Abstract

In the process of urbanization, the balance and/or conflict between the conservation, development, and utilization of cultural heritage has become an emergent theme. This paper explores how such a theme is manifested through discourse by analyzing the legal case of the house at No. 98, Hai’er Lane, China, which is entangled with multiple narratives of the local community, various levels of courts, and government agencies regarding the value of this site. While the contested nature of discourses lies in the power asymmetry, there is some space to pose a challenge against the dominant discourse, e.g., adopting a multi-stakeholder approach to mediate various interests of stakeholders. Besides, disputes over heritage protection and promotion need to be understood within the dominant discourses of their time. Based on such understandings, cultural heritage, if taken as a social sign, particularly for its identification and conservation, may be subject to different constructions by sign users as society progresses. Considering that heritage protection law in China places a greater emphasis on taking cultural heritage as things than orientating cultural heritage to humans, it is desirable to address intricate tensions between the conservation, development, and utilization of cultural heritage by promulgating more systematic and explicit laws and regulations that better reflect the heteroglossia of stakeholders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

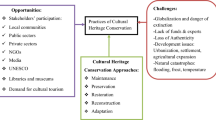

Heritage is an integral part of the sociocultural process in which it arises. As contemporary society becomes more culturally aware, research on heritage has proliferated in the past few decades (e.g., Bouvier and Wu, 2021; Smith, 2014; Waterton et al. 2006). Broadly speaking, cultural heritage is identified as the legacy of tangible and intangible resources of a group or society that is passed down from former generations due to social selection (Logan, 2007). It reflects and shapes social values, beliefs, norms, and customs (Smith, 2006), and meanwhile defines people’s identity in a community or society. Bridging the gap between the past and the present, heritage contributes valuable assets to a broader public at the local, national, and international levels by virtue of its unique socio-historical, cultural, aesthetic, scientific, and economic values (e.g., Lipe, 1984; De la Torre, 2002; Samuels, 2008). In reality, various measures have been adopted for “safeguarding, protection and maintenance of cultural heritage, property, or rights” (Wagner et al. 2021: 602) through government policies and legal instruments, as noted by Blake (2008:85).

There is no question of the value of, for example: attempting to prevent the destruction, deliberate or otherwise, of artifacts and other remains with a cultural significance during armed conflict; seeking to prevent the illicit excavation of archeological sites and control the illicit trade in cultural artifacts; or creating a mechanism for the protection and preservation of sites and monuments judged to be of “universal” significance with the States where they are located acting as trustee on behalf of the world community.

As the times progress, cultural heritage has been studied in several academic fields, such as anthropology, history, linguistics, tourism, archeology, law, architecture, and so on, which, in some degree, implies that the conservation, development, and utilization of cultural heritage is critical for developing cultural diversity and sustainability (Habibi and Ruban, 2017; Havinga et al. 2020; Tweed and Sutherland, 2007). Notwithstanding considerable differences in numerous theories and methodologies that underpin heritage studies, the research findings of legal and linguistic analyses have always been used together to explore many heritage issues, ranging from evaluating and improving cultural heritage laws to seeking solutions for conflicts in heritage identification, planning, and development.

Cultural heritage is a discourse by nature as a way of “representing aspects of the world” (Fairclough, 2003:176). Smith (2006) regarded the process of producing and reproducing heritage as discursive practices that privilege “expert values and knowledge about the past and its material manifestations” (p.4), i.e., authorized discourse, and the systematic analysis of such discourse can help us better navigate the intricate landscape of heritage studies (Waterton et al. 2006). The present paper aims to unravel how conflicting discourses in heritage management and conservation are defined and negotiated among multiple stakeholders over a legal dispute. For a profound understanding of the discursive construction process, the house at No. 98 Hai’er Lane in China was selected as a case study. To this end, the research is guided by the following two research questions: (1) What are the competing discourses regarding the demolition of the house at No. 98 Hai’er Lane? (2) How should the interests of multiple stakeholders involved in disputes over heritage identification and conservation be better addressed?

The structure of our paper is outlined as follows. We first contextualize the present study with relevant literature on heritage discourse in section 2, and then elaborate the reasons why the house at No. 98 Hai’er Lane is selected in section 3. This is followed by detailed analyses in section 4 of competing stakeholder discourses linked to the particular case. Section 5 explores how people cope with complex tensions between heritage protection and cultural rights in the Chinese context, along with some implications for future studies in the concluding part.

Literature Review

Heritage as a discursive construction

Discourse can be understood as a form of social interaction and meanwhile as “the expression and reproduction of social cognition” (Van Dijk, 2014: 12). Discourse analysis has developed into an essential area of specialty in modern academia. In practice, discourses are primarily constrained by power relations within a social order that play a decisive role in legitimating social knowledge. Thus, discourse analysis from a critical perspective tends to challenge the generally accepted ideas or practices and clarify how dominant discourses marginalize or oppress the truth. Heritage is intimately associated with discourse and discursive practices (Wu and Hou, 2015). Informed by Smith (2006) who claimed that “heritage is a discourse” (p. 272), we hold that the process of heritagization is a discursive practice.

Heritage does not merely point to unique and precious objects or resources, such as historical monuments and cultural traditions that are directly identified and acknowledged, but those whose significance is embedded in various configurations where they arise. Intertwined with ideology and power relations, heritage needs to be approached by considering situational knowledge beyond language in the sense that discourse is context-dependent (Bloor and Bloor, 2013). Tunbridge and Ashworth (1996) stressed that “the present selects an inheritance from an imagined past for current use and decides what should be passed on to an imagined future” (p.6). Now that heritage is a meaningless entity outside the discourse (Hall, 2011), people should place it under the scrutiny of the present. However, the present is a relative concept that cannot be exempt from the far-reaching influences of the past. Exploring heritage-related issues from a dynamic perspective is thus essential to better comprehend the discursive logic behind the realities. Moreover, discourse has the power to construct the episteme or structure of knowledge. Multiple scholars (Lowenthal, 1998; Cameron and Kenderdine, 2007; Waterton and Watson, 2010) have examined heritage discursive constructions by investigating how social groups’ divergent interests and ideologies shape heritage in ways that reflect power relations. People construct a discourse for their own sake, whereas they may be shaped by such discourse simultaneously, as pointed out by Cheng and Sin (2007). For practitioners of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), conflicts arising from heritage conservation should be meticulously addressed to unpack the meaning-making process and the power relations involved.

Authorized Heritage Discourse (AHD): a critical perspective to heritage studies

Based on an in-depth analysis of multiple cases from Australia, New Zealand, and so on, Smith (2006) summarized the use of heritage around the globe and developed the well-known concept of Authorized Heritage Discourse (AHD) based on a core set of principles of CDA; simply put, AHD delves into the process of negotiation that relates to social power in heritage discourse. For this reason, the knowledge of heritage is defined by key actors in the AHD community, e.g., heritage professionals and government authorities that identify, define, conserve, and utilize the heritage. This is traced back to the Western aesthetic philosophy that privileges material entities from the past. As such, AHD seeks to approach heritage “mainly for its static representation of aesthetics and monumentality” (Yan, 2015:66), while degrading the values of intangible cultural heritage, e.g., oral traditions, performing arts, rituals, knowledge, and skills to produce traditional crafts.

During the top-down hegemonic process through UNESCO and other international organizations like ICOMOS and ICCROM, the idea of AHD has gradually merged into global conservation practices. The institutional power is implemented through official documents, such as conventions, laws, declarations, treaties, charters, and agreements that exert both legal and moral force on participating parties to elucidate what heritage is and how it should be safeguarded. In other words, AHD generates a series of principles, norms, and standards to regulate social behaviors of the majority, including non-westerners, indigenous communities and peoples, etc. It is a handful of experts who have the final say in making or influencing decisions on heritage issues. Bouvier and Wu (2021) maintained that the meaning-making of UNESCO legal instruments is a sociosemiotic operation that can be understood based on contextualized information and also a process of “social dialogue and power negotiation” (Cheng and Cheng, 2012: 446; Zhao et al. 2021; Si and Liu, 2022).

Heritage protection in the legal framework

Cultural heritage protection operates within the framework of international and domestic legal systems. As a cultural legacy of humankind, heritage is in itself susceptible to extensive damage or destruction (Gomez-Heras and McCabe, 2015), denoting a necessity to undertake adequate protective measures for safeguarding historic buildings, monuments, or artifacts of cultural significance. The 1954 Hague Convention on the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict is the first comprehensive and systematic legal instrument that specifically addresses the protection of cultural property in armed conflicts. Along with the 1954 and 1999 protocols, the Convention has clarified a diverse range of obligations on state parties to negotiate competing discourses of various countries for heritage safeguarding and protection during hostilities. In the peacetime, conflicts of interest regarding heritage protection and management can be commonly observed within local discourse communities. By analyzing the dissonant heritage, Tunbridge and Ashworth (1996) claimed that the cultural, political and economic uses of heritage are linked with conflicts among stakeholders, which originate from the emphasis on producers (e.g., governments, cultural agencies, etc.) rather than consumers (e.g., local inhabitants, tourists, etc.). Herein, stakeholders refer to individuals, groups or organizations with an interest in the activity that can impact or be impacted by a decision or action (McGrath and Whitty, 2017).

While the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Cultural Relics (1982), the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage (2011), and a series of rules and regulations at the local and national levels are legally effective, the legal system for cultural heritage in China still needs further improvement due to a lack of refinement and timely update. This has attracted the attention of relevant scholars and heritage practitioners. One of their concerns is the problem of public interest, as the laws or judicial interpretations do not explicitly provide for the measurement of public interest. Besides, Maags (2018) explored how non-state stakeholders in China compete for a sense of identity to local heritage by actively engaging in the implementation of intangible cultural heritage policy, showing the public’s increasing awareness about cultural identity. Zhu’s (2018) study contributed to the knowledge about the contested nature of heritage in the urban landscape of Xi’an, China, where individuals respond to the official discourse through adaptation, unintended participation, commemoration, and resistance. Moreover, Svensson and Maags (2018) believed that the AHD in China has undergone changes due to divergent ideological thinking and socio-economic progress. Ordinary residents, local communities, and marginalized groups could make their voices heard by adapting, negotiating, or even contesting the AHD, especially during urbanization where stakeholders diverge on the values and meaning of heritage.

In recent decades, a shift has occurred in heritage management, transitioning from a predominantly “material-centric” approach to one that is “human-focused”. The shift underscores a profound realignment of mankind and nature, as posited by Ma and Cheng (2019). The present study seeks to contribute some thoughts to the academic field by examining how different discourses are negotiated through contestations, particularly focusing on the legal case pertaining to the house located at No. 98, Hai’er Lane, Hangzhou, China.

Case briefing: Qian v. Shaoshan Middle School

The case study approach enables people to obtain a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of sophisticated issues from real life. Therefore, it is widely adopted in heritage studies (see Christie, 2021; Munawar and Symonds, 2022). The reasons for analyzing the case of the house at No. 98, Hai’er Lane are illustrated below. First, the house was a historic building inhabited by local residents but yet to be designated as the cultural relic protection site. It escaped from being destroyed owing to constant efforts of local residents, making it one of the successful exemplary cases of challenging the AHD in China.Footnote 1 Second, multiple stakeholders were involved in the conflict over its cultural identity, which can shed light on how competing discourses are properly addressed. Third, this legal dispute has noteworthy social influences on heritage protection across the nation, e.g., promoting the revision and refinement of relevant heritage laws and regulations.Footnote 2 Below is a thorough description of the case, which relates to legal controversies worth discussing.

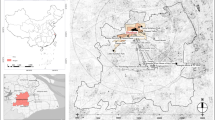

Hai’er Lane is situated at the center of Hangzhou, China, connecting Wulin Road and North Zhongshan Road. As one of the historical remains, its fame is primarily attributed to Lu You (A.D. 1125–1209), a renowned patriotic poet in the Southern Song Dynasty. According to relevant records, he once resided in Hai’er Lane during several trips to Lin’an (presently Hangzhou), where one of his representative poems, Clearing up after Spring Rain at Lin’an, was conceived. However, the building at No. 98, Hai’er Lane could have vanished without the unremitting efforts of Xiyao Qian, the owner of the ancient house, who proposed to the authorities that it was the former residence of Lu You, shortly after the government’s authorization of the expansion of Shaoshan Middle School (now known as Fengqi Middle School) through the demolition of adjacent structures in 1999. While the Hangzhou Municipal Bureau of Gardening and Cultural Relics found that the house did not exactly match the location described in the literature, it was identified as a relic of the late Qing Dynasty and the early Republic of China with a particular reservation value, as evidenced by the proof of Zhejiang Provincial Bureau of Cultural Relics (see [2001] No. 147 Reply). Considering this, the Hangzhou Urban and Rural Construction Committee temporarily kept the building intact and made appropriate repairs. But local households were still required to resettle in other places in compliance with urban planning. Two years passed before the debate over whether to tear down the house had been resolved.

The Hangzhou Municipal Government issued a similar statement for the second time in September, 2001, claiming that the house at No. 98, Hai’er Lane was neither the former residence of Lu You (a famous poet) nor a cultural preservation site, and agreed to expedite the relocation of the building (see [2001] No. 213 Reply). Xiyao Qian felt strongly reluctant to leave because of his strong emotional attachment. In March 2002, the Shaoshan Middle School sued him in the Xiacheng District People’s Court, which ruled that Qian vacated the house within ten days and handed it over to the Shaoshan Middle School for demolition. Feeling an ethical pressure, Qian immediately appealed the court’s decision (see No. 298 Civil Judgment).Footnote 3 Some of the testimony delivered by his lawyer during the second trial is shown below.Footnote 4

The appellant’s purpose of filing the lawsuit is in no way to obtain additional personal benefits but to protect the national cultural heritage through legal settlement. As we all know, if the ancient house is demolished, the appellant will not suffer direct economic loss. Instead, he will substitute the old house with a new one through government compensation, enhancing the quality of life accordingly. However, as a law-abiding citizen (the 34th generation descendant of King Wusu Qian), he understands his historical responsibility and legal obligations.

In the meantime, Professor Yisan Ruan, Director of the Research Center for National Historical and Cultural Cities at Tongji University, conducted an on-site appraisal of the old house after hearing the news and concluded that it was a building in the middle and late Qing Dynasty, renovated and repaired continuously on the original site. As a historical landmark in Hangzhou, it was worth preserving no matter whether it was Lu You’s former residence. Many professors at Zhejiang University also advocated that the building was an ancient living museum. As such, the Zhejiang Provincial Bureau of Cultural Relics made a special request to preserve the building. That being the case, Guoping Wang, the then Secretary of the Hangzhou Municipal Party Committee of CPC, gave instructions to amend the Historic Cultural City Conservation Plan as soon as possible, demanding that all the approved old city renovation projects should be thoroughly examined and reviewed, whereas unapproved projects be suspended until revisions are completed. Hangzhou Municipal Intermediate People’s Court rejected the Shaoshan Middle School’s litigation request as a final judgement in September, 2002.Footnote 5

Since 2007, the house has been renovated several times. The exterior door demolished during the urban renewal project was rebuilt and the bluestone octagonal well excavated in the Ming Dynasty was covered with an iron cage for conservation purposes (cf. Fig. 1).Footnote 6 It was selected as one of the first batch of historical buildings to be protected in Hangzhou’s main urban area by Hangzhou Municipal People’s Government in 2004 and started to be maintained by Xiacheng District Cultural Protection Office of Hangzhou in 2005. The cultural tourist attraction is now open to the general public for free. The first half of the ancient building is made into the “Lu You’s Memorial Hall”, exhibiting the poet’s life experience and literary works, while the second half is used as the “Xiacheng Cultural and Historical Museum”, displaying historical stories and cultural relics relating to Xiacheng District (presently Gongshu District, cf. Fig. 2).Footnote 7

Competing stakeholder discourses: multiple narratives of local inhabitants, various courts, and government agencies

Based on legal judgments, interview transcripts, and field visits, we have identified three categories of narratives revolving around the prospects of the house at No. 98, Hai’er Lane during the urban planning, i.e., the local community, lower and higher courts, and the government, respectively. Voices across participating actors are interwoven, indicating the contested nature of heritage discourses under discussion.

Conflicting interests at the community level

Hai’er Lane is located in the prime area of Hangzhou, and the house price nearby had already climbed up to a record high of around 6000 RMB per square meter back then. In pursuit of better financial returns, the housing authority was eager to reconstruct old blocks and provided local residents with preferential policies for demolition and relocation. Unlike Qian, all the other households along Hai’er Lane moved out straight away in line with the government requirements, mainly because these dilapidated houses were not suitable for living anymore (e.g., it is sweltering in summer and frigid in winter). Local inhabitants were more concerned about their living comfort than the historical significance of the residential area. Some even tried to persuade Qian to succumb to the government order by considering the lucrative compensation plan. But Qian insisted that his ancestors bought the house for the reason of Lu You. Holding such a strong belief, he filed a lawsuit against the Shaoshan Middle School that claimed to have the official right to occupy the land.

Due to the existence of dissonant voices in local community, three households including Qian were given the title of “Nail Household”, a Chinese term used to refer to people who are reluctant to move out of the private property to make room for the real estate development. Qian became a single-handed elderly man struggling for over four years to gain recognition for the house, which shows the limited power of individuals in protecting a heritage site. Ordinary people are oftentimes disempowered in the process of heritage identification and conservation (Yan, 2015), though their inclusive participation in the formulation and implementation of policies may affect the well-being as well as facilitate the transfer of knowledge from older to younger generations. What is more, heritage conservation and urban planning/development do not necessarily conflict with each other (Mubaideen and Al Kurdi, 2017). But lack of public awareness of heritage conservation is the immediate cause of cognitive dissonance in the host community. The dispute does not only relate to discrepancies within the group of local residents but to those between local residents and other social groups, e.g., the Shaoshan Middle School, driven by divergent interests and needs.

Conflicting interests at the court level

Since Qian could not reach a consensus with the Shaoshan Middle School over whether to demolish the house, the dispute evolved into a civil case that had to be handled by the court. But law failed to protect the role and rights of affected groups. In March 2002, the school filed a lawsuit against Qian for refusing to sign the house demolition and resettlement agreement. On June 14, the Xiacheng District People’s Court of Hangzhou ruled in favor of the school by identifying with the government decision, as illustrated below (Ju, 2018; Dundon, 2024).

The dilapidated building is neither a former residence of Lu You nor a cultural protection site. There are numerous cracks in the mud walls up to 4 meters, and termites have seriously eroded the wooden structure so it runs a high risk of collapse in bad weather… Considering the above, the municipal government has decided to demolish the building on July 4th, 2001. The cultural administration department will collect some of its pieces.

Based on his cognitive appraisal, Ruan realized that the power of heritage professionals and mass media was not enough to turn around the court’s decision, so he solicited support and solidarity of senior leaders within government authorities (Sarangi and Slembrouck, 1996). Hangzhou Municipal Intermediate People’s Court later enforced an opposite adjudication decision that abrogated the first-instance judgment (No. 298 Civil Judgment) of the Xiacheng District People’s Court, following the normative order. Consequently, the lawsuit process involves not only the conflicting interests between the plaintiff, i.e., the Shaoshan Middle School, and the defendant, i.e., Xiyao Qian, but also those between the lower court and the higher court, among which the government played a mediating role in reconciling two distinct perceptions and judgments. This corroborates the claim that “Tensions between expert and non-expert perspectives are manifest in the different values, interests, and identities expressed in heritage identification and decision-making processes” (Avrami and Mason, 2019: 20–21). Our analysis also shows that law, as an ideological product of the time, is shaped by the dominant AHD, which lays out what is considered acceptable and reasonable in a discursive context (Jessup and Rubenstein, 2012).

Conflicting interests at the government level

As a result of the centralized and profit-driven decision-making system, cultural heritage identification and protection could easily evolve into a top-down practice that excludes local communities (Li et al. 2020; Verdini et al. 2017). When implementing the revenue-generating urban renewal project, the municipal government did not assess an inhabited area systematically and comprehensively in terms of its social, economic, historical, and cultural influences. On February 12, 1999, the Hangzhou Cultural Preservation Institute refuted that the house was the former residence of Lu You; instead, it was designated as an architecture built between the late Qing Dynasty and the early Ming Dynasty without much conservation value. This directly caused part of the building to be bulldozed. As the house at No. 98, Hai’er Lane attracted widespread public attention, government officials began to reflect on whether it was rational to demolish the house with discretion by weighing up potential damage. In June, the Bureau of Gardening and Cultural Relics gathered opinions from all sides and affirmed that the building should be protected based on its historical significance.

However, the demolition plan was restarted in 2001 to answer the call of the school for expansion, which shows there exist conflicts between the housing management department and the cultural affairs department over the resolution. Moreover, even the same government departments may adopt contradictory attitudes towards the heritage site before and after the dispute. This provides a window into the irreplaceable role of higher-ranking authorities in turning it around, which is the most dominant and influential discourse in heritage management practices. Essentially, the uneven distribution of power within the hierarchy leads to divergent behavioral manifestations, as each department used power to ensure the benefits of an organization in their own way. It stands to reason that “the particular use each group makes of the AHD to take meaning from the landscape often clashes with the aspirations and needs of other groups” (Smith 2006:173). But the government should be regarded as a vital stakeholder holistically because the consistency of interest is ultimately made possible through the hierarchical structure as it is.

Discussion

Cultural identity, professional knowledge, and negotiation of power

In the face of repeated relocation notices, Qian’s persistence played a decisive role in determining the fate of the old house. He tried every means to seek support from heritage professionals to voice his opinion on the historic residence and appealed to higher authorities for help without hesitation. One reason for this is that he keenly realized that once damaged, the heritage would vanish for good, especially after the demolition of all the other buildings along the Hai’er Lane. Throughout the entire conservation process, the cultural identity of this heritage site becomes a focus of debate. While collected memory and local distinctiveness are of paramount importance to him (Parkinson et al. 2016), Qian’s call for heritage protection was not appropriately answered at first. This demonstrates that local inhabitants as one of the social actors do not warrant sufficient attention regarding heritage conservation. Prof. Ruan made the following closing remarks at a seminar (Ju, 2018), where professionals in the heritage field gathered to evaluate the house.

The overall style of the old house is characteristic of the middle and late Qing Dynasty. The current building has been constantly rebuilt and repaired on the original site, which has left abundant historical and cultural information. Besides the architectural relics of walls in the Song Dynasty, there also exist the column bases and “clamshell windows” of the Ming Dynasty and carved doors and windows with English characters from the Qing Dynasty, which are very rare… Undoubtedly, the house at No. 98, Hai’er Lane is an essential historical “landmark” in Hangzhou, which is worth thousands of times more than a new luxury mansion.

Heritage narratives and practices involve varying subjective interpretations of a particular topic or issue. What underlies the dispute over heritage conservation is “the asymmetry of stakeholders’ involvement in the assessment for cultural built heritage” (Amar and Armitage, 2019: 237). This is reflected in the policy-making process where stakeholders with superior power tend to measure and determine heritage value in their favor. In contrast, stakeholders with inferior power are placed in a relatively disadvantageous position, so they may turn to the discourse of resistance (Wilson and Stapleton, 2007). In this particular case, we need to notice the degree to which the outsiders acknowledge folk memories and temporal experiences of local inhabitants. The elite discourse of heritage experts bridges the gap between the ‘official’ AHD and the lay discourse of local community through the integration and cooperation of all stakeholders, which significantly impacts heritage production and consumption. Heritage is universally recognized as an invaluable resource that necessitates the protection and management of processionals, including architects, historians, and archeologists. These people are largely responsible for the making of AHD based on archeological knowledge and practice. The key point here lies in the crucial role that heritage experts play within the AHD, ensuring that the established frameworks remain fundamentally stable, and this, in turn, guarantees that the AHD retains its enduring utility and authoritative standing for the state to make things go smoothly (Smith, 2012). The heritageisation of the house at No. 98, Hai’er Lane reflects a contemporary landscape of cultural power dynamics from a multicultural discourse perspective, which involves self-perception and the struggle for cultural identity. By providing insight into the manipulation of heritage discourse, the findings of our study resonate with Harvey’s (2001) view that cultural heritage is not a primordial phenomenon but a social selection in accordance with practical needs (Tunbridge and Ashworth, 1996); hence, the values of heritage are selective, subjective, and situational (Avrami and Mason, 2019).

From the above, the focus of heritage was once placed on the materiality of the house rather than on people who originally resided in the locality. In other words, the ‘archeological’ version prevailed over the ‘anthropic’ version in the early process. Tradition has it that archeologists define heritage as places, monuments, or sites they study and care for (Carman, 2002), which is echoed in the AHD. The case of Lijiang, China also exemplifies the irreversible damage that can arise as a consequence of the narrow scope of China’s heritage preservation practices, which place greater emphasis on material legacies than on people and communities associated with such heritage (Gruber, 2017). However, as society has changed profoundly over the past few decades, heritage values are becoming increasingly politicized, thereby maintaining the social hierarchy and legitimizing the power of governing authorities. Whether a historic building is designated as heritage is mainly contingent upon key stakeholders who have vested interests in it during social control and regulation, which is by itself an area of struggle (Cheng and Wu, 2021; Sarangi and Slembrouck, 1996; Wagner and Cheng, 2011; Wu, 2023). The Hai’er Lane case witnessed the victory of individuals, but more importantly, a significant shift from a material-centered perspective to a people-centered perspective in heritage management (Bouvier and Wu, 2021). Cultural heritage is created by and for people. Anyone who has access to it may have a role to play, including local residents, heritage professionals, government officials, or the general public. The dynamic and complex interactions among myriad actors are driving forces in determining the cultural significance of heritage sites. Nevertheless, the coexistence and conflict of various interests and narratives are characteristic of the evolution of heritage recognition, conservation, and promotion in the years to come.

Adopting a multi-stakeholder approach to address competing discourses

The juxtaposition of clashing perceptions about the cultural significance of the house leads to the emergence of competing heritage discourses, showing how “different groups compete to shape the social reality of organizations in ways that serve their own interests” (Mumby and Clair, 1997: 182). The indigenous claims of property ownership arguably entail a high familiarity with the ancient house’s history and culture while lacking scientific proof. Yet, this cannot justify the practice of preserving a local heritage site within the AHD that is generally concerned with national identities or nationalism. At the core, the minority culture is underrepresented due to unequal power relationships between dominant groups (e.g., executive and judicial branches) and individuals in the process of interest weighing. Heritage professionals such as archeologists, historians, and architects are “the custodians of the human past” (Smith, 2014:135), and shoulder responsibility for defining the authenticity of material heritage and then safeguarding it. They imbued the house with particular significance based on the expertise and experiences and further persuaded the government into realizing it by counseling against the demolition, i.e., the power behind discourse tends to favor experts and dismiss local efforts (Allender et al. 2006; Parkinson et al. 2016). Despite their mediating role in reconciling competing discourses, Qian would not have been awarded two opposite verdicts if the courts had not aligned with the government. Seeking common grounds for shaping heritage meaning seems to be key to balancing decision-making outcomes. The intertextuality and recontextualization of competing discourses, admittedly, may complicate the identification of heritage meaning (Wodak and Meyer, 2016).

The case under discussion demonstrates the difficulties of how the significance of historical remains is constructed and interpreted. Dissonant voices originate from varied mindsets toward the disputed issue. Conserving and restoring the ancient house is the product of negotiating the contentions of all parties before identifying the private property as cultural heritage. It is inevitable that a discourse of resistance will ensue when individuals or social groups are aware of the need for a change that would orient them to freedom from the perceived repression (Chiluwa, 2015). Along with the discourse of authority often comes the discourse of resistance, and how to achieve an effective balance between the two is a question worth pondering. A multi-stakeholder approach may be an effective means to deal with controversial heritage issues relating to diverse interest groups (Ashley et al. 2015; Katarzyna and Szymańska-Czaplak, 2022; Nobre and Sousa, 2022), as it is instrumental in supporting decision-makers to seek the best strategies for sustainable heritage development, especially in fragile contexts (Spina and Giorno, 2021; Ponton, 2022). Among others, multiple stakeholders are supposed to engage in dialog, make decisions, and implement solutions jointly concerning heritage interpretation and reuse as a cultural process (Harrison, 2013, 2015). As heritage resources are non-renewable, non-expert priorities in heritage conservation should by no means be compromised (Parkinson et al. 2016). While some may claim that polarisation is a typical feature of democratic societies, democracy is founded on shared ideologies and principles. The goal of preventing polarisation is not for achieving homogenisation, but for fostering social cohesion and a concept of “us” reflected in inter-group reliability, unity, and reciprocity.

Heritage values are “positive characteristics attributed to heritage objects and places by legislation, governing authorities, and other stakeholders” (De la Torre et al. 2005:5). This is true in the sense that experts and government officials exert social control over the sites (Wagner and Cheng, 2011). While the point of contention is whether the residence has profound significance for its linkage to the poet from the outset, the logic underlying the case is that decisions of the dominant groups are superior to the unique ancient structure of the building. Even more important is that heritage valorization needs to be understood within the current agendas, as people’s attitudes and perceptions towards heritage could change with the times. Heritage is largely shaped by the political, economic, social, cultural, and emotional meanings attached to particular events, objects, places, or social practices in various configurations (Korostelina, 2019). Privileged or dominant groups seldom share rights or interests with others, leading to non-consensus and injustice in their resolutions (Smith, 2022; Yu, 2023). The identification and appraisal of heritage is thus a value-centered practice, where political agendas orient the interpretations of heritage sites based on actual needs of dominant groups (Li, 2019). Given that cultural heritage is one of the greatest assets of a city that is irreducible and non-renewable, it is ill-advised to realize political achievement, economic construction or tourism development at the expense of collective identity and memory. Beyond this, communicative practices could also impact the transformation of the institutional order, which is locally achieved through multiple interactions of social actors in the form of conflict, negotiation and compromise (Sarangi and Roberts, 1999). But compromise might not always be achievable, given that one party typically prevails over another in such situations, where deconstructing the politics of heritage recognition and misrecognition necessitates a multifaceted analysis.

Heritage conservation and cultural rights are closely interrelated. However, China’s current laws and policies place some stakeholders at a disadvantage primarily as cultural rights are not given ample attention they deserve (Gruber, 2017). This could prevent individuals from challenging privileged groups when it comes to the infringement on their rights and interests, and also has become an increasingly pressing issue to contend with.

Heritage protection legislation, cultural rights, and egalitarianism

The four-year-long civil lawsuit against demolishing the house of No. 98, Hai’er Lane marked the success of the common people who protected historical and cultural relics via legal means, and it was regarded as one of the most influential cases in Zhejiang province that contributed to advancing the legal system and democratic progress, despite the ongoing struggle for heritage acknowledgment and recognition (Butler, 2021). The defensive war has prompted retrospection of the Hangzhou municipal government and associated departments, and further facilitated the promulgation of Measures for the Protection of Hangzhou Historical and Cultural Blocks and Historic Buildings in 2005. It explicitly states that construction units, owners or users of historic buildings should temporarily stop the demolition or construction, take protective measures, and ask administrative departments for further advice during urban regeneration. The interpretation and application of legal norms, to a large extent, hinge on prevailing discourses of the particular context and time (Cheng and Machin, 2022). It is gratifying that such practices have helped a multitude of old buildings with historical significance survive threats and damage.

Besides municipal efforts, Article 22 of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China stipulates that “The state protects sites of scenic and historical interest, valuable cultural monuments and relics and other significant items of China’s historical and cultural heritage”. It acknowledges the legal status of cultural heritage in China, which is equally evident in some national laws and regulatory standards, like the Urban and Rural Planning Law of the People’s Republic of China (2019 Amendment), Cultural Relics Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China (2017 Amendment), and Regulations on Scenic and Historic Areas (2016 Amendment). For this reason, the whole society should protect heritage resources on the grounds that it is a crucial human rights issue (Rowlands, 2004). According to the legal interpretations in the Right of Everyone to Take Part in Cultural Life issued by the United Nations Economic and Social Council,Footnote 8

Cultural rights are an integral part of human rights and, like other rights, are universal, indivisible and interdependent. The full promotion of and respect for cultural rights is essential for the maintenance of human dignity and positive social interaction between individuals and communities in a diverse and multicultural world.

Regrettably, there is not enough protection under the law for the role and rights of potentially affected residents. For instance, the Cultural Relics Protection Law places a greater emphasis on objects than on individuals and communities that maintain cultural links with them. Worse still, the scope and boundaries of the public interest as defined in legal norms are unclear and ambiguous. Cultural rights seem to be insufficiently represented in China’s laws for protecting heritage, constituting a restriction on public interest litigation. China thus lacks a comprehensive law specializing in the conservation and administration of cultural heritage in a strict sense. Under such an imperfect legal system, local officials and developers may well sacrifice heritage sites of cultural significance for local socioeconomic growth and gentrification. Considering this, endeavors are needed to legitimate the rational use of heritage for its sustainable development and give prominence to cultural rights in law, along with a standardized and systematic planning system through which heritage destruction, damage, and desecration can be dramatically mitigated.

While some stakeholders (e.g., local inhabitants) have limited ability to seek judicial review and preserve heritage sites scheduled for demolition (Gruber 2017), the case of the house at No. 98, Hai’er Lane proves to be a victory of cultural rights over economic benefits. Officials in charge of urban and rural planning may lack the required knowledge for defining heritage and manipulate heritage through the commodification of power. In this regard, the behaviors of interfering in heritage planning and management should be rigorously curbed. To achieve this, a high-quality regulatory system and a strict life-long accountability system need to be established, as legal liability constraints are a strong guarantee for protecting natural and cultural heritage resources. Yet, such provisions are not adequately stipulated in China, posing a severe threat to cultural security. Given that “law is a powerful instrument for socio-political governance” (Wu and Cheng, 2022: 108), it is critical not only to hold whoever violates the law liable but also to develop mechanisms for the accountability and prosecution of government agencies concerned. Special attention should also be given to the bearer of responsibility, destruction behaviors, and damage consequences, with the aim to lay a solid foundation for and facilitate administrative enforcement and judicial remedies.

China faces three challenges with regard to cultural heritage conservation, i.e., lack of active community participation, profit-driven decision-making processes, and centralized management (Li et al. 2020). As society becomes increasingly aware of and concerned about the direction of heritage management and conservation, involving the public in heritage protection and promotion through official guidance and financial incentives is a wise option. Public consultation and participation (Yu et al. 2022), together with proposals from heritage experts, can make the decision-making more scientific and democratic. Collaborative planning and management have proven to be a successful attempt in Australia and Hungary (Selman, 2001; Sobels et al. 2001); but most notably, recognizing the local identity is the first step towards egalitarianism. In the case of Ahmed Al-Faqi Al-Mahdi for the destruction of cultural heritage in Timbuktu, Mali, the international Criminal Court has, for the first time ever, specified the victims of crimes (i.e., the Timbuktu community, Malian people, and the global society) against cultural heritage in an international judicial decision, fully reflecting the outstanding universal value of cultural heritage to humanity and its significance in the dimension of human rights.Footnote 9 It is not possible to separate cultural heritage from the people concerned and their legal rights. In this sense, the Hai’er Lane case sheds light on the people-centered concept to preserve and develop heritage.

Conclusion

The preservation of the house at No. 98, Hai’er Lane, an inhabited heritage site, offers an excellent opportunity to explore competing discourses—a domain in which the voices of ordinary residents were almost unheard without the involvement of heritage professionals and thus shielded from the process of critical reasoning. The case is inextricably interwoven with multiple narratives of the local community, lower and higher courts, and government agencies. The discourse of cultural heritage here relates to the power “imposed on local inhabitants by the elite group” (Yan, 2015:78) under the influence of pragmatism. The inequality of power distribution has caused conflicting interests concerning the demolition, showing that authorities have the exclusive power to manipulate the practice of defining, protecting, and managing heritage. Through the case study, we argue there is still some room for individuals to challenge dominant narratives set by the government (Zhu, 2018). However, numerous costs are inherent in the legal process for any litigant, including legal expenses, time invested, and psychological strain. Consequently, a significant portion of individuals may be deterred from pursuing this route due to these factors, highlighting the challenges and obstacles associated with persistent prosecution. Based on our analysis, it is advisable to mediate the interests of multiple actors with a holistic view by using a multi-stakeholder approach, given heritage discourse as social interaction (Van Dijk, 1997).

Another reflection is that the case should be understood “within the dominant discourses of their time” (Cheng et al. 2022:11). Cultural heritage, if taken as a social sign, particularly for its identification and conservation, may be subject to different constructions by sign users as society progresses. In other words, the interpretation of heritage values is fluid and dynamic. When defining them, the authorities and policy-makers can ill-afford to ignore the involvement of whoever created, owns, safeguards, and promotes heritage of paramount importance in the decision-making process (Gruber, 2017), including key stakeholders like owners/users of heritage, heritage professionals, government officials, developers, or anyone who has physical or spiritual access to it. The safeguarding of cultural heritage is inherently centered on people, both present and future generations. As the global community keeps heightening its focus on the social attributes of cultural heritage and the public benefit in its use, cultural relics and monuments are poised to better cater to humanity, fostering a progression from mere comprehension of their worth to an active participation in cultural inheritance. This is in large part a result of the shift from an object-centered to a people-centered perspective in heritage preservation and promotion. The successful model for cultural heritage conservation used worldwide tend to adopt “an inclusive and integrated approach” through bottom-up initiatives (Li et al. 2020:7), which heritage practitioners need to reflect on thoroughly.

Since heritage protection law in China places a greater emphasis on objects than on individuals and communities, we also propose to cope with intricate tensions between the conservation, development, and utilization of cultural heritage by promulgating more systematic and explicit laws and regulations that better reflect the heteroglossia of stakeholders, which is conducive to “equitable dialogues and social inclusion” (Waterton et al. 2006: 339). Future research can take this a further step by probing into how similar contradictions in other contexts are addressed.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

03 February 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04449-z

Notes

It is the first case in China that the common people successfully protected historical and cultural relics through legal means and won a lawsuit for the protection of ancient buildings.

The Historic Cultural City Conservation Plan was enacted, primarily due to this case.

The civil judgement of the Xiacheng District People’s Court was later abrogated by the higher court, i.e., Hangzhou Municipal Intermediate People’s Court.

See the Statement of Attorney by the lawyer representing Xiyao Qian from Zhejiang Huilun Law Firm.

The case is introduced in a chronological order according to the official news agency, Zhejiang Online News Website.

The left photo was taken in front of the house at No. 98, Hai’er Lane. Beneath the house number is a stone plaque on which a brief description of the site was given. The photo on the right was taken in the courtyard where the octagonal well was once used for water supply by inhabitants.

The names of Lu You’s Memorial Hall and Xiacheng Cultural and Historical Museum were inscribed on the left stele, while a snapshot of the Lu You’s Memorial Hall on the original site was given on the right.

Art. 15, Para. 1 (a), of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights by the United Nations Economic and Social Council in 2009.

Mr Al-Mahdi was convicted as a co-perpetrator under articles 8 (2) (e) (iv) and 25 (3) (a) of the Statute for intentionally attacking ten protected objects in Timbuktu, Mali, between around 30 June 2012 and 11 July 2012, and sentenced to 9 years of imprisonment, according to the summary of the judgement on the appeal of the LRV in the case of Ahmad Al Faqi Al (reparations), delivered by Howard Morrison, the presiding judge in this appeal.

References

Allender S, Colquhoun D, Kelly P (2006) Competing discourses of workplace health. Health 10(1):75–93

Amar JHN, Armitage L (2019) Community heritage discourse (CHD): A multidisciplinary perspective in understanding built heritage conservation. Pac. Rim Prop. Res J. 25(3):229–244

Ashley KS, Osmani M, Emmitt S, Mallinson M, Mallinson H (2015) Assessing stakeholders’ perspectives towards the conservation of the built heritage of Suakin, Sudan. Int J. Herit. Stud. 21(7):674–697

Avrami E, Mason R (2019) Mapping the issue of values. In: Avrami E, Macdonald S, Mason R, Myers D (eds) Values in heritage management: Emerging approaches and research directions. Getty Publications, Los Angeles, pp 9–34

Blake J (2008) On defining the cultural heritage. Int Comp. Law Q 49(1):61–85

Bloor M, Bloor T (2013) The practice of Critical Discourse Analysis: An introduction. Routledge, London

Bouvier G, Wu Z (2021) A sociosemiotic interpretation of cultural heritage in UNESCO legal instruments: A corpus-based study. Int J. Leg. Discours 6(2):229–250

Butler J (2021) Recognition and the bound: A response to Axel Honneth. In: Ikäheimo H, Lepold K, Stahl T (eds) Recognition and ambivalence. Columbia University Press, New York

Cameron F, Kenderdine S (eds) (2007) Theorizing digital cultural heritage: A critical discourse. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Carman J (2002) Archaeology and heritage: An introduction. Continuum, London and New York

Cheng L, Cheng W (2012) Legal interpretation: Meaning as social construction. Semiotica 191:427–448

Cheng L, Wu Z (2021) Review of the discourse of security: Language, illiberalism and governmentality. Crit. Discours Stud. 18(3):406–409

Cheng L, Machin D (2022) The law and critical discourse studies. Crit. Discours Stud. 20(3):243–255

Cheng L, Zhu X, Machin D (2022) The depoliticization of law in the news: BBC reporting on US use of extraterritorial or ‘long-arm’ law against China. Crit. Discours Stud. 20(3):306–319

Cheng L, Sin KK (2007) Contrastive analysis of Chinese and American courtroom judgments. In: Kredens K, Gozdz-Roszkowski S (eds) Language and the law: International outlooks. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main, pp 325–356

Chiluwa I (2015) Radicalist discourse: A study of the stances of Nigeria’s Boko Haram and Somalia’s Al Shabaab on Twitter. J. Multicult. Discours 10(2):214–235

Christie JJ (2021) Earth politics and intangible heritage: Three case studies in the Americas. University Press of Florida, Gainesville

De la Torre M, MacLean MGH, Mason R, Myers D (2005) Heritage values in site management: Four case studies. Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles

De la Torre M (ed) (2002) Assessing the values of cultural heritage. The Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles

Dundon J (2024) Language ideologies and speaker categorization: a case study from the U.S. legal system. Int J. Leg. Discours 9(1):169–195

Fairclough N (2003) Analyzing discourse and text: Textual analysis for social research. Routledge, London

Gomez-Heras M, McCabe S (2015) Weathering of stone-built heritage: A lens through which to read the Anthropocene. Anthropocene 11:1–13

Gruber S (2017) The tension between rights and cultural heritage protection in China. In: Durbach A, Lixinski L (eds) Heritage, culture and rights: Challenging legal discourses. Bloomsbury, London, pp149–163

Habibi T, Ruban DA (2017) Outstanding diversity of heritage features in large geological bodies: The gachsaran formation in southwest Iran. J. Afa Earth Sci. 133:1–6

Hall S (2011) The work of representation. In: Hall S, Evans J, Nixon, S (eds) Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices. Sage, London, pp 13–74

Harrison R (2013) Heritage: Critical approaches. Routledge, New York

Harrison R (2015) Beyond “natural” and “cultural” heritage: Toward an ontological politics of heritage in the age of anthropocene. Herit. Soc. 8(1):24–42

Harvey DC (2001) Heritage pasts and heritage presents: Temporality, meaning and the scope of heritage studies. Int J. Herit. Stud. 7(4):319–338

Havinga L, Colenbrander B, Schellen K (2020) Heritage significance and the identification of attributes to preserve in a sustainable refurbishment. J. Cult. Herit. 43:282–293

Jessup B, Rubenstein K (2012) Introduction: Using discourse theory to untangle public and international environmental law. In: Jessup B, Rubenstein K (eds) Environmental discourses in public and international law. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 1–26

Ju P (ed) (2018) Retaining nostalgia: Oral narratives of Ruan Yisan’s road to protect the city. East China Normal University Press, Shanghai

Katarzyna M, Szymańska-Czaplak E (2022) “Nature needs you”: discursive constructions of legitimacy and identification in environmental charity appeals. Text. Talk. 42(4):499–523

Korostelina KV (2019) Understanding values of cultural heritage within the framework of social identity conflicts. In: Avrami E, Macdonald S, Mason R, Myers D (eds) Values in heritage management: Emerging approaches and research directions. Getty Publications, Los Angeles, pp 83–96

Li J, Krishnamurthy S, Rodersa AP, van Wesemaela P (2020) Community participation in cultural heritage management: A systematic literature review comparing Chinese and international practices. Cities. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.102476

Li K (2019) The contemporary values behind Chinese heritage. In: Avrami E, Macdonald S, Mason R, Myers D (eds) Values in heritage management: Emerging approaches and research directions. Getty Publications, Los Angeles, pp 97–109

Lipe WD (1984) Value and meaning in cultural resources. In: Cleere H (ed) Approaches to the archaeological heritage: A comparative study of world cultural resource management systems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 1–11

Logan WS (2007) Closing pandora’s box: Human rights conundrums in cultural heritage. In: Silverman H & Ruggles DF (eds) Cultural heritage and human rights. Springer, New York, pp 33–52

Lowenthal D (1998) The heritage crusade and the spoils of history. Cambridge University Press, New York

Ma, QK, Cheng, L 2019. New developments in international heritage studies: Shifting from a material centric approach to a people-oriented approach. S Cult (2):16–22

Maags C (2018) Creating a race to the top: Hierarchies and competition within the Chinese ICH transmitters system. In: Maags C, Svensson M (eds) Chinese heritage in the making: Experiences, negotiations and contestations. Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, pp 121–144

McGrath SK, Whitty SJ (2017) Stakeholder defined. Int J. Man. Proj. Bus. 10(4):21–748

Mubaideen S, Al Kurdi N (2017) Heritage conservation and urban development: A supporting management model for the effective incorporation of archaeological sites in the planning process. J. Cult. Herit. 28:117–128

Mumby DK, Clair RP (1997) Organisational discourse. In: van Dijk TA (ed) Discourse as Social Interaction. SAGE Publications, London, pp 181–205

Munawar NA, Symonds J (2022) Post-Conflict reconstruction, forced migration & community engagement: The case of Aleppo, Syria. Int J. Herit. Stud. 28(9):1017–1035

Nobre H, Sousa A (2022) Cultural heritage and nation branding-multi-stakeholder perspectives from Portugal. J. Tour. Cult. Change 20(5):699–717

Parkinson A, Scott M, Redmond D (2016) Competing discourses of built heritage: lay values in Irish conservation planning. Int J. Herit. Stud. 22(3):261–273

Ponton DM (2022) Narratives of industrial damage and natural recovery: An ecolinguistic perspective. Text. Talk. 42(4):475–497

Rowlands M (2004) Cultural rights and wrongs: Uses of the concept of property. In: Humphrey C, Verdery K (eds) Property in question: Value transformation in the global economy. Routledge, London, pp 1–20 (Chapter 9)

Samuels KL (2008) Value and significance in archaeology. Archaeol. Dialog 15(1):71–97

Sarangi S, Slembrouck S (1996) Language, bureaucracy and social control. Routledge, London

Sarangi S, Roberts C (eds) (1999) Talk, work and institutional order: Discourse in medical, mediation, and management settings. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin

Selman P (2001) Social capital, sustainability and environmental planning. Plan Theory Pr. 2(1):13–30

Si C, Liu Y (2022) Exploring the discourse of enterprise cyber governance in the covid-19 era: A sociosemiotic perspective. Int J. Leg. Discours 7(1):53–82

Smith L (2006) The uses of heritage. Routledge, New York

Smith L (2014) Intangible heritage: A challenge to the authorised heritage discourse? Rev. d’ Etnol. de. Catalunya 40:133–142

Smith L (2022) Heritage, the power of the past, and the politics of (mis)recognition. J. Theor. Soc. Behav. 52(4):623–642

Smith L (2012) Discourses of heritage: implications for archaeological community practice. Nuevo Mundo Mundos Nuevos. https://doi.org/10.4000/nuevomundo.64148

Sobels J, Curtis A, Lockie S (2001) The role of Landcare group networks in rural Australia: exploring the contribution of social capital. J. Rural Stud. 17(3):265–276

Spina LD, Giorno C (2021) Cultural landscapes: A multi-stakeholder methodological approach to support widespread and shared tourism development strategies. Sustainability 13:7175

Svensson M, Maags C (2018) Mapping the Chinese heritage regime: Ruptures, governmentality, and agency. In: Maags, C, Svensson M (eds) Chinese heritage in the making: Experiences, negotiations and contestations. Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, pp 11–38

Tunbridge JE, Ashworth GJ (1996) Dissonant heritage: The management of the past as a resource in conflict. John Wiley, Chichester

Tweed C, Sutherland M (2007) Built cultural heritage and sustainable urban development. Landsc. Urban Plan 83(1):62–69

Van Dijk TA (2014) Discourse and knowledge: A Sociocognitive approach. CUP, Cambridge

Van Dijk TA (ed) (1997) Discourse as social interaction. Sage Publications Ltd, London

Verdini G, Frassoldati F, Nolf C (2017) Reframing China’s heritage conservation discourse. Learning by testing civic engagement tools in a historic rural village. Int J. Herit. Stud. 23(4):317–334

Wagner A, Cheng L (2011) Exploring courtroom discourse: The language of power and control. Ashgate, London

Wagner A, Matulewska A, Cheng L (2021) Protection, regulation and identity of cultural heritage: From sign-meaning to cultural mediation. Int J. Semiot. Law 34(3):601–609

Waterton E, Smith L, Campbell G (2006) The utility of discourse analysis to heritage studies: The Burra Charter and Social Inclusion. Int J. Herit. Stud. 12(4):339–355

Waterton E, Watson S (eds) (2010) Culture, heritage and representations: Perspectives on visuality and the past. Ashgate Publishers, Aldershot

Wilson J, Stapleton K (2007) The discourse of resistance: Social change and policing in Northern Ireland. Lang. Soc. 36(3):393–425

Wodak R, Meyer M (2016) Critical discourse analysis: History, agenda, theory and methodology. In: Wodak R, Meyer M (eds) Methods of critical discourse analysis. SAGE Publications Ltd, London, pp 1–33

Wu Z (2023) Review of hegemony, discourse, and political strategy: Towards a post-Marxist understanding of contestation and politicization. Discourse Stud. 25(6):846–848

Wu Z, Cheng L (2022) Exploring metaphorical representations of law and order in China’s government work reports: A corpus-based diachronic analysis of legal metaphors. Crit. Arts 36(5-6):96–112

Wu Z, Hou S (2015) Heritage and discourse. In: Waterton E, Watson S (eds) The palgrave companion to contemporary heritage research. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, pp 37–51

Yan H (2015) World Heritage as discourse: knowledge, discipline and dissonance in Fujian Tulou sites. Int J. Herit. Stud. 21(1):65–80

Yu J, Leung M, Jiang X (2022) Impact of critical factors within decision making process of public engagement and public consultation for construction projects – case studies. Int J. Constr. Manag 22(12):2290–2299

Yu W (2023) Negotiation of justice: the discursive construction of attitudinal positioning in bilingual legal judgments of HKSAR v KWAN WAN KI. Int J. Leg. Discours 8(2):299–333

Zhao J, Wu J, Yang Y (2021) A sociosemiotic exploration of medical legislation reform in China (1990–2021). Int J. Leg. Discours 6(2):203–228

Zhu Y (2018) Uses of the past: negotiating heritage in Xi’an. Int J. Herit. Stud. 24(2):181–192

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by the National Social Science Fund of China under grant number 24BYY151, the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Project of China’s Ministry of Education under grant number 23YJCZH242, Zhejiang Provincial Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Project under grant number 23BMHZ055YB, Zhejiang Association of Foreign Languages & Literatures under grant number ZWYB2019020, Major Humanities and Social Sciences Research Projects in Zhejiang higher education institutions under grant number 2024QN069 and Hangzhou Collaborative Innovation Institute of Language Services, Hangzhou City University, China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the research conception and design. ZW organized the collection of the data and drafted the work. JL performed the data analysis and made many constructive comments on the earlier versions. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies requiring ethical approval.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by either of the two authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Z., Li, J. Competing stakeholder discourses in constructing cultural heritage: The legal case of the house at No. 98 Hai’er Lane, China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1758 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04273-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04273-x