Abstract

The label “Sentinelese” was etymologically derived from the island’s name by the researchers, administrators, and persons who had briefly contacted them, and not the tribes themselves. The conundrum is that their language, customary laws, traditional knowledge systems, and other social practices are still unknown. They are the most well-built and reclusive band of people with no affinity to neighboring tribes of the same archipelago. From prior contacts, it is evident that they still rely on Stone Age tools like bows, metal arrows, and adzes making them hunter-gatherers of modern times. The populace solely relies on nature for their mundane sustenance and survival. Such intimate relationships and interaction between ecology and social life have shaped a different cultural backdrop among the “Sentinelese” populace. Intriguingly, within such socio-cultural proximities, Jarawas, Onges, and Great Andamanese had developed dissimilar sub-cultures of their own. Time again, researchers and administrators tried to establish contact; herein, some individuals, including the second author, had made amicable contact in goodwill expeditions, but mostly, several other individuals who made contact were faced with unfriendly attitudes. In due course, in post-tsunami expeditions and later various other surveys, a ‘hands-off eyes on’ approach predominated the scene. Following such a suit, the present paper seeks to delve into the complex fabric of the tenable knowledge systems of the “Sentinelese” populace and revisit the various narratives of colonial and post-colonial visits, including that of the second author’s account of the North Sentinel Island.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background and Introduction

The Andaman & Nicobar Islands is a Union Territory of India which constitutes 572 islands, islets, and rocks out of which 38 are habitable islands with a topographical coverage of 8249 sq. km (Reddy, 2007) (See Fig. 1). The islands are home to unique in-bred pygmoid tribes such as the Great Andamanese, the Jarawas, the Onges, and the “Sentinelese” (Dutta, 1978; Venkateswar, 2001). For such tribes, around 86% of the total area is reserved and protected forest area, and 36% of the reserved forest is allocated as tribal reserve by the Andaman & Nicobar administration (Reddy, 2007). Radcliffe-Brown, from 1906–08, conducted the first anthropological fieldwork among Andaman Islanders and divided them into two umbrella groupings, i.e., the Great Andamanese and Onges-Jarawas-Sentinelese Group, due to their affinities in language and material cultures (Dutta, 1978). Some of the groups such as Jangils (Portman, 1899) and sub-groups such as Aka-bea (Abbi and Kumar, 2011) are now extinct due to the spreading of disease and ethnocide (Venkateswar, 2004). Amidst all these hues and cries, a distinct, uncontacted, reclusive, distinct from their neighboring tribal cohorts is residing on the terra incognita North Sentinel Island of the Sentinel Islands. However, the South Sentinel Island is uninhabited and located around 59.6 km away from the North Sentinel Island. This Island is located around 48 nautical miles away from the Port Blair harbor and is less than a two-hour cruise by speed vessel from Wandoor, a famous tourist spot in South Andamans (Justin, 2007) (See Fig. 1). The populace inhabiting the North Island is called “Sentinelese” or “Sentinel Islanders” (Sasikumar, 2023).

The area of 59.67 sq.km of North Sentinel is demarcated as a ‘Tribal Reserve’ under the Protection of Aboriginal Tribes Regulation, 1956 to prevent any interaction of the unauthorized non-tribals with the Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs) for Sentinelese tribe. This act prohibits any direct approach closer than five nautical miles or 9.26 km from both sides (the Sentinelese and the non-tribals trying to visit). However, the Indian Coast Guard constantly monitors the region to prevent poaching, trespassing and other illegal activities. An occasional circumnavigation is also conducted by the team of experts from the Andaman & Nicobar administration to observe from a distance.

The etymology of the name “Sentinelese” comes from their residence on North Sentinel Island, and who used the term “Sentinelese” first is quite controversial. The language they used to communicate among themselves, their customary laws, and their traditional knowledge systems are yet to be known or discovered. The neighboring tribes such as Onges, Jarawas, and Great Andamanese had shed their hostility and are now somewhat partially dependent on the Andaman & Nicobar Administration for daily sustenance. In due course, several studies were conducted on Great Andamanese, Onge, and Jarawa, discussing their state of affairs and possible ethnocide (see Dutta, 1978; Chakraborty, 1990; Pandit, 1990; Venkateswar, 1999; Mukhopadhyay et al., 2008). In the case of contacting “Sentinelese”, a very select few research personnel from the Anthropological Survey of India, Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India (including the second author), and some administrators from Andaman Adim Janjati Vikas Samiti (AAJVS), a registered society for protecting Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs) of the Islands were able to establish amicable contact with them. Pandit (1990) in his monograph on the “Sentinelese” populace noted their sporadic behavioral attitudes towards others. The term others are not in terms of cultural otherness but in terms of outsiders or non-autochthons. They even get angered by seeing the Onge tribes who are closest to them (Cipriani, 1966). It can be noted that the neighboring Onges tribe calls North Sentinel as Chia daaKwokweyeh and refers to the people residing in them as Chanku-ate (Sankar and Pandit, 1994). In this vein, even Maurice Vidal Portman, a renowned stalwart on the natives of Andaman Islands, hypothetically considered “Sentinelese” as an off-shoot of Onge (Justin, 2007). In a similar context, the monograph on the “Sentinelese” people describes them as having sensitivity and being highly cautious of others, which might be attributed to some past unknown experiences of social conflict (Pandit, 1990).

In terms of similarities, genomic studies reveal that the ancestors of the Asian clade migrated from Africa through India, entering Australia around 48,000 years ago (Sasikumar, 2023). Subsequent sub-clades, such as M31, migrated to the Andaman & Nicobar Islands around 37,000 years ago (Palanichamy et al., 2006; Barik et al., 2008), showing genetic affinity with the Burmese populace (Sasikumar, 2023). Barik et al. (2008) showcased that around 24,000 years ago, the tribals of Andaman & Nicobar Islands divided from the mainland, giving rise to a distinct sub-clade M32, which denotes a genetic make-up distinct from other populaces due to a lack of genetic diversity within their small community and reproductive isolation. The “Sentinelese” likely share similar genetic traits with other indigenous populations due to their geographic proximity (Sasikumar, 2019). In terms of dissimilarities, early accounts by E. H. Man (1932) highlighted the distinctive features of the Jarawa, who, in contrast to their neighbors, the Aka-Bea (extinct language group of Great Andamanese [Abbi and Kumar, 2011]), were described as taller, differently proportioned, and possessing a distinct hair morphology. This phenotypic diversity was not limited to appearance but also extended to language, with the inhabitants of North Sentinel Island showing physical and linguistic similarities to the Jarawas, as documented (Portman, 1899). Further investigations into the tribes revealed that the Onges, Jarawas, and the “Sentinelese” could be differentiated not only by their speech but also by their material culture forms and social practices (Portman, 1899; Man, 1932). These sociocultural, phenotypic, and linguistic distinctions were supported by the geographical distribution of populations encountered by the British in 1858. The Onges and the “Sentinelese”, situated to the south, were distinctly separated from the Jarawa, who formed a wedge among the Aka-Bea. The latter group shared a history of perpetual conflict with the Jarawa (Portman, 1899; Sasikumar, 2023). A heavy loss in war might have shifted the power dynamics and resulted in isolation but the unfriendliness observed to date cannot be explained without studying the emic perspectives of the “Sentinelese” populace.

In 2004, the Tsunami had wreaked havoc in the region (Venkateswar, 2007). Despite such adversities, the “Sentinelese” had miraculously survived, as discovered during post-tsunami expeditions as per the accounts of the second author (Justin, 2007). This might be due to their closeness to Mother Nature and their indigenous knowledge system (Brower, 2000; 1998). The foresight and wisdom gained by such a populace are through experience, and such experience is passed down from one generation to the next (Behera and Patel, 2000). This can be associated with traditional knowledge systems and such populaces usually survive in adverse conditions due to their knowledge systems (Srinivasa et al., 2020). However, the assessment of the resources available to them for sustenance is speculative at best.

In contemporary times, the presence of the isolated “Sentinelese” tribe continues to intrigue researchers worldwide. Efforts to establish contact have been thwarted by Survival International and local NGOs, leading the Indian government to abandon such endeavors (Survival International, n.d.). And now such picnic visits to North Sentinel Island are strictly prohibited under the Andaman and Nicobar Islands (Protection of Aboriginal Tribes) Regulation, 1956, with the Indian Coast Guard monitoring a buffer zone to deter outsiders. However, periodic assessments by the personnel of Andaman Adim Janjati Vikas Samiti (AAJVS), Andaman & Nicobar administration are being conducted to ensure the social well-being of the “Sentinelese” people (Sasikumar, 2023).

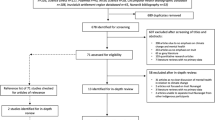

Methodology

The present review article seeks to delve into the lives of the “Sentinelese”, their culture, practices, habits, dislikes, and so on. On-site Malinowskian fieldwork is naturally improbable due to restrictions of the Andaman & Nicobar Protection of Aboriginal Tribes (PAT) Regulation, 1956, and the unpredictable nature of the “Sentinelese”, which also removes the ambit of participant observation. However, in our academic space, numerous reports, articles, conference papers, books, and census data have been compiled, which contain vast repositories of sociocultural data on the populace residing on terra incognita North Sentinel Island. The then-colonial administrators of the British Raj, such as J. Homfray (1867), E.H. Man (1878), M.V. Portman (1880–96), Hobday (1886), G. Rogers (1902), and M.C.C. Bonington (1926) during the early days of penal settlements were also quite curious about the autochthon populace due to their reclusiveness from other neighboring tribal populaces (Sasikumar, 2023). Since then, several expeditions were undertaken in pre-colonial times to establish contact and enable coconut plantations on the North Sentinel Island. But all of them failed due to numerous reasons which M.V. Portman enumerated in his two volumes work (Portman, 1899). In post-colonial times, after the recommendation of the Sundaram Committee (1969), several gift-dropping operations took place (Sasikumar, 2023). The second author was also a part of such gift-dropping operations, and his accounts showcase the shedding of unfriendly attitudes and acceptance of gifts (Sarkar and Pandit, 1994). The operations showcase a transition from dropping to hand-to-hand gifting to the “Sentinelese” populace, which opened a new horizon of delving into the lives of “Sentinelese” (Justin, 2007). It should be noted that several national and international anthropologists, even the famous Claude Levi-Strauss, had asked for permission to work amidst the tribe, but it was rejected by the then Prime Minister of India (Sasikumar, 2023).

Nevertheless, looking at the topic of the populace residing in North Sentinel Island, due to the shift in policy to the “hands off” and “eyes on” approach in the 1990s, the entire idea of study came shattering down (Singh, 2018). The unexplored lives of the “Sentinelese” remained untouched in the heart of the terra incognita archipelago. The populace was also quite reluctant to allow outsiders to land on the beaches due to some unknown reason. The process of ‘study of culture at a distance’ is being approached, but so much has yet to be unearthed. The Andaman Adim Janjati Vikas Samiti (AAJVS), Coast Guard, and Andaman Administration, from time to time, undertake surveys of the archipelago to monitor the headcount of the populace. As of now, no other information has been derived through such form of periodic reconnaissance surveys (Sasikumar, 2023). At present, through this research article, we have tried to decode all the data available on the “Sentinelese” in a brief format to showcase the developments that have materialized in the last four decades. Herein, the second author’s account of contact with the “Sentinelese” serves as a primary data point in this research article, considering the “Sentinelese” being the most hard-to-reach populace. And the rest of the data that is accrued for the article is from re-delving into the already available secondary and tertiary sources of data on the “Sentinelese” populace. The restudy of the “Sentinelese” from a distance is significant in anthropology considering the turn of the 21st century and the changes in modern knowledge systems.

History of North Sentinel Island and its reclusive populace

The uncontacted populace of the North Sentinel Island was initially grouped as Jarawas by colonial administrator M.V. Portman (Pandit, 1990). Portman considered them to be…. “the least civilized perhaps in the world, being nearer to a state of nature than any people” (Portman, 1899). According to Portman (1899), the Andamanese are also classified, irrespective of Tribal divisions, into the “Ar-yauto” or “Coast-dwellers,” and the “Erem-taga” or “Jungle-dwellers” as per Aka-Bea-da language of the Great Andamanese. The North Sentinel tribe are Erem-taga by nature, and Ar-yauto by force of circumstances. Moreover, in Portman’s (1899) writings, he noted that “the North Sentinel Island people are one tribe without sub-divisions, but we know little of them, and they appear to be a recent offshoot from the Onges”. A distinct fact that can be noted in Portman’s contact is that “Sentinelese” was quite docile initially, but after repeated transgressions in the space, things went haywire (Sasikumar, 2023).

Radcliffe-Brown (1948) divided the tribal populace into two groups, i.e., the Great Andaman group and the Little Andaman group. The indigenous people were divided into thirteen divisions, but the Great Andaman groups included all people except Jarawas (Ung) of South Andaman. The Great Andaman group can be sub-classified into the Northern group and Southern group containing Aka-Kede, Aka-Kol, Oko-Juwoi, A-Puchkiwar, Akar-Bale, and Aka-Bea. And the Little group can be sub-classified into Onges (Little Andaman), Jarawas or Ung/Ang (South Andaman), and the populaces of North Sentinel Island (Portman, 1899; Dutta, 1978; Sasikumar, 2023). In the same work, he proposed the theory that the “Sentinelese” may have diverged from the other Andamanese communities, similar to the early inhabitants of Little Andaman (Radcliffe-Brown, 1948). From another perspective, Cipriani (1966) suggests that the “Sentinelese”, originally residing in Little Andaman, were transported to their current location following a cyclone during a fishing expedition at sea. The origins of their presence in Little Andaman are explained by the belief that these nomadic people, ranging from the southern tip of Burma, may have unintentionally drifted to Little Andaman in their outrigger canoes while fishing at sea, subsequently populating the region. Alternatively, Cipriani suggests a migration route through Sumatra and Nicobar Islands before reaching Little Andaman (Sarkar and Pandit, 1994). The genomic studies also showcase their affinity with the Burma populace (Sasikumar, 2023).

In terms of socio-demographics, the Census Report of 1911, for the first time, included the population figures of the “Sentinelese” as a separate group (Pandit, 1990). It was only an estimated figure of 117. The subsequent Census reports continued this trend. But the 1951 Census gives no notes or figures of their population, so the 1913 estimates are just repeated here. The 1961 Census repeats the exact figure of 102–105 with short notes. Pandya (2009) observed that their number might be forty. However, the last 2011 Census showcases an estimated figure of fifty, which is by no means an actual count. Rather, it is a guesswork and the real number might be close to two hundred (Srinivasa et al., 2020; Sasikumar, 2023).

The Era of establishing contact

Under the Andaman & Nicobar Protection of Aboriginal Tribes (PAT) Regulation, 1956, the local administration designated the entire North Sentinel Island as a Tribal Reserve (Sasikumar, 2018). The entire area of 59.67 sq. km with an additional three-mile exclusion zone around the island was established to protect its inhabitants from poachers and other intruders, with regulated air traffic. During an exploration, T.N. Pandit observed 18 huts in the middle of the island, with signs of activity and burning fires (Pandit, 1990). Despite a large contact party with weapons, no aggression was reported, and the “Sentinelese” retreated into the forest upon the party’s arrival, only returning to the shore when the party departed. In 1969, the Sundaram Committee was formed by the Government of India to provide recommendations for the welfare of tribal populations in the Andaman & Nicobar Islands. Following these recommendations, systematic gift-dropping operations were initiated in areas inhabited by the Jarawas and the “Sentinelese” tribes (Sasikumar, 2023). This was considered to be ‘arms-length’ approach wherein the contact team would study their culture and behavior from a distance.

Following such recommendations, several gift-dropping expeditions through contact teams were conducted. Such teams comprised anthropologists, administrators, medical officers, government guests and, on occasion, friends and family of officials (Pandya, 2009) (See Fig. 2). These expeditions are presented in a dated manner (Justin, 2007):

-

On March 28–30, 1970, T.N. Pandit, along with three Onge named Napi Kotai, Kanjo and Tambolay, visited the South, West and East coastal sides of the Island. Around 20 individuals were sighted who threatened to shoot arrows. The team dropped fish, coconuts, bananas, red fabric along with some other gifts. And a stone tablet was erected on a disused kitchen midden to proclaim North Island as part of the Republic of India.

-

On March 28–29, 1974, T.N. Pandit ventured out to the South coastal area. A large number of the “Sentinelese” populace gathered wherein they shot arrows towards the contact team. The team dropped Yorkshire hog, red linen, coconuts, bananas, and plastic buckets. In the same year, during the shooting of a documentary film titled “Man In Search of Man” directed by Prem Vaidya in 1974, shot by a long arrow by the “Sentinelese”, and promptly treated by the doctor on board. The male individual who shot the arrow laughed gleefully and walked towards the shade of a tree, where he sat down on the beach.

-

On October 24, 1981, T.N. Pandit visited the South coastal area. Around 12 individuals were present on the shore. There were no gestures of unfriendliness, and the dropping of usual gifts was allowed.

-

On January 3, 1982, T.N. Pandit visited the South Coastal area. He was unable to count due to the presence of large numbers. There were no signs of unfriendliness, and gifts were dropped.

-

On February 21, 1982, T.N. Pandit visited the South Coastal area. Not a single individual were sighted. But the team dropped the usual gifts on the beach.

-

On March 15, 1982, T.N. Pandit, along with other personnel, visited the South coastal area, and this time, he cruised around the entire Island. There was no trace of the “Sentinelese”. The team dropped the usual gifts on the beach.

-

On November 19, 1982, T.N. Pandit visited the South coastal area and Constance Isle at South Point of the Island. There were around 11 members were present. They shot arrows, and the then Superintendent of Police, P.V. Sinari, got struck with an arrow. Thereafter, they allowed the contact team to place the usual gifts on the beach.

-

On January 6, 1983, T.N. Pandit visited the South Coastal area. Around 32 men, women and children were spotted. They were in agitated moods and were holding bows and arrows. Choppers, sickles, mugs, buckets, and coconuts were dropped.

-

On December 1, 1985, J.K. Sarkar visited the South Coastal area. There were around 24 individuals were present. They were very agitated but did not shoot any arrows at the contact team. They allowed the contact team to place 400 coconuts, 15 kg sweet potatoes and some adzes on the beach as gifts.

-

On December 27, 1985, M.K. Raha, D.C. Bhowmik, and R. Subbakrishna visited the South coastal area. The Lt. Governor T.S. Oberoi accompanied the contact party. There were 26 individuals were spotted wherein there were 13 males, 9 females, and 4 children who belonged to ages 6 to 10. Among the females two were pregnant. There were signs of unfriendliness. And around 400 coconuts were dropped on the beach as gifts.

-

On May 1986, the second author first visited Sentinel Island at two different places in the Southern Coastal area. He sighted around 98 individuals belonging to various age-sex groups. They gleefully accepted gifts (See Fig. 3). The second author planted seedlings of coconut trees between a Creek near Allen Point, and a Sentinelese hut in mid of the south coastal area (See Fig. 4).

-

On February 11, 1987, J.K Sarkar, along with a film crew, ventured out to the South Coastal area and South Point near Constance Isle. The Lt. Governor T.S. Oberoi accompanied the contact party. Around 28 individuals were spotted. Herein they shot arrows at the contact team. Some arrows fell a few inches into the sea away from the lifeboat. The security officer of the then Lt. Governor, Shri T.S. Oberoi fired in the air which scared away all the “Sentinelese”. Around 100 coconuts and a bag full of choppers were dropped as gifts.

-

On May 27–28, 1987, R. Subbakrishna visited the South Coastal area and South Point near Constance Isle. Around 13 individuals were spotted. They threatened to shoot arrows. Around 100 coconuts were dropped on the beach. Along with this, citrus saplings were planted on the beach.

-

On February 9–10, 1988, M.K. Raha visited the West Coastal area. Around 20 individuals including women and children were spotted. They exhibited gestures of friendliness. The team dropped gifts containing rubber balls, bead necklaces, red ribbons, and coconuts.

-

In March 1990, the second author, along with a documentary crew of Shri Kalyan Mukherjee and Smt. Aruna Prasad, visited three different places in Southern Coastal areas to make a film titled “The Last Tribes of A&N Islands”, which was sponsored jointly by the Anthropological Survey of India and the Andaman & Nicobar Administration. Around 72 individuals belonging to various age-groups were spotted. The screening of the movie took place in 1992 at Mueller Bhawan, New Delhi, and Kolkata. The “Sentinelese” were in cheerful moods and they showcased some obscene behavior (showing their phallus), sitting on haunches, etc. They accepted gifts from the contact team. However, a member mistakenly threw a coconut close to women, but none of them was provoked by such an incident.

-

On November 7–8, 1990, the second author, along with two Onge individuals named Bada Raju and Chota Raju, visited the Southern Coastal areas. Around 60 individuals were spotted. They seem to be amenable to friendly contact with outsiders and accepted gifts, as usually seen in earlier expeditions.

-

In January 1991, the second author, along with several other personnel including S.A. Awaradi, visited the Southern Coastal area. Around 43 individuals were spotted. They exhibited cordial behavior and accepted gifts.

-

In February 1991, a contact party visited the North Sentinel Island. A male individual came very close to the contact party to accept gifts and even dared to enter the boat to quench their curiosity. After finishing with the gifts, the lifeboat moved back a little distance into deeper waters, but one member of the team remained among the “Sentinelese”, busy observing the people. This was not initially noticed by the other members of the team. Seeing this, two or three Sentinelese were exchanging words among themselves, and then one of the young men took out his knife and, moving it in a cutting gesture, tried to warn others. One of the male Sentinelese threw a piece of coral at them but did not hurt anyone. Pandit (1990) observed that the display of a knife and throwing the piece of coral could be interpreted as a defensive action and as a warning gesture.

-

On February 12–13, 1993, the second author visited four different places in Southern Coastal areas. Around 95 individuals were spotted. There were no signs of unfriendliness, and they happily accepted gifts from the team.

-

In January 1994, the second author made contact near the Eastern Coastal area. There were 41 individuals were present. There were no signs of unfriendliness, and they had happily accepted a gift from the contact team.

Contributed by Second Author - The second author is delivering coconuts hand to hand to a Sentinelese individual on North Sentinel Island. They accepted the gift gleefully without a sign of unfriendliness. The face of the male Sentinelese individual was censored in the interest of tribes of Andaman & Nicobar Islands, India.

This was another visit to North Sentinel Island during gift-dropping missions which took place in March 1990 wherein the second author is holding a stringless Sentinelese bow. In his earlier visit he had planted seedlings of coconut trees between a Creek near Allen Point, and a Sentinelese hut in mid of the south coastal area.

Thus, through the aforesaid context, it can be deduced that silent barters play a significant role in pacification and establishing friendly contact with the populace (Pandit, 1990; Justin, 2007). Some of that jetsam were picked up and used as precious items of the material culture of the “Sentinelese”. For the period, the ‘arms-length’ approach was successful, and herein instances of gifting can be seen as an adapted form of ‘silent barter,’ characterized by one-sided giving without any reciprocal exchange. The second author observed that large fishing nets (with systematic floatable floats or buoys, either in round shapes, long, or other designs) spread in the shallow lagoon. In addition, jetsam consists of broken planks, doors of ships, plastic bottles, Jerry cans, worn-out shoes, hawai chappals (sandals), used pieces of fabric, etc. In contrast, the “Sentinelese’s” initial unfriendliness can be rationalized through the hypothesis that the foraging community’s hunting and gathering subsistence economy prompts spontaneous, aggressive behavior as a means to protect themselves, their territory, and the available resources. Such a culture is entirely molded by the harsh and isolated environment of the North Sentinel Island, which created a distinct knowledge system known and utilized by them since time immemorial. The aggression exhibited by such hunting-gathering communities stems from an apparent belief that external factors pose a threat to their territory, resources, and overall well-being. And this is quite natural considering their isolation for the past several centuries, solely relying on their traditional knowledge systems (Sasikumar, 2023). Nevertheless, with protests from various corners surmounted the government of the day introduced the “hands off” and “eyes on” approach to protect the Sentinel Islanders (Singh, 2021).

Post-tsunami Expedition to the North Sentinel Island

In 2004, when the Tsunami occurred, the “Sentinelese” possibly observed unusual activity in the sea beyond the shallow waters and breakers along the coast (Justin, 2007). It is plausible that their ability to anticipate such events was rooted in traditional knowledge systems derived from lived experiences, fear, and wisdom passed down orally through generations. These indigenous knowledge systems surely played a crucial role in safeguarding them from the impending catastrophe, showcasing the effectiveness of their traditional practices and wisdom in responding to natural threats. This enabled all the tribal populaces of Andaman & Nicobar Islands to survive despite considering them so-called uncivilized.

After the Tsunami, a search party of the Coast Guard by helicopter visited the Islands and saw the first glimpse of the “Sentinelese” (Justin, 2007; Sasikumar, 2023). This reaffirmed that they had survived such a huge-scale natural disaster. In due course, an expedition team was formed with the second author as the leader to assess the ground-level realities in North Sentinel Island. The phases of the expedition can be divided into (Justin, 2007):

-

In April 2003, the second author visited the Southern coastal area. Around 38 individuals were spotted. There were no signs of unfriendliness, and they had happily accepted all the gifts. An Onge-built canoe was also gifted to the “Sentinelese”.

-

On December 30, 2004, the second author visited the Southern coast at Allen Point at the wreckage of a Panama ship. Around 25 individuals were spotted. They showed gestures of friendliness and cheerfully took gifts.

-

On December 30, 2004, the second author in the same expedition visited the Western coast around 2 km away from Allen Point. Around 5 members of the community were spotted. They showed gestures of friendliness and cheerfully took gifts.

-

On December 30, 2004, the second author in the same expedition visited the Western Coast at the wreckage of a Panama-made vessel named Prime Rose near Snake Isle. Around 2 members of the community were spotted. They showed gestures of friendliness and cheerfully took gifts.

-

On March 9, 2005, the second author visited the Northeast Coast area of the North Sentinel Island. Around 13 individuals were spotted. They were friendly as usual and came to accept gifts in neck-depth seawater to pick up gift articles dropped by the team.

The March 2005 expedition marked the end of gift dropping mission era. To date they are uncontacted, totally having no means of communication in the strictest sense of the term, inhabiting an isolated island. The coterminous region is declared a scheduled protected place. The second author saw the tribes emerging from the littoral forest to the seabeach, since it was low tide or neap tide, they had proceeded to the sea watermark beyond the rocks/reefs. They swam beyond the breakers, which was a bit favorable as not many large waves were there. The sea was calm. The team threw coconuts beside bananas to them. They had cheerfully collected them. One notable thing that the second author had observed was that not all of them crossed the breakers. Quite a few men and women were seen either standing on an elevated portion whereas some were on the edge of the sand. One woman was pregnant, who might be around 03 months pregnant, which is a clear indication of their procreation stamina and health level of conceiving a baby in the womb. This, of course, is not the first time that females were discernibly seen pregnant. Apart from this, it was evident that the Tsunami of 2004 resulted in the emergence of a segment of the earth’s crust in a specific continental shelf zone near the North Sentinel Island. In this context, while the impact of Tsunamis on human lives is generally minimal, the sudden alterations in the topographical features of the North Sentinel Island and potentially other islands in the Archipelago indicated a significant reshaping of the landscape (see Fig. 5). Inopportunely, the “Sentinelese” had experienced the loss of their fishing grounds in the southern coastal area due to these changes, which would substantially impact their fishing activities in that region. However, even after such adversities they have survived only through their reliance on their traditional knowledge systems.

Death of Two Fishermen Trespassing North Sentinel Island (2006)

In January 2006, two fishermen named Sunder Raj and Pundit Tewari went missing near North Sentinel Island (who were both ex-convicts) (Pandya, 2009). News of their deaths, therefore, created a social schism in the Andamans. New settlers felt that the law should be upheld and the ‘murderers’ brought to justice; older settlers remained quiet on the matter. A news report on NDTV showcased the entire event wherein Commandant Praveen Gaur had dug up the dead body, which was strangled using rope from the boat near the beach by using various tactics. But he was unable to recover another body. For this incident, he was awarded the Tatrashak Medal for Gallantry on Independence Day (2006) (Som, 2018). This re-engaged the unfriendly attitude of the tribe against outsiders who were using modern technologies such as helicopters to invade their space (Sasikumar, 2023). The attempts to retrieve the bodies now can be viewed as a blunder that again provoked the unfriendliness attitudes towards outsiders.

Aerial Survey and Circumnavigation of 2014

In the 1990s, the Andaman & Nicobar administration adopted a “hands-off” and “eyes-on” approach toward the “Sentinelese” (Singh, 2021; Sasikumar, 2023). In April 2014, concerns arose due to reports of a wildfire on North Sentinel Island, sparking worries about the safety of the inhabitants. Citing the fishermen’s accounts, reports circulated that the chaddahs (Jarawa term for temporary camps) had no light, referring to the burning torches typically displayed outside the huts of the “Sentinelese” during the night, were not observed during that period (Sasikumar, 2018). An aerial survey conducted by a team from AAJVS, the Anthropological Survey of India, and the Forest Department revealed footpaths suggesting human presence, but no individuals or typical huts were spotted (Sasikumar, 2023). The second author was also one of the team members of the aerial survey mission of 2014 which marked his final expedition to the North Sentinel Island.

On April 18–19 2014, a special team circumnavigated North Sentinel Island aboard the M.V. Shompen to investigate further. Sasikumar (2018) reported sightings of “Sentinelese” individuals, including women and children near Jarawa islet and Constance Isle armed with bows and arrows. On the second trip to the same spot, two individuals with adzes were observed, exhibiting friendly gestures. On the third trip, two women with a child were sitting on a rock, and three men stood in waist-deep water collecting coconuts. They wore shell necklaces and bark belts and had prominent muscles. Despite challenges posed by high waves, interactions varied, with some individuals from the island exhibiting friendly gestures.

The total number of individuals gradually increased to fourteen, with boys using canoes to retrieve coconuts and men equipped with spears in outrigger canoes. During subsequent trips, interactions varied, with some individuals appearing busy but not unfriendly. Approximately sixteen individuals were observed during one trip. A later trip to the northern side of the island did not yield sightings of the islanders. The 2014 circumnavigation suggested a balanced male-female ratio and a notable presence of children among the “Sentinelese” (Sasikumar, 2023).

Chau Incidence (2018)

The death of an evangelist named John Allen Chau on November 17, 2018, brought the “Sentinelese” again into the limelight (Bagchi and Paul, 2020). The said person tried to preach the tenets of Christianity to the “Sentinelese” populace (Sasikumar, 2019). The person bribed local fishermen to gain access to the secluded island. Chau’s 13-page diary contains details of various illegal journeys to gain access to North Sentinel Island (Mandal, 2018). According to the account, the individual, identified as Chau, reported being shot by the “Sentinelese”, specifically by a young person, potentially around 10 years old or a teenager, noticeably shorter than the apparent adults. Remarkably, the arrow hit him directly in the Bible he was holding against his chest (Sharma, 2018). Expressing his thoughts in line with his role as an evangelist, Chau questioned why a young individual had targeted him, emphasizing the lingering memory of the child’s high-pitched voice. Despite the incident, Chau remained undeterred, stating his reluctance to abandon the mission and pass it on to someone else. He also documented observations about the “Sentinelese” language, noting its prevalence of high-pitched sounds like “ba, pa, la, and sa” (Sasikumar, 2019). Additionally, Chau provided an estimate of the island’s population, suggesting around 250 inhabitants, with at least 10 people residing in each hut (Sasikumar, 2018). All of these are very crucial pieces of information that can be garnered as a point of reference for linguistical sub-variations observed in the “Sentinelese”. Nevertheless, both of these incidences showcased that “Sentinelese” are not anthropophagic. Rather, they bury such individuals with proper rites, but they are quite reluctant to share their space with outsiders (Bonington, 1932; Som, 2018; Sasikumar, 2023).

Fishermen Missing Near Sentinel Island (2023)

Three fishermen from the Wandoor Area of South Andaman went on a fishing trip on December 22, 2022 and never returned (Karthick, 2023). Their boat has been spotted on North Sentinel Island by the local fishermen and the A&N administration. A flag-like structure could also be seen near their boat. In this context, the flag might have been the distress signal or the spot where they were buried by the “Sentinelese” tribe after a brief encounter as it remains unsolved. Hypothetically, the crocodiles surrounding the island since time immemorial might also be the reason for unfriendly attitudes towards the outsiders considering them similarly ferocious as crocodiles.

Sentinelese Populace and Their Material Culture

Initially, they were considered to be a docile populace by M.V. Portman during his visit to the North Sentinel Island (Portman, 1899). But there was a quick shift in stance towards outsiders in the due course of time which was also noted by Portman in his journals. The “Sentinelese” share the so-called Negrito physical traits, viz., medium stature, dark complexions, and woolly hair. They are slightly taller than the other three Negrito tribes of the Andamans. Moreover, the populace residing on the North Sentinel Island is linguistically dissimilar because even members of the neighboring tribal populace were unable to understand what they were saying (Justin, 2007). There was an instance of hearing Nariyela Jaba Jaba by M.M. Chattopadhyay, but that was considered to be a hunch as there was no concrete evidence regarding the use of the Jarawa language (Sasikumar, 2023). The diary of Chau contains information that they use high-pitched voices “ba, pa, and la”, but such data is quite insufficient (Sharma, 2018). The food items found in the huts of the “Sentinelese” indicate that the meat of wild boar, sea turtle, different varieties of fish and mollusks, fruits, roots, and tubers are the main food. Occasionally, they get new food items like coconuts and bananas from a team calling at the island in the hope of establishing friendly contact (Sarkar and Pandit, 1994).

The existence of small, impermanent palm-thatched shelters, founded on four wooden posts near the coastline, suggests that the “Sentinelese” move in small groups to hunt and forage, like other tribes of Andaman & Nicobar Islands (Pandit, 1990). The band usually fluctuates from 3 to as many as 18 or more people. An encampment of this particular group with 20 small lean-on type huts, has been discovered around half a kilometer from the coastline, at the interior part of the jungle (See Fig. 5). They essentially forage for food resources in bands but the exact number is unknown to us. These groups have independent fireplaces in a small lean-to which points towards the existence of nuclear or extended forms of families in such small bands. “Sentinelese” as a populace is completely separated and very little data is available on them. The rest of the autochthons such as the Andamanese, Onge, and the Nicobarese or even the non-tribal people think of them as unfriendly tribes who would not be able to adjust to their social coterie (Sarkar and Pandit, 1994).

The structure of social organization and the form of kinship relationships prevailing midst them are still unfamiliar. Among the “Sentinelese”, the social grouping is relatively small and separated into three or four bands on a widespread system of kinship and reciprocity, given the space they are inhabiting and the ecological source accessible to them. In terms of gender division of labor, adult “Sentinelese” females have been found to take affectionate care of the young children whom they carry on their backs. “Sentinelese” women have been seen with small round nets and baskets, which suggests that fishing in shallow waters with such nets is their work. They are also apparently gatherers. In contrast, as the “Sentinelese” men travel around with bows and arrows, it is supposed that hunting and fishing are the tasks of men. Their arrows now mostly have iron heads earlier wooden heads were also discovered. A few areca wood fishing arrows have four-edged pointed harpoon heads and all the arrows are very elongated, approximately 1.5 meters in length (Sarkar and Pandit, 1994). The shaft is made of areca wood. They make bows, arrows, and spears with iron points and heads. These are used for hunting. They also make baskets of various kinds to carry and store food in. Net baskets are also made by them (Sarkar and Pandit, 1994). They also used scrap iron as arrowheads for hunting. The fishing nets used by the “Sentinelese” are quite similar to those of Jarawas and Onges (Pandit, 1990).

The aesthetic illustration of the “Sentinelese” is noted in the plain zig-zag pattern made occasionally on the interior section of the bow, in the making of leaf/bar ornaments and also in cane baskets, in the flame-burnt imprints on the tube of the arrow, and in their basic outrigger canoes. Their canoes are built using carved-out woods and have one beam for balance. The wooden tubes of their weapons have ornamental, geometrical etchings with monochrome colors (fashioned by smoldering the wood). The women have been observed dancing elatedly. This dance was done by slapping both palms and thighs to the beat, in chorus bending the knees. The pace is repetitive along with other signs (Sarkar and Pandit, 1994) which is quite similar to that of Onges (Cipriani, 1966). Moreover, they wear a waist band which consists of two bark sheets sewn together to serve as a belt. This is used to keep arrows which is also similar to that of Jarawa but not of Onge (Pandit, 1990). This signifies a distinct indigenous knowledge system working in the “Sentinelese” tribe due to their closeness to nature which is similar to that of the Onge populace living in the Little Andamans (Mann, 1981). In this context, it can be noted that red cloth pieces were given in various gift-dropping operations (Justin, 2007). The red color is usually liked by other cognate groups such as Onges, Jarawas, and Great Andamanese. But it was discarded by the “Sentinelese” (Sasikumar, 2023). However, after periodic exposure from contact parties, the populace had incorporated red cloth as a form of skirt to cover their pelvic region, as observed during a mission to recover the dead bodies of fishermen in 2006 (Som, 2018). This might be a form of visual acculturation and a gradual shift away from their naked way of living life in their time and space.

In terms of means of support and sustenance, the “Sentinelese” are limited to hunting wild boar, sea turtles, fishing, foraging roots, tubers, honey, and eggs of endemic turtles. This signifies that the primordial stage of hunting and gathering of land and sea-based resources is their only means of subsistence. They depend on the sea resources more than the Jarawas or the Onges for food. They consume a lot of mollusks, this is inferred from the plentiful shells of roasted mollusks dispersed in their encampments, particularly king shells. The sea adjacent to the whole island provides ample fishing grounds. Herein they fish near the coastline using bows, arrows, and spears on board their small outrigger canoes which do not allow them to venture out in the high seas. And after death, “Sentinelese” bury their dead members. Bonington (1932) mentioned that the “Sentinelese” bury their dead infants within their huts, placing Nautilus shells and other smaller shells over the graves. There is no recorded data by any researcher regarding anthropophagic behavior among the “Sentinelese” people (Sasikumar, 2023). In the case of fishermen Incidence (2006) and John Allen Chau (2018), both were buried on the beach, which signifies that they were buried away from the common burial place. This is to signify that they were outsiders, so they would not get buried with other members of the band.

Draft Policy On Sentinelese Tribe

A draft policy was put forward by the Late Prof. Vinay Kumar Srivastava, the then Director of the Anthropological Survey of India, along with other anthropologists, after the Chau incident in 2018 (Srivastava et al., 2020). The policy proposed: firstly, to ensure the legal protection of the territorial sovereignty of North Sentinel Island is imperative. Secondly, it is essential to safeguard its inhabitants from the intrusion of outsiders driven by various motives, including economic interests, tourism, or mere curiosity about unexplored territories. Thirdly, there is a pressing need to accumulate knowledge about North Sentinel Island and its residents gradually. And lastly, it is crucial to acquaint the local population of Andaman & Nicobar Islands with the influx of global tourists and the diverse lifestyles of tribal communities. This awareness should extend to sensitizing individuals to the challenges faced by these tribes and the islands. Collaborative efforts are necessary to foster the principles of responsible tourism, ecological consciousness, and social empathy, and these endeavors should persistently continue. The policy also looked into the alternative for ‘on the spot study’ with ‘study of a culture from a distance’ (Srivastava et al., 2020). It was proposed: firstly, to include additional sources of information from comprehensive interviews with individuals who participated in previous goodwill contact missions, providing insights into their observations during the circumnavigation of Sentinel Island and the significance of these experiences. Secondly, undertaking In-depth discussions with specialized staff involved in working with Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs) will contribute valuable knowledge about the “Sentinelese” gained through their interactions with tribal communities. Thirdly, to undertake conversations with fishermen, especially from Wandoor, Manglutan, Chidiya Tapu, and others, will be sought to gather information on their visits to the island and any encounters with the native population. Fourth, an analytical examination of the journal of an American national who closely observed a group of “Sentinelese” which will offer additional perspectives. And lastly, regular circumnavigation tours around Sentinel Island, conducted by a team of anthropologists well-versed in the ecology and culture of Andaman & Nicobar tribes, will provide patient and detailed observations for subsequent compilation and group discussions.

In due course, several comments were raised by anthropologists who were concerned with the tenets of the Draft Policy on the Great Andamanese and “Sentinelese” (Srivastava et al., 2020). The comments put forward contain comments by K.B. Saxena, V.S. Sahay, S. Roy, and T.N. Pandit (Saxena et al., 2021). Herein, Saxena critically objected to the context of territorial rights considering the impact on “Sentinelese”, which might be caused due to commercial or strategic gain, and also suggested that prolonged contact due to periodic visits might cause the advent of modern-day diseases in the members of the populace; the comment by Sahay suggested the use of periodical monitoring through satellite imagery; another comment by Roy questioned the validity of data which would be collected as an alternative to on-site Malinowskian fieldwork; and in the end, Pandit put forward an elaborate explanation on why “Sentinelese” as an untouched tribe should be left alone in the same manner for the survival of the tribe in the terra incognita North Sentinel Island (Saxena et al., 2021).

Concluding discussion

The tribal populace of the Andaman & Nicobar Islands is close to their ecological niche due to their reliance, which can be seen in the tribes of Shompens, Onges, and Jarawas as part of larger traditional knowledge systems. The Sentinel Islanders equipped with their unique Indigenous knowledge system molded by their ecological niche might be far superior to any other scientific machinery developed through science and technology. The accounts of the second author and numerous other persons who had contacted the “Sentinelese” during gift-dropping operations suggested by the Sundaram Committee (1969) showcased the usage of waistbands by hunters, which is similar to neighboring tribes. A distinct indigenous knowledge system is at play in the “Sentinelese” populace, which yet remains to be explored in the heart of terra incognita North Sentinel Island. The Great Andamanese used to live in communal huts with a central space in the middle for dance and social practices (Radcliffe-Brown, 1922) which slowly disappeared from forced coercion at Andamanese Homes to their present unrestricted stay at Strait Island. The Yanomami people who live several kilometers away in the bordering regions of Venezuela and Brazil also have communal huts near the freshwater streams with a central area to carry out social practices (Milliken et al., 1999; Wallace, 2016). This is truly interesting how such pristine untouched tribes have similar cultural patterns. The Yanomami people are still uncontacted and the “Sentinelese” might have similar communal hut patterns or a different communal hut pattern which is yet to be discovered. The Onges have an undeveloped religious system fortified by animism, which might also be present in the “Sentinelese” (Mann, 1981). At present, contact with mainstream people can cause acculturation which can definitely harm the passage of oral traditions in such populaces due to their possession of different kinds of indigenous knowledge systems from modern knowledge systems. There are various sets of challenges to on-site Malinowskian fieldwork on North Sentinel Island, considering the distance from Port Blair, the weather of the sea, and the unpredictable personality of the “Sentinelese”. Moreover, the untouched populace might be vulnerable to modern-day maladies with lesser resistance to virulent viruses (Srivastava, 1993; Saxena et al., 2021) or even simple cough and cold. The usage of choppers, adzes, harpoons, bows, and arrows by the “Sentinelese” populace creates an ambiance of reminiscence of the bygone Stone Age, considering their thousands of years of isolation from neighboring tribal populaces. The wreckage of ships on the coastline of North Sentinel Island led to the usage of metal tips of arrows (Pandya, 2009). Moreover, a rescue mission in 2006 showcased the presence of hunting strategies and formation among the “Sentinelese” populace (Som, 2018), which they had developed and might be passed down orally due to the absence of any noted script by such tribes. The unintelligible language of the “Sentinelese” is the first social barrier that needs to be addressed to understand and communicate with such populace properly but blunt unfriendliness is the hindrance faced by contact teams. Apart from these, the concept of the Kuvera (traditional medicine man) is found among Onges (Mann, 1981); a similar medicine man might be there among the “Sentinelese” who look into various maladies faced by the populace. All of these are unknown to us due to the change in policy in the Andaman & Nicobar administration to the “hands off” and “eyes on” approach after protests and campaigns by Survival International and other local NGOs against such picnic expeditions for VIPs by breaching numerous protocols for the sake of adventure (Sasikumar, 2023; Survival International, n.d.). Furthermore, all the socio-demographic data present in the Census are just hunch or guesswork, which showcases the dearth of headcount from the coastline, let alone anthropological data on the “Sentinelese” people.

Limitations and recommendations

The question time and again comes up: To Study or not to Study? Or do we leave them alone? Or shall we explore them ethnographically? The correct answer is that anthropological restudy is the need of the hour and it would be pertinent to use modern technology such as satellite imagery, drones, and other techniques to collect data on them. A new schema needs to be chalked out to contact the tribe without disturbing their social settings. Dr. Ambedkar, the chief architect of India’s constitution noted that “…The Aboriginal Tribes have not as yet developed any political sense to make the best use of their political opportunities and they may easily become mere instruments in the hands either of a majority or a minority and thereby disturb the balance without doing any good to themselves” (Ambedkar, 1945). This is especially pertinent considering the “Sentinelese” as a tribal group who are unaware of its surrounding mainstream people and their values. The photographs taken during the gift-dropping expeditions already showcase their material culture and resistance against outsiders. The personality study is often considered redundant but is plausible in the context of such an untouched tribe. The safe bet would be that employing modern technology would enable social researchers to tap into earlier untapped traditional knowledge systems and healthcare practices, which have enabled them to survive in such harsh conditions since time immemorial. A direct physical contact can result in the transmission of various diseases for which they might be unprepared, which can lead to the extinction of the entire “Sentinelese” populace. Ethnocide is observed among the other tribal populaces of Andaman & Nicobar Island, but this small tribe has been successfully protecting their own island from outsiders with the help of their long bows and arrows. This portrayal has labeled them as the most unfriendly tribe in the region. In this context, North Sentinel Island is often seen as the remaining stronghold of a population in the so-called Stone Age, resisting the influence of what is considered civilized culture. In a similar pulse, disturbing such a delicate knowledge system among the “Sentinelese” would cause complete obliteration. To end, leaving them alone in their social setting would only enable their survival in the future times, however, modern technologies can surely aid in studying their social behaviors, cultural patterns, and practices but from a distance.

Data availability

Data used in this study are available from the second author at reasonable request.

References

Abbi A, Kumar P (2011) In search of language contact between Jarawa and Aka-Bea: the language of South Andaman. Acta Orientalia 72:1–40

Ambedkar BR (1945) Communal Deadlock And Ways to Solve It. Bheem Patrika Publications

Bagchi SS, Paul S (2020) Anthropology for all. Deep Prakshani

Barik SS, Sahani R, Prasad BVR, Endicott P, Metspalu M, Sarkar BN, Bhattacharya S, Annapoorna PCH, Sreenath J, Sun D, Sanchez JJ (2008) Detailed mtDNA genotypes permit a reassessment of the settlement population structure of the Andaman Islands. Am J Phys Anthropol 136:19–27

Bonnington MCC (1932) Census of India, 1931: the Andaman and Nicobar Islands Vol II. Government of India Central Publication Branch

Behera DK, Patel S(2000) Resource conservation through religious sanctions and social conservation in a primitive tribal group of Orissa, India. J Soc Sci 4(1):57–64

Brower J (2000) Practices are not without concepts: reflections on the use of indigenous knowledge in artisanal and agricultural projects in India. J Soc Sci 4(1):1–9

Brower J (1998) On indigenous knowledge and development. Curr Anthropol 39(3):351

Chakraborty DK (1990) The Great Andamanese. Seagull Books

Cipriani L (1966) The Andaman Islanders. Weidenfeld and Nicolson

Dutta PC (1978) Great Andamanese: past and present. Anthropological Survey of India

Justin A (2007) Post Earthquake Expedition to the North Sentinel Island. In: Anthropological Survey of India (ed) Tsunami in South Asia: Studies on Impact of Tsunami on Communities of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Allied Publishers Private Limited, p 139–154

Karthick T (2023) Three Wandoor Fishermen Missing, Their Boat Spotted at North Sentinel Island. Nicobar Times, https://nicobartimes.com/local-news/three-wandoor-fishermen-missing-their-boat-spotted-at-north-sentinel-island/. Accessed 18 Jul 2024

Mandal S (2018) How Bible saved John Allen Chau during first arrow blitz. The Telegraph. https://www.telegraphindia.com/india/how-bible-saved-john-allen-chau-during-first-arrow-blitz-on-ill-fated-andamans-trip/cid/1676271. Accessed 26 Jan 2024

Man EH (1932) The Andaman Islanders. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, London

Mann RS (1981) Animism, Economy, Ecology and Change among Negrito Hunters and Gatherers In Mann RS (ed) Nature-Man-Spirit Complex in India. Concept Publishing Company, p 179–208

Milliken W, Albert B, Gomez GG (1999) Yanomami: A forest People. The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Mukhopadhyay K, Bhattacharya RK, Sarkar BN (eds) (2008) Jarawa Contact: ours with them, theirs with us. Anthropological Survey of India

Palanichamy MG, Agrawal S, Yao YG, Kong QP, Sun C, Khand F, Chaudhuri TK, Zhang YP (2006) Comment on ‘Reconstructing the Origin of Andaman Islanders, Science 311–470

Pandit TN (1990) The sentinelese. Seagull Books

Pandya V (2009) Through lens and text: constructions of a ‘stone age’ tribe in the Andaman Islands. Hist Workshop J 67:173–193

Portman MV (1899) A History Of Our Relations With The Andamanese Vol. I & II. Office Of The Superintendent Of Government Printing, India

Radcliffe-Brown AR (1922) The Andaman Islanders. Cambridge University Press

Radcliffe-Brown AR (1948) The Andaman Islanders, Reprint. The Free Press

Reddy S (2007) Mega tourism in Andaman and Nicobar Islands: some concerns. J Hum Ecol 21(3):231–239

Sarkar JK, Pandit TN (1994) Sentinelese. In Singh KS (ed) People of India: Andaman and Nicobar Island Vol. XII. East-West Press, p 184–187

Sasikumar M (2018) The Sentinelese of the North Sentinel Island: Concerns and Perceptions. J. Anthropol Surv India 67(1):37–44

Sasikumar M (2019) The sentinelese of North Sentinel Island: a reappraisal of tribal scenario in an Andaman Island in the context of killing of an American preacher. J Anthropol Surv India 68(1):56–69

Sasikumar M (2023) The Sentinel Islanders: The Most Isolated Tribe In the World. Anthropological Survey of India, Manohar

Sharma A (2018) High-level recce team sent to North Sentinel Island: Administration faces challenges in retrieving body of American National from Tribal Island. Andaman Sheekha. https://www.andamansheekha.com/68063/. Accessed 30 Dec 2023

Survival International (n.d.) The Sentinelese. Survival International. https://www.survivalinternational.org/tribes/sentinelese. Accessed 26 Jan 2024

Singh SS (2021) Hands off, eyes on the Sentinelese: M. Sasikumar. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/society/hands-off-eyes-on-the-sentinelese-m-sasikumar/article33757682.ece. Accessed 25 Jan 2024

Srivastava VK (1993) Anthropology is not a romantic pedagogy. East Anthropologist 46(1):85–90

Srivastava VK, Kumar U, Sasikumar M, Pulamaghatta VN, Patel SK, Goyal PA (2020) Draft of the policies for great Andamanese and Sentinelese. J Anthropol Surv India 69(1):165–176

Som, V (2018) Attacked By Andaman Tribe, Coast Guard Officer’s Terrifying Account. NDTV. https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/north-sentinel-island-they-attacked-my-chopper-officers-encounter-with-remote-andaman-tribe-1952354. Accessed 26 Jan 2024

Saxena KB, Sahay VS, Roy S, Pandit TN (2021) Comments on ‘Draft of the Policies for Great Andamanese and Sentinelese’ published in journal of Anthropological Survey of India, 69(1), 165-176. J Anthropol Surv India 69(2):290–306

Venkateswar S (1999) The Andaman Islanders. Scientific American: American Edition:83-88

Venkateswar S (2004) Development and Ethnocide: Colonial Practices in the Andaman Islands. International Work Group For Indigenous Affairs, Demark

Venkateswar S (2007) Of cyclones, Tsunamis and the engaged anthropologist: Some musings on colonial politics in the Andaman Islands. Massey Univ. Centre for Indigenous Governance and Development

Wallace S (2016). Rare Photos of Brazilian Tribe Spur Pleas to Protect It. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/Brazil-uncontacted-indigenous-tribe-Yanomami-photos Accessed 13 Jul 2024

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Each author has contributed significantly to the conception and outline of the present review article. Sabatini Chatterjee played a key role in the initial conceptualization and methodological part of the review article. Satyaki Paul focused on the analysis and execution of the entire research. Anstice Justin provided valuable information such as observations from the field, photos, and videos during his expedition to the North Sentinel Island. Anstice Justin also guided Satyaki Paul throughout the entire research process. Anstice Justin also guided Satyaki Paul to vet the manuscript as per the aims and scope of the esteemed Journal.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This review article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors. Data are coming from reference books such as Portman (1899), Radcliffe-Brown (1922; 1948), Bonington (1932), Cipriani (1966), Pandit (1990), Justin (2007), Sasikumar (2023).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Paul, S., Justin, A. & Chatterjee, S. Sentinelese contacts: anthropologically revisiting the most reclusive masters of the terra incognita North Sentinel Island. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1512 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03994-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03994-3