Abstract

Despite ample research on the association between the availability of flexible working arrangements (FWAs) and satisfaction from an individual perspective, little has explored the dyadic correlation between the availability of FWAs and satisfaction with work-life flexibility (WLF) from a couple-level perspective among working parents. Drawing on a linked lives perspective and the work-family border theory, this study contributes to the literature by adopting the longitudinal couple-level dyadic data from the Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey (2001–2021) to examine how couples’ availability of FWAs affects their own and their spouses’ satisfaction with WLF among working parents. The results show that among couples with children, mothers’ availability of FWAs significantly improves their own and their husbands’ satisfaction with WLF. In contrast, fathers’ access to FWAs only improves their own satisfaction with WLF. Moreover, the impact of one’s availability of FWAs on their satisfaction with WLF, as well as the effects of mothers’ availability of FWAs on their husbands’ satisfaction, are more pronounced among formal contract workers. Overall, this study underscores the dyadic association between couples’ FWAs and satisfaction with WLF among working parents, delineating an asymmetric dynamic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the contemporary landscape of work, characterized by globalization, technological advancements, and evolving societal norms, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, flexible working arrangements (FWAs) have emerged as a critical component in modern workplaces. FWAs encompass workplace options that offer employees more control over how much, when, or where they work (Chandola et al. 2019; Chung et al. 2021; Li & Wang, 2022). The availability of FWAs not only promotes better work-life balance but also enhances employee satisfaction and well-being (Anderson & Kelliher, 2009; L. et al. 2018; Wheatley, 2017). Moreover, the distinctive challenges and responsibilities faced by working parents in balancing their professional and familial roles underscore the paramount importance of comprehending the impact of FWAs’ availability on this demographic (Chung & Van Der Horst, 2020; Hokke et al. 2021). Additionally, satisfaction with work-life flexibility (WLF) serves as a vital indicator of the effectiveness of the workplace, significantly contributing to overall employee well-being. Therefore, understanding the correlation between the availability of FWAs and satisfaction with WLF among working parents is crucial for organizations fostering a productive, harmonious work environment while supporting parents in maintaining work-life balance.

Previous research mostly adopts an individual-level perspective and often examines how an individual’s availability of FWAs affects their satisfaction and well-being (Atkinson & Hall, 2011; Li & Wang, 2022; Wheatley, 2017). A substantial body of prior research adopted individual-centric theories, such as the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) theory, to investigate this relationship (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Krick et al. 2022; Sarwar et al. 2021). However, there are few studies examining the dyadic relationship between the availability of various FWAs and satisfaction at the couple-level, which impedes a nuanced understanding of the dynamic within the household. An individual’s satisfaction with WLF is not only shaped by their own work arrangements but also by their spouse’s work situation, given the intricately linked lives of spouses (Chung & Van Der Lippe, 2020; Moen & Yu, 2000; Wang & Cheng, 2023). Failing to account for spousal effects neglects a crucial aspect of how work-family dynamics operate within the household, especially for working parents who share childcare responsibilities and encounter significant work-life conflict. Another limitation of existing studies is the lack of differentiation between various occupational statuses, such as contract types (i.e., formal and casual contracts). This distinction holds substantial significance, as it can result in varying implications for job security, stability, benefits, and overall work experiences (Wooden & Warren, 2003). Formal contract workers, who typically enjoy high-quality flexibility, often experience more stable work conditions, better access to benefits, and a stronger sense of job security (Drobnič et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2022). Conversely, casual contract workers, who are typically afforded low-quality flexibility, may contend with uncertainties regarding work schedules, benefits, and long-term employment prospects (Kalleberg, 2000; Mai et al. 2023; Pirani & Salvini, 2015). Failing to distinguish between formal and casual contract workers clearly may lead to findings that do not adequately capture the nuanced and diverse experiences of different types of workers, especially for working parents under exacerbated work-life conflict. This oversight restricts a comprehensive understanding of the effects of the availability of FWAs and the generalizability of the conclusions drawn from such research.

This study seeks to address the gaps in the existing literature by pursuing two primary objectives. The first objective is to utilize 21 waves of couple-level dyadic data from the Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey to comprehensively examine the effects of one’s availability of various FWAs on their own and the spouse’s satisfaction with WLF among couples with children. This is crucial in portraying the interconnectedness of work and family dynamics. The second objective is to investigate the disparate effects of different contract types on satisfaction with WLF among couples with children. Furthermore, this study aims to explore the interactive effects of contract types and gender, shedding light on the comprehensive ways in which gender plays a role in satisfaction with work-family flexibility for working parents in the context of varying occupational status.

This study significantly enhances our understanding of the relationship between the availability of FWAs and the satisfaction with WLF regarding theoretical contributions and policy implications. First, by extending theories such as the JD-R theory and aligning them with the linked lives perspective and the work-family border theory, our study recognizes the intricate interconnectedness of work and family life, emphasizing the importance of considering both domains from a couple-level perspective when evaluating WLF. Second, this study underscores the significance of different occupational statuses, such as contract types. This study underscores the unconditional benefits of having access to FWAs and refines our understanding of the impact of different contract types. It bridges the gap between theoretical foundations and real-life dynamics, underscoring the need for policymakers and organizations to promote formal contracts to amplify the positive effects of the availability of FWAs for working parents. Third, this study emphasizes the critical role of addressing gender inequality in the context of FWAs and highlights the nuanced impact of such policies on different genders within the household among working parents. To mitigate gender inequalities, organizations should tailor flexibility policies to account for mothers’ unique challenges, promote equal opportunities, combat gender biases, and encourage open communication between working parents.

Theoretical background

Availability of FWAs and work-life balance

FWAs are workplace options that entail employees’ control over how much, when, or where they work, such as flexible schedules, homeworking, etc. (Chandola et al. 2019; Chung & Van Der Lippe, 2020; Li & Wang, 2022). Over the past few decades, FWAs have become increasingly important in the Australian labor market, reflecting the growing demand for work-life balance and the changing workforce (Cooper & Baird, 2015; Hayman, 2009). The Australian government has implemented several initiatives to promote FWAs, including the Fair Work Act 2009, which recognizes the significance of FWAs in enhancing work-life balance. This act allows employees to request modifications to their working arrangements, and it obliges employers to seriously consider these requests, with the ability to refuse them only on reasonable business grounds (Waterhouse & Colley, 2010). During the COVID-19 pandemic, FWAs have been further expanded as a solution to allow organizations to continue operations and preserve jobs all over the world. Recently, there has been growing public support for normalizing and legitimizing access to FWAs in the future due to their perceived benefits in improving employee well-being and the work environment.

Numerous studies have predominantly adopted individual-level theoretical frameworks, notably the JD-R theory, to examine the relationship between the availability of FWAs and employee satisfaction. According to JD-R theory, FWAs, as resources, can mitigate job demands, reduce stress, and enhance job satisfaction by affording employees greater control over their work schedules and responsibilities (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Krick et al. 2022). Therefore, individual-level studies have emphasized the impact of FWAs’ availability on an employee’s psychological and physiological well-being, job satisfaction, and work-life balance (Chung & Van Der Lippe, 2020; L. et al. 2018; Wheatley, 2017). Additionally, a substantial body of couple-level studies on the correlation between employment and satisfaction has been concentrated on the dyadic effects of couples’ unemployment on satisfaction (Knabe et al. 2016; Luhmann et al. 2014; Marcus, 2013).

However, previous literature predominantly focuses on the effects of FWAs’ availability at an individual level, often overlooking the potential couple-level effects. The existing research has primarily examined how the availability of various FWAs influences an individual’s experience within the work domain, neglecting the interplay and shared experiences of couples in dual-earner households. Understanding how one’s FWAs impact both partners among working parents in a relationship is crucial, as it can illuminate the dynamics of WLF at a broader level, capturing the complexities of shared responsibilities and decision-making within households. This dyadic perspective reveals the cross-over effects of couples’ availability of FWAs on satisfaction with WLF among working parents.

Cross-over effects of couples’ availability of FWAs on satisfaction with WLF

In examining the potential dyadic effects of FWAs’ availability on satisfaction with WLF from the couple-level perspective among working parents, it is essential to integrate insights from work-family border theory and the linked lives perspective. Work-family border theory emphasizes the permeability and negotiation of boundaries between work and family domains. When one partner benefits from FWAs, it influences the work-family borders within the household, potentially positively impacting the other partner’s satisfaction with WLF through improved coordination and balance between work and family responsibilities (Clark, 2000). Although the availability of FWAs can make the work-family borders (physical, temporal, or psychological) flexible and permeable, the border permeability between work and family domains and their directions may not be symmetrical across genders. Instead, such cross-over effects often involve the expansion of one domain and the contraction of the other, depending on which domain fathers and mothers identify the most or the degree of priority they put on each domain in their lives (Chung et al. 2021; Clark, 2000; Wang & Cheng, 2023). In Australia, the widely prevalent traditional gender role norms suggest that mothers who mainly derive their identity from the family domain tend to use FWAs to do more household and childcare tasks, leading to the border permeability from family to work. While fathers who prioritize the work domain tend to use FWAs to do more work, leading to the border permeability from work to family (Baxter, 2002; Chesters et al. 2009; Craig & Mullan, 2010; Johnston et al. 2020).

Drawing on the work-family border theory and the linked lives perspective, this study aims to investigate how couples’ availability of FWAs may affect their own and the spouses’ satisfaction with WLF among working parents. The linked lives perspective posits that the lives of individuals in a partnership or family are intricately interconnected, and decisions made by one family member can significantly affect the experiences and well-being of other family members and vice versa (Elder, 1998; Wang & Cheng, 2023). Such cross-over effects may be particularly pronounced between fathers and mothers because couples share high intimacy and cooperate closely in household responsibilities. Thus, exploring the within-couple relationships between FWAs’ availability and the satisfaction with WLF for working parents under the “linked lives” framework could provide us with more nuanced insights into the theoretical and empirical findings.

Integrating the unequal and gendered cross-over effects of couples’ availability of FWAs on personal and spousal satisfaction with WLF, we make the following empirical predictions. Specifically, among couples with children, mothers’ availability of FWAs is positively associated with their own satisfaction with WLF. There are two primary reasons. First, mothers often bear a substantial share of childcare and household responsibilities. Access to FWAs, such as flextime and homeworking policies, can facilitate a more harmonious balance between their work commitments and family roles (Shockley & Allen, 2007; Yucel & Chung, 2023). Second, increased control over their work environment affords mothers greater autonomy in managing their time allocation between work and family obligations. This enhanced control and flexibility have the potential to bolster their satisfaction with WLF (Steckermeier, 2021; Yu et al. 2018). Overall, mother’s access to FWAs will enhance their satisfaction with work-family flexibility.

In addition, we anticipate that mothers’ access to FWAs will improve their husbands’ satisfaction with WLF. This is due to the traditional gendered division of household labor and the decreased work-family conflict between working parents within the household. First, among couples with children, the responsibility of raising children and managing household tasks is often shared between spouses. Therefore, if mothers have access to FWAs that allow them to better balance their work and family responsibilities, it can lead to their increased distribution of household and caregiving duties, subsequently alleviating the family burdens on their husbands (Chung et al. 2022; Johnston et al. 2020; Wang & Cheng, 2023). Second, the availability of FWAs can assist mothers in reducing the conflict they experience between work and family obligations, contributing to a more supportive family dynamic and, therefore, enhancing their husbands’ satisfaction with WLF (Erden Bayazit & Bayazit, 2019).

However, in contrast to the direct effects of mothers’ access to FWAs on their own satisfaction with WLF, the spousal effects measure the indirect impact on their husbands’ satisfaction, which is expected to be smaller in magnitude (Luhmann et al. 2014; Wang & Cheng, 2023). This disparity arises from the fundamental difference in how individuals assess their own satisfaction versus that of their spouse. When individuals evaluate their satisfaction with WLF or any other aspects of their lives, they are directly experiencing and evaluating their own feelings and experiences. This direct link typically yields a more pronounced effect size due to the immediacy of the assessment. Conversely, evaluating the satisfaction of one’s spouse involves navigating the intricate interplay of two individuals’ perceptions, needs, and behaviors. This complexity inherent in spousal dynamics often leads to a dampened effect size compared to the impact on one’s own satisfaction. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H1: Among couples with children, mothers’ availability of FWAs is positively associated with their own and their husbands’ satisfaction with WLF. Furthermore, the correlation between a mother’s availability of FWAs and her husband’s satisfaction is more significant than that of a husband’s availability of FWAs and his wife’s satisfaction.

Regarding fathers, like mothers, we expect that their availability of FWAs will improve their satisfaction with WLF. This expectation is based on the following considerations. First, the availability of FWAs, such as flextime or homeworking policies, can provide fathers with elevated autonomy and control over their work schedules. This autonomy serves to mitigate the stress and challenges associated with rigid work hours and extended working periods. Second, fathers with access to FWAs could free up more time to spend with their families and engage in family leisure activities. This increased involvement can positively impact their satisfaction, as they experience a deeper connection with their families and may encounter fewer work-family conflicts (McLaughlin & Muldoon, 2014).

However, unlike mothers, it is anticipated that fathers’ access to FWAs is not significantly correlated with their wives’ satisfaction. This may be due to the traditional domestic division of labor and the flexibility stigma towards men in the workplace. First, research has indicated that fathers, even when afforded the option of FWAs, may not consistently increase their contributions to domestic or caregiving responsibilities to the same extent as mothers (Chung et al. 2021; Wang & Cheng, 2023). Therefore, fathers’ access to FWAs may not significantly change this unequal distribution of labor within the household or alleviate the family burdens on their wife’s shoulders, which could not significantly affect their wives’ satisfaction with WLF (E.H.-W. Kim & Cheung, 2019). Second, in some cases, the workplace culture and policies may not fully support fathers in taking advantage of FWAs effectively. Fathers may face stigma or a lack of understanding from their employers and colleagues when they attempt to use these arrangements, limiting their ability to take advantage of such opportunities (Chung, 2020). Consequently, their wives may not observe significant improvements in WLF due to these systemic barriers. Therefore, we propose the hypothesis:

H2: Among couples with children, fathers’ availability of FWAs is positively associated with their own satisfaction with WLF but is not significantly related to their wives’ satisfaction with WLF.

Variation in contract types: formal vs. casual contracts

In recent decades, there has been a notable transformation in employment relations, leading to a departure from the once-homogeneous composition of the labor market. This shift has resulted in a decline in the prevalence of standard employment, typified by full-time and permanent positions, and has given rise to various forms of non-standard employment, characterized by casual contracts (ILO, 2016). In Australia, permanent employees generally expect regular, ongoing employment with their current employer and access to paid leave entitlements. Fixed-term employees are typically entitled to the same wages, penalties, and leave as permanent employees. On the other hand, the main indicator the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) uses for casual employment is whether an employee is entitled to paid leave, including paid sick or annual leave. Casual employees tend to have much less job stability than permanent employees, with less certainty about the regularity of work hours and earnings from week to week (ABS, 2022). Consequently, our exploration seeks to discern the distinct effects of formal and casual contracts on understanding the nuanced impact of FWAs on WLF satisfaction in Australia. The rationale for examining the effects of contract types originates from segmentation theory. This theory bifurcates the contemporary labor market into two principal segments, each governed by its unique characteristics, regulations, and conditions (Doeringer & Piore, 1985). The primary labor market is characterized by stable, well-compensated positions offering diverse benefits, career promotion opportunities, and job security. By contrast, the secondary labor market encompasses much of the non-standard employment, such as part-time jobs, temporary contracts, and certain types of self-employment (Doeringer & Piore, 1985; Kalleberg, 2003).

Drawing on this theoretical framework, formal contracts often grant employees more autonomy and control over their work schedules and conditions. This type of high-quality flexibility offers predictability in work hours, benefits, and job security, promoting a more stable work-life balance. Conversely, casual contracts are often correlated with job precarity, lack of benefits, inconsistent work schedules, and other low-quality flexibility, potentially undermining workers’ health (Green et al. 2009; Kalleberg, 2000). In such cases, the positive effects of having access to FWAs on WLF satisfaction may be offset due to these arrangements’ inherent instability and compensatory nature. Therefore, there exists a significant disparity in the association between the availability of FWAs and satisfaction with WLF based on different contract types.

Integrating the differences between formal and casual contracts, as well as the cross-over effects of couples’ availability of FWAs on their own and their spouses’ satisfaction with WLF among working parents, we make the following empirical predictions. Among couples with children, the availability of FWAs for mothers is expected to significantly enhance their own satisfaction with WLF, with stronger effects for formal contract workers. Formal contracts provide mothers with more stable and predictable work conditions, allowing them to effectively manage work and family responsibilities (Origo & Pagani, 2009; Wilczyńska et al. 2016). While FWAs offer casual workers valuable autonomy, this flexibility can be undermined by the lack of supplementary benefits, such as leave and healthcare, potentially leading to conflicts between work and family roles (Hosking & Western, 2008; Leighton & Painter, 2001). Thus, the impact of FWAs on WLF satisfaction is likely more pronounced for mothers in formal contracts. For fathers, the availability of FWAs is similarly expected to enhance their satisfaction with WLF, particularly among formal contract workers, who benefit from greater job security and predictable schedules. While FWAs can help casual workers manage unstable work hours, the absence of benefits and career opportunities in casual contracts may diminish the positive effects of FWAs, making the impact more significant among formal contract workers (Chung, 2020; Hokke et al. 2021).

The cross-over effects of mothers’ availability of FWAs are anticipated to positively impact their husbands’ satisfaction with WLF, regardless of whether mothers are employed under formal or casual contracts, though the effect is expected to be stronger for formal contract workers. This is attributed to traditional gender roles, where mothers often bear a larger share of household and childcare responsibilities (Chung & Van Der Lippe, 2020; Wang & Cheng, 2023). FWAs like flextime or homeworking enable mothers under formal contracts to manage these duties more effectively, reducing family burdens on their husbands and improving their WLF satisfaction. While typically enjoying more flexibility, casual contract workers may also benefit from FWAs by aligning their work schedules with family needs. However, the limited workplace benefits associated with casual contracts may diminish the impact of FWAs. In contrast, the effect of fathers’ availability of FWAs on their wives’ WLF satisfaction is expected to remain insignificant, regardless of contract type. This is due to entrenched societal norms that position mothers as the primary caregivers and encourage fathers to prioritize their professional responsibilities, limiting the cross-over effects of FWAs on wives’ satisfaction with WLF (Chung & Van Der Horst, 2020; Chung & Van Der Lippe, 2020; Wang & Cheng, 2023). Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

H3: Among couples with children, the availability of FWAs for both mothers and fathers is positively associated with their own and their spouses’ satisfaction with WLF. Furthermore, this impact is stronger among formal contract workers compared to casual workers.

H4A: Among couples with children, the effect of fathers’ availability of FWAs on their own satisfaction with WLF will remain positively significant among both formal contract workers and casual workers, but with a stronger impact observed among formal contract workers.

H4B: Among couples with children, the effect of fathers’ availability of FWAs on their wives’ satisfaction with WLF will remain insignificant among both formal contract workers and casual workers.

Method

Data and sample

We used data from the 21 waves of the HILDA survey (2001–2021) because these waves contain consistent measures of the availability of FWAs. The HILDA survey is a household-based panel study that collects information on many aspects of life in Australia, including household and family relationships, income and employment, health and education, the availability of FWAs, satisfaction, employment status, and other important demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. The study collected data annually through interviews with all people over 15 years old in each household. In wave one, the study collected data from 7682 households (13969 individuals). The average response rate exceeds 60%. We take advantage of the HILDA’s longitudinal design and multi-topic nature to examine the relationship between couples’ availability of FWAs and satisfaction with WLF among working parents.

To construct our analytic sample, we first restrict the sample to heterosexual couples who are married or cohabiting and have completed the self-administered questionnaire. Next, the sample is restricted to couples where both spouses are employed and in the working ages (18–65). Self-employed respondents are excluded due to the distinctive nature of their work arrangements. We further restrict the sample to couples with at least one dependent child (aged 0–24 in the household), occupying more than half of the original sample, since working parents may report more diverse aspects of work-family conflict. Finally, a small number of cases with missing values (~1.20%) are omitted. The final sample (unbalanced panel data) consists of 3111 couples and 15365 couple-years observations. Further details on the analytic sample construction process are provided in Table A1 (appendix).

Measures

The outcome variable is satisfaction with WLF (WLF), asking for “the flexibility to balance work and non-work commitments satisfaction.” The variable ranges from 0 to 10, where 0 means “totally dissatisfied” and 10 means “totally satisfied.”

The key explanatory variable is the availability of FWAs. The HILDA asked respondents about the availability of workplace FWAs, such as flexible start/finish times and home-based work. Therefore, this study defines the availability of FWAs based on whether individuals have access to at least one of these two FWAs in their workplace. The dummy variable consists of 1 (indicating the individual has access to at least one FWA) and 0 (indicating the individual has no access to either of the two FWAs). To strengthen our results, we conducted a series of sensitivity analyses. In the sensitivity analyses, we first adopt an additional variable comprising four categories (“neither has access to any FWAs”, “only the father has access to FWAs”, “only the mother has access to FWAs,” and “both have access to FWAs”) to examine the conditional effects of the availability of FWAs among couples with children. Second, we use flextime and homeworking, respectively, in two panels to test the effects of different combinations of the availability of FWAs. Reassuringly, the results are generally consistent.

To understand the differential effects of the availability of FWAs on WLF by employment status, we introduce contract type as the moderator. The HILDA asked about the status of the current job’s employment contract. We construct contract type as one dichotomous variable, where 1 represents “formal contract worker” (“employed on a fixed-term contract” and “employed on a permanent or ongoing basis”) and 0 means “casual worker” (employed on a casual basis).

The study also controls for a range of variables that have been shown to affect satisfaction with WLF. Job demand is assessed using four questions from the module “Opinions about Jobs”: “My job is complex and difficult,” “My job is more stressful than I had ever imagined,” “My job often requires me to learn new skills,” “I fear that the amount of stress in my job will make me physically ill.” The father’s income share represents the percentage of the father’s income out of the sum of both parents’ income. The mother’s unpaid housework share is the percentage of hours spent on unpaid housework out of the combined total of both parents’ unpaid housework hours. Such unpaid housework includes household errands, housework, playing with children, and caring for a disabled spouse/relative (if applicable). All models control for the father’s job demand (1–7), the mother’s job demand (1–7), the father’s contract type (“causal”, “formal”), the mother’s contract type (“causal”, “formal”), the father’s age, the mother’s age, the couple’s number of children, age of the couple’s youngest child, the father’s working hour, the mother’s working hour, the father’s longstanding illness (“yes”, “no”), the mother’s longstanding illness (“yes”, “no”), the couple’s marital status (“cohabiting”, “married”), the father’s occupation status (“professional/managerial”, “others”), the mother’s occupation status (“professional/managerial”, “others”), the household income of couples, the father’s income share, and the mother’s unpaid housework share. Finally, we control for wave dummies.

Analytic strategy

We employ a dyadic analysis to examine the effects of couples’ availability of FWAs on their own and their spouses’ satisfaction with WLF among working parents while controlling for couple- and individual-specific characteristics. We adopt a linear fixed effects (FE) regression with repeated observations for couples over time to adjust for potential bias. Additionally, the two-way FE specification (including couple and time FE) is used to obtain unbiased estimates, as the explanatory variables are assumed to be independent of error terms related to the time-invariant and relevant time-varying characteristics. As the principal method for panel data analysis, FE models can effectively eliminate confounding bias from all time-invariant variables (e.g., personalities, gender role attitudes, family background) by focusing solely on within-couple variations. Given that the data are hierarchically structured (waves are nested within couples), the basic analytic model can be expressed using the following equation:

where \({{\rm{WLF}}}_{{it}}\) degree of satisfaction with WLF for the couple i at time t; \({{\rm{\alpha }}}_{{\rm{t}}}\) refers to the intercept that may vary across time; \({{\rm{\beta }}}_{1}\) is the coefficient for the key independent variable (the availability of FWAs); \({{\rm{\beta }}}_{2}\) is the coefficient for the covariates, including the job demand, contract type, age, number of children, age of youngest child, squared working hour, presence of illness, relationship status, occupation status, household income of the couples, and father’s income share, mother’s unpaid housework share, and wave dummies; \({{\rm{T}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\) refers to time fixed effects; \({{\rm{\mu }}}_{{\rm{i}}}\) refers to the time-constant error term which will be excluded during the estimation; and \({{\rm{\varepsilon }}}_{{\rm{it}}}\) refers to the time-varying error term.

To provide a broad sample picture, we first report the descriptive statistics of the analytic variables for mothers and fathers separately. Next, we examine the effect of mothers’ and fathers’ access to FWAs on their own and their spouses’ satisfaction with WLF. To further understand the moderating role of flexibility quality, we estimate the effects of the availability of FWAs by interacting it with parents’ contract type. Finally, we conduct a series of robustness checks to confirm the main results’ validity and assess the findings’ sensitivity.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the analytic variables for mothers and fathers. First, a higher percentage of fathers (59.68%) report the availability of FWAs than mothers (53.76%). Second, mothers (7.53) generally report a slightly higher level of satisfaction with WLF compared to fathers (7.32), although both groups express a relatively high level of satisfaction. Third, the results suggest that a significant majority of both mothers (81.42%) and fathers (93.42%) are formal contract workers, while a higher proportion of mothers (18.58%) are in casual work arrangements compared to fathers (6.58%). Table 2 further demonstrates that for both mothers and fathers, formal contracts are associated with greater access to flexible working arrangements. Regarding household level characteristics, among the couples referred, most (87.68%) are married while the others are in cohabiting status. In addition, the average number of dependent children is 1.91, and the mean age of the youngest child of the working parents is 8.15. In terms of gender-based housework and income division, the average share of unpaid housework undertaken by mothers is approximately 65.25%, and the average income share contributed by fathers is approximately 64.16%. In other words, working parents generally followed the traditional gender roles, where fathers are predisposed as the “breadwinner,” and mothers undertake the role of “caregiver” within the household.

Fixed effects models

Table 3 presents results from the fixed effects models on the relationships between the availability of FWAs and satisfaction with WLF among couples with children.

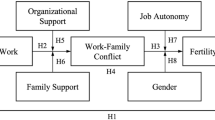

In panel A, model 1 shows that mothers’ availability of FWAs is positively associated with their own satisfaction with WLF (β = 0.77, p < 0.001), while fathers’ availability of FWAs presents no effects on their wives’ satisfaction with WLF. In model 2, it has been demonstrated that mothers’ availability of FWAs will improve their husbands’ satisfaction with WLF (β = 0.09, p < 0.05), and fathers’ availability of FWAs is positively associated with their own satisfaction with WLF (β = 0.57, p < 0.001). In other words, among working parents, while the availability of FWAs has effects on their own satisfaction with WLF, the relationship between the availability of FWAs and their spouses’ satisfaction is asymmetric. That is to say, only mothers’ availability of FWAs will affect their husbands’ satisfaction with WLF. Additionally, the spousal effect size is relatively modest compared to the direct effects on mothers’ own satisfaction with WLF. The comprehensive results of all variables used can be found in Table A2 (appendix). In panel B, the results indicate that there are no interaction effects between mothers’ and fathers’ availability of FWAs on both parents’ satisfaction with WLF. Overall, these results lend support to hypotheses 1 and 2.

Table 4 displays the results of fixed effects models exploring the interaction between couples’ availability of FWAs and their contract types in relation to satisfaction with WLF among working parents. First, when mothers have access to FWAs and are under a formal contract, their own satisfaction with WLF will significantly be improved (β = 0.24, p < 0.01). This indicates the advantages of formal contracts, which provide stability and reliability and encourage employees to utilize FWAs and benefit from them. Second, conversely, for fathers, the interaction between the availability of FWAs and contract type does not yield a significant change in satisfaction with WLF. In other words, fathers’ access to FWAs will promote their own satisfaction with WLF, regardless of the contract type or the quality of flexibility. Third, there is an asymmetric interaction between couples’ availability of FWAs and satisfaction among working parents. When mothers have formal contracts, their availability of FWAs positively influences their husbands’ satisfaction with WLF (β = 0.20, p < 0.05), while there is no such effect between fathers’ access to FWAs and their wives’ satisfaction. Figure 1 presents the aforementioned interaction effects. This implies the gendered and unequal cross-over effects for working parents within households from a couple-level perspective, meaning that mothers tend to undertake more childcare and household responsibilities, thus improving their husbands’ perceived balance between work and personal life. However, fathers who predominantly prioritize work, even under a formal contract or with high-quality flexibility, may not invest more in housework or caregiving as mothers. Thus, their availability of FWAs shows no effect on their wives’ satisfaction with WLF. Overall, these results partly support hypotheses 3 and 4 A, and lend full support to hypothesis 4B.

Robustness checks

To ensure the validity of the results, we further conduct a number of robustness checks, as shown in the appendix. First, we replicate the main models using data spanning 19 waves (2001–2019), representing circumstances before the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, work-from-home became mandatory for many employees. Post-pandemic, there is a significant increase in the availability of FWAs, even though compulsory implementation was no longer in place (Oakman et al. 2022). Similar to the main results obtained from 21 waves of data, as shown in Table A3 (appendix), both mothers’ and fathers’ access to FWAs significantly increases their own satisfaction with WLF (β = 0.78, p < 0.001; β = 0.56, p < 0.001). Furthermore, only mothers’ availability of FWAs shows improvement in their husbands’ satisfaction with WLF (β = 0.11, p < 0.05). Additionally, consistent with the main analysis, no interaction effects are observed between mothers’ and fathers’ availability of FWAs. In summary, the results remain robust when considering the pre-pandemic context.

Second, we revisit the main models using alternative measures of couples’ availability of FWAs, as discussed in the measures section. In line with the primary findings, Table A4 (appendix) reveals that when compared to couples without access to FWAs, among working parents where only the mothers have access to FWAs, only mothers’ satisfaction with WLF improves significantly (β = 0.73, p < 0.001). Similarly, among working parents where only the fathers have access to FWAs, only fathers’ satisfaction with WLF sees a notable improvement (β = 0.54, p < 0.001). Additionally, among working parents where both partners have availability of FWAs, both mothers’ and fathers’ satisfaction with WLF is significantly promoted (β = 0.76, p < 0.001; β = 0.65, p < 0.001).

Third, we re-examine the main analysis to explore variations between the availability of different FWAs. In panel A, Table A5 (appendix) illustrates that both mothers’ and fathers’ availability of flextime policy is positively associated with their own satisfaction with WLF (β = 0.83, p < 0.001; β = 0.63, p < 0.001). Additionally, only mothers’ access to this policy shows a weak association with their husbands’ satisfaction with WLF (β = 0.08, p < 0.01). In panel B, the results are consistent with the main findings. Apart from the impact of both mothers’ and fathers’ homeworking policy on their own satisfaction with WLF (β = 0.92, p < 0.001; β = 0.61, p < 0.001), only mothers’ homeworking policy enhances their husbands’ satisfaction (β = 0.18, p < 0.05). This suggests that the spousal effect of mothers’ availability of FWAs on their husbands’ satisfaction with WLF may primarily stem from the homeworking policy, enabling mothers to undertake more household and childcare responsibilities. Overall, the results demonstrate that when employing different measures of the availability of FWAs among working parents, the findings remain largely consistent, indicating the robustness of our conclusions.

Fourth, we replicate the main analysis by accounting for industry differences, as various industries may offer differing levels of access to FWAs and have distinct workplace cultures that can affect satisfaction with WLF. Based on economic activities, we categorize industries into three sectors: primary, secondary, and tertiary. The results, presented in Table A6 (appendix), are consistent with our main model, and the industry itself is not significantly associated with WLF satisfaction. Fifth, we perform the analysis without controlling for full-time/part-time employment (i.e., work hours) to rule out the potential confounding effects between access to FWAs and work hours. The results in Table A7 (appendix) align with our main model. All in all, our findings remain robust even after accounting for these confounding factors.

Discussion and conclusions

The rise of FWAs in recent years, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, is likely to reshape working parents’ satisfaction and overall well-being. FWAs are workplace alternatives that afford employees increased autonomy regarding their work time, location, etc., aiming to enhance the balance between their professional and personal lives (Chandola et al. 2019; Chung et al. 2021; Li & Wang, 2022). Our study focuses on couples with dependent children since they can more thoroughly report the intricate dynamic of their professional and personal lives. Using longitudinal couple-level dyadic data, this study contributes to the existing literature by providing a linked lives perspective to examine how couples’ availability of FWAs affects their own and their spouses’ satisfaction with WLF among working parents. Overall, there are three important findings.

First, this study significantly enriches our comprehension of the intricate dynamic between the availability of FWAs and satisfaction with WLF among working parents within the broader framework of various theoretical perspectives. Our study investigates the cross-over effects between working parents on this association. This revelation expands upon the conventional individual-centric approach found in theories like the JD-R theory, elevating the analysis beyond an individual’s work arrangements to encompass the influence of the spouse’s work situation. This extension to a dyadic viewpoint offers a more holistic understanding, encapsulating the complicated interplay of work-family dynamics. Consistent with the linked lives perspective and the work-family border theory, this research not only acknowledges but underscores the complex interconnectivity of work and family life, underscoring the necessity of incorporating both domains when evaluating WLF.

Second, by discerning and categorizing flexibility into formal and casual contracts, this study has acknowledged the unequivocal advantages of FWAs’ availability and significantly enhanced our understanding of the differential impact of the availability of FWAs on employees under various employment contexts. While we acknowledge the small sample size of fathers in casual work, this does not necessarily imply that the insignificant effect of FWAs across contract types is absent. In addition, we have observed a decline in the proportion of casual female employees, while casual employment among males has been on the rise (ABS, 2023). We anticipate that future research with larger sample sizes and more diverse contract types will shed light on more definitive interaction effects. Moreover, policymakers and organizations should prioritize the promotion of high-quality flexibility, encompassing not only the freedom to adapt work hours and locations but also the assurance of job security, stable work conditions, access to benefits, and a supportive work environment (Adamson & Roper, 2019; Kalleberg, 2000, 2012). For future research, investigating the perspectives and experiences of employees across various employment and cultural contexts could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the nuanced dynamics at play and inform tailored policy recommendations.

Third, this finding illuminates a significant mechanism contributing to the perpetuation of gender inequality within households and underscores the nuanced impact of policy measures on different genders. An intriguing finding emerges from our exploration: it is only mothers’ access to FWAs that distinctly impacts fathers’ satisfaction with WLF, particularly those under formal contracts. Nonetheless, fathers’ access to FWAs is not significantly associated with the mothers’ satisfaction. This sheds light on the intricate dynamics of household responsibilities and gendered expectations, where the burden of managing work and family often falls disproportionately on mothers (Chung & Van Der Horst, 2020; Chung & Van Der Lippe, 2020; Wang & Cheng, 2023). Moreover, the differential effect of the same policy on mothers and fathers highlights the need for policies that are consciously designed to promote gender equity within households. It emphasizes that a one-size-fits-all approach to policy-making may inadvertently reinforce gender disparities by further placing the onus of work-life balance on mothers, even with ostensibly family-friendly policies in place. Policymakers should consider these disparities and work towards creating policies that genuinely promote equality and shared responsibilities within households.

This study has several limitations, which could be potential directions for future research. Firstly, due to data constraints, it lacks measures of actual FWAs usage. This aspect may influence the impact of FWAs’ availability since employees’ uptake of these arrangements remains uncertain despite their availability. However, this limitation should not overshadow the study’s paramount contributions. The significance of FWAs’ availability on satisfaction is notable, even without data on their usage. The mere presence of FWAs signals an organization’s commitment to supporting work-life balance and employee well-being, potentially shaping employee attitudes positively. Future research utilizing more extensive data on FWAs’ adoption could explore their comprehensive effects on satisfaction more deeply. Secondly, while fixed effects models can mitigate the confounding effects of time-constant and observed time-varying variables, unobserved time-varying variables (e.g., workplace discrimination) may introduce bias. Future research could delve deeper into the nuanced effects of such variables, investigate the interaction between flexibility and evolving societal norms, and conduct longitudinal studies to assess the long-term impacts of various FWAs on employee well-being and organizational outcomes.

Thirdly, while we used methods to minimize bias, the exclusion of parents who leave paid employment may still impact the representativeness of our sample. Those who exit the workforce due to low WLF satisfaction or lack of FWAs may differ systematically from those who remain employed, potentially introducing bias. Table A8 (appendix) shows that prior low WLF satisfaction or the absence of FWAs did not significantly affect employment status, although the sample size is small. We acknowledge this as a limitation of our study. Future research could address this by using more comprehensive data to examine the lagged effects of WLF satisfaction and FWAs on employment status. Additionally, exploring the long-term effects of FWA availability on employment trajectories and the decision-making processes of parents who leave paid work would be valuable.

Taken together, our research underscores the asymmetric nature of these associations and highlights household gender inequality, while underscoring the significance of contract types. By prioritizing the availability of FWAs and promoting a culture that values work-life balance, organizations can enhance employee well-being and organizational triumph. More studies are needed to enrich our understanding and facilitate targeted policy interventions for a more equitable and inclusive work landscape.

Data availability

The data used in this study is upon request at https://melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/hilda.

References

Adamson M, Roper I (2019) Good’ jobs and ‘bad’ jobs: contemplating job quality in different contexts. Work Employ Soc 33(4):551–559. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017019855510

Anderson D, Kelliher C (2009) Flexible working and engagement: the importance of choice. Strateg HR Rev 8(2):13–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/14754390910937530

Atkinson C, Hall L (2011) Flexible working and happiness in the NHS. Empl Relat 33(2):88–105. https://doi.org/10.1108/01425451111096659

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2022) Characteristics of employment, Australia. Retrieved from https://www.abs.gov.au

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2023, August). Working arrangements. ABS. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/earnings-and-working-conditions/working-arrangements/latest-release

Bakker AB, Demerouti E (2017) Job demands–resources theory: taking stock and looking forward. J Occup Health Psychol 22(3):273–285. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056

Baxter J (2002) Patterns of change and stability in the gender division of household labour in Australia, 1986–1997. J Sociol 38(4):399–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/144078302128756750

Buswell L, Zabriskie RB, Lundberg N, Hawkins AJ (2012) The relationship between father involvement in family leisure and family functioning: the importance of daily family leisure. Leis Sci 34(2):172–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2012.652510

Chandola T, Booker CL, Kumari M, Benzeval M (2019) Are flexible work arrangements associated with lower levels of chronic stress-related biomarkers? A study of 6025 employees in the UK household longitudinal study. Sociology 53(4):779–799. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038519826014

Chesters J, Baxter J, Western M (2009) Paid and unpaid work in australian households: trends in the gender division of labour, 12(1):1986–2005

Chung H (2020) Gender, flexibility stigma and the perceived negative consequences of flexible working in the UK. Soc Indic Res 151(2):521–545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-2036-7

Chung H, Birkett H, Forbes S, Seo H (2021) Covid-19, flexible working, and implications for gender equality in the United Kingdom. Gend Soc 35(2):218–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912432211001304

Chung H, Seo H, Birkett H, Forbes S (2022) Working from home and the division of childcare and housework among dual-earner parents during the pandemic in the UK. Merits 2(4):270–292. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits2040019

Chung H, Van Der Horst M (2020) Flexible working and unpaid overtime in the UK: the role of gender, parental and occupational status. Soc Indic Res 151(2):495–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-2028-7

Chung H, Van Der Lippe T (2020) Flexible working, work–life balance, and gender equality: introduction. Soc Indic Res 151(2):365–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-2025-x

Clark SC (2000) Work/family border theory: a new theory of work/family balance. Hum Relat 53(6):747–770. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726700536001

Cooper R, Baird M (2015) Bringing the “right to request” flexible working arrangements to life: from policies to practices. Empl Relat 37(5):568–581. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-07-2014-0085

Craig L, Mullan K (2010) Parenthood, gender and work-family time in the United States, Australia, Italy, France, and Denmark. J Marriage Fam 72(5):1344–1361. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00769.x

Doan T, LaBond C, Banwell C, Timmins P, Butterworth P, Strazdins L (2022) Unencumbered and still unequal? Work hour - Health tipping points and gender inequality among older, employed Australian couples. SSM-Popul Health 18:101121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2022.101121

Doeringer PB, Piore MJ (1985) Internal labor markets and manpower analysis: with a new introduction (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003069720

Drobnič S, Beham B, Präg P (2010) Good Job, good life? Working conditions and quality of life in Europe. Soc Indic Res 99(2):205–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9586-7

Elder GH (1998) The life course as developmental theory. Child Dev 69(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06128.x

Erden Bayazit Z, Bayazit M (2019) How do flexible work arrangements alleviate work-family-conflict? The roles of flexibility i-deals and family-supportive cultures. Int J Hum Resour Manag 30(3):405–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1278615

Green C, Kler P, Leeves G (2009) Flexible contract workers in inferior jobs: reappraising the evidence. Br J Ind Relat https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8543.2009.00742.x

Hayman JR (2009) Flexible work arrangements: exploring the linkages between perceived usability of flexible work schedules and work/life balance. Comm Work Fam 12(3):327–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668800902966331

Hokke S, Bennetts SK, Crawford S, Leach L, Hackworth NJ, Strazdins L, Nguyen C, Nicholson JM, Cooklin AR (2021) Does flexible work ‘work’ in Australia? A survey of employed mothers’ and fathers’ work, family and health. Comm Work Fam 24(4):488–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2019.1704397

Hosking A, Western M (2008) The effects of non-standard employment on work—family conflict. J Sociol 44(1):5–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783307085803

International Labour Organization. (2016). Non-standard employment around the world : understanding challenges, shaping prospects (1st ed.). ILO

Johnston RM, Sheluchin A, Van Der Linden C (2020) Evidence of exacerbated gender inequality in child care obligations in Canada and Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Politics Gend 16(4):1131–1141. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X20000574

Kalleberg AL (2000) Nonstandard employment relations: part-time, temporary and contract work. Annu Rev Sociol 26(1):341–365. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.341

Kalleberg AL (2003) Flexible Firms and Labor Market Segmentation: Effects of Workplace Restructuring on Jobs and Workers. Work Occup 30(2):154–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888403251683

Kalleberg AL (2012) Job quality and precarious work: clarifications, controversies, and challenges. Work Occup 39(4):427–448. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888412460533

Kim H, Kim Y, Kim D-L (2019) Negative work–family/family–work spillover and demand for flexible work arrangements: the moderating roles of parenthood and gender. Int J Hum Resour Manag 30(3):361–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1278252

Kim M-H, Kim C, Park J-K, Kawachi I (2008) Is precarious employment damaging to self-rated health? Results of propensity score matching methods, using longitudinal data in South Korea. Soc Sci Med 67(12):1982–1994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.051

Knabe A, Schöb R, Weimann J (2016) Partnership, gender, and the well-being cost of unemployment. Soc Indic Res 129(3):1255–1275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1167-3

Krick A, Felfe J, Pischel S (2022) Health-oriented leadership as a job resource: can staff care buffer the effects of job demands on employee health and job satisfaction? J Manag Psychol 37(2):139–152. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-02-2021-0067

Govender L, Migiro SO, Alexander K (2018) Flexible work arrangements, job satisfaction and performance. J Econ Behav Stud 10(3(J):268–277. https://doi.org/10.22610/jebs.v10i3.2333

Leighton P, Painter RW (2001) Casual workers: still marginal after all these years? Empl Relat 23(1):75–93. https://doi.org/10.1108/01425450110366282

Li LZ, Wang S (2022) Do work-family initiatives improve employee mental health? Longitudinal evidence from a nationally representative cohort. J Affect Disord 297:407–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.112

Luhmann M, Weiss P, Hosoya G, Eid M (2014) Honey, I got fired! A longitudinal dyadic analysis of the effect of unemployment on life satisfaction in couples. J Personal Soc Psychol 107(1):163–180. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036394

Mai QD, Song L, Donnelly R (2023) Precarious employment and well-being: insights from the COVID-19 pandemic. Work Occup 50(1):3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/07308884221143063

Marcus J (2013) The effect of unemployment on the mental health of spouses – evidence from plant closures in Germany. J Health Econ 32(3):546–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.02.004

Masuda AD, Poelmans SAY, Allen TD, Spector PE, Lapierre LM, Cooper CL, Moreno-Velazquez I (2012) Flexible work arrangements availability and their relationship with work-to-family conflict, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions: a comparison of three country clusters. Appl Psychol 61(1):1–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2011.00453.x

McLaughlin K, Muldoon O (2014) Father identity, involvement and work–family balance: an in‐depth interview study. J Community Appl Soc Psychol 24(5):439–452. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2183

Moen P, Yu Y (2000) Effective work/life strategies: working couples, work conditions, gender, and life quality. Soc Probl 47(3):291–326. https://doi.org/10.2307/3097233

Oakman J, Kinsman N, Lambert K, Stuckey R, Graham M, Weale V (2022) Working from home in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional results from the employees working from home (EWFH) study. BMJ Open 12(4):e052733. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052733

Origo F, Pagani L (2009) Flexicurity and job satisfaction in Europe: the importance of perceived and actual job stability for well-being at work. Labour Econ 16(5):547–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2009.02.003

Pirani E, Salvini S (2015) Is temporary employment damaging to health? A longitudinal study on Italian workers. Soc Sci Med 124:121–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.11.033

Sarwar F, Panatik SA, Sukor MSM, Rusbadrol N (2021) A job demand–resource model of satisfaction with work–family balance among academic faculty: mediating roles of psychological capital, work-to-family conflict, and enrichment. SAGE Open 11(2):215824402110061. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211006142

Shockley KM, Allen TD (2007) When flexibility helps: another look at the availability of flexible work arrangements and work–family conflict. J Vocational Behav 71(3):479–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.08.006

Steckermeier LC (2021) The value of autonomy for the good life. An empirical investigation of autonomy and life satisfaction in Europe. Soc Indic Res 154(2):693–723. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02565-8

Wang S, Cheng C (2023) Opportunity or exploitation? A longitudinal dyadic analysis of flexible working arrangements and gender household labor inequality. Soc Forces, soad125. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soad125

Wang S, Kamerāde D, Burchell B, Coutts A, Balderson SU (2022) What matters more for employees’ mental health: job quality or job quantity? Camb J Econ 46(2):251–274. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/beab054

Waterhouse J, Colley L (2010) The work-life provisions of the fair work act: a compromise of stakeholder preference. Aust Bull Labour 36(2):154–177. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.221081185592563

Wheatley D (2017) Employee satisfaction and use of flexible working arrangements. Work Employ Soc 31(4):567–585. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017016631447

Whitehead DL, Korabik K, Lero DS (2008) Work-family integration: introduction and overview. In: Handbook of Work-Family Integration (pp. 3–11). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012372574-5.50004-1

Wilczyńska A, Batorski D, Sellens JT (2016) Employment flexibility and job security as determinants of job satisfaction: the case of polish knowledge workers. Soc Indic Res 126(2):633–656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0909-6

Wooden M, Warren D (2003) The characteristics of casual and fixed-term employment: evidence from the HILDA survey

Xiang N, Whitehouse G, Tomaszewski W, Martin B (2022) The benefits and penalties of formal and informal flexible working-time arrangements: evidence from a cohort study of Australian mothers. Int J Hum Resour Manag 33(14):2939–2960. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2021.1897642

Yu S, Levesque-Bristol C, Maeda Y (2018) General need for autonomy and subjective well-being: a meta-analysis of studies in the US and East Asia. J Happiness Stud 19(6):1863–1882. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9898-2

Yucel D, Chung H (2023) Working from home, work–family conflict, and the role of gender and gender role attitudes. Community Work Fam 26(2):190–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2021.1993138

Acknowledgements

Dr. Senhu Wang is funded by the Singapore Ministry of Education Tier 1 Grants (FY2022-FRC2-001, FY2024-FRC1-002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ya Guo: conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—reviewing and editing. Fenwick Feng Jing, Meng Zhu, Senhu Wang: conceptualization, writing— reviewing and editing. Yuqi Zhong: methodology, writing—reviewing and editing. Dr. Fenwick Feng Jing is the first corresponding author. Dr. Meng Zhu is the co-first author.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author(s) declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study is a secondary data analysis.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, Y., Jing, F.F., Zhong, Y. et al. Unraveling the dyadic dynamics: exploring the impact of flexible working arrangements’ availability on satisfaction with work-life flexibility among working parents. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 123 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04386-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04386-x