Abstract

Gross ecosystem product (GEP) refers to the direct measurement of a region’s ecosystem product supply capabilities and the basis for value realisation. China has made clear arrangements for establishing GEP assessment regulations, with 36 districts and counties currently conducting GEP assessment, of which 24 districts and counties have executed dual assessments of regional gross domestic product (GDP) and GEP. To explore the influence of GEP assessment on the common prosperity of urban and rural regions, this study conducts a quasi-natural experiment using the staggered difference-in-differences model to examine data from 1946 districts and counties from 2012 to 2022. The results reveal that GEP assessment can significantly reduce the urban-rural income gap and improve rural residents’ income, thereby realising common prosperity. Further analysis indicates that GEP assessment promotes faster income growth for rural residents and a narrowing of the income gap between urban and rural residents through enhanced government attention, fiscal support, green finance, and agricultural development. The impact of GEP assessment on common prosperity is obviously heterogeneous. The ability of GEP assessment to promote common prosperity is stronger in key ecological function areas, districts and counties with strong fiscal capacity and high public environmental concern. This study confirms the positive role of GEP assessment in increasing rural residents’ income and advancing common prosperity. The results also provide a decision-making reference for the expedient implementation of GEP assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Common prosperity is the essential requirement of socialism with Chinese characteristics and the main goal of economic and social development during the 14th Five-Year Plan period. The formation of a coordinated development pattern between urban and rural regions is an important measure of common prosperity (Dong et al. 2023; Liu et al. 2023b; Sha et al. 2024). This requires reasonably reducing the gap between the living standards of urban and rural residents. In recent years, China’s overall, urban-rural, and inter-regional income gaps have been narrowing, but the challenge of unbalanced and insufficient development remains. Furthermore, from 2008 to 2022, China’s Gini index dropped from 0.491 to 0.467, but far exceeds the global warning line of 0.4 (Yuan et al. 2020). Urban and rural residents’ income ratio dropped from 3.11:1 to 2.45:1, whereas the international average is only 1.5:1, and there is still a certain gap between the two. Promoting increased income for rural residents is key to achieving common prosperity. Since the Eighteenth National Congress, China has gradually incorporated eco-efficiency into the assessment system. The 13th Five-Year Plan promulgated in 2016 fully incorporated GEP accounting into the national economic work plan. The technical specifications for GEP assessment were formulated in 2022. Gross ecosystem product (GEP) is an intuitive measure of ecosystem product supply (Hao et al. 2022; Shen et al. 2024; Zheng et al. 2023b). GEP assessment pushes the flow of economic wealth from ecological resource use to supply. It realises the wealth transfer between urban and rural regions. Carrying out GEP assessment is of strategic significance for shaping a new pattern of coordinated development in urban and rural regions (Liu et al. 2024b). It has become an effective path for promoting common prosperity (Yin and Zhao 2024). And does the GEP assessment promote common prosperity? What is its action mechanism? Given this, this paper tries to verify the impact of GEP assessment on common prosperity using data from 1946 districts and counties in China.

The only GDP assessment methods have structural defects, do not cover ecosystem output and benefits (Costanza et al. 2014). China has been actively exploring GEP assessment and GEP + GDP double assessment (Shaker 2018; Wang et al. 2024; Yang et al. 2023). Incorporating GEP into local government assessment systems can promote the coordination and unity of economic and social development alongside ecological and environmental protection (Li et al. 2024c; Wang et al. 2019). GEP has attracted extensive attention from the academic community (Hao et al. 2022). A large number of scholars have quantified GEP to assess the value of natural environment’s contribution to economic activity (Jiang et al. 2021; Li et al. 2024a; Li et al. 2024c; Ouyang et al. 2020; Shen et al. 2024; Zou et al. 2020a). From the perspective of coordinated regional development, scholars have argued that GEP assessment can promote ecological protection compensation and ecological benefit sharing, which stimulates sustainable development (Zhou et al. 2019). From this perspective, some scholars have explored the possibility of using GEP as a performance assessment method for regional ecological protection effectiveness (Zheng et al. 2023a). Some of the literature has investigated various approaches for efficient GEP assessment implementation, the most significant of which is establishing GEP assessment and accounting standards (Li et al. 2024c). GEP has been widely investigated and applied at different scales such as countries, provinces, cities, counties, and river basins (Frélichová et al. 2014; Li et al. 2023b; Li et al. 2024a; Wang et al. 2017; Zou et al. 2020b).

Common prosperity encompasses two dimensions, affluence and sharing. As early as the 1950s, China already proposed the concept of common prosperity, which originated from an article published in People’s Daily in 1953. Scholars in various countries have generally been concerned about the urban-rural income gap and income inequality (Chanieabate et al. 2023; Ermagun et al. 2023; Meloni et al. 2024), and believed that intellectual property rights and technological innovation are the main causes of income inequality (Saito 2017; Uche et al. 2024; Zhang et al. 2018), emphasising the use of taxation, social security, and transfer payments to alleviate urban-rural gap. Several studies have confirmed that urbanization (Chen et al. 2023; Su et al. 2015; Yu et al. 2024b), digital economy (Zhao and Jiao 2024; Zhou and Guo 2024), agricultural development and subsidies (Gao et al. 2014; Sha et al. 2024), financial development (Su et al. 2019), and infrastructure development (Huang et al. 2020) are the important factors affecting common prosperity. In recent years, more and more scholars have focused on the impact of environmental policies on common prosperity, mostly on low-carbon energy transition (Liu et al. 2023c), ESG ratings (Ma and Ma 2024), and green bonds (Liu et al. 2024c).

Some scholars have begun to focus their research perspectives on GEP and common prosperity. Some scholars have believed that focusing on GEP is conducive to increasing ecosystem product supply, thereby improving people’s living standards and narrowing the income gap. GEP assessment can improve ecological compensation mechanism, and promote the transformation of GEP from potential, nominal ecological value to actual, real economic well-being (Joshi et al. 2023; Wang et al. 2022b). Ecosystem products make a greater contribution to economic development and improve residents’ living standards (Yu et al. 2023). Some scholars have also pointed out that the increase in ecosystem product supply may incur the risk of depriving rural residents of their right to development (Cao and Zhang 2018), which is not conducive to the improvement of income and living standards in rural regions.

Relevant studies have demonstrated the positive influence of GEP on advancing common prosperity from different perspectives, presenting proposed paths and countermeasures for GEP to promote common prosperity. However, room still remains for expanding on previous research. Existing research has mostly focused on quantitative GEP, and the research on GEP assessment is mainly based on the interpretation of national deployment and analysis of great significance. Local practices have often been carried out in the form of typical cases (Li et al. 2023a; Li et al. 2024a; Yin and Zhao 2024; Zou et al. 2020b), lacking analysis of the overall circumstances of promotion at the national level. Furthermore, previous research concerning the influences of GEP on common prosperity has primarily been based on qualitative and normative analyses. However, there is a lack of empirical testing and quantitative evidence to support the impact of GEP assessment on common prosperity.

The contributions of this study are reflected in three aspects. First, the study quantifies the current status of GEP assessment at the county level in China. This study identifies and examines the practice of GEP assessment and GDP assessment cancellations in 2843 districts and counties in China as of March 2024 using web crawlers, keyword retrieval, and other technical approaches. This study reveals local practices and the promotional status of GEP assessment in China. Second, this study conducts empirical tests of the influence of GEP assessment on common prosperity. Taking districts and counties as samples, our dynamic panel analysis of GEP assessment in narrowing the income gap between urban and rural residents, and improving residents’ income. This introduces a quantitative supplement of previous qualitative analyses of the effect of GEP assessment on promoting common prosperity. Third, this study explores the mechanism of GEP assessment in promoting common prosperity. Beginning with the key links that are directly related to common prosperity such as government attention, fiscal transfer payments, green financial support, and the promotion of agriculture development, this study explores the path of GEP assessment in promoting common prosperity and tests the conclusions of current normative analysis. This study explores the role and mechanism of GEP assessment in promoting common prosperity. The results provide a decision-making reference for standardising the application of GEP accounting results and optimising government performance assessment methods.

Policy background and research hypothesis

Policy background

National deployment of GEP assessment

China has established a series of decisions and arrangements to downplay GDP assessment approaches and focus on citizens’ livelihood and well-being. The 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China report clearly proposed that resource consumption, environmental damage, and ecological benefits must be integrated into economic and social development evaluation systems. In December 2013, the Notice on Improving the Performance Assessment of Local Party and Government Leadership Teams and Leading Cadres clearly requires that the GDP and economic growth should not be used as the primary indicators for assessing performance. Livelihood improvement, cultural construction, and ecological civilisation development should be integrated as essential assessment and evaluation considerations.

Currently, GEP assessment in China is based on value accounting, referencing government performance assessment as a starting point, which is supplemented by the supervision system of the National People’s Congress for state-owned natural resource asset managers and natural resource asset exit audits (Liu et al. 2024b). In 2021, China issued the Opinions on Establishing and Improving the Mechanism for Realising the Value of Ecosystem Products (referred to as Opinions), which used GEP assessment for government decision-making, performance assessment, and evaluation. Opinions also identified GEP assessment as the main direction for promoting the application of ecosystem product value accounting results. The Opinions on Establishing and Improving the Evaluation Indicator System of Natural Resource Asset Audit for Leading Cadres were promulgated in 2022, taking GEP physical quantity and value accounting results as a basis for supervising and evaluating leading cadres. Under the trajectory of national transformation, GEP assumes a significant influence on ecological civilisation and government performance assessment. The valuation of the ecosystem is being incorporated into evaluations of national economic and social development (Zhang et al. 2022).

Local practice of GEP assessment

Under strategic national deployment, various regions have conducted GEP assessment. Currently, 21 provinces (autonomous regions and municipalities) in China have made GEP accounting and statistical system as a primary task, and incorporated GEP into comprehensive performance evaluations. When implementing GEP assessment work, provinces have followed the principle of focusing on assessing ecosystem product supply capacity indicators in key ecological functional areas and using a dual assessment system of expediently assessing economic development and ecosystem product value in other main functional areas (Table 1).

Currently, some districts and counties have taken the lead in implementing GEP assessment under the guidance of Opinions and local implementation plans, and explored the establishment of “double accounting, double assessment, and double improvement” mechanisms from combining GEP and GDP. As of March 2024, among the 2843 district- and county-level administrative regions announced by the Ministry of Civil Affairs in 2022Footnote 1, 530 districts and counties have cancelled GDP assessment. At the same time, 36 districts and counties have clearly established GEP assessment to make up for the limitations of only GDP assessment in terms of ecological environment (Table 2).

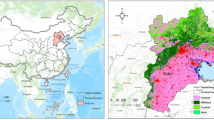

While abolishing GDP assessment, 12 districts and counties took the lead in promoting GEP accounting and conducting GEP assessment. These districts and counties are mainly located in southern China, among which nine are located in Lishui, Zhejiang Province (Fig. 1). The areas that only conduct GEP assessment are mainly restricted development areas. Except for Liandu District in Lishui, which is a key development area, the other 11 districts and counties are restricted development areas, among which main agricultural production areas account for 4/11 and key ecological functional areas account for 7/11. Key ecological functional areas undertake land space development to enhance the production capacity of ecosystem products. Canceling GDP assessment and implementing GEP assessment aligns with the positioning of these main functional area types.

Twenty-four districts and counties have adopted GDP + GEP double assessment. Among them, Pu’er (1 district and 9 counties) and Shangluo (1 district and 6 counties) have fully implemented a double assessment system throughout their territories. The double assessment districts and counties are also predominantly restricted development areas. Among the 24 districts and counties, 17 are restricted development areas, of which main agricultural production areas account for 6/17, and key ecological function areas account for 11/17. In addition, five key development areas are located in Wuhan, Qiannan Prefecture, Pu’er, Shangluo, and three optimised development areas are in Shenzhen. Optimised and key development areas are urbanised areas with relatively developed economies and dense populations. They also face more prominent resource and environmental problems. The GDP + GEP double assessment reflects a strong awareness of ecological protection and high-quality development in these areas.

Research hypothesis

Narrowing the urban-rural gap is a key foundation and most prominent task for promoting common prosperity, in addition to being a crucial step in eradicating poverty and promoting development (Liu et al. 2017). Underdevelopment in rural regions is the main reason for China’s urban-rural gap (Yao and Jiang 2021), and giving priority to raising rural residents’ income level is the foremost condition for realising common prosperity. The rural regions are the main providers of ecosystem products (Liu et al. 2024b). GEP assessment implies that the local region has a strong ability to supply ecosystem products, a feature that will motivate the government to provide more ecological welfare, which in turn is an effective complement to social and economic welfare (Cong et al. 2023; Wang and Zhang 2022), and improves rural residents’ living standards. The strong supply of ecosystem products leads to the concentration of social capital in rural regions. Financial transfers and ecological compensation promote the economic development of rural regions. Furthermore, based on their rich ecosystem products, rural regions have formed new modes of ecological industries, such as forest economy and ecotourism, which provide rural residents with more income channels and sources. This further stimulates the potential for regional economic development (Gunter et al. 2018; Stem et al. 2003), and raises rural residents’ income level.

The suppliers of ecosystem products are usually rural residents with superior ecological environmental resources and high-quality ecosystem products; however, their income levels are relatively low. The demanders are usually urban residents who enjoy a higher standard of living and have a higher demand for a positive ecological environment (An et al. 2018). Therefore, the government-led GEP assessment connects rural and urban residents and promotes the transfer of social wealth from urban to rural regions. It is not only a new way to raise rural residents’ income level, but also a new channel to narrow the income gap between urban and rural residents, which embodies the connotation of two dimensions of “affluence” and “sharing” of common prosperity. The advantages of ecological environment and natural resources provide underdeveloped regions with a path to advance regional economic development and narrow the income gaps between regions, which accelerates common prosperity (Yin and Zhao 2024).

Based on the above analyses, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1: GEP assessment can increase rural residents’ income, narrow the urban-rural gap, and contribute to achieving common prosperity.

GEP assessment is promoted by the government based on the GEP accounting. It promotes the sustainable development of local economy (Fan et al. 2024), and helps realise common prosperity. Taking GEP assessment as an important indicator of performance evaluation means that it pays more attention to local environmental and ecological issues. The government shifts from focusing only on GDP growth to valuing local ecosystem products (Ouyang et al. 2020). Under the assessment orientation of targeting the economy and the environment, the concern for the realisation of ecosystem product value has significantly increased. The increase in government attention will send a signal to the outside world to value ecosystem products, guiding the participation of multiple social actors. Therefore, the inflow of more social capital into rural regions rich in ecological resources is conducive to enhancing rural residents’ income. At the same time, to realise the high value of ecosystem products, the government tries to establish a cross-regional ecological collaboration mechanism to make up for the loss in rural economic growth through an ecological compensation mechanism (Qin et al. 2022), and narrow the gap between urban and rural regions. The government also tries to optimise the allocation of ecological resources and share the benefits of each region to enhance the welfare level of society and promote a common prosperity goal.

GEP assessment can motivate local governments to promote the transformation of ecological resources into economic value. GEP assessment prompts the reallocation of financial resources and funds, prioritising the investment of funds in ecological protection and environmental restoration projects. Eco-friendly projects can obtain more financial support (Chuc Anh et al. 2020), and the government has set up a special fund to strengthen financial help to rural regions. GEP assessment focuses on the improvement of ecological compensation mechanism, and financial transfers are made to the regions that bear the heavy burden of ecological protection (Cao et al. 2022). These compensation funds not only alleviate economic pressure brought by ecological protection but also make up for ecological protection costs (Liu et al. 2024a; Zhang et al. 2024), provide a new source of income for local residents. The government provides financial assistance to regions with high ecological performance and increases the supply of ecosystem products through green tax incentives and tax exemptions for environmentally friendly projects. Residents receive certain ecological subsidies to compensate for the opportunity cost of ecological protection and restoration, narrowing the economic gap between urban and rural regions and promoting common prosperity.

Most of China’s underdeveloped remote mountainous regions, forested regions, and river headwaters regions are rich in ecosystem products. Resource and economic development are subject to more restrictions in terms of funding. GEP assessment encourages banks and financial institutions to set up ecological projects, develop green financial products, and invest more funds in ecological and environmentally friendly industries (Yuan et al. 2021). So that ecological resource assets can be integrated into social funds through financial means. GEP assessment attaches importance to the sustainable development of ecosystems, which requires all subjects to promote marketisation of ecosystem products. Pricing of ecosystem products is improved through carbon market trading and water rights trading (Guan et al. 2021; Ji et al. 2018), attracting more and more subjects to participate in ecosystem product investment. The inclination of green financial resources is conducive to increasing financing channels, lowing financing costs and difficulty of ecological projects (Zhang 2023). This means that ecosystem product-rich regions gather more ecological capital and projects, providing more income sources for residents, thus increasing rural residents’ income and realising common prosperity.

High-quality eco-agriculture demands a favorable ecological environment, requiring the government to pay attention to ecological environment quality to promote industrial structure upgrading. Promoting GEP assessment increases the strength of environmental regulation, strictly controls the entry of high-pollution and high-emission enterprises that negatively impact the environment (Chen and Yao 2024). To improve GEP performance, the government adopts measures to stimulate eco-agriculture development. On this basis, local agriculture is adjusted toward greening and ecology, forming a complete agricultural development industry chain and further enhancing green competitiveness. GEP assessment can also promote the optimisation and upgrading of regional agriculture through industrial ecologicalisation and ecological industrialisationFootnote 2, creating more high-quality employment and opportunities for local rural residents to improve their income levels (Hu et al. 2024), thus stimulating local economic development (Civeira et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2022b). Empowering the ecological and green industry through the industry agglomeration effect can stimulate local agriculture development (Zhao et al. 2020). This creates more green jobs, promotes regional economic growth, improves people’s living standards, and realises common prosperity.

Based on this, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

H2: GEP assessment affects common prosperity mainly through government attention, fiscal support, green finance, and agricultural development.

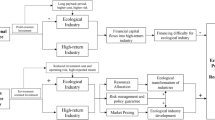

The research framework of this paper can be summarised in Fig. 2.

Research design

From the perspective of economic development, common prosperity has dual constraints of the commons and prosperity (Dong et al. 2023; Liu et al. 2023c; Wang et al. 2022c). Narrowing the development gap, and raising the incomes of residents is a realistic requirement for promoting common prosperity (Chen et al. 2023). This study examines the impact of GEP assessment on income levels and the income gap between urban and rural residents, and further explores the realistic mechanism and heterogeneous impact of GEP assessment on common prosperity.

Model construction

This study identifies 36 districts and counties in China that have conducted GEP assessment, which began implementing GEP assessment in batches covering 2014, 2018, 2020, 2021, and 2023. The staggered DID model is chosen to verify the impact of GEP assessment on common prosperity and control for county and year fixed effects. Therefore, the staggered DID model is constructed as follows:

where the explanatory variable \({Y}_{it}\) denotes the level of common prosperity, \(trea{t}_{i}\) denotes GEP assessment in region \(i\), \(pos{t}_{it}\) is a treatment period dummy variable that varies by region, \(contro{l}_{it}\) represents control variables, \({\lambda }_{t}\) and \({\mu }_{i}\) are time and region fixed effects, respectively, and \({\varepsilon }_{it}\) is random disturbance term.

Variable selection and data sources

Explained variable: common prosperity (Y). This study investigates the role and mechanism of GEP assessment in promoting common prosperity, with common prosperity saving as our explained variable. Referencing Xu and Li (2023), this study divides common prosperity into income gap reduction and income level enhancement dimensions. Specifically, this study uses the ratio of urban and rural residents’ disposable income (gap) to quantify the income gap. The logarithm of disposable income for urban residents (lncincome) and the logarithm of disposable income for rural residents (lnrincome) are used to measure income levels. The above data come from the China County Statistical Yearbook and China Regional Economic Statistical Yearbook. This paper manually compiled the statistical yearbooks of each prefecture-level city to make up for the missing data, deleted the regions with missing variables for more than 4 years or more, and performed linear interpolation. The same as below.

Core explanatory variable: GEP assessment (treat × post). The core explanatory variable in this study is policy dummy variables. treat is a region dummy variable, which takes the value 1 if a district or county conducts GEP assessment during the sample period, and 0 otherwise. post is a time dummy variable that takes the value of 1 in the current year and thereafter if a district or county conducts GEP assessment during the sample period, and conversely 0. The above data is retrieved manually by authors. The government websites of each provincial government and prefecture-level city in China are searched using GEP assessment as a keyword to get the names and years of districts and counties where GEP assessment was conducted.

Mediating variables: government attention (gov_att), fiscal support (gov_fis), green finance (gfin), and agricultural development (inds). gov_att is expressed by the degree of local government’s attention to ecosystem product value realisation, which is measured by the percentage of keyword frequency of ecosystem product value realisationFootnote 3 (Xu et al. 2023; Yu et al. 2024a). gov_fis is expressed using the proportion of fiscal general public budget expenditure to GDP, and inds is expressed using per capita agricultural output value. The data of these two variables are from the China County Statistical Yearbook and China Regional Economic Statistical Yearbook. gfin is expressed using green finance indexFootnote 4 (Jiakui et al. 2023; Lee and Lee 2022), the data were obtained from the China Urban Statistical Yearbook, China Science and Technology Statistical Yearbook, China Energy Statistical Yearbook, China Financial Yearbook, China Agricultural Statistical Yearbook, China Industrial Statistical Yearbook, and China Tertiary Industry Statistical Yearbook.

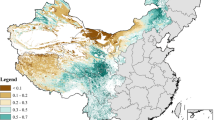

Control variables: Economic, social, and natural factors may also affect common prosperity. Therefore, it is also necessary to control for other factors’ interference when examining the impact of GEP assessment on common prosperity. In terms of economic and social factors, this study references to Dong et al. (2020), Xuan et al. (2020), Wang et al. (2022a), Jha et al. (2019), Yang and Liu (2018), using regional economy level (lnpgdp), population size (lnpop), labour force quality (lnlq), industrial structure (lnsec), technological level (lninno), urbanisation level (lnurban), and environment pollution (lnpollution)Footnote 5 as control variables. Specifically, this study uses districts and counties GDP, total population, the number of students enrolled in secondary school in the total population, the proportion of tertiary industry to secondary industry, the number of invention patent applications, urbanisation rate, and PM2.5 concentration. All data, except for environment pollution, are from the China County Statistical Yearbook and China Regional Economic Statistical Yearbook. In terms of natural factors, climate change will have a direct impact on agricultural sector production and enterprise productivity (Ren et al. 2024), which in turn will affect regional common prosperity. Referring to Shah et al. (2024), and Lee et al. (2024), this paper adds the district and county average temperature (lntemp), average precipitation (lnprecip)Footnote 6, and their squared terms as control variables to control for the effects of temperature and precipitation on common prosperity.

Sample selection

The real practice of GEP accounting and assessment is often conducted on a district and county basis. Therefore, this study takes county-level cities (districts, counties, county-level cities, and flags) in China as the research object. The implementation of GEP assessment is mainly concentrated in 2018 and beyond. To assess the medium- and long-term impact of GEP assessment as much as possible, and after considering data availability, indicators, and the comparability of samples, this paper ultimately chooses panel data of 1942 districts and counties from 2012 to 2022 for empirical analyses.

Results and discussion

The impact of GEP assessment on common prosperity

This paper adopts a staggered DID model controlling for year and region fixed effects to test the impact of GEP assessment on urban and rural residents’ income gap and income level. The results of benchmark regression are shown in Tables 3–4.

Table 3 reveals the impact of GEP assessment on the urban-rural income gap. The results reveal a significant negative effect of GEP assessment on the urban-rural income gap at the 1% level. Taking the regression results in column (4) as an example, after adding all control variables and controlling for year and region fixed effects, the income gap in districts and counties that conducted GEP assessment significantly decreased by 0.1122 compared with districts and counties that did not engage in GEP assessment. GEP assessment emphasises the transformation of local ecosystem products into real economic benefits, and rural residents with richer ecosystem products receive more income as a result. As the beneficiaries of ecosystem product supply, urban residents pay for the ecological environment and eco-tourism they enjoy. Economic compensation between urban and rural regions has significantly narrowed the income gap between urban and rural residents (Liu et al. 2023a). These results support our research hypothesis 1.

GEP assessment can increase rural residents’ incomes (Table 4), and this conclusion remains valid after introducing control variables and time fixed effects. In contrast, the effect of conducting GEP assessment on urban residents’ income level is insignificant. The effect is no longer significant after considering control variables and fixed effects. Therefore, the positive effects of GEP assessment on common prosperity of urban and rural regions are highlighted in two aspects: the promotion of rural residents’ income and the narrowing of the income gap between urban and rural regions. The reason for this is that the economic structures of urban and rural regions are different. The economic structure of rural regions usually revolves around industries that are highly dependent on natural resources, such as agriculture, forestry, and fishery, etc. Local government’s investment in ecological protection and restoration in rural regions has gradually increased. Soil improvement and optimisation of irrigation conditions have improved agricultural output, thereby directly increasing rural residents’ income. The natural resources in rural regions are more concentrated, GEP assessment will promote government’s favourable policies tilted towards rural regions, which can be quickly transformed into the actual growth of residents’ income. The urban regions mainly rely on capital-intensive industries such as industry and services. The urban industrial chain is longer and involves a variety of factors. Its output process is less directly dependent on ecosystem improvement. Therefore, GEP assessment is more inclined to improve life quality of urban residents. The increase in green regions and air quality improvement are more reflected in the improvement of life quality and health benefits. The impact of this welfare effect on residents’ income shows a strong “lag”.

Parallel trend test and dynamic effect analysis

One of the conditions for employing the DID model to accurately estimate policy effects is meeting the parallel trend assumption (Bertrand et al. 2004). Therefore, this study adopts the event study method to conduct the parallel trend test and dynamic effect analysis (Chen et al. 2021; Jin and Chen 2024). The test model is as follows:

where \({D}_{it}^{k}\) is a dummy variable for year k after conducting GEP assessment.

Examining the year prior to GEP assessment implementation (k = 1) as the base period, this study obtains the dynamic effect of the impact of GEP assessment on the urban-rural income gap (Fig. 3a) and the rural residents’ income (Fig. 3b). Figure 3a, b show that the coefficients of beta-7 to beta-2 do not reject the original hypothesis that the coefficient value is zero. It indicates that the parallel trend test of gap and lnrincome between the experimental group and control group passes.

The coefficient of gap is rising in absolute value after GEP assessment is conducted, which indicates that the effect of GEP assessment on the reduction of income gap is decreasing and then increasing. One possible reason for this is the resource redistribution effect. In the early stage of GEP assessment, district and county governments, to reach the assessment target of GEP, may adjust the structure of financial expenditures more substantially. It prioritised benefiting those rural regions with rich ecological resources but a weaker economic base through ecological compensation and environmental protection funds distribution. The initial ecological compensation and project support significantly raised these rural residents’ income, thus narrowing the income gap with the more affluent residents in urban regions. In the later stages of GEP assessment, the resource allocation of district and county governments gradually equalizes. The subsidies and support concentrated at the initial stage no longer increase, and the income gap reduction effect of GEP assessment is weakened. This can also be verified by the coefficient change of lnrincome in Fig. 3b. This shows that in the early stage of GEP assessment, the promotion effect of GEP assessment on rural residents’ disposable income is increasing, while in the later stage is declining. Based on this, the hypothesis of the parallel trend of DID is verified.

Robustness tests

Selection bias test

The DID model can weaken the endogeneity problem of omitted variables. However, the problems of sample selection bias due to missing sample data in some districts and sample selection bias and self-selection bias due to non-complete randomization in the selection of the experimental group still lead to biased estimates. In this regard, referencing the relevant literature (Du et al. 2023), once again this study takes the urban-rural income gap and rural residents’ income as explained variablesFootnote 7, and adopts the Heckman two-stage model and propensity score matchingFootnote 8 (PSM) to rule out sample selection and self-selection problems, presenting the respective test results in Tables 5 and 6.

In using the Heckman two-stage method, this paper firstly utilizes variables such as economic social and natural factors as selection variables, and the GEP assessment as explanatory variables, which are calculated after estimation using the probit model to obtain the Inverse Mills Ratio (IMR). Then IMR is added to the baseline model. Table 5 shows the coefficient of GEP assessment is still significantly in line with the expectation, which indicates the robustness of benchmark findings.

For PSM-DID, this study first matches the propensity values of the factors that may affect the implementation of GEP assessment policy, encompassing ecological environment, resource endowment, and socio-economic development, screening out experimental and control group samples with similar conditions to conduct DID estimation. Table 6 presents the regression results, revealing that after propensity matching, the effect of GEP assessment implementation on narrowing the urban-rural income gap and increasing rural residents’ income remains significantly positive at the 1% level, validating the baseline conclusion that GEP assessment implementation can narrow the income gap and promote rural residents’ prosperity. This further confirms the robustness of benchmark findings.

Placebo test

In the real process of regional economic development and social operation, other unobserved factors may also affect common prosperity. To exclude the possible influence of non-policy factors on the findings of this paper, with reference to (Bai et al. 2023), this study randomly assigned the sample counties of the control group to the experimental group that served as a placebo, and conducted random sampling on 21,406 samples 1000 times using the aforementioned benchmark model, presenting the results in Fig. 4.

The placebo test results demonstrate that the coefficient values and p-values (greater than 0.1) of the urban-rural income gap and rural residents’ income variables after 1000 randomised trials are all concentrated near 0 in the form of normal distribution and the estimation point of benchmark regression is outside the kernel density curve of the random shocks. Therefore, the impact of GEP assessment on the income gap and rural residents’ incomes are not subject to other unobservable stochastic factors caused by random unobservable factors (Shih et al. 2009). This further validates the robustness of the findings in this paper.

Varying sample time and scope

To confirm whether the findings of this paper remain consistent across different samples and time horizons, this paper conducts a robustness test for varying the sample time and horizon. This paper shortens the sample interval to 2012–2019 as a way to exclude the shock of the COVID-19. The results are presented in the first two columns of Table 7. The economic and social situation varies considerably among China’s districts and counties, especially those belonging to municipalities or provincial capitals. These areas often serve as the core of the entire provincial administrative region and have stronger economic and social strengths. These samples are prone to extreme variable values that affect the estimation results. Therefore, the paper re-estimates the estimation by excluding these counties and the results are shown in the last two columns of Table 7. It can be seen from Table 7 that the coefficients on the GEP assessment are consistently consistent with what is expected, both in terms of time and sample size considered, which will further help to ensure the robustness of the findings.

Advanced analysis

Mechanism analysis

To further explore the mechanism of GEP assessment on promoting common prosperity, this study chooses the mediation model to conduct the mechanism test. Referencing existing literature (Wu et al. 2024), the study analyzes the mechanism of GEP assessment to promote rural residents’ income from four aspects: government attention, fiscal support, green finance, and agricultural development. The results are shown in Table 8.

Columns (1)-(2) of Table 8 demonstrate the mediating role of government attention. The coefficient of GEP assessment in the first column is significantly positive, which indicates that GEP assessment can increase the governments attention to ecosystem product value realisation. The coefficient of government attention to ecosystem product value realisation in the second column is significantly positive, indicating that the government attention to ecosystem product value realisation can increase the income level of rural residents, which is consistent with the conclusion of the analysis by Sheng and Wang (2022). Observe again that the coefficient of GEP assessment in the second column has decreased compared with the coefficient of GEP assessment in the baseline regression, indicating that the government attention does play a partial mediating role. An increase in the government’s attention will guide the flow of resources into the market for ecosystem products, accelerate the construction and improvement of the market for ecosystem products, and bring ecosystem products gathered in the rural regions into the market circulation to increase the income of rural residents.

Columns (3)-(4) of Table 8 demonstrate the mediating role of fiscal support. The coefficient of GEP assessment in the third column is significantly positive, which indicates that GEP assessment can increase the government’s fiscal support, while the coefficient of fiscal support in the fourth column is significantly positive, which suggests that the increase of fiscal support can contribute to the increase of rural residents’ income, which is basically in line with the conclusions of Sidek (2021) in his study on the government’s expenditure and income inequality. Moreover, the coefficient of GEP assessment in the fourth column declines compared to the coefficient of GEP assessment in the benchmark regression, indicating that fiscal support does play a partial mediating role. The increase in fiscal support is mainly reflected in rural regions rich in natural resources, where the construction of ecological projects and government transfers will quickly and directly increase the income of rural residents.

Columns (5)-(6) of Table 8 demonstrate the mediating role of green finance. The coefficient of GEP assessment in the fifth column is significantly positive, which indicates that GEP assessment can increase the green finance in the prefecture level city where the county is located. The coefficient of GEP assessment in the sixth column is significantly positive, which indicates that green finance development can increase the income of rural residents. Li et al. (2024b) have already empirically tested the positive effect of green finance on the increase of rural residents’ income and the reduction of the income gap. The coefficient of GEP assessment in the sixth column has decreased compared to the coefficient of GEP assessment in the benchmark regression, indicating that green finance plays a partly mediating role. The development of green finance can provide rural residents with low-interest or preferential green loans dedicated to the development of eco-agriculture and green industries. Rural residents use the loan funds to purchase ecological planting equipment to reduce dependence on chemical fertilizers and pesticides, improve the quality of agricultural products, and obtain higher selling prices in the market, which in turn directly increases the income of rural residents.

Columns (7)-(8) of Table 8 demonstrate the mediating role of agricultural development. The coefficient of GEP assessment in the seventh column is significantly positive, which indicates that GEP assessment can contribute to the development of local agriculture. The coefficient of agricultural development in the eighth column is significantly positive, which indicates that agricultural development can increase the income of rural residents. This is obvious, as one of the main sources of income for rural residents is income from farming. Observe again that the coefficient of GEP assessment in the eighth column has decreased compared to the coefficient of GEP assessment in the benchmark regression, indicating that agricultural development plays a partly mediating role. Agricultural development can create more green jobs for the local region. More rural residents thus increase their sources of income, and their income level increases significantly, which in turn is conducive to the realisation of common prosperity.

Regional heterogeneity analysis

This study intends to analyze in depth the influence of districts and counties differences on the policy effect of GEP assessment from the three aspects of resource carrying capacity (type), government fiscal capacity (capacity), and public environmental attention (attention). The results are shown in Table 9.

Heterogeneity of resource carrying capacity

The Chinese government delineated the resource and environmental carrying capacity of different districts and counties in the Main Functional Area Planning issued in 2010, including three categories: restricted development areas, key development areas, and optimized development areas. Among the 1946 samples, the number of restricted development areas, key development areas, and optimised development areas are 1155, 663, and 125, respectively. Therefore, according to the differences in the resource carrying capacity of the districts and counties, the restricted development area is assigned a value of 1, the key development area is assigned a value of 2, and the optimized development area is assigned a value of 3, with the higher value representing the stronger resource carrying capacity. After interacting type with GEP assessment, it is added to the benchmark regression model to get the results of the first and fourth columns in Table 9.

In Table 9, the coefficients of treat × post × type in columns (1) and (4) are significantly negative and positive, respectively, indicating that as the resource carrying capacity of counties improves, the effect of GEP assessment on promoting common prosperity gradually weakens. The reason may lie in the fact that counties with stronger resource carrying capacity tend to have higher economic development intensity, with the benefits of the policy being more prominently reflected in the green economic transition. However, the increase in rural residents’ income remains relatively limited (Chen et al. 2022). In contrast, counties with weaker resource carrying capacity and limited economic development potential are more likely to prioritize direct ecological compensation and rural infrastructure construction (Shang et al. 2018), which increases rural residents’ income and employment.

Heterogeneity of government fiscal capacity

To investigate the heterogeneity of government fiscal capacity differences on GEP assessment affecting common prosperity, this paper divides districts and counties into two groups according to the government’s fiscal revenues into high fiscal capacity (taking the value of 1) and low fiscal capacity (taking the value of 0). Then it interacted with GEP assessment into the benchmark regression model, and the results are displayed in the second and fifth columns of Table 9.

In Table 9, the coefficients of treat × post × capacity in columns (2) and (5) are significantly positive and negative, respectively, indicating that as the fiscal capacity of counties strengthens, the effect of GEP assessment gradually increases. Governments with stronger fiscal capacity are able to implement broader and more long-term ecological protection projects following the introduction of GEP evaluation, which helps improve both the yield and quality of agricultural products (Ren et al. 2024), ultimately raise rural residents’ incomes faster. In contrast, in regions with weaker fiscal capacity, governments may only be capable of carrying out small-scale ecological protection measures with limited impact, making it difficult to significantly enhance ecosystem services and thereby diminishing the effectiveness of the GEP assessment policy.

Heterogeneity of public environmental concerns

The sample is divided into high environmental concern regions and low environmental concern regions according to the level of public environmental concern (Li et al. 2022)Footnote 9, and assigned the values of 1 and 0 respectively, which interact with the GEP assessment and put into the benchmark regression model. The results in the third and sixth columns of Table 9 show the heterogeneity results of public environmental concern.

In Table 9, the coefficient of treat × post × attention in columns (3) and (6) are significantly positive and negative, respectively, indicating that as the public environmental concerns of counties strengthens, the effect of GEP assessment gradually increases. In regions of high environmental concern, residents identify more with environmental protection and eco-friendly products, and are more willing to pay a premium for these ecosystem products (Brécard et al. 2009), driving the development of markets for ecosystem products. High-quality agricultural products produced under the GEP assessment can be marketed more easily within the region without having to rely on inter-regional trade. The construction of such local markets reduces the costs of logistics and middlemen, further increasing the profits of rural residents. More importantly, as ecosystem product market continues to improve, a green and eco-centered industrial chain will provide farmers with sustained opportunities to sell green products (Unay-Gailhard and Bojnec 2019), contributing to the stabilization of farmers’ income.

Conclusion and discussion

Conclusion

Based on panel data of 1946 districts and counties in China from 2012 to 2022, this study constructs a staggered DID model to evaluate the role and impact mechanism of GEP assessment on urban and rural common prosperity. This study also identifies the heterogeneous effects of GEP assessment in different types of districts and counties.

This study yields three notable findings. First, GEP assessment implementation is an important driving force for advancing the common prosperity of urban and rural regions. GEP assessments conducted by district and county governments can increase rural residents’ income, but the effect on urban residents’ income is insignificant, significantly narrowing the urban-rural income gap. Second, GEP assessment implementation may promote the realisation of common prosperity through government attention, fiscal support, green finance, and agriculture development. The degree of local government’s attention to the ecosystem product value realisation, the strength of government public expenditure, the intensity of green finance, and ecological industry development all have a positive influence on promoting common prosperity across urban and rural regions. Third, GEP assessment has a more significant effect on promoting common prosperity in key ecological function areas, districts and counties with strong fiscal capacity and high public environmental concern. The stronger the fiscal capacity of districts and counties, and the higher the local public’s concern for environmental protection, the more significant the effect of GEP assessment will be.

Policy implications

Based on the research findings, the paper draws the following policy implications:

First, the central government should actively integrate GEP assessment into the performance evaluation framework, utilizing it as a tool to advance common prosperity. Initially, GEP assessment pilots could be introduced in districts and counties with limited resource carrying capacity, strong fiscal capacity, or heightened public environmental awareness, with differentiated GEP assessment targets set. Higher-level governments should offer policy guidance and financial support to subordinate governments, establishing a fiscal allocation mechanism linked to GEP assessment outcomes. Drawing on experiences from pilot programs, the assessment model should be iteratively improved and gradually scaled to the provincial level, and ultimately supporting the realisation of common prosperity at a societal level.

Second, local governments should adopt various approaches to diversify income sources in rural areas. Green financial support should be increased to reduce the financing costs of rural ecological projects. It is necessary to introduce a government risk compensation mechanism and explore the issuance of special loans for eco-agriculture through policy banks, agricultural development banks, to lower the financing threshold of rural eco-projects. The ecological compensation mechanism should be improved to broaden the ways for rural residents to increase their income. The government should provide policy and technical support to promote the implementation of projects such as carbon sequestration and forest rights transfers. The government can also establish a mechanism for synergistic development of urban and rural industries. Efforts should be made to build the brand of rural ecological products to enhance consumer acceptance of these products. Local governments can join forces with commercial organizations to promote ecosystem products regularly, and provide sales support to rural residents.

Third, local governments should fully stimulate the subjective initiative of all kinds of subjects to participate in the realisation of the value of ecosystem products. Local governments can attract the participation of all parties through tax incentives and subsidies, and promote the establishment of trading platforms for ecosystem products. Enterprises and individuals can directly participate in the supply and trading of ecosystem products, and enhance the transparency and vitality of the market. Furthermore, the government should strengthen publicity and education, to enhance public awareness of ecosystem products. It can provide training for enterprises, individuals, and social organizations on knowledge related to ecosystem products. In addition, local governments can establish a public-private partnership model with enterprises and social organizations. Universities and research institutions are encouraged to cooperate with enterprises to promote the research, and development of eco-technologies, and enhance the market competitiveness of ecosystem products.

Limitations and further research

Of course, there remains room for further expansion in this paper. First, subsequent studies can develop indicators to measure common prosperity, which includes material and spiritual prosperity. Common prosperity not only refers to urban and rural common prosperity, but also reflects that of a population and region. This study only uses the urban-rural income gap and urban and rural residents’ incomes as the explained variables for measuring common prosperity. Further research should construct a multi-dimensional evaluation index system for common prosperity for empirical analysis. Second, the mechanism of GEP assessment on common prosperity should be explored in more depth. This study analyses the impact of GEP assessment on common prosperity by examining government attention, fiscal support, green finance, and agriculture development. However, future studies should expand the research direction to explore the impact of GEP assessment on common prosperity in terms of participating subjects, and the contributions of different stakeholders.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are provided as supplementary files.

Notes

Five prefecture-level cities in China still do not have districts or counties; namely Dongguan, Guangdong Province; Zhongshan, Guangdong Province; Jiayuguan, Gansu Province; Danzhou, Hainan Province; and Sansha, Hainan Province. Among these five regions, Dongguan, Zhongshan, and Jiayuguan have neither cancelled GDP assessment nor carried out GEP assessment. Danzhou and Sansha have cancelled GDP assessment and have not conducted GEP assessment. Since we use districts and counties as research samples, these five regions are no longer considered in subsequent analysis.

Industrial ecologicalisation introduces environmentally friendly technologies to transform the product ecologically. Based on the perspective of industrial organisation and management, this process achieves an increase in output while maintaining good environmental benefits. Ecological industrialisation connects primary, secondary, and tertiary industries to revitalize ecological resources and achieve value-added ecological resources through market-oriented means.

This paper constructs a keyword dictionary of ecosystem product value realisation from the connotation, model path, and practice. It includes 51 keywords such as ecosystem product, ecosystem product value realisation, ecological compensation, payment for ecosystem services, etc. Based on the above keywords, this paper extracts the text of annual work report from each government website.

The green finance index is measured from seven indicators of green investment, green insurance, green bond, green fund, green support, and green equity using entropy method.

The data are from the Third Pole Environment Data Centre.

The data are from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

As noted above, the effect of GEP assessment on urban residents’ income is insignificant; therefore, there is no need to conduct model testing with urban residents’ income as explained variable.

In conducting dynamic panel analysis, cross-sectional PSM may suffer from self-matching problems, and period-by-period PSM may lead to changes in the matched objects before and after policy shocks. However, PSM is still a superior solution for eliminating the problem of sample selection bias (Chen et al. 2021).

This paper utilizes the search volume of keywords related to environmental pollution (phrases such as environmental pollution, ecological environment, air pollution, air quality, etc.) that are familiar to the public in Baidu index to construct public ecological and environmental concern indicators.

References

An X, Li H, Wang L, Wang Z, Ding J, Cao Y (2018) Compensation mechanism for urban water environment treatment PPP project in China. J Clean Prod 201:246–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.003

Bai D, Hu J, Irfan M, Hu M (2023) Unleashing the impact of ecological civilization pilot policies on green technology innovation: evidence from a novel SC-DID model. Energ Econ 125:106813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2023.106813

Bertrand M, Duflo E, Mullainathan S (2004) How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? Q J Econ 119(1):249–275. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355304772839588

Brécard D, Hlaimi B, Lucas S, Perraudeau Y, Salladarré F (2009) Determinants of demand for green products: an application to eco-label demand for fish in Europe. Ecol Econ 69(1):115–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.07.017

Cao H, Li M, Qin F, Xu Y, Zhang L, Zhang Z (2022) Economic development, fiscal ecological compensation, and ecological environment quality. Int J Env Res Pub He 19(8):4725. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084725

Cao Y, Zhang X (2018) Are they satisfied with land taking? Aspects on procedural fairness, monetary compensation and behavioral simulation in China’s land expropriation story. Land Use Policy 74:166–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.08.027

Chanieabate M, He H, Guo C, Abrahamgeremew B, Huang Y (2023) Examining the relationship between transportation infrastructure, urbanization level and rural-urban income gap in China. Sustainability 15(10):8410. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108410

Chen KZ, Mao R, Zhou Y (2023) Rurbanomics for common prosperity: new approach to integrated urban-rural development. China Agr Econ Rev 15(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1108/CAER-12-2021-0256

Chen W, Yao L (2024) The impact of digital economy on carbon total factor productivity: a spatial analysis of major urban agglomerations in China. J Environ Manag 351:119765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119765

Chen Y, Cheng L, Lee C-C, Wang C (2021) The impact of regional banks on environmental pollution: evidence from China’s city commercial banks. Energ Econ 102:105492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105492

Chen Y, Cheng L, Lee CC (2022) How does the use of industrial robots affect the ecological footprint? International evidence. Ecol Econ 198:107483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107483

Chuc Anh T, Rasoulinezhad E, Sarker T (2020) Investigating solutions for the development of a green bond market: Evidence from analytic hierarchy process. Financ Res Lett 34:101457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2020.101457

Civeira G, Lado Liñares M, Vidal Vazquez E, Paz González A (2020) Ecosystem services and economic assessment of land uses in Urban and Periurban areas. Environ Manag 65(3):355–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-020-01257-w

Cong X, Qi Z, Wang S, Su P, Wang L, Šaparauskas J, Górecki J, Skibniewski MJ (2023) Ecological welfare performance evaluation and spatial-temporal difference evolution of Blue Economic Zones: a case study of the blue economic zone of Shandong Peninsula. Land 12(10):1886. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12101886

Costanza R, Kubiszewski I, Giovannini E, Lovins H, McGlade J, Pickett KE, Ragnarsdóttir KV, Roberts D, De Vogli R, Wilkinson R (2014) Time to leave GDP behind. Nature 505(7483):283–285. https://doi.org/10.1038/505283a

Dong K, Wei S, Liu Y, Zhao J (2023) How does energy poverty eradication promote common prosperity in China? The role of labor productivity. Energy Policy 181:113698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2023.113698

Dong K, Dong X, Ren X (2020) Can expanding natural gas infrastructure mitigate CO2 emissions? Analysis of heterogeneous and mediation effects for China. Energ Econ 90:104830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2020.104830

Du Y, Sun F, Cao L (2023) Can common institutional ownership promote enterprise upgrading? J Quant Technol Econ 40(10):181–201. https://doi.org/10.13653/j.cnki.jqte.20230822.001. (in Chinese)

Ermagun A, Janatabadi F, Maharjan S (2023) Inequity analysis of spatial mismatch for low-income socially vulnerable populations across America. Transp Res D Transp Environ 118:103692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2023.103692

Fan Y, Ji J, Jia C, Lei M, Wu W, Zheng Y, Wang Z, Zhang G, Song Y (2024) The valuation of gross ecosystem product in the three provinces in northeast of China. Nat Resour Forum 48(1):257–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-8947.12325

Frélichová J, Vačkář D, Pártl A, Loučková B, Harmáčková ZV, Lorencová E (2014) Integrated assessment of ecosystem services in the Czech Republic. Ecosyst Serv 8:110–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.03.001

Gao Y, Zheng J, Bu M (2014) Rural-urban income gap and agricultural growth in China an empirical study on the provincial panel data, 1978–2010. China Agr Econ Rev 6(1):92–107. https://doi.org/10.1108/CAER-02-2012-0016

Guan X, Du Q, Zhang W, Wang B (2021) Study on the pricing of water rights transaction between irrigation water users based on cooperative game in China. Water 13(12):1672. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13121672

Gunter U, Ceddia MG, Leonard D, Tröster B (2018) Contribution of international ecotourism to comprehensive economic development and convergence in the Central American and Caribbean region. Appl Econ 50(33):3614–3629. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2018.1430339

Hao C, Wu S, Zhang W, Chen Y, Ren Y, Chen X, Wang H, Zhang L (2022) A critical review of Gross ecosystem product accounting in China: status quo, problems and future directions. J Environ Manag 322:115995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115995

Hu C, Chen C, Findlay C, Wu Y (2024) Foreign direct investment, off-farm employment and rural labour income: evidence from China. Appl Econ 56(41):4974–4988. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2023.2276086

Huang Z, Xu H, Li J, Luo N (2020) Has highway construction narrowed the urban-rural income gap? Evidence from Chinese cities. Pap Reg Sci 99(3):705–723. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12504

Ji C-J, Hu Y-J, Tang B-J (2018) Research on carbon market price mechanism and influencing factors: a literature review. Nat Hazards 92(2):761–782. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-018-3223-1

Jiakui C, Abbas J, Najam H, Liu J, Abbas J (2023) Green technological innovation, green finance, and financial development and their role in green total factor productivity: empirical insights from China. J Clean Prod 382:135131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.135131

Jiang H, Wu W, Wang J, Yang W, Gao Y, Duan Y, Ma G, Wu C, Shao J (2021) Mapping global value of terrestrial ecosystem services by countries. Ecosyst Serv 52:101361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2021.101361

Jin M, Chen Y (2024) Has green innovation been improved by intelligent manufacturing? - Evidence from listed Chinese manufacturing enterprises. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 205:123487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2024.123487

Joshi AP, Joshi S, Purohit H (2023) Unveiling the green paradigm: introducing gross environment product (GEP)-The frontier in ecological growth. Ecol Indic 156:111192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.111192

Lee CC, Lee CC (2022) How does green finance affect green total factor productivity? Evidence from China. Energ Econ 107:105863. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2022.105863

Lee CC, Zeng M, Luo K (2024) How does climate change affect food security? Evidence from China. Environ Impact Asses 104:107324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2023.107324

Li C, Su K, Liang X, Jiang X, Wang J, You Y, Wang L, Chang S, Wei C, Zhang Y, Liao Z (2023a) Identification of priority areas to provide insights for ecological protection planning: a case study in Hechi, China. Ecol Indic 154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.110738

Li FF, Wang FK, Liu H, Huang K, Yu YJ, Huang BR (2023b) A comparative analysis of ecosystem service valuation methods: Taking Beijing, China as a case. Ecol Indic 154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.110872

Li WW, He S, Chen ER, Xia T, Jin YM, Tang BP, Chen S (2024a) Indices and methods for evaluating gross ecosystem product in sea areas: a case study in Changdao County, China. Front Mar Sci 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2024.1356149

Li X, Hu Z, Cao J, Xu X (2022) The impact of environmental accountability on air pollution: a public attention perspective. Energ Pol 161:112733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112733

Li Y, Shen YF, Chen YF (2024b) Spatial spillover effect of green finance on urban-rural income gap. Appl Econ Lett. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2024.2331249

Li YH, Wang HR, Liu CJ, Sun JH, Ran QC (2024c) Optimizing the valuation and implementation path of the gross ecosystem product: a case study of Tonglu County, Hangzhou City. Sustainability 16(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041408

Liu GG, Zhou YX, Ge YX (2024a) How does ecological compensation promote the common prosperity of farmers in the ecological protection red line areas? China population, resources and environment (04): 197–209. (in Chinese)

Liu J, Su X, Liu Y, Shui W (2024b) A review of research on progress in the theory and practice of eco-product value realization. Land 13(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/land13030316

Liu M, Bai L, Khan HS, Li H (2023a) The influence of the grassland ecological compensation policy on regional Herdsmen’s income and its gap: evidence from six pastoralist provinces in China. Agriculture-Basel 13(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13040775

Liu Y, Dong K, Wang K, Fu X, Taghizadeh-Hesary F (2024c) How do green bonds promote common prosperity? Evidence from Chinese prefecture-level cities. J Risk Financ https://doi.org/10.1108/JRF-02-2024-0048

Liu Y, Dong KY, Wang JD, Taghizadeh-Hesary F (2023b) Towards sustainable development goals: does common prosperity contradict carbon reduction? Econ Ana Policy 79:70–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2023.06.002

Liu Y, Dong X, Dong K (2023c) Pathway to prosperity? The impact of low-carbon energy transition on China’s common prosperity. Energ Econ 124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2023.106819

Liu Y, Liu J, Zhou Y (2017) Spatio-temporal patterns of rural poverty in China and targeted poverty alleviation strategies. J Rural Stud 52:66–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.04.002

Ma N, Ma X (2024) Does the ESG rating promote common prosperity within enterprises? Financ Res Lett 69:106066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2024.106066

Meloni C, Grazini C, Marino M, Rocchi B, Severini S (2024) Are rural households poorer than non-rural households in Europe? J Rural Stud 106:103214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2024.103214

Ouyang Z, Song C, Zheng H, Polasky S, Xiao Y, Bateman IJ, Liu J, Ruckelshaus M, Shi F, Xiao Y, Xu W, Zou Z, Daily GC (2020) Using gross ecosystem product (GEP) to value nature in decision making. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117(25):14593–14601. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1911439117

Qin B, Yu Y, Ge L, Yang L, Guo Y (2022) Does eco-compensation alleviate rural poverty? New evidence from national key ecological function areas in China. Int J Env Res Pub He 19(17):10899. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710899

Ren X, An Y, Jin C, Yan C (2024) Weathering the policy storm: how climate strategy volatility shapes corporate total factor productivity. Energ Econ 134:107553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2024.107553

Saito Y (2017) Effects of patent protection on economic growth and welfare in a two-R & D-sector economy. Econ Model 62:124–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2017.01.015

Sha Z, Ren D, Li C, Wang Z (2024) Agricultural subsidies on common prosperity: evidence from the Chinese social survey. Int Rev Econ Financ 91:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2023.12.006

Shah WUH, Lu Y, Liu J, Rehman A, Yasmeen R (2024) The impact of climate change and production technology heterogeneity on China’s agricultural total factor productivity and production efficiency. Sci Total Environ 907:168027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.168027

Shaker RR (2018) A mega-index for the Americas and its underlying sustainable development correlations. Ecol Indic 89:466–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.01.050

Shang W, Gong Y, Wang Z, Stewardson MJ (2018) Eco-compensation in China: theory, practices and suggestions for the future. J Environ Manag 210:162–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.12.077

Shen Y, Yi X, Chen M, Ouyang Z (2024) Gross ecosystem product accounting in Miyun County: the supply and use of ecosystem services. Front Ecol Ecol 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2024.1367768

Sheng J, Wang H (2022) Participation, income growth and poverty alleviation in payments for ecosystem services: the case of China’s Wolong Nature Reserve. Ecol Econ 196:107433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107433

Shih RA, Griffin BA, Jewell A, Eibner C, Bird C, Cushman M, Liao D, Eaton C, Margolis H, Whitsel E (2009) Ambient particulate matter air pollution and incident venous thromboembolism in the women’s health initiative hormone trials (WHI HTs). Circulation 120(18):S535–S535

Sidek NZM (2021) Do government expenditure reduce income inequality: evidence from developing and developed countries. Stud Econ Financ 38(2):447–503. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEF-09-2020-0393

Stem CJ, Lassoie JP, Lee DR, Deshler DD, Schelhas JW (2003) Community participation in ecotourism benefits: the link to conservation practices and perspectives. Soc Nat Resour 16(5):387–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920309177

Su C-W, Liu T-Y, Chang H-L, Jiang X-Z (2015) Is urbanization narrowing the urban-rural income gap? A cross-regional study of China. Habitat Int 48:79–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.03.002

Su C-W, Song Y, Ma Y-T, Tao R (2019) Is financial development narrowing the urban-rural income gap? A cross-regional study of China. Pap Reg Sci 98(4):1779-+–171801. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12428

Uche E, Ngepah N, Onwe JC, Zaman U, Odhiambo NM (2024) A question for sustainable development goal 10: How relevant is innovation patenting receipts to income distributions? Technol Forecast Soc Chang 206:123506–123506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2024.123506

Unay-Gailhard I, Bojnec Š (2019) The impact of green economy measures on rural employment: green jobs in farms. J Clean Prod 208:541–551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.10.160

Wang F, Zhang S, Hou H, Yang Y, Gong Y (2019) Assessing the changes of ecosystem services in the Nansi Lake Wetland, China. Water 11(4):788. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11040788

Wang J, Dong K, Dong X, Taghizadeh-Hesary F (2022a) Assessing the digital economy and its carbon-mitigation effects: the case of China. Energ Econ 113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2022.106198

Wang J, Zhang G (2022) Dynamic evolution, regional differences, and spatial spillover effects of urban ecological welfare performance in China from the perspective of ecological value. Int J Env Res Pub 19(23):16271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316271

Wang L, Su K, Jiang X, Zhou X, Yu Z, Chen Z, Wei C, Zhang Y, Liao Z (2022b) Measuring gross ecosystem product (GEP) in Guangxi, China, from 2005 to 2020. Land 11(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081213

Wang LY, Xiao Y, Ouyang ZY, Wei Q, Bo WJ, Zhang J, Ren L (2017) Gross ecosystem product accounting in the national key ecological function area. China Popul Resour Environ 27(03):146–154

Wang P, Chen Y, Liu K, Li X, Zhang L, Chen L, Shao T, Li P, Yang G, Wang H, Gao S, Yan J (2024) Coupling coordination relationship and driving force analysis between gross ecosystem product and regional economic system in the Qinling Mountains, China. Land 13(2):234. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13020234

Wang Y, Huo Z, Li D, Zhang M (2022c) Evaluation of common prosperity level and regional difference analysis along the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Int J Env Res Pub 19(19). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911851

Wu G, Cheng J, Yang F, Chen G (2024) Can green finance policy promote ecosystem product value realization? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11(1):377. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02849-1

Xu C, Li X (2023) Achieving common prosperity and green development through utilizing natural resources. Resour Policy 85:103881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2023.103881

Xu YS, Zhao WW, Zhang ZJ (2023) The practice of nature-based solutions in China: ecosystem product value realization. Curr Opin Environ Sci Health 36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coesh.2023.100514

Xuan D, Ma X, Shang Y (2020) Can China’s policy of carbon emission trading promote carbon emission reduction? J Clean Prod 270:122383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122383

Yang H, Gou X, Ma W, Xue B (2023) Research and application of GEP: China’s experience in natural capital accounting. Front Environ Sci 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2023.1106654

Yang T, Liu W (2018) Does air pollution affect public health and health inequality? Empirical evidence from China. J Clean Prod 203:43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.242

Yao Y, Jiang L (2021) Urbanization forces driving rural urban income disparity: evidence from metropolitan areas in China. J Clean Prod 312:127748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127748

Yin J, Zhao L (2024) The value expression and driving factors of rural spatial ecological products: a case study of B&Bs in Jiangsu and Zhejiang Provinces, China. Land 13(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/land13030270

Yu FW, Lin S, Sun HXX (2024a) The theoretical logic and promotion strategies of ecological product value realization in the context of common prosperity. Chin Rural Econ (03): 126–141. (in Chinese). https://doi.org/10.20077/j.cnki.11-1262/f.2024.03.007

Yu L, Lu W, Choguill C, Li M (2023) Liangshan Bank, a hybrid model of payment for ecosystem services governance in rural development: the case of Baofu, China. Habitat Int 138:102879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2023.102879

Yu L, Wang Y, Li M (2024b) The emergence of counter-urbanisation in China: can it be a pathway for rural revitalisation? Habitat Int 144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2023.102998

Yuan G, Ye Q, Sun Y (2021) Financial innovation, information screening and industries’ green innovation-Industry-level evidence from the OECD. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 171:120998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120998

Yuan Y, Wang M, Zhu Y, Huang X, Xiong X (2020) Urbanization’s effects on the urban-rural income gap in China: a meta-regression analysis. Land Use Policy 99:104995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104995

Zhang BB, Wang Y, Shen GJ (2024) Basin horizontal ecological protection compensation and common prosperity. J World Econ (04): 129–153. (in Chinese). https://doi.org/10.19985/j.cnki.cassjwe.2024.04.006

Zhang J, Leoncini R, Tsai Y (2018) Intellectual property rights protection, labour mobility and wage inequality. Econ Model 70:239–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2017.11.006

Zhang T (2023) Can green finance policies affect corporate financing? Evidence from China’s green finance innovation and reform pilot zones. J Clean Prod 419:138289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138289

Zhang Z, Xiong K, Chang H, Zhang W, Huang D (2022) A review of eco-product value realization and ecological civilization and its enlightenment to Karst protected areas. Int J Env Res Pub 19(10):5892. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105892

Zhao T, Jiao F (2024) Does digital financial inclusion promote common prosperity? The role of regional innovation. Electron Commer Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-023-09797-z

Zhao X, Shang Y, Song M (2020) Industrial structure distortion and urban ecological efficiency from the perspective of green entrepreneurial ecosystems. Socio-Econ Plan Sci 72:100757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2019.100757

Zheng H, Wu T, Ouyang Z, Polasky S, Ruckelshaus M, Wang L, Xiao Y, Gao X, Li C, Daily GC (2023a) Gross ecosystem product (GEP): quantifying nature for environmental and economic policy innovation. Ambio 52(12):1952–1967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-023-01948-8