Abstract

The Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) is a vehicle for promoting students’ learning that plays a significant role in basic education reform globally. Few studies have used the transnational academic achievements of PISA as evidence to systematically summarize the primary motivation behind PISA’s participation in global decision-making and the core issues of PISA’s impact on education reform. Using a systematic review approach, we aimed to analyze findings from empirical research about the impact of PISA on global basic education policies and to provide an overview of the effects of PISA on global basic education reform. The Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and Scopus databases were searched for empirical research written in English, focusing on basic education, and including search terms such as PISA, educational reform, and policy. A total of 85 studies were included in the review and systematically synthesized to determine the effect of PISA on global basic education reform. PISA drives policy discussions on education quality and equity through its pursuit of educational quality, data-based comparative analysis, and evidence-based research paradigms. PISA’s impact has extended far beyond its original function of measuring the quality of education among countries, and it profoundly affects global education governance through ‘soft’ governance of the education system. We present a specific mechanism model of PISA’s impact on the development of education policies that demonstrates the two-way interaction between PISA and education reform, providing a theoretical reference for future academic research on education reform linked to PISA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the advent of the knowledge economy era in the 1990s, building a modern education power has become a cornerstone of socio-economic and technological competition among countries. While benchmark indicators such as investment in education as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) are recognized as ‘supply’ variables in a country’s knowledge economy, effectively measuring the impact of domestic investment in education on students’ knowledge and skills remains a challenge. Furthermore, intensifying globalization has meant that countries have begun to pay attention to the guiding role of international references in the formulation of public and education policies. However, a set of evaluation tools with international comparability and common recognition among countries has not been established to evaluate national education systems and effectively monitor talent training quality (Baird et al. 2011). The Organization for Economic Development and Co-operation (OECD) proposed the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) in 1995 and officially launched it in 1997, in response to these needs.

The main objective of PISA is to assess the ability of 15-year-olds in countries around the world to apply their knowledge and skills in reading, mathematics, and science to real-life challenges (OECD, 2022b). The assessment provides a dynamic and regular program of educational evaluation and monitoring to compare international levels of education, analyze education systems, improve education quality and provide data support for policy making (Gillis et al. 2016). Studying the effect of PISA on education reform may provide an important reference to enable better understanding of the global education system, reflection on the educational status quo, and improvement of education policies and quality.

PISA is designed to assist governments in monitoring the outcomes of education systems using a common, internationally recognized framework for assessing and reporting student achievement. With the acceleration of globalization, economic and human capital competition among countries has become more intense, and quality education is key to improving national competitiveness and innovation ability. PISA can be regarded as the OECD’s embodiment of the neoliberal free market concept in the field of education. It emphasizes accountability, standardization, and the promotion of competition among schools, in part reflecting the human capital strength of countries in the global economic competition (Pons, 2017). PISA survey data can be used to construct a macro measure of human capital to support the improvement of education systems in participating countries from an economic development perspective (OECD, 2022a).

Driven by globalization and economic integration, the field of education governance has developed a comparative focus in recent years, with education no longer confined to the scope of a single country but rather a global issue (Madsen, 2022). As a widely recognized authoritative brand launched by the OECD, PISA benefits from its characteristics of ‘de-contextualization’ and ‘generality’, providing possibilities for international education comparison in the context of globalization (Grek, 2010). PISA is also a driving force for ‘governing by numbers and evidence-based policy making in the field of education (Grek, 2009; Lawn, 2003). The large-scale international data provided by PISA provide policy makers with comparable data on a global scale to help them better understand the functioning of education systems and student performance, using quantitative data and indicators to formulate more effective policies and reform programs. Thus, PISA results are gradually becoming evidence of the legitimization of political action, and PISA’s ‘soft’ governance tools are receiving increased scholarly attention. PISA itself constitutes a form of control for effective governance through information and indicators. PISA data are analyzed and interpreted by change agents for use in education policy making and reform. The OECD provides remote guidance to national policymakers by reporting PISA results and global rankings. The results can be used to verify the legitimacy of reforms already implemented in a country, or as motivation to follow the policy recommendations of the OECD or launch new reforms (Gillis et al. 2016).

Growing numbers of empirical studies demonstrate the transformative effect of PISA in the field of global basic education. PISA and its associated global series of education comparison indicators have direct and indirect influences on education policies (Yore et al. 2010). The direct impact comes from a country’s performance in the assessment, or from OECD policy recommendations related to PISA. In other words, education policy reform is promoted according to PISA results, and education reform is guided by PISA (Neumann et al. 2010). For example, in 2001, Germany experienced ‘PISA shock,’ later described as a decisive watershed in German education policy making. Immediately after the publication of the PISA results at the end of 2001, Germany—under external pressure from PISA—put forward a comprehensive education reform agenda, with at least three output-based reform norms directly linked to PISA: establishing education standards and centralized monitoring, top-reducing governance, and improving education standards. The effect was to strengthen school autonomy and expand empirical educational research and decision-making.

Unlike the direct impact on the German education sector, the indirect impact of PISA tests is related to the use of PISA competency standards as a universal framework to justify particular policies. Countries that perform well on PISA, such as Finland, tend to interpret PISA results as an endorsement of their own policy initiatives and political positions. PISA results have been used to mobilize policy action to legitimize domestic education reforms aimed at ensuring continuous improvement in Finnish performance (Grek, 2009). Rautalin and Alasuutari (2009) analyzed the process of combining knowledge production in OECD with the formation of Finnish education policies, pointing out that Finland’s basic education policies were largely unaffected because of the country’s high performance on the PISA. However, Finnish national policy makers (i.e., officials in the Ministry of Education and the National Board of Education) tend to use PISA results and international rankings to justify their policy goals. In this sense, the key concepts, measurement objects, and measurement techniques adopted in PISA are all indirectly incorporated as part of the national education policy discourse (Rautalin and Alasuutari, 2009).

Researchers also pay attention to the factors that influence policy response. The educational reform effects of PISA relate to each country’s political, historical, and cultural educational practices, and factors influencing the policy responses of nation-states are diverse and interwoven. Countries with similar PISA results or rankings may initiate very different education policies (Baird et al. 2016). France and the United Kingdom, for example, obtained similar results in the 2001 PISA, but have since adopted different strategies to improve their educational performance. In the case of France, the response may be related to the skeptical attitude of the French public and policymakers towards comparative assessments and criticisms of cultural bias, inadequate statistical methods, and oversimplification of indicators (Dobbins and Martens, 2012). In China, the government’s policy responses to external influences are heavily influenced by the country’s cultural traditions and political system. The education model advocated by the OECD is seen as Western, neoliberal, economically driven, and diminishing the role of national governments. Countries that attach great importance to their own cultural traditions and political stability may differ in their policy responses to PISA results compared with Western countries (Xie et al. 2022). In summary, research confirms that policy responses of individual countries to PISA results cannot be attributed to a single actor but reflect tight networks of social relations and material conditions, and policymakers’ definitions of policy conflict and convergence.

Responses to PISA results may also vary across PISA cycles and across countries and regions. When the results are published, policymakers, media, and citizens in many countries tend to react strongly (e.g., in Germany, Turkey, Denmark, Mexico, and Portugal), while responses in other countries (e.g., the United States, Finland, and France) demonstrate extreme indifference. Studies have suggested that the opportunity for countries to make policy responses to PISA results is related to changes in the international situation and in cases of a sudden large gap between a country’s long-term self-perception and the newly released empirical results (Martens and Niemann, 2013). Bieber and Martens (2011) analyzed the impact of PISA results on education policy by comparing the United States and Switzerland. They argued that PISA results had an immediate impact in Switzerland, leading to policy development and convergence with OECD recommendations. However, findings for the U.S. merely confirmed what had already been agreed on in that country—that the U.S. education system was below international standards. Therefore, the domestic pressure caused by this problem was not exacerbated by the empirical findings at the time of their release (Bieber and Martens, 2011). In 2009, however, researchers observed a spurt of academic discussion about PISA and U.S. students’ ability to learn, with PISA results becoming central to U.S. educational discussions. Studies suggest that the change in perception of the problem occurred because China (Shanghai), the U.S.’s most direct rival in the world economic market, performed very well in the same PISA test, which was interpreted as China’s economic output surpassing that of the U.S. in future. This perception directly triggered a new round of education reform in the U.S. (Martens and Niemann, 2013).

International organizations play an important role in global policy-making, and the topic has gained increasing attention. Empirical research on the effect of PISA on basic education reform in various countries is relatively new but has already yielded rich results regarding the conceptual framework, policy responses, policy convergence, and factors influencing basic education policies affected by PISA. These studies reveal the impact of PISA as a tool for global education governance and its power to deepen competitive comparisons in education. Discussion of educational policy reform driven by PISA tends to focus on the internal research of nation-states, analyzing the mechanism and path of PISA’s influence on education policies in countries and regions by exploring their policy convergence mechanisms and policy translation framework. For example, Bieber and Martens (2011) focused on factors that lead to voluntary convergence of policies, namely cross-border communication, regulatory competition, and independent problem-solving by establishing a theoretical framework for causal mechanisms of voluntary convergence of education policies. In contrast, Xie et al. (2022) borrowed the ‘ti (体, ‘essence’) and yong (用, ‘function’) framework.’ to analyze China’s political actions in dealing with problems under the external influence of PISA. The body-use framework has been used in China since ancient times to explain Sino-Western relations—‘body’ refers to the fundamental, intrinsic, and essential nature of things, and ‘use’ means the appearance and function of body (Xie et al. 2022). Moving beyond country-specific studies, research has paid little attention to supra-national organizations or institutions and has not adequately analyzed the types of capital they can call on and their ability to influence nation-state policy—a process that deserves further exploration in the current era of globalization.

The empirical study of basic education policies informed by PISA has become a hot spot in the field of global comparative research on basic education policies. However, to date there are no studies systematically summarizing the evidence of transnational academic achievements of PISA research to understand the motivation underlying PISA’s participation in global decision-making and the core issues of PISA’s impact on education reform.

Using a systematic review approach, this study aimed to analyze findings from empirical research about the impact of PISA on global basic education policies and to provide an overview of the effects of PISA on global basic education reform. The study may serve as an information reference for empirical research on the effect of global basic education reform associated with PISA. The following research questions were addressed:

Research Question 1: What are the main characteristics of PISA impact policy research (research area, research object, research methodology and design, conceptual framework, and theoretical model)?

Research Question 2: What are the core issues of PISA affecting education reform?

Research Question 3: What factors influence PISA’s effect, i.e., under what conditions does PISA have an impact on national policy making?

Methods

A systematic review of the literature was undertaken to reveal the overall trend, shortcomings, and future research directions of existing studies Newman and Gough, 2020). Systematic reviews aim to improve the literature by systematically collecting, analyzing, and summarizing all relevant research literature on a particular topic. The approach is characterized by well-defined research questions, a rigorous literature search and screening processes, systematic data extraction and analysis methods, and transparent reporting standards (Newman and Gough, 2020; Xiao and Watson, 2019). As a stand-alone research method, systematic reviews critically evaluate relevant literature to promote the development of pertinent theories and create a key knowledge source for the target research field. Systematic reviews have been widely used in fields such as medicine, social sciences, education, and environmental sciences (Lame, 2019).

Design and search procedure

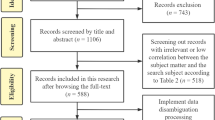

The databases searched in this study included the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) (Web of Science) and Scopus. The main English language journals that contained relevant studies included the Oxford Review of Education, International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, Journal of Education Policy, International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, European Journal of Education, Comparative Education, Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, German Politics, and European Education. These journals are rigorously peer-reviewed and representative academic journals in the field of education. The key search terms were (PISA OR ‘Program for International Student Assessment’) AND (‘education polic*’ OR ‘educational polic*’ OR ‘education reform’ OR ‘educational reform’) AND (‘impact*’ OR ‘influence*’ OR ‘effect*’ OR ‘consequence*’). As of September 13, 2023, 2199 initial articles were retrieved. After excluding duplications, a total of 1754 articles were obtained.

Selection/Extraction process

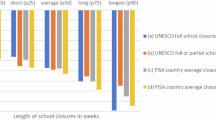

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the study results based on the research questions, inclusion criteria were formulated for the 1754 literature items initially retrieved: (1) peer-reviewed and written in English; (2) journal article; and (3) uses empirical research methods (i.e., qualitative, quantitative or mixed-methods research). After preliminary screening of abstracts and conclusions, a total of 625 articles were selected for this study. The full texts were downloaded and read, and secondary screening took place based on the following criteria (shown in Table 1): (1) the full text of the original article could be downloaded; (2) the research focused on the impact of PISA on education policy; and (3) the research focused on the basic education stage. These criteria ensured that only those articles that substantively explore the impact of PISA tests on international basic education policy were retained. Substantive discussions typically included empirical investigations of the impact of PISA tests, discussion about the impact of PISA emerging from empirical research, or research that focuses on the impact of PISA tests. After secondary screening, 18 studies that did not respond to the research question were excluded, and 85 studies that could respond to at least one research question were retained for inclusion in the analysis phase of this study. The PRISMA flow chart (Fig. 1) shows the 85 selected studies that were analyzed in terms of author, year, country, conceptual framework, research method, and research conclusion.

Based on research methods and data types, we divided empirical research methods into three categories: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods research. Of the 85 empirical research studies, 49 adopted qualitative data analysis methods and 36 studies used mixed research methods. Quantitative research data mainly came from the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), PISA scores, and ranking data. Qualitative research data included official policy documents issued by central government departments such as the Ministry of Education, state media reports and political speeches, relevant policy research and consulting reports of scholars engaged in education policy formulation, and interview documents and data from government officials and experts. Most studies were case studies, historical comparative studies, and international comparative studies to analyze the effect of PISA on global basic education reform.

In the evaluation of research quality, the included literature can be divided into evaluation effect literature, descriptive literature, and explanation literature, and the quality evaluation methods adopted by different types of literature are different. For descriptive literature, the quality of descriptive literature is judged according to the information source, the correlation between the research purpose and research method, and professional authority. As for the qualitative literature explaining the reasons, there is no unified quality evaluation standard in the world. This study mainly considers two aspects: The validity of the research (including whether the data collection method and analysis method are clearly explained, the validity test of the data source and analysis process, the validity test of the respondents on the data, and whether the special or contradictory data are clearly described, etc.), the relevance of the research (including whether the research results have new knowledge or theories proposed, and whether the research results can be widely applied to the same type of people or other groups) Other population, whether the findings can be generalized to similar environments, etc.)

This study further describes the 85 articles included in the analysis, summarizing their main arguments, research methods, and design. We analyzed the empirical results of the literature and explored the effect of PISA on global basic education reform. Data analysis was executed in two steps based on the coding analysis. For the first step, individual articles were analyzed to identify the separate codes and create a specific codebook. In the second step, a series analysis approach, including regional distribution and core themes analysis, was undertaken to address the research questions. Data analyses were conducted by the authors, and discussion took place until mutual agreement was reached. Detailed descriptions of the analyses are given in the following sections.

In terms of their conceptual framework, many of the research papers adopted theoretical frameworks for policy formulation and analysis. These included agenda-setting theory (Martens and Niemann, 2013), contemporary human capital theory and governance frameworks for globalization and education (Sellar and Lingard, 2018), the causal mechanism theory of voluntary convergence in education policy (involving policy reference and transfer) (Bieber and Martens, 2011), and the body-use framework, an analytical framework Chinese policymakers use to interpret and negotiate the relationship between internal reform agendas and external influences (Xie et al. 2022). Researchers point out that power—in its broadest sense—must be viewed as a network of governance intertwined with knowledge, subject status, and participant identity when speaking of the public policy process. Thus, political sentiment is an important lever for policy change (Sellar and Lingard, 2018), and affective theoretical frameworks and critical discourse analysis are useful for analyzing textual materials to explore the effect of PISA on policy development and comparison. Discourse analysis helps to deconstruct the structural relations of dominance, power, and control between local and foreign countries, expressed in language.

Results

Regional distribution analysis

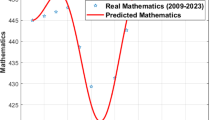

Current research on the impact of PISA on international basic education policies and educational reform shows clear regional distribution patterns (Fig. 2). The countries and regions included in the dataset are relatively narrow in scope, with some countries repeatedly appearing. Frequently included regions included Australia, Western European countries (e.g., Germany, the United Kingdom, France, Switzerland, and Spain), Nordic countries (Finland, Norway, and Sweden), Southern Cone countries (Argentina, Uruguay, and Chile), the United States, Canada, and some Asian countries (mainly Japan, Shanghai, China, South Korea, and Jordan). PISA has attracted participation from more than 90 countries and economies around the world as part of the OECD Global Initiative (OECD, 2022b). However, as of September 2023, relevant research literature was available for only 17 countries. This indicates that although PISA and its impact have become a research focus, in-depth studies on the impact of PISA on international basic education policies remain relatively limited, and the research scope is narrow. 39 studies were undertaken in Western Europe (20 in Germany, 8 in France, 5 in the United Kingdom, 5 in Spain, and 2 in Switzerland), 16 in Asia (8 in China, 2 each in Japan, South Korea, Jordan, and Australia), 14 in Northern Europe (6 in Finland, 8 in Norway), 10 in North America (5 in the United States and 5 in Canada) and 6 in South America (2 each in Argentina, Uruguay and Chile).

Literature with Western European countries as the main research objects accounted for 45.9% of the total. The main research object of the literature was EU countries or member states of the European Economic Area (EEA), accounting for 62.4% of the total. Thus, European countries are the focus of studies on the effects of global basic education reforms associated with PISA, likely related to the OECD’s close ties with the European education system where it plays an important role. Europe represents an important part of the OECD world, and the OECD and the European Commission have long shared broadly similar policy agendas. Data on European education systems defined and collected by the OECD intersect with data from the EU, helping to create a manageable and sustainable common space—the European Education Space. Therefore, PISA—as the main tool for providing data for European education systems—has shaped the way European education networks operate, and the policy areas of concern have received extensive attention from European scholars since the first PISA results (Grek, 2009).

Core ways in which PISA affects education reform

The policy responses of nation-states to PISA scores and rankings within a given PISA cycle vary. PISA’s official position is that the test results reflect the quality and equity of learning outcomes achieved across the globe. Therefore, this study also uses the analytical framework of ‘quality’ and ‘fairness’ to analyze the effect of PISA on basic education reform.

From a quality perspective, through PISA the OECD emphasizes a comprehensive assessment of students’ knowledge and skills in reading, mathematics, and science to meet real-life challenges. The PISA Competency Framework requires education systems to equip young people with the knowledge and tools they need to address challenges facing modern societies, such as rapidly changing labor markets, continued digitization of economies and societies, social mobility, growing inequality within countries, large-scale international migration flows, and climate change (OECD, 2019). The impact of PISA on the reform of basic education to improve the quality of education in countries manifests in three levels: macro, middle, and micro decision-making levels. The impacts at each of these levels are discussed in the following sections.

At the macro decision-making level, the impact of PISA is manifested in (1) accepting the neoliberal educational values advocated by PISA and increasing educational expenditure (e.g., in Germany and France); (2) accepting the concepts of ‘competence’ and ‘literacy’ (e.g., in Japan); (3) influencing the acceptability of PISA’s ideal societies and the choice of reference societies (e.g., in South Korea); (4) strengthening international cooperation with PISA and OECD (e.g., in Uruguay); and (5) promoting evidence-based education policies (e.g., in Japan, Germany and Jordan). German society was shocked when the first PISA results came out in 2000. From the 1970s to the early 2000s, Germany had failed to create human capital and, in OECD terms, deprived a large proportion of its students of the opportunity to acquire academic qualities needed to obtain optimal rewards in their working lives (Martens and Niemann, 2013). The poor PISA results exposed the hidden dangers of the German education system, and thus, directly started all-round education reform in that country. Niemann et al. (2017) analyzed the policy responses and debates in Germany after the release of the 2000 PISA results, pointing out that the first PISA test showed that the German education system did not meet the required standards of effectiveness and efficiency, revealing a large gap between Germany and high-performing countries in the field of education. It also exposed the stalled state of education reform, directly pushing education themes onto the public policy agenda and further reinforced policy actions by policymakers to offset performance deficits. PISA also promoted the integration of comparative cultural paradigms into German educational policy making. Yore et al. (2010) argue that the educational reforms implemented in Germany after the first round of PISA results were made public (in 2000) reflect a paradigm shift, including a stronger positioning of the educational output perspective. Education policy making was no longer only concerned with the realization of certain principles but incorporated a new governance model of evidence-based policy making (Yore et al. 2010).

For Japan, the impact of PISA testing on basic education policy was reflected in the prominence of ‘PISA competence’ and ‘PISA literacy’ in policy objectives. Unlike Germany, the results of the second PISA in 2003 showed that the crux of the problem with Japanese education lay in the content of education rather than the system or organization (Ninomiya, 2019). The ‘yutori education’ policy implemented in Japan in the 1980s and 1990s led to declining academic levels and learning abilities of Japanese students at the end of the 20th century, attracting great attention from Japanese educationalists, economists, and administrators. After the release of the second PISA results, many news outlets reported extensively on the results of the survey and compared the results of the 2003 assessment with those from 2000. The results showed that Japanese students had fallen in the rankings in several focus areas (MEXT, 2004), confirming the decline in student academic achievement since the 1980s and the widespread talk of an education crisis in Japan. In 2004, spurred by the publication of the PISA 2003 results, the idea of PISA literacy was formally incorporated as a main goal of national education policy. PISA literacy refers to reading and broader knowledge of the entire curriculum. It focuses on higher-order competencies such as problem-solving, knowledge application, creative work, and knowledge recall (National Institute for Education Policy, 2019). PISA literacy brought a new concept of academic achievement to Japanese education with different meanings and achievements from the previous understanding of academic achievement (Ninomiya, 2019).

The impact of PISA on Korea’s basic education policy at the macro level is related to the choice of the reference society. Kim and Choi (2023) point out that before the launch of PISA, South Korea had been ‘silently borrowing’ from Japan’s education policies. While the results of PISA 2009 led Western educators to study education policies in Shanghai, South Korea turned its attention to Finland, one of the top-achieving countries in PISA 2003 (Kim and Choi, 2023). Acosta (2020) argues that for Southern Cone countries such as Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay, the value of PISA lies in its association with the OECD. In other words, the policy impact of PISA is reflected in establishing ties with OECD at the level of the education system, making domestic education affairs a part of national economic policy and the international affairs agenda. Countries in that region derive value from PISA by becoming a global governance complex for sustainable development (Acosta, 2020).

At mid-level decision-making, PISA’s impact mainly manifests as: (1) improving teacher education in the initial stage of teacher pre-service education and teacher continuing professional development by establishing colleges in universities (e.g., in Jordan and France); (2) benchmarking the PISA test standards in the assessment system, introducing large-scale national education assessment, and strengthening national education and teaching standards reviews (e.g., in Switzerland, Norway and China); and (3) tools to strengthen monitoring and continuous improvement of processes and results in school education management (e.g., in Japan). Specifically, Bieber and Martens (2011) pointed out that in Switzerland, the introduction of the national education standard (the Interstate Compulsory Education Harmonization Agreement of the Swiss school system or HarmoS) meant greater consideration of students’ abilities and marked the rise of a new test culture. This involved a shift from input-oriented fundamentals to underlying logic targeting efficiency and output control (Bieber and Martens, 2011). The Canada Education Indicators Plan introduced the same regionally uniform indicators used in the OECD report, including the PISA-based ‘Student Achievement Excellence’ indicator. PISA results became the basis for determining whether Canada’s education level was excellent and whether the country’s education policies were successful (Baird et al. 2016). In China, the impact of PISA on educational assessment was reflected in the establishment of a new educational quality assurance system based on the existing large-scale examination system. In 2007, the Ministry of Education established a monitoring center to carry out a pilot program to monitor the quality of compulsory education. The Ministry of Education’s report on the center refers to the standards of educational quality and student ability followed by PISA tests, based on critical research and adaptation of PISA indicators. The report describes six subject indicators for mathematics, language, science, ethics, physical education, and art (Xie et al. 2022). Ninomiya (2019) believes that PISA has also influenced the construction of the evidence-based improvement cycle in the Japanese school education management system – school administrators focus on the academic achievement of the school, check the corresponding information about the educational process and outcomes according to set goals, and use this information as evidence to promote the improvement cycle of educational management (Ninomiya, 2019).

At the micro level of decision-making, the policy effect of PISA manifests in: (1) curriculum reform—accepting the competence standards advocated by PISA and reforming the curriculum on this basis, e.g., Germany’s emphasis on improving reading skills and promoting learning in mathematics and science; (2) the school system or changes in the school system, including the reform of the original education system, the adjustment of the compulsory education period, the unification of the school system, and the standard PISA test period. For example, Germany’s discourse on curriculum reform based on PISA results deals with how well students can apply their knowledge and skills to solve relevant problems in a variety of situations. Knowledge mastery is no longer regarded as the key indicator to judge students’ academic success; but rather, students’ learning ability acquired through course learning is the focus of course evaluation. Neumann et al. (2010) discussed the impact of the PISA test on German science education in detail, reporting that the PISA was the basis for the construction of the NES curriculum. The NES incorporates the concepts of scientific literacy used in the PISA testing framework, including understanding and practice in science-related situations, with a strong emphasis on the role of science in everyday life (Neumann et al. 2010) (see Table 2).

Educational equity was the second dimension we considered in recognizing the policy changes in PISA countries. PISA is based on the principle that equitable education is key to achieving sustainable and inclusive growth. The PISA definition of equity in education includes the two related concepts of inclusiveness and equity. Inclusion is a measure of whether an education system ensures that all students acquire basic foundational skills. Equity is related to students’ access to quality education and, more specifically, the extent to which background circumstances influence educational outcomes (OECD, 2019). Overall, PISA’s equity framework focuses on whether a country or region’s education system can ensure that all students, regardless of their background or circumstances, have access to high-quality education.

For equity of opportunity, PISA considers whether all students can acquire basic foundational skills. This relates to access to educational resources and academic and social segregation between schools (OECD, 2010). At the level of policy response, nation-states use PISA results as a policy guideline for equity in educational opportunities, which usually means: (1) harmonization of admission policies or relaxation of admission criteria (e.g., in Switzerland); (b) promotion of equal opportunities for women, low-income families or ethnic minorities in science and technology (e.g., in France); and (3) increasing the number and size of full-time schools (e.g., in Germany). The Swiss HarmoS incorporated OECD recommendations to promote social inclusion and equal opportunities, requiring that the duration of compulsory education be extended from 9 to 11 years and that children must attend kindergartens and basic schools at the age of four (Bieber and Martens, 2011). France’s Film Act introduced intensive reforms to promote equal opportunities and democratize schools, such as a 20% increase in the number of bachelor’s degree graduates from low-income families and a 15% increase in women in science and technology fields (‘filieres’) (Dobbins and Martens, 2012). Meanwhile, the impact of PISA on Germany’s educational equity and inclusion policies includes early progress for students (especially for those from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds), improvement of students’ basic skills, better cooperation between pre-school institutions and primary schools, quality assurance measures, advanced teacher training, and expansion of all-day schools (Niemann et al. 2017).

From the perspective of process equity, PISA tests focus on students’ learning process, including their motivation, self-cognition, and learning strategies (OECD, 2010). In response to PISA’s demand for fairness in the education process, the policy responses of countries and regions mainly include: (1) introducing personalized learning assistance into the education system and providing remedial teaching (e.g., in France); (2) establishing national unified teaching standards and implementing the national curriculum; (3) delegating autonomy to individual schools; and (4) improving the level of teacher education and improving the quality of education in every school. For example, the French Ministry of Education’s Orientation and Planning Act on the Reconstruction of the Republic’s Schools, adopted in July 2013, aimed to restructure the education system and improve the quality and equity of school education. According to Michel (2017), the Act was related to the educational equity framework of PISA, and the main policy measures adopted included: prioritizing primary education and basic skills, identifying key knowledge and competencies by increasing basic cultural and civic education, strengthening priority education for disadvantaged students, improving the learning environment and school spirit in schools, improving initial teacher education, and continuing teacher professional development through the creation of colleges within universities. In addition, top-reducing detailed governance and strengthening school autonomy were also important ways to promote fairness in the process.

Rautalin and Alasuutari (2009) believe that the decentralization of educational decision-making power in Finland is an important argument used by Finnish policy makers to prove the superiority of the country’s education policy and system. Globally, most countries have adopted the policy practice of giving schools more decision-making power and autonomy to improve education implementation. For example, in 2007, the German state of Saxony implemented mandatory school independence, requiring the establishment of an executive school board in each school to bridge the gap between schools (Hartong, 2012). In this way, schools and educational institutions can better meet the needs of students and parents, respond more flexibly to local differences, and provide a more equitable and diverse educational experience. Reducing centralization helps democratize the education system and meet the needs of communities.

For outcome equity, PISA tests assess whether students have the knowledge and skills needed to fully participate in society by comparing their knowledge and skills in areas such as reading, mathematics, science and problem-solving (OECD, 2010). To respond to the requirements of the PISA educational equity framework, countries and regions typically adopt policy responses to meet the central goal of education according to the PISA competency requirements, emphasizing the conformity of educational quality rather than just quantitative equity. For example, in 2008, Japan released a new National Learning Curriculum that retained the concept of ‘passion for life’ originally proposed in the 1998 Curriculum, while offering a new definition of academic achievement. The new approach comprised three elements: “a solid grasp of basic knowledge and skills”, “development of thinking, decision-making, expression and other abilities necessary to solve problems”, and “development of active learning attitude and development of students’ personality” (Ninomiya, 2019) (see Table 3).

Factors affecting the influence of PISA education reform and the specific mechanism of policy response

The factors influencing the policy responses of nation-states are diverse and interwoven. Studies have demonstrated that policy changes and reforms influenced by PISA are related to the date of release of the PISA results, but actual political initiatives are more likely to be based on the socio-economic and socio-political outlook of ruling parties (Baird et al. 2016; Choi and Jerrim, 2016; Yore et al. 2010). At the same time, education issues between countries and regions are increasingly interrelated because of globalization and changing educational needs. The increasing pressure of transnational governance in the field of education has also been proved to be closely related to the policy reform effect of PISA (Dobbins and Martens, 2012). Therefore, to explore the factors influencing the effect of PISA education reform, that is, the extent to which nation-states can implement reforms and take corrective action, we should consider the interaction of historical, sociological, political, and cultural factors in countries and regions and place national policy responses in the framework of the global education field.

International organizations play an important role in the global dissemination of policy paradigms and ideas. Nation-states’ recognition and acceptance of the scientific nature of international organizations and their educational ideas is a prerequisite for influencing policy formulation. International organizations need to be seen as legitimate authorities and experts to successfully influence policymaking at the nation-state level (Martens and Niemann, 2013). For example, in exploring the reasons for France’s initial indifference to PISA and its ranking, Dobbins and Martens (2012) suggest that the French public and policymakers held skeptical attitudes to the comparative assessment methodology adopted by the OECD, arguing that PISA suffers from cultural bias, inadequate statistical methods, and oversimplified indicators. In Finland, by contrast, PISA is considered a “legitimate and important barometer” (Rautalin and Alasuutari, 2009). Thus, the key concepts, measurement objects and measurement techniques used in PISA have been incorporated as part of the Finnish educational policy discourse (Rautalin and Alasuutari, 2009).

PISA is often considered part of the globalization of education. Even countries with high-ranking positions, such as Finland, are under pressure to borrow educational ideas and practices. China is no exception. Closer engagement with international organizations produces chances to gain symbolic capital and national prestige (Xie et al. 2022, p. 13).

At the supranational level, contextual factors such as transnational pressures, the international situation, regional economic development policies, and the dominant framework of contemporary education policies are seen as important and decisive conditions for nation-states to transform their education systems and take corrective measures under the influence of PISA. Sellar and Lingard (2018) explored Australia’s attitude to Shanghai’s 2009 PISA performance, highlighting the rise of the so-called ‘Asian Century’ as an important contextual factor in Australia’s education policy response, that is, Australia’s future economic development will be closely linked to Asia’s economic prosperity, especially that of China. The superior performance of international competitors makes countries realize that their economic development and statehood are being challenged (Martens and Niemann, 2013). The U.S. domestic policy response to PISA exemplifies this point: the U.S. realized the significance of PISA for national development when noting the excellent performance of students in Shanghai, China (who were taking the test for the first time)—not, as one might expect, by reflecting on the mediocre performance of its own students. The PISA results of China, the most direct competitor in the global economic market, caused a strong reaction in the U.S. with then-President Obama using an analogy of a “new Sputnik impact.” Thus, a new round of comprehensive education reform was started in the U.S. (Martens and Niemann, 2013).

Finally, regional economic development policies and the dominant framework of contemporary education policies are also important factors affecting PISA education reform. Michel (2017) used multi-country comparisons to analyze the role of PISA in the convergence of European education policies and proposed that PISA focuses on educational output and how students apply the knowledge and skills learned in school to their future work and society. Thus, PISA’s educational conceptual framework is closely related to the Lisbon Strategy of the European Union and has attracted the policy responses of European countries, widely promoting educational reform in EU countries with the goal of making Europe the most dynamic knowledge economy in the new century (Michel, 2017).

In Europe, it is particularly difficult to isolate the influence of PISA from the impact of the initiatives of the European Commission which have been more and more frequent and important in the last 10 years in the domain of education because of the implementation of the ‘Open Method of Coordination’ and the adoption of crucial policy recommendations. Indeed, the initiatives and recommendations of the OECD and the EU Council and Commission have become more and more intricate in recent years because of the reciprocal influence and closer cooperation of these two international institutions. (Michel, 2017, p. 207).

At the nation-state level, important driving forces for PISA-related education policy responses include the self-perception of each country and region on the education system, its own cultural traditions, and domestic political system and environment. Specifically, Martens and Niemann point out two crucial conditions for exploring factors that influence PISA’s effect on education reform. First, that the subject matter assessed by PISA is given weight in national discourse, and second, that a large gap between national self-perception and empirical outcomes can be observed. When the two conditions are met at the same time, PISA will have a great impact on education policies (Martens and Niemann, 2013). For example, the results of the first PISA test revealed the gap between Germany’s PISA performance and its self-image as an educational power, exposing the problems of the German education system in promoting social inequality and low efficiency in talent training. These catalysts helped the country launch comprehensive education reform under the influence of PISA (Xie et al. 2022). Similarly, in Switzerland and Norway, where education systems are considered to be among the best in Europe, students’ PISA scores fall short of national expectations, even though they are often well above the OECD average. The contradiction between national PISA scores and long-standing national attitudes has pushed education reform to the top of the political agenda and greatly increased pressure for education reform (Bieber and Martens, 2011.

Policy responses from external influences are heavily influenced by a country’s own cultural traditions and political systems. In other words, the socio-cultural traditions and political institutional background within a nation-state constitute the ‘translation’ framework for external influences to drive domestic policy responses (Xie et al. 2022). In their analysis of Norway’s PISA-related policy responses, Baird et al. (2016) found that the Nordic model, a cultural background factor promoted in Norway, has always placed great emphasis on ‘Education for all’ (EFA) and inclusion, which concurs with the PISA framework. In addition, the absence of the word ‘accountability’ in the Norwegian language and the country’s traditional support for strong autonomy of schools and municipalities may also have influenced the policy response in the country (Baird et al. 2016). In the case of South Korea, Kim and Choi (2023) observe that the country’s policy response incorporates characteristics different from those of many Western countries. They believe that this is closely related to the political structure and background characteristics of South Korea. Specifically, the South Korean government already has a very strong presence, and emerging actors such as the education governor are decentralizing education policy. At the same time, teachers and parents counterbalance the power of the government through strong unions and frequent elections, while private enterprises’ involvement in education is taboo (Kim and Choi, 2023). Domestic politics are critical in shaping policy responses. Ruling parties advocating globalization and a neoliberal reform agenda tend to respond positively to PISA (Xie et al. 2022).

From the perspective of internal actors, key factors influencing the effect of PISA education reform include the actions and political opinions of domestic political groups and their policy consensus to implement effective improvements to domestic problems. The actor-network theory points out that although international organizations can be regarded as important policy actors in the global political field, their influence on a country’s policy making is the result of dynamic tussling between the subjects embedded in the policy network in a specific social environment. For historical and institutional reasons, the ‘national science’ produced by the French central administrative elite remains strong, and the government and official scholars remain legitimate and authoritative sources of knowledge. The PISA tests have awakened a spirit of reform among political forces. International comparative statistics and assessments have stimulated extensive public debate on the shortcomings of the French system by providing examples of foreign best practices and provided justification for specific educational policy reforms (Dobbins and Martens, 2012). The U.S. school system is highly decentralized, and the federal government has little influence in the field of education, which prevents it from responding immediately to PISA (Engel and Frizzell, 2015). In Finland, the interpretation of PISA results tends to favor those responsible for actions within the central government, and the superior academic performance of Finnish students is believed to be the result of educational reforms and decisions made by the central government. The deficiencies of Finnish students were attributed to the behavior of other agents (Rautalin and Alasuutari, 2009). In general, from the level of internal actors, there are at least two factors affecting PISA education reform. First, whether PISA provides a new conceptualization method for national decision-makers, and second, whether it can justify the policy direction that has been chosen. Based on this, some scholars have started to pay attention to political factors in the application of PISA results, such as:

In justifying the argument that PISA is a reliable barometer of the national educational systems, the central government officials’ texts particularly emphasize PISA’s scientific nature. In so doing, it is repeatedly contrasted with many earlier international studies, which are deemed political in nature. Thus, scientificity is used as a self-evident premise on which the argument of PISA’s reliability is built. The institution of science is invoked as a guarantee that the reports published are not compromised by what interested parties consider to be politically desirable research results (Rautalin and Alasuutari, 2009, p. 546).

The excerpt above suggests that the building of a specific mechanism model of policy impact should start from the three dimensions of supranational, nation-state and internal actor network levels, placing national policy responses in the global education field for consideration. At the outermost supranational level, OECD ideas do not invariably translate into national policy: “The transmission of [transnational] ideas is an active process, and ideas are formed and transformed in different ways in different contexts. Policy paradigms are disseminated at the international level, and international organizations play an important role in the dissemination of policy ideas.” The OECD and other international organizations adopt a soft governance model to assess the domestic education policy performance of countries by quantifying the link between PISA scores and the economic development of nation-states, working to promote the ‘best mode’ (Baird et al. 2016). The OECD makes PISA-participating countries part of an international cognitive community in which education policies and their goals and approaches are discussed using the same concepts and scores (Rautalin and Alasuutari, 2009).

At the intermediate nation-state level, PISA and its international rankings set up model societies for policy borrowing (that is, the transfer of policy from one country to another). In other words, PISA provides an institutional template for countries to follow in implementing education reforms and suggests alternative policy options. Finland’s education system is a reference society that has received much attention through PISA. Other countries and regions with high PISA rankings, such as Japan, Shanghai, and Hong Kong, are also being regarded as new model societies (Kim and Choi, 2023; Sellar and Lingard, 2018). At the most internal level of the network of actors, studies have confirmed that PISA’s promotion of education reform depends on the translation and transmission of the information contained in PISA through national policy networks, involving policymakers and members of political parties, associations, and the media (Schleicher, 2017). Thus, the specific mechanism of the impact of PISA-related education policies is driven by the international political background established by the supranational OECD, the policy borrowing behavior from model societies at the nation-state level, and the effective information translation of internal actor networks (see Fig. 2 and Table 4).

Conclusion

This study systematically reviewed the literature on the impact of PISA on education reform and explored three core research questions in depth. First, regarding the main characteristics of PISA affecting policy research, we find that the research covers the macro, meso, and micro decision-making levels, involving the education systems of multiple countries and regions. The research objects include policy documents, educational reform measures and concrete implementation effects. Research methods and designs are diverse, combining quantitative and qualitative analysis, including cross-country comparisons, case studies, and analysis of policy texts. The conceptual framework and theoretical model mainly focus on the two core dimensions of “quality” and “equity” and explore how PISA can promote education reform by influencing the education system. Secondly, the core issues of PISA’s impact on education reform are mainly reflected in its advocacy of neoliberal educational values, concepts of competence and literacy, and the pursuit of an ideal society. By providing internationally comparable data, PISA prompts countries to rethink their education systems and take steps to improve the quality and equity of education. PISA focuses not only on students’ knowledge and skills in reading, math, and science but also on the real-life application of these skills and the impact of education systems on socioeconomic inequality. Finally, the impact of PISA on national decision-making is constrained by a variety of factors. These factors include the date of the PISA results, the socio-economic and socio-political outlook of the ruling party, globalization and changes in educational needs, and the historical, sociological, political, and cultural context of the country. In addition, the role of international organizations in the global dissemination of policy paradigms and ideas, transnational pressures, the international situation, regional economic development policies, and the prevailing framework of contemporary education policy are also important influencing factors. At the nation-state level, the self-perception of the education system, cultural traditions, domestic political system, and environment also have a significant impact on PISA results. Therefore, the promotion effect of PISA on education reform is realized under the joint action of three levels: supranational, nation-state, and internal actor-network, and the specific effect depends on the comprehensive effect of these factors.

Discussion

This systematic literature review explored the effect of PISA on global basic education reform by focusing on three core themes: the main characteristics of PISA’s impact on policy research, PISA’s impact on education reform, and the factors influencing PISA’s effect. Based on the value orientation underlying PISA, the paper analyzed PISA’s impact on education reform and showed the two-way interaction between PISA and education reform. Through building a specific mechanism model of PISA’s influence on the development of education policies, this paper aimed to describe current empirical research on the effect of global basic education reform brought about by PISA. The review will serve as an information reference for promoting future empirical analysis of the effect of global basic education reform based on PISA.

PISA drives policy discussions on education quality and equity in countries around the world through its quantitative pursuit of education quality, data-based comparative analysis, and evidence-based research paradigms. On the one hand, the PISA ranking serves as a comparative benchmark for nation-states to measure their own education levels in the world. On the other hand, PISA data are used as a reference for countries to promote education improvement. In addition, from a global perspective, PISA’s reform effect on global basic education is closely related to the current operating mechanism of global education governance, and it serves as an important policy tool for the OECD to participate in global governance. Research shows that with continuing globalization, PISA is increasingly recognized by the international community. The assessment has gone far beyond its original function of measuring the quality of education among countries or regions and profoundly affects the pattern of global education governance through ‘soft’ governance. Specifically, the impact of PISA at the macro level of basic education policy is related to the choice of the reference society of the nation-state. Some countries have established ties with the OECD by implementing PISA and making their education affairs part of the national economic policy and international affairs agenda, helping their country become part of a global governance complex for sustainable development (see Fig. 3).

We argue that to accurately understand the policy responses of nation-states (with their unique historical, social, political, and cultural factors) to PISA, it is necessary to consider the responses of countries in the context of the global education field framework model. That model comprises three levels of supranational, nation-state, and internal actor-network. Within the nation-state level, political actors embedded in policy networks, and associations, and media, become important in shaping the actual political and policy agenda. Within and outside the nation-state (i.e., the supranational global education policy field), supranational organizations or institutions represented by the OECD (and the model societies established through their available capital) also have an indirect impact on national education policies. Cultural, historical, and institutional contexts must also be considered. The specific mechanism model of PISA’s impact on the development of education policies established in this study helps to show the two-way interaction between PISA and education reform, reveal the internal mechanism of PISA’s impact on education reform, and provide a theoretical reference for future academic research on the effect of education reform triggered by PISA.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. The current scope of research on the effects of global basic education reform and PISA is mainly focused on European countries. Thus, the review does not accurately reflect the situation in other regions and countries worldwide. Such regional limitations prevent us from obtaining a full understanding of PISA’s effects on a global scale. Cultural bias should also be considered regarding the selection of reference societies by nation-states and the process of external policy reference. Shanghai’s high PISA scores, for example, have sparked urgency in some Western countries to pay more attention to educational practices in Asia. However, these Western countries may still be affected by cultural biases that cause them to prefer to look to non-Eastern cultural contexts for reference. Therefore, when studying PISA effects and global education reform, we need to carefully consider the influence of regional differences and cultural factors to ensure that research findings and policy recommendations fully reflect the needs and contexts of different countries and regions.

References

Acosta F (2020) Systematic reviews in educational research: methodology, perspectives and application. Eur Educ 52(2):87–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/10564934.2020.1725390

Baird J-A, Isaacs T, Johnson S, Stobart G, Yu G, Sprague T, Daugherty R (2011) Policy Effects of Pisa. Oxford University Centre for Educational Assessment

Baird J-A, Johnson S, Hopfenbeck TN, Isaacs T, Sprague T, Stobart G, Yu G (2016) On the supranational spell of PISA in policy. Educ Res 58(2):121–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2016.1165410

Bieber T, Martens K (2011) The OECD PISA Study as a Soft Power in Education? Lessons from Switzerland and the US. Eur J Educ 46(1):101–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3435.2010.01462.x

Choi Á, Jerrim J (2016) The use (and misuse) of PISA in guiding policy reform: the case of Spain. Comp Educ 52(2):230–245

Dobbins M, Martens K (2012) Towards an education approach a la finlandaise? French education policy after PISA. J Educ Policy 27(1):23–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2011.622413

Engel LC, Frizzell MO (2015) Competitive comparison and PISA bragging rights: sub-national uses of the OECD’s PISA in Canada and the USA. Discourse Stud Cult Polit Educ 36(5):665–682. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2015.1017446

Gillis S, Polesel J, Wu M (2016) PISA Data: raising concerns with its use in policy settings. Aust Educ Res 43(1):131–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-015-0183-2

Grek S (2009) Governing by numbers: the PISA “effect” in Europe. J Educ Policy 24(1):23–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930802412669

Grek S (2010) International Organisations and the shared construction of policy ‘problems’: problematisation and change in education governance in Europe. Eur Educ Res J 9(3):396–406. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2010.9.3.396

Hartong S (2012) Overcoming resistance to change: PISA, school reform in Germany and the example of Lower Saxony. J Educ Policy 27(6):747–760. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2012.672657

Kim Y, Choi T-H (2023) The influence of the Programme for International Student Assessment on educational governance situated in the institutional setting of South Korea. Policy Futur Educ. https://doi.org/10.1177/14782103231192741

Lame G (2019) Systematic literature reviews: an introduction. Proc Des Soc: Int Conf Eng Des 1(1):1633–1642. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/proceedings-of-the-international-conference-on-engineering-design/article/systematic-literature-reviews-an-introduction/40D4CEA7A7CC3FB6ED6233E79A0A2A1F

Lawn M (2003) The ‘Usefulness’ of learning: the struggle over governance, meaning and the European education space. Discourse: Stud Cult Politics Educ 24(3):325–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/0159630032000172515

Madsen M (2022) Competitive/comparative governance mechanisms beyond marketization: a refined concept of competition in education governance research. Eur Educ Res J 21(1):182–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904120958922

Martens K, Niemann D (2013) When do numbers count? The differential impact of the PISA rating and ranking on education policy in Germany and the US. Ger Politics 22(3):314–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2013.794455

Meyer H-D, Benavot A (2013) PISA, power, and policy: The emergence of global educational governance

Michel A (2017) The contribution of PISA to the convergence of education policies in Europe. Eur J Educ 52(2):206–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12218

Morris P (2015) Comparative education, PISA, politics and educational reform: s cautionary note. Comp: A J Comp Int Educ 45(3):470–474

Neumann K, Fischer HE, Kauertz A (2010) From PISA to educational standards: the impact of large-scale assessments on science education in Germany. Int J Sci Math Educ 8(3):545–563. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-010-9206-7

Newman M, Gough D (2020) Systematic reviews in educational research: methodology, perspectives and application. In: Zawacki-Richter O, Kerres M, Bedenlier S, Bond M, Buntins K (eds) Systematic reviews in educational research: methodology, perspectives and application. Springer Nature, pp. 3–22

Niemann D, Martens K, Teltemann J (2017) PISA and its consequences: shaping education policies through international comparisons. Eur J Educ 52(2):175–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12220

Ninomiya S (2019) The impact of PISA and the interrelation and development of assessment policy and assessment theory in Japan. Assess Educ: Princ Policy Pract 26(1):91–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2016.1261795

Pereyra MA, Kotthoff H-G, Cowen R (2011) PISA under examination: changing knowledge, changing tests, and changing schools. In: Pereyra M A, Kotthoff H-G, Cowen R (eds) Pisa under examination. Sense Publishers, Brill, pp. 1–14

Pons X (2017) Fifteen years of research on PISA effects on education governance: a critical review. Eur J Educ 52(2):131–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12213

Rautalin M, Alasuutari P (2009) The uses of the national PISA results by Finnish officials in central government. J Educ Policy 24(5):539–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930903131267

Rautalin M, Alasuutari P, Vento E (2019) Globalisation of education policies: Does PISA have an effect? J Educ Policy 34(4):500–522

Schleicher A (2017) Seeing education through the prism of PISA. Eur J Educ 52(2):124–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12209

Schleicher A, Zoido P (2016) The policies that shaped PISA, and the policies that PISA shaped. In: K. Mundy K, Green A, Lingard B, Verger A (eds) The handbook of global education policy, 1st edn. Wiley, pp. 374–384

Sellar S, Lingard B (2018) International large-scale assessments, affective worlds and policy impacts in education. Int J Qual Stud Educ 31(5):367–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2018.1449982

Sjøberg S (2015) OECD, PISA, and globalization: the influence of the international assessment regime. In Education policy perils. Routledge, pp. 102–133

Xiao Y, Watson M (2019) Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. J Plan Educ Res 39(1):93–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X17723971

Xie A, Li J, Ma F (2022) Understanding China’s policy responses to Pisa: using a ti and yong framework. Comp Educ. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2022.2157014

Yore LD, Anderson JO, Chiu M-H (2010) Moving PISA results into the policy arena: perspectives on knowledge transfer for future considerations and preparations. Int J Sci Math Educ 8:593–609

Zheng J, Cheung K, Sit P (2022) Insights from two decades of PISA-related studies in the new century: a systematic review. Scand J Educ Res. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2022.2148273

Funding

This study is funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for theCentral Universities (NO.1233300002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work: Jian Li. and Eryong, Xue; the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work: Jian Li, Eryong, Xue and Siyuan, Guo; Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: Jian Li, Eryong, Xue and Siyuan, Guo; Final approval of the version to be published: Jian Li and Eryong, Xue.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Xue, E. & Guo, S. The effects of PISA on global basic education reform: a systematic literature review. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 106 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04403-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04403-z