Abstract

Within the migration system, the seminal Foresight report highlighted that climate change can have significant implications for staying populations. Yet research on this remains limited. This study aims to fill this gap by assessing the impacts of sustained outmigration on staying farmer communities in the Indian Himalayan Region, affected by incremental climate change. Employing an empirical qualitative approach, new data is collected through semi-structured interviews (n = 72). Staying communities describe migration as good, bad, and necessary with the majority (46%) noting negative impacts such as fewer people to do agriculture, abandoned assets, more tasks for women, loss of community, disrupted household structures, mental health implications for the elderly, and disinvestment in public services. While remittances from migration have positive impacts, they are primarily used for meeting everyday needs (81%) and not invested in climate change adaptation. In addition to migration impacts, changing weather patterns, agricultural shifts, and societal transformations further exacerbate the vulnerabilities of staying populations. Without policy support to address these vulnerabilities, the benefits of migration may not effectively contribute to climate change adaptation. The findings here are likely applicable to staying populations in other mountain areas, facing similar pressures from migration and climate change, underscoring the need for targeted interventions to build long-term adaptive capacity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is scientific consensus that climate change will have significant impacts on migration (Beine and Jeusette 2021; Cissé et al. 2022; Hoffmann et al. 2020). Within the migration system, these impacts can be for three population groups—migrants, staying communities in origin areas and receiving communities in destination areas (Gemenne and Blocher 2017).

While existing studies extensively discuss the impacts on migrants and receiving communities (Marandi and Main 2021; Warnecke et al. 2010), staying communities have received comparatively less attention in the climate mobility literature (Borderon et al. 2021; Cissé et al. 2022; Cundill et al. 2021; Schewel 2020; Zickgraf 2021). Recognising this as a gap, de Haas notes that there is a “concomitant ignorance of the causes, consequences and experiences of migration from an origin-area perspective, leading to one-sided, biased understandings of migration” (de Haas 2021, p. 3). As early as 2011, the Foresight report on Migration and Global Environmental Change highlighted that staying populations are “hidden from high-level estimates, yet they represent a policy concern just as serious, if not more serious than migration” (Foresight 2011, p. 191). Yet to date, there is limited understanding of the experiences, challenges, and needs of staying communities (Ghosh and Orchiston 2022; Upadhyay et al. 2023).

This paper aims to fill this gap by investigating the impacts of outmigration in climate change-affected staying communities across 13 villages in the Indian Himalayan Region. This study explores the consequences of staying-put in an environment characterized by sustained outmigration and increasing climate change impacts that directly affect agrarian livelihoods in the region.

Uttarakhand is a pertinent context to analyse such dynamics for three reasons. First, its geographical location within the Indian Himalayan Region, makes it a hotspot for climate change-related risks including glacial melt, flash floods, cloud bursts, heatwaves, and shifting rainfall patterns (ICIMOD 2023; Krishnan et al. 2019; Kulkarni et al. 2013; Singh et al. 2023; Wester et al. 2019). Second, in the last decade, climate change has significantly influenced migration decisions, particularly due to its detrimental effects on agriculture—sustaining 70% of the population (GU 2017; Naudiyal et al. 2019)—which has led to increased outmigration due to unreliable agricultural outcomes (Naudiyal et al. 2019; Siddiqui et al. 2019a; Tiwari and Joshi 2015; Upadhyay et al. 2021). Third, migration has become a ‘problem’ for policy in Uttarakhand (RDMC 2018, p. 6), due to a notable increase in permanent migration of entire families leading to depopulation and loss of human and social capital in mountain villages (Mamgain and Reddy 2016; Pathak et al. 2017; RDMC 2018). This has implications for staying populations who face the twin challenges of climate change and sustained outmigration.

This study addresses certain gaps in the literature. First, it addresses the “mobility bias”—where research has predominantly focused on migration and migrants (Schewel 2020). Instead, it shifts the focus to staying populations. Second, there exists a general assumption that migration is good for those who stay (de Haas 2007; Phongsiri et al. 2023) with emphasis on the economic impacts, particularly viewing staying populations as remittance receivers (Phongsiri et al. 2023, p. 9). This study expands the scope beyond economic impacts. Evidence is presented on the cultural (loss of mountain identity and culture), social (loss of community and decline in collective action), demographic (changes in household composition), and institutional (disinvestment in public services) impacts of migration on staying populations. Third, while migration impacts have been shown to affect the adaptive capacity to climate change (Carvajal and Pereira 2010; Entzinger and Scholten 2022; Obokata et al. 2014; Szaboova et al. 2023), other wider changes in weather patterns, agriculture, and society, also play a crucial role. To capture this, these wider “change processes” are analysed to understand their implications for staying populations.

This research brings a novel perspective by focusing on migration impacts through the experiences of staying populations. The findings highlight that migration’s effects are not uniform—they can be positive, negative, and at times migration can be necessary, depending on the local context, individual circumstances, and household characteristics. While previous studies have highlighted the positive and negative aspects of migration, they tend to emphasise only one side and overlook the complex interpretations from staying populations, largely because they are not grounded in the lived experiences of these communities. By focusing on those who stay, this research deepens the understanding of migration’s impacts.

The key implication of this study is that the negative impacts of migration, along with other wider changes such as weather variability, agricultural shifts, depopulation, and societal transformations—undermine the adaptive capacity of staying populations in Uttarakhand, and render them more vulnerable to future climate risks. Research has established that those most adversely affected by climate change are often those who face resource constraints, which limits their ability to migrate (Adger et al. 2021; Benveniste et al. 2022; Cappelli 2023; Veronis and McLeman 2014). Consequently, without support for local adaptation or the means to migrate, these populations are at risk of becoming trapped. (Ayeb‐Karlsson et al. 2022). Thus, targeted interventions aimed at enhancing local adaptive capacities are crucial.

The research questions of this paper are: (1) what are the impacts of outmigration experienced by staying populations? (2) Over the past decade, what other kind of changes have been the most concerning to the staying communities? By analysing the impacts of migration and other ‘processes of change’, the study draws implications for the adaptive capacity of staying communities.

Impacts of migration in climate change-affected staying communities

Migration can result in both positive and negative outcomes for staying populations. It can be a coping and a climate adaptation strategy when it leads to diversification of livelihoods (Banerjee et al. 2011; Maharjan et al. 2021), reduction of poverty (Siddiqui et al. 2019b), decreased volatility of household income (Morten 2019), increased social protection (Silchenko and Murray 2023) and enhanced adaptive capacity (Deshingkar 2012; Jha et al. 2018; Tiwari and Joshi 2015). However, migration can also have adverse impacts. These include—increased workload for women as men migrate (Pandey 2021; Upadhyay et al. 2023), loss of socio-cultural support systems (Asthana 2012), reduced labour in agriculture (Mamgain and Reddy 2016; Shukla et al. 2018), shifts in population size and composition (Ghimire et al. 2021; Speck 2017; Upadhyay et al. 2021), and decline in community-led local governance structures (Qin and Flint 2012).

Remittances are widely discussed as one of the key benefits of migration for staying populations (UNCTAD 2013). They play a vital role in contributing to household income, building assets, coping with shocks, diversifying risk, and meeting everyday household needs. For example, in Bangladesh, remittances have been shown to aid in coping and recovery from floods (Giannelli and Canessa 2021). In the Himalayas, 90% of remittances are used for meeting daily household consumption needs (Mamgain and Reddy 2016).

In mega deltas of Asia, remittances improved the wellbeing of staying populations via investments in health, food security, and access to sanitation (Szabo et al. 2018). Harnessing the positive impacts, remittances have been hailed as a ‘game changer’ for climate adaptation financing (Musah-Surugu and Anuga 2023). Nevertheless, some have criticised the “remittances euphoria” (de Haas 2007, p. 1) – prompting inquiries into the effectiveness of remittances in enhancing adaptive capacity to deal with climatic risks (Singh and Basu 2020, p. 95; Vinke et al. 2022).

While remittances have the potential to aid adaptation, their effectiveness is not predetermined. For instance, research in semi-arid India underscores that although remittances helped impoverished households to manage debt and repay loans, it did not lead to increased adaptive capacity to deal with climate risks (Singh 2019). In Nigeria, evidence suggests that remittances do not aid in enhancing adaptive capacities because “households did not appreciate the need to channel remittances to climate change adaptation” (Maduekwe and Adesina 2022, p. 9). It’s also been argued that remittances may be unreliable during times of crisis (Awasthi and Mehta 2020; Mehta 2022) and could potentially exacerbate disparities between households that receive remittances and those that do not, potentially heightening inequality in the staying populations (Millán 2020). Therefore, the outcomes of remittances do not necessarily translate to increased adaptive capacity.

Less attention has been paid to the non-economic impacts of migration such as environmental, social, and cultural changes in staying populations (McNamara et al. 2021). In the Himalayas sustained outmigration has led to farm exit and abandonment of land (Biella et al. 2022; Ghimire et al. 2021; Jaquet et al. 2016; Ojha et al. 2017; Upadhyay et al. 2023) resulting in a 16.8% decline in agricultural production in Nepal (Khanal et al. 2015). In the Andes, outmigration has resulted in a labour shortage for maintaining Bofedales (mountain peatland pastures). Coupled with climate change impacts, this has led to the degradation of pastures, significantly affecting indigenous pastoral communities (Yager et al. 2019). In India, staying populations face the ‘loss of a community’ that once facilitated “coping with poverty through personalized strategies, informal loans, and the exchange of essential goods and services, such as food, clothing, and housing support” (Asthana 2012, p. 100). In some regions, outmigration has led to the breakdown of traditional family-based elderly care systems. For instance, in Nepal, without a government support system, elderly individuals rely on family members who live with them. This system had eroded due to outmigration, leaving elderly people feeling isolated and unsupported (Speck 2017, p. 433). Similarly in Ghana, outmigration due to environmental changes has left those who stay experiencing deep emotional impacts of increasingly “hollow homes” (p.24), resulting in social emptiness and solastalgia (Tschakert et al. 2013). These impacts have received insufficient attention compared to the economic impacts of migration and demand greater consideration.

Central to the discussion on migration impacts is the concept of adaptive capacity, which is the ability to adapt to changing climatic conditions (Smit and Wandel 2006). It is intricately tied to the local context such as socio-economic conditions, access to financial resources, social structures, access to information, and the effectiveness of local institutions (Cardona et al. 2012; Pelling and High 2005; Smit and Wandel 2006). Existing research suggests that migration directly affects the adaptive capacity and options available to staying populations (Carvajal and Pereira 2010; Cissé et al. 2022; Entzinger and Scholten 2022; McLeman 2010; Obokata et al. 2014; Rao et al. 2020; Singh 2019). For instance, a comparative analysis spanning Nepal, Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh, found that migration has both positive impacts on adaptive capacity through remittances and negative consequences, notably in the form of elevated social costs (Maharjan et al. 2020). In eastern India, households receiving remittances had higher adaptive capacity due to improved access to financial resources and insurance that enabled them to cope with floods (Banerjee et al. 2017). Contrastingly, in Cambodia, migration is a maladaptive strategy that results in a climate change-induced poverty trap for staying populations (Jacobson et al. 2019). In Nepal, migration has resulted in the loss of community, erosion of social fabric and cultural norms, and led to the abandonment of land, impact on agricultural labour, thereby undermining the adaptive capacity of agrarian communities (Ghimire et al. 2021; Naudiyal et al. 2019). These varying impacts of migration on adaptive capacity highlight the complex and context-specific nature of this relationship.

Study region

The data for this study was collected from the Himalayan state of Uttarakhand in India (Fig. 1). The state is divided into two sub-regions, Kumaon and Garhwal, with 13 districts. Ten of these districts are hilly and rural, while the other three are plains with urban centers. About 80% of the total area is hilly and mountain terrain. Uttarakhand is endowed with natural resources like glaciers, rivers, and 65% of the total area is under forests (Sati 2020).

Map of India, highlighting the state of Uttarakhand; on the right the thirteen districts of Uttarakhand. Source: Upadhyay et al. 2021.

The total population stands at 10.11 million as per the 2011 Population Census (Census 2011), comprising 69.5% rural and 30.5% urban population (DoRD, GoI 2011). In 2011, Uttarakhand saw population decline, with Almora and Pauri Garhwal districts recording a negative decadal population growth rate of −1.73% and −1.51% respectively (RDMC 2018, p. 16). Out of the state’s 16,793 villages, 1048 are uninhabited (RDMC 2018), which are often referred to as “bhutiya gaon” or ghost villages (GU 2014; Mamgain and Reddy 2016; Pathak et al. 2017; RDMC 2018; Sati 2021).

Migration holds a longstanding presence in Uttarakhand’s history where it has been a strategy to diversify income, cope with challenges of mountain agriculture, and pursue personal aspirations (GU 2018a; Mamgain and Reddy 2016; Pathak et al. 2017). Key drivers of migration are lack of employment opportunities, inadequate healthcare and educational facilities, declining agricultural productivity, and structural deficiencies such as inadequate infrastructure, electricity, and irrigation (RDMC 2018).

Economic growth has favoured the three plains districts, leaving the ten hill districts with limited employment options and a heavy reliance on agriculture. These disparities have influenced migration patterns from the hills to the plains (GU 2018a). In the hill districts, 34.3% of the households had at least one migrant while in the plains only 5.3% of the households had a migrant (GU 2018a, p. 133). The largest demographic of migrants (42%) falls within the 26 to 35 age bracket (RDMC 2018). Remittances are prevalent, with 75.5% of migrants sending an average of about $1000 per year, predominantly used for household consumption (GU 2018a).

Migration patterns have changed over time. Earlier migration was male-specific, focused on earning an income, while still maintaining strong ties to one’s village, reflected by the “money order economy” –referring to remittances sent by migrants (Bora 1996; Mamgain and Reddy 2016). This form of migration, though long-term, typically involved a return and resettlement in the village after the job tenure (Mamgain and Reddy 2016; Sati 2021). Now, the dynamic has shifted, as entire families migrate, and what was once long-term migration has evolved into a permanent migration which is for better education, access to healthcare facilities and employment (RDMC 2018). Migrants leave behind their house, land, and other assets, with no intention of returning which has gradually led to ghost villages in Uttarakhand (Pathak et al. 2017; RDMC 2018).

Around 70% of the population is engaged in agriculture which is for subsistence (Shukla et al. 2016). However, agriculture in the Uttarakhand faces significant challenges. Only 14% of the land is suitable for farming, characterized by small land holdings—75% less than 1 hectare which is further spread into an average of 3 land parcels (GU 2014). Around 55% of agriculture is rain-fed. Limited mechanization, high cultivation costs, and inadequate agricultural extension services impact production (GU 2018b; Naudiyal et al. 2019).

Uttarakhand faces significant climate change risks. A report on future risk and vulnerability assessment of Indian agriculture (2020-49), classifies Uttarakhand as being at “very high risk” due to climate change (Rao et al. 2019). Rainfall data shows a decline of—annual rainy days from 72 days to 58 days, and rainfall amount from 132 cm to 102 cm (between 1900 and 2010) (Tiwari and Joshi 2012). Projections indicate an increase in extreme rainfall events with more than 100 mm of rainfall in three consecutive days. Observed temperatures in Uttarakhand indicate a warming trend, with the mean annual temperature increasing by 0.84 °C over 41 years (1969–2009), with a more notable increase of 1.41 °C during the winter months (Dec-Feb) (Das and Meher 2019). Future projections indicate a continued warming trend, where the mean annual temperature could increase by 0.5–1 °C (2011–2040), 1–3 °C (2014–2070), and 4–5 °C (2041–2098) (Kulkarni et al. 2013). Increasing temperatures in the region have led to one of the fastest glacier recessions in the world (You et al., 2017), with observations indicating a 24% decrease in total glacier area from 1977 to 2010 (Ratna Bajracharya et al. 2020). Projections suggest that Himalayan glaciers may lose 80% of their volume by 2100 (ICIMOD 2023) significantly impacting water resources, ecosystems, and mountain development.

These impacts have serious consequences for agriculture, including a decline in crop yields, loss of indigenous plant agro-biodiversity, and increased land degradation (Chauhan et al. 2020; Kaul and Thornton 2014; Rautela and Karki 2015; Shukla et al. 2021). The volatility of agricultural sector due to climate change has led to an increase in outmigration in the region (Banerjee et al. 2014; Biella et al. 2022; Tiwari and Joshi 2015; Upadhyay et al. 2021). This is also noted by the Uttarakhand Action Plan on Climate Change, “[c]limate change-driven uncertainly in mountain agriculture has forced people to migrate from the hills in search of employment (GU 2014, p. 105).

Methodology

Study sites

A field study was done in Uttarakhand between September and November 2019, across 13 villages in four districts: Almora, Pauri Garhwal, Dehradun, and Nainital. Village selection involved consultations with key informants and regional experts and was informed by prior research on climate change impacts and migration in the state (GU 2018a, 2014; Guhathakurta et al. 2020; INRM 2016; Mamgain and Reddy 2016; Pathak et al. 2017; RDMC 2018; Shukla et al. 2016; Tiwari and Joshi 2016, 2015). The villages varied in population size and demonstrated high agricultural dependency. Details of the interview sites are in Supplementary Information S1.

Interviews

Total of 72 semi-structured, face-to-face qualitative interviews were conducted in Uttarakhand (details in Supplementary Information S2). Of the total, 54 interviews were done with the staying population, while 18 were done with key informants. Snowball sampling was used for recruiting staying populations while purposeful sampling was applied to select key informants (Creswell and Plano Clark 2018; Knott et al. 2022). I examined the impacts of migration from two viewpoints: first, from the vantage point of the staying communities, who shared their individual experiences; and second, through the insights of key informants, offering a community-wide outlook. Key informants included civil society actors, policymakers, along with experts in agriculture, rural development, migration, and climate change. They gave valuable insider insights and contextual background, aiding in the interpretation of results (Bogner et al. 2009; Döringer 2021).The interviews focused on a primary respondent from a household. They were conducted in Hindi, a language understood by all participants. Occasionally, respondents would respond in Kumaoni or Garhwali (local languages of Uttarakhand), both of which were understood by the author. Some expert interviews were conducted in English. The interviews ranged from 30 to 90 min and were either audio recorded or documented as text notes. Participants provided informed consent, and their data was anonymized and kept confidential. Qualitative data from the semi-structured interviews was translated and transcribed in English, and subsequently analyzed in MAXQDA to categorize the information, as detailed in section S3 of the Supplementary Material.

The interview guide for both key informants and the affected population incorporated a blend of structured and unstructured questioning techniques (Corbin and Strauss 2015). Spontaneous probing questions were included to ensure full capture and clarification of experiences and understandings. Data saturation (Morse 1995; Saunders et al. 2018), was reached when no additional data emerged and recurring themes became evident (Small 2009). Our analysis follows the grounded theory approach, which aims to be explanatory rather than representative (Charmaz 2015; Glaser and Strauss 1967).

Socio-demographic summary of data

Out of the 54 interviews done with the staying population, 51 were engaged in agriculture. Among them, 32 practiced only subsistence agriculture, while 19 had additional occupations alongside farming. Two interviewees did not engage in agriculture, receiving pension instead while one had non-farm based income. Of the 54 people interviewed, 37 had at least one migrant, and of that, 33 reported receiving remittances. In terms of gender, 29 men and 25 women were interviewed. Among the men, 10 were involved in subsistence agriculture, 18 had supplementary occupations, and one operated a shop without any agricultural engagement. Among the women, 22 were dedicated to subsistence agriculture, while 2 received a pension and 1 pursued an additional occupation alongside farming (Table 1). Concerning age, the interviewees were predominantly middle-aged and elderly individuals, with the majority of the younger population out-migrating (Table 1). Sixteen interviewees had lost their spouse, with fifteen of them being 60 years of age or older and living by themselves. (Definitions regarding Table 1 are provided in the Supplementary Material S5).

Population characteristics

The study population primarily consisted of subsistence farmers, practicing multi-generational farming on the same land. Agriculture relied on family labour, predominantly led by women who also managed animal care, water collection, and household chores. Environmental and livelihood knowledge was passed down through generations. Adaptation to fluctuating weather patterns, particularly the uncertain monsoon rainfall, posed new challenges. Agricultural losses were managed at the household or community level with minimal support from the government and public institutions. Crop insurance schemes were reportedly lacking in the region.

Limitations

The findings of this study should be seen in light of some limitations. First, the snowball sampling technique used has its drawbacks, such as a tendency toward homogeneity, which can lead to bias and blind spots (Patton 1980; Bhattacherjee 2012). However, snowball sampling remains a reliable method for accessing remote and hard-to-reach populations like those in Uttarakhand. Additionally in this case, depopulation in the villages made it challenging to find participants, making snowball sampling an effective approach.

Second, the understanding of migration impacts could be improved by considering factors like social hierarchies (e.g., caste), migration history, household income, and assets. However, the author was advised against asking culturally sensitive questions about caste, as they could come across as discriminatory. While efforts were made to inquire about income and assets, many interviewees were hesitant to share this information due to concerns about potential negative consequences. Future research could explore these aspects more deeply, provided that appropriate methods can be developed to address these in interviews. Additionally, future studies could aim to disaggregate data and pay closer attention to differences among populations in the context of migration impacts.

Results

Migration as good, bad, necessary

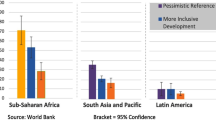

Interviewees were asked about the impacts of migration and here they are presented as good (positive impacts), bad (adverse impacts), and necessary (see Fig. 2). Out of the 54 interviews conducted with the staying populations, 25 respondents perceived migration as bad, 13 considered it good, 5 deemed it necessary. While 9 acknowledged both positive and negative impacts, and 2 respondents abstained from providing comments (see Fig. 3). A detailed quantitative summary of responses given by the interviewees is provided in Supplementary Material S4.

Migration is good

24% of the interviewees noted the positive impacts of migration and highlighted several key aspects. These include the impact of remittances, the pursuit of opportunities beyond agriculture, acquisition of new skills, strengthening household income security, and the potential for upward social mobility within society.

In Uttarakhand, remittances play a crucial role in supplementing household income. The majority of remittances are allocated to essential needs such as clothing, food, farm labour, school fees, medical expenses, house maintenance, and other everyday needs. As shared by A4, “My son migrated many years ago. He is an engineer and has a good job in Delhi. He earns about 40000/month (∼450 Euro) and sends me some money regularly. That comes in handy. I was able to marry two daughters. I use the money to buy food, pay for farm labour. Not everyone in the village has that comfort”. However, unlike other regions in India, Uttarakhand has not experienced a multiplier effect of remittances on the local economy.

Interviewees highlighted the acquisition of skills as a significant gain from migration. Migrants working as an electrician, driver, painter, computer operator, cook, tailor etc. gained skills outside agriculture. This not only opened up economic opportunities in their destination regions but also elevated their social status in the village. Nevertheless, a notable challenge persists—the absence of an economic environment that encourages migrants to apply these acquired skills in their native areas, hindering their ability to earn a living locally and possibly to return.

Migration is bad

The adverse impacts of migration were emphasised by 46% of those interviewed. Interviewees cited that sustained migration had led to reduced labour in agriculture, loss of community, increased inequality, more tasks for elderly women, shifts in demographic composition with predominantly elderly residents often living alone, and a decline in state-supported infrastructure in sparsely populated villages.

A tea stall owner highlights the impacts of migration on the education infrastructure “[we] have around 9 school-going children in our village but there are no teachers. They come and go. We hear that the school might shut down and the local public authorities are not doing anything about it. They say there are not enough children to run a school” (PG10). A similar retreat of the state is also observed in primary health care centers, which often lie dysfunctional due to lack of staff and maintenance. Villagers often have to undertake a long ordeal in the mountains to get basic health treatment.

Sustained outmigration has reduced the labour available for agriculture. Farming in this region relies heavily on family labour and is a communal activity, with individuals owning different parcels of land but working together in the fields, planting the same crops, and harvesting collectively. However, as people migrate there are increasingly less people doing agriculture. As highlighted by N12 “I have a piece of land which is fertile and well farmed now there is another piece of land next to mine which is fallow, as people migrated and abandoned their land. So now, all the rats, pests, and invasive crops will come to my side of the land and spoil my crops. So when people migrate it is bad for my farming”. Moreover, there is a growing menace of wild boars destroying standing crops. In the past, villagers would collaborate to build a communal fence to protect farmed fields, taking turns to watch and ward off wild boars. However, with a declining population, this entire system of community protection no longer exists.

The state of Uttarakhand has witnessed an increase in could bursts, flash floods, and heavy precipitation events in recent years. These events break mountain terraces where communities do farming. Discussing the twin consequences of such environmental challenges and outmigration A3 notes, “Too much rain is not good, it hurts us. Heavy rainfall breaks the steps on our terrace. In my field, all the steps are broken, and I cannot afford to repair them. I have four brothers and until they migrated, we could repair the damage together. Even people from the village would help and lend money if needed. But, it’s no longer the same. There is a lot of migration so who is there in the village now?” These experiences underscore the consequences of outmigration for traditional risk management practices and the collective mitigation of crises. Additionally, they illuminate the detrimental impact of increased societal fragmentation resulting from migration, which undermines support at both the household and community levels during challenging times.

Migration-affected changes in rural villages, have led to a distinction between locals and outsiders. As native villagers permanently migrate, there is an influx of bahar ke log (outsiders), potentially impacting the social fabric and ties crucial to rural mountain communities. According to N12, “People who have migrated have sold their land to outsiders who have come and settled in our village. Because of that, our cows cannot graze in the forest anymore as they have closed those pathways. They hire Nepalese migrants who work in their fields and grow whatever they like. We are not happy about all these new things happening in our village. But we cannot even raise our concerns. We have to keep quiet. It’s not the same as before when the whole village was one big family.” This influx of outsiders, now landowners, represents a departure from centuries of exclusive land ownership by village residents and their descendants, highlighting a significant transformation in mountain communities. While common property resources like forests are vital for Uttarakhand’s agrarian communities, the arrival of outsiders as landowners disrupts the traditional access to the forest, typically regulated by local institutions. Furthermore, there is growing dissatisfaction among the local population towards Nepalese migrants, who, operating under the free border agreement between Nepal and India, cultivate non-traditional crops like paprika, broccoli, and mushrooms. The economic success of these crops, not cultivated by natives, adds to the discomfort among the local population.

Sustained migration has given rise to “akelapan” – loneliness, particularly among the elderly. This term emerged consistently in interviews with the elderly who were often living alone. It was common for them to compare their solitary living situation with the past, when their homes were filled with daughters-in-law and grandchildren, regardless of where their sons lived. The evolving dynamics of migration have left households fragmented, altering family configurations and leaving the elderly feeling isolated. Expressing her sadness, PG 12 shares, “I feel sad. I live alone and miss my family. When my children visit, it feels good. Else who is there to talk to me? There was a time when we had full families living in our village. There was hustle and bustle all day. It was so lively, now everything is dull (she is crying).” This statement reflects that changing configurations of households affect the mental health and wellbeing of the elderly.

Migration has altered the collective approaches to addressing water stress, with a shift towards individual efforts replacing the once-prevailing communal strategies. As noted by PG9 “[w]e have communal rainwater harvesting structures that a local NGO built in our village. Now they are lying wasted, as we are not able to take care of it. Where are the people to do it? We have tried to address this as a community but most of our population is old. They cannot do the physical hard work that is required. If you walk around the village, you will find that there are private cemented water storage structures built for individual use. But, not everyone can afford such a construction. As we don’t have someone sitting in the city and sending us money”. This underscores the impact of migration on community resilience, highlighting the pressing need for comprehensive strategies to support both collective and individual efforts in mitigating climate-related challenges.

Migration has led to more tasks for women, as shared by A7 “I am removing the husk from the grain. My day is busy. I first go to the forest to bring wood and fodder, then I go to the fields, till the land, sow the seeds, grow the crop, then I also need to look after the animals, make dung cakes, and then there is food to be cooked and the house to be cleaned. Earlier there were more people in my household so I didn’t have to do everything. Now I do not even have time to sit and eat food. There is a thorn stuck in my blouse since morning and I have not found the time to take it out. As I have to finish this task”. This highlights the increased workload experienced by women with little time for personal care or rest.

Migration is necessary

There is an old saying in Uttarakhand that “pahad ka paani aur pahad ki jawani uske kaam nahin aatey”—the mountains never benefit from its water and its youth. This local idiom is a telling statement of migration from the state. Amongst the interviewees 9% noted that migration is necessary due to lack of employment, infrastructure, and development in the mountains, to adapt to the constraints of mountain agriculture, and for household economic security.

In conversations, educational institutions were often criticized as factories churning out unemployed youth who, despite getting an education, faced uncertain job prospects in the mountains due to limited opportunities. Such economic hardships result in migration to cities that offer diverse employment opportunities in industries, skilled jobs, unskilled jobs, and wage labour. Moving out of the village, getting a job, and earning an income were considered a rite of passage and a social marker of success, as emphasized by A12: ‘If people are educated, they have to migrate. Why stay here? There is no opportunity in the village—no jobs, no income. An educated person will not pick up cow dung in the village. They would want to go to the city and earn money. So they quit rural life. It is about status and ideas of what success is”. The quote highlights how the need for migration is influenced by—the “push” factors, driven by limited opportunities in the mountains, and the “pull” factors, drawing individuals towards diverse opportunities in urban centers in the cities.

The necessity of migration is further highlighted by this example. In recent years, there have been growing efforts by the Government to bring back migrants, but there is reluctance to return. This was evident, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, which witnessed a significant reverse migration to villages in Uttarakhand (RDMC 2020). The government took multiple steps to retain returning migrants by providing financial support to encourage self-employment, facilitating economic reintegration, and offering a special resettlement package. Despite these initiatives, approximately 68% of migrants expressed a desire to return to their migrant destinations once the lockdown was lifted due to a lack of livelihood opportunities in their native areas (Awasthi and Mehta 2020, p. 1118).

Processes of change

Staying communities in Uttarakhand are facing the twin impacts of sustained outmigration and the adverse effects of climate change on agriculture and livelihoods. Amidst these challenges, these communities undergo various interconnected processes, including social, economic, environmental, and political changes—that collectively influence their adaptive capacity (Fig. 4). With the aim to understand the other wider processes of change impacting staying communities, I asked—for the past decade, what kind of changes have been the most concerning to the staying populations?

Climate change impacts

Interviewees noted changes in weather patterns affecting their livelihoods as a concerning development in the past decade. As emphasized by A5 “[e]arlier the months of ashad, savan and bhado (Hindu calendar months from June to September) were the rainfall time. There is a saying that ‘jab naya pani nikalega tab barish rukegi’ (when the land gets saturated with rainfall the new water will seep out and rainfall will stop). Now it has gone all wrong. Rain is happening out of time”. In addition, the interviewees also reported late monsoon rains, reduced snowfall, untimely and irregular rainfall, increased heavy rainfall events, cloudbursts, and landslides.

Drying of mountain water springs came up as a common concern among the interviewees. Earlier, the springs were enough to support the drinking water needs of the villagers. However, in the last decade, these springs, once reliable, have run dry, exacerbating water scarcity. Some villages had a water pipeline; however, irregular water supply added to water stress. Interviews consistently highlighted “water is a problem,” especially during the summer months—some linking it to future outmigration: “I feel that in coming generations nobody will stay in the mountain village because we have a water problem. It is not raining enough, so our springs have turned dry. We are completely dependent on them for our drinking water needs. In coming years, water will be an even bigger problem and that will force people to migrate.” Furthermore, talking about changes in the weather, interviewees discussed an increase in the number of cloud bursts and heavy precipitation events which led to frequent landslides, washed away villages access roads, broke terraced agricultural fields, and caused loss of life and assets.

Changes in agriculture and livelihoods

Traditional farming for subsistence has been a historical livelihood practice in mountain communities aiming at being self-sufficient. However traditional agriculture has been declining with some studies pointing to a 50% decrease in area, production, and productivity of crops (Chopra 2014; Sati and Kumar 2023). During fieldwork, there was a recurring expression among the interviewees that “kuch nahin ho raha hai yahan” which translates to ‘nothing is happening here’—speaking to a general sense of frustration that agriculture is no longer productive.

The region depends on rain-fed agriculture, making monsoon rainfall crucial for a successful harvest. Well-timed rains are essential for optimal crop yield. Over the past decade, interviewees noted untimely rainfall, with delays in the monsoon onset and either insufficient or excessive rainfall, leading to substantial losses for subsistence farmers who often did not have crop insurance. Recounting the 2019 monsoon, A5 expressed frustration over heavy rains occurring unexpectedly in October—traditionally the post-harvest season when it typically does not rain, “There is nothing happening here. I had cut grass and it is spoiled. The madua (finger millet) is infested. The rain spoilt everything. I do not feel like doing farming anymore. I do not feel like cutting grass. What is the point? It is all going to waste, what am I getting after putting in months of hard work?” During the interviews it was common to come across remarks such as—there is no point doing agriculture, nothing is growing, who is there to work in the fields? Pointing to a transpiring shift in agricultural way of life as people increasingly experience diminishing returns on input in agriculture.

In the past decade, interviewees noted that household food security has increasingly become a challenge in mountain communities due to rapid environmental changes. They emphasized the necessity of buying food as a new norm, highlighting significant shifts from previous self-sufficiency practices. As stressed by N2 “Around 20–25 years back, people who could physically work hard in the fields could manage to grow food for self-consumption for about a year. But now people have to buy food. One of the main reasons for this is weather change. Our agriculture is totally dependent on rain. If we don’t get rain, we cannot do anything about the water for the crops, secondly, the productivity of the land is limited and thirdly wild animals destroy whatever we do manage to grow. So, as a result, people are not able to meet their household food needs”. Poor and untimely rainfall along with other problems such as crop depredation by wild animals emerged as the two persistent challenges faced by farmers.

Other notable changes in agriculture encompass the diminishing interest of the youth in pursuing farming, as observed by N9: “The youth is not interested in farming. I think social aspirations have a role to play here. Not everyone who lives in the village wants to be a farmer”. Remote mountain villages that were once isolated now have increasing exposure to the outside world via cable television, phone-based and internet-based communication, igniting aspirations amongst the younger generation to migrate in pursuit of wider opportunities and the realization of personal goals.

Over the years, a waning interest in agriculture, coupled with low land productivity and the adverse effects of climate change, has resulted in the decline of the agricultural sector. This decline, in a mutually reinforcing cycle, acts as both a cause and a consequence of migration. Deteriorating agriculture leads to more migration, and as people migrate, there are fewer people to do agriculture, resulting in more migration and further compounding the challenges faced by the agriculture sector.

Migration-affected change

In Uttarakhand, there has been a notable shift in migration patterns—characterized by an increase in permanent out-migration, involving entire families leaving behind their assets, land, and houses without intending to return. This has led to discussions that “migration is a problem,” recognizing it as a significant challenge that results in depopulation, loss of human capital and culture from mountain villages.

As noted by a migration expert working for the government on preventing migration and promoting return migration “Migration is a problem because the largest area of our state is hilly and if people permanently migrate then it’s a problem. We lose our people and we lose our manpower. As people leave, the villages are getting empty and that is a security concern. I think that this is a failure of the government and the institutional system. This state was the outcome of a long agitation demanding a mountain state for the mountain people. Now those very people are migrating and not coming back. And that is a big problem” (D7). This highlights the pressing need to address evolving migration patterns in Uttarakhand through effective policy measures. It also begs the question of what is the role of policy to address the evolving migration patterns in Uttarakhand. An expert on assessing migration in the state retorts “[t]he development policy of Uttarakhand is flawed. Even though our villages are getting empty, the government does not want to invest in village development. They instead focus on migrant centers. Rural areas have fallen off their radar”. Data shows that villages that have had sustained outmigration have not only become depopulated but also lack drinking water, electricity, and road connectivity thereby further challenging the living situation of those who stay (RDMC 2018).

While migration has long been integral to mountain communities there has been a shift in how communities talk about migration. A local NGO representative working with communities on controlling migration notes, “[a]round 15 years back, if you asked communities about migration, they would refer to specific individuals (migrants), their locations, and occupations. However, nowadays, you’re likely to hear ‘woh toh palayan kar gaye’ (they have migrated permanently)” (D14). Palayan in Hindi means migration. Notably, local communities did not use this term in the past, despite prevalent migration. However, it is now specifically used to refer to permanent migration, diverging from its broader meaning. This linguistic change may also mirror a shift in migration patterns, where earlier individual family members migrated for employment and returned to their native areas, in contrast to the current trend of entire families migrating permanently.

Other changes include climate change becoming an important factor in migration decisions. Noting the complexity of migration, an expert notes, “Our migration is a livelihood constraint triggered migration. There are no means of income in the mountains and there is poverty. These three factors have historically led to outmigration. In the last decade climate change impacts have become an emerging driver for migration as it directly affects the agro-pastoral base of the population” (N1). Therefore, the evolving migration landscape in Uttarakhand encompasses complex interactions between traditional livelihood constraints, economic factors, and the emerging influence of climate change on migration patterns.

Social changes

Multiple forces of change are acting on the hill and mountain communities of Uttarakhand. Migration, globalisation, internet-based communication are driving significant shifts in the societal fabric.

Migration has resulted in the disruption of the traditional division of labour and responsibilities amongst younger and elderly women, particularly between the mother-in-law and daughter-in-law. In the past, when men were the primary migrants, the women who remained in the village, especially younger women, assumed heavier workloads and worked longer hours as compared to their elderly counterparts. However, the current trend reveals a shift as younger women now migrate with their husbands. This change in marital residence has disrupted established patterns, expectations, and division of work within households. The elderly women who stay are burdened with household tasks, experiencing persistent or even increasing responsibilities. As shared by A4, “So much has changed. What should I say, bad times have come. Today young girls after they get married want to migrate immediately with their husbands. They do not want to stay in the village. They want to escape their responsibilities. Earlier only men were migrating, we women were in the village taking care of everything. So the household tasks for me and my mother-in-law were well defined. But now no such thing exists. I am doing the same amount of work as I was doing 40 years ago as my daughter-in-law has migrated”. The quote highlights how outmigration has led to a significant shift in established household expectations and order, altering the dynamics of rural life.

Furthermore, migration has had profound effects on the social structure, disrupting community norms, and challenging traditional values. As more people migrate, interviewees reported a decline in respect for the caste system, which serves as both a social stratification system and a core value in traditional ways of life. Noting such changes PG3 shared “Earlier we had what we call a samaj (community) which has its rules of conduct. Now people don’t observe respect. They don’t observe caste differences. In fact they don’t know what the difference is! People no longer know their dharam (duty) and karam (action). We are living in Kalyug (age of darkness)”. Traditionally, the caste system played a crucial role in shaping social relationships, occupations, and hierarchies within communities. However, increased migration has reshaped the social fabric, altering traditional social orders and relationships within communities.

Disintegration of social structures has far-reaching implications for community dynamics potentially influencing how individuals perceive and interact with each other in the evolving social landscape. N12 elaborates on the shift in communal values and behaviour patterns “In olden times, we had prem bhav (care towards each other). Now people have become self-oriented and there is a sort of competition that I am better than you. Earlier people lived in unity and were there for each other in challenging times like a drought or joyous occasions like weddings. Now people have migrated, taking their individual paths. When I made my house, around 30 years ago, people wanted to make houses next to each other, thinking I will have good neighbours, but now people want to live far from each other where they can control everything”. This indicates a societal transformation in rural mountain communities. It signifies the erosion of traditional communal values, impacting not only social interactions but also reshaping the fabric of community and kinship integral to rural mountain communities (Mishra 2018).

Discussion and conclusion

This study examines staying populations who are often ‘invisible’ in climate-migration research and data collection (Borderon et al. 2021, pp. 2–4). Specifically, the focus is on remote and hard-to-reach mountain communities in the Himalayas, which are underrepresented as compared to more accessible populations (Manton and Stevenson 2014; McDowell et al. 2021, 2014). Evidence is presented on the impacts of migration in staying agrarian Himalayan communities experiencing sustained outmigration and effects of climate change. To draw implications in the context of climate adaptation, the analysis is extended to weather change, agricultural shifts, and social transformations—that are found to undermine the adaptive capacity to cope with climate risks.

In Uttarakhand, communities describe migration as good, bad, and necessary, with a majority noting (46%) negative impacts. While migration has led to skill development, opportunities outside of agriculture, and remittances—a key positive impact—a closer look through a climate lens reveals that remittances are not used for climate change adaptation as the majority (81%) of remittances are used for meeting everyday household needs, echoing findings from other studies in the region (Jacobson et al. 2019; Jain 2010; Khanal et al. 2015; Mamgain and Reddy 2016). Contrary to studies suggesting that remittances can offset migration’s negative impacts, such as loss of labour (de Haas 2007), this does not happen in Uttarakhand (Mamgain and Reddy 2016). Here migration has led to fewer people doing agriculture, loss of community and collective action, disrupted household structures, increased tasks for women, mental health impacts for the elderly, and changes in village demographics—all of which have been shown to undermine the adaptive capacity of rural mountain communities in effectively responding to climate risks (Ghimire et al. 2021; Jacobson et al. 2019; Jha et al. 2021; McLeman 2010; Szaboova et al. 2023; Vinke et al. 2020). Findings here resonate with earlier studies that note “[i]t is unlikely that migration will make a significant contribution to building livelihood resilience in the context of climate change in remote Himalayan farming communities” (Gautam 2017, p. 436) as “climate adaptation is rarely the first priority of migrant households”(Siddiqui et al. 2019b, p. 519).

In addition to financial remittances, migration also yields social remittances—values, ideas, skills, information, and knowledge acquired in migrant destinations. When focusing on skills acquired through migration, this research reveals a challenge—gained skills often struggle to find applicability in the place of origin, particularly for income generation, due to a lack of a conducive environment. This resonates with findings from Szaboova et al. 2023, who emphasize the impediment of acquired skills being ‘not compatible with and transferable to the origin context’ (p.624) thereby undermining the potential of contributing to the adaptive capacity of staying populations.

In light of these observations, caution is necessary against ‘remittances euphoria’ (Bettini and Gioli 2016, p. 6) that tends to exaggerate the role of remittances in financing climate adaptation (Bendandi and Pauw 2016; Musah-Surugu and Anuga 2023) while neglecting the contextual factors that determine their impact. Hence, a narrow focus on remittances, where migrants assume the role of climate finance providers rather than governments, perpetuates the notion of ‘self-adaptation’ (Bettini 2017, p. 36). This perspective diverts attention away from the essential role of the state in financing climate adaptation, undermining the broader collective responsibility in addressing climate challenges and reproducing a neoliberal economic agenda (Bettini 2017; Bettini and Gioli 2016).

In addition to migration impacts, staying communities in Uttarakhand face other wider challenges such as heightened food and water insecurity due to climate change, declining agricultural output, transition from farm to wage-based activities. These challenges are further compounded by migration-affected social and cultural changes, loss of community, decline in collective action to mitigate crisis and gradual withdrawal of the state from providing basic infrastructure. Together, these interconnected factors have been shown to undermine the adaptive capacity of communities to effectively respond to climate risks (Adger 2003; Jacobson et al. 2019; Jha et al. 2021; McLeman 2010; Szaboova et al. 2023; Vinke et al. 2020).

While these results cannot be generalised as they draw on data from a single case, they are significant as they add to the understanding of how migration impacts are experienced by staying populations affected by climate change in an under-studied region. Drawing on the findings of this study, several policy implications emerge.

First, policy needs to address the specific needs of vulnerable population groups such as the elderly and women who are often the ones who stay. Second, policy must ensure that basic infrastructure such as primary health care centers, schools, electricity, road maintenance and water supply is available and functioning - this is imperative for staying populations. Third, challenges in the agriculture sector demand multi-faceted support ranging from the availability of adequate labour, crop insurance, information about climate-resilient crops, to supporting alternative livelihoods such as dairy, horticulture, and medicinal plants. Fourth, communities in Uttarakhand are facing multiple forces of change including uncertain weather conditions, disrupted social structures, declining agriculture, and the impacts of permanent migration. These interconnected ‘change processes’ influence the capacity to cope and adapt to climate change. Addressing these transformations in policy interventions and planning is crucial for the well-being and sustainability of staying populations. Lastly, migration outcomes may not effectively enhance adaptive capacity unless supported by policy mechanisms that can maximise the benefits of migration for staying communities. Developing specific mechanisms, backed by policy, to enable the ‘triple win’ (Sakdapolrak et al. 2023, p. 87) of ‘migration as adaptation’ for staying communities, could be a step in this direction. As emphasised by the Foresight report, the impact of migration on staying populations—whether it presents opportunities or challenges - is contingent upon whether “policy has enabled people to build on the opportunities which migration provides” (Foresight 2011, p. 118). Furthermore, addressing existing development gaps through robust policy measures is crucial. Without such support, migration can reinforce existing vulnerabilities (Vinke et al. 2020).

Staying populations demand further attention in climate-migration research. The insights of this study are relevant to other mountainous regions where 75% of the population lives in rural settings with high dependence on natural resources and increasing migration pressures (Flavell et al. 2020; Mishra et al. 2019; Siddiqui et al. 2019b). In terms of relevance, this study demonstrates that the impacts of migration on staying populations are multifaceted. They are not limited to remittances but are spread out affecting social structures, household configurations, agrarian livelihoods, mental health, local cultures, traditional values, social cohesion, community, and collective action—all of which shape adaptive capacity to climate change. These findings are also relevant for the ongoing work of the Warsaw International Mechanism on Loss and Damage which is currently assessing the existing evidence on non-economic losses from human mobility in the context of climate change (UNFCCC 2024). Addressing these diverse impacts is crucial for maximizing the positive outcomes of migration. Neglecting to do so, staying populations could experience migration as “actively constraining and limiting of their present and future lives” (Phongsiri et al. 2023, p. 18). Therefore, it is imperative for policy, practice, and research to comprehensively address these multifaceted impacts.

Data availability

Data availability is restricted due to the provisions outlined in the data protection agreement. In accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) of the European Parliament and the Council 2016/679, measures are taken to anonymize and uphold the confidentiality of interview data. Consequently, the qualitative data gathered from interviews cannot be shared.

References

Adger WN (2003) Social capital, collective action, and adaptation to climate change. Econ Geogr 79:387–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2003.tb00220.x

Adger WN, De Campos RS, Siddiqui T, Gavonel MF, Szaboova L, Rocky MH, Bhuiyan MRA, Billah T (2021) Human security of urban migrant populations affected by length of residence and environmental hazards. J Peace Res 58:50–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343320973717

Asthana V (2012) A gendered analysis of the tehri dam project. Econ Political Wkly 47:96–102

Awasthi I, Mehta BS (2020) Forced out-migration from hill regions and return migration during the pandemic: evidence from Uttarakhand. Ind J Labour Econ 63:1107–1124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-020-00291-w

Ayeb‐Karlsson S, Baldwin AW, Kniveton D (2022) Who is the climate‐induced trapped figure? WIREs Clim Change 13:e803. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.803

Banerjee S, Black R, Kniveton D, Kollmair M (2014) The Changing Hindu Kush Himalayas: Environmental Change and Migration, in: Piguet, E., Laczko, F. (Eds.), People on the move in a changing climate: the regional impact of environmental change on migration. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, pp. 205–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6985-4_9

Banerjee S, Gerlitz J-Y, Hoermann B (2011) Labour migration as a response strategy to water hazards in the Hindu Kush-Himalayas. ICIMOD, Nepal

Banerjee S, Kniveton D, Black R, Bisht S, Das PJ, Mahapatra B, Tuladhar S (2017) Do Financial Remittances Build Household- Level Adaptive Capacity? (KNOMAD Working Paper 18). World Bank, Washington DC. Available at: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099614008232413819/pdf/IDU12e70704c13c09144ad18b9c1f04108f6dedc.pdf

Beine M, Jeusette L (2021) A meta-analysis of the literature on climate change and migration. J Dem Econ 87:293–344. https://doi.org/10.1017/dem.2019.22

Bendandi B, Pauw P (2016) Remittances for Adaptation: An ‘Alternative Source’ of International Climate Finance?, in: Milan, A., Schraven, B., Warner, K., Cascone, N. (Eds.), Migration, risk management and climate change: evidence and policy responses, global migration issues. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 195–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-42922-9_10

Benveniste H, Oppenheimer M, Fleurbaey M (2022) Climate change increases resource-constrained international immobility. Nat Clim Chang 12:634–641. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01401-w

Bettini G (2017) Where next? Climate change, migration, and the (bio)politics of adaptation. Glob Policy 8:33–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12404

Bettini G, Gioli G (2016) Waltz with development: insights on the developmentalization of climate-induced migration. Migr Dev 5:171–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2015.1096143

Bhattacherjee A (2012) Social Science Research: Principles, Methods, and Practices., Textbooks Collection. 3. ed. Global Text Project, North Charleston

Biella R, Hoffmann R, Upadhyay H (2022) Climate, agriculture, and migration: exploring the vulnerability and outmigration nexus in the Indian Himalayan Region. Mt Res Dev 42. https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-21-00058.1

Bogner A, Littig B, Menz W (2009) Introduction: Expert Interviews — An Introduction to a New Methodological Debate. In: Bogner A, Littig B, Menz W (eds) Interviewing Experts. Palgrave Macmillan, UK, London, pp 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230244276_1

Bora RS (1996) Himalayan Out-migration. Sage Publication, New Delhi

Borderon M, Best KB, Bailey K, Hopping DL, Dove M, Cervantes de Blois CL (2021) The risks of invisibilization of populations and places in environment-migration research. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8:314. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00999-0

Cappelli F (2023) Investigating the origins of differentiated vulnerabilities to climate change through the lenses of the Capability Approach. Econ Polit 40:1051–1074. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-023-00300-3

Cardona O-D, Van Aalst MK, Birkmann J, Fordham M, McGregor G, Perez R, Pulwarty RS, Schipper ELF, Sinh BT, Décamps H, Keim M, Davis I, Ebi KL, Lavell A, Mechler R, Murray V, Pelling M, Pohl J, Smith A-O, Thomalla F (2012) Determinants of Risk: Exposure and Vulnerability, in: Field CB, Barros V, Stocker TF, Dahe Q (Eds.), Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation. Cambridge University Press, pp. 65–108. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139177245.005

Carvajal L, Pereira I (2010) Evidence on the Link between Migration, Climate Shocks, and Adaptive Capacity, in: Fuentes-Nieva R, Seck PA (Eds.), Risk, shocks, and human development. Palgrave Macmillan UK, London, pp. 257–283. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230274129_11

Census (2011) A-1 Number Of Villages, Towns, Households, Population And Area. Government of India. Office of The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India

Charmaz K (2015) Grounded Theory: Methodology and Theory Construction, in: International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. Elsevier, pp. 402–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.44029-8

Chauhan N, Shukla R, Joshi PK (2020) Assessing impact of varied social and ecological conditions on inherent vulnerability of Himalayan agriculture communities. Hum Ecol Risk Assess Int J 26:2628–2645. https://doi.org/10.1080/10807039.2019.1675494

Chopra R (2014) Uttarakhand: Development and Ecological Sustainability. Oxfam India. Available at: https://policy-practice.oxfam.org/resources/uttarakhand-development-and-ecological-sustainability-346619/

Cissé G, McLeman R, Adams H, Aldunce P, Bowen K, Campbell-Lendrum D, Clayton S, Ebi KL, Hess JJ, Huang C, Liu Q, McGregor JA, Semenza J, Tirado MC (2022) Health, Wellbeing, and the Changing Structure of Communities. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC, Cambridge University Press. In Press

Corbin JM, Strauss AL (2015) Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory, Fourth edition. ed. SAGE, Los Angeles

Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL (2018) Designing and conducting mixed methods research, Third Edition. ed. SAGE, Los Angeles

Cundill G, Singh C, Adger WN, Safra de Campos R, Vincent K, Tebboth M, Maharjan A (2021) Toward a climate mobilities research agenda: intersectionality, immobility, and policy responses. Glob Environ Change 69:102315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102315

Das L, Meher JK (2019) Drivers of climate over the Western Himalayan region of India: a review. Earth-Sci Rev 198:102935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2019.102935

de Haas H (2021) A theory of migration: the aspirations-capabilities framework. CMS 9:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-020-00210-4

de Haas H (2007) Remittances, migration and social development (No. Social Policy And Development Programme paper number 34). United Nations Research Institute for Social Development

Deshingkar P (2012) Environmental risk, resilience and migration: implications for natural resource management and agriculture. Environ Res Lett 7:015603. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/7/1/015603

Döringer S (2021) ‘The problem-centred expert interview’. Combining qualitative interviewing approaches for investigating implicit expert knowledge. Int J Soc Res Methodol 24:265–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2020.1766777

GoI DoRD (2011) Socio- Economic and Caste Census. Department of Rural Development, Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India. Available at: https://secc.gov.in/getTypeOfHHdNationalReport.htm

Entzinger H, Scholten P (2022) The role of migration in enhancing resilience to climate change. Migr Stud 10:24–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnac006

Flavell A, Melde S, Milan A (2020) Migration, environment and climate change: Impacts (No. FB000245/2,ENG). Umweltbundesamt: Germany. Available at: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/1410/publikationen/2020-03-04_texte_43-2020_migration-impacts_2.pdf

Foresight (2011) Migration and Global Environmental Change (2011) Final Project Report. Government Office for Science, London

Gautam Y (2017) Seasonal migration and livelihood resilience in the face of climate change in Nepal. Mt Res Dev 37:436. https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-17-00035.1

Gemenne F, Blocher J (2017) How can migration serve adaptation to climate change? Challenges to fleshing out a policy ideal. Geogr J 183:336–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12205

Ghimire DJ, Axinn WG, Bhandari P (2021) Social change, out-migration, and exit from farming in Nepal. Popul Environ 42:302–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-020-00363-5

Ghosh RC, Orchiston C (2022) A systematic review of climate migration research: gaps in existing literature. SN Soc Sci 2:47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-022-00341-8

Giannelli GC, Canessa E (2021) After the flood: migration and remittances as coping strategies of rural Bangladeshi households. Econ Dev Cult Change 713939. https://doi.org/10.1086/713939

Glaser BG, Strauss AL (1967) The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research, 5. paperback print. ed. Aldine Transaction, New Brunswick

GU (2018a) Human Development Report of State of Uttarakhand. Department of Planning, Government of Uttarakhand, India. Available at: https://des.uk.gov.in/department6/library_file/file-22-06-2022-04-55-43.pdf

GU (2018b) State of the Environment Report 2018. Uttarakhand Environment Protection and Pollution Control Board, India. Available at: https://ueppcb.uk.gov.in/files/SoER.pdf

GU (2017) Uttarakhand State Economic Survey 2016–17. Planning Commission, Government of Uttarakhand, India. Available at: http://des.uk.gov.in/files/Economic_Survey_2016-17.pdf

GU (2014) Uttarakhand action plan on climate change: transforming crisis to opportunity. Government of Uttarakhand, India. Available at: https://moef.gov.in/uploads/2017/08/Uttarakhand-SAPCC.pdf

Guhathakurta P, Bandgar A, Menon P, Prasad AK, Sable ST, Sangwan N (2020) Observed Rainfall Variability and Changes Over Uttarakhand State (ESSO/IMD/HS/Rainfall Variability/28(2020)/52). Indian Meteorological Department

Hoffmann R, Dimitrova A, Muttarak R, Crespo Cuaresma J, Peisker J (2020) A meta-analysis of country-level studies on environmental change and migration. Nat Clim Chang 10:904–912. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0898-6

ICIMOD (2023) Water, ice, society, and ecosystems in the Hindu Kush Himalaya: an outlook. International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD). https://doi.org/10.53055/ICIMOD.1028

INRM (2016) Climate Change Risks and Opportunities in Uttarakhand, India: Technical Report on District (Block) Level Vulnerability for Select Sectors (Deliverable#5 Draft Report). INRM Consultants Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi, India

Jacobson C, Crevello S, Chea C, Jarihani B (2019) When is migration a maladaptive response to climate change? Reg Environ Change 19:101–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-018-1387-6

Jain A (2010) Labour Migration and Remittances in Uttarakhand. International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, Kathmandu, Nepal

Jaquet S, Shrestha G, Kohler T, Schwilch G (2016) The effects of migration on livelihoods, land management, and vulnerability to natural disasters in the Harpan Watershed in Western Nepal. Mt Res Dev 36:494–505. https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-16-00034.1

Jha CK, Gupta V, Chattopadhyay U, Amarayil Sreeraman B (2018) Migration as adaptation strategy to cope with climate change: a study of farmers’ migration in rural India. IJCCSM 10:121–141. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCCSM-03-2017-0059

Jha SK, Negi AK, Alatalo JM, Negi RS (2021) Socio-ecological vulnerability and resilience of mountain communities residing in capital-constrained environments. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change 26:38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-021-09974-1

Kaul V, Thornton TF (2014) Resilience and adaptation to extremes in a changing Himalayan environment. Reg Environ Change 14:683–698. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-013-0526-3

Khanal U, Alam K, Khanal RC, Regmi PP (2015) Implications of out-migration in rural agriculture: a case study of Manapang Village, Tanahun, Nepal. J Dev Areas 49:331–352. https://doi.org/10.1353/jda.2015.0012

Knott E, Rao AH, Summers K, Teeger C (2022) Interviews in the social sciences. Nat Rev Methods Prim 2:73. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43586-022-00150-6

Krishnan R, Shrestha AB, Ren G, Rajbhandari R, Saeed S, Sanjay J, Syed Md.A, Vellore R, Xu Y, You Q, Ren Y (2019) Unravelling Climate Change in the Hindu Kush Himalaya: Rapid Warming in the Mountains and Increasing Extremes, in: Wester P, Mishra A, Mukherji A, Shrestha, Bhakta A (Eds.), The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment: Mountains, Climate Change, Sustainability and People. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 57–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92288-1_3

Kulkarni A, Patwardhan S, Kumar KK, Ashok K, Krishnan R (2013) Projected climate change in the Hindu Kush–Himalayan Region by using the high-resolution regional climate model PRECIS. Mt Res Dev 33:142–151. https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-11-00131.1

Maduekwe NI, Adesina FA (2022) Can remittances contribute to financing climate actions in developing countries? Evidence from analyses of households’ climate hazard exposure and adaptation actors in SE Nigeria. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change 27:10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-021-09987-w

Maharjan A, de Campos RS, Singh C, Das S, Srinivas A, Bhuiyan MRA, Ishaq S, Umar MA, Dilshad T, Shrestha K, Bhadwal S, Ghosh T, Suckall N, Vincent K (2020) Migration and household adaptation in climate-sensitive hotspots in South Asia. Curr Clim Change Rep 6:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-020-00153-z

Maharjan A, Tuladhar S, Hussain A, Mishra A, Bhadwal S, Ishaq S, Saeed BA, Sachdeva I, Ahmad B, Ferdous J, Hassan SMT (2021) Can labour migration help households adapt to climate change? Evidence from four river basins in South Asia. Clim Dev 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2020.1867044

Mamgain R, Reddy DN (2016) Out-migration from the hills of Uttarakhand: magnitude, challenges and policy options. National Institute of Rural Development and Panchayati Raj, Rajendranagar Hyderabad, India. Available at: http://nirdpr.org.in/nird_docs/srsc/srscrr261016-3.pdf

Manton MJ, Stevenson LA (2014) Future Directions for Climate Research in Asia and the Pacific. Climate in Asia and the Pacific. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7338-7_7

Marandi A, Main KL (2021) Vulnerable city, recipient city, or climate destination? Towards a typology of domestic climate migration impacts in US cities. J Environ Stud Sci 11:465–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-021-00712-2

McDowell G, Stephenson E, Ford J (2014) Adaptation to climate change in glaciated mountain regions. Clim Change. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1215-z

McDowell G, Stevens M, Lesnikowski A, Huggel C, Harden A, DiBella J, Morecroft M, Kumar P, Joe ET, Bhatt ID, The Global Adaptation Mapping Initiative, (2021). Closing the Adaptation Gap in Mountains. Mt Res Dev 41. https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-21-00033.1

McLeman R (2010) Impacts of population change on vulnerability and the capacity to adapt to climate change and variability: a typology based on lessons from “a hard country. Popul Environ 31:286–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-009-0087-z

McNamara KE, Westoby R, Clissold R, Chandra A (2021) Understanding and responding to climate-driven non-economic loss and damage in the Pacific Islands. Clim Risk Manag 33:100336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2021.100336

Mehta BS (2022) Migration and COVID-19 pandemic: a study of Uttarakhand migrants in Delhi. Indian J Hum Dev 16:468–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/09737030221146373

Millán TM (2020) Regional migration, insurance and economic shocks: evidence from Nicaragua. J Dev Stud 56:2000–2029. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2019.1703956

Mishra A (2018) Changing Social Capital in the Mountains and the Implications for Adaptation Interventions: an Exploratory Analysis with Case Studies from the Hindu Kush Himalaya, in: Climate Change Governance and Adaptation. CRC Press, Boca Raton : CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, 2018., pp. 89–107. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315166704-6

Mishra A, Appadurai AN, Choudhury D, Regmi BR, Kelkar U, Alam M, Chaudhary P, Mu SS, Ahmed AU, Lotia H, Fu C, Namgyel T, Sharma U (2019) Adaptation to climate change in the Hindu Kush Himalaya: stronger action urgently needed. The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment: mountains, climate change, sustainability and people. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92288-1_13

Morse JM (1995) The significance of saturation. Qual Health Res 5:147–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973239500500201

Morten M (2019) Temporary migration and endogenous risk sharing in village India. J Political Econ 209:46

Musah-Surugu JI, Anuga SW (2023) Remittances as a Game Changer for Climate Change Adaptation Financing for the Most Vulnerable: Empirical Evidence from Northern Ghana, in: Meyer, S., Ströhle, C. (Eds.), Remittances as Social Practices and Agents of Change. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 343–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81504-2_15

Naudiyal N, Arunachalam K, Kumar U (2019) The future of mountain agriculture amidst continual farm-exit, livelihood diversification and outmigration in the Central Himalayan villages. J Mt Sci 16:755–768. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-018-5160-6

Obokata R, Veronis L, McLeman R (2014) Empirical research on international environmental migration: a systematic review. Popul Environ 36:111–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-014-0210-7

Ojha HR, Shrestha KK, Subedi YR, Shah R, Nuberg I, Heyojoo B, Cedamon E, Rigg J, Tamang S, Paudel KP, Malla Y, McManus P (2017) Agricultural land underutilisation in the hills of Nepal: Investigating socio-environmental pathways of change. J Rural Stud 53:156–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.05.012

Pandey R (2021) Male out-migration from the Himalaya: implications in gender roles and household food (in)security in the Kaligandaki Basin, Nepal. Migr Dev 10:313–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2019.1634313

Pathak S, Pant L, Maharjan A (2017) De-population trends, patterns and effects in Uttarakhand, India – a gateway to Kailash Mansarovar. International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, Kathmandu, Nepal

Patton MQ (1980) Qualitative evaluation methods. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills

Pelling M, High C (2005) Understanding adaptation: what can social capital offer assessments of adaptive capacity? Glob Environ Change 15:308–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2005.02.001

Phongsiri M, Rigg J, Salamanca A, Sripun M (2023) Mind the Gap! Revisiting the migration optimism/pessimism debate. J Ethn Migr Stud 49:4–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2023.2157577