Abstract

Ye “also/too/as well” is one of the most frequently used adverbs in Mandarin Chinese. Although the lexical meaning and syntactic properties of ye have been widely discussed, there are few analyses of ye expressions in interactional discourse, let alone analyses examining its interactional functions. Under the framework of interactional linguistics, this paper investigates the interactional functions of ye in second positions within natural spoken conversations. The findings show that ye indicating similarity between two states of affairs seems to be generalized in different interactional contexts with two interactional functions, i.e., rapport building and conflict mitigation. These functions are deployed by speakers to establish online alignment between interlocutors, expressing their affiliative stances and highlighting (inter)subjectivity, though practices of achieving a certain alignment vary in different environments. Hence, a continuum of similarity and the underlying evolution of language use is proposed to account for the diverse range of uses of ye expressions in face-to-face conversation. This paper not only reveals the interconnected relationship between linguistic forms and the construction and maintenance of social rapport but also sheds light on studying grammar entities with an interactional approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ye “also/too/as well” is one of the most frequently used adverbs in Mandarin Chinese. Previous studies mainly focus on the semantics and syntactic categories of ye, and generally believe that ye is a connective adverb which is used to conjoin at least two propositions P and Q, indicating similarity between two states of affairs (Eifring, 1995). Notably, there is a lack of research regarding ye expressions in interactional discourse. Consequently, how ye expressions are used by speakers in talk-in-interaction, and whether or not the use of ye to express similarity is attested in natural conversation, remain open questions. It has been proposed that ye can be taken as a lexical resource to express one’s aligned positioning, similar to the use of its counterparts me too/either in English (Du bois, 2007: 163; see also in Luo, 2013: 146).Footnote 1 Since there is no response or response element that is intrinsically affiliative or disaffiliative (Sorjonen, 2001), ye can only be used to display a speaker’s affiliation or stance (if any) in certain sequential positions. In view of this, this paper outlines an in-depth exploration of the use of ye in second positions in social interaction under the framework of interactional linguistics (see Couper-Kuhlen & Selting, 2018). The paper attempts to answer the following questions:

-

(1)

What social interactional achievement(s) do ye expressions help accomplish?

-

(2)

How do ye expressions contribute to realizing this/these social interactional achievement(s) in a discourse context?

To address these questions, we examine the two identified interactional functions of ye, (a) as a rapport-building device in an affiliative context, and (b) as a mitigation device in a disaffiliative context. In our examination, we show how the pragmatic continuum of ye and interactional motivations contribute to the two identified interactional functions. This paper deepens our understanding of the relationship between linguistic forms and the construction and maintenance of social rapport, showing that an interactive-analytic approach can shed new light on seemingly objective expressions in Chinese and beyond.

Brief review of previous ye studies

As a high frequency adverb, ye has received extensive treatment via diverse theoretical approaches. Given the vast literature involved, we can only provide a brief overview of some of the most representative accounts. Lü (1980: 595-597) summarizes the meaning of ye into four aspects: 1) indicating that two things are the same; 2) indicating that two consequences are the same; 3) strengthening the tone of a sentence with a preceding lian “even”; and 4) expressing a euphemistic tone. Based on these interpretations, the meanings and functions of ye have been studied by linguists from multiple perspectives. It has been argued that the core meaning of ye is to express similarity (e.g., Ma, 1982; Biq, 1994; Li, 1997), or more specifically to highlight similarity in differences (Shen, 1983) from which other meanings are derived. In contrast, other scholars have suggested that ye has multiple senses and thus should be interpreted in different ways, i.e., expressing juxtaposition, relevance, and modality (e.g., Zhang, 2001; Hole, 2004). Furthermore, the co-occurrence of ye as a focus sensitive particle with other constituents in a sentence has been discussed by researchers such as Shyu (1995) and Liu and Xu (1998). However, these studies mainly focus on the semantics of ye, and most of them use created examples at the sentence level which are not representative of the function and nature of ye in real spoken interaction.

Although some studies on ye have moved beyond the frameworks of formal syntax and semantics, a consensus regarding the pragmatic functions of ye has yet to be reached. For example, a number of studies on ye expressions have moved to explore its pragmatic functions from the perspective of modality, suggesting that the modal use of ye can be conceived as expressing mild tone (Ma, 1982), concessivity (Yang, 2020), or emphatic tone (Hole, 2004). He and Zhang (2016: 15) argue that the euphemistic use of ye from the traditional point of view is a modal trigger with interpersonal functions. It guides the hearer to infer the additional modal meaning by triggering the contextual assumption of the clause as shown in (1).

(1) | ni | ye | tai | bu | dongshi | le. (Cited from Ma, 1982) |

2SG | YE | too | NEG | tactful | PRT | |

‘You are too untactful!’ | ||||||

Ye in example (1) implies that not only are “you” untactful, but also that there are others like “you” who are untactful. This is achieved through the use of ye which also weakens the strong tone of criticism in the sentence (Ma, 1982). Furthermore, Deng (2017: 653) suggests that ye can be used in an interactional context, not to describe the event itself but to express the speaker’s attitude, emotion, and cognition. He further provides a unified interpretation for ye’s modal and propositional usage using the notion of scalar implicature. However, it has been argued that ye does not have a scalar meaning no matter what utterance or context it presents, while the so-called scalar use of ye requires both the specific contextual assumptions and the speaker’s subjective settings (Xue, 2023: 331). Although previous studies have noted the interpersonal meaning of ye and pointed out that such a logical connective has extended to an (inter)-subjective use (He & Zhang, 2016), the data they used are based on carefully processed dialogs in literary works, which are not conducive in portraying the communicative function of ye in everyday spoken conversation.

Similarly, Li (2012) examines the discourse functions of the expression ye shi “also be” from the speaker’s perspective, which is derived from the grammaticalization of [modal particle ye+copula shi], proposing that ye shi has three functions: explanation, identification, and complaint. Among these, Li (2012: 90)’s identification refers to situations where interlocutors may not hold the same or similar views at the beginning of a verbal exchange but come to understand and then accept the other’s views after the addressees provide clarifications. While Li (2012)’s notion of identification is similar to our identified function of online alignment, Li (2012) examines ye shi as a whole and does not focus on the actual interactional functions of ye.

To summarize, previous studies have carried out a relatively comprehensive description of the meaning of ye, laying the research foundation for this paper. However, existing research fails to reveal the role of ye in real spoken conversation. Although some studies partially touched upon the interpersonal meaning or euphemistic usage of ye in conversation, they only stay at the sentence level and have not conducted a longitudinal analysis of interactional functions of ye in sequences, nor have they examined the emergent mechanism(s) of those functions in an interactional context. This paper attempts to address these issues and fill the gaps under the framework of interactional linguistics.

Data collection and methodology

The data are drawn from the corpus of Mandarin Chinese conversations created by our research team. The corpus was transcribed from a total of about 97 h of audio and video materials, totaling ~1.77 million words. These materials were collected from themeless everyday conversations in private contexts, involving 2–3 participants in spontaneous, naturally occurring face-to-face interactions.Footnote 2 All the data were collected with informed consent of the participants. The transcription conventions are based on the GAT2 transcription system as detailed in Appendix A. Due to the high frequency of ye in the corpora, it was not necessary to examine each one. Hence, the first 200 instances of ye expressions were extracted for analysis (examples of repeated transcription and typos were removed), and they were re-organized as a sub-corpus of about 50,000 words. A quantitative and qualitative combined analysis was then carried out on these 200 instances of ye, focusing on ye’s interactional functions. During the process, the instances were sequentially numbered from 1 to 200 and were then manually coded by the researcher to mark for the functions they displayed. Finally, the instances of ye were categorized and quantified based on their different functions. As introduced above, Interactional Linguistics (IL) is the main framework adopted in this study to address the research questions as IL lays particular stress on how language structure and interaction shape each other (Selting & Couper-Kuhlen, 2001).

Ye for establishing online alignment

Our examination of the data shows that the interactional achievement of the speaker’s response with ye expressions in the interactional context is not merely to highlight the similarity or affinity among things, states, or evaluations, but to establish or seek to establish “online alignment” (Morita, 2005: 214)Footnote 3 among co-participants. That is, the interactional goal is to temporarily form a common stance or positioning in talk-in-interaction, displaying alignment with another speaker, and then to build and maintain a harmonious social relation with the addressee through communicative activities. As defined by Du Bois (2007: 163), “stance is a public act by a social actor, achieved dialogically through overt communicative means, of simultaneously evaluating objects, positioning subjects (self and others), and aligning with other subjects, with respect to any salient dimension of the sociocultural field”. Keisanen (2007: 254) further points out that all verbal means and paralinguistic features of language, as well as related linguistic structures, can be used for stancetaking. In Chinese conversation-analytic and interactional linguistic studies, ye is recognized as a linguistic element which can be deployed to express one’s stance that is aligned with the addressee not only in the institutional conversation context but also in ordinary conversations (e.g., Luo, 2013). However, when ye is deployed in the process of establishing online alignment, there are various ways in which such an achievement is accomplished. Consequently, different interactional functions are attributed to ye accordingly: a) when expressing agreement, ye can serve as a rapport-building device to create solidarity among participants; b) when expressing disagreement, ye is taken as a mitigation device to alleviate (apparently) conflicting stances. In the following two sections, we elaborate on how ye-formulated similarities are deployed to show affiliation, establishing stance alignment and creating solidarity among participants, and explore how such a similarity indicated by ye is used to mitigate dispreferred responses that are confronted with stance conflicts, maintaining social relations until the online alignment is re-built.

Ye as a rapport-building device

Ye-formulated similarities are frequently found in affiliative environments, accounting for 81.8% (90/110) of the surveyed data. In this case, ye is employed by speakers in response to a statement, evaluation, or assertion of the prior speaker to convey that they have common ground with co-participants. This interactional strategy, either explicitly expresses or implies that the speaker’s stance aligns with that of the other party and is the prominent path of establishing online alignment. In what follows, we will examine three cases to advance this argument: (1) ye for shared characteristics, (2) ye for listing, and (3) ye for supporting a claim.

Ye for highlighting shared characteristics to evoke common ground

As is well known, Chinese culture is typically characterized as collectivistic, while collectivism does not just exist within people’s minds, but rather manifests itself in talk in interaction (Wu & Tao, 2018). Seeking commonality rather than individuality is less likely to cause disagreement, and it is easier to reach a common position and establish an alignment. In response to a prior speaker’s utterance or comments, speakers can use ye expressions to offer affiliative responses in real-time, indicating that they share states, thoughts, or feelings with their recipients. By invoking a shared past and establishing a common ground for further talk, ye can help build interpersonal connections among interlocutors and result in positive reactions from co-participants. Excerpt (2) is a case in point.

Excerpt (2) “So sleepy” | |||||||

01 | Y: a(-) | chi | bao | le | jiu | hen | kun. |

PRT | eat | full | PFV | will | very | sleepy | |

‘Ah, I feel very sleepy on a full stomach.’ | |||||||

02→ | M: wo | ye | hao | kun. | |||

1SG | YE | so | sleepy | ||||

‘I am so sleepy too.’ | |||||||

03 | Y: a | duibuqi! | |||||

PRT | sorry | ||||||

‘Sorry!’ | |||||||

04 | M: [haha | ||||||

[((laughter)) | |||||||

05→ | L: [wo | ye | hao | kun. | |||

1SG | YE | pretty | sleepy | ||||

‘[I am so sleepy too.’ | |||||||

In excerpt (2), Y initiates an exclamation to her partners about her drowsiness after the meal in line 1, M then responds to this assertion in the form of a ye expression (line 2). On the one hand, the expression communicates that she is sleepy as well, and on the other, it establishes that her situation aligns with Y’s description. This allows M to put herself in a subordinate position. Y apologizes immediately in line 3, as she is worried that M’s judgment is negatively affected by her previous exclamation. But M does not take it seriously and laughs away Y’s embarrassment in line 4. At the same time, another participant L, includes herself in the group that has a shared characteristic of drowsiness caused by satiety through her ye expression in line 5, confirming that Y and M’s prior statements are not a particular case. Such a supportive move demonstrates the speaker’s in-group identity, sharing a common understanding or reinforcing a common stance (Wu & Tao, 2018). In this way, L is connected to Y and M through the overtly common feature of post-meal drowsiness, establishing solidarity among co-participants.

From excerpt (2), we can clearly see how ye is deployed to establish online alignment between two or more participants. Through ye expressions, speakers convey that they have the same characteristics or status as recipients, increasing the relevance of both the form and meaning of utterances (Zhang & Li, 2023). Hence, a common ground among participants is established, and it can be taken to implement further actions.

Notably, interrupting the turn or other party’s speech is initially an impolite turn competition behavior, but sometimes speakers’ interruptions are out of a rush to express their own opinions that are in line with the other party’s point of view, such as L in excerpt (2). It is ye that often occurs in this type of overlap based on cooperation, and its function to establish online alignment may temporarily eliminate the negative impact of the induced interruption.

In spoken conversation, speakers may often selectively repeat some words or elements of those who have spoken before to build their own utterances. That is, an utterance is derived from either the partial or the whole structure of the previous discourse (Du Bois, 2007: 140), and the analogy implied by the structural parallelism can induce resonances in multiple functional domains, including information transfer, cognitive processing, affective alignment, and interpersonal cooperation (Du Bois, 2014). In excerpt (2), L’s affiliative response in line 5 is exactly the same as the response of M to Y in line 2, shown as a repetition (Schegloff, 1997: 525) or an echo utterance in which speakers repeat all or part of a message of another speaker in order to realize particular communicative functions (Quirk et al., 1985: 835–838). L’s repetitive assertion here is clearly not only for the previous speaker Y, but also an endorsement of M. As echo utterances function to hold the floor, express one’s involvement, provide backstage response, express understanding, appreciate and support one’s words, “register receipt” and “target a next action” (Tannen, 2007: 15–17), the co-occurrence of ye and echo utterance expressing agreement and support can be attributed to the interactional function of building rapport. It seems that ye plays an important role in the construction of this type of echo utterance, not only operating on the coherence between the current utterance and the previous one but also linking the positioning of the speaker with a prior speaker, projecting a common ground or in-group identity among co-participants.

In the data examined for this paper, 37 out of 40 responses that highlight shared features are in the form of [first person pronoun + ye], which express the same thoughts or attitudes among participants. Generally speaking, the first-person pronoun is considered as an essential sign of subjective expression in language (Scheibman, 2002). This is based on the observation that the first-person pronoun is a marker of a deictic center from which one’s discourse is organized (Iwasaki, 1993). However, the first-person pronoun is also taken as a sign that objectifies the speaking self (Langacker, 2002). A speaker may put themselves on “the stage” through the use of the first-person pronoun to observe themselves objectively. We need to take into account both perspectives, where the first-person pronoun can be construed either objectively or subjectively. This explains why [I + ye] can be understood either as speakers informing addressees of their information, or as an interpretation of the stance taken by speakers and their affiliations with the previous speaker.Footnote 4

Therefore, in this type of interactional environment showing participants’ common characteristics, ye embodies both objective meaning and subjective use (cf. Lyons, 1981).Footnote 5Ye expressions are deployed not only to convey propositional information related to speakers’ own cognitive states, feelings, or attitudes but also out of interactional needs. The production of such an utterance at a given time is a reflection of speakers’ subjective intentions, revealing their stance towards a prior speaker’s turn, which has an effect on the development of the current topic and the subsequent course of conversation. As is suggested, stancetaking is not simply a static presentation of the speaker’s personal view, but a dynamic, emerging, and cooperative product of language in social interaction. Interactors both align with the ongoing course of action and associate with each other (Stivers, 2008) in response to local contingencies in interaction. Hence, stancetaking is a public action that is shaped by joint inputs from all participants, and as a result, stance is considered to be situated, inter-subjective, and collaborative (Kärkkäinen, 2006; Iwasaki, 2015).

Ye to list in-group items for promoting solidarity

In Chinese spoken conversation, Tao (2019: 65) defines list construction as the production of a set of formally similar and functionally related items in adjacent conversation units (either in the same speaker turn or in adjacent turns) that fall under a broad discourse theme. By listing comparable items, speakers indicate that their positioning is consistent with that of the previous speaker. In the context of lists, the inherent lexical meaning of ye allows for the creation of adjoining lists, and its logical properties illustrate that the use of ye always projects the existence of a conjunct that shares some similar features (Yang, 2000). As a result, ye expressions allow speakers to add items that are considered to be in the same group but not yet present in the list, inducing a parallel relationship between items already listed and the new additions. In this way, speakers show their agreement with what has been communicated and establish online alignment in talk-in-interaction. This listing process is demonstrated in excerpt (3) below.

Excerpt (3) “Bitter is ok as well.” | |||||||||||||||

01 | M: jiemei | ni(.) | ni | shi(.) | jiu shi(.) | suan(.) | suan(.) | suan | tian | ku | la | dou(.) | dou | keyi | ma? |

sister | 2SG | 2SG | COP | just COP | sour | sour | sour | sweet | bitter | spicy | all | all | ok | PRT | |

‘You, are you, that is, sour, sour, sour sweet bitter and spicy, all, are they ok?’ | |||||||||||||||

02 | [en | a(.) | suan | tian | la | dou | xing@ | ||||||||

umm | PRT | sour | sweet | spicy | all | ok | |||||||||

‘[Umm-huh, sour, sweet and spicy are ok?’ | |||||||||||||||

03 | Y: [en | dui | |||||||||||||

umm | right | ||||||||||||||

‘[umm right.’ | |||||||||||||||

04 | hahaha | ||||||||||||||

((laughter)) | |||||||||||||||

05 | L: [meiyou | ku | |||||||||||||

not | bitter | ||||||||||||||

‘[Not bitter.’ | |||||||||||||||

06→ | Y: [ha | ku | ye | ||||||||||||

ha | bitter | YE | ok | ||||||||||||

‘[((laugh)) Bitter is ok too.’ | |||||||||||||||

In excerpt (3), M initially asks Y if she can accept all four flavors, i.e., sour, sweet, bitter, and spicy (line 1), but then M removes “bitter” deliberately in her revised question (line 2), since she may suddenly realize that bitter is less acceptable than the other three flavors. Y’s affirmative response in line 3 overlaps with M’s turn and is completed before M, thereby she confirms that sour, sweet, spicy, and bitter are good, but L jokes that meiyou ku “there is no bitterness” (line 5) in terms of this confirmation, so Y further supplies that ku ye xing “bitter is ok as well” to close the list (line 6).

As pointed out by Couper-Kuhlen and Selting (2018: online chapter F), items in a list share, or present as sharing, some sort of sameness. Here “bitter”, as an item in the same group with similar properties as “sour, sweet, and spicy”, is activated by the speaker and introduced by the ye expression indicating that the new item “bitter” belongs to the same category as “sour, sweet, and spicy”. The use of ye not only increases the list of items, but also backtracks to confirm that the presupposed alternatives in the background, such as sour, sweet, and spicy, are of the same category as bitter and are thus all equally acceptable. Most lists are in fact constructed to consist of triple singles (Jefferson, 1990: 64). That is, if a third item is missing, speakers will be observed to display trouble, hold the turn, and search for it or generalized list completers are often provided by a recipient (Jefferson, 1990: 65, 67). However, lists with ye expressions are not necessarily the same. Instead, ye expression lists are open lists which are often co-constructed while the speaker is expressing agreement with the previous speaker by listing an item that shares common features with other listed items. It seems that expressing agreement or affiliation by listing in-group items is similar to the way of highlighting shared characteristics. However, the first approach is more explicit and direct, as there is no need for analogical reasoning to affirm what is previously communicated.

Ye to support a previous speaker’s views or actions

Alignment moves such as assessments, collaborative contributions, and collaborative completions index shared understanding, the ability to adopt the other’s point of view, and the ability to speak in the other’s voice (Dings, 2014). In addition to the two means discussed above, speakers in the interactional context can also coordinate and cooperate with each other by providing further supportive evidence in their own turns to express their positive attitudes towards prior discourse. van Eemeren (2010) points out that argumentative discourse is a specific communicative interaction between interlocutors to prove their own position or refute the other party’s. When speakers align with each other, the explanatory statement can naturally be reduced to a defense of the recipient’s stance. By adding further explanation, the supporting rationale introduced in the same argumentative direction by the ye expression can establish a connection with the previous speaker’s view or action. The rationale is not presupposed but arises gradually as the sequence progresses. This non-presuppositional property and the sequence advancing process are compatible with the additive meaning of ye, giving rise to the use of ye as a resource for supporting and maintaining one’s stance. Consider the following excerpt (4) to illustrate this. Y, L, and M are ordering dishes in a restaurant and they have ordered Mapo Tofu and Black Pepper Beef, then L notices “refreshing okra”.

Excerpt (4) “Order dishes” | |||||||

01 | Y: en | [xiang | chi(.) | enheng. | |||

uhm | want | eat | PRT | ||||

‘Uhm [(I) want to eat, umm-hmm.’ | |||||||

02 | L: | [o | |||||

PRT | |||||||

‘[Oh.’ | |||||||

03 | M: na | jiu | jia | yi | ge | bei. | |

then | just | add | one | CL | PRT | ||

‘Add one more.’ | |||||||

04 | L: [jia. | ||||||

add | |||||||

‘[Add.’ | |||||||

05 | M: [jia | yi. | |||||

add | one | ||||||

‘[Add one.’ | |||||||

06→ | L: fanzheng | ye | bijiao | pianyi(.) | [shiwu kuai qian, | ||

anyway | YE | relatively | cheap | fifteen CL money | |||

‘It is cheap anyway, [fifteen yuan.’ | |||||||

07 | Y: | [hao ba | |||||

ok PRT | |||||||

‘[All right.’ | |||||||

08→ | L: guji | ye | hen | shao. | |||

probably | YE | very | few | ||||

‘Probably very few.’ | |||||||

09 | M: en(.) | guji | hen | shao. | |||

umm | estimate | very | few | ||||

‘Umm, probably very few.’ | |||||||

In excerpt (4), Y indicates that she wants to add the dish “refreshing okra” in line 1. At first, L does not explicitly agree with this desire but M proposes to add the dish in response to Y’s utterance (line 3). Subsequently, L expresses her agreement with M’s proposal by repeating the verb jia “add” (line 4), and after M’s confirmation of the addition (line 5) L uses the ye expression to give further comments on the ordered food. That is, the dishes are relatively cheap (line 6) and their portion is small (line 8). Although these assessments are nearly interrupted by Y’s affirmation (line 7), they are recognized by Y and M in the following sequences. On the one hand, L’s additional description of the characteristics of dishes provides more positive evidence to support Y’s desire to add the dish and M’s decision to support this so as to rationalize their propositions; on the other hand, it implies that L’s stance aligns with Y and M’s. In such cases, the speaker introduces a positive event related to the current topic into the conversation through the use of the ye expression, serving as a supportive justification for the addressee’s view to eliminate contingent refutation and maintain the addressee’s stance and promote solidarity through which online alignment is established.

In excerpts (2) (3) and (4) above, speakers convey their agreement with the previous utterance through different practices, such as highlighting shared characteristics (excerpt 2), listing in-group items (excerpt 3), and supporting prior talk with evidence (excerpt 4), which show their high involvement in the current topic. These various practices illustrate ye’s interactional function as a rapport-building device to establish online alignment. In the following section, we examine ye expressions used to convey a speaker’s opposing stance and analyze the role and interactional functions of ye as a conflict mitigation device.

Ye as a conflict mitigation device

Just as alignment in Du Bois’s (2007) stance triangle can be divided into two sides, i.e., “align” and “disalign”, the notion of affiliation also has a counterpart, i.e., disaffiliation. In the excerpts above (2–4), the use of ye can be categorized as affiliative and is harmonious in nature from the speakers’ stance perspectives. In addition to affiliation, our data also show the use of ye expressions for similarity in conflicting talk or disagreement sequences, i.e., contexts of disalignment. Research has shown that the speakers always manage to use practices that serve to maximize opportunities for affiliative actions and minimize opportunities for disaffiliative ones (Heritage, 1984). When the asymmetric dispreferred action arises in response to an initial action, speakers usually try to soften the disagreement in order to decrease negative effects that do not support the accomplishment of the activity and threaten social solidarity (Schegloff, 2007). Given the relevance of agreement and disagreement, the production of weak agreements may be disagreement implicative (Davidson, 1984: 112). Accordingly, weak agreements are usually deployed to implement a disapproval-based action to reduce the likelihood of a dispreferred response, such as disagreement or refutation. Following this line, we find that the speaker often uses a ye expression to alleviate implicit conflicting stances and dissolve an apparent disagreement. This usage of ye can be divided into two types: (1) controlling explicit opposing views, and (2) alleviating implicit disagreements. In the following two subsections, we further explore how ye expressions invoking similarity are used to mitigate (apparent) conflicts among participants.

Ye for controlling explicit opposing views to maintain harmonious relations

Controlling an opposing view refers to the practice of the speaker using the lexical resource ye to mitigate an explicit conflict caused by the stance conflicts between interlocutors with the intention of weakening the degree of disalignment and/or re-establishing online alignment. As has been discussed in the extensive conversation-analytic literature, dispreferred responses may be expressed in attenuated or mitigated form (Schegloff, 1988; Kendrick & Torreira, 2015). Ye expressions can be deployed in a second position as opposed to the first pair part based on the previous speaker’s statement or attitude.

In excerpt (5), W tells Y that she will go home immediately and asks Y to recommend a low-brain-power film for her to watch during dinner.

Excerpt (5) “Marvel movies” | |||||||

01 | Y: manwei de | ni | kan | wan | le | ma? | |

Marvel ASSOC | 2SG | watch | finished | PFV | PRT | ||

‘Are you done with the Marvel series?’ | |||||||

02 | W: kan | wan | le | a! | |||

watch | finished | PFV | PRT | ||||

‘Done!’ | |||||||

03 | Y: manwei | de | dou bu yong dongnao | ||||

Marvel | ASSOC | all not need think | |||||

‘Marvel series movies are low brain power.’ | |||||||

04 | manwei de | yao dongnao | ma? | ||||

Marvel ASSOC | need think | PRT | |||||

‘Does the Marvel series require you to think?’ | |||||||

05 | [haha | ||||||

[((laughter)) | |||||||

06 | W: [ta(.) | bu | shi | xiju | a. | ||

3SG | not | COP | comedy | PRT | |||

‘[They are not a comedy.’ | |||||||

07→ | Y: ye | suan | xiju | ba | |||

YE | be-considered | comedy | PRT | ||||

‘They might be considered as a comedy.’ | |||||||

08 | W: manwei | dianying | you | bu | xiafan | ||

Marvel | film | and | not | interesting | |||

‘Marvel series movies are not interesting.’ | |||||||

Y asserts that Marvel movies do not require a lot of brain power from viewers (line 3), which meets W’s requirement. Thus, Y recommends that W watch Marvel movies during dinner. However, W produces a negative judgment against the Marvel series (line 6). The short pause after the reference indicates that W is searching for how to reasonably reject Y’s recommendation. In the following line 7, Y does not agree with W’s assertion in the previous turn, and instead, she gives her own opinion that the Marvel series movies can be regarded as comedy films. Xue (2023) suggests that the ye-utterance in an acceptance context points to the status of being no higher or worse than the threshold expectation assumed, hence even though what is uttered could be accepted, the validity of that utterance is weakened. In other words, the pragmatic scale of the item modified by ye is lower than that of a general situation. This allows for the realization of the subjectively small quantification of the item modified by ye, which is in this case Marvel movies. In line with this view, due to the presence of ye, Y’s utterance triggers an implicit analogy alternative treated as the comparing item, which occupies the point of threshold expectation, and is derived from pragmatic accommodation. Although an implicitly referenced alternative is unclear, the discourse suggests this to be a film with prototypical comedy features and which is located at a higher point on the pragmatic scale of being classified as a comedy. Compared to this triggered alternative, although Marvel series movies have some of the same characteristics found in comedy films, they are not typical comedies. That is Marvel series movies are positioned at a lower point on the scale and are barely regarded as comedy films, let alone prototypical comedies. Thus, the reliability of Y’s utterance is downgraded, making the conflict between Y’s and W’s stancetaking less obvious. The downgrading of Y’s utterance reliability can also be concluded from the collocation of ye and ba “PRT” in the sentence, as a sentence containing sentence-final particle ba expressing assertion shows the speaker’s compromise by weakening the credibility of the utterance and transferring the decision power to the other party, thereby establishing online alignment with the recipient (Gao, 2016).

Hence, when the speaker produces an utterance that is obviously contrary to the previous speaker’s stance, the presence of ye induces contextual assumptions through which the opposing view sounds mild. The use of ye in this context functions to maintain the initially friendly interaction between the speaker and the recipient while making the weakened view easier for the recipient to accept, thus contributing to re-establishing online alignment among co-participants.

Ye for alleviating implicit disagreements to weaken the disalignment

As Schegloff (1988) observes, dispreferred actions can be produced with preferred turn formats and preferred actions can be produced with dispreferred turn formats (cf., Heritage, 1984: 267–268; Lerner, 1996: 305). In Chinese spoken interaction, alleviating implicit disagreements is an exact case in point, which is a practice that the speaker employs when expressing a view or action contrary to the recipient’s. The act of alleviating implicit disagreements is shaped by offering a preferred response accompanied by a downgraded operation on wording. Unlike controlling explicit opposing views, in some cases, speakers use the ye expression to produce an opinion consistent with the previous speaker’s stance while deploying relevant lexical resources to downgrade the utterance. The result is a kind of weak agreement or concessive affiliation. By doing this, speakers not only highlight their epistemic independent status towards the object under discussion but also pave the way for implementing a dispreferred action or changing the topic, projecting the forthcoming disagreement in the sequence. For example, in (6), Y describes to W the writing style of “grand narrative” movies that she likes (omitted due to limited space), then W recommends Y watch the film The World is a World of the Past.

Excerpt (6) “Grand narrative” | |||||||||||||

01 | W: na | wo | tuijian | ni | kan renjian zhengdao shi cangsang | ||||||||

then | 1SG | recommend | 2SG | see world right-way COP change | |||||||||

‘I recommend you watch The World is a World of the Past,’ | |||||||||||||

02 | juedui | you | ni | xiang | yao | de | dongxi | ||||||

absolutely | have | 2SG | want | require | CSC | content | |||||||

‘which definitely has what you want.’ | |||||||||||||

((40 lines omitted where W introduces the main content of the film in detail)) | |||||||||||||

43 | W: zhe jiu | shi | ni | yao | de | da | xushi | ||||||

this just | COP | 2SG | demand | CSC | grand | narrative | |||||||

‘This is the grand narrative you want,’ | |||||||||||||

44 | [juedui | shi | ni | yao | de | xu | da | xushi(.) | wo gen ni | jiang | |||

absolutely | COP | 2SG | demand | C | narrative | grand | narrative | 1SG to 2SG | speak | ||||

‘[Definitely the grand narrative you want, I tell you.’ | |||||||||||||

45 | Y: [((laughter)) | ||||||||||||

46→ | qishi | ting(.) | yinggai | ye | ting | hao | de | zhe | zhong | da | xushi | ||

actually | quite | should | YE | quite | good | C | this | type | grand | narrative | |||

‘Actually quite, this type of grand narrative should also be very good,’ | |||||||||||||

47 | ai buguo | youde | shihou | kan | da | xushi | kan jiu | le | |||||

hey but | some | moment | see | grand | narrative | see long | CRS | ||||||

‘But sometimes if I see grand narrative too much,’ | |||||||||||||

48 | wo | ye | xihuan | kan | yixie:(.) | bu yong dongnao | de | pianzi | |||||

1SG | YE | like | see | some | not need use-one’s-brain | ATTR | film | ||||||

‘I also like seeing some: films that are low-brain-power.’ | |||||||||||||

In this excerpt, Y first agrees with W’s previous description of the film The World is a World of the Past with grand narrative features (line 46). However, compared to W’s comments of the film in line 44, Y’s assessment is relatively mild. She uses an inversion sentence containing ye with model particle yinggai “should” embedded to downgrade W’s utterance that is modified by juedui “absolutely”. We argue that Y’s purpose in doing this is to make a preparation for the subsequent reverse, as Y intends to produce a contrasting statement in the following discourse. At the initial position of line 47, Y uses the topic transition signal ai “ah” (see Yu, 2022),Footnote 6 which has the function of implying topic change (Li, 2019), followed by the weak adversative buguo “however”. By saying that she not only likes “grand narrative” films but also likes low-brain-power films, a new topic is introduced and the remaining discourse is focused on this new topic.

We can see that when ye is deployed in such an interactional environment, the validity of the utterance it involves seems to be downgraded as the item (i.e., the recommended film) modified by ye is located at a relatively lower point on the pragmatic scale of the likelihood of being good. By using ye, the speaker’s agreement is downgraded, conveying their implicit disagreement, and based on this the disalignment between the current confirmation and the upcoming contrasting statement is weakened. This interactional strategy of transferring from weak agreement to disagreement can mitigate the negative impact of face-threatening acts or affiliation destruction resulting from stance conflicts between two participants.

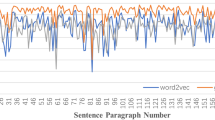

The distribution of ye in establishing online alignment

In the data, there are various usages of ye to (re-)establish online alignment. However, as shown in our data, those practices have significant differences in their frequency as shown in Table 1.

Of the 200 ye instances, 110 demonstrate online alignment construction, all of which are employed as the second response in an interaction. Among them, 90 instances of ye can be treated as a means of building rapport among co-participants, while the other 20 instances are deployed as a mitigation device for alleviating (potential) conflicts between the interlocutors. The former function (81.8%) is 4.5 times higher than the latter one (18.2%). In detail, in the cases where ye is used as a rapport-building device, the practice of highlighting shared characteristics is the most frequent (40/110), accounting for 36% of the total, which is not much different from the sum of the practices of listing in-group items (21.8%) and supporting a previous speaker’s views or actions (23%). In contrast, in the cases where ye is used as a mitigation device, the practice of controlling explicit opposing views (9.1%) is equal to/on par with the practice of alleviating implicit disagreements (9.1%), but they are all less frequent than the rapport-building cases.

We propose several reasons for these distribution differences. First, interactional efficiency. Since speakers can directly show their in-group identity and explicitly convey their alignment with the previous speaker’s stance, it is more direct and efficient to reveal shared characteristics in the course of establishing online alignment, which is in line with the economic principle of language use. Furthermore, listing in-group items and supporting a previous speaker’s views or actions may be subject to different views from the recipient regarding the additional listed item and supplementary justifications, and in these two cases, the positive correlation between the added information and the previous information needs to be identified by the recipient through analogical reasoning. That is, the recipient is required to put more effort into processing the position expressed by the ye-expression. When things are equal, less processing effort is exerted and an utterance becomes more relevant (Sperber & Wilson, 1995). As a result, the two practices of listing in-group items and supporting a previous speaker’s views or actions are more indirect than highlighting shared characteristics for online alignment construction. Second, the derivation of basic practice. As we have discussed, the practices of listing in-group items and supplying positive evidence are like “twins”, they are employed to convey that the speaker’s stance aligns with the interlocutor’s and both are carried out under the condition that the participants have a common ground. Therefore, it is essential to evoke a common ground on which the speaker implicitly demonstrates affiliation with the recipient by listing an in-group item or providing supportive evidence for the recipient’s view. Third, the asymmetry of responses. There is no doubt that agreement, appreciation, and confirmation of a previous utterance are preferred responses. By contrast, disagreement, resistance, and refutation of the recipient’s turn are dispreferred. Participants are more likely to give a preferred response to maintain a friendly relationship and promote the conversation. This essentially explains why ye expressions are more often deployed to build rapport in interaction rather than to mitigate conflict.

It is worth noting that although ye has the interactional function of building online alignment, this does not mean that ye is an agreement marker or can casually induce consensus among co-participants. In the data, 90 instances of ye expressions do not have the interactional function of establishing online alignment. This indicates that the interactional meaning of ye pertains to the specific sequence position. As proposed in positionally sensitive grammar (Schegloff, 1996: 108), the same linguistic entities in different sequences may exhibit various interactional functions. In other words, ye occurs in different sequences (both types and positions) that are interactively relevant to the implementation of different social actions and may perform different, or even diametrically opposite, interactional tasks.

Ye as a pragmatic device indicating similarity and for establishing online alignment

Given the seemingly diverse range of functions, one may ask if there is a unified account for the use of ye expressions in conversational interaction. We believe that such an account is viable. Inspired by the pragmatic continuum of Plural NP + dou “all” expressions in conversation proposed by Wu and Tao (2018), we attempt to establish a continuum of the generalized similarity indicated by ye based on the pragmatic continuum of rapport to address how ye expressions contribute to establishing online alignment and achieving a unified interpretation for different interactional functions of ye.

As a pragmatic notion, rapport concerns harmonious social relations and needs to be actively maintained and managed in social interaction (Spencer-Oatey, 2000). What is reflected by the patterns of ye used in the second position in the data can be understood as a continuum of harmonious social relations. In Fig. 1, which represents the pragmatic continuum, affiliative responses are positioned on the left. The farther left a response is positioned, the more harmonious relation it builds. Likewise, disaffiliate responses are positioned to the right of the continuum. The farther right a response is positioned, the less harmonious relation it builds.

Since the core meaning of ye is to indicate the (arbitrary) addition of similar items, the relation between what is introduced in the ye expression and what has been previously uttered becomes analogous as ye is used to connect these two parts. Thus, by employing ye expressions speakers not only illustrate that they belong to the same group as recipients by making a homogeneous comparison between themselves and recipients, but also backtrack to, and confirm, the aforementioned items by listing and affirming a new in-group item (e.g., excerpts (2)–(4)). Moreover, since the semantic properties of ye can retroactively project a proposition or state of affairs with similar characteristics as the current proposition (Zhang, 2010), when speakers produce an utterance containing ye they naturally go back to the previous discourse for pairing. This connection back to previous discourse through the ye expression involves speakers relating current utterances to preceding ones, mapping the preceding proposition (i.e., the left conjunct of ye, P) by adding a new proposition that indicates a similarity or an explanatory relation between the two clauses. Hence, by using ye expressions speakers show their understanding and identification of views or actions involved in the previous speakers’ utterances by providing more supporting explanations or justifications, i.e., supplementary arguments which align with those in the preceding discourse.

However, as shown in excerpts (5) and (6), when ye is deployed as a mitigation device to alleviate conflicts in a specific context, it is often manifested as the speaker’s subjective judgment of similarity. That is, in some instances in the data, similarity is vague, hypothetical, or unverifiable—all traits of subjective evaluations. Such a subjective similarity is realized when the item modified by ye is assumed to be on the same pragmatic scale as the reference object or general situation according to the speaker’s assumption. Moreover, in actual interaction, analogies are always considered to be rather vague and subjective, relying on the speaker’s personal experience and cognition, and whether the so-called similarity can be verified is not a concern to the speaker. Furthermore, as shown in excerpts (5) and (6), ye can be used by the speaker to express disagreement with the previous utterance. When ye occurs in a context of disaffiliation, it appears to conflict with the interactional achievement of establishing online alignment. While this is, in fact, a merely provisional disalignment, the speaker’s ultimate goal is to re-establish online alignment by mitigating divergence in the ongoing interaction. This process of re-establishing alignment is schematized as the big blue arrow in Fig. 1. The mitigation function of ye reduces the effectiveness and credibility of the evaluation which it modifies, assisting the recipient to adjust or re-accept the new perspective. Therefore, we argue that ye is a pragmatic device whose specific interactional meaning at any point in interaction can only be revealed by its interactional context and contingent talk (Morita, 2015).

From the different practices of ye for establishing online alignment discussed above, it can be seen that ye has evolved from indicating similarity between propositions or states of affairs to triggering paralleled item(s) in the background, then to connecting two related events that are similar in argument orientation, and finally has extended to implying similarity between the evaluated item and the hypothetical reference or threshold expectation. We call these four cases direct analogy, backtracking analogy, argumentative direction analogy, and hypothetical analogy. Hence, the property of ye expressing similarity undergoes generalization, expanding from indicating similarity in logical semantics to indicating pragmatic similarity. Consequently, the similarity indexed by ye acquires a broader range as shown in the schemata of Fig. 1.

Therefore, the semantics of ye and its interactional meaning are mutually reinforcing. More accurately, they are appropriate to be regarded as a continuum, the former represented on the left side of the continuum is more objective and concrete, while the latter on the right side is more subjective and abstract (see dotted arrows shown in Fig.1). The use of ye has developed a subjective feature, which also reflects the driving role of subjectification in semantic change (Traugott & Dasher, 2002).

As discussed above, the interactional meaning of ye derived from its generalized core meaning, and the particular position in which it is deployed in sequences cannot be fully explained by ye’s inherent nature. In contrast, the speaker’s interactional purpose and intention seem to be critical. The essence of establishing online alignment is an interaction among participants’ stances or positions, whose nature is the interaction of communicative purposes, such as the implementation of a specific activity. In the interactional context, if the speaker in a responsive position wants to keep and expand the current topic or tries to change the recipient’s point of view by giving a judgment that is different from the previous discourse, the speaker can deploy ye with the function of rapport-building or mitigation to achieve the pragmatic purpose under the cooperative principles and politeness requirements of communication.

In addition, the principle of progressivity is a universal linguistic practice of concern to all language societies (Couper-Kuhlen & Selting, 2018). Yao and Liang (2024) suggest that the likely positions of interactional resources that can extend and push the current action or restart a previous action are the positions of action promotion, which can appear in both initiating and responsive turns. In the responsive position of conversation, sometimes speakers intend to align with their recipients’ understandings, attitudes, or emotions and quickly establish online alignment in conversation to promote the progress of the conversation and the implementation of an action. To achieve this interactional task, ye is economically applicable because ye expressions can contribute to establishing interpersonal connections among co-participants, highlighting the speaker’s enthusiasm for the current topic, narrowing the communicative distance with the recipient, and bringing in positive feedback. By contrast, in those positions that may hinder the progress of conversation, speakers can use ye expressions to mildly express disalignment or inconsistent positioning, contributing to reducing the negative impact of blocking conversation and rebuilding rapport. Interestingly, due to these, someone may deliberately disguise their positions, aligning with the recipient’s stance. However, this does not affect the progress of the conversation. By contrast, it shows that establishing online alignment can be used as a means to achieve a particular communicative purpose and that ye is one of the linguistic resources that can be deployed. Such an interactional use of ye, which is biased towards the speaker’s intersubjectivity, no longer focuses on the similarity between states of affairs but pays more attention to the shapes of interactional relations among participants and the implementation of target action.

Conclusions

Drawing on naturally occurring data, this paper investigates the interactional functions of ye from the perspective of interactional linguistics. It examines how to build online alignment through the use of ye and reveals how ye functions as a pragmatic device to indicate similarity and establish online alignment.

We find that ye expressions can occur in both affiliative and disaffiliative interactional environments. Their uses primarily exhibit two functions: 1) as a rapport-building device to create solidarity among co-participants; and 2) as a mitigation device to alleviate (apparently) conflicting stances. Both patterns function to establish online alignment, with different features shown in practices. To be more specific, through ye expressions, the speakers can not only build rapport by highlighting shared characteristics, listing in-group items, or supporting a previous speaker’s views or actions but can also mitigate conflicting talk by controlling explicit opposing views or alleviating implicit disagreements. We also provide a unified account within the pragmatic continuum of rapport-building and generalized similarity to answer how ye expressions help accomplish the social interactional achievement of online alignment in a discourse context.

Our findings show that the meanings and functions of language resources are adapted to and shaped in the social interaction in which they occur, and this interaction is constituted and modified by the meanings and functions developed and performed in turn. From our analysis, we can gain a better understanding of the meaning and functions of ye in Chinese spoken conversations, and it sheds new light on seemingly objective expressions in Chinese and beyond.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corpus of Mandarin Chinese Spoken Conversation created by the research team and institution of the authors, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under licence for the current study and so are not publicly available. The data are, however, available from the corresponding author Shuangyun Yao on reasonable request and with the permission of the investigator of the research project.

Notes

However, we can see that the interactive usage of ye is more complex than me too and what is proposed.

The participants are from different genders, between 18–30 years old, and have different social backgrounds. Moreover, the data extracted for this study are from various speakers in different conversations. Thus, we believe that our findings can be generalized.

The “alignment” discussed in this paper is different from Stivers’s (2008) explanation, here the alignment refers to an affiliation of the speaker on the second position to the previous speaker’s stance, which essentially follows what is proposed by Du Bois (2007: 144). “Alignment can be defined provisionally as the act of calibrating the relationship between two stances, and by implication between two stancetakers”. Hence, we do not deliberately distinguish the use of the two terms affiliation and alignment, and only choose the more appropriate term in different contexts.

It is worth noting that the current speaker occasionally uses the pattern of [I + ye] to upgrade the other party’s assessment, that is the first speaker gave an evaluative expression, then the second speaker uses [I + ye] to express a similar judgment with different language resources such as the selected words that have been upgraded compared to the previous one. It shows that although the speaker is in a subordinate position, they manifest their epistemic independence to some extent.

Lyons (1981: 237) refers to an objective interpretation as something that is held as a matter of fact or the propositional content of an expression, while a subjective interpretation is defined as expressing the locutionary agent’s “own beliefs and attitudes”.

Note that ai (唉) is originally discussed in Yu (2022). In our opinion, ai (哎) is similar to ai (唉) in sense and they are interchangeable in the corpus so we make no distinction here.

References

Biq Y (1994) “Ye” as manifested on three discourse planes: polysemy or abstraction. In: Dai H, Xue F (eds) Functionalism and Chinese grammar. Beijing Language University Press, Beijing

Couper-Kuhlen E, Selting M (2018) Interactional linguistics: studying language in social interaction. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Davidson J (1984) Subsequent versions of invitations, offers, requests, and proposals dealing with potential or actual rejection. In: Atkinson JM, Heritage J (eds) Structures of social action: studies in conversation analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 102–128

Deng C (2017) The scalar implicature of the adverb “ye”. Stud Chin Lang 6:653–661

Dings A (2014) Interactional competence and the development of alignment activity. Mod Lang J 98:742–756

Du Bois JW (2007) The stance triangle. In: Englebretson R (ed.) Stancetaking in discourse: subjectivity, evaluation, interaction. John Benjamins, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, pp 157–177

Du Bois JW (2014) Towards a dialogic syntax. Cog Linguist 25(3):359–410

Eifring H (1995) Clause combination in Chinese. E.J. BRILL, Leiden

Gao Z (2016) The use of “ba” from an interactional perspective. J Fuzhou Univ Phil Soc Sci 3:80–86

He W, Zhang R (2016) The Chinese function word “ye”: a functional approach. Chin Lang Learn 6:10–18

Heritage J (1984) Garfinkel and ethnomethodology. Policy Press, Cambridge

Hole DP (2004) Focus and background marking in Mandarin Chinese: system and theory behind cai, jiu, dou and ye. Routledge, London/New York

Iwasaki S (1993) Subjectivity in grammar and discourse: theoretical considerations and a case study of Japanese spoken discourse. John Benjamins, Amsterdam

Iwasaki S (2015) Collaboratively organized stancetaking in Japanese: sharing and negotiating stance within the turn constructional unit. J Pragmat 83:104–119

Jefferson G (1990) List construction as a task and resource. In: Psathas G (ed) Interaction competence. University Press of America, Lanham, pp 63-92

Kärkkäinen E (2006) Stance taking in conversation: from subjectivity to intersubjectivity. Text Talk 26:699–731

Keisanen T (2007) Stancetaking as an interactional activity: challenging the prior speaker. In: Englebretson R (ed) Stancetaking in discourse: subjectivity, evaluation, interaction. John Benjamins, Philadelphia, pp 253–282

Kendrick KH, Torreira F (2015) The timing and construction of preference: a quantitative study. Discourse Process 52:255–289

Langacker RW (2002) Deixis and subjectivity. In: Brisard F (ed) Grounding: the epistemic footing of deixis and reference. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin & New York, pp 128

Lerner GH (1996) Finding “face” in the preference structures of talk-in-interaction. Soc Psychol Quart 59:303–321

Li X (2019) An analysis of the discourse marks “en”, “a”, “ai”, “e” in spoken language. J Beijing Univ Chem Tech Soc Sci Ed 2:74–79

Li Z (1997) The origin of “ye” and its diachronic substitution for “yi”. Stud Lang Linguist 2:60–67

Li Z (2012) Functions and evolutions of “yeshi”. Lang Teach Linguist Stud 6:89–94

Liu D, Xu L (1998) Focus and background, topic and lian sentences in Chinese. Stud Chin Lang 4:243–252

Luo G (2013) A study of stance-taking in courtroom interaction. Dissertation, Central China Normal University, Hubei

Lü S (1980) Xiandai hanyu babaici. The Commercial Press, Beijing

Lyons J (1981) Language, meaning and context. Fontana Paperbacks, London

Ma Z (1982) On “ye”. Stud Chin Lang 4:283–287

Morita E (2005) Negotiation of contingent talk: the Japanese interactional particles ne and sa. John Benjamins, Amsterdam/Philadelphia

Morita E (2015) Japanese interactional particles as a resource for stance building. J Pragmat 83:91–103

Quirk R, Greenbaum S, Leech G, Svartvik J (1985) A comprehensive grammar of the English language. Longman, London/NewYork

Schegloff E (1988) On an actual virtual servo-mechanism for guessing bad news: a single case conjecture. Soc Problems 35:442–457

Schegloff E (1996) Turn organizations: one intersection of grammar and interaction. In: Ochs E, Schegloff E, Thompson S (eds) Interaction and grammar. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Schegloff E (1997) Practices and actions: boundary cases of other-initiated repair. Discourse Process 23:499–545

Schegloff E (2007) Sequence organization in interaction: a primer in conversation analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Scheibman J (2002) Point of view and grammar: structural patterns of subjectivity in American English conversation. John Benjamins, Philadelphia

Selting M, Couper-Kuhlen E (2001) Studies in interactional linguistics. John Benjamins, Amsterdam

Shen K (1983) A study on the indicator of “the sameness between differences”—“Ye”. Stud Chin Lang 1 No pagination

Shyu SY (1995) The syntax of focus and topic in Mandarin Chinese. Dissertation, University of Southern California, Los Angeles

Sorjonen ML (2001) Responding in conversation: a study of response particles in Finnish. John Benjamins, Amsterdam/Philadelphia

Spencer-Oatey H (2000) Rapport management: a framework for analysis. In: Spencer-Oatey H (ed) Culturally speaking: managing rapport through talk across cultures. Continuum, New York, pp 11–45

Sperber D, Wilson D (1995) Relevance: communication and cognition. Blackwell, Oxford

Stivers T (2008) Stance, alignment, and affiliations during storytelling: when nodding is a token of affiliation. Res Lang Soc Interac 41:31–57

Tannen D (2007) Talking voices: repetition, dialogue, and imagery in conversational discourse. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Tao H (2019) List gestures in Mandarin conversation and their implications for understanding multimodal interaction. In: Li X, Ono T (eds) Multimodality in Chinese interaction. De Gruyter Mouton, Berlin, pp 65-98

Traugott E, Dasher R (2002) Regularity in semantic change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

van Eemeren F (2010) Strategic maneuvering in argumentative discourse: extending the pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation. John Benjamins, Amsterdam

Wu H, Tao H (2018) Expressing (inter)subjectivity with universal quantification. a pragmatic account plural NP+dou expressions Mandarin Chinese. J Pragmat 128:1–21

Xue L (2023) Negation, accommodation and thought-ascription: on the inferential meaning of connectives in Mandarin Chinese. Dissertation, SOAS University of London, London

Yang Y (2000) On the ambiguity of the ye sentence. Stud Chin Lang 2:114–125

Yang Z (2020) Yě, yě, yě: on the syntax and semantics of Mandarin yě. Dissertation, Leiden University, Leiden

Yao S, Liang C (2024) Three main types of sensitive positions in positionally sensitive grammar. Appl Linguist 1:83–97

Yu G (2022) “Ai” as a topic transition signal in Mandarin conversations. J Foreign Lang 2:61–92

Zhang B (2001) Xiandai hanyu xuci cidian. The Commercial Press, Beijing

Zhang B (2010) Xiandai hanyu miaoxie yufa. The Commercial Press, Beijing

Zhang W, Li X (2023) Echo utterances: a turn design of response in Chinese conversation. Chin Linguist 1:27–39

Acknowledgements

This paper is fully supported by the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF under Grant Number GZC20240582 and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities in China (No. CCNU24ZZ180) and is also partially funded by the Humanities and Social Science Research Project of the Ministry of Education of China (Grant Number 22JJD740028). We are also very grateful to Dr. Kerry Sluchinski for her help on English proofreading.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.X.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing—original draft, and Writing—review & editing. S.Y.: Data curation, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, and Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Approval was obtained from the research committee of Research Center for Language and Language Education of Central China Normal University with an ethical approval letter on 1st May 2018 (Approval No. 20180501RCLLE). The study fulfilled all the ethics requirements regarding human participants. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

The informed written consent form was obtained from all participants before the data collection.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xue, L., Yao, S. From indicating similarity to establishing online alignment: interactional functions of ye “also” in Mandarin Chinese. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 230 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04480-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04480-0