore due in generalising the findings to the wider population. The exact sample sizes for each country were: Brazil, n = 1697; Germany, n = 1818; India, n = 1647; South Africa, n = 1754; and the US, n = 1738 (see Section 1 in the Supplementary for descriptive statistics).

Statistical analysis

We requested respondents to evaluate four policy proposals including rationing of high climate-impact food and fossil fuels and taxation of the same goods. Respondents answered the question item: ‘What is your opinion about the following proposals on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is Strongly against and 5 is Strongly in favour?’. Figure 1 shows the share of respondents with positive answers (‘Strongly in favour’ and ‘Somewhat in favour’). Two-tailed t-tests with unequal variances were used to compare the public acceptability of the policy proposals and the standard significant level of P < 0.05 criterion was used to establish mean differences. See Tables S2.1 and S2.2 in the Supplementary for statistical analyses. We included individual-level determinants demonstrated by previous research to influence climate policy acceptability including climate change concerns, sociodemographic factors, and habits (Drews & van den Bergh, 2016). The selection of determinants reflects the aim of this study; to examine whether common and relatively stable individual-level factors influence respondents’ acceptability of taxation and, in particular, rationing. We employed ordinary least-squares regression models with robust standard errors to assess the effects of these determinants on policy acceptability and used standardised coefficients to allow comparisons between the determinants. Ordered logistic regression models were employed to test the robustness of the effects of the determinants on public acceptability (see Table S4.1 in the Supplementary). To ensure the data quality, we compared the reported answers against answers from respondents who completed the survey within one standard deviation’s time from the mean completion time, finding no differences (see Table S4.2 in the Supplementary).

Results

Our survey includes over 1600 respondents in each country with inquiries focused on their attitudes toward the four policy proposals (see ‘Methods’ for complete details).

Public acceptability of rationing and taxation of high climate-impact foods and fossil fuels

Across the full sample, 38% of the respondents accept fossil fuel rationing (monthly limits on fossil fuel purchases), 39% accept fossil fuel taxation, 33% accept high climate-impact food rationing (monthly limits on meat purchases) and 44% accept taxation on high climate-impact foods (Fig. 1). These results are supported by statistical tests. Comparable levels of acceptability are reported for fossil fuel rationing and taxation, while food taxation enjoys higher levels of acceptability compared to food rationing. No statistically significant differences are found when t testing means (M) differences (Difference-in-Means (DIM) = −0.003, t(17,306) = −0.4061, P = 0.6847) between fossil fuel rationing (M = 0.384, s.d. = 0.486) and fossil fuel taxation (M = 0.387, s.d. = 0.487). However, the difference between high climate-impact food taxation and rationing is statistically significant (DIM = −0.108, t(17,258.2) = −14.6281, P = 0.0000) with respondents expressing more positive attitudes to taxation (M = 0.439, s.d. = 0.496) compared to rationing (M = 0.332, s.d. = 0.471) (see Supplementary Table S2.1 for details).

Cross-country comparison of public acceptability

When considering the results for each country separately, differences between levels of acceptability of the various policy proposals become more pronounced (Fig. 1). Fossil fuel rationing and taxation receive similar levels of acceptability across the countries. When t testing means differences between fossil fuel rationing and taxation in all countries, we only observe statistically significant differences in the US, where taxation is preferred over rationing (DIM = −0.039, t(3,470) = −2.4875, P = 0.0129). Rationing appeals to a greater extent among respondents in South Africa (49%) and India (46%) compared to the US (29%) and Germany (29%) with Brazil (40%) falling in between. Similar differences are evident with regard to the public acceptability of fossil fuel taxation. These contextual differences indicate that the public acceptability of rationing (and taxation) is subject to contextual constraints. This assumption is strengthened when looking at the proportion of respondents being ‘strongly against’ the policy proposals. In the US, a substantial and equally large proportion of respondents is ‘strongly against’ fossil fuel rationing (28%) and fossil fuel taxation (28%). In Germany, the share of respondents ‘strongly against’ fossil fuel taxation (30%) is even greater than the share who are ‘strongly against’ fossil fuel rationing (27%). Respondents ‘strongly against’ the policy proposals are considerably smaller in India and South Africa (see Supplementary Table S1.3).

When looking at high climate-impact foods, differences between the public acceptability of rationing and taxation become more distinct. Taxation emerges as the most preferred option in all countries, though only slightly so in India. Differences in acceptability levels in favour of taxation are statistically significant for all countries except India (DIM = −0.031, t(3,291.96) = −1.7803, P = 0.0751). Similar to fossil fuel rationing, higher levels of acceptability for food rationing emerge in South Africa (42%) and India (46%) compared to the US (22%), Germany (26%) and Brazil (31%). Differences in acceptability for food rationing and taxation are, compared to the other countries, particularly apparent in Germany (DIM = −0.164, t(3,581.37) = −10.6287, P = 0.0000) and Brazil (DIM = −0.148, t(3,373.79) = −8.9552, P = 0.0000). Compared to taxation, the share of respondents ‘strongly against’ high climate-impact food rationing is particularly obvious in the US (36%) and Germany (35%) (See Supplementary Table S1.3).

Individual-level determinants of public acceptability of rationing

As a next step, we analyse the variation in attitudes among socioeconomic groups and the extent to which climate change concerns and habits influence these levels. We ask respondents about their socioeconomic characteristics (gender, age, educational attainment, place of residence, and personal income), degree of climate change concern, and habits (car ownership, daily driving, meat consumption, and daily meat consumption) (See Supplementary Section 5 for details).

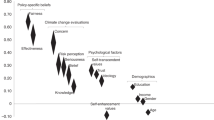

In the all-country model, higher acceptability levels for both rationing instruments are found among younger, more educated, and urban respondents (Fig. 2 and enlarged figures in Supplementary section 2). Climate change concern emerges as a strong driver of acceptability for both fossil fuel rationing (0.403***) and high climate-impact food rationing (0.319***). Although identifying as a woman increases acceptability for both rationing instruments, the influence of gender is only statistically significant for fossil fuel rationing (0.0556***). Notably, personal income has no significant effect on acceptability across the countries. Regarding habits, daily car usage has a negative and significant effect on acceptability (−0.0972***), while car ownership does not influence acceptability levels. Being a meat-eater has a stronger negative influence on acceptability (−0.165***) compared to daily meat consumption (−0.103***). It should be noted that the determinants included in our analysis only explain a small share of the respondents’ attitudinal variation (R-squared value for fossil fuel rationing = 0.142 and for high climate-impact food rationing = 0.127).

When examining the influence of the individual-level determinants separately for each country, climate change concern stands out as the only significant and positive determinant of acceptability for both types of rationing in all countries. The effects of sociodemographic factors and habits are more diverse. For example, age has a negative effect on acceptability for both rationing instruments in South Africa and the US, while being older positively influences the acceptability of fossil fuel rationing in India. Rural respondents, compared to their urban counterparts, express lower levels of acceptability for both rationing types in South Africa and the US, while the influence of residence is non-significant in Germany and Brazil and mixed in India. Similar to the all-country model, income has an insignificant effect on acceptability for both rationing instruments. Daily car usage has a stronger and significant negative effect on the acceptability of fossil fuel rationing compared to car ownership in all countries except South Africa and Germany. Eating meat daily is a stronger negative driver of food rationing acceptability compared to simply being a meat-eater in India, while the latter negatively and to a greater extent influences acceptability in Brazil and Germany.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that, in five diverse countries, the public acceptability for climate-motivated rationing is comparable to that of taxation. However, the acceptability of rationing in our sample is sensitive to context and good targeted. While fossil fuel taxation and rationing receive similar levels of acceptability, taxation of high climate-impact food is preferred over rationing of the same good. The lower levels of acceptability reported for food rationing, compared to fossil fuel rationing, may be attributed to a strong cultural embeddedness of food, respondents’ perception of food as a nutritional necessity, and a lack of awareness regarding the climate impact of food (Fesenfeld et al., 2020). Although differences in acceptability of food rationing and taxation are pronounced in Brazil and Germany, these differences are fairly small in India, South Africa, and the US. Interestingly, the proportion of respondents ‘strongly against’ fossil fuel rationing is similar (the US) or smaller (Germany) than the proportion of respondents ‘strongly against’ fossil fuel taxation. This implies that strong policy aversion need not constitute a greater barrier for rationing compared to taxation. It is however likely that the specific design of rationing (e.g. size of mandated individual reduction) and taxation (e.g. tax rate) affects individuals’ policy attitudes (Beiser-McGrath & Bernauer, 2019) and such design features were not specified in our study.

The clear cross-country differences in acceptability for both rationing instruments indicate an opportunity for rationing in low- and middle-income countries. While cross-country studies on public attitudes towards climate policies are rare, our results align with two recent studies (Dabla-Norris et al., 2023; Dechezleprêtre et al., 2022) finding higher levels of climate policy acceptability in low- and middle-income compared to high-income countries. Cross-country differences have been found in studies on attitudes toward carbon taxes (Harring et al., 2019) and climate policy packages (Wicki et al., 2019), and our results extend these findings to regulatory climate policies targeting food and transportation behaviours. Attitudinal differences towards climate policies have previously been hypothesised to be explained by, for instance, exposure to climate change effects like extreme weather events (Howe et al., 2019) and concern for climate change (Kim & Wolinsky-Nahmias, 2014). Here, we propose another potential mechanism—that the experience of resource scarcity makes people more willing to accept climate policies aimed at redistributing resources. Hence, one way to interpret the findings here is that respondents in India and South Africa are more exposed to resource scarcity, fostering an openness to accept policies designed to manage scarce resources, like rationing. On the contrary, the large proportion of respondents in Germany and the US expressing strong dismissive attitudes towards both types of rationing suggests that the instrument, if proposed, could face significant opposition in high-income countries where individuals in general are less accustomed to resource scarcity. While perceived resource scarcity has been demonstrated to promote pro-environmental behaviour (Berthold et al., 2022), the association between perceived resource scarcity and climate policy acceptability—and the strength of it—require further investigation.

Consistent with earlier studies (Bergquist et al., 2022), our findings underscore the importance of climate change concerns in predicting climate policy attitudes. However, the determinants included in our analysis only explain a small proportion of attitudinal variation. This comes as no surprise given previous evidence demonstrating that other determinants tend to strongly influence climate policy attitudes (Bergquist et al., 2022; Ejelöv & Nilsson, 2020). To better understand what factors influence attitudes towards rationing, we encourage future research to assess other determinants shown to influence climate policy attitudes, preferably using experimental approaches to allow for causal inferences. For instance, perceived fairness and effectiveness have been identified as key factors in explaining individuals’ inclination to accept stringent climate policies (Bergquist et al., 2022; Huber et al., 2020). Since rationing involves a high degree of state intervention, trust in political institutions is also likely to influence attitudes towards rationing (Kitt et al., 2021). Interestingly though, despite differences between the countries with respect to consumption, economic development, and emissions (Table 1), the factors capturing habits exhibit a rather stable and negative relationship to the acceptability of rationing across the countries. In all countries but South Africa, meat-eaters and frequent meat-eaters, as well as frequent drivers, express more dismissive attitudes towards the instrument, supporting the notion that people are concerned with how policies with clear behavioural implications affect them personally (Beiser-McGrath & Bernauer, 2024; Fanghella et al., 2023). In this context, the non-significant results for personal income are noteworthy. Again, if policy attitudes are influenced by the extent to which policies are perceived to impose personal costs, poorer respondents would reasonably express more favourable attitudes to rationing because their lower consumption volumes make them less likely to be burdened by rationing. One possible explanation for the non-significant finding for personal income is unawareness of both within- and between-country consumption inequalities (Chancel, 2022; Hubacek et al., 2017) and what rationing would actually entail in terms of consumption reductions and for whom. Although little is known about people’s awareness of such inequalities (Nielsen et al., 2024), people tend to misjudge the climate impact of various behaviours, such as meat consumption and travelling (Camilleri et al., 2019; Wynes et al., 2020). Experimental evidence also indicates that information about carbon inequality alters people’s acceptability of carbon taxation differently, depending on their place in the income distribution (Beiser-McGrath & Busemeyer, 2024). Against this backdrop, it is possible that people’s attitudes towards rationing may be altered by information about actual consumption inequality and what this entails in terms of emissions, such that poorer (richer) individuals become more positive (negative) upon receiving such information.

Since we report the first cross-country study of public attitudes toward climate-motivated rationing, caution is due when interpreting the results. Respondents’ interpretation of, and attitudes towards, rationing may be affected by public discourse around rationing in other policy fields. For instance, the contentious public debate around healthcare rationing in the US (Bhatia, 2020) could influence US respondents’ attitudes towards rationing as a climate policy instrument. Similarly, respondents’ experience with the instrument in other policy fields may impact the reported attitudes and contribute to the observed cross-country variation in acceptability levels. In India, a rationing shop scheme has been operating for over 70 years, in which households are allowed to purchase fixed quantities of certain goods, like sugar and rise, at subsidised prices (Gadenne, 2020). In Brazil and South Africa, water and electricity have been subject to rationing during droughts and blackouts. In interpreting these results, one should also be aware of potentially significant differences in respondents’ interpretation of the rationing questions and that the word ‘rationing’ may carry different connotations to people in different contexts. Although survey results are always sensitive to phrasing, this limitation is particularly important to be aware of with this survey being translated into different languages and conducted in diverse political contexts.

Having said that, a plausible interpretation of our results is that rationing may be equally accepted as taxation when applied to specific goods in certain contexts. Although additional research using representative samples from other countries is needed to validate the robustness of these results, and we advise against interpreting our results as evidence of actual support of rationing—the possible differences between our sample and the target populations discourage a generalisation of the results—they still provide preliminary empirical insights into cross-national attitudes towards rationing. This lays important groundwork on which future studies can build to make stronger inferences.

In this context, more advanced survey and laboratory experiments, as well as longitudinal studies, based on panel data and representative samples, would complement this study’s results. More generally, and in agreement with other scholars in the field (Heyen & Wicki, 2024; Kallbekken, 2023), we want to emphasise the importance of employing methodological approaches, like factorial experiments, that better mirror realistic situations and offer higher external validity. With respect to rationing in particular, we recommend future studies to conduct experiments that systematically vary principles of allowance allocation and trading mechanisms to help uncover how public attitudes towards rationing are affected by various policy design options. Relatedly, since rationing in essence is about resource distribution, future studies investigating how the provision of information about the instrument —its purpose, how it would function, and what it would involve—affects policy attitudes could provide valuable insights into public views on fairness in burden-sharing. While important work has been done to sort out the intricate and multifaceted relationship between perceived fairness and public opinion of carbon taxes (Povitkina et al., 2021; Savin et al., 2020), other mechanisms may explain perceived fairness and, in turn, acceptability of regulatory policies like rationing. The straightforwardness of the rationing principle and its focus on resource distribution makes it a useful instrument to probe such questions, for example regarding public views of fair consumption reductions and how such reductions ought to be shared. Since previous research demonstrates that bundling policies into packages may enhance the public acceptability of stringent and coercive climate policies (Fesenfeld, 2022), another avenue for future research involves examining the effects on attitudes of including rationing into policy packages. Sequencing policies by gradually increasing their stringency has also been shown to facilitate the introduction of more stringent policies at later policy stages (Pahle et al., 2018) and future research could assess whether a stepwise strengthening of rationing and policy packages including rationing, enhances its public appeal.

The rationale for advancing research on rationing is that the instrument presents at least equal, if not greater, opportunities than price-based instruments to respond to the dual challenge of rapidly reducing emissions while safeguarding distributional justice. Rationing, as it has been applied to address other issues of resource scarcity, aims to ensure a fair distribution of resources, and the instrument could be preferable to price-based alternatives if governments and the public consider price increases an unfair way of reducing consumption of essential yet emissions-intensive resources. For that reason, some scholars advocate for rationing with non-tradable allowances since such a scheme would guarantee equal access to resources regardless of individuals’ purchasing power (Wood et al., 2023). Different principles of distributive justice, like equality, need or difference, could be used to decide upon the allowance distribution in such schemes (Caney, 2010). However, this approach introduces complex distributional issues into the policy process since the distribution of resources becomes highly visible (Hepburn, 2006; Stiglitz, 2019) and since perceived fairness has been identified as the most important determinant of climate policy attitudes (Bergquist et al., 2022), rationing schemes must be designed to avoid perceptions of unfairness. One option to potentially increase the perceived fairness of rationing is to make allowances tradable. While findings do not necessarily extrapolate from one policy instrument to another, studies on PCT schemes suggest that making allowances tradable enhances public acceptability (Bristow et al., 2010). This motivates the hypothesis that rationing could be accepted to a greater extent if some form of trading is allowed.

At this point, it is important to stress that a policy instrument’s feasibility is not solely determined by public attitudes. A number of political economy constraints may inhibit policy implementation, of which the underutilisation of carbon pricing instruments is an illustrative example (Jenkins, 2014). However, the growing scientific support for shifts to consumption patterns (Meadowcroft & Rosenbloom, 2023) and demand-side measures (Creutzig et al., 2024) suggests that current climate policies should be complemented by measures targeting the personal—how we travel, eat, and consume. This will likely render public attitudes, and research on them, even more important moving forward.

The urgency to ensure a rapid and fair low-carbon transformation requires politicians, scientists, and policy experts to explore all policies capable of facilitating it. Our results indicate that public acceptability may not be an insurmountable barrier to rationing in some contexts. This prompts a serious political and scientific dialogue around rationing as a plausible climate policy instrument. From a broader sustainability perspective, rationing may also be employed to address various challenges linked to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. The intensifying scarcity of natural resources places issues of distributional justice front and centre of environmental policy. Rationing holds several features rendering it a policy instrument in merit of further investigation.

Data availability

Data for replication are available at the Harvard Dataverse, https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/0B7SWG.

Code availability

The code for the statistical analysis is available at the Harvard Dataverse, https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/0B7SWG.

References

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50(2):179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Ajzen I (2011) Is attitude research incompatible with the compatibility principle? In: Arkin R (ed.), Most underappreciated: 50 prominent social psychologists describe their most unloved work. Oxford University Press. pp. 151–154

Alcott B (2010) Impact caps: why population, affluence and technology strategies should be abandoned. J Clean Prod 18(6):552–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2009.08.001

AOSIS (2023) An incremental advance when exponential change is needed: AOSIS statement at COP28 closing plenary. https://www.aosis.org/cop28-closing-plenary-aosis-statement-on-gst-decision/. Accessed 25 July 2024

Beiser-McGrath LF, Bernauer T (2019) Could revenue recycling make effective carbon taxation politically feasible? Sci Adv 5(9):eaax3323. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aax3323

Beiser-McGrath LF, Bernauer T (2024) How do pocketbook and distributional concerns affect citizens’ preferences for carbon taxation? J Polit 86(2):551–564. https://doi.org/10.1086/727594

Beiser-McGrath LF, Busemeyer MR (2024) Carbon inequality and support for carbon taxation. Eur J Polit Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12647

Bergquist M, Nilsson A, Harring N, Jagers SC (2022) Meta-analyses of fifteen determinants of public opinion about climate change taxes and laws. Nat Clim Change 12(3):235–240. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01297-6

Berthold A, Cologna V, Siegrist M (2022) The influence of scarcity perception on people’s pro-environmental behavior and their readiness to accept new sustainable technologies. Ecol Econ 196:107399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107399

Bhatia N (2020) We need to talk about rationing: the need to normalize discussion about healthcare rationing in a post COVID-19 era. J Bioethical Inq 17(4):731–735. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-020-10051-6

Birkenbach AM, Kaczan DJ, Smith MD (2017) Catch shares slow the race to fish. Nature 544(7649):223–226. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21728

Bristow AL, Wardman M, Zanni AM, Chintakayala PK (2010) Public acceptability of personal carbon trading and carbon tax. Ecol Econ 69(9):1824–1837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.04.021

Burstein P (2003) The impact of public opinion on public policy: a review and an agenda. Polit Res Q 56(1):29–40. https://doi.org/10.2307/3219881

Camilleri AR, Larrick RP, Hossain S, Patino-Echeverri D (2019) Consumers underestimate the emissions associated with food but are aided by labels. Nat Clim Change 9(1):53–58. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0354-z

Caney S (2010) Markets, morality and climate change: what, if anything, is wrong with emissions trading? N Polit Econ 15(2):197–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563460903586202

Carattini S, Carvalho M, Fankhauser S (2018) Overcoming public resistance to carbon taxes. WIREs Clim Change 9(5). https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.531

Chancel L (2022) Global carbon inequality over 1990–2019. Nat Sustain 5(11):931–938. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-00955-z

Coleman EA, Harring N, Jagers SC (2023) Policy attributes shape climate policy support. Policy Stud J 51(2):419–437. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12493

Creutzig F, Roy J, Lamb WF, Azevedo IML, Bruine De Bruin W, Dalkmann H, Edelenbosch OY, Geels FW, Grubler A, Hepburn C, Hertwich EG, Khosla R, Mattauch L, Minx JC, Ramakrishnan A, Rao ND, Steinberger JK, Tavoni M, Ürge-Vorsatz D, Weber EU (2018) Towards demand-side solutions for mitigating climate change. Nat Clim Change 8(4):260–263. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0121-1

Creutzig F, Roy J, Minx J (2024) Demand-side climate change mitigation: where do we stand and where do we go? Environ Res Lett 19(4):040201. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ad33d3

Dabla-Norris E, Helbling T, Khalid S, Khan H, Magistretti G, Sollaci A, Srinivasan K (2023) Public perceptions of climate mitigation policies: evidence from cross-country surveys. Staff Discussion Note SDN2023/002. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Staff-Discussion-Notes/Issues/2023/02/07/Public-Perceptions-of-Climate-Mitigation-Policies-Evidence-from-Cross-Country-Surveys-528057

Dechezleprêtre A, Fabre A, Kruse T, Planterose B, Chico AS, Stantcheva S (2022) Fighting climate change: International attitudes toward climate policies. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1714. OECD Publishing, Paris

Douenne T, Fabre A (2022) Yellow vests, pessimistic beliefs, and carbon tax aversion. Am Econ J Econ Policy 14(1):81–110. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20200092

Drews S, van den Bergh JCJM (2016) What explains public support for climate policies? A review of empirical and experimental studies. Clim Policy 16(7):855–876. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2015.1058240

Dubois G, Sovacool B, Aall C, Nilsson M, Barbier C, Herrmann A, Bruyère S, Andersson C, Skold B, Nadaud F, Dorner F, Moberg KR, Ceron JP, Fischer H, Amelung D, Baltruszewicz M, Fischer J, Benevise F, Louis VR, Sauerborn R (2019) It starts at home? Climate policies targeting household consumption and behavioral decisions are key to low-carbon futures. Energy Res Soc Sci 52:144–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.02.001

Ejelöv E, Nilsson A (2020) Individual factors influencing acceptability for environmental policies: a review and research agenda. Sustainability 12(6):2404. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062404

Fairbrother M (2022) Public opinion about climate policies: a review and call for more studies of what people want. PLoS Clim 1(5):e0000030. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pclm.0000030

Fanghella V, Faure C, Guetlein M-C, Schleich J (2023) What’s in it for me? Self-interest and preferences for distribution of costs and benefits of energy efficiency policies. Ecol Econ 204:107659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107659

FAO (2023) Food Balances (-2013, old methodology and population). Food and agriculture organization of the United Nations. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/FBSH. Accessed 13 Sept 2024

Fesenfeld, L (2022) The effects of policy design complexity on public support for climate policy. Behav Public Policy. 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2022.3

Fesenfeld L, Wicki M, Sun Y, Bernauer T (2020) Policy packaging can make food system transformation feasible. Nat Food 1:173–182. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-020-0047-4

Fremstad A, Mildenberger M, Paul M, Stadelmann-Steffen I (2022) The role of rebates in public support for carbon taxes. Environ Res Lett 17(8):084040. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac8607

Friedlingstein P, O’Sullivan M, Jones MW, Zheng B (2023) Global Carbon Budget 2023. Earth Syst Sci Data 15(12):5301–5369. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-15-5301-2023

Fuso Nerini F, Fawcett T, Parag Y, Ekins P (2021) Personal carbon allowances revisited. Nat Sustain 4(12):1025–1031. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00756-w

Gadenne L (2020) Can rationing increase welfare? Theory and an application to India’s ration shop system. Am Econ J Econ Policy 12(4):144–177. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20180659

Grubb M, Jordan ND, Hertwich E, Neuhoff K, Das K, Bandyopadhyay KR, van Asselt H, Sato M, Wang R, Pizer WA, Oh H (2022) Carbon leakage, consumption, and trade. Annu Rev Environ Resour 47(1):753–795. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-120820-053625

Grubb M, Poncia A, Drummond P, Neuhoff K, Hourcade J-C (2023) Policy complementarity and the paradox of carbon pricing. Oxf Rev Econ Policy 39(4):711–730. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grad045

Guerra E, Sandweiss A, Park SD (2022) Does rationing really backfire? A critical review of the literature on license-plate-based driving restrictions. Transp Rev 42(5):604–625. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2021.1998244

Harring N, Jagers SC, Matti S (2019) The significance of political culture, economic context and instrument type for climate policy support: a cross-national study. Clim Policy 19(5):636–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2018.1547181

Hepburn C (2006) Regulation by prices, quantities, or both: a review of instrument choice. Oxf Rev Econ Policy 22(2):226–247. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grj014

Heyen DA, Wicki M (2024) Increasing public support for climate policy proposals: a research agenda on governable acceptability factors. Clim Policy 24(6):785–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2024.2330390

Howe PD, Marlon JR, Mildenberger M, Shield BS (2019) How will climate change shape climate opinion? Environ Res Lett 14(11):113001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab466a

Hubacek K, Baiocchi G, Feng K, Muñoz Castillo R, Sun L, Xue J (2017) Global carbon inequality. Energy Ecol Environ 2(6):361–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40974-017-0072-9

Huber RA, Wicki ML, Bernauer T (2020) Public support for environmental policy depends on beliefs concerning effectiveness, intrusiveness, and fairness. Environ Polit 29(4):649–673. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1629171

IPCC (2023) In: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 35–115

Ivanova D, Barrett J, Wiedenhofer D, Macura B, Callaghan M, Creutzig F (2020) Quantifying the potential for climate change mitigation of consumption options. Environ Res Lett 15(9):093001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab8589

Jagers SC, Lachapelle E, Martinsson J, Matti S (2021) Bridging the ideological gap? How fairness perceptions mediate the effect of revenue recycling on public support for carbon taxes in the United States, Canada and Germany. Rev Policy Res 38(5):529–554. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12439

Jenkins JD (2014) Political economy constraints on carbon pricing policies: what are the implications for economic efficiency, environmental efficacy, and climate policy design? Energy Policy 69:467–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2014.02.003

Kallbekken S (2023) Research on public support for climate policy instruments must broaden its scope. Nat Clim Change 13(3):206–208. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01593-1

Kim SY, Wolinsky-Nahmias Y (2014) Cross-national public opinion on climate change: the effects of affluence and vulnerability. Glob Environ Polit 14(1):79–106. https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00215

Kitt S, Axsen J, Long Z, Rhodes E (2021) The role of trust in citizen acceptance of climate policy: Comparing perceptions of government competence, integrity and value similarity. Ecol Econ 183:106958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.106958

Klenert D, Mattauch L, Combet E, Edenhofer O, Hepburn C, Rafaty R, Stern N (2018) Making carbon pricing work for citizens. Nat Clim Change 8(8):669–677. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0201-2

Kyselá E, Ščasný M, Zvěřinová I (2019) Attitudes toward climate change mitigation policies: A review of measures and a construct of policy attitudes. Clim Policy 19(7):878–892. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1611534

Lamboll RD, Nicholls ZRJ, Smith CJ, Kikstra JS, Byers E, Rogelj J (2023) Assessing the size and uncertainty of remaining carbon budgets. Nat Clim Change 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01848-5

Maestre-Andrés S, Drews S, van den Bergh J (2019) Perceived fairness and public acceptability of carbon pricing: a review of the literature. Clim Policy 19(9):1186–1204. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1639490

McCauley D, Heffron R (2018) Just transition: Integrating climate, energy and environmental justice. Energy Policy 119:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.04.014

Meadowcroft J, Rosenbloom D (2023) Governing the net-zero transition: strategy, policy, and politics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 120(47):e2207727120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2207727120

Mildenberger M, Lachapelle E, Harrison K, Stadelmann-Steffen I (2022) Limited impacts of carbon tax rebate programmes on public support for carbon pricing. Nat Clim Change 12(2):141–147. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01268-3

Nature Editorial (2023) COP28: The science is clear—fossil fuels must go. Nature 624(7991):225–225. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-03955-x

Nielsen KS, Bauer JM, Debnath R, Emogor CA, Geiger SM, Ghai S, Gwozdz W, Hahnel UJJ (2024) Underestimation of personal carbon footprint inequality in four diverse countries. Nat Clim Change 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-02130-y

Olmstead SM, Stavins RN (2009) Comparing price and nonprice approaches to urban water conservation. Water Resour Res 45(4). https://doi.org/10.1029/2008WR007227

Our World in Data (2024) Energy Institute—Statistical Review of World Energy (2024); Population based on various sources (2023)—with major processing by Our World in Data. “Fossil fuel consumption per capita” [dataset]. Energy Institute, “Statistical Review of World Energy”; Various sources, “Population” [original data]. https://ourworldindata.org/fossil-fuels. Accessed 25 July 2024

Page BI, Shapiro RY (1983) Effects of public opinion on policy. Am Polit Sci Rev 77(1):175–190. https://doi.org/10.2307/1956018

Pahle M, Burtraw D, Flachsland C, Kelsey N, Biber E, Meckling J, Edenhofer O, Zysman J (2018) Sequencing to ratchet up climate policy stringency. Nat Clim Change 8(10):861–867. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0287-6

Povitkina M, Carlsson Jagers S, Matti S, Martinsson J (2021) Why are carbon taxes unfair? Disentangling public perceptions of fairness. Glob Environ Change 70:102356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102356

Raymond L (2020) Carbon pricing and economic populism: the case of Ontario. Clim Policy 20(9):1127–1140. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1782824

Savin I, Drews S, Maestre-Andrés S, Van Den Bergh J (2020) Public views on carbon taxation and its fairness: a computational-linguistics analysis. Clim Change 162(4):2107–2138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02842-y

Souza LR, Soares LJ (2007) Electricity rationing and public response. Energy Econ 29(2):296–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2006.06.003

Stantcheva S (2023) How to run surveys: a guide to creating your own identifying variation and revealing the invisible. Annu Rev Econ 15:205–234. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-091622-010157

Stiglitz JE (2019) Addressing climate change through price and non-price interventions. Eur Econ Rev 119:594–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2019.05.007

UNFCCC (2023) Outcome of the first global stocktake. FCCC/PA/CMA/2023/L.17. https://unfccc.int/documents/636608. Accessed 24 Jul 2024

van den Bergh J, Botzen W (2020) Low-carbon transition is improbable without carbon pricing. PNAS 117(38):23219–23220. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2010380117

Wicki M, Fesenfeld L, Bernauer T (2019) In search of politically feasible policy-packages for sustainable passenger transport: Insights from choice experiments in China, Germany, and the USA. Environ Res Lett 14(8):084048. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab30a2

Wood N, Lawlor R, Freear J (2023) Rationing and climate change mitigation. Ethics Policy Environ 27(1):1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/21550085.2023.2166342

World Bank (2023) GDP per capita (current US$) [Dataset]. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD. https://data.worldbank.org. Accessed 25 July 2024

Wynes S, Zhao J, Donner SD (2020) How well do people understand the climate impact of individual actions? Clim Change 162(3):1521–1534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02811-5

Zimm C, Mintz-Woo K, Brutschin E, Hanger-Kopp S, Hoffmann R, Kikstra JS, Kuhn M, Min J, Muttarak R, Pachauri S, Patange O, Riahi K, Schinko T (2024) Justice considerations in climate research. Nat Clim Change 14(1):22–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01869-0

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for financial support from Formas—the Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development, 2019-00916, 2019-02005, the Swedish Research Council, 2016-03058, and Mistra (DIA 2019/28)–Formas (2021-00416). Thanks to Elisabeth Schultz for raising the topic of rationing decades ago.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Uppsala University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OL and SCJ initiated the study. MK acquired funding for the research and SCJ acquired funding for data collection. SCJ and EE designed the survey. OL, SCJ, and MK conceptualised the study and interpreted the results. EE performed the analyses and implemented the data presentation and visualisation with contributions from OL and SCJ. All authors discussed the findings and commented on the paper. Finally, OL wrote the main manuscript with contributions from SCJ and MK.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was performed according to the guidelines provided by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority. Approval was granted by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority on November 3rd, 2022, before data collection started (No. Dnr 2022-05294-01). All involved researchers are allowed full access to all collected data, according to the decision by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority.

Informed consent

YouGov obtained written informed consent from all participants as of their registration to become a member of the YouGov panels. The approval gives consent to participation, and data usage by all involved researchers, and permits to publication of collected data. In the distributed survey, all participants were fully informed about how their anonymity is assured, the motivation behind the study, how the collected data will be utilised, and an explanation of the risks associated with responding to the survey. All participants are 18 years or older.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lindgren, O., Elwing, E., Karlsson, M. et al. Public acceptability of climate-motivated rationing. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1252 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03823-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03823-7