Abstract

This study conducts a comparative analysis of grounding strategies employed in French and Indonesian narrative discourse. Utilizing both qualitative and quantitative methodologies, the research draws upon a corpus of French and Indonesian novels to examine the linguistic mechanisms utilized to establish grounding in these languages. This research questions the different markers of grounding in French and Indonesian narrative discourses, the types of grounding meanings, the role of culture in grounding, and what elements can strengthen grounding. The results of the textual analysis reveal that French employs the use of tenses, specifically the passé simple and imparfait (past tenses), to convey grounding, whereas Indonesian utilizes affixes, specifically the “me(N)-” and “di-” prefixes, for the same purpose. Further, the analysis illustrates that the “me(N)-” affix can be utilized to express both backgrounding and foregrounding, while the “di-” affix is restricted to foregrounding. Additionally, Indonesian also employs the use of third-person singular pronouns—“dia” and “ia”—to enhance grounding. The contextual analysis also highlights that in Indonesian narrative discourse, there is a tendency to repeat self-names as a form of politeness. This conclusion applies to languages that use tenses (e.g., French and English) as grounding markers and applies to languages that use affixes for grounding markers (e.g., Indonesian and Malay).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There exists a distinction between the grounding markers employed in French and Indonesian narrative discourses. Specifically, French narrative discourse utilizes tenses as grounding markers, whereas Indonesian narrative discourse employs diatheses for this purpose (Baryadi, 2002). This research aims to provide a deeper understanding of the linguistic mechanisms used to establish grounding in these languages, and how they differ from one another. It means that it not only provides an understanding of grounding from a linguistic perspective, but also a cultural perspective. There are two types of diatheses, namely accusative and ergative diatheses. In languages that possess an accusative typology, the active diathesis serves as the basic structure, whereas the passive diathesis functions as a derivative structure. In contrast, in languages that possess an ergative typology, the ergative diathesis serves as the basic structure, with the antipassive diathesis functioning as its derivative structure (Artawa & Purnawati, 2020). In Malay and Indonesian, the ergative diathesis serves as a foreground marker, while the active and passive diatheses function as background markers (Baryadi, 2002).

Research on grounding has been extensively conducted by scholars in the field. To date, analysis of grounding has exhibited four tendencies, namely (1) tense, aspect, and diathesis, (2) sequence pattern, (3) marker, and (4) translation. The first tendency of grounding research based on aspect, tense, and diathesis markers has been conducted by scholars such as Hopper (1979), Fleischman (1985), Kaswanti (1989), Chui (2003), Sajarwa (2013), Sutanto (2014), Ahangar & Rezaeian (2017). The second tendency of grounding analysis based on sequence patterns has been conducted by scholars such as Li (2014, 2018). The utilization of sequence patterns as a means of revealing grounding in narrative discourse is demonstrated in the Chinese language, as highlighted in the following statement:

“I have attempted here to contribute a description of the grounding functions of some basic clause types in Chinese narrative. I hope to have made a convincing case for the following two points: (a) Constituent order and clause structure are an important means to indicate event versus state situation types, and (b) this feature, in turn, has important implications for grounding indications in narrative discourse” (Li, 2018).

The third tendency of grounding analysis without markers has been conducted by scholars such as Gooden (2008) when studying Caribbean English Creoles. The fourth tendency of grounding analysis with translation has been conducted by scholars such as Urzha (2018) when analyzing the translation of grounding into the Russian language.

There are also several studies that discuss grounding in various areas. In terms of literature, Soni et al. discussed grounding characters in narrative texts and concluded that grounding characters allows one to measure the elements of narrative and the degree to which mobility of space in narrative is bound with gender (Soni, Sihra, Evans, Wilkens, & Bamman, 2023). Jiayang et al. analyzed grounding in texts in which there is also the use of machines (Jiayang et al., 2024), while Wang et al. analyzed Panoptic Narrative Grounding, a formulation of the natural language visual grounding problem. These two grounding studies that can link text, visual images, and machines show that grounding analysis is not only possible in the domain of language research (Wang, Ji, Zhou, Wu, & Sun, 2023).

This research differs from previous studies in that it utilizes not only diathesis but also pronominal markers as tools for grounding in the Indonesian language. Additionally, this study also takes into account cultural context. From the above discussion, questions arise regarding the different markers of grounding in French and Indonesian narrative discourses, the types of grounding meanings, the role of culture in grounding, and what elements can strengthen grounding. Therefore, this study delves into a comprehensive examination of grounding in French and Indonesian narrative discourses through textual and contextual analysis. This research also aims to challenge the assertion (Hopper, 1979) that in the Malay language, the passive “di-” form is used as a foreground marker, and the affix “me-” is used as a background marker. The results of this study will complement studies by Kaswanti (1989), Hoed (1992), and Sutanto (2014). Similarly, research conducted by Kaswanti, Hoed, and Sutanto concluded that the affix “me-“ is a background marker. However, those conclusions are not all accurate because the result of this research shows that the affix “me-“ is also used for foreground. The difference between affix “me-“ for foreground and background is what has not been discussed. In other words, this research corrects the results of those studies and complements them.

With many grounding-themed studies conducted, this study provides novelty by analyzing grounding in novels from the linguistic and cultural side. Thus, it shows novelty in terms of analytical focus. This research posits that in the era of globalization, where communication and human mobility are at an all-time high, a linguistic study of cross-language comparison is necessary. Specifically, comparing the groundings in French and Indonesian will be beneficial for the development of translation science and language learning. This approach aligns with the claim (James, 1980) that contrastive analysis can be used as a basis for translation analysis and language learning. The study focuses on the grounding of French and Indonesian from both a textual and a contextual perspective. The textual analysis examines the linguistic markers of grounding, while the contextual analysis examines grounding from a cultural perspective. The combination of textual and contextual analysis is hoped to result in a more comprehensive study.

Literature review

Language grounding

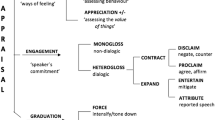

Grounding is a concept that is widely studied across various interdisciplinary fields such as psychology, cognitive science, literary criticism, graphic design, and linguistics (Li, 2018). The origins of the concept can be traced back to Harnad’s introduction of the idea of symbol grounding in 1990. According to Harnad, the grounding of any word in our minds serves as a bridge between the words in written text and their corresponding external references (Zhang & Wang, 2011). This concept of language grounding posits that language acquisition is shaped by one’s experiences in the physical world (Colas, Akakzia, Oudeyer, Chetouani, & Sigaud, 2020), as opposed to the traditional semantic model, which relies on linguistic knowledge. A seminal study (Hopper & Thompson, 1980) suggests that the linguistic features that distinguish between foreground (materials that supply the main points of discourse) and background (part of the discourse that contributes to the objective of the narrator but does little to support/strengthen it) are referred to as “grounding.”

The concept of language grounding, as articulated by Zhang & Wang (2011), pertains to the relationship between linguistic expressions and external physical stimuli, such as visual information. This field of study is rooted in the cognitive, communicative, and psychological foundations of language (Li, 2018). Li contends that the examination of cross-linguistic grounding phenomena may shed light on the universal features of language that facilitate human interaction and the documentation of events, entities, and interactions in the physical world. She also posits that cross-linguistic studies on grounding suggest that the semantic features of grounding tend to be universal in nature, with foregrounded clauses in narrative discourse typically narrating dynamic, complete, and actual past events. Li also notes that the ongoing exploration of language grounding continues to inspire a wealth of research, including studies focused on grounding in specific languages, second-language discourses, and fields related to cognition. However, the study only explained background and foreground from the linguistic side without involving the cultural side. Given the fact that language and culture are inseparable, this study fills the gap by analyzing grounding from a cultural perspective.

Narrative discourse

Narrative discourse, as defined by Elson (2012), is “a lens that focuses attention on a particular combination of events that transpire in a constructed world.” Narratives may depict events that correspond to reality, such as news articles, or they may take the form of fiction in which elements from the real world are borrowed to create an alternate reality (Elson, 2012). According to van Krieken, Sanders, & Sweetser (2019), a significant proportion of human communication is centered around narratives and evaluations of events that occurred prior to or subsequent to the communication itself. Various studies highlighted that narrative discourse is largely dependent on language and genre characteristics, for example government policy. Such as research by Wongnuch et al. (2022) regarding narratives of structural and cultural violence that occurred among HIV/Aids sufferers in Chiang Rai, Thailand. However, as suggested by van Krieken et al. (2019), there are additional factors at play, such as (1) the physical space in reality that belongs to the narrator and to the recipient (in any narrative with conversational markers); (2) a non-physical space, namely an anticipated space that corresponds to the time the narration is assumed to take place, which does not exactly coincide with the time of reading (in historical and news narratives), or (3) an imaginary non-physical space with the narrator and the message recipient as participants that share some similarities in terms of reciprocal understanding regarding time hypothesis (in fictional narratives).

Narratives, as a means of expression, possess the ability to serve various functions depending on the context and intended purpose. According to Elson (2012), narratives are often utilized to convey and derive shared cultural values, particularly those related to what is deemed esthetically pleasing and morally commendable, allowing individuals to position their own values and actions in relation to these shared ideals. However, Elson notes that narratives can also challenge and subvert established norms and conventions, thereby promoting change and transformation. Furthermore, Li (2018) highlights the suitability of narrative texts for studies on grounding, citing their clear distinctions between foregrounded and backgrounded elements, the temporal order present in narrative discourse, the realistic nature of foregrounded events, and the singularity of foregrounded incidents as key characteristics. Li’s research on background and foreground is beneficial in this study, and the narrative texts used in the current study are in the form of novels.

Text-context analysis

Text and context are inextricably linked in discourse, with each text being produced within a specific context. The definition of “text” varies, ranging from a narrow interpretation, such as “a canon of official documents,” to a broader interpretation, such as “cultural artifacts” (Bauer et al., 2014). Shen (2012) defines text as a combination of linguistic elements that conveys a complete idea in communication, while context refers to the elements that indicate its purpose in terms of field, tenor, and mode. Longman defines text as a general term that encompasses all examples of language use, which is the language generated by the act of communication (Shen, 2012). Hu Zhuanglin posits that text refers to natural language in a particular context, and although not limited by grammar, it is capable of expressing complete semantics (Shen, 2012).

The relationship between text and context is crucial in understanding the cultural ideologies that shape a text. Through the examination of context, one can gain insight into the function and origins of cultural ideologies (Lukin, 2017). The interdependence of text and context can be established through various means such as linguistic interpretation, cognitive analysis in relation to psychology, and an examination of the sociocultural context as used in sociology and anthropology (House, 2006). According to Mckee (2001), when analyzing a text, it is important to consider three levels of context: (1) the rest of the text, (2) the genre of the text, and (3) the wider public context in which the text is circulated. The more context that is identified, the greater the potential for a rational interpretation of the text. Thus, this analysis of this current study is beyond the text because it also emphasizes the cultural context.

Methods

This study utilizes data from three French novels and their Indonesian translations. The choice of novels is based on their narrative structure, which serves as a medium for language communication by conveying stories through language (Hoed, 1992). The three French novels used in this study are (1) Vendredi ou la Vie Sauvage (VVS), written by Tournier (1971) and published by Gallimard, (2) Madame Bovary (MB), written by Flaubert (2012) and published by Gallimard, and (3) Le Rocher de Tanios (RT), written by Maalouf (1993) and published by Grasser & Fasquelle. The translated versions of these novels are, respectively: (1) Kehidupan Liar (KL), translated by Ida Sundari Husen and published by Pustaka Jaya in 1992, (2) Nyonya Bovary (NB), translated by Winarsih Arifin and published by PT Dunia Pustaka Jaya in 1990, and (3) Cadas Tanios (CT), translated by Ida Sundari Husen and published by Yayasan Obor Indonesia in 1999.

The selection of the three novels as research data is based on several reasons. The novel Madame Bovary, written in the nineteenth century, is considered a literary revolution and is widely acknowledged and acclaimed not only in France but also in other countries in Europe, America, and Asia, including Indonesia (Sastriyani, 2011). Additionally, the novel Le Rocher de Tanios has garnered recognition through the receipt of the Prix Goncourt (1993) and the Grand Prix des Lecteurs (1996) awards. Furthermore, the Indonesian translation of the novel Vendredi ou la Vie Sauvage was awarded as the best-translated work by Yayasan Buku Utama in 1993 (Sastriyani, 2004).

This study adopted a mixed-methods approach, incorporating both qualitative and quantitative methodologies. A qualitative descriptive methodology was employed to examine grounding markers in French and Indonesian discourses. As posited by Creswell & Guetterman (2011), a qualitative research approach entails obtaining information from the subject of study in a general sense through the use of general questions, with data collection being realized through the subjective interpretation of the text. Subsequently, a qualitative interpretive methodology was employed to analyze the meanings of backgrounding and foregrounding. A comparative qualitative approach was implemented by comparing French and Indonesian grounding markers. Through this comparative methodology, similarities and differences of grounding markers, their meanings, and functions, in both French and Indonesian languages and cultures could be discerned. In essence, the comparative method was implemented through textual analysis. Furthermore, an interpretive methodology was utilized for contextual analysis, interpreting groundings from a cultural perspective. Additionally, a quantitative approach was employed to analyze the pattern in the utilization rate—shown in percentage—of each grounding marker. A quantitative analysis is used to determine the tendency of the number of translations of passé simple and imparfait into the affixes “me-“ and “di-“ in Indonesian.

The data collection for the narrative discourses in French and Indonesian consisted of 601 samples each. The data collection process involved: (1) reading the three novels in French and their translations in Indonesian, (2) identifying the data of groundings in both languages, and (3) documenting all data from both languages. To minimize subjectivity in the data analysis, the researcher sought input from native speakers of French and Indonesian. They provided feedback on the validity of the data and their cultural contexts. The subsequent phase was the data analysis, which entailed: (1) classifying the data based on the foregrounds and backgrounds found in both languages, (2) identifying instances of grounding markers in both languages, (3) deciphering the meanings of the groundings, (4) identifying the functions of the groundings in the narrative discourses, (5) comparing the groundings of both languages, and (6) analyzing the groundings from a cultural perspective.

Results

The analysis is divided into three parts: backgrounds in French and Indonesian, foregrounds in French and Indonesian, and Pronouns as Grounding Intensifiers. This division will make the analysis of foreground and background clear. The following are the detailed results:

Backgrounds in French and Indonesian

This section presents examples of backgrounds found in narrative discourses in French and Indonesian. As a constituent of narrative discourse, backgrounds serve to provide context and nuance to the foreground. The following analysis will detail the backgrounds identified in the data, along with their associated events and linguistic markers, and the change of the grounding markers when the French narrative discourses are translated into Indonesian (Tables 1 and 2).

For instances of backgrounds in narrative discourses in French and Indonesian, pay attention to datasets (1), (2), and (3) below.

Data set (1)

French (English):

-

a.

La plage était jonchée de poissons morts, de coquillages brisés et d’algues noires rejetés par les flots. (The beach was strewn with dead fish, broken shells and black seaweed washed up by the waves).

-

b.

A l’ouest, une falaise rocheuse s’avançait dans la mer et se prolongeait par une chaine de récifs. (To the west, a rocky cliff jutted out into the sea and was extended by a chain of reefs).

-

c.

C’était là que se dressait la silhouette de la Virginie avec ses mâts arrachés et ses cordages flottant dans le vent. (There stood the silhouette of La Virginie with its masts uprooted and its ropes flapping in the wind). (VVS: 13)

Indonesian (English):

-

a.

Di pantai bertebaran ikan-ikan mati, kerang-kerang yang pecah dan ganggang-ganggang laut yang dihepaskan gelombang. (The beach was strewn with dead fish, broken shells and black seaweed washed up by the waves).

-

b.

Di sebelah barat, tampak tebing karang yang menjorok ke laut, menyatu dengan gugusan karang. (To the west, a rocky cliff jutted out into the sea and was extended by a chain of reefs).

-

c.

Di sana menjulang sosok La Virginie dengan tiang-tiangnya yang patah. Tali temalinya melambai-lambai ditiup angin. (There stood the silhouette of La Virginie with its masts uprooted and its ropes flapping in the wind). (KL: 12)

Data set (2)

French (English):

-

a.

Charles, à cheval, envoyait un baiser à Emma. (Charles, on horseback, was blowing a kiss to Emma).

-

b.

Elle répondait par un signe. (She replied by waving her hand).

-

c.

Elle refermait la fenêtre. Il partait. (She closed the window. He left). (MB: 61)

Indonesian (English):

-

a.

Charles di atas punggung kudanya meniupkan ciuman pada Emma. (Charles, on horseback, was blowing a kiss to Emma).

-

b.

Emma membalasnya dengan lambaian, (She replied by waving her hand,)

-

c.

lalu menutup jendela. Charles pergi. (She closed the window. He left). (NB: 58)

-

a.

Data set (3)

French (English):

-

a.

Robinson ne cessait d’organizer et de civilizer son île et de jour en jour il avait davantage de travail et des obligations plus nombreuses. (Robinson kept organizing and civilizing his island, and day by day, he had more work and more obligations).

-

b.

Le matin par exemple, il commençait par faire sa toilette, (In the morning, for example, he began by taking a wash,)

-

c.

puis il lisait quelques pages de la Bible, (then he read a few pages of the Bible,)

-

d.

ensuite il se mettait au garde-à-vous devant la mât où il faisait ensuite monter le drapeau anglais. (then he stood at attention in front of the mast where he then raised the English flag).

-

e.

Puis avait lieu l’ouverture de la forteresse. (Then the opening of the fortress took place).

-

f.

On faisait basculer la passerelle par-dessus le fossé et on dégageait les issues bouchées par les rochers. (The footbridge was swung over the ditch and the exits blocked by the rocks were cleared).

-

g.

La matinée commençait par la traite des chèvres, (The morning began with the milking of the goats,)

-

h.

ensuite il fallait visiter la garenne artificielle que Robinson avait établie dans une clairière sablonneuse. (then it was necessary to visit the artificial warren that Robinson had established in a sandy clearing). (VVS: 51)

Indonesian:

-

a.

Robinson tak henti-hentinya mengatur dan membudayakan pulaunya. Dari hari ke hari pekerjaannya semakin bertambah, dan kewajiban-kewajiban pun kian banyak. (Robinson kept organizing and civilizing his island, and day by day he had more work and more obligations).

-

b.

Setiap pagi misalnya, mula-mula ia mempersiapkan diri, (In the morning, for example, he began by taking a wash)

-

c.

kemudian membaca beberapa halaman Injil, (then he read a few pages of the Bible)

-

d.

dan berdiri tegak dengan sikap hormat di depan tiang, lalu ia mengibarkan bendera Inggris. (then he stood at attention in front of the mast where he then raised the English flag).

-

e.

Setelah itu benteng dibuka. (Then the opening of the fortress took place).

-

f.

Kemudian ia menurunkan jembatan yang panjang di atas parit dan menyingkirkan batu-batu karang yang menghalangi jalan-jalan ke luar. (The footbridge was swung over the ditch and the exits blocked by the rocks were cleared).

-

g.

Kewajiban setiap pagi dimulai dengan memerah susu kambing, (The morning began with the milking of the goats,)

-

h.

lalu ia harus pergi ke tempat kelinci hutan hidup berkelompok, yang dibuatnya di daerah terbuka yang berpasir. (then it was necessary to visit the artificial warren that Robinson had established in a sandy clearing). (KL: 48)

-

a.

All three datasets comprising instances of backgrounds in narrative discourses, demonstrate that the imparfait tense is used for marking backgrounds in French. This is shown by the use of était, s’avançait, se prolongeait, and se dressait in data set (1); envoyait, répondait, refermait, and partait in data set (2); and cessait, avait, commençait, lisait, se mettait, faisait, avait, faisait, dégageait, commençait, fallait in data set (3). However, in Indonesian, the background markers used are verbs complemented by the affixes “me(N)-” and “ber-” as well as non-affixed verbs, with examples comprising menjulang, melambai-lambai, meniupkan, membalas, and menutup in data set (1); berdandan, tampak, and pergi in data set (2); and mengatur, mempersiapkan diri, membaca, mengibarkan, menurunkan, menyingkirkan, memerah, and pergi in data set (3).

Those three datasets illustrate how the type of grounding markers used in the French narrative discourses change in their Indonesian translation. The French language employs imparfait tense, whereas Indonesian utilizes affix.

In terms of meaning, the events in data set (1) are different from those in datasets (2) and (3). The events in datasets (1) express ‘states’ that are semantically characterized by static verbs, whereas the events in datasets (2) and (3) express ‘regular activities’ that are expressed through dynamic verbs.

Foregrounds in French and Indonesian

This section presents examples of foregrounds found in narrative discourses in French and Indonesian. The foreground is a crucial element of any narrative, providing important information and presenting the primary elements in accordance with the purpose of a story.

Instances of foregrounds in narrative discourse in French and Indonesian are provided in datasets (4) to (7) below.

Data set (4)

French (English):

-

a.

Robinson entreprit de fabriquer de la glu. (Robinson set out to make glue).

-

b.

Il dut pour cela raser presque entièrement un petit bois de houx qu’il avait repéré dès le debut de son travail. (To do this, he had to shave almost entirely a small holly grove that he had spotted at the start of his work).

-

c.

Pendant quarante-cinq jours, il débarrassa les arbustes de leur première écorce, et recueillit l’écorce intérieure en la découpant en lanières. (For forty-five days, he stripped the shrubs of their first bark, and collected the inner bark by cutting it into strips).

-

d.

Puis il fit longtemps bouillir dans un chaudron ces lanières d’écorce, et il les vit peu à peu se décomposer en un liquide épais et visqueux. (Then he boiled these strips of bark for a long time in a cauldron, and he saw them gradually decomposing into a thick and viscous liquid).

-

e.

Il répandit ce liquide encore brûlant sur la coque du bateau. (He spilled the still hot liquid on the hull of the boat). (VVS: 23)

Indonesian (English):

-

a.

Robinson membuat lem. (Robinson set out to make glue).

-

b.

Untuk itu, dia harus membabat hutan houx yang sudah ditemukannya sejak awal pekerjaannya. (To do this, he had to shave almost entirely a small holly grove that he had spotted at the start of his work).

-

c.

Selama empat puluh lima hari dia menguliti lapisan pertama kulit pepohonan itu dan mengambil lapisan bagian dalam dengan cara menyayatnya secara memanjang. (For forty-five days, he stripped the shrubs of their first bark, and collected the inner bark by cutting it into strips).

-

d.

Kemudian, dia merebusnya sayatan-sayatan itu dalam ketel. Sedikit demi sedikit kulit kayu tadi menjadi berlendir. (Then he boiled these strips of bark for a long time in a cauldron, and he saw them gradually decomposing into a thick and viscous liquid).

-

e.

Dia menuangkan cairan panas itu pada badan perahu. (He spilled the still hot liquid on the hull of the boat). (KL: 22)

Data set (5)

French (English):

Il s’y installa, recroquevillé sur lui même, remonta les genoux au menton, croisa les mollets, possa les mains sur les pieds. (He settled there, curled up on himself, raising his knees to his chin, crossed his calves, put his hands on his feet). (VVS: 55)

Indonesian:

Ia diam di situ ambal meringkuk, lututnya ditekuk sehingga menyentuh dagu, betisnya disilangkan, tangannya diletakkan di kaki. (He settled there, curled up on himself, raising his knees to his chin, crossed his calves, put his hands on his feet). (KL: 52)

Data set (6)

French (English):

-

a.

Emma eût, au contraire, désiré se mairier à minuit, aux flambeaux; mais le père Rouault ne comprit rien à cette idée. (Emma, on the contrary, would have liked to marry at midnight, illuminated by torchlight; but Father Rouault understood nothing of this idea).

-

b.

Il y eut donc une noce, où vinrent quarante trois personnes, où l’on resta seize heures à table qui recommença le lendemain et quelque peu les jours suivants. (And so, a wedding was conducted, to which forty-three people came, where we remained sixteen hours at the table, which recommenced the next day and somewhat the following days). (MB: 51)

Indonesian (English):

-

a.

Emma sebaliknya ingin mengikat perkawinan pada tengah malam, diterangi cahaya obor. Namun Bapak Rouault tidak mengerti pikiran semacam itu. (Emma, on the contrary, would have liked to marry at midnight, illuminated by torchlight; but Father Rouault understood nothing of this idea).

-

b.

Maka dilangsungkanlah pesta perkawinan yang dihadiri oleh empat puluh tiga undangan. Enam belas jam mereka dijamu di meja makan. Dilanjutkanlah esok harinya. Dan masih juga sedikit-sedikit pada hari-hari berikutnya. (And so, a wedding was conducted, to which forty-three people came, where we remained sixteen hours at table, which recommenced the next day and somewhat the following days). (NB: 37)

Data set (7)

French (English):

Puis on proceda à la fermeture. (Then we proceeded to closing).

On roula des blocs de pierre (…) (Blocks of stone were rolled […])

On retira la passerelle –pont-levis. (The way in—the drawbridge—was withdrawn).

On barricada toutes les issues, (All the exits were barricaded,)

et sonna le couvre-feu… (and the curfew was sounded) (VVS: 44)

Indonesian (English):

Kemudian benteng pun ditutup. (Then we proceeded to closing).

Tumpukan batu digulingkan …. (Blocks of stone were rolled […])

Jembatan yang bisa bergerak ditarik. (The way in—the drawbridge—was withdrawn).

Semua jalan masuk dirintangi. (All the exits were barricaded,)

Jam malam pun dibunyikan. (and the curfew was sounded) (KL: 42)

An analysis of the data presented above demonstrates that the verbs in data set (4), namely entreprit, dut, débarrassa, recueillit, fit, and répandit; the verbs in data set (5), namely [s’y] installa, remonta, croisa, and possa; the verbs in data set (6), namely eût, comprirent, eut, vinrent, resta, and recommença; and the verbs in data set (7), namely proceda, roula, retira, barricada, and sonna all utilize the passé simple tense to mark foregrounds. In contrast, in Indonesian, verbs with the affix “me(N)-” namely membuat, membabat, menguliti, mengambil, menyayatnya, merebusnya, menuangkan, and mengerti are utilized to mark foregrounds. Also employed for this purpose are passive verbs with the affix “di-” as well as the “di-” affix combined with the particle “-lah” in the words ditekuk, disilangkan, diletakkan, dilangsungkanlah, dilanjutkanlah, ditutup, digulingkan, ditarik, dirintangi, and dibunyikan. Lastly, there are also non-affixed verbs used such as diam and ingin. It is evident from these sets of data that the foreground markers in French narrative discourses are in passé simple tense, while the foreground markers in Indonesian narrative discourses are affix.

From a semantic perspective, the events represented in datasets (4), (5), and (7) are characterized as consecutive punctual events, while the events in the data set (6) are characterized as actionality, namely perfective in aspect but durative in meaning.

Pronouns as grounding intensifiers

In Indonesian, the pronouns dia and ia—both meaning “he,” “she,” or “it”—can serve as grounding intensifiers. The pronoun dia acts as a foreground intensifier, whereas the pronoun ia acts as a background intensifier. Note the following examples.

Data set (8)

French (English):

-

a.

Certain champignons rouges à être vénéneux, car plusieurs chevreaux étaient morts après en avoir brouté des fragments mêlés à l’herbe. (Certain red mushrooms must be poisonous, because several young goats had died after having eaten bits of them while grazing the grass).

-

b.

Robinson en tira un jus brunâtre dans lequel il fit tremper des grains de blé. (Robinson drew a brownish juice from it, in which he soaked grains of wheat).

-

c.

Puis il répandit ces grains empoisonnés sur les passages habituels des rats. Ils s’en régalèrentet ne furent même pas malade. (Then he spread these poisonous grains on the usual paths of the rats. They enjoyed them and were not even sick).

-

d.

Il construisit alors des cages dans lesquelles la bête tombait par une trape. (He then built cages into which the vermins fell through a trap).

-

e.

Mais il avait fallu des milliers de cages de ce genre, et puis il devait ensuite noyer les bête prises. (But he had required thousands of such cages, and then he had to drown the captured animals. (VVS: 46)

Indonesian (English):

-

a.

Beberapa jamur merah yang intinya berwarna kuning mestinya beracun. Karena beberapa ekor anak kambing mati setelah memamah beberapa jamur yang bercampur dengan rumput. (Certain red mushrooms must be poisonous, because several young goats had died after having eaten bits of them while grazing the grass).

-

b.

Robinson memeras jamur itu sehingga diperoleh cairan yang berwarna kecoklatan dan merendam biji-biji gandum di dalamnya. (Robinson drew a brownish juice from it, in which he soaked grains of wheat).

-

c.

Kemudian dia menebarkan biji-biji yang beracun itu di jalan yang biasa dilalui tikus. Binatang-binatang itu melahapnya tetapi sakit pun tidak. (Then he spread these poisonous grains on the usual paths of the rats. They enjoyed them and were not even sick).

-

d.

Oleh karena itu, dia membuat kurungan supaya tikus-tikus itu jatuh terperangkap. (He then built cages into which the vermins fell through a trap).

-

e.

Namun, ia memerlukan ribuan kurungan semacam itu dan lagi ia pun harus menenggelamkan binatang tangkapannya. (But he had required thousands of such cages, and then he had to drown the captured animals. (KL: 44)

Data set (9)

French (English):

-

a.

Robinson ne cessait d’organizer et de civilizer son île et de jour en jour il avait davantage de travail et des obligations plus nombreuses. (Robinson kept organizing and civilizing his island, and day by day, he had more work and more obligations).

-

b.

Le matin par exemple, il commençait par faire sa toilette, (In the morning, for example, he began by taking a wash,)

-

c.

puis il lisait quelques pages de la Bible, (then he read a few pages of the Bible,)

-

d.

ensuite il se mettait au garde-à-vous devant la mât où il faisait ensuite monter le drapeau anglais. (then he stood at attention in front of the mast where he then raised the English flag).

-

e.

Puis avait lieu l’ouverture de la forteresse. (Then the opening of the fortress took place)

-

f.

On faisait basculer la passerelle par-dessus le fossé et on dégageait les issues bouchées par les rochers. (The footbridge was swung over the ditch and the exits blocked by the rocks were cleared).

-

g.

La matinée commençait par la traite des chèvres, ensuite il fallait visiter la garenne artificielle que Robinson avait établie dans une clairière sablonneuse.(The morning began with the milking of the goats, then it was necessary to visit the artificial warren that Robinson had established in a sandy clearing). (VVS: 51)

Indonesian (English):

-

a.

Robinson tak henti-hentinya mengatur dan membudayakan pulaunya. Dari hari ke hari pekerjaannya semakin bertambah, dan kewajiban-kewajiban pun kian banyak. (Robinson kept organizing and civilizing his island, and day by day he had more work and more obligations).

-

b.

Setiap pagi misalnya, mula-mula ia mempersiapkan diri, (In the morning, for example, he began by taking a wash,)

-

c.

kemudian membaca beberapa halaman Injil, (then he read a few pages of the Bible,)

-

d.

dan berdiri tegak dengan sikap hormat di depan tiang, lalu ia mengibarkan bendera Inggris. (then he stood at attention in front of the mast where he then raised the English flag).

-

e.

Setelah itu benteng dibuka. (Then the opening of the fortress took place)

-

f.

Kemudian ia menurunkan jembatan yang panjang di atas parit dan menyingkirkan batu-batu karang yang menghalangi jalan-jalan ke luar (The footbridge was swung over the ditch and the exits blocked by the rocks were cleared).

-

g.

Kewajiban setiap pagi dimulai dengan memerah susu kambing, lalu ia harus pergi ke tempat kelinci hutan hidup berkelompok, yang dibuatnya di daerah terbuka yang berpasir. (The morning began with the milking of the goats, then it was necessary to visit the artificial warren that Robinson had established in a sandy clearing). (KL: 48)

As is evident in datasets (8) and (9) above, sentences (b), (c), and (d) in set (8) constitute foregrounds, while (e) serves as a background. In contrast, set (9) represents a background event utilizing the pronoun ia in Indonesian. The data above reveals that in Indonesian, foreground events are reinforced by the presence of the pronoun dia while background events are reinforced by the use of the pronoun ia.

Discussion

Datasets (1) through (7) demonstrate the changes of grounding markers in French narrative discourses when translated into Indonesian. The French language employs tenses, specifically the imparfait and passé simple tenses, as grounding markers (Sajarwa, 2013), while Indonesian utilizes verbs with affixes “me(N)-,” “ber-,” and “di-,” as well as non-affixed verbs, as grounding markers. In Indonesian, both backgrounds and foregrounds employ the use of verbs with the affix “me(N)-”, with the difference being those verbs with the affix “me(N)-” in backgrounds are static in nature, whereas in foregrounds, they are dynamic. This finding also serves to correct the opinion (Hopper, 1979) that verbs with the affix “me(N)-” solely function as background markers, and verbs with the affix “di-” serve as foreground markers. Both the affixes “me(N)-” and “di-” can serve as foreground markers. The affixes “me(N)-” and “di-” are a binary opposition pair (Artawa & Purnawati, 2020). Meanwhile, the affix “ber-” and non-affixed verbs do not function as markers because, in Indonesian, they are considered taken for granted (Wijana, 2021). The distinction between backgrounds and foregrounds can also be observed in terms of meaning. The meaning of background events is “to state a condition” and “regular activity,” while the meaning of foreground events is “punctual” and “actionality.”

The grounding concept in narrative discourse cannot be separated from its function within the narrative (Li, 2018). The background serves as the context for the events in the foreground and is not considered to be a central aspect of the story. Conversely, the foreground is the primary aspect of the story or serves to construct the story (Baryadi, 2002). A narrative can be constructed in two ways, by highlighting the doer or by highlighting the event (Hoed, 1992). Some stories emphasize the doers and make them a central part of the story (van Krieken et al., 2019). In this regard, French and Indonesians have different ways of achieving this. French uses the pattern of doer + verb in passé simple, as seen in datasets (4), (5), and (6), while Indonesian uses the pattern of doer + verb with affix “me(N)-” (Kaswanti, 1989). The doers can take the form of proper nouns or personal pronouns. The function of the doer in the foreground is to drive the story forward (Maingueneau, 2010). However, for stories that emphasize events, French uses the pronoun “on” to highlight or focalize the event or the story and eliminate the doer, as seen in the data (7). This phenomenon is related to what was stated by Rickard (1989) that starting from the 15th century, French passive constructions that placed animate nouns began to be restricted and replaced with pronominal forms. Furthermore, in the 17th century, a social upheaval occurred, in which the bourgeoisie emerged as a new social group due to the influence of the industrial revolution. This group completes the two groups that existed before, namely the court/nobility and the peasants. This bourgeois group was in between the courtiers and peasants since they were more educated and controlled industry and trade (Carpentier & Lebrun, 2011). It was during this period that the pronoun “on” appeared, and the bourgeoisie used it more often in oral communication to replace je ‘I’ and vous ‘you’. The use of the pronoun “on” is seen as a closeness and equality between speech participants and seen as a fundamental value for French society. Therefore, pronoun “on” is called pronom de communication ‘pronoun of communication’. On the other hand, in Indonesian, the passive construction “di-” is used to bring the story or event to the forefront. This phenomenon is due to the fact that in the Indonesian context, the most widely spoken regional language is Javanese, with around 60 million speakers, while other regional languages only have around hundreds or thousands of speakers (Rangkuti, 2004). Due to the large number of speakers, the Javanese language, which has basic principles of balance based on harmony, and prioritizes politeness and harmony, has influenced the Indonesian language, including the use of passive forms (Gunarwan, 2008). The use of passive voice in Indonesian is one of the strategies to convey messages more politely because it prioritizes the state of the event, which is the result of someone’s actions so that neither party feels commanding or being ordered (Dardjowidjojo, 2003). This is in line with the nature of the Indonesian language, which prioritizes harmony.

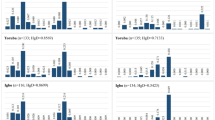

Thus, the findings indicate that the doer’s influence on the narrative is indicated by the affix “me(N)-” with a quantifiable proportion of 69%, while the passive form is indicated by 31%. On the other hand, when the doer is removed from the narrative, the tendency for the use of the passive form with the affix “di-” is 72%, while the use of the active form with the affix “me(N)-” is 28%. Both affixes “me(N)-” and “di-” in backgrounds demonstrate punctual and actionality meanings. The prefix “me(N)-” also dominates as a marker of background events at 67%, followed by the prefix “ber-” at 22% and non-affixed verbs at 11%. This suggests that background events tend to be indicated by the prefix “me(N)-,” which connotes static or regular activities.

A contextual analysis of the Indonesian language reveals issues in its context from a cultural perspective. In French narrative discourse, the protagonist is introduced with a proper noun followed by a pronoun, as seen in set data (3), and the pronoun persists for 18 sentences, while in Indonesian, the proper noun is followed by a pronoun only for nine sentences (Sajarwa, 2015). Meanwhile, Indonesian heavily employs the use of repetition (reduplication) as seen in set data (2). This mention and repetition of proper nouns are related to culture, indicating the display of courtesy or respect (Wijana, 2019). Language serves as a form of cultural expression for its users, who interact with the external world through their language (Bonvillain, 2008). Research on grounding using a cultural perspective will open up further studies in the future. Understanding culture supports the understanding of the text (Radin Salim & Mansor, 2021). This is supported by Lukin (2017), who argues that cultural analysis can reveal societal patterns of thought.

This examination of the linguistic grounding in French and Indonesian will be advantageous for advancing translation studies and foreign language acquisition. The growing interconnectedness of individuals from diverse nations necessitates proficiency in foreign languages to facilitate cross-cultural communication (Li, 2018). Additionally, language proficiency, particularly in translation and interpretation, is necessary to communicate effectively in various languages. The competence should not be limited to casual conversations, but extend to high-level textual forms, such as narratives. Translators serve as critical intermediaries, bridging the gap between languages and cultures (Bassnett, 2002). Hence, research on grounding is crucial in foreign language education. Grounding is a component of the elements or structure of narrative texts (Maingueneau, 2010). A thorough grasp of these discourse elements will enhance success in foreign language education. Bange (2005) emphasizes that language education is a process where learners engage in linguistic activities in accordance with linguistic principles.

The literature on the utilization of pronouns as grounding intensifiers is limited. An examination of Indonesian translations of novels reveals a scarce usage of pronouns as a means of emphasizing foregrounding and backgrounding. The three Indonesian translations of novels used in this research employs pronouns as grounding intensifiers. The study of the use of ia and dia as grounding intensifiers necessitates the gathering of additional data to facilitate future research endeavors.

Conclusion

This analysis highlights a distinction in the means of expressing grounding. While French grounding relies on tenses, such as passé simple and imparfait, Indonesian utilizes affixes like “me(N)-” and “di-” to express grounding. “Me(N)-” has the ability to signify both foregrounding and backgrounding, while “di-” is restricted to only foregrounding. This finding corrects the opinion of Hopper (1979). Additionally, Indonesian incorporates the singular third-person pronouns “dia” and “ia” to intensify grounding. A contextual analysis of the Indonesian language reveals a distinctive characteristic, where the repetition of proper nouns takes precedence over pronoun repetition as a form of cultural politeness.

Grounding is a storytelling strategy in narrative discourse. The above analysis of courtship shows that in Indonesian, the affixes “me(N)-“ and “di-“ function as courtship markers. In other words, typologically Indonesian uses the diathesis strategy, active-passive, to express courtship in narrative discourse. In contrast to French, it uses the tense strategy, imparfait-passe simple, to express plateaus in narrative discourse.

The field of Indonesian linguistic research has primarily been focused on morphological and syntactical analyses of affixes (Wijana, 2021). Examination of affix usage in discourse, specifically in narrative texts, has been inadequately explored. This lack of emphasis is reflected in the absence of grammar books dedicated to Indonesian language discourse. The need for more comprehensive research in this area, incorporating a cultural or contextual approach, is evident in the scarcity of studies on grounding in Indonesian narrative discourse.

The study is only based on data from the novel. It focuses on the grounding in written narrative discourse through the analysis of three French novels and their corresponding Indonesian translations. However, it is worth noting that Indonesian societies have a rich oral tradition, including fairy tales, myths, and folklores, each with their unique cultural backgrounds. These oral narrative discourses have not yet been studied with regard to grounding, particularly from a cultural perspective, offering substantial potential for future research in this area. Grounding studies on oral narratives and other types of texts are yet to be conducted and represent an opportunity for further grounding research.

Data availability

The data generated and/or analyzed during the current study were collected with support from my institution, and hence, they belong to the institution’s database. However, the author can guarantee to help access those datasets upon reasonable and responsible request.

References

Ahangar AA, Rezaeian SM (2017) The study of grounding of aspect and voice of verb in Persian-speaking children’s narrative discourse. J Lang Relat Res 8(1):155–177. http://dorl.net/dor/20.1001.1.23223081.1396.8.1.3.1

Artawa K, Purnawati KW (2020) Pemarkahan diatesis Bahasa Indonesia: kajian tipologi linguistik. Mozaik Humaniora 20(1):26. https://doi.org/10.20473/mozaik.v20i1.15128

Bange P (2005) L’apprentissage d’une langue étrangère: cognition et interaction. L’Harmattan, Paris

Baryadi PI (2002) Dasar-dasar Analisis Wacana dalam Ilmu Bahasa. Pustaka Gondosuli, Yogyakarta

Bassnett S (2002) Translation studies. Routledge, London

Bauer MW, Süerdem AK, Bicquelet A (2014) Text analysis—an introductory manifesto. In: Bauer MW, Bicquelet A, Süerdem A (eds).. Textual analysis: SAGE benchmarks in social research methods. vol. 1. SAGE Publications, Inc, London. pp. xxi–xlvii

Bonvillain N (2008) Language, culture, and communication: the meaning of messages. Pearson Prentice Hall, New Jersey

Carpentier J, Lebrun F (2011) Sejarah Prancis, dari zaman prasejarah hingga akhir abad ke-20. Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia, Jakarta

Chui K (2003) Is the correlation between grounding and transitivity universal? Stud Lang 27(2):221–244. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.27.2.02chu

Colas C, Akakzia A, Oudeyer P-Y, Chetouani M, Sigaud O (2020) Language-conditioned goal generation: a new approach to language grounding for RL. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2006.07043

Creswell JW, Guetterman TC (2011) Educational research: planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Pearson Prentice Hall, New Jersey

Dardjowidjojo S (2003) Rampai Bahasa, Pendidikan dan Budaya. Yayasan Obor Indonesia, Jakarta

Elson DK (2012) Modeling narrative discourse. Columbia University

Flaubert G (2012) Madame Bovary. Gallimard, Paris

Fleischman S (1985) Discourse functions of tense-aspect oppositions in narrative: toward a theory of grounding. Linguistics 23(6). https://doi.org/10.1515/ling.1985.23.6.851

Gooden S (2008) Discourse aspects of tense marking in Belizean Creole. Engl World-Wide J Variet Engl 29(3):306–346. https://doi.org/10.1075/eww.29.3.04goo

Gunarwan A (2008) Rasa Kejawaan dan Pengungkapan Tindak Tutur Pengancam Muka di Kalangan Orang Jawa. In: Sukamto, Endriati K (eds).. Kelana Bahana Sang Bahasawan. Penerbit Atma Jaya, Jakarta

Hoed BH (1992) Kala dalam Novel: Fungsi dan Penerjemahannya. Gadjah Mada University Press, Yogyakarta

Hopper PJ (1979) Aspect and foregrounding discourse. In: Givon T (ed).. Syntax and semantics: discourse and syntax, vol. 12. Academic Press, New York. pp. 213–241

Hopper PJ, Thompson SA (1980) Transitivity in grammar and discourse grammar and discourse. Language 56(2):251–299. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.1980.0017

House J (2006) Text and context in translation. J Pragmat 38(3):338–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2005.06.021

James C (1980) Contrastive analysis. Longman Inc, London

Jiayang C, Qiu L, Chan C, Liu X, Song Y, Zhang Z (2024, March 29). EventGround: narrative reasoning by grounding to eventuality-centric knowledge graphs. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2404.00209

Kaswanti PB (1989) Diatesis dalam Bahasa Indonesia: Telaah Wacana. In: Purwo BK (ed).. Serpih-serpih Telaah Pasif Bahasa Indonesia. Penerbit Kanisius, Yogyakarta

Li W (2014) Clause structure and grounding in Chinese written narrative discourse. Chin Lang Discourse Int Interdiscip J 5(2):99–145. https://doi.org/10.1075/cld.5.2.01li

Li W (2018) Grounding in Chinese written narrative discourse utrecht studies in language and communication. BRILL, Leiden

Lukin A (2017) Ideology and the text-in-context relation. Funct Linguist 4(1):16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40554-017-0050-8

Maalouf A (1993) Le Rocher de Tanios: Roman. Grasser & Fasquelle, Paris

Maingueneau D (2010) Manuel de Linguistique pour les Textes Littéraires. Armand Collin, Paris

Mckee A (2001) A beginner’s guide to textual analysis. Metro Magazine: Media Educ Magazine 127:138–149

Radin Salim N, Mansor I (2021) Penguasaan Kecekapan Budaya dalam Terjemahan Arab–Melayu (Mastery of Cultural Competence in Arabic-MalayTranslation). GEMA Online® J Lang Stud 21(2):111–134. https://doi.org/10.17576/gema-2021-2102-06

Rangkuti R (2004) Language maintenance & language shift: Linguistic consequences in multilingual setting. Julisa J Linguist Dan Sastra 4(2):128–142

Rickard P (1989) A history of the French language (2nd edition). Routledge, London and New York

Sajarwa S (2013) Pelataran dalam Wacana Bahasa Prancis. J Hum 25(2):205–214. https://doi.org/10.22146/jh.v25i2.2363

Sajarwa S (2015) Topik Wacana Bahasa Prancis dan Penerjemahannya dalam Bahasa Indonesia. Universitas Gadjah Mada

Sastriyani SH (2004) Studi Gender dalam Komik-komik Prancis Terjemahan. Humaniora 16(2):123–132. https://doi.org/10.22146/jh.812

Sastriyani SH (2011) Sastra Terjemahan Prancis-Indonesia. Gadjah Mada University Press

Shen L (2012) Context and text. Theory and practice in language studies, 2(12). https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.2.12.2663-2669

Soni S, Sihra A, Evans EF, Wilkens M, Bamman D (2023, May 27). Grounding characters and places in narrative texts. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2305.17561

Sutanto I (2014) Fungsi Klausa Berargumen Agen dan Pasien dalam Wacana Naratif. Universitas Indonesia

Tournier M (1971) Vendredi ou la Vie Sauvage. Gallimard, Paris

Urzha A (2018) Foreground and background in a narrative: trends in foreign linguistic and translation studies. Slovene 7(2):494–526. https://doi.org/10.31168/2305-6754.2018.7.2.20

van Krieken K, Sanders J, Sweetser E (2019) Linguistic and cognitive representation of time and viewpoint in narrative discourse. Cogn Linguist 30(2):243–251. https://doi.org/10.1515/cog-2018-0107

Wang H, Ji J, Zhou Y, Wu Y, Sun X (2023, January 8) Towards real-time panoptic narrative grounding by an end-to-end grounding network. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2301.03160

Wijana IDP (2019) Pengantar Sosiolinguistik. Gadjah Mada University Press, Yogyakarta

Wijana IDP (2021) Me(N)- and Ber- In: Indonesian. Prosiding Seminar Nasional Linguistik Dan Sastra (SEMANTIKS). pp. 96–107

Wongnuch P, Ruanjai T, Mee-inta A, Inta C, Apidechkul T, Tamornpark R, Thutsanti P (2022) Narratives of structural and cultural violence in the context of the stateless hill tribes living with HIV/AIDS in Chiang Rai, Thailand. Asia-Pac Soc Sci Rev 22(1):13–23

Zhang W, Wang X (2011) Language grounding model: connecting utterances and visual attributions. The Fourth International Workshop on Advanced Computational Intelligence. IEEE. pp. 409–415

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author contributed 100% on all aspects of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author(s) herewith declare that this article is totally free from any conflict of interest regarding the data collection, analysis, and editorial process, and the publication process in general. The author was never involved in editors’ decision-making at all costs.

Ethical approval

This article is totally free from ethical matters during its process as its objects were novels and does not contain any studies with human participants performed by the author.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by authors or any studies with human participants performed by the author.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sajarwa Groundings in French and Indonesian narrative discourses: linguistic and culture analysis. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1612 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04117-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04117-8