Abstract

Throughout modern history, animals have played a significant role in human warfare. The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) conducted extensive efforts to modify the natural behaviors of pigeons in order to enhance their utility in military operations. To enable pigeons to support communications aboard moving warships, the IJN exposed these land-dwelling birds to maritime environments, training them to endure challenging conditions such as inclement weather, extreme temperatures, long-distance sea flights, and night-time navigation. During the latter stages of World War II, as Japan faced intensified aerial bombardments, the IJN developed concealed underground pigeon lofts. This forced pigeons to adapt to subterranean environments. These experiments, driven by wartime demands, not only distorted the pigeons’ natural behaviors but also seriously compromised their health and survival. Many pigeons died during training and experimentation, while even larger numbers perished on the battlefield. Furthermore, the prolonged shortage of specialized military personnel led to inadequate care and neglect of the pigeons, resulting in the outbreak of infectious diseases and then deaths that could have been avoided among the birds. Despite advancements in military technologies, animals continue to be exploited in modern warfare, with their welfare and survival in ignorance. Reflecting on these historical lessons, it is imperative to recognize that modern warfare ethics should extend beyond human rights to encompass the welfare and protection of animals used in military operations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Throughout history, animals have played a vital role in military operations, with various nations employing horses, dogs, pigeons, and other species for strategic purposes. During World War I alone, over 16 million animals were conscripted into military service (Gardiner, 2006), underscoring the extensive scale of their involvement. With the rapid technological advancements of modern society, the range of animals used in military contexts and the scope of their deployment have significantly expanded (Webb et al., 2020; Schoon et al., 2022). For instance, marine mammals such as bottlenose dolphins and California sea lions have been trained to undertake military tasks, including ship and harbor protection, as well as mine detection and clearance (Terrill, 2001). The continuous growth of military animal experimentation (Combes, 2013; Lima et al., 2023), has raised pressing ethical concerns.

Addressing animal welfare is essential to achieving harmonious coexistence between humans and nature. Current research on animal welfare primarily focuses on the impact of human activities on both captive animals (Miller et al., 2018; O’Brien and Cronin, 2023; Rust et al., 2024) and wild animal populations (Beausoleil et al., 2018; Lindsjö et al., 2019). However, limited attention has been given to the welfare of military animals. As “frontline agents” on the battlefield, the basic physiological needs of military animals must be met to ensure effective operations. These needs include adequate nutrition, appropriate resting conditions, and balanced training regimens. Furthermore, research in fields such as zoology, veterinary science, and neuroscience has revealed that certain animals can experience emotions (Soltis et al., 2009; de Vere and Kuczaj, 2016; Zych and Gogolla, 2021; Zimmermann et al., 2024). Emotional well-being is now recognized as a fundamental element in the holistic assessment of animal welfare as well (Boissy et al., 2007).

Among military animals, the military pigeon is a particularly significant species. Historically, carrier pigeons were bred for communication purposes, utilizing their homing instincts to ensure their return to their mates. Over time, these carrier pigeons were transformed into military pigeons, specifically trained for military communications. Throughout modern warfare, military pigeons have played vital roles, particularly during World War I, the Spanish-American War, and the Franco-Prussian War. Following World War I, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) recognized the strategic value of military pigeons and actively pursued research and experimentation to enhance their utility. Culver (2022) notes that during post-World War I Japan, both military and civilian sectors exhibited considerable militarized violence in the capture, handling, and treatment of pigeons and other birds in the course of these activities.

The historiography on Japanese military pigeons remains limited, with much of the existing scholarship focusing on the use of military pigeons by British and American communication units during World War I (Snyders, 2015; Phillips, 2018; Jia, 2021). These studies differ from the present paper in both temporal and spatial focus, as well as in their emphasis on the role and symbolic image of military pigeons. By contrast, this study centers on the training and experimental modification of military pigeon behavior within the IJN context. Within Japanese academia, most research on military animals has concentrated on the amenities provided for their welfare (Hata, 2007), while research on military pigeons remains scarce. Although some studies have touched on the early use of military pigeons by the Imperial Japanese Army (Yanagisawa, 2011), there has been no systematic analysis of military pigeons in the IJN.

By focusing on the case of military pigeons in the IJN, this paper addresses a critical gap in the literature on war and animal protection. It highlights how military institutions historically exploited animal behavior to achieve strategic objectives, raising ethical questions about the treatment of animals during wartime. By illuminating this underexplored case, the study provides a foundation for broader discussions on the ethical treatment of animals in military and security operations. It also contributes to ongoing debates about animal welfare in modern warfare, calling for a reassessment of military practices and policy guidelines aimed at ensuring the humane treatment of animals used in combat and related activities.

Maritime pigeon

In 1919, the Japanese military launched a comprehensive research initiative into military pigeons. As a result, several naval fleets established dedicated pigeon lofts, training these birds for maritime communication duties (Hikosakae, 1921, pp. 997–1000). During this period, IJN seaplanes routinely embarked on missions carrying military pigeons, which were deployed in emergencies to signal for aid (Commanding Officers of Yokosuka Garrison, 1933, p. 251). This practice was enabled by the relatively low speed and open cockpits of the seaplanes, allowing the pigeons to be released at any moment to report on the situation (Navy Ministry, 1927a, p. 938). The communicative benefits of employing pigeons were evident: seaplanes could quickly transmit information regarding enemy positions to the flagship via pigeons, expediting communication compared to waiting for the plane’s return.

Weather prediction experiment and extreme weather drill

Accurate meteorological information is crucial for naval operations due to their heavy reliance on weather conditions. In January 1935, the IJN conducted a 2-month observation of military pigeons, monitoring their flight performance under various weather conditions (see Table 1).

The experimental results presented in Table 1 suggest that military pigeons can support meteorological observations and serve as a supplementary method for weather monitoring at sea. This indicates that maintaining military pigeons aboard warships provided the Navy with several operational advantages.

Although keeping military pigeons at sea offered clear benefits, these birds were not naturally suited for oceanic flights. Their performance was particularly hindered by adverse weather conditions, such as heavy rain, which impaired their vision and disrupted their navigational abilities. When their visual capacity was compromised, pigeons became less active and, in some cases, exhibited signs of fear (Commanding Officers of Yokusuka Garrison, 1933, p. 524). Moreover, while pigeons’ feathers are naturally waterproof, prolonged exposure to heavy rain could cause water to seep into their wings, significantly impairing flight performance. In extreme cases, pigeons risked disorientation or even death during flight.

Recognizing the challenges posed by weather, the IJN maintained that humans cannot control the weather, while they trained pigeons to withstand harsh weather conditions. To enhance pigeons’ communication abilities in adverse weather like rain, snow, fog, and wind, the IJN implemented a progressive training regimen, advancing from simple to more complex exercises (Imperial Japanese Navy, 1935c, p. 759). As the training progressed, pigeons were gradually conditioned to perform outdoor flight operations in light rain, snow, and strong winds. This training not only improved the pigeons’ adaptability to harsh weather but also enhanced their homing capabilities. Furthermore, this rigorous training program was largely unaffected by adverse weather conditions (Navy Ministry, 1927f, p. 1165). Evidence of this approach is found in pigeon training records, which state: “To tame stronger military pigeons, daytime training should proceed as usual, even in bad weather” (Commanding Officers of Yokusuka Naval District, 1935, p. 1019), and “For short-distance release training, only extreme weather, such as exceptionally heavy snow, rain, fog, or windstorms, poses significant obstacles to the pigeons’ homing ability” (Imperial Japanese Navy, 1933a, 1933b, p. 822).

Under the IJN’s rigorous training program, military pigeons successfully executed communication missions in a variety of challenging scenarios. As shown in Table 2, the IJN’s animal trials, which required pigeons to return to their nests under adverse weather conditions, achieved notable success. However, the demands of long-distance flights and harsh training environments inevitably impacted the pigeons’ physical health and psychological well-being.

Cold-resistant and heat-resistant training

During wartime, the IJN’s operations spanned a vast area, covering nearly the entire northern hemisphere. Its scope extended from Siberia in the north to the southernmost reaches of the Pacific Ocean. To maintain reliable communication, it was essential to provide specialized training for military pigeons. Not only in temperate marine regions, but also in extreme cold and hot environments. A 1925 IJN survey reported that their military pigeons were able to fulfill their communication duties in both the intense heat of the Southern Ocean and the extreme cold of Birtheria and Siberia (Navy Ministry, 1927a, p. 933). However, the reality is that the homing ability of pigeons varies depending on the geographical environment in which they are trained.

Table 3 highlights that temperate regions provide the optimal environment for pigeon activity. Pigeons adapted to temperate conditions often experience stunted growth, diminished flight performance, and reduced homing capabilities when relocated to tropical or frigid zones (Navy Ministry, 1927d, p. 1119). Neither tropical nor frigid climates are conducive to the survival and operational performance of pigeons.

In tropical regions, pigeons are particularly vulnerable to infectious diseases such as “pigeon pox” and “diphtheria,” which can spread rapidly throughout a loft within days due to the hot, humid, rainy, and insect-infested conditions. In 1935, an outbreak of “diphtheria” severely affected two IJN battalions. Despite emergency containment measures, the disease claimed the lives of 80 pigeons in one unit, while 70% of the pigeons in the other unit perished. In response, the IJN incinerated the deceased pigeons to prevent further spread. A follow-up investigation revealed that the pigeon lofts in these units were poorly constructed, with insufficient lighting, inadequate ventilation, water leakage during continuous rainfall, and unsanitary conditions. The persistent humidity, compounded by ongoing rainfall, created an ideal environment for the spread of disease (Imperial Japanese Navy, 1935d, p. 851).

Young pigeons raised in tropical climates frequently experienced growth stunting, maturing approximately a month later than those raised in temperate regions. Their feathers were typically lighter in color, duller, less resilient, and their flight capabilities were noticeably weaker (Navy Ministry, 1927d, p. 1123). Additionally, because pigeons lack sweat glands, they rely on evaporative cooling through their skin and breathing. As a result, they were more susceptible to respiratory illnesses, such as “pigeon rhinitis,” in excessively high temperatures (Ad Hoc Military Investigations Committee, 1919, p. 36).

In cold climates, extreme weather conditions, such as wind and snowstorms, impaired pigeons’ vision and significantly hindered their navigational abilities. Many pigeons became disoriented and ultimately died from exposure, as they had no access to resting places, food, or water (Navy Ministry, 1927d, p. 1129). To sustain flights and provide hydration during missions, the IJN attempted to train pigeons to drink melted snow. Experiments conducted in 1926 on the warships Wakamiya and Kasuga involved training pigeons to consume snow, with the aim of reducing mission durations (Navy Ministry, 1927d, p. 1132). However, exposure to cold weather posed significant risks to the pigeons’ respiratory and digestive systems. Furthermore, cold and wind slowed the development of young pigeons, and those born during winter often did not survive beyond 10 to 15 days (Navy Ministry, 1927d, p. 1130).

In summary, the physiological impacts of environmental conditions on military pigeons were so detrimental that the training regimen failed to achieve its anticipated outcomes.

Long-distance flight training at sea

Training pigeons for maritime operations posed significant challenges due to their natural status as terrestrial creatures with physiological traits ill-suited for sustained flight over water. At the time, the IJN believed that pigeons relied on a “sixth sense” for homing, making intuitive navigational decisions based on visual confirmation of terrain and memory associations. Consequently, topography played a vital role in their ability to navigate (Navy Ministry, 1927b, p. 976). However, at sea, the accuracy of pigeons’ homing abilities was substantially reduced, as the birds had only waves to observe and minimal landscape features to memorize. Furthermore, the scarcity of islands in the open ocean limited opportunities for pigeons to rest, recover from wing fatigue or sustain long-distance flights. As naturally terrestrial animals, pigeons also exhibited an inherent fear of water (Navy Ministry, 1927b, p. 976). Flight test results revealed that pigeons were poorly adapted for sea-based operations. Undeterred by these obstacles, the IJN sought to improve pigeons’ maritime flight performance through intensive training, conducting targeted exercises across various naval fleets and documenting their findings (as shown in Tables 4 and 5).

In 1927, the IJN summarized the successful sea flight of military pigeons periodically, and the detailed data is in Tables 6 and 7.

Table 6 shows that Japanese pigeons were capable of supporting military communications over distances of up to 600 kilometers and civilian communications up to 1000 kilometers. However, for coastal military pigeons, the range was reduced to 358 kilometers on land and only 300 kilometers at sea. Table 7 further reveals that the homing success rate for pigeons released at sea was significantly lower than that of pigeons released on land, with the latter achieving a near 100% return rate. Overall, the performance of military pigeons in maritime communication was inferior to that in coastal communication, and both were considerably weaker compared to their performance in land-based communication.

Despite the IJN’s extensive experiments to establish maritime communication using military pigeons, the results fell short of expectations. The IJN concluded that pigeons were unsuitable for long-distance maritime communications, citing the disappointing experimental outcomes and the widespread use of naval pigeons in other Western nations primarily for inter-coastal communication. In February 1929, the IJN officially decided to limit the use of pigeons to an auxiliary communication role for coastal port defense forces (Navy Ministry, 1942, p. 1036). The experiments involving marine communication with pigeons were largely discontinued.

Nocturnal pigeon training

Although maritime military pigeon communication experiments were temporarily halted, research on military pigeons for port defense continued. As previously noted, military communications require flexibility in both timing and location, necessitating the ability to transmit messages at any hour of the day or night. To meet this need, in May 1924, the IJN initiated a program to breed nocturnal pigeons (Mitsumasa Yonai, 1936, pp. 373–374).

Training pigeons for night flight, however, proved to be a formidable challenge. The IJN’s research identified three key reasons why pigeons were naturally unsuited for nocturnal activity. First, like most birds, pigeons are diurnal, meaning they are active during the day and rest at night, rendering them lethargic after dark. Second, pigeons lack the visual acuity required for night-time flight, increasing their susceptibility to accidents. Third, pigeons are naturally timid and reluctant to leave their nests at night. In especially tranquil environments, even the slightest contact, a touch from a hand or fingertip for example, could startle them, triggering a defensive reaction (Imperial Japanese Navy, 1933a, 1933b, p. 805).

Mandatory mental flight training

In response to the first and third challenges associated with nocturnal flight, the IJN conducted a series of experiments with diurnal pigeons in 1933. The experimental procedures and results are presented in Fig. 1.

The experiments revealed that the primary reason diurnal pigeons struggled to return home at night, even over short distances, was insufficient energy. To address this issue, the IJN developed key strategies to strengthen the pigeons’ motivation to fly at night (see Table 8).

Table 8 outlines the IJN’s phased training strategy aimed at enhancing the pigeons’ ability and willingness to engage in nocturnal flight. As part of this strategy, young and robust pigeons aged 1–3 months were selected from lofts equipped with night vision systems. While 2-year-old pigeons could be trained for night flight, the process was time-consuming and less effective. Pigeons older than 3 years were able to adapt to nocturnal flying only with considerable difficulty.

The training regimen began with flights in the morning and evening, gradually advancing to flights just before sunrise and after sunset. After approximately 1 month, the pigeons were trained to fly at night. Training was considered complete once the pigeons were able to circle above the lofts for more than 40 min. Those that met the training criteria were released from a short distance of about one kilometer. Over time, the release times were progressively adjusted, allowing the pigeons to gain experience flying at night (Navy Ministry, 1927g, pp. 1330–1331). This stepwise approach reduced the pigeons’ nocturnal apprehension, bolstered their inclination to fly, and ultimately instilled the habit of nocturnal flight.

Terrain memory training

To address the second challenge, the IJN focused on enhancing military pigeons’ proficiency in nocturnal navigation, with an emphasis on memory and obstacle avoidance. As previously noted, pigeons possess remarkable visual recall and associative abilities, which are essential for homing. During high-altitude circling flights, the IJN observed that pigeons could quickly identify light sources within a 1-kilometer radius, such as streetlights or candles, and commit them to memory. Pigeons could retain this visual information for several months and, in familiar terrain, for several years (Imperial Japanese Navy, 1933a, p. 776).

After a series of experiments, the IJN concluded that while pigeons do not possess strong night vision, they are not entirely blind at night. Their night vision is comparable to that of humans, depending on the brightness of the available light. However, pigeons have an advantage over humans when in flight, as their wider field of view allows them to see more clearly in low-light conditions.

As illustrated in Fig. 2, with Point A as the loft and Point D as the release point, military pigeons typically navigate the path D-C-B-A when homing (Imperial Japanese Navy, 1933a, 1933b, p. 802). However, they can also be trained to follow the alternative route D-E-F-B-A. With sufficient training, pigeons can accurately navigate this route, even when released hundreds of kilometers away along a familiar training path. Nevertheless, most pigeons struggle to home effectively when released over 100 kilometers in the opposite direction. Observations of daily out-of-loft flights were limited to distances of 50 kilometers or less, as experiments beyond this threshold were deemed unreliable (Imperial Japanese Navy, 1935a, p. 679).

The IJN was confident that pigeons could achieve night-time homing by identifying and memorizing the lights or outlines of landmarks, such as city streets, villages, coastlines, and fishing boats (Commanding Officers of Yokusuka Naval District, 1932, pp. 468–469). To develop this capability, trainers subjected the pigeons to continuous training. During the day, pigeons observed and memorized ground objects so they could recognize them in low-light conditions at night. As a result, the pigeons eventually became capable of navigating their homing routes even in dim environments (Imperial Japanese Navy, 1935b, p. 703).

The extensive training efforts yielded tangible results. In the “Military Pigeon Research Report Appendix III” submitted in 1927, the IJN reported: “The trained pigeons, after research and analysis, have a communication range of about 100 kilometers. And their speed and ability in night flight are comparable to those of daytime communication pigeons. Night communication pigeons achieve these impressive homing results because of the repeated training that familiarizes them with the terrain, rendering them highly adept at daytime homing” (Navy Ministry, 1927c, p. 1106).

Obstacle avoidance training

Pigeons have not evolved to see well in the dark, which increases their risk of accidents during nocturnal flights compared to daytime flights. During night flights, pigeons must navigate various obstacles, but their diminished sensory perception in darkness often leaves them unable to avoid collisions. Training records reveal that pigeons frequently collide with electric wires and other objects during night flights and homing exercises. As a result, frequent night flight training has led to the discovery of deceased pigeons in various locations (Navy Ministry, 1933, p. 805).

To reduce the risk of collisions, the IJN implemented a stepwise training approach to improve pigeons’ obstacle avoidance abilities. Initially, pigeons were released in environments with simple overhead structures, such as trees or basic cables. As training advanced, the level of complexity was gradually increased by introducing more intricate overhead cable arrangements. Training sessions progressed from daytime to twilight and dawn (Imperial Japanese Navy, 1935b, p. 724). This process underscores the significant physical and cognitive demands placed on pigeons during nocturnal flight training.

Breeding experiments for nocturnal pigeons

Like other selective breeding processes, the training of nocturnal pigeons involved the harsh elimination of unsuitable candidates. Trainers typically selected healthy pigeons aged 2 to 3 months, as night flights placed greater physical demands on the birds. Military pigeons aged between 6 months and nearly 2 years required an extended training period to adapt to nocturnal flight. Pigeons older than 2 years were generally deemed unsuitable for night flight training due to their age and reduced flight adaptability (Imperial Japanese Navy, 1933a, 1933b, p. 814). The initial training phase lasted approximately 1 month, during which pigeons were prepared for round-the-clock flight capabilities (Navy Ministry, 1927c, p. 1100). Pigeons that failed to meet performance standards during this period were culled from the training program.

The IJN likened nocturnal pigeons to “athletes,” emphasizing their need for exceptional vitality and physical endurance (Navy Ministry, 1933, p. 815). Flight records from a 3-year-old nocturnal pigeon bred by the Yokosuka Garrison in October 1932 show that it flew exclusively at night, completing 383 flights over a cumulative distance of 7,220 kilometers. This demonstrates that nocturnal pigeons endure a significantly heavier workload than their daytime counterparts, as they are required to fly both day and night. The intense training regimen placed considerable strain on the pigeons, and excessive demands sometimes led to their disappearance (Commanding Officers of Yokusuka Naval District, 1932, p. 466).

A decline in the military pigeon population posed a serious threat to the communication capabilities of naval units. To mitigate this issue, the IJN implemented artificial breeding measures aimed at improving reproductive efficiency and alleviating the adverse effects of breeding fatigue on the pigeons’ flight performance. These measures helped reduce the excessive workload placed on nocturnal pigeons and lowered the high attrition and culling rates.

For nocturnal pigeons, flight training typically occurred from April through November, while breeding was conducted in December after training. Male and female pigeons were generally separated in December or January, with mating taking place in February during the estrus period. This schedule allowed trainers to better manage the breeding process and produce healthy offspring with consistent birth periods. Given the constant communication demands placed on nocturnal pigeons, they faced significant physical burdens. To prevent breeding-related exhaustion, trainers frequently implemented birth control measures and artificially regulated the pigeons’ breeding cycles.

Nurturing of young pigeons commenced after mating, with female pigeons forming bonds with their chicks approximately 1 week after hatching. Male and female pigeons alternated in keeping the chicks warm under their wings. However, once the youngest pigeons were old enough to leave the nest, the mother was moved to prepare for the next laying, abruptly ending the brooding phase. This practice minimized the time young pigeons spent in the nest but also disrupted the natural brood-rearing process. The suppression of pigeons’ innate mating instincts and the enforced separation of parent and offspring exemplified the anthropocentric nature of human intervention.

Years of research culminated in the publication of The Breeding Method of Nocturnal Pigeons in November 1932, authored by an IJN ensign. This document detailed significant advancements in the performance of nocturnal pigeons, highlighting their near-perfect communication accuracy during late-night flights and their capacity to function during both day and night (Imperial Japanese Navy, 1935a, p. 697). The IJN’s chief executive praised these achievements, remarking, “The IJN has made great progress in the research of night-flying pigeons” and “This is a major breakthrough for military pigeon research, as pigeons are becoming increasingly important as a unique lightweight communications system” (Imperial Japanese Navy, 1933a, p. 764). Through extensive human intervention, traditionally diurnal pigeons were successfully trained to become “nocturnal pigeons” capable of flying in complete darkness.

Pigeons in underground bunkers

In the final stages of World War II, Japan formulated a plan for “decisive homeland battle.” The Japanese military began constructing underground bunkers to protect people and facilities from American airstrikes. These bunkers were expansive and complex, with some, like the 5,000-square-meter bunker in Ofuna-cho, Kamakura-gun, Kanagawa Prefecture, housing essential facilities such as printing factories. Given the frequent damage to cable and wireless connections caused by airstrikes, military pigeon communication emerged as a practical and reliable alternative.

On November 11, 1944, the Ministry of the Navy issued the Basis for Preparation of Coastal Preparedness Plans. The plan specified that “Police communications should primarily defend the existing network, complemented by establishing a transmission beacon signal system and a military pigeon communication system in remote areas, to augment existing wireless communications” (Army Ministry, 1944, p. 204). This directive underscored the vital role of military pigeon communication in scenarios where scientific communication systems were compromised or where surprise attacks occurred in remote areas. On June 28, 1945, the Commanding Officers of Yokosuka Garrison proposed the construction of pigeon lofts in underground bunkers to support communications. Military pigeons were deemed essential for clandestine communication, as wireless communication systems were vulnerable to interception, particularly during intense combat or in isolated areas (Fujimoto, 2021, pp. 422–443).

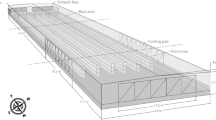

The IJN implemented an innovative system for housing pigeons in underground bunkers. Each bunker featured a small pipe that protruded to the surface, allowing pigeons to enter and exit the loft. The pipe was cleverly concealed in bushes or underbrush, making it nearly undetectable, which is a world-first technique in military communications (Fujimoto, 2021, p. 443). Toward the end of the war, these subterranean pigeon lofts, referred to as “bunker pigeons” or “trench pigeons,” were established across Japan as a response to ongoing air raids.

However, confining pigeons to underground bunkers for extended periods had detrimental effects on their health and well-being. Ideally, pigeon lofts should be located on high ground with dry, well-ventilated environments and an expansive, quiet view to support healthy growth and development. In contrast, the cramped and enclosed spaces of underground bunkers posed significant challenges for pigeon health. Proper ventilation, lighting, and hygiene were difficult to maintain, and the humid, poorly ventilated environment of bunkers created conditions conducive to the spread of infectious diseases such as “diphtheria,” resulting in significant mortality among pigeon flocks (Imperial Japanese Navy, 1933b, p. 854).

In summary, while housing pigeons in underground bunkers appeared to protect them from bombardment, it also forced them to endure an unnatural environment that compromised their well-being. This practice underscores the ethical issue of involving animals in human conflicts.

Collateral damage from the pigeon experiments

The military experiments on pigeons, whether successful or not, generated a range of issues for the IJN. The most significant of these was the high rate of pigeon attrition, which placed a substantial logistical burden on operations and directly affected the welfare of the pigeons.

Attrition problem

As previously noted, military pigeon experiments resulted in high attrition rates, with many pigeons being eliminated during training, experimental failures, or the breeding process. Despite rigorous selection and extensive breeding efforts, pigeons were quickly lost once deployed in the field of battle.

The loss of a pigeon in combat had implications beyond the death of the bird itself. As carrier pigeons rely on their homing instinct, which is often linked to their bond with a mate. A mated pigeon is more likely to return home than an unmated one. Consequently, military pigeons were frequently deployed in pairs. When one pigeon was lost, its mate’s performance declined, and even if the surviving pigeon mated again, its effectiveness was diminished. Research from 1927 revealed that military pigeons, especially males, exhibited strong territorial instincts and adhered to a monogamous system, making it difficult for them to change nests or mates. As a result, the death of one pigeon effectively rendered its mate ineffective, doubling the operational cost of each loss (Navy Ministry, 1927g, p. 1363).

The high attrition rate remained a persistent problem for the IJN, prompting the establishment of four pigeon incubation centers overseas to sustain the pigeon population. In November 1925, a report outlined the protocols for deploying military pigeons aboard warships and aircraft (see Table 9).

As shown in Table 9, only two to six military pigeons were typically carried by airplanes or hot-air balloons on each mission. While the military pigeons required time to rest and recover after each mission. Given the need for continuous 24-h emergency communications, a shift system was implemented to ensure communication availability at all times. This meant that for every pigeon carried into combat, an equivalent number of reserve pigeons had to be maintained aboard the mother ship or naval station. Aircraft, which were more frequently engaged in reconnaissance missions, required an even larger number of pigeons to maintain a three-shift rotation system. It is important to note that the 50 or 100 military pigeons allocated to each ship, as outlined in Table 9, referred specifically to the pigeons had passed the screening process. The IJN had to manage and train far more pigeons than the official quotas suggested.

According to IJN reports, it took 3 to 6 months to train 100 pigeons capable of completing a 300-kilometer flight. Given a culling rate of approximately 60%, this required an initial pool of about 250 untrained, high-quality adult pigeons (Navy Ministry, 1927f, p. 1195). Moreover, wartime deployments of military pigeons inevitably increased in response to mission demands, environmental conditions, and other variables, often requiring a 40–50% increase in the pigeon population (Navy Ministry, 1927e, pp. 1141–1151). As previous experiments had shown that the accuracy of a single pigeon completing a communication mission—defined as the probability of the pigeon successfully returning to its nest—was around 70%. The release of multiple pigeons simultaneously significantly improved communication accuracy. This necessity for greater communication reliability justified the practice of carrying multiple pigeons aboard aircraft and stockpiling pigeons at rear bases. As a result, the need for larger pigeon populations placed immense pressure on the breeding, training, and management of military pigeons.

Logistical pressure

Maintaining military pigeons required significant logistical support for breeding, feeding, training, and daily care. According to reports, large dismantled lofts on warships and aircraft carriers, each with a capacity of 100 pigeons, were staffed by one non-commissioned officer, one petty officer, and two soldiers. Smaller lofts on smaller ships, which could house 50 pigeons, were managed by one non-commissioned officer and two petty officers or soldiers. Land-based lofts within naval bases were staffed with two non-commissioned officers or soldiers for every 50 pigeons. Additionally, for every group of more than three lofts, an extra petty officer was assigned to oversee breeding operations. Lofts that housed nocturnal pigeons required a minimum of two full-time petty officers or soldiers for their management.

The number of personnel aboard IJN ships was relatively fixed, with crew members assigned specific duties, leaving little room for redundancy. Introducing military pigeon breeding aboard ships necessitated the allocation of personnel specifically for this task, further straining the already limited human resources. Moreover, since pigeon lofts were situated on the open deck, they occupied valuable deck space and required regular cleaning and maintenance. These factors intensified the logistical burden on the crew.

Additionally, military pigeons were often viewed as a secondary, less important communication method compared to wireless systems. For example, in December 1924, the director of military pigeon research on the Vajra ship was frustrated with his role as a part-time director, as he was simultaneously responsible for his primary duties as “sub-captain of Fort Barbette.” His responsibilities left him with insufficient time to train soldiers assigned to pigeon care. While the Air Force had an official title of “Director of Pigeon Research,” the fleet used the title “Petty Officer in Charge of Pigeons,” a designation with little formal recognition. This informal status contributed to neglect in pigeon care, as soldiers responsible for the pigeons were also preoccupied with daily training and guard duties (Commanding Officers of Ichikawa Yokosuka Naval Air Force, 1924, pp. 1930–1934). Furthermore, although the Committee on Military Pigeon Investigation directed divisions to dispatch personnel for training in pigeon management, most of those assigned were older, less physically fit soldiers with respiratory issues. This reflects the broader perception of military pigeon care as a low-priority, menial duty.

The training of pigeon trainers was equally challenging. It took approximately 1 year to complete a standard training cycle for pigeon trainers, and it typically required 2 years for a soldier to achieve proficiency in pigeon handling (Navy Ministry, 1927a, p. 958). Given the limited accommodation on warships, it was impractical to recruit and train personnel on board. As a result, the pace of developing qualified pigeon specialists failed to meet operational demand, further intensifying the logistical burden.

The shortage of trained personnel had a direct impact on the daily care and management of pigeons, particularly with regard to disease control. As previously noted, an outbreak of diphtheria within a flock caused numerous fatalities, even though emergency measures were eventually implemented to control the spread. Pigeons are particularly vulnerable to this infectious disease, and two possible explanations have been proposed for the outbreak. First, it is possible that inspections were not conducted thoroughly the previous month, allowing sick birds to remain undetected. Second, infected pigeons may have been introduced via new deliveries that quarantine officers failed to detect. If the first scenario is true, it points to a lack of experience and knowledge among personnel responsible for pigeon care. If the second scenario is accurate, it highlights inadequacies in the pigeon management system, particularly in quarantine and transportation protocols. Regardless of the cause, both scenarios reflect a lack of professionalism among relevant personnel, contributing to disease outbreaks among military pigeons.

In addition to manpower challenges, the material resources required for pigeon care also posed a significant burden. By 1944, as the IJN faced mounting strain from the war effort, logistical constraints began to affect the supply of essential pigeon feed. The amount of corn and oyster crumbs allocated per pigeon was reduced by 5 grams and 1 gram, respectively, and substitute feeds were introduced (Hideki, 1944, p. 144). Even the mandatory salt supplement crucial for addressing nutritional deficiencies, supporting digestion, and preventing disease was rationed on a case-by-case basis. After just 3 months, the supply of salt could no longer be guaranteed, and rations were further reduced or substituted. These shortages highlight the severe logistical pressures faced by the IJN in maintaining military pigeons.

In summary, the IJN’s failure to cultivate a sufficient number of skilled pigeon trainers, combined with a scarcity of essential material resources, led to substandard care for military pigeons. This mismanagement ultimately compromised pigeon welfare, as the shortage of both human and material resources made it impossible to maintain optimal living conditions for the birds.

Conclusion

Military pigeon communication, as a tactical method of communication, offered unique advantages that addressed the limitations of conventional systems. Accordingly, the IJN conducted extensive experiments and initiatives involving pigeons, including sea flight training, night flight training, and the deployment of underground “bunker pigeons.” These initiatives produced mixed results. Regardless of their success or failure, the pigeons were subjected to harsh training regimens designed to fundamentally alter their natural behaviors. The demands of wartime operations, combined with rigorous daily training and the chaos of battle, resulted in high mortality rates among military pigeons. To sustain operations, the IJN required a substantial reserve of pigeons, which placed significant pressure on manpower and material resources, increased logistical demands, and ultimately compromised the welfare of the pigeons.

While the use of military animals may not have been viewed as problematic in an era where all resources were mobilized for war, a contemporary re-examination reveals the underlying anthropocentric logic that governed such practices. Pigeons, traditionally seen as symbols of peace and freedom, were coerced into serving as “soldiers” and “spies” for military purposes. This practice highlights the paradoxes and moral contradictions present in the IJN’s use of military pigeons.

The repercussions of war extend beyond human suffering, as animals also bear the brunt of armed conflict. Research has shown that military animals often exhibit distinct emotional traits (Swart, 2010). A comprehensive history of war cannot be written without acknowledging the experiences of animals involved in military operations. Even animals that do not directly participate in combat may be indirectly affected, losing their habitats and living spaces due to the destruction caused by warfare. Between 1969 and 1989, military conflicts in South Africa led to the deaths of thousands of elephants in Angola and the Caprivi Strip as a result of demand for their tusks and meat (Chase and Griffin, 2009).

More recently, Tedla et al. (2023) examined the impact of armed conflict on animal welfare in the Tigray region of Ethiopia. Their findings revealed that animals had no means of escaping the initial outbreak of violence, and even if they survived, many were unable to return to their familiar natural habitats after the conflict ended. The Russia-Ukraine war similarly resulted in significant ecological harm, including the deaths of approximately 50,000 dolphins and the abandonment of thousands of cattle and sheep due to the Red Sea crisis (Naylor, 2023; Whiteman, 2024). Moreover, environmental destruction in war zones has forced wild animals, including raccoons and dolphins, to enter active conflict areas. Data from the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) indicate that collateral damage from the Russia-Ukraine conflict threatens to disrupt biodiversity and ecosystems across the Eastern European Plain (IFAW, 2022).

The impact of armed conflict on wildlife, domesticated animals, and even zoo animals is undeniable. Reflecting on the history of Japanese military pigeons allows for a broader discussion on the use of animals in warfare and highlights the harmful effects of modern armed conflict on animal welfare. In contemporary conflicts, attention should be paid not only to human rights but also to the survival and welfare of animals.

To address these issues, animals involved in warfare should be included within the scope of international humanitarian law (Nowrot, 2015). First, governments should strive to minimize the use of military animals in combat. When the use of animals, such as military dogs, is deemed necessary, measures should be taken to protect their welfare during training and operations. Governments must adhere to the principles of humanitarianism and animal protection, comply with international treaties, and avoid targeting zoos and natural habitats or engaging in combat within animal territories.

Second, animal-related organizations, such as zoos, ranches, and rescue stations, should prioritize relocating animals under their care during conflicts and wars to prevent casualties. If relocation is not feasible, particularly for large or aggressive animals in zoos or laboratory animals, efforts should be made to handle them humanely and minimize their suffering.

Finally, the public has a role to play in promoting animal welfare during both peacetime and wartime. Advocacy against the involvement of animals in war can raise awareness of their plight. During times of conflict, individuals should also strive to care for and protect animals in their vicinity. These collective efforts will contribute to the harmonious coexistence of humans and animals, support the sustainable development of society, and preserve a healthy environment for future generations.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Ad Hoc Military Investigations Committee (1919) Single book, Luk Yi 74, British Bukitsu military use of military curves.「単行書・陸乙七四・英仏軍ノ軍用鳩ニ就テ」. Ref. A04017276400. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), Tokyo. Available via https://www.digital.archives.go.jp/img/673345

Army Ministry (1944) Standards for setting up a coast guard plan/facility development for the 4th Guard.「沿岸警備計画設定上の基準/ 第4 警備の為の施設整備」. Ref. C14010639200. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), Tokyo. Available via https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/C14010639200

Beausoleil NJ, Mellor DJ, Baker L, Baker SE, Bellio M, Clarke AS, Dale A, Garlick S, Jones B, Harvey A, Pitcher BJ, Sherwen S, Stockin KA, Zito S (2018) “Feelings and fitness” not “feelings or fitness”—the raison d'être of conservation welfare, which aligns conservation and animal welfare objectives. Front Vet Sci 5:296

Boissy A, Manteuffel G, Jensen MB, Moe RO, Spruijt B, Keeling LJ, Winckler C, Forkman B, Dimitrov I, Langbein J, Bakken M, Veissier I, Aubert A (2007) Assessment of positive emotions in animals to improve their welfare. Physiol Behav 92:375–397

Chase MJ, Griffin CR (2009) Elephants caught in the middle: impacts of war, fences and people on elephant distribution and abundance in the Caprivi Strip, Namibia. Afr J Ecol 47:223–233

Combes RD (2013) A critical review of anaesthetised animal models and alternatives for military research, testing and training, with a focus on blast damage, haemorrhage and resuscitation. Altern Lab Anim 41:385–415

Commanding Officers of Ichikawa Yokosuka Naval Air Force (1924) Military doves (1).「軍用鳩 (2) 」. Ref. C08051173600. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), Tokyo. Available via https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/C08051173600

Commanding Officers of Yokusuka Garrison (1933) Military pigeon (1).「軍鳩 (1) 」. Ref. C05023283300. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), Tokyo. Available via https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/C05023283300

Commanding Officers of Yokusuka Naval District (1932) 7.12.1 Research experiment results report (1).「7. 12. 1 研究実験成績報告の件 (1) 」. Ref. C05022428300. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), Tokyo. Available via https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/C05022428300

Commanding Officers of Yokusuka Naval District (1935a) Yokochin confidential no. 37-3-17910.5.14 military pigeon research experiment results report progress (1).「横鎮機密第37の3号の17910. 5. 14 軍鳩研究実験成績報告進達 (1) 」. Ref. C05034610300. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), Tokyo. Available via https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/C05034610300

Culver AA (2022) Japan’s empire of birds: aristocrats, Anglo-Americans, and transwar ornithology. Bloomsbury, London

de Vere AJ, Kuczaj SA (2016) Where are we in the study of animal emotions? Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci 7:354–362

Fujimoto T (2021) Chronology of Japanese military doves 6. Kijibato, Japan

Gardiner J (2006) The animals’ war: animals in wartime from the First World War to the present day. Portrait, London

Hata I (2007) War history of military animals.「軍用動物たちの戦争史」. Mil Hist 43:50–72

Hideki T (1944) Rules for the management of doves.「軍鳩管理規則」. Ref. C01005593600. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), Tokyo. Available via https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/C01005593600

Hikosakae T (1921) Military doves (1).「軍用鳩 (1) 」. JACAR (Japan Center for Asian Historical Records) Ref.C08050218300. Available via https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/C08050218300

International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) (2022) Animals, people and war: the impact of conflict. Available via https://www.ifaw.org/resources/animals-people-war. Accessed 30 May 2023

Imperial Japanese Navy (1933a) Draft of textbook for naval envoys (3).「海軍使鳩教科書草案 (3) 」. Ref. C05023284100. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), Tokyo. Available via https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/C05023284100

Imperial Japanese Navy (1933b) Draft textbook for naval envoys (1).「海軍使鳩教科書草案 (1) 」. Ref. C05023283900. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), Tokyo. Available via https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/C05023283900

Imperial Japanese Navy (1935a) Military pigeon experiment research record (1).「軍鳩実験研究録 (1) 」. Ref. C05034609500. Tokyo. Available via https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/C05034609500

Imperial Japanese Navy (1935b) Military pigeon experiment research record (2).「軍鳩実験研究録 (2) 」. Ref. C05034609600. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), Tokyo. Available via https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/C05034609600

Imperial Japanese Navy (1935c) Military pigeon experiment research record (3).「軍鳩実験研究録 (3) 」. Ref. C05034609700. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), Tokyo. Available via https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/C05034609700

Imperial Japanese Navy (1935d) Military pigeon experiment research record (5).「軍鳩実験研究録 (5) 」. Ref. C05034609900. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), Tokyo. Available via https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/C05034609900

Jia J (2021) The role transformation and image-changing of the British carrier pigeon in the First World War. World Hist 44:67–78+154

Lima MR, Campbell DCP, Cunha-Madeira MRD, Bomfim BCM, de Paula Ayres-Silva J (2023) Animal welfare in radiation research: the importance of animal monitoring system. Vet Sci 10:651

Lindsjö J, Cvek K, Spangenberg EMF, Olsson JNG, Stéen M (2019) The dividing line between wildlife research and management—implications for animal welfare. Front Vet Sci 6:13

Miller LJ, Luebke JF, Matiasek J (2018) Viewing African and Asian elephants at accredited zoological institutions: conservation intent and perceptions of animal welfare. Zoo Biol 37:466–477

Navy Ministry (1927a) Draft textbook for naval missions (2).「海軍使鳩教科書草案 (2) 」. Ref. C04015696700. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), Tokyo. Available via https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/C04015696700

Navy Ministry (1927b) Military pigeon capability 2 (1).「軍鳩能力2 (1) 」. Ref. C04015695500. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), Tokyo. Available via https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/C04015695500

Navy Ministry (1927c) Military pigeon communication in tropical and boreal regions 5.「熱帯寒帯地方に於ける軍鳩通信5」. Ref. C04015696000. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), Tokyo. Available via https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/C04015696000

Navy Ministry (1927d) Military pigeon research report 1.「軍鳩研究報告1」. Ref. C04015695400. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), Tokyo. Available via https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/C04015695400

Navy Ministry (1927e) Military pigeon use of aircraft 6.「諸航空機より軍鳩使用法 6」. Ref. C04015696100. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), Tokyo. Available via https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/C04015696100

Navy Ministry (1927f) Naval land-based fixed pigeon coop management standards and expenses 7.「海軍用陸上固定鳩舎管理標準並に経費7」. Ref. C04015696200. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), Tokyo. Available via https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/C04015696200

Navy Ministry (1927g) Night pigeon 4.「夜間鳩4」. Ref. C04015695900. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), Tokyo. Available via https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/C04015695900

Navy Ministry (1933) Draft textbook for naval envoys (2).「海軍使鳩教科書草案 (2) 」. Ref. C05023284000. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), Tokyo. Available via https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/C05023284000

Navy Ministry (1942) History of the Navy system, vol 15. Navy Minister’s Secretariat, Tokyo

Naylor A (2023) In Ukraine, dead dolphins tell a story of ecocide and violence. Available via https://gizmodo.com/ukraine-black-sea-dolphin-deaths-russia-war-1850279402. Accessed 1 Apr 2023

Nowrot K (2015) Animals at war: the status of “animal soldiers” under International Humanitarian Law. Hist Soc Res 40:128–150

O’Brien SL, Cronin KA (2023) Doing better for understudied species: evaluation and improvement of a species-general animal welfare assessment tool for zoos. Appl Anim Behav Sci 264:105965

Phillips G (2018) Pigeons in the trenches: animals, communications technologies and the British Expeditionary Force, 1914–1918. Br J Mil Hist 4:60–80

Rust K, Clegg I, Fernandez EJ (2024) The voice of choice: a scoping review of choice-based animal welfare studies. Appl Anim Behav Sci 275:106270

Schoon A, Heiman M, Bach H, Berntsen TG, Fast CD (2022) Validation of technical survey dogs in Cambodian mine fields. Appl Anim Behav Sci 251:105638

Snyders H (2015) ‘More than just human heros’ : the role of the pigeon in the First World War. Sci Militaria South Afr J Mil Stud 43:133–150

Soltis J, Leighty KA, Wesolek CM, Savage A (2009) The expression of affect in African elephant (Loxodonta africana) rumble vocalizations. J Comp Psychol 123:222–225

Swart S (2010) “The world the horses made”: a South African case study of writing animals into social history. Int Rev Soc Hist 55:241–263

Tedla MG, Berhe KF, Grmay KM (2023) The impact of armed conflict on animal well-being and welfare, and analyzing damage assessment on the veterinary sector: the case of Ethiopia’s Tigray region. Heliyon 9:e22681

Terrill C (2001) Romancing the bomb: marine animals in naval strategic defense. Organ Environ 14:105–113

Webb EK, Saccardo CC, Poling A, Cox C, Fast CD (2020) Rapidly training African giant pouched rats (Cricetomys ansorgei) with multiple targets for scent detection. Behav Process 174:104085

Whiteman H (2024) Thousands of sheep and cattle stranded at sea after Red Sea crisis turn back in The Dictionary of Substances and Their Effects. Available via https://edition.cnn.com/2024/01/31/australia/australia-ship-sheep-cattle-red-sea-intl-hnk/index.html. Accessed 2 Feb 2024

Yonai M (1936) Yokochin confidential no. 51 11.8.11 research expenditure results report.「横鎮機密第51号 11. 8. 11 研究費実験成績報告」. Ref. C05035336700. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), Tokyo. Available via https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/C05035336700

Yanagisawa J (2011) Introducing the Early Denshurikyuu in the Japanese Army—the center of Kaikyosha chronicles.「日本陸軍における初期の伝書鳩導入–『偕行社記事』を中心に」. Mil Hist 47:41–60

Zimmermann B, Castro ANC, Lendez PA, Carrica Illia M, Carrica Illia MP, Teyseyre AR, Toloza JM, Ghezzi MD, Mota-Rojas D (2024) Anatomical and functional basis of facial expressions and their relationship with emotions in horses. Res Vet Sci 180:105418

Zych AD, Gogolla N (2021) Expressions of emotions across species Curr Opin Neurobiol 68:57–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2021.01.003 (accessed on 15 October 2024)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: CP and ZQL; data collection and processing: ZQL and LHG; supervision: CP and YFZ; original draft: CP, ZQL, LHG and YFZ; review and editing: CP, ZQL, LHG and YFZ. All authors have read and agreed on the final manuscript and submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, C., Luo, Zq., Guo, Lh. et al. The impact of war on animal welfare: the Imperial Japanese Navy’s manipulation of pigeon behavior in WW II. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 160 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04397-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04397-8