Abstract

Open class is a public-oriented pedagogical practice aimed at enhancing teachers’ professional learning in China. This study examines how teachers conduct the open class and explores how open class facilitates the professional development of teachers. Through fieldwork at Sailing School and semi-structured interviews with nineteen teachers, four distinct phases of participation were identified: beginning (preparation for a show), presentation (using performance strategies), ending (evaluating teachers’ performance), and teamwork (cooperating with peers and students). Open class fosters four key forms of professional learning: enhancing the ability of instructional design, developing PCK in practice, fostering a pedagogical tact, and improving theoretical skills. The findings underscore open class as a platform to bridge the gap between practice and theory, while also highlighting a shift in teacher values from individualism to collectivism in open classes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The importance of improving schools, increasing teacher quality, and improving the quality of student learning has led to a concentrated concern with professional learning of teachers as one important way of achieving these goals (Cameron et al. 2013; Chen, 2022; Morcom and MacCallum, 2022; Stenberg and Maaranen, 2021). Numerous studies indicate that teachers’ professional learning can be enhanced through pedagogical activities (Avidov-Ungar, 2016; Insulander et al. 2019; Kirkwood and Christie, 2006; Vasalampi et al. 2021), including professional learning communities (Brodie, 2021), teachers’ research groups (Chen, 2022), and pedagogical social media (Prestridge, 2019). Consequently, policymakers, researchers, and educational practitioners worldwide are investing in providing pedagogical activities to support teachers’ professional learning, with efforts observed in the U.S. (McCray, 2018), England (Opfer and Pedder, 2011), China (Zhang and Ng, 2011), and New Zealand (Starkey et al. 2009).

In China, open class (gongkaike in Chinese) can be considered a form of pedagogical activity (Sun et al. 2015; Wu and Clarke, 2018). Open class serves as a pedagogical practice for teachers’ professional learning and development (Zhang et al. 2022). During the open class, teachers demonstrate their instructional methods, allowing aspects of their teaching to be closely observed and discussed in detail by their peers (Wu and Clarke, 2018). Meanwhile, the professional development of teachers conducting open classes could be enhanced through this process (Zhang et al. 2022). Although some current research has been conducted on open class (see Sun et al. 2015; Wu and Clarke, 2018; Zhang et al. 2022), no studies have specifically focused on how teachers conduct the open class and examined how open class facilitates conducted teachers’ professional learning.

Therefore, the current study undertakes this task by drawing on fieldwork at Sailing School and semi-structured interviews with nineteen teachers about their experiences conducting the open class. It focuses on how teachers conducted the open class and aims to elucidate how open class facilitates teachers’ professional learning. This study is conducted within the context of China, where open class represents a unique form of pedagogical practice. Unlike in Western educational contexts, where pedagogical activities are generally regarded as private matters (Ross et al. 2011), open class in China is more publicly oriented. Therefore, this study, by exploring open class, aims to provide the international academic community with a more comprehensive understanding of open class and teachers’ professional learning in China.

Literature review

Teachers’ professional learning

Myriad reforms and policies around the globe have focused on improving teacher quality (Fullan and Hargreaves, 2012). Germane to this issue, however, is an acknowledgement that teachers need time to develop, absorb, discuss, and practice new knowledge (Garet et al. 2001). As a result, most research has concluded that activities that effectively support teachers’ professional learning need to be sustained and intensive rather than brief and sporadic (Opfer and Pedder, 2011). In addition, scholars have distinguished between teachers’ professional learning and professional development, defining professional development as externally designed experiences in which teachers are recipients, whereas professional learning is regarded as an internal process where individuals generate professional knowledge through interaction (Timperley, 2011).

The existing literature suggests that two learning levels influence teachers’ professional learning: the individual teacher and the school. Within the teacher’s system, teachers bring past beliefs and experiences to their teaching and learning (Opfer and Pedder, 2011), which not only determine the instructional decisions they make (Raths, 2011), but also influence what they are willing to learn. Teachers’ beliefs, deeply rooted in their past and present experiences, shape their attitudes and values, which in turn affect their decisions about learning (Richardson, 1996). Additionally, teachers bring prior knowledge to their learning (Ball et al. 2001). Given the complexity of teachers’ professional learning, Opfer and Pedder (2011) highlight the interaction and intersection of knowledge, beliefs, practices, and experiences that contribute to the teacher’s individual learning level.

Teachers’ professional learning at the school level centers around the concept of a learning organization. Substantial research and literature on the characteristics of learning organizations have reached a consensus on the processes and practices that promote both organizational and individual learning. As learning organizations, schools can adopt both an internal and external orientation toward learning and improvement for teachers. Some of the most significant school-level influences identified by research are beliefs about learning (Cordingley et al. 2005). These beliefs shape both individual and collective behavior by establishing norms of action (Sampson et al. 1999). In addition to collective pedagogical norms and practices, schools also maintain a collective awareness of their capacity for learning and growth (Goddard, 2003). Therefore, the school-level elements that constitute an organizational orientation to the learning system are similar to those found at the individual level—beliefs about learning, practices, and supports for learning (Opfer and Pedder, 2011).

Defining open class: a pedagogical practice

Open class is a pedagogical practice in China’s K-12 education system for teachers’ professional learning. During open classes, teachers demonstrate their instructional methods, allowing their teaching to be closely observed and discussed in detail by peers (Wu and Clarke, 2018; Sun et al. 2015). The Chinese Ministry of Education established the open class activity format in the early 1950s to organize teacher study groups in schools (Sun et al. 2015). Open class can be understood as a research or communication activity with specific goals and involving multiple participants (e.g., experts, leaders, colleagues, or peers) (An, 2013). According to previous studies, the open classes can be categorized into three types: intra-school open classes (e.g., mentor-mentee training), inter-school open classes (e.g., lessons for research, demonstration of new educational ideas, or evaluation), and competitive open classes (Wu and Clarke, 2018; Sun et al. 2015).

Globally, various pedagogical practices share similarities with the open class. One example is the demonstration class in Canada, where some school boards facilitate teachers’ professional learning by helping them improve their demonstration classes (Grierson and Gallagher, 2009). Another example is the study lesson from Japan, widely implemented to promote teachers’ professional learning through collaborative support (Seleznyov, 2018; Rappleye and Komatsu, 2017). Stigler and Hiebert (1999) introduced the study lesson to the U.S., hoping it would contribute to educational reform. Over the following decades, the study lesson spread as a “traveling reform” from Japan to the rest of the world. This practice has been incorporated into teachers’ professional learning plans in various countries, including Germany (Yoshida et al. 2021), England (Seleznyov, 2019), Brazil (de Macedo et al. 2019), and Singapore (Chong and Kong, 2012). Additionally, the study lesson has been increasingly localized on a global scale, as seen in the learning lesson in Hong Kong (Peter, 2015) and collaborative lesson research in the United States (Lewis et al. 2012).

Although open classes and similar pedagogical practices share the common goal of providing learning opportunities for teachers, they are not identical. Unlike other demonstration-based activities, Chinese educators view open classes as an integral part of daily pedagogical practice. Moreover, the function of open class extends beyond showcasing exemplary teaching; it also serves to evaluate, diagnose, and discuss issues that arise during instruction (An, 2013; Song, 2011; Zhang, 2012). Additionally, in contrast to the study lesson, the open class typically lacks a fixed research topic.

Teachers’ professional learning in China’s context

Teacher professional learning in China is highly institutionalized through Teacher Research Groups (TRGs). TRGs function as learning organizations, consisting of teachers who teach the same subject at the same school and regularly collaborate for educational improvement (Paine and Ma, 1993). Examples include master teacher studios (Zhang et al. 2022) and professional learning communities (Chen, 2022). TRGs organize a wide array of pedagogical activities for teachers’ professional development, with one common activity being the open class (Chen, 2022). The infrastructure for open classes is well-established across China, including in resource-constrained rural schools (Sargent, 2015).

Despite the significance of professional learning, much of the research in this area has produced unsatisfactory results, particularly regarding how teachers conduct the pedagogical activities. These studies reveal that the existing literature often fails to explain how teachers learn from these activities and the contextual factors that support and facilitate this learning. Given the complexity of teachers’ professional learning, the current study suggests that analysis should focus on specific activities, processes, or programs within the context in which teachers teach and learn. In this study, we examine the open class in China as a context, where teachers not only engage in externally designed experiences but also create professional knowledge through interaction. More importantly, there is a limited number of studies focusing on the open class in the existing literature.

Purpose of the current study

To fill the gap in the research, the current study focuses on the specific activities and processes of China’s teachers conduct the open class, it aims to elucidate how open class facilitate teachers’ professional learning. The findings of this study are expected to provide international scholars focused on teachers’ professional learning with a Chinese perspective on the matter. More importantly, it aims to offer the international academic community a deeper understanding of open classes in China. To achieve these purposes, the following research questions were formulated:

RQ1: How do teachers conduct the open class in China?

RQ2: What are the ways in which open class facilitates teachers’ professional learning?

Methodology

We adopted case study (Yin, 2017) as the research method of this study. The case study design allows for a close examination of complex issues, yielding an in-depth and contextualized understanding of a contemporary phenomenon (Yin, 2017). Specifically, participant observation and semi-structed interview were used to collect the data, and the thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) an inductive approach were applied to analyze the data.

Case context

In this study, we selected Sailing School, a public K-12 institution in Fuzhou, the provincial capital of Fujian, China, as the case. Increasingly, schools in China pursue awards to enhance their branding and highlight their achievements in quality education. Awards from open-class activities are crucial indicators of this effort. Like other institutions, Sailing School is also expected to enhance its branding through such awards. Therefore, choosing Sailing School as the case was appropriate.

We gained access to Sailing School for fieldwork due to corresponding author internship experience. She was affiliated with a normal university responsible for training teachers for elementary and secondary schools in Fujian province. According to the university’s training program, all students must complete a practicum at an elementary or secondary school. Based on her internship experience, we were granted the opportunity to conduct fieldwork at Sailing School from September 2022 to January 2023.

Participants

Following the purposive sampling strategy outlined by Miles and Huberman (1994), we initially invited 30 teachers from the Sailing School to participate in the study, and 28 teachers responded to our invitation. The inclusion criteria for these participants were based on their experience with open-class activities. Subsequently, using the maximum variation sampling strategy proposed by Patton (2015), we identified 19 teachers (demographic information is provided in Table 1) in various dimensions, including sex, age, length of service, qualifications, and educational backgrounds.

Data collection

Two sets of qualitative data were collected for this study. The first set was gathered through fieldwork via participant observation. The second author, serving as an intern teacher, observed the entire process of teachers participating in open class activities without any special privileges. She documented the participants’ experiences across 38 open class events, including observational notes, 30 hours of video, and 758 photographs.

The second data set was obtained from semi-structured interviews focusing on two topics: (i) participants’ experiences in participation of open class activities and (ii) their attitudes and feedback on these experiences. This approach was chosen for its versatility and flexibility (Creswell and Poth, 2024), allowing researchers to adjust follow-up questions as needed and providing participants with ample opportunity for verbal expression during the interviews (Polit and Beck, 2010). The interviews were conducted in Mandarin and transcribed into simplified Chinese text immediately afterward. Significant excerpts were selected from the interview data based on preliminary analysis.

Data analysis

The study employed thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) with an inductive approach to explore teachers’ participation in open class activities and how open class activities facilitate their professional learning. The use of an inductive approach to derive themes from raw data helps prevent researchers from imposing predetermined outcomes (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Glaser, 1992).

Initially, the transcribed interviews were read line by line to familiarize the researchers with the data, after which relevant paragraphs and text segments were coded. The qualitative software NVivo 12.0 Plus was utilized to generate initial codes for notable features across the entire dataset. Subsequently, themes were identified by collating the codes, and the thematic map was generated by reviewing these themes in relation to the coded extracts and datasets. In total, 7 main-themes and 9 sub-themes were identified (as shown in Table 2), all sub-themes were identified based on their frequent occurrence and strong connection to the main themes. Finally, each theme was defined and named, and vivid, compelling extracts were selected as examples for our academic report.

Trustworthiness and rigor

To manage the quality of this qualitative research, we employed three methods to enhance trustworthiness and rigor. First, we used data triangulation to minimize error or bias and optimize accuracy in both data collection and analysis processes. By integrating multiple data sources, triangulation allowed us to identify convergent patterns and validate the themes identified in the study (Flick, 2018). Second, we adopted the technique of peer review (Creswell and Creswell, 2022). An independent third-party researcher analyzed a detailed audit trail maintained by the study authors to provide an objective review and avoid bias during the data analysis process. Finally, we conducted member checking by sending the interview transcripts and a draft of the scholarly report to the participants for their review and feedback (Braun and Clark, 2013; Seale, 1999).

Findings

How teachers conduct the open class

In this section, we demonstrate the specific activities and processes of teachers conduct the open class, three main themes emerged to depict the process: beginning: preparing for a show, presenting: strategies of performance, ending: evaluating teachers’ performance, and teams: cooperation with peers and students. These main themes related to nine sub-themes.

Beginning: preparation for a show

Due to the public nature of the open class, teachers often perceive it as a show. Drawing on this performative aspect, we identified three sub-themes to describe the initial preparation phase of the open class: selecting scripts, inviting actors, and rehearsal.

Selecting scripts

Selecting a script is the primary step for teachers preparing for an open class. The script refers to the topic that will be presented during the open class. During the fieldwork, the researchers identified two types of selections: personal and collective scripts. A personal script is based on the individual teacher’s interests and preferences. As teacher Yong explained regarding his recent open class on Chinese poetry:

I hope to lead my students to experience the beauty of traditional culture. Since I enjoy Chinese poetry, I chose it as the topic for the open class.

In contrast, collective script involves choosing topics based on the requirements of the group. As Chen (2022) noted, the open class is linked to learning organizations. Therefore, a collective transcript focuses more on group awards and objectives, indicating that participating in an open class is not just an individual endeavor but a collective one. This perspective is supported by teacher Zhang:

The collective script topic is based more on the characteristics of the topics than on the individual preferences of the teachers involved.

Inviting actors

Once the script is selected, the next crucial element for an open class is the choice of actors. An open class is not merely an individual performance by the teacher; it also requires student participation in supporting roles. Typically, students are chosen at random. However, in some cases, teachers may select students themselves, as Zhao explained:

In some intra-school open classes, I prefer to choose students who are compliant or with whom I am familiar.

Teachers are invited to participate as actors under two main conditions. The first is when young teachers are preferred. Audiences tend to favor young teachers because they are perceived as having a better image and being more capable than older teachers. In contemporary society, the homogenized aesthetic standard favoring youth has become the norm. Young teachers, who align with this standard, are often selected. The second condition depends on the collective script, as teacher Li elaborated:

Not all teachers excel in all types of topics. Sometimes an open class has a prescribed topic, and teachers are chosen if they are proficient in that topic.

Rehearsal

Rehearsal is the final stage of preparation before the open class. The term “moke” (磨课 in Chinese) has been conceptualized by teachers to describe the repeated rehearsals through which they refine their lessons. This process involves inviting various students for trial teaching sessions to closely simulate the actual teaching environment. As teacher Shen emphasized:

“Moke” is a crucial preparatory step. You can immediately adjust your instructional design based on students’ performance during this process.

The purpose of “moke” is to create a realistic performance context for teachers participating in the open class, thereby minimizing the risk of errors during the actual lesson. Furthermore, the higher the level of the open class, the more time and effort teachers devote to rehearsal. Teacher Qian shared her experience:

Because it was a high-level inter-school open class, with many teachers and leaders present to observe, I rehearsed sixteen times in total to avoid making any mistakes.

Presentation: using performance strategies

In open class, teachers demonstrate and are assessed publicly on their teaching activities by audiences. In this vein, to present a better show, teachers will adopt various strategies. In data analysis, we identified three sub-themes to describe their performance strategies: rendering the mood, setting nodes, and dressing up.

Rendering the mood

Rendering a mood is a common strategy used by teachers at the beginning of an open class. Typically, they construct a context to set the desired atmosphere. As researcher observed during the fieldwork in a math open class:

The math lesson was for elementary students and focused on the topic of money. At the start of the class, the teacher posed the question: “If I give you ten yuan, what could you buy in the supermarket today?”

By constructing this teaching context, the teacher guided students to develop an embodied understanding of money in a real-world scenario during the initial stages of learning. Additionally, since the class was conducted in a public setting, which can create a rigid environment between the teacher and students, the teacher used mood-setting strategies aligned with the lesson’s content to engage the students.

Setting nodes

Relevant psychological studies have demonstrated that the optimal level of arousal follows an inverted U-shaped curve, where motivation increases with rising stimulation but declines after reaching a peak (Yerkes and Dodson, 1908). Based on this principle, engaged teachers plan their performance according to students’ motivational tendencies. As intern teacher shared what her instructional supervisor taught her:

According to my supervisor’s recommendations, it is best to limit the introduction to five minutes, spend thirty minutes on the primary content, and reserve five minutes for an expansion.

The first and last five minutes are considered critical points in the teachers’ open class performance, during which they present the most important and challenging content within the students’ optimal arousal range.

Dressing up

The teachers who conduct the open class often dress up to enhance their presentation of open class. Some teachers apply make-up or wear attire that aligns with the lesson topic. A notable instance involved intern teacher Yi, who cut his long hair before his open class. He explained:

My instructional supervisor said that male teachers with long hair violate Sailing School discipline and set a bad example for students.

Since long hair on male teachers is generally considered immoral in Chinese society. Dressing up which not only enhance the presentation of open class, but also helps teachers avoid moral criticism and succeed during their participation.

Ending: evaluating teachers’ performance

The final phase of an open class involves evaluating teachers’ performance, a process that Chinese educators refer to as “pingke” (评课 in Chinese). “Pingke” entails the audience, consisting of observing teachers, assessing the performance of the teachers after they have completed their instruction and offering suggestions for improvement. During fieldwork, we identified three criteria that observing teachers use for evaluation. The first is the achievement of teaching goals, as teacher Zhang stated:

Evaluating teachers’ performance cannot cover all bases; the most important assessment point is whether students grasp the knowledge, as this reflects whether the teaching goals have been met.

With the current emphasis on student-centered learning, observing teachers assess the performance of participating teachers based on their students’ knowledge acquisition. In addition to achieving teaching goals, some teachers evaluate performance based on the overall presentation of instructional content. For example, teacher Cui explained:

I prefer to evaluate teachers’ performance from a holistic perspective, considering factors such as whether the class flows smoothly and how teachers use instructional language throughout the lesson.

Moreover, the application of teaching methods is a significant factor in evaluating teachers’ performance. Unlike the holistic assessment of instructional content, this evaluation focuses on specific aspects of the open class, as teacher Shi noted:

I will evaluate the performance of participating teachers in specific areas, such as their highlights or deficiencies.

Teamwork: cooperating with peers and students

The open class is not solely a personal showcase for the conducted teachers. In reality, these teachers form teams with their peers and students to ensure the success of the presentation through collaboration. While the open class is ostensibly delivered by the conducted teachers, its preparation incorporates the collective wisdom of their colleagues. As teacher Zhao mentioned in an interview:

Representing schools in the open class, each teacher in the same subject group and the instructional supervisor will work together to prepare.

Teachers often describe this collaborative effort as a “community,” emphasizing the equal contributions of each member in the preparation process. In this context, all team members contribute to the success of the open class through their assistance. Additionally, students, aware of being observed by other teachers, take responsibility for their performance by collaborating with the teacher and strive to present an idealized image. As teacher Shu noted:

Some mischievous students know they will be observed by other teachers, so they follow the discipline during the open class.

At times, this cooperation is explicitly guided by the conducting teachers to manage the inherent uncertainties and risks associated with open classes. For instance, teacher Guan shared her approach:

During an intra-school open class, I informed students in advance about the questions I would be asking and assigned specific students to answer.

Professional learning of teachers during the open class

This section identifies four ways that the open class facilitates teachers’ professional learning: enhancing instructional design during the planning stage, developing PCK in practicing, fostering pedagogical tact during the presentation, and improving theoretical skills through self-reflection.

Planning: enhancing the ability of instructional design

The first way of teachers’ professional learning is open class has enhanced teachers ability of instructional design in the planning stage. Normally, conducting teachers typically engage in extensive consultations with colleagues, during which they share experiences and provide valuable feedback. As teacher Yu noted:

For the trial lesson of the open class, different teachers [in the group] are willing to help polish the lesson based on their perspectives. They observe at least one class and often spend several more thinking about how to improve it.

This collaboration implies that teachers within the group evaluate the instruction from multiple perspectives, identifying issues in the preliminary lesson design through critical reflection. By raising concerns and offering suggestions, conducting teachers continuously refine their instructional design. For this, teacher Xie explained:

Colleagues in the group will identify problems in the instructional design, and I receive many suggestions from them, which help me refine my lesson before the open class.

Thus, collective support—through experience sharing, questioning, and constructive feedback—allows engaged teachers to recognize shortcomings in their instructional plans, motivating them to continually improve before delivering the official open class.

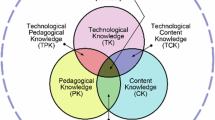

Knowledge: developing PCK in practicing

The second way teachers learnt professionally is by enhancing their Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK) (Shulman, 1986) through practice. PCK refers to the blend of content and pedagogy that enables teachers to understand how specific topics, problems, or issues are organized, represented, adapted to diverse learners’ needs, and presented for instruction (Shulman, 1986).

Conducting open classes provides an opportunity for teachers, particularly novice ones, to apply the knowledge they have acquired. For instance, teacher An, an intern at Sailing School, emphasized how open classes helped her deepen her understanding of PCK, which bridges the gap between her knowledge of music and pedagogy. She expressed gratitude for this opportunity, explaining:

I appreciate this chance. It is through my supervisor’s suggestions and evaluations that I learned how to teach music. […] I realized there is a gap between teaching practice and the theory we learned in school.

Moreover, open classes also provide an opportunity for the audience to develop their PCK. By observing, teachers can gain insights into excellent teaching designs, innovative methods, and advanced instructional ideas from exemplary teaching demonstrations. As teacher Shi explained, she benefited from observing an inter-school open class conducted by experts:

Last year, the 2022 edition of the compulsory education math curriculum standards introduced a lot of new content. Many frontline teachers had doubts about it. […] By observing the expert-led open class, we gained a better understanding of the ideas and content in the math curriculum standards.

Acting: fostering a pedagogical tact

The third way of professional learning was facilitated related to pedagogical tact in the process of acting in open class. Van Manen (2012) conceptualized pedagogical tact as a teacher’s thoughtful and responsive actions in addressing unexpected incidents in the classroom. By employing pedagogical tact, teachers can skillfully manage these incidents, turning them into beneficial educational opportunities. Open classes are fraught with uncertainties, as teacher Yu observed:

Sometimes we have never met the students in the open class, and we are unfamiliar with the teaching environment, so we don’t know what will happen […] No matter how well we prepare, our instructional design is only a framework; we cannot fully recreate the actual teaching context.

It is precisely these uncertainties that may lead teachers to encounter unforeseen challenges during open classes. Teacher Cui recounted a technical issue she faced:

In a music competition open class, my multimedia courseware malfunctioned, and the music audio wouldn’t play. In this awkward situation, I decided to sing the melody myself until the technical problem was resolved.

Her quick decision to sing in place of the audio was praised by many observing teachers, highlighting how she used her pedagogical tact to navigate the situation. This incident illustrates how teachers can handle dilemmas and technical difficulties in real time, transforming these challenges into valuable teaching moments. In subsequent interviews, teachers reached a consensus on the value of open class for their professional development, noting that it provides a genuine teaching context where they can cultivate adaptability by applying pedagogical tact when encountering unforeseen obstacles.

Theorization: improving theoretical skills through self-reflecting

After participating in open class, teachers reported significant benefits for their professional development, particularly in theoretical aspects derived from reflection. Teachers often organize their open class experiences into teaching-related research, which they disseminate through academic outputs. They view conducting such research as an essential pathway for individual and professional growth, as well as a means to meet school evaluation requirements. As Shen stated:

A higher title requires relevant academic outputs, which is the fundamental requirement for promotion. Conducting teaching-related research based on open class experience is an excellent opportunity to meet this requirement.

However, frontline teachers often face challenges in conducting academic research due to a lack of theoretical frameworks to structure their teaching experiences. To address this issue, Cui, the instructional director of Sailing School, explained:

The school regularly organizes research open classes to encourage self-reflection, and we invite scholars and experts to help teachers refine their research and articles.

With the school’s guidance and support, engaged teachers are able to reflect theoretically on their open class experiences, motivating them to conduct teaching-based research more frequently. This process of theoretical self-reflection further inspires teachers to think about how to apply their research to pedagogical practice. Through this reflection, some educators have developed the critical thinking necessary to identify the limitations of their instructional methods.

Discussion

Regarding RQ1, “How do teachers conduct the open class in China?” We examined the specific activities and processes involved. In the initial phase, teachers prepare for the presentation by selecting a script, inviting participants, and rehearsing. During the presentation, teachers employ various performance strategies, including setting the mood, identifying key moments, and dressing appropriately. In the final phase, the audience evaluates the teachers’ performance. Besides, teachers work collaboratively with peers and students, who assist in achieving the desired performance outcome.

Regarding RQ2, “What are the ways in which open class facilitates teachers’ professional learning?” Four keyways were identified: enhancing instructional design during the planning stage, developing PCK in practicing, fostering pedagogical tact during the presentation, and improving theoretical skills through self-reflection.

Open class as a platform for bridging the gap between theory and practice

The initial implication of this study highlights the role of open classes as a platform for bridging the gap between theory and practice for teachers. As Cheng et al. (2024) argued, despite extensive practical experience, many frontline teachers struggle to balance theoretical knowledge with practical application. While all teachers in this study acknowledged the importance of theory in their practice, most clearly prioritized practical experience over theoretical understanding. The findings indicate that this gap between theory and practice exists not only among pre-service teachers (Allen and Wright, 2014) but also among in-service teachers. This disconnect may be attributed to teachers’ educational beliefs (Levin and He, 2008), prior knowledge and experiences from their schooling, and the realities of teaching contexts (Hascher et al. 2004). Consequently, educators, researchers, and policymakers have explored various methods to bridge this gap for teachers.

This study presents open classes as a practical platform to address this issue. First, open classes provide frontline teachers opportunities to share teaching experiences (Wu and Clarke, 2018). Specifically, teachers in this study shared their experiences in three keyways: (i) novice teachers gained insights and skills from their mentors; (ii) experienced teachers shared their pedagogical reforms with frontline teachers; and (iii) frontline teachers exchanged suggestions and experiences with their peers. Second, Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) play a vital role in enhancing teachers’ theoretical understanding and developing their PCK (Sun et al. 2015). In this study, teachers organized their open-class experiences into action research projects within PLCs, fostering self-reflection and receiving expert guidance. Through this process, teachers not only refined their professional expertise but also engaged in practice-based research, generated evidence for their methods, and applied findings to improve their teaching (Gao et al. 2010). Thus, open classes emerge as an innovative approach to bridging the gap between theory and practice. By fostering experience-sharing and promoting the development of theoretical skills through PLCs and action research, open classes significantly contribute to teachers’ professional growth (Chen, 2022).

The shift from individualism to collectivism of teachers

Another crucial implication of this study is the shift from individualism to collectivism among teachers involved in open classes. The findings demonstrate that collective collaboration permeates the entire open-class process, often prioritizing collective goals over individual teachers’ preferences. In many Western contexts, pedagogical activities are traditionally viewed as private matters (Grierson and Gallagher, 2009). This perception stems from the belief that teaching is a personal endeavor, with teachers often reluctant to share their experiences with colleagues (Mirell and Goldin, 2015). Such perspectives are rooted in individualistic values, which prioritize autonomy and view the self as the primary unit of survival (Hui and Villareal, 1989).

However, the public nature of open classes transforms teaching from a private activity into a public one (Wu and Clarke, 2018). The findings reveal that teachers involved in open classes exhibit a strong commitment to cooperation and collaboration, shaping their practices to align with group-oriented goals. This behavior reflects Confucian cultural values, which emphasize collectivism. In Confucian-influenced societies, collectivism fosters the belief that individual success is tied to group achievements, promoting affiliative, nurturing, and supportive behaviors (Hui and Villareal, 1989). Within this cultural framework, teachers recognize the importance of collaboration (Hargreaves, 1997) and willingly engage in collective activities, even when such participation is mandated (Zhang and Pang, 2015; Wong, 2010).Thus, open classes not only foster a sense of affiliation by integrating teachers into collaborative teams with peers and students but also enhance the public nature of pedagogical practice by presenting teaching methods to a broader audience.

Conclusion

The present study investigates the process of Chinese teachers conduct the open class, aiming to elucidate how open class facilitates teachers’ professional learning. Drawing on fieldwork at Sailing School and semi-structured interviews with 19 teachers from Fujian, China, the study highlights that open class fosters a practice-based epistemology to support professional learning. It also reveals a shift from individualism to collectivism among teachers and provides valuable insights for comparing pedagogical practices across different cultures.

However, this empirical research has several significant limitations. First, educational resource distribution varies widely across China’s regions. Since only one school was used as a research site, the findings cannot be generalized to other schools or regions. Additionally, the study only included teachers of core subjects. Future research should explore the professional learning experiences of teachers from other subject areas. Finally, although the researchers participated in the full open class process with some conducted teachers, they were not permitted to attend certain core seminars related to open class preparation.

Data availability

Data sharing in not applicable to this research as the data involved participants’ personal information.

References

Allen JM, Wright SE (2014) Integrating theory and practice in the pre-service teacher education practicum. Teach. Teach. 20(2):136–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2013.848568

An F (2013) Revisiting in open class issues. J. Chin. Soc. Educ. No.241(05), 52–55

Avidov-Ungar O (2016) A model of professional learning: Teachers’ perceptions of their professional learning. Teach. Teach. 22(6):653–669. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1158955

Ball DL, Lubienski S, Mewborn D (2001) Research on teaching mathematics: The unsolved problem of teachers’ mathematical knowledge. In Richardson V. (ed.), Handbook of research on teaching, 4th ed. Macmillan, pp 433–456

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualit. Res. Psychol. 3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun V, Clarke, V (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage

Brodie K (2021) Teacher agency in professional learning communities. Prof Dev Educ 47(4):560–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2019.1689523

Cameron S, Mulholland J, Branson C (2013) Professional learning in the lives of teachers: Towards a new framework for conceptualising teacher learning. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 41(4):377–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866x.2013.838620

Chen L (2022) Facilitating teacher learning in professional learning communities through action research: A qualitative case study in China. Teach. Teach. Educ. 119:103875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103875

Cheng C, Diao Y, Wang X, Zhou W (2024) Withdrawing from involution: The “lying flat” phenomenon of music teachers in China. Teach. Teach. Educ. 147:104651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2024.104651

Chong WH, Kong CA (2012) Teacher collaborative learning and teacher self-efficacy: The case of lesson study. J. Exp. Educ. 80(3):263–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2011.596854

Cordingley P, Bell M, Evans D, Firth A (2005) The impact of collaborative CPD on classroom teaching and learning review: How do collaborative and sustained CPD and sustained but not collaborative CPD affect teaching and learning? EPPI-Centre

Creswell JW, Creswell JD (2022) Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed method approaches (6th ed.). Sage

Creswell JW, Poth CN (2024) Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions (5th ed.). Sage

Flick U (2018) Doing triangulation and mixed methods. Sage

Fullan M, Hargreaves A (2012) Reviving teaching with ‘professional capital’. Education week, 31(33), 30–36. https://michaelfullan.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/13438456970.pdf

Gao X, Barkhuizen G, Chow A (2010) ‘nowadays, teachers are relatively obedient’: Understanding primary school English teachers’ conceptions of and drives for research in China. Lang. Teach. Res. 15(1):61–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168810383344

Garet MS, Porter AC, Desimone L, Birman BF, Yoon KS (2001) What makes professional development effective? Results from a national sample of teachers. Am. Educ. Res. J. 38(4):915–945. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312038004915

Glaser B (1992) Basics of Grounded Theory: Emergence vs Forcing. Sociology Press, Mill Valley, CA

Goddard R. D. (2003). The impact of schools on teacher beliefs, influence, and student achievement: The role of collective efficacy beliefs. In Raths J., McAninch A. C. (eds), Teacher beliefs and classroom performance: The impact of teacher education, volume 6: Advances in teacher education, Information Age pp 183–202

Grierson AL, Gallagher TL (2009) Seeing is believing: Creating a catalyst for teacher change through a demonstration classroom professional learning initiative. Profess. Learn. Educ. 35(4):567–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415250902930726

Hargreaves A (1997) Cultures of teaching and educational change. International Handbook of Teachers and Teaching, 1297–1319. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-4942-6_31

Hascher T, Cocard Y, Moser P (2004) Forget about theory—practice is all? Student teachers’ learning in practicum. Teach. Teach. 10(6):623–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354060042000304800

Hui CH, Villareal MJ (1989) Individualism-collectivism and pyschological needs: Their relationships in two cultures. J Cross-Cultural Psychol. 20(3):310–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022189203005

Insulander E, Brehmer D, Ryve A (2019) Teacher agency in professional learning programmes – A case study of professional learning material and collegial discussion. Learn., Cult. Soc. Interact. 23:100330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2019.100330

Kirkwood M, Christie D (2006) The role of teacher research in continuing professional learning. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 54(4):429–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8527.2006.00355.x

Levin B, He Y (2008) Investigating the content and sources of teacher candidates’ personal practical theories (PPTs). J. Teach. Educ. 59(1):55–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487107310749. Jan

Lewis CC, Perry RR, Friedkin S, Roth JR (2012) Improving teaching does improve teachers. J. Teach. Educ. 63(5):368–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487112446633

de Macedo AD, Baltar Bellemain PM, Winsløw C (2019) Lesson study with didactical engineering for student teachers in Brazil. Int. J. Lesson Learn. Stud. 9(2):127–138. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijlls-03-2019-0027

Manen VM (2012) The tact of teaching: The meaning of pedagogical thoughtfulness. Althouse Press

McCray C (2018) Secondary teachers’ perceptions of professional learning: A report of a research study undertaken in the USA. Profess. Learn. Educ. 44(4):583–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2018.1427133

Miles MB, Huberman AM (1994) Qualitative Data Analysis: A Source of New Methods, 2nd ed. Newbury Park, CA; Sage, p28

Mirell J Goldin S (2015) Alone in the classroom: Why teachers are too isolated. The Atlantic. Retrieved April 24, 2023, from https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2012/04/alone-in-the-classroom-why-teachers-are-too-isolated/255976/

Morcom V, MacCallum J (2022) Mentoring experienced teachers to change their practice: A sociocultural perspective for professional learning and development. Learn., Cult. Soc. Interact. 34:100627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2022.100627

Opfer VD, Pedder D (2011) The lost promise of teacher professional learning in England. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 34(1):3–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2010.534131

Paine L, Ma L (1993) Teachers working together: A dialogue on organizational and cultural perspectives of Chinese teachers. Int. J. Educ. Res. 19(8):675–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-0355(93)90009-9

Patton MQ (2015) Qualitative Evaluation and Research Method, 4th ed. London: Sage

Peter D (2015) Lesson Study: Professional Learning for Our Time. Routledge, New York

Polit DF, Beck CT (2010) Generalization in quantitative and qualitative research: Myths and strategies. Int J Nursing Stud 47(11):1451–1458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.06.004

Prestridge S (2019) Categorising teachers' use of social media for their professional learning: A self-generating professional learning paradigm. Comput. educ. 129:143–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.11.003

Rappleye J, Komatsu H (2017) How to make lesson study work in America and worldwide: A Japanese perspective on the onto-cultural basis of (teacher) education. Res. Comp. Int. Educ. 12(4):398–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745499917740656

Raths J (2001) Teachers’ beliefs and teaching beliefs. Early Childhood Research & Practice, 3(1). http://ecrp.uiuc.edu/v3n1/raths.html

Richardson V. (1996). The role of attitudes and beliefs in learning to teach. In Sikula J. (ed.) Handbook of research on teacher education, 2nd ed. Macmillan, pp 102–119

Ross D, Adams A, Bondy E, Dana N, Dodman S, Swain C (2011) Preparing teacher leaders: Perceptions of the impact of a cohort-based, job embedded, blended teacher leadership program. Teach. Teach. Educ. 27(8):1213–1222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.06.005

Sampson R. J, Morenoff J. D, Earls F (1999) Beyond social capital: Spatial dynamics of collective efficacy for children. Am. Sociol. Rev. 64:633–660. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312249906400501

Sargent T. C (2015) Professional learning communities and the diffusion of pedagogical innovation in the Chinese education system. Com. Educ. Rev. 59(1):102–132. https://doi.org/10.1086/678358

Seale C (1999) The quality of qualitative research. Sage

Seleznyov S (2018) Lesson study: An exploration of its translation beyond Japan. Int. J. Lesson Learn. Stud. 7(3):217–229. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijlls-04-2018-0020

Seleznyov S (2019) Lesson study: Exploring implementation challenges in England. Int. J. Lesson Learn. Stud. 9(2):179–192. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijlls-08-2019-0059

Shulman L. S (1986) Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educ. Res. 15(2):4–14. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X015002004

Song L (2011) Tracing the lost ethics in open class. Theory Pract. Educ. 31(17):43–44

Starkey L, Yates A, Meyer LH, Hall C, Taylor M, Stevens S, Toia R (2009) Professional learning design: Embedding educational reform in New Zealand. Teach. Teach. Educ. 25(1):181–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.08.007

Stenberg K, Maaranen K (2021) A novice teachers teacher identity construction during the first year of teaching: A case study from a dialogical self perspective. Learn., Cult. Soc. Interact. 28:100479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2020.100479

Stigler JW, Hiebert J (1999) The teaching gap: Best ideas from the world’s teachers for improving in the classroom. The Free Press, New York

Sun XH, Teo T, Chan TC (2015) Application of the open-class approach to pre-service teacher training in Macao: A qualitative assessment. Res. Pap. Educ. 30(5):567–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2014.1002525

Timperley H (2011) Knowledge and the leadership of learning. Leadersh Policy Sch 10(2):145–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2011.557519

Vasalampi K, Metsäpelto R-L, Salminen J, Lerkkanen M-K, Mäensivu M, Poikkeus A-M (2021) Promotion of school engagement through dialogic teaching practices in the context of a teacher professional learning programme. Learn., Cult. Soc. Interact. 30:100538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2021.100538

Wong JLN (2010) Searching for good practice in teaching: A comparison of two subject‐based Professional Learning Communities in a secondary school in Shanghai. Comp.: A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 40(5):623–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920903553308

Wu H, Clarke A (2018) The Chinese “Open class”: A conceptual rendering and historical account. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 38(2):214–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2018.1460260

Yerkes RM, Dodson JD (1908) The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit formation. J. Comp. Neurol. Psychol. 18:459–482. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.920180503

Yin R. K (2017) Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th ed.). Sage

Yoshida N, Matsuda M, Miyamoto Y (2021) Intercultural Collaborative Lesson Study between Japan and Germany. Int. J. Lesson Learn. Stud. 10(3):245–259. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijlls-07-2020-0045

Zhang J, Pang NS-K (2015) Exploring the characteristics of Professional Learning Communities in China: A mixed-method study. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 25(1):11–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-015-0228-3

Zhang XF, Ng HM (2011) A case study of teacher appraisal in Shanghai, China: In relation to Teacher Professional learning. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 12(4):569–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-011-9159-8

Zhang C (2012) A study on the types of open class in elementary and secondary schools of China. Thesis for master’s degree, East China Normal University

Zhang L-X, Leung B-W, Yang Y (2022) From theory to practice: Student-centered pedagogical implementation in primary music demonstration lessons in Guangdong, China. Int. J. Music Educ., 025576142211071. https://doi.org/10.1177/02557614221107170

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jinxiu Wu contributed to the article writing & editing, data analysis, and conceptualization. Ping Shen contributed to the research design, data collection, data analysis, conceptualization, and paper writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the principle of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study commenced on 3rd September 2022, approval was granted by the School of Graduate Studies, Sahmyook University, under approval number SYU20220610001, data of approvals: 10th June 2022. Moreover, all participants signed an informed consent form before the study, and their personal information and data were anonymized.

Informed consent

Before the data collection (from 3rd September 2022 to 10th September 2022), all participants were informed of the purpose and scope of the study and how the data would be used. They all signed the informed consent and agreed to participate in this research, data use, and consent to publish. Moreover, all participants were also assured that their anonymity would be maintained and that no personal or identification information would be disclosed.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, J., Shen, P. Facilitating teachers’ professional learning in open class: a qualitative case study in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1752 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04348-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04348-9

This article is cited by

-

Unpacking Chinese teacher job satisfaction: multilevel mediation and moderation of collaborative professional learning, efficacy, and innovation support

Large-scale Assessments in Education (2026)