Abstract

Sentencing disparity dominates in American scholarship and has been leading global research in past decades, however, few studies have addressed sentencing equilibrium across countries. Learning from the previous theories regarding court communities, organizational conformity, and so on, this paper develops a theory of jurisdictional uniformity to address sentencing equilibrium in embedded courts across different levels in China. With data on sentence length consisting of 15,142 rape offenders nationwide, this article conducts bivariate and multilevel multivariate analyses to demonstrate negligible sentencing differences across cities and provinces. Authors believe the sentencing rules under jurisdictional uniformity pave the way for balanced sentencing, while the political mechanism in the judicial system controls jurisdictional disparity. Given that the existence of sentencing disparity should be seriously rechecked in each jurisdiction due to the legal and political diversity across the country, attention should be given to sentencing equilibrium inside the embedded court.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sentencing disparity and sentencing equilibrium have been contentious issues in penal philosophy over decades. The existence of sentencing disparity as a result of discretional inequality, discrimination, nuisance, and disease has faced skepticism due to inconsistent findings and insufficient evidence (Baumer, 2013; Thomson and Zingraff, 1981). On the one hand, scholars have highlighted the disparity as a lack of clear consensus (Zane and Pupo, 2022), messy results (Engen, 2011), speculative enterprise (Johnson and Dipietro, 2012), and battle cry (Hofer, 2012; Stith and Cabranes, 1998). On the other hand, conclusions on sentencing disparity have also been criticized for methodological defaults (Forst, 1982; Lynch, 2019; Mitchell, 2005), being outcomes of methodological factors (Wilbanks, 1987) and research design (Wei and Xiong, 2020). In addition, theories of sentencing disparity have been described as purely academic interests rather than representing real justice (Wilbanks, 1987), largely decoupled from the origins of sentencing theory (Lynch, 2019). By contrast with the disparity-triggered theories and findings, the existing literature revealed the potential but overlooked possibility of sentencing equilibrium. Hester (2017, p. 208) noticed this point very well and commented thus, “The courts as communities perspective is focused on explaining variation, the potential for more uniform statewide culture and norms has been overlooked.”

While mixed findings and theoretical divergences of sentencing largely focus on the US (Ulmer, 2014), some evidence from other countries has revealed obvious or implicit evidence of a sentencing equilibrium (Albrecht, 2013; Casey and Wilson, 1998; Frisch, 2017; Pina-Sanchez and Linacre, 2013; Roberts and Ashworth, 2016; Wei and Xiong, 2020; Xia et al., 2019; Xiong et al., 2021). Nevertheless, existing literature has failed to offer a convincing theory accompanied by empirical evidence that can decipher the reasons underlying sentencing without disparity. In this article, we explore the sentence lengths of rape cases in China, with the aim of offering meaningful theoretical and empirical findings regarding sentencing philosophy for international communities and meeting the “need for more international research” noted by Ulmer (2014, p. 4766).

Sentencing disparity, consisting of in/out (i.e., whether incarceration or not) decisions and sentence length (in a unit of month or year), has been widely explored in previous studies, but there is little agreement regarding these findings among theorists. Research on demographic disparities in offender level largely focuses on extra-legal factors, with less attention paid to legal factors and circumstances (Bontrager et al., 2013; Daly and Bordt, 1995; Hagan and Bumiller, 1983; Kim et al., 2019; King and Light, 2019; Mitchell, 2005; Pratt, 1998; Spohn, 2000; Ulmer, 2012; Zane and Pupo, 2022). By contrast, in terms of disparities at the court/district level, some research into federal districts has revealed no difference or an explainable difference regarding legal and judicial factors (Crow and Goulette, 2021; Farrell et al., 2010; Freed, 2003; Hartley and Tillyer, 2019; Hester, 2017; Hester and Sevigny, 2016; Yang, 2015; Ulmer and Johnson, 2017).

In recent years, with the development of statistical techniques such as hierarchical linear models and multilevel analysis, there has been more research exploring sentencing outcomes in legal and extralegal contexts concerning offenders and judges nested in courts (Lynch, 2019; Ulmer, 2012; Ulmer and Johnson, 2017). Nevertheless, the methodology of multilevel analysis has not been effectively applied in inter and intra contexts across districts, courts, and jurisdictions. Studies employing multilevel analytical strategies have not clearly reported descriptive and inferential sentencing outcomes at the individual level, nor have they explained fixed and random effects clustered in courts (Farrell et al., 2010; Johnson, 2006; Kim et al., 2019; Ulmer and Johnson, 2004; Wang and Mears, 2010; Ward et al., 2009).

The demographical factors triggered disparity overstated the role of extralegal factors, being far away from legal factors as an achievement of sociologists and criminologists. Despite advanced methodologies applied and updated in the past decades, the theoretical fundamental and core argument of sentencing disparity still overdoses on the extralegal decisional mechanism. On the three theoretical approaches to examine sentencing outcomes in court, nevertheless, Dixon (1995, p. 1157) addressed that sentencing is determined and predicted by legal factors under the formal legal theory, legal and social status variables under the substantive political theory, and legal and processing variables under the organizational maintenance theory. Thus, it is clear that legal factors should be the center of studying a judge’s decisions in the organizational context rather than a sole decision by the judge himself.

Alternatively, all the court-centered theories indicated, including the court community theory (Eisenstein et al., 1988; Flemming et al., 1992; Nardulli et al., 1988), the organizational conformity theory (Dixon, 1995; Ulmer and Johnson, 2017), and the inhabited institutions theory (Ulmer, 2019), that sentencing should be understood in the top-down structure of court and its organizational participants. As Ulmer (2019, p. 509) highlighted, “We need more qualitative and multimethod research that can flesh out the inhabited institutions we study—courts. We would do well to emulate the organizational sociology literature both methodologically and theoretically”. Nevertheless, his long list of publications produces more sentencing disparity than conformity (Ulmer, 1995; Ulmer and Kramer, 1996, 1998; Ulmer and John, 2004, 2017), Ulmer (2019, p. 483) appraised that “variation between courts in sentencing practices should be understood not as a nuisance in the top-down imposition of sentencing policies, a valuable but underappreciated source of policy feedback and learning.” Although he would not like to deny the existence of sentence disparity, he admitted the existence of sentencing conformity under organizational conformity and court communities. The only thing left to scholars and practice is “making sense of difference and similarity in sentencing” (Ulmer, 2019, p. 483), but how to make sense of it is not clear so far through many academic interpretations and comments.

While previous sentencing research has focused on explaining disparities, the field’s theoretical and empirical developments also provide the foundation for examining sentencing uniformity (Hester, 2017; Lynch, 2019; Mitchell, 2005; Ulmer, 2019). To solve the theoretical divergence and empirical contradictions in sentencing research, it is time to recheck sentencing decisions carefully with intranational and international perspectives. For one thing, not only a bunch of literature in the US revealed theories and findings to imply the appropriate negligible difference among courts (Nowacki, 2020; Hester, 2017; Hester and Sevigny, 2016), but also the previous findings about sentencing disparity are inconsistent in many ways (Lynch, 2019; Mitchell, 2005; Ulmer, 2012). For another thing, a difference in criminal law or penal code, sentencing guidelines, legal culture, political structure, and social system cannot be ignored in different countries, and thus, it calls for in-depth evidence to recheck the persuasive instigation of sentencing disparity across countries (Wei and Xiong, 2020; Xiong et al., 2021).

Given the fact that “the contemporary literature continues to lack sustained attention to and understanding of how organizational mechanisms play out in court communities and their workgroups” (Ulmer, 2019, p. 511) and “discussion of sentencing guidelines conformity and deviation illustrates how a focus on organizational mechanisms of isomorphism and variation can lead to useful new research” (Ulmer, 2019, p. 512), this article would pay attention to judge’s sentence decision in the court levels to reobserve the organizational sentencing decision in the legal and political approaches. Thus, this article focuses on sentence length in rape cases nationwide and related factors across different clustered levels to explain the sentencing equilibrium in China. This article contributes to the existing literature in four aspects: (a) it offers a theory of jurisdictional uniformity to explain sentencing equilibrium, which can be applied both in China and internationally; (b) it offers a standard, step-by-step, multilevel methodology through which to explore sentencing similarity, from the individual level of judges and offenders to the clustered level of embedded courts; (c) it highlights the role of legal factors, returning sentencing research to its legal and judicial foundations; and (d) it calls for attention to be focused on legal and political regimes in local justice.

The paper proceeds by reviewing theories on sentencing disparity and equilibrium, presenting our theoretical framework, describing our data and methods, demonstrating sentencing equilibrium in China, and discussing implications for future research. Throughout, we argue for reconsidering the presumption of sentencing disparity in favor of context-specific approaches to studying sentencing practices.

Literature review

Existing theories

Previous review articles have identified numerous theories about sentencing disparity and potential elements of sentencing equilibrium (Baumer, 2013; Daly and Bordt, 1995; Hagan and Bumiller, 1983; Mitchell, 2005; Spohn, 2000; Ulmer, 2012, 2019; Zatz, 2000). Despite extensive research exploring sentencing disparity from various perspectives, the question is that the theoretical approach and empirical findings are “insufficient for addressing the key underlying questions that motivate this work, including whether, where, how, and why” (Baumer, 2013, p. 231) and “how these disparities come about as most of the sentencing research has relied on quantitative designs focused on documenting the problem” (Veiga et al., 2023, p. 167). By contrast, some research explored the theoretical implications and extensions of sentencing similarities. However, they still failed to know why and how sentencing similarities should be the organizational truth of sentencing justice as a result of legal and political context. By reviewing the existing theories and empirical findings, we argue that more academic attention should be devoted to exploring the theoretical implications of sentencing equilibrium.

First, disparity theory provides several insights into the cause of sentencing disparity across multiple studies. Discrimination theories explain sentencing disparities between majority groups (e.g., white individuals) and minority groups (e.g., black individuals), with some anti-discriminate theories challenging the idea that minorities receive harsher sentences compared to the majority (Franklin and Henry, 2020; Farrell et al., 2010; Gabbidon et al., 2014; Kingsnorth et al., 1998; Thomson and Zingraff, 1981; Zatz, 2000). Sexism theory, with concepts such as “male chivalry lenience” and “evil women,” suggests that male judges tend to issue lenient sentences to female offenders, whereas female judges tend to be harsher toward male offenders (Gruhl et al., 1981; Johnson, 2006; Steffensmeier and Herbert, 1999). Feminist theory, which includes concepts such as “different voices,” “representation,” and “informational features,” emphasizes that female judges issue distinct sentences to female offenders compared to those issued by male judges (Boyd et al., 2010). Nevertheless, the gender effects of offenders and judges and the interactive effect stemming from both sexism and feminism have produced inconsistent findings and lack methodological rigor (Wei and Xiong, 2020; Xia et al., 2019; Bontrager et al., 2013; Nowacki, 2020; Zatz, 2000).

Second, while disparity theory focuses on sentencing differences, equilibrium theory explores the factors contributing to consistency in sentencing outcomes, incorporating both legal and extralegal influences. This theoretical approach includes several interconnected perspectives. Organizational theory has acknowledged that professionals who undergo identical training and obtain jobs through the same procedures are faced with similar constraints on the bench, which contributes to similar or identical sentencing (Boyd et al., 2010; Dixon, 1995; Zatz, 2000). Contextual theories expand on this idea by considering the broader environment in which judges operate, arguing that judges are significantly influenced by the characteristics of their courts, prevailing judicial cultures, and the social community they inhabit, leading to comparable sentencing outcomes among judges working with similar contexts (Haynes et al., 2010; Hester and Sevigny, 2016; Lynch, 2019; Johnson, 2006; Ulmer, 2019; Ulmer and Johnson, 2004, 2017; Ulmer and Kramer, 1996, 1998). Notably, although court communities, court context, and organizational theory have already well explained the potential mechanism of sentencing equilibrium, these theories did not really appreciate the sentence without disparity but “highlighted how local differences emerge based on informal sociological and political processes defined by the communities’ perspective” (Hester, 2017, p. 205). Thus, Hester (2017) and colleagues (Hester and Sevigny, 2016) used legal culture and sentencing structure under court context and community perspective to explain the small level of variation and relative uniformity in South Carolina.

Third, some theoretical frameworks attempt to bridge these perspectives, offering explanations for both sentencing disparity and consistencies. These approaches recognize the complex interplay of factors influencing judicial decisions. Focal point theories, for instance, address demographic disparities at the individual level, proposing that judges, faced with limited information, rely on subjective “perceptual shorthand” when considering offenders (Albonetti, 1991; Engen et al., 2003; Hartley, 2014; Steffensmeier et al., 1993, 1998). Complementing this individual-focused view, courtroom workgroup theory has tried to reveal that sentencing outcomes are a collaborative process; they are decisions made by judges with the participation of prosecutors and defense attorneys. Although numerous studies have found that judges’ sentencing decisions maintain an equilibrium most of the time, research has overstated judges’ discretional disparity (Haynes et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2015; Ulmer, 2019; Ward et al., 2009). This deprotonates focus on disparity, as Lynch (2019, p. 1156) argues, may undermine “the knowledge-production value of the empirical exercise.”

Empirical findings

US scholarship on sentencing disparity provides insufficient evidence of its existence, with research often reflecting methodological differences rather than actual disparities. While inter-jurisdictional variations are attributed to differing criminal laws (Tonry, 2016; Ulmer, 2014), intra-jurisdictional disparities are linked to sentencing ranges and judicial discretion (Baumer, 2013; Kim et al., 2015). Many studies focusing on offender characteristics via regression models neglect crucial legal and court factors (Johnson, 2006; Ulmer and Johnson, 2004). Methodological issues, including misuse of statistics, have led to misleading conclusions about gender and racial disparities (Boyd et al., 2010; Ulmer et al., 2011).

The field is characterized by what Hofer (2012, p. 39) terms “disparity on data” or what Divine (2018, p. 771) calls “data-driven sentencing,” with conclusions often dictated by data sources. Major databases like State Court Processing Statistics and Sentencing Commission Data have acknowledged limitations, rendering them unreliable for comprehensive evaluations (Hofer, 2012; Ulmer et al., 2011). Notably, studies using advanced multivariate analyses on federal or national datasets tend to find more sentencing equality than those focused on individual states (Hartley and Tillyer, 2019; Hester and Sevigny, 2016; Nowacki, 2020).

International sentencing research reveals a complex landscape of differences and similarities with US practices. While many studies in Asia (Lin et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2011; Watamura et al., 2022) and Europe (Drápal, 2020; Herz, 2020; Junger-Tas, 1995; Philippe, 2020; Tonry and Frase, 2001; Volkov, 2016; Vuletic and Tomicic, 2017) conclude sentencing disparities exist, empirical evidence often demonstrates sentencing equilibrium. Research in the Czech Republic (Drápal, 2020) and France (Philippe, 2020) shows minimal differences despite conclusions of disparity. Qualitative studies support sentencing stability in Germany (Albrecht, 2013; Frisch, 2017; Weigend, 2016), Finland, and the Netherlands (Junger-Tas, 1995; Tonry and Frase, 2001), and Poland (Mamak et al., 2022). Japanese research suggests homogeneous judicial decisions even without sentencing guidelines (Watamura et al., 2022).

Methodological issues, particularly misuse of regression models, plague many transnational studies (Lee et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2022; Philippe, 2020; Shi and Lao, 2022; Volkov, 2016). In China, conflicting findings on racial disparities (Hou and Truex, 2022; Li et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2022; Peng and Cheng, 2022) and gender disparities (Li et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2013; Wei and Xiong, 2020; Xia et al., 2019) highlight research design problems. However, several studies report negligible differences across courts and judges (Wei and Xiong, 2020; Xiong et al., 2014, 2021).

This international perspective underscores the need for rigorous methodologies and context-specific interpretations in sentencing research, challenging the presumption of widespread sentencing disparities. It highlights the importance of considering local legal and cultural contexts in understanding judicial decision-making patterns. As research in this field continues to evolve, it becomes increasingly clear that simplistic assumptions about sentencing disparities may not capture the complex realities of judicial practices across different jurisdictions.

The China case

Contextual equilibrium features in sentencing research in China have been recognized as vital evidence in three respects in terms of supporting the theoretical framework. In terms of ethnicity, research on whether minorities receive discriminative sentences has reached different conclusions. In contrast with Hou and Truex’s (2022) artificial difference, Peng and Cheng (2022) found that minorities accused of theft indeed enjoy preferential sentencing treatment, while Li et al. (2018) and Lin et al. (2022) revealed that ethnicity had no influence on sentencing across crimes, from imprisonment to the death penalty. In gender studies, research on offenders’ and judges’ gender has revealed no disparity between male and female offenders and judges across crimes (Li et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2013; Wei and Xiong, 2020; Xia et al., 2019). At the court level, research in the context of district courts, focusing on both city intermediate courts and provincial higher courts across crimes (including rape), revealed no or negligible differences (Wei and Xiong, 2020; Xiong et al., 2014, 2021).

Theoretical implications regarding sentencing equilibrium in China have been identified but need to be examined from evidential and methodological perspectives. Wei and Xiong (2020, p. 242) have addressed the judicial mechanisms “designed to standardize judicial decisions” and stated, “judges must apply the law strictly and without variation”, but their arguments focus on judges’ gender across crimes in two cities. Xiong et al. (2021) further developed the theory of uniform legal and political systems to explain sentencing equilibrium in rape cases in China, but their data were collected from only eight provinces without consideration of nationwide sentencing. Methodologically, previous studies on sentencing in China have been dominated by research conducted at the offender and judge levels with data from local courts (Lin et al., 2022; Lu et al., 2013; Wei and Xiong, 2020). Though national and provincial data have been utilized (Xia et al., 2019; Xiong et al, 2021), court-level considerations across countries have yet to be undertaken. By contrast, this article contributes to sentencing research in theory and methodology.

To sum up, the current state of sentencing literature, particularly in the United States, reveals significant limitations that hinder a comprehensive understanding of sentencing practices. Researchers have disproportionately focused on sentencing disparities, potentially overlooking the existence of sentencing consistencies (Lynch, 2019). This bias has led to an incomplete picture of how judges and courts actually operate.

Moreover, the field has been plagued by methodological inconsistencies, with theoretical extensions and empirical findings regarding sentencing disparity remaining “inadequately tested” (Lynch, 2019, p. 1148). Multiple meta-analyses and review articles have cast doubt on the specific existence and extent of these disparities (Baumer, 2013; Ulmer, 2012, 2019), further highlighting the need for more rigorous and consistent research approaches in this area.

A critical issue in the existing literature is the tendency of criminologists and sociologists to rely heavily on non-legal theories to explain sentencing, thereby undervaluing the role of legal and jurisdictional mechanisms. This approach fails to fully appreciate the impact of formal legal structures on sentencing outcomes (Dixon, 1995; Eisenstein et al., 1988; Flemming et al., 1992; Nardulli et al., 1988; Ulmer, 2019). While theories like court communities and legal culture have provided valuable insights, they often overstate differences between courts and underestimate the potential for sentencing similarity or conformity (Hester, 2017; Hester and Sevigny, 2016; Ulmer and Johnson, 2017). Furthermore, much of the existing research is based on the US legal system, neglecting the unique legal and political mechanisms that may influence sentencing in other jurisdictions (Wei and Xiong, 2020; Xiong et al., 2021).

Theoretical framework

Jurisdictional uniformity theory

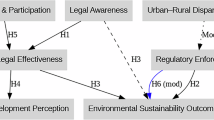

To address the limitations in current sentencing literature, we propose a theory of sentencing equilibrium, termed “Jurisdictional Uniformity Theory” (hereafter JUT). While this theoretical framework offers a fresh perspective on sentencing practices, it’s important to note that it is not entirely new. Rather, it builds upon and synthesizes previous findings and clues of jurisdictional uniformity observed in both China and the US, particularly within the organizational and contextualized perspective of courtrooms and communities (Ulmer, 2019, p. 511).

The JUT posits that in many jurisdictions, particularly those with strong centralized legal systems, sentencing outcomes may exhibit high levels of consistency across judges and courts (Wei and Xiong, 2020; Xiong et al., 2014). This consistency is primarily driven by legal and organizational factors, including uniform criminal laws, sentencing guidelines, and standardized judicial training (Eisenstein et al., 1988; Flemming et al., 1992; Nardulli et al., 1988; Ulmer, 2019).

Drawing on the concept of institutional isomorphism, the JUT suggests that courts and judges, as “inhabited institutions,” tend towards conformity due to formal and informal mechanisms within the legal system (Ulmer, 2019). While some variation may exist, differences in sentencing outcomes between judges or courts are often negligible when controlling for relevant legal factors (Wei and Xiong, 2020; Xia et al., 2019). However, the degree of sentencing equilibrium may vary between jurisdictions based on their specific legal and political structures (Hester, 2017; Xiong et al., 2021).

Our focus shifts from disparity, difference, variation, and deviance to negligible differences, similarity, conformity, and uniformity among courts. We propose that these similarities are outcomes of sentencing equilibrium at the judge and court level, particularly within top-down court structures where judges may achieve similar sentencing lengths with negligible differences. The JUT emphasizes the need to understand sentencing practices within the context of each jurisdiction’s unique legal and political framework rather than assuming disparity as the default condition (Ulmer, 2019; Xiong et al., 2021). However, it’s important to note that the degree of sentencing equilibrium may vary between jurisdictions based on their specific legal and political structures (Hester, 2017; Xiong et al., 2021). This acknowledgment aligns with Ulmer’s (2019, pp. 494–495) assertion that “conformity and deviance are neither inherently positive nor negative, functional nor dysfunctional” in the context of sentencing outcomes.

While further research is needed to test this theory across different crime types and jurisdictions, preliminary evidence, particularly from studies in China, suggests that sentencing equilibrium may be more common than previously recognized in the literature. Our previous research has consistently revealed negligible differences at both judge and court levels, challenging the notion of significant sentencing disparities. Studies examining various crime types, including theft, robbery, and rape, across different regions and involving thousands of cases found no substantial sentencing variations based on judge gender (Wei and Xiong, 2020; Xia et al., 2019) or court location (Xiong et al., 2014, Xiong et al., 2021). We attribute this sentencing equilibrium to China’s uniform legal and political systems, including standardized criminal laws, sentencing guidelines, and mechanisms such as the “iron triangle” collaboration and sentencing committees. However, these earlier studies did not develop a comprehensive JUT. The current study aims to synthesize these mechanisms and develop this theory using national data, allowing for a more comprehensive multilevel analysis of sentencing practices across China.

By shifting focus towards understanding the mechanisms that promote sentencing consistency, researchers and policymakers can gain a more nuanced and accurate understanding of sentencing practices across different legal systems. In essence, the JUT represents not a wholly new call but rather a synthesis and extension of existing insights, offering a fresh lens through which to examine and understand sentencing practices in various jurisdictions. Theoretically, jurisdictional uniformity in legal politics warrants sentencing equilibrium, while the political mechanism of court and judge in sentencing control discretional disparity. Our main theoretical contributions not only offer a further chance to critically examine the previous explorations of uniform legal and political systems in China via a nationwide dataset (Xiong et al., 2021), but also explore how jurisdictional uniformity from the perspective of legal and judicial politics achieves sentencing similarity and controls sentencing disparity, as revealed by Ulmer (2019).

Methodologically, we contribute to explaining sentencing from factors at the individual level to organizational indicators at the court level. While some studies have utilized multilevel strategies to analyze judges’ sentencing on a nested court level, empiricists remain concentrated primarily on explanations of the extralegal factors (Johnson, 2006; Kim et al., 2019; Ulmer and Johnson, 2004; Wang and Mears, 2010). In contrast with coefficient explanations of factors at the individual level or in regard to nested courts, we concentrate on the intraclass correlation (ICC) of nested courts across different levels to assess the spatial differences among cities and provinces.

Again, we emphasize here that our project follows the theoretical paths and methodological warning established in existing literature (Dixon, 1995; Eisenstein et al., 1988; Flemming et al., 1992; Nardulli et al., 1988; Ulmer, 2019; Ulmer and Johnson, 2017). Our contribution lies in providing evidence from China to support that sentencing equilibrium without disparity is really exited in some of the jurisdictions and achievable if the legal and political mechanisms offer a chance to determine sentence. In this vein, the primary value of this article is to encourage a serious approach to understanding local sentencing practice in the context of the international community.

Understandings of sentencing in China must be contextualized by criminal law on crime and punishment in the legal and judicial system—“understanding similarities and differences between courts and their practices,” as Ulmer (2019, p. 509) indicated. Although some contextual information regarding the court structure and sentencing law in China has been introduced in previous research (Lu and Kelly, 2008; Wei and Xiong, 2020; Xia et al., 2019; Yu and Sun, 2022), sentencing politics in the legal and judicial system that led to sentencing equilibrium have not been systematically reviewed. Theoretical constructions and empirical scholarship on sentencing research in China should be grounded in the jurisdictional uniformity in the legal and judicial system.

Sentencing rules under jurisdictional uniformity

Jurisdictional uniformity in mainland China warrants similar sentences nationwide. In contrast with federal and assembly countries, basically, everything about the legal and justice system in mainland China operates under the same jurisdictional uniformity.

First, multiple circumstances for sentencing are regulated by the general provisions of the Criminal Law of People’s Republic China (hereinafter, the CL), while specific rules for given crimes list some aggravated and mitigating circumstances. Given the simultaneous simplicity and abstraction of the law, numerous judicial interpretations promulgated by the Supreme People’s Court (hereinafter, the SPC) and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate detail further circumstances of sentencing in accordance with the CL.

Second, the CL and judicial files have constructed a transparent sentencing structure of judicial discretion for rape sentences. Although multiple judicial interpretations regarding the conviction and sentencing of rape have been promulgated (Hu et al., 2017), Article 236 of the CL stipulates three fundamental types of sentencing rules (see Table 1). The first rule for general rape sets up a sentence ranging from three to 10 years of imprisonment. The second rule regulates a more severe punishment for raping a girl under the age of 14 years. The third rule concerns aggravated rape and sets out six circumstances regulating the sentence range from fixed imprisonment with no less than 10 years (and a maximum of 15 years), to life imprisonment, to the death penalty. Given the mandated three-year threshold in Article 236, few rape offenders in China are sentenced to probation.

Third, the CL authorizes discretion with a range from three to 10 years for general rape, but the SPC’s sentencing guidelines (2013, 2017) shorten the sentencing range to 3–6 years for raping a woman and 4–7 years for raping a girl under the age of 14 years (see Table 1). In other words, the sentencing range by which judges have to abide is flexibly small, restricting judicial discretion to avoid sentencing disparities in a larger range.

The political mechanism under jurisdictional uniformity

The political mechanism under jurisdictional uniformity in the judicial system controls discretional disparity in China nationwide. China has established multiple mechanisms to manage the vertical judicial system of courts, from the SPC to the provincial, city, and district courts.

First, the power structures in a vertical court system and inside courts warrant external and internal equilibrium decided by different judges in all level courts. All sentencing decisions in lower courts must be formally regulated by a vertical appellate review and supervised retrial (Xia et al., 2019; Wei and Xiong, 2020; Xiong et al., 2021). In addition, the lower courts sometimes submit pre-decided adjudications to the upper courts for instruction (Ng and He, 2017; He, 2021). The power structures inside courts warrant internal equilibrium for different cases decided by different judges. Convictions and sentences in felony cases in China are usually tried by collegial panels, while complicated cases may be submitted to adjudicated committees consisting of leaders and division chiefs of the court for discussion (Wei and Xiong, 2020; Xia et al., 2019; Yu and Sun, 2022).

Second, the professional features of judges as Communist members can act as a critical lens through which to understand stable sentencing. The legal and political paths to becoming a judge should be understood in the context of the judiciary profession in China; the judge reform launched in 2014 led to judges being viewed as providing public services through a lifelong profession (Sun and Fu, 2022; Yu, 2021). The Party exercises significant leadership over courts in China, and judges are mainly Communist Party members (He, 2021; Ng and He, 2017; Sun and Fu, 2022). Both the lifelong profession and one-party-leadership courts and judges warrant stable legal and judicial politics in regard to sentencing, avoiding sentencing disparity due to political affiliation and elective motivations in party competitions, as in the US (Berdejó and Yuchtman, 2013; Cohen and Yang, 2019; Pinello, 1999).

Third, the judicial performance assessment as a managerial mechanism of judges has paved the way to achieving sentencing equilibrium and controlling the abuse of judicial discretion. In China, one of the most important managerial mechanisms in the court system is the judicial performance assessment. The SPC (1999) requires courts across all levels to establish a managerial performance system with various judicial statistical indicators. The rate or percentage of resentencing and remanding decided by upper-level courts not only relates to the rank of lower courts and the performance assessments of leaders but also links to each judge’s financial subsidiary and future promotion (He, 2021; Sun and Fu, 2022). Under this managerial mechanism in China, judges do not dare to make unusual judgments.

In general, the uniqueness of the political and legal system in China could not be an absolute promise for sentencing equilibrium but a good explanatory way to explore it. Similar regimes to manage sentencing and prevent disparities must exist in every country; the only thing for criminologists is to search and find the uniqueness that exists in any given justice. Akin to the “inhabited court” in the US (Ulmer, 2019), the easiest way to understand sentencing equilibrium in China might be through the “embedded court” (He, 2021; Ng and He, 2017). While there are limited but dominant perspectives on discretional sentencing disparity worldwide, a different perspective on organizational and contextualized sentencing in China can offer an extensive and useful understanding of sentencing philosophy for international society.

Data and method

Data

To address the research questions, the current study collected 17,619 offenders from 17,250 cases concerning rape sentences between 2014 and 2020 from China Judgments Online (zhongguo caipan wenshu wang), an official website archiving sentencing documents from every level of the People’s Courts in China. After deleting 2207 inappropriate samples for research reasons, we finally used and analyzed 15,412 offenders from 14,864 cases. All samples in this study are first-trial cases in district court at the county level with fixed-term sentences, excluding 1310 offenders tried in the second instance, 363 offenders with other types of penalties, 144 offenders tried in the Intermediate People’s Court, and 354 offenders with unclear and unspecified geographical information.

We construct the affiliated levels of the courts in the dataset according to administrative geography or judicial affiliations. In China, court structures in provinces and autonomous regions are mainly based on administrative and geographic affiliations, including county, city, and provincial government, with the exception of two courts in Hainan province. We thus use three levels: the county (district court) level, city (intermediate court) level, and province (provincial/autonomous high court) level.Footnote 1 We cluster counties into cities and cities into provinces. Although the administrative governments in four municipalities (Beijing, Chongqing, Shanghai, and Tianjin) are divided into two levels (municipality and county), the courts are divided into three levels (district court, intermediate court, and municipal high court). Thus, cases from four municipalities are still classified into three levels, but the city level should be understood as the intermediate court level, while the district court is at the county level and the municipal high court is at the provincial level.

Finally, 31 provinces, 345 unique cities, and 1974 unique counties in mainland China can be identified in our final sample. The number of offenders per province is 488.45 on average, ranging from 20 (Tibet) to 1750 (Zhejiang). The number of offenders per city is 43.79 on average, ranging from one to 381 (the First Intermediate Court in Shanghai). While we noticed that rape offenders in some cities and counties were rare, cases were not distributed geographically across the three levels. Appendix A shows summary statistics regarding sample size, number of cities and counties within each province, and average, minimum, and maximum sentence lengths (unit: month) per province.

We recognize that our results may be influenced by several factors related to the data available on China Judgments Online. Previous studies have suggested that not all relevant cases are uploaded to this platform (Liebman et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2016), and the nature of rape cases uploaded might also differ from other types of crime (Lin et al., 2024). These potential gaps could introduce bias or affect the overall conclusions. To address these concerns, we conducted four sensitivity analyses. First, we divided the provinces into two groups: those with higher upload rates (top 50% in terms of the number of cases uploaded) and those with lower upload rates (bottom 50%). For each group, we performed separate analyses to identify any potential biases or variations in results that might be attributed to the varying upload rates across provinces (see Appendix B). Second, considering that rape cases are especially susceptible to missingness due to privacy concerns, it is likely that only a small proportion of these cases are uploaded to China Judgments Online. To detect the influence of this missingness, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by randomly selecting varying percentages of the uploaded cases (90%, 80%, 70%, 60%, and 50%) and analyzing the key results under these different sample sizes (see Appendix C). Additionally, we conducted another sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of upload rates across different years. We first estimated the upload rate for rape cases each year (see Appendix E). Then, we selected the year with the highest upload rate (2019) and repeated the multi-level models to check if the conclusions remained consistent under these conditions (see Appendix F). Finally, to ensure that the specific nature of rape cases does not drive the results, we repeated the multi-level models using 10% of entirely uploaded theft cases from 2014 and 2020 to check if the main result were similar to those from the rape cases (see Appendix D).

Measures

All of the variables in this study were retrieved from the sentencing documents. Specifically, the Long Short-Term Memory Convolutional Neural Network algorithm in TensorFlow and the Viterbi framework were applied to segment the documents into sections and to extract semi-structured information (more technical details can be found in Chen et al., 2019). To verify the reliability of our data, a sample of 5000 cases generated by stratified sampling (based on the causes of action of cases) were manually marked. Compared with machine-learning results, the judicial decisions gained a 100% precision rate, a 99.71% recall rate, and an F1 value of 99.86%. This validation confirms the high recognition accuracy.

The legal factors retrieved from the sentencing documents are categorized as independent variables in regard to the focal concern of sentencing (Hartley, 2014), involving multiple legal factors such as circumstances in general divisions of the CL, including criminal behavior, post-crime guilty conscience, the criminal’s heinousness, and the factual aggravated factors of the specific rape rule of the CL, as well as other factors that may influence the sentencing outcome. Table 2 summarizes the descriptive statistics of all the variables.

The length of the fixed-term imprisonment (from 6 months to 15 years) is the only outcome variable applied in the current study; the range of outcomes is, therefore, 6–180 months. The average length of imprisonment is 45.447 months (~4 years), with a standard deviation of 27.579. The descriptive statistics show that accomplished crime (66.3%) and attempted crime (28.3%) combined constitute 94.6% of all of the cases. Only 3.3% of the cases involve multiple offenders, of which 2.2% are principal offenders and 0.5% are accessorial offenders. Among post-crime factors, 44.9% of offenders confessed their crimes while turning themselves in (16.5%), receiving forgiveness from the victim (15.2%), meritorious (0.7%), and reconciliation with the victim (1.5%). Legal factors related to criminals are factors related to the offenders themselves, including recidivism (10.3%), criminal record (18.2%), young offenders aged below 18 years (2.1%), and elderly offenders aged 75 years or older (0.7%). Special legal factors include the aggravated circumstances regulated by Article 236 of the CL, including victims aged below 14 years (16.2%), multiple victims (0.2%), rape conducted in a public place (<0.01%), gang rape (1.5%), and serious injury or death (<0.01%). Finally, other factors concern whether the criminal cases are accompanied by civil compensation (1.5%), whether the defendant hired a lawyer (no = 37.0%, appointed lawyer = 6.9%, delegated lawyer = 56.1%), and the year of sentencing.

Analytical procedure

To explore the existence of jurisdictional disparities in sentence length in China, we use a three-level design from county to city and to province. In terms of analytical methodology, both descriptive statistics and inferential statistics, as bivariate and multilevel multivariate approaches, are used. For the analytical outcome, we use a spatial map and triangle cell chart as figures to display sentencing nationwide, consisting of each province and their observable cities. We report analyses in tables to further illustrate the research findings.

First, a one-way ANOVA test is conducted to detect whether there are any sentencing disparities for rape cases among courts in China. Specifically, we draw a map to sketch out the average sentence length at the provincial level across 31 provinces and at the city level across 345 cities (Fig. 1a, b). Then, we employ Post Hoc tests to display the pairwise differences at the provincial level (Fig. 2). Finally, sentence length at the city level is examined using similar approaches, including F-tests of sentencing disparities across cities within each province and Post Hoc tests to further gauge the proportion of significant pairs (Table 3).

Second, a multilevel multivariate approach is taken to investigate the spatial disparities in sentence length after controlling for other confounders. Given that the results of the bivariate method may be confounded by other variables, multilevel random intercept models (Table 4) are adopted in the current study to explore the research questions: Do disparities in sentence length really exist across counties, cities, and provinces in China?

Consider a two-level random intercept model with cases nested in each province. The model for sentence length \({y}_{{ij}}\) of case \(i\) of province \(j\) is specified as

where \({X}_{1{ij}}\) to \({X}_{{pij}}\) are covariates and \({\varepsilon }_{{ij}}\) is the corresponding residual. \({\varepsilon }_{{ij}}\) can be further split into two error components: \({\zeta }_{j}\) denotes between-province variance and \({e}_{{ij}}\) denotes within-province variance.

Thus, a two-level random intercept model with covariates can be denoted as

The multilevel model assumes Level-1 residuals are homoscedastic for given covariates and random intercepts; as such, \({{\rm {Var}}}({\varepsilon }_{{ij}}|{{\boldsymbol{X}}}_{{\boldsymbol{j}}},{\zeta }_{j})=\theta\). The random intercepts are also homoscedastic for given covariates; as such, \({{\rm {Var}}}({\zeta }_{j}|{{\boldsymbol{X}}}_{{\boldsymbol{j}}})=\psi\). Taken together, the intraclass correlation (ICC) is denoted as

In contrast to the impact factors, the values of the ICC are much more important statistics when evaluating the degree of spatial disparity from the lower level to the nested higher level, because the ICC examines the proportion of higher-level residuals constituting the overall residuals.

Technically three-level random intercept models (cases nested in cities, and cities nested in provinces) and four-level random intercept models (cases nested in counties, counties nested in cities, and cities nested in provinces) are estimated using the same approach, except models may have more than one ICC value to represent the contribution of each level to the overall residuals.

The multilevel models are estimated using the STATA 16.1 “meglm” command and the ICC values are estimated using the “estat icc” command. According to Murphy and Myors (1998, p. 4), the power of the effect size, as .01, should be a “negligibly small” variance, while an ICC value as small as 0.05 represents only “prima facie evidence of a group effect” (LeBreton and Senter, 2008, p. 838). We thus may use the minimum 0.05 value as the standard ICC value to assess the existence of sentencing disparity in nested courts. In other words, if the value of the ICC across all levels or at any nested level among counties, cities, and provinces across the country is less than 0.05, we can conclude that disparity in sentence length for rape cases does not exist.

Result

Bivariate analyses

Figure 1a presents the provincial average of the sentence lengths. Despite the overall one-way ANOVA tests showing a significant difference among provinces (F = 8.266, p < 0.001), the provincial average of the sentence lengths is not unevenly distributed. Figure 1b depicts the spatial disparities in sentence length at the city level. Similar to the results shown in Fig. 1a, despite the overall ANOVA tests showing significant differences (F = 2.476, p < 0.001), the map shows these disparities are small, especially in most eastern provinces.

Post Hoc tests of the provincial differences are depicted in Fig. 2. In the figure, each cell in the triangle represents the differences between two paired provinces (row minus column). Red cells represent negative values (column > row), while blue cells represent positive values (row > column). Non-significant differences are marked in white. Figures 2a–d represent p < 0.1, p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001 significance levels, respectively. Figure 2 further indicates that, despite the overall ANOVA tests being significant, the proportion of pairwise differences constitutes only 14.31%, 13.10%, 9.68%, and 6.25% of the total numbers of pairs when the significance level is changed from p < 0.1 to p < 0.001.

Further, one-way ANOVA tests within each province are illustrated in Table 3, which displays the F-test, p-value (significant level), and proportion of pairwise difference in the post hoc test at significance levels of p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001. As shown in Table 3, 18 provinces indicated balanced sentencing inside the lower courts, with no significant pairwise difference, while 13 provinces revealed significance at the p < 0.05 level. Five of these showed extremely negligible differences, as 0.00% of the pairwise difference reached statistical significance (Anhui, Guangdong, Hubei, Inner Mongolia, and Zhejiang). Eight exhibit significant within-province disparities, nevertheless, the proportion of significant pairwise difference within each province reveals that only four provinces (Fujian, Jiangsu, Tianjin, and Xinjiang) reached more than 5% of overall pairs when the significant level of the post hoc tests was set at p < 0.05. Only Tianjin indicated a meaningful proportion of pairwise difference (33.33%) at the p < 0.01 level, while none were observable at p < 0.001. Notably, Tianjin should be treated as an exception as the result of an extremely small number of groups (three intermediate courts only).

All observable information in Figs. 1, 2, and Table 3 indicates that sentencing on rape cases within provinces is balanced, with negligible small disparities.

Multilevel multivariate analyses

Table 4 shows the results of the three multilevel models in this study. In Model 1, the provincial level residual is chosen as Level 2. In Model 2, both provincial- and city-level residuals are taken into consideration, resulting in a three-level model. In Model 3, variance at the provincial level, city level, and county level is taken into consideration, yielding a four-level model. Nevertheless, all models indicated sentencing equilibrium without disparity in the court system, because the value of the ICC across all levels is <0.05,

As can be seen in Model 3 of Table 4, for example, all of the fixed effects are in line with the expected directions. Compared to accomplished crimes, attempted crimes (b = −20. 450, p < 0.001) and discontinued crimes (b = −29.081, p < 0.001) receive significantly more lenient sentences. Similarly, offenders who play a minor role, turn themselves in, confess, receive forgiveness from the victim, or reconcile with the victims are all associated with shorter sentence lengths. Offenders who have a criminal record (b = 8.967, p < 0.001), raped a victim under the age of 14 years (b = 16.040, p < 0.001), or raped multiple victims (b = 76.108, p < 0.001) all receive significantly more severe sentences. Having a lawyer appointed or delegated seems to have no significant effect on the sentencing outcome. Finally, probably due to leniency policies in recent years, cases sentenced in later years generally have significantly more lenient sentences.

As for random effects, despite the residuals at the provincial level, city level, and county level all reaching statistical significance, the ICC shows that residuals across the three levels only constitute approximately 0.006, 0.017, and 0.047, respectively, of the overall residuals. Considering ICC = 0.05 is the threshold for significant spatial heterogeneity, no or negligible heterogeneity in regard to the sentence length should be acknowledged among rape sentences in China.

Sensitivity analyses

The robustness of our results was tested through three sensitivity analyses, with ICC = 0.05 chosen as the threshold for significant spatial heterogeneity.

First, we compared the ICC values obtained from provinces with higher and lower upload rates. The ICC values for both groups were comparable to those of the full sample, and all remained below 0.05 (see Appendix B). This indicates that variations in provincial upload rates did not significantly bias the results.

Second, ICC values were calculated for samples with varying proportions of the full dataset to assess the impact of missing cases. The ICC values were similar to those of the full sample (see Appendix C). Although the ICC values at the county level slightly increased as the sample size was reduced, with values of 0.053, 0.055, and 0.056 at 70%, 60%, and 50% sample sizes, respectively, they remained near 0.05. As the confidence intervals of the ICC values still crossed 0.05, we interpret this as negligible heterogeneity.

Third, we conducted an additional sensitivity analysis by selecting the year with the highest upload rate for rape cases (2019, according to Appendix E). We repeated the multilevel models using the data from this year (see Appendix F). The results remained consistent with the original models (Table 4), with ICC values for provinces, cities, and counties all remaining below 0.05, reinforcing that the conclusions are robust in our most representative cases.

Finally, we repeated the multilevel models using 10% of entirely uploaded theft cases from 2014 and 2020. The ICC values from this analysis were consistent with those from the rape cases (Table 4), remaining below the 0.05 threshold. Specifically, the ICC values for provinces, cities, and counties were 0.016, 0.024, and 0.047, respectively (see Appendix D). This confirms that the results are not driven by the specific nature of rape cases, further supporting the robustness of our findings.

Discussion and conclusion

We have empirically demonstrated sentencing equilibrium in rape cases nationwide from the perspective of the embedded court, by viewing sentence length at the levels of the county (district), city (intermediate), and province (high) in China. We have already discussed the theoretical paths and appropriateness of sentencing, displayed the jurisdictional uniformity of sentencing in the legal and political system in China, and made a systematic literature review regarding the inexistence of sentencing disparity and the theoretical implication of sentencing equilibrium. We believe the readership may understand that the uniform criminal law and sentencing rules and political mechanism warrant sentencing equilibrium contextualized in a country with jurisdictional uniformity. According to Ulmer (2019, p. 492), “Courts’ decision-making processes are constrained by overarching field-wide rules, such as criminal laws, sentencing guidelines, mandatory minimum laws, administrative rules, legislative mandates, and policy and political influences.” Although we cannot differentiate between criminal law and sentencing guidelines or political mechanisms under jurisdictional uniformity is the real coercive power, and which part of formal and informal regulations play a role in the judge’s decision embedded in the courtroom, the sentencing with negligible disparity cannot be denied in China. Thus, the JUT is definitely helpful to explain the sentencing equilibrium nationwide, where the same legal and pollical mechanism in a jurisdiction constrain the sentencing disparity and guarantee the sentencing with negligible difference.

Regarding the JUT, the same sentencing rules and political mechanisms on the mixed perspective of legal, organizational, and political are just the elaboration and operationalization in a jurisdiction to prevent sentencing disparity at large. Compared to the previous non-legal theories, based on court communities, court context, organizational conformity, and inhabited court, focusing on sentencing difference or disparity (Dixon, 1995; Eisenstein et al., 1988; Flemming et al., 1992; Nardulli et al., 1988; Ulmer and Johnson 2017; Ulmer, 2019), the uniqueness of JUT is impartially to focus on sentencing equilibrium from the legal and political approach in any independent jurisdiction. In this vein, the JUT explains the spatial uniformity or negligible difference in sentencing across mainland China, county to county, intermediate to intermediate, and province to province. That is, both the uniform sentencing rules (criminal law, judicial interpretation, and sentencing guidelines) and the political mechanism regarding court and judge in a uniform judicial system nationwide illustrate this sentencing equilibrium in China (Wei and Xiong, 2020; Xiong et al., 2021). While laws and sentencing guidelines in China specify sentencing ranges of rape, with less discretional power available to decide sentence length, the political mechanism of the court system and judge pushes judges to make decisions by only focusing on the law and associated guidelines. As Zatz (2000, p. 509) concluded, “Under determinate sentencing or sentencing guidelines, there is very little room for judicial discretion.”

We discuss the JUT and demonstrate the acceptance of sentencing equilibrium in China; one may still doubt it because of the chronic influence of literature on sentencing disparity in the US. Notably, China should not be a unique country with sentencing equilibrium but should rather accompany most other countries, where jurisdictional uniformity can be observed in the same criminal law, criminal justice system, and managerial mechanisms in contextual practice. Although the less variation of county to county found in South Carolina was only explained by the legal culture and court communities (Hester, 2017; Hester and Sevigny, 2016), the real reason is probably (or must be) that nonguideline state and various sentencing laws and rotation justice contribute to the conformity statewide. In addition, research into uniform jurisdiction in Europe and Asia offers critical evidence demonstrating how jurisdictional uniformity has led to sentencing consistency and equilibrium in the last decade (Albrecht, 2013; Frisch, 2017; Junger-Tas, 1995; Pina-Sanchez and Linacre, 2013; Roberts and Ashworth, 2016; Tonry and Frase, 2001; Watamura et al., 2022). Perhaps sentencing in a uniform jurisdiction is doom to have a sentencing equilibrium because sentencing disparity may not really exist but “remains at least partially a speculative enterprise” for political reform in the US (Johnson and Dipietro, 2012, p. 837).

The article retrieved data from the national platform, which was problematic due to sample representativeness. Nevertheless, various post-examination technologies demonstrate the robustness and appropriateness of sentencing equilibrium in rape and theft cases in our sensitivity tests. We understand that sentencing equilibrium must be a huge challenge to the bulk literature on sentencing disparity. Nevertheless, our aim is to encourage criminologists to examine sentencing practices within their own jurisdictions more closely rather than simply adopting perspectives from the dominant US literature. As Ulmer (2019, p. 515) notes, “isomorphism is not inherently ‘good’ or beneficial, and organizational variation is not inherently ‘bad’.” By contrast with the phenomenon of sentencing conformity and sentencing variation, how understanding the mechanism of sentencing is perhaps much more important in each jurisdiction. While we cannot decipher the full story of sentencing philosophy in such a limited space, we would like to use the evidence regarding sentencing equilibrium in rape cases in China to emphasize the importance of jurisdictional uniformity.

Limitations should be acknowledged in the research conclusion based on data, factors, and methodology. Firstly, given the different rules of conviction and sentence decisions among different crimes, the research findings of rape cases are hard to represent all crimes. Although our previous studies in different approaches have already demonstrated that sentencing equilibrium may exist in extensive crimes in China (Wei and Xiong., 2020; Xiong et al., 2014, 2021; Xia et al., 2019), future research needs to explore more national data on different crimes. Secondly, the article focuses on the factors described in the criminal adjudication files, but extralegal factors at the court level are not considered in this study. Although the ignorance of extralegal factors should not be considered a defect of research design, exploring a bunch of different variables such as culture, caseload, age, and gender is inspired if data are available. Thirdly, counties and cities represented in this project do not have a real distribution in each province due to missing values and rare cases, thus casting doubt on the cluster level of city and province in a methodological aspect (Hester and Sevigny, 2016). Last but not least, while we encourage further study to test our explorative findings, we recommend more regional data, different crimes, and nearly full samples to extend the sentencing research in China.

All in all, it is time to doubt the existence of sentencing disparity and return the sentencing equilibrium to the international communities. To better conduct sentencing research in the twenty-first century, researchers should exhaust legal factors and court politics before turning to social inequality as a simple way of explaining sentencing. When research identifies disparities, researchers must ascertain whether they are actual disparities or methodological differences.

Data availability

Data necessary to replicate the results of this article are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Notes

In our study, we coded the four direct-administered municipalities (Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, and Chongqing) as provinces rather than cities. This decision was made to reflect their administrative status in China, where these municipalities are treated as province-level entities.

References

Albonetti CA (1991) An integration of theories to explain judicial discretion. Soc Probl 38(2):247–266. https://doi.org/10.2307/800532

Albrecht HJ (2013) Sentencing in Germany: explaining long-term stability in the structure of criminal sanctions and sentencing. Law Contemp Probl 76(1):211–236

Baumer EP (2013) Reassessing and redirecting research on race and sentencing. Justice Q 30(2):231–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2012.682602

Berdejó C, Yuchtman N (2013) Crime, punishment, and politics: an analysis of political cycles in criminal sentencing. Rev Econ Stat 95(3):741–756. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00296

Bontrager S, Barrick K, Stupi E (2013) Gender and sentencing: a meta-analysis of contemporary research. J Gend Race Justice 16(2):349–372

Boyd CL, Epstein L, Martin AD (2010) Untangling the causal effects of sex on judging. Am J Political Sci 54(2):389–411. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00437.x

Casey S, Wilson JJ (1998) Discretion, disparity or discrepancy? A review of sentencing consistency. Psychiatry Psychol Law 5(2):237–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719809524937

Chen H, Cai D, Dai W, Dai Z, Ding Y (2019) Charge-based prison term prediction with deep gating network. In: Inui K, Jiang J, Ng V, Wan X (eds) Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), Hong Kong, China. Association for Computational Linguistics, 6362–6367. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/D19-1667

Cohen A, Yang CS (2019) Judicial politics and sentencing decisions. Am Econ J: Econ Policy 11(1):160–191. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20170329

Crow MS, Goulette N (2021) Sex, politics, and U.S. district court outcomes: examining variation in judge‐initiated downward guideline departures. Am J Crim Justice https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-021-09648-3

Daly K, Bordt R (1995) Sex effects and sentencing: a review of the statistical literature. Justice Q 12(1):141–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418829500092601

Divine JM (2018) Booker disparity and data-driven sentencing. Hastings Law J 69(3):771–834

Dixon J (1995) The organizational context of criminal sentencing. Am J Sociol 100(5):1157–1198. https://doi.org/10.1086/230635

Drápal J (2020) Sentencing disparities in the Czech Republic: empirical evidence from post-communist Europe. Eur J Criminol 17(2):151–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370818773612

Eisenstein J, Flemming RB, Nardulli PF (1988) The contours of justice: communities and their courts. Scott, Foresman, Boston

Engen R (2011) Racial disparity in the wake of Booker/Fanfan making sense of “messy” results and other challenges for sentencing research. Criminol Public Policy 10(4):1139–1149. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9133.2011.00773.x

Engen RL, Gainey RR, Crutchfield RD, Weis JG (2003) Discretion and disparity under sentencing guidelines: the role of departures and structured sentencing alternatives. Criminology 41(1):99–130. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1177/0022427819874862

Flemming RB, Nardulli PF, Eisenstein J (1992) The craft of justice: politics and work in criminal court communities. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA

Farrell A, Ward G, Rousseau D (2010) Intersections of gender and race in federal sentencing: examining court contexts and effects of representative court authorities. J Gend Race Justice 14(1):85–126

Forst ML (1982) Sentencing reform: experiments in reducing disparity. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills

Franklin TW, Henry TK (2020) Racial disparities in federal sentencing outcomes: clarifying the role of criminal history. Crime Delinq 66(1):3–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128719828353

Freed D (2003) The effects of region, circuit, caseload and prosecutorial policies on disparity. Fed Sentencing Rep 15(3):165–178. https://doi.org/10.1525/fsr.2003.15.3.165

Frisch W (2017) From disparity in sentencing towards sentencing equality: the German experience. Crim Law Forum 28(3):437–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10609-017-9327-6

Gabbidon SL, Jordan KL, Penn EB, Higgins GE (2014) Black supporters of the no-discrimination thesis in criminal justice: a portrait of an understudied segment of the black community. Crim Justice Policy Rev 25(5):637–652. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403413489705

Gruhl J, Spohn C, Welch S (1981) Women as policymakers: the case of trial judges. Am J Political Sci 25(2):308–322. https://doi.org/10.2307/2110855

Hagan J, Bumiller K (1983) Making sense of sentencing: a review and critique of sentencing research. In: Blumstein A, Cohen J, Martin S, Tonry MH (eds) Research on sentencing: the search for reform, vol II. National Academy Press, Washington, DC

Hartley RD (2014) Focal concerns theory. In: The encyclopedia of theoretical criminology. pp. 1–5

Hartley RD, Tillyer R (2019) Inter-district variation and disparities in federal sentencing outcomes: case types, defendant characteristics, and judicial demography. Criminol Crim Justice Law Soc 20(3):46–63. https://ccjls.scholasticahq.com/article/11132.pdf

Haynes SH, Ruback B, Cusick GR (2010) Courtroom workgroups and sentencing: the effects of similarity, proximity, and stability. Crime Delinq 56(1):126–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128707313787

He X (2021) Pressures on Chinese judges under Xi. China J 85:49–73. https://doi.org/10.1086/711751

Hester R (2017) Judicial rotation as centripetal force: sentencing in the court communities of South Carolina. Criminology 55(1):205–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12132

Hester R, Sevigny EL (2016) Court communities in local context: a multilevel analysis of felony sentencing in South Carolina. J Crime Justice 39(1):55–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/0735648X.2014.913494

Herz C (2020) Striving for consistency: why German sentencing needs reform. Ger Law J 21(8):1625–1648. https://doi.org/10.1017/glj.2020.90

Hofer PJ (2012) Data, disparity, and sentencing debates: lessons from the TRACreport on inter-judge disparity. Fed Sentencing Rep 25(1):37–45. https://doi.org/10.1525/fsr.2012.25.1.37

Hou Y, Truex R (2022) Ethnic discrimination in criminal sentencing in China. J Politics 84(4):2294–2299. https://doi.org/10.1086/719635

Hu M, Liang B, Huang S (2017) Sex offenses against minors in China: an empirical comparison. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 61(10):1099–1124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X15616220

Johnson BD (2006) The multilevel context of criminal sentencing: integrating judge and county-level influences. Criminology 44(2):259–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2006.00049.x

Johnson BD, Dipietro SM (2012) The power of diversion: intermediate sanctions and sentencing disparity under presumptive guidelines. Criminology 50(3):811–850. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2012.00279.x

Junger-Tas J (1995) Sentencing in the Netherlands: context and policy. Fed Sentencing Rep 7(6):293–299. https://doi.org/10.2307/20639820

Kim B, Spohn C, Hedberg EE (2015) Federal sentencing as complex collaborative process: judges, prosecutors, judge-prosecutor dyads, and disparity in sentencing. Criminology 53(4):597–623. https://doi.org/10.2307/20639820

Kim B, Wang X, Cheon H (2019) Examining the impact of ecological contexts on gender disparity in federal sentencing. Justice Q 36(3):466–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2018.1463388

King RD, Light MT (2019) Have racial and ethnic disparities in sentencing declined? Crime Justice 48:365–437. https://doi.org/10.1086/701505

Kingsnorth R, Lopez J, Wentworth J, Cummings D (1998) Adult sexual assault: the role of racial/ethnic composition in prosecution and sentencing. J Crim Justice 26(5):359–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2352(98)00012-9

LeBreton JM, Senter JL (2008) Answers to 20 questions about Interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organ Res Methods 11(4):815–862. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106296642

Lee M, Ulmer JT, Park M (2011) Drug sentencing in South Korea: the influence of case-processing and social status factors in an ethnically homogeneous context. J Contemp Crim Justice 27(3):378–397. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043986211412574

Li Y, Longmire D, Lu H (2018) Death penalty disposition in China: what matters? Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 62(1):253–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X16642426

Liebman BL, Roberts ME, Stern RE, Wang AZ (2020) Mass digitization of Chinese court decisions: how to use text as data in the field of Chinese law. J Law Courts 8(2):177–201. https://doi.org/10.1086/709916

Lin J, Xia Y, Cai T (2024) Tip of the Iceberg? An evaluation of the non-uploaded criminal sentencing documents in China. Asian J Criminol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-024-09434-0

Lin X, Liu S, Li E, Ma Y (2022) Sentencing disparity and sentencing guidelines: the case of China. Asian J Criminol 17(2):127–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-021-09357-0

Lu H, Kelly B (2008) Courts and sentencing research on contemporary China. Crime Law Soc Change 50(3):229–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-008-9132-6

Lu H, Liang B, Liu S (2013) Serious violent offenses and sentencing decisions in China—are there any gender disparities? Asian J Criminol 8(2):159–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-012-9155-x

Lynch M (2019) Focally concerned about focal concerns: a conceptual and methodological critique of sentencing disparities research. Justice Q 36(7):1148–1175. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2019.1686163

Ma C, Yu XH, He HN (2016) Big data analysis: China judicial judgment document disclosure report (in Chinese). China Law Rev 4:195–246

Mamak K, Dudek J, Koniewski M, Kwiatkowski D (2022) Sex, age, education, marital status, number of children, and employment—the impact of extralegal factors on sentencing disparities. Eur J Crime Crim Law Criminol 30(1):69–97. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718174-bja10030

Mitchell Q (2005) A meta-analysis of race and sentencing research: explaining the inconsistencies. J Quant Criminol 21(4):439–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-005-7362-7

Murphy KR, Myors B (1998) Statistical power analysis: a simple and general model for traditional and modern hypothesis tests. Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ

Ng KH, He X (2017) Embedded courts: judicial decision-making in China. Cambridge University Press, New York

Nowacki JS (2020) Gender equality and sentencing outcomes: an examination of state courts. Crim Justice Policy Rev 31(5):673–695. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403419840804

Nardulli PF, Eisenstein J, Flemming RB (1988) The tenor of justice: criminal courts and the guilty plea process. University of Illinois Press, Champaign

Peng Y, Cheng J (2022) Ethnic disparity in Chinese theft sentencing: a modified focal concerns perspective. China Rev 22(3):47–71

Philippe A (2020) Gender disparities in sentencing. Economica 87(348):1037–1077. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12333

Pina-Sanchez J, Linacre R (2013) Sentence consistency in England and Wales: evidence from the crown court sentencing survey. Br J Criminol 53(6):1118–1138. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azt040

Pinello DR (1999) Linking party to judicial ideology in American courts: a meta-analysis. Justice Syst J 20(3):219–254. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27976992

Pratt TC (1998) Race and sentencing: a meta-analysis of conflicting empirical research results. J Crim Justice 26(6):513–523. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2352(98)00028-2

Roberts JV, Ashworth A (2016) The evolution of sentencing policy and practice in England and Wales, 2003–2015. Crime Justice 45:307. https://doi.org/10.1086/685754

Shi Y, Lao J (2022) Sex disparities in sentencing and judges’ beliefs: a vignette approach. Vict Offenders 17(4):597–619. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2021.1947427

SPC (1999) Notice of First Fifth Years Reform Framework (renmin fayuan wunian gaige gangyao)

SPC (2013) Sentencing guideline on regular offences (guanyu changjian fanzui de liangxing zhidao yijian)

SPC (2017) Opinions on implementing the sentencing guideline amendment on regular offences (guanyu shishi xiudinghou de changjian fanzui de liangxing zhidao yijian de tongzhi)

Spohn CC (2000) Thirty years of sentencing reform: the quest for a racially neutral sentencing process. Crim Justice 3:427–501

Steffensmeier D, Herbert C (1999) Women and men policymakers: does the judge’s gender affect the sentencing of criminal defendants? Soc Forces 77(3):1163–1196. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/77.3.1163

Steffensmeier D, Kramer J, Streifel C (1993) Gender and imprisonment decisions. Criminology 31(3):411–446. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1993.tb01136.x

Steffensmeier D, Ulmer JT, Kramer J (1998) The interaction of race, gender, and age in criminal sentencing: the punishment cost of being young, black, and male. Criminology 36(4):763–798. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1998.tb01265.x

Stith K, Cabranes J (1998) Fear of judging: sentencing guidelines in the federal courts. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London

Sun Y, Fu H (2022) Of judge quota and judicial autonomy: an enduring professionalization project in China. China Q 251:866–887. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741022000248

Thomson RJ, Zingraff MT (1981) Detecting sentencing disparity: some problems and evidence. Am J Sociol 86(4):869–880. https://doi.org/10.1086/227320

Tonry M (2016) Differences in national sentencing systems and the differences they make. Crime Justice 45:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1086/688454

Tonry MH, Frase RS (2001) Sentencing and sanctions in western countries. Oxford University Press, New York

Ulmer JT (1995) The organization and consequences of social pasts in criminal courts. Sociol Q 36(3):901–919. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.1995.tb00455.x

Ulmer JT (2012) Recent developments and new directions in sentencing research. Justice Q 29(1):1–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2011.624115

Ulmer JT (2014) Sentencing research. In: Bruinsma G, Weisburd D (eds) Encyclopedia of criminology and criminal justice. pp. 4759–4769

Ulmer JT (2019) Criminal courts as inhabited institutions: making sense of difference and similarity in sentencing. Crime Justice 48:483–522. https://doi.org/10.1086/701504

Ulmer JT, Johnson BD (2004) Sentencing in context: a multilevel analysis. Criminology 42(1):137–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2004.tb00516.x

Ulmer JT, Johnson BD (2017) Organizational conformity and punishment: federal court communities and judge-initiated guideline departures. J Crim Law Criminol 107(2):253–292. https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc/vol107/iss2/3/

Ulmer JT, Kramer JH (1996) Court communities under sentencing guidelines: dilemmas of formal rationality and sentencing disparity. Criminology 34(3):383–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1996.tb01212.x

Ulmer JT, Kramer JH (1998) The use and transformation of formal decision-making criteria: sentencing guidelines, organizational contexts, and case processing strategies. Soc Probl 45(2):248–267. https://doi.org/10.2307/3097246

Ulmer JT, Light MT, Kramer JH (2011) Racial disparity in the wake of the Booker/Fanfan decision: an alternative analysis to the USSC’s 2010 report. Criminol Public Policy 10(4):1077–1118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9133.2011.00761.x

Veiga A, Pina-Sánchez J, Lewis S (2023) Racial and ethnic disparities in sentencing: what do we know, and where should we go? Howard J Crime Justice 62(2):167–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/hojo.12496

Volkov V (2016) Legal and extralegal origins of sentencing disparities: evidence from Russia’s criminal courts. J Empir Leg Stud 13(4):637–665. https://doi.org/10.1111/jels.12128

Vuletic I, Tomicic Z (2017) The problem of disparity in sentencing: comparative insight and what can be done to make sentencing more uniform. J East -Eur Crim Law 2017(2):133–144

Wang X, Mears DP (2010) A multilevel test of minority threat effects on sentencing. J Quant Criminol 26(2):191–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-009-9076-8

Ward G, Farrell A, Rousseau D (2009) Does racial balance in workforce representation yield equal justice: race relations of sentencing in federal court organizations. Law Soc Rev 43(4):757–806. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5893.2009.00388.x