Abstract

The emergence of social media has greatly enriched the channels and sources of information through which individuals interact. However, there remains a lack of empirical research on its actual impact on personal safety. This study employed both Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) and network analysis to explored the mechanisms by which social media engagement affects safety perceptions. Additionally, it examined gender differences from both micro-level perspectives (including general trust and perceived social support) and macro-level viewpoints (including personal belief in a just world). The findings revealed that perceived social support, general trust, and personal belief in a just world played a fully mediating role. A multi-group analysis indicated that males were more susceptibility to the influence of social media engagement, with their general trust exhibiting negligible impact on perceived safety. Consequently, this study argues that attention should be given not only how social media affects personal beliefs and safety perceptions, but also its impact on behavioral outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Research background

Safety perceptions are cognitive response triggered when individuals perceive external danger and feel threatened (Bar‐Tal and Jacobson 1998). Those with lower perceived safety exhibit poor social adaptability (Ye et al. 2021), tend to restrict their range of activities, and are less likely to engage in physical activity, especially at night, which subsequently impacts their participation in social affairs (Foster and Giles-Corti 2008; Tandogan and Ilhan 2016). Furthermore, significant gender differences may exist in the evaluation and perception of environmental safety. Compare to males, females are more likely to perceive higher levels of criminal activity and reduced social cohesion, thereby diminishing their perceived safety (Johansson and Haandrikman 2023). These differing perspectives on safety between genders may pose challenges to policy formulation and enlarge gender conflicts, necessitating a deeper investigation into the mechanisms that shape safety perceptions. The widespread use of social media has been found to negatively impact people’s physical and mental health (Alonzo et al. 2020; Lee et al. 2022). In particular, social media depictions of crimes greatly increase generalized fear of crime (Zeng and Wong 2023) and reduce individuals’ safety perceptions. However, there remains a lack of research in this area, and further exploration is needed to understand the relationship between social media engagement and safety perceptions, including the underlying mechanisms and gender differences.

Literature review

In the past, individuals’ assessments of environment safety were significantly shaped by personal experiences and the information surrounding them. For example, those who perceive themselves as vulnerable to criminal victimization exhibit heightened fear of crime (Singer et al. 2019). Even people who seldom go out may regard the external world as unsafe if their acquaintances or neighbors express negative perceptions of society (Allik and Kearns 2017). Moreover, the Internet has become an essential source of individuals’ awareness of global developments and current social issues. As of December 2023, China has 1.092 billion Internet users, with a penetration rate of 77.5 and 97% of these users engage in online entertainment and communication (The 53rd statistical report on China’s internet development 2024). The information available to people, especially through media channels, largely influences their safety perceptions.

Social media serves as a comprehensive term for digital platforms that facilitate the creation and spread of user-generated content, including web platforms (e.g., Facebook, microblogs), online forums, and instant messaging applications (e.g., WhatApp and Wechat) (Gunitsky 2015; Zeng and Wong 2023). It provides a channel for individuals to discuss current events, which can subsequently alter their opinions and beliefs. As proposed by cultivation theory, the content presented on social media significantly influences and shapes people’s perceptions (Morgan and Shanahan 2010). Compared to traditional media like newspapers and television, social media platforms such as Facebook and WeChat offer a broader spectrum of information, including negative information (Zhang et al. 2013). Negative stimuli tend to attract more attention and more likely to be shared and spread (Fay et al. 2021). Exposure to information on social media that threatens personal safety can provoke increased concern for one’s own safety. In particular, awareness that criminal or suicidal events may lead to copycat behaviors greatly increases feelings of threat and fear of crime (Ueda et al. 2017). Furthermore, numerous studies have confirmed the correlation between social media consumption and heightened levels of fear (Intravia et al. 2017; Wu et al. 2019; Zeng and Wong 2023). Consequently, social media amplifies the visibility of dangerous criminal incidents, potentially heightening safety concerns.

Perceived safety is also influenced by social support. Perceived social support refers to the extent to which individuals receive assistance or understanding from family, friends and other significant others when they require help (Zimet et al. 1988). It not only enhances life satisfaction and reduces loneliness (Yue et al. 2023), but also mitigates the effects of depression on the quality of life of older adults with physically unwell (Kong et al. 2019). Moreover, studies have found that individuals with higher levels of social support perceive greater levels of safety, thereby reducing the incidence of dating violence (Jankowiak et al. 2020; Valente and Crescenzi-Lanna 2022). They also typically possess a stronger sense of self-efficacy (Luo et al. 2023) and exhibit greater confidence in facing external challenges, leading to increased safety perceptions. When social media promotes social support, it is associated with more positive coping strategies and lower threat assessments (Cho et al. 2023). Therefore, social support may enhance safety perceptions.

Various social media platforms have facilitated communication across temporal and spatial boundaries, enriching and sustaining relationships while enhancing social connections. Individuals can maintain contact with family, friends, and acquaintances through social media, freely disseminating information and engaging in instant interactions, thereby bolstering their sense of belonging and identity (Van Bavel et al. 2024), which in turn enhances their perceived social support (Häusser et al. 2023; Penfold and Ogden 2023). Longitudinal studies demonstrate that social media engagement enhances social support among older adults, alleviating loneliness (Zhang et al. 2021). Conversely, problematic social media use diminishes social support, negatively affecting well-being and mental health quality of life (Lin et al. 2021). In addition, research indicates that consuming information on social media can influence safety perceptions, but not necessarily perceived social support; conversely, active participation through posting and commenting enhances perceived social support (Yang et al. 2020). Consequently, social media engagement may indirectly influence safety perceptions through perceived social support.

People’s trust in others and their surroundings significantly impacts their perception of safety. General trust, the belief in the inherent goodness of human nature and not limited to a specific entity (Yamagishi and Yamagishi 1994), is crucial for the well-being of the elderly. This trust positively predicts physical well-being (Sato et al. 2018) and is associated with lower levels of depression and anxiety (Lin et al. 2021). Compared to individuals with lower general trust, those with higher general trust perceive lower risk (Siegrist et al. 2021) and tend to perceive the external environment as safer. General trust is also believed to indirectly reduce suicidal ideation by alleviating insomnia and fear of COVID-19 (Lin et al. 2022). Trust in others and the police has been found to reduce the fear of crime (Valente and Vacchiano 2021). In addition, Trust Transfer Theory posits that individuals exhibit varying degrees of trust in specific objects due to differences in their characteristics and familiarity with them, and that trust can be transferred from a known entity to an unknown one (Stewart 2003). Trust in political institutions enhancing individuals’ safety perceptions (Spadaro et al. 2020). Moreover, research suggests a reinforcing relationship between general trust and political trust (Bargsted et al. 2023), which may extend to safety perceptions. Collectively, these studies suggest that general trust significantly influences an individual’s perceived safety.

Given the diverse and often inconsistent quality of information sources on social media, skepticism about their reliability may arise, subsequently affecting general trust. For example, depictions of norm-violating behaviors, such as robbery, on social media can diminish general trust (Van Lange 2015). Problematic social media use has been found to negatively impact well-being and psychological health by undermining general trust and social support (Lin et al. 2021). However, Social Capital Theory proposes that individuals can use social networks not only to gain support and resources, but also to cultivate trust with others (Fulkerson and Thompson 2008). Study has identified a positive correlation between social media use and perceived general trust (Sun et al. 2023). During the COVID-19 pandemic, social media significantly enhanced individuals’ social trust (Liu and Yang 2021; Pan and Luo 2022). Moreover, longitudinal studies indicate that social media can mitigate the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in individuals with higher levels of general trust (He et al. 2018). Therefore, social media engagement may indirectly influence perceived safety through its impact on general trust.

Furthermore, individuals’ attitudes towards the external environment can affect the safety perceptions. Beliefs in a just world (BJW) reflect the conviction that people ultimately receive what they deserve. This concept is divided into general belief in a just world (GBJW) and personal belief in a just world (PBJW) (Lipkusa et al. 1996). Individuals with PBJW attribute a greater sense of justice to the world than those with higher GBJW (Dalbert, 1999). Such beliefs not only enhance overall well-being but also alleviate depressive symptoms (Jiang et al. 2016). According to the Just World Belief Theory, belief in a just world enhances predictability and control over life (Lerner 1980), thereby boosting confidence in facing difficulties. Conversely, Individuals with lower levels of PBJW experience a lower sense of control (Fischer and Holz 2010) and are more likely to feel incapable of coping with external difficulties. Moreover, individuals with higher PBJW perceive lower levels of individual and group discrimination (Choma et al. 2012), have better protection against external risks (Dalbert and Donat 2015), and are more likely to view the external environment as safe (Ma et al. 2022). Thus, individuals with higher levels of PBJW also report higher levels of perceived safety.

In recent years, social media has become a powerful tool for victims to voice their grievances and for individuals to assertively defend their rights and interests, ensuring that perpetrators are held accountable (Malik et al. 2022). This mechanism significantly upholds the sense of justice for both victims and the public. Similarly, political institutions also use social media to publicize violations of social norms and beliefs, imposing appropriate penalties (Lee and Wei 2021). Interactions on social media platforms can shape individuals’ attitudes toward life events, thereby influencing their PBJW (Shin and Hampton 2023). Moreover, the dissemination of violent narratives on social media has been found to amplify negative cognitive biases and strengthen beliefs in a just world (Naderer et al. 2024). Consequently, social media engagement may also indirectly influence safety perceptions through PBJW.

In summary, social media may indirectly affect perceived safety through social support, general trust, and personal belief in a just world. The vulnerability model suggests that perceived levels of fear increase when individuals feel unable to cope with external threats (Hale 1996). Due to physiological differences, women and older adults may perceive themselves as less capable of handling danger, thus feeling more vulnerable and insecure (León et al. 2022; Wu et al. 2019). Further research indicates that males tend to feel safer due to social media engagement, while females experience the opposite effect (Kong et al. 2023). This may be linked to their motivations for using social media; men often use it for gaming and making new social connections, whereas women use it more for maintaining established close relationships (Manago et al. 2023; Muscanell and Guadagno 2012), making men’s social support more susceptible to social media influence. Furthermore, the impact of social media on beliefs can affect safety perceptions. Trust in men’s social media competence was found to influence general trust in members more significantly than women’s (Sun et al. 2018), suggesting gender differences in the impact of social media on general trust. Compared to women, men with higher beliefs in a just world tend to exhibit lower tendencies toward aggressive behavior (Sang et al. 2023). Thus, gender moderate the effects social support, general trust, and personal belief in a just world.

Research gaps

Although cultivation theory suggests that social media engagement shapes and influences individuals’ perceptions and beliefs (Morgan and Shanahan 2010), this process has not been explored in depth. Previous researches have focus on the aspects related to fear of public space (Almanza Avendaño et al. 2022), fear of crime (Custers et al. 2017), cyberbullying (Rasheed et al. 2020). However, the impact of the online world on real-life safety has not been thoroughly explored. Addressing this issue is crucial for understanding the mechanisms through which social media affects real-life perceptions of safety and for developing strategies to enhance these perceptions. Additionally, women generally report feeling less safe compared to men (León et al. 2022). Given the distinct motivations that men and women have for using social media, there may also be gender differences in how social media influences perceptions of safety. Clarifying these differences can help in tailoring strategies to enhance safety perceptions for both genders. Therefore, an in-depth exploration of the mechanisms and gender differences in the impact of social media on safety perceptions is necessary.

Network analysis is extensively employed in psychiatric research and has recently been increasingly integrated with structural equation modeling to clarify complex relationships within models (Liu et al. 2018). Network analysis consists of edges and nodes, where edges represent relationships between variables and nodes are evaluated using centrality indices, including strength, closeness, and betweenness (Hevey 2018). Strength indicates the tendency of a node to occupy a central position within the network, representing the cumulative sum of weighted interconnections between nodes. Closeness is the inverse of the cumulative sum of the shortest paths connecting nodes, while betweenness measures the frequency with which a node appears on the shortest route between other nodes (Cai et al. 2020). The stability of a network node is expressed by the correlation stability (CS) coefficient, with stability considered robust when the CS coefficient exceeds 0.5 (Epskamp et al. 2018).

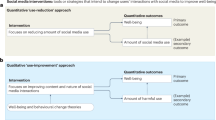

The current study

Individuals’ assessment of environmental safety significantly shapes behavioral responses and interpersonal interactions. Traditionally, evaluations of societal security were based on personal experiences and direct interactions. However, in the digital era, social media has revolutionized access to information, particularly regarding incidents of violence and crime. The portrayal of such events in the media influences how individuals perceive overall societal safety. To elucidate these issues, this study employs network analysis and structural equation modeling to investigate the roles of social media engagement and safety perceptions from both macro (personal belief in a just world) and micro perspectives (general trust and perceived social support), analyzing the key factors that shape safety perceptions. Furthermore, this study examines the influence of gender on these processes through multi-group comparisons. Consequently, we propose five research hypotheses (see Fig. 1):

Hypothesis 1: Social media engagement negatively predicted with an individual’s safety perceptions.

Hypothesis 2: Perceived social support serves as a mediating factor in the relationship between social media engagement and safety perceptions.

Hypothesis 3: General trust plays a mediating role in the relationship between social media engagement and safety perceptions.

Hypothesis 4: Personal belief in a just world serve as a mediating role in social media engagement and safety perceptions.

Hypothesis 5: Gender moderates the impact of social media engagement in indirectly influencing safety perceptions through perceived social support, general trust, and personal belief in a just world.

Method

Participants

The study recruited 1481 participants using a Chinese online platform (https:// www.wjx.cn/), and the entire study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Fujian Normal University. For data preprocessing, the data of participants who did not consent to participation in the study (94 respondents), were aged under 18 years (18 respondents), or exhibited undue promptness were excluded (21 respondents). Ultimately, a total of 1348 valid participates (91%) were obtained, including 938 females (Mean age = 19.40, SD = 1.23).

Measures

Perceived social support (PSS)

Perceived social support scale was developed by Zimet et al. (1988) to assess an individual’s perceived levels of social support. The reliability of the scale has been validated in previous studies (Xiang et al. 2020). It comprises three dimensions: family, friends, and others, each dimension contains four items. Examples include “I can talk about my problems with my family” for the family dimension, “I have friends with whom I can share my joys and sorrows” for friends, “There is a special person in my life who cares about my feelings” for social support from others. Participants are required to rate 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree) on 12 items. Higher scores indicate greater perceived social support. The Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.97.

Social media engagement (SME)

The Chinese version of the social media engagement scale (SMES-A) was used as a tool to measure individuals’ perspectives regarding their use of social media (Ni et al. 2020). This scale comprises ten items, encompassing cognitive, affective, and behavioral aspects. The affective and cognitive domains each encompass three items, illustrated by statements like “Compared to the real world, social media makes me feel more comfortable” for the affective domain and “The support and encouragement of others on social media is very important to me.” for the cognitive domain. The behavioral facet comprises four items, exemplified by the statement “I browse social media whenever I have time.” Participants are required to evaluate each item on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 = “strongly disagree” and 5 = “strongly agree”. Higher scores indicate higher levels of social media engagement. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90 in this study.

General trust (GT)

The General Trust Scale serves as a valuable tool for evaluating individuals’ overall trust levels, as proposed by Yamagishi and Yamagishi (1994). The Chinese version of this scale has been validated in prior research (Shao et al. 2019). This scale encompasses six items, including statements such as “Most people are basically good-natured and kind”. Each item requires participants to score on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree” and 5 = “strongly agree”). Higher scores indicate higher levels of general trust. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95.

Personal belief in a just world (PBJW)

Personal belief in a just world was measured using Belief in a Just World scale developed by Dalbert (1999), and the Chinese version of the scale has been validated by previous studies (Jiang et al. 2016). Participants are required to rate 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree) on seven items (e.g., “I believe that most of the things that happen in my life are fair.”). Higher scores indicate stronger personal belief in a just world. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.96.

Safety perceptions (SP)

Safety perceptions measure an individual’s feelings of safety while walking alone during the daytime and at night (Rountree and Land 1996). It comprises two items: “How safe do you feel walking alone in night time?” and “How safe do you feel walking alone in day time?”. Participants were required to perform a Likert 5-point scale (1= not saft at all, 5 = very safe). Higher scores indicate higher levels of safety perceptions, and the Chinese version of the scale has been validated in previous studies (Zhong 2010).

Statistical analysis

The study employed R version 4.2.2 for data analysis, utilizing the bruceR package for descriptive statistics and correlation analysis. Subsequently, the lavaan package was applied for assessing common method bias, structural equation modeling, and multi-group comparisons. To examine the network structure of participants and identify key nodes, JASP 0.18.3.0 was used, while the NetworkComparisonTest package in R facilitated network comparisons between genders (Van Borkulo et al. 2023). The EBICglasso algorithm is crucial for eliminating spurious correlations in the network (Chen and Chen 2008). Items with factor loadings below 0.6 were removed. The model fit was considered to be in the acceptable range when the comparative fit indices (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) were >0.9 and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was <0.08 (Martynova et al. 2018).

Common method bias

As the study required participants to complete multiple questionnaires, the potential for homoscedastic bias emerged. Consequently, the research employed a common method bias analysis, specifically the Harman single-factor CFA test (Podsakoff et al., 2012). This analysis involved fitting all variables onto a single factor. The results of this analysis indicated that the fitness of single-factor model was poor (χ² = 18318.23, df = 594, χ²/df = 30.84, CFI = 0.63, TLI = 0.61, RMSEA = 0.15), indicating that common method bias had little effect on the results of the study.

Result

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Table 1 presents the results of descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlation analysis for all variables. The results demonstrated a significant positive correlation between SME and all variables, and SP was significantly positively correlated with PSS, GT, and PBJW, respectively.

Structural equation modeling analysis

The study employed confirmatory factor analysis to test the measurement model. Explicit variables corresponded to the items associated with each factor, while latent variables represented the scales used in the study. The results showed good fitness (χ²/df = 4.16, χ² = 2356.10, df = 566, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.96).

The mediating effects of perceived social support, general trust and personal belief in a just world

After controlling for age, education and subjective socioeconomic status, the study employed maximum likelihood estimation to assess model fit, yielding satisfactory results (χ²/df = 6.57, χ² = 4370.82, df = 665, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.91). The result revealed a non-significant relationship between SME and SP (β = −0.02, p = 0.718). Moreover, SME positively predicted PSS (β = 0.47, p < 0.001), GTS (β = 0.52, p < 0.001), and PBJW (β = 0.47, p < 0.001). PSS was positively predicted SP (β = 0.17, p < 0.001), GT positively predicted SP (β = 0.08, p = 0.039), and PBJW positively predicted SP (β = 0.22, p < 0.001). The mediating effect values were 0.08 (95% CI = [0.067,0.170], p < 0.001) for PSS, 0.04 (95% CI = [0.003,0.113], p = 0.040) for GT, and 0.10 (95% CI = [0.101,0.208], p < 0.001) for PBJW. The results suggesting that PSS, GT, and PBJW fully mediate the relationship between SME and SP (see Table 2). Consequently, Hypotheses 2–4 were substantiated.

Multigroup comparison

Additionally, to test whether there are differences in the processes by which SME indirectly influences SP via PSS, GT, and PBJW across genders, the study conducted cross-gender measurement invariant analyses, including construct invariance, metric invariance, and scalar invariance. Construct invariance, which tests for equivalent measurement structures across genders, showed a satisfactory model fit (χ²/df = 2.98, χ² = 3376.55, df = 1132, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.95). Metric invariance, which constrains factor loadings to be the equal between groups, and showed favorable model fit (χ²/df = 2.92, χ² = 3391.94, df = 1163, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.95). Scalar invariance, which constrains both factor loadings and intercepts to be the equal across groups, was similarly within acceptable limits (χ²/df = 2.84, χ² = 3391.94, df = 1194, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.95). Comparisons across models showed no significant differences according to likelihood ratio tests (p > 0.05), and ΔRMSEA, ΔCFI, and ΔTLI values were all less than 0.01, suggesting that measurement invariance was achieved across genders.

In addition, after establishing measurement invariance, the study constructed both constrained and unconstrained models. The constrained model imposes restrictions on all structural coefficient, while the unconstrained model restricts only the factor loadings, allowing all other parameters can be estimated freely. The results showed that the constrained model fit well (χ²/df = 4.05, χ² = 5595.22, df = 1380, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.91), and the free estimation model fit well (χ²/df = 4.08, χ² = 5557. 24, df = 1361, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.91), but the χ² likelihood ratio test was significant for both models (Δχ² = 37.98, Δdf = 19, p = 0.006), indicating that gender had a significant moderating effect on model structure. Stepwise constraints and releases for each pathway ultimately revealed that no gender differences were found only in the two pathways between social media engagement and personal belief in a just world regarding safety perceptions (p > 0.05). It is noteworthy that gender influenced the research paths differently. Specifically, the effects of total SME on SP varied between males and females. Males showed an effect primarily through the indirect paths of PSS and PBJW, whereas females also demonstrated an effect through the indirect path of GT. In addition, the predictive effects of PSS, GT, and PBJW, as well as the predictive effect of PSS on SP, were stronger for males compared to females (see Fig. 2).

Network analysis

Network analysis was performed for all variables by dimension across genders, as shown in Fig. 3. There are 9 nodes for both males and females, 26 non-zero edges for males and 27 for females. For males, the network structure revealed the strongest edge connections for SME2 and SME3 (0.56), while for females, it was PSS2 and PSS3 (0.60). In addition, SME2 and SME3 negatively correlated with PSS1 among males (−0.05, −0.03), and SME3 was also negatively correlated with PBJW and SP (−0.06, −0.10). Among females, SME3 was negatively correlated with PSS3, PBJW, and SP among females (−0.08, −0.02, −0.05), and SME1 was also negatively correlated with GT (−0.02). Regarding SP, the strongest connection was between PSS1 and SP for males (0.22), with no comparable connection observed for GT. In contrast, for females, the connection between PBJW and SP exhibited a greater weight (0.13). As shown in Fig. 4, the centrality test reveals that for females, PSS3 is the most central node with the highest strength (1.44). The correlation stability (CS) coefficients for the centrality indicators showed better stability for strength, with coefficients of 0.67 for males and 0.75 for females. In addition, a Network Comparison Test (NCT) was conducted to evaluate differences in network structure between genders. The results revealed significant differences in network structure (M = 0.22, p = 0.002) and overall strength (s = 0.43, p = 0.026). Specifically, the overall strength of the male network (global strength = 4.37) was significantly higher than that of the female network (global strength = 3.94).

a EBICglasso network structure for males and b EBICglasso network structure for females. PSS1 perceived social support from the family, PSS2 perceived social support from the friends, PSS3 perceived social support from the others, SP safety perceptions, SME1 social media behavioral engagement, SME2 social media cognitive engagement, SME3 social media emotional engagement, PBJW personal belief in a just world, GT general trust.

PSS1 perceived social support from the family, PSS2 perceived social support from the friends, PSS3 perceived social support from the others, SP safety perceptions, SME1 social media behavioral engagement, SME2 social media cognitive engagement, SME3 social media emotional engagement, PBJW personal belief in a just world, GT general trust.

Discussion

This study examines the relationship between social media engagement and safety perceptions, focusing on its underlying mechanisms. The findings reveal that social media engagement significantly increased safety perceptions, but this process is fully mediated by perceived social support, general trust, and personal belief in a just world. Notably, the study also found that the impact of social media engagement on the mediating variables is more pronounced among males, although general trust does not significantly influence their sense of safety.

The relationship of social media engagement and perceived social support

This contrasts with prior research indicating that consumption of social news through traditional media, such as television and the internet, is associated with higher levels of fear of crime (Wu et al. 2019), and that exposure to social media such as WeChat heightens generalized fear and decreases perceptions of safety (Zeng and Wong 2023). This effect is particularly pronounced when individuals encounter portrayals of suicides on social media, which can exacerbate anxiety and suicidal tendencies (Ueda et al. 2017). Nonetheless, the findings of this study demonstrate that social media engagement can enhance perceived safety, with this effect being mediated exclusively through perceived social support, general trust, and personal belief in a just world. Social media facilitates the establishment of social relationships, which are fundamental to human needs for belonging and security (Houghton et al. 2020). Notably, while general social media use did not influence risk perception, selective exposure to social media increased perceived risk, with higher media source credibility correlating with reduced perceived risk (Niu et al. 2022).

The way people evaluate safety

The findings indicate that social media engagement enhances social support and indirectly increases perceptions of safety, which is consistent with previous research. Interactive communication on social media not only bolster individuals’ ability to maintain relationships but also elevate their sense of belonging and identity (Van Bavel et al. 2024), thereby enhancing social support (Häusser et al. 2023; Penfold and Ogden 2023). While problematic social media use weakens social support (Lin et al. 2021). In addition, social support is associated with improved physical and mental health in individuals under 60 (Park et al. 2023), potentially providing additional resources for addressing external threats and challenges. Beliefs about social support not only promote self-efficacy and increase an individual’s ability to cope with danger (Luo et al. 2023), but is also associated with more positive coping styles and lower threat assessments (Cho et al. 2023). Consequently, social media engagement can indirectly enhance safety perceptions through social support.

Research indicates that social media engagement enhances general trust, aligning with prior findings (Sun et al. 2023). Social networks not only provide individuals with support and resources but also foster trust (Fulkerson and Thompson 2008; Lin et al. 2021). This may be attributed to social media’s capacity to offer users greater control over accessing detailed information about relevant events, thereby enhancing general trust (Seo et al. 2012). Higher levels of general trust are associated with better physical and mental health (Lin et al. 2021; Sato et al. 2018), and lower perceived risk (Siegrist et al. 2021). Trust Transfer Theory suggests that trust in a specific object can be transferred from a known target to an unknown one (Stewart 2003). Similarly, research has demonstrated a reciprocal relationship between general trust and political trust (Bargsted et al. 2023), where trust in political institutions enhances individuals’ safety perceptions (Spadaro et al. 2020). Moreover, social media engagement and online discussions can reduce perceived risk by enhancing social trust (Liu and Yang 2021). Consequently, social media engagement can indirectly increase safety perceptions by promoting general trust.

Individuals inherently believe that wrongdoers should face consequences, and events that contradict this belief foster perceptions of an unjust world (Dalbert 1999). Research suggests that frequent social media use can bolster an individual’s beliefs in a just world, especially when strong relationships are cultivated through these platforms (Shin and Hampton 2023). Victims vocalizing their experiences on social media can enhance perceptions of justice by ensuring criminals receive due punishment (Malik et al. 2022). Similarly, political institutions use social media to publicize and punish violations of the social norms (Lee and Wei 2021), reinforcing beliefs in a just world. Such beliefs provide individuals to a sense of control and predictability in life (Lerner 1980), thereby increasing their confidence in facing difficulties. Higher personal belief in a just world enhances well-being and alleviates depressive symptoms (Jiang et al. 2016), while lower personal belief in a just world associates with low levels of perceived control (Fischer and Holz, 2010). In addition, those with higher personal belief in a just world tend to perceive lower levels of discrimination (Choma et al. 2012), lower perceived risk (Dalbert and Donat 2015), and a safer external environment compared to those with weaker beliefs (Ma et al. 2022). Thus, social media can indirectly increase an individual’s safety perceptions by elevating personal belief in a just world.

The difference on safety perceptions between genders

Furthermore, the study revealed that males perceived higher levels of social support, general trust, and personal belief in a just world in their social media engagement compared to females, though their general trust did not influence perceived safety. This disparity may be related to the differing motivations for social media use between genders. Males are inclined to build new relationships, form friendships, and engage in online gaming, while females tend to focus on maintaining existing close relationships (Manago et al. 2023; Muscanell and Guadagno 2012). Network analyses confirm that social media engagement enhances male’s familial connections, with this family support bolstering their safety perceptions. Consequently, social support plays a more substantial mediating role in the relationship between social media engagement and safety perceptions for males than for females.

Moreover, male’s trust in social media’s competence impacts general trust more profoundly than female’s (Sun et al. 2018), explaining the stronger prediction of general trust through social media for males. This aligns with network analysis findings that show a positive correlation between cognitive engagement in social media and males’ general trust. This divergence may root in evolutionary roles, with females typically managing child-rearing and being more cautious towards external information, while males are more prone to risk-taking and teamwork (Geary 2021), making trust in social media competence more valuable to them. However, general trust in others does not significantly affect men’s safety perceptions. This possibly due to their greater resilience to frustration compared to women (Wang 2020), and their reliance on self-trust for safety. Notably, men are more likely than women to report incidents of cyberbullying and victimization on social media (Donat et al. 2023), reinforcing their personal belief in a just world. Thus, while social media engagement strongly influences male’s perceived social support, general trust, and personal belief in a just world, but their safety is primarily influenced by social support and personal belief in a just world.

Limitation and future research

Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design was unable to reveal the causal relationship between the variables; future research could adopt a longitudinal approach to reveal more clearly the interactive process between social media engagement and safety perceptions. Second, this study focused on the overall effects of social media engagement on safety perceptions without distinguishing the impacts of different social media platforms; subsequent research could examine the distinct impacts of different social media platforms. Finally, this study did not ensure an equal representation of males and females, potentially leading to measurement errors that could influence the findings. Future studies should consider addressing these limitations to enhance the robustness of the results.

Conclusion

The study explored the influence of social media engagement on safety perceptions, highlighting the fully mediating role of perceived social support, general trust, and personal belief in a just world. Furthermore, there were gender differences in this process. Males’ beliefs being influenced by social media engagement than females’, and their safety perceptions primarily influenced by social support and personal belief in a just world. This research provides a valuable reference for understanding the mechanisms through which social media enhances individuals’ real-life safety perceptions, addressing a gap in the literature regarding the impact of social media on perceived safety. In addition, attention should shift towards how social media affects personal beliefs, rather than focusing solely on outcomes like personal health. Social media platforms should prioritize fostering and maintaining positive social support networks, while spread positive content to bolster users’ trust and belief in a just world, ultimately enhancing their safety perceptions.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysis during the current study are available in the Dataverse repository, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/518TKZ.

References

Allik M, Kearns A (2017) “There goes the fear”: Feelings of safety at home and in the neighborhood: The role of personal, social, and service factors. J Community Psychol 45(4):543–563

Almanza Avendaño AM, Romero-Mendoza M, Gómez San Luis AH (2022) From harassment to disappearance: Young women’s feelings of insecurity in public spaces. PLOS ONE 17(9):e0272933

Alonzo R, Hussain J, Stranges S, Anderson KK (2020) Interplay between social media use, sleep quality, and mental health in youth: A systematic review. Sleep Med Rev 56:101414

Bargsted M, Ortiz C, Cáceres I, Somma NM (2023) Social and political trust in a low trust society. Polit Behav 45(4):1401–1420

Bar‐Tal D, Jacobson D (1998) A psychological perspective on security. Appl Psychol 47(1):59–71

Cai Y, Dong S, Yuan S, Hu CP (2020) Network analysis and its applications in psychology. Adv Psychol Sci 28(1):178–190

Chen J, Chen Z (2008) Extended Bayesian information criteria for model selection with large model spaces. Biometrika 95(3):759–771

Cho H, Li P, Ngien A, Tan MG, Chen A, Nekmat E (2023) The bright and dark sides of social media use during COVID-19 lockdown: Contrasting social media effects through social liability vs. social support. Comput Hum Behav 146:107795

Choma B, Hafer C, Crosby F, Foster M (2012) Perceptions of personal sex discrimination: The role of belief in a just world and situational ambiguity. J Soc Psychol 152(5):568–585

Custers K, Dorrance Hall E, Bushnell Smith S, McNallie J (2017) The indirect association between television exposure and self-protective behavior as a result of worry about crime: The moderating role of gender. Mass Commun Soc 20(5):637–662

Dalbert C (1999) The world is more just for me than generally: About the personal belief in a just world scale’s validity. Soc Justice Res 12(2):79–98

Dalbert C, Donat M (2015) Belief in a Just World. In: Wright JD (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2rd edn. Elsevier, p. 487–492

Donat M, Willisch A, Wolgast A (2023) Cyber-bullying among university students: Concurrent relations to belief in a just world and to empathy. Curr Psychol 42(10):7883–7896

Epskamp S, Borsboom D, Fried EI (2018) Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behav Res Methods 50(1):195–212

Fay N, Walker B, Kashima Y, Perfors A (2021) Socially situated transmission: The bias to transmit negative information is moderated by the social context. Cogn Sci 45(9):e13033

Fischer AR, Holz KB (2010) Testing a model of women’s personal sense of justice, control, well-being, and distress in the context of sexist discrimination. Psychol Women Q 34(3):297–310

Foster S, Giles-Corti B (2008) The built environment, neighborhood crime and constrained physical activity: An exploration of inconsistent findings. Prevent Med 47(3):241–251

Fulkerson GM, Thompson GH (2008) The evolution of a contested concept: A meta-analysis of social capital definitions and trends (1988–2006). Sociol Inq 78(4):536–557

Geary DC (2021) Male, female: The evolution of human sex differences, 3rd ed (pp. xvii, 645). American Psychological Association

Gunitsky S (2015) Corrupting the cyber-commons: Social media as a tool of autocratic stability. Perspect Polit 13(1):42–54

Hale C (1996) Fear of crime: A review of the literature. Int Rev Victimol 4(2):79–150

Häusser J, Abdel Hadi S, Reichelt C, Mojzisch A (2023) The reciprocal relationship between social identification and social support over time: A four-wave longitudinal study. Br J Soc Psychol 62(1):456–466

He L, Lai K, Lin Z, Ma Z (2018) Media exposure and general trust as predictors of post-traumatic stress disorder: Ten years after the 5.12 Wenchuan earthquake in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(11):2386

Hevey D (2018) Network analysis: A brief overview and tutorial. Health Psychol Behav Med 6(1):301–328

Houghton D, Pressey A, Istanbulluoglu D (2020) Who needs social networking? An empirical enquiry into the capability of Facebook to meet human needs and satisfaction with life. Comput Hum Behav 104:106153

Intravia J, Wolff KT, Paez R, Gibbs BR (2017) Investigating the relationship between social media consumption and fear of crime: A partial analysis of mostly young adults. Comput Hum Behav 77:158–168

Jankowiak B, Jaskulska S, Sanz-Barbero B, Ayala A, Pyżalski J, Bowes N, De Claire K, Neves S, Topa J, Rodríguez-Blázquez C, Davó-Blanes M, Rosati N, Cinque M, Mocanu V, Ioan B, Chmura-Rutkowska I, Waszyńska K, Vives-Cases C (2020) The role of school social support and school social climate in dating violence victimization prevention among adolescents in Europe. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(23):8935

Jiang F, Yue X, Lu S, Yu G, Zhu F (2016) How belief in a just world benefits mental health: The effects of optimism and gratitude. Soc Indic Res 126(1):411–423

Johansson S, Haandrikman K (2023) Gendered fear of crime in the urban context: A comparative multilevel study of women’s and men’s fear of crime. J Urban Aff 45(7):1238–1264

Kong F, Deng H, Meng S, Ge Y (2023) How does mobile social media use associate with adolescents’ depression? The mediating role of psychological security and its gender difference. Curr Psychol 42(19):16548–16559

Kong LN, Hu P, Yao Y, Zhao QH (2019) Social support as a mediator between depression and quality of life in Chinese community-dwelling older adults with chronic disease. Geriatr Nurs 40(3):252–256

Lee DS, Jiang T, Crocker J, BM Way (2022) Social media use and its link to physical health indicators. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 25(2):87–93

Lee J, Wei AC (2021) #PopVultures Podcast: China cancels Chinese celebs and cracks down on entertainment industry. The Straits Times. https://www.straitstimes.com/life/entertainment/popvultures-podcast-china-cancels-chinese-celebs-and-cracks-down-on-entertainment

León CM, Fikre Butler L, Aizpurua E (2022) Correlates of fear of victimization among college students in Spain: Gender differences and similarities. J Interpers Violence 37(1–2):NP147–NP175

Lerner MJ (1980) The Belief in a Just World. In: The Belief in a Just World. Perspectives in Social Psychology. Springer, Boston, MA, p. 9–30

Lin CY, Imani V, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH (2021) Psychometric properties of the persian generalized trust scale: confirmatory factor analysis and rasch models and relationship with quality of life, happiness, and depression. Int J Ment Health Addict 19(5):1854–1865

Lin CY, Namdar P, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH (2021) Mediated roles of generalized trust and perceived social support in the effects of problematic social media use on mental health: A cross-sectional study. Health Expect 24(1):165–173

Lin YC, Lin CY, Fan CW, Liu CH, Ahorsu DK, Chen DR, Weng HC, Griffiths MD (2022) Changes of Health Outcomes, Healthy Behaviors, Generalized Trust, and Accessibility to Health Promotion Resources in Taiwan Before and During COVID-19 Pandemic: Comparing 2011 and 2021 Taiwan Social Change Survey (TSCS) Cohorts. Psychol Res Behav Manag 15:3379–3389

Lipkusa IM, Dalbert C, Siegler IC (1996) The importance of distinguishing the belief in a just world for self versus for others: Implications for psychological well-being. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 22(7):666–677

Liu H, Jin IH, Zhang Z (2018) Structural equation modeling of social networks: Specification, estimation, and application. Multivar Behav Res 53(5):714–730

Liu Z, Yang JZ (2021) In the wake of scandals: How media use and social trust influence risk perception and vaccination intention among Chinese parents Health Communication 36(10):1188–1199

Luo Z, Zhong S, Zheng S, Li Y, Guan Y, Xu W, Li L, Liu S, Zhou H, Yin X, Wu Y, Liu D, Chen J (2023) Influence of social support on subjective well-being of patients with chronic diseases in China: Chain-mediating effect of self-efficacy and perceived stress. Front Public Health 11:1184711

Ma M, Chen X, Lin Y, Zhang B, Bi Y (2022) How does belief in a just world correlate with conduct problems in adolescents? The intervening roles of security, cognitive reappraisal and gender. Child Youth Serv Rev 137:106432

Malik A, Sinha S, Goel S (2022) Coping with workplace sexual harassment: Social media as an empowered outcome. J Bus Res 150:165–178

Martynova E, West SG, Liu Y (2018) Review of principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Struct Equ Modeling: A Multidiscip J 25(2):325–329

Manago AM, Walsh AS, Barsigian LL (2023) The contributions of gender identification and gender ideologies to the purposes of social media use in adolescence. Front Psychol 13:1011951

Morgan M, Shanahan J (2010) The state of cultivation. J Broadcasting Electron Media 54(2):337–355

Muscanell NL, Guadagno RE (2012) Make new friends or keep the old: Gender and personality differences in social networking use. Comput Hum Behav 28(1):107–112

Naderer B, Rieger D, Schwertberger U (2024) An online world of bias. The mediating role of cognitive biases on extremist attitudes. Communications 49(1):51–73

Ni X, Shao X, Geng Y, Qu R, Niu G, Wang Y (2020) Development of the social media engagement scale for adolescents. Front Psychol 11:701

Niu C, Jiang Z, Liu H, Yang K, Song X, Li Z (2022) The influence of media consumption on public risk perception: a meta-analysis. J Risk Res 25(1):21–47

Pan X, Luo Y (2022) Exploring the multidimensional relationships between social media support, social confidence, perceived media credibility and life attitude during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Psychol 41(6):3388–3400

Park LG, Meyer OL, Dougan MM, Golden B, Ta K, Nam B, Tsoh JY, Tzuang M, Park VMT (2023) Social Support and Technology Use and Their Association With Mental and Physical Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic Among Asian Americans: The COMPASS Cross-sectional Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill 9(1):e35748

Penfold KL, Ogden J (2023) The role of social support and belonging in predicting recovery from problem gambling. J Gambl Stud 40(2):775–792

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP (2012) Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It. Annu Rev Psychol 63(1):539–569

Putnam RD (2000) Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital. In: Crothers L, Lockhart C (eds) Culture and Politics. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, p 223–234

Rasheed MI, Malik MJ, Pitafi AH, Iqbal J, Anser MK, Abbas M (2020) Usage of social media, student engagement, and creativity: The role of knowledge sharing behavior and cyberbullying. Computers Educ 159:104002

Rountree PW, Land KC (1996) Perceived risk versus fear of crime: Empirical evidence of conceptually distinct reactions in survey Data. Soc Forces 74(4):1353

Sang Q, Kang Q, Zhang K, Shu S, Quan L (2023) The effect of just-world beliefs on cyberaggression: A moderated mediation model. Behav Sci 13(6):500

Sato Y, Aida J, Tsuboya T, Shirai K, Koyama S, Matsuyama Y, Kondo K, Osaka K (2018) Generalized and particularized trust for health between urban and rural residents in Japan: A cohort study from the JAGES project. Soc Sci Med 202:43–53

Seo M, Sun S, Merolla AJ, Zhang S (2012) Willingness to help following the Sichuan Earthquake. Commun Res 39(1):3–25

Shao J, Du W, Lin T, Li X, Li J, Lei H (2019) Credulity rather than general trust may increase vulnerability to fraud in older adults: a moderated mediation model. J Elder Abus Negl 31(2):146–162

Shin I, Hampton KN (2023) New media use and the belief in a just world: Awareness of life events and the perception of fairness for self and injustice for others. Inf, Commun Soc 26(2):388–404

Siegrist M, Luchsinger L, Bearth A (2021) The impact of trust and risk perception on the acceptance of measures to reduce COVID‐19 cases. Risk Anal 41(5):787–800

Singer AJ, Chouhy C, Lehmann PS, Walzak JN, Gertz M, Biglin S (2019) Victimization, fear of crime, and trust in criminal justice institutions: A cross-national analysis. Crime Delinquency 65(6):822–844

Spadaro G, Gangl K, Van Prooijen JW, Van Lange PAM, Mosso CO (2020) Enhancing feelings of security: How institutional trust promotes interpersonal trust. PLOS ONE 15(9):e0237934

Stewart KJ (2003) Trust transfer on the world wide web. Organ Sci 14(1):5–17

Sun M, Meng X, Hu W(2023) Comparing the effects of traditional media and social media use on general trust in China During the COVID-19 Pandemic Int J Commun 17:1935–1955

Sun Y, Zhang Y, Shen XL, Wang N, Zhang X, Wu Y (2018) Understanding the trust building mechanisms in social media: Regulatory effectiveness, trust transfer, and gender difference. Aslib J Inf Manag 70(5):498–517

Tandogan O, Ilhan BS (2016) Fear of crime in public spaces: From the view of women living in cities. Procedia Eng 161:2011–2018

The 53rd statistical report on China’s internet development. (2024) China internet network information centre. https://www.cnnic.cn/n4/2024/0322/c88-10964.html

Ueda M, Mori K, Matsubayashi T, Sawada Y (2017) Tweeting celebrity suicides: Users’ reaction to prominent suicide deaths on Twitter and subsequent increases in actual suicides. Social. Sci Med 189:158–166

Valente R, Crescenzi-Lanna L (2022) Feeling unsafe as a source of psychological distress in early adolescence. Soc Sci Med 293:114643

Valente R, Vacchiano M (2021) Determinants of the Fear of Crime in Argentina and Brazil: A cross-country comparison of non-criminal and environmental factors affecting feelings of insecurity. Soc Indic Res 154(3):1077–1096

Van Bavel JJ, Robertson CE, Del Rosario K, Rasmussen J, Rathje S (2024) Social media and morality. Annu Rev Psychol 75(1):311–340

Van Borkulo CD, Van Bork R, Boschloo L, Kossakowski JJ, Tio P, Schoevers RA, Borsboom D, Waldorp LJ (2023) Comparing network structures on three aspects: A permutation test. Psychol Methods 28(6):1273–1285

Van Lange PAM (2015) Generalized trust: Four lessons from genetics and culture. Curr Directions Psychol Sci 24(1):71–76

Wang X (2020) The frustration tolerance, self-efficacy and mental health of college students. Adv Psychol 10(02):101–108

Wu Y, Li F, Triplett RA, Sun IY (2019) Media consumption and fear of crime in a large Chinese city. Soc Sci Q 100(6):2337–2350

Xiang G, Teng Z, Li Q, Chen H, Guo C (2020) The influence of perceived social support on hope: A longitudinal study of older-aged adolescents in China. Child Youth Serv Rev 119:105616

Yamagishi T, Yamagishi M (1994) Trust and commitment in the United States and Japan. Motiv Emot 18(2):129–166

Yang C, Tsai JY, Pan S (2020) Discrimination and Well-Being Among Asians/Asian Americans During COVID-19: The Role of Social Media. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 23(12):865–870

Ye B, Lei X, Yang J, Byrne PJ, Jiang X, Liu M, Wang X (2021) Family cohesion and social adjustment of chinese university students: The mediating effects of sense of security and personal relationships. Curr Psychol 40(4):1872–1883

Yue Z, Zhang R, Xiao J (2023) Social media use, perceived social support, and well-being: Evidence from two waves of surveys peri- and post-COVID-19 lockdown. J Soc Personal Relatsh 41(5):1279–1297

Zeng Y, Wong SH (2023) Social media, fear, and support for state surveillance: The case of China’s social credit system. China Inf 37(1):51–74

Zhang K, Kim K, Silverstein NM, Song Q, Burr JA (2021) Social media communication and loneliness among older adults: The mediating roles of social support and social contact. Gerontologist 61(6):888–896

Zhang Z, Zhang J, Zhu T (2013) Relationship between internet use and general belief in a just world among Chinese retirees. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 16(7):553–558

Zhong LY (2010) Bystander intervention and fear of crime: evidence from two Chinese communities. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 54(2):250–263

Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK (1988) The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Personal Assess 52(1):30–41

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and project management: SZ, YC, Conducted data analysis and organization: QG, HY, Writing—original draft: QG, HY, Writing—review & editing: SZ, QG, HY, YC.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethics committee approval dated 10.03.2021 and numbered 20210310 was obtained from the Ethical Committee of Fujian Normal University. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

The study was conducted on May 4, 2023, with informed consent obtained from all participants before they completed the formal questionnaire. They were apprised of the study’s objectives, the confidentiality of their responses, and that the data collected would be used solely for academic research. Furthermore, it was made clear that any personal information would be presented anonymously, and that they retained the right to withdraw from the study at any point. Participants clicked on the “Agree” button to complete the informed consent process.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, S., Guan, Q., Yang, H. et al. Navigating the social media landscape: unraveling the intricacies of safety perceptions. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1420 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03836-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03836-2

This article is cited by

-

Assessing urban renewal efficiency via multi-source data and DID-based comparison between historical districts

npj Heritage Science (2025)