Abstract

Public health participation plays a significant role in reducing risks and protecting community members during public health emergencies, especially in China due to its pronounced population density and the imperative for concerted public coordination to achieve the goal of public health protection. Guided by social capital theory and conservation of resources theory, this study develops an analytical model to explore the effect of social media involvement on public health participation mediated by social support, social trust and social responsibility. A cross-sectional survey was executed and a total of 976 completed questionnaires were collected. Results reveal that (a) social media involvement positively predicts social trust, social support and social responsibility; (b) social trust and social support have positive influence on social responsibility and public health participation; (c) further analysis of the data confirms a two-step mediation model: social support and social trust mediate the effect of social media involvement on social responsibility; social responsibility further mediates the relationship between social media involvement, social trust and social support and the outcome variable public health participation. Findings suggest that only in a society with adequate social resources will people take an active part in social actions for common interests. The study extends our understanding of the vital role of social media in maintaining and growing social resources for community health goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

COVID-19 pandemic is an unprecedented health threat that affects society at large, hence personal protective measures may not be sufficient to stop the spread of this contagious disease. People’s public health behaviors, such as following the guidelines in public settings, and participating in collective activities that enhance the protective measures, are also crucial in the combat against COVID-19 pandemic. These public health behaviors are gradually cultivated during the pandemic as the combat against COVID-19 pandemic requires the public to participate in collective protective activities, and people increasingly understand the importance of these activities.

The issue of public health participation becomes especially relevant in the Chinese context because of its high population density and the need for public coordination to achieve the goal of public health protection when a large population is at risk of contracting COVID-19 virus (Cheng et al. 2021). Social media has been working as a main channel for information distribution and issue discussion concerning public health protection during COVID-19 pandemic (Tsao et al. 2021; Zeballos Rivas et al. 2021). However, while the effects of social media use on protective behaviors have been explored extensively since the outbreak of COVID-19 (Allington et al. 2021; Mat Dawi et al. 2021), few of them looked into how social media use would affect public health behaviors from a collective perspective.

Social resource factors play crucial roles in the process of advancing social causes and promoting public interest by facilitating collaboration, mobilizing support, and fostering collective actions within communities and society (Seo et al. 2011). Key social resource factors include social networks, trust, social support, and social responsibility. The social resource factors are even more central when a large population needs to be mobilized to participate in collective actions fighting the COVID-19 pandemic and work for the common goal of public health protection. However, the relationship between social media use and social resource building as well as how social resource factors work together to facilitate the effect of social media use on public health behaviors during COVID-19 pandemic, an event involving high societal stress and calling for collective efforts remains largely unknown.

Given the importance of promoting public health behavior when facing public health emergencies, this study examines social media use as a resource-building process, how social media use facilitates social resource building, and how social resource factors work together to enhance the effect of social media use on public health behaviors during COVID-19 pandemic. The findings will shed light on how social media use affects public health behaviors through the social resource factors from a resource conservation perspective. It will extend our understanding of public health participation in the situation when the whole society is facing a public health threat and all members of society need to take collective actions to protect themselves and their communities, and reveal the underlying motivations associated with such actions within the collectivist Chinese society.

Literature review

Social capital as social resources in combating COVID-19 pandemic

COVID-19 pandemic poses a threat to all members of society, and calls for both individual and collective actions, which require individual engagement, social trust, and support as well as community coordination to effectively mitigate its impact, foster resilience, and ultimately overcome the crisis. Social capital theory provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the dynamics of social relationships, social resources, and collective action within communities and societies. Social capital refers to the sum of the actual and virtual resources accumulated by possessing a durable network of relationships (Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992). It encompasses the resources and benefits that individuals and communities obtain through social networks, based on shared norms that foster collaboration, such as trust and reciprocity (Besser, 2009; Borgonovi and Andrieu, 2020). An individual’s social network is regarded as an intrinsic asset that bears social resources like social trust and social support (Martin et al. 2020). As a key element of social capital (Ferlander, 2007; Liu et al. 2016), social networks facilitate social ties and capital accumulation (Wellman et al. 2001; Ellison et al. 2007) through online and social media interactions, and play an essential role in building social capital during stressful times, such as COVID-19 pandemic (Zhong, 2014). Scholars have found a significant association between social media use and social capital (Aubrey and Rill, 2013; Ellison et al. 2007; Pang, 2022).

Social capital manifests its positive impact in the face of contagious diseases, particularly when collective behavioral changes become crucial (Bartscher et al. 2021). Previous research on social capital during the pandemic explored the relationship between social capital and individuals’ responses to the pandemic and found that social capital contributes to combating the spread of COVID-19 (Fraser et al. 2022; Makridis and Wu, 2021), and high social capital communities responded more efficaciously than those with low social capital (Bartscher et al. 2021). Social capital also cultivated self-discipline behaviors for COVID-19 prevention and control (Liu and Wen, 2021). These studies focused on health outcomes and found that social capital can significantly reduce mortality rates, highlighting its crucial role in controlling the progression of the pandemic (Borgonovi and Andrieu, 2020; Marziali et al. 2024). While these studies uncovered the role of social capital in combating the COVID-19 pandemic, they mostly examined social capital from a macro perspective, and focused on the COVID-19 response at the national, sub-national, or community level, making it difficult to pinpoint individuals’ behaviors and the underlying motivations driving them. When examining the effect of social capital, these studies often employed a composite index of social capital as the independent variable or focused on some dimensions of social capital, while neglecting other social resource factors that promote and reinforce pro-social behaviors during a stressful time (Elgar et al. 2020; Makridis and Wu, 2021). Furthermore, prior research has typically treated social capital as an exogenous variable, and failed to address the question of its upstream influencing factors (Borgonovi and Andrieu, 2020; Imbulana Arachchi and Managi, 2021). Exploring how social capital is cultivated by the use of social media and the effects of the key elements of social capital as social resources on public health participation on the individual level will produce new insights into how social resource factors motivate collective actions for community interests amidst public health crises.

Social media: enhancing social trust and social support

Social media helps establish connections between individuals and serves as a platform for activities such as information exchange and opinion expression (Boyd and Ellison, 2007; Tsao et al. 2021). During the COVID-19 pandemic, it has also become an essential channel for governments and organizations to disseminate information, motivating individuals to take protective actions (Allington et al. 2021). For many active users, social media involvement, participating in online communicative activities beyond mere information consumption, has become a daily routine (Lim et al. 2013). Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, social media provides both physical help and emotional support to reduce an individual’s stress. Social media involvement fosters stronger connections within the online community, enabling people to collaborate within their social networks (Haythornthwaite, 2012). Through social media, individuals engage in various social activities, build support systems, and communicate with people from diverse backgrounds. These interactions on social media contribute to the accumulation of social capital by developing close relationships and trust, leading to mutual assistance and collaboration (Kwon et al. 2021).

Research has also demonstrated that social media involvement is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, social media serves as a platform that facilitates easier establishment of connections, information sharing, and expansion of social circles, which help build up social capital (Ellison et al. 2007). Users with high social media involvement would perceive more trust and support (Lee and Cho, 2019; Lee et al. 2021). On the other hand, misinformation and fake news are prevalent on social media. Social media users are more likely to encounter conspiracy theories and misleading news compared to non-users (Sabatini and Sarracino, 2019), especially during the pandemic when social media provided fertile ground for unverified information (Ataguba and Ataguba, 2020). Dark participation, i.e., the malicious use of social media for activities such as spreading toxic discourse, hate speech, and misinformation, has caused negative effects on users’ social capital, such as well-being (Quandt et al. 2022) and social trust (Sabatini and Sarracino, 2019). Therefore, further examination is imperative to reveal the role of social media use in social capital building for individuals and society, especially in terms of social trust and social support.

Social trust is the belief that others will act in a trustworthy and cooperative manner, leading to positive social interactions and cohesion (Uslaner, 2023). Social trust is initiated and developed through involvement in activities of common cause and public interest (Delhey and Newton, 2003). In the context of COVID-19, social media would help gather people for the same objective to combat the pandemic and allow them to build social trust in the course of exchanging information for a common goal. Social trust fosters collaboration and support within communities. Individuals are more likely to help each other stay informed, share resources, and adhere to measures for public health protection. Numerous studies have shown that social media involvement can positively predict social trust, either directly or indirectly (Kwon et al. 2021; Warren et al. 2014).

Social support refers to the assistance and protections given to individuals by other social members as interpersonal ties (Cohen and Hoberman, 1983; Lin et al. 1979). Social support is the assistance rendered to other members who are in the same social system as a result of social interactions (Wang et al. 2019). Individuals obtain social support through social media from both close and non-close relationships (Rozzell et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2019). Researchers believe that social networks are fundamental to social support as well as the vehicle for the provision of social support (Langford et al. 1997). Social media involvement enables users to sustain and enhance social connections, providing valuable resources and support, especially when face-to-face interactions are limited. It can be a comfort source for those facing issues like illness, isolation, or emotional stress (Utz and Breuer, 2017). Studies of social media use have confirmed its effect on perceived social support, and found that social media use significantly predicts informational, instrumental and appraisal support (Lee and Cho, 2019).

Conservation of resources (COR) theory, along with social capital theory, provides an additional theoretical explanation of how individuals navigate stressful situations, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, and why people perceive increased social support and social trust following social media involvement about the pandemic. Both theories underscore the importance of resources, but they emphasize different aspects of these resources. Social capital theory highlights the role of social networks and relationships in creating and maintaining resources, particularly social trust and social support. It explains how these resources can be accumulated through interactions within social networks and how they can be used to address problems and achieve positive outcomes in communities and societies. COR theory emphasizes the imperative need for individuals to build, protect and manage resources when personal and environmental resources are depleted under threatening or disruptive situations (Halbesleben et al. 2014). Individuals engage in resource conservation by amplifying resource acquisition and minimizing resource loss (Halbesleben et al. 2014). These resources are crucial for addressing problems and achieving positive outcomes in challenging circumstances.

During stressful circumstances such as the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals face significant stress and adversity, and they have to find ways to protect and build their resources to cope with these challenges and mitigate the losses. When people are advised to keep social distance and reduce offline activities, social media becomes a platform for people to acquire resources and deal with stressful situations as an online community (Houston et al. 2015; Jurgens and Helsloot, 2018). People use social media as a way of resource investment to build social trust and maintain social support. Their involvement in resource acquisition allows them to alleviate stress and navigate the challenges of resource scarcity (Hobfoll, 2001). Through the lens of these two theories, we can see how social media has become an important platform for individuals to build and maintain social capital during the pandemic (Borgonovi and Andrieu, 2020). Social media allows individuals to connect with others, share information, and seek support, which help them build social trust and social support. At the same time, individuals are using social media to build and manage resources needed for solving problems during the COVID-19 pandemic. We therefore propose the following hypothesis:

H1: Social media involvement positively predicts (a) social trust and (b) social support during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Public health participation predicted by social trust and social support

The severity of COVID-19 epidemic and the need for high efficiency of preventive measures in large-scale disasters call for public health participation. In this study, public health participation emphasizes the initiatives that one takes in response to local community’s call for collective actions to fight against COVID-19 pandemic. Public health participation such as taking specific measures to assist and reinforce pandemic control for the community is crucial for risk reduction and community protection. Doolittle and Faul (2013) identified two dimensions of public participation, civic attitudes and civic behaviors. This study explores the behavioral aspect of public health participation, which is considered an investment of valuable resources (e.g., time, knowledge, or experience) in community interest for epidemic prevention. More specifically, actions involve taking personal responsibility and proactive initiatives to facilitate, support, and contribute to the community’s pandemic control efforts. Engaging in prosocial behavior in response to stress could be an effective stress-buffering strategy for people (Von Dawans et al. 2012). Public participation has been studied extensively in different contexts as a form of dutiful citizenship performance (Johnson et al. 2014; Zavestoski et al. 2006).

Public participation requires a variety of resources (Warren et al. 2014). Research has demonstrated that social capital is positively associated with public participation (Besser, 2009; Kim, 2007; Zhong, 2014). When individuals within a group share norms and values, such as mutual trust and support, they possess a type of social capital that promotes pro-social behavior and civil participation (Sabatini and Sarracino, 2019; Lee et al. 2021). When society is facing some challenges, individuals’ behavior could be influenced by level of social capital. Individuals living in high level communities followed more strictly than those in low level communities the control measures and resulted in less severe health outcomes because of COVID-19 (Borgonovi and Andrieu, 2020). Both social trust and social support as social capital played significant roles in influencing public health participation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Social trust establishes a necessary environment for people to cooperate on public issues and facilitates the completion of tasks that need public participation through collective activities (Kwon et al. 2021; Valenzuela et al. 2009). Trust in social networks encourages open communication and collaboration, which further promotes public health participation and collective actions. Individuals who trust that their peers adhere to public health guidelines and support collective efforts are more likely to collaborate, coordinate efforts, and mobilize resources to effect positive change (Kar et al. 2023). When people trust their community members’ commitment to public health goals, they feel responsible and obligated to participate in mask-wearing, social distancing, and community support activities (Siegrist et al. 2021). Individuals who feel a sense of trust and belonging within these online communities are more inclined to participate in pro-social activities (Brehm and Rahn, 1997; Kelly, 2009).

Social support is also found to be related to three indicators of civic participation, breadth, intensity and sustainability (Pavlova et al. 2015). Social support plays a critical role in motivating individuals to engage in public health participation. Studies found that perceived social support was positively associated with health participation (Guan et al. 2021; Xin and Li, 2022). Social support can provide individuals with the encouragement, reassurance, and sense of belonging needed to overcome barriers to participation and take active roles in public health efforts like joining the majority for community pandemic control (Zhu and Hu, 2023). The following hypothesis is thus proposed:

H2: Social trust (a) and social support (b) positively predict public health participation.

Predictors of social responsibility

While social trust and social support facilitate civic participation behaviors and encourage people to take actions to join the collective actions to solve problems concerning public interest, the attitude or willingness to participate in voluntary service in one’s community and help others in the community does not necessarily lead to actual behaviors because of the “value-action discrepancy” (Arbuthnott, 2009; Blake, 1999). Amid COVID-19, this gap widens due to the virus’s contagious nature, dissuading participation in risky civic behaviors like community volunteering. Such discrepancy between an identified value and actions taken regarding public interest might be reduced by perceived social responsibility (Robin and Reidenbach, 1987). From the perspective of dutiful citizenship, social responsibility is also important for any individual in civic society. In the case of COVID-19, social responsibility refers to individuals’ concern for epidemic prevention beyond self-interest and consciousness of duty in contributing to the common goal of society (Cheng et al. 2021).

People with higher social capital usually demonstrate greater social responsibility (Bartscher et al. 2021). A high level of social trust often reflects a shared understanding of societal values and norms, including expectations of responsible behavior, and results in increased social responsibility as individuals feel a sense of duty toward their community and society (Meredith et al. 2007). Social trust engenders a sense of duty, promoting collective actions to solve community problems (Wang et al. 2020). This, in turn, leads to greater social responsibility and civic engagement (Delhey and Newton, 2005; Mellor and Freehills, 2018).

Social support relies on reciprocity, with individuals feeling obliged to reciprocate kindness and care. This sense of responsibility arises from maintaining social bonds and supporting peers (Lachowicz-Tabaczek and Kozłowska, 2021). Social support also provides a sense of belonging and connectedness which can motivate people to act in ways that benefit others (Baumeister and Leary, 1995; Eisenberger, 2013). Belonging sense often leads individuals to perceive a greater sense of responsibility towards their social networks and communities, as they recognize the importance of reciprocating the support they have received and contributing to the well-being of others in return (Xu et al. 2021). Research has shown that when individuals receive more emotional and instrumental support from their social networks, they are more likely to engage in prosocial behaviors (You et al. 2022), take on social responsibilities (Ferlander, 2007) and contribute positively to society (DeSteno et al. 2010). Social support can also provide individuals with the necessary resources and skills needed to fulfill their social responsibilities (Fu et al. 2022).

Social media has been playing an increasing role in advancing pro-social norms and activating social responsibility. People discuss a variety of topics on social media, and such discussions often lead to a common understanding of a social cause concerning public interest (Han et al. 2020). Social media use is significantly related to public discourse that shapes the shared beliefs and norms of society (Ye et al. 2017). Numerous studies found that social media use for information contributes to increased levels of civic engagement (Kim and Chen, 2015; Loader et al. 2014; Skoric et al. 2016). While social media use promotes the activation of social responsibility, a key element that leads to civic engagement, the relationships between social media involvement and social responsibility have yet to be further explored. Thus we proposed the following hypotheses:

H3: Social trust (a), social support (b) and (c) social media involvement positively predict social responsibility.

A two-step mediation model

As discussed earlier, social media enables people to build online social networks where people get to know more people who may have similar opinions, backgrounds and interests. Regular information sharing and exchange of ideas help build trust. Social networks are also fundamental to social support with material or emotional help against hardship in life. Therefore, social media involvement is a process of building social resources and is expected to positively predict social trust and social support.

Liu and Li (2021) found that the discrepancy between people’s environmental concern and their pro-environmental behavior is mediated by perceived responsibility. The mediating effect of responsibility on the relationship between social resources and actual behavior has been found in some social settings (Jackson and Wade, 2005). The development of social responsibility relies on social resources (Pavlova et al. 2015). While the relationships between social resources such as social trust, social support and social responsibility have yet to be fully explored (Cheng et al. 2021; Flanagan, 2003), it could be expected that social responsibility would arise as a positive return of social trust and social support.

Awareness of social responsibility influences peoples’ compliance behavior in fighting COVID-19 (Nielsen et al. 2020; Shanka and Gebremariam Kotecho, 2021), and concerted actions helpful for the common good. Thus, it is reasonable to infer that social trust and social support as resources gained during the epidemic are likely to exert an effect on perceived social responsibility, and would further influence public health participation through social responsibility. The following hypotheses are proposed:

H4: The effect of social media involvement on social responsibility is mediated by social trust (a) and social support (b).

H5: The effects of social trust (a), social support (b) and social media involvement (c) on public health participation are mediated by social responsibility.

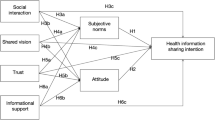

According to social capital theory, social resources can be accumulated through interactions on social media as the social network expands. An individual’s involvement in information exchanges about the epidemic on social media helps form and strengthen social connections with others, thereby build social resources. Through the lens of COR theory, social media involvement is also a way of resource investment to gain new resources such as social responsibility to solve problems faced by communities, and eventually lead to public participation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on the theoretical framework, we develop an analytical model to examine the effects of social media involvement, social trust, social support and social responsibility on public health participation (Fig. 1).

Method

Participants

After obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board, a cross-sectional survey was conducted during 14–17 April 2022 in China to test the hypotheses. China was carrying out the “dynamic zero” policy because of the escalating threat of the COVID-19 pandemic, and dozens of cities including megacities such as Shanghai with a population of 25 million were locked down at that time. The population for this study is the general media users in China. The study was executed by a marketing company, which maintained a pool of 6.2 million media users from all provinces in China. With the consideration of the response rate of online surveys normally at 10% (Kaplowitz et al. 2004) and the number of questionnaires to be completed set by the budget, a sample was randomly drawn from the subject pool. To make sure that the marginal distributions of sex and age match those of the population, quota sampling was used (Futri et al. 2022) based on the demographics of China’s population. The link to an online questionnaire was sent to a panel with a cover letter inviting the respondents to fill out a questionnaire online regarding their thoughts and behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. The respondents were informed of the confidentiality and anonymity of the survey. The IP addresses of all respondents were tracked for their locations and the time used to fill out the questionnaire to ensure the validity of the responses. A total of 976 completed questionnaires were collected.

The subject pool of the service provider and the population of Chinese general media users share some similar attributes. Among the 976 respondents who completed the survey, 51.2% were female, and 48.8% were male, close to the gender ratio of the general media users in China (49.2% female and 50.8% male) (CNNIC, 2024). The average age of the respondents was 30.24 (SD = 6.69), younger than that of the general media users in China (36.74%). The majority (87.1%) had a college degree, about 9% attended graduate school, and 4.9% had a middle school education. Nearly sixty percent (57.48%) of the respondents reported a household monthly income above CNY 10,000 (USD 1445), followed by 36.79% earning CNY 4000–9999 (USD 578–1444) and 5.73% earning below CNY 3999 (USD 577).

While the age and education distribution of the sample may not be ideal for generalizability, and could potentially introduce bias into the outcome variables, this demographic could still be meaningful for studying public health participation. The data could provide valuable insights into public perception and behaviors during stressful situations. Younger age groups, such as those represented in the study are often more active in digital spaces and may have been more engaged in seeking and sharing information about the pandemic on social media. A higher education level could indicate a better understanding of public health issues, and a greater willingness to participate in public health initiatives. The respondents’ perspectives and behaviors will offer an illuminating understanding of how people use social media, acquire and maintain social resources, and act upon calls for public health participation.

Measurements

The measurement of the variables was adapted from previous studies. Each variable was checked with a reliability test to ensure internal consistency. The Chinese translation of the questionnaire was checked and validated by three bilingual researchers. The perceptual and attitudinal variables were measured with a 5-point Likert scale, and behavioral variables were measured with a 5-point verbal frequency scale. The Cronbach’s α for all variables is higher than 0.6, indicating that all measurements are suitable for further data analysis (Ariffin et al. 2010; Hajjar, 2018).

Social media involvement was measured on how often respondents use social media platforms to communicate with others (Boyd and Ellison, 2007) regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. The four items gauged the following activities about the pandemic: (1) talk to others, (2) pay attention to, (3) post messages, and (4) relay messages. The items were added and averaged to compute the value of social media involvement in the issues concerning the COVID-19 pandemic (M = 3.38, SD = 0.743, α = 0.640).

Social trust was measured with four items on the faith in the people around during the COVID-19 pandemic adapted from Woelfert and Kunst (2020), including most people are 1) trustworthy, 2) kind-hearted, 3) willing to help others, 4) wary of others. The 4th item was reverse-coded. The items were added and averaged to compute a score of social trust (M = 3.66, SD = 0.650, α = 0.697).

Social support was measured with five items on the assistance and comfort received from other people during the COVID-19 pandemic adapted from Seiter and Brophy (2022), including 1) each time I am in need, someone will help, 2) people around always stick with me through thick and thin, 3) when I fall in the blues, someone will comfort me, 4) I always have someone to rely on when in difficulty, 5) someone will always be there when I make important decisions. The items were added and averaged to compute a score of social support (M = 3.74, SD = 0.763, α = 0.822).

Social responsibility was measured with four items on the consciousness of one’s duty for pandemic control during the COVID-19 pandemic adapted from Liu and Li (2021), including 1) I have the responsibility to join pandemic containment, 2) it is my duty to work for pandemic containment, 3) when pandemic containment calls, I am happy to work without pay, 4) I take my responsibility in pandemic control for the community. The items were added and averaged to compute a score of social responsibility (M = 4.43, SD = 0.489, α = 0.646).

Public health participation. To measure respondents’ initiatives and involvement in pandemic control of the community, respondents were asked to report how well each of the following statements reflected their behaviors in joining pandemic containment during the COVID-19 pandemic. The three items are “I have taken initiatives to do something that facilitates pandemic control for the community,” “I have spent time to work for pandemic containment for the community,” and “I have made efforts in assisting pandemic control for the community.” The results were averaged to create a score of public health participation (M = 4.16, SD = 0.640, α = 0.681).

Demographic variables such as age, gender, and education often influence the outcome variable even if they are not the primary focus of the study (Sirgy, 2021). To isolate the impact of the key variables on public health participation, age, gender, education, and monthly income were treated as control variables.

Results

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted using AMOS 22 to analyze the data. First, conformity factor analysis was conducted to assess the internal consistency of each variable. If AVE is less than 0.5, but CR is higher than 0.6, the convergent validity of the construct can be adequate (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). The AVEs of all key variables are around 0.5, and CRs are higher than 0.7, indicating that the measurements achieve acceptable convergent validity. The CR, AVE, and factor loading of each variable are presented in Table 1.

Then we further conducted SEM to test the hypothesized model. The demographic data (i.e., gender, education, and age) were added to the initial model as control variables. The results showed that gender, education, and age did not have significant effects on social media involvement, hence they were removed from the final model. To assess the model fit, the standards of the model fit index were applied with TLI, CFI, GFI higher than 0.9, and RMSEA lower than 0.05 (Ahmad et al. 2016). The results of structural equation modeling showed that the data fit the model well: χ2 (213) = 504.669, p < 0.001; TLI = 0.939, CFI = 0.949, GFI = 0.953, RMSEA = 0.037. The path coefficients are presented in Fig. 2.

H1 posited that social media involvement positively predicts social trust and social support. Results indicated that social media involvement was significantly related to social trust (β = 0.29, p < 0.001) and social support (β = 0.447, p < 0.001), thus H1 is supported. Besides, social media involvement also had a significant impact on social responsibility (β = 0.141, p < 0.01).

H2 postulated that social trust (a) and social support (b) have positive influence on social responsibility, Results indicated that social trust (β = 0.295, p < 0.001) and social support (β = 0.270, p < 0.01) positively predicted social responsibility. H2 is supported.

H3 posited that social trust (a), social support (b) and social media involvement (c) have positive influence on public health participation. Results indicated that the effect of social trust on public health participation (β = −0.099, p > 0.05) was insignificant. Social support (β = 0.257, p < 0.001) had a moderate positive effect on public health participation, while social media involvement (β = 0.795, p < 0.001) had a strong positive effect on public health participation. Thus H3b and H3c are supported, while H3a is rejected (Table 2).

Bootstrapping (N = 2000, confidence level = 0.95) was used to test the mediation effects. H4 proposed social support and social trust are mediators between social media involvement and social responsibility. Data showed both social support (β = 0.072, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.044, 0.105]) and social trust (β = 0.046, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.027, 0.072]) mediated the relationship between social media involvement and social responsibility, thus H4 is supported.

H5 posited that social responsibility mediates the relationship between social trust (a), social support (b), and social media involvement (c) and the outcome variable public health participation. The results suggested that social responsibility was a mediator between social media involvement (β = 0.146, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.103, 0.199]), social trust (β = 0.258, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.181, 0.361]), social support (β = 0.199, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.135, 0.283]) and public health participation. The proposed two-step mediation model is supported by data. The direct and indirect effects among variables are summarized in Table 3.

Discussion

Informed by social capital theory and conservation of resources theory, this study tested the effects of social resource factors on public health participation at a highly stressful time during the COVID-19 pandemic. Different from previous studies which focused more on individual prevention measures, this study explores the social influence on individuals’ behavior concerning public health and community pandemic control, and offers new insight into how social factors motivate people to participate in collective actions for common community interest.

The level of public health participation was notably high, reflecting the strong motivation of individuals when confronted with a severe situation demanding community-wide involvement. Such participation serves the interests and well-being of both the community and individuals amidst a highly contagious environment. The frequent encouragement through public service announcements, coupled with the recognition of the collective impact on containing the pandemic, inspired individuals to join the public health campaign, resulting in a high level of actual participation.

Besides, the results support the proposed two-step mediation model: Social trust and social support mediate the relationship between social media involvement and social responsibility; social responsibility further mediates the relationships between social trust, support and public health participation. The findings not only reveal the positive predictors of public health participation behavior, but also extend the understanding of the psychological reaction process towards health information on social media, and make important contributions to both social capital theory and conservation of resources theory.

Theoretical advances

Social capital theory emphasizes the importance of social networks, trust, and support in facilitating cooperative behavior for community well-being. This study tested the effects of social resources, specifically social trust and social support, on public health participation during the COVID-10 pandemic. The findings indicate that social trust and social support as components of social capital both play essential roles in public health participation. When social actions call for the public to join, social resources such as social trust and social support are indispensable to motivate the public. Social resource availability becomes a powerful influencing factor for the success of social action (Xue et al. 2022). The findings indicate that only in a society with adequate social resources will people take an active part in social actions for common interests. Social trust and social support demonstrate their essential roles in encouraging public health participation.

Prior research has typically treated social capital as an independent variable influencing community well-being, with limited exploration of its upstream influencing factors (Borgonovi and Andrieu, 2020; Imbulana Arachchi and Managi, 2021). This study, however, offers evidence of how social media involvement can enhance social capital amidst public health crises. The findings illustrate social media’s role during crises as a powerful tool for social cohesion and capital accumulation. Social media not only facilitates the sharing of vital resources and information but also nurtures a sense of community and mutual support, which are indispensable for navigating and recovering from massive crises. By fostering real-time interactions and the dissemination of crucial information, these platforms facilitate the formation of support networks that transcend geographical boundaries. The collective action sparked by these online interactions contributes to the strengthening of social bonds and trust, which in turn motivates individuals to participate in public health initiatives.

The findings regarding social media’s impact on social trust and social support significantly advance the explanatory scope of social capital theory in the context of a public health emergency. Traditional frameworks of social capital often emphasize face-to-face interactions and stable social structures. However, the rise of social media demonstrates that social capital can be accumulated and mobilized through virtual communities and digital means, particularly during times of crisis when physical interactions are limited. This suggests that the way of social capital building is not static but rather dynamic and adaptable to technological advancements. Social media allows individuals to maintain and expand their social networks beyond their immediate social circles. The breadth and diversity of these networks enhance access to information, resources, and support, making social capital more resilient and effective in addressing complex societal challenges. Social media’s ability to disseminate information and coordinate collective action in real-time demonstrates its potential to enhance the efficiency and speed of resource allocation during crises. This can be particularly crucial in situations where rapid response is essential, such as natural disasters or health emergencies. By leveraging social media, communities can quickly mobilize resources, identify needs, and provide support to those most affected.

The majority of research on social capital or applying the COR theory concentrated on passive response to the COVID-19 pandemic, investigating how the pandemic affects social capital and its relationship with the spread of the disease, mortality rates (Borgonovi and Andrieu, 2020; Elgar et al., 2020) and individuals’ mental health (Wang et al. 2022; McElroy-Heltzel et al. 2022). In contrast, this study explores the proactive role of social capital and the conservation of resources in shaping public health behaviors. By examining these dynamics, the research aims to understand how social trust, social support, and social responsibility encourage individuals to adopt healthier practices and adhere to public health guidelines more effectively.

It is noteworthy that social trust has a higher impact on social responsibility than social support. The finding suggests that motivation to join public health activities starts from the positive expectation that other social members will act with reciprocity (Lee et al. 2021). Therefore, building social trust is crucial for COVID-19 prevention and control measures adoption and evoking people’s social responsibility. However, contrary to H3a, social trust was not found to have a significant impact on public health participation. One possible reason could be how social trust is measured. In this study, social trust was measured as general personal belief instead of specifically targeting COVID-19 context. While social trust during COVID-19 pandemic may not differ significantly from that in general, there could still be subtle differences due to the highly contagious nature of the pandemic. Previous research has indicated that unspecific measures of trust could result in a weak correlation between trust and perceived risks associated with COVID-19 (Siegrist and Bearth, 2021). In the COVID-19 pandemic context, social trust might alert people of the threatening situation, and encourage more active engagement in public health participation. Another possible reason could be the nature of public health participation, which concerns both community and personal interests and well-being during a highly contagious environment (Aresi et al. 2022). Public service announcements regularly encouraged people to participate in collective actions to combat the pandemic, potentially making public participation a conscious behavior that most people actively engage in, regardless of their level of social trust. Further tests are needed to verify the effect of social trust on public health participation.

The findings also demonstrate how conservation of resources theory can be applied to understand public health behaviors. Previous research has applied COR theory to analyze and explain organizational behaviors (Halbesleben et al. 2014). By focusing on social resources in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, this study significantly advances the COR theory in explaining how social resources influence collective actions for public interests, particularly in the context of a global pandemic. COR theory emphasizes the importance of resources in helping people navigate stressful situations. This study further identified social resources that work effectively in a public health emergency such as social trust and social support. The findings indicate that social resources can be acquired, maintained and regained through interaction with other community members, and provide empirical support for the role of social media in facilitating the accumulation and preservation of resources crucial for promoting community well-being. These social resources served as critical buffers against the stressors associated with the pandemic, and mobilized people to take public health initiatives. By participating in public health efforts, individuals could contribute to the collective well-being of their communities, which in turn reinforced their sense of resourcefulness and resilience.

Previous studies found that social media provides both physical help and emotional support to reduce an individual’s stress. This study goes further to examine social media’s role in building a broader spectrum of social resources and evoking social responsibility, which is crucial for motivating people to participate in collective actions to combat the pandemic. Social media will not only allow people to seek health information, and ask for health protection assistance (Liu, 2021), but also enable people to build online social networks where people can support each other during stressful times (Saud et al. 2020; You et al. 2023). Social media involvement becomes a part of the resource investment process, and helps maintain and build the resources that could be drawn in need (Lee and Cho, 2019; Lee et al. 2021; Utz and Breuer, 2017). The study thus provides empirical support for how the use of social media enhances social capital and how the resource investment facilitated by social media promotes public health participation, thereby advancing our understanding of how social capital theory operates in the digital age, and how conservation of resources can be realized through social media use.

Among all social factors, social responsibility has the strongest impact and works as an activator of collective actions that benefit all social members. When facing the threat of COVID-19, people not only have to take self-protecting behavior, but also need to care for others. Previous studies focused more on the influence of corporate social responsibility during COVID-19 pandemic (He and Harris, 2020; Qiu et al. 2021), the findings of this study suggest that individual social responsibility is also crucial for COVID-19 control and prevention, especially when public health participation is required with all people in the community involved. When the goal is set, the public is not necessarily motivated to join social actions to achieve the goal that benefits all (Wang et al. 2021; Vieira et al. 2023). Perceived social responsibility is crucial in motivating people to participate in public health activities (Lee et al. 2021). By encouraging ongoing public health participation, social responsibility enhances the effectiveness of social resources in addressing health crises and promoting long-term community well-being.

Additionally, the two-step mediation model delineates the process of how social media involvement facilitates public health behaviors through enhancing social resource factors. The finding that social responsibility mediates the relationship between social media involvement, social trust, social support, and public health participation underscores the interconnectedness of these resources and their synergy in enabling communities to mobilize quickly, share information effectively, and coordinate responses to health crises. The impact of social responsibility extends beyond immediate crisis response. By engaging in social media, individuals can foster a sense of community and responsibility, which in turn can lead to increased social support, trust, and public health participation, and further strengthen the social fabric and make communities more resilient in the face of adversity.

Although the hazard of COVID-19 is partially alleviated by vaccines and specific drugs, it is still a health threat throughout the world since it is highly contagious and mutable. In April 2022 when this study was conducted, China was still under the severe threat of COVID-19 spread and many parts of the country were under lockdown. High stress developed among people, and social resources and public health participation for COVID-19 prevention and control were needed for people to care for each other and the whole community. This study provides crucial empirical evidence to extend the understanding of social media involvement at a time when social connection is especially important for maintaining, building, and growing social resources to achieve the common goals of the communities in China.

Practical implications

The findings of this study have significant implications for practitioners in health departments and organizations. First, it is recommended to leverage social media platforms to disseminate accurate information, promote health guidelines, and foster a sense of community and social responsibility. Health professionals should rely more on convenient and effective social media platforms to communicate with the public on health policy and prevention measures for COVID-19 and other infectious diseases. Second, building social trust within communities is crucial. Since social media involvement is positively related to social trust, social support and social responsibility, social media health campaigns can emphasize more on social support and social trust, and invoke individual social responsibility. Third, efforts should be made to enhance social support networks, both online and offline, such as community groups, neighborhood associations, and volunteer organizations. These networks can provide emotional support, practical assistance, and information, further boosting public health participation. Additionally, promoting the concept of social responsibility by highlighting how individual actions, such as following health guidelines and participating in community activities, contribute to the common good can encourage more active engagement in public health activities, especially during highly contagious contexts like the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore health communication campaigns regarding COVID-19 pandemic and other similar situations informing the public of infectious diseases should pay more attention to evoking individual social responsibility, such as emphasizing the goal attainment with collective efforts, and individuals’ roles and duties in the community’s well-being, to promote public interest and encouraging people to participate in public health activities.

Limitations and future research

The current study bears several limitations. First, the cross-sectional survey data in this study cannot confirm the causal relationships between the independent and dependent variables. Future experimental or longitudinal studies should further clarify and validate the relationship among social media involvement, social resources, social responsibility, and public health participation. Second, the survey was conducted online in China among a pool of media users. The respondents had an average age younger than the general media users in China, and a higher education level. The age and education distribution may result in findings biased toward the behaviors of younger, more educated media users, potentially deviating from the behavior across all age groups. Third, given China’s collective culture, the respondents may have aligned with social desirability, and the relationships among social support, social trust, social responsibility, and public health participation may differ from those in individualistic cultures.

While the findings provide insights into how social dynamics affect community-level pandemic control efforts, which could potentially be applied to other social contexts when society faces severe health threats, overall, the findings from a cross-sectional survey with sample bias and cultural features limit the generalizability of the study, and the results need to be treated with caution. Future research could be extended with probability samples and data collected through longitudinal and experimental studies in diverse cultural contexts to test the proposed model and the effects of social resource factors. Additionally, future studies are needed to refine the scales used to measure social trust, social support, and social responsibility given the changing media environment and social context.

Conclusion

As technology advances and the user base grows, social media not only plays an important role within the personal realm, but also serves the societal needs that concern public interests. Social media involvement affecting public health participation during the COVID-19 pandemic is a good example of how social media use is linked to a public cause and leads to results that will benefit all community members. By examining the interplay between social media involvement and social resource factors, this study provides deeper insights into the mechanism through which online interactions influence individuals’ attitudes and actions pertaining to public health in China. The perspectives of looking at social media use in connection with social and public causes and collective activities for health protection and disease prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic open a new realm of research into how social media use affects civic participation and how social resource building and management through social media use could produce positive results benefiting one’s community as well as the whole society.

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ahmad S, Zulkurnain N, Khairushalimi F (2016) Assessing the validity and reliability of a measurement model in Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). Br J Math Comput Sci 15(3):1–8. https://doi.org/10.9734/BJMCS/2016/25183

Allington D, Duffy B, Wessely S, Dhavan N, Rubin J (2021) Health-protective behaviour, social media usage and conspiracy belief during the COVID-19 public health emergency. Psychol Med 51(10):1763–1769. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172000224X

Arbuthnott KD (2009) Education for sustainable development beyond attitude change. Int J Sustain High Educ 10(2):152–163. https://doi.org/10.1108/14676370910945954

Aresi G, Procentese F, Gattino S, Tzankova I, Gatti F, Compare C, Guarino A (2022) Prosocial behaviours under collective quarantine conditions. A latent class analysis study during the 2020 COVID‐19 lockdown in Italy. J Community Appl Soc Psychol 32(3):490–506. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2571

Ariffin SR, Omar B, Isa A, Sharif S (2010) Validity and reliability multiple intelligent item using Rasch measurement model. Procedia-Soc Behav Sci 9:729–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.12.225

Ataguba OA, Ataguba JE (2020) Social determinants of health: the role of effective communication in the COVID-19 pandemic in developing countries. Glob Health Action 13(1):1788263. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2020.1788263

Aubrey JS, Rill L (2013) Investigating relations between Facebook use and social capital among college undergraduates. Commun Q 61(4):479–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2013.801869

Bartscher AK, Seitz S, Siegloch S, Slotwinski M, Wehrhöfer N (2021) Social capital and the spread of Covid-19: insights from European countries. J Health Econ 80:102531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2021.102531

Baumeister RF, Leary MR (1995) The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull 117(3):497–529

Besser TL (2009) Changes in small-town social capital and civic engagement. J Rural Stud 25(2):185–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2008.10.005

Blake J (1999) Overcoming the ‘value‐action gap’ in environmental policy: tensions between national policy and local experience. Local Environ 4(3):257–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839908725599

Borgonovi F, Andrieu E (2020) Bowling together by bowling alone: social capital and Covid-19. Soc Sci Med 265:113501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113501

Bourdieu P, Wacquant L (1992) An invitation to reflexive sociology. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Boyd DM, Ellison NB (2007) Social network sites: definition, history, and scholarship. J Comput-Mediat Commun 13(1):210–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x

Brehm J, Rahn W (1997) Individual-level evidence for the causes and consequences of social capital. Am J Political Sci 41(3):999–1023. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111684

Cheng WY, Cheung RY, Chung KKH (2021) Understanding adolescents’ perceived social responsibility: the role of family cohesion, interdependent self-construal, and social trust. J Adolesc 89(1):55–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.04.001

Cheng ZJ, Zhan Z, Xue M, Zheng P, Lyu J, Ma J, Zhang XD, Luo W, Huang H, Zhang Y, Wang H, Zhong N, Sun B (2021) Public health measures and the control of COVID-19 in China. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 64(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-021-08900-2

CNNIC (2024) The 54th statistical report on China’s Internet development, https://www.cnnic.net.cn/n4/2024/0829/c88-11065.html

Cohen S, Hoberman HM (1983) Positive events and social supports as buffers of life change stress. J Appl Soc Psychol 13(2):99–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1983.tb02325.x

Delhey J, Newton K (2003) Who trusts? The origins of social trust in seven societies. Eur Soc 5(2):93–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461669032000072256

Delhey J, Newton K (2005) Predicting cross-national levels of social trust: global pattern or nordic exceptionalism? Eur Sociol Rev 21(4):311–327. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jci022

DeSteno D, Bartlett MY, Baumann J, Williams LA, Dickens L (2010) Gratitude as moral sentiment: Emotion-guided cooperation in economic exchange. Emotion 10(2):289–293. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017883

Doolittle A, Faul AC (2013) Civic engagement scale: a validation study. Sage Open 3(3):2158244013495542. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013495542

Eisenberger NI (2013) An empirical review of the neural underpinnings of receiving and giving social support:Implications for health. Psychosom Med 75(6):545–556. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e31829de2e7

Elgar FJ, Stefaniak A, Wohl MJ (2020) The trouble with trust: time-series analysis of social capital, income inequality, and COVID-19 deaths in 84 countries. Soc Sci Med 263:113365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113365

Ellison NB, Steinfield C, Lampe C (2007) The benefits of Facebook “Friends:” social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. J Comput-Mediat Commun 12(4):1143–1168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x

Ferlander S (2007) The importance of different forms of social capital for health. Acta Sociol 50(2):115–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699307077654

Flanagan C (2003) Trust, identity, and civic hope. Appl Dev Sci 7(3):165–171. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532480XADS0703_7

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Fraser T, Page-Tan C, Aldrich DP (2022) Social capital’s impact on COVID-19 outcomes at local levels. Sci Rep 12:6566. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10275-z

Fu W, Wang C, Chai H, Xue R (2022) Examining the relationship of empathy, social support, and prosocial behavior of adolescents in China: a structural equation modeling approach. Hum Soc Sci Commun 9:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01373-4

Futri IN, Risfandy T, Ibrahim MH (2022) Quota sampling method in online household surveys. MethodsX 9:101877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2022.101877

Guan M, Han JY, Shah DV, Gustafson DH (2021) Exploring the role of social support in promoting patient participation in health care among women with breast cancer. Health Commun 36(13):1581–1589. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2020.1773704

Hajjar ST (2018) Statistical analysis: Internal-consistency reliability and construct validity. Int J Quant Qual Res Methods 6(1):27–38. https://eajournals.org/wp-content/uploads/Statistical-Analysis-Internal-Consistency-Reliability-and-Construct-Validity-1.pdf

Halbesleben JR, Neveu JP, Paustian-Underdahl SC, Westman M (2014) Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J Manag 40(5):1334–1364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527130

Han X, Wang J, Zhang M, Wang X (2020) Using social media to mine and analyze public opinion related to COVID-19 in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(8):2788. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17082788

Haythornthwaite C (2012) Social networks and online community. In A Joinson, KYA McKenna, T Postmes, U-D Reips (Eds), Oxford handbook of internet psychology (pp 121–138). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199561803.013.0009

He H, Harris L (2020) The impact of Covid-19 pandemic on corporate social responsibility and marketing philosophy. J Bus Res 116:176–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.030

Hobfoll SE (2001) The influence of culture, community, and the nested‐self in the stress process: advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl Psychol 50(3):337–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062

Houston JB, Hawthorne J, Perreault MF, Park EH, Goldstein Hode M, Halliwell MR, Griffith SA (2015) Social media and disasters: a functional framework for social media use in disaster planning, response, and research. Disasters 39(1):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12092

Imbulana Arachchi J, Managi S (2021) The role of social capital in COVID-19 deaths. BMC Public Health 21:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10475-8

Jackson AL, Wade JE (2005) Police perceptions of social capital and sense of responsibility: an explanation of proactive policing. Polic: Int J Police Strateg Manag 28(1):49–68. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510510580977

Johnson MF, Hannah C, Acton L, Popovici R, Karanth KK, Weinthal E (2014) Network environmentalism: citizen scientists as agents for environmental advocacy. Glob Environ Change 29:235–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.10.006

Jurgens M, Helsloot I (2018) The effect of social media on the dynamics of (self) resilience during disasters: a literature review. J Conting Crisis Manag 26(1):79–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12212

Kaplowitz MD, Hadlock TD, Levine R (2004) A comparison of web and mail survey response rates. Public Opin Q 68(1):94–101. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfh006

Kar B, Kar N, Panda MC (2023) Social trust and COVID-appropriate behavior: Learning from the pandemic. Asian J Soc Health Behav 6(3):93–104. https://doi.org/10.4103/shb.shb_183_22

Kelly DC (2009) In preparation for adulthood: exploring civic participation and social trust among young minorities. Youth Soc 40(4):526–540. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X08327584

Kim SH (2007) Media use, social capital, and civic participation in South Korea. J Mass Commun Q 84(3):477–494. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900708400305

Kim Y, Chen HT (2015) Discussion network heterogeneity matters: examining a moderated mediation model of social media use and civic engagement. Int J Commun 9:2344–2365. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/viewFile/3254/1432

Kwon KH, Shao C, Nah S (2021) Localized social media and civic life: motivations, trust, and civic participation in local community contexts. J Inf Technol Politics 18(1):55–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2020.1805086

Lachowicz-Tabaczek K, Kozłowska MA (2021) Being others-oriented during the pandemic: individual differences in the sense of responsibility for collective health as a robust predictor of compliance with the COVID-19 containing measures. Personal Individ Differ 183:111138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111138

Langford CPH, Bowsher J, Maloney JP, Lillis PP (1997) Social support: a conceptual analysis. J Adv Nurs 25(1):95–100. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025095.x

Lee HE, Cho J (2019) Social media use and well-being in people with physical disabilities: influence of SNS and online community uses on social support, depression, and psychological disposition. Health Commun 34(9):1043–1052. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2018.1455138

Lee J, Kim K, Park G, Cha N (2021) The role of online news and social media in preventive action in times of infodemic from a social capital perspective: the case of the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea. Telemat Inform 64:101691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2021.101691

Lim J-S, Al-Aali A, Heinrichs JH, Lim K-S (2013) Testing alternative models of individuals’ social media involvement and satisfaction. Comput Hum Behav 29(6):2816–2828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.022

Lin N, Ensel WM, Simeone RS, Kuo W (1979) Social support, stressful life events, and illness: a model and an empirical test. J Health Soc Behav 20(2):108–119. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136433

Liu D, Ainsworth SE, Baumeister RF (2016) A meta-analysis of social networking online and social capital. Rev Gen Psychol 20(4):369–391. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000091

Liu PL (2021) COVID-19 information on social media and preventive behaviors: managing the pandemic through personal responsibility. Soc Sci Med 277:113928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113928

Liu Y, Li X (2021) Pro-environmental behavior predicted by media exposure, SNS involvement, and cognitive and normative factors. Environ Commun 15(7):954–968. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2021.1922479

Liu Q, Wen S (2021) Does social capital contribute to prevention and control of the COVID-19 pandemic? Empirical evidence from China. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 64:102501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102501

Loader BD, Vromen A, Xenos MA (2014) The networked young citizen: social media, political participation and civic engagement. Inf Commun Soc 17(2):143–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.871571

Makridis CA, Wu C (2021) How social capital helps communities weather the COVID-19 pandemic. PloS One 16(1):e0258021. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258021

Martin JP, Stefl SK, Cain LW, Pfirman AL (2020) Understanding first-generation undergraduate engineering students’ entry and persistence through social capital theory. Int J STEM Educ 7(1):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-020-00237-0

Marziali ME, Hogg RS, Hu A, Card KG (2024) Social trust and COVID-19 mortality in the United States: lessons in planning for future pandemics using data from the general social survey. BMC Public Health 24(1):2323. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19805-y

Mat Dawi N, Namazi H, Hwang HJ, Ismail S, Maresova P, Krejcar O (2021) Attitude toward protective behavior engagement during COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia: the role of E-government and social media. Front Public Health 9:609716. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.609716

McElroy-Heltzel SE, Shannonhouse LR, Davis EB, Lemke AW, Mize MC, Aten J, Miskis C (2022) Resource loss and mental health during COVID‐19: psychosocial protective factors among US older adults and those with chronic disease. Int J Psychol 57(1):127–135. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12798

Mellor D, Freehills R (2018) The relationship between trust and giving: Insights from public trust survey data. Nonprofit Manag Leadersh 29(2):257–272

Meredith LS, Eisenman DP, Rhodes H, Ryan G, Long A (2007) Trust influences response to public health messages during a bioterrorist event. J Health Commun 12(3):217–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730701265978

Nielsen RK, Cloyes KG, Davis JL, Leander-Griffith M (2020) Exploring the associations of social responsibility, health beliefs, and COVID-19 prevention behaviors among U.S. adults. Nurs Outlook 68(6):854–862

Pang H (2022) Connecting mobile social media with psychosocial well-being: understanding relationship between WeChat involvement, network characteristics, online capital and life satisfaction. Soc Netw 68:256–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2021.08.006

Pavlova MK, Körner A, Silbereisen RK (2015) Perceived social support, perceived community functioning, and civic participation across the life span: evidence from the former East Germany. Res Hum Dev 12(1-2):100–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2015.1010351

Qiu SC, Jiang J, Liu X, Chen MH, Yuan X (2021) Can corporate social responsibility protect firm value during the COVID-19 pandemic? Int J Hosp Manag 93:102759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102759

Quandt T, Klapproth J, Frischlich L (2022) Dark social media participation and well-being. Curr Opin Psychol 45:101284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.11.004

Robin DP, Reidenbach RE (1987) Social responsibility, ethics, and marketing strategy: closing the gap between concept and application. J Mark 51(1):44–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298705100104

Rozzell B, Piercy CW, Carr CT, King S, Lane BL, Tornes M, Wright KB (2014) Notification pending: online social support from close and nonclose relational ties via Facebook. Comput Hum Behav 38:272–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.06.006

Sabatini F, Sarracino F (2019) Online social networks and trust. Soc Indic Res 142:229–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1887-2

Saud M, Mashud MI, Ida R (2020) Usage of social media during the pandemic: Seeking support and awareness about COVID‐19 through social media platforms. J Public Aff 20(4):e2417. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2417

Seiter CR, Brophy NS (2022) Social support and aggressive communication on social network sites during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Commun 37(10):1295–1304. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2021.1886399

Seo M, Sun S, Merolla AJ, Zhang S (2011) Willingness to help following the Sichuan earthquake. Commun Res 39(1):3–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365021038840

Shanka MS, Gebremariam Kotecho M (2021) Combining rationality with morality–integrating theory of planned behavior with norm activation theory to explain compliance with COVID-19 prevention guidelines. Psychol Health Med 28(2):305–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2021.1946571

Siegrist M, Luchsinger L, Bearth A (2021) The impact of trust and risk perception on the acceptance of measures to reduce COVID-19 cases. Risk Anal 41(5):787–800. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13675

Siegrist M, Bearth A (2021) Worldviews, trust, and risk perceptions shape public acceptance of COVID-19 public health measures. Proc Natl Acad Sci 118(24):e2100411118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2100411118

Sirgy MJ (2021) Effects of demographic factors on wellbeing. In MJ Sirgy (Ed), The psychology of quality of life: wellbeing and positive mental health (pp 129–154). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71888-6_6

Skoric MM, Zhu Q, Goh D, Pang N (2016) Social media and citizen engagement: a meta-analytic review. N Media Soc 18(9):1817–1839. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815616221

Tsao SF, Chen H, Tisseverasinghe T, Yang Y, Li L, Butt ZA (2021) What social media told us in the time of COVID-19: a scoping review. Lancet Digit Health 3(3):e175–e194. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30315-0

Uslaner EM (2023) The decline of social trust: how it affects us and what we can do about It. Oxford University Press

Utz S, Breuer J (2017) The relationship between use of social network sites, online social support, and well-Being. J Media Psychol 29(3):115–125. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000222

Valenzuela S, Park N, Kee KF (2009) Is there social capital in a social network site? Facebook use and college students’ life satisfaction, trust, and participation. J Comput-Mediat Commun 14(4):875–901. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01474.x

Vieira J, Castro SL, Souza AS (2023) Psychological barriers moderate the attitude-behavior gap for climate change. Plos one 18(7):e0287404. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287404

Von Dawans B, Fischbacher U, Kirschbaum C, Fehr E, Heinrichs M (2012) The social dimension of stress reactivity: acute stress increases prosocial behavior in humans. Psychol Sci 23(6):651–660. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611431576

Wang B, Yang X, Fu L, Hu Y, Luo D, Xiao X, Zou H (2022) Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in COVID-19 survivors 6 months after hospital discharge: an application of the conservation of resource theory. Front Psychiatry 12:773106. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.773106

Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, Xiong Y (2020) Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Jama 323(11):1061–1069. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.1585

Wang G, Zhang W, Zeng R (2019) WeChat use intensity and social support: the moderating effect of motivators for WeChat use. Comput Hum Behav 91:244–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.10.010

Wang T, Shen B, Springer CH, Hou J (2021) What prevents us from taking low-carbon actions? A comprehensive review of influencing factors affecting low-carbon behaviors. Energy Res Soc Sci 71:101844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101844

Warren AM, Sulaiman A, Jaafar NI (2014) Social media effects on fostering online civic engagement and building citizen trust and trust in institutions. Gov Inf Q 31(2):291–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2013.11.007

Wellman B, Haase AQ, Witte J, Hampton K (2001) Does the internet increase, decrease, or supplement social capital? Am Behav Sci 45(3):436–455. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027640121957286

Woelfert FS, Kunst JR (2020) How political and social trust can impact social distancing practices during COVID-19 in unexpected ways. Front Psychol, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.572966

Xin Y, Li D (2022) Impacts of psychological resources, social network support and community support on social participation of older adults in China: Variations by different health-risk groups. Health Soc Care Community 30(5):e2340–e2349. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13673

Xu S, Li W, Zhang W, Cho J (2021) The dynamics of social support and affective well-being before and during COVID: an experience sampling study. Comput Hum Behav 121:106776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106776

Xue S, Kaufman MR, Zhang X, Xia S, Niu C, Zhou R, Xu W (2022) Resilience and prosocial behavior among Chinese university students during COVID-19 mitigation: Testing mediation and moderation models of social support. Psychol Res Behav Manag 15:1531–1543. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S364356

Ye Y, Xu P, Zhang M (2017) Social media, public discourse and civic engagement in modern China. Telemat Inform 34(3):705–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2016.05.021

You S, Lee J, Lee Y (2022) Relationships between gratitude, social support, and prosocial and problem behaviors. Curr Psychol 41:2646–2653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00775-4

You Z, Wang M, He Z (2023) Residents’ WeChat Group use and pro-community behavior in the COVID-19 crisis: a distal mediating role of community trust and community attachment. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 16:833–849. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S407534

Zavestoski S, Shulman S, Schlosberg D (2006) Democracy and the environment on the internet: electronic citizen participation in regulatory rulemaking. Sci Technol Hum Values 31(4):383–408. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243906287543

Zeballos Rivas DR, Lopez Jaldin ML, Nina Canaviri B, Portugal Escalante LF, Alanes Fernández AM, Aguilar Ticona JP (2021) Social media exposure, risk perception, preventive behaviors and attitudes during the COVID-19 epidemic in La Paz, Bolivia: a cross-sectional study. PloS one 16(1):e0245859. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245859

Zhong Z-J (2014) Civic engagement among educated Chinese youth: the role of SNS (Social Networking Services), bonding and bridging social capital. Comput Educ 75:263–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.03.005

Zhu R, Hu X (2023) The public needs more: the informational and emotional support of public communication amidst the Covid-19 in China. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 84:103469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103469

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wanqi Gong and Xigen Li conceptualized the study. Xigen Li wrote Introduction and part of Literature Review. Wanqi Gong analyzed the data and wrote Method, Results and Discussion. Yusi Zhang collected the data, wrote part of Literature Review, and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee on Human Subjects Ethics Sub-Committee of Shanghai University (No. ECSHU 2020-049). The study was carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants regarding the nature of the study, confidentiality of their data, and their right to withdraw at any time.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions