Abstract

Despite extensive research on leadership’s role in influencing employee outcomes, there is limited understanding of the specific impact of servant leadership on employee task performance. Little is known about how servant leadership enhances employee promotive voice behavior, which in turn influences task performance. Additionally, the potential moderating role of leader-leader exchange in this relationship has been underexplored, leaving a gap in understanding how interactions between leaders may further shape these outcomes. Based on social exchange theory, this study examined how servant leadership affects employee task performance through the mediating role of employee promotive voice and the moderating role of leader-leader exchange. Using a time-lagged data collection approach, data for this study were gathered from 392 employees working in project-based organizations in the information technology sector in Pakistan. The study’s hypotheses were tested using structural equation modeling and the Process Hayes Model. The findings reveal that servant leadership significantly influences employee task performance by mediating the role of employee promotive voice. Furthermore, it was confirmed that leader-leader exchange positively moderates the relationship between employee promotive voice and task performance. This research, further adds to the existing pool of knowledge that holds implications for organizations, top management, academia, researchers, and government concerning leadership behaviors, promotive voice, employee task performance, leader-leader exchange, and preparation for challenges in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Leadership is a multifaceted notion in the operation and development of an organization, encompassing a variety of skills and attributes essential for effectively guiding and motivating teams to achieve organizational goals (Inamdar 2021; Robertson and Williams 2006). The shift from conventional leadership to a serving style in the era of digitization and competitive work settings has focused on strategic decision-making, fostering innovation, and cultivating a culture of adaptability (Erhan et al. 2022). Effective leadership is crucial for achieving organizational goals and developing a productive and talented team. Therefore, investigating the impact of leadership on organizational performance is essential in both academic and practical domains (Keegan et al. 2018; Ludwikowska et al. 2024). In recent years, research has shifted its attention from technical aspects to the human side, emphasizing the influence of leaders on project planning, execution, goal clarity, teamwork, project performance, and success (Nauman et al. 2022). While leadership style is considered crucial in a project context, few studies have focused on measuring task performance within project teams. In many cases, research has relied on leaders’ self-reports of team performance (Bilal et al. 2020). Leadership style plays an essential role in project management effectiveness (Alrowwad et al. 2020; M. Zada et al. 2023). A project, therefore, necessitates leadership and management that can adeptly adapt to various aspects while leading the team (Ahmad et al. 2022) and remain mindful of both employees and the organization (Evans and Farrell 2023). Servant leadership (SL) is considered the most suitable leadership style in a project management context, as it prioritizes the interests of subordinates and the team over self-interest (Y. Zhang et al. 2021). Consequently, a servant leader not only serves the project team (R. K. Greenleaf 1997) but also encourages the team to accomplish the organization’s goals (Nauman et al. 2022; Van Dierendonck et al. 2017). Hale and Fields (2007) argued that SL not only fosters positive behavior among followers through effective dialogue, encouragement, and decision-making but also sets an example through personal actions and interpersonal interactions. As a result, SL can facilitate the development of essential skills to support project teams (Ellahi et al. 2022). On the other hand, there are limited studies that investigate the relationship between ETP in project-based organizations and SL in-depth, such as those by (Bilal et al. 2020; Tuan 2021).

More specifically, Khattak and O’Connor (2020) recently highlighted that the principle of reciprocity is fundamental to improving performance through SL. Poor or positive relationships between employees and their team leader may be significant factors, particularly for those who experience leadership in a serving manner, which supports the concepts of social exchange theory (Panaccio et al. 2015). Strong social exchanges develop between employees and servant leaders, and as a result, task performance may be greatly enhanced for those individuals (Liden et al. 2008). However, the development of a good relationship between a supervisor and employee is not solely a matter of direct reciprocity of goodwill (Detert and Burris 2007). Supervisors are also crucial leaders of their groups, and this dynamic is influenced by the decisions made within the team (Le Blanc and González-Romá 2012). As affirmed by the literature, teams led by servant leaders feel free to voice their ideas and are encouraged to be uninhibited. Consequently, their supervisors are likely to make better decisions (M. Chen et al. 2022).

Recent studies have focused on the promotive voice and its influence on performance, suggesting a gap in the literature concerning the interaction between employees’ promotive voice (EPV) and servant leadership within project-based organizational contexts (Liang et al. 2012; Song et al. 2021). Research shows that employees’ promotive voice, where employees proactively suggest improvements and innovations, enhances individual performance by fostering engagement, ownership, and alignment with organizational goals. This behavior leads to greater motivation, creative collaboration, and efficiency, ultimately improving task performance (H. Chen et al. 2021; M. Zada et al. 2024). Encouraging promotive voice also strengthens relationships with leadership, further boosting individual-level performance (Van Dyne (Van Dyne and LePine 1998). While prohibitive voice orients to identify the detrimental behaviors and prevent them, promotive voice orients to proactive problem-solving strategies to develop innovative solutions (Liang et al. 2012). In this respect, it is relevant to analyze the interaction between employees and supervisors based on a social exchange in the team environment. Servant leadership is an approach toward leadership that emphasizes selfless attention to followers’ and the entire organization’s needs, resulting in heightened performance and job satisfaction of workers (Sousa and van Dierendonck 2021). Despite this fact, how servant leadership promotes employee task performance through the creation of an environment promotive of voice is an underexplored mechanism until now (Wu and Zhou 2024). Therefore, the primary objective of this study is to examine the significance of employees’ promotive voice as a crucial social exchange-based link in employee-supervisor relationships within teams that follow a servant leadership approach.

By gaining insights into this relationship, we aim to clarify how servant leadership can effectively leverage and strengthen employees’ promotive voice, leading to improved task performance and driving organizational success. Therefore, the primary goal of this study is to examine employees’ promotive voice as a crucial social exchange-based link between subordinates and their supervisors within the pivotal team and how it facilitates the influence of servant-style managers on employee task performance. The relationship between employees and supervisors is a fundamental aspect of organizational networks (Imam et al. 2023). However, the existing literature has largely overlooked the impact of exchange relationships between supervisors and their higher-level leaders, also known as Leader-Leader Exchange (LLX) (Lorinkova and Perry 2017; L. Zhou et al. 2012). L. Zhou et al. (2012) assert that various leadership studies have revealed that effective LLX fosters positive working relationships between supervisors and their higher-level counterparts. Strong LLX allows supervisors to allocate critical resources such as financial support, time, and guidance, enabling employees to capitalize on organizational resources and improve their performance. However, poor LLX can also reduce the ability of employees to access and exploit available resources, hence poor performance (Afzal et al. 2019). In effective social exchange theory, identification and cohesion between an individual and their partner in exchange are a function of interactions (Lawler 2001). With the contributions of both partners in a relationship, that is, supervisors and employees in this case, their exchange will generate greater benefit for both parties, as noted by (Berg 1984; He et al. 2020; Lawler 2001). By exploring the dynamics of LLX and the impact thereof on employee-supervisor relationships, the study aims to add to the understanding of what may be certain underlying processes through which successful workplace relationships result in better organizational performance. In some cases, supervisors may encounter limited organizational resources yet still manage their teams effectively by providing motivation and encouragement. In this leadership scenario, employees may contribute valuable ideas and work efficiently, thereby helping the organization achieve its objectives (J. Khan et al. 2024).

This study aims to address a fundamental question related to contexts where SL behaviors are prevalent and potentially valued by employees. The concept of LLX remains relatively underexplored in existing scholarship, highlighting an important yet often overlooked area of research. As a result, the secondary goal of this study is to examine the impact of LLX as a boundary condition in the relationship between employee promotive voice and subordinate employee task performance. By exploring the moderating role of LLX, this study seeks to provide a more nuanced understanding of how servant leadership operates within different organizational contexts to influence employee performance, ultimately contributing to organizational success. The present study contributes on both practical and theoretical standpoints in the existing literature on SL and employee-supervisor dynamics. Unlike previous studies, which have mostly emphasized how servant supervisors’ behavior interacts with their teams within employee-supervisor dyads, the approach taken within the confines of this study puts a different perspective on alternative standpoints such as exchange mechanisms like promotive voice. The study integrates the ideas of Social Exchange Theory with servant leadership and employee voice in an effort to explain the conditions under which SL most effectively develops subordinates’ voices and advances the performance of employees’ tasks.

While stimulating, the integration of social exchange theory into servant leadership might provide a more viable way to understand and improve organizational dynamics (Ruiz‐Palomino et al. 2023). Social exchange theory points to mutualism, or the idea of the exchange of resources, which directly intersects with the core functions of servant leadership: empathy, empowerment, and responding to other people’s needs (Bavik 2020). This intersection creates a synergistic relationship whereby the focus of SET on mutually beneficial exchanges aligns with the emphasis of SL on selfless service and fostering positive relationships (Liden et al. 2014). n this connection, Liden et al. cite the fact that in a servant leadership framework, leaders could make the difference by establishing an environment of trust and support where the quality of social exchanges among team members was heightened. In contrast, the insight of SET in the dynamics of exchange relationships may be important to the servant leader to demonstrate that justice, trustworthiness, and reciprocity are implicated within the interaction (Bavik 2020). A more explicit discussion of these intersections and complementarities would increase the theoretical underpinning that subtleties the understanding of how servant leadership influences and is influenced by social exchanges and vice versa, leading to effective leadership practice in achieving desired organizational outcomes (Brohi et al. 2018; Chan and Mak 2012). By incorporating these theoretical frameworks, the study seeks to find answers for these unresolved questions: (1) How servant leadership influences employees’ promotive voice, and further, how employees’ promotive voice relates to task performance? and (2) The extent to which leader-member exchange mediates the relationship between employees’ voice and task performance. Finally, the study implies practical uses for business and project management professionals on how full benefit exploitation can be derived from servant leadership. With the project managers being aware of what brings success to teams that are servant-led, they will able to encourage employee voices so that this kind of leadership style contributes to better performance and realization of organizational objectives.

Literature review and hypotheses development

Servant leadership, employees’ promotive voice, and employee task performance

Servant leadership (SL) has garnered considerable attention in recent years due to its focus on serving the needs of employees, fostering a supportive and empowering environment that encourages personal growth and development (Ghahremani et al. 2024). Researchers have sought to understand the impact of SL on various organizational outcomes, emphasizing proactive problem-solving strategies and the generation of innovative solutions (Brohi et al. 2018; Chan and Mak 2012). Recent research highlights the significant influence of SL on promoting open communication and knowledge sharing within teams (Liden et al. 2014). For instance, research by Song et al. (2022) found that SL positively influenced employees’ promotive voice (EPV) through the mediating role of psychological empowerment.

Employees working under servant leaders were more likely to feel empowered and confident in their abilities, fostering a sense of personal control and an increased likelihood of voicing their ideas and concerns (Wu and Zhou 2024; Zou et al. 2015). Jia Hu and Liden (2011) investigated the effect of leader-member exchange (LMX) on the association between servant leadership and employees’ promotive voice. The study revealed that high-quality LMX relationships, marked by understanding, trust, support, and respect within teams, mediated the favorable effect of servant leadership on employees’ promotive voice. This research underscores the significance of robust interpersonal relationships in enabling transparent communication and the sharing of ideas within organizational settings. Moreover, S. Zada et al. (2022) investigated the role of psychological safety in the association between SL and knowledge sharing. Their findings revealed that when employees perceived a psychologically safe environment fostered by servant leaders, they were more inclined to exhibit a promotive voice. These results emphasize the importance of creating a learning atmosphere where employees feel relaxed and willing to share knowledge and innovative ideas without concerns. Despite the literature on the relationship between SL and EPV, further research is needed to explore other potential mediators and moderators of this relationship, such as organizational culture, team dynamics, and individual differences (Christopher 2023).

Additionally, longitudinal and experimental studies could provide valuable insights into the causal relationships between servant leadership, promotive voice, and organizational outcomes. The present study supports the notion that workers believe their leaders make decisions highly aligned with the team’s goals and objectives, as supported by (Alobeidli et al. 2024; Huang et al. 2021). This creates a team-oriented environment where supervisors show concern and consideration for their subordinates, encouraging employees to share constructive ideas on how performance can be improved within the team. According to (Eriksen and Srinivasan 2024; Zarei et al. 2022) and Varela et al. (2019), the term “promotive voice” refers to how employees take initiative to transform an inefficient workplace into a more effective and productive one through prosocial behavior. This promotive voice is also a form of exchange-based prosocial action (Sherf et al. 2021; Van Dyne and LePine 1998). It involves prosocial actions grounded in mutual exchange (Gong 2024; Ma and Bennett 2021). Therefore, servant leadership is suggested to significantly enhance employees’ promotive voice in two key ways. First, servant leadership fosters a promotive voice by creating a work culture of care, support, and equity. Second, servant leaders promote their employees by adhering to service-oriented principles, rewarding those who meet expectations and perform appropriately. This guarantees a supportive culture that frees employees from the fear of taking risks while expressing their opinions (Y. Zhang et al. 2024). Consequently, employees find it easier to align themselves with their servant leader and the team, proactively offering suggestions on team ethics and proposing new ways to improve team performance.

Servant leadership exhibited by supervisors provides the team with a diverse set of resources, including material, ethical, physical, and psychological support (M. M. Khan et al. 2022; Lei et al. 2023; Van Dyne and LePine 1998). These resources form a strong foundation that fosters the open expression of ideas and the implementation of innovative strategies, benefiting the team as a whole. This, in turn, enhances work processes through constructive feedback and promotes teamwork among employees, as noted by (Bhatti et al. 2021; Yan and Xiao 2016). Hobfoll (2001) “resource caravans” concept, based on the conservation of resources theory, supports this scenario. A servant leader, according to Hobfoll (2011), may possess a sufficient pool of resources due to a positive approach toward resource gain, which can be applied to maximize employee productivity. By investing resources in subordinates, servant leaders create an environment of abundance, leading to positive employee behaviors and improved performance (Han et al. 2024). As a result, it is suggested that leaders can encourage employees’ proactive voice within the team by fostering high-quality relationships with subordinates.

H1: Servant leadership positively related to employee task performance

Robert K Greenleaf (1970) popularized the concept of servant leadership, where the primary responsibility of the leader is to foster the growth and development of their followers. It is characterized by key attributes such as listening, empathy, healing, heightened awareness, persuasion over authority, conceptualization, foresight, stewardship, and a commitment to growing people (Mishra and Hassen 2023). Consequently, servant leaders invest energy in their employees’ personal and professional development within a supportive and inclusive environment that promotes overall well-being. The dyadic relationship between servant leaders and their employees is another important aspect derived from the literature on servant leadership (M. M. Khan et al. 2022). This relationship can enhance the individual performance of the servant leader by facilitating promotive voice among employees (L. Gao et al. 2011; Yan and Xiao 2016). As a result, employees are more likely to contribute positively and build relationships because they feel supported by their servant leader (Burris 2012; Franco and Antunes 2020). In other words, employees are more inclined to provide positive, promotive voice to their teams, helping strengthen relationships with others. Promotive voice essentially means that employees assist their teams in adapting to change and bringing deliverables to fruition (Irshad and Naqvi 2023). Previous studies affirm that servant leadership positively correlates with employees’ promotive voice. For instance, Song et al. (2022) found that servant leadership creates enabling work environments, inspiring employees to generate and share ideas. Similarly, Mohammad et al. (2023) found that employees who perceive their immediate supervisors as servant-oriented are more likely to engage in promotive voice behaviors. The two most important mechanisms underlying this relationship are psychological safety and empowerment. Servant leadership fosters trust and respect, which enhances psychological safety and promotes voice behavior among employees (Morrison 2023; Ye et al. 2023). Servant leaders also develop employees’ self-efficacy by providing more autonomy and authority over their work, thereby increasing their confidence in engaging in promotive voice behaviors (Guchait et al. 2023). Recent research suggests that employees working under a servant-oriented supervisor are more likely to suggest innovative ideas to help the organization improve than those under non-servant-oriented leaders (Kumar et al. 2024). This voice behavior enables employees to secure additional organizational resources, which later helps them improve their individual task performance (Shipton et al. 2024). Moreover, employees who are highly promotive are likely to receive feedback and favorable performance evaluations from their leaders, thereby enhancing their productivity. Detert and Burris (2007) also established that promotive voice is one of the major avenues through which servant leadership positively impacts employee performance.

H2: Employee’s promotive voice mediates the path between servant leadership and employee task performance”.

Moderating role of leader-leader exchange

Servant Leadership is a leadership philosophy that prioritizes people, emphasizing the leader’s commitment to the well-being and development of those they lead (Y. Zhang et al. 2021). The Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) theory posits that the key factor in organizational influence is the quality of the leader-follower relationship between the leader and the subordinate (Demeke et al. 2024). Contemporary studies have explored the connection between LMX and Servant Leadership (Yıkılmaz and Sürücü 2023). Social Exchange Theory further elaborates that various forms of exchange affect an individual’s sense of attachment and identification within the exchange (Lawler 2001). When individuals receive support through this exchange, it strengthens their feelings of attachment (Berg 1984; Lawler 2001). Employees are expected to identify with leaders, supervisors, and organizations that provide robust physical and psychological support to achieve (Berg 1984; Detert and Burris 2007). The concept of Servant Leadership is applicable in organizations where both the servant leader and their subordinates are influenced by the leader’s relationship with higher management, or the “leader-leader exchange (Z. Gao et al. 2024; Lorinkova and Perry 2017). Supervisors who maintain reciprocal relationships with their superiors have easier access to resources, such as project timelines, budgets, stakeholder management, and other internal and external supports (Tangirala et al. 2007; K. Zhang et al. 2021). Therefore, leader-leader exchange indicates the extent to which supervisors are likely to receive support from the resource exchange system in their organization (Lorinkova and Perry 2017). Accordingly, we predict that leader-leader exchange positively moderates the individual-level relationship between servant leadership and promotive voice. For instance, if a lower-level leader faces resource constraints, their servant leadership may become a key factor that enhances employees’ promotive voice. This leadership style enables employees to offer constructive suggestions, which increases motivation and performance, as they perceive both their team and leadership to be equally committed to helping one another and providing mutual support during resource shortages (Berg 1984; Lawler 2001). Even if leaders sacrifice resources to achieve organizational objectives, team members involved in the team-building process contribute positively by offering valuable feedback and suggestions (Lv et al. 2022). This dynamic, often referred to as team development, is closely tied to the supervisor’s servant leadership behavior. Through this process, employees transform challenging work environments into productive ones by maximizing available resources (Ng and Feldman 2012; W. Zhou et al. 2024). Conversely, if the supervisor has significant access to organizational resources and thus enjoys a competitive advantage, subordinates may perceive this as routine (Kumar et al. 2024). In such cases, the supervisor may be seen as merely utilizing resources easily provided by top management, resulting in a weaker relationship between the employee and supervisor. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 states:

H3: Leader-leader exchange moderates the positive relationship between employee’s promotive voice and employee task performance.

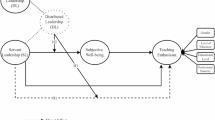

Employee promotive voice behavior has been found to facilitate individual learning and improve job task delivery, thereby helping employees develop new skills and make better decisions (Burris 2012; W. Chen et al. 2024; Van Dyne and LePine 1998). Additionally, such behavior can enhance performance by enabling employees to take on additional tasks and utilize resources more effectively, leading to increased task performance in a corporate setting (López-Cabarcos et al. 2022). In line with this, we propose Hypothesis 4, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

H4: The indirect effect of SL on ETP via EPV is moderated by LLX such that when LLX is high the indirect effect is significant and stronger while the indirect effect is weaker when LLX is low.

Method

Research design and approach

The study utilized a cross-sectional quantitative research design, with data collected through a questionnaire survey. The data were analyzed using SPSS and AMOS, Version 26. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) and the Process Hayes Model (moderation mediation) were employed to assess the associations among the study variables. SEM was chosen for its confirmatory approach to analyzing structural theory related to a phenomenon, allowing researchers to simultaneously examine interdependent relationships (Babin and Svensson 2012). SEM was also considered ideal because, unlike CFA, it enables the exploration of interrelationships among unobserved variables through both measurement and structural models.

Sample and population

The sample size targeted for this research includes all project-based IT organizations operating in Pakistan. Data collection was conducted through a systematic procedure. First, permission was sought from five leading IT companies in Islamabad, Rawalpindi, Peshawar, and Taxila for data collection. In this research, the sample size calculation was carried out in accordance with guidelines advocated by Palinkas et al. (2015), ensuring that the sample size was adequate, representative, stratified, and well-balanced. Senior management was contacted first to request consent. After obtaining informal permission and with the support of the HR department, the survey was distributed to employees involved in projects using convenience sampling (Oladinrin and Ho 2016). Convenience sampling was chosen because it is affordable, easy, and the subjects were readily available (Emerson 2015). Although convenience sampling has limitations, such as potentially compromising the robustness of statistical inferences, it was selected for several reasons. First, it allows for post-hoc adjustments, like weighting or bootstrapping. Second, this approach can enhance the credibility of the results despite the non-random nature of the sample, particularly when the study aims to explore preliminary or exploratory relationships. We determined that a two-week time lag was appropriate for our research. This duration was selected because it provided “sufficient spacing to reduce the risk of common method bias while remaining short enough to ensure participant retention” (Quade et al. 2020, p. 1172). The questionnaires were administered in three waves: the first wave (Time 1) collected demographic information along with items on servant leadership and leader-member exchange. The second wave (Time 2) focused on measuring employees’ perceptions of promotive voice, while the third wave (Time 3) assessed overall task performance. The first wave yielded 464 responses from 475 employees. After follow-up and collection of responses from participants who completed the initial questionnaire, we received 437 valid responses, resulting in an overall response rate of 92%. At the third stage, two weeks later, we received 407 questionnaires, amounting to an 85.68% response rate. Among the 407 retrieved questionnaires, 15 had incomplete responses and were thus excluded from the analysis. Therefore, the final sample included 392 participants, yielding an 82.52% response rate. There were more male respondents in the sample than females: 237 males, constituting 60.46%, and 155 females, making up 39.54%. About one-third of the total respondents (34.69%) were in the 21–30-year age bracket. Working experience ranged between 1 and 7 years for 180 participants, while 310 held master’s degrees (See Table 1).

Measurement

he constructs were evaluated using pre-existing scales, employing a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Servant leadership was assessed by Liang et al. (2012), with a seven-item scale, which demonstrated a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.75. Similarly, Leader-Member Exchange was evaluated using a seven-item scale by Liang et al. (2012), showing a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.79. Employee promotive voice was measured using a five-item scale by Liang et al. (2012), which exhibited a high reliability coefficient of ɑ = 0.98. Furthermore, employee task performance was assessed with a seven-item scale developed by (Williams and Anderson 1991), demonstrating a reliability coefficient of ɑ = 0.97. The study also controlled for respondents’ experience, gender, age, and educational level, as these variables could potentially impact project effectiveness (Aga et al. 2016).

Results

The descriptive statistics for the study variables are presented in Table 2, including the mean, standard deviation, and correlation values. As predicted by our theoretical framework, the zero-order correlations for the study variables—servant leadership, leader-leader exchange, promotive voice, and task performance—exhibited the expected directional relationships. Notably, the strongest correlation was observed between servant leadership and leader-leader exchange, with a correlation coefficient of r = 0.960, p < 0.01. Further details can be found in Table 2.

Measurement model

A CFA was conducted using AMOS 26, with scale items treated as indicators for all constructs to assess the relationships among the study variables. Given that common method bias is a concern in survey studies, Harman’s single-factor test was employed to check and ensure the quality and validity of the data collected through the survey questionnaires. This approach enhances the robustness of the measures used to detect any biases that might distort the accuracy of the results. The results, presented in Table 3, indicated that the hypothesized four-factor model fit the data fairly well when compared with competing models (X² = 3474, df = 1214, TLI = 0.91, CFI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.05). Moreover, all four factors had standardized factor loadings within acceptable ranges, further confirming good model fit and construct validity Table 3.

Regression assumption

Prior to estimating the structural model, the researcher examines the regression assumptions. The first assumption is data normality. Hair et al. (2012) recommend analyzing the distribution and using visual depictions to assess data normality (Field et al. 2009; Tabachnick et al. 2007). The scholar used a visual method, specifically a histogram, to measure data normality. A bell-shaped curve, shown as a normal curve, indicates data normality (see Fig. 2). Skewness and kurtosis were also assessed, with a standard score of (+/–) 3 used as a benchmark for data normality, as suggested by (2003). The results showed that the standard scores for skewness and kurtosis fall within the appropriate range, confirming that the data meets the assumption of normality (see Table 4).

Autocorrelation was evaluated using the Durbin-Watson technique. The values can range from 0 to 4, with a value of 2 indicating little to no autocorrelation. A statistic of 1.91 shows that the data is free from significant autocorrelation concerns. Multicollinearity refers to predictors that are highly correlated with each other. Tolerance and VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) statistics are used to assess multicollinearity. O’brien (2007) stated that tolerance values greater than 0.20 and VIF values below 10 indicate no multicollinearity concerns. According to the statistics in Table 5, there is no evidence of multicollinearity.

Direct path and mediation analysis

Table 6 and Fig. 3 also present the positive relationship between servant leadership (SL) and employee task performance (ETP), as indicated by the following statistical values: β = 0.12, SE = 0.06, t = 5.73, p < 0.001, and confidence intervals (CIs) of 0.041 to 0.214. This suggests that an increase in servant leadership is significantly related to an increase in employee task performance. The t-value and p-value indicate statistical significance, while the confidence interval, which is well above zero, further reinforces this positive relationship.

Step 1: Servant Leadership (SL) → Employee Promotive Voice (EPV)

The results indicate that Servant Leadership (SL) is positively related to Employee Promotive Voice (EPV) (β = 0.23, SE = 0.04, t-value = 7.17, p-value < 0.001, 95% CI [0.182, 0.306]). This suggests that higher levels of Servant Leadership are associated with higher levels of Employee Promotive Voice. The statistical significance is supported by the t-value and p-value, and the confidence interval confirms a positive relationship.

Step 2: Employee Promotive Voice (EPV) → Employee Task Performance (ETP)

The results show that Employee Promotive Voice (EPV) is positively related to Employee Task Performance (ETP) (β = 0.27, SE = 0.04, t-value = 15.30, p-value = 0.000, CIs [0.537; 0.696]). This indicates that an increase in Employee Promotive Voice is associated with an increase in Employee Task Performance. The t-value and p-value demonstrate that the relationship between the variables is statistically significant. The results also reveal that the indirect effect of SL on ETP through EPV is statistically significant (β = 0.06, SE = 0.03, t-value = 5.68, p-value = 0.000, CIs [−0.303; −0.146]). This suggests that EPV mediates the relationship between SL and ETP. Additionally, considering the t-value, p-value, and confidence intervals, the statistical significance is reinforced, confirming a meaningful mediating effect.

Moderation and moderation mediation

The results show that the interaction effect of Employee Promotive Voice (EPV) and Leader-Leader Exchange (LLX) on Employee Task Performance (ETP) is significant (β = 0.17, SE = 0.06, t = 6.13, p = 0.000, 95% CI [0.048, 0.427]). This suggests that the relationship between Employee Promotive Voice and Employee Task Performance is moderated by Leader-Leader Exchange. To support the interpretation of this moderated effect, we applied Cohen (2003) approach. Figure 4 displays the interactions between Servant Leadership and Employee Promotive Voice at ±1 standard deviation from the mean of Leader-Leader Exchange. A simple slope test was conducted to evaluate the strength of the significant relationship between Servant Leadership and Employee Task Performance at both high and low levels of Leader-Leader Exchange. Furthermore, the results indicate that the moderated mediation effect of Servant Leadership (SL) on Employee Task Performance (ETP) through Employee Promotive Voice (EPV), moderated by Leader-Leader Exchange (LLX), is significant (β = 0.14, SE = 0.03, t = 3.43, p = 0.001, 95% CI [0.091, 0.209]). This means that leader-leader exchange further moderates the indirect effect of servant leadership on employee task performance through employee promotive voice Table 6.

Discussion

In the last decade, there has been a growing interest among researchers and corporate entities in studying the underlying mechanisms that drive employee performance through servant leadership (Aryee et al. 2023; Hartnell et al. 2023; Liden et al. 2014). Whereas previous research has primarily focused on LMX processes, the present study develops a new social exchange mechanism that is crucial for team performance: employees’ promotive voice. The main objective of this research is to investigate how LLX moderates the effect of promotive voice on SL within a social exchange framework. Previous studies have documented the positive influence of servant leadership on employees’ promotive voice, which, in turn, enhances their individual task performance. This underscores how servant leadership improves employee task performance, with the relationship further mediated by a third mechanism that explains how servant leadership fosters employee task performance through social exchange processes and the promotion of voice. Results showed that LLX significantly moderates the relationship between SL and employee task performance, particularly through the mechanism of employee promotive voice. Indeed, it was found that, under conditions of low LLX, the positive association between servant leadership and employees’ promotive voice remained strong. This indicates that LLX can affect the influence of SL on employee task performance, as this interaction provides employees with an opportunity to express their promotive voice. According to Kelemen et al. (2023) and Tuan (2021), LLX can also facilitate the utilization of resources acquired from higher-level leadership, which supervisors are permitted to share with team members. This approach is focused solely on team performance rather than the performance level of individual employees, as noted by (M. Chen et al. 2022; Luu 2023). Having the necessary resources to achieve desired goals can be perceived as employee support and care on the part of supervisors, especially when working in resource-scarce environments. This strengthens the leader-member exchange (LMX) within the employee-supervisor relationship, even though the immediate supervisor may depend on higher-level leaders for support and resources. LMX sets the context for the influence of a supervisor’s behavior on an employee’s behavior toward their team. However, its influence tends to contrast with the social exchange dynamics in the leader-employee dyad.

Theoretical implications

The findings of the present study contribute significantly to existing theories. It extends social exchange theory by investigating a new dimension—the mechanism of voice—which can potentially enhance the influence of servant leadership (SL) on employee turnover intention (ETP) in the workplace. While previous studies on the social exchange mechanism of servant leaders primarily focused on leader-employee relationships, this study explores how the mechanism of voice amplifies the effects of SL on ETP (Jiajing Hu et al. 2023; Lv et al. 2022). It also introduces a new avenue for understanding employee voice and demonstrates that the social exchange framework of servant leadership can affect employee task performance by valuing employee suggestions and ideas. Encouraging individuals to voice their opinions can positively impact team performance and development. Therefore, dyadic mutual exchange relationships are not the sole foundation through which servant leadership enhances employee performance; the mechanism of voice also plays a significant role. This study further expands prior theories of servant leadership and leader-leader exchange by formulating a social exchange mechanism through which the two constructs interact. A substitution effect between servant leadership and leader-leader exchange is observed. Although previous research has explored various leadership styles and mechanisms of employee voice, contextual or situational factors that may affect leadership effectiveness have often been overlooked (Liden et al. 2014; Yıkılmaz and Sürücü 2023). Our study addresses this critical gap in the literature by emphasizing the importance of servant leadership within the workplace context.

Managerial implications

The findings of this study reveal several significant practical implications. On one hand, leaders should possess specific attributes that must be carefully assessed among job candidates. There must be sufficient assurance that anyone placed in a leadership position will demonstrate good practices, effective decision-making skills, and full commitment to their assigned tasks. Only then can an effective assessment of leadership qualities ensure organizational success in achieving desired outcomes (Fischer and Sitkin 2023; Joseph and Winston 2005). ervant leaders, in particular, provide their subordinates with care, support, and psychological trust to foster high performance in the workplace. According to Liden et al. (2014), Meuser and Smallfield (2023) and (Kim et al. 2021) concern for work activities is enhanced in employees under servant leadership; moreover, they may go above and beyond to provide productive feedback. These researchers also suggest that supervisors should be trained on the importance of encouraging employee input regarding their own performance. Supervisors should practice servant leadership, especially when resources are limited, and seek support from upper management rather than relying on peer supervisors. It is crucial for supervisors to recognize that team development and performance depend not only on strong organizational ties but also on the application of constructive leadership practices. In such cases, servant leadership is instrumental in driving motivation among team members to collaborate on their mutual goals, regardless of power dynamics or resource availability.

Research limitations and future directions

The present study demonstrates several strengths, particularly regarding the holistic investigation of the relationships between various variables from multiple viewpoints and dimensions. More importantly, it focuses on the intricate linkages between SL, LLX, and ETP using an advanced cross-level framework. This is significant as it deviates from the traditional focus of earlier studies, which primarily centered on individual or team-level measures of the leadership process. Moreover, the study’s methodology is robust, as it samples multiple sources over several points in time—a consideration that reduces method bias and aligns with the guidelines for longitudinal research. Several promising avenues for future research now emerge. First, the research design adopted in the current study is cross-sectional and quantitative in nature. To establish more valid and far-reaching results, longitudinal studies that assess the relationship between SL, LLX, and ETP over time should be considered. This approach would provide an in-depth examination of the interactions and evolution of these variables. It would also be valuable to investigate possible mediating or moderating variables that may influence the relationships among SL, LLX, and ETP. Additionally, contextual influences such as organizational culture, industry type, and leadership styles would be crucial in unraveling the dynamics of these relationships. Furthermore, with the increasing globalization of work, comparisons between diverse cultural contexts could explain the universal nature or cultural specificity of the relationships under examination. These directions open up new opportunities for knowledge development, which may embed practical implications for organizational leadership and performance management (Podsakoff et al. 2012). The general path-analytic framework was also applied to test the different hypothesized relationships and to assess the research model as developed (Preacher et al. 2010). This approach addresses the problems of causal steps and piecemeal methods for estimating mediation relationships, making the results more reliable (Bauer et al. 2006).

Conclusion

This study identifies the key aspect of the social exchange mechanism: the relationship between SL and EPV. The findings reveal that SL significantly and positively influences EPV, thereby enhancing employee performance in the workplace. Furthermore, the analysis indicates that LLX moderates the relationship between SL and EPV, with SL more likely to affect EPV when LLX is low. Overall, this research contributes to understanding social exchange mechanisms by explaining how servant leadership influences employee promotive voice. It also highlights the importance of considering cross-level LLX when assessing the effectiveness of SL in fostering effective social exchange.

Data availability

Data will be made available by contacting the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

References

Afzal S, Arshad M, Saleem S, Farooq O (2019) The impact of perceived supervisor support on employees’ turnover intention and task performance: mediation of self-efficacy. J Manag Develop https://doi.org/10.1108/jmd-03-2019-0076

Aga DA, Noorderhaven N, Vallejo B (2016) Transformational leadership and project success: the mediating role of team-building. Int J Proj Manag 34(5):806–818

Ahmad MK, Abdulhamid AB, Wahab SA, Nazir MU (2022) Impact of the project manager’s transformational leadership, influenced by mediation of self-leadership and moderation of empowerment, on project success. Int J Manag Proj Bus 15(5):842–864

Alobeidli SY, Ahmad SZ, Jabeen F (2024) Mediating effects of knowledge sharing and employee creativity on the relationship between visionary leadership and innovative work behavior. Manag Res Rev 47(6):883–903

Alrowwad AA, Abualoush SH, Masa’deh RE (2020) Innovation and intellectual capital as intermediary variables among transformational leadership, transactional leadership, and organizational performance. J Manag Dev 39(2):196–222

Aryee S, Hsiung H-H, Jo H, Chuang C-H, Chiao Y-C (2023) Servant leadership and customer service performance: testing social learning and social exchange-informed motivational pathways. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 32(4):506–519

Babin BJ, Svensson G (2012) Structural equation modeling in social science research: Issues of validity and reliability in the research process. Eur Bus Rev 24(4):320–330

Bauer DJ, Preacher KJ, Gil KM (2006) Conceptualizing and testing random indirect effects and moderated mediation in multilevel models: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods 11(2):142

Bavik A (2020) A systematic review of the servant leadership literature in management and hospitality. Int J Contemp Hospitality Manag 32(1):347–382

Berg JH (1984) Development of friendship between roommates. J Personal Soc Psychol 46(2):346

Bhatti KI, Husnain MIU, Saeed A, Naz I, Hashmi SD (2021) Are top executives important for earning management and firm risk? Empirical evidence from selected Chinese firms. Int J Emerg Markets 17(9):2239–2257

Bilal A, Siddiquei A, Asadullah MA, Awan HM, Asmi F (2020) Servant leadership: a new perspective to explore project leadership and team effectiveness. Int J Organ Anal 29(3):699–715

Brohi NA, Jantan AH, Qureshi MA, Bin Jaffar AR, Bin Ali J, Bin Ab Hamid K (2018) The impact of servant leadership on employees attitudinal and behavioural outcomes. Cogent Bus Manag 5(1):1542652

Burris ER (2012) The risks and rewards of speaking up: managerial responses to employee voice. Acad Manag J 55(4):851–875

Chan SC, Mak W-M (2012) Benevolent leadership and follower performance: the mediating role of leader–member exchange (LMX). Asia Pac J Manag 29(2):285–301

Chen H, Liang Q, Feng C, Zhang Y (2021) Why and when do employees become more proactive under humble leaders? The roles of psychological need satisfaction and Chinese traditionality. J Organ Change Manag https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.947092

Chen M, Zada M, Khan J, Saba NU (2022) How does servant leadership influences creativity? Enhancing employee creativity via creative process engagement and knowledge sharing. Front Psychol 13:947092

Chen W, Zheng B, Liu H (2024) How does social media use in the workplace affect employee voice? Uncovering the mediation effects of social identity and contingency role of job-social media fit. Internet Res https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-04-2023-0300

Christopher W (2023) Help Me Be Heard: The Effect of Servant Leadership, Psychological Safety, and Race on Employee Voice. Drexel University

Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken, LS (2003) Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum

Demeke GW, van Engen ML, Markos S (2024) Servant leadership in the healthcare literature: a systematic review. J Healthc Leadersh 16:1–14

Detert JR, Burris ER (2007) Leadership behavior and employee voice: is the door really open? Acad Manag J 50(4):869–884

Ellahi A, Rehman M, Javed Y, Sultan F, Rehman HM (2022) Impact of servant leadership on project success through mediating role of team motivation and effectiveness: a case of software industry. SAGE Open 12(3):21582440221122747

Emerson RW (2015) Convenience sampling, random sampling, and snowball sampling: how does sampling affect the validity of research? J Vis Impair Blind 109(2):164–168

Erhan T, Uzunbacak HH, Aydin E (2022) From conventional to digital leadership: exploring digitalization of leadership and innovative work behavior. Manag Res Rev 45(11):1524–1543

Eriksen M, Srinivasan A (2024) Reimagining the introductory management course: preparing students to be effective and responsible team and organizational members. Int J Manag Educ 22(2):100947

Evans M, Farrell P (2023) A strategic framework managing challenges of integrating lean construction and integrated project delivery on construction megaprojects, towards global integrated delivery transformative initiatives in multinational organisations. J Eng Des Technol 21(2):376–416

Field R, Hawkins BA, Cornell HV, Currie DJ, Diniz‐Filho JAF, Guégan JF, Oberdorff T (2009) Spatial species‐richness gradients across scales: a meta‐analysis. J Biogeogr 36(1):132–147

Fischer T, Sitkin SB (2023) Leadership styles: a comprehensive assessment and way forward. Acad Manag Ann 17(1):331–372

Franco M, Antunes A (2020) Understanding servant leadership dimensions: theoretical and empirical extensions in the Portuguese context. Nankai Bus Rev Int 11(3):345–369

Gao L, Janssen O, Shi K (2011) Leader trust and employee voice: the moderating role of empowering leader behaviors. Leadersh Q 22(4):787–798

Gao Z, Liu Y, Zhao C, Fu Y, Schriesheim CA (2024) Winter is coming: an investigation of vigilant leadership, antecedents, and outcomes. J Appl Psychol https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0001175

Ghahremani H, James Lemoine G, Hartnell CA (2024) The influence of servant leadership on internal career success: an examination of psychological climates and career progression expectations. J Leadersh Organ Stud 31(2):125–145

Gong T (2024) Unraveling the impact of unethical pro-organizational behavior: the roles of manager-employee exchange, customer-employee exchange, and reciprocity beliefs. Curr Psychol 1–15 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05737-8

Greenleaf RK (1970) The Servant as a leader, Servant leadership. Centre Appl Stud https://leadershiparlington.org/pdf/TheServantasLeader.pdf

Greenleaf RK (1997) The servant as leader. University of Notre Dame Press https://leadershiparlington.org/pdf/TheServantasLeader.pdf

Guchait P, Peyton T, Madera JM, Gip H, Molina-Collado A (2023) 21st century leadership research in hospitality management: a state-of-the-art systematic literature review. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 35(12):4259–4296

Hair JF, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Mena JA (2012) An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J Acad Mark Sci 40(3):414–433

Hale JR, Fields DL (2007) Exploring servant leadership across cultures: a study of followers in Ghana and the USA. Leadership 3(4):397–417

Han M, Zhang M, Hu E, Shan H (2024) Fueling employee proactive behavior: the distinctive role of Chinese enterprise union practices from a conservation of resources perspective. Hum Resour Manag J 34(1):158–176

Hartnell CA, Christensen-Salem A, Walumbwa FO, Stotler DJ, Chiang FF, Birtch TA (2023) Manufacturing motivation in the Mundane: servant leadership’s influence on employees’ intrinsic motivation and performance. J Bus Ethics https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-023-05330-2

He P, Sun R, Zhao H, Zheng L, Shen C (2020) Linking work-related and non-work-related supervisor–subordinate relationships to knowledge hiding: a psychological safety lens. Asian Bus Manag https://doi.org/10.1057/s41291-020-00137-9

Hobfoll SE (2001) The influence of culture, community, and the nested‐self in the stress process: advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl Psychol 50(3):337–421

Hobfoll SE (2011) Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. J Occup Organ Psychol 84(1):116–122

Hu J, Liden RC (2011) Antecedents of team potency and team effectiveness: an examination of goal and process clarity and servant leadership. J Appl Psychol 96(4):851

Hu J, Xiong L, Zhang M, Chen C (2023) The mobilization of employees’ psychological resources: how servant leadership motivates pro-customer deviance. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 35(1):115–136

Huang C, Wu X, Wang X, He T, Jiang F, Yu J (2021) Exploring the relationships between achievement goals, community identification and online collaborative reflection. Educ Technol Soc 24(3):210–223

Imam H, Sahi A, Farasat M (2023) The roles of supervisor support, employee engagement and internal communication in performance: a social exchange perspective. Corp Commun Int J 28(3):489–505

Inamdar T (2021) Exploring Strategies to Improve the Success of Strategic Change Implementation at a Telco Company: The University of Liverpool (United Kingdom)

Irshad M, Naqvi SMMR (2023) Impact of team voice on employee voice behavior: role of felt obligation for constructive change and supervisor expectations for voice. Paper presented at the Evidence-based HRM: a Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship

Joseph EE, Winston BE (2005) A correlation of servant leadership, leader trust, and organizational trust. Leadersh Organ Develop J 26(1):6–22

Keegan A, Ringhofer C, Huemann M (2018) Human resource management and project based organizing: fertile ground, missed opportunities and prospects for closer connections. Int J Proj Manag 36(1):121–133

Kelemen TK, Matthews SH, Matthews MJ, Henry SE (2023) Humble leadership: a review and synthesis of leader expressed humility. J Organ Behav 44(2):202–224

Khan J, Jaafar M, Mubarak N, Khan AK (2024) Employee mindfulness, innovative work behaviour, and IT project success: the role of inclusive leadership. Inf Technol Manag 25(2):145–159

Khan MM, Mubarik MS, Ahmed SS, Islam T, Khan E (2022) The contagious servant leadership: exploring the role of servant leadership in leading employees to servant colleagueship. Leadersh Organ Dev J 43(6):847–861

Khan MM, Mubarik MS, Islam T, Rehman A, Ahmed SS, Khan E, Sohail F (2022) How servant leadership triggers innovative work behavior: exploring the sequential mediating role of psychological empowerment and job crafting. Eur J Innov Manag 25(4):1037–1055

Khattak MN, O’Connor P (2020) The interplay between servant leadership and organizational politics. Personnel Rev 50(3):985–1002

Kim JK, LePine JA, Zhang Z, Baer MD (2021) Sticking out versus fitting in: a social context perspective of ingratiation and its effect on social exchange quality with supervisors and teammates. J Appl Psychol 107(1):95–108

Kumar N, Jin Y, Liu Z (2024) The nexus between servant leadership and employee’s creative deviance for creativity inside learning and performance goal-oriented organizations. Manag Decis 62(4):1117–1137

Lawler EJ (2001) An affect theory of social exchange. Am J Sociol 107(2):321–352

Le Blanc PM, González-Romá V (2012) A team level investigation of the relationship between Leader–Member Exchange (LMX) differentiation, and commitment and performance. Leadersh Q 23(3):534–544

Lei S, Zhang Y, Cheah KS (2023) Mediation of work-family support and affective commitment between family supportive supervisor behaviour and workplace deviance. Heliyon 9(11) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21509

Liang J, Farh CI, Farh J-L (2012) Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: a two-wave examination. Acad Manag J 55(1):71–92

Liden RC, Wayne SJ, Liao C, Meuser JD (2014) Servant leadership and serving culture: influence on individual and unit performance. Acad Manag J 57(5):1434–1452

Liden RC, Wayne SJ, Zhao H, Henderson D (2008) Servant leadership: development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. Leadersh Q 19(2):161–177

López-Cabarcos MÁ, Vázquez-Rodríguez P, Quiñoá-Piñeiro LM (2022) An approach to employees’ job performance through work environmental variables and leadership behaviours. J Bus Res 140:361–369

Lorinkova NM, Perry SJ (2017) When is empowerment effective? The role of leader-leader exchange in empowering leadership, cynicism, and time theft. J Manag 43(5):1631–1654

Ludwikowska K, Zakkariya K, Aboobaker N (2024) Academic leadership and job performance: the effects of organizational citizenship behavior and informal institutional leadership. Asian Educ Develop Stud https://doi.org/10.1108/AEDS-04-2024-0074

Luu TT (2023) Translating responsible leadership into team customer relationship performance in the tourism context: the role of collective job crafting. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 35(5):1620–1649

Lv WQ, Shen LC, Tsai C-HK, Su C-HJ, Kim HJ, Chen M-H (2022) Servant leadership elevates supervisor-subordinate guanxi_ an investigation of psychological safety and organizational identification. Int J Hosp Manag 101:103114

Ma Y, Bennett D (2021) The relationship between higher education students’ perceived employability, academic engagement and stress among students in China. Education+ Training 63(5):744–762

Meuser JD, Smallfield J (2023) Servant leadership: the missing community component. Bus Horiz 66(2):251–264

Mishra SS, Hassen MH (2023) Servant leadership and employee’s job performance: the role of public service motivation in Ethiopian public sector organizations. Int J Public Leadersh 19(1):64–80

Mohammad SS, Nazir NA, Mufti S (2023) Employee voice: a systematic literature review. FIIB Bus Rev https://doi.org/10.1177/23197145231153926

Morrison EW (2023) Employee voice and silence: taking stock a decade later. Ann Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 10 https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-054654

Nauman S, Bhatti SH, Imam H, Khan MS (2022) How servant leadership drives project team performance through collaborative culture and knowledge sharing. Proj Manag J 53(1):17–32

Ng TW, Feldman DC (2012) Employee voice behavior: a meta‐analytic test of the conservation of resources framework. J Organ Behav 33(2):216–234

O’brien RM (2007) A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual Quant 41:673–690

Oladinrin OT, Ho CM-F (2016) Embeddedness of codes of ethics in construction organizations. Eng Constr Archit Manag 23(1):75–91

Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K (2015) Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res 42:533–544

Panaccio A, Henderson DJ, Liden RC, Wayne SJ, Cao X (2015) Toward an understanding of when and why servant leadership accounts for employee extra-role behaviors. J Bus Psychol 30(4):657–675

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP (2012) Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu Rev Psychol 63:539–569

Preacher KJ, Zyphur MJ, Zhang Z (2010) A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychol Methods 15(3):209

Quade M, McLarty BD, Bonner JM (2020) The influence of supervisor bottom-line mentality and employee bottom-line mentality on leader-member exchange and subsequent employee performance. Hum Relat 73(8):1157–1181

Robertson S, Williams T (2006) Understanding project failure: using cognitive mapping in an insurance project. Proj Manag J 37(4):55–71

Ruiz‐Palomino P, Linuesa‐Langreo J, Elche D (2023) Team‐level servant leadership and team performance: the mediating roles of organizational citizenship behavior and internal social capital. Bus Ethics Environ Responsib 32:127–144

Sherf EN, Parke MR, Isaakyan S (2021) Distinguishing voice and silence at work: unique relationships with perceived impact, psychological safety, and burnout. Acad Manag J 64(1):114–148

Shipton H, Kougiannou N, Do H, Minbashian A, Pautz N, King D (2024) Organisational voice and employee‐focused voice: two distinct voice forms and their effects on burnout and innovative behavior. Hum Resour Manag J 34(1):177–196

Song Y, Tian Q.-t., Kwan HK (2021) Servant leadership and employee voice: a moderated mediation. J Manag Psychol 37(1):1–14

Song Y, Tian Q-t, Kwan HK (2022) Servant leadership and employee voice: a moderated mediation. J Manag Psychol 37(1):1–14

Sousa M, van Dierendonck D (2021) Serving the need of people: the case for servant leadership against populism. J Change Manag 21(2):222–241

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS, Ullman JB (2007) Using multivariate statistics (Vol. 5): Pearson Boston, MA

Tangirala S, Green SG, Ramanujam R (2007) In the shadow of the boss’s boss: effects of supervisors’ upward exchange relationships on employees. J Appl Psychol 92(2):309

Tuan LT (2021) Effects of environmentally-specific servant leadership on green performance via green climate and green crafting. Asia Pac J Manag 38(3):925–953

Van Dierendonck D, Sousa M, Gunnarsdóttir S, Bobbio A, Hakanen J, Pircher Verdorfer A, Rodriguez-Carvajal R (2017) The cross-cultural invariance of the servant leadership survey: a comparative study across eight countries. Adm Sci 7(2):8

Van Dyne L, LePine JA (1998) Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: evidence of construct and predictive validity. Acad Manag J 41(1):108–119

Varela JA, Bande B, Del Rio M, Jaramillo F (2019) Servant leadership, proactive work behavior, and performance overall rating: testing a multilevel model of moderated mediation. J Bus -to-Bus Mark 26(2):177–195

Williams LJ, Anderson SE (1991) Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J Manag 17(3):601–617

Wu F, Zhou Q (2024) How and when servant leadership fosters employee voice behavior: evidence from Chinese local governments. Int Public Manag J https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2024.2303163

Yan A, Xiao Y (2016) Servant leadership and employee voice behavior: a cross-level investigation in China. SpringerPlus 5(1):1–11

Ye S, Yao K, Xue J (2023) Leveraging empowering leadership to improve employees’ improvisational behavior: the role of promotion focus and willingness to take risks. Psychol Rep https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941231172707

Yıkılmaz İ, Sürücü L (2023) Leader–member exchange as a mediator of the relationship between authentic leadership and employee creativity. J Manag Organ 29(1):159–172

Zada M, Khan J, Saeed I, Zada S, Jun ZY (2023) Linking public leadership with project management effectiveness: mediating role of goal clarity and moderating role of top management support. Heliyon 13:888761

Zada M, Saeed I, Khan J, Zada S (2024) Navigating post-pandemic challenges through institutional research networks and talent management. Human Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1–11

Zada S, Khan J, Saeed I, Jun ZY, Vega-Muñoz A, Contreras-Barraza N (2022) Servant leadership behavior at workplace and knowledge hoarding: a moderation mediation examination. Front Psychol 13:888761

Zarei M, Supphellen M, Bagozzi RP (2022) Servant leadership in marketing: a critical review and a model of creativity-effects. J Bus Res 153:172–184

Zhang K, Goetz T, Chen F, Sverdlik A (2021) Angry women are more trusting: the differential effects of perceived social distance on trust behavior. Front Psychol 2857

Zhang Y, Zhao J, Qin J (2024) Research on mechanism of servant leadership on employees’ customer-oriented deviance: the mediating role of psychological security and the moderating role of error management climate. Asia Pac J Market Logist https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-09-2023-0865

Zhang Y, Zheng Y, Zhang L, Xu S, Liu X, Chen W (2021) A meta-analytic review of the consequences of servant leadership: the moderating roles of cultural factors. Asia Pac J Manag 38(1):371–400

Zhou L, Wang M, Chen G, Shi J (2012) Supervisors’ upward exchange relationships and subordinate outcomes: testing the multilevel mediation role of empowerment. J Appl Psychol 97(3):668

Zhou W, Wang T, Zhu J, Tao Y, Liu Q (2024) Perceived working conditions and employee performance in the coal mining sector of China: a job demands-resources perspective. Chin Manag Stud https://doi.org/10.1108/CMS-06-2023-0292

Zou W-C, Tian Q, Liu J (2015) Servant leadership, social exchange relationships, and follower’s helping behavior: positive reciprocity belief matters. Int J Hosp Manag 51:147–156

Acknowledgements

The first author extends heartfelt gratitude to Hanjiang Normal University Shiyan China and the Department of Business Administration, Faculty of Management Sciences, Ilma University, Karachi, Pakistan, for its invaluable support and resources, which played a pivotal role in completing this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The author sought and received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Economics and Management at Hanjiang Normal University, China, with approval number 2023REC002, and from the Research Ethics Committee of the Department of Business Administration, Faculty of Management Sciences, Ilma University, Karachi, Pakistan, with reference DBA-FM-0311/10/2024. This study was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were accessed with the support of the HR department in Pakistan’s information technology sector. Participants received comprehensive information about the study’s purpose and procedures. Confidentiality and privacy were strictly maintained, and participation was entirely voluntary. Using a time-lagged data collection approach, we gathered data from 392 respondents in this sector.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zada, M., Khan, J., Saeed, I. et al. Examining the nexus between servant leadership and employee task performance: the moderation mediation model. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1559 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04052-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04052-8