Abstract

The central aim of this research is to investigate the underlying mechanism between parental involvement and externalizing problem behaviors in Chinese rural adolescents. While earlier studies have investigated this link, the pivotal influences of peer relationships, mental health, and problematic social media use have not been thoroughly addressed. In this analysis, 3157 rural Chinese adolescents aged 13–19 years participated by filling out an anonymous self-report questionnaire. Our findings revealed that: (1) parental involvement acted as a protective factor against the emergence of externalizing problem behaviors; (2) both peer relationships and mental health served as mediators in the connection between parental involvement and externalizing problem behaviors; (3) parental involvement indirectly influenced externalizing problem behaviors through the sequential mediation of peer relationships and mental health; and (4) as problematic social media use escalated among rural adolescents, the protective impact of parental involvement on externalizing problem behaviors weakened. Building on these findings, the study has identified possible causes and suggested practical interventions to mitigate externalizing problem behaviors among rural adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Problem behavior refers to deviant actions exhibited by individuals that impedes their integration into societal frameworks (Achenbach et al. 1987). Such behavior includes internalizing disorders, such as anxiety and depression (Lee and Hankin 2009), as well as externalizing behaviors like absenteeism, physical altercations, substance misuse, and aggression (Herrenkohl et al. 2009; Petersen et al. 2015; Brock and Kochanska 2016). Prior studies have indicated that behaviors such as smoking and alcohol consumption among Chinese students in grades 7 through 12 have prevalence rates ranging from 5.24% to 29.15%, with an annual increase observed (Guo et al. 2019; Zhao et al. 2022). A recent national survey revealed a detection rate of 35.1% for externalizing problematic behaviors in adolescents (Chi and Cui 2020). Extensive empirical research supports that such behaviors can lead to immediate and long-term negative consequences on adolescents’ physical health, functionality, and overall well-being. These effects include impaired brain function and structure (Lubman et al. 2015), academic difficulties (Park and Kim 2015), psychological issues like anxiety, depression, or addictive behaviors (Ferguson 2015), and even engagement in criminal activities (Harris-McKoy and Cui 2013).

Adolescents’ problematic behavior is significantly influenced by parental involvement, defined as the active participation and engagement of parents in their child’s educational processes and school-related activities (Jaiswal 2017; Goncy and van Dulmen 2010; Hindelang et al. 2001). This socio-cultural phenomenon, deeply rooted in various communities, has been recognized as fundamental to child development (Gómez et al. 2017; Goodall and Montgomery 2023; Berg et al. 2011). As proposed by self-determination theory, an individual’s actions are profoundly shaped by the socio-environmental conditions surrounding them (Reeve et al. 2018). This concept aligns with the tenets of social cognitive theory, which emphasize the complex interaction among external contextual factors, internal individual traits, and both past and present behaviors in shaping an individual’s behaviors (Bandura 2001). A significant legislative development occurred in 2022 with the enactment of China’s Family Education Promotion Law (Acar et al. 2021), symbolizing the nation’s acknowledgment of family education not only as a private concern but also as a critical factor influencing its future direction.

Numerous studies have extensively examined the direct influence of parental involvement on adolescent externalizing problem behaviors (Aho et al. 2018; Gómez et al. 2017). However, there remains a significant lack of comprehensive analyses regarding the specific mechanisms through which parental involvement impacts such behaviors. Significantly, these behaviors are more commonly observed among rural adolescents in China than among those in urban areas, highlighting a pronounced disparity in the identification rates of problem behaviors (Chen et al. 2022).

Rural adolescents in China face unique challenges that distinguish their experiences from those of their urban counterparts. These challenges involve limited access to resources, educational disparities, and differing socio-cultural dynamics. In rural areas, the scarcity of educational facilities, trained teachers, and extracurricular opportunities can greatly impact the development and future prospects of adolescents (Ma et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2020). Moreover, many rural families have lower socio-economic status, which further worsens these issues, as they have less access to supplementary educational materials and activities compared to urban families (Song 2023). In this context, parental involvement becomes especially important, as it can provide essential emotional support and guidance that might otherwise be lacking due to systemic deficiencies. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate and clarify the protective factors at both environmental and individual levels that could foster positive behavioral outcomes in this demographic. Moreover, there is a scarcity of empirical studies focused specifically on rural adolescents in China. This gap underscores the urgent need for detailed studies to elucidate the relationship between parental involvement and externalizing problem behaviors among rural Chinese adolescents.

Literature review

The association between parental involvement and adolescent externalizing problem behaviors

According to Social Control Theory, there exists an inherent inclination toward problematic behaviors in individuals (Hirschi 1969). This theory, however, also emphasizes that the formation of social bonds, particularly within the family context, can significantly mitigate these behaviors (Church et al. 2012). Such bonds are emotionally based, evolving through social interactions and integrating into the individual’s personality (Hirschi 1969). Within this framework, attachment and commitment emerge as pivotal components. Attachment is characterized by a person’s emotional reliance on others or social groups (Hirschi 1969), with the intensity of this reliance influencing their sensitivity to the expectations of these entities (Shoemaker 2018). Notably, for adolescents, parents frequently represent the primary figures of emotional attachment. Elevated levels of parental involvement, encompassing support, care, and expectations, are linked to a reduction in externalizing behaviors in adolescents. Commitment, conversely, relates to an individual’s dedication to life goals (Hirschi 1969). This facet implies that adolescents, when contemplating aggressive or problematic actions, must weigh these against the potential repercussions on their personal aspirations. Parental expectations can play a critical role in shaping these aspirations, thereby indirectly curbing tendencies toward externalizing behaviors.

Empirical research has substantiated the assertions of Social Control Theory. Parental involvement has been repeatedly identified as a key determinant in influencing adolescent behavior, particularly in externalizing tendencies. Active parental involvement has been demonstrated to decrease the likelihood of issues such as children’s online addiction (Gómez et al. 2017; Siomos et al. 2012). Additionally, weakened parent–child communication has been correlated with increased disciplinary issues (Lee and Song 2012; Pengpid and Peltzer 2016). Various dimensions of parental involvement, including shared activities (Desha et al. 2011; Zhao et al. 2015), supervisory roles (Liu et al. 2022), and educational aspirations (Simons-Morton 2004), have been explored, with findings aligning with the broader implications of the theory.

Taking the above into account, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Increased parental involvement may reduce externalizing problem behaviors in rural adolescents.

Peer relationship as a mediator

Santrock (1988) defined peers as individuals who are of a comparable age, undergoing similar educational phases, and possessing equivalent levels of maturity. Berk (1997) elucidated that peer relationships encompass interactions between individuals of equal status and level, sharing mutual abilities and objectives. Bronfenbrenner (1992) and Eccles and Roeser (2011) highlight that for adolescents, schools serve as a critical microsystem, second only to the family. The role of peer relationships within schools is significant in the developmental journey of adolescents (Giordano 2003; Mitic et al. 2021). This aspect holds particular relevance for Chinese adolescents, for whom school is not just a learning environment but also a living space. Ren et al. (2011) and Zhang et al. (2013) assert that the impact of peer interactions in the developmental process of adolescents is a factor that warrants considerable attention.

Peer relationships in adolescence not only mirror the level of closeness and accord with others but also constitute a vital aspect of socialization and a crucial measure of social adaptability (Qian et al. 2021). The nature of these relationships significantly influences adolescents’ behavioral development (Hartup 1992). They serve as sensitive indicators for identifying problematic behaviors, greatly impacting their emergence (Fowler et al. 2015). Adolescents within peer groups exhibit similarities in dealing with adaptive challenges, including both externalized and internalized behavioral issues (Fortuin et al. 2015; Kiesner et al. 2003). Enhanced peer acceptance correlates with increased adolescent inclination to adopt prosocial behaviors from their peers (Barry and Wentzel 2006). Therefore, adolescents with high-quality peer relationships are more likely to exhibit prosocial behaviors (Carlo et al. 2012) and fewer behavioral problems (Bao et al. 2015). Conversely, deficient peer relationships can lead to problematic behaviors, including aggression and disciplinary breaches (Palmqvist and Santavirta 2006). Intervening in adolescent peer relationships can foster the development of prosocial behaviors (Yang et al. 2015).

Ecological Systems Theory elucidates the multifaceted interactions within a child’s environment, providing a framework to comprehend how peer relationships serve as an intermediary in the influence of parental involvement on children’s behavior (Bronfenbrenner 1999). According to this theory, every component in a young individual’s surroundings exerts influence. Consequently, extensive parental engagement not only directly affects the child but also indirectly shapes their choice of peers and the subsequent influence these peers have (Perron 2017). Parents can influence peer relationships indirectly through the parent–child relationship, providing children with a sense of security. Delgado et al. (2022) revealed that a secure attachment with parents is a key predictor and promoter of forming affective relationships among peers. These peer relationships are characterized by essential elements such as effective communication, support, intimacy, trust, and quality, all of which are significantly influenced by the nature of the adolescent’s attachment to their parents. This underscores the vital role of secure parental attachment in shaping healthy and supportive peer relationships during adolescence.

Responsive and sensitive parenting communicates to children that social relationships are supportive, trustworthy, and caring, which may carry over into child–peer relationships. Additionally, parents can serve as designers, mediators, and advisors in their children’s peer relationships by choosing environments, scheduling playdates, and discussing relationship difficulties with their children (Ladd and Kochenderfer-Ladd 2019).

Accordingly, we suggest the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Peer relationship mediates the relationship between parental involvement and rural adolescent externalizing problem behaviors.

Mental health as a mediator

Mental health refers to a state of well-being in which an individual realizes their own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to their community (Taylor and Brown 1994). It encompasses emotional, psychological, and social well-being, influencing cognition, perception, and behavior (Donaldson-Feilder and Bond 2004). These aspects of mental health affect daily functioning and overall life satisfaction, positioning mental health as a crucial component of public health (Huebner et al. 2014). Jones et al. (2013) have observed that adolescents are less likely to engage in problem behaviors when they exhibit strong and resilient mental health. A body of research, including studies by Li et al. (2021), consistently demonstrates a correlation between problematic behaviors and deteriorating mental health. Wu (2000) elucidates the role of mental health in shaping adolescent behavior, highlighting poor mental health as a significant precipitant of such issues. Similarly, Chen and Zhong (2012) report that negative mental health conditions characterized by stress, depression, or low self-esteem can impact the occurrence of problematic behaviors among adolescents, such as smoking, drinking, and involvement in physical conflicts.

Parental influence on adolescent mental health is well established. The nature of parental involvement can either help adolescents cope with stressors or, negatively, be a cause of such stressors (Baig et al. 2021). On the one hand, low levels of parental involvement are associated with unfavorable mental health outcomes. A systematic review highlighted that factors such as less parental warmth, more inter-parental conflict, over-involvement, and aversiveness increase the risk for depression and anxiety disorders in adolescents (Yap et al. 2014). On the other hand, a study conducted in middle schools in Georgia, USA, found that higher levels of perceived parental involvement were associated with fewer mental health difficulties and suicidal thoughts and behaviors among students. Research focusing on the role of parental involvement in academic socialization at age 16 demonstrated a positive impact on the life course development of internalized mental health symptoms (Westerlund et al. 2015).

Moreover, mental health plays a significant intermediary role in the relationship between parental involvement and the manifestation of problematic behaviors (Mo et al. 2021). Attachment Theory emphasizes the impact of the emotional bond formed between a child and their parents on the child’s psychological development and behavioral patterns (Flykt et al. 2021). High levels of parental involvement and support are typically correlated with enhanced mental health in children, as suggested by Cooke et al. (2019). This positive mental state facilitates sound decision-making and adaptive behaviors in children (Moretti and Peled 2004). Conversely, a weak emotional bond with parents or limited parental involvement may precipitate mental health issues in children, potentially leading to maladaptive or problematic behaviors (Schneider et al. 2001). Therefore, mental health acts as a crucial channel: it can transmit the positive impacts of effective parenting on desirable adolescent behaviors, or conversely, mediate the transition from inadequate parental engagement to adverse behavioral outcomes in children (Wilkinson 2004).

Considering the aforementioned reasoning, we put forward the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Mental health mediates the relationship between parental involvement and rural adolescent externalizing problem behaviors.

The chain mediating role of peer relationship and mental health

Social Learning Theory offers a framework for understanding the influence of peer relationships on adolescent mental health (Bandura 2006). This theory posits that observational learning, particularly from individuals deemed significant, plays a crucial role in behavioral acquisition. During adolescence, peers often serve as a primary reference group. Adolescents are inclined to observe, assimilate, and emulate the attitudes and behaviors of their peers. Therefore, when these peer influences are positive and embody healthy behaviors, there can be a beneficial impact on an adolescent’s mental health, fostering feelings of well-being and self-confidence (Huston 2018). Conversely, being around peers with negative attitudes or unhealthy behaviors can have harmful effects, potentially leading to increased stress, anxiety, or other mental health challenges (Smith 2021). In essence, the nature of an adolescent’s peer group exerts a substantial influence on their mental health, shaping their emotional state and perception of the world.

Drawing from the aforementioned discourse, it can be deduced that a nexus exists between parental involvement and peer affiliations, as well as between peer affiliations and mental health, further extending to a connection between mental health and externalizing problem behaviors. Based on these theoretical and empirical findings, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Peer relationship and mental health exhibit a chain mediating effect in the relationship between parental involvement and rural adolescent externalizing problem behaviors.

Problematic social media use may impact the association between parental involvement and externalizing problem behavior

Problematic social media use is a phenomenon characterized by excessive and compulsive engagement with social media platforms, which negatively impacts users’ mental health, well-being, and daily functioning (Shannon et al. 2022). This form of digital interaction extends beyond normal usage patterns, entering the realm of addiction-like behaviors where individuals experience a loss of control, preoccupation with social media, and neglect of personal life responsibilities (Savci et al. 2020). Problematic social media use is increasingly recognized as a significant mental health concern, particularly among adolescents, due to its implications for psychological distress, reduced academic performance, and impaired social interactions (Boniel-Nissim et al. 2022).

The Media Practice Model, developed by Steele and Brown (1995), offers a profound theoretical framework for understanding how problematic social media use moderates the relationship between parental involvement and adolescent externalizing behaviors (Anyiwo et al. 2022; Padilla-Walker et al. 2020). This model highlights that adolescents actively select, engage with, and interpret media based on their personal preferences, developmental needs, and social contexts, suggesting that media usage is deeply integrated with an individual’s identity, social interactions, and personal growth. Within this framework, problematic social media use can be seen as an outcome of adolescents’ efforts to fulfill these needs, albeit maladaptively. The model delineates three crucial processes: selection, interaction, and application. Adolescents might prefer social media interactions over family interactions, diminishing the influence of parental guidance (Coyne et al. 2018). As active participants in social media, they are exposed to and may adopt peer norms that conflict with parental values, particularly those that encourage externalizing behaviors such as aggression and delinquency.

Empirical studies have demonstrated that high levels of problematic social media use can undermine the protective effects of parental involvement, thereby contributing to an increase in adolescent externalizing behaviors, such as aggression and rule-breaking (Ruiz-Hernández et al. 2018; McDaniel and Radesky, 2020). The immersive and engaging characteristics of social media may overshadow parental influence (Lin et al. 2019; Sobel, 2019). As the virtual environments provided by platforms become increasingly enveloping, the traditional boundaries and roles of parental guidance can be challenged (Fiani et al. 2024; Canet and Pérez-Escolar 2023). Additionally, Vannucci and McCauley Ohannessian (2019) demonstrated problematic social media use exacerbates the impact of diminished parental involvement on the prevalence of externalizing behaviors. Their research highlights that adolescents deeply engaged in problematic social media interactions are more likely to adopt behaviors modeled by online peers, frequently encompassing externalizing traits such as aggression and substance use.

Thus, based on these premises, the following hypothesis is posited:

Hypothesis 5 (H5). Problematic social media use decreases the protective role of parental involvement on externalizing problem behaviors among rural adolescents.

The present study

Given the multifaceted influences on adolescent externalizing problem behaviors, which include school, family, and individual factors, addressing and preventing these behaviors from a single-domain perspective presents significant challenges. The findings discussed herein indicate that parental involvement is a crucial predictor of externalizing problem behaviors, with peer relationships and mental health potentially acting as mediators in this relationship. Furthermore, the impact of parental involvement on externalizing behaviors might depend on the level of problematic social media use; higher levels of such use could moderate this relationship. This study enhances the development of effective intervention strategies for rural adolescents’ externalizing problem behaviors, a subject that has been relatively underexplored in existing research. To the best of our knowledge, this research is the first to examine the collective effects of parental involvement, peer relationships, mental health, and problematic social media use on externalizing problem behaviors among rural adolescents. The theoretical framework of this study incorporates Social Control Theory, Ecological Systems Theory, Attachment Theory, Social Learning Theory, and the Media Practice Model, thereby broadening the scope of existing literature on parental involvement and externalizing problem behaviors.

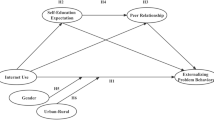

In line with our research goals, we propose hypotheses H1–H5, as depicted in Fig. 1.

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Increased parental involvement may reduce externalizing problem behaviors in rural adolescents. Hypothesis 2 (H2). Peer relationship mediates the relationship between parental involvement and rural adolescent externalizing problem behaviors. Hypothesis 3 (H3). Mental health mediates the relationship between parental involvement and rural adolescent externalizing problem behaviors. Hypothesis 4 (H4). Peer relationship and mental health exhibit a chain mediating effect in the relationship between parental involvement and rural adolescent externalizing problem behaviors. Hypothesis 5 (H5). Problematic social media use decreases the protective role of parental involvement on externalizing problem behaviors among rural adolescents.

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Increased parental involvement may reduce externalizing problem behaviors in rural adolescents.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Peer relationship mediates the relationship between parental involvement and rural adolescent externalizing problem behaviors.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Mental health mediates the relationship between parental involvement and rural adolescent externalizing problem behaviors.

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Peer relationship and mental health exhibit a chain mediating effect in the relationship between parental involvement and rural adolescent externalizing problem behaviors.

Hypothesis 5 (H5). Problematic social media use decreases the protective role of parental involvement on externalizing problem behaviors among rural adolescents.

Materials and methods

Participants

The study recruited a sample of 3157 rural adolescents from traditional two-parent households from six counties across the provinces of Liaoning, Shandong, and Guangxi in China. The sampling strategy was meticulously designed to ensure representativeness, employing a combination of stratified and random cluster sampling methods. Initially, stratified sampling was used to categorize schools based on geographic location and socio-economic status, ensuring a comprehensive representation of rural regions within each province. Following this stratification, random cluster sampling was employed to select six junior high schools and six senior high schools from each region. Within these schools, specific classes were randomly chosen, and households of students from these classes were then sampled. This methodological approach was intended to capture a broad range of socio-economic conditions and educational contexts specific to rural areas, thereby enhancing the generalizability and relevance of the study’s findings.

Data gathering commenced in early 2024. Institutional permissions were secured from the involved schools, with participants and their guardians providing informed consent in written form. To preserve anonymity and confidentiality, the consent forms were designed not to include signatures or names of the participants. It was clearly communicated to the participants that their involvement was voluntary, and they retained the right to discontinue participation at any stage. During school hours, trained research assistants monitored the students as they independently filled out paper-based questionnaires. Returned questionnaires with missing pages or incomplete responses to more than three items were excluded. The intact questionnaires were securely sealed in envelopes. As an incentive, a token gift, such as a pen or card, was offered to participants.

Following a thorough examination of the data, 191 questionnaires were rejected due to missing or incomplete information. The resulting dataset consisted of 3157 meticulously examined questionnaires, reflecting an impressive response rate of 94%. The age range of the participants was 13–19 years (M = 15.507, SD = 1.655), with boys constituting 50.2% (N = 1585) and girls 49.8% (N = 1572) of the sample. A total of 310 participants displayed no signs of externalizing problem behaviors, indicating an incidence rate of 90.2% within the sample. The research ethics committee of the university where the lead author is affiliated approved all methodologies used in this study.

Measures

Parental involvement

This study assessed parental involvement using the Chinese version of the Parental Involvement Behavior Questionnaire, developed by Wu et al. (2018). This instrument, widely adopted in scholarly investigations (e.g., Yang et al. 2021), probes four distinct dimensions of paternal and maternal roles: emotional leisure, disciplinary guidance, academic assistance, and caregiving. Each dimension is represented by 22 specific items, including examples such as “Dad supervises me doing my homework.” Responses to all items were elicited on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always), where higher scores indicate more intensive parental involvement. The Cronbach’s alpha of this sample was 0.983.

Externalizing problem behaviors

The evaluation of externalizing problem behaviors in adolescents utilized the Youth Self-Report (YSR; Achenbach 1991a, 1991b), a psychometrically robust instrument whose validity and reliability have been established in prior research (Zhu et al. 2023; Feng and Lan 2020). The YSR Externalizing Problem Behavior Scale is divided into two distinct subscales: Aggressive Behavior and Rule-Breaking Behavior, each comprising 15 items, thus forming a total of 30 evaluative items. An example of such an item is “I destroy my own belongings.” Response options were formatted on a 3-point Likert scale, where 1 represents “not true”, 2 “somewhat true”, and 3 “very true”. The overall score was calculated by averaging the responses across all items, with higher scores indicating more significant externalizing problem behaviors in early adolescence. The Cronbach’s alpha of this sample was 0.926.

Peer relationships

Peer relationships were assessed using the 8-item PROMIS Pediatric Peer Relationships Scale (Dewalt et al. 2013), which has shown good psychometric properties for assessing Chinese adolescents (Zhu et al. 2023; Huang et al. 2021). Sample items from the scale include “I was able to count on my friends” and “I felt accepted by other kids my age.” Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (almost always). The mean score of all items was calculated, with higher scores indicating better peer relationships. The reliability of this measure was robust, as evidenced by a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.888.

Mental health

Mental health assessments were conducted using the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12; McDowell 2006), a tool frequently employed in studies involving Chinese adolescents (Yang and Zhu 2023; Ren and Zhu 2022). The questionnaire is structured with an equal distribution of positive (e.g., “able to concentrate on whatever I do”) and negative (e.g., “insomnia due to anxiety”) items. Responses were gathered using a 4-point Likert scale, where 1 indicates “never” and 4 denotes “often”. Items reflecting negative mental health were reverse-scored to compute an aggregate mean score, with higher scores reflecting superior mental health. This instrument demonstrated robust internal consistency, evidenced by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.917.

Problematic social media use

To evaluate problematic social media use, the study utilized the Social Media Addiction Questionnaire developed by Hawi and Samaha (2017), which is known for its solid psychometric properties in assessing Chinese adolescents (Shen et al. 2020). This instrument comprises an 8-item self-administered questionnaire, with items such as “the thought of not being able to access social media makes me feel distressed.” Responses were captured on a 7-point scale, where 1 represents “strongly disagree” and 7 represents “strongly agree”. Higher scores on this scale are indicative of more severe levels of problematic social media use. The questionnaire has shown excellent internal consistency, as indicated by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.958.

Control variables, as informed by recent literature (Yang et al. 2023; Wang et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2021), were categorized into two main groups: family and individual characteristics.

Family characteristics

We considered five family characteristics: the extent of the family’s library, the educational backgrounds of both parents, their educational expectations for their children, and the family’s economic conditions. To evaluate the size of the family’s book collection, respondents were asked, “Does your household possess a considerable number of books (excluding textbooks and periodicals)?” Answers were classified into five distinct categories, with a scoring system that ranged from 1 (few) to 5 (many). Questions regarding parental educational attainment, specifically “The educational attainment of your father” and “The educational attainment of your mother,” were scored on a scale from 1 (no formal education) to 9 (master’s degree or higher), with intermediate levels reflecting ascending educational qualifications from primary school to a bachelor’s degree. Parental aspirations for their children’s education were captured by the question, “To what educational level do your parents aspire for you?” with responses categorized into 9 levels, from 1 (advocating for immediate school withdrawal) to 9 (aiming for a doctoral degree). The family’s economic status was assessed through the question, “How would you describe your family’s current financial situation?” with responses scored from 1 (severe financial hardship) to 5 (substantial economic prosperity).

Individual characteristics

We considered five individual characteristics, including gender, nationality, age, type of household registration (urban or rural), and physical health condition (see Table 1).

Control variables were included in the analysis to examine the robustness of the OLS regression, moderation, and mediation effects. However, since these variables are not the main focus of the current study, we will not provide an interpretation of them.

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the questionnaires, we implemented a rigorous translation and back-translation. First, bilingual experts, fluent in both English and Chinese and knowledgeable about the subject matter, translated each original English questionnaire into Chinese. This step ensured that the translations were linguistically accurate and culturally sensitive, capturing the nuances of the original content. Subsequently, independent bilingual experts, who had not seen the original questionnaires, performed back-translations of the Chinese versions into English. This step was crucial for identifying any discrepancies or shifts in meaning that might have arisen during the initial translation. By involving separate individuals for the back-translation, we minimized potential bias and ensured a fresh, objective perspective on the translated material. Following these steps, a pilot test was conducted with 30 Chinese high school students to further validate the clarity and accuracy of the translated questionnaires. Participants provided feedback on the comprehensibility and relevance of the questionnaire items. Based on this feedback, necessary adjustments were made to enhance the clarity and accuracy of the translated versions. This comprehensive translation process ensured that all translated questionnaires maintained their original meaning and integrity, thereby supporting the study’s overall validity and reliability.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS Version 23.0, STATA Version 16.0, and MPLUS Version 8.3. Initially, Harman’s single-factor method was applied to ascertain the presence of common method bias. Subsequently, descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were utilized to explore the relationships between key variables. In analyzing the influence of parental involvement on adolescent externalizing problem behaviors, a hierarchical approach was adopted in the OLS regression analyses to incrementally include influencing factors. Structural equation modeling was then employed to investigate a proposed chain mediation model. In this model, parental involvement was positioned as the predictor, with peer relationships and mental health serving as mediators, and adolescent externalizing problem behaviors as the outcome variable. Mediation was considered substantiated if the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the indirect effect excluded zero. To ascertain the significance of the indirect effects, bootstrapped CIs were computed from 5000 bootstrapped samples. Lastly, moderated analyses were conducted using the PROCESS 4.0 macro in SPSS, incorporating relevant covariates.

Results

Common method bias test

Harman’s single-factor test was employed to examine the presence of common method bias (Zhou et al. 2023). An exploratory factor analysis revealed 23 factors each with eigenvalues exceeding 1. The primary factor explained 29.700% of the total variance, which is under the often-referenced threshold of 40% that is considered critical for indicating significant common method bias. This result suggests that common method bias is unlikely to be a concern, allowing further analysis to proceed without this issue.

Correlation analysis of variables

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations (SDs), and Pearson correlation coefficients for the primary variables. The analysis revealed significant correlations among all principal variables. Specifically, externalizing problem behaviors exhibited negative correlations with parental involvement (r = −0.245, p < 0.001), peer relationships (r = −0.251, p < 0.001), and mental health (r = −0.390, p < 0.001), and a positive correlation with problematic social media use (r = 0.293, p < 0.001). In contrast, parental involvement demonstrated positive correlations with peer relationships (r = 0.306, p < 0.001) and mental health (r = 0.156, p < 0.001), and a negative correlation with problematic social media use (r = −0.570, p < 0.001). Furthermore, peer relationships exhibited positive correlations with mental health (r = 0.231, p < 0.001) and a negative correlation with problematic social media use (r = −0.101, p < 0.001), while mental health was negatively associated with problematic social media use (r = −0.196, p < 0.001).

OLS regression results

Table 3 shows that parental involvement has a positive effect on preventing the development of externalizing problem behaviors. Model (1) only included the independent variable of parental involvement. Model (2) introduced family characteristic variables based on Model (1). Finally, Model (3) introduced adolescent individual characteristic variables based on Model (2). In Models (1)–(3) of Table 3, the estimated coefficients for the parental involvement were −0.142 (p < 0.001), −0.105 (p < 0.001), and −0.094 (p < 0.001) respectively. These coefficients indicated that the parental involvement negatively predicted rural adolescent externalizing problem behaviors.

Mediation analysis

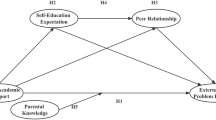

The analysis began by ascertaining the mean values for the examined variables and proceeded to develop a structural equation model (SEM). The resultant Comparative Fit Index and Tucker–Lewis Index both achieved scores of 1, whereas the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual recorded values of zero. These indicators generally denote that the research model utilized in this study exhibits some predictive validity. Consequently, a chain mediation model was examined, comprising three indirect effects: (1) peer relationship served as a mediator in the nexus between parental involvement and externalizing problem behaviors; (2) mental health mediated the association between parental involvement and externalizing problem behaviors; and (3) parental involvement indirectly influenced externalizing problem behaviors through the sequential mediation of peer relationship and mental health (Fig. 2).

The findings demonstrated that parental involvement and externalizing problem behaviors exhibited a significant and inverse relationship (β = −0.245, t = −14.663, p < 0.001). When controlling for various confounders, the direct effect of parental involvement on externalizing behaviors remained significant and negative (β = −0.154, t = −8.062, p < 0.001). Additionally, a positive and significant association was observed between parental involvement and peer relationships (β = 0.306, t = 17.233, p < 0.001), with peer relationships in turn showing a significant inverse correlation with externalizing problem behaviors (β = −0.126, t = −6.466, p < 0.001). Further, parental involvement correlated positively and significantly with mental health (β = 0.094, t = 4.982, p < 0.001), which notably exhibited a significant and negative effect on externalizing problem behaviors (β = −0.337, t = −18.394, p < 0.001). Moreover, a substantial and positive link between peer relationships and mental health was also established (β = 0.202, t = 10.655, p < 0.001).

Additionally, as delineated in Table 4, the total effect of parental involvement on externalizing problem behaviors was measured at −0.245 (SE = 0.019, 95% CI [−0.282, −0.208], p < 0.001), with a direct effect recorded at −0.154 (SE = 0.019, 95% CI [−0.192, −0.116], p < 0.001). Both effects were found to be statistically significant. The pathway from parental involvement through peer relationships to externalizing problem behaviors showed an indirect effect of −0.039 (SE = 0.006, 95% CI [−0.052, −0.027], p < 0.001), constituting 15.854% of the total effect (−0.246). Additionally, the indirect effect through the pathway from parental involvement to mental health, and subsequently to externalizing problem behaviors, was −0.032 (SE = 0.007, 95% CI [−0.045, −0.019], p < 0.001), representing 13.008% of the total effect. A further indirect effect of −0.021 (SE = 0.003, 95% CI [−0.026, −0.016], p < 0.001) was noted in the pathway incorporating both peer relationships and mental health, accounting for 8.537% of the total effect. The statistical significance of these three indirect effects is confirmed, as the Bootstrap 95% CIs do not include zero. The analysis indicates that the influence of parental involvement on externalizing problem behaviors is mediated significantly through the mechanisms of peer relationships and mental health, which act as substantial and positive partial mediators within this relationship.

Moderation analysis

Table 5 displays results that elucidate the moderating effect of problematic social media use on the relationship between parental involvement and externalizing problem behaviors. Initially, the regression coefficient for parental involvement was −0.036, achieving statistical significance at the 1% level (p < 0.01). Furthermore, the coefficient for the interaction term between parental involvement and problematic social media use was 0.014 which was significant at the 1% level (p < 0.01).

As depicted in Fig. 3, a detailed exploration of the moderating role was undertaken using a simple slopes analysis at conditions of low (−1 SD) and high (+1 SD) problematic social media use. The results of this analysis confirmed the significance of the moderating effect across all groups. Notably, the analysis revealed a more pronounced negative relationship between parental involvement and externalizing problem behaviors in individuals with lower levels of problematic social media use compared to those with higher levels, with a beta coefficient of −0.058 (p < 0.001).

Discussion

Parental involvement decreases the risk of externalizing problem behaviors in rural adolescents

The results of this study corroborate the initial hypothesis (H1), suggesting that parental involvement plays a vital role in reducing externalizing behavioral problems among rural adolescents. This observation is in line with the protective factor theory, which proposes that positive family interactions can shield youths from the development of adverse behaviors (Mihić et al. 2022). Notably, our findings concur with those of Sharma et al. (2019), who observed similar protective effects of parental engagement in a suburban adolescent cohort, thereby supporting the broad applicability of parental involvement as a moderating factor across varied demographic contexts.

However, unlike the findings of Sharma et al. (2019) indicating a lack of significant impact of parental involvement in urban areas, our study revealed that parental engagement plays a protective role in rural environments. This discrepancy may stem from distinct social dynamics and the availability of community resources in rural versus urban areas (Gu et al. 2024; Huang et al. 2015; Luo and Zhang 2017), emphasizing the necessity for context-specific considerations in designing interventions to curb adolescent problem behaviors. Further investigation is required to comprehensively understand these contextual disparities to effectively tailor prevention strategies (Deković 1999; Ozer et al. 2017).

Moreover, a more in-depth exploration is necessary to understand the precise mechanisms through which parental involvement influences adolescent behavior. Factors such as enhanced supervision, improved communication, or stronger emotional connections might contribute to more favorable behavioral outcomes (Deslandes et al. 1999; Ji et al. 2022). A clearer understanding of these mechanisms could inform the creation of targeted interventions that bolster parental roles effectively within rural settings.

The mediating effect of peer relationship and mental health between parental involvement and externalizing problem behaviors in rural adolescents

This research confirmed the second hypothesis (H2), suggesting that peer relationships act as a mediating factor in clarifying the relationship between parental involvement and externalizing problem behaviors among rural adolescents. This result aligns with the theoretical framework proposed by Mitic et al. (2021) and Chen et al. (2021), which emphasizes the substantial role of peer interactions in the behavioral development of adolescents. Our analysis indicated that elevated levels of parental involvement are generally associated with more favorable peer relationships, which subsequently correlate with a reduction in externalizing behaviors. This mediation implies that the quality of peer relationships could serve as a pivotal mechanism through which parental actions influence adolescent behavior.

Research findings on the mediating effects of peer relationships on adolescent behavior in varied settings were mixed. Our study contributes to the literature by concentrating on a rural adolescent population, a group frequently overlooked. Allen et al. (2007) demonstrated a similar mediating effect of peer relationships on adolescent behavior in a suburban context. Brown (2004) examined urban adolescents and noted a weaker mediating role of peer relationships, indicating that the rural context may magnify the importance of peers due to the restricted social resources and networks accessible to rural adolescents. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in rural China, where studies have shown that peer relationships play a crucial role in shaping adolescent behavior, largely due to limited social opportunities and community resources (Bilige and Gan 2020; Chen et al. 2021). The implications of these findings are twofold. First, they highlight the need for parental involvement programs that not only foster direct parental engagement but also enhance the quality of peer interactions among adolescents. Second, these results advocate for the development of community-based interventions that could bridge the gap in social resources, particularly in rural areas, thereby potentially mitigating externalizing problem behaviors through strengthened peer bonds.

Regarding the third hypothesis (H3), our findings supported that mental health acts as the intermediary through which parental involvement impacts the development of externalizing problem behaviors among rural adolescents. That is, increased parental involvement is positively linked to improved mental health, which, in turn, correlates with decreased instances of externalizing problem behaviors. This mediation underscores the essential role of mental health as a pathway through which parental involvement can positively influence adolescent externalizing problem behaviors. The significance of mental health as a mediator aligns with the findings of Jeynes (2012), who observed similar dynamics in a diverse adolescent population. However, our focus on rural adolescents introduces a new dimension to the literature, as this group may face unique stressors different from those encountered by urban youth (Fu and Zhou 2022; Li et al. 2020).

Additionally, the findings of this study resonate with the research conducted by Hill et al. (2004), who explored similar associations in a semi-urban setting but did not definitively establish mental health as a mediator. Our results suggest that the rural context may enhance the mediating role of mental health, possibly due to increased isolation and limited access to mental health resources in these areas, consistent with the findings of Hughes et al. (2022). This enhancement is likely a result of several factors unique to rural settings. For instance, rural communities often experience greater geographical isolation, which can limit social interactions and support networks, exacerbating feelings of loneliness and stress (Han and Ku 2019; Hirko et al. 2020). Additionally, rural areas typically have fewer healthcare facilities and mental health professionals, leading to restricted access to necessary mental health services and interventions (Johansson et al. 2019). The shortage of healthcare providers is made worse by the long distances residents must travel to reach available services, making it difficult to get timely care (Wang et al. 2021). Furthermore, cultural factors, such as stigma and a lack of confidentiality in small communities, may deter individuals from seeking mental health care (Graves et al. 2024). This emphasizes the necessity for targeted mental health interventions that are attuned to the geographical and cultural specifics of rural populations. In conclusion, this study enriches our understanding of the intricate interplay between parental involvement, mental health, and adolescent behavior, particularly in underrepresented rural settings. Future research should continue to explore these relationships across various cultural and socio-economic contexts to develop more comprehensive and effective intervention strategies.

Our findings supported the fourth hypothesis (H4), which delineates a chain mediating effect involving peer relationships and mental health in the pathway between parental involvement and externalizing problem behaviors among rural adolescents. This layered mediation underscores the complexity of the mechanisms through which parental influence can shape adolescent behavioral outcomes (Criss et al. 2002). Our analysis demonstrates that parental involvement initially enhances the quality of peer relationships, which, in turn, fosters better mental health, consequently reducing externalizing problem behaviors. This sequential mediation highlights the interconnected roles of social and psychological factors in mediating the impact of parental involvement on adolescent behavior. This finding is in line with the theoretical perspectives of Allen et al. (2007), who emphasize the interplay between social environments and individual psychological well-being in shaping adolescent behavior.

Furthermore, this study’s identification of a chain mediation adds depth to existing literature, which often focuses on single mediating variables. Our study further elucidates that these improved peer relationships significantly enhance adolescents’ mental health, as evidenced by reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression. This is consistent with the social support theory, which posits that supportive peer interactions can buffer against stress and promote psychological well-being (Thompson et al. 2016). Adolescents with strong peer support are more likely to experience better mental health, subsequently decreasing the likelihood of engaging in externalizing problem behaviors (Williams and Anthony 2015).

This chain mediation model also extends the findings of prior studies that have explored the individual mediating roles of peer relationships and mental health. Although Thompson et al. (2016) and Williams and Anthony (2015) have documented the impact of mental health as a mediator in behavioral outcomes, our study integrates these findings within a broader framework that includes peer relationships as a preceding mediator. This comprehensive approach provides a more holistic understanding of the sequential processes through which parental involvement exerts its influence on adolescent behavior. Additionally, our research underscores the unique challenges faced by rural adolescents, who often have limited access to mental health resources and supportive peer networks compared to their urban counterparts (Chen et al. 2021; Ji et al. 2017; Shalaby and Agyapong 2020). The findings highlight the importance of designing targeted interventions that foster positive peer interactions to improve mental health and reduce behavioral problems in this population. Future research should explore these dynamics across different cultural and socio-economic settings to refine intervention strategies further and ensure their applicability in diverse populations.

The moderating effect of problematic social media use between parental involvement and externalizing problem behaviors in rural adolescents

This research confirms the fifth hypothesis (H5), demonstrating that problematic social media use diminishes the protective influence of parental involvement against externalizing problem behaviors in rural adolescents. This finding is pivotal, as it highlights a crucial moderation effect that is particularly relevant in today’s digital era, where the intersection of technology and family dynamics is increasingly influential on adolescent development (Stalker 2020; Ohannessian and Vannucci 2021).

The reduction in the efficacy of parental involvement due to problematic social media use suggests a pressing need to adapt parental strategies to the realities of the digital landscape. This adaptation is critical, as traditional parenting roles and interactions may not be as effective without adjustments that take into account the pervasive presence of digital media (Brighi et al. 2019; Ma et al. 2023). Our results align with previous studies, including studies by George and Odgers (2015), which demonstrate that an increase in digital engagement among adolescents can disrupt traditional family roles and decrease the protective influence parents have over their children’s behaviors. As noted by Apel and Kaukinen (2008), the protective role of parents is critically undermined by the distractions and distortions presented by digital media, which can displace direct interaction and communication essential for effective parenting. In the context of digital engagement among Chinese adolescents, it seems that digital communication can lessen the protective influence parents have. This is especially true when adolescents perceive parental monitoring as intrusive or when there is a lack of open dialog about media use (Liu et al. 2019).

In the digital age, traditional parenting paradigms are increasingly challenged, necessitating a reevaluation of how parental roles are defined and executed. This adjustment is imperative to sustain the efficacy of parental involvement as a bulwark against adverse adolescent outcomes. Future research should delve deeper into these dynamics, exploring how different dimensions of parental involvement (such as emotional support, supervision, and communication) are specifically impacted by various forms of digital engagement. Additionally, it is crucial to develop and assess intervention strategies tailored to enhance parental efficacy in the digital realm, particularly in rural areas where such dynamics may be underexplored.

Our study also contributes to the field by focusing on the rural context, which has been relatively underexplored in existing literature. This focus is critical as rural adolescents may experience different patterns of social media use and parental interaction compared to their urban counterparts (Nagata et al. 2020; Zhu et al. 2021). By tailoring our analysis to this demographic, we provide insights that are specifically applicable to rural settings, thereby filling a significant gap in the literature.

In conclusion, our research not only highlights a crucial moderation effect but also serves as a clarion call for rethinking and reinforcing parental involvement in the digital age. It is imperative that we embrace these challenges as opportunities for innovation in parenting strategies, ensuring that the digital environment supports rather than undermines the developmental needs of adolescents.

Theoretical contribution and practical implications

The outcomes of this research are significant and yield insights from both theoretical and practical perspectives. Theoretically, this study elucidates the mechanisms through which parental engagement affects the emergence of externalizing behaviors in adolescents, thus broadening and enriching the existing empirical literature (Berg et al. 2011; Reitz et al. 2006; Ruiz-Hernández et al. 2018). Moreover, this study significantly extends the theoretical comprehension of parental involvement’s role in shaping adolescent behavior. By verifying that parental involvement may decrease adolescent externalizing problem behaviors, this research adds depth to existing models of adolescent psychological development. Crucially, it identifies the mediating roles of peer relationships and mental health, offering a more comprehensive framework for understanding how various factors interact to influence adolescent behavior. The study also introduces the concept of problematic social media use as a moderating factor, thereby broadening the scope of research on parental influence to include digital behaviors.

Our findings also have practical implications. The findings of this study provide valuable insights for strategies aimed at reducing externalizing behaviors among adolescents, particularly in rural settings. The protective role of parental involvement suggests that programs designed to enhance parental engagement could be effective in mitigating behavioral issues. Moreover, the mediating roles of peer relationships and mental health underscore the importance of comprehensive support systems that address multiple aspects of an adolescent’s social and psychological environment. The moderating effect of problematic social media use highlights the need for digital literacy programs that help parents and adolescents navigate online behaviors. To address externalizing problem behaviors among rural adolescents, stakeholders in educational and community health settings are encouraged to implement and support multifaceted intervention strategies that consider the interconnectedness of these variables. First, educational programs for parents should be implemented to enhance their awareness and management skills regarding externalizing behaviors. Active parental involvement in daily interactions and decision-making processes with adolescents should be encouraged, thereby fostering a supportive home environment that promotes positive behavioral outcomes. Second, schools should facilitate the development of peer support groups that enable adolescents to share experiences and coping strategies. The implementation of school-based counseling and mentoring programs can also mediate the influence of negative peer interactions. Third, it is essential to establish accessible mental health services within the community that provide screening, counseling, and therapy for adolescents. These services should be specifically tailored to address the psychological needs of rural youths, with a focus on enhancing resilience and emotional regulation skills. Finally, community-wide programs that educate adolescents about the risks associated with excessive social media use should be introduced. Policy initiatives could include creating safer online environments and promoting digital literacy to mitigate the negative impacts of social media on adolescent behavior.

Limitations

This research is subject to several constraints. First, the data were sourced exclusively from three provinces (Liaoning, Shandong, and Guangxi), limiting the generalizability of the results across the broader population. Future investigations should strive to incorporate a nationally representative sample to improve the external validity of the findings. Such an approach ensures that the outcomes are not merely reflective of the provinces sampled but are indicative of national trends. Additionally, securing a sample that mirrors the national demographic would address potential regional disparities in parental engagement and the prevalence of externalizing behaviors among adolescents. Second, the use of cross-sectional data captures only a temporal glimpse of the dynamics between parental involvement and adolescent externalizing behaviors. This snapshot may not accurately reflect changes over time. To better discern causality and evolution in these relationships, future research should employ longitudinal methodologies, tracking a cohort over time.

Third, the reliance on self-report surveys presents limitations, as these measures depend on the subjective views of the participants, which may not align with external assessments. Future studies should include diverse informants, such as parents, peers, and educators, to provide a more holistic and unbiased perspective on the links between parental involvement and adolescent behavior. This multi-informant approach could also uncover potential biases in self-reported data. Fourthly, the study did not fully explore various other factors that may influence externalizing behaviors. Subsequent research should consider additional variables, including cultural and ethnic differences as well as neurobiological factors, to thoroughly understand the complex mechanisms underpinning these behaviors.

Conclusions

The current study examined externalizing problem behaviors in rural adolescents and identified antecedent factors influencing these behaviors. Our findings demonstrate that parental involvement serves as a protective factor in reducing such behaviors within this demographic. Peer relationship and mental health were identified as mediators in the relationship between parental involvement and adolescent externalizing problem behaviors. Specifically, the pathway is: Parental involvement → Peer relationship → Mental health → Externalizing problem behaviors. This pathway illustrates how supportive parental engagement can foster positive peer interactions and better mental health, subsequently reducing externalizing problem behaviors. Additionally, the study reveals that problematic social media use can impact the relationship between parental involvement and externalizing problem behaviors. As the frequency of problematic social media use increases among adolescents, the protective benefits of parental involvement diminish. This finding highlights the nuanced role of digital behavior in adolescent development and the challenges it presents to traditional protective factors.

The contributions of this research are twofold. Theoretically, it extends the existing literature by elucidating the complex mechanisms through which parental involvement influences externalizing problem behaviors in Chinese rural adolescents. It provides a more nuanced understanding of the interplay between social and psychological factors, enhancing existing models of adolescent behavior. Practically, the study offers actionable insights for stakeholders aiming to reduce externalizing problem behaviors in rural settings. This includes encouraging parental involvement, fostering supportive peer relationships, and promoting mental health, alongside addressing the challenges posed by problematic social media use. The research underscores the need for comprehensive intervention strategies that encompass these various dimensions to effectively address and mitigate externalizing problem behaviors among rural adolescents.

Data availability

Participants were informed during the data collection process that their information would remain confidential and that no one outside the research team would have access to the data, so the datasets generated and analyzed in this study cannot be shared publicly as this was explicitly stated in the consent forms.

References

Acar S, Chen CI, Xie H (2021) Parental involvement in developmental disabilities across three cultures: a systematic review. Res Dev Disabil 110:103861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2021.103861

Achenbach TM (1991a) Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR, and TRF profiles. Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont, Burlington

Achenbach TM (1991b) Manual for the youth self-report and 1991 profile. Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont, Burlington

Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT (1987) Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychol Bull 101(2):213–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.101.2.213

Aho H, Koivisto AM, Paavilainen E, Joronen K (2018) Parental involvement and adolescent smoking in vocational settings in Finland. Health Promot Int 33(5):846–857. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dax027

Allen JP, Porter M, McFarland C, McElhaney KB, Marsh P (2007) The relation of attachment security to adolescents’ paternal and peer relationships, depression, and externalizing behavior. Child Dev 78(4):1222–1239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01062.x

Anyiwo N, Watkins DC, Rowley SJ (2022) “They can’t take away the light”: Hip-Hop culture and Black youth’s racial resistance. Youth Soc 54(4):611–634. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X2110010

Apel R, Kaukinen C (2008) On the relationship between family structure and antisocial behavior: parental cohabitation and blended households. Criminology 46(1):35–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2008.00107.x

Baig T, Ganesan GS, Ibrahim H, Yousuf W, Mahfoud ZR (2021) The association of parental involvement with adolescents’ well-being in Oman: evidence from the 2015 Global School Health Survey. BMC Psychol 9(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00677-5

Bandura A (2001) Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol 52:1–26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

Bandura A (2006) Adolescent development from an agentic perspective. In: Pajares F, Urdan T (eds) Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents, vol 5. Information Age Publishing, Greenwich, England, pp 1–43

Bao Z, Li D, Zhang W, Wang Y (2015) School climate and delinquency among Chinese adolescents: analyses of effortful control as a moderator and deviant peer affiliation as a mediator. J Abnorm Child Psychol 43(1):81–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9903-8

Barry CM, Wentzel KR (2006) Friend influence on prosocial behavior: the role of motivational factors and friendship characteristics. Dev Psychol 42(1):153–163

Berg CA, King PS, Butler JM, Pham P, Palmer D, Wiebe DJ (2011) Parental involvement and adolescents’ diabetes management: the mediating role of self-efficacy and externalizing and internalizing behaviors. J Pediatr Psychol 36(3):329–339. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsq088

Berk LE (1997) Child development. Allyn & Bacon, Boston

Bilige S, Gan Y (2020) Hidden school dropout among adolescents in rural China: individual, parental, peer, and school correlates. Asia Pac Educ Rev 29(3):213–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-019-00471-3

Boniel-Nissim M, van den Eijnden RJ, Furstova J, Marino C, Lahti H, Inchley J, Badura P (2022) International perspectives on social media use among adolescents: implications for mental and social well-being and substance use. Comput Hum Behav 129:107144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.107144

Brighi A, Menin D, Skrzypiec G, Guarini A (2019) Young, bullying, and connected. Common pathways to cyberbullying and problematic internet use in adolescence. Front Psychol 10:457698. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01467

Brock RL, Kochanska G (2016) Interparental conflict, children’s security with parents, and long-term risk of internalizing problems: a longitudinal study from ages 2 to 10. Dev Psychopathol 28(1):45–54. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579415000279

Bronfenbrenner U (1999) Ecology of the family as a context for human development: research perspectives. In: Adolescents and their families, 1st edn. Routledge, London, p 20

Bronfenbrenner U (1992) Six theories of child development: revised formulations and current issues. In: Vasta R (ed) Ecological systems theory. Jessica Kingsley, London, pp 187–249

Brown BB (2004) Adolescents’ relationships with peers. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L (eds) Handbook of adolescent psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ, pp 363–394

Canet F, Pérez-Escolar M (2023) Research on prosocial screen and immersive media effects: a systematic literature review. Ann Int Commun Assoc 47(1):20–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2022.2130810

Carlo G, Crockett LJ, Wolff JM, Beal SJ (2012) The role of emotional reactivity, self-regulation, and puberty in adolescents’ prosocial behaviors. Soc Dev 21(4):667–685. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2012.00660.x

Chen BB, Qu Y, Yang B, Chen X (2022) Chinese mothers’ parental burnout and adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems: the mediating role of maternal hostility. Dev Psychol 58(4):768–777

Chen X, Zhong H (2012) Stress, negative emotions, and the deviant behaviors of Chinese migrant children. Issues Juv Crimes Delinq 5:22–33

Chen X, Li L, Lv G, Li H (2021) Parental behavioral control and bullying and victimization of rural adolescents in China: the roles of deviant peer affiliation and gender. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(9):4816. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094816

Chi X, Cui X (2020) Externalizing problem behaviors among adolescents in a southern city of China: gender differences in prevalence and correlates. Child Youth Serv Rev 119:105632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105632

Church WTII, Jaggers JW, Taylor JK (2012) Neighborhood, poverty, and negative behavior: an examination of differential association and social control theory. Child Youth Serv Rev 34(5):1035–1041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.02.005

Cooke JE, Racine N, Plamondon A, Tough S, Madigan S (2019) Maternal adverse childhood experiences, attachment style, and mental health: pathways of transmission to child behavior problems. Child Abuse Negl 93:27–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.04.011

Coyne SM, Padilla‐Walker LM, Holmgren HG (2018) A six‐year longitudinal study of texting trajectories during adolescence. Child Dev 89(1):58–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12823

Criss MM, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Dodge KA, Lapp AL (2002) Family adversity, positive peer relationships, and children’s externalizing behavior: a longitudinal perspective on risk and resilience. Child Dev 73(4):1220–1237. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00468

Deković M (1999) Risk and protective factors in the development of problem behavior during adolescence. J Youth Adolesc 28(6):667–685. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021635516758

Delgado E, Serna C, Martínez I, Cruise E (2022) Parental attachment and peer relationships in adolescence: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(3):1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031064

Desha LN, Nicholson JM, Ziviani JM (2011) Adolescent depression and time spent with parents and siblings. Soc Indic Res 101(2):233–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9658-8

Deslandes R, Potvin P, Leclerc D (1999) Family characteristics as predictors of school achievement: parental involvement as a mediator. McGill J Educ 34(002). https://mje.mcgill.ca/article/view/8474

Dewalt DA, Thissen D, Stucky BD, Langer MM, Dewitt M, Irwin E, Lai DE, Yeatts JS, Gross KB, Taylor HE, Varni JW (2013) PROMIS Pediatric Peer Relationships Scale: development of a peer relationships item bank as part of social health measurement. Health Psychol 32(10):1093–1103. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032670

Donaldson-Feilder EJ, Bond FW (2004) The relative importance of psychological acceptance and emotional intelligence to workplace well-being. Br J Guid Couns 32(2):187–203

Eccles JS, Roeser RW (2011) Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. J Res Adolesc 21(1):225–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00725.x

Feng L, Lan X (2020) The moderating role of autonomy support profiles in the association between grit and externalizing problem behavior among family-bereaved adolescents. Front Psychol 11:1578. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01578

Ferguson CJ (2015) Do angry birds make for angry children? A meta-analysis of video game influences on children’s and adolescents’ aggression, mental health, prosocial behavior, and academic performance. Perspect Psychol Sci 10(5):646–666. https://doi.org/10.1177/174569161559223

Fiani C, Saeghe P, McGill M, Khamis M (2024) Exploring the perspectives of social VR-aware non-parent adults and parents on children’s use of social virtual reality. Proc ACM Hum Comput Interact 8(CSCW1):1–25. https://doi.org/10.1145/3652867

Flykt M, Vänskä M, Punamäki RL, Heikkilä L, Tiitinen A, Poikkeus P, Lindblom J (2021) Adolescent attachment profiles are associated with mental health and risk-taking behavior. Front Psychol 12:761864. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.761864

Fortuin J, van Geel M, Vedder P (2015) Peer influences on internalizing and externalizing problems among adolescents: A longitudinal social network analysis. J Youth Adolesc 44:887–897. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0168-x

Fowler PJ, Henry DB, Marcal KE (2015) Family and housing instability: longitudinal impact on adolescent emotional and behavioral well-being. Soc Sci Res 53:364–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.06.012

Fu Y, Zhou X (2022) Effects of parental migration on Chinese children’s mental health: mediating roles of social support from different sources. Child Fam Soc Work 27(3):465–477. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12899

George MJ, Odgers CL (2015) Seven fears and the science of how mobile technologies may be influencing adolescents in the digital age. Perspect Psychol Sci 10(6):832–851. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615596788

Giordano PC (2003) Relationships in adolescence. Annu Rev Sociol 29(1):257–281. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100047

Gómez P, Harris SK, Barreiro C, Isorna M, Rial A (2017) Profiles of Internet use and parental involvement, and rates of online risks and problematic Internet use among Spanish adolescents. Comput Hum Behav 75:826–833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.027

Goncy EA, van Dulmen MH (2010) Fathers do make a difference: parental involvement and adolescent alcohol use. Fathering 8(1):93–108

Goodall J, Montgomery C (2023) Parental involvement to parental engagement: a continuum. In: Mapping the field, 1st edn. Routledge, London, p 12

Graves JM, Abshire DA, Koontz E, Mackelprang JL (2024) Identifying challenges and solutions for improving access to mental health services for rural youth: Insights from adult community members. Int J Environ Res Public Health 21(6):725. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21060725

Gu X, Hassan NC, Sulaiman T (2024) The relationship between family factors and academic achievement of junior high school students in rural China: mediation effect of parental involvement. Behav Sci 14(3):221. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030221

Guo L, Wang T, Wang W, Huang G, Xu Y, Lu C (2019) Trends in health-risk behaviors among Chinese adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(11):1902. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16111902

Han X, Ku L (2019) Enhancing staffing in rural community health centers can help improve behavioral health care. Health Aff 38(12):2061–2068. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00823

Harris-McKoy D, Cui M (2013) Parental control, adolescent delinquency, and young adult criminal behavior. J Child Fam Stud 22:836–843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9641-x

Hartup WW (1992) Peer relations in early and middle childhood. In: Hasselt VB, Hersen M (eds) Handbook of social development: a lifespan perspective. Springer, New York, pp 257–281

Hawi NS, Samaha M (2017) The relations among social media addiction, self-esteem, and life satisfaction in university students. Soc Sci Comput Rev 35(5):576–586. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439316660340

Herrenkohl TI, Catalano RF, Hemphill SA, Toumbourou JW (2009) Longitudinal examination of physical and relational aggression as precursors to later problem behaviors in adolescents. Violence Vict 24(1):3–19. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.24.1.3

Hill NE, Castellino DR, Lansford JE, Nowlin P, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS (2004) Parent academic involvement as related to school behavior, achievement, and aspirations: demographic variations across adolescence. Child Dev 75(5):1491–1509. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00753.x

Hindelang RL, Dwyer WO, Leeming FC (2001) Adolescent risk-taking behavior: a review of the role of parental involvement. Curr Probl Pediatr 31(3):67–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1538-5442(01)70035-1

Hirko KA, Kerver JM, Ford S, Szafranski C, Beckett J, Kitchen C, Wendling AL (2020) Telehealth in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for rural health disparities. J Am Med Inform Assoc 27(11):1816–1818

Hirschi T (1969) Causes of delinquency. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

Huang L, Zhang J, Duan W, He L (2021) Peer relationship increasing the risk of social media addiction among Chinese adolescents who have negative emotions. Curr Psychol 42(9):7673–7681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01997-w

Huang Y, Zhong XN, Li QY, Xu D, Zhang XL, Feng C, Deng B (2015) Health-related quality of life of the rural-China left-behind children or adolescents and influential factors: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 13:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-015-0220-x

Huebner ES, Hills KJ, Jiang X, Long RF, Kelly R, Lyons MD (2014) Schooling and children’s subjective well-being. In: Ben-Arieh A, Casas F, Frønes I, Korbin JE (eds) Handbook of child well-being: theories, methods and policies in global perspective. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 797–819

Hughes MC, Spana E, Cada D (2022) Developing a needs assessment process to address gaps in a local system of care. Community Ment Health J 58(7):1329–1337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-022-00940-y

Huston A (2018) Social learning theory: bullying in schools. Semant Sch, New York

Jaiswal SK (2017) Role of parental involvement and some strategies that promote parental involvement. J Int Acad Res Multidiscip 5(2):95–104

Jeynes W (2012) A meta-analysis of the efficacy of different types of parental involvement programs for urban students. Urban Educ 47(4):706–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085912445643

Ji W, Yang Y, Han Y, Bian X, Zhang Y, Liu J (2022) Maternal positive coparenting and adolescent peer attachment: chain intermediary role of parental involvement and parent-child attachment. Front Psychol 13:976982. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.976982

Ji Y, Zhang Y, Yin F, Yang SJ, Yang Y, Liu QL (2017) The prevalence of depressive symptoms and the relationships between depressive symptoms, self-esteem and social support among rural left-behind children in Sichuan province. Mod Prev Med 44(2):239–242

Johansson P, Blankenau J, Tutsch SF, Brueggemann G, Afrank C, Lyden E, Khan B (2019) Barriers and solutions to providing mental health services in rural Nebraska. J Rural Ment Health 43(2-3):103–107. https://doi.org/10.1037/rmh0000105

Jones CN, You S, Furlong MJ (2013) A preliminary examination of covitality as integrated well-being in college students. Soc Indic Res 111(2):511–526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0017-9