Abstract

With the continuous increase of older adults, population ageing has become a public policy issue worldwide. Gaining insight into the current state of population ageing and its impact on income inequality is essential for designing effective and equitable policies that support economic development and social stability. This study, focusing on rural China, explores the relationship between population ageing and Gini coefficient of income, using nationally representative rural household data collected by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China from 2003 to 2020. Results based on the decoupling index and decomposition method reveal that the issue of income inequality in the surveyed rural areas has not intensified with the progression of ageing, which overturns the predominant view in existing research that population ageing exacerbates income inequality. The findings indicate that the inhibitory effect of increasing transfer income on income inequality has become more pronounced as ageing deepens, and the income structural effect of rural residents in China has played a role in reducing the Gini coefficient. Based on these results, some suggestions are proposed such as raising parental allowance, improving rural production and living environment, constrcuting the long-term care system, and implementing multifaceted measures to enhance the income level of rural older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past forty years, with the continuous reinforcing of economic globalization and capital expansion, income inequality has intensified, becoming one of the most challenging issues facing the international community (Milanovic, 2016; Wan et al., 2022). To provide insights into the root causes and potential solutions of income inequality, the impact of education, gender, industrialization, urbanization and so forth, has been proven by scholars (Autor, 2014; Xie and Zhou, 2014; Card et al., 2016; Sulemana et al., 2019; Ali et al., 2022). Due to the continuous improvement of living standards and advances in medical and public health services, mortality rates have declined (Oeppen and Vaupel, 2002; Vaupel, 2010; Dong et al., 2016), and the population structure has shifted toward ageing (Marois et al., 2020). Thus, related research on the impact of population ageing on income inequality emerged in the late 20th century (Paglin, 1975; Deaton and Paxson, 1997). However, compared to other factors, the impact of population ageing on income distribution seems to have not received sufficient attention.

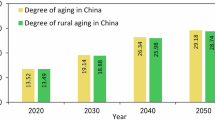

Since the beginning of the 21st century, both the number and proportion of older adults have been increasing in almost all countries around the world, and the global population is entering an ageing stage (World Health Organization, 2022). It is expected that by 2050, the proportion of the older adults aged 65 and above will increase to 16% from 10% in 2022, and the global population aged 65 and above will be more than twice that of children under age 5, roughly equal to the number of children under age 12 (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2022). This demographic shift may place economic and political pressures on many countries, particularly in areas such as public services, pensions, and social security, making population ageing a global public policy issue (Harper, 2014). It should be noted that the impact of global ageing may be more profound in developing countries, especially in Asia and Latin America, where population structures are rapidly changing. According to the World Health Organization, 80% of older adults will live in low- and middle-income countries by 2050 (World Health Organization, 2022). However, compared to developed countries, the older adults in developing countries face more serious public health challenges, such as high rates of incidence, elevated medical costs, inadequate supply of medical services, and relatively low quality of life (Mahal and McPake, 2017; Chen, 2019; Muhammad et al., 2022).

The proportion of population aged 65 and above in China, the world’s largest developing country, reached 15.40% in 2023 (The National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2024), which shows that the country has entered an aged society. The problem of population ageing in rural areas is even more severe. According to the data from the Seventh National Population Census in China, the proportion of population aged 65 and above in rural areas is 17.72% in 2020, which is 6.61 percentage points higher than in urban areas (The National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2021). The population ageing process in China continues to accelerate, which not only directly affects the well-being of the older adults, but also exacerbates the burden of shared debt on society, affecting overall social fairness. Meanwhile, China’s income gap is still large. The Gini coefficient of per capita disposable income for Chinese residents reached its highest point of 0.491 in 2008. Although it dropped to 0.468 by 2020 (The National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2021), it was still above the international warning line of 0.40. The income gap within rural residents is particularly evident. It shows that the per capita disposable income of low-income rural households in 2022 was 5024.6 yuan, only 10.91% of the high-income group (The National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2023). At present, the population ageing and income inequality are two critical factors affecting China’s economic development and social stability. Especially limited by the long-standing urban-rural dual economic structure and urban-biased economic policies, China is facing the problem of population ageing and “getting old before getting rich”, particularly evident in rural areas.

Currently, China is in a critical period of socioeconomic and demographic transformation. Exploring the relationship between population ageing and income inequality in rural China is not only conducive to alleviating the problem of imbalanced and insufficient development, but also deepens the understanding of population ageing and income inequality in developing countries, which holds important practical significance and realistic value. The structure of this paper is as follows: First, the analysis framework of population ageing and income inequality is constructed. Secondly, the basic characteristics and relationship of the two in rural China are outlined. Thirdly, the decoupled index and decomposition method are used to further explore the contribution of population ageing to income inequality and its change in rural China. Finally, the influence process is discussed and the policy implications are put forward.

Literature review

Theoretical literature

As early as the 1950s, Kuznets explores the relationship between economic growth and income inequality, believing that social income distribution inequality exhibits an “inverted U-shaped” trend of increasing first and decreasing later (Kuznets, 1955). It is claimed that the growth rate or stage of a country and its type of growth and institutions determine inequality (Saez and Zucman, 2016; Alam and Paramati, 2016; Aghion et al., 2019; Hidalgo, 2021; Pfeffer and Waitkus, 2021). According to Hartmann et al. (2017), when industrial policies does not match social development, inequality exacerbates and impedes the development of economy.

The Lorenz curve is a graphical tool used in economics to represent the degree of income or wealth inequality within a country or region, and it is widely used to study the distribution of national income among citizens (Gastwirt, 1972; Kakwani, 1977; Davies and Hoy, 1995; Delbosc and Currie, 2011; Almas et al., 2011). In practical applications, the Gini coefficient can be calculated using the Lorentz curve to measure the degree of inequality (Bhattacharya, 2007; Giorgi and Gigliarano, 2017).

As one of the inevitable trends faced by many countries and regions around the world, population ageing has a relatively significant impact on income inequality (Bishop et al., 1997; Cameron, 2000; Shrestha, 2000). Deaton and Paxson (1998) show that if employers pay workers their expected marginal product, the within-cohort income inequality will gradually intensify as age rises. Dynan et al. (2009) explains that population ageing may have a significant impact on the relationship between macroeconomic aggregates such as income and consumption, if considering the differences in savings rates and marginal propensity to consume throughout the entire lifecycle. It is described by Zhong (2011) that the different proportions of labor force caused by population ageing exacerbates income inequality. According to Cai (2012), the demographic transformation caused by economic growth and social development in China, which is much earlier than other countries, has led to the result of “ageing before affluence”.

From the perspective of impact mechanism, Dannefer (2003) suggests that the advantages and disadvantages of early life accumulate throughout the entire life process, leading to the increase of inequality with the growth of age. According to Hungerford (2020), different salary levels can lead to significant differences in pension, savings, and post-retirement income, exacerbating income inequality after retirement. It is also recognized by Kreps (1970) that factors such as rising healthcare costs and taxes, as well as early retirement from the labor force, exacerbates the impact of population ageing on income inequality. In addition, the mechanisms by which population ageing affects income inequality, such as labor market institutions, human capital investment and public policy (Glawe and Wagner, 2020; Birnbaum and De Wispelaere, 2021; Ebbinghaus, 2021; Duignan and Dutton, 2024), are discussed.

The relationship between population ageing and income inequality

The existing empirical literature explains the relationship between population ageing and income inequality to some extent. According to some studies, population ageing exacerbates income inequality. For example, it is examined by Hwang et al. (2021) that the Gini coefficient increases when 10% of the age group between 35 and 44 is substituted by the 65 and above group, which means that population ageing exacerbates income inequality. According to Cuaresma et al. (2016), the unprecedented population ageing is expected to slow down the pace of income convergence in European countries. Kim and Kim (2024) draw the same conclusion that population ageing is the most important reason for the exacerbation of income inequality among low-income groups in the 21st century. Research by Rowe (2019) comes up with a similar viewpoint. It demonstrates that low-income older adults are facing the greatest risk of economic security losses while middle-income older adults are also confronted with enormous economic challenges. In addition, some researchers have also confirmed the positive correlation between population ageing and income inequality through quantitative analysis (Karunaratne, 2000; Gomez and Foot, 2003; Kim and Kim, 2017; Dong et al., 2018; Shaik et al., 2024).

Different from the above viewpoints, some researchers believe that population ageing has no positive impact on income inequality and it shows a reverse relationship. For example, the research results of Shirahase (2015) show that income inequality among households with older adults generally decreases, and the decline is relatively greater among high-income groups after the mid-1980s, which is caused by the decline in three-generation households. Hammer et al. (2022) indicate that the higher employment among older adults and the strong increase in public pensions resulted in an increase in income for older adults. Besides, it has been proven that population ageing has a negative impact on income inequality by Prus (2000) and Jamil et al. (2024).

As far as China is concerned, the Chinese government has been actively addressing the challenges posed by population ageing by formulating and implementing a series of policies to ensure and improve the rights and interests of older adults (Liu et al., 2023). The continuous improvement of the social security system provides support for alleviating income inequality. With the improvement of the pension security system and the increase in pension coverage, older adults can obtain pension income more stably, which helps to narrow the income gap (Zhang et al., 2012; Li and Lin, 2016). At the same time, the Chinese government is increasing its education resources and investment towards rural areas, and by improving the education level in rural areas, it is expected to narrow the income gap between urban and rural areas. This not only contributes to the economic development of rural areas, but also provides more opportunities for rural older adults to increase their income (Woo, 2017; Tu et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). Besides, the Chinese government is accelerating the construction of care service system for older adults, which can provide more convenient and efficient care services, reduce family burden and improve the quality of life for older adults (Wang and Zhou, 2020; Feng and Wu, 2023). Based on the above conclusions, we propose Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 1

H1: Population ageing has no positive impact on income inequality in rural China.

The impact of population ageing on income inequality in four categories

Shorrocks (1982) proposes to decompose inequality by source of income, which is disaggregated into earnings, investment income and transfer payments. Davis et al. (2010) divides rural income generating activities into agricultural income, non-agricultural income, self-employment, transfers and others. In China, the income of rural households is usually divided into labor remuneration, household business, non-farm activity, and private transfer and property (Khan and Riskin, 1998). According to the division of the National Bureau of Statistics of China and combined with relevant research experience, this paper divides household income in rural China into wage and salary, business income, property income and transfer income.

In terms of wage and salary, with the increase in the proportion of older adults in rural areas, the labor supply is gradually decreasing, the structural shortage of labor resources has corrected the long-term distorted rural labor prices, and the growth rate of rural labor income may accelerate (Li et al., 2013; Böhm et al., 2021). As far as business income is concerned, the labor efficiency of older adults is relatively low, which may lead to a decrease in agricultural output. And the older adults have a lower acceptance of new technologies and agricultural modernization, which may affect the efficiency and quality of agricultural production, indirectly affecting the business income of farmers, and exacerbates income inequality (Liu et al., 2023; Ren et al., 2023). As for property income, in the context of population ageing, some farmers may be unable to continue cultivating land due to physical exhaustion, resulting in idle or inefficient use of land resources.

Through land transfer and scale management, land resources can be effectively integrated, and it also increases the property income of older adults (Min et al., 2017; Li et al., 2023). On the part of transfer income, the Chinese government continuously strengthens the construction of the rural social security system and improves the social security level of older adults in rural areas, which includes raising the standards for social security income such as pensions, as well as expanding the coverage of social assistance (Benjamin et al., 2000). These measures help to increase the transfer income of older adults in rural China and alleviate income inequality. Based on the above analysis, we propose Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 2

H2: Population ageing has different impacts on income inequality from different sources in rural China.

Methodology

Dataset

This paper uses data from China Rural Fixed Observation Points from 2003 to 2020, collected by Research Center for Rural Economy under the Ministry of Agricultural and Rural Affairs of China, which includes comprehensive information about rural households and their members. It is nationally representative survey data. The survey was formally set up in 1986 and has been run until now, covering about 23,000 rural households and 375 villages in 368 counties of 31 provinces (excluding Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan) (Fig. 1, Table 1). With the disappearance of the old households and interviewees due to death or urbanization, some new households and interviewees gradually joined the survey year by year, and the sample size remains stable over the past decades.

Measurement of income

(1) Wage and salary income: wage income of rural cadres, rural teachers, and local and out-of-town employment. (2) Business income. (3) Property income: income from the rental of cultivated land, forest land, housing, etc.; dividend income from village collectives, cooperatives, etc., as well as interest. (4) Transfer income: retirement payments, pensions, old age allowance for older adults, and other non-loan income from the government and family support.

Methods

Gini coefficient

The Gini coefficient is calculated using data on the incomes of households or groups. The specific calculation formula is as follows:

Here, \({W}_{i}\) and \({P}_{i}\) refer to ranking the surveyed households by income from low to high, and calculating the proportion of the income of the population represented by the ith household in the total income (\({W}_{i}\)) and the proportion of the population represented by the ith household in the total population (\({P}_{i}\)). It is generally believed that when the Gini coefficient is less than 0.2, it indicates that the income distribution of residents is too average; when it is between 0.2 and 0.3, it is more average; when it is between 0.3 and 0.4, it is more reasonable; when it is between 0.4 and 0.5, the gap is too large; when it is greater than 0.5, the gap is wide.

Bivariate spatial correlation

Bivariate spatial correlation measures the degree to which the value for a given variable at a location is correlated with its neighbors for a different variable. It extends the idea of the univariate Moran’s I with a variable on the x-axis and its spatial lag on the y-axis to a bivariate context, and the spatial lag pertains to a different variable (Anselin, 2019). In our case, it measures the degree to which the value for population ageing at a location is correlated with its neighbors for Gini coefficient. As in the univariate Moran scatter plot, the slope of the linear fit to the scatter plot equals Moran’s I:

with wij as the elements of the spatial weights matrix.

Decoupling Index (DI)

Referring to the approach of Tapio (2005), the decoupling index can be expressed as the ratio of the year-on-year growth rate of rural households’ income Gini coefficient in various regions and years to the year-on-year growth rate of population ageing.

Due to the increasing proportion of the rural older adults in various regions in most years, the direction of the decoupling index mainly depends on the direction of changes in income inequality. When DI > = 1, it indicates that the rate of income inequality exacerbation is faster than the rate of population ageing. When 0 < DI < 1, it indicates that the two are relatively decoupled, indicating that the rate of income inequality exacerbation is slower than the rate of population ageing. When DI < = 0, it indicates an absolute decoupling between the two, indicating that the ageing population does not bring about income inequality.

Decomposition of income inequality

The Gini coefficient of total income inequality can be expressed as

In the equation, \({S}_{k}\) represents the share of income from different sources in total income, which indicates the importance of income sources to total income. \({G}_{k}\) represents the Gini coefficient corresponding to income from different sources, which denotes equality or inequality in the distribution of income sources. \({R}_{k}\) denotes the correlation between income from different sources and total income (Stark et al., 1986). The product \({\bar{G}}_{t}\left({y}^{k}\right)\) of \({G}_{k}\) and \({R}_{k}\) is called income concentration rate of income k.

The percent change in inequality resulting from a small percent change in income from source k equals the original contribution of source k to income inequality minus source k’s share of total income (Lerman and Yitzhaki, 1985). As shown in the following equation,

Decomposition of income inequality change

The intertemporal variation of Gini coefficient can be decomposed into three parts, including structural effect, concentrated effect and comprehensive effect. The first part represents the change of Gini coefficient caused by the change of the proportion of each sub-item of income in total income, the second part is the change of Gini coefficient caused by the change of income concentration rate, and the third part is the change of Gini coefficient caused by the combined effect of the proportion and concentration rate of each income.

Result

The characteristics of population ageing and income inequality in rural China

The research results show that the scale of the older adults in rural China has continued to expand, and the degree of ageing has continued to increase since 2003. From 2003 to 2020, the proportion of older adults (aged 65 or older) in rural areas surveyed increased from 7.0% to 18.4%. In 2019, the proportion exceeded 14%, and the overall population entered a stage of moderate ageing. According to the seventh national population census of China, as of the end of 2020, the number of older adults aged 65 and above in rural areas of China was 90 million, accounting for 17.72% of the total population in rural areas (The National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2021), an increase of 7.66 percentage points compared to 2010 (10.06%) and 10.24 percentage points compared to 2000 (7.48%). This is basically consistent with the research results of this paper, indicating a high level of credibility and accuracy in this study.

There are differences in the proportion and growth rate of older adults in rural China among different regions. Figure 2a–d shows the ageing status of the rural population in China’s 216 prefecture-level administrative regions in 2003, 2009, 2014, and 2020, respectively. The results indicate that as the degree of ageing continues to deepen, the regional structure of ageing in the surveyed rural areas has also undergone significant changes. In 2003, the proportion of prefecture-level administrative regions with a population aged 65 and above accounting for over 14% in rural areas was only 2.9% of all prefecture-level administrative regions. By 2020, this proportion had risen to 74.4%, and most regions had reached a moderate level of ageing.

This paper uses the Gini coefficient as an indicator to measure the degree of income inequality among the rural population in China. Figure 3a–d shows the Gini coefficients of surveyed rural households in 216 prefecture-level administrative regions of China in 2003, 2009, 2014, and 2020, respectively. The results show that the Gini coefficient of the surveyed rural households has a relatively stable change and does not exhibit drastic fluctuations like the ageing rate of the population. In 2003, the proportion of prefecture-level administrative regions with a Gini coefficient lower than 0.2 (internationally, a Gini coefficient lower than 0.2 indicates a highly average income, 0.2–0.3 indicates a relatively average income, 0.3–0.4 indicates a relatively reasonable income, 0.4–0.5 indicates a large income gap, and 0.5 or above indicates a significant income gap) was 11.2%, and the proportion of prefecture-level administrative regions with a Gini coefficient higher than 0.5 was 9.1%. In 2020, the proportion of prefecture-level administrative regions with Gini coefficients below 0.2 and above 0.5 among surveyed rural households decreased to 9.5% and 5.9%, respectively, a decrease of 1.7 percentage points and 3.2 percentage points compared to 2003. Income inequality among rural residents is being alleviated.

Table 2 shows that the spatial autocorrelation of population ageing and income inequality is changing over time. Before 2013, the Moran’s I is positive and significant at the first years. After that, the Moran’s I becomes negative and insignificant anymore. It suggests that the spatial autocorrelation of population ageing and income inequality has disappeared.

The characteristics of income inequality in the context of population ageing

To explore the relationship between population ageing and income inequality in rural China, we conduct linear fitting on the relationship between population ageing and income inequality in different rural regions. Figure 4 shows the scatter plot and fitting line of the Gini coefficient of rural residents’ income and rural population ageing in the seven regions of China from 2003 to 2020. During this period, the relationship between the population ageing and income inequality in rural China shows some differences in different regions. However, the issue of income inequality in rural areas of China does not intensify with the ageing rural population. Among the seven regions, there is a significant negative correlation between rural population ageing and income inequality in South, Southwest and East China and a weak negative correlation in Northwest and Central China, while there is almost no relationship in North and Northeast China.

To gain a deeper understanding of the relationship between population ageing and income inequality in rural China, we divide rural households into different age groups based on the average age of the family and calculate the income Gini coefficient of three kinds of households. Figure 5 shows the differences in the Gini coefficient of total income among rural households of different average age groups. From 2003 to 2020, there are significant differences in the level of income inequality among rural households of different average age groups. Specifically, the Gini coefficient of older rural households is relatively stable, and the highest (mean = 0.43, SD = 0.013). The Gini coefficient of middle-aged rural households (mean = 0.41, SD = 0.022) is slightly higher than the overall Gini coefficient (0.40) and higher than that of young rural households (0.36). Overall, the income Gini coefficient of rural households with older adults fluctuates relatively steadily, while the income Gini coefficient of middle-aged and young rural households shows a fluctuating downward trend, suggesting that the ageing of the rural population does not exacerbate income inequality among rural households.

Note: The figure shows the Gini coefficient of household income for different average age groups. Rural households are divided into young rural households (in red), middle-aged rural households (in green), and older rural households (in orange). The classification criteria for young, middle-aged, and older rural households are the average age of household members ≤44 years old, 45–64 years old, and ≥65 years old, respectively.

The decoupling index between population ageing and income inequality

The decoupling between the Gini coefficient and population ageing can be expressed as elasticity (i.e., the ratio of the percentage change in the Gini coefficient to the percentage change in the aged population) less than 1. Figure 6 shows the decoupling index between rural population ageing and income inequality (i.e., Gini coefficient) in China at the regional level from 2003 to 2020. In most years, rural areas at the regional level achieve decoupling between population ageing and income inequality.

The data shows that the decoupling index in most years (68.38%) is negative, and the Gini coefficient in rural areas has achieved strong decoupling from population ageing. However, there are also some years with decoupling indices ranging from 0 to 1 (averaging 16.24%), and only a few years have decoupling indices exceeding 1 (averaging 15.38%). Specifically, out of the 18 years, 13 are in a strong decoupling state in North China; 12 in Northeast and Southwest China; 11 in East, Middle and Northwest China; and 10 in South China. The strong decoupling state accounts for the majority in all seven regions, indicating that with the gradual deepening of population ageing in rural areas, income inequality has not increased but has mainly manifested a decreasing state.

Decomposition of income inequality

Furthermore, we classify rural households’ income into four categories based on their sources of income, including business, wage and salary, transfer, and property, and decompose the Gini coefficients of rural households’ income in 2003 and 2020. Table 3 shows the result of decomposing the Gini coefficients of household income in 2003 and 2020 based on income sources. From 2003 to 2020, there are significant changes in the source of household income (Sk) for rural residents, mainly manifested in the increase in the proportion of wage income from 22.9% in 2003 to 50.9% in 2020, while the proportion of business income decreases from 65.2% in 2003 to 34.5% in 2020. The Gini coefficient of total income for rural residents in China decreases from 0.438 to 0.392, and the Gini coefficient (Gk) of different income sources exceeds the Gini coefficient of total income.

Among the four sources, the Gini coefficient of business income increases from 0.579 to 0.762, the Gini coefficient of property income, transfer income as well as wage and salary income decreases. The data shows that the inequality of business income and wage and salary income dominates the total income inequality of rural households. Although the proportion of business income inequality in the total income inequality decreases, it still accounts for 46.3% in 2020. The proportion of wage income inequality in the total income inequality increases from 18.4% in 2003 to 47.8% in 2020. The increase in income from different sources has different directional effects on the inequality in the total income of rural households. Specifically, an increase in business income causes a positive change in the Gini coefficient of total income, with the change rate expanding from 0.05% in 2003 to 0.12% in 2020, indicating that the growth of business income is more favourable for the wealthy and can exacerbate income inequality among rural residents. In contrast, the increase in wage income, property income, and transfer income in 2020 causes a negative change in the Gini coefficient of total income, indicating that the growth of these three types of income is more beneficial to the poor, and can effectively alleviate income inequality.

To deeply analyse the relationship between rural population ageing and income inequality, we once again classify rural households’ income into four categories. We explore the effects of rural population ageing and different sources of income on total income inequality in different regions. Figure 7 shows the relationship between the ageing population in rural China from 2003 to 2020 and the marginal impact of different sources of income on the Gini coefficient of total income. The data shows that from 2003 to 2020, with the deepening of ageing, the promoting effect of business income on total income inequality strengthened. The inhibitory effect of increasing property income on income inequality remains basically unchanged, and the inhibitory effect of wage and salary income on total income inequality is weakening, while the inhibitory effect of increasing transfer income on income inequality becomes increasingly evident.

Decomposition of income inequality change

Table 4 shows the composition of sources that influence the change of income inequality of rural residents in China. The results show that from the perspective of total effect, the structural effect and the combined effect are positive, while the concentrated effect is negative, and the absolute value of the structural effect is greater than those of combined effect and the concentrated effect. This shows that the income structure effect of rural residents in China has played a role in reducing the Gini coefficient during 2003–2020. In terms of structural effect, the increase of wage and salary income share enlarges the Gini coefficient by nearly 0.1, and the decrease of business income share reduces the Gini coefficient by nearly 0.15. In terms of concentrated effect, the concentration rate index of business income increases from 0.474 to 0.526, which enlarges the Gini coefficient by 0.034. The concentration rate index of transfer income falls from 0.420 to 0.129, reducing the Gini coefficient by 0.031; Because the two effects cancel each other, the concentrated effect of Gini coefficient is very small.

Discussion

This paper analyses the characteristics of population ageing and income inequality in rural China. According to the results of the national rural ageing rate, the ageing degree of China’s rural population continues to rise from 2003 to 2020, and in 2019, it entered a stage of moderate ageing as a whole. The results show that the Gini coefficient of the surveyed rural households has a relatively stable change and the Gini coefficients in various regions of China has shown a certain degree of decline, which means that income inequality among rural residents is being alleviated. The spatial autocorrelation of population ageing and income inequality is examined, and the result shows that the spatial autocorrelation has disappeared since 2013.

The accelerating ageing process in rural areas of China is the result of multiple interwoven factors, such as economy, society, and culture. The possible reasons are, first, the impact of baby boom. Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, it has experienced three significant baby booms, which occurred in the 1950s, from 1962 to 1976, and from 1986 to 1990, bringing about three “shock waves” of population ageing. Especially in recent years, the population born during the second baby boom is gradually entering old age, which significantly exacerbates the ageing process in China.

Second, the impact of the long-term implementation of the family planning policy. After the implementation of the family planning policy which was established to regulate population in 1982, China’s birth rate showed an overall downward trend, with the proportion of newborn babies in the total population declining (Wang et al., 2017). With the improvement in social and economic development levels, Chinese people’s awareness of eugenics has grown, so even though the Chinese government decided to fully liberalize the two-child policy in 2015, the birth rate does not show a significant continuous increase.

Third, the health industry continues to develop. China is continuously improving its medical and health service system, establishing a three-level rural medical and health service network led by county-level hospitals and based on township and village clinics in rural areas. The continuous improvement in the medical and health system and the establishment of a new rural cooperative medical system that focuses on comprehensive planning for major illnesses and claims for minor illnesses effectively solve the problems of difficult and expensive medical treatment for rural households.

Fourth, there is a significant transfer of the young and middle-aged rural labour force. Since China implemented the reform and opening-up in 1978, the increasing opportunities for urban migrant workers and higher income levels have given rise to a large labour market for migrant workers, with a large amount of young and middle-aged surplus labours shifting from rural to urban areas. In 2014, China fully relaxed the restrictions on settling in established towns and small cities, continuously expanding the coverage of basic public services, significantly increasing the probability of rural young and middle-aged labour transferring to cities.

The research results indicate that with the gradual deepening of population ageing in rural areas, the issue of income inequality in most rural areas of China is gradually easing, which contradicts existing empirical findings. It is generally believed that the older adults is more likely to exit the labour market, leading to a decrease in average household income, thereby exacerbating income inequality (Hwang et al., 2021; Lindert, 1978). However, the phenomenon of income inequality in rural areas of China has not intensified with the deepening of ageing, mainly due to a series of policies introduced to prevent aggravating the problem of getting old before getting rich.

In 2009, to address the issue of older adults care for rural residents, China implemented a new rural social pension insurance policy that benefits people’s livelihoods. According to the principle of combining basic pension and personal account pension, the central or local government provides full subsidies for basic pension. When rural households reach the age of 60, they can receive a monthly basic pension of at least 55 yuan, which improves the income level of older adults in rural areas. In 2015, China proposed winning the battle against poverty, continuously improving the rural minimum living guarantee system, and focusing on strengthening the construction of infrastructure including transportation, water conservancy, electricity, and basic public service systems, such as education, healthcare, housing, and social security, in impoverished areas. This has improved the production and quality of life of rural older adults.

In 2017, China proposed the implementation of the rural revitalization strategy, which continuously tilts financial funds towards rural areas and promotes the continuous development of various rural undertakings. Since the proposal of the rural revitalization strategy, the Chinese government has continuously implemented a series of policy measures to support the development of rural industries, promoting the stable development of agricultural production and the continuous extension of the agricultural industry chain. Factors such as funds, talent, and technology have flowed to agriculture, providing important opportunities for older adults in rural areas to engage in agricultural production and operation activities and increase their business income. Moreover, the development of new industries, such as rural tourism and rural e-commerce, have provided certain nonagricultural employment opportunities for older adults, greatly increasing their wage income.

Moreover, 31 provinces (autonomous regions, municipalities) in China have established an older adults allowance system, and the distribution standards are classified and graded according to the age of the recipients, the subsidy level, and the local subsistence allowance standards. It is adjusted in a timely manner according to the local economic and social development situation. In addition, China has established beneficial policies such as family subsidies for impoverished rural households and pension insurance for landless rural households, which have significantly helped to alleviate income inequality.

This paper also finds that the ageing of the rural population can narrow the income gap through wage and salary income, property income, and transfer income. However, with the deepening of population ageing, the inhibitory effect of wage and salary income on total income inequality is weakening, while the inhibitory effect of increasing transfer income on income inequality became increasingly evident. The following presents explanations for these findings. From the perspective of wage and salary income, the comprehensive promotion of rural revitalization has led to the rapid development of rural industries, which to some extent lowers the age threshold for rural older adults to engage in nonagricultural employment and obtain wage income locally. However, due to limited resource endowments, the development of rural industries cannot provide job opportunities for all rural households with older adults, which limits the further inhibitory effect of wage and salary income on income inequality.

From the perspective of property income, China has comprehensively promoted the registration and certification of rural land rights. These policies grant rural households the ability to possess, use, benefit from and transfer contracted land and to mortgage and guarantee contracted management rights, which encourages and guides the orderly transfer of land contracted management rights and increases the land property income of rural households with older adults. From the perspective of transfer income, with the continuous enhancement of China’s economic strength, the tilt of financial funds towards rural households with older adults is also increasing. The increasing basic pension and older adults allowances have led to a continuous increase in transfer income for rural households with older adults, thereby narrowing the income gap.

Conclusion and implications

The population ageing and income inequality are social issues that currently require special attention worldwide. Studies have demonstrated the impact of population ageing on income inequality (Paglin, 1975; Shirahase, 2015), but have largely overlooked China. This paper uses nationally representative rural household data collected by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China from 2003 to 2020 to explore the relationship between the intensification of population ageing and income inequality in rural China at a micro level, which is a powerful supplement to existing research. The study employs the decoupling index and decomposition method and the results show that the issue of income inequality has not intensified with the deepening of ageing.

Based on the research results of this paper, we suggest the following measures to further alleviate the issues of population ageing and income inequality in rural China. First, policies should aim to moderately extend maternity leave and increase the level of parental allowance distribution. The government should accelerate the development of infant and 0–3-year-old child care and custody services, establish reasonable and unified service standards, and improve the service quality and level. Additionally, the government should further standardize the charging standards for basic public services, such as preschool education, compulsory education, social security, and public health. Increasing financial investment, creating a public cost-sharing mechanism for child-rearing, and reducing child rearing costs, so as to enhancing families’ fertility willingness.

Second, the production and living environment in rural areas should be improved to attract the return of young and middle-aged rural labours. The construction of infrastructure, such as rural roads, water use, and networks, and public services, such as education, healthcare, and social security should be strengthened to coordinate urban‒rural development and narrow the urban‒rural gap. Efforts should be made to expand employment channels for rural residents through cooperation among governments, enterprises, social organizations, and other stakeholders. And promoting the local employment and entrepreneurship of young and middle-aged rural labours through e-commerce platforms.

Third, the long-term care system should be improved to address the difficulties of older adults care in rural areas. In response to the current irreversible trend of rural population ageing, the role of social security as a shock absorber should be fully utilized, and a multilevel long-term care system should be established. The development of commercial pension insurance should be accelerated, the combination of social insurance and family pension should be encouraged and guided, and the older adults income security system should be improved. The government should increase policy support for industries geared toward older adults, provide preferential support from various aspects such as finance, taxation and land, and encourage various entities to participate in rural older adults care.

Fourth, the government should take multiple measures to improve the income level of rural older adults. Although the income inequality of the older adults in rural China is currently easing, the issue cannot be ignored. We should accelerate the construction of a long-term mechanism to alleviate the income inequality of rural residents. Increasing the business income of rural households with older adults by improving the level of agricultural mechanization and intelligence, and promoting the development of entire process of agricultural production trusteeship service. The government should implement an active ageing strategy, increase the labour participation rate of older adults, and increase human capital investment in the future population of older adults, thereby increasing their wage income. We should deepen the reform of the rural land system, further standardize the transaction market for the transfer of rural land management rights, and improve the efficiency and level of rural land transfer. The mechanism for balancing economic interests between regions should be established, by means of improving the fairness and efficiency of public finance and social security transfer payments.

In addition to the research findings and conclusions mentioned above, this paper inevitably faces some research limitations. One key limitation is that the data used in this paper only extends to 2020 due to availability, which means that recent data is lacking. Consequently, it is not possible to analyze the changes in farmers’ income before and after the COVID-19 epidemic. The impact mechanism of population ageing on income inequality among farmers is complex and multifaceted, involving economic, social, and cultural dimensions. This complexity makes it challenging to fully capture the interactions and dynamic changes among these factors. Future research could broaden the scope by comparing urban and rural areas in China or rural areas across different countries, thereby enriching the theoretical understanding of the relationship between population ageing and income inequality.

Data availability

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because this is internal agency data. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the Research Center on the Rural Economy (RCRE) of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China.

References

Aghion P, Akcigit U, Bergeaud A, Blundell R, Hemous D (2019) Innovation and top income inequality. Rev Econ Stud 86(1):1–45

Alam MS, Paramati SR (2016) The impact of tourism on income inequality in developing economies: does Kuznets curve hypothesis exist? Ann Tour Res 61:111–126

Ali I, Attiaoui I, Khalfaoui R, Tiwari AK (2022) The effect of urbanization and industrialization on income inequality: an analysis based on the method of moments quantile regression. Soc Indic Res 161(1):29–50

Almas I, Cappelen AW, Lind JT, Srensen E, Tungodden B (2011) Measuring unfair (in)equality. J Public Econ 95:488–499

Anselin L (2019) Global spatial autocorrelation (2): Bivariate, differential and EB rate Moran scatter plot. https://geodacenter.github.io/workbook/5b_global_adv/lab5b.html#bivariate-spatial-correlation---a-word-of-caution

Autor DH (2014) Skills, education, and the rise of earnings inequality among the “other 99 percent”. Science 344:843–851

Benjamin D, Brandt L, Rozelle S (2000) Aging, wellbeing, and social security in rural northern China. Popil Dev Rev 26:89–116

Bhattacharya D (2007) Inference on inequality from household survey data. J Econ 137(2):674–707

Birnbaum S, De Wispelaere J (2021) Exit strategy or exit trap? Basic income and the ‘power to say no’ in the age of precarious employment. Socio-Econ Rev 19(3):909–927

Bishop JA, Formby JP, Smith WJ (1997) Demographic change and income inequality in the United States, 1976-1989. South Econ J 64(1):34–44

Böhm MJ, Gregory T, Qendrai P, Siegel C (2021) Demographic change and regional labour markets. Oxf Rev Econ Pol 37(1):113–131

Cai F (2012) The coming demographic impact on China’s growth: The age factor in the Middle-Income Trap. Asian Econ Pap 11(1):95–111

Cameron LA (2000) Poverty and inequality in Java: examining the impact of the changing age, educational and industrial structure. J Dev Econ 62(1):149–180

Card D, Cardoso AR, Kline P (2016) Bargaining, sorting, and the gender wage gap: Quantifying the impact of firms on the relative pay of women. Q J Econ 131:633–686

Chen LK (2019) Integrated care for older people: solutions to care fragmentation. Aging Med Health 10:94–95

Cuaresma JC, Loichinger E, Vincelette GA (2016) Aging and income convergence in Europe: a survey of the literature and insights from a demographic projection exercise. Econ Syst 40(1):4–17

Dannefer D (2003) Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: cross-fertilizing age and social science theory. J Gerontol B-Psychol 58(6):S327–S337

Davies J, Hoy M (1995) Making inequality comparisons when Lorenz curves intersect. Am Econ Rev 85(4):980–986

Davis B, Winters P, Carletto G, Covarrubias K, Quiñones EJ, Zezza A, Stamoulis K, Azzarri C, Digiuseppe S (2010) A cross-country comparison of rural income generating activities. World Dev 38(1):48–63

Deaton AS, Paxson CH (1997) The effects of economic and population growth on national saving and inequality. Demography 34:97–114

Deaton AS, Paxson CH (1998) Aging and inequality in income and health. Am Econ Rev 88(2):248–253

Delbosc A, Currie G (2011) Using Lorenz curves to assess public transport equity. J Transp Geogr 19(6):1252–1259

Dong X, Milholland B, Vijg J (2016) Evidence for a limit to human lifespan. Nature 538:257–259

Dong ZQ, Tang CQ, Wei XH (2018) Does population aging intensify income inequality? Evidence from China. J Asia Pac Econ 23(1):66–77

Duignan L, Dutton DJ (2024) The association between allostatic load and guaranteed annual income using the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging: a cross-sectional analysis of the benefits of guaranteed public pensions. Health Policy 143:105054

Dynan KE, Edelberg W, Palumbo MG (2009) The effects of population aging on the relationship among aggregate consumption, saving, and income. Am Econ Rev 99(2):380–386

Ebbinghaus B (2021) Inequalities and poverty risks in old age across Europe: The double-edged income effect of pension systems. Soc Policy Admin 55(3):440–455

Feng ZL, Wu B (2023) Embracing challenges for population aging in China: Building scientific evidence to inform long-term care policymaking and practice. J Aging Soc Policy 35(5):543–553

Gastwirt JL (1972) Estimation of Lorenz-curve and gini-index. Rev Econ Stat 54(3):306–316

Giorgi GM, Gigliarano C (2017) The Gini concentration index: a review of the inference literature. J Econ Surv 31(4):1130–1148

Glawe L, Wagner H (2020) The middle-income trap 2.0: The increasing role of human capital in the age of automation and implications for developing Asia. Asian Econ Pap 19(3):40–58

Gomez R, Foot DK (2003) Age structure, income distribution and economic growth. Can Public Pol 29:S141–S161

Hammer B, Spitzer S, Prskawetz A (2022) Age-specific income trends in Europe: the role of employment, wages, and social transfers. Soc Indic Res 162(2):525–547

Harper S (2014) Economic and social implications of aging societies. Science 346:587–591

Hartmann D, Guevara MR, Jara-Figueroa C, Aristaran M, Hidalgo C (2017) Linking economic complexity, institutions, and income inequality. World Dev 93:75–93

Hidalgo CA (2021) Economic complexity theory and applications. Nat Rev Phys 3:92–113

Hungerford TL (2020) The course of income inequality as a cohort ages into old-age. J Econ Inequal 18(1):71–90

Hwang S, Choe C, Choi K (2021) Population ageing and income inequality. J Econ Ageing 20:100345

Jamil AM, Law SH, Khair-Afham MS, Trinugroho I (2024) Financial inclusion and income inequality in developing countries: the role of aging populations. Res Int Bus Financ 67:102110

Kakwani NC (1977) Applications of Lorenz curves in economic-analysis. Econometrica 45(3):719–727

Karunaratne HD (2000) Age as a factor determining income inequality in Sri Lanka. Dev Econ 38(2):211

Khan AR, Riskin C (1998) Income and inequality in China: composition, distribution and growth of household income, 1988 to 1995. China Q 154:221–253

Kim C, Kim AT (2024) Aging and the rise in bottom income inequality in Korea. Res Soc Strat Mobil 89:100882

Kim JI, Kim G (2017) Socio-ecological perspective of older age life expectancy: Income, gender inequality, and financial crisis in Europe. Glob Health 13:58

Kreps JM (1970) Economics of aging: Work and income through lifespan. Am Behav Sci 14(1):81–90

Kuznets S (1955) Economic growth and income inequality. Am Econ Rev 45:1–28

Lerman RI, Yitzhaki S (1985) Income inequality effects by income source: a new approach and applications to the United States. Rev Econ Stat 67:151–156

Li CZ, Li XL, Wang JX, Feng TC (2023) Impacts of aging agricultural labor force on land transfer: an empirical analysis based on the China Family Panel Studies. Land 12(2):295

Li Q, Huang JK, Luo RF, Liu CF (2013) China’s labor transition and the future of China’s rural wages and employment. China World Econ 21(3):4–24

Li SY, Lin SL (2016) Population aging and China’s social security reforms. J Policy Model 38(1):65–95

Lindert PH (1978) Fertility and scarcity in America. Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ

Liu JZ, Fang YA, Wang G, Liu BC, Wang RR (2023) The aging of farmers and its challenges for labor-intensive agriculture in China: a perspective on farmland transfer plans for farmers’ retirement. J Rural Stud 100:103013

Liu Y, Chen LM, Lv LT, Failler P (2023) The impact of population aging on economic growth: a case study on China. Aims Math 8(5):10468–10485

Mahal A, McPake B (2017) Health systems for aging societies in Asia and the Pacific. Health Syst Reform 3:149–153

Marois G, Bélanger A, Lutz W (2020) Population aging, migration, and productivity in Europe. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:7690–7695

Milanovic B (2016) Income inequality is cyclical. Nature 537:479–482

Min S, Waibel H, Huang JK (2017) Smallholder participation in the land rental market in a mountainous region of Southern China: Impact of population aging, land tenure security and ethnicity. Land Use Policy 68:625–637

Muhammad T, Srivastava S, Hossain B, Paul R, Sekher TV (2022) Decomposing rural-urban differences in successful aging among older Indian adults. Sci Rep 12:6430

Oeppen J, Vaupel JW (2002) Broken limits to life expectancy. Science 296:1029–1031

Paglin M (1975) The measurement and trend of inequality: a basic revision. Am Econ Rev 65:598–609

Pfeffer FT, Waitkus N (2021) The wealth inequality of nations. Am Socio Rev 86(4):567–602

Prus SG (2000) Income inequality as a Canadian cohort ages: an analysis of the later life course. Res Aging 22(3):211–237

Ren CC, Zhou XY, Wang C, Guo YL, Diao Y, Shen SS, Reis S, Li WY, Xu JM, Gu BJ (2023) Ageing threatens sustainability of smallholder farming in China. Nature 616:96–103

Rowe JW (2019) Challenges for middle-income elders in an aging society. Health Aff 38(5):865–867

Saez E, Zucman G (2016) Wealth inequality in the United States since 1913: evidence from capitalized income tax data. Q J Econ 131:519–578

Shaik MR, Goh SK, Wong KN, Law CH (2024) Does population aging coexist with income inequality in the long run? Evidence from selected Asia-Pacific countries. Econ Syst 48(1):101149

Shirahase S (2015) Income inequality among older people in rapidly aging Japan. Res Soc Stratif Mobil 41:1–10

Shorrocks AF (1982) Inequality decomposition by factor components. Econometrica 50(1):193–211

Shrestha LB (2000) Population aging in developing countries. Health Aff 19(3):204–212

Stark O, Taylor JE, Yitzhaki S (1986) Remittances and inequality. Econ J 96:722–740

Sulemana I, Nketiah-Amponsah E, Codjoe EA, Andoh JAY (2019) Urbanization and income inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustain Cities Soc 48:101544

Tapio P (2005) Towards a theory of decoupling: degrees of decoupling in the EU and the case of road traffic in Finland between 1970 and 2001. Transp Policy 12:137–151

The National Bureau of Statistics of China (2021) Answering journalists’ questions on the press conference of “China’s Epic Journey from Poverty to Prosperity”. https://www.stats.gov.cn/xxgk/jd/zcjd/202109/t20210930_1822661.html

The National Bureau of Statistics of China (2021) China population census yearbook 2020. https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/pcsj/rkpc/7rp/zk/indexch.htm

The National Bureau of Statistics of China (2023) China statistical yearbook 2023. https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/2023/indexch.htm

The National Bureau of Statistics of China (2024) Statistical bulletin of the People’s Republic of China on national economic and social development for 2023. https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202402/t20240228_1947915.html

Tu WJ, Zeng XW, Liu Q (2022) Aging tsunami coming: the main finding from China’s seventh national population census. Aging Clin Exp Res 34(5):1159–1163

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2022) World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results. United Nations: New York, NY

Vaupel JW (2010) Biodemography of human ageing. Nature 464:536–542

Wan G, Zhang X, Zhao M (2022) Urbanization can help reduce income inequality. npj Urban Sustain 2(1):1–8

Wang F, Zhao LQ, Zhao Z (2017) China’s family planning policies and their labor market consequences. J Popul Econ 30(1):31–68

Wang Y, Zhou CC (2020) Promoting social engagement of the elderly to cope with aging of the Chinese population. Biosci Trends 14(4):310–313

Woo J (2017) Designing fit for purpose health and social services for ageing populations. Int J Env Res Pub He 14(5):457

World Health Organization (2022) Ageing and Health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health

Xie Y, Zhou X (2014) Income inequality in today’s China. P Natl Acad Sci USA 111(19):6928–6933

Zhang KX, Kan CX, Luo YH, Song HW, Tian ZH, Ding WL, Xu LF, Han F, Hou NN (2022) The promotion of active aging through older adult education in the context of population aging. Front Public Health 10:998710

Zhang NJ, Guo M, Zheng XY (2012) China: Awakening giant developing solutions to population aging. Gerontologist 52(5):589–596

Zhong H (2011) The impact of population aging on income inequality in developing countries: evidence from rural China. China Econ Rev 22(1):98–107

Acknowledgements

Support for this research is provided by the National Social Science Foundation of China (22BJY218), the Association for Science and Technology Think Tank Youth Talent Program of China (2022-257), the Postdoctoral Science Foundation of China (2020M670575 and 2020T130714); and the Special Funds for the Taishan Scholars Project, National Social Science Fund of China (24CRK035) (to JW).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MG’s tasks on the article development: conceiving the project and designing the study, data curation, writing-reviewing and editing. FJ’s tasks on the article development: writing the manuscript, writing-reviewing and editing. JWW’s tasks on the article development: data analysis, writing and supervision. BW’s tasks on the article development: preparing the data. All authors provided feedback on the manuscript and data analyses during the process of finalizing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, M., Jiang, F., Wang, J. et al. Population ageing and income inequality in rural China: an 18-year analysis. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1605 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04110-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04110-1

This article is cited by

-

How Population Aging Undermines Rural Community Sustainability: Evidence from 304 Chinese Communities

Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy (2026)

-

Oral health and nutrition: addressing disparities in socioeconomically disadvantaged older adults in rural China

BMC Public Health (2025)